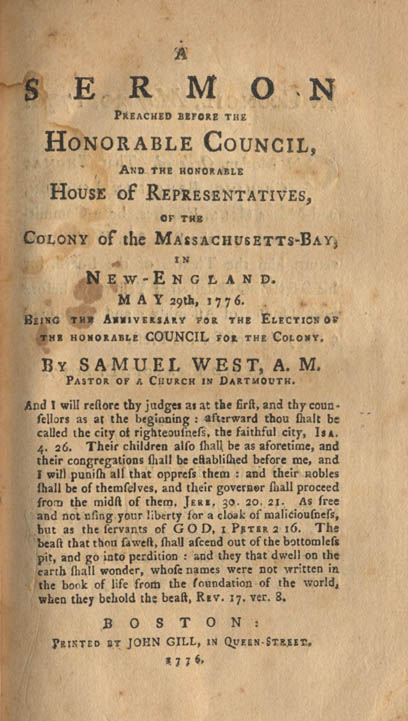

Samuel West (1730-1807) graduated from Harvard in 1754. He was pastor of a church in New Bedford, MA in 1761. He served as a chaplain during the Revolutionary War, joining just after the Battle of Bunker Hill. West was a member of the Massachusetts state constitutional convention, and a member of the Massachusetts convention that adopted the U.S. Constitution. The following election sermon was preached by West in Massachusetts on May 29, 1776.

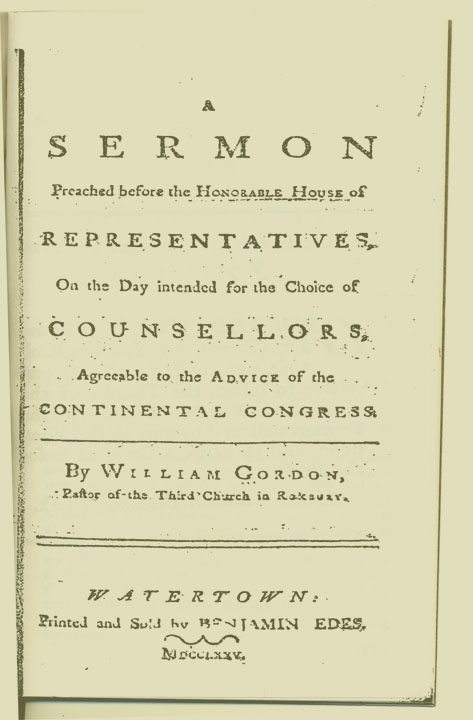

SERMON

PREACHED BEFORE THE

HONORABLE COUNCIL,

AND THE HONORABLE

House of Representatives,

OF THE

Colony of the Massachusetts-Bay,

IN

New-England

MAY 29th, 1776.

Being the Anniversary for the Election of

the honorable COUNCIL for the Colony.

By SAMUEL WEST, A. M.

Pastor of a Church in Dartmouth.

And I will restore thy judges as the first, and thy counselors as at the beginning: afterward thou shalt be called the city of righteousness, the faithful city, Isa. 4. 26. Their children also shall be as aforetime, and their congregations shall be established before me, and I will punish all that oppress them: and their nobles shall be of themselves, and their governor shall proceed from the midst of them. Jere. 30. 20. 21. As free and not using your liberty for a cloak of maliciousness, but as the servants of GOD, I Peter 2. 16. The beast that thou sawest, shall ascend out of the bottomless pit, and go into perdition: and they that dwell on the earth shall wonder, whose names were not written in the book of life from the foundation of the world, when they behold the beast, Rev. 17. Ver. 8.

IN COUNCIL, May 30, 1776.

On Motion, Ordered, That Thomas Cushing, Benjamin Lincoln, and Moses Gill, Esquires, be a Committee to wait on the Rev. Mr. WEST, and return him the Thanks of the Board, for his SERMON delivered Yesterday, before both Houses of Assembly; and to request a Copy thereof for the Press.

Perez Morton, D. Secr’y.

ADVERTISEMENT.

I would inform the reader that several passages which were omitted, when the Sermon was delivered, for fear of being tedious to the assembly, are now inserted at the desire of several of the hearers.

Election-Sermon.

Put them in mind to be subject to principalities and powers, to obey magistrates, to be ready to every good work.

THE great Creator having design’d the human race for society, has made us dependent on one another for happiness; he has so constituted us, that it becomes both our duty and interest, to seek the public good. And that we may be the more firmly engaged to promote each others welfare, the Deity has endowed us with tender and social affections, with generous and benevolent principles: Hence the pain, that we feel in seeing an object of distress: Hence the satisfaction, that arises in relieving the afflicted, and the superior pleasure, which we experience in communicating happiness to the miserable. The Deity ha also invested us with moral powers and faculties, by which we are enabled to discern the difference between right and wrong, truth and falsehood, good and evil: Hence the approbation of mind, that arises upon doing a good action, and the remorse of conscience, which we experience, when we counteract the moral sense, and do that which is evil. This proves, that in what is commonly called a state of nature, we are the subjects of the divine law and government, that the Deity is our supreme magistrate, who has written his law in our hearts, and will reward, or punish us, according as we obey or disobey his commands. Had the human race uniformly persevered in a state of moral rectitude, there would have been little, or no need of any other law, besides that which is written in the heart; for everyone in such a state would be a law unto himself. There would be no occasion for enacting or enforcing of penal laws, for such are not made for the righteous man, but for the lawless and disobedient, for the ungodly, and for sinners, for the unholy and profane, for murderers of fathers, and murderers of mothers, for manslayers, for whoremongers, for them that defile themselves with mankind, for men-stealers, for liars, for perjured persons, and if there be any other thing, that is contrary to moral rectitude, and the happiness of mankind. The necessity of forming ourselves into politic bodies, and granting to our rulers, a power to enact laws for the public safety, and to enforce them by proper penalties arises from our being in a fallen, and degenerate estate: The slightest view of the present state and condition of the human race, is abundantly sufficient to convince any person of common sense, and common honesty, that civil government is absolutely necessary for the peace and safety of mankind, and consequently that all good magistrates, while they faithfully discharge the trust reposed in them, ought to be religiously and conscientiously obeyed. An enemy to good government is an enemy not only to his country, but to all mankind; for he plainly shews himself to be divested of those tender and social sentiments, which are characteristic of an human temper, even of that generous and benevolent disposition, which is the peculiar glory of a rational creature. An enemy to good government has degraded himself below the rank and dignity of a man, and deserves to be classed with the lower creation. Hence we find, that wise and good men of all nations, and religions, have ever inculcated subjection to good government, and have born their testimony against the licentious disturbers of the public peace.

Nor has Christianity been deficient in this capital point. We find our blessed Saviour directing the Jews to render to Caesar the things that were Caesar’s: And the apostles and first preachers of the gospel not only exhibited a good example of subjection to the magistrate, in all things that were just and lawful, but they have also in several places of the new-testament, strongly enjoined upon Christians the duty of submission to that government under which providence had placed them. Hence we find, that those, who despise government, and are not afraid to speak evil of dignities, are by the apostles Peter and Jude, clas’d among those presumptuous self-willed sinners, that are reserv’d to the judgment of the great day. And the apostle Paul judg’d submission to civil government, to be a matter of such great importance, that he tho’t it worth his while to charge Titus, to put his hearers in mind to be subject to principalities and powers, to obey magistrates, to be ready to every good work. As much as to say, none can be ready to every good work, or be properly dispose’d to perform those actions, that tend to promote the public good, who do not obey magistrates, and who do not become good subjects of civil government. If then obedience to the civil magistrates is so essential to the character of a Christian, that without it he cannot be disposed to perform those good works, that are necessary for the welfare of mankind; if the despisers of government are those presumptuous, self-willed sinners, who are reserv’d to the judgment of the great day; it is certainly a matter of the utmost importance to us all, to be thoroughly acquainted with the nature and extent of our duty, that we may yield the obedience requir’d; for it is impossible that we should properly discharge a duty when we are strangers to the nature and extent of it.

