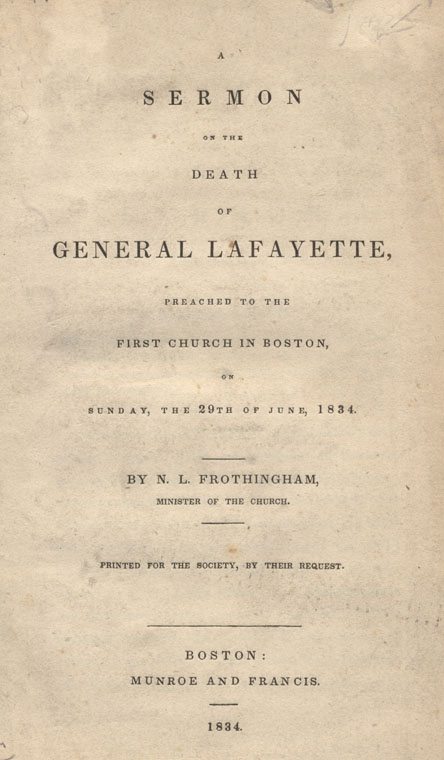

Nathaniel Langdon Frothingham (1793-1870) graduated from Harvard in 1811. He was the pastor of the 1st Congregational Church in Boston (1815-1850). Frothingham preached this sermon on the death of the Marquis de Lafayette on June 29, 1834.

SERMON

ON THE

DEATH

OF

GENERAL LAFAYETTE,

PREACHED TO THE

FIRST CHURCH OF BOSTON,

ON

SUNDAY, THE 29TH OF JUNE, 1834.

BY N. L. FROTHINGHAM,

MINISTER OF THE CHURCH.

“Elias it was, who was carried up in a whirlwind; and Eliseus was filled with his spirit. Whilst he lived, he was not moved with the presence of any prince, neither could any bring him into subjection.”

If it were only a political leader, a great military commander, a national friend and benefactor, an illustrious man, – according to any of the vulgar patterns of fame, – that has at length gone the way, where the meanest must follow, where the most different conditions are made equal, and there is no more place for rank and pride; his memory would hardly be a fitting subject to mix with the services of the Lord’s house. If it were some mere man of the people, some man of the times, some creature of splendid accidents, that claimed to be made mention of, here is not the place where such a claim would be regarded. If the feeling, that now pervades this community to its furthest borders, were a party feeling; if the tribute, that is now paying to his name from the freemen of all nations, were a tribute to station and chance, to talents or historical renown, and not to character, to a pure and noble desert; if the voice of praises and regrets, that is lifted up on every side of us, were only a popular acclamation for some transient benefit, or an unmeaning echo of what it has become customary for half a century to repeat; the pulpit at least might well be silent. But the circumstances are altogether otherwise; and the preacher may be more than excused if he is not silent, however inadequate to the occasion his words may be, and however lost and forgotten among worthier expressions of eulogy.

The man of whom I am to speak, and whom no one needs name, was perhaps even more remarkable by his conduct and personal qualities, than by all the various situations of his eventful life. At the top of fortune and power and favour, never elated; in the depths of disappointment and hopeless afflictions, never stooping or depressed; amidst the most magnificent temptations, never beguiled; amidst the wildest disorders, never discomposed; amidst the most difficult and delicate conjunctures, never at a loss; amidst the sharpest perils, never afraid; – he was true to himself and his principles, through the most agitating succession of changes that ever swept over the world. And therefore it is, and not because he stood on an eminence, and not for any advantages which he might have but chanced to bestow, that we may make mention of him in our holy places and the offices of devotion.

One may look in vain among the names of ancient or modern celebrity, to find any other who closely reminds us of the Father of our Country, by a similar combination of noble endowments. But He not only recalls him, but presents the most striking resemblance to him. He was formed of like materials. He was trained by a like discipline. A son of his house, and a pupil of his school, he appears with such a similarity of moral features as is seldom transmitted by natural descent, or formed by the influence of any model or education. No one shares with him this distinction. “Elias it was, who was carried up in a whirlwind; and Eliseus was filled with his spirit. Whilst he lived, he was not moved by the presence of any prince, neither could any bring him into subjection.”

