John Clarke (1755-1798)

Born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Clarke grew up in a strongly patriotic family during the American War for Independence. In fact, his uncle, Timothy Pickering, was not only a military general under George Washington and later became Postmaster General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State under President Washington. Clark graduated from the Boston Public Latin School in 1761, while only six years old. In 1774 at the age of nineteen, he graduated from Harvard. He returned for his Master’s Degree (1777), and then studied theology, receiving his Doctor of Divinity from the University of Edinburgh. He took a job on the staff of First Church of Boston, alongside the great preacher Dr. Charles Chauncy, who himself had been a significant influence in the years leading up to the American War for Independence. When Chauncy died in 1787, Clarke became pastor, where he continued until he suffered a stroke while preaching in 1798, passing away the next day at the age of forty-three. A two-volume set of his sermons were published after his death. The following sermon was the one he preached at the interment of the Rev. Samuel Cooper of Boston on January 2, 1784. (Note: the Rev. Cooper was a highly influential clergyman, identified by Founding Father John Adams as one of the individuals “most conspicuous, the most ardent, and influential” in the “awakening and revival of American principles and feelings” that led to American independence.)

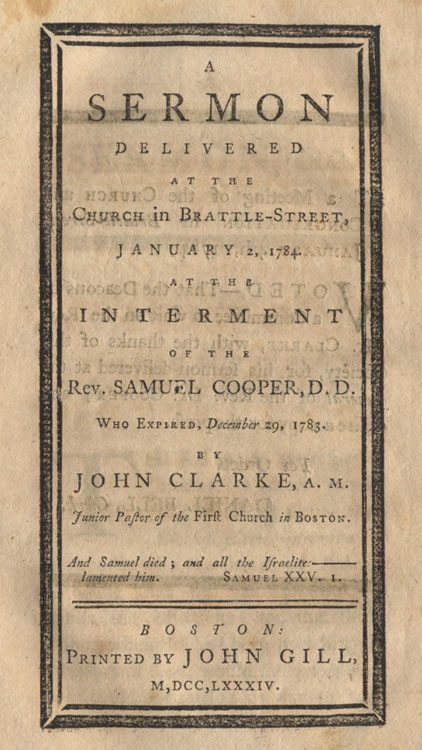

The following sermon was preached at the interment of Rev. Samuel Cooper in Boston on January 2, 1784.

S E R M O N

DELIVERED

AT THE

CHURCH IN BRATTLE-STREET,

JANUARY 2, 1784.

AT THE

INTERMENT

OF THE

REV. SAMUEL COOPER, D.D.

Who Expired, December 29, 1783.

BY

JOHN CLARKE, A. M.

Junior Pastor of the First Church in Boston.

And Samuel died; and all the Israelite—lamented him.

Samuel XXV. I.

SERMON, &c.

ACTS XX. 38.

Sorrowing most of all for the words which he spake, that they should see his face no more.

There is not, my respected hearers, a more tender and affecting scene, than the last solemn interview of the apostle with the church of Ephesus. Knowing that he was appointed to bonds and afflictions; and that those, among whom he had been preaching the kingdom of God, would see him no more,–he could not pursue his way to Jerusalem, till he had first dropped a parting tear; and bid his very dear and valued friends a final adieu. From 1 Miletus therefore, he sent for the Elders of that church: And, with a tenderness peculiarly affecting, he reminds them of the zeal and fidelity with which he had discharged his duty as a minister of Jesus Christ. He had kept back nothing that was profitable to them. He had taught them in public, and in private. The whole counsel of God he had solemnly declared. And, for the space of three years, he had ceased not to warn everyone, night and day, with tears. In proof of this, he appeals to those who were acquainted with him from his first arrival at Asia; and knew after what manner he had been with them at all seasons.