In order therefore, that we may form a right judgment of the duty enjoin’d in our text, I shall consider the nature and design of civil government, and shall shew, that the same principles which oblige us to submit to government, do equally oblige us to submit to government, do equally oblige us to resist tyranny; or that tyranny and magistracy are so opposite to each other, that where the one begins, the other ends. I shall then apply the present discourse to the grand controversy, that at this day subsists between Great-Britain and the American colonies.

That we may understand the nature and design of civil government, and discover the foundation of the magistrates authority to command, and the duty of subjects to obey, it is necessary to derive civil government from its original; in order to which we must consider what “state all men are naturally in, and that is as (Mr. Lock observes) a state of perfect freedom to order all their actions, and dispose of their possessions, and persons as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any man”. It is a state wherein all are equal, no one having a right to control another, or oppose him in what he does, unless it be in his own defence, or in the defence of those that being injured stand in need of his assistance.

Had men persevered in a state of moral rectitude, everyone would have been disposed to follow the law of nature, and pursue the general good; in such a state, the wisest and most experienced would undoubtedly be chosen to guide and direct those of less wisdom and experience than themselves; there being nothing else that could afford the least shew or appearance of anyone’s having the superiority or precedency over another; for the dictates of conscience, and the precepts of natural law being uniformly and regularly obey’d, men would only need to be informed what things were most fit and prudent to be done in those cases, where their inexperience, or want of acquaintance, left their minds in doubt what was the wisest and most regular method for them to pursue. In such cases it would be necessary for them to advise with those, who were wiser and more experienced than themselves. But these advisers could claim no authority to compel, or to use any forcible measures to oblige anyone to comply with their direction, or advice; there could be no occasion for the exertion of such a power; for every man being under the government of right reason, would immediately feel himself constrain’d to comply with everything that appeared reasonable or fit to be done, or that would any way tend to promote the general good. This would have been the happy state of mankind, had they closely adhered to the law of nature, and persevered in their primitive state.

Thus we see, that a state of nature, tho’ it be a state of perfect freedom, yet it is very far from a state of licentiousness; the law of nature gives men no right to do anything that is immoral, or contrary to the will of God, and injurious to their fellow creatures; for a state of nature is properly a state of law and government, founded upon the unchangeable nature of the Deity, and a law resulting from the eternal fitness of things; sooner shall heaven and earth pass away, and the whole frame of nature be dissolved, than any part, even the smallest iota of this law shall ever be abrogated; it is unchangeable as the Deity himself, being a transcript of his moral perfections. A revelation pretending to be from God, that contradicts any part of natural law, ought immediately to be rejected as an imposture; for the Deity cannot make a law contrary to the law of nature, without acting contrary to himself. A thing in the strictest sense impossible, for that which implies a contradiction is not an object of the divine power. Had this stood, the world had remained free from a multitude of absur’d and pernicious principles, which have been industriously propagated by artful and designing men, both in politicks and divinity. The doctrine of non-resistance, and unlimited passive obedience to the worst of tyrants, could never have found credit among mankind, had the voice of reason been hearkened to for a guide, because such a doctrine would immediately have been discerned to be contrary to natural law.

In a state of nature we have a right to make the persons that hae injured us, repair the damages that they have done us; and it is just in us to inflict such punishment upon them, as are necessary to restrain them from doing the like for the future: The whole end and design of punishing being either to reclaim the individual punished, or to deter others from being guilty of similar crimes: Whenever punishment exceeds these bounds, it becomes cruelty and revenge, and directly contrary to the law of nature. Our wants and necessities being such, as to render it impossible in most cases to enjoy life in any tolerable degree, without entering into society, and there being innumerable cases, wherein we need the assistance of others, which if not afforded, we should very soon perish; hence the law of nature requires, that we should endeavour to help one another, to the utmost of our power in all cases, where our assistance is necessary. It is our duty to endeavour always to promote the general good; to do to all, as we would be willing to be done by, were we in their circumstances, to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly before God. These are some of the laws of nature, which every man in the world is bound to observe, and which whoever violates, exposes himself to the resentment of mankind, the lashes of his own conscience, and the judgment of heaven. This plainly shews, that the highest state of liberty subjects us to the law of nature, and the government of God. The most perfect freedom consists in obeying the dictates of right reason, and submitting to natural law. When a man goes beyond, or contrary to the law of nature and reason, he becomes the slave of base passions, and vile lusts, he introduces confusion and disorder into society, and brings misery and destruction upon himself. This therefore cannot be called a state of freedom, but a state of the vilest slavery, and the most dreadful bondage: The servants of sin and corruption are subjected to the worst kind of tyranny in the universe. Hence we conclude, that where licentiousness begins, liberty ends.

The law of nature is a perfect standard and measure of action for beings that persevere in a state of moral rectitude. But the case is far different with us, who are in a fallen and degenerate estate. We have a law in our members, which is continually warring against the law of the mind; by which we often become enslaved to the basest lusts, and are brought into bondage to the vilest passions. The strong propensities of our animal nature often overcome the sober dictates of reason and conscience, and betray us into actions injurious to the public, and destructive of the safety and happiness of society. Men of unbridled lusts, were they not restrain’d by the power of the civil magistrate, would spread horror and desolation all around them. This makes it absolutely necessary, that societies should form themselves into politick bodies, that they may enact laws for the public safety, and appoint particular penalties for the violation of their laws, and invest a suitable number of persons with authority to put in execution and enforce the laws of the state; in order that wicked men may be restrained from doing mischief to their fellow creatures, that the injured may have their rights restored to them, that the virtuous may be encouraged in doing good; and that every member of society may be protected and secured in the peaceable, quiet possession and enjoyment of all those liberties and privileges, which the Deity has bestowed upon him, i.e. that he may safely enjoy, and pursue whatever he chooses, that is consistent with the publick good. This shews that the end and design of civil government, cannot be to deprive men of their liberty, or take away their freedom; but on the contrary the rue design of civil government is to protect men in the enjoyment of liberty.

From hence it follows, that tyranny and arbitrary power are utterly inconsistent with, and subversive of the very end and design of civil government, and directly contrary to natural law, which is the true foundation of civil government and all politick law: Consequently the authority of a tyrant is of itself null and void; for as no man can have a right to act contrary to the law of nature, it is impossible that any individual, or even the greatest number of men, can confer a right upon another, of which they themselves are not possessed, i.e. no body of men can justly and lawfully authorize any person to tyrannize over, and enslave his fellow creatures, or to do anything contrary to equity and goodness. As magistrates have no authority, but what they derive from the people, whenever they act contrary to the public good, and pursue measures destructive of the peace and safety of the community, they forfeit their right to govern the people. Civil rulers and magistrates are properly of human creation; they are set up by the people to be the guardians of their rights, and to secure their persons from being injured, or oppressed; the safety of the publick being the supreme law of the state, by which the magistrates are to be governed, and which they are to consult upon all occasions. The modes of administration may be very different, and the forms of government may vary from each other in different ages and nations; but under every form, the end of civil government is the same and cannot vary: It is like the laws of the Medes and Persians, it altereth not.

