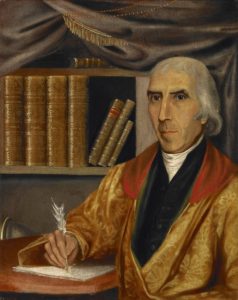

Jedidiah Morse (1761-1826) Biography:

Jedidiah Morse (1761-1826) Biography:

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.

Morse also held a lifelong interest in education. In fact, shortly after his graduation in 1783, he started a school for young ladies. As an avid student of geography, he published America’s very first geography textbook, becoming known as the “Father of American Geography,” and he also published an historical work on the American Revolution. He was part of the Massachusetts Historical Society and a member in numerous other literary and scientific societies.

Morse also had a keen interest in the condition of Native Americans, and in 1820, US Secretary of War John C. Calhoun appointed him to investigate Native tribes in an effort to help improve their circumstances (his findings were published in 1822). His son was Samuel F. B. Morse, who invented the telegraph and developed the Morse Code.

The present Situation of other Nations of

the World, contrasted with our own.

A

SERMON,

Delivered

At CHARLESTOWN,

In The

COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS,

February 19, 1795:

Being the Day Recommended by

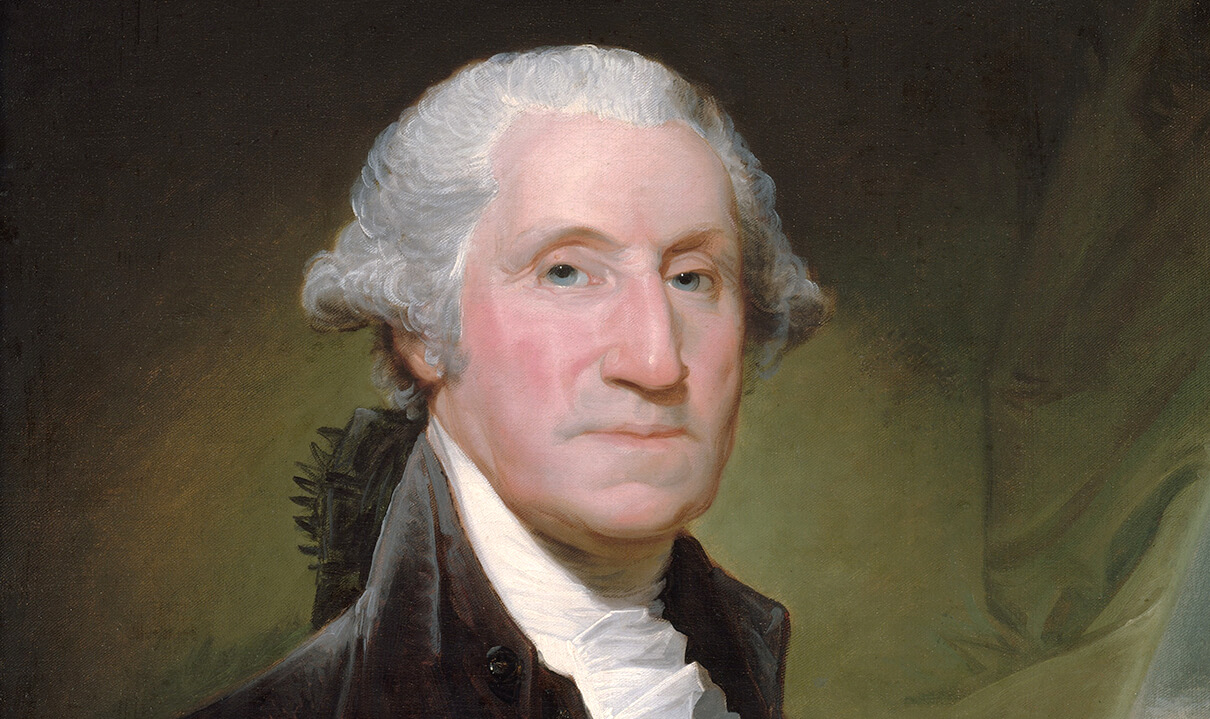

GEORGE WASHINGTON,

President of the United States of America,

For PUBLIC THANKSGIVING

And

PRAYER.

BY JEDIDIAH MORSE, D.D.

MINISTER OF THE CONGREGATION IN CHARLESTOWN.

To

The Congregation in Charlestown,

At whose Request is made publick,

The Following Discourse.

(Enlarged and illustrated with NOTES.)

Is Respectfully Addressed

By Their Affectionate

Pastor.

Charlestown, February 26, 1795.

DEUTERONOMY IV. 6, 8, 9.

Ver. 8. What Nation is there so great, that hath Statutes and Judgments so righteous as all this Law which I set before you this day.

Ver. 6. Keep therefore and do them, for this is your Wisdom and your Understanding in the sight of the Nations, which shall hear all these Statues, and say, Surely this great Nation is a wise and understanding People.

Ver. 9. Only take heed to thyself, and keep thy Soul diligently, lest thou forget the things which thine eyes have seen, and lest they depart from thy heart all the days of thy life; but teach them to thy sons, and thy sons’ sons.

My Brethren,

There cannot be a more pleasing sight here on earth, than a Christian assembly, impressed with a lively sense of the Divine goodness and bounty, and expressing in their countenances their heart felt joy, voluntarily convened, as we are this day, at the voice of our Chief Magistrate, to unite with our fellow-citizens, in rendering praise to Almighty God, for his manifold mercies. The pleasure excited, on such an occasion, is heightened by the consideration, that millions of people are, at the same time, uniting in this delightful service. How much greater still, would be this pleasure, if there were good reasons to hope, that all these millions were of the number of the true worshippers of God, and felt towards him true gratitude, or “Christian thankfulness,” for his mercies? Then our country would this day resemble the heavenly world; and there would be an addition, small, yet acceptable, to the incense of praise which is daily offered by the celestial choir to their heavenly Father. – May this gracious Being, by his good Spirit, sanctify and prepare our hearts, and the hearts of all his people assembled this day, for this pleasing employment, that so we may celebrate a rational and acceptable Thanksgiving to our God.

With a view to lead your minds to a survey of the various distinguishing blessings of divine Providence towards us as a nation, and to excite correspondent sentiments of gratitude, I have chosen, as the foundation of the present discourse, a part of the address of Moses to the children of Israel, which we have just recited.

The book of Deuteronomy contains a repetition of the principal events which happened to the children of Israel, and of the laws which God had given them, during their memorable forty years journey from Egypt to Canaan. The generation who heard these laws originally delivered, and were eye-witnesses of these wonderful things, having been cut off for their rebellion, it pleased God that Moses, for their instruction and warning, should recite them to the new generation before his death. This interesting rehearsal was made on the plains of Moab, by this eminent servant of God, “in the fortieth year, and the eleventh month,” [i] of their pilgrimage. It was the business of the last month of his life, when he was an hundred and twenty years old; and is a standing proof of the truth of what his historian relates of him, that “his nature force was not abated.” [ii]

To have beheld and heard this venerable leader, and Father of his people, rehearing to them the various wonders which God had wrought in their behalf – teaching them with the dignity and affection of a parent, that statues and judgments which God had given them by him – calling upon them to review the situation of other nations, in contrast with their own; and thus impressing them with a deep sense of the great and distinguishing blessings which they enjoyed, and of their consequent obligations to obedience – exhibiting before them the advantages that would accrue from a faithful regard to these excellent statutes and judgments, in point of national honor, dignity and happiness – warning them, with solemnity and earnestness, of the fatal consequences of disobedience, vain glory and ingratitude – and, finally, after pathetically exhorting them to obey and praise God for his wondrous goodness, closing the interesting scene with his paternal blessing. To have witnessed such a scene, must have been no less affecting them improving.

A scene, in several respects resembling this, we, my brethren, are invited, this day, to contemplate—One at least equally calculated to affect, to improve and animate our hearts. A nation, far greater than that which Moses addressed, is assembled this day before the Lord, by the recommendation of their venerable[iii] political Leader and Father—who, in respect to his talents as a general in war, and a chief Magistrate in civil affairs—his success in exercising these talents—his prudence, sagacity, and paternal care, vigilance and solicitude for the safety, peace and happiness of the people, and his possessing their entire confidence and esteem, may with singular propriety be compared to Moses.

