Simeon Howard (1733-1804) Biography:

Howard was born in Bridgewater, Maine. (Maine was considered a part of Massachusetts until becoming a separate state in 1820.) After graduating from Harvard at the age of twenty-five, he earned his living as a teacher until entering the study of theology. He took his first pastorate in Canada (Cumberland, Nova Scotia), leaving in 1765 to pursue a graduate degree at Harvard. In 1767 when he took the pastorate of West Church in Boston, the town was the epicenter of events leading up to the American War for Independence. When the British turned private homes in Boston into barracks, Howard and many of his parishioners fled to Nova Scotia for safety. Upon their return eighteen months later, they found the remainder of the congregation had largely fled, leaving only three families. He rebuilt the church over succeeding years, and was greatly respected in the community. In addition to his ministry work, Howard was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Society for Propagating the Gospel, and he also served as Vice-President of the Humane Society.

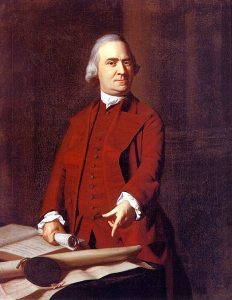

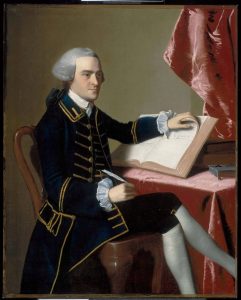

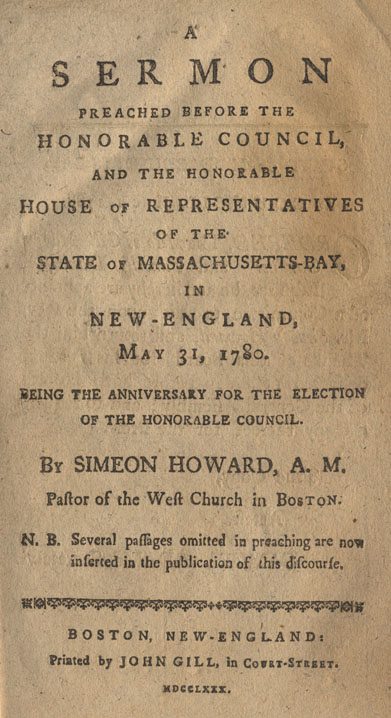

Many of his sermons were published, including this one, preached before the Legislature of Massachusetts. Significantly, the constitution of Massachusetts had been written shortly before this sermon, and it was ratified and went into effect the month after. (The 1780 Massachusetts Constitution is still in effect today, being the only constitution older than the US Constitution.) The first governor under the constitution was John Hancock, and the first lieutenant governor was Samuel Adams.

SERMON

PREACHED BEFORE THE

HONORABLE COUNCIL,

AND THE HONORABLE

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

OF THE

STATE OF MASSACHUSETTS-BAY,

IN

NEW-ENGLAND,

MAY 31, 1780.

BEING THE ANNIVERSARY FOR THE ELECTION

OF THE HONORABLE COUNCIL.

By SIMEON HOWARD, A. M.

Pastor of the West Church in Boston.

N. B. Several passages omitted in preaching are now

Inserted in the publication of this discourse.

STATE of MASSACHUSETTS-BAY.

In COUNCIL, June 1, 1780.

ORDERED, That Moses Gill, Henry Gardner and Timothy Danielson, Esquires, be and hereby are appointed a Committee to wait upon the Rev. Mr. Simeon Howard, and return him the Thanks of this Board, for his Sermon delivered Yesterday before both Houses of the General Assembly; and to request a Copy thereof for the Press.

True Copy,

Attest.

SAMUEL ADAMS, Secretary.

ELECTION SERMON.

EXODUS 18. 21.

–Thou shalt provide out of all the people, able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness; and place such over them to be rulers.

Almighty God who governs the world generally carries on the designs of his government by the instrumentality of subordinate agents; hereby giving scope and opportunity to his creatures to become his ministers for good to one another, in the exercise of the various powers and capacities with which he has endowed them. Tho’ for the vindication of his honor, to dispel the darkness and give a check to the idolatry and vice which overspread the world, and in order to prepare mankind for the reception of a Saviour to be manifested in due time, God was pleased to take the Jewish nation under his particular care and protection, and to become their political law-giver and head; yet he made use of the agency of some of that people in the administration of his government. The legislative power he seems to have reserved wholly to himself; there being no evidence that any of the rulers or assemblies of the people had authority to make laws. But the judicial and executive powers were entrusted with men. At the first institution of the government, Moses seems to have exercised the judicial authority wholly by himself. In this business he was employed from morning till evening, when Jethro, his father in law, the priest and prince of Midian came to visit him. This wise man, for such he surely was, observed to Moses, that this business was too heavy for him, and what he was not able to perform alone; and therefore advised him to appoint proper persons to bear the burthen with him, provided it was agreeable to the divine will. Moses it is said, in the context, hearkened to the voice of his father in law, and did all that he had said. There can be no doubt but that God approved this measure, tho’ it was first suggested y a pagan, otherwise it would not have been adopted. It seems indeed to have been highly expedient, and even necessary. From whence it appears, that even in this government which was so immediately the work of God, room was left for men to make such appointments and institutions, as by experience should be found necessary for the due administration of it. The general plan was laid by God, and he was the sole legislator. This was necessary in that age of darkness, idolatry and vice. Mankind seem to have been too ignorant and corrupt to form a constitution, and a code of laws, in any good measure adapted to promote their piety, virtue and happiness. But God left many smaller matters to be regulated by the wisdom and discretion of the people. This is agreeable to a general rule of the divine conduct; which is not to accomplish that, in a supernatural or miraculous way, which may be done by the exertion of human powers.