Though magistrates are to consider themselves as the servants of the people, seeing from them it is, that they derive their power and authority; yet they may also be considered as the ministers of God ordain’d by him for the good of mankind: For under him as the supreme magistrate of the universe they are to act; and it is God who has not only declared in his word, what are the necessary qualifications of a ruler, but who also raises up and qualifies men for such an important station. The magistrate may also in a more strict and proper sense, be said to be ordained of God, because reason, which is the voice of God plainly requires such an order of men to be appointed for the public good; now whatever right reason requires as necessary to be done, is as much the will and law of God, as tho’ it were enjoin’d us by an immediate revelation from heaven, or commanded in the sacred scriptures.

From this account of the origin, nature and design of civil government, we may be very easily led into a thorough knowledge of our duty; we may see the reason, why we are bound to obey magistrates, viz. because they are the ministers of God for good unto the people. While therefore they rule in the fear of God, and while they promote the welfare of the state, i.e. while they act in the character of magistrates, it is the indispensible duty of all to submit to them, and to oppose a turbulent, factious and libertine spirit, whenever and wherever it discovers itself. When a people have by their free consent confer’d upon a number of men, a power to rule and govern them, they are bound to obey them: Hence disobedience becomes a breach of faith, it is violating a constitution of their own appointing, and breaking a compact for which they ought to have the most sacred regard: Such a conduct discovers so base and disingenuous a temper of mind, that it must expose them to contempt in the judgment of all the sober thinking part of mankind. Subjects are bound to obey lawful magistrates by every tender tie of human nature, which disposes us to consult the public good, and to seek the good of our brethren, our wives, our children, our friends and acquaintance; for he that opposes lawful authority, does really oppose the safety and happiness of his fellow creatures. A factious, seditious person, that opposes good government, is a monster in nature, for he is an enemy to his own species, and destitute of the sentiments of humanity.

Subjects are also bound to obey magistrates for conscience sake, out of regard to the divine authority, and out of obedience to the will of God: For if magistrates are the ministers of God, we cannot disobey them without being disobedient to the law of God; and this extends to all men in authority, from the highest ruler to the lowest officer in the state. To oppose them when in the exercise of lawful authority, is an act of disobedience to the Deity, and as such will be punished by him. It will doubtless be readily granted by every honest man, that we ought cheerfully to obey the magistrate and submit to all such regulations of government, as tend to promote the publick good; but as this general definition may be liable to be misconstrued, and every man may think himself at liberty to disregard any laws that do not suit his interest, humor, or fancy; I would observe, that in a multitude of cases, many of us, for want of being properly acquainted with affairs of state, may be very improper judges of particular laws, whether they are just or not: In such cases it becomes us, as good members of society, peaceably and conscientiously to submit, tho’ we cannot see the reasonableness of every law to which we submit; and that for this plain reason, that if any number of men should take it upon them to oppose authority for acts, which may be really necessary for the public safety, only because they do not see the reasonableness of them, the direct consequence will be introducing confusion and anarchy into the state.

It is also necessary, that the minor part should submit to the major; e.g. when legislators have enacted a set of laws, which are highly approved by a large majority of the community, as tending to promote the publick good, in this case, if a small number of persons are so unhappy as to view the matter in a very different point of light from the public, tho’ they have an undoubted right to shew the reasons of their dissent from the judgment of the publick, and may lawfully use all proper arguments to convince the publick of what they judge to be an error, yet if they fail in their attempt, and the majority still continue to approve of the laws that are enacted, it is the duty of those few that dissent, peaceably and for conscience sake to submit to the publick judgment; unless something is required of them which they judge would be sinful for them to comply with; for in that case they ought to obey the dictates of their own consciences, rather than any human authority whatever. Perhaps also some cases of intolerable oppression, where compliance would bring on inevitable ruin and destruction, may justly warrant the few to refuse submission to what they judge inconsistent with their peace and safety; for the law of self-preservation will always justify opposing a cruel and tyrannical imposition, except where opposition is attended with greater evils than submission, which is frequently the case where a few are oppressed by a large and powerful majority.1 Except the above-named cases, the minor ought always to submit to the major; otherwise there can be no peace nor harmony in society. And besides, it is the major part of a community that have the sole right of establishing a constitution, and authorizing magistrates; and consequently it is only the major part of the community that can claim the right of altering the constitution, and displacing the magistrates; for certainly common sense will tell us, that it requires as great an authority to set aside a constitution, as there was at first to establish it. The collective body, not a few individuals, ought to constitute the supreme authority of the state.

The only difficulty remaining is to determine, when a people may claim a right of forming themselves into a body politick, and may assume the powers of legislation. In order to determine this point, we are to remember, that all men being by nature equal, all the members of a community have a natural right to assemble themselves together, and to act and vote for such regulations, as they judge are necessary for the good of the whole. But when a community is become very numerous, it is very difficult, and in many cases impossible for all to meet together to regulate the affairs of the state: Hence comes the necessity of appointing delegates to represent the people in a general assembly. And this ought to be look’d upon as a sacred and unalienable right, of which a people cannot justly divest themselves, and which no human authority can in equity ever take from them, viz. that no one be obliged to submit to any law, except such as are made either by himself, or by his representative.

If representation and legislation are inseparably connected, it follows, that when great numbers have emigrated into a foreign land, and are so far removed from the parent state, that they neither are or can be properly represented by the government from which they have emigrated, that then nature itself points out the necessity of their assuming to themselves the powers of legislation, and they have a right to consider themselves as a separate state from the other, and as such to form themselves into a body politick.

In the next place,

When a people find themselves cruelly oppressed by the parent state, they have an undoubted right to throw off the yoke, and to assert their liberty, if they find good reason to judge that they have sufficient power and strength to maintain their ground in defending their just rights against their oppressors: For in this case by the law of self preservation, which is the first law of nature, they have not only an undoubted right, but it is their indispensible duty, if they cannot be redressed any other way, to renounce all submission to the government that has oppressed them, and set up an independent state of their own; even tho’ they may be vastly inferior in number to the state that has oppres’d them. When either of the aforesaid cases takes place, and more especially when both concur, no rational man (I imagine,) can have any doubt in his own mind, whether such a people have a right to form themselves into a body politick, and assume to themselves all the powers of a free state. For can it be rational to suppose, that a people should be subjected to the tyranny of a set of men, who are perfect strangers to them, and cannot be supposed to have that fellow feeling for them, that we generally have for those with whom we are connected and acquainted; and besides, thro’ their unacquaintedness with the circumstances of the people over whom they claim the right of jurisdiction, are utterly unable to judge in a multitude of cases, what is best for them.

It becomes me not to say, what particular form of government is best for a community, whether a pure democracy, aristocracy, monarchy, or a mixture of all the three simple forms. They all have their advantages & disadvantages; and when they are properly administered, may any of them answer the design of civil government tolerably well. Permit me however to say, that an unlimited absolute monarchy, and an aristocracy not subject to the control of the people, are two of the most exceptionable forms of government.

1st. Because in neither of them is there a proper representation of the people, and,

2dly. Because each of them being entirely independent of the people, they are very apt to degenerate into tyranny. However, in this imperfect state, we cannot expect to have government formed upon such a basis, but that it may be perverted by bad men to evil purposes. A wise and good man would be very loth to undermine a constitution, that was once fixed and established, altho’ he might discover many imperfections in it; and nothing short of the most urgent necessity would ever induce him to consent to it; because the unhinging a people from a form of government to which they had been long accustomed, might throw them into such a state of anarchy and confusion as might terminate in their destruction, or perhaps in the end subject them to the worst kind of tyranny.