There is something very instructive, as well as affecting in the sensation which the account of his death has recently produced among this people. He was a foreigner; of a different speech from ourselves, and dwelling in a distant home. He was an old man. He had passed far beyond the limit that is usually assigned to mortal life, and might seem to have lived long enough for any active service, having little else left to do but to die. He was not contributing, nor ever did contribute, by any peculiar intellectual ability, to the delight or instruction of mankind. He was a plain and a private man; divested by his own act of every title but that of a moral nobility, and deprived by an ungrateful government of all authority but that of a moral influence and command. He was not even adorned with the glory of success, but found the close of his days overshaded with disappointment and defeat. There have been some to tell us that there was no strain of greatness about him, and that the only appellation fairly due him is that of the good. We shall admit the assertion, – we shall accept the discovery, – when our views of what constitutes a great character shall agree more fully with theirs, who deny him the praise of possessing one. That part of the commendation, however, which they are willing to bestow, is as much as we need care at this moment to take up. We may point to it, and say; here is the true source of the sympathy and admiration and regret that we are now witnessing; feelings that are not confined to us but communicate their emotion round the globe. It is for the sake of his virtues, that his departure is bewailed as a misfortune; and his long-delayed assumption to a better glory than that of earth’s empire and man’s applause has come upon us as a prematureness and a surprise; and his “bones flourish out of their place”; and his remembrance is precious. When you have seen young faces saddened and old eyes wet at the tidings of his decrease, you knew that it was from the thought of his worth. When you hear the expressions of the general sorrow, you cannot fail to recognize in them testimonies of homage to a generous, constant, elevated soul.

A leading name has been struck from the roll of the living. A golden band, that connected us with the history of two generations and with some of the most interesting passages in the history of man, is broken. A venerable form, marred – as you have seen it – among the exposures of his daring devotion to what was right; familiar with all extremes of fortune, with the rough exercise of camps, and the dazzling pomp of courts, and the dreary solitude of dungeons; – equally collected in halls of legislation and fields of battle, and in popular crowds whether they were moved at his eloquence or muttered their discontent, whether they offered him garlands or demanded his head; – equally at home in the quiet joys of the vintage and the harvest and the summer flowers, and in the stormy labours of three revolutions; – wherever it has been, it has now gone to mingle its dust with a long line of distinguished ancestry. A brave and a loving heart has added one more to the company of the glorified. They who shall visit like pilgrims his residences in the old world will look round in vain for his cordial hand and benignant countenance; and he will not cross the sea for a fifth time towards the land that he helped to redeem. He has disappeared. He has lain down in the great rest. The ground is not consecrated by the ashes of a more single-minded and estimable and admirable man. Do not call death an equalizer, when it thus puts obediently the seal of a stamped decree and an eternal distinction upon the deeds and the name of one, over whom it has no power.

Let it be permitted to say a few words, which are all that the occasion permits, upon the peculiar character of this citizen of two worlds, this persevering friend of universal humanity, this pure impersonation – if such a thing was ever presented – of the two grand principles of order and liberty. It is of his character only that I would say these few words; for the facts in his recorded life have long been a book for our children, and are read of all. They shall be spoken with hat deep conviction and that affectionate reverence, which are neither new nor feigned.

