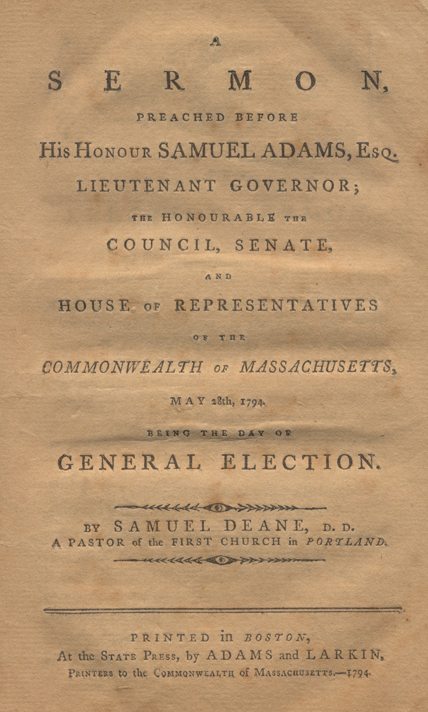

Timothy Stone was born in 1742 and graduated from Yale College in 1763. He spent a year studying theology under the Rev. Brinsmade and began preaching in Connecticut in 1765. This is the text of his Election Day sermon from May 10, 1792.

Sermon,

Preached Before His Excellency

Samuel Huntington, Esq. L.L.D.

Governor,

And The Honorable The

General Assembly

Of The

State of Connecticut,

Convened At Hartford, on the Day of the

Anniversary Election.

May 10th,1792.

By Timothy Stone, A.M.

Pastor of a Church in Lebanon.

“At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, in said State, on the second Thursday of May, A.D. 1792.

Ordered, That the Hon. William Williams, and Mr. Elkanah Tisdale, return the Thanks of this Assembly to the Rev. Timothy Stone, for his Sermon delivered before this Assembly at the General Election on the 10th of May instant, and desire a Copy of the same that it may be printed.

A true Copy of Record.

Examined, by George Wyllys. Sec’y.”

Behold, I have taught you statutes and judgments even as

the Lord my God commanded me, that ye should do so

in the land whether ye go to possess it. Keep, therefore,

and do them; for this is your wisdom and your

understanding in the sight of the nations,

which shall hear all these statutes and say,

“Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.”

DEUTERONOMY IV.5, 6.

We are not left in doubt concerning the wisdom and salutary [useful] nature of that constitution under which the Hebrews were placed, as it proceeded immediately from God; and in reference to the particular circumstances of that people, was the result of unerring perfection. It was a free constitution in which all the valuable rights of the community were most happily secure. The public good was the great object in view, and the most effectual care was taken to preserve the rights of individuals. Proper rewards were promised to the obedient and righteous punishments allotted for the disobedient [Deuteronomy 28:l,15]. God designed for special reasons that [the] seed of Abraham should be distinguished in a peculiar manner from all other nations; He therefore undertook the government of them Himself in all matters respecting religion, civil policy, and that military establishment which he saw to be necessary for their happiness and defense. We find Moses — who received this constitution from God and delivered it to his people — frequently exhorting them to maintain a sacred regard for this Divine institution and to pay a conscientious obedience to all its laws, in doing of which they might secure to themselves national prosperity and enjoy the unfailing protection of Almighty God [Deuteronomy 28:1-14; Leviticus 26:3-12; Deuteronomy 4:5-8].

To deter them from disobedience, he called up their attention to that solemn scene which opened to their view when they stood before the Lord their God in Horeb — when there were thunders and lightnings and a thick cloud upon the mount and the voice of the trumpet exceeding loud so that all the people that was in the camp trembled [Exodus 19:16]. And the Lord commanded saying, “gather Me the people together and I will make them bear My words that they may learn to fear Me all the days that they shall live upon the earth, and that they may teach their children. For the Lord thy God is a consuming fire, even a jealous God” [Deuteronomy 4:10, 24].

The argument made use of in the text to excite in that people a spirit of obedience to their constitution and laws was this: that it would raise their character in the sight of the nations, who from thence would be led to entertain a veneration [respect and admiration] for them as a great nation, a wise and understanding people. This sacred passage, in connection with the important occasion which hath called us to the house of God this morning, may direct our attention to the following inquiry: in what doth the true wisdom of a people — a civil community — consist?