Having thus shewn the nature, end and design of civil government, and pointed out the reasons, why subjects are bound to obey magistrates, viz. because in so doing, they both consult their own happiness as individuals, and also promote the public good, and the safety of the state: I proceed,

In the next place to shew, That the same principles that oblige us to submit to civil government, do also equally oblige us, where we have power and ability, to resist and oppose tyranny, and that where tyranny begins, government ends. For if magistrates have no authority but what they derive from the people, if they are properly of human creation; if the whole end and design of their institution is to promote the general good, and to secure to men their just rights, it will follow, that when they act contrary to the end and design of their creation, they cease being magistrates, and the people, which gave them their authority, have a right to take it from them again. This is a very plain dictate of common sense, which universally obtains in all similar cases: for who is there, that having employ’d a number of men to do a particular piece of work for him, but what would judge that he had a right to dismiss them from his service, when he found, that they went directly contrary to his orders; and that instead of accomplishing the business he had set them about, they would infallibly ruin and destroy it. If then men in the common affairs of life always judge, that they have a right to dismiss from their service such persons as counteract their plans and designs, tho the damage will affect only a few individuals, much more must the body politick have a right to depose any persons tho’ appointed to the highest place of power and authority, when they find, that they re unfaithful to the trust reposed in them, and that instead of consulting the general good, they are disturbing the peace of society by making laws cruel and oppressive, and by depriving the subjects of their just rights and privileges. Whoever pretends to deny this proposition, must give up all pretence of being master of that common sense and reason by which the Deity has distinguished us from the brutal herd.

As our duty of obedience to the magistrate is founded upon our obligation to promote the general good, our readiness to obey lawful authority will always arise in proportion to the love and regard that we have for the welfare of the publick; and the same love and regard for the publick will inspire us with as strong a zeal to oppose tyranny, as we have to obey magistracy. Our obligation to promote the public good extends as much to the opposing every exertion of arbitrary power, that is injurious to the State, as it does to the submitting to good and wholesome laws. No man therefore can be a good member of the community, that is not as zealous to oppose tyranny, as he is ready to obey magistracy. A slavish submission to tyranny is a proof of a very sordid and base mind: Such a person cannot be under the influence of any generous human sentiments, nor have a tender regard for mankind.

Further, if magistrates are no farther ministers of God, than they promote the general good of the community, then obedience to them neither is, nor can be unlimited; for it would imply a gross absurdity to assert, that, when magistrates are ordained by the people solely for the purpose of being beneficial to the state, they must be obeyed, when they are seeking to ruin and destroy it. This would imply, that men were bound to act against the great law of self-preservation, and to contribute their assistance to their own ruin and destruction, in order that they may please and gratify the greatest monsters in nature, who are violating the laws of God, and destroying the rights of mankind. Unlimited submission and obedience is due to none but God alone: He has an absolute right to command: He alone has an uncontroulable sovereignty over us, because he alone is unchangeably good: He never will, nor can require of us consistent with his nature and attributes, anything that is not fit and reasonable; his commands are all just and good: And to suppose that he has given to any particular set of men a power to require obedience to that, which is unreasonable, cruel and unjust, is robbing the Deity of his justice and goodness, in which consists the peculiar glory of the divine character; and it is representing him, under the horrid character of a tyrant.

If magistrates are ministers of God only because the law of God and reason points out the necessity of such an institution for the good of mankind; it follows that whenever they pursue measures directly destructive of the publick good, they cease being God’s ministers; they forfeit their right to obedience from the subject, they become the pests of society; and the community is under the strongest obligation of duty both to God and to its own members to resist and oppose them, which will be so far from resisting the ordinance of God, that it will be strictly obeying his commands. To suppose otherwise, will imply, that the Deity requires of us an obedience, that is self-contradictory and absurd, and that one part of his law is directly contrary to the other, i.e. while he commands us to pursue virtue, and the general good, he does at the same time require us to persecute virtue, and betray the general good by enjoyning us obedience to the wicked commands of tyrannical oppressors. Can anyone not loft to the principles of humanity undertake to defend such absurd sentiments as these? As the public safety is the first and grand law of society, so no community can have a right to invest the magistrate with any power, or authority that will enable him to act against the welfare of the state, and the good of the whole. If men have at any time wickedly, and foolishly given up their just rights into the hands of the magistrate, such acts are null and void of course; to suppose otherwise will imply, that we have a right to invest the magistrate with a power to act contrary to the law of God, which is as much as to say, that we are not the subjects of divine law and government. What has been said, is (I apprehend) abundantly sufficient to shew that tyrants are no magistrates, or that whenever magistrates abuse their power and authority, to the subverting the publick happiness, their authority immediately ceases, and that it not only becomes lawful, but an indispensable duty to oppose them: That the principle of self-preservation, the affection, and duty, that we owe to our country, and the obedience we owe the Deity, do all require us to oppose tyranny.

If it be asked, who are the proper judges to determine, when rulers are guilty of tyranny and oppression? I answer, the publick; not a few disaffected individuals, but the collective body of the state must decide this question; for as it is the collective body that invests rulers with their power and authority, so it is the collective body that has the sole right of judging, whether rulers act up to the end of their institution or not. Great regard ought always to be paid to the judgment of the publick. It is true the publick may be imposed upon by a misrepresentation of facts; but this may be said of the publick, which can’t always be said of individuals, viz. that the publick is always willing to be rightly informed, and when it has proper matter of conviction laid before it, it’s judgment is always right.

This account of the nature and design of civil government, which is so clearly suggested to us by the plain principles of common sense and reason, is abundantly confirmed by the sacred scriptures, even by those very texts, which have been brought by men of slavish principles to establish the absurd doctrine, of unlimited passive obedience, and non-resistance: As will abundantly appear, by examining the two most noted texts, that are commonly bro’t to support the strange doctrine of passive obedience. The first that I shall cite, is in I Pet. 2d. c. ver. 13, 14. Submit yourselves to every ordinance of man, or rather as the words ought to be rendered from the Greek, submit yourselves to every human creation, or human constitution for the Lord’s sake, whether it be to the king as supreme, or unto governors, as unto them, that are sent by him for the punishment of evil doers, and for the praise of them, that do well. Here we4 see, that the apostle asserts, that magistracy is of human creation or appointment, that is, that magistrates have no power or authority, but what they derive from the people; that this power they are to exert for the punishment of evil doers, and for the praise of them that do well, i.e. the end and design of the appointment of magistrates, is to restrain wicked men by proper penalties from injuring society, and to encourage and honor the virtuous and obedient. Upon this account, Christians are to submit to them for the Lord’s sake, which is, as if he had said; tho’ magistrates are of mere human appointment, and can claim no power, or authority, but what they derive from the people, yet as they are ordained by men to promote the general good by punishing evil doers, and by rewarding and encouraging the virtuous and obedient, you ought to submit to them out of a sacred regard to the divine authority; for as they in the faithful discharge of their office do fulfill the will of God, so ye by submitting to them do fulfill the divine command. If the only reason assign’d by the apostle, why magistrates should be obey’d out of a regard to the divine authority, is because they punish the wicked and encourage the good: It follows, that when they punish the virtuous, and encourage the vicious, we have a right to refuse yielding any submission or obedience to them; i.e. whenever they act contrary to the end and design of their institution, they forfeit their authority to govern the people; and the reason for submitting to them out of regard to the divine authority immediately ceases; and they being only of human appointment, the authority which the people gave them, the publick have a right to take from them, and to confer it upon those who are more worthy. So far is this text from favouring arbitrary principles, that there is nothing in it, but what is consistent with, and favourable to the highest liberty, that any man can wish to enjoy; for this text requires us to submit to the magistrate no farther than he is the encourager and protector of virtue, and the punisher of vice; and this is consistent with all that liberty which the Deity has bestowed upon us.