It is said, in the context, that in compliance with the advice of Jethro, Moses chose able men—and made them rulers. But it is generally supposed that they were chosen by the people. This is asserted by Josephus, and plainly intimated by Moses in his recapitulary discourse recorded in I Chap. of Deut. where he says to the people, “I spake unto you, saying I am not able to bear you myself alone—take ye wise men, and understanding, and known among your tribes, and I will make them rulers over you”. So that these officers were without doubt elected by the people, tho’ introduced byc Moses into their office. And indeed the Jews always exercised this right of choosing their own rulers; even Saul and David and all their successors in the throne, were made kings by the voice of the people. (see I Sam. 11, 15. 2 Sam. 2, 4, 5, 3.). This natural and important right, God never deprived them of, tho’ they had shewn so much folly and perverseness, in rejecting him, and desiring to have a king like the nations around them.

The business for which Jethro advised, that these rulers should be chosen was to decide the smaller and less difficult matters of controversy that arose among the people; while causes of greater consequence were to be brought before Moses: So that they were a fort of inferior judicial officers, or judges of inferior courts. Tho’ they were not officers of the highest dignity and authority in the state, yet the midianitish sage advised, that they should be “able men, such as fear God, men of truth hating covetousness; judging that such men only were fit for the office. He has here in a few words pointed out to us what sort of men are proper to be put in authority, whether in an higher or lower station; for if such qualifications are necessary for this inferior office, they must surely be more so, for the higher and supreme offices in government. And the consideration of these qualifications, is what I principally intend in the following discourse: But before I enter upon this, I would give a little attention to two or three other points. Accordingly I shall consider,

I. The necessity of civil government to the happiness of mankind.

II. The right of the people to choose their own rulers.

III. The business of rulers in general.

These particulars being finished in a few words, I shall then,

IV. Particularly consider the qualifications pointed out in the text, as necessary for civil rulers.

After which, the subject will be applied to the present occasion.

I. Let us consider the necessity of civil government for the happiness of mankind. Men have in all ages and nations been induced by a sense of their wants and weaknesses, as well as by their love of society, to keep up some intercourse with one another. A man totally separated from his species, would be less able to provide for himself than almost any other creature. Some sort of society, some intercourse with other men is necessary to his happiness, if not to his very existence.

Suppose then a number of men living near together, and maintaining that intercourse which is necessary for the supply of their wants, but without any laws or government established among them by mutual consent; or in what is called a state of nature. In this state everyone has an equal right to liberty, and to do what he thinks proper. The love of liberty is natural to all: It appears the first, operates the most forceably and is extinguished the last of any of our passions. And this principle would lead every man to pursue and enjoy everything, to which he had an inclination. Several persons would no doubt desire and pursue the same thing, which only one could enjoy. Hence contests would arise; and, no one else having a right to interfere, they must be settled by the parties: But prejudice and self-love would render them partial judges, and probably prevent an amicable settlement; so that the dispute must at last be ended by the strongest arm; and thus the liberty of the weak would be destroyed by the power of the strong. Every unsuccessful competitor would think himself injured by another’s seizing that to which, in his own opinion, he had an equal right, and would endeavour to obtain compensation: This would provoke retaliation, and naturally lead on to an endless reciprocation of injuries. The injured who found himself unable to contend with his adversary, would call in the assistance of some more powerful combatant, to avenge his cause: The aggressor too would endeavour to strengthen himself for defence by associates; and thus parties would be formed for rapine, devestation, and murder; and the peaceful state of nature soon be exchanged for a number of little contending tyrannies, or for one successful one, that should swallow up all the rest. This would generally be the case where men should attempt to live without laws or government; nor can they any way secure themselves against all manner of violence and injuries from bad men, but by uniting together in society, agreeing upon some universal rules to be observed by all;–that controversies shall be determined, not by the parties concerned, but by disinterested judges, and according to established rules; that their determinations shall be enforced by the joint power of the whole community either in punishing the injurious or protecting the innocent. Man is not to be trusted with his unbounded love of liberty, unless it is under some other restraint, than what arises from his own reason or the law of God. These, in many instances, would make but a feeble resistance to his lust or avarice; and he would pursue his liberty to the destruction of his fellow creatures, if he was not restrained by human laws and punishment.

Let us next consider,

II. The right of the people to choose their own rulers.

No man is born a magistrate, or with a right to rule over his brethren. If this were the case, there must be some natural mark by which it might be known to whom this right belongs, or it could answer no end: But no man was ever known to come into the world with any such mark of superiority and domination. If a man by the improvement of his reason and moral powers becomes more wise and virtuous than his brethren, this renders him better qualified for authority than others: But still he is no magistrate or lawgiver, till he is appointed such by the people.

Nor has one state or kingdom a right to appoint rulers for another. This would infer such a natural inequality in mankind as is inconsistent with the equal freedom of all. One state may indeed by virtue of its superior power assume this right; and the weaker state may be obliged to submit to it, for want of power to resist. But it is an unjust encroachment upon their liberty, which they ought to get rid of as soon as they can: It is a mark of tyranny on one side, and of inglorious slavery on the other.

The magistrate is properly the trustee of the people: He can have no just power but what he receives from them. To them he ought to be accountable for the use he makes of this power. But if a man may be invested with the power of government, which is the united power of the community, without their consent, how can they call him to account; what check can they have upon him; or what security for the enjoyment of anything which he may see fit to deprive them of? They must in this case be slaves: But as every people have a right to be free, they must have a right of choosing their own rulers and appointing such as they think most proper; because this right is so essential to liberty, that the moment a people are deprived of it, they cease to be free. This, as has been already observed, is a right which the Jews always enjoyed; they elected their kings, generals, judges and other officers; tho’ in some few instances God did expressly point out to them the person whom they ought to choose; which however, he has never done to any other people.

Let us now consider,

III. The business of rulers in general.

And this is, to promote and secure the happiness of the whole community. For this end only they are invested with power, and only for this end it ought to be employed. The apostle tells us, that the magistrate is God’s minister for good to the people. This is the sole end for which God has ordained, that magistrates should be appointed, that they may carry on his benevolent purposes, in promoting the good and happiness of human society; and hence their power is said to be from God; that is, it is so, while they employ it according to his will. But when they act against the good of society, they cannot be said to act by authority from God, any more, than a servant can be said to act by his master’s authority, while he acts directly contrary to his will. And no people, we may presume, ever elected a magistrate for any other end, than their own good; consequently when a magistrate acts against this end, he cannot act by authority from the people; so that he acts, in this case, without any authority either from God or man. He cannot by any lawful authority act against, but only for the good of society. This in general is the business of civil rulers: But there are a variety of ways and means by which they are to carry on this business and accomplish the important end of their institution, which it is quite beyond my present design particularly to point out, tho’ there may be occasion to suggest some of them in the progress of my discourse.