The general answer to this question may not be difficult; it will no doubt be readily admitted that the highest wisdom of a community of intelligent beings must consist in pursuing that line of conduct which shall have the most direct and sure tendency to promote the best good of the whole, both in time and eternity Whatever creatures may conceive to be a good, either through imperfection of understanding or degeneracy of heart, yet if that which they call good is inseparably connected with more pain than pleasure, taking in the whole of their existence, then it cannot with propriety be styled good — certainly not the best good; consequently wisdom will not choose it. The province of wisdom is to discover and elect the most valuable objects and to adopt the best means to obtain them. These observations apply with equal force to individuals and communities — to all classes of men, whether in the higher or lower walks of life. Communities, most certainly as well as individuals, under guidance of wisdom will pursue that conduct which shall have the desired tendency and will affect the highest good. This question as it respects mankind at large in their present state might admit a great variety of answers, some of which may demand particular notice on the present occasion. As,

1. Wisdom will direct a community to establish a good system of government. It may be a question whether the all-wise God ever designed that any of His intelligent creatures — even in a state of perfection — should exist without some kind of government and subordinating amongst themselves. All creatures have the same capacities; neither are they placed under equal advantages; and if those may be found whose capacities are equally extensive, still they are different and seem to be designed for different purposes and stations in the great system. We read of thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers amongst the angelic hosts [Colossians 1:16 & Ephesians 3:10], which titles denote various stations among those sinless beings, that they are differently employed in degrees of subordination to each other in the government of that holy family of which God is the father. But however this may be (as our acquaintance with that world of glory is very imperfect), yet it is beyond doubt that government was designed and is absolutely necessary for men on earth in their present state of degeneracy.

Creatures who have risen in rebellion against the holy and perfect government of Jehovah have partial connections [an attachment to their temporal life above their eternal life], selfish interests, passions, and lusts which often interfere with each other and which will not always be controlled by reason and the mild influence of moral motives however great: but these in their external expressions must be under the restraint of law or there can be no peace — no safety among men. Some kind of government is therefore indispensably necessary for the happiness of mankind that they may partake of the security and other important blessings resulting from society which cannot be enjoyed in a state of nature. Without any consideration of the various forms of government which have been adopted in different ages and countries, that may be the best for a particular people which in the view of all their circumstances affords the fairest prospect of promoting righteousness and of securing the most valuable privileges of the community in its administration.

Civil liberty is one of the most important blessings which men possess of a temporal nature — the most valuable inheritance on this side heaven. That constitution may therefore be esteemed on the best which doth most effectually secure this treasure to a community. That liberty consists in freedom from restraint, leaving each one to act as seemeth right to himself, is a most unwise mistaken apprehension [Proverbs 14:12 & 16:25]. Civil liberty consists in the being and administration of such a system of laws as doth bind all classes of men — rulers and subjects — to unite their exertions for the promotion of virtue and public happiness. That happy constitution enjoyed by the Hebrews of which the Supreme Lawgiver was the immediate [author], other than a system of good laws and righteous statutes which limited the powers and prerogatives of magistrates, designated the duties of subjects and obliged each to that obedience to law and exchange of services which tended to mutual benefit. (Deuteronomy 4:8): “And what nation is there so great that hath statutes and judgments so righteous as all this law which I set before you this day.” A state of society necessarily implies reciprocal dependence in all its members, and rational government is designed to realize and strengthen this dependence and to render it in such sense equal in all ranks — from the supreme magistrate to the meanest peasant — that each one may feel himself bound to seek the good of the whole. When individuals do this, whether rulers or subjects, they have a just right to expect the favor and protection of the whole body. The laws of a state should equally bind every member, whether his station be the most conspicuous or the most obscure. Rulers in a righteous government are as really under the control of law as the meanest [lowest] subject, and the one equally with the other should be subjected to punishment whenever he becomes criminal by a violation of the law. Rewards and punishments should be equally distributed to all, agreeably to real merit or demerit without respect of persons. A constitution founded upon the general and immutable laws of righteousness and benevolence, and corresponding to their particular circumstances, will therefore become a primary object with a wise and understanding people.

2. The wisdom of a people will appear in their united exertions to support such a system of government in its regular administration.

Enacting salutary laws discovers the wisdom and good design of legislators, but the liberty and happiness of the community essentially depend upon their regular execution. The best code of laws can answer no good purposes any further than it is executed. Every member in society is bound in duty to the community, himself, and posterity to use his endeavors that the laws of the state be carried into execution.

Laws point out the existing offices, relations, and dependencies of the community; they serve for the direction, support, and defense of all characters; but considered as restrainers, they more especially respect the unruly members. (I Timothy 1:9,10): “Knowing this, that the law is not made for a righteous man, but for the lawless and disobedient, for the ungodly and for sinners, for unholy and profane, for murderers of fathers and murderers of mothers, for manslayers, for whoremongers, for them that defile themselves with mankind, for liars, for perjured persons, and if there be any other thing that is contrary to sound doctrine.”

It is unreasonable to expect that the vices of man which are inimical [harmful] to society will be restrained by silent laws existing upon paper; they must be carried into execution and be known to have an active existence that such as contemn [disrespect and ignore] the law may not only read but feel the resentment of the community. It is not within the reach of human understanding to look with precision into futurity – to discover all the circumstances and contingencies which may take place among a people; neither is it certain that every person who may possess a fair character for ability and integrity, and who may be called into public life, will be governed in all his actions by public and disinterested motives. Through necessary imperfection or corrupt design, statutes may be enacted which may not prove salutary in their execution but greatly prejudicial to the common good; hence ariseth the necessity of alterations and amendments in all human systems.

