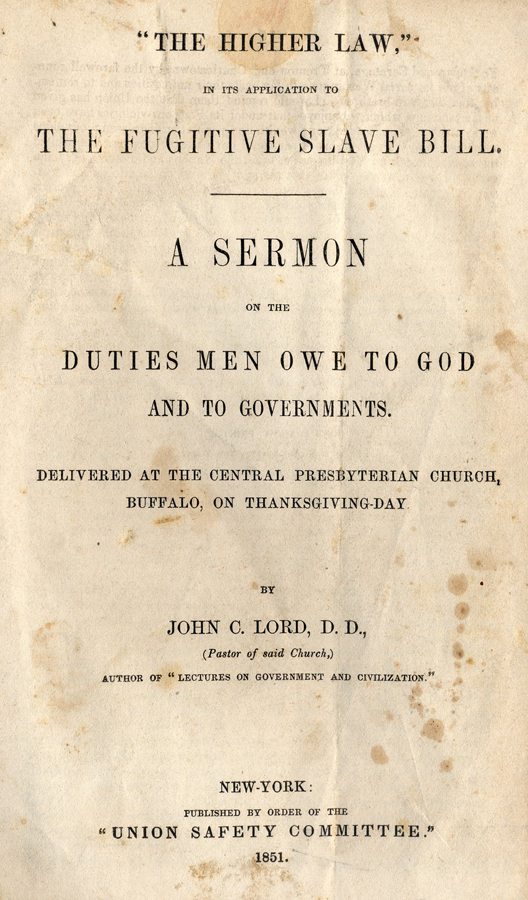

John C. Lord preached this sermon on the fugitive slave bill in 1851.

IN ITS APPLICATION TO

THE FUGITIVE SLAVE BILL.

A SERMON

ON THE

DUTIES MEN OWE TO GOD

AND TO GOVERNMENTS.

DELIVERED AT THE CENTRAL PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH,

BUFFALO, ON THANKSGIVING DAY.

BY

JOHN C. LORD, D. D.,

(Pastor of said Church)

AUTHOR OF “LECTURES ON GOVERNMENT AND CIVILIZATION .”

SERMON

Tell us therefore, What thinkest thou? Is it lawful to give tribute unto Caesar or not? But Jesus perceived their wickedness, and said, Why tempt ye me, ye hypocrites? Show me the tribute money. And they brought unto Him a penny. And He saith unto them, Whose image and superscription? They say unto Him, Caesar’s. Then saith He unto them, Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God, the things that are God’s. — Matt. xxii. 17-21.

We are summoned today by the proclamation of the Chief Magistrate of this State, to consider and acknowledge the mercies of God during the year that is past. As individuals, for ourselves, and our households, it becomes us to acknowledge our personal deliverances, and the varied proofs of the Divine goodness which we have experienced since we last assembled to render our annual tribute of praise, prayer, and thanksgiving to Him — “who causeth the outgoings of the morning and the evening to rejoice; who giveth the early and the latter rain’ who appointeth fruitful seasons and abundant harvests; who openeth his hand and satisfieth the desire of every living thing.” As citizens, it concerns us to consider the general prosperity of the State and the Nation, to notice the various tokens of the Divine mercy in regard to the preservation of the free government under which we live, founded by the sacrifices of our pious ancestry and perpetuated, as we may well believe, for this reason, among others, that their “prayers are yet had in remembrance before God, and their tears preserved in his bottle.” As individuals, our presence in this house today is a proof of the personal mercies which should lead us to offer the acceptable sacrifice of praise. Some who once sat with us in this sanctuary have gon to the congregation of the dead; deaf to the requiem which the winds of winter are now mournfully murmuring over their graves insensible to all sounds, until the palsied ear shall hear the “voice of the archangel and the trump of God;” others are upon beds of sickness, pain, and sorrow, and know not whether they shall enter again the house of prayer, to mingle their praises with yours or pass from the couch of suffering to the life to come, to hold the mysteries of the unseen world, and worship with that august thong, that “innumerable company of angels and spirits of just men made perfect,” who fill the arches of Heaven with the voices of praise and thanksgiving ascribing “blessing and honor and dominion and power to Him that setteth upon the throne, and to the Lamb for ever and ever.” Some are full of affliction oppressed with poverty or overwhelmed with reverses, which prevent them from mingling with us in the worship of the sanctuary on this day of thanksgiving : and alas! that it should be so — there are others who are full of prosperity, “whose eyes stick out with fatness, who are not in trouble as other men,” who are so unmindful of their dependence upon Him in “whom they live and move and have their being,” so regardless of all the goodness and mercy of God, tha they never darken the doors of the house of prayer, and never unite in the worship and praise of the Father of mercies. But by our presence in this place today, we are seen to be the witnesses of the Divine goodness, we acknowledge our selves the recipients of unnumbered favors, we propose to offer the sacrifice of thanksgiving, and call upon our souls and all within us to magnify the name of our Father, Preserver, Benefactor, and Redeemer.