Let us now consider,

IV. The qualifications pointed out in the text, as necessary for rulers.

I. They must be able men. God has made a great difference in men in respect of their natural powers both of body and mind: To some he has given more, to others fewer talents. Nor is there perhaps a less difference in this respect, arising from education. And tho’ there are none but what may be good members of civil society as well as faithful servants of God; yet everyone has not abilities sufficient to make him a good civil ruler. Woe unto thee, O land, when thy king is a child, says Solomon; hereby intimating that the happiness of a people depends greatly upon the character of its rulers, and that if they resemble children in weakness, ignorance, credulity, fickleness, &c. the people will of course be very miserable. By able men may be intended men of good understanding and knowledge; men of clear heads, who have improved their minds by exercise, acquired an habit of reasoning, and furnished themselves with a good degree of knowledge: Men who have a just conception of the nature and end of government in general, of the natural rights of mankind, of the nature and importance of civil and religious liberty; a knowledge of human nature; of the springs of action and the readiest way to engage and influence the heart; an acquaintance with the people to be governed, their genius, their prejudices, their interest with respect to other states, what difficulties they are under, what dangers they are liable to, and what they are able to bear and do. These things are ever to be taken into consideration by legislators, when they make laws for the internal police of a people, and in their transactions with, or respecting other states. It would be going too far to say, that an honest man cannot be a good ruler, unless he be of the first character for good sense, learning and knowledge; but it will not be denied, that the more he excels in these things, the more likely he will be to rule well: He will be better able to see what measures are suited to the temper and genius of the people, and most conducive to the end of his institution; how to raise necessary supplies for the expenses of government in ways most easy and agreeable to the people; how to extricate them out of difficulties in which they may be involved; how to negotiate the calamities of war, by compromising differences or putting the people into a condition to defend themselves and repel injuries: In a word, how to render them happy and respectable in peace, or formidable in war. These things require a very considerable degree of penetration and knowledge.

As it is of great importance to the community, that learning and knowledge be diffused among the people in general, it is proper that the government should take all proper measures for this purpose; making provision for the establishment and support of literary schools and colleges: But ignorant and illiterate men will not be likely to be the patrons of learning; unacquainted with its excellency and importance, and seeing no comeliness or beauty in it; they will reject and despise it, as the Jews did the great teacher of wisdom who came from God. It would not be strange if such men entrusted with the government of a people should wholly neglect to make any provision for the encouragement of literature. It is therefore proper that rulers should be men of understanding and learning, in order to their being disposed to give due encouragement and support to the teachers and professors of the liberal arts and sciences.

It may be further observed, that weak and illiterate men at the head of a government, will be likely to place, in inferior and subordinate offices, men of their own character, merely because they know no better.

But by able men, may be intended men of courage, of firmness and resolution of mind: Men that will not sink into despondency at the sight of difficulties, or desert their duty at the approach of danger; men that will hazard their lives in defence of the public, either against internal sedition or external enemies, that will not fear the resentment of turbulent, factious men; that will be a terror to evil doers, however powerful, and a protection to the innocent, however weak:–Men that will decide seasonably upon matters of importance and firmly abide by their decision, not wavering with every wind that blows. There are some men that will halt between two opinions and hesitate so long, when any question of consequence is before them, and are so easily shaken from their purpose, when they have formed one, that they are on this account very unfit to be entrusted with public authority. Such double-minded men will be unstable in all their ways; their indecision in council will produce none but feeble and ineffectual exertions. And this doubting and wavering in the supreme authority must be prejudicial to the state, and, at some critical times, may be attended with fatal consequences. Wise men will not indeed determine rashly but when the case requires it, they will resolve speedily, and act with vigor and steadiness.

By able men may be further intended men capable of enduring the burden and fatigue of government; men that have not broken or debilitated their bodies or minds, by the effeminating pleasures of luxury, intemperance or dissipation. The supreme government of a people is always a burden of great weight, tho’ more difficult at some times, than others. It cannot be managed well without great diligence and application. Weak and effeminate persons are therefore by no means fit to manage it. But rulers should not only be able men, but

2. Such as fear God. The fear of God, in the language of scripture, does not intend a slavish, superstitious dread, as of an almighty, arbitrary and cruel Being; but that just reverence and awe of him, which naturally arises from a belief and habitual consideration of his glorious perfections and providence; of his being the moral governor of the world, a lover of holiness and a hater of vice, who sees every thought and design, as well as every action of all his creatures, and will punish the impenitently vicious and reward the virtuous: It is therefore a feat of offending him productive of obedience to his laws, and ever accompanied with hope in his mercy and that filial love which is due to so amiable a character.

It is of great importance that civil rulers be possessed of this principle. It must be obvious to all, that a practical regard to the rules of social virtue is necessary to the character of a good magistrate. Without this, a man is unworthy of any trust or confidence. But no principle so effectually promotes and establishes this regard to virtue, as the fear of God. A man may indeed from a regard to the intrinsic amiableness and excellency of virtue, from a mere sense of honor, from a love of same, from a natural benevolence of temper, or from a prudent regard to his own temporal happiness, follow virtue, when he is under no strong temptation to the contrary. But suppose him in a situation, where he apprehends that temporal infamy and misery will be the certain consequence of his practicing virtue, and temporal honor and happiness the consequence of his forsaking it, without any regard to God, as his ruler and judge, and can we expect that he will adhere to his duty? Will he sacrifice everything dear in this life, in the cause of virtue, when he has no expectation of any reward for it, beyond the grave? Will he deny himself a present gratification, without any prospect of being repaid either here or hereafter? Will he expose himself to reproach, poverty and death for the sake of doing good to mankind, without any regard to God, as the rewarder of virtue or punisher of vice? This is not to be expected. We all love, and we ought to love ourselves, and all wish to be happy. Why then should a man give up present ease and happiness for suffering and death, in the cause of virtue, if he has no expectation that God will reward virtue? This would be acting against the principle of self-love, which is generally too powerful to be counteracted.