This incomparable Chief—this Moses of our nation, in his admired Proclamation, invites his numerous and happy fellow-citizens, to learn, from “a review of the calamities which afflict so many other nations,” how to appreciate their own happy condition.” He rehearses to us the remarkable interpositions of Providence, in rescuing us from various dangers which threatened us, and enumerates the singular blessings “which peculiarly mark our situation with indications of the divine beneficence towards us.”

Behold the good man, deeply penetrated himself with the duty, “in such a state of things, of acknowledging, with devout reverence, and affectionate gratitude, our many and great obligations to Almighty God, and of imploring of him the continuance and confirmation of these blessings”—Behold him, in virtue of the authority annexed to his high office, “recommending” to the people at large, unitedly, on this day, to “render their sincere and hearty thanks to the great Ruler of Nations, for the manifold and signal mercies which distinguish our lot as a nation,” and pointing our attention singularly to these “signal mercies.”—Behold him, as the Father of his people, dispensing, in the most delicate and impressive manner, his wise and salutary instructions and admonitions—teaching us that “God is the kind Author of all our blessings”—that to him alone we must look for their continuance—that to him, we should feel under the most solemn obligations for these blessings, the immense value of which we should rightly estimate.—Warning us to guard against “arrogance in prosperity”—and against “hazarding the advantages we enjoy by delusive pursuits”—exhorting us, by a grateful, upright and suitable behavior, “as citizens and as men,” to secure to ourselves “the continuance of his favours”—and by these means to render this country, more and more a safe and propitious asylum for the unfortunate of other countries”—recommending, implicitly, what is the great basis of a Republican government—of equal rights, and of publick and social happiness—a careful attention to publick and domestick education, in order that “true and useful learning may be extended,” and “habits of sobriety, order, morality and piety diffused and established.”—Behold him, finally, closing the important summary, by calling on us to unite in the benevolent petition, that God would graciously “impart all the blessings we possess, or ask for ourselves, to the whole family of mankind!”—What an august scene, my brethren, is here presented for our contemplation!—How well calculated to excite supreme and fervent love and gratitude to the Father of Mercies—and lively emotions of sincere, subordinate affection and respect, for Him at whose call we are here assembled, and who has been honoured as the instrument of so much good to mankind!—In great truth may we adopt and apply the language of Moses and David—“Happy are ye,” oh ye citizens of united America—“Who is like unto thee, oh, people saved by the Lord, who is the shield of your help, and the sword of your excellency.”[iv]—“He hath not dealt so with any nation—Praise ye the Lord.”[v]

Indeed , when I think on the grandeur and importance of the subjects to which our attention is solemnly invited this day, I feel deeply impressed with a sense of my own insufficiency to do them justice, and am ready to shrink from the task. In humble dependence, however, on that Almighty Father, whose goodness we celebrate, and who, through the blessed Redeemer of men, is ever most ready to “give his Holy Spirit to them that ask him”—I shall attempt to give, in conformity to the spirit and meaning of the text, and in compliance with the Proclamation—

A SUMMARY VIEW OF THE PRESENT SITUATION OF OTHER NATIONS OF THE WORLD, IN CONTRAST WITH OUR OWN.

In the prosecution of this plan it will naturally fall in my way to take notice of the special blessings enumerated in the Proclamation.—The discourse will be closed with some practical inferences and observations.—The plan proposed, you must be sensible, can be executed only in a concise and comprehensive manner, in a single discourse.

In comparing our situation, in a national view, with that of others, it is hard for us to divest our minds of partialities and prejudices—and to place ourselves in their circumstances—which ought as far as possible to be done, in order to avoid the charge of partiality and unfairness. In many cases, which occur in a minute comparison between nations, it is difficult to determine on which side the balance of advantage lies. There are, however, certain prominent features in the existing state of the nations of the earth, and in their political, religious, moral, literary and social character, which strongly mark their difference, and from a comparison of which, we may, without arrogance, or presumption, decide to whose lot most probably falls the greatest share of happiness. These only will be the subjects of comparison.

To proceed with some degree of method, we will, in the first place, take a summary review of the existing state of several other nations, and briefly of the World in general:–and, secondly, attempt a description of our own. The result, we anticipate, will be such as to “afford us much matter of consolation, satisfaction,” and gratitude to God, and for the exercise of tender sympathy and benevolence towards the afflicted and oppressed of other nations of the world.

We begin with the Republick of France. This mighty nation has burst the chains of civil and ecclesiastical tyranny. They have arisen from the darkness of slavery to the light of freedom. With boldness and energy which astonishes and interests the world, they have espoused the cause of Liberty, which is the birth-right of mankind. With wonderful speed and success, they have vanquished, on every side, the numerous hosts of enemies, which rose up against them.—Lately, a dangerous combination of sanguinary men[vi] has been checked, if not wholly suppressed, which has happily paved the way for the adoption of moderate and rational measures; from the prevalence of which, there is a pleasing hope, (we pray it may not prove delusive) that there will be a speedy termination of the spirit of Vandalism[vii]—of internal rebellions[viii]–of pernicious and destructive jealousies—of barbarous and shocking executions of the innocent.[ix]

Notwithstanding these favourable and pleasing circumstances, and the prospect of an advantageous peace with some of the combined powers, the existing state of things, in this great Republick, is very unpleasant. Their enemies, though defeated, are not conquered; they still exist, and are formidable. Jealousies and party-spirit, though much abated, yet disturb the harmony of the nation, and require to be watched with a vigilant eye. Their government is unsettled, and revolutionary. When the external pressure, which now binds them together, shall be taken off by a general peace, and the numerous armies of the republick[x] shall return into its bosom, if we may judge from our own revolution, the nation will divide into parties, from local interests and prejudices; and it will probably take years to form and establish a government which shall unite all interests, and met the views of all parties; though, I firmly believe, that they will finally overcome all intervening obstacles, and obtain such a government. The Christian Religion, and its sacred institutions, are spurned at, and rejected.[xi] Scarcity6 threatens them. Their manufactures are in ruins.[xii] An enormously expensive war is loading the nation with a debt, which, added to their former one,[xiii] must, hereafter, in all probability, injuriously affect, in various ways, the liberties, the morals, and happiness of the people. Besides, the mischief which a state of war ever operates in regard to religion, learning, and arts,[xiv] morals and domestick happiness is incalculably great. How calamitous then must be the present condition of the French nation in these respects?—I forbear any details on these points. A recurrence to our own situation, at the height of our revolution was, allowing for the difference of numbers, and the difference of religious and political state between the two nations, will give us a faint idea of the present state of our allies. While we felicitate ourselves in a freedom from the various calamities which afflict this magnanimous nations, we cannot but feel deeply interested in their happiness, and wish for their success, in all virtuous measures, to advance a cause dear to mankind, and in defence of which we formerly experienced their generous aid.[xv]

Here let us pause a moment, to pay a just tribute of gratitude and sympathy to that generous, but unfortunate Patriot, whose disinterested zeal and services[xvi] in the cause of Liberty, both in America and France, have embalmed his memory in the heart of every grateful American.—Yes, La Fayette, could our ardent prayers have rescued thee from thy prison and thy chains, and have wafted thee to this country of freedom and happiness, long since wouldst thou have been welcomed to her friendly bosom. We devoutly implore the God of compassion to mitigate and to shorten the period of thy sufferings; and to “cause thee yet to see good days, according to the days in which thou hast seen evil!” May you live to enjoy, in your own country, the fair harvest of that liberty, the seeds of which were planted, and for a season cherished, by your own hand!