Changes, however, should be few as possible, for the strength and reputation of government doth not a little depend upon the uniformity and stability observed in its administration. Laws, while they remain such, ought to be executed; when found to be useless or hurtful, they may be repealed. To have laws in force and not executed, or to obstruct the natural course of law in a free state, must be dangerous will have many hurtful tendencies, will greatly weaken government, and render all the interests of the community insecure. Liberty, property, and life are all precarious [insecure] in a state where laws cease in their execution. When known breachers of law pass with impunity [without penalty] and open transgressors go unpunished — when executive officers grow remiss in their duty, especially when they connive [wink] at disobedience — all distinctions betwixt virtue and vice will vanish, authority will sink into disrepute, and government will be trampled in the dust — for which reasons (with others that might be named), it must be the wisdom — the indispensable duty of all characters in society — to unite their exertions for the support of righteous laws in their regular administration.

As it would be exceedingly unreasonable to expect that any people can ever realize the benefits of good government under a weak or a wicked administration in which persons destitute of abilities or of stable principles of righteousness and goodness fill the various departments of the state, hence,

3. The wisdom of a people will appear in the election of good rulers.

The peace and happiness of communities have a necessary dependence, under God, upon the character and conduct of those who are called to the administration of government. A bad constitution, under the direction of wise and pious rulers who have capacity to discern [and the] disposition and resolution to pursue the public good, may become a blessing being made to subserve many valuable purposes. But the best constitution committed to rulers of a contrary description may be subverted or so abused as to become a curse and be rendered productive of the most mischievous consequences. The understanding or folly of a people in reference to their temporal interests is in nothing more conspicuous than in the choice of civil rulers. In free states the body of electors have it in their power to be governed well if faithful to themselves and the public in raising those to offices of trust and importance who are possessed of abilities and have merited their confidence by former good services.

Knowledge and fidelity are qualifications indispensably necessary to form the character of good magistrates. No man ever possessed natural or acquired abilities too great for the discharge of the duties constantly incumbent upon those who act as the representatives of the Most High God in the government of their fellow creatures: multitudes, however well disposed, are totally incapable of such trust. The interests of society are always important; they are many times involved in extreme difficulty through the weakness of some and the wickedness of others; and there is need of the most extensive knowledge, wisdom, and prudence to direct the various opposing interests of individuals into one channel and guide them all to a single object: the public good. Woe to that people to whom God by His providence [Divine sustenance, oversight, and intervention]in judgment shall say, “I will give children to be their princes, and babes shall rule over them. And the people shall be oppressed every one by another and every one by his neighbor: the child shall behave himself proudly against the ancient and the base against the honorable. And judgment is turned away backward and justice standeth afar off, for truth is fallen in the street and equity cannot enter; and he that departeth from evil maketh himself a prey” (Isaiah 3:4,5 and 59:14,15).

But knowledge alone will qualify no person to fill a public station with honor to himself or advantage to others. The greatest abilities — the most extensive knowledge — are capable of abuse; and when misapplied to selfish ambitious purposes, may be improved to the destruction of everything valuable in society.

Fidelity [integrity], therefore, is another essential characteristic in a good ruler. This is a qualification so absolutely essential that when known to be wanting, no conceivable abilities can atone for its absence. Fidelity hath no sure unshaken foundation but in the love and fear of the one true God — that love which extends its benign [gentle] influence to all the creatures of God. This is a branch of that benevolent religion which the Son of God came down from Heaven to establish in the hearts of men on earth; this, when seated in the soul of man, becomes a stable principle of action and will have a habitual influence in all his conduct, whether in public or private life; this will enable rulers to maintain the dignity of their elevated stations amidst the strong temptations with which they may be assaulted, feeling their just accountableness to those of their fellow men who have placed such confidence in them as to entrust them with all their valuable temporal interests — and what is infinitely more, feeling their accountableness to God, they will labor to discharge the important duties of their office, remembering that the day is fast approaching when notwithstanding “they are gods, and children of the Most High, yet they shall die like men, and fall like one of the princes” [Psalm 82:6-7]. Able pious magistrates who wish to answer the end of their appointment will not wish to hide their real characters from the public eye; they will come to the light that their deeds may be manifest [John 3:21].

It is the interest and privilege of an enlightened free people to be acquainted with the characters of their most worthy citizens who are candidates for public offices in the community; and it is equally their interest and privilege to make choice of those only to be rulers who are known among their tribes for wisdom and piety. Following the salutary counsel of the prince of Midian, they will provide out of all the people, able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness [Exodus 18:21].

Free republicans, as observed above, have it in their power to be governed well, but they are in the utmost danger through a wanton abuse of this power. Actuated by noble public spirited motives and a primary regard to real merit in their elections, they will have the heads of their tribes as fathers to lead them in paths of safety and peace. Under the guidance of such rulers who consider their subjects as brethren and children, and all the interests of the community as their own, a people can hardly fail of all that happiness of which societies are capable in this degenerate state.