Having done that justice to his own character, which he was conscious it deserved,–he proceeds to his future expectations. And now behold, says he, I go bound in the spirit unto Jerusalem, not knowing the things that shall befall me there: Save that the Holy Ghost witnesseth, in every city, that bonds and afflictions abide me. But none of these things move me, neither count I my life dear unto myself, so that I might finish my course with joy, and the ministry which I have received of the Lord Jesus. This tender and affectionate speech, joined to the gloomy predictions with which it was interspersed, and the liberal sentiments with which it concluded, melted them into tears. They all wept sore. They fell on Paul’s neck, and kissed him. Sorrowing much on his account, because bonds and afflictions awaited him; but more on their own, because they should see his face no more.

The behavior of the Ephesian Elders on this tender occasion, does no less honour to their feelings as men, than their profession as Christians. As fellow-creatures with the excellent apostle, they could not be unmoved at his approaching sufferings. As fellow-christians, it had been ingrateful to refuse a tear. Religion, blessed be God, does not extinguish the social feelings: It refines and improves them. It quickens our sensibility; points out the proper objects of our affection; and when they are torn from us, it teaches us to sorrow, though not as those who are without hope. The grief therefore, discovered by the apostle’s friends, does honor to their hearts. And the lively sorrow, which marks every countenance, and pierces every bosom in this assembly, is no less becoming our religious character!

A faithful minister of Jesus Christ, is deservedly esteemed by the people of his charge. Such was the apostle Paul to the Christians of Ephesus. And such are all those who imbibe his spirit; and are actuated by his noble and disinterested motives. Under God, he had been the instrument of their conversion. He had built tem up in the most holy faith of the gospel. And he had labored, night and day, to form them to that character, and to qualify them for that felicity, which is the glorious object of the Christian dispensation. In prosecution of this work, he had discovered a great and generous mind. Superior to the motives which actuate other persons, he had studied merely their good. And he was undeterred from the pursuit, though it had exposed him to may temptations, and cost him many tears.

This generous and ardent zeal of the apostle they repaid with the tenderest affection. Sensible of his labours of love, and all he had done, and suffered for the church, they beheld him with eyes of gratitude; and openly acknowledged the obligation. Oppressed, as it were, with the memory of his kindness, they wept fore. They fell on his neck: They embraced him: They gave a loose to all those tender feelings, which had been excited by his pathetic discourse.

At this distressing apprehensions from wicked and unreasonable men, they were most painfully affected. Like the master he served, they saw him despised and rejected of men. They beheld him cited before unjust tribunals; and condemned without cause. And, to complete the horrour of the scene, imagination painted him expiring under the cruel hand of persecution; and sealing the truth of Christianity with his blood. And though he appeared unmoved at these approaching sufferings, they beheld them with extreme anguish. The arrow pointed at the breast of the apostle, already pierced them with many sorrows.

But what more deeply wounded their hearts, was the mournful consideration, that they should see his face no more. This was the last interview they should ever have with their most valued friend. No more should they hear his heavenly instructions: No more should they hand upon his lips; admire his gracious words; or be transported with his divine eloquence! His example also, which had been so bright and dazzling, they were to contemplate no more. The apostle was going from them,–going to bonds and afflictions, to sufferings, and to death. He would therefore, take a final leave of them, in this world, hoping for an eternal intercourse in the world to come!

The tears, which were shed on this occasion, were a tribute due to the memory of the apostle. He deserved them all of his Christian friends. No tokens of regard, which they could pay, could possibly exceed the merits of their benefactor. For which reason, we should justly impeach their gratitude had they not melted at his discourse: And their whole Christian character, had they not sorrowed most of all, because they were to see his face no more. These words, when applied to a common friend, call up the most gloomy ideas; but how emphatically moving, when they refer to a generous benefactor, or any one for whom we entertain an ardent affection!

But, from the same principle we applaud the sensibility, and the undissembled sorrow of these Ephesians, we must enter into their feelings; and imitate theirconduct, when he faithful fail from among the children of men. To learning, patriotism and piety, we can not refuse the tribute of a tear. And when all these unite in the person of a Christian minister, his very dust will be precious to us, and we shall weep, with unaffected sorrow, over his cold remains.

