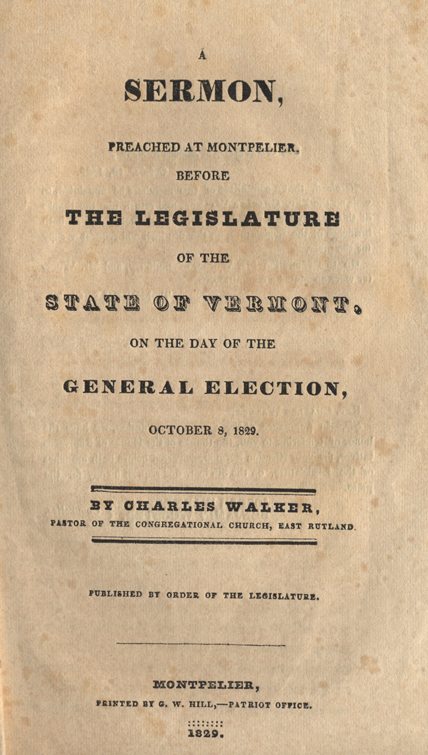

The following election sermon was preached by Charles Walker in Montpelier on October 8, 1829.

SERMON,

PREACHED AT MONTPELIER,

BEFORE

THE LEGISLATURE

OF THE

STATE OF VERMONT,

ON THE DAY OF THE

GENERAL ELECTION,

OCTOBER 8, 1829.

BY CHARLES WALKER,

PASTOR OF THE CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH, EAST RUTLAND.

PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATURE.

October 10, 1829.

Resolved, that a committee of two members be appointed, to wait on the Rev. Charles Walker, and return him the thanks of this House for his Election Sermon, delivered before both branches of the Legislature, on the 8th inst. And request a copy for the press.

On this resolution Mr. Warner of Sudbury, and Mr. Wooster were appointed a committee.

T. MERRILL, Clerk.

Rev. Charles Walker,

Sir,–In pursuance of the foregoing resolution, we have the honor of tendering to you, the thanks of the House of Representatives, for your Election Sermon, delivered before both branches of the Legislature, on the 8th inst. And request a copy for the press.

JOSEPH WARNER,

BENJAMIN WOOSTER,

Committee.

THE piece of history of which this text forms a part is peculiarly interesting and instructive. It is interesting on account of the standing and character of the actors, and on account of the plot and its development, in which goodness and wickedness are opposed to each other, and virtue is rewarded and vice punished. It is instructive because it shows us, by an example taken from real life, how, in certain circumstances, we may regulate our conduct so as to meet the approbation of God, and secure his favor—how He will frown on the disobedient and reward the obedient.

Daniel, on account of the excellence of his character, enjoyed the confidence of the king of Chaldea, and notwithstanding he was a foreigner and his people captives, he was raised to the office of highest dignity and authority in the gift of the monarch. Thus elevated, he became the object of the envy and malice of other rulers in the kingdom, and they commenced a most unjust and cruel persecution against him. His mantle of integrity and robe of innocence did not secure him from the malicious attacks of those who envied his prosperity and shrunk from the blaze of his goodness. They could not endure that a foreigner, a Jew, one who belonged to a captive race, should occupy a seat of honor and power above them. And they were especially offended that one whose religion was so different from theirs, who despised their Gods and worshipped Jehovah; and whose holy life was a constant reproof of their loose principles and vicious practices, should be raised to a station from whence the lustre of his virtues shone in high conspicuity, and revealed the dark depravity of those around him.

They determined on his destruction. To accomplish this, it was necessary either to shake the confidence which the king had reposed in him, or to render him, by some act of his own, obnoxious to the laws of the kingdom. But how could this be done? How could they impeach one whose official doings were ever regulated by the strictest principles of integrity and faithfulness, and whose whole life was adorned with whatsoever is pure and honest and lovely, and of good report? That they felt this difficulty is sufficiently evident from the language of the sacred historian.—“Then the presidents and princes sought to find occasion against Daniel concerning the kingdom; but they could find none occasion nor fault, forasmuch as he was faithful, neither was there any error or fault found in him.” They saw but one way in which they could find a plausible pretext for his impeachment, and this was to make his religion the occasion of his downfall, and to lay a snare which his piety would not permit him to avoid. They said among themselves—“We shall not find any occasion against this Daniel, except we find it against him concerning the law of his God.”

