by David Barton

Some of the first acts of the Obama presidential administration make it clear that there has been a dramatic change in the way that traditional religious faith is going to be handled at the White House. For example, when the White House website went public immediately following President Obama’s inauguration, it dropped the previously prominent section on the faith-based office.

A second visible change was related to hiring protections for faith-based activities and organizations. On February 5, 2009, President Obama announced that he would no longer extend the same unqualified level of hiring protections observed by the previous administration but instead would extend those traditional religious protections to faith-based organizations only on a “case-by-case” basis.1

Significantly, hiring protections allow religious organizations to hire those employees who hold the same religious convictions as the organization. As a result, groups such as Catholic Relief Services can hire just Catholics; and the same is true with Protestant, Jewish, and other religious groups. With hiring protections, religious groups cannot be forced to hire those who disagree with their beliefs and values – for example, Evangelical organizations cannot be required to hire homosexuals, pro-life groups don’t have to hire pro-choice advocates, etc.

Hiring protections are inherent within the First Amendment’s guarantee for religious liberty and right of association, and were additionally statutorily established in Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Congress subsequently strengthened those protections, declaring that any “religious corporation, association, education institution, or society” could consider the applicants’ religious faith during the hiring process.2 The Supreme Court upheld hiring protections in 1987,3 and Congress has included those protections in numerous federal laws.4 But when Democrats regained Congress in 2007, on a party-line vote they began removing hiring protections for faith-based organizations.5

The current concern about the weakening of traditional faith-based hiring protections was heightened when the White House announced President Obama’s commitment to “pass the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.”6 This act fully repeals faith-based hiring protections related to Biblical standards of morality and behavior, thus directly attacking the theological autonomy of churches, synagogues, and every other type of religious organization by not allowing them to choose whether or not they want to hire homosexuals onto their ministry staffs.

The administration’s third attack on religion occurred in the President’s stimulus bill, which included a provision specifically denying stimulus funds to renovate higher educational facilities “(i) used for sectarian instruction or religious worship; or (ii) in which a substantial portion of the functions of the facilities are subsumed in a religious mission.”7 As Republican Senator Jim DeMint (SC) explained, “any university or college that takes any of the money in this bill to renovate an auditorium, a dorm, or student center could not hold a National Prayer Breakfast.”8 Sen. DeMint therefore introduced an amendment to “allow the free exercise of religion at institutions of higher education that receive funding,”9 but his amendment was defeated along a party-line vote.

The fourth attack on tradition religious faith appeared in President Obama’s 2010 proposed budget, which included a seven-percent cut in the deduction for charitable giving. Experts calculate that this will result in a drop of $6 billion in contributions to charitable organizations, including to religious groups.10

The fifth attack was the White House’s announcement that it will repeal conscience protection for health care workers who refuse to participate in abortions or other health activities that violate their consciences.11

In order to fully understand the far-reaching ramifications of this announcement, it will be helpful to review the history of conscience protection in the United States.

— — — ◊ ◊ ◊ — — —

Today’s liberals and secularists attempt to relegate the effects of America’s Judeo-Christian heritage exclusively to the realm of a personal theological choice, ignoring the fact that Judeo-Christian teachings also encompass a philosophy of living that is directly proportional to the degree of civil liberty enjoyed in a society. Early statesman Dewitt Clinton (1769-1828) correctly recognized that Biblical faith applies not just “to our destiny in the world to come” but also “in reference to its influence on this world,” and therefore must always “be contemplated in [these] two important aspects.”12

While today’s post-modern critics refuse to acknowledge the dual aspects of Judeo-Christian faith, America’s Framers wisely recognized and heartily endorsed the influence of those teachings on the civil arena – especially on the formation of America’s unique republican (i.e., elective ) form of government:

The Bible. . . . [i]s the most republican book in the world.13 JOHN ADAMS, SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION, FRAMER OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS, U. S. PRESIDENT

I have always considered Christianity as the strong ground of republicanism. . . . It is only necessary for republicanism to ally itself to the Christian religion to overturn all the corrupted political . . . institutions in the world.14 BENJAMIN RUSH, SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION, RATIFIER OF THE U. S. CONSTITUTION

[T]he genuine source of correct republican principles is the Bible, particularly the New Testament or the Christian religion. . . . and to this we owe our free constitutions of government.15 NOAH WEBSTER, REVOLUTIONARY SOLDIER, LEGISLATOR, JUDGE

They . . . who are decrying the Christian religion . . . are undermining . . . the best security for the duration of free governments.16 CHARLES CARROLL, SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION, FRAMER OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS

[T]o the free and universal reading of the Bible . . . men were much indebted for right views of civil liberty.17 DANIEL WEBSTER, “DEFENDER OF THE CONSTITUTION”

Scores of other Framers, statesmen, and courts made similarly succinct declarations about how the Judeo-Christian Scriptures not only shaped republicanism18 but also many other unique aspects of our civil culture.

For example, when Benjamin Franklin founded America’s first hospital, he chose the Bible’s story of the Good Samaritan for its logo, with the passage from Luke 10:35 beneath: “Take care of him and I will repay thee.” Significantly, it was Jesus Who not only taught that it was proper to help the hurt (Luke 10:25-37) but He also taught that it was proper to feed the hungry, befriend the stranger, clothe the needy, visit the bedridden, and support the imprisoned (Matthew 25:34-40) – and to do so for strangers (Luke 10:27-37) as well as for enemies (Matthew 9:35-39). His teachings provide the true standard for charitable relief and civil benevolence.