It would indeed, be unpardonable arrogance, to pretend that any of the followers of this divine apostle could have his claim to the affections of their flock. However, there have been persons, in the ministerial profession who were burning and shining lights—who, to the learning of the scholar, united the virtues of the patriot; and to the easy familiarity of the companion, the seriousness and devotion of a Christian. In the church of Christ, there have been servants who were an honour to their order. Well instructed in the truths of religion, they have kept back nothing which was profitable to their charge. Generously concerned for the welfare of their flock, they have displayed the grace of the gospel with a most captivating eloquence; and enforced the precepts of it by a splendid example. In one word, there have been persons conspicuous, not only for the love of God, but the love of their country;–distinguished by their patriotic as well as their religious virtues; and no less beneficial to society, than ornamental to the church of Christ! And when such excellent characters are taken from us, shall we not feel, and lament the loss? Shall we not dress their tomb with fresh laurels? With faithful epitaphs shall we not engrave their stone? And, in our bosoms, cherish the everlasting remembrance of their virtues? Could latest time efface their image from our hearts, we should ill deserve the blessings we derive from them.

The death of an amiable, and distinguished servant of Jesus Christ is a loss, which every good mind will sincerely lament. It is a loss to his family and connexions,–a loss to the people of his charge,–a loss to the learned world,–his brethren of the profession,–the Commonwealth,–and, I will add, it is a loss to mankind! The first have peculiar reason to mourn, when the husband, the parent, and the friend is taken from them. And we should justly charge them with insensibility, did they not melt at the reflection,–that they shall see his face no more. How could they restrain the flowing tear, when they behold those eyes closed in night, which once beamed with tenderness and love;–that tongue locked in silence, on which ever dwelt the law of kindness;–and that visage deformed by death, which always wore the smiles of friendship! Surely, no human heart could be unsubdued by such a spectacle.

Next to his more immediate connexions, the people of his charge will mourn his death. They have lost an able minister, and an affectionate friend. How often have they been warmed by his devotion; and instructed by his discourse? How often have they listened to the gracious words, which proceeded from his lips? And, with what pious rapture have they accompanied him to the throne of Almighty God? When sick, how have they been supported by his Christian admonitions? When oppressed with sorrow, how have they been relieved by his tender application of the promises, and consolations of the gospel? When clouds and darkness hae over-shadowed their minds, how have they been enlightened by his religious conversation? And when ready to despair, how have they been reived by his elevated descriptions of the grace of God, and the merits of a Redeemer! Such reflections will crowd upon the minds of a grateful people, when their pastor is taken from them. They will mourn for the loss sustained by his particular friends; but most of all on their own account, because they shall see his face; hear his voice; and listen to his instructions no more!

Again—the death of such a person, will prove an unspeakable loss to the learned world. By his accurate taste, the brilliancy of his imagination, and the clearness of his judgment, he adorned and enriched the republic of letters. Others therefore, will lament his death, besides those who were bound to him by the ties of friendship or religion.

His brethren in the ministry, will never forget the hour, which consigned their dear and valued friend to the grave. The solemn sound of his funeral bell will dwell upon their ear. And his much loved image will present itself in the silent hour of night; or called up by fancy, will meet their waking eyes, in every place sacred to retirement, or religious contemplation. There will they call to mind his many virtues. There will they review the pleasing scenes in which he partook; and the happy intercourse they mutually enjoyed. And often will they repair to the sacred shrine, which contains his venerable dust. The memory of his virtues will create a sigh; while their bosoms will be wrung with the sad reflection,–they shall embrace their friend, and their brother no more!