Having observed the regularity with which he engaged in devotional exercises, and knowing that he discharged these duties of piety from principle, they rightly judged that he would not omit them. If, therefore, they could prevail on the king to make a law that no man, during a certain space of time, should pray, they believed that Daniel might be detected in violating this law, and that thus an accusation might be brought against him which would ensure his condemnation. With this malicious object in view, they did prevail on the king to sign a decree, ‘that whosoever should ask a petition of any God or man for thirty days, save of the king himself, should be cast into the den of lions.”

The king was not aware of the purpose of those who obtained his signature to this unrighteous decree. He did not know that a plot was laid, and now sanctioned by his own hand and seal, to destroy his most trusty and approved servant. Flattered, perhaps, with the idea that he should be the only being, to whom the people, throughout his vast dominions, would present petitions or prayers for thirty days—thus elevating himself, as it were, to the place of God—he signed a writing which was intended to be the death-warrant of the man whom he prized above all others. The decree having obtained the royal signature, was irrevocable—according to the laws of the Medes and Persians, it altered not.

And now what will Daniel do? Will he yield to the machinations of his enemies and cease to worship God? Will he give up his devotional exercises, which are enjoined by the divine law, and tremble and turn pale and submit to a human mandate which counteracts the authority of Heaven? Will he let evil men triumph over his defection from his religion? Will he violate his conscience to save his life?

What did he do? Just what his enemies supposed he would. They knew the integrity of his character and the firmness of his principles. They knew his unconquerable attachment to religious duties and his sternness of purpose to obey God rather than man. They knew that, though he might not e afraid to violate an unnecessary and unrighteous human law, there was a Power that he dared not disobey—there were laws which he would not violate. They expected, therefore, that he would disregard the law which they had caused to be made; and it was this expectation which urged them to procure the wicked decree.

He hesitated not. His views of duty were maturely formed and strengthened by holy habit, and they were not now to be given up. What followed, therefore, as related in the sacred narrative, was a matter of course—“Now when Daniel knew that the writing was signed, he went into his house, and his windows being open in his chamber toward Jerusalem, he kneeled upon his knees three times a day, and prayed and gave thanks before his God, as he did aforetime.” It made no alteration either in the manner or frequency of his devotions. While, on the one hand, he did not seek to enrage his enemies nor pour contempt on the royal authority, by a more open or frequent performance of religious services; neither, on the other hand, did he seek to gain the favor of his persecutors or avoid the operation of the iniquitous law, by a more retired or less constant attendance on the duties of divine worship. The former would have been unnecessary bravado; the latter, considering that he was determined to worship God, would have been hypocrisy. From both, the course he pursued clearly exempted him. He simply continued in his former habits, doing exactly and only “as he did aforetime.”

It was of course soon known that the first officer in the kingdom paid no regard to the monarch’s decree. The history says—“Then these men assembled and found Daniel praying and making supplication before his God.” Now their object was accomplished—they had an accusation against him. To the king they went; and according to the letter and penalty of the impious decree, they had the malicious satisfaction of seeing Daniel, at the going down of the sun, cast into the den of lions.

The events which followed—the safety of this servant of God in his perilous situation—his deliverance, and the utter destruction of those who plotted against his life—though exceedingly interesting and instructive, it does not come within the compass of my present design to notice.

The history, as far as we have pursued it, shows us the conduct of a good man and of a distinguished civil ruler, in such circumstances as are fitted to develop moral character, and will afford a foundation for some profitable reflections, not inappropriate to the present occasion.

1. We have, in this historic record, a sublime example of moral courage.

We see a man who, in the discharge of duty, fears nothing but the God who made him. We see a man who, having regulated his principles and shaped his course by the standard of divine truth, refuses to be turned aside from the path of obedience by the command or the force of the mightiest power on earth. He dares to act as his conscience dictates. He dares to be singular, and, in the midst of an idolatrous nation, surrounded by opposers and enemies, to maintain the worship of Jehovah. In full view of the den of lions, and with the certain prospect of a horrible death, he dares to violate the king’s decree, and hold fast his allegiance to God.