We turn next our attention to Great-Britain. The following picture of the present state of this Kingdom is drawn to our hand. “If ever a period called for the exertions of a people in their own defence, the present is the one. The crisis is awful and unprecedented. Our situation is new, and to new measures must we have recourse. Antiquity leaves us without like or rule, whereby to guide our conduct. To ourselves, and on ourselves only, must we look, and depend. At this alarming, eventful moment, when a political system, bold and fascinating in principle, destructive of all existing governments, is adopted and supported by thirty millions of people, established by will and force, in the most fertile regions of the earth, and is daily gaining, throughout Europe, myriads of votaries, what measures are left for us to follow? How are we to act? And what are we to do?—Plans are adopted without prudence, and executed without resolution and success. The millions slain in the fields of Belgium—the populous cities of Great-Britain and Ireland, thinned of their inhabitants—the loom still and neglected—the industrious youth of the provinces dragged from the plough, and shipped off by hundreds, to oppose, in a strange and hostile country, the enthusiastic movements of an armed nation—their bleeding wounds—their agonizing cries, argue forcibly against the measures of the present administration.

“The fall of kingdom, like that of the mountain-flood, comes when we least expect it. Britons! Beware—behold the dangers which surround you, and tremble for the consequences. Involved in a ruinous war—your armies flying before a victorious enemy—unassisted and betrayed by those who call themselves your allies—the publick money prodigally lavished on Sardinian mercenaries in British pay—the satellites of Prussia, supported by your revenues, in the prosecution of war[xvii] whose object is the destruction of millions—the slavery of a Nation—The blood of Kosciusko, cries against us. Add to this, a ruined commerce at home—our manufactures annihilated—Gazettes swelled with bankruptcies—a total loss of credit—a want of confidence in every department of State; and, finally, an unprincipled ministry, who drive the nation down the strong tide of power, the floating wreck of their own avarice and ambition. Such, Britons! Is the picture of your present state.” He adds,

“Our state to-day, is more desperate than it was yesterday. The arrival of each mail announces the loss of battles—the capture of towns. Behold Holland a prey to the victorious enemy! Her military stores, her bank—her navy, are the prize of conquest. Maestricht has capitulated—Nimeguen receives their troops—Where is our army? What corner is to receive them?—Even now the enemy dispute with us the empire of the seas. Should the navy of Holland be thrown into the hostile scale, what would be the consequence?—I walk over deceitful embers—The subject will not bear discussion.”[xviii]

The colouring of this melancholy picture is high; but do not accounts from this quarter, confirm the truth of a great part of the facts here stated?—We may add, as further indicative of the distress of this nation—their persecutions for political opinions, to which Muir, Palmer, Margarot, and others, have fallen victims—the pernicious and distressing effects of the Test Act, which has driven thousands of valuable citizens from the kingdom—and their oppressive taxes, which are rendered necessary, in consequence of an enormous and increasing debt, and an unpopular, destructive, and iniquitous war; and doubly discouraging, because there is no hope of their decrease or termination.[xix] Far be it from us to exult in thus depicting the misfortunes and distress of this nation, hostile as their government has been to our interests and happiness. While we are thankful to God, for our own prosperous and happy state, we sincerely deplore the miseries in which they are involved—and deprecate the greater ones, which apparently threaten them. While as Republicans we finally assert and maintain our rights; as Christians let us forgive the wrongs we have unjustly suffered.

From Great-Britain, let us turn our attention to Spain. View her armies flying before a victorious enemy, and leaving their thousands slain and wounded, with immense spoils behind them. In addition to the horrors and calamities of a fierce, bloody and unsuccessful war, which I leave to your own imaginations to paint, contemplate the political—the religious—the moral, and the literary state of this kingdom. And when you are informed that the government is despotick—the monarch absolute, and the religion papal, you will easily infer what is their situation in respect to politicks and religion, literature and morals.

From Spain, proceed to the Seventeen Provinces, called the Netherlands.[xx] What language can describe the scenes of carnage, ruin and distress which have been exhibited for several years past, in this fertile and populous part of the world? These unfortunate Provinces have been the seat of the present war; in the course of which, some of them have repeatedly changed masters. Their plains have been enriched with millions of human corpses, unhappy victims in the cause either of liberty or despotism, who have perished by the sword, pestilence, fatigue, terror and famine. And what I their present situation? Some of them are annexed to the French Republick, and are represented in the National Convention. Their state, however, which must be considered as revolutionary, is far from being tranquil or secure. The next campaign may recover them, voluntarily or involuntarily, to their former condition, and they may again become a circle of the German Empire. Holland, which includes the greater part of the other Provinces, lies at the mercy of a victorious army, lodged in the heart of their country, and dictating their own terms of peace or submission.

Would you behold a country in still deeper distress?—turn your eyes to Poland. For more than twenty years past, this ill-fated nation has been the sport of her unprincipled neighbours, the Empress of Russia, the Emperor of Germany, and the King of Prussia. In 1772, these formidable powers entered into a most wicked alliance to divide and dismember the kingdom of Poland. This they easily effected, in direct isolation of the most solemn treaties, and in a manner tyrannical and cruel beyond all former precedent. The time will not admit of entering into any details on this most affecting subject. I cannot help observing, however, that the other European powers, beheld these iniquitous transactions, by which a great kingdom, of FOURTEEN MILLIONS of souls, was violently and surreptitiously deprived of a great part of its territory, and a third part of its inhabitants, with an inhuman indifference and unconcern.

The baneful effects of these proceedings were severely felt, till the memorable and happy Revolution in 1791.[xxi] By this revolution, effected without blood shed or even tumult among the people, and in its principles highly favourable to their rights and liberties, Poland had a fair prospect of enjoying some repose after her calamities, and of becoming powerful, prosperous and independent. But, alas! short were her triumphs, and delusive her prospects. Her ambitious, rapacious and but too powerful neigbours, envious at her tranquility, and jealous of her increasing strength, under a free and equal government, and of the spread of the principles of freedom, have, in the same inhuman manner as before[xxii] (in 1772) combined against her, and have replunged her still deeper in the abyss of misery. Noble, vigorous, and worthy of their good cause, have been the struggles of this great nation, under the auspices of kings,[xxiii] and the immediate are command of a brave and admired General,[xxiv] against the most brutal tyranny: But the arm of despotism, after a dubious contest, has proved too mighty for them, and reduced them, we have too much reason to fear, to unconditional submission. What carnage, what horrors have marked the routes of the victorious liberticides, the slaves of the tyraness of Russia?[xxv] The miseries of the Polish nation, judging from the latest accounts from that quarter, are, at this time, great and deplorable beyond description. Unfortunate, afflicted brethren in the bonds of freedom, we weep with you!—Thy wounds, Kosciusko, are thy glory—Thy blood will accelerate the growth of “the tree of Liberty”—Thy fate interests the feelings of the friends of liberty through Europe and America—Thy rich reward is their esteem and admiration. May it comfort thee in thy prison!—

We rejoice that a righteous God reigns, who will one day avenge the cause of the innocent and oppressed, and will so over-rule the dark dispensations of his Providence, as to bring great glory to his own name, and happiness to the whole family of mankind.

The little Republick of Geneva,[xxvi] next claims our attention. Only four years ago, this people were as happy and as flourishing in their government, commerce, manufactures, religion and morals, as any people on earth.—Now, through a pernicious, disorganizing foreign influence—an influence which has since threatened us with the same calamities, they are reduced to the most humiliating and afflicting state of anarchy and distress. “Geneva,” says the intelligent historian of this Revolution, “is lost, without resource, in respect to religion, to morals, to the sciences—to the fine arts, to trade, to liberty, and above all, to internal peace. Its convulsions have no other term than those of France, to the fate of which, it has had the criminal imprudence irremissibly to attach itself, and the various shocks of which, it must more or less, inevitably suffer.”[xxvii]

The nations we have mentioned, with their dependent colonies in the West-Indies, whose wretchedness equals that of any country we have described—embrace that portion of mankind, which, so far as we know, are, at the present time, involved in the most afflicting and deplorable misery. All the other nations of Europe, are more or less affected by the present convulsed state of things in this quarter of the world.

The unwieldy Germanick Empire, without power to execute its will[xxviii]–without finances—involved in a destructive and unpopular war—is divided against itself, and is probably tottering into ruin.

