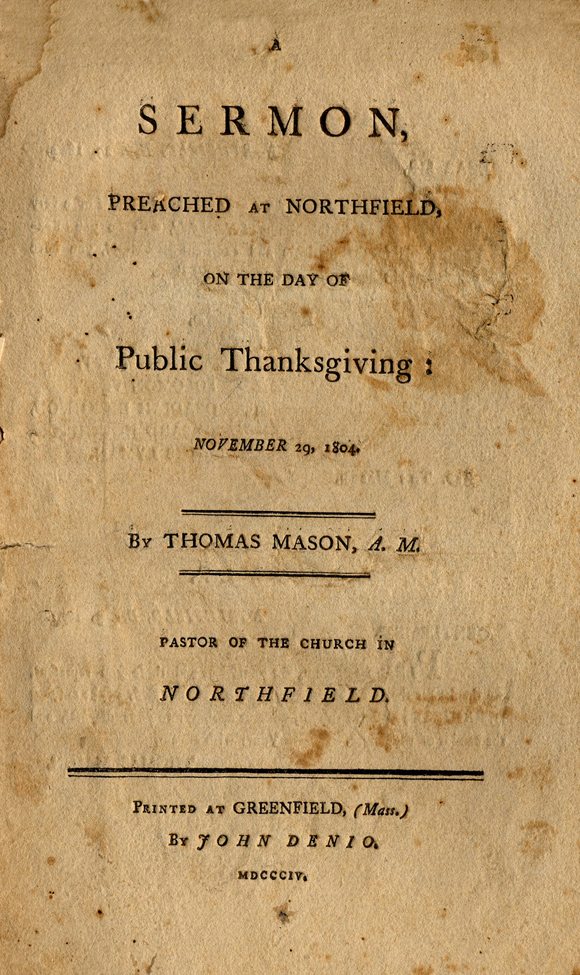

This sermon was preached by Thomas Mason on November 19, 1804.

SERMON,

PREACHED AT NORTHFIELD

ON THE DAY OF

PUBLIC THANKSGIVING:

NOVEMBER 29, 1804.

By THOMAS MASON, A. M.

PASTOR OF THE CHURCH IN

NORTHFIELD.

NORTHFIELD, Nov. 29, 1804.

DEAR SIR,

The underwritten, for themselves, and in behalf of a very considerable portion of the inhabitants of Northfield, wait on you to express their thanks for the patriotic and excellent SERMON, you have this day delivered; and to request a copy for the Press.

We are dear Sir, with great

Respect and esteem,

Your servants,

JOHN BARRETT,

SOLOMON VOSE,

OBADIAH DICKINSON,

EDWARD HOUGHTON,

CALEB LYMAN.

Rev. Th: Mason.

GENTLEMEN,

Please to accept, for yourselves and those you represent, my thanks for the favorable opinion, you have manifested, of the ensuing DISCOURSE; which I submit, without apology, to your disposal, and the candor of the public.

Yours with esteem,

THOMAS MASON.

SERMON.

The energies of the human mind are waked into action, by an almost infinite variety of motives. Of the abstract intelligent spirit, very little either is, or can be known by men. Yet, of its certain existence, we can entertain no reasonable doubts or suspicions. In its exercises we observe something, which we venture to call its attributes. But, strictly speaking, I conceive that, neither love, hatred, hope, fear, joy, grief, benevolence, gratitude, nor any of the intellectual or moral passions are found to be constituent parts of the human mind. The soul of man is a separate existence, independent of all the affections and passions, to which it is occasionally incident. Without motives to excite it—without objects to call its powers into action, the mind of man would be forever at rest, and remain in a state of perpetual infancy.

That infinite variety of objects, by which the rational mind is capable of being affected, has been appointed in infinite wisdom and goodness, as the means of its progression in the attainment of that perfection, for which it was originally designed. And all the passions, when properly regulated and controlled, are capable of contributing to this desirable end—of aiding man in the acquisition of his ultimate perfection.