Scriptural teachings were so important to society at large that America’s most famous public school textbooks taught students Biblical teachings such as the Good Samaritan;19 and even today, states continue to pass “Good Samaritan” statutes to protect willing volunteers (i.e., Good Samaritans) from legal liability for good-faith assistance efforts. Incontrovertibly, Biblical teaching such as the Good Samaritan, the Golden Rule (“Do unto others and you would have them do unto you” Matthew 7:12), and many others have elevated the culture; and even though these specific teachings are exclusive to Christianity, their primary application is to civil society.

The Framers thus properly recognized Christian teachings as the basis of America’s great civil benevolence – its unprecedented willingness to help others:

Christian benevolence makes it our indispensable duty to lay ourselves out to serve our fellow-creatures to the utmost of our power.20 JOHN ADAMS

[T]he doctrines promulgated by Jesus and His apostles [include] lessons of peace, of benevolence, of meekness, of brotherly love, [and] of charity.21 JOHN QUINCY ADAMS, U. S. PRESIDENT

Let the religious element in man’s nature be neglected . . . and he becomes the creature of selfish passion. . . . [T]he cultivation of the religious sentiment . . . incites to general benevolence.22 DANIEL WEBSTER

Christianity . . . introduce[ed] a better and more enlightened sense of right and justice. . . . It taught the duty of benevolence to strangers.23 JAMES KENT, “FATHER OF AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE”

The Christian philosophy, in its tenderness for human infirmities, strongly inculcates principles of . . . benevolence.24 RICHARD HENRY LEE, SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION, FRAMER OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS

Significantly, nations that are primarily secular in their orientation (or those predominated by non-Judeo-Christian religions such as Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Shinto, Confucianism, Jainism, Taoism, Sikhism, Bahá’í, Diasporic, Juche, etc.) rarely become involved in benevolent endeavors, and certainly are not aggressive in organizing humanitarian relief. In fact, when the massive tsunami devastated Muslim Indonesia in 2004, other Muslim nations did little to assist a nation of their own faith, yet America – even though considered by Indonesia’s dominant religion to be the “Great Satan” – was quickly on the scene, providing assistance in money, supplies, labor, and technology.

The benevolence that characterizes America – the compassion and humanitarianism that we have inculcated into our culture – is the unique product of the Bible; and non- and even anti-religious Americans have been trained in Biblical benevolence as characteristic of our culture (even if they do not recognize the source of that principle!).

The Ten Commandments provide another example of Biblical teachings that are also primarily societal. As our early leaders noted:

If “Thou shalt not covet,” and “Thou shalt not steal,” were not commandments of Heaven, they must be made inviolable precepts in every society before it can be civilized or made free.25 JOHN ADAMS

The law given from Sinai was a civil and municipal as well as a moral and religious code . . . laws essential to the existence of men in society and most of which have been enacted by every nation which ever professed any code of laws.26 JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

The fact that Biblical teachings provided so many positive effects on society has been understood by American leaders for over two centuries. For example, President Harry S. Truman acknowledged:

The fundamental basis of this Nation’s law was given to Moses on the Mount. The fundamental basis of our Bill of Rights comes from the teachings which we get from Exodus and St. Matthew, from Isaiah and St. Paul. I don’t think we emphasize that enough these days.27

President Teddy Roosevelt agreed:

The Decalogue and the Golden Rule must stand as the foundation of every successful effort to better either our social or our political life.28

In short, the Judeo-Christian system is the basis of many of our cherished civil traits – including our current affection for and commitment to protecting the RIGHTS OF CONSCIENCE.

According to America’s first dictionary, “CONSCIENCE” is:

Internal judgment of right and wrong; the principle within us that decides on the lawfulness or unlawfulness of our own actions and instantly approves or condemns them. Conscience is first occupied in ascertaining our duty before we proceed to action, then in judging of our actions when performed. Conscience is called by some writers the moral sense.29

That dictionary then gave a Biblical example to illustrate the meaning of the word:

Being convicted by their own conscience, they went out one by one. John 8.30

Significantly, Christ and His Apostles made the rights of conscience a repeated subject of emphasis, with thirty references to that topic in the New Testament alone. The warning is even issued that if an individual “wounds a weak conscience of another, you have sinned” (1 Corinthians 8:12). Christians were therefore instructed to respect the differing rights of conscience (v. 13). (See also I Corinthians 10:27-29.) Christianity set forth clear protection for the rights of conscience.

However, in the twelve centuries that comprised the Dark Ages, the church sadly abandoned those doctrines; but beginning in the fifteenth century, Biblical leaders began to re-embrace those original teachings. As a result, Menno Simons in Friesland (central Europe),31 Jacobus Arminius in Netherlands,32 John Calvin in France,33 and others, advocated a return to protection for the rights of conscience. Subsequent writers, including Christian philosophers such as John Locke and Charles Montesquieu, also encouraged protection for the rights of conscience that had been reintroduced by Christian leaders.34

Those renewed Biblical teachings on protecting the rights of conscience were eventually carried to America, where they took root and grew to maturity at a rapid rate, having been planted in virgin soil completely uncontaminated by the apostasy of the previous twelve centuries. Hence, Christianity – especially as imported to America – became the world’s single greatest historical force in securing non-coercion and the rights of conscience.

