Courageous Women During the American Revolution

The contributions of women to the American Revolution are often neglected today. Many women demonstrated exemplary courage during this time. Here are a few examples.

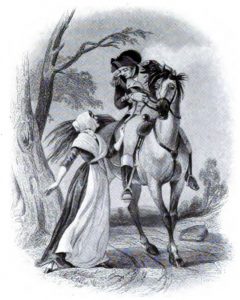

In April, 1777, a large British force arrived in Fairfield, Connecticut. Marching through nearby Danbury, they searched for American supplies and burned property owned by patriots.1 A messenger from Danbury was sent to Col. Henry Ludington, the leader of a nearby militia, alerting him to what was happening and seeking his help. His militia was scattered throughout the countryside and someone was needed to alert them and round them up. The Danbury messenger was exhausted from his ride and also unfamiliar with the area, so Sybil Ludington, Col. Ludington’s 16 year-old daughter, carried the message, riding throughout the night, across 40 miles of dangerous country.2 The militia gathered, and unable to save Danbury, were involved in the Battle of Ridgefield on April 27, 1777.

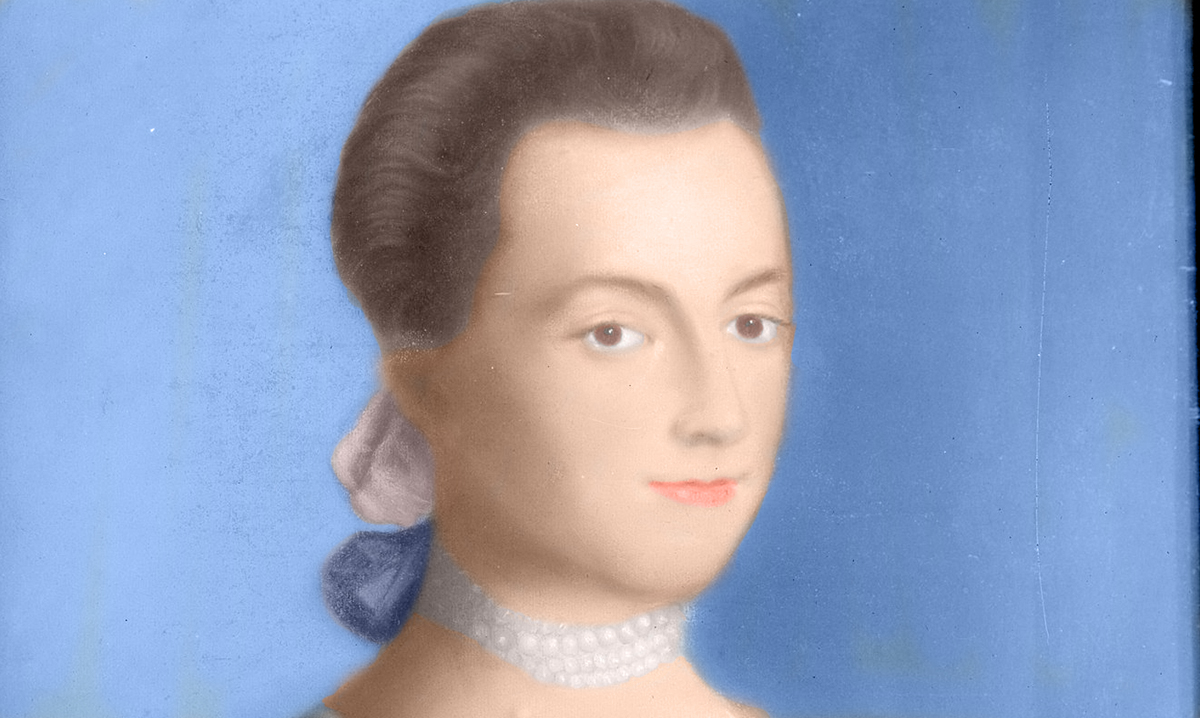

It was not just the men who signed the Declaration of Independence who risked death or imprisonment, or suffered personal tragedy, but their wives often did so as well — such as Elizabeth Lewis, wife of Declaration signer Francis Lewis.3 The Lewis’ home was in Long Island, and during the British occupation there, soldiers were dispatched to capture Elizabeth and destroy their property.4 As troops approached, a ship opened fire at the house (a cannonball even struck right beside where she stood) but Elizabeth refused to yield or retreat. The British captured her, holding her in dreary conditions with little food and no change of clothes. After several months, she was eventually freed through the efforts of George Washington and Congress but her health never recovered and she died in 1779.