The other text which I shall mention, and which has been made use of, by the favourers of arbitrary government, a their great sheet anchor and main support, is in Rom. 13th the first six verses. Let every soul be subject to the higher powers; for there is no power but of GOD: The powers that be are ordain’d of GOD. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of GOD; and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation: For rulers are not a terror to good works but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same. For he is the minister of GOD to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil be afraid, for he beareth not the sword in vain, for he is the minister of GOD, a revenger to execute wrath upon him, that doeth evil. Wherefore ye must needs be subject not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake. For, for this cause pay you tribute also; for they are God’s ministers attending continually upon this very thing. A very little attention (I apprehend) will be sufficient to shew, that this text is so far from favouring arbitrary government, that on the contrary, it strongly holds forth the principles of true liberty. Subjection to the higher powers is enjoined by the apostle, because there is no power but of God; the powers that be are ordained of God, consequently, to resist the power is to resist the ordinance of God: And he repeatedly declares that the ruler is the minister of God. Now before we can say, whether this text makes for, or against the doctrine of unlimited passive obedience, we must find out in what sense the apostle affirms, that magistracy is the ordinance of God, and what he intends when he calls the ruler the minister of God.

I can think but of three possible senses, in which magistracy can with any propriety be called God’s ordinance, or in which rulers can be said to be ordained of God as his ministers. The first is a plain declaration from the word of God, that such an one, and his descendants are, and shall be the only true and lawful magistrates; thus we find in scripture, the kingdom of Judah to be settled by divine appointment in the family of David. Or,

2dly, By an immediate commission from God, ordering and appointing such an one by name to be the ruler over the people; thus Saul and David were immediately appointed by God to be kings over Israel. Or,

3dly, Magistracy may be called the ordinance of God; and rulers may be called the ministers of God, because the nature and reason of things, which is the law of God requires such an institution for the preservation and safety of civil society. In the two first senses, the apostle cannot be supposed to affirm, that magistracy is God’s ordinance, for neither he, nor any of the sacred writers have entailed the magistracy to any one particular family under the gospel dispensation. Neither does he, nor any of the inspired writers give us the least hint, that any person should ever be immediately commissioned from God to bear rule over the people: The third sense then is the only sense, in which the apostle can be supposed to affirm, that the magistrate is the minister of God, and that magistracy is the ordinance of God, viz that the nature and reason of things, require such an institution for the preservation and safety of mankind. Now if this be the only sense in which the apostle affirms, that magistrates are ordained of God as his ministers, resistance must be criminal only so far forth, as they are ministers of God, i.e. while they act up to the end of their institution, and ceases being criminal, when they cease being the ministers of God, i.e. when they act contrary to the general good, and seek to destroy the liberties of the people.

That we have gotten the apostle’s sense of magistracy, being the ordinance of God, will plainly appear from the text itself: For after having asserted, that to resist the power is to resist the ordinance of God, and they that resist, shall receive to themselves damnation; he immediately adds, as the reason of this assertion, For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same: For he is the minister of GOD to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil be afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain: For he is the minister of GOD, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doth evil. Here is a plain declaration of the sense, in which he asserts, that the authority of the magistrate is ordained of God, viz. because rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil, therefore we ought to dread offending them, for we cannot offend them but by doing evil, and if we do evil, we have just reason to fear their power; for they bear not the sword in vain, but in this case, the magistrate is a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil: But if we are found doers of that which is good, we have no reason to fear the authority of the magistrate, for in this case, instead of being punished we shall be protected and encouraged: The reason why the magistrate is called the minister of God, is, because he is to protect, encourage and honor them that do well, and to punish them that do evil; therefore it is our duty to submit to them, not merely for fear of being punished by them, but out of regard to the divine authority, under which they are deputed to execute judgment, and to do justice. For this reason (according to the apostle) tribute is to be paid them, because as the ministers of God their whole business is to protect every man in the enjoyment of his just rights and privileges, and to punish every evil doer.

If the apostle then asserts, that rulers are ordain’d of God, only because they are a terror to evil works, and a praise to them that do well, if they are ministers of God only because they encourage virtue and punish vice; if for this reason only they are to be obey’d for conscience sake; if the sole reason, why they have a right to tribute is because they devote themselves wholly to the business of securing to men their just rights, and to the punishing of evil doers; it follows by undeniable consequence, that when they become the pests of human society; when they promote and encourage evil doers, and become a terror to good works, they then cease being the ordinance of God; they are so far from being the powers that are ordain’d of God, that they become the ministers of the powers of darkness: And it is so far from being a crime to resist them, that in many cases it may be highly criminal in the fight of heaven to refuse resisting and opposing them to the utmost of our power; or in other words, that the same reasons, that require us to obey the ordinance of God, do equally oblige us, when we have power and opportunity, to oppose and resist the ordinance of satan.

Hence, we see, that the apostle Paul instead of being a friend to tyranny and arbitrary government, turns out to be a strong advocate for the just rights of mankind; and is for our enjoying all that liberty, with which God has invested us: For no power (according to the apostle) is ordained of God, but what is an encourager of every good and virtuous action, do that which is good and thou shalt have praise of the same: No man need to be afraid of this power, which is ordain’d of God, who does nothing but what is agreeable to the law of God; for this power will not restrain us from exercising any liberty, which the Deity has granted us; for the minister of God is to restrain us from nothing, but the doing of that which is evil, and to this we have no right: To practice evil is not liberty, but licentiousness. Can we conceive of a more perfect, equitable and generous plan of government, than this which the apostle has laid down, viz. to have rulers appointed over us, to encourage us every to good and virtuous action, to defend and protect us in our just rights and privileges; and to grant us everything that can tend to promote out true interest and happiness; to restrain every licentious action, and to punish everyone that would injure or harm us; to become a terror to evil doers, to make and execute such just and righteous laws, as shall effectually deter and hinder men from the commission of evil; and to attend continually upon this very thing; to make it their constant care and study day and night to promote the good and welfare of the community, and to oppose all evil practices. Deservedly may such rulers be called the ministers of God for good. They carry on the same benevolent design towards the community which they great governor of the universe does towards his whole creation. Tis the indispensible duty of a people to pay tribute, and to afford an easy and comfortable subsistence to such rulers, because they are the ministers of God, who are continually laboring and employing their time for the good of the community. He that resists such magistrates, does in a very emphatical sense resist the ordinance of God; he is an enemy to mankind, odious to God, and justly incurs the sentence of condemnation from the great judge of quick and dead. Obedience to such magistrates is yielding obedience to the will of God; and therefore ought to be performed from a sacred regard to the divine authority.

For any one from hence to infer, that the apostle enjoins in this text unlimited obedience to the worst of tyrants, and that he pronounces damnation upon those that resist the arbitrary measures of such pests of society, is just as good sense, as if one should affirm, that because the scripture enjoins us obedience to all the laws of God, therefore we may not oppose the power of darkness, or because we are commanded to submit to the ordinance of God, therefore we may not resist the ministers of satan. Such wild work must be made with the apostle before he can be brought to speak the language of oppression. It is as plain (I think) as words can make it, that according to this text, no tyrant can be a ruler; for the apostle’s definition of a ruler is, that he is not a terror to good works, but to the evil; and that he is one who is to praise and encourage those that do well; whenever then the ruler encourages them that do evil, and is a terror to those that do well, i.e. as soon as he becomes a tyrant, he forfeits his authority to govern, and becomes the minister of satan, and as such ought to be opposed.