The enslaved subjects of the two most insidious, unfeeling, and (shall I say amiss, if I add) monstrous tyrants perhaps, on earth, I mean the Empress of Russia, and the King of Prussia—the slaves of these cruel despots, who are employed in butchering their fellow-men by thousands, cannot, generally speaking, be otherwise than wretched. Till the period arrives, and I believe it to be fast approaching, when a sufficient degree of knowledge of their rights, shall be disseminated among the lower orders of people, as to enable them to effect a revolution, and to break the chains which bind them, it must, I think, be considered rather as their felicity, than their misfortune, that they are ignorant and insensible of the evils which it is their lot to endure.

The neutral nations of Europe, which are few in number, and even when combined, of small weight in the political scale, subjected, as they are, to constant irritations and alarms from their more powerful neighbours, must be in a state of painful solicitude, lest they should be drawn into the whirlpool, which disturbs the peace, and threatens the overthrow of so many of the powers around them.

From Europe we pass into Asia. Of this immense quarter of the Globe, containing, it is conjectured, more than half mankind[xxix]–our knowledge is very imperfect. Judging, however, from the best accounts that have come to our knowledge, their state, in a political, religious, moral and social view, is far from being either enviable or eligible. This vast country is divided between the despotick Empires of China, Russia, the Great Mogul, Persia, and Turkey; except what is inhabited by the wild and wandering Arabs and Tartars, who are said to be the only people in Asia “that enjoy any share of liberty,” if what they possess may be honoured with the name. In regard to religion, the greater part of the inhabitants are Pagans and Idolaters; the rest are Mahometans, Jews, and a few Christians. From the nature of their government and religion, we are left to infer their political, moral and social state. “The system of morals, in this country,” says a celebrated historian, speaking of Asia in general, “is no less extraordinary than that of nature. When we fix our eyes on this vast continent, where nature hath exerted her utmost efforts for the happiness of man, we cannot but regret that man hath done all in his power to oppose her. The rage of conquest, and what is a no less destructive evil, the greediness of traders, have in their turns, ravaged and oppressed the finest country on the face of the globe.”[xxx]

Of the various nations in Asia, the Chinese are generally believed to be the best governed, the most civilized and the happiest.—Their panegyrists have said, extravagantly enough, that “the history of this well-governed Empire, is the history of mankind; and the rest of the world resembles the chaos of matter, before it was wrought into form.”[xxxi] And what is the state of this happiest of people?—China, beyond doubt, is the most populous spot on the globe—of course, judging from the experience of all ages, the people must be the most corrupt in their morals; and for the same reasons that our populous towns are more depraved in this respect, than the country.—What opinion should we form of the character, laws and manners of that people, among whom we should see, “not unfrequently, one province rushing upon another, and putting all the inhabitants to death, without mercy, and with impunity?” Whose laws neither “restrain nor punish the exposure or the murder of new-born infants?”—Whose “Sovereign is the cudgel?”—Among whom “the innocent man is often, by infamous magistrates, condemned, whipped and thrown into prison; and the guilty pardoned upon the payment of a pecuniary fine; or punished, if the offended person happen to be the most powerful?”[xxxii]—And where “one half the inhabitants are employed in cheating and over-reaching the other?”[xxxiii]—And such, it is affirmed, by respectable historians, are the character, laws and manners of the Chinese, who are the wisest and most civilized people in Asia.

In India, though we find much to admire in their code of laws, we find much also to deplore—many indications of barbarism and wretchedness—Some of their laws are infamous, inhuman, cruel and glaringly unequal and unjust.[xxxiv] The condition of the lower classes of people is wretched and horrible in every respect—The Pouliats, or the fifth cast, the refuse of all the rest, are employed in the meanest offices of society, and live upon the flesh of animals that die natural deaths—They are forbid to enter the temples—the publick markets, and even the streets where the Bramins reside—They can neither possess nor lease lands—and may be put to death with impunity, if they chance to touch any one that does not belong to their tribe.

Degraded and contemptible as these Pouliats are, it is said “they have expelled from among themselves the Pouliches, still more degraded. These last are forbidden the use of fire—they are not permitted to build huts, but are reduced to the necessity of living in a kind of nest, which they make for themselves in the forests, and upon the trees. When pressed with hunger, they howl like wild beasts, to excite the compassion of the passengers. The most charitable among the Indians, then deposit some rice or other food at the foot of a tree, and retire with all possible haste, to give the famished wretch an opportunity of taking it without meeting his benefactor, who would think himself polluted by coming near him.”[xxxv]—This is the dark side of the picture of the present condition of this numerous people—but contrasted with the darkest shades in our own, the difference is great and striking, and is calculated to excite the warmest effusions of gratitude to Him “who hath made us to differ.”

The time would fail me to give even a cursory view of the state of the other nations of Asia.—To relieve your patience, which I fear is already fatigued, I shall traverse with rapidity, the other parts of the globe.

Of Africa, inhabited, according to common computation, by 150 millions of people, we know still less than of Asia, and but little more of South America; and least of all of the wild inhabitants of those extensive regions which lie West and North of the United States and Canada. From the little we do know of them, however, it will not be presuming too much to give it as our opinion, that the most enlightened, the best governed, and he happiest among the numerous nations in these quarters of the globe, fall far below these United States—I will not say in their morals—for in this point, a comparison with some other nations, I fear, would be against us—but in their constitutions of government—in their laws—in science—in their knowledge of useful arts—in a word, in their religious, civil and social privileges.

After taking this general view of the nations of the earth, (in doing which I have taken up more time than I intended, though far less than it required, to do it full justice)—we are prepared to revisit our own country—and to survey the blessings which distinguish it from the rest of the world.—These have been so often enumerated on occasions like the present, that little that is new, will be expected, and brevity, of course, will be acceptable.

- Our lot is distinguished from that of many other nations, by the blessings of Peace. We have seen how great a portion of the world is afflicted with the awful calamities of War. In consequence of our intimate connexion with some of the belligerent powers, by means of the iniquitous commercial depredations of one, and a fascinating and dangerous influence of another, the peace of our neutral nation has been imminently endangered. By means of the latter, the poisonous seeds of a party, disorganizing spirit were sown thick among us—and being nourished by the former, sprung up and increased, for a short time, with alarming rapidity; and threatened us with all the calamities, first of a foreign, then of an intestine war.—The fruits of these seeds have been more or less visible in all parts of our country, but none have been so matured and conspicuous as the Western insurrection.—The wise, decisive and seasonable measures adopted by the Supreme Executive, and the other officers of government, and advocated and supported by the great body of enlightened citizens, to check and counteract this dangerous foreign influence in all its shapes—have, under the smiles of Province, procured our exemption hitherto from foreign war—and by means of a late happily concluded foreign negociation,[xxxvi]–and the increasing harmony and union between this country and the French nation, in consequence of the recent happy change in the measures of their government—we have the most pleasing “prospect of a continuance of this exemption.”

A blessing no less distinguishing than our exemption from foreign war, is the preservation of our internal tranquility, when “wantonly threatened” by a daring insurrection. The alacrity with which our fellow-citizens, when called, flew to the standard of their Chief, on the trying emergency, when the important question was to be decided, Whether we should be governed by a mob, or by our legal representatives?—the ease and celerity with which a most respectable and formidable army was collected—the zeal and patriotism which animated them—the complete success with which their exertions were crowned—and the general applause they received from their grateful fellow-citizens—all these circumstances serve to confirm our internal tranquility, as they operate to discourage ambitious and unprincipled demagogues from making the like attempts to interrupt our peace in future—and to increase the confidence of the people in the stability, energy and promptness of our Federal Government.

When we turn our eyes to the little Republick of Geneva, and behold her deep distress—and trace the causes which led to it—we cannot but feel the most undissembled gratitude to God, our kind Preserver, in that we have so happily escaped the very same snares, which have involved her in ruin.