He had adopted the principle, the correctness of which is generally admitted in theory but too seldom reduced to practice, that “we ought to obey God rather than man.” On this principle he was determined to act, whatever might be the consequences. He felt that it might not be necessary for him to live; but it was necessary for him to obey God.—This was true courage—courage, not excited by ambition, nor fed by applause; not like the courage of the warrior, roused to deeds of daring by the notes of fame’s loud trumpet; not like the courage of the conqueror in whose eyes the world’s diadem glitters and who is intoxicated with the lust of dominion; but cool, collected, and sustained by its own noble and unearthly principles. It was courage which had its origin and derived its strength, not from earth, but from heaven—not from “looking at things seen and temporal,” but from contemplating “things unseen and eternal.”

Worldly policy, I know, would condemn the conduct of Daniel. It would say that he unnecessarily exposed his life—that he might have neglected his devotions for thirty days, or have performed them only in secret. He thought otherwise—God thought otherwise, for He approved of the conduct of his servant.—The spirit of every divine command is—obey, and leave the event with God. This is the path of duty; it is the only path of safety. But to go undeviatingly and unshrinkingly forward in the path, in the circumstances we have contemplated, required the moral courage of a martyr. It demanded a courage to which many a soldier, who can breast a cannon’s mouth, is a stranger. It called for a courage as much superior to the heedless daring of those heroes whom the world applauds, as the motive which inspired it is superior to worldly ambition.

2. We see, in the example before us, how a human law ought to be treated which requires men to violate the laws of God.

The decree of the Chaldean king was directly opposed to the law of God. Men are commanded by the divine law to worship their Maker daily—to “pray without ceasing.” By the decree in question, they were forbidden to pray at all for thirty days. To obey both was impossible. He of whom the text speaks obeyed the divine law and violated the human edict. And he did right. His conscience approved his course; and his God approved it. The decree, as it counteracted the laws of God, ought not to have been obeyed. No man had a right to obey it. And no human power had a right to require obedience.

Not often, in civilized and Christian lands, have governments enacted laws which clearly and openly opposed the commands of God. But they have sometimes done it. An instance of this kind exists in the history of our own national government—in the law which requires the transportation and opening of the mail on the Sabbath. This law, being a violation of the commandment of God, ought not to be obeyed. And the man who should conscientiously refuse to obey it—though he might be rejected from office or otherwise punished for his disobedience—would stand justified at the tribunal of heaven, in regard to this act, as certainly as Daniel was justified in refusing to obey the wicked decree of the Chaldean king.

I know it is said by many, that the pecuniary interests of our country render it expedient to continue the business of the mails on the Sabbath. But I have yet to learn that such expediency, provided it exists, is a sufficient excuse for setting aside a divine commandment. Are we never to obey God when our obedience will be attended with any pecuniary sacrifice? Are we never to make an offering to God of anything but of that which costs us nothing? But does the alleged expediency exist? How happens it to exist in this country, when in the commercial emporium of the world—the city of London, there are no mails sent forth, nor is the post-office opened on the Sabbath? Does not God know what is expedient for the subjects of his kingdom? And has He not, by a positive commandment, clearly decided that it is expedient for man to rest from worldly business one seventh part of the time? And is not the wisdom of this appointment satisfactorily demonstrated by the experience and history of all Christian nations?

I know, also, when petitions were sent to Congress praying that the law, requiring the business of the mail to be attended to on the Sabbath, might be repealed—it was said, by those who opposed the petitioners, that Congress had no right to legislate concerning the Sabbath. Granted; so the petitioners thought, and they simply asked that Congress would not make laws touching the Sabbath—that they would repeal the law which required its violation. They did not ask for a statute obliging men to keep the Sabbath holy and inflicting a penalty in case of transgression. They did not ask—“as they be slanderously reported and as some affirm that they did”—that Congress would order every mail-contractor and post-master, every stage-driver and stage-passenger to keep the Sabbath, on penalty of its high displeasure. All they sought for was, that the government would no longer command men to attend to secular business on the hours of holy time.