I know, it is said, that the magistrates were at the time when the apostle wrote, heathens; and that Nero, that monster of tyranny was then emperor of Rome; that therefore the apostle by enjoining submission to the powers that then were, does require unlimited obedience to be yielded to the worst of tyrants. Now not to insist upon what has been often observed, viz. that this epistle was written most probably about the beginning of Nero’s reign, at which time he was a very humane and merciful prince, did everything that was generous and benevolent to the publick, and shewed every act of mercy, and tenderness to particulars; and therefore might at that time justly deserve the character of the minister of God for good to the people; I say, waving this; we will suppose that this epistle was written after that Nero was become a monster of tyranny and wickedness, it will by no means follow from thence, that the apostle meant to enjoin unlimited subjection to such an authority, or that he intended to affirm, that such a cruel despotick authority was the ordinance of God. The plain obvious sense of his words (as we have already seen) forbids such a construction to be put upon them; for they plainly imply a strong abhorrence and disapprobation of such a character, and clearly prove that Nero, so far for thus he was a tyrant, could not be the minister of God, nor have a right to claim submission from the people; so that this ought perhaps rather to be view’d as a severe satyr upon Nero, than as enjoyning any submission to him.

It is also worthy to be observed, that the apostle prudently wav’d mentioning any particular persons that were then in power; as it might have been construed in an invidious light, and exposed the primitive Christians to the severe resentments of the men that were then in power. He only in general requires submission to the higher powers, because the powers that be are ordain’d of God; now tho’ the emperor might at that time be such a tyrant, that he could with no propriety be said to be ordain’d of God, yet it would be somewhat strange if there were no men in power among the Romans, that acted up to the character of good magistrates, and that deserved to be esteemed as the ministers of God for good unto the people: If there were any such, notwithstanding the tyranny of Nero, the apostle might with great propriety enjoin submission to those powers that were ordain’d of God, and by so particularly pointing out the end and design of magistrates, and giving his definition of a ruler, he might design to shew, that neither Nero, nor any other tyrant, ought to be esteemed as the minister of God.

Or, rather, which appears to me to be the true sense, the apostle meant to speak of magistracy in general, without any particular reference to the emperor, or any other person in power, that was then at Rome; and the meaning of this passage is, as if he had said, it is the duty of every Christian to be a good subject of civil government, for the power and authority of the civil magistrate are from God, for the powers that be are ordain’d of God i.e. the authority of the magistrates that are now either at Rome, or elsewhere, is ordained of the Deity; wherever you find any lawful magistrates, remember, they are of divine ordination; but that you may understand what I mean, when I say, that magistrates are of divine ordination; I will shew you how you may discern, who are lawful magistrates and ordain’d of God, who pursue the publick good by honouring and encouraging those that do well, and punishing all that do evil; such and such only, wherever they are to be found, are the ministers of God for good; to resist such, is resisting the ordinance of God, and exposing yourselves to the divine wrath and condemnation.

In either of these senses, the text cannot make anything in favour of arbitrary government. Nor could he with any propriety tell them, that they need not be afraid of the power, so long as they did that which was good, if he meant to recommend an unlimited submission to a tyrannical Nero; for the best characters were the likeliest to fall a sacrifice to his malice. And besides, such an injunction would be directly contrary to his own practice, and the practice of the primitive Christians, who refused to comply with the sinful commands of men in power; their answer in such cases being this, we ought to obey God rather than men: Hence the apostle Paul himself suffered many cruel persecutions, because he would not renounce Christianity, but persisted in opposing the idolatrous worship of the pagan world.

This text being rescued from the absurd interpretations, which the favourers of arbitrary government have put upon it, turns out to be a noble confirmation of that free and generous plan of government, which the law of nature and reason points out to us. Nor can we desire a more equitable plan of government, than what the apostle has here laid down: For if we consult our happiness and real good, we can never wish for an unreasonable liberty, viz. a freedom to do evil, which according to the apostle, is the only thing that the magistrate is to refrain us from. To have a liberty to do whatever is fit, reasonable or good, is the highest degree of freedom, that rational beings can possess. And how honourable a station are those men placed in by the providence of God, whose business it is, to secure to men this rational liberty, and to promote the happiness and welfare of society, by suppressing vice and immorality, and by honouring and encouraging everything that is amiable, virtuous and praiseworthy? Such magistrates ought to be honoured and obeyed as the ministers of God, and the servants of the king of heaven. Can we conceive of a larger and more generous plan of government than this of the apostle? Or can we find words more plainly expressive of a disapprobation of an arbitrary and tyrannical government? I never read this text without admiring the beauty and nervousness of it: and I can hardly conceive how he could express more ideas in so few words, than he has done. We see here, in one view, the honor that belongs to the magistrate, because he is ordain’d of God for the publick good. We have his duty pointed out, viz. to honour and encourage the virtuous, to promote the real good of the community, and to punish all wicked and injurious persons. We are taught the duty of the subject, viz. to obey the magistrate for conscience sake, because he is ordain’d of God; and that rulers being continually employed under God for our good, are to be generously maintained, by the paying them tribute; and that disobedience to rulers is highly criminal, and will expose us to the divine wrath. The liberty of the subject is also clearly asserted, viz. that subjects are to be allowed to do everything that is in itself just and right, and are only to be restrained from being guilty of wrong actions. It is also strongly implied, that when rulers become oppressive to the subject, and injurious to the state, their authority, their respect, their maintenance, and the duty of submitting to them must immediately cease; they are then to be considered as the ministers of satan; and as such it becomes our indispensable duty to resist and oppose them.

Thus we see, that both reason and revelation perfectly agree in pointing out the nature, and design of government, viz. that it is to promote the welfare and happiness of the community; and that subjects have a right to do everything that is good, praise-worthy, and consistent with the good of the community, and are only to be restrain’d when they do evil, and are injurious either to individuals or the whole community; and that they ought to submit to every law, that is beneficial to the community for conscience sake, altho’ it may in some measure interfere with their private interest; for every good man will be ready to forego his private interest for the sake of being beneficial to the publick. Reason and revelation (we see) do both teach us, that our obedience to rulers is not unlimited; but that resistance is not only allowable, but an indispensable duty in the case of intolerable tyranny and oppression. From both reason and revelation, we learn, that as the publick safety is the supreme law of the state, being the true standard and measure by which we are to judge whether any law or body of laws are just or not, so legislators have a right to make, and require subjection to, any set of laws, that have a tendency to promote the good of the community.

Our governours have a right to take every proper method to form the minds of their subjects so, that they may become good members of society. The great difference that we may observe among the several classes of mankind, arise chiefly from their education, and their laws; hence men become virtuous or vicious; good common wealths-men, or the contrary, generous, noble and courageous, or base, mean spirited and cowardly; according to the impression that they have received from the government that they are under, together with their education, and the methods that have been practiced by their leaders to form their minds in early life: Hence the necessity of good laws to encourage every noble and virtuous sentiment, to suppress vice and immorality; to promote industry, and to punish idleness that parent of innumerable evils; to promote arts and sciences, and to banish ignorance from amongst mankind.