In speaking of our domestic peace, we ought not to pass unnoticed, the state of our frontiers. For several years past we have been engaged in an unhappy contest with the Indian nations. Since we have been able satisfactorily to trace the origin of this expensive war—and know that the unfortunate tries who have been engaged in it, have been deceived, urged on, and assisted by a foreign nation, whose measures have been peculiarly hostile to our prosperity and peace; and no less so, we believe, to the happiness and true interests of the Indians themselves—the necessity and justice of the vigorous measures of our government in prosecuting it, can hardly be doubted by any one. The signal success, therefore, of our frontier army[xxxvii] the last year, must be considered a favour of Divine Providence. In consequence of this success, and the pacific treaties and measures entered into and pursuing by our government, and the change of plans in the British government, the aspect of affairs in our western borders, though still unsettled, wear a more favourable and pacific aspect.

- Our lot as a nation is distinguished from that of the other nations of the world, by “the possession of constitutions of government which unite—and by their union establish liberty with order.” The principles of our Federal and State constitutions are the same; and have for their object the protection and safety of the lives, the liberties and fortunes of the citizens.—The state governments are protected against an undue interference of the Federal Government—each is left to make and to execute its own local laws—while the Federal Government corrects and harmonizes the jarring interests of the state governments, and cements their union. Our constitutions of government indeed are the fruit of the experience of all former ages, and the trial of them has proved their singular excellency. In no nation on earth do the citizens enjoy protection and safety in their rights, at the expense of so small a portion of their natural liberty—Each individual is secured in the possession of his own rights, but in no instance suffered to encroach upon the rights of others.

- The wise and salutary laws, which flow from, and correspond with, our free constitutions of government—the freedom and the frequency of our elections—the patronage and encouragement given to publick and school education, and to all useful mechanic arts and improvements-the perfect enjoyment of religious as well as civil liberty—the means afforded, and the measures contemplated to extinguish our national debt[xxxviii]–and in general “the unexampled prosperity of all classes of our citizens;”—these are signal blessings, which, if they do not distinguish our lot from every other nation, they do from most of them—and certainly “mark our situation with peculiar indications of the divine beneficence towards us.”

“When,” therefore, “we review the calamities which afflict so many other nations”—when we survey and consider the state of the whole World, so far as our knowledge extends—does not “the present condition of the United States” indeed afford much matter of consolation and satisfaction?”—“In such a state of things, is it not, in an especial manner, our duty as a people, with devout reverence and affectionate gratitude, to acknowledge our many and great obligations to Almighty God?” “What nation is there so great, that hath statutes and judgments so righteous as all this law which I set before you this day?”—“How great is the sum” of our mercies?—What shall we render to the Lord for all his benefits?”

If our situation, my brethren, be such as we have represented—if the Governour of the Universe has thus distinguished us with his favours—then, surely, we ought to be the best people in the world. “To whom much is given, of them much is required.” Our gratitude should bear a proportion to our blessings—Our love to God, and our obedience to his perfect laws, it will be reasonably expected, should as much surpass the love and obedience of others, in point of fervor, constancy, and purity, as our advantages and mercies exceed theirs—And thus to estimate and improve our mercies is the only way to secure their continuance.—Our national and individual sins, under our advantages, will be attended with peculiar aggravations—Let this consideration operate as a powerful dissuasive from sins of every kind—and excite us to an upright conduct, as men, as citizens, and as Christians.

In our present situation, loaded and distinguished as we are, by various blessings—we have need to beware that our hearts be not lifted up with pride and self-conceit, as though we were the peculiar favourites of heaven, and the most deserving of all the nations of the earth. From such arrogance in our prosperity, may the Lord preserve us!—It is the nature of prosperity to fill the mind with vain glory, self-importance, and self-complacency—to make men feel independent of their fellow-men, and even of their God.—To keep our minds properly balanced and humble, when things go well with us as a nation, or as individuals, we should constantly bear in mind, that it is not we ourselves, but the Lord our God, that maketh us rich, and causeth us to be prosperous and happy.—Besides, prosperity in this world does not always mark the best nations or the best men. Moses declares to the Israelites, that it was not for their righteousness, or the uprightness of their heart, that Canaan was given to them, but because of the wickedness of the nations who inhabited it, and to fulfill a promise to their fathers—“Understand therefore, said he, that the Lord thy God giveth thee not this good land to possess it for thy righteousness, for thou art a stiff-necked people.”[xxxix]—Let the consideration that this same language, can with truth be addressed to us, serve to humble us in the midst of our joy—and to qualify our rejoicing with a due proportion of trembling for our unworthiness.

Blest with a free and efficient government, a flourishing commerce, good credit, a fine and but partially settled country, and at peace with all the world—the United States offer, if not the only, probably the best asylum for the oppressed and persecuted by civil and ecclesiastical tyranny—Hither thousands of useful artisans and others, have already taken refuge from the calamities which afflicted their own country—By a strict adherence to the government, laws, and religious institutions of our country—may we evince to the world around us, their superior excellency, and cause them to say of us—“Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.” Thus may we “render this country more and more a safe and propitious asylum for the unfortunate of other countries.”

Let us take heed, and keep our souls diligently, lest we forget the great things which God hath done for us, and the impression of our obligations to him for them, be effaced from our hearts. Let us cherish their memory by teaching them to our children—that they may know and learn to estimate the immense value of the blessings which are, we hope, to be their future inheritance.

If the great body of the citizens throughout these American States, are well informed in respect to their rights and liberties, it will be difficult, if not impossible for ambitious, designing men, to wrest them from them. If ever Americans are enslaved, the sad revolution will be preceded by a prevalence of ignorance among the middling and poorer classes of men. As, then, we value the blessings of a free and equal government for ourselves, and our posterity—let us use our influence separately, and jointly, “to extend true and useful knowledge,” among very class of people—and “to diffuse and establish,” in our own families respectively, and among the youth in general, “habits of sobriety, order, morality and piety.”—We cannot leave a better legacy to our country than a family of well educated children.

As God hath made of one blood all nations to dwell on the face of the earth—they are all brethren of the same great family. It is the part of a good man to possess the feelings of a brother towards the whole human race—and to be concerned for their happiness.—It becomes us, therefore, not to confine our benevolent regards to the narrow circle of our particular friends, to our town, our state, or even to our country; but to feel a glow of affectionate good will for all men of every nation, religion and character, on earth; and to unite in one sincere and fervent petition to the Great Ruler of Nations, “THAT HE WOULD IMPART ALL THE BLESSINGS WE POSSESS, OR ASK FOR OURSELVES, TO THE WHOLE FAMILY OF MANKIND.”

To conclude—What people, in any age or country, ever had greater reasons for gratitude and joy, either from the real enjoyment, or the prospect, of great and good things, than the inhabitants of the United American States, at the present moment?—We have a healthful, extensive, and fruitful country, equal to the support of the largest Empire that ever existed on earth—We have Constitutions of Government confessedly as good, as any ever formed by man, and as well administered—and with as fair prospects of permanency—The civil blessings which flow from good government, we feel in all their variety, and to a degree probably beyond any other nation—We have a Religion, and a free enjoyment of it—against which the gates of hell shall never prevail—whose institutions and precepts are wisely calculated to promote peace on earth and good-will among men—which unfolds to us the wonderful plan of Redemption by Jesus Christ, and brings life and immortality to light—With such a COUNTRY—such a GOVERNMENT—and such a RELIGION—if we are but wise to improve the advantages they furnish, and God vouchsafes to us his blessing—what that is great and ennobling to human nature, may we not expect?—“The wide, the unbounded prospect lies before us”—“Here let” us “hold”—and while the impression is warm on our hearts, let us with one consent, offer up a cloud of grateful incense, through Christ, to the Father of Mercies—unbounded in his love, and infinite in goodness—to whom be glory forever,

A M E N.

[i] Deut. i. 3.

[ii] Deut. xxxiv. 7.

[iii] President Washington entered his 64th year, Feb. 22, 1795—being born Feb. 11, (O. S.) 1732.

[iv] Deut. xxxiii. 29.

[v] Psalm cxlvii. 20.