But when party spirit, local views, and interested motives direct their suffrages — when they lose sight of the great end of government the public good and give themselves up to the baneful influence of parasitical demagogues – they may well expect to reap the bitter fruits of their own folly in a partial unwavering administration. Through the neglect — or abuse — of their privileges, most states have lost their liberties and have fallen a prey to the avarice [greed] and ambition of designing and wicked men. “When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice: but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn” [Proverbs 29:2]. This joy — or mourning — among a people greatly depends on their own conduct in elections. Bribery here is the bane of society; the man who will give or receive a reward in this case must be extremely ignorant not to deserve the stigma of an enemy to the state; and should he have address to avoid discovery, he must be destitute of sensibility not to feel himself to be despicable. All private dishonorable methods to raise persons to office convey a strong suspicion to the discerning mind that merit is wanting; real merit may dwell in obscurity, but it needeth not; neither will it ever solicit the aids of corruption to bring itself into view. When streams are polluted in their fountain they will not fail to run impure; offices in government obtained by purchase, will always be improved to regain the purchase money with large increase, and a venal administration [one that may be bought or sold for money or influence] will possess neither disposition nor strength to correct the vices of others but will lose sight of the public happiness in the eager pursuit of personal emolument [gain].

4. Wisdom will lead a people to maintain a sacred regard to righteousness in reference to the public and individuals.

Moral righteousness is one of those strong bonds by which all public societies are supported. Heathen nations ignorant of divine revelation and the particular duties and obligations which are enlightened and enforced by the word and authority of God, have nevertheless been sensible of the great importance of moral righteousness. Greece and Rome in the beginning of their greatness, before they sunk into effeminacy and corruption, were careful to encourage and maintain public and private justice — they labored to diffuse principles of righteousness among all ranks of their citizens. Many of their writings on this subject deserve attentions so far as the observance of moral duties respect civil communities and the well-being of mankind in the present world. As all civil communities have their foundation in compacts by which individuals immerge out of a state of nature and become one great whole — cemented together by voluntary engagements, covenanting with each other to observe such regulations and perform such duties as may tend to mutual advantage — hence ariseth the necessity of righteousness, this being the basis on which all must depend. When this fails, compacts [agreements and contracts] will be disregarded, men will lose a sense of their obligations to each other, instead of confidence and harmony will be a spirit of distrust and fear, every man will be afraid of his neighbor, jealousies will subsist between rulers and subjects, the strength of the community will be lost in animosity and division all ability for united exertion will be destroyed; and the bonds of society being broken, it must be dissolved. It was long since observed by one of the greatest and wisest of kings and will forever remain true: “That righteousness exalteth a nation: but sin is a reproach to any people” [Proverbs 14:34]. The truth of this divine maxim doth not depend upon any arbitrary contribution or positive system of government but flows from the reason and nature of things.

There is in the constitution of heaven an established connection between the practice of righteousness and the happiness of moral beings united in society. Public faith and private justice lay a foundation for public spirit and vigorous exertion to rest upon; in such a state, every one will realize such punishment as his offence or neglect of duty may deserve. In a fixed regular course of communicative and distributive justice, all may know before hand what the reward of their conduct will be. What the apostle hath said concerning the natural body (and applied to the church of Christ) may with equal propriety and little variation be applied to political societies. These bodies are composed of various members; the members have various offices; but all of them are necessary for the well being of the whole; there is something due from the body to every member and from every member to the body; every part is to be regarded and righteousness maintained throughout the whole [1 Corinthians 12:12-26].

The members of a well-organized civil community, under an equal and just administration, have no more reason to complain of the station allotted to them in Providence [Divine sustenance, oversight, and intervention] than the members of the natural body have of the place by God assigned them in that. “The eye cannot say unto the head, I have no need of thee; nor again the head to the feet, I have no need of you. But that the members should have the same care one for another. And whether one member suffer, all the members suffer with it; or one member be honored, all the members rejoice with it” [1 Corinthians 12:21,25,26]. No member of the natural body of a civil community or of God’s moral kingdom can be required to do more than observe the proper duty of its own station; when this is performed, all is done which can reasonably be demanded; it hath done well and may expect the approbation [praise] and protection of the whole body.

Men may indeed complain because they are not angels, and do it with as much propriety as to feel discontented because they are not all placed at the head of civil communities. The all-wise God hath given us our capacities and fixed our stations, and when righteousness is observed by us and the community of which we are members, we shall then do and receive what belongs to us, and this is all we can reasonably desire.

5. The wisdom of a people essentially consists in paying an unfeigned [unhypocritical and sincere] obedience to the institutions of that religion which the Supreme Lawgiver hath established in His church on earth.

That religion which God hath enjoined [commanded] upon rational beings is not only necessary for His glory but essential to their happiness. To establish a character as being truly religious under the light of divine revelation, it is by no means sufficient that men should barely acknowledge the existence and general providence of one supreme Deity. From this heavenly light, we obtain decided evidence that the Almighty Father hath set His well beloved Son, the blessed Immanuel, as King upon His holy hill of Zion. This Divine person, in His mediatorial character, “is exalted far above all principality, and power, and might, and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this world but also in that which is to come. And all things are put under His feet” [Ephesians 1:21-22]. “That at the name of Jesus, every knee should bow, of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth; and that every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” [Philippians 2:10-11].