For example, in 1640 when the Rev. Roger Williams established Providence, he penned its governing document declaring:

We agree, as formerly hath been the liberties of the town, so still, to hold forth liberty of conscience.35

Similar protections also became part of subsequent early American documents, including the 1649 Maryland “Toleration Act,”36 the 1663 charter for Rhode Island,37 the 1664 Charter for Jersey,38 the 1665 Charter for Carolina,39 and the 1669 Constitutions of Carolina.40 Christian minister William Penn incorporated the same protections into the governing documents he authored, including in 1676 for West Jersey,41 in 1682 for Pennsylvania,42 and in 1701 for Delaware.43 There are many additional examples.

Historically speaking, it was the followers of Biblical Christianity who vigorously pursued and first achieved the protection for the rights of conscience that subsequently became a central characteristic of the American civil fabric. Even Roscoe Pound (1870-1964; a professor at four different law schools and the Dean of the law schools at Harvard and the University of Nebraska) acknowledged that it was the Biblical-minded Puritans who first brought these rights to the forefront of civil protection;44 and in the words of an 1824 court:

[B]efore [the American colonial] period, the principle of liberty of conscience appeared in the laws of no people, the axiom of no government, the institutes of no society, and scarcely in the temper of any man.45

So thoroughly was American thinking inculcated with protecting conscience that when America separated from Great Britain in 1776, the original state constitutions immediately secured the rights of conscience so long expounded by Christian leaders. (See, for example, the constitutions of Virginia, 1776;46 Delaware, 1776;47 North Carolina, 1776;48 Pennsylvania, 1776;49 New Jersey, 1776;50 Vermont, 1777;51 New York, 1777;52 South Carolina, 1778;53 Massachusetts, 1780;54> New Hampshire, 1784;55 etc.)

America’s Framers openly praised those protections. For example, Governor William Livingston (a devout Christian and a signer of the U. S. Constitution) declared:

Consciences of men are not the objects of human legislation.56

John Jay (an author of the Federalist Papers, original Chief Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court, and President of the American Bible Society) likewise rejoiced that:

Security under our constitution is given to the rights of conscience.57

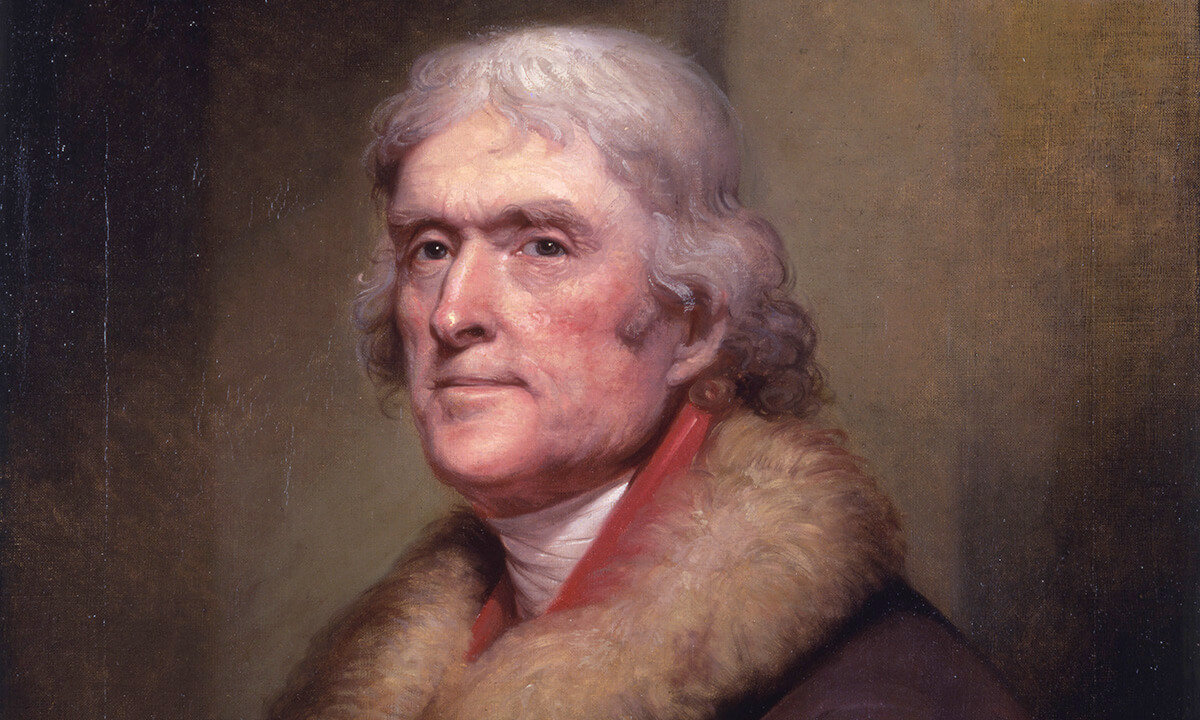

Thomas Jefferson (a signer of the Declaration and a U. S. President) repeatedly praised America’s protections for the rights of conscience:

No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience.58

[O]ur rulers can have no authority over such natural rights only as we have submitted to them. The rights of conscience we never submitted.59

A right to take the side which every man’s conscience approves . . . is too precious a right – and too favorable to the preservation of liberty – not to be protected.60

It is inconsistent with the spirit of our laws and Constitution to force tender consciences.61

James Madison (a signer of the Constitution, a framer of the Bill of Rights, and a U. S. President) similarly affirmed:

Government is instituted to protect property of every sort. . . . [and] conscience is the most sacred of all property.62

Clearly, the right of conscience was a precious right under our Constitution. Today, the safeguards for the rights of conscience originally pioneered by Christian leaders now appear in forty-seven state constitutions and have been extended to cover many diverse areas of life. Consequently:

- pacifists and conscientious objectors are not forced to fight in wars;63

- Jehovah’s Witnesses are not required to say the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools;64

- the Amish are not required to complete the standard compulsory twelve years of education;65

- Christian Scientists are not forced to have their children vaccinated or undergo medical procedures often required by state laws;66

- Muslim and Jewish men are not required to shave their beards in jobs that otherwise require employees to be clean-shaven;67

- Seventh-Day Adventists cannot be penalized for refusing to work at their jobs on Saturday;68

and there are many additional examples.