The external ordinances of religion are all designed for awakening the powers of the human mind, and bringing into exercise its better, and more noble passions, and affections. To impress the soul with a principle of love to God, as a being perfect in all his attributes; and benevolence to man, under all his imperfections and necessities, is the final object of all religion—the end of all human perfection. And such measures, as are best fitted to the promotion of this end, are those, which ought to be cordially embraced, and steadily and uniformly pursued.

In all valuable improvements, external forms have always been found indispensably necessary. To attain the eminence at which it aspires, the human mind, as well as the body, must proceed by regular steps and gradations. Men may as well attempt to ascend the highest mountain, by a single effort of the body, as to rise to intellectual or moral eminence, without the intervention of external aids and assistances.

In all our pursuits, we ought always to make a clear distinction between the means, and the end; the external forms, and the thing to be acquired. As labor is not bread, and as books are not science; so neither are the external ordinances of religion to be accounted religion itself. There may be labor without bread, books without knowledge, and the forms of religion, without its genuine influences upon the soul. But, notwithstanding this, as we are not to expect bread without labor, nor knowledge without reading and meditation, so neither can we look for true religion, where its external forms and ordinances are not duly respected and regarded.

The separation of this day, to the business of religious worship, is designed as a mean of awakening the soul to sentiments of piety and devotion. And the method employed is justified, not only by the usage of our ancestors, but by the probable tendency of the thing itself.

In the very nature of the thing, it seems highly proper, at this season of the year, when the bounties of divine providence are collected for our participation, to come together, acknowledge the source of our enjoyments—adore that Being, whose benefaction they are—and by every exertion in our power, endeavor to render ourselves the subjects of his continued beneficence.

Gratitude to God is the particular religious affection, which the institution of this anniversary is designed to promote. We ought, therefore, as far as possible, minutely to understand what is embraced in this virtue of the Christian character.

It is no uncommon thing for men to confound this affection of the soul with that temper of mind, which they experience under circumstances, and in scenes of prosperity. Joy and gratitude are, therefore, often considered as terms of nearly the same import and signification. But though there is no incompatibility between the exercise of these affections; yet so diverse are they in their natures, that the one may, and ought to exist, where the other is wholly excluded. Gratitude to God is a principle, the reasons of which ought always to influence the human mind; but joy is an affection confined wholly to scenes of pleasure, and circumstances of prosperity. Their difference, therefore, cannot fail of being readily perceived, and clearly understood. For gratitude is an unchangeable principle, which ought perpetually to influence the human mind; while joy is simply a passion, the exercise of which is merely incidental, depending upon the particular external circumstances, in which we happen to be placed.

True gratitude to God does not, like mere joy, result from the particular pleasures, or present enjoyments we feel; but from a rational conviction that, we are under the government of an all perfect Being, the measures of whose providence are all wisely adapted to the promotion of our best, and truest interest. Though we may be under the pressure of extreme grief, disappointment and trouble; yet this ought, by no means, to interrupt, or abate the constant exercise of the most ardent gratitude to God. Even under experience of the keenest distresses, it is great impiety either to forget the most high, or to distrust the goodness of his providence. For we may be sure, if scenes of disappointment and adversity do not ultimately contribute to our happiness, it must be owing to the misimprovement, which we make of those providences. Besides the authority of his word, the perfections themselves of God are a certain pledge that, all things shall work together for the good of those, who love, regard, and obey his law.

The prime object of this day of thanksgiving is, not to inflate us with mere transports of joy; but to awaken in our breasts a sincere, and operative principle of gratitude to almighty God. And whether, in the course of the past season, we have experienced a series of prosperities, or felt the accumulated weight of heavy and severe adversities, we are bound to the like exercise of pious and devout gratitude.