The personal qualities, you will readily believe, must have been in several respects remarkable of one, who, without ostentation, – nay, declining and despising all the parade that vain men covet, – has made himself memorable, the world over, as a champion and pleader, a confessor and a faithful example, wherever the injurious were to be restrained, or the unfortunate helped, or the oppressed delivered. “Elias it was, who was carried up in a whirlwind; and Eliseus was filled with his spirit.” He was filled with it. What that spirit was, in its general features, we should be unpardonable if we were uninformed or forgetful. But let us attempt to define it with some particularity. Now that he is joined to his old commander, we remember that “whilst he lived he was not moved with the presence of any prince, neither could any bring him into subjection.” The text fitly describes him, in some of the leading traits of his steady and lofty mind. He never swerved from his principles; never temporized with the weak, nor gave way before the strong. None ever held his integrity faster than he, through all good and evil repute. He was inflexibly consistent; and this, which is a rare merit under any circumstances, becomes the more remarkable, when it is displayed as his was amidst troubled and disjointed times, when the world was maddening in a tumult of changes, and he wise were distracted, and the wicked ruled, and the firm were divided with perplexity and fear. He stood to his purposes with an unshaken constancy, and permitted nothing on earth to feel itself his master. His courage towered up above the most frightful emergencies, and his self-possession abode the proof, when others were losing their reason. He refused ever to despair of a cause that he had once believed to be good. He refused to withdraw his hand from its most unrequited and ill-requited toils, from its sternest perils and dearest sacrifices. It was nothing to him where he stood, so that he stood for the right. He made no compromises with rabble or emperor. The violence of the low could neither intimidate his resolution nor wear out his patience, while the will of the earth’s mightiest and proudest ones could not imagine for a moment that it had the right or the power to dictate to his.

But in all this rigid perseverance and high honour was there no harshness, no arrogancy, no repulsive or unlovely admixture? So far from it, as you all well know, that nothing can be conceived more mild and courteous, more unaffected and unpretending, than his whole carriage of himself towards his fellow men. He won hearts, wherever there could be truly said to be hearts, by the gentle dignity and the meek courageousness of his bearing. He was full of quick sympathies. He was forbearing and kind. He embraced all within the regards of an unwearied benevolence. The elements of his nature were all strong, but all kept in their proper places. He united with singular happiness those, which are usually found severed and opposed. There were tenderness and force dwelling together in him, like the leopard and he kid of the ancient prediction. His was a spirit of prudence and a spirit of fire, tempered into one. He was daring but wise, eager in action but patient in endurances, sanguine and impetuous, but self-moderated. His presence of mind was not allowed to desert him under any necessities that called for it. He never forgot what was due to others, nor made any haughty estimates of what was due to himself. There was nothing in him of the self-seeking of an ordinary ambition, nor was the plain modesty of his manners impaired in any degree by the scenes of breathless interest in which he had sustained a chief part, or by the vast concerns that were accustomed to rest upon his counsel and conduct, or by the general encomiums of mankind. He was eminently disinterested. It was not his own aggrandizement that he ever carried in view, but only his unsullied name, and his unshaken principles, and the welfare of the world. Rich remunerations have been offered him, only to be declined with the cold assertion, that he attached no more importance to the refusal than to the acceptance. He divested himself of all honours, which would not contribute to any valuable end by being worn. An enemy to dangerous power, he put it calmly aside from him as often as it was presented to his hands; whether it was offered in the shape of the marshal’s staff, or the sword of the constable of France, or the more splendid ensigns of a dictator’s command. An enemy to outside pomp, he withdrew from all appearance of it, when no good to others was to be gained from the display. He, who made his first visit to our shoes in a vessel of his own preparing, would not wait for the national ship of war that was commissioned to bring him over on his last one; but preferred coming as a private man and a stranger, if it might be allowed him to do so. He found the arms of twenty-four states ready to catch him up; and the old soldier was to be greeted as a father rather than as a guest; and every sound he heard was to be like a benediction, and every step he took better than victory. No one can have read of him, without being sure that it was not so satisfying a joy to him, when he rose up in the federation of the Field of Mars as the interpreter and representative of a nation, or when he was placed at the head of more than a million and a half of his armed countrymen, as when he perceived that he lived in the affections of millions of the grateful and the free. Much as has been related of him, much as is already known of him, his history remains to be written. But his character it is impossible to mistake; and whatever new shall be hereafter recorded will be in honourable consistency with it and only illustrate it the more.