America has a centuries-long and cherished tradition of protection for the rights of conscience, but President Obama has announced that he will rescind regulations protecting those rights for medical workers.

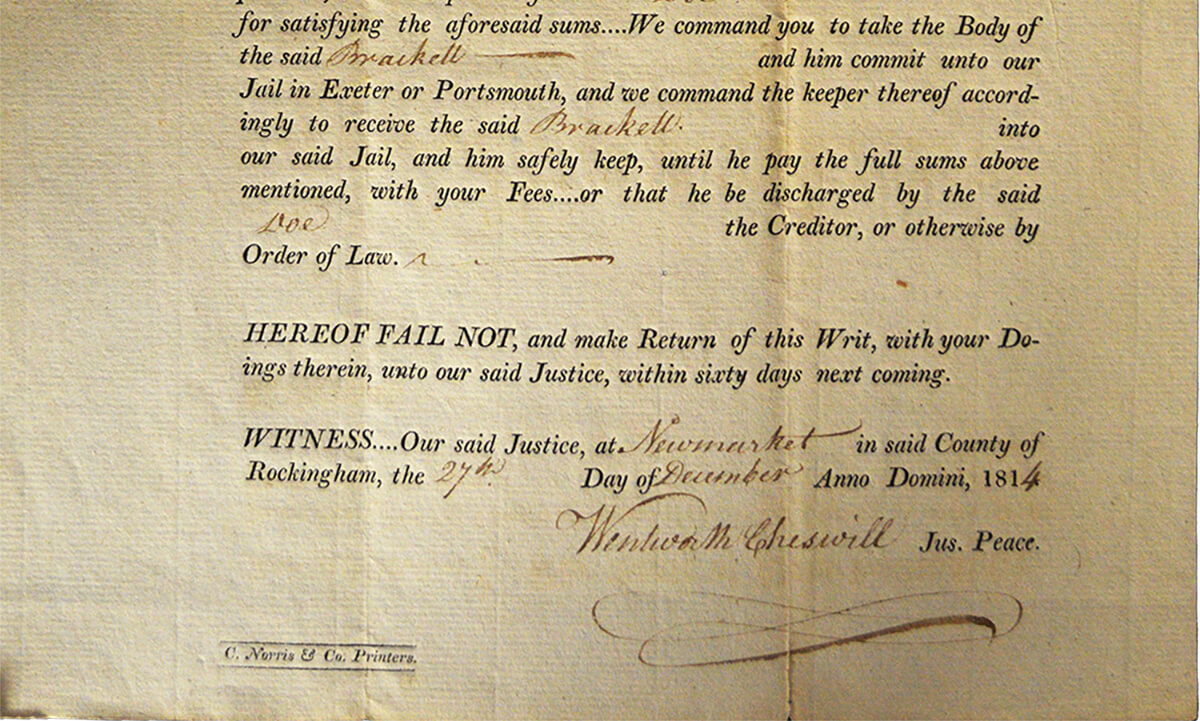

Significantly, immediately after the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade abortion-on-demand decision, Congress promptly passed medical conscience protection to prohibit discrimination against doctors and nurses who for conscience sake declined to participate in abortions; the law even ordered that federal funds be withheld from medical institutions not providing conscience protection.69 (Those federal requirements were included in a series of acts from the 1970s through 2008.70)

While medical conscience protections originally centered on abortion,71 they were soon expanded to include other controversial medical areas, including sterilization,72 contraception,73 and executions.74 More recent areas of medical conscience concern include issues related to artificial insemination of lesbian couples, “surrogate” motherhood, cloning, embryonic stem-cell procedures, and euthanasia.

In fact, many doctors and pharmacists are completely unwilling to prescribe abortifacient drugs or to dispense the life-ending drugs associated with Washington State’s law authorizing euthanasia.

Even though conscience protections for medial personnel are deeply-rooted in federal law, a recent review found that federal funds were improperly being given to medical facilities and programs that did not provide conscience protection for workers – a violation of federal law. Therefore, Mike Leavitt, the former Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, instituted new regulations to “cut off federal funding for any state or local government, hospital, health plan, clinic or other entity that does not accommodate doctors, nurses, pharmacists and other employees who refuse to participate in care they find ethically, morally, or religiously objectionable.”75

As the Department of Health and Human Services explained: “Over the past three decades, Congress enacted several statutes to safeguard the freedom of health care providers to practice according to their conscience. The new regulation will increase awareness of and compliance with these laws.”76 Under those regulations, some 584,000 health-care organizations must provide written certification that they are in compliance with current federal laws on conscious protection or else lose federal funding (or even return funding they have already received).

The response of pro-abortion advocates to enforcing the existing conscience protection regulations was immediate:

- In the U. S. Senate in 2008, Senators Patty Murray (D-Wash) and Hillary Rodham Clinton (D-N.Y) filed S. 2077 to invalidate the conscience protection regulations.