In vain do guilty mortals worship the great Jehovah and present their services before Him but [except] in the name and for the sake of this glorious Mediator. For it is His will “that all men should honor the Son, even as they honor the Father.” [John 5:23]

Communities have their existence in and from this glorious Personage. The kingdom is His, and He ruleth among the nations [Psalm 22:28]. Through His bounty and special providence [Divine sustenance, oversight, and intervention] it is that a people enjoy the inestimable liberties and numerous advantages of a well-regulated civil society – through His influence they are inspired with understanding to adopt with strength, and public spirit to maintain, a righteous constitution. He gives able impartial rulers to guide in paths of virtue and peace or sets up over them the basest of men. By His invisible hand, states are preserved from internal convulsions [disturbances] and shielded by His Almighty arm from external violence; or through His providential displeasure they are given as a prey to their own vices — or to the lusts and passions of other states — to be destroyed. Thus absolutely dependant are temporal communities and all human things upon Him who reigneth King in Zion [Daniel 4:17,25,32]. “Be wise now therefore, O ye kings; be instructed, ye judges of the earth. Kiss the Son lest He be angry, and ye perish from the way, when His wrath is kindled but a little: blessed are all they that put their trust in Him” [Psalm 2:10,12].

The holy religion of the Son of God hath a most powerful and benign influence upon moral beings in society. It not only restrains malicious revengeful passions and curbs unruly lusts, but will in event eradicate them all from the human breast. It implants all the divine graces and social virtues in the heart; it sweetens the dispositions of men and fits them for all the pleasing satisfactions of rational friendship; teaches them self denial; inspires them with a generous public spirit; fills them with love to others — to righteousness and mercy — and makes them careful to discharge the duties of their stations; diligent and contented in their callings. This, beyond any other consideration, will increase the real dignity of rulers, will give quiet and submission to subjects; this is the only true and genuine sprit of liberty which can give abiding union and energy to states and will enable them to bear prosperity without pride and support them in adversity without dejection; this will afford all classes of men consolation in death and render them happy in God — their full eternal portion — in the coming the world.

Religion, therefore, is the glory of all intelligent beings from the highest angel to the meanest [lowliest] of the human race and will forever happily its possessors, considered either individually or as connected in society, for this assimilates the hearts of creatures to the great fountain of being in the exercise of general and disinterested affection and is the consummation of wisdom.

If the preceding observations have their foundation in reason and the Word of God, we see the happy connection between religion and good government. The idea that there is, and ought to be, no connection between religion and civil policy appears to rest upon this absurd supposition: that men, by entering into society for mutual advantage, become quite a different class of beings from what they were before — that they cease to be moral beings and consequently lose their relation and obligations to God as His creatures and subjects and also their relations to each other as rational social creatures. If these are the real consequences of civil connections, they are unhappy indeed as they must exceedingly debase and degrade human nature; and it is readily acknowledged these things being true, that religion can have no further demands upon them. But if none of the relations or obligations of men to their Creator and each other are lost by entering into society — if they still remain moral accountable beings and if religion is the glory and perfection of moral beings — then the connection between religion and good government is evident and all attempts to separate them are unfriendly to society and inimical [harmful] to good government and must originate in ignorance or bad design. Religion essentially consists in friendly affection to God and His rational offspring [i.e., mankind], and such affection can never injure that government which hath public happiness for its object.

Attempts have been made to distinguish between moral and political wisdom – moral and political righteousness — as though there were two kinds of wisdom and righteousness, distinct in their nature and applicable only to different subjects: that which is moral belonging to the government of men as subjects of God’s dominion, and that which is political to men as subjects of civil rule. But if wisdom and righteousness are the same in the fountain as in the streams — in God as in His creatures, differing not in the nature and kind but only in degree — then all such distinctions are manifestly without foundation. We read, it is true, of a particular kind of wisdom, the fruit of which is “bitter envying and strife and every evil work: and that this wisdom is earthly, sensual, and devilish” [James 3:14,15]. But until it is made to appear that this is more friendly to civil government than the wisdom “from above, which is pure and peaceable, full of mercy and good fruits, without partiality, and without hypocrisy” (James 3:17), the supposed distinction will not apply to human governments with advantage, nor destroy the connection between religion and good government.

Religion and civil government are not one and same thing; though both may — and are — designed to embrace some of the same objects, yet the former extends its obligations and designs immensely beyond what the latter can pretend to, and it hath rights and prerogatives [privileges] with which the latter may not intermeddle. Still, there are many ways in which civil government may give countenance [approval], encouragement, and even support to religion without invading the prerogatives of the Most High or touching the inferior, though sacred, rights of conscience and in doing of which it may not only shew its friendly regard to Christianity but derive important advantages to itself.

The friends of true happiness, whether ministers of state or ministers of religion, or in what ever character they may act, will therefore exert themselves to promote that cause which aims at no less an object than the glory of Jehovah and the highest felicity of his unlimited and eternal kingdom.