Finally,–such a distinguished character, when cut off in the midst of his usefulness, will be an irreparable loss to society. The deadly arrow, which destroys him, will deeply wound the bosom of his country, She will feel, in a lively manner, the afflictive dispensation of divine providence: And will mourn over him as an only child. The man, who to the extensive benevolence of a Christian, unites a generous regard to that society of which he is a member, ought to be had in everlasting honour. His prayers, which have been gratefully received by the court of Heaven, ought not to be ingratefully overlooked by his fellow-men. They should remember how they have seen and heard, should call to mind his noble exertions in their behalf; and how uniformly and zealously he has always studied the public good. This part of his character should be the object of their frequent contemplation. They would they be deeply impressed with the loss they had sustained; and they would bless his memory as a patriot, while they revered his name as a minister and a Christian.

Thus have I described the person, who, as a domestic friend, a scholar, a member of society, but more especially, a minister of religion, deserves to be honoured when alive; and when dead, to be universally lamented. And did such a character never exist but in imagination? Did you never see the original of that portrait, I have thus imperfectly drawn? The grief which clouds your brow, the sighs which rend your bosoms;–and the tears which fall from your eyes, proclaim aloud, that such you esteemed your dear and venerable pastor, whose remains are now before you2; but whose face you shall see no more! Behold, the precious dust of your most honoured friend! Behold, all that now remains of the scholar, the patriot, and the divine! Venerable shade! Why dost thou revisit this sacred habitation? Was it to open our wounds anew! Was it to imbitter the cup which divine providence has poured out to us? Or was it to impress our minds with this mortifying truth—that EVERY MAN, AT HIS BEST ESTATE, IS ALTOGETHER VANITY!

We mourn with you, Christian friends, on this very distressing occasion. You have lost a most amiable and engaging minister; we a most friendly and entertaining companion. Some, in this assembly, mourn a husband, a parent, or a brother dead: And others are now paying the last tribute of respect to a patriot no more! We, who have more lately entered into the ministerial profession, bewail a friend, from whom we expected the greatest comfort; and whose counsel, assistance, and the pleasures of whose conversation, we promised ourselves for years to come. But vain are all expectations from so uncertain a thing as human life. Our friend, and your pastor is called to the mansions of the dead; and we shall see his face no more!

Within these walls, sacred to piety, and the public worship of God, you shall no more hear his voice. No more hall you catch the flame of his rational and animated devotion. No more shall your prayers ascend, clothed with his pious eloquence, an acceptable tribute to the father of mercies. No more shall the great truths of religion be set forth with his beauties of style; or recommended with his engaging delivery. That voice, those powers, and that manner, which once charmed, will charm no more!—Wherefore, give a loose to those tender feelings which his death has excited. There is a luxury in religious grief, unknown to vulgar minds. And the greatest understandings will not think it a weakness, in faltering accents, or a broken voice, to express their sorrow.

Justly should I incur the censure of his friends;–and greatly should I injure the memory of Dr. Cooper, should I not say, he was a peculiar ornament to this religious society. His talents as a minister were conspicuous to all; and they have met with universal applause. You know, with what plainness, and, at the same time, with what elegance, he displayed the grace of the gospel. You know, with what brilliancy of style he adorned the moral virtues; and how powerfully he recommended them to universal practice. When the joys of a better world employed his discourse, can you ever forget the elevated strains in which he described them? And his prayers, surely they must be remembered, when his qualifications for the other duties of his office, and his many shining accomplishments are forgotten! If those, who constantly attended upon his ministry are not warmed with the love of virtue;–if they are not charmed with the beauty of holiness;–if they are not transported with the grace of the gospel, must they not blame their own insensibility? Remember therefore, how you have seen, and heard, and hold fast, and repent.

But the place in which I now stand, was not the only theatre, on which he appeared with such applause: In private, also, he displayed his talents for the office he sustained. With peculiar facility, could he enter into the feelings of others, and adjust his conversation to the particular state of their minds. He could raise the bowed down, and encourage the feeble hearted. In the house of mourning, he could light up joy. He could inspire those, who were approaching the shades of death, with Christian fortitude. And by expatiating on the mercy of God, and the merits of a Saviour, he could revive those who were ready to despair! Thus various and accomplished his character, how justly are you affected on this occasion!