But not alone for private and personal mercies should we render thanks today. As citizens of this State, and of the great Republic of which it is the chief member, we are called to consider the preservation of public tranquility the adjustment of sectional difficulties, and the continuance of the bonds of our union, amid excitements which threatened its integrity; amid a storm, the original violence of which is manifest in the clouds which yet muttering in the distance. It is not necessary to adopt the opinions of the extreme alarmists in either section of the country to conclude that great dangers have threatened, if they do not still, threaten, the union of these States. It does not require very great discernment to see that the continued agitation of the vexed question of Slavery, producing alienation and distrust between the North and the South must, in the end, either sever the bonds between the free and the salve states, or render them not worth preserving. A unity maintained by force, if this were possible, would not pay the cost of its keeping. If, in the heat of the existing controversies, these two great sections of the Union come at last to forget their common ancestry, and the mutual perils shared by them in the revolutionary struggle; if South Carolina and Massachusetts, who stood shoulder to shoulder in the doubtful contest for American freedom, come to disregard the voices of their illustrious dead, who lie side by side in every battle-field of the Revolution; if Virginia and New York refuse, in the heats engendered by this unhappy strife, to listen longer to the voice of Washington, warning them in his farewell address of this very rock of sectional jealousy and alienation; if the words of the Father of this country are no longer regarded with reverence in the ancient commonwealth of his birth, or in the great State whose deliverance from a foreign enemy was the crowning achievement of his military career; and if the compromises upon which the Union was consummated, continue to be denied or disregarded there is an end of the confederacy. If the stronger should crush the weaker, and hold on to an apparent union with the grasp of military power, it would no longer be a confederacy but a conquest. When there is no longer mutual respect; no more fraternal forbearance; no more regard for each other’s local interests; no more obedience in one section to the laws which protect the guaranteed rights of the other; the basis of union is wanting, and nothing but a military despotism, with a grasp of iron, and a wall of fire, can hold the discordant elements together.

In the discussions which the recent agitations of the country have originated, grave questions have arisen in regard to the obligation of the citizen to obey the laws which he may disapprove; appeals have been made to a HIGHER LAW, as a justification, not merely of a neglect to aid in enforcing a particular statute, but of an open and forcible resistance by arms. Those subject to the operations of the recent enactment of Congress in regard to fugitive slaves have been counselled from the pulpit, and by men who profess a higher Christianity than others, to carry deadly weapons and shoot down any who should attempt to execute its provisions. The whole community at the North have been excited by passionate appeals to a violent and revolutionary resistance to laws, passed by their own representatives to sustain an express provision of the constitution of the United States, which if defective in their details, are yet clearly within the delegated powers and jurisdiction of our national Legislature. The acknowledged principle that the law of God is supreme, and when in direct conflict with any mere human enactment renders in nugatory, has been used to justify an abandonment of the compromises of the Constitution; an armed resistance to the civil authorities, and a dissolution of that Union with which are inseparably connected our national peace and prosperity. The consideration of the duties which men owe to God, as subjects of his moral government, and which, as citizens, they owe the commonwealth, is at all times of importance, but now of especial interest in view of the agitations of the day. It is high time to determine whether one of the highest duties enforced by the Gospel, obedience to the law of God as supreme, can be made to justify a violent resistance to the late enactment of Congress; whether or Christianity enjoins the dissolution of our Union; whether the advocates of a higher law stand really upon this lofty vantage ground of conscience, or are scattering “firebrands, arrows, and death,” either under a mistaken view of duty, or the impulses of passion and fanaticism, or inflamed by the demagogueism, which, if it cannot rule, would ruin; which, like Milton’s fallen angel, would rather “reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.”

That this subject is not out of place in the pulpit, is manifest from the fact that it is strictly a question of morals. Our duties to God constitute the subject matter of revealed religion, and their enforcement is the great business of the Gospel minister; our duties to government FLOW OUT OUR RELATION TO THE SUPREME GOVERNOR, as well as our relations to each other, and are clearly pointed out and forcibly enjoined in the Gospel. “Put them in mind.” Says an Apostle, “to be subject to principalities and powers; to obey magistrates; to be ready to ever good work:” “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers; the powers that be are ordained of God.” In the text, we are informed of an attempt made by the Jewish casuists to ensnare our Lord to Caesar; it being supposed by them, that any reply he could make would lead him into difficulty; for the Jews were perpetually galled by the Roman yoke, and any response favoring their oppressors would have aroused their indignation; while, if the lawfulness of tribute were denied by the reply of our Lord, it would have given his enemies ground to accuse him before the authorities, of sowing sedition. If our savior, in response to the question of the lawfulness of tribute, should answer in the affirmative, the Jews would stone him; if in the negative, the Romans would arraign him as a violator of law. He who knows all hearts perceived their wickedness, and said, “Why tempt ye me, ye hypocrites? Show me the tribute money. And they brought unto him a penny. And he said unto them, Whose is this image and superscription? They say unto him Caesar’s. then said he unto them, Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God, the things that are God’s.” Well might “they marvel and go their way,” baffled by the answer of divine wisdom. Our Lord escaped their malice by stating the true principle on which the obedience of the citizen is demanded by government, in the legitimate exercise of its powers. The coining of money is an act of sovereignty; the impress of Caesar upon the penny was proof that the Romans possessed the government of Judea, de facto, and were therefore, to be obeyed as the supreme authority in all civil enactments; while any attempt to interfere with the religious principles or practices of the Jews might be conscientiously resisted.