I would not, however, be understood as giving credit to the absurd notion that, we are to reverse the constitution and laws of nature, by rejoicing while we are surrounded by the proper circumstances, and invested by the appropriate motives of grief. This would be a temper of mind, both unfit in its own nature, unfriendly in its consequences, and impossible to be reduced to practice. But the distinction already made between, both the principle, and the exercise of joy and gratitude is a sufficient defense against every imputation of this nature. All that I would insist upon is that, gratitude is a steady and immutable principle, which, when duly regulated, can receive neither force nor abatement in its exercise, by the accidental influence of either prosperity or adversity.

To awaken into action this steady and divine principle, which, without exciting motives, is liable to become formant in the human breast, is the design of this day’s religious devotions. We ought to be sensible, and seemingly to realize that, all the good, which we have enjoyed, is from the hand of God; and the evils, which we have suffered, are of our own procuring. But yet, such is the goodness of the divine nature, and the beneficence of God’s providence that, even these evils themselves capable of being converted into the ministers of human blessedness. Without the smallest prejudice to his other attributes, in all of which he is absolutely perfect, we may say that, God is all benevolence. Such, indeed, is the character, under which he is revealed to men; and as he is displayed in the order and administration of his providence.

But as all duties, whether social or religious, are designed for the benefit of man—to procure for him the best enjoyments of earth, and prepare him for the dignified glories of heaven, it becomes suitable that, our present religious devotions should be made subservient to the due regulation of human life. And, as the state of man here below is changeable and fluctuating–as prosperity and adversity are often found in so close contact, as almost to contend for the same place; it becomes us to be prepared for every possible alternation that may await us.

As health, peace, and prosperity are the proper seasons to shield ourselves against the evils, or support ourselves under the calamities of sickness, war, and adversity; so it cannot be judged a thing improvident, on an occasion of thanksgiving, to impress our minds with a deep sense of the uncontrollable vicissitudes of human life, that even the most unfriendly transition may not suddenly transport, or greatly confound us. For this reason I have chosen, as the subject of our religious meditations this day, those words of David in his Song of thanksgiving, recorded in the xviiith Psalm, at the 4th verse:

“The floods of ungodly men made me afraid.”

The occasion of the Psalmist’s tear, as expressed in the words just read, is a subject of the most serious alarm to every intelligent reflecting man—to every one, who cherishes a suitable concern for the present happiness, and future well being of the human family. Whoever does not coincide with the sentiment of our text—whoever is not seriously alarmed at the rising influence of the characters there described, must discover, at once, either a mind pinioned in the hard slavery of ignorance, or a heart overcharged with corruption and vice. The former, being freed from all terror by the sovereign power of ignorance, are easily persuaded to become the instruments of promoting the ungodly; while the latter, being interested in the growing authority of unrighteousness, can have no terrors, either to trouble or alarm them.

Whether or not we are menaced by the like terrors, it is not my design, at present, to enquire; but only to make room for a due improvement, from the experience and calamities of others. Admitting, however, that this is not our present, yet it may be our future case. And no precautions can be too great, to enable us, with firmness and composure, to meet the calamities we may be called to sustain.

To enable us to make a proper use of this sentiment of the royal Psalmist, I shall attend to the three following particulars:

First—I shall give a description of the character of those men, who are the occasion of this terror.

Secondly—I shall particularize some of the calamities which are likely to result from the undue influence of ungodly men.

And, thirdly, point out the behavior proper for a good man, in view of such dangers and distresses.

First, then; I am to give a description of the character of those men, who are the occasion of this terror.

The peculiar characteristic, which the Psalmist has given us of these men, is that they are ungodly. The thing implied in this epithet will present us with a correct idea of that character, which was the occasion of this solicitude.

By consulting the purport of the word ungodly, as applied by the Psalmist, we shall find it, perhaps, universally employed, as synonymous with the word irreligious. It was, therefore, the abounding, and influence of men of irreligion and impiety, which occasioned those painful and distressing apprehensions; which are suggested in our text.