- In 2009, the ACLU and pro-abortion groups filed a lawsuit against the regulations.78

- President Obama announced that he would rescind the conscience protections.79

It is regrettable not only that the President should actively encourage non-enforcement of existing federal laws but that he should also seek to coerce healthcare workers to participate in performing abortions or other medical practices that violate their moral, ethical, or religious convictions.

The response of many physicians to the President’s announcement was clear and unambiguous. For example, U. S. Senator Tom Coburn (a practicing ob/gyn physician who is strongly pro-life) announced:

“I think a lot of us will go to jail.” . . . Coburn meant that doctors, himself included, are willing to defy the law before agreeing to perform medical procedures that violate their conscience.80

Regrettably, with the repeal of medical conscience protection regulations, many healthcare professionals may be forced to choose between their conscience and their career. Yet, why stop here? Why not force Jehovah’s Witnesses to say the Pledge of Allegiance or forfeit access to public education? Or why not require pacifists to go to war or lose government benefits such as Social Security or Medicaid? Every one of these coercive scenarios should be reprehensible to citizens – and so, too, should be the repeal of conscience protection for healthcare workers.

Protection for the rights of conscience and non-coercion is just one more reason that Biblical Judeo-Christianity is so beneficial to a culture, and why religious influence must be preserved in America today and secularism must be resisted. History – both ancient and modern – demonstrates that neither secular, Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, nor any other non-Judeo-Christian nation offers the societal benefits enjoyed in Judeo-Christian America.

Endnotes

1 David Brody, The Brody File, “The Faith-Based ‘Hiring Protection’ Issue,” February 5, 2009 (at: https://www.cbn.com/cbnnews/535994.aspx).

2 “Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (at: https://www.eeoc.gov/policy/vii.html).

3 Corporation of the Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints v. Amos, 483 U.S. 327 (1987).

4 President Clinton signed four such laws, including the 1996 Welfare Reform Act and the 1998 Community Services Block Grant Act. In the 108th Congress, hiring protections for faith-based organizations were included in Head Start and the Workforce Investment Act (WIA). Congress also reaffirmed hiring protections for private schools that participate in the D.C. voucher program enacted in the Fiscal 2004 Omnibus Appropriations Act. See, for example, “Public Law 104-193, 104th Congress,” GPO.gov, August 22, 1996 (at: https://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=104_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ193.104); “Community Services Block Grant Act,” National Community Action Foundation (accessed on March 12, 2009).

5 See, for example, “Conference Report on H.R. 1429 – Improving Head Start Act of 2007,” which notes “Representative Fortuno [Republican] sought to add hiring protections to the Head Start Reauthorization by offering an amendment in Committee, but the amendment failed along a party line vote. Rep. Fortuno also submitted his amendment to Rules when H.R. 1429 was brought to the House floor for a vote, but the [Democrat] Rules Committee did not allow his amendment. During debate on H.R. 1429, the Republican Motion to Recommit offered would have allowed faith-based organizations that receive Head Start funding to be able to hire individuals based upon religious affiliation or belief. The MTR explicitly prohibited federal funds from being used for worship, instruction or proselytization. The MTR would have also prohibited the federal government from requiring a faith-based organization to alter its form of internal governance or remove religious art, icons, scripture, or other symbols. While the House debated the issue of faith-based hiring protections, the Senate bill did not include language to allow faith-based organizations to be providers. This conference report codifies the provision which allows faith-based organizations to be providers, however, it does not contain language that would provide hiring protections to such organizations. Simply, this conference report would mean that faith-based organizations that run Head Start programs would have to hire any person who has the appropriate credentials, even if he or she does not agree with the faith or adhere to the mission of the employing organization.” See this at Republican Study Committee, November 14, 2007.

6 The White House, “The Agenda; Civil Rights; Combat Employment Discrimination” (at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/agenda/civil_rights/).

7. “H.R. 1: American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009,” Thomas, February 17, 2009 (at: https://thomas.loc.gov/home/approp/app09.html), “Title XIV: State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, Sec. 14004. Uses of Funds by Institutions of Higher Education.”

8 “Congressional Record,” Thomas, February 5, 2009, S1650 (at: https://thomas.loc.gov/home/r111query.html).

9 “U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes: On the Amendment (DeMint Amdt. No. 189),” United States Senate, February 5, 2009 (at: https://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=111&session=1&vote=00047).

10 Karin Hamilton, “Will Obama tax plan hurt religious groups?,” USA Today, March 22, 2009 (at: https://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2009-03-22-obama-church-giving_N.htm).

11 See, for example, David Stout, “Obama Set to Undo ‘Conscience’ Rule for Health Workers,” New York Times, February 27, 2009.

12 William W. Campbell, The Life and Writings of DeWitt Clinton (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1849), p. 305, in an address delivered to the American Bible Society, May 8, 1823.

13 John Adams and Benjamin Rush, The Spur of Fame: Dialogues of John Adams and Benjamin Rush 1805-1813, John A. Schutz, editor (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1966) p. 82, letter from John Adams to Benjamin Rush, February 2, 1807.

14 Benjamin Rush, Letters of Benjamin Rush, L. H. Butterfield, editor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), Vol. II, pp. 820-821, letter to Thomas Jefferson, August 22, 1800.

15 Noah Webster, History of the United States (New Haven: Durrie & Peck, 1832), p. 6, 300.

16 Bernard C. Steiner, The Life and Correspondence of James McHenry (Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers, 1907), p. 475, letter from Charles Carroll to James McHenry, November 4, 1800.