We take the ground, that the action of civil governments within their appropriate jurisdiction is final and conclusive upon the citizen; and that, to plead a higher law to justify disobedience to a human law, the subject matter of which is within the congnizance of the State, is to reject eh authority of God himself; who has committed to governments the power and authority which they exercise in civil affairs. This is expressly declared by the Apostle in the Epistle to the Romans: “Let every soul be subject to the higher powers, for there is no power but of God; the powers that be are ordained of God; whosoever therefore, resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God. For he (that is the civil magistrate) beareth not the sword in vain, for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil. Wherefore ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath but also for conscience’ sake; render therefore all their dues, tribute to whom tribute is due, custom to whom custom, fear to whom fear, honor to whom honor.”

The language here cannot be misunderstood. Obedience to governments, in the exercise of their legitimate powers, is a religious duty, positively enjoined by God himself. The same authority which commands us to render to God the things which are God’s enjoins us, by the same high sanctions to render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s.

The following general principles may be deducted from the sacred Scriptures, and from the example as well as the teachings, of our Lord and his Apostles.

First — Government is a divine constitution, established at the beginning by the Creator, which exists of necessity, and is of perpetual obligation. Men are born under law, both as it respects the Law of God and the enactments of States. By the ordination of the supreme law, they owe allegiance to the country of their birth, and are naturally and unavoidably the subjects of its government; their consent to this is neither asked nor given; their choice can only respect the mode, never the fact of Government. The mutual compact without warrant from the word of God, and contradicted by all the facts in the case. We might as well affirm that men agree to be born, and to be subject to their parents, by a mutual compact, in which the child surrenders certain rights for the sake of parental protection, and the parent covenants to provide and govern on the promise of obedience. The statement in the last case is no more absurd than in the first. In the family is found the rudimental government, and the fifth commandment has always been understood by Christians as ordaining subjection to magistrates as well as parents.

Second — Governments have jurisdiction over men in all affairs which belong peculiarly to the present life; in all the temporal relations which bind societies, communities and families together in respect to all rights of person and property, and their enforcement by penalties. General rules are, indeed, laid down in the Scriptures for the regulation of human conduct, but God has ordained the “powers that be” to appoint their own municipal laws, to regulate and enforce existing relations, and to execute judgment upon offenders, under such form of administration as shall be suitable to the circumstances of the people and chosen by themselves. Governments as to their mode, do not form but follow the character and moral condition of a people, and are an indication of their real condition, intellectually and morally. The idea that the mere change of the form of a despotic government will necessarily elevate a nation, is a mistaken one. A people must be elevated before they can receive free institutions. The mode of government is the index and not the cause of the condition of the different nations of the earth, which may be demonstrated by the history of empires and states, and by the fain efforts, recently made in Europe, to adopt our institutions without the moral training and preparation which can alone make them either possible or valuable. France, today is a despotism under the forms of a free government, and maintains her internal tranquility by a hundred thousand bayonets.

Third — In regard to his own worship, and the manner in which we are to approach Him, the Supreme Governor has given full and minute directions. He has revealed himself, his attributes, and the great principles of his government, which constitute the doctrines of Christianity; and has conferred upon no human authority the right to interfere by adding to or taking from them. IN THE THINGS THAT BELONG TO HIMSELF, God exercises sole and absolute jurisdiction, and has, in regard to them, appointed no inferior or delegated authority.

Fourth — The decisions of governments upon matters within their jurisdiction though they may be erroneous, are yet, from the necessity of the case, absolute. Every man has a right to test the constitutionality of any law by an appeal to the judiciary, but he cannot interpose his private judgment as justification of his resistance to an act of the government. Freedom of opinion by no means involves the right to refuse obedience to law; for, if this were so, the power to declare war and make peace; to regulate commerce and levy taxes; in short, to perform the most essential acts of government, would be a mere nullity. No statue could be executed on this principle, which would leave every man to do what seemed right in his own eyes, under the plea of higher law and a delicate conscience. Even courts of justice, which are the constituted tribunals for ascertaining and determining the validity of all legislative enactment, by bringing them to the test of constitutional law and first principles, as well as for the decision of causes arising under the law in relation to persons and property, may form an erroneous conclusion; for no mere human wisdom is infallible; yet their final decisions are binding, from the same necessity. The fact that an innocent man may be condemned and suffer the penalty of law which he has never broken, might as well be urged to impeach the authority of a judicial decision as that the fallibility which is manifest in hasty and unwise legislation, should be alleged as an excuse for resistance to a particular statute.