[vi] The Jacobins are here alluded to. That they deserve to be called sanguinary men, will appear from the following extracts:–“A deputation from the section of the Champs Elysees, presented an Address, on the 23d of November, felicitating the Convention on the decree against the remnant of the Dictator’s (Robespierre’s) faction, sitting at the Jacobins, and against those individuals, who, like the old privileged Orders, retained only the name of their predecessors, without one of their virtues—and exhorting the Representatives of the people to crush those venomous reptiles, who were swollen into notice only by the innocent blood with which they had gorged themselves.”

To this address, Glauzel, the President, replied, “The National Convention has declared unextinguishable war against all the factions, all the intriguers, all the advocates of terror, all the depredators of the publick fortune, and all the enemies of the people, whatever mask they may assume. The reign of virtue and justice is arrived: it is on these bases that the national representation will found the Republick, which is to render the French happy. While Capet existed, the Jacobins saved the publick weal by their energy; their hall was then the residence of virtue; they hastened the destruction of the tyrant. But in overturning the throne, the Convention had sworn to annihilate tyranny. Since the 27th of July, the society of the Jacobins had attempted to rival the national representation; it had become the resort of the factious—of the agitators—it was therefore the duty of the representatives of a free people, true to their oath, to shut up a place polluted by guilt.” The Herald, Vol. I. No. 73.

In answer to a similar address, from the Popular Society of Chartres, congratulating the Convention on the decree for shutting up the Jacobin Club—the President said—“The majesty of the people, like a wave which drowns vile reptiles, has dispersed its enemies. The Convention knows how to repress all those who take the names of lions, leopards, and tigers. They will have only men.” Centinel, Vol. XXII. No. 45.

[vii] See Gregoire’s celebrated Report on the destruction wrought by Vandalism, and on the means of repressing it—made August 31, 1794, in the Convention of France. The Vandals (whence the expressive term Vandalism) were one of those barbarous nations, inhabiting the inhospitable regions of the North, who, like a torrent, overwhelmed the Roman empire, making havock of books, elegant temples, statues, pictures, and all the rich and superb monuments of learning and the arts. It appears from the report referred to above, that the same destructive, barbarous scene was acted over again in France, during the tyranny of Robespierre. “Do not think it exaggeration,” says Gregoire, “when you are told, that the names only of the articles purloined, destroyed, or wasted, would form many volumes.”—To such lengths did they proceed in their havock of literature and the arts, as to propose that “all who cherish the arts should be destroyed”—that “all rare animals should be killed, that the citizens might not spend their time at the museum, in viewing natural history”—that “the national library should be burnt”—that the words, “men of science” and “aristocrats,” should be considered “as synonymous.” Dumas said “it was necessary to guillotine all men of genius and wit.”—And this cry was attempted to be raised in the sections, “guard against that man, for he has made a book.”

[viii] A decree of amnesty passed the National Convention, Dec. 2, 1794, declaring that “All persons in the precinct of the armies of the West, and of the Northern coast, now under the denomination of Rebels of la Vende and Chouans, who shall lay down their arms, within the next month from the publication of this decree, shall not afterwards be prosecuted, on account of their revolt.”

Gen. Duterre announced, as effects of the above decree, “that the system of justice and humanity, adopted in La Vendee, promised a speedy end to the war in that quarter, and that the rebels were daily surrendering, saying, Since you have pulled down the scaffolds, we abjure fighting against our brothers.

“La Vendee,” says Dubois Crance, “now produces 500,000 oxen and mules less than before the Revolution; and a million acres of land, formerly cultivated, now lies waste.” Such have been the destructive effects of their rebellion.

[ix] The following extracts are here introduced in justification of the phrase—barbarous and shocking executions of the innocent—and to shew the great impropriety and absurdity of approving and justifying, in universal and undistinguishing terms, the conduct of part of the French nation—conduct, at the recital of which (to use their own emphatical language) “Nature shudders—reason is confounded—and liberty covers herself with the mantle of mourning.”

In the “Bill of accusation, drawn up against fourteen members of the revolutionary committee of Nantes, confined at Paris, and exhibited to them by the Publick Accuser, Lebois, Oct. 19”—it is declared, that

“Whatever is most barbarous in cruelty—whatever is most persidious in guilt—whatever is most dreadful in extortion—and whatever is most shocking in depravity, compose the accusation of the members and commissioners of the revolutionary committee of Nantes.

“In the most remote records of the world, in all the pages of history, even of the barbarous ages, scarcely would be found, any traits which come near to the horrors committed by the accused. Nero was less sanguinary, Phalaris less barbarous, and Syphanes less cruel!”

To verify his charge, he states, among other things—that “On the 15th Frimaire, 132 new victims were devoted to death. Order was given to shoot them; and it was Goulain, Grandmaison and Mainguet, who signed this order, which still exists in its original form.

“On the night between the 24th and 25th Frimaire, 129 prisoners, taken at hazard, and torn from the prisons, bound, pinioned, dragged to the harbor, embarked in a boat, and plunged into the river. Goulain held the fatal list, Foly bound he unhappy victims, and Grandmaison threw them headlong into the Loire. The project was decreed in the Committee, and the orders given by the members. Mainguet allows that he signed them;–Grandmaison acknowledges that he caused the victims to be thrown into the river; and Goulain presided at this dreadful execution, which confounded at once the guilty and the innocent, which destroyed all the sacred rights of nature, violated those of liberty, and darkened the fairest days of her reign with a cloud of blood.

“Never will the hand of time efface the impression of the enormities committed by these atrocious men. The Loire will always flow with blood-stained waters, and the foreign mariner will not arrive without trembling on the coasts covered with the carcases of victims sacrificed by barbarity, and which the indignant waves will have disgorged on those shores.

“Drunk with blood and wine, these cannibals scarcely knew their victims, and their eyes refused to read the traces of their crimes.

“In order to accomplish these crimes, it was necessary to associate with themselves persons of the most depraved principles: They form a revolutionary company: They choose accomplices of the most atrocious character; and Goulain was not ashamed to ask—If villains still more depraved were to be found?” The Herald, Vol. I. No. 77.

Extracts from the Trial of Carrier.

“Petit, substitute of the Publick Accuser, read a list of 42 persons drowned in Bourg Neuf, of whom one was an old man of 79 years, twelve women, twelve girls, and fifteen children, five of whom were at the breast, and others from five to six years old—by Carrier’s orders.

“Mergault declared, that two volunteers, who lodged at his house at Nantes, used to go out with their arms, and every day shoot a hundred of the insurgent prisoners, who were confined in a large enclosure. The volunteers told him, that it was by Carrier’s orders.

“The Chief Judge asked Carrier, if he recollected the child of 13 years old, whom he condemned, and who said to the executioner, “You will hurt me very much.”—The guillotine cut his head in the middle. Or if he recollected the death of the publick Executioner at Nantes, who died with horror, after having executed (without trial) the five sisters by the name of Metairie, the eldest 28, the youngest 17 years old—together with their maid, of 22.” Centinel.

We are happy to add, that justice has triumphed over these monsters—that the reign of terror has ceased in a great measure—that a spirit of humanity and moderation is prevailing, and “the national character” of the French, “is re-appearing.”

[x] Reported to amount to 1,200,000 men.

[xi] The rejection of the Christian Religion in France is less to be wondered at, when we consider, in how unamiable and disgusting a point of view it has been there exhibited, under the hierarchy of Rome. When peace and a free government shall be established, and the people have liberty and leisure to examine for themselves, we anticipate, by means of the effusions of the Holy Spirit, a glorious revival and prevalence of pure, unadulterated Christianity.—May the happy time speedily come!

[xii] The following facts, illustrative of this assertion, were lately stated to the Convention by Dubois Crance.—“Silk stuffs, to the value of two hundred millions of livres, were formerly manufactured at Lyons from the raw material of the value of twelve millions. This manufacture of silk was totally ruined by the severe decrees against Lyons, under the Jacobin administration. Great part of the wealthy merchants and manufacturers, were proscribed or guillotined, and their property seized. The number of victims sacrificed in that city alone, was upwards 4500. The silk weavers were driven from their occupations, and compelled to collect their sustenance from the ruins of the houses of the rich, a great part of which were destroyed, by order of the Club government. Ten thousand of the workmen in the fine cloth manufactures of Sedan, are nearly destitute of employment.” It is with satisfaction we add—that since the fall of the Jacobin faction, three thousand merchants, manufacturers and artisans, have returned to France, through Switzerland, and resumed their labours.”—Should moderation continue to prevail, others, no doubt, will follow, and the state of manufactures will assume a more pleasing aspect. The Herald, Vol. I. No. 68.