However, the people of his charge are not the only persons who mourn this event. The death of their honourable pastor is a general calamity. It is severely felt by all our societies: And by that, in a particular manner 3, which has been so long united with this church in a stated lecture. It is felt by this town, which gloried in him no less as a citizen, than a minister of the gospel. It is felt by the University, to whose honour and interests he was passionately devoted. The governours of that learned society will testify, how ardently he labored to raise it to superior eminence; and how he encouraged those sciences, the sweets of which he had so early, and so liberally tasted. His death will be lamented by this Commonwealth; and most sincerely, by some of the first characters in it. For with them he was intimately connected, and they distinguished him by every public token of respect.

In one word, his death will be a common loss to these American States; for, as a patriot, he was no less celebrated, than as a divine. Well acquainted with the interests of his country, he constantly and ardently pursued them. But while, as a states-man, he discerned what would tend to our glory and happiness, as a minister of religion, he prayed it might not be hid from our eyes. And you can tell with what fervor he offered up his supplications.

I MIGHT now descent to the more ornamental parts of his character. I might display him as the familiar friend, and the entertaining companion. I might remind you of his correct and elegant taste; and that most engaging politeness, which rendered him so agreeable in every private circle. But why should I aggravate a wound, which already bleeds too much! Why should I call up the pleasing image of a person, whom you shall see no more? Let me rather suggest those consolations, which will enable you to bear your loss with Christian fortitude, and to sorrow not as those who are without hope.

And behold, your 4 redeemer liveth; and he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth. Yet a little while, and5 Lord shall descend from Heaven with a shout with the voice of the archangel and the trump of God! And then shall the dead in Christ awake to immortal felicity! 6 That body, which is now sown in corruption, shall be raised in incorruption: That which is sown in dishonor, shall be raised in glory: That which is sown in weakness, shall be raised in power: And this natural shall be transformed into a spiritual body! Behold, I shew you a mystery! We shall not always remain under the power of the grave; but, in a moment, shall we awake, at the last trump; and our bodies shall be changed. And7 Jesus Christ shall fashion them like unto his glorious body, according to the working, whereby he is able even to subdue all things unto himself. Happy day! When they who sleep in Jesus, shall hear his voice and come forth! When they shall be delivered from all the infelicities of this mortal state! When8 they that are wise, shall shine as the brightness of the firmament;–and he that hath turned many to righteousness, as the stars for ever and ever!

9In the multitude of your thoughts within you, may these prospects delight your souls. May they support you at the silent tomb, to which you will soon repair; and leave the precious dust of our departed friend. May you realize them at the holy communion, on the approaching Sabbath. And may they be your joy and consolation, whenever you call to mind his amiable character; and remember that you shall see him no more.

And now, brethren, we proceed to the last tokens of respect to these remains. Could that voice, which has so often delighted this assembly, be once more unlocked, I can easily conceive, how you would be accosted by our deceased brother. Forgive me, if I presume to be his voice on this occasion Beloved Charge—Let not your hearts be troubled, ye believe in God, believe also in his Son. 9 If ye loved me, ye would rejoice, because I go to your father and my father; to your God and my God. To that God I now 11commend you, and to the word of his grace which is able to build you up; and to give you an inheritance among all them that are sanctified.12 And now, brethren, a long, a last farewell: Be perfect, be of good comfort, be of one mind, live in peace; and the God of love and peace shall be with you!

A M E N.

The following character of Doctor COOPER, drawn by another hand, is taken from the Continental Journal, of January 22, 1784.

Dr. Cooper was the second son of that distinguished divine, the late Rev. William Cooper, one of the pastors of the church in Brattle-Street: He was born the 28th of March, 1725. While he was passing through the common course of education at a grammar school in this town, and afterwards at the university in Cambridge, he exhibited such marks of a masterly genius as gave his friends the pleasure of anticipating a life eminently useful to his country.