The private judgments of individuals, for insurance, that all wars are unlawful, even those which are defensive; or that the existence of slavery is per se, sinful, is no just ground of resistance to the government which declares war, or the legislation which recognizes domestic servitude, and regulates it. Both these subjects are properly within the jurisdiction of civil government. The State may engage in an unjust war, but does this discharge the subject from his allegiance? No sane man will affirm it. the government may recognize an oppressive form of domestic servitude, or enact laws in relation to which are deemed by many oppressive. Is this a just ground of forcible resistance on Christian principles? No intelligent man who regards the authority of the Bible can consistently maintain such a position. Many at the North who assert such opinions have long since rejected the authority of the Word of God and have in their conventions publicly scoffed at divine as well as human authority.

But the position we have taken, that the decisions of governments are final in cases where they have jurisdiction, even when mistaken or oppressive, is not only sustained by the passages which have been cited from the Scriptures, but also by the example and practice of the primitive Christians. The words of our Saviour in the text, and of the Apostle, in his Epistle to the Romans, while they have a general application to all times and all governments, had a particular reference to the existing authorities or Rome, which were not only despotic in their general administration but peculiarly oppressive in their treatment of the infant church. The government under which our Saviour and the Apostles lived, and of which they spake, was habitually engaged in aggressive wars, aiming at the conquest of the world. Slavery was universal throughout the Roman Empire, and the laws gave the master the power of life and death over his servant. Did the Saviour and his Apostles, on this account, reject their authority, or incite their disciples to disobedience and resistance? Did they interfere with existing civil institutions, urging the slave to escape from his master, the citizen to rebel against the magistrate? Their conduct was the exact reverse of this; they preached to the master forbearance and kindness — to the observant submission and obedience — to both, the Gospel. Paul sent Onesimus back to his maser, on the very principles which he enjoined upon the Romans — subjection to existing civil authority. The inspired teachers of Christianity instructed both masters and slaves in regard to the duties which grow out of the institution of Slavery, without either approving or condemning the relation itself. They exhorted Soldiers on the same principle, to be content with their wages, and to forbear from mutiny and cruelty; without offering any opinion concerning the justice or injustice of the Roman wars. They spake indeed of a promised and predicted day, when wars, tumults and oppressions should cease, when at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, and there should be none, any more, to hurt or molest in the Mountain of the lord. The early Christians were, beyond controversy, obedient to the injunction of the Apostle. They obeyed law even when it was onerous or unjust. They had civil and military appointments under the Roman government in which they refused not to serve; they were obedient to the existing civil powers, in all matters within the jurisdiction of the State; they were no abettors of sedition and strife. Whole legions in the armies that were sent out for conquest by Rome, where composed of Christians, who were, doubtless, drawn in the general conscription for this service, and who felt it to be their duty to “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s;” however much they might dislike the business of war. Not until Caesar intermeddled with the things of God; not until, passing the legitimate jurisdiction of civil government the Roman magistrate commanded them to adore the image of the Emperor, and to offer incense to false gods; did the Christian refuse obedience. But here he was immovable; no flattery could subdue, no terrors appall him. Every engine of torture, which the barbarous ingenuity of Rome could invent failed of its purpose. They were tortured by fire; they were cast out to wild beasts; they were exposed in the amphitheater to the gaze of thousands, who mocked their dying agonies. Like the ancient prophets, “they were stoned; they were sawn asunder; they were tempted; they were slain with the sword; they wandered in deserts and mountains, in dens and caves of the earth.” It was enough that the Master had said, “render to God the things which are God’s.” Nor was their resistance that of armed and violent men; they assassinated no officers, and excited no seditious, but, after the example of their Lord, suffered with that passive firmness, which is the highest form of courage. But it may be replied to this, Your argument proves too much. You reaffirm the old doctrine of tyrants of passive obedience and non resistance; your position would render all revolutions unlawful; all changes of government impossible. To this it may be said, that it does not belong to the Church in her organized capacity, nor Christians, considered solely as such, and with reference to their religious duties, to revolutionize governments; for this reason, the Gospel is silent on this subject, while enforcing the general duties of the citizens under all governments de facto, whether revolutionary or otherwise; whether despotic or democratic. That, under certain circumstances, the people, by which is meant the large majority, have a right to revolutionize a government, is conceded. Presbyterians have ever resisted the High Church and tory doctrine of the divine right of Kings, in the State; and Prelates, in the Church. They stood, to a man, with the Patriots who achieved under God the independence of our beloved country; they have maintained the principles of civil and religious liberty, at the hazard of life and fortune, in both hemispheres. The Presbyterians of Scotland, and the Puritans of England, were the founders of English liberty, by the admission Hume himself, who hated them with infidel and tory extravagance. The right of a people to select their own form of government, a question entirely distinct from the fact of government, which is of necessity by a Divine Constitution, has ever been maintained by us as existing, not only in the nature of the case, but as warranted by the Word of God; of which, the choice by the Hebrews of a King, and the rejection of their ancient democratic mode of government, which they received from the Supreme Lawgiver himself, is an example. This change was expressly allowed them at their desire, though with a plain intimation that their choice was a bad one. So the revolt of the ten tribes upon the declaration of Rehoboam, that he would govern them in a despotic and arbitrary sway, that “his little finger should be thicker that his father’s loins,” appears afterwards to have been sanctioned by the Most High; who gave them Jeroboam for a King, and rent Israel for every from the house of David and Solomon.