Several women worked actively as spies for the American cause, supplying the army with much needed intelligence. For example, Lydia Darrah, hosted a meeting of British officers in December, 1777. Listening in secret to their meeting, and learning of their plans to attack George Washington’s army at White Marsh, she alerted the Americans, who were able to prepare for the planned surprise attack.5 Another example is Jane Thomas. Her husband, Col. John Thomas, was a prisoner of the British for fourteen months.6 On a visit to him, she learned of plans to attack the Americans at Cedar Spring. Riding almost sixty miles, she alerted them to danger, giving them time to prepare their defense against the British.7

These and many additional examples show that women of the Revolution played key roles in America’s fight for independence and should be honored during Women’s History Month.

* Originally published: Dec. 31, 2016

Endnotes

1 Richard Buel, “The Burning of Danbury,” ConnecticutHistory.org, accessed May 8, 2025.

2 Martha J. Lamb & Mrs. Burton Harrison, History of the city of New York (New York: A.S. Barnes Company, 1896), II:159-160; Willis Fletcher Johnson, Colonel Henry Ludington: A Memoir (New York: 1907), 89-90; National Postal Museum, “Sybil Ludington,” Smithsonian, accessed May 8, 2025.

3 Benson Lossing, Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the Declaration of American Independence (New York: George F. Cooledge & Brother, 1848), 71-73.

4 “Elizabeth Annesley Lewis,” The Pioneer Mothers of America (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), 3:119-126; L. Carroll Judson, A Biography of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence (Philadelphia: J. Dobson, 1839), 64-66.

5 Elizabeth F. Ellet, The Women of the American Revolution (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1848), 171-177

6 “Col. John and Jane Thomas,” The Historical Marker Database, accessed May 8, 2025.

7 Ellet, Women of the American Revolution (1848), 250-260.

At that time, attorney

At that time, attorney

from Virginia worked closely with Marquis de Lafayette.

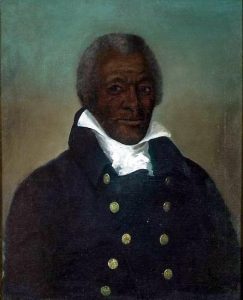

from Virginia worked closely with Marquis de Lafayette. Barton hand-selected about forty elite soldiers, who silently slipped past the main British force and overpowered the guards protecting the general. They had only to break down the door to his room and grab Prescott. One of the black commandos on the mission, Prince Sisson – a powerful man – stepped forward and charged the door. Using his own head as a battering ram, the locked door gave way and Prince entered the quarters and seized the surprised general.

Barton hand-selected about forty elite soldiers, who silently slipped past the main British force and overpowered the guards protecting the general. They had only to break down the door to his room and grab Prescott. One of the black commandos on the mission, Prince Sisson – a powerful man – stepped forward and charged the door. Using his own head as a battering ram, the locked door gave way and Prince entered the quarters and seized the surprised general. grandson of a slave, had a long career in public office.

grandson of a slave, had a long career in public office.

Columbus Day has become yet another occasion for tearing down our American heritage and heroes. Perhaps no other holiday in American history has so quickly gone from one honoring a venerated hero, to now portraying him as a

Columbus Day has become yet another occasion for tearing down our American heritage and heroes. Perhaps no other holiday in American history has so quickly gone from one honoring a venerated hero, to now portraying him as a  Have your children read

Have your children read

America’s first attempt at a national governing document was in 1777 with the Articles of Confederation.

America’s first attempt at a national governing document was in 1777 with the Articles of Confederation. James Madison agreed:

James Madison agreed: Many delegates involved with writing the Constitution were trained in theology or ministry,

Many delegates involved with writing the Constitution were trained in theology or ministry,