But suppose a man to be habitually under the influence of this principle, that is, to believe and duly consider God, as his ruler and judge, who will hereafter reward virtue and punish vice with happiness and misery respectively, unspeakably greater than any to be enjoyed or suffered in this world, and he may then upon rational principles and in consistency with his self-love, forego the greatest temporal good, and expose himself to the greatest temporal evil, in the cause of virtue, and we may reasonably expect that he will. Virtue will be his chief good: He will be attached to it, as to his very being, with all the strength and ardor of his love and desire of happiness. The fear of God therefore is the most effectual, and the only sure support of virtue in the world.

Men invested with civil power are not to be sure less, but generally much more exposed to temptations to violate their duty than other men: They have more frequent opportunities of committing injuries; and may do it with less fear of present punishment; and therefore stand in need of every possible restraint to keep them from abusing their power, by deviating into the paths of vice.

It is further to be considered, that the practice of piety, which is comprised in the fear of God, has a powerful tendency to enoble and dignify the mind and beget in it an abhorrence of everything mean and base; to inspire a magnanimity and fortitude of spirit that will support and carry it thro’ the greatest dangers and difficulties; to refine and purify the heart, to disengage it from the vanities of the world, and beget that good will and benevolence which are the brightest part of a virtuous character. Contemplating daily the perfections of the Deity, as displayed in the creation, government and redemption of the world, must naturally tend to exalt the affections and fix them upon divine things, to make us love and desire to imitate the moral character of God; and consequently to weaken the force of those lusts which are so apt to draw men aside and entice them into sin;–to enliven every principle of virtue, and make us perfect, even as our father in heaven is perfect.

It is also to be observed, that the human mind is liable to mistake and err, that circumstances often occur, especially to those who are concerned in government, in which more wisdom is necessary than they are possessed of, even though they may be able men. In such cases we are directed to look up to God, the original and inexhaustible source of wisdom. Nor have we any reason to suspect that such applications will be in vain. God perfectly knows the human mind, and all the ways in which its views and determinations can be influenced: And he may without infringing upon its moral liberty, by a powerful, though imperceptible operation, put it into such a train of thinking, as may give it a juster view, and lead it to a wiser determination, than it would otherwise have formed. Here is, I apprehend, nothing in this supposition, inconsistent with the principles of rational theology and natural religion. Nor without supposing that God does thus interpose, is it easy to conceive how that part of the divine government which is in the hands of civil rulers, should in all cases be adapted to the various circumstances of particular persons. But there is little reason to think that this light and direction will be granted to men who have no fear of God before their eyes; because though they lack wisdom, they will not ask it of God, who giveth to all men liberally and upbraideth not. And rulers being without this divine counsel, it will not be strange, if, merely for this reason, their conduct is wrong, and ill-judged, calculated in many instances, not for the good, but the hurt of the people; and it may be, at a critical time, for their utter destruction.

There can be no doubt, but God often brings distress and ruin upon a sinful people, through the ill-management of their rulers, given up to error and blindness. In the 19th chapter of Isaiah we have a prophesy of the overthrow of the kingdom of Egypt. And the infatuation of their rulers is mentioned as one of the immediate causes of this calamity. “The spirit of Egypt,” says God, “shall fail; and I will destroy the counsel thereof.” It is afterwards added, “Surely the princes of Zoan are fools, the counsel of the wise counselors of Pharoah is become brutish.” And in the 29th chapter of the same book, God threatens his own people, that for their hypocrisy and other wickedness, “the wisdom of their wise men shall perish, and the understanding of their prudent men shall be hid.” In the same way, is reasonable to suppose, God often brings his judgments upon other nations. And therefore if a people desire to have rulers of wise and understanding hearts, counseled and directed by heaven, they should take care, that they be men who fear God.

Let me observe once more, that it is of great importance to their happiness, that religion and virtue generally prevail among a people; and in order to this, government should use its influence to promote them. Rulers should encourage them not only by their example, but by their authority; and the people should invest them with power to do this, so far as is consistent with the sacred and unalienable rights of conscience; which no man is supposed to give up, or may lawfully give up, when he enters into society. But reserving these, the people may, and ought to give up every right and power, which will enable him more effectually to promote the common good, without putting it in his power essentially to injure it. He ought therefore to have power to punish all open acts of profanes and impiety, as tending by way of example to destroy that reverence of God which is the only effectual support of moral virtue; and all open acts of vice, as prejudicial to society: He should have power to provide for the institution and support of the public worship of God, and public teachers of religion and virtue, in order to maintain in the minds of the people that reverence of God, and that sense of moral obligation, without which there can be no confidence, no peace or happiness in society.

Without such care in government, there is danger that the people will forget the God that is above, and abandon themselves to vice; or, to say the least, impiety and vice are much less likely to become general, where such care is taken, than where it is not. And God having in the constitution of nature made religion and virtue conducive, and even necessary to the happiness of human society, he has thereby plainly taught us, that it is the duty and business of society as such, or of the civil magistrate to do everything to promote them, that may be done without injuring the rights of conscience. And no man who has full liberty of inquiring and examining for himself, of openly publishing and professing his religious sentiments, and of worshipping God in the time and manner which he chooses, without being obliged to make any religious professions, or attend any religious worship contrary to his sentiments, can justly complain that his rights of conscience are infringed. And such liberty and freedom every man may enjoy, who’ the government should require him to pay his proportion towards supporting public teachers of religion and morality.

Taking this care of religion appears to be so plain and important a duty, that the government which should wholly neglect it, would not only act a very unwise and imprudent part with respect to themselves; but be guilty of base ingratitude and a daring affront to heaven. By such conduct they would, as a community, in effect adopt the language of the profane fatalists mentioned by Job, who “say unto God, depart from us; for we desire not the knowledge of thy ways. What is the Almighty that we should serve him? And what profit shall we have it we pray unto him?” Now altho’ it is possible, that rulers who have no religion themselves, may enact proper laws to support it among the people, yet it is to be remembered, that their example will have great influence, and, if that be irreligious and vicious, will, in some measure, defeat the good effects of their authority, and do more to spread corruption, than that will to prevent it. It is therefore highly proper in order to promote piety and good morals among the people, that rulers be men who fear God; who have a just sense of religion on their own minds, and conform to it in their lives.