The right of revolution is a civil right, which can be properly exercised only, by a decided majority, under circumstance of aggravated oppression and upon a reasonable assurance of success. It is not for the Church, as such, to determine when a just ground for revolution exists, it belongs to the body of the people in their civil capacity. If, in the judgment, for example, of a great majority of the citizens of the United States, it would be better to abandon our Union; if the South in her exasperation against the North, for interference with her domestic relations, and in the vain hope to secure an increase of wealth and population corresponding with that of the free States, desire disunion; if we of the North are unwilling to observe the guarantees of the Constitution, and think it worth while to abandon the advantages of the confederacy for the sake of making our territory a place of refuge for runaway slaves; the Union will be dissolved by a revolution, the most disastrous the world ever saw. But while the Constitution remains, while the Government, continues let us observe the laws; let us not justify murder and sedition; and least of all, let us not talk of a higher law, which absolves men from obedience to a Constitution which they have sworn to maintain. If there be any higher law, it is the law of resistance and revolution; and the sooner this is understood and openly avowed, by the ultraists and fanatics both North and South, the better for the country. The people of these United States are not likely, with their eyes open, to plunge into the gulf which disunionists are opening up beneath their feet; and when the real designs of these men are seen, when they openly avow that a revolution is the end of their movement, we believe that they will be crushed under the weight of public indignation.

But, in regard to the question of a higher law, which we think we have demonstrated cannot be urged to annul the legislation of a state, in relation to any matter properly with its jurisdiction, it may be further replied, that it is not yet proved that the enactment or recognition of Slavery is within the powers divinely delegated to Governments; that it is against the Supreme Law, and therefore all human legislation on the subject is inoperative and void. To this we reply, in the first place, that there are many evils incident to the fallen condition of our race, such as War and Slavery, the existence of which is to be regretted, but which are necessarily in the actual condition of mankind, the appropriate subjects of municipal regulation. A state involves not only the authority of the Magistrate to punish criminals, but of the expression “he beareth not the sword in vain.” But the state having this right may and do often abuse it by aggressive wars, the injustice of which, we have already seen is no ground of forcible resistance to the civil authority. So the right of legislation in regard to servitude as a punishment for crime, or as a method for disposing of prisoners taken in war, has been exercised any intelligent and fair-minded man. The state having jurisdiction of the subject may, as in the waging of an aggressive war, abuse their power, by enacting unjust and oppressive laws of servitude; but is such legislation therefore inoperative and void? To affirm this, is to contradict the decision of the Apostle in his Epistle to the Romans, and to subvert every established principle, whether human or divine, on which rests the authority of civil government. In certain conditions of society Slavery is universal; it was recognized and regulated by law in all the free states of antiquity; it is the first movement towards civilization by savage and barbarous nations to reduce their captives taken in war, to slavery, instead of subjecting them to torture and death. A recent traveler in the vast Empire of China, Mr. Lay, affirms that in that country the institution of Slavery is a positive blessing, as it prevents infanticide by the poorer classes, and provides for multitudes who must otherwise perish of want. That it exists in a mild form in China is admitted; but the question does not depend upon a comparison of the laws of different countries on this subject, but whether it is a condition of society which can in any case be allowed; whether civil governments have any authority or jurisdiction to enact laws upon the subject, or in any way to recognize or regulate it.

But there is higher authority for the determination of this question, than any thing we have yet suggested. The existence of domestic Slavery was expressly allowed sanctioned and regulated by the Supreme Lawgiver, in that divine economy which He gave the Hebrew state. The fact is open and undisputed; the record and proof of it are in the hands of every man who has in his possession a copy of the Bible. All the ingenuity and art of all the Abolitionists in the United States Can never destroy the necessary conclusion of this admitted divine sanction of Slavery, that it is an institution which may lawfully exist, and concerning which Governments may pass laws, and execute penalties for their evasion or resistance.

To allege that there is a higher law, which makes slavery, per se, sinful, and that all legislation that protects the rights of masters and enjoins the redelivery of the slave, is necessarily void and without authority, and may be conscientiously resisted by arms and violence, is an infidel position which is contradicted by both Testaments; — which may be taught in the gospel of Jean Jacques Rousseau, and in the revelation of the Skeptics and Jacobins, who promised France, half a century ago, universal equality and fraternity; a gospel whose baptism was blood, a revelation whose sacrament was crime; but it cannot be found in the Gospel of Jesus Christ, or in the revelation of God’s will to men. We do not mean to affirm that sincere and conscientious persons may not be found who have persuaded themselves that forcible resistance to slavery is obedience to God; and that in the increased light of the nineteenth century, the example of the Jewish economy, and the teachings and practice of our Lord and the Apostles, are antiquated and of no binding force upon the consciences of men. Such honest but mistaken persons should remember, that if the institution of slavery is necessarily and from it’s nature sinful now, it must always have been so; as universal principles admit of no change, and their argument is, therefore, an impeachment of the benevolence of God, and a denial of the supreme authority of the Gospel, as a system of ethics. They must, to sustain their position, assume that we are wiser and better men than the Saviour and the Apostles, and that the government of God and the Gospel need revision and emendation. Such a conclusion is inevitable from the premises, and I would affectionately warn all who have named the name of Christ, and who have been betrayed by passion or sympathy into such a position to see to it before they take the inevitable plunge, with the Garrison school, into the gulf of infidelity. I would respectfully entreat them to remember that this is not the first proclamation, “Lo, here is Christ, or there,” which has proved a device of the adversary; that Jacobins, Fourierites, Communists, and Levellers of all sorts, reject the Gospel on the ground that it does not come up to their standard of liberty, equality and fraternity, and has no sufficiently comprehensive views of the rights of man. Those who preach the Gospel ought specially to remember that our race are apostate, and live under a remedial government; and that is our mission to deal with the world as it is, and men as we find them, just as did the Saviour and the Apostles — remembering that here we have no continuing city,” and that the Gospel does not propose to us an equalization of human conditions in time; that “there remaineth a rest for the people of God,” and to this, the Master of life and his Apostles pointed the rich and the poor, the high and the low, the bond and the free. They made it no part of their work to array the prejudices of one class against another; to discontent the slave with his position; or the citizen with the government; but treated all these things as of inferior consideration, compared with the hope of another and a better life, through the blood of atonement.