Men of this character—those, who neither fear God, nor regard his law, are, under all circumstances, a detriment to society. And the danger of their influence is always in proportion to their ability, and the motives and means presented them, for doing injury to their fellow-men. Irreligious men may have the ability, without either the motives or the means for the exercise of injustice and oppression.—Added to this, they may have both ability and motives, while the means of annoyance are not placed within their power. In both these cases, though they are, in fact, harmless and inoffensive; yet, in nature, they are extremely poisonous and detestable creatures. But when to the ability is added both the motives and the means of fraud and violence—when the lust of a wicked domination is encouraged by prevailing ignorance, and a growing corruption of manners, then we are to look for those fearful times and awful calamities, which occasioned the extreme solicitude and terror of the Psalmist. Indeed, that ambition, which discovers itself by an excessive craving after power, is one of the most striking characteristics by which the men described in our text are to be distinguished.

In all ages and nations the great body of the people have been far removed from the allurements of ambition and personal promotion; and it cannot reasonably be supported that, they have ever knowingly volunteered, in aiding the measures of their own destruction. Where they have been misled, and have thus been made the instruments of their own ruin, they have always been indebted, for their delusion, to the artifices and fraud of the characters described in our text. The subtle machinations of ungodly and irreligious men have always been the occasion of those public and awful calamities, in which nations have been too often and fatally involved.

The author of our text had the most painful experience of the evils, resulting from the influence of men of this description. To what particular scene of distress he alludes, in the words under view, is not material for us to enquire. Several incidents of his reign are sufficient to justify the terrors, expressed in the words of our text. But, of all those that happened, there is no one so remarkable and conspicuous, as the rebellion of his son Absalom.

In the reign of David, the people of Israel were, perhaps, in the enjoyment of as many, and as great privileges, as their national character and circumstances could possibly admit. But this was no security against the artifices and intrigues of unprincipled and irreligious men; restless and aspiring after distinctions, to which neither their merits, nor services had ever given them the most distant pretensions.

The measure, employed by this aspiring demagogue to accomplish the wicked purpose of his heart, was such as has been copied, in all succeeding generations, by the turbulent minions of a most corrupt, and depraved ambition. To alarm the people with false terrors, and encourage them by deceitful and empty promises was the first measure of this arch factionist, to cheat them into wretchedness and ruin.—To wrest the scepter from him, who had been the instrument of his existence, and by whose partial favor he had been exalted to high eminence and honor, he descended to all the mean, and groveling artifices of indiscriminate flattery and adulation. With the most studied and malicious falsehood, he inveighs against the prudent measures, and wise maxims of his reverend father; and invites their confidence in himself, as a person combining that rare assemblage of virtues, whose private interest and ambition consisted solely in his anxious solicitude, for the prosperity and happiness of the people. As it is related by the sacred historian, “he rose up early, and stood beside the way of the gate—lamenting that no one was deputed of the king to sit in judgment, to hear, and avenge the cause of the oppressed. O, says he, that I were made judge in the land; that every man, who had a suit or a cause, might come unto me, and I would do them justice. And it was so that, when any man came nigh to him, to do him obeisance, he put forth his hand, and took him and kissed him. And on this manner did Absalom to all Israel, that came to the king for judgment. So Absalom stole the hearts of the men of Israel.”

These measures he pursued, with the most unremitting assiduity, for the full space of forty years, before his base and nefarious purposes were fully ripened for execution. Thus, by promises hollow as the dreary echoes of darkness, and salacious as the falling tears of the crocodile, he became the idol of the people.