It may be proper to add, that though the fear of God may exist, where there is no knowledge or belief of Christianity; yet that the scheme of doctrines contained in the gospel, is much better calculated than any other known to the world, to produce and strengthen that divine principle. The plan of redemption which it unfolds for the fallen race of men, exhibits the Deity in the most amiable light, as the perfection of love and benevolence: “The solemn scenes which it opens beyond the grave; the resurrection of the dead; the general judgment; the equal distribution of rewards and punishments to the good and bad; and the full completion of divine wisdom and goodness, in the final establishment of order, perfection and happiness,” afford such motives to the love and reverence of God, and to the practice of all holiness and virtue, as can be drawn from no other scheme of religion: And therefore a belief of the gospel of Christ may justly be considered, as an important qualification for a civil ruler.

I might observe further under this particular, that impious, immoral men at the head of government, and having authority to appoint subordinate officers, will probably make choice of men of their own character, and in this way be a means of spreading corruption, and of much injury to society: But I must pass on to consider another qualification of rulers. For

III. They must be men of truth.

This means men free from deceit and hypocrisy, guile and falsehood: Men who will not by flattery and cajoling, by falsehood, and slandering a competitor endeavor to get into authority: And who when they are in, will conscientiously speak the truth in all their declarations and promises, and punctually fulfill all their engagements.

In treating with other states, they will act with the same integrity which honest men do in their private affairs, and promise nothing but what they intend, and think they shall be able to perform. Engagements already made to other powers, they will honestly endeavor to fulfill, so far as it belongs to their department, without seeking or pretending a cause for failure, when no such cause exists.

They will shew the same integrity and fidelity in their conduct towards individuals. They will not promise to anyone, what they have reason to think they cannot, or do not intend to perform. Promises of government already made, the execution of which belongs to them, they will look upon themselves bound to fulfill, if possible, that no man may be a sufferer by confiding in the public faith.

Civil rulers generally bind themselves expressly, and always implicitly by accepting their office, faithfully to discharge the duties of it. And a man of truth will pay a sacred regard to this engagement. He will not content himself with receiving the honors and emoluments of his office, while he neglects the duties of it; considering, that he has solemnly bound himself to do this business, he will give the same care and attention to it, that a prudent man in a private station does to his own particular concerns. A man of truth will not undertake an office, for which he thinks himself incapable; because this would be promising to do, what he is conscious, he is incapable; because this would be promising to do, what he is conscious, he is of doing; nor will he be instrumental of appointing others to offices, for which he thinks them unqualified; this would be acting falsely; because by the appointment he declares, that he thinks them qualified. Having solemnly engaged to use his power for the public good, he will never employ it in encouraging and supporting the enemies of his country, or to carry on, under the mask of patriotism, measures to promote his own selfish and private views, or to screen and protect from public justice, offenders against society. He will not employ his abilities to impose upon the understandings of others, and make the worse appear the better reason, in order to disguise truth, and pervert justice. He will not suffer one man, or one part of the community to be injured and robbed by another, when his office enables him to prevent it; because this would be violating his promise. In a word, he will to his utmost endeavor to answer the end of his institution by performing the duties of his station, and manifest by all his conduct that he is an honest, upright man. He will make no false pretences, he will put on no false appearances, but ever act with Christian simplicity, and godly sincerity.

Such will be the conduct of men of truth: And such men only are proper to be entrusted with authority over a free people. Rulers of this character will be honored, beloved and confided in by their countrymen, and respected by other nations; their subjects will be easy and happy, united together in the bonds of truth and love, and by their union able to defend themselves against invaders; their government resting on the basis of truth and justice, will be firm and stable, revered and honoured both at home and abroad. Whereas that deceit and hypocrisy, that falsehood and insincerity, that dissimulation and craftiness, which have so often dictated the measures of government in most of the nations of the earth, and which are expressly recommended to rulers by Machiavelli, and inculcated among other immoralities, as necessary parts of a good education, in the celebrated and much admired letters of a late British nobleman to his son, 1 however they may sometimes succeed and procure some temporary advantages, will almost always weaken and disgrace the government which practices them, 2 by sapping the foundation of public credit, producing uneasy jealousies, disaffection, divisions and contempt of authority among the people, and leading them by example to the practice of the same insincerity, falsehood and dishonesty towards one another, which they see in their rulers; and by rendering them infamous in the eyes of other nations, and perhaps raising up enemies to punish their perfidy.

And it may without doubt e asserted with truth, upon the principles both of natural religion and revelation, that that government, which is directed by truth and integrity, will bid the fairest to secure and promote the happiness of the community, however contrary this assertion may be to the principles and practices of modern courtiers and politicians. But I must proceed to the other qualification of a good ruler, mentioned in the text which is

4. Hating covetousness. Covetousness, you all know, is an inordinate desire of riches; such a desire as will make a man pursue them by unlawful means, and prevent his using them in a right manner. Hating covetousness is a strong expression to denote a freedom from this vicious temper, and a sense of its unreasonableness and turpitude.

That it is of great importance that civil rulers have this qualification will be evident upon a little reflection.

Covetousness is a fruitful source of corruption. A man governed by this appetite will be guilty of any enormity for the sake of gratifying it. “They that will be rich, fall into temptation and a snare, and into many foolish and hurtful lusts which drown men in destruction and perdition: For the love of money is the root of all evil.” Almost all the oppression, fraud and violence that has been done under the sun, has owed its rise and progress to covetousness. The indulgence of this vice debases the mind, and renders it incapable of anything generous and noble, contracts its views, destroys the principles of benevolence, friendship and patriotism, and gives a tincture of selfishness to all its sentiments: It hardens the heart and makes it deaf to the cries of distress and the dictates of charity; it blinds and perverts the judgment and disposes it to confound truth and falsehood, right and wrong.