The comparative mildness of Hebrew slavery which is alleged, if it were true, is of no moment in the decision of the question before us; for it is not, whether American legislation on this subject be unwise and unjust, but whether the institution of slavery is necessarily sinful, and all legislation on the subject void for want of jurisdiction, and because of a higher law that prohibits its existence.

Domestic slavery, in this country, is older than the Constitution; it had existed for several generations before the Revolution. The people of the North, in their union with the slave States under a General Government upon the adoption of a common Constitution, bound themselves to respect the institution of slavery as it then existed, so far as to deliver up fugitives to their masters. What has been said proves, we think, that such an arrangement was not void as being against a higher law, and consequently any legislation, by Congress, which fairly carries out this provision, and enforces this guarantee, is constitutional and lawful, and cannot be resisted upon any moral grounds. Whether the law is the best or the worst that could have been devised, is not the question here, nor is it really the question with the country; for it is the recognition of Slavery by the Constitution, and the right of recapture which it confers, which lies at the bottom of this agitation; all the rest is merely for effect, vox et preterea nihil [voice and nothing more], and those who recommend the violation of this law, would undoubtedly advise resistance to any enactment of Congress which would carry out the provision of the Constitution for the restoration of fugitive slaves.

It is somewhat singular that those whose consciences have been so much aroused in regard to a higher law that the constitution, should have forgotten in their contemplation of moral and religious questions, that the observance of the compact between the North and the South falls within the moral rule which enjoins good faith, honesty, and integrity among men. Until this compact is rescinded by the power that made it, and by the parties who assented to it, its fulfilment is required by every principle of common honesty. With what pretence of right can the North say to the South, we will hold you to your part of the bargain; you must remain in the Union, but we have conscientious scruples in regard to performing our part of the agreement. Is this language of good faith and integrity? Would it be thought honest in any private transaction or compact? Is it for those who threaten the South with force in case of their resistance of Constitutional enactments — who are themselves advocating the violation of the laws which protect the rights secured to the slave States by the Constitution — to talk about higher laws and sensitive consciences? Does the assertion, so often made, that there is no danger of disunion if the law of recapture if violated; that the south are not strong enough to set up for themselves; that they need the protection of the North to prevent a servile insurrection, add any thing to the moral beauty of this position What is this but the divine right of lawless force, the higher law of the strongest? What is this but a disavowal of all regard for the claims of the weak? In the words of a Highland song of the olden time,

“For why? because the good old rule

Sufficeth them; the simple plan,

That they must get who have the power,

And they must keep who can.”

May Vermont be permitted to pass laws to evade and prevent the execution of the legislation of Congress, and south Carolina threatened with investment by sea and land, by the army and navy of the United States, for doing the same thing? Is this good faith between sovereign States? Nay, is it common honesty among men? “I speak to wise men, judge ye!”

If we are comparatively so much stronger than the South, as is alleged, is it magnanimous, is it just, for us to take advantage of their weakness to violate their constitutional rights? If they look upon the greater prosperity of the North with a degree of jealousy, and are the more sensitive on that account upon any appearance of a disregard, on our part, of the guarantees of the constitution, there is the more reason for our forbearance; especially when it is considered that in the very formation of the Union, there was an implied understanding that good will and forbearance should characterize the intercourse of the parties; “that “Ephraim should not vex Judah; or Judah, Ephraim” Why should the Saxon obstinacy of the North and the Norman pride of the South be forever excited by these unhappy disputes in regard to slavery; a question which time, and patience, and God’s providence can alone resolve? The South are not so dependent upon us as we imagine; in the case of a servile insurrection they would hardly look for aid, in the present state of things, from the North, and our constant allegations of their weakness constitute one ground of their dissatisfaction; and one temptation to a separation, that they may prove to the North and the World that they can take care of themselves. They have the old Norman temper; the blood o the Cavalier predominates over that of the Puritan in the southern States, and they would rather see their territory desolated with fire and sword than yield a single point of honor — than to feel, much less to acknowledge, that they are dependent upon then North for protection against their own slaves. It is evident that the great body of the people at the South are attached to the Union, and will not readily yield it; but it is equally manifest that they have demagogues and traitors there, who desire to exercise dominion and lordship in a Southern Confederacy that shall extend from Virginia to Cuba; who, like some at the North would rather be Presidents and Secretaries by a division of the country, than to be out of office by its continued union.