17 Daniel Webster, Address Delivered at Bunker Hill, June 17, 1843, on the Completion of the Monument (Boston: Tappan and Dennet, 1843), p. 17.

18 See, for example, John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1854), Vol. IX, p. 636, letter to Benjamin Rush, August 28, 1811; John Hancock, Independent Chronicle (Boston newspaper), November 2, 1780, last page; Abram English Brown, John Hancock, His Book (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1898), p. 269, “Inaugural Address: 1780;” Updegraph v. Commonwealth; 11 Serg. & R. 393, 406 (Sup.Ct. Penn. 1824); Jedidiah Morse, A Sermon, Exhibiting the Present Dangers and Consequent Duties of the Citizens of the United States of America (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1799), p. 9; Jacob Rush, Charges and Extracts of Charges on Moral and Religious Subjects (Philadelphia Geo Forman, 1804), p. 58, “A Charge on Patriotism,” April, 1799; K. Alan Snyder, Defining Noah Webster: Mind and Morals in the Early Republic (New York: University Press of America, 1990), p. 253, letter to James Madison, October 16, 1829; Noah Webster, A Collection of Papers on Political, Literary, and Moral Subjects (New York: Webster and Clark, 1843), p. 292, “Reply to a Letter of David McClure on the Subject of the Proper Course of Study in the Girard College, Philadelphia,” October 25, 1836; John Witherspoon, The Works of the Rev. John Witherspoon (Philadelphia: William W. Woodard, 1802), Vol. III, pp. 41-42, 46, “The Dominion of Providence Over the Passions of Men,” May 17, 1776; and many, many others.

19 William H. McGuffey, McGuffey First Reader (Cincinnati: Truman and Smith, 1836-1853), Lesson XX, p. 47.

20 John Adams, Familiar Letters of John Adams and His Wife Abigail Adams, During the Revolution (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1875), p. 118, letter to Abigail Adams, October 29, 1775.

21 John Quincy Adams, An Oration Delivered Before the Inhabitants of the Town of Newburyport at Their Request on the Sixty-First Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (Newburyport: Morss and Brewster, 1837), p. 61.

22 Daniel Webster, The Works of Daniel Webster (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1853), Vol. II, p. 615, “The Addition to the Capitol,” July 4, 1851.

23 James Kent, Commentaries on American Law (New York: O. Halsted, 1826), Vol. I, p. 10.

24 Richard Henry Lee, The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, James Curtis Ballagh, editor (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914), Vol. II, p. 343, letter to Samuel Adams, March 14, 1785.

25 John Adams, A Defense of the Constitution of Government of the United States of America (Philadelphia: William Young, 1797), Vol. III, p. 217, “The Right Constitution of a Commonwealth Examined,” Letter VI.

26 John Quincy Adams, Letters of John Quincy Adams to His Son on the Bible and Its Teachings (Aubrun, NY: Derby, Miller & Co, 1848), p. 61.

27 Harry S. Truman, “Address Before the Attorney General’s conference on Law Enforcement Problems,” February 15, 1950, American Presidency Project (at: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=13707).

28 Theodore Roosevelt, American Ideals, The Strenuous Life, Realizable Ideals (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926), pp. 498-499.

29 Noah Webster, Dictionary (1828), s. v. “conscience.”

30 Noah Webster, Dictionary (1828), s. v. “conscience.”

31 Menno Simon, The Complete Works of Menno Simon (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Library, 2005), p. 118, “A Brief Complaint or Apology of the Despised Christians and Exiled Strangers,” (at: https://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa;cc=moa;rgn=main;view=text;idno=AGV9043.0002.001); or (at: https://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=moa;cc=moa;idno=AGV9043.0002.001;seq=118).

32 “The Works of James Arminius: Vol. 2, Disputation LVI on the Power of the Church in Enacting Laws,” Christian Classics Ethereal Library (at: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/arminius/works2.txt) (accessed on March 12, 2009).

33 John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1989), Book 3: Chapter 19, §14, p. 140, Book IV, Chapter 10, Sec. 5, pp. 416-417 (at: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes.txt).

34 John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration (York: Wilson, Spence and Mawman, 1788), pp. 17-25, 31-33, 45, 55, 65-69, 89, 91, 93, John Locke, “A Letter Concerning Toleration,” The Founders Constitution (at: https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendI_religions10.html) (accessed on March 17, 2009). See also Baron de Montesquieu, “Spirit of Laws,” The Founders Constitution, Bk. 12, Chs. 4, 5, 1748 (at: https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendI_religions12.html).

35 “Plantation Agreement at Providence,” The Avalon Project, August 27 – September 6, 1640 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ri01.asp).

36 William MacDonald, Select Charters and Other Documents Illustrative of American History 1606-1775 (New York: MacMillan Company, 1899), p. 104-106, “Maryland Toleration Act,” April, 1649.

37 The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters and Other Organic Laws, Francis Newton Thorpe, editor (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), Vol. VI, p. 3211, “Charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations-1663.”

38 “The Concession and Agreement of the Lords Proprietors of the Province of New Caesarea, or New Jersey,” The Avalon Project, 1664 (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nj02.asp).

39 “Charter of Carolina,” June 30, 1665, The Avalon Project (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc04.asp).

40 “Fundamental Constitution of Carolina,” March 1, 1669, The Avalon Project, (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc05.asp).