And as nothing tends like religion and the fear of God to make men good members of the common wealth; it is the duty of magistrates to become the patrons and promoters of religion and piety, and to make suitable laws for the maintaining publick worship, and decently supporting the teachers of religion: Such laws (I apprehend) are absolutely necessary for the well being of civil society. Such laws may be made consistent with all that liberty of conscience, which every good member of society ought to be possessed of; for as there are few, if any religious societies among us, but what profess to believe and practice all the great duties of religion and morality, that are necessary for the well being of society, and the safety of the state; let everyone be allow’d to attend worship in his own society, or in that way, that he judges most agreeable to the will of God, and let him be obliged to contribute his assistance to the supporting and defraying the necessary charges of his own meeting. In this case no one can have any right to complain, that he is depriv’d of liberty of conscience, seeing that he has a right to choose and freely attend that worship, that appears to him to be most agreeable to the will of God; and it must be very unreasonable for him to object against being obliged to contribute his part towards the support of that worship, which he has chosen. Whether some such method as this might not tend in a very eminent manner to promote the peace and welfare of society, I must leave to the wisdom of our legislators to determine; before it would take off some of the most popular objections against being obliged by law to support publick worship, while the law restricts that support only to one denomination.

But for the civil authority to pretend to establish particular modes of faith, and forms of worship, and to punish all that deviate from the standard which our superiors have set up, is attended with the most pernicious consequences to society: It cramps all free and rational enquiry; fills the world with hypocrites and superstitious bigots; nay with infidels and scepticks: It exposes men of religion and conscience to the rage and malice of fiery blind zealots; and dissolves every tender tye of human nature: In short, it introduces confusion and every evil work. And I cannot but look upon it as a peculiar blessing of heaven, that we live in a land where everyone can freely deliver his sentiments upon religious subjects, and have the privilege of worshipping God, according to the dictates of his own conscience, without any molestation or disturbance: A privilege which I hope, we shall ever keep up, and strenuously maintain. No principles ought ever to be discountenanced by civil authority, but such as tend to the subversion of the state. So long as a man is a good member of society, he is accountable to God alone for his religious sentiments: But when men are found disturbers of the publick peace, stirring up sedition, or practicing against the state, no pretence of religion or conscience, ought to screen them from being brought to condign punishment is either to make restitution to the injured, or to restrain men from committing the like crimes for the future, so when these important ends are answered, the punishment ought to cease; for whatever is inflicted upon a man under the notion of punishment, after these important ends are answered, is not a just and lawful punishment, but is properly cruelty, and base revenge.

From this account of civil government we learn, that the business of magistrates is weighty and important: It requires both wisdom and integrity: When either are wanting, government will be poorly administered; more especially if our governours are men of loose morals, and abandoned principles; for if a man is not faithful to God and his own soul, how can we expect, that he will be faithful to the publick. There was a great deal of propriety in the advice that Jethro gave to Moses to provide able men; men of truth, that feared God, and that hated covetousness, and to appoint them for rulers over the people. For it certainly implies a very gross absurdity to suppose, that those who are ordain’d of God for the publick good, should have no regard to the laws of God; or that the ministers of God should be despisers of the divine commands. David the man after God’s own heart, makes piety a necessary qualification in a ruler; he that ruleth over men (says he) must be just, ruling in the fear of GOD: It is necessary it should be so, for the welfare and happiness of the state; for to say nothing of the venality and corruption, of the tyranny and oppression, that will take place under unjust rulers; barely their vicious and irregular lives will have a most pernicious effect upon the lives and manners of their subjects; their authority becomes despicable in the opinion of discerning men: And besides, with what face can they make, or execute laws against vices, which they practice with greediness? A people that have a right of choosing their magistrates, are criminally guilty in the sight of heaven when they are govern’d by caprice and humor, or are influenced by bribery to choose magistrates, that are irreligious men, who are devoid of sentiment, are of bad morals and base lives. Men cannot be sufficiently sensible, what a curse they may bring upon themselves, and their posterity, by foolishly and wickedly choosing men of abandoned characters and profligate lives for their magistrates and rulers.

We have already seen, that magistrates who rule in the fear of God, ought not only to be obey’d as the ministers of God; but that they ought also to be handsomely supported, that they may cheerfully and freely attend upon the duties of their station; for it is a great shame and disgrace to society, to see men that serve the public, laboring under indigent and needy circumstances; and besides, it is a maxim of eternal truth, that the labourer is worthy of his reward.

It is also a great duty incumbent on people to treat those in authority with all becoming honour and respect, to be very careful of casting any aspersion upon their characters. To despise government and to speak evil of dignities is represented in scripture as one of the worst of characters; and it was an injunction of Moses, thou shalt not speak evil of the ruler of thy people. Great mischief may ensue upon reviling the character of good rulers; for the unthinking herd of mankind are very apt to give ear to scandal: And when it falls upon men in power, it brings their authority into contempt, lessens their influence, and disheartens them from doing that service to the community of which they are capable: Whereas, when they are properly honoured, and treated with that respect which is due to their station; it inspires them with courage and a noble ardor to sere the publick; their influence among the people is strengthened, and their authority becomes firmly established. We ought to remember, that they are men like to ourselves, liable to the same imperfections and infirmities with the rest of us, and therefore so long as they aim at the publick good, their mistakes, misapprehensions and infirmities ought to be treated with the utmost humanity and tenderness.

But tho’ I would recommend to all Christians, as a part of the duty that they owe to magistrates, to treat them with proper honour and respect; none can reasonably suppose, that I mean that they ought to be flattered in their vices, or honoured and caressed while they are seeking to undermine and ruin the state: For this would be wickedly betraying our just rights, and we should be guilty of our own destruction: We ought ever to persevere with firmness and fortitude in maintaining and contending for all that liberty, that the Deity has granted us: It is our duty to be ever watchful over our just rights, and not suffer them to be wrested out of our hands by any of the artifices of tyrannical oppressors. But there is a wide difference between being jealous of our rights, when we have the strongest reason to conclude, that they are invaded by our rulers, and being unreasonably suspicious of men that are zealously endeavouring to support the constitution, only because we do not thoroughly comprehend all their designs: The first argues a noble and generous mind, the other a low and base spirit.

Thus have I considered the nature of the duty enjoin’d in the text, and have endeavoured to shew, that the same principles that require obedience to lawful magistrates, do also require us to resist tyrants; this I have confirm’d from reason, and scripture.

It was with a particular view to the present unhappy controversy that subsists between us, and Great-Britain, that I chose to discourse upon the nature and design of government, and the rights and duties both of governors, and governed, that so, justly understanding our rights and privileges, we may stand firm in our opposition to ministerial tyranny, while at the same time we pay all proper obedience and submission to our lawful magistrates; and that while we are contending for liberty, we may avoid running into licentiousness; and that we may preserve the due medium between submitting to tyranny, and running into anarchy. I acknowledge that I have undertaken a difficult task; but, as it appear’d to me, the present state of affairs loudly call’d for such a discourse; and therefore I hope the wise, the generous, and the good will candidly receive my good intentions to serve the public. I shall now apply this discourse to the grand controversy that at this day subsists between Great-Britain and the American colonies.

And here in the first place, I cannot but take notice, how wonderfully providence has smiled upon us by causing the several colonies to unite so firmly together against the tyranny of Great-Britain, tho’ differing from each other in their particular interest, forms of government, modes of worship, and particular customs and manners; besides several animosities that had subsisted among them. That under these circumstances, such an union should take place, as we now behold, was a thing that might rather have been wished than hoped for.

And in the next place, Who could have thought, that when our charter was vacated, when we became destitute of any legislative authority; and when our courts of justice in many parts of the country were stop’d, so that we could neither make, nor execute laws upon offenders, who I say would have thought, that in such a situation, the people should behave so peaceably, and maintain such good order and harmony among themselves! This is a plain proof, that they having not the civil law to regulate themselves by, became a law unto themselves; and by their conduct they have shewn, that they were regulated by the law of God written in their hearts. This is the Lord’s doing, and it ought to be marvelous in our eyes.