If such men would boldly announce their design if they would form an anti-union party, and present this question of a revolution in our government and abandonment of our Constitution before the people, it would go far to dissipate the danger which threatens the Republic, and to quiet the perpetual agitations that are wearing out the strong bands that hold us together. For whatever allegations may be made that there is no danger of disunion; whatever cries of “peace, peace” may be reiterated by men who are doing what they can to nullify their own predictions; we may be assured there is treachery and danger all around us. The separation of large communions of Christians into Northern and Southern Churches was one of the first signs of evil omen to the country. But two of the leading Protestant denomination remained united. 1 I thank God that one of them is the Presbyterian Church, who are still one in form and fact, in heart and spirit from New York to New Orleans from the Atlantic to the Pacific, having long since met this question and settled it, finally and peacefully, upon Gospel principles. The constant agitation of the slavery question at the North, the untenable positions assumed, the fierce denunciations, the bitter revilings, the contumelious epithets which have been heaped upon our Southern brethren and all who would not consent to unite in a crusade against them, are producing their legitimate fruits of alienation, distrust, and hatred. If no positive proof exists of a conspiracy among certain hot-headed and ambitious demagogues at the South, to dismember the Union; that a Southern Confederacy may be formed which will make them all great men; yet, it is manifest that such a design has been formed, either with or without concert, among a class of abstractionists there, who are cooperating with the abolitionists, at the North to agitate and inflame the public mind, until a revolution is inevitable. The recent settlement of the vexed sectional questions, which was hailed by the country with confidence and hope, is sought to be disturbed not only by denunciation, but by a violent resistance of the laws enacted, and this, too, before sufficient time has elapsed to test them. Every kind of phantom is conjured up; visions of free men forcibly hurried into slavery; appalling pictures of cruelty and injustice are continually exciting the public mind; though but six captures are said to have been made under the fugitive slave law since its passage, and with two exceptions it is believed the alleged fugitives have been discharged or redeemed. If those who harrow up the sensibilities of innocent and ignorant persons by these dreadful imaginations, are sincere in the fears which they express that free persons of color are likely to be enslaved by the existing law, it shows how utterly fanaticism disregards fact; if they are opposed to the redelivery of fugitive slaves under the provision of the Constitution, the only honest position they can take is to declare at once and openly for a dissolution of the Union, or the subjugation of the South, by force of arms, to the North.

Before we leave this subject, we ought to notice the probable results of a dissolution of the Union. What its advantages have been, are matters of history and experience. Under God, the Union has made us a great and prosperous people. We have maintained peace at home and commanded respect abroad; our country has been the asylum of the oppressed of every land, the permanency of our institutions has been hailed as the last hope of freedom for the world. Every State has preserved its local sovereignty, while obedient to the general law. Every citizen has enjoyed the largest liberty consistent with the preservation of order, and dwelt under his “own vine and fig tree, with none to molest him or make him afraid.” We may say with the Psalmist, “the lines have fallen unto us in pleasant places, and God has given us a goodly heritage.”

On the other hand, all the disastrous consequences which must flow from disunion, are known only to Him who sees the end from the beginning. One thing is certain, no benefit can flow from a separation of the States, to that unhappy race about whom this whole controversy exists. No possible or conceivable advantage can arise to them if the Union were sundered tomorrow. Their condition at the North would not be improved, their state at the South would be rendered so far worse, as an increased severity of legislation might be required to prevent their escape to an enemy’s frontier. If a small increase of the number of those who escape to the North should be secured, which is doubtful, the question arises, and it is a grave and unsettled one, whether their residence with us is a substantial improvement of their condition. The forms of freedom are of little consequence to him who is made by color and caste a “hewer of wood and a drawer of water.” That the colored race are capable of elevation I have always maintained — just as capable as the white, if they can be made to possess the same advantage; but I am fully persuaded that colonization can alone secure those advantages and give to the African that which alone makes personal freedom and free institutions valuable. In any view of the subject, the agitations and divisions of a country on the question of slavery, and the revolution which may result from them, are of no conceivable consequence to those about whose interest the controversy exists. A more unprofitable and inconsequential abstraction was never before made to disturb the peace, and hazard the existence of a great Empire.