A civil community formed, organized, and administered agreeably to the principles which have been suggested will possess internal peace and energy; its strength and wealth may easily be collected for necessary defense; consequently will ever be prepared to repel foreign injuries: it will enjoy prosperity within itself and become respectable amongst the nations of the earth.

Could this — and the other states in the American Republic in their separate and united capacities — be established upon the principles of true wisdom — [upon] that righteousness and goodness which have their foundation in the nature of things and are essential parts of the Christian system — could we build upon this foundation, we might set forth a good example and become a blessing to mankind; in this way we might establish character as a wise and understanding people [and] become (Song of Solomon 6:4,10) “beautiful as Tirzah, comely as Jerusalem”; we should “look forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners.”

Those deserve well of their brethren who have devoted their time and superior abilities to the public in the establishment and administration of civil constitutions which are calculated to answer purposes importantly beneficial to mankind. These thoughts may call our grateful attention to the honorable and venerable characters collected this morning in the house of God. Some respectful, serious addresses to the different characters here present may conclude this discourse.

May it please YOUR EXCELLENCY (for more information see note #1), seats of dignity of free republics are truly honorable where merit and the voice of uncorrupted citizens are the only causes of elevation [placing in office]. The first Magistrate in such a state is more respectable than the most powerful monarch who obtains his throne either by arbitrary usurpation, the arts of venality [buying or selling office for money or influence], or even the fortunate circumstance of hereditary succession. In either of the instances supposed, the throne may be filled without personal worth, may be supported by the same means by which it was at first obtained, and may be improved for the purposes of idleness and dissipation — or what is worse, to consume the wealth, destroy the liberties, and even sport with the lives of subjects. By means of such abuse of power, a people will be rendered vastly more wretched than they would have been in a state of nature and yet find it extremely difficult to extricate themselves from these complicated evils. But such abuse of power cannot so easily take place or be continued in free republican governments where places of honor are inseparably connected with important duties — duties which must be performed, otherwise such places will not long be supported under the jealous inspection of a people possessed of the knowledge and love of liberty, together with the means of its preservation.

These considerations add to the merit and increase the luster of those worthy characters which have been repeatedly called by the united voice of their brethren to preside in this State. The understanding of this people and their knowledge of worth have been conspicuous in the attention generally paid to deserving personages in the election of their rulers — especially in the long succession of wise religious governors whose eminent talents and pious examples have been so extensively beneficial to this community. (For more information see note #2.)

May your Excellency’s name, in this honorable catalogue, remain a lasting memorial of the many services which you have rendered to this people as a public testimony of the respect of your enlightened fellow citizens, and may your unremitted exertions for their prosperity be continued and all your benevolent endeavors to promote their temporal and eternal interests meet the Divine blessing — may you never bear that sword in vain which the exalted Mediator, through the instrumentality of men, hath put into your hand [Romans 13:4]; let this be a shield to the innocent, the widow, and the orphan in their oppressions while it remains a terror to all such as do evil [Jeremiah 22:3 & Romans 13:3]. You will, if possible, scatter the wicked with your eyes [Proverbs 20:8]; but when coercion becomes necessary, you will bring the wheel over them [Proverbs 20:26].

Sensible of the weighty cares and strong temptations of your exalted station, may your dependence be increasingly fixed on that glorious and gracious Being Who hath called you to office, esteeming His approbation [approval and praise] infinitely superior to the applause of mortals. By the weight of your example and the influence of that authority with which you are clothed, may you, sir, do much for the honor of God the Redeemer — for the advancement of His holy religion among men — for the promotion of righteousness and peace in this and the United States of America — for the abolition of slavery and every species of oppression — for the increase of civil and religious liberty in the earth. And when by the Supreme Disposer of all events you may be called to relinquish the honors and cares of this mortal life, our prayer to Almighty God is that in that solemn hour you may enjoy the supports of conscious integrity, meet with the approbation of your Judge, and be graciously received to the society of the blessed.

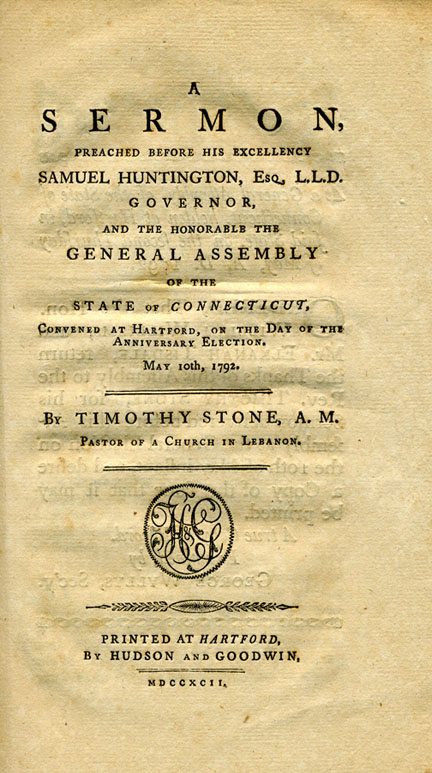

The public address may now be respectfully presented to his Honor the LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR (for more information see note #3), the COUNCIL, and HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.