I know, moreover, that it was said in the report of the committee of the Senate, to whom the petitions had been referred, that if Congress complied with the prayer of the petitioners, it would be deciding a disputed theological question—which day is the Sabbath—and that, as there was a difference in the views of the people on this point, government had no right to decide it. This has been regarded, by many, as a master-stroke of unanswerable argument and enlightened liberality, and as such has been praised from one end of the nation to the other. But it is nothing but a piece of sophistry, which has, in a hundred instances, been exposed and refuted. Congress has already decided which day is the Sabbath, by not holding its sessions on the Lord’s day, and by exempting that day from days of business in its courts of judicature. All that the petitioners desired was that government would be consistent with itself, and exempt that sacred day also from days of business in regard to the mails.—If a Jew or a Sabbatarian were appointed a member to Congress, would that body adjourn over Saturday to accommodate him? Must a nation’s Sabbath be disregarded because a mere handful of individuals in that nation happen to think differently from the whole body of the people? Such pretended argumentation is scarcely worthy of an answer.

I am happy in being the citizen of a State, where the divine law of the Sabbath is regarded by the public acts of the civil rulers. 1 And it is with no small degree of pain, that I have felt myself called upon by duty, to censure the conduct of the national government in relation to the Sabbath mails. I love and honor the government of my country; and in all things which do not require me to violate the laws of God, consider myself bound to obey its statutes. But no government can have a right to require its subjects to violate the laws of God. And no law, directly requiring such violation, ought to be obeyed by any citizen.

3. We see, in the example brought to view in the text, that extensive business and the multiplied calls of office do not necessarily preclude a regular attention to the duties of religion.

Few men have ever been in circumstances requiring a more constant and untiring attention to the duties of his station than he, whose history we have contemplated. He was the prime minister of a great nation—had no powerful friends to sustain him—had nothing but his reputation, growing out of his unremitting attention to the duties of his office, to recommend him either to the public favor or to the patronage of the king. And as his official conduct, even by the admission of his enemies, was above suspicion, he must have been devotedly occupied with the business of his station. And yet he found time for a strict attention to the duties of religion. Regularly, three times a day, he had a season of devotion and “prayed and gave thanks before his God.”

How this fact puts to flight many excuses that are offered for neglecting the duties of religion. How it ought to put to shame many a man, who pleads his worldly engagements as an apology for not attending to devotional exercises. This plea is often hears, The man says that the calls of office, or of business, are so constant that he has no time to spend in the daily worship of God. No time! Can this be true? Who gives you all the time you spend on earth? And is it too much that He requires some portion of what he gives to be devoted exclusively to Him? Have you time for meals and sleep, and no time to serve Him whose blessing alone can cause either to be refreshing and invigorating? Have you time to attend to the wants of your body, which is soon to moulder into dust, and no time to attend to the interests of your soul, which is to exist forever? Have you time to spend in conversation with your friends, in relaxation from toil and in amusement, and no time to spend in communion with God, in seeking salvation and laying up a treasure in heaven?—For what purpose was time given? Was it to afford an opportunity to gather a little golden dust which will be blown away by the tempest of the last day, or to collect a few wreaths of worldly honor which will wither and perish; or was it not rather given to afford an opportunity to seek durable riches, honors that never die, crowns of unfading glory in the presence of God and of the Lamb? No time to pray! No time to serve God in the daily exercises of devotion? For what, then, have you time? Were not the days and hours of this world intended principally to afford a season of preparation for eternity? For what is time really valuable, but for this? No man ought to feel that he has time for anything else, till the duties of devotion are performed. This was the grand object for which God gave us time. And, oh! let no man who lives; who measures out his existence by a succession of days and nights which God gives him; who feeds on the divine bounty, sleeps under the divine protection, moves by the divine support—let no man says that he has not time to acknowledge these benefits in daily acts of devotion.