41 “The Charter or Fundamental Laws of West New Jersey,” 1676, The Avalon Project (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nj05.asp).

42 “Frame of Government of Pennsylvania,” May 5, 1682, The Avalon Project (at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/pa04.asp).

43 “Charter of Delaware,” October 28, 1701, University of Maryland (at: https://www.stateconstitutions.umd.edu/Thorpe/display.aspx?ID=119).

44 Roscoe Pound, The Spirit of the Common Law (Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1921), p. 42.

45 Updegraph v. The Commonwealth, 11 S. & R. 394 (Sup. Ct. Pa. 1824).

46 The American’s Guide: Comprising the Declaration of Independence; the Articles of Confederation; the Constitution of the United States, and the Constitutions of the Several States Composing the Union (Philadelphia: Hogan & Thompson, 1845), p. 180, Virginia, June 12, 1776, Art. XVI, “Bill of Rights.”

47 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), p. 91, Delaware, September 10, 1776, Art. 2, “A Declaration of Rights and Fundamental Rules of the Delaware State.”

48 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), p. 132, North Carolina, December 18, 1776, Art. 19, “A Declaration of Rights.”

49 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), p. 77, Pennsylvania, September 28, 1776, Ch. 1, Art. 2, “A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the State of Pennsylvania.”

50 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), p. 73, New Jersey, July 2, 1776, Art. XVIII, “Constitution of New Jersey.”

51 The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws, Francis Newton Thorpe, editor (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), Vol. VI, p. 3740, Vermont, July 8, 1777, Ch. 1, Art. III, “A Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the State of Vermont.”

52 The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), p. 67, New York, April 20, 1777, Art. 38, “Constitution of New York.”

53 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), pp. 152-154, South Carolina, March 19, 1778, Art. 38, “Constitution of the State of South Carolina.”

54 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), p. 6, Massachusetts, March 2, 1780, Part 1, Art. II, “A Declaration of Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.”

55 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), pp. 3-4, New Hampshire, June, 1784, Part 1, Art. 1, No. 5, “The Bill of Rights.”

56 B. F. Morris, Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, Developed in the Official and Historical Annals of the Republic (Philadelphia: George W. Childs, 1864) pp. 162-163.

57 B. F. Morris, Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, Developed in the Official and Historical Annals of the Republic (Philadelphia: George W. Childs, 1864), p. 152.

58 Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Andrew A. Lipscomb, editor (Washington, D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XVI, p. 332, letter to the Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church at New London, CT, February 4, 1809.

59 Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Philadelphia: Matthew Carey, 1794), Query XVII, p. 213.

60 Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Julian P. Boyd, editor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953), Vol. VIII, p. 260, letter to Katherine Sprowle Douglas, July 5, 1785.

61 Thomas Jefferson, Papers (1951), Vol. IV, p. 404, “Proclamation Concerning Paroles,” January 19, 1781.

62 James Madison, The Writings of James Madison, Gaillard Hunt, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1906), Vol. VI, p. 102, “Property,” from the National Gazette, March 29, 1792.

63 United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163 (1965).

64 West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943).

65 Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972).

66 See, for example, “Some parents falsely claim religious objections to child vaccines,” Associated Press, October 27, 2007.

67 Potter v. District of Columbia, Civil Action No. 01-1189 (D.D.C. Sept. 28, 2007).

68 Hobbie v. Unemployment Appeals Commission of Florida, 480 U.S. 136 (1987); Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 409 (1963).

69 42 U.S.C. § 300a-7.

70 See, Federal Register: December 19, 2008 (Volume 73, Number 245), Rules and Regulations, Pages 78071-78101, from the Federal Register Online via GPO Access, DOCID:fr19de08-20, Page 78071, Part VI, Department of Health and Human Services. A series of acts from 1970-2004 were passed on this issue, including the Public Health Service Act of 1996, and the Weldon Act of 2004. See also “Testimony Re: Abortion Non-Discrimination Act: The Committee on Energy and Commerce,” The Protection of Conscience Project, July 11, 2002.

71 See, for example, 42 U.S.C. § 300a-7(b) (prohibiting public discrimination against individuals and entities that object to performing abortions on the basis of religious beliefs or moral convictions); 42 U.S.C. § 300a-7(c) (prohibiting entities from discriminating against physicians and health care personnel who object to performing abortions on the basis of religious beliefs or moral convictions); 42 U.S.C. § 300a-7(e) (prohibiting entities from discriminating against applicants who object to participating in abortions on the basis of religious beliefs or moral convictions); 42 U.S.C. § 238n (prohibiting discrimination against individuals and entities that refuse to perform abortions or train in their performance); 20 U.S.C. § 1688 (ensuring that federal sex discrimination standards do not require educational institutions to provide or pay for abortions or abortion benefits).

72 See, for example, 42 U.S.C. § 300a-7(b) (prohibiting public discrimination against individuals and entities that object to performing sterilizations on the basis of religious beliefs or moral convictions); 42 U.S.C. § 300a-7(c) (prohibiting entities from discriminating against physicians and health care personnel who object to performing sterilizations on the basis of religious beliefs or moral convictions); 42 U.S.C. § 300a-7(e) (prohibiting entities from discriminating against applicants who object to participating in sterilizations on the basis of religious beliefs or moral convictions).

73 See, for example, Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act, 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-67, § 641, 115 Stat. 514, 554-5 (prohibiting health plans participating in the federal employee health benefits program from discriminating against individuals who, for religious or moral reasons, refuse to prescribe or otherwise provide for contraceptives, and protecting the right of health plans that have religious objections to contraceptives to participate in the program).