The

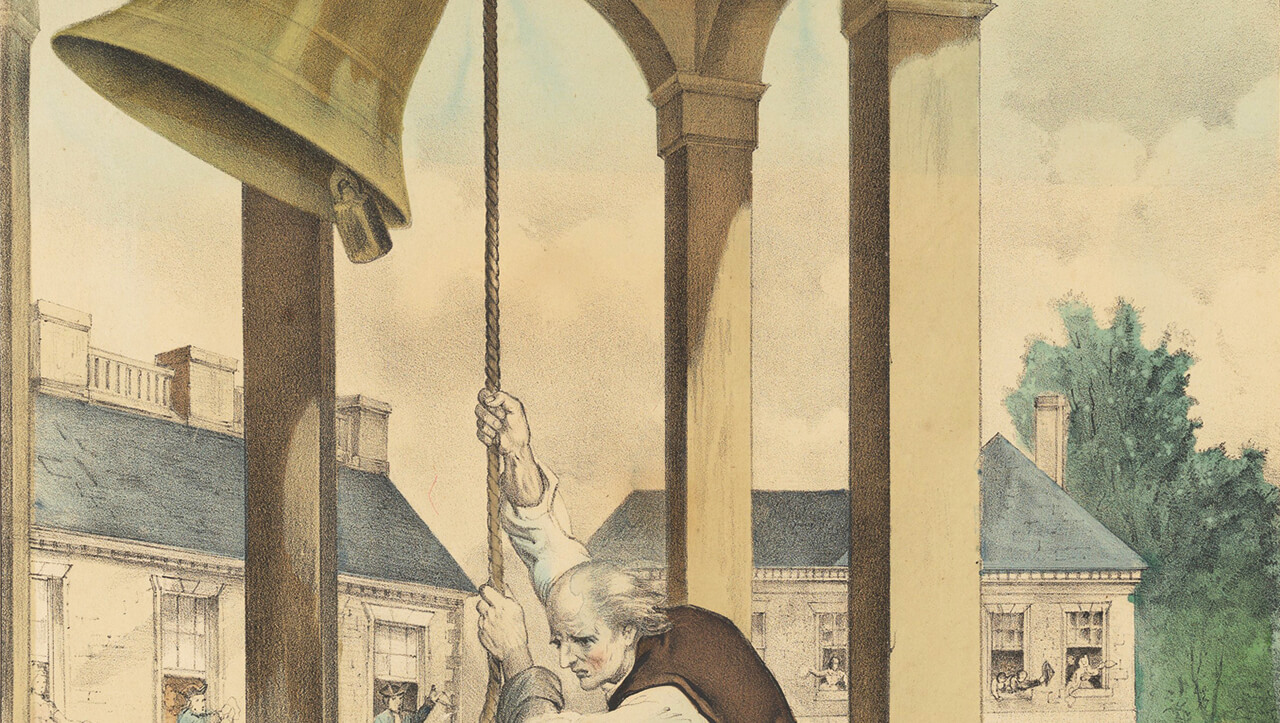

The  Of course, there were many other important times that the Liberty Bell was rung, including on July 8, 1776 to call citizens to assemble together outside the State House for a special announcement. At that time, the new Declaration of Independence

Of course, there were many other important times that the Liberty Bell was rung, including on July 8, 1776 to call citizens to assemble together outside the State House for a special announcement. At that time, the new Declaration of Independence

The Continental Congress, not in session at that time, took up the issue when it returned and on

The Continental Congress, not in session at that time, took up the issue when it returned and on  Following this, the Navy slowly shrank in size until it

Following this, the Navy slowly shrank in size until it  On

On

Timothy Dwight (pictured on the left), who had

Timothy Dwight (pictured on the left), who had  An ardent champion of military chaplains was George Washington. One of the first things he did as a young officer in the

An ardent champion of military chaplains was George Washington. One of the first things he did as a young officer in the

[I]n what sense can [America] be called a Christian nation? Not in the sense that Christianity is the established religion or that the people are in any manner compelled to support it. . . . Neither is it Christian in the sense that all its citizens are either in fact or name Christians. On the contrary, all religions have free scope within our borders. Numbers of our people profess other religions, and many reject all. Nor is it Christian in the sense that a profession of Christianity is a condition of holding office or otherwise engaging in public service, or essential to recognition either politically or socially. . . . Nevertheless, we constantly speak of this republic as a Christian nation – in fact, as the leading Christian nation of the world.

[I]n what sense can [America] be called a Christian nation? Not in the sense that Christianity is the established religion or that the people are in any manner compelled to support it. . . . Neither is it Christian in the sense that all its citizens are either in fact or name Christians. On the contrary, all religions have free scope within our borders. Numbers of our people profess other religions, and many reject all. Nor is it Christian in the sense that a profession of Christianity is a condition of holding office or otherwise engaging in public service, or essential to recognition either politically or socially. . . . Nevertheless, we constantly speak of this republic as a Christian nation – in fact, as the leading Christian nation of the world. No nation can be strong except in the strength of God, or safe except in His defense. The trust of our people in God should be declared on our national coins. You will cause a device to be prepared without unnecessary delay with a motto expressing in the fewest and tersest words possible this national recognition.

No nation can be strong except in the strength of God, or safe except in His defense. The trust of our people in God should be declared on our national coins. You will cause a device to be prepared without unnecessary delay with a motto expressing in the fewest and tersest words possible this national recognition. As George Washington told the nation when he left the presidency:

As George Washington told the nation when he left the presidency:

Princeton was

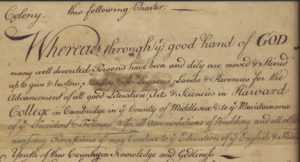

Princeton was  Harvard University was

Harvard University was