[xiii] The state of the nation, in respect to their finances, may be judged of by the following:–The expenditure, according to Mr. Neclaer, exceeded the revenue, in 1789, 56,239,000 livres, equal to L.2,343,291 sterling.

[xiv] See Note on Vandalism, p. 11.

[xv] The following are the Author’s sentiments respecting the French Revolution, expressed in a sermon delivered on the day of Publick Thanksgiving, Nov. 20, 1794, and here inserted by desire.

“Liberty is the birth-right of all mankind; but few of them, comparatively, enjoy it. It has been wrested from them by the various artifices of wicked and designing men, and kept concealed from their view. They have been held in various kinds and degrees of slavery, and knew not that they had a right to be free. But the scales of ignorance are fast dropping from their eyes. Whole nations have risen, determined to maintain their rights. Where that genuine liberty, which is the right of every man, has been their object, and the measures pursued to attain it have been commendable, and such as heaven approves, as lovers of mankind, we cannot but rejoice most sincerely, in their success. This is the bound which I conceive ought to limit our joy and gratitude to Heaven, on account of those nations who are contending for their rights. Their cause is unquestionably good; their errors and irregularities, however, proceeding almost necessarily from the magnitude and the difficulties of their undertaking, are not to be justified, nor yet too severely censured. All circumstances taken into view, they ought, perhaps, in a great measure, to be excused. But for their cruelties, and especially for their impieties, we can find no adequate excuse. It would discredit the best of causes, with every good man, to blend such cruelties and impieties with it, and to make them accessory to, and auxiliaries in, its promotion. While then we offer up our thanks to God, this day, for the progress of real liberty, in opposition to tyranny and oppression, in whatever quarter of the world this progress has been made, let us carefully separate between the precious and the vile, and not rejoice for that which ought to fill our hearts with sorrow and mourning.”

[xvi] The Marquis La Fayette, at the age of 19, espoused, with ardour, the cause of America; and at a very early period of the war, determined to embark for the United States. Before he could effect his departure, intelligence arrived, that the American rebels, reduced to 2000 men, were flying through the Jerseys, before a British force of 30,000 regulars. This news so effectually extinguished the little credit which America had in Europe, in the beginning of the year 1777, that the Commissioners of Congress at Paris, though they had previously encouraged this project of Fayette, could not procure a vessel to forward his intentions. Under these circumstances, they thought it but honest to dissuade him from the present prosecution of his perilous enterprise. It was in vain they acted so candid a part. The flame which America had kindled in his breast, could not be extinguished by her misfortunes. “Hitherto,” said he, “I have only cherished your cause—now I am going to serve it. The lower it I in the opinion of the people, the greater will be the effect of my departure; and since you cannot procure a vessel, I shall purchase and fit out one to carry your dispatches to Congress, and myself to America.” He accordingly embarked, and arrived at Charleston, early in the year 1777. Congress soon conferred on him the rank of Major-General. He accepted the appointment, not however without exacting two conditions, which displayed a noble and generous spirit—the one, that he should serve at his own expense—the other, that he should begin his services as a volunteer. See Amer. Geog. 2d edit. P. 136.

[xvii] Against Poland.

[xviii] The Herald, Vol. 1. No. 71.

This sketch of the present state of Great-Britain, was written and published in England, as late as Nov. 14, 1794, by a writer under the signature of Junius Redivivus. He appears to be no friend to the “political system” of the French—and advocates vigorous measures to oppose the progress of what, in his view, disorganizing principles. We conclude from these and other circumstances, that he was a friend to his country, and would not knowingly exaggerate its calamitous state.

[xix] I take leave here to introduce a comparative view of the National Debts of Great-Britain and the United States, which, with the observations annexed, will shew the present-eligible situation of the latter compared with that of the former, and with that of Europe at large.

DEBT OF GREAT-BRITAIN.

Dols. Cts.

Principal of the English Debt, in 1785, 239,154,880, sterl. or 1062,910,577. 80

Interest and charges for management, 9,275,769, or 41,225,640. —

Chalmers Estimate of the Comparative Strength

of Great Britain, p. 159

Since 1785, the National Debt of Great-Britain is said to have increased to upwards of THREE HUNDRED MILLIONS sterling—the interest of which, together with the civil list, secret service money, &c. &c. require a yearly revenue of upwards of seventeen MILLIONS. See Rev. Mr. Channing’s Thanksgiving Sermon, of Nov. 27, 1794, p. 17.

DEBT OF THE UNITED STATES.

Dols. Cts.

Principal of Domestick Debt at the close of 1794, consisting of unfunded—

Six per cent.—three per cent, and deferred stock, 64,825.538. 70

Total interest, payable annually by the contract existing at the close of the year 1794, 2,405,272. 60

Total Foreign Debt, due to the French Government, and at Amsterdam and

Antwerp, about 14,708,000. —

Interest on foreign loans, as due 31st Dec. 1794, 678,102. 80

Total Debt, principal and interest, 72,616,914. 10

Secretary Hamilton’s Report, of Jan. 7, 1795.

If we reckon the Debt of Great-Britain as it stood in 1785, the difference between that, and ours, is upwards of One thousand and thirty-one millions of dollars. The actual difference, at the present time, is probably a third more. There is this further striking difference, theirs is rapidly increasing—ours is decreasing.

In the United States, the average proportion of his earnings which each citizen pays for the support of the civil, military, and naval establishments, and for the discharge of the interest of the publick debts of his country, is about one dollar and a quarter, equal to two days labour, nearly: that is, five millions of dollars to four millions of people. In Great-Britain, France, Holland, Spain, Portugal, Germany, &c, the taxes for these objects, on an average, amount to about six dollars and a quarter to each person. Hence it appears, that in the United States, we enjoy the blessings of free government and mild laws; of personal liberty and protection of property, for one fifth part of the sum, for each individual, which is paid in Europe for the purchase of publick benefits of the same nature, and too generally without attaining their objects; for less than one fifth indeed, as in European countries, in general, ten days’ labour do not amount to six dollars and a quarter. In this estimate, proper allowances are made for publick debts.

From the best data that can be collected, the taxes in the United States, for county, town, and parish purposes, for the support of schools, the poor, roads, &c. appear to be considerably less than in those countries; and perhaps the objects of them, except in roads, is attained in a more perfect degree. Great precision is not to be expected in these calculations; but we have sufficient documents to prove that we are not far from the truth. The proportion in the United States is well ascertained; and with equal accuracy in France, by Mr. Necker; and in England, Holland, Spain, and other nations in Europe, by him, Zimmermann, and other writers on the subject.

This statement, at the same time that it evinces the eligible and prosperous situation of the United States, shews how large a proportion of their earnings, the people in general can apply to their private purposes. See American Universal Geography, p. 250.

[xx] The Netherlands are divided into two parts—distinguished by Northern and Southern divisions. The Northern contains the Seven United Provinces, usually known by the name of Holland,–2,758,632 inhabitants in 1785. The Southern contains the Austrian and French Netherlands,–1,500,000 inhabitants.

[xxi] Perfected May 3d.

[xxii] The Leyden Gazette of March 4th, 1794, states—that “Baron Ingelstrom, Minister Plenipotentiary, and Commander in Chief of the armies of the Empress of Russia, has transmitted a Note to the permanent Council of Poland, requiring them to collect all the acts and decrees of the Revolutionary Diet of 1791, from all the provinces of Poland, and to put them under seal in the custody of the permanent Council.” He closes this most extraordinary requisition, intended to blot out the annals of their happy Revolution, by saying, “He has no doubt the wisdom of his motives will command a ready reception of this order, and an approbation proportioned to the importance of the object.”