His pious father having designed him for the gospel ministry, was happy to find his son’s inclination meeting his own. Divinity was therefore the Doctor’s favorite study; and having early felt the impressions of serious religion, the honour of being a minister of the gospel weighed down every consideration of temporal advantages.

He early made his appearance as a preacher, and so acceptable were his first performances, and such the expectations they had raised, that he had scarce attained to the age of twenty years before he received a call from the church and congregation in Brattle-Street, to succeed his father who died December 13th, 1743, as colleague with the celebrated Doctor Colman. In this office he was ordained May 25th, 1746, just thirty years after the ordination of his father.

The Doctor did not disappoint the expectations he had raised; his reputation increased, and he was soon one of the most universally acceptable preachers in the country. Through a course of near thirty-nine years public ministry, he conducted himself with such wisdom and integrity, prudence and ability, as procured him the like love and esteem from his venerable colleague, and the people of his charge which his father had enjoyed, and the notice and respect of all the clergy in the Commonwealth. Indeed his whole life was worthy the imitation of all who wish to live admired, or die lamented.

He early discovered a happy talent for composition; his sermons bore the mark of a genius and taste: they were clear and elegant—sensible and truly evangelical, and delivered with an energy and pathos which warmed the heart,–in a stile which charmed the ear,–and with an eloquence which always gained the attention of his auditory.

In prayer he was greatly distinguished;–his thoughts and language were devotional, pertinent and scriptural; well adapted to the particular occasion, and delivered with such humility and reverence, and at the same time grateful variety, as could hardly fail of kindling a flame of devotion in the most dull and lifeless of his fellow-worshippers. When celebrating the peculiar mysteries of our holy religion—how was he carried even beyond himself, with such a flow and fullness of expression, as often bore away the intelligent and spiritual worshippers as on angels wings towards heaven!—

About twelve months after his call and before his ordination, a malignant and mortal fever then prevailing, he was introduced by his reverend colleague to the chambers of the sick, and the beds of the dying. He has often observed, it was a happy introduction to the work of the ministry—It was one means of eminently qualifying him for that part of pastoral duty; and it is universally allowed that few, if any, were more judicious and successful in their applications and addresses to persons in those circumstances.

His religious sentiments were rational and catholic, being drawn from the gospel of Christ; in them he was ever steady, and though a friend to the rights of conscience and a free enquiry, he yet wished to avoid, in his common discourses, those nice and needless distinctions, which had too often proved detrimental to Christian love and union.

It was happy for his country, that his early intension of devoting himself to the work of the gospel ministry, or the cares of that important office to which he was ever attentive, did not prevent his completing his character by an intimate acquaintance with other branches of science besides divinity, particularly with the classicks. Upon their sparkling field he pleasingly roved from flower to flower, and finally became one of the most finished scholars of the present day.

He was a friend to learning, and to the university in which he was educated, and was a faithful member of the board of overseers. After the loss of Harvard hall, with the library and apparatus, by fire, in 1762, he exerted his extensive influence in procuring subscriptions to repair that loss. There having been a vacancy in the corporation in 1767, the Doctor was elected one of that board, and continued a very attentive, firm, and judicious member until his death.

His fame for literary accomplishments, and his character as a divine, became too great to be limited to his native country; it introduced him to the university of Edinburgh, from whence he was complimented with a diploma of doctor in divinity.

Dr. Cooper was an active member of the society for propagating the gospel among the aboriginals of America, the work was pleasing to his benevolent mind, and he was ever watchful that the pious intensions of the donors in those charities should not be disappointed.

When his country had asserted her right to independence, he was anxious to lay a foundation for the encouragement of useful arts, and the growth of the sciences in this land of civil liberty. In his opinion knowledge, as a handmaid to virtue, was necessary to support free governments and promote public happiness. He was therefore one of the foremost in forwarding the plan on foot, in 1780, for establishing an American academy of arts and sciences; and this society, from a sense of his literary merits, elected him their first vice-president.