With reference to the positive evils of a revolution, it is the opinion of the most profound statesmen in the country, that a division of the Union must result in a perpetual war between the two sections. This agrees with all the facts of History, and the conclusions of the most profound observation upon human nature. Peace would be impossible under these circumstances. A line of fire would mark the boundary between the free and slave States, from the Atlantic to the Mississippi to the Pacific. The blackened roof trees of all human habitations, for miles on either side of this accursed line, would demonstrate the bitterness of a conflict between men of the same blood, and verify the declaration of Scripture that “the contentions of brethren are like the bars of a castle.” Across the entire continent the boundaries of the two governments would be marked by conflagration, rapine and violence. Armed plunderers, with whom war would be the excuse for murder and robbery, would make a desert of the country adjacent on either side, which would soon be known over the whole world by two names. ACELDAMA and GOLGOTHA, a field of blood — a place of skulls. There are no visionaries so wild as those who dream that this vast Empire can be disunited peacefully, or that peace can ever be maintained between the North and the South, under separate governments, with all the old memories, the bitter prejudices, the unavoidable rivalries, the unceasing disputes of jurisdiction, with the mouth of the Mississippi in one territory and its sources in the other, and with the ominous slave question embittered a thousand-fold by the dismemberment of the country. If, in this unnatural contest, the North should prevail over the South, it would be making a desert of the territory from the Potomac to the Gulf of Mexico, and by the destruction of both the races who now occupy it; a victory barren of glory — the jest of tyrants, and the scorn of the world.

But the spirit of disunion, once evoked, may extend its malign influences until, the supposition, having accomplished the ruin of the South, the states at the North should divide and set up for itself, and like the petty governments, or rather anarchies, of South America, command neither respect abroad nor obedience at home.

The beginnings of strife are like the letting out of waters, and to this miserable conclusion at last, these unhappy divisions may bring us. It is an old adage, that those whom God would destroy he first makes mad; and it would seem that nothing short of judicial blindness can lead into the further agitation of a question fraught with ruin to our beloved country, and to the hopes of political freedom over the entire globe. The dismemberment of this country will be the death-blow of its prosperity. Our rights will be no more regarded abroad or our laws at home, for our strength will be exhausted in our domestic wars; property both at the North and South, will immediately and decidedly depreciate in value; all confidence in the stability of grave of the American Constitution. Worst of all , this disastrous event will have been brought about by no foreign war, by no struggle with the civil or religious despotisms of the world; by no honorable resistance to foreign interference; but by the madness of men ready to sacrifice to one idea, and that an impracticable one, to one principle, and that a false one the legacy of Freedom and Union which we hold from our fathers, and which we are bound to transmit to our children every consideration of patriotism by every obligation of religion; and failing to do which, both earth and Heaven will cry out against us, as false to the trust committed to us by our noble ancestry; false to our allegiance and our oaths; false to our children and posterity ; false to our religion and to God, who has committed to our keeping the ark of civil and religious liberty, for the benefit of our race, to be held as a sacred deposit for the world. The plea of sympathy with the colored race, in view of their degraded condition, however suitable such sympathy may be, and demanded by Him who hath made of one blood all nations and races, to dwell together on the face of the earth, will never avail to justify an agitation which is useless to them and ruinous to us. A man who should expose a whole community to destruction, under the plea of delivering one of its members from servitude, or who should fire his neighbor’s dwelling for the same purpose, at the risk of a conflagration which must consume both master and slave, and even expose his own house and his own children to a miserable death, could hardly be counted a philanthropist, or find a justification of his conduct in any abstract question of human rights. I would that I had a voice to penetrate every habitation in this great Empire, to reach every ear from ocean to ocean, from Maine to Florida — to entreat my countrymen to pause from a controversy from which there will soon be no retreat, and of which, if protracted, there can be but one issue — the dissolution of the Union and the ruin of the Republic. By their duty to God and the Government, I would implore them to the obedient to the laws; by their regard for their children, by their respect for the interests of our common humanity, I would beseech them to take care of the Commonwealth, than which there is no higher law for the Christian citizen. I would appeal to the North and the South, by their common ancestry, by the august memories of the revolutionary struggle, by the bones of their fathers which lie mingled together at Yorktown and Saratoga, at Trenton and Charlestown, by the farewell counsels of the immortal Washington, to lay aside their animosities and to remember that they are brethren. I would remind them that the Union has given us the blessings which we enjoy — that under its Flag our victories have been won; our borders extended; our wealth and population increased; our ships respected in every port of every sea, until our national progress has excited the admiration or aroused the envy, of all the Nations and Potentates of the earth. I would warn them of that abyss of ruin which fanaticism and treason are opening beneath them; into which they would plunge our present fortunes and our future hopes,. I would beseech them to stand by the Union to obey the laws, to frown upon agitation, in this crisis of our beloved country. I would admonish them that failing to do this, failing to sustain the free institutions, and to regard the mutual compacts which we received from our fathers, we may expect as a consequence the curses of posterity, the contempt of the world, and the judgments of God. May the Ruler of nations avert from us these impending calamities. May the Holy Trinity, in whom our fathers trusted, gibe us, a s a people, the spirit of wisdom and understanding and of sound mine. May we hereafter on occasions like the present have a new motive of thanksgiving and praise in the proofs of the peaceful settlement of all sectional controversies — in the fact that the Ship of State, long tossed by tempests and threatened with destruction by conflicting and angry elements, is at last sailing in a calms sea, with a law-abiding crew. AND THE FLAG OF THE UNION NAILED TO HER MASTS.

Endnotes

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!