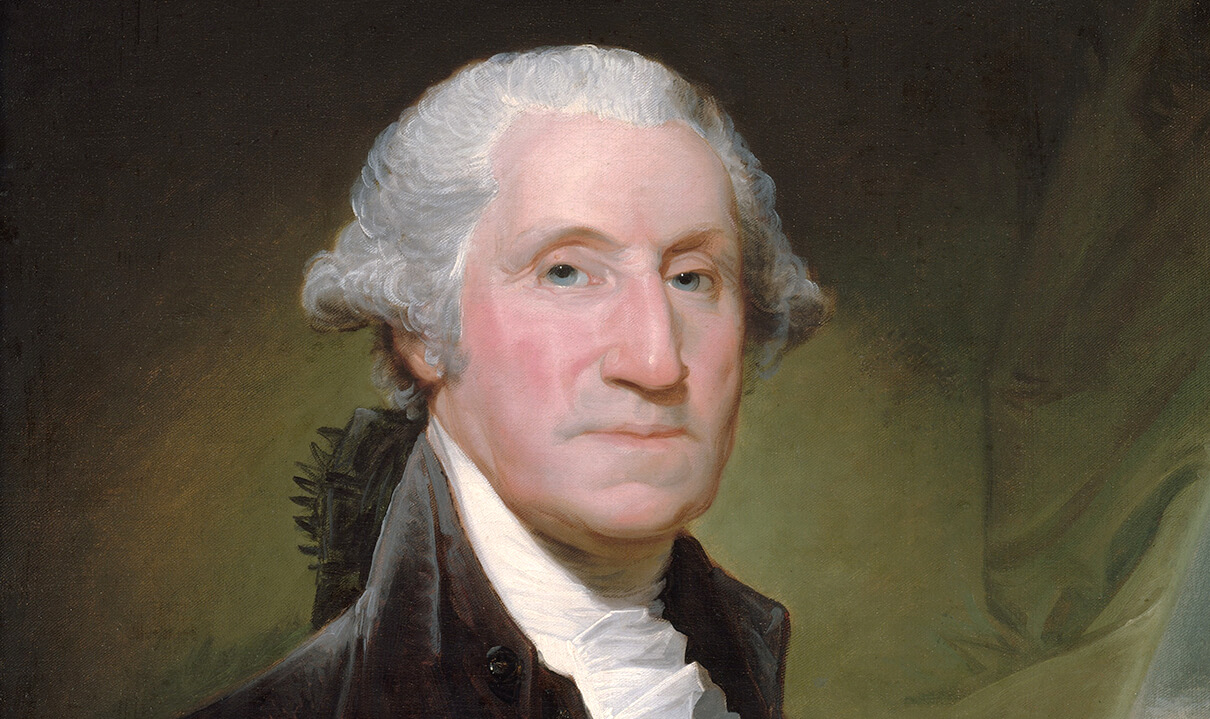

The plea is vain. Others, who have been as busily employed as any of us can pretend to be, have been constant in their attention to religious duties. Daniel, with a principal share of the responsibility in the government of a mighty empire, was an eminent example of constancy in domestic devotion. And our own beloved Washington, than whom no man was ever more devoted to the calls of office, either in the cabinet or in the field, always found time for daily devotional exercises. All men, whose hearts are right with God, have frequent seasons of private and domestic worship. And no man, who has time for anything, can truly say he has no time for these duties. He, who gave us our being and our days, demands of us the homage of habitual thanksgiving and prayer, and no plea for neglect can be admitted before his tribunal.

4. We learn from the example before us, that patriotism alone, in the popular signification of that word, is not sufficient to secure salvation and eternal life.

The man, whose character and history we have contemplated, was a patriot. His untiring application to the duties of his office, and his singular wisdom and integrity as a ruler, are manifest and striking proofs that he sought the best interests of the country which he served. And probably if ever there was a man, who might have claimed the rewards of heaven on account of the extent and usefulness of his efforts for the public welfare, he was the man. Yet he thought it necessary to super add to the virtues of patriotism those of piety. He did not expect to obtain forgiveness and salvation on account of having consecrated his services to the public good. He sought for a seat in heaven by daily prayer and a religious life.