To his acquaintance with divinity, and the other branches of science, were added a just knowledge of the nature and design of government, and the rights of mankind.—The gospel taught him to wish and promote their happiness, and the shining examples of the first ministers of this Commonwealth in the cause of their country, were ever before his eyes.

He well knew that tyranny opposes itself to religious as well as civil liberty; and being among the first who perceived the injustice and ruinous tendency of those measures of the British court, which at length obliged the Americans to defend their rights with the sword, this Reverend Patriot was among the first who took an early and decided part in the politics of his country.

He did what he could, not only by his prevailing address, his counsels and advice, but by his pen, in conjunction with other distinguished patriots, to alarm the sleepy, animate the timed, support the sufferer, encourage the warrior, and unite the people.

The abilities and steadiness thus manifested in this glorious cause, endeared him to his country, and he was esteemed, consulted and confided in by some of the principal leaders in the opposition—The success of it lay near his heart, and he regarded as friends all who aided it, whether here or in Europe.

He did much to obtain foreign alliances, and his letters were read with great satisfaction by the ministry of Versailles, whilst men of the most distinguished characters in Europe became his correspondents.

When France made a proffer of her friendship in the most disinterested manner, and became the supporter of our freedom and independence, it was necessary to subdue the prejudices against that nation which Britain had early sown in New-England, as also to conciliate the habits and manners of the two nations—Dr. Cooper appeared as one peculiarly formed by heaven for this happy purpose.

He possessed an elevation of thought, a delicacy of sentiment, and quickness of apprehension, which, united with an easiness of manners, and the most engaging address, never failed of gaining the attention and giving pleasure to the most respectable circles. Noblemen of the first distinction in Europe and fame for their literary accomplishments, having been by the course of the late war brought to America, were fond of being introduced to him;–when they had once seen him, they coveted an intimate acquaintance.

The great friendship subsisting between him, Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams, was one means of his being known in France; and he gentlemen coming from that kingdom were generally recommended to him by those ambassadors.

When the fleets of his Most Christian Majesty have adorned our harbor, he was always the confidential friend of the gentlemen who commanded; and the many officers and subjects of that august and beloved Monarch who visited him, were ever received with an ease and cordiality that was pleasing, and highly endeared him to them.

When the civil constitution of this Commonwealth, in which he had some share, was formed and approved of by the people, he was, according to the custom of the country, called upon to introduce it with a sermon: this discourse, with others of his writings, have been printed in several languages, and are some specimens of his singular abilities.

The nature of his illness, which from the first he apprehended would be his last, was such as rendered him some part of the time incapable of conversation.—He had, however, intervals of recollection: at these times he informed his friends that he was perfectly reconciled to whatever Heaven should appoint—willing rather to be absent from the body and present with the Lord; that his hopes and consolations sprang from a belief of those evangelical truths which he had preached to others; that he wished not to be detained any longer from that higher state of perfection and happiness which the gospel had opened to his view.

He declared his great satisfaction in seeing his country in peace, and possessed of freedom and independence; and his hopes, that by their virtue and public spirit, they would shew the world that they were not unworthy those inestimable blessings.

With the tenderest expressions of love and kindness to his near connections and friends and the dear people of his charge, who have always shewn him every mark of their love and esteem, he closed this mortal life, and has, we trust, entered into the joys of his Lord.

Thus lived and thus died, the great and amiable Doctor Cooper, and his death is a loss which learning and religion, patriotism and friendship, will long feel and lament.

Endnotes

1. Ver. 17.

2. The body was carried into the church on this occasion.

3. The first Church.

4. Job xix. 25.

5. Thes. Iv. 16.

6. I Cor. xv. 42, &c.

7. Phil. III. 21.

8. Dan. XII. 3.

9. Psal. XCIV 19.

10. Ver. 28.

11. Acts XX. 32.

12. 2 Cor. XIII 2.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!