“Whilst he lived,” says the text, “he was not moved with the presence of any prince, neither could any bring him into subjection.” What a train of the crowned and the discrowned, now for the most part but shades of kings, passes before us at the repetition of these words. They brought their importunities to him, or they laid their orders upon him; but they found him just as he has now been described. What was royalty, in its threats or persuasions, to the royal law in his own breast? A German sovereign one, and a deposed monarch driven from two thrones long afterwards, were taught by him that the vengeance of the one and the intercessions of the other were alike vain, when they would urge him to crouch to a galling necessity, or dissemble his cherished sentiments, or compromise his pure fame. In his own city five princes reigned, from the time when he first entered into its busy affairs, to the day when he closed his eyes upon it forever. We have only to look at his intercourse with hem, to perceive that there was something in him above their regal state.

The first, and most unhappy, both leaned upon him and feared him; and might have been rescued by him a second time, if it had not been thought too much to be indebted to him a second time for deliverance. The next was that wonderful chief, who almost dazzled the world blind with the blaze of his conquests. But there was one, who kept fixed upon him a searching and sorrowful look, as unshrinking as his own, and, as the event proved, more than equal to his own. He had retired quietly to his country home. He refused even an interview with the “emperor and king,” in his palace hall, since he had assumed to be a despot over his brethren. Palaces! He had seen all their hollowness and false luster. He was entitled to them as his resort from his early youth, and he had witnessed more wretchedness than he had ever beheld elsewhere in their envied inmates. The places that had been the objects of his boyish delight, he knew as dwellings of bitter cares and sorrows, before they were burst open by violence and spotted with blood. And is it strange, if he should have lost something of his reverence for courts? But let me add, that, when the conqueror was subdued, – when the city, that had well nigh been made the capital of the earth, was traversed and encamped in by insolent foes, – he endeavoured earnestly to befriend the fallen majesty, whose domination he had resisted. He had no hostility against the imperial fugitive, now that his ambition had overleaped itself and was no longer a terror. His indignation was turned to the opposite side; and when the English ambassador offered peace on the condition of delivering him up to the invaders, he replied, “I am surprised, my lord, that in making so odious a proposition to the French nation, you should have addressed yourself to one of the prisoners of Olmutz.”

The third figure that rises, is that of an unwieldy pretension to royalty, set up by foreign hands, and speaking what he was told to speak, and almost as helpless while he reigned, as the phantom that he seems to us now. His infatuated successor is an exile, one hardly remembers where, from an authority that he neither knew how to limit nor maintain. What could be, of whom we are now thinking, have to do with pageants like these, – except to warn them that they must pass away?

Another interval of murderous contention, and another king is in the seat that had been so rapidly and ominously left empty. Him he met as an adviser, and not as an inferior, as a patron rather than as a dependent. But his deed and intention returned to him void, and his expectations were once more baffled.

Let it be so. He has at length gone where there is no more disappointment, and where his faithful works will faithfully follow him. We will not wish that he had remained for further trials. We cannot bear to think of his furnishing opportunities for cavil, to those who do not revere and cannot understand him, by any faltering that might possibly have crept along with his old age, – by any clouding of his clear judgment, any declension of his well-used strength. Let him pass upward in peace to the King of kings and the Lord of lords, by the signs of whose “presence” he was always “moved,” and to whose holy Providence he brought himself cheerfully “into subjection.”

No; we will not desire him back. He has done enough; endured enough; enjoyed enough. It is time that he was translated. But we will write up his name as on a banner. We will plead that his memory may be sacredly appreciated and never forgotten. His example should shine out as a lesson, in these days of sycophancy and rank abuses, of party spoils and political profligacy and greedy gain; when Elias has been carried up in his chariot of glories, and they who never felt his spirit, and even scoffed at his immortal services, presume to connect themselves with his fame.

The bones of the disciple-prophet were said to awaken the dead. “He did wonders in his life, and at his death were his works marvelous.” 1 The miracle is done over again yet, and more nobly done. The name and character and deeds of the just are often a living and divine touch, after “their bodies are buried in peace.” May it be so with him! May the memory of that Eliseus, whom I have endeavoured to bring to your hearts to-day, stir up a community that is already turning into corruption to a fresh and purer life!

Endnotes

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!