The same Gazette further states, that the Empress is endeavouring to rivet her chains, and to put it forevr out of the power of wretched Poland to throw off the yoke, by gradually reducing the Polish army, and by melting down the cannon which the Revolutionary Diet had procured. The Herald, Vol. 1. No. 4.

On the 16th of April following, Baron Ingelstrom sent another Note to the King and permanent Council, “requiring that the arsenal of Warsaw should be delivered up to him—the Polish military be disarmed, and that 20 persons, mostly of consideration, should be arrested, and if found guilty, punished with death.”

The effect of this singular Note was a violent and bloody insurrection at Warsaw—which opened the dreadful scene of war, since exhibited, and which, after destroying several hundred thousand people, and entailing poverty and wretchedness on as many more, is likely to have a most melancholy termination.

The following is an extract from a Treaty of cession, signed (by constraint) in the name of Poland, in favour of Russia, at Grodno, July 13, 1793—Translated from the Leyden Gazette.

The second article determines “the limits which shall hereafter forever separate the empire of Russia and the kingdom of Poland.” The boundary line described cuts off a large part of Poland, bordering on Russia, inhabited by three millions and a half of people. “This line above determined,” says the treaty, “to serve forever as a boundary between the empire of Russia and the kingdom of Poland—his Majesty, the King, &c. cede in a manner of the most formal, the most solemn and the most obligatory, to her Majesty, the Empress of all the Russias, her heirs and successors, all that which ought in consequence to appertain to the Empire of Russia, and especially all the countries and districts, which the aforesaid line separates from the actual territory of Poland, with all the property, sovereignty and independence; with all the cities, fortresses, boroughs, villages, hamlets, rivers and waters, with all the vassals, subjects and inhabitants; releasing them from their homage and oath of fidelity, which they have taken to his Majesty and the crown of Poland; with all the rights, as well political and civil, as spiritual, and in general, with all that belongs to the sovereignty of those countries; and his said Majesty, the king and the republic of Poland, promises in a manner the most positive and solemn, never to form, either directly or indirectly, or under any pretext whatever, any pretension to the countries and provinces ceded by the present treaty.” The Herald, Vol. 1. No. 17.

[xxiii] Stanislaus Augustus, the present King of Poland, is a most amiable, humane man—and has endeared his name to all lovers of liberty by his exertions for the freedom and happiness of his subjects. His speeches to the Diet, a few days after the forementioned treaty was signed, exhibit forcibly the feelings of a distressed, generous, paternal heart—“My own fate,” said he, “interests me the least; I have more than once offered to sacrifice myself for my country; but it is your fate that agitates my thoughts, and what is more important the fall of the nation—It is the duty of a Father who loves his children, to lay the plain truth before them, without any disguise—of this duty I have acquitted myself.”—In a second speech delivered on the same day, he says-“I have heard, with heart-felt grief, the vows of a virtuous citizen, who, before the last sitting, promised himself tears of compassion from his posterity, who will see upon his tomb, the name of him, who chose rather to die, than cease to call by the name of compatriots, those whom a foreign force has appropriated to itself. [Alluding to the three millions and a half of Poles consigned over to Russia, by treaty.] I dare hope in my turn, that when I shall appear before the great Judge, to whom I appeal for the purity of my motives, those who shall live after me, will say,–“He was unfortunate, but he was not culpable.” See these affecting speeches at large, in the Herald, Vol. 1. No. 16.

[xxiv] Kosciusko. This General was in America during our Revolution, and is well known to many of our officers. Here, as the pupil of Washington, “he was confirmed in the principles of liberty, endured its toils, and learned to” fight “ in its defense.” He was placed by his countrymen, at the head of their armies, and he often led them to victory. At length, overpowered by numbers, and covered with wounds, he was taken prisoner, with a part of his army, and, under a strong guard of 3000 men, conducted to Petersburgh, where our latest accounts leave him.

[xxv] Accounts under the London head of Jan. 3d, 1795, state—that the Russian army under Gen. Suwarow, in the course of 52 days from the 17th of Sept. fought six battles, in which were slain 28,500 Poles.—How dreadful must the carnage appear, when we take into the account the exploits of Fersen, and the rest of the Russian Generals—and of the Prussian army? Mercury, No. 16, Vol. V.

In the engagement on the 4th of Nov. (1794) at Praga, on the banks of the Vistula, 20,000 Poles perished by the sword, the fire and the water. In the suburb of Praga, 12,000 inhabitants of both sexes, and all ages, were the victims of the first fury of the Russians, who massacred all that they met, without distinction of age, sex or quality. Centinel, Vol.XXII. No. 49.

Another account of the capture of Warsaw, by way of Vienna, states—that “the besieged consisted of 40,000 men, amongst whom were 7000 Prussians; and the massacres committed by the Cossacks upon men, women and children, are too horrible for description.

[xxvi] Its inhabitants are estimated at 30,000.

[xxvii] See a brief Account of the Origin and Progress of the Revolution in Geneva—written in letters, by a Genevese gentleman. This well written afflicting narration, is well worth perusal.

[xxviii] See the Emperor’s edict, issued Oct. 28, 1794, to the Directors of the Circles of the Empire, containing an exhortation, &c. &c.—The third article of this exhortation is thus expressed—

“His Imperial Majesty expects that no state will shew, from individual interest, or from any other false principles, any backwardness against contributing to the general defence of the Empire. His Majesty would never have manifested any suspicions respecting this point, if unfortunately experience had not shewn him, that from the time the increase of the army had been determined to be triple the number of the former establishment, that the measure has not yet been accomplished to the present day.”

[xxix] The common estimate of human inhabitants on the globe, has been 950 millions—500 millions of which are apportioned to Asia. This estimate, I conceive, to be in a great measure conjectural, and very erroneous. There is a mistake of more than 100 millions in America.

[xxx] Abbe Raynal’s History of the Indies, Vol. 1. P. 50.

[xxxi] Ibid. Vol. 1. P. 131.

[xxxii] Ibid. Vol. 1. P. 186.

[xxxiii] Encyc. Art. China.

[xxxiv] According to the Indian Code—“A husband in distress, may deliver up his wife, if she consent; and a father may fell his son, if he have several”—That is—A mother of a family may be reduced to the condition of a prostitute,–and a son to that of a slave—“If a man kill an animal, such as a horse, a goat or a camel, one hand, and one foot shall be cut off from him”—Thus man is, by the laws, put upon a par with the brute creation.

The Indian Code says, “That a woman should by no means be mistress of her own actions; for if she have her own free will, she will always behave amiss”—“A woman shall never go out of the house without the consent of her husband”—“It is proper for a woman, (except under certain circumstances) after her husband’s death, to burn herself in the fire with his corpse—Every woman who thus burns herself, shall remain in paradise with her husband, an infinite number of years by destiny.”

“If a man strike a Bramin” or Priest “with his hand, or his foot, he shall have his hand or foot cut off.”—“If a Sooder or man of the fourth cast, be convicted of reading the Beids or sacred books, he shall have boiling oil poured into his mouth, if he should listen to the reading of the Beids of the Shafter, then oil, heated as before, shall be poured into his ears, and the orifice of his ears shall be stopped with melted wax”—“If a Sooder shall sit upon the carpet of a Bramin—the magistrate, having thrust a hot iron into his buttock, and branded him shall banish him the kingdom; or else he shall cut off his buttock—Whatever crime a Bramin shall commit, he shall not be put to death”—and his property is sacred and unalienable. Raynal’s Hist. of the Indies. Vol. 1. P. 66-71.

[xxxv] Raynal—Vol. I. p. 80-83.

[xxxvi] With Great-Britain.

[xxxvii] Under General Wayne.

[xxxviii] See the report of the Secretary of the Treasury, of Jan. 1795, containing “a plan for the further support of Publick Credit”—And the speech of Mr. Smith (S. C.) “on the subject of the Reduction of the Publick Debt”—December 1794—Published in a pamphlet.

[xxxix] Deut. ix. 5, 6.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!