Doubtless he judged right. Such views accord with the standard of divine truth. While every man is bound, by the highest obligation to seek the welfare of his country and the good of his fellow men, he is bound also, by the same obligation, to honor God by discharging the peculiar duties of religion. Nor will the most devoted attention to the former excuse the neglect of the latter. The same divine authority, which commands—“Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s,” commands also—“And render unto God the things that are God’s.” Will an obedience to the one do away the obligation of obeying the other? A man has served his country—Very well; and has he also served his God? A man has been useful as a patriot—Very good, we will give him due credit and honor; but has he been useful too as a Christian? Is not the latter as important as the former? Look into the Bible and say—which will weigh most in the balances of eternity.

But notwithstanding the plainness and positiveness with which the scriptures decide, that a life of piety and prayer is the only evidence of a title to heaven, many cherish the notion, that the man who has served his country well and faithfully will receive, on that account, the reward of eternal life. We can excuse heathen poets and orators, who were destitute of a written revelation, for always sending their departed heroes and statesmen up to a dwelling among the gods. But how can we excuse poets and eulogists and historians, called Christian, when they manifest a similar dark and heathenish disposition to exalt patriots, on account of their patriotism, to a seat in heaven? Yet this, in despite of truth and of the Bible, is often done. Thus when certain distinguished American patriots have died, a hundred writers from the formal eulogist to the newspaper scribler, have given them a place in paradise. Now I pretend not to decide concerning the eternal condition of those departed statesmen. This must be determined by their Almighty Judge. But, in the name of the Bible and of Christianity, I protest against the principle, extensively cherished and often directly avowed, that the patriotism and public services of those men entitled them to the happiness of heaven. If they were Christians and pious men, they are happy: if they were not, there is, of course, no place for them in those mansions which Christ prepared for his followers.

I honor the man who has usefully devoted his life to the service of his country. Let him have deserved praise. Yea, let him “have his reward,” the reward he sought. If he sought the “honor that cometh from man,” let him have it, up to the full measure in which it is due. If he sought the “honor that cometh from God only,” then, and only then, let him be accounted worthy of the reward, which the scriptures promise to the disciple of Jesus Christ.

I have already alluded to Washington. To illustrate the point now under discussion, I mention him again. I love to repeat his revered name. Whose patriotism was ever of a purer and more elevated kind than his? Whose devotedness to a country’s welfare was ever more entire, useful and disinterested than his? If patriotism and public usefulness could entitle any man to the happiness of heaven, was not Washington that man? But he had no such views. He sought, it is true, a dwelling in heaven; but he sought it as a sinner at the feet of his Saviour, and not as a reward for his patriotism. Some striking facts in his history will exemplify this. His servant, who waited on him during the long period in which he led our armies and presided in our councils, told a Christian minister, a few years since, that when he entered his master’s room, as he was directed to do, early in the morning, he frequently found him on his knees, pouring out his desires in fervent prayer before God. This, we have reason to believe was his habitual practice.—An original anecdote of the father of his country, recently published, gives another pleasing testimony to the genuineness of his piety. “While the American army under the command of Washington lay encamped at Morristown, N. J. it occurred that the service of the communion was to be administered in the Presbyterian church in that village. In a morning of the previous week, the General, after his accustomed inspection of the camp, visited the house of the Rev. Dr. Jones, then pastor of that church, and after the usual preliminaries, thus accosted him—‘Doctor, I understand that the Lord’s supper is to be celebrated with you next Sunday, I would learn if it accords with the cannons of your church to admit communicants of another denomination? The Doctor rejoined—‘Most certainly; ours is not the Presbyterian table, General, but the Lord’s table, and we hence give the Lord’s invitation to all his followers of whatever name.’ The General replied, ‘I am glad of it; this is as it ought to be; but as I was not quite sure of the fact, I thought I would ascertain it from yourself, as I propose to join with you on that occasion. Though a member of the church of England, I have no exclusive partialities.’ The Doctor reassured him of a cordial welcome, and the General was found seated with the communicants the next Sabbath.”—Such a man was Washington. He sought for a place in heaven, not by relying on his public services, but by obeying the precepts of his Saviour. He sought the favor of God by habitual prayer and by attending devoutly on the ordinances of the gospel. And eternity will tell to which his country is most indebted, his skill in arms and his wisdom in council, or to that spirit of humble piety and prayer by which he obtained the favor of God in all his enterprises. And now let me ask—whose patriotism will save him, if Washington’s would not?