A civil ruler under the direction of this principle will oppress and defraud his subjects, whenever he has it in his power; he will neglect the duties of his office, whenever he can promote his private interest by the neglect; he will enact laws to serve himself, not the community, and he will enact none that he thinks would be prejudicial to his private interest, however beneficial they might be to the public, however necessary for the support of justice and equity between man and man; he will pervert justice and rob the innocent for bribes; he will discourage every measure that would occasion expense to himself, however salutary to his country; rather than part with his money, he will see the arts and sciences, which are so ornamental and friendly to a community, languish, erudition starve, and the rising genius which promised glory to his country, nipt in the bud by the cold hand of poverty; yea religion itself, the greatest honor and blessing of society, he will see languish and die, rather than impart anything to support its cause; and having long looked upon riches in the same light that good men do upon religion, as his chief good, and feeling the same attachment to them which they do to that, he may, if required, by laws already made, to pay anything for its support, absurdly plead, that it is against his conscience; supposing, with those corrupters of religion mentioned by the apostle, “that gain is Godliness.” If he has a voice in the appointment of subordinate officers, he will sell his vote to the highest bidder, and appoint such as will be most subservient to his private interest, however unqualified for the office: In a word, all his conduct, all his reasoning and votes will be tinctured by his selfish spirit; and in a critical time when great expense is necessary for the public safety, he may by his parsimony be a means of the ruin of his country.

But a ruler who hates covetousness will conduct in a very different manner.—He will never oppress or wrong the community; the public interest will be always safe in his hands; he will freely expend his time and his estate, in discharging the duties of his office for the good of his country; he will be ever ready to promote good laws, tho’ they deprive him of opportunities of making gain, and involve him in expense; he will devise liberal things, and cheerfully bear his part in the expense necessary to carry on every measure, that promises advantage to his country; he will do all in his power to promote the liberal arts and sciences, manufactures and all useful inventions, to encourage men of learning and genius, and to aid the cause of religion and virtue: In promoting men to places of trust, he will be influenced by no selfish, private views, but by a regard to the public good; no bribe will purchase his vote for an unfit man, and hating covetousness himself, no consideration will induce him to give it for a sordid, avaricious wretch; he will neglect no measures necessary for the public safety and happiness, for fear of parting with his money. In fine, all his conduct will bear the marks of his nobleness and liberality of sentiment, of his disinterestedness and public spirit.

I have now considered the several qualifications of a good ruler mentioned in the text: And they all appear necessary to form that character, whether in the legislative, executive or judicial department: Nor is it easy to say in which, they are most necessary; tho’ it is not difficult to see, that the want of any one of them in either, must be prejudicial and dangerous to the community.

I must now make some reflections upon the subject, and apply it to the present occasion. And

1. What has been said of the necessity of government for the peace and happiness of mankind, may lead us to reflect with shame upon the selfishness and corruption of our species, who, with all their rational and moral powers, can no otherwise be kept from injuring and destroying one another, than by superior force, or the fear of temporal sufferings and punishment; and with whom you are no longer safe, than it is unsafe for them to hurt you. This is a very humiliating consideration: And, so far as we know, there is no other order of creatures thro’ out the boundless universe, who, if left to their natural liberty would be so mischievous to one another as men.

2. This may also lead us to reflect with pleasure and gratitude to God, upon the steps which have been taken by this people to frame a new constitution of government; and that a plan has been formed which appears in general so well calculated to guard the rights and liberties, and promote the happiness of society; and which it is to be hoped will soon be the foundation of our government, instead of that antiquated insecure basis upon which it now rests.

3. We may likewise see from what has been said, how much it is the duty and interest of a people to pay due submission to the orders of government, and to endeavour unitedly to support its authority. Both rulers and subjects are perhaps too apt to consider their respective interests as distinct and separate: Whereas they are in truth one and the same,–the prosperity and happiness of the whole community. Everything done by subjects in obedience to, and support of, the just authority of government is conducive to their own happiness; and everything done by governors, that is beneficial to the governed, is likewise so to themselves: And it is from the mutual endeavors of both to serve each other, that the prosperity of society must result. If rulers abuse their power, they may destroy the happiness of the community; but this may be done as effectually by the subjects refusing to obey and support the authority of government. Nor may any people expect to enjoy all the blessings of society, unless their government is preserved in due force and vigor.

4. We are reminded of the gratitude which we owe to God, that he has not permitted the natural and important right which every society has of electing its own rulers to be wrested out of our hands, as is the case in some other countries. Had Great Britain carried on, without opposition, the measures she was pursuing with us, we should probably in a little time have been wholly deprived of this privilege. She had already assumed an absolute right of appointing too branches of the legislature. These would have had the appointment of all judicial and military officers: And upon the same ground that she robbed us of the election of a Governor formerly, and of Counselors lately, she might have annihilated the House of Representatives; or if she had not done this in form, she might by bribery and corruption, have rendered that house a meer tool to the servants of the crown, as is the case in that country. It is therefore owing to the opposition which his people made to the measures of the British court, and to the blessing of God upon that opposition, that they have now a voice in appointing their own rulers; otherwise our government might now have been in the hands of the weakest and most profligate favourites of that corrupt and infatuated court.