The sequel of Absalom’s patriotism is too well known to need any particular rehearsal. It is, however, worthy of observation that, when he had assumed the royal vestments, his tender and extreme concern for the happiness of the people, yielded to the more excessive solicitude to stabilitate and confirm his usurped dominion. Like all his followers, in the annals of popular faction, he most decidedly testified that, like the lion, he crouched only to leap, and destroy. His dove-like tenderness suddenly disappeared, and the tiger, with all his rapacity, was at once discovered. His traitorous soul was, at first well pleased with the counsel of Ahithophel, to smite the king only; and reserve all the faithful of Israel, as his dependent and degraded vassals. But, upon more mature deliberation, his thirst of butchery and blood was better satisfied with the counsel of Hushai, to fall upon them, till, of all the men, there should not be so much as one left. In every step of his conspiracy, we see, in Absalom, clearly delineated the character described in our text. And, in the delusions into which the people of Israel were infatuated by him, we may discover that state of society, which occasioned the fears and terrors of the Psalmist.

Distinct from all other considerations, this pretended, exclusive concern for the public interest and welfare is a characteristic extremely unaccountable and suspicious. But when to this is added an evident defection of moral principle, and disregard of the divine authority, to every intelligent and considerate mind the inference is irresistibly conclusive. It is to the last degree distressing to remark the facility with which the great body of the people have been so often deluded by unprincipled and treacherous men. Honest and unsuspecting themselves, they have been led to imagine that zeal, to flaming, cannot be false; and that promises, so solemn, cannot be insincere. Thus deluded, they have called for more delusion—chanted, encore, to the siren long of their betrayers; till, as in the case of Absalom, the revolutionary yell has waked them from their lethargy, and brought their wretchedness in full prospect before them. With accidental variations, answering to the occasional distinctions in society, these are the measures, employed by the panders of a degenerate and corrupt ambition, to hurry mankind into scenes of wretchedness, and fatten on the spoils of their destruction.

Secondly—I shall particularize some of the calamities, which are likely to result from the undue influence of ungodly men.

The first evil, which society generally feels from the rising influence of irreligious men, is a dereliction of moral principle, and a consequent degeneracy of public character. Impious and unprincipled men are, generally, too well acquainted with the springs of human action to venture, at once, upon such daring innovations, as would flagrantly contradict those false promises, on which the popular favor has been erected. As all power is derived from the people, they must be preserved under the influence of delusion, till, by their own corruption, they are duly prepared for slavery, or the shackles of tyranny are fast riveted to their hands. While the moral principles have their due influence, men will be conscientiously restrained from affording support and patronage to men of this character, in the open avowal of their final purposes. And, as these cannot be ultimately secreted, the public mind must be gradually prepared to relish, and approve them. In order, therefore, to loosen them from all those religious restraints, by which the execution of their wicked purposes might be any way embarrassed, they are always industrious, in disseminating loose and demoralizing sentiments. The people are often taught to believe that, religion is a political scare-crow—that, its ministers are the mercenary tools of a pretended nobility—and that, the several institutions of society are all calculated to abridge them of their invaluable rights, and sink them into the lowest state of degradation and wretchedness. The success of these measures undermines the pillars—saps the foundation of society—and introduces an alarming degeneracy of public character.

In proportion as unprincipled men gain authority, irreligion and impiety will prevail. And ignorance, indecorum, and barbarity naturally follow, in the train of irreligion. By neglecting the institutions of the gospel, and consequently disregarding the authority of its doctrines, men naturally acquire a kind of rough, unfeeling, jealous, and savage spirit. This observation is strongly corroborated, both by the state of those nations, where Christianity is not patronized; and, in Christian lands, by the private characters of those particular individuals, who disavow the authority of the gospel. When, therefore, by the influence and intrigues of ungodly men, the public mind has become insensibly detached from the institutions and authority of the gospel, no firm foundation, either for the support of public faith, private friendship, or social enjoyment, can be anywhere discovered.

Christian nations, who have neglected their allegiance to their Saviour, are not in the state of others, who have never known the gospel. The superstition, with which their minds are shackled, may serve to render their barbarism less intolerable. But a national rejection of the gospel has always proved a rejection of all religion. No substitute has ever supplied its place. And, under these circumstances, the condition of society is a state of barbarism, without any of those alleviations, which heathen superstition affords.