74 See, for example, 18 U.S.C. § 3597(b) (providing that no state correctional employee or federal prosecutor shall be required, as a condition of employment or contractual obligation, to participate in any federal death penalty case or execution if contrary to his or her moral or religious convictions).

75 Rob Stein, “Rule Shields Health Workers Who Withhold Care Based on Beliefs,” Washington Post, December 19, 2008, Page A10 (at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/12/18/AR2008121801556.html).

76 “News Release: HHS Issues Final Regulation to Protect Health Care Providers from Discrimination,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, December 18, 2008.

77 “S. 20: To Prohibit the Implementation or Enforcement of Certain Regulations,” Thomas, November 20, 2008. See also “Senators Clinton and Murray Introduce Legislation to Stop New HHS Rule that Would Undermine Women’s Health Care,” United States Senate, November 20, 2008.

78 “ACLU Files Lawsuit Against Conscience Protection Rules,” Catholic News Agency, January 17, 2009.

79 “Health Workers ‘Conscience’ Rule Set to Be Voided,” The Washington Post, February 28, 2009, A01 (at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/02/27/AR2009022701104.html).

80 Josiah Ryan, “U. S. Senator Says He Would Practice Civil Disobedience If Obama Repeals Abortion ‘Conscience Clause’,” CNSNews, March 2, 2009.

* This article concerns a historical issue and may not have updated information.

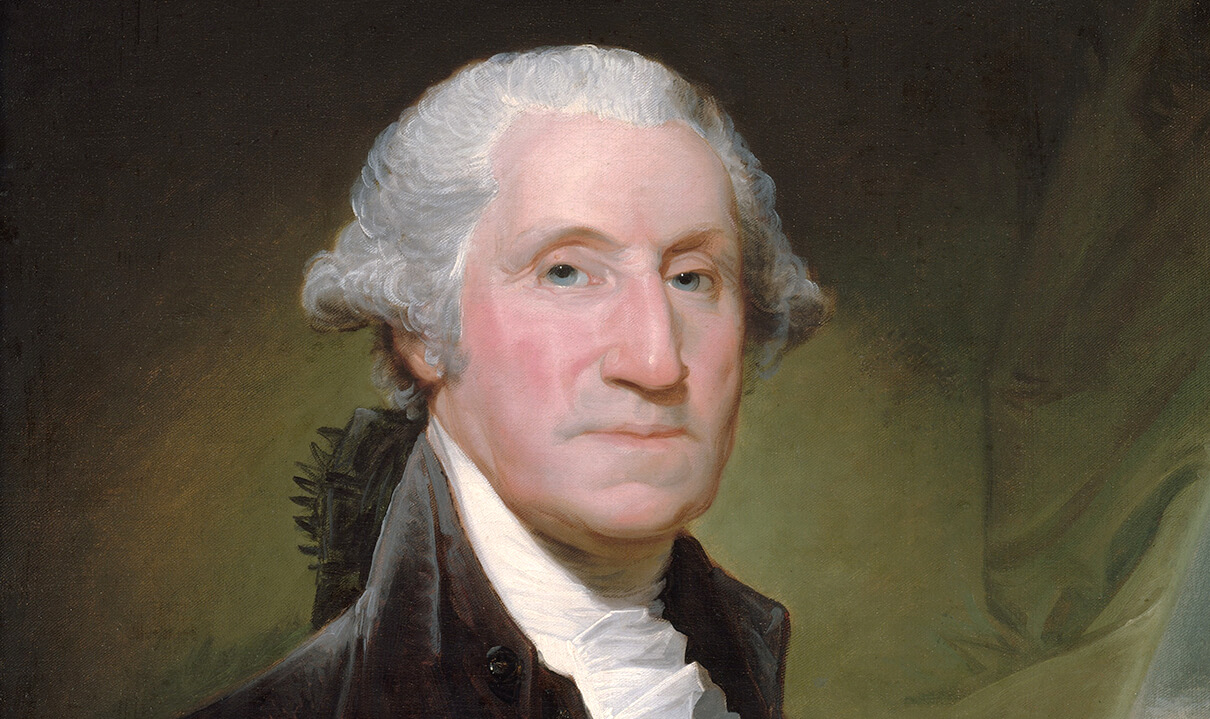

On receiving this news, Washington departed from Mt. Vernon and began his trek toward New York City, stopping first at Fredericksburg, Virginia, to visit his mother, Mary¬ – the last time the two would see each other. Mary was eighty-two and suffering from incurable breast cancer. Mary parted with her son, giving him her blessings and offering him her prayers, telling him: “You will see me no more; my great age and the disease which is rapidly approaching my vitals, warn me that I shall not be long in this world. Go, George; fulfill the high destinies which Heaven appears to assign to you; go, my son, and may that Heaven’s and your mother’s blessing be with you always.”

On receiving this news, Washington departed from Mt. Vernon and began his trek toward New York City, stopping first at Fredericksburg, Virginia, to visit his mother, Mary¬ – the last time the two would see each other. Mary was eighty-two and suffering from incurable breast cancer. Mary parted with her son, giving him her blessings and offering him her prayers, telling him: “You will see me no more; my great age and the disease which is rapidly approaching my vitals, warn me that I shall not be long in this world. Go, George; fulfill the high destinies which Heaven appears to assign to you; go, my son, and may that Heaven’s and your mother’s blessing be with you always.”