5. We are reminded how much it is the duty and interest of a people, who are in the enjoyment of this right, to exercise it with prudence and integrity. The people’s appointing their own rulers will be no security for their good government and happiness, if they pay no regard to the character of the men they appoint. A dunce or a knave; a profligate or an avaricious worldling will not make a good magistrate, because he is elected by the people. To make this right of advantage to the community, due attention must be paid to the abilities and moral character of the candidate. This is a consideration that concerns this people at large, as all have a voice in the election of our rulers, either personally, or by their representatives. But upon this occasion it is proper to observe, that it especially concerns the members of the honorable Council and house of Representatives here present, by whom the counselors for the ensuing year are this day to be elected. And I shall not, I hope, be tho’t to go beyond my line of duty, if I say; that the electors ought not to give their votes at random, or from personal or private views. They act in this business in a public character, by virtue of power delegated to them by the people, to whom, as well as to God, the origin of all power, they are accountable for the use they make of it. Nor can they answer it to either, or even to their own consciences, if thro’ interested or party views, they advance to the Council Board, men unqualified for the important duties of that station. At such a critical time as the present, the want of wisdom or integrity in that house may be attended with the most fatal consequences. The advice of Jethro in the text, demands the consideration of all those who are to bear a part in the elections of this day. “Provide out of all the people, able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness.” There never was a time when such men were more necessary at that board than the present. Nor would I entertain an opinion so dishonorable to my country, as to suppose there are not such men in it; tho’ I cannot at the same time entertain an idea so flattering, as to suppose there are not many among us who fall far short of this character. It belongs to the present electors to distinguish, so far as they can, these characters, one from the other, and to give their votes only for the former. Whoever considers the part which this Board has in legislation, their authority in directing the military and naval force of the state, their being invested with the supreme executive power, and in some important cases with a supreme judicial power will be sensible, that great wisdom, integrity and fortitude are necessary for the right management of these powers. Should they be committed to men of small abilities and little knowledge; men unacquainted with the nature of government, and with the circumstances of this state; men void of integrity, of narrow, contracted views, governed by ambition, avarice or some other selfish passion; men of no fortitude and resolution, of dastardly effeminate spirits; should such men, I say, be entrusted with the great and important powers vested in the Council, what could be expected, but that their public conduct would bear the marks of their ignorance, weakness, effeminacy and selfishness, to the great injury and dishonor, if not to the ruin of the common wealth. And tho’ such men may be as fond of this station, as those who are best qualified for it, and perhaps much fonder, yet it would be so far from rendering them truly honourable, that it would only render them the more infamous, by bringing into public view their vices and defects; while the electors of such men, would fix an indelible stain upon their own characters, and inherit the curses of the present and future generations.

But men who have themselves been honored by the unbiased suffrages of their country, must surely be too wise and virtuous, thus to prostitute their votes; and it may, I hope, be taken for granted, that knowledge and integrity, the fear of God, and a public spirit, will govern in the ensuing election, and such men be raised to the Council Board as will do honor to that respectable station, to their electors and themselves.

I now beg leave, with all due deference and submission, to suggest a few things that may reasonably be expected of a General Court, composed of such men as the text describes, by the people who have invested them with this power and authority, And,

It may be expected, that they will give due attention to the public affairs committed to their care. By accepting a seat in either house, a man does, implicitly at least, solemnly engage to attend to the business, which is there to be transacted. Nor, do I see how he can with any propriety be called a man of truth, who after such engagement, neglects that business, for the sale of going to his farm, his merchandise or his pleasure. It appears to me, that such neglect argues great unfaithfulness in the delinquents, and it may be attended with very pernicious consequences. Individuals may and often do plead in excuse for this, that the business may be done without them: But they ought to remember, that everyone has an equal right to excuse himself by this plea, and if all should do so, the concerns of the public must be wholly neglected. But,

It may be justly expected that our civil rulers will take due care to provide for the public defence. Notwithstanding the great exertions we have already made, and the great things which God has done for us, we must still contend with the enemies of our rights and liberties, or become their abject slaves. And it depends, in a great measure, upon our public rulers under God, whether we shall contend with success, or not. It is by their seasonable and prudent measures that an army is to be provided and furnished with necessaries, to oppose the enemy. And it must be the wish of every true American, that nothing may be omitted which can be done to support and render successful so important a cause: a cause so just in the sight of God and man, which Heaven has so remarkably owned, and all wise and good men approved; a cause which not only directly involves in it the rights and liberties of America; but in which the happiness of mankind is so nearly concerned: For in this extensive light I have always considered the cause in which we are contending. Should our enemies finally prevail, and establish that absolute dominion over us, at which they aim, they would not only render us the most miserable of all nations, but probably be able by the riches and forces of America to triumph over the arms of France and Spain, and carry their conquests to every corner of the globe; nor can we doubt, but that they would carry them, wherever there was wealth to tempt the enterprise: The noble spirit of liberty which has arisen in Ireland would be instantly crushed, and the brave men, who have appeared foremost in its support, be rewarded with an ax or a halter: The few advocates for this suffering cause in Britain would be hunted and persecuted as enemies to government, and be obliged in despair to abandon her interest: And in every country where this event should be known, the friends of liberty would be disheartened, and seeing her in the power of her enemies, forsake her, as the disciples of Christ did their master. So that our being subdued to the will of our enemies, might in its consequences be the banishment of liberty from among mankind. The heaven-born virgin seeing her votaries slain, her altars o’er-thrown, and her temples demolished, and finding no safe habitation on earth, would be obliged like the great patron of liberty, the first-born of God, to ascend to her God and our God, her Father and our Father, from whom she was sent to bless mankind, leaving an ungrateful world, after she had like him, been “rejected and despised of men,” in slavery and misery, till with him she shall again descend to reign and triumph on earth. Such might be the consequence, should the arms of Britain triumph over us. Whereas, if America preserves her freedom, she will be an asylum for the oppressed and persecuted of every country; her example and success will encourage the friends, and rouse a spirit of liberty thro’ other nations; and will probably be the means of freedom and happiness to Ireland, and perhaps in time to Great-Britain and many other countries. So that our contest is not merely for our own families, friends, and posterity; but for the rights of humanity, for the civil and religious privileges of mankind. We have surely then a right to expect, that the government of this state will neglect no measure that is necessary on their part, to aid so interesting a cause, whatever difficulties or expense may attend it. And, I hope, it may with equal confidence be expected, that the people will cheerfully lend their arms, and bear the expense that may be required for so glorious a purpose. Great expense must without doubt be necessary to carry on our defense: But whoever is disposed on this account, to give up the dispute, proves himself totally unworthy of the liberty for which we are contending.

As the support, or rather the recovery of the public credit, is absolutely necessary to our having a respectable army in the field, as well as to our internal peace and prosperity; it may be expected that this government will not be wanting in any measure for this purpose, which wisdom and sound policy can suggest.