A further, but natural consequence of the influence and authority of ungodly men, is the destruction of those gradations in society, by which wisdom and virtue are distinguished from folly and vice. This state of society, and the calamities attending it, the prophet Isaiah has well described.—“The mighty man,” says he, “and the man of war, the judge and the prophet, the prudent and the ancient, the honorable man and the counselor, shall be taken away—children shall be their princes, and babes shall rule over them. The people shall be oppressed every one by another, and every one by his neighbor; the child shall behave himself proudly against the ancient, and the base against the honorable.” In spite of all the clamors for equality, in every nation, whether barbarous or civilized, a nobility will exist. And where “nature’s nobility,” which conflicts in talents, learning, and integrity, is destroyed; and the public confidence is reposed in men restless, intriguing and treacherous, the rights of the people will soon be jeopardized, and folly and madness become the currency of the times.

The experience of nations will assure us that, the influence of irreligious and ungodly men has most prevailed under those governments, where there has been the most free and equal participation of all the privileges and rights of man. Under these circumstances, the characters, above described, enjoy the means of exercising, with impunity, those wicked and destructive artifices, by which their detestable purposes may be finally accomplished. But, under a government severe and inexorable, jealous of its own prerogatives, and vigilant in detecting those, who would encumber its motions, all schemes of innovation are rendered frustrate and abortive. Enjoying, therefore, as we do, a constitution of government equally propitious to humanity, and favorable to the pernicious artifices of irreligious and ungodly men, we are doubly interested in guarding, with a watchful eye, against the smallest innovation of those measures, which have secured to us such unexampled prosperity and happiness.

Another reason, why the most lenient and equitable governments are most exposed to the ravages of corrupt ambition, is because the full enjoyment of individual rights creates the most sudden disparity in the circumstances and conditions of men. This seldom fails of exciting the envy and resentment of the intemperate of all classes—men of confused fortunes, and desperate characters; and, eventually, of forming a junction with men of more happy auspices, and daring ambition—who are ready to become the leaders of the indolent, and intemperate, and the deluders of the ignorant and unsuspecting. And thus, it has generally happened that, the most lenient and equitable governments have been crushed by the wild, and ungoverned lusts of irreligious and ungodly men.

Again—What must be the state of a nation, when the influence of irreligious and ungodly men has risen to such an eminence, as to destroy the authority and obligation of an oath? When the divine authority is effaced from the human mind, the energies of human government must be feeble and ineffectual. And the spectacle of a people, where the wild lusts and passions of corrupt nature are let loose to their several pursuits, unrestrained by all laws human and divine, must be truly alarming and terrible.

Distinct from the judgments of heaven, which every serious and thoughtful man must contemplate, as the certain consequence of such corruption and degeneracy, we have every reason to believe that, such a state of society must nourish the feeds of its own destruction. The uniform experience of ages, as well as the reasonableness of the thing itself, confirms this persuasion, beyond the power of contradiction or doubt.

These are some of the evils, which are likely to befall a nation, deluded into the measures of its own destruction, by the influence and authority of irreligious and ungodly men. And surely, they are such as fully to justify all the apprehensions and terrors, expressed by the Psalmist, in the words of our text.

I now pass, thirdly, to point out the behavior proper for a good man, in view of such dangers and distresses.