From what has been said in this discourse, it will appear, that we are in the way of our duty, in opposing the tyranny of Great-Britain; for if unlimited submission is not due to any human power; if we have an undoubted right to oppose and resist a set of tyrants, that are subverting our just rights and privileges, there cannot remain a doubt in any man, that will calmly attend to reason, whether we have a right to resist and oppose the arbitrary measures of the King and Parliament; for it is plain to demonstration, nay it is in a manner self-evident, that they have been, and are endeavouring to deprive us not only of the privileges of Englishmen, and our charter rights, but they have endeavour’d to deprive us of what is much more sacred, viz. the privileges of men and Christians 2i.e. they are robbing us of the unalienable rights, that the God of nature has given us in his written word as Christians, and disciples of that Jesus, who came to redeem us from the bondage of sin, and the tyranny of satan, and to grant us the most perfect freedom, even the glorious liberty of the sons and children of God; that here they have endeavour’d to deprive us of the sacred charter of the king of heaven. But we have this for our consolation, the Lord reigneth, he governs the world in righteousness, and will avenge the cause of the oppressed, when they cry unto him. We have made our appeal to heaven, and we cannot doubt, but that the judge of all the earth will do right.

Need I upon this occasion descend to particulars? Can anyone be ignorant what the things are of which we complain? Does not everyone know, that the King and Parliament have assumed the right to tax us without our consent? And can anyone be so lost to the principles of humanity and common sense, as not to view their conduct in this affair as a very grievous imposition? Reason and equity require that no one be obliged to pay a tax that he has never consented to, either by himself, or by his representative: But as divine providence has plaed us at so great a distance from Great-Britain, that we neither are, nor can be properly represented in the British parliament; it is a plain proof that the Deity design’d, that we should have the powers of legislation and taxation among ourselves: For can any suppose it to be reasonable, that a set of men that are perfect strangers to us, should have the uncontroulable right to lay the most heavy and grievous burdens upon us that they please, purely to gratify their unbounded avarice and luxury? Must we be obliged to perish with cold and hunger to maintain them in idleness, in all kinds of debauchery and dissipation? But if they have the right to take our property from us without our consent, we must be wholly at their mercy for our food and raiment, and we know by sad experience, that their tender mercies are cruel.

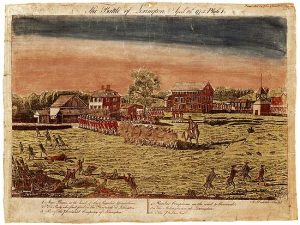

But because we were not willing to submit to such an unrighteous and cruel decree; tho’ we modestly complain’d and humbly petition’d for a redress of grievances, instead of hearing our complaints and granting our requests, they have gone on to add iniquity to transgression, by making several cruel and unrighteous acts. Who can forget the cruel act to block up the harbor of Boston, whereby thousands of innocent persons must have been inevitably ruin’d had they not been supported by the continent? Who can forget the act for vacating our charter, together with many other cruel acts which, it is needless to mention? But not being able to accomplish their wicked purposes by meer acts of parliament, they have proceeded to commence open hostilities against us; and have endeavour’d to destroy us by fire and sword; our towns they have burnt, our brethren they have slain, our vessels they have taken, and our goods they have spoiled. And after all this wanton exertion of arbitrary power, is there he man that has any of the feelings of humanity left, who is not fired with a noble indignation against such merciless tyrants; who have not only brought upon us all the horrors of a civil war, but have also added a piece of barbarity unknown to Turks and Mahometan infidels; yea such as would be abhor’d and detested by the savages of the wilderness: I mean their cruelly forcing our brethren, whom they have taken prisoners, without any distinction of whig or tory, to serve on board their ships of war, thereby obliging them to take up arms against their own countrymen, and to fight against their brethren, their wives, and their children, and to assist in plundering their own estates. This my brethren, is done by men who call themselves Christians against their Christian brethren against men who till now gloried in the name of Englishmen, and who were ever ready to spend their lives and fortunes in the defence of British rights: Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Ashkelon, lest it cause our enemies to rejoice, and our adversaries to triumph. Such a conduct as this, brings a great reproach upon the profession of Christianity, nay it is a great scandal even to human nature itself.

It would be highly criminal not to feel a due resentment against such tyrannical monsters. It is an indispensable duty my brethren which we owe to God, and our country, to rouse up and bestir ourselves, and being animated with a noble zeal for the sacred cause of liberty, to defend our lives, and fortunes, even to the shedding the last drop of blood. The love of our country, the tender affection that we have for our wives and children, the regard we ought to have for unborn posterity, yea everything that is dear and sacred, do now loudly call upon us, to use our best endeavours to save our country: We must eat our plow-shares into swords, and our pruning hooks into spears, and learn the art of self-defence against our enemies. To be careless and remiss, or to neglect the cause of our country thro’ the base motives of avarice, and self interest, will expose us not only to the resentments of our fellow creatures, but to the displeasure of God Almighty: For to such base wretches in such a time as this, we may apply with the utmost propriety that passage in Jer. 48 chap. ver. 10. Cursed be he that doeth the work of the Lord deceitfully, and cursed be he, that keepeth back his sword from blood. To save our country from the hands of our oppressors, ought to be dearer to us, even than our own lives, and next the eternal salvation of our own souls, is the thing of the greatest importance: A duty so sacred, that it cannot justly be dispensed with for the sake of our secular concerns: Doubtless for this reason God has been pleased, to manifest his anger against those who have refused to assist their country against its cruel oppressors. Hence in a case similar to ours, when the Israelites were struggling to deliver themselves from the tyranny of Jabin the king of Canaan, we find a most bitter curse denounced against those, who refused to grant their assistance in the common cause; see Judges 5th, ver. 23. Curse ye Meroz (said the angel of the Lord) Curse ye bitterly the inhabitants thereof, because they came not to the help of the Lord, to the help of the Lord against the mighty.

Now if such a bitter curse is denounced against those, who refused to assist their country against its oppressors, what a dreadful doom are those exposed to, who have not only refused to assist their country in this time of distress, but hae thro’ motives of interest or ambition shewn themselves enemies to their country by opposing us in the measures that we have taken, and by openly favouring the British Parliament. He that is so lost to humanity, as to be willing to sacrifice his country for the sake of avarice or ambition, has arrived to the highest stage of wickedness, that human nature is capable of, and deserves a much worse name, than I at present care to give him; but I think I may with propriety say, that such a person has forfeited his right to human society, and that he ought to take up his abode not among the savage men, but among the savage beasts of the wilderness.

Nor can I wholly excuse from blame those timid persons, who thro’ their own cowardice, have been induced to favour our enemies, and have refused to act in defence of their country: For a due sense of the ruin and destruction that our enemies are bringing upon us, is enough to raise such a resentment in the human breast, that would (I should think) be sufficient to banish fear from the most timid make: And besides to indulge cowardice in such a cause, argues a want of faith in God; for can he that firmly believes and relies upon the providence of God, doubt, whether h e will avenge the cause of the injured when they apply to him for help: For my own part, when I consider the dispensations of providence towards this land, ever since our fathers first settled in Plymouth, I find abundant reason to conclude, that the great sovereign of the universe, has planted a vine in this American wilderness, which he has caused to take deep root, and it has filled the land, and that he will never suffer it to be plucked up, or destroyed.