If by means of the depreciation of our paper currency, and any law of this state, many persons have suffered, and are still liable to suffer great injury; if this injustice falls principally upon widows and fatherless children, and such others as are least able to support themselves under the loss, this surely is an evil that ought speedily to be redressed; and, if it be possible, compensation should be made to the sufferers, by those who have grown rich by this iniquity. And as the General Court of the last year, did with great justice make an allowance, for the depreciation of the currency, in fixing their own wages, and in some other instances, it may justly be expected that the honourable Court of this year, will go on the extend this justice to every part of the community and order the same allowance to be made in discharging all debts and contracts, however their private interest may be thereby affected.

The large taxes now levying and to be levied, make it peculiarly proper that great care should be taken in fixing the proportion which the different parts of the community are respectively to pay; and we have a right to expect, that our honoured fathers who are to guard the rights of the whole, will not require any particular parts to bear a greater proportion of this burden than is just, considering its ability and circumstances.

Liberty and learning are so friendly to each other, and so naturally thrive and flourish together, that we may justly expect, that the guardians of the former will not neglect the latter. The good education of children is a matter of great importance to the common-wealth. Youth is the time to plant the mind with the principles of virtue, truth and honor, the love of liberty and of their country; and to furnish it with all useful knowledge. And tho’ in this business much depends upon parents, guardians and masters, yet it is incumbent upon the government to make provision for schools, and all suitable means of instruction. Our College justly claims the patronage and assistance of the state, in return for the able men with which she has furnished the public; not to observe, that her present suffering and low state renders her an object of pity: By the well known depreciation, she, as well as many of her sons in the ministry, have lost a great part of their income; she and they having in this respect, had the same hard lot with widows and orphans. Nor will I suppose that we shall ever have a General Court, of so little love to their country, or so little sensible of the importance of literature to its virtue, liberty and happiness, so barbarous and savage, as to suffer her, or any of her family to languish in poverty, or to want what is necessary to their making a decent and honorable appearance.

If anything can be done by government to discourage prodigality and extravagance, vain and expensive amusements, and fantastic foppery, and to encourage the opposite virtues, we may reasonably hope it will not be neglected. The fondness of our countrymen, or, shall I say, country-women, for showy and useless ornaments and other articles of luxury, has been remarked by a gentleman in Europe, of great eminence for political wisdom, as very unbecoming our present circumstances. This is a folly that bodes ill to the public; and it must be the wish of every wise and good man, that it were laid aside. Men in authority, if they can do no more, may, at least discountenance it by their example; and this will not be without its good effect.

Finally, our political fathers will not fail, to do all they can, to promote religion and virtue through the community, as the surest means of rendering their government easy and happy to themselves and the people. For this purpose they will watch over their morals, with the same affectionate and tender care, that a pious and prudent parent watches over his children, and by all the methods which love to God and man can inspire, and wisdom point out, endeavor to check and suppress all impiety and vice, and lead the people to the practice of that righteousness which exalteth a nation. If any new laws are wanting, or more care in the execution of laws already made, for discouraging profanes, intemperance, lewdness, extravagant gaming, extortion, fraud, oppression or any other vice, they will take speedy care to supply this defect, and render themselves a terror to evil doers, as well as an encouragement to such as do well. They will promote to places of trust, men of piety, truth and benevolence. Nor will they fail to exhibit in their own lives, a fair example of that piety and virtue, which they wish to see practiced by the people: They will shew that they are not ashamed of the gospel of Christ, by paying due regard to his sacred institutions, and to all the laws of his kingdom. Magistrates may probably do more in this way, than in any other, and perhaps more than any other order of men, to preserve or recover the morals of a people. The manners of a court are peculiarly catching, and, like the blood in the heart, quickly flow to the most distant members of the body. If therefore rulers desires to see religion and virtue flourish in the community over which they preside, they must countenance and encourage them by their own example. And to excite them to this,

I must not omit to observe that tho’ the fear of God, a regard to truth and a hatred of covetousness, are necessary to form the character of a good ruler, they are, if possible, still more necessary to form the character of a good man, and secure the approbation of God, the Judge of all. For to him magistrates in common with other men are accountable. Nor does he regard the persons of princes any more than of their subjects. If they are impious and vicious, if they abuse their power, they may bring great misery upon other men, but they will surely bring much greater upon themselves. The eye of heaven surveys all their counsels, designs and actions; and the day is coming, when these shall all be made manifest, and everyone receive according to his works. Happy they, who in that day shall be found faithful, for they shall lift up their heads with confidence and amidst applauding angels enter into the joy of their Lord: While those who have oppressed and injured the people by their power, and corrupted them by their example, shall be covered with shame and confusion, and sentenced to that place of blackness and darkness, where there is weeping, and wailing, and gnashing of teeth!

Let me now conclude, by reminding this assembly in general, that it concerns us all to fear God, and to be men of truth hating covetousness. The low and declining state of religion and virtue among us, is too obvious not to be seen, and of too threatening an aspect not to be lamented by all the lovers of God and their country. Tho’ our happiness as a community, depends much upon the conduct of our rulers; yet it is not in the power of the best government to make an impious, profligate people happy. How well soever our public affairs may be managed, we may undo ourselves by our vices. And it is from hence, I apprehend, that our greatest danger arises. That spirit of infidelity, selfishness, luxury and dissipation, which so deeply marks our present manner, is more formidable than all the arms of our enemies. Would we but reform our evil ways, humble ourselves under the corrections, and be thankful for the mercies of heaven; revive that piety and public spirit that temperance and frugality, which have entailed immoral honor on the memory of our renowned ancestors; we might then, putting our trust in God, humbly hope that our public calamities would be soon at an end, our independence established, our rights and liberties secured, and glory, peace and happiness dwell in our land. Such happy effects to the public, might we expect from a general reformation.

But let everyone remember, that whatever others may do, and however it may fare with our country, it shall surely be well with the righteous; and when all the mighty states and empires of this world shall be dissolved and pass away “like the baseless fabric of a vision”, they shall enter into the kingdom of their father which cannot be moved, and in the enjoyment and exercise of perfect peace, liberty and love, shine forth as the sun forever and ever.

Endnotes

2. There is no safety where there is no strength, no strength without union, no union without justice, no justice where faith and truth in accomplishing public and private engagements is wanting. Sidney’s discourses concerning government.