HONORED GENTLEMEN:

The trust which God and this respectable Csommonwealth have reposed in you is truly important. All the temporal interests of this people, in a sense, are put into your hands and committed to your management for the general good. Children place strong confidence in the wisdom and tender care of their natural parents; so do this people in you, gentlemen, as their civil fathers. This confidence is not only implied but expressed in the designation of your persons to those offices which you hold in the government of your fellow citizens. Civil liberty is an inheritance descending from the Father of Lights, a talent which individuals may not despise or misimprove [abuse] without guilt: how vastly important, then, must this — with its connected blessings in society — be to a large community? The extensive views and patriotic feelings of wise and virtuous magistrates cannot fail deeply to impress their minds with the weight and solemnity of the trust reposed in them. Great anxiety for preferment betrays a weak mind or a vicious heart. Those only deserve the honors of an elevated station who are willing to bear the burdens and perform the duties which belong to it, and to reap the rewards which righteousness and benevolence will bestow; and who, in the ways of well doing, can meet with calmness the temporary ingratitude of a misguided misjudging people. Not that the preacher would be understood to mean that great esteem with an ample pecuniary recompense are not due to those whose time and superior talents are employed in promoting the happiness of their fellow men.

You gentlemen are vested with an authority which men of wisdom and virtue will ever revere — which properly exercised, none can resist without resisting the ordinance of God [Romans 13:2], and persevering in their resistance “must receive to themselves damnation” [Romans 13:2]. May you ever exercise such authority in the meekness of wisdom for the best good of your brethren agreeably to those unchangeable laws of righteousness and goodness which the Supreme Lawgiver hath established in His moral kingdom. (Ecclesiastes 3:16, Psalms 101:6): “That no iniquity, be found in the place of righteousness, or wickedness in the place of judgment [Ecclesiastes 3:16]; Your eyes will be upon the faithful of the land that they may dwell with You — those who walk in the perfect way [Psalms 101:6],” will be designated by you for all important executive trusts.

Viewing yourselves in the light of truth as the ministers of God to this people for good [Romans 13:4], you will realize the important connection between the moral government of Jehovah and those inferior governments which He hath ordained to exist among men. In this light, you will esteem it your highest glory to manifest a personal, supreme regard to the benevolent institutions of the Son of God. By the weight of your example and the force of all that influence you possess, you will study to commend His holy religion to all men that you may be instrumental in promoting the temporal peace and eternal happiness of this people. Public sentiments have a vast influence upon the conduct of mankind; public sentiments receive their complexion from public men; the rulers of a people can do more than some may imagine, to promote real godliness. If this is recommended in their conversation and exemplified in their lives, it will attract the attention of multitudes; it may lead some to a happy imitation and will not fail to give strong support to all the friends of God. But men sufficiently disposed at all times to cast off the fear of God, need slender aid from public influential characters to become professed advocates, for infidelity and licentiousness. How exceedingly interesting, gentlemen, to yourselves and the community is the station assigned you in providence! May unerring wisdom guide all your steps and the God of Abraham be your shield and exceeding great reward [Genesis 15:1].

The MINISTERS OF GOD’S SANCTUARYS will accept some thoughts addressed to them, not indeed for their instruction but to “stir up their pure minds by way of remembrance” [2 Peter 3:1].

REVEREND FATHERS AND BRETHREN:

Our character as Christians obligeth us to be righteousness before God [Romans 6:13], walking in all the commandments and ordinances of the Lord blameless [Luke 1:6], not forgetting that of civil magistracy as one of the wise and gracious appointments of heaven which, rightly improved, will extend its happy influence beyond the present life. And our office as ministers calleth us to exhort all the disciples of Jesus that they “submit themselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake: unto kings and governors as unto them that are sent by him for the punishment of evil doers and for the praise of them that do well. For so is the will of God, that with well doing ye may yet put to silence the ignorance of foolish men” [1 Peter 2:13-15]. The ignorance and folly of that principle that there is no connection between religion and civil policy is most happily refuted when the followers of Jesus act in character and demonstrate to the world that real Christians are the best members of society in every station. We are not then acting out of character when pointing out the advantages of a righteous government and the necessity of subjection to magistrates. This, however, is not the principal object of our ministry: our wisdom and understanding will eminently appear in converting sinners from the error of their ways — in winning souls to Christ. To effect which, our speech and our preaching must not be with enticing words of man’s wisdom but in demonstration of the spirit and of power [1 Corinthians 2:4].

Confiding in the unerring wisdom and boundless goodness of God, we need not be ashamed nor afraid to declare all His counsel [Romans 1:16 & Acts 20:27], being well assured that no doctrine or duty can be found in His revealed will but such as are profitable for men to believe and practice. The great comprehensive design of the Christian ministry is the glory of God in the salvation of sinners through Jesus Christ. In pursuing this noble all important design, we shall labor to exhibit the divine excellency of the Christian religion in the holiness of our lives and conversation as well as in the simplicity and uncorruptedness of our doctrines – that our example and our preaching may unite in their tendency to persuade sinners to become reconciled to God. “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings: that publisheth peace, that saith unto Zion, thy God reigneth!” and how is this beauty increased when the spiritual watchmen upon the walls of Zion, “sing together with the voice, and see eye to eye.” (Isaiah 53:7, 8).