5. We see, in the example furnished by the text, how rulers may promote the interests of religion without directly legislating on the subject.

Whatever may have been the authority with which the Chaldean ruler was clothed, it is plain that the circumstances in which he was placed prevented his establishing, by law, his own religion. He was among a nation of idolaters, and any official act on his part, designed to destroy idolatry and establish the Jewish religion, would doubtless have been resisted, and the loss of his office and probably of his life would have been the consequence. Still, however, he exerted a powerful influence in favor of true religion—an influence which even his enemies felt, and which, we have reason to believe, was widely useful among the people. This was done by his example. He was a living epistle of the truth, known and read of all men. And it is certain that even to the present day his example, as recorded by the pen of inspiration, sends forth a healthful influence, and is among the means by which the world is benefitted and men are saved.

The civil rulers of this State are not permitted by the constitution to enact laws regulating the creed or the form of worship of the inhabitants. They cannot dictate, by statute, how, or where, men shall worship God, or whether they shall worship him at all. These matters are left to be decided by every man’s conscience and to be answered for by every man’s accountability to God. This is as it should be. We are glad that is so.

But does it follow, because our civil rulers cannot legislate concerning the modes of religion, that they can do nothing in favor of Christianity and of the immortal interests of their constituents? Certainly not. You can, Honored Rulers, do much to promote the eternal welfare of your fellow men and to send the streams of salvation through our beloved State. Do not the offices you hold by the choice of your fellow citizens, show that you are men of high standing and influence? Are not your opinions, feelings and movements felt, in their effects, throughout the State? By imitating then the example of that ruler, whom the text places so prominently before us, you may recommend piety as the richest of all personal possessions—you may lead many, in the ways of truth and righteousness, up to the seats of holiness and the bliss of heaven.

And now, Respected Rulers, when you invited me to meet you on this occasion you did not expect from me a lecture on the science of legislation. On such a subject, were it needful for my usefulness, the station you occupy would seem to be proof that I might sit at your feet and take lessons of instruction from you. But you invited me, as a minister of Jesus Christ, to proclaim His messages and urge His commandments—In the name, then, of my Lord and Master, I come, and ask you all to love and obey Him. This is His will. To show how you may comply with his requisitions, I have placed before you the example of one ruler, whose character and conduct He approved, and who is now with Him in the world of glory. Will you imitate the example of that ruler in worshipping and serving God? Will you engage heartily in the work of obeying the Saviour’s commandments? Will you piously discharge all the duties of religion? Oh! do it, and Vermont shall be blessed. Do it, and though our mountains may not be greener or our vallies more fertile, a moral beauty, pleasing to the eye of God, shall be thrown over our State. Do it, and you will awaken the voice of thanksgiving and the voice of prayer in a thousand dwellings scattered over our territory. Do it, and the news that all the rulers in the State have become obedient to the Son of God, shall cause new “joy in the presence of the angels” on high. O do it, and you will comply with the message of my Lord and Master, Jesus Christ. Nothing less than this will please him or satisfy his demands.—And need I tell you that you are bound to obey Him? Is he not your Lord and King?

He has erected a tribunal before which we must all shortly appear. Soon the trumpet will sound and we shall stand before the Son of man. Then all these human distinctions will be done away and the ruler and the subject stand on the same level. Then these heavens shall pass away and this earth shall be burnt up. And then shall every man be rewarded according to his works. “Be wise, therefore, O ye kings; be instructed ye judges of the earth. Serve the Lord with fear, and rejoice with trembling. Kiss the Son, lest he be angry and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but little. Blessed are all they that put their trust in Him.”

Endnotes

1 A particular instance may be mentioned.—The law, passed some years since, requiring the courts, in our several counties, to commence their sessions on Monday, was found to subject the Judges and other gentlemen attending courts to the necessity of traveling on the Sabbath, in order to pass from county to county, or to assemble from distant parts of the same county, at an early hour on Monday. Of the operations of this law, our honorable Judges and many other gentlemen, who conscientiously regard the sacredness of the Sabbath, complained. The Legislature, on hearing these facts, with a promptness for which they ought to be honored by every good citizen, altered the day of commencing the courts from Monday to Tuesday.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!