Perhaps the flourishing, united, and happy state of our country may be urged by some, as a sufficient reason for omitting all enquiries and discussions of this nature. But it may well be insisted upon, that these very considerations are an ample apology for enquiring into the causes, in order to guard against the measures of public degeneracy and corruption. When the impositions, artifices, and intrigues of irreligious and ungodly men are known, only as related in the histories of ancient times, and far distant nations—when no competitions exist, but to emulate each other in virtue and goodness—when unprincipled and licentious demagogues are known, only by their obscurity, and the public contempt with which they are regarded—when, as a nation, we are entirely exempted from the evils of any political intolerance—when, among all classes of the people, but especially among the highest officers of the nation, there is discovered an ardent zeal, for the promotion of pure and undefiled religion—when the Sabbath itself, and all the ordinances of piety are regarded with a conscientious and scrupulous punctuality—when the rising generation is taught, by the laudable example of their parents, to respect, and constantly to attend the institutions and instructions of the gospel—when the prime qualifications, for the appointment to high and important offices, are honesty and ability—when, in the highest, and most conspicuous departments of government, the manners, sentiments, and morals of the people are thus guarded, by the example, the influence, and the authority of men of preeminent godliness—under these peculiarly happy and auspicious circumstances, I say, we are apt to fall into a dangerous security, and to feel such an immovable stability as no adverse occurrences can endanger. Admitting this to be our present condition, it is a proper season to awaken our minds to a due sense of the evils, which must attend the reversion of our circumstances. As those, who consider this to be a true statement of our affairs, will not be likely to make any personal application of the measures and characteristics of corruption and degeneracy; and, as every intelligent and tho’tful man, who imagines any present terrors from the domination of the irreligious and ungodly, will justify a persevering solicitude, for the restoration of the sober maxims of truth and righteousness; so, being divested of prejudice, all will be duly prepared for a right improvement of those reflections, which have now been made, from the suggestion of the Psalmist in our text.

The duty of a good man, under those troublesome and dangerous times suggested in our text, is plain and certain. And no doubts can exist, with respect to the leading characteristics of his behavior, unless he is under the influence of a cringing policy, by which he hopes to secure the favor of the impious and ungodly. But, in regard to the particulars of his demeanor, he will find room for the exercise of much prudence, discretion, and wisdom. Sometimes we must treat a fool according, and sometimes not according to his folly. To the harmlessness of the dove must be added the wisdom of the serpent. But, in all cases, there must be a strict and conscientious adherence to principle; and a firm reliance upon the final consequences of the policy of truth and righteousness. Though the enemies of virtue may flourish, and prosper for a season; yet the triumph of the wicked shall be short. Though an infuriated people may boast the messages of their chief, as being the voice of a God; yet the veil of delusion shall soon be rent; and the worm that corrodes his vitals shall suddenly be discovered. “The Lord of hosts will send among their fat ones leanness; and under their glory will he kindle a burning, like the burning of a fire.”

With regard to the ministers of the gospel, from the station in which they are placed, and the special command of God, they are under peculiar obligation to a manly, firm, and independent decision, both of character and conduct. They are set as the censors of the people; and, if they are not above the reproaches and menaces of unprincipled and corrupt men, they are unworthy the character which they are called to sustain. Against unfaithfulness in his ministers, God has appointed penalties paramount to all the evils, which irreligious and ungodly men can devise. And, though the floods of ungodly men may make them afraid, yet the fear of him, who has reserved the full vials of his indignation to another state of existence, should induce them to forego every evil, which the malice both of men and devils can inflict.

This is the duty, not only of the ministers of the gospel, but of all good men, in the several ranks and gradations of life. And those, who shrink from the contest, in dangerous and distressing times, will find much work for penitence, when a right sense of duty has regained its full dominion over their souls.

If, which God forbid! the times described in our text should ever be witnessed in this, our beloved, and hitherto happy country, every really good man would sustain with fortitude, and even glory in the buffetings of Satan, and all his impious satellites.

Let us, therefore, enjoy the good things which Providence presents, not with the vain presumption that, the thing which is, or has been, shall always necessarily be; but with the firm persuasion that, God has rested our happiness as a nation, upon our national virtue and patriotism. Under this conviction may we live; and, to the latest posterity, may the blessing of heaven be our portion, and our joy.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!