That this beauty may appear and shine in all the ministers and churches of Christ, let us become more fervent and united in supplications to our Father in Heaven that He may shed forth plentiful effusions [outpourings] of that spirit of love and of a sound mind [2 Timothy 1:7] which is the only abiding principle of union between moral beings. Under the influence of this Holy Spirit. Under the influence of this Holy Spirit, awakened to activity and renewed diligence by the repeated instances of mortality among the ministering servants of God in the past year, may we all pursue the sacred work assigned us with increasing joy and success until called from our labors to receive the free rewards of faithful servants in the kingdom of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

A brief address to the numerous AUDIENCE present on this joyful anniversary will close this discourse.

BRETHREN & FELLOW CITIZENS:

Let us not vainly boast in our truly happy constitution nor in the number of wise and pious personages whom God hath called to preside in its administration. We have abundant occasion indeed to bless and praise the God of Heaven for all our distinguishing privileges, both civil and religious. Few of our lapsed race [ancestors] enjoy immunities [freedoms] equal to those which we possess, but we do well to remember that profaneness and irreligion, infidelity and ungodliness, when connected with such advantages will exceedingly enhance the guilt of men, and without repentance will awfully increase the pains of damnation. Would we become a wise understanding people, we must learn the statutes and judgments which the Lord our God hath commanded, and obey them – we must be a religious, holy people, “for without holiness, no man shall see the Lord” [Hebrews 12:14]. Let all be exhorted to become wise to salvation through faith, which is in Christ Jesus [2 Corinthians 3:15]. Amen!

Endnotes

1.Governor Samuel Huntington (1731-1796) was the son of a Puritan farmer, and early entered the study of law. After being admitted to the bar, Huntington married the daughter of a local minister, was elected to the State Assembly, and became a judge. He was sent by his State as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress where he signed the Declaration of Independence. He continued his service in the national Congress and in fact became the President of Congress. After the Revolution, Huntington served as a judge, Lt. Governor, and then ten terms as Governor.

2.Previous leaders of Connecticut who were “wise religious governors” of “eminent talents and pious examples” were numerous. For example, leaders of this description before Connecticut became an independent State included Puritan John Haynes, governor in 1639, followed by governors such as George Wyllys, William Leete, Robert Treat, Gurdon Staltonstall, and Roger Wolcott, all of whom were not only zealous in defending the liberties of the people but who also were often ministers of the Gospel or active in religious work. (Occasional governors during this period interspersed among this group were not religious and sometimes were even hostile to religion, but they were few compared to the rest.)

During the movement toward American independence, Connecticut’s governor was Jonathan Trumbull, Sr. (1710-1785). Trumbull was a minister of the Gospel, entered business, became an attorney, and was elected to the State assembly twenty-two times and became its Speaker. He later became a judge, and in 1765 resigned from office rather than take the British oath to uphold the odious Stamp In 1769, he was appointed by the Crown as Governor, but following the announcement of the separation of America from Great Britain, Trumbull threw all his influence to the patriot cause, becoming the only crown-appointed Governor to support American independence. Trumbull became the closest and perhaps most trusted confidant of General George Washington (who called him “Brother Jonathan”) and Trumbull did more to supply the Continental Army with food, supplies, munitions, and troops than any other Governor. In fact, as he initially rallied Connecticut citizens to defend their country, he addressed the assembled men, and implored them, “March on! This shall be your warrant: May the God of the armies of Israel be your leader!” Trumbull was reelected Governor fourteen times, presided over the State throughout the entirety of the Revolution, and at the close of the conflict, resigned the governorship to return to the study of theology.

Afterward the Revolution, Connecticut was again blessed with strong God-fearing governors, including Jonathan Trumbull, Jr., and the governor at the time of this sermon, Samuel Huntington.

3.The Lieutenant Governor at this time was Oliver Wolcott (1726-1797). Wolcott was commissioned as a British military officer in the 1740s to defend the frontier against attacks until a treaty was finally reached with the Indians. He then entered the study of medicine and was also elected county sheriff. In 1774, he became a part of the State governing council and served in this responsibility until after the American Revolution. In 1775, he renewed his military service of three decades earlier, only this time against Great Britain, and tore down a large statue of George III that had been erected in 1770, melting the material into bullets for the patriots. In 1776, he was elected to the Continental Congress where he signed the Declaration of Independence. He thereafter commanded several military regiments in the defense of New York and assisted in the first major American victory of the Revolution at Saratoga. Throughout the remainder of the Revolution he divided his time between Congress and military service, attaining the rank of Major General. Following the Revolution, in 1786 he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Connecticut and held that post until elected Governor in 1796. Interestingly, Oliver Wolcott’s father, Roger, had served as State governor, and then Oliver’s son later served as governor.

(1731-1820) Biography:

(1731-1820) Biography: