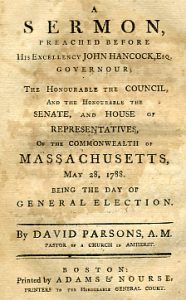

David Parsons was an influential pastor from New Hampshire. He was born in Amherst in 1749. Parsons attended Harvard and graduated in 1771; he later received a Doctorate of Divinity from Brown University in 1800. Rev. Parsons pastored the Amherst Congregational church from 1782 until 1819, and was a proficient scholar. He was offered the divinity chair at Yale in 1795 but declined the honor. He did however, become a principle backer for Amherst College, donating the land for the college and serving as board president (Noah Webster also played a significant role in the founding and establishment of Amherst College). David Parsons died in May of 1823 at the age of 74. In this election sermon, Rev. Parsons continues the century-old tradition of American ministers giving a sermon before newly-elected government leaders. Parsons’ sermon, given before John Hancock and both chambers of the Massachusetts Legislature, describes the importance of virtuous civil rulers and characterizes good government from a Biblical standpoint.

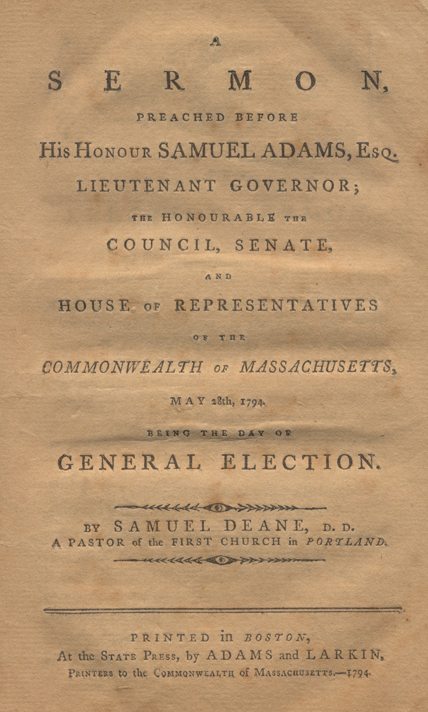

A

Sermon

Preached Before His Excellency

John Hancock, Esq.

Governor;

The Honorable the Council,

and the Honorable the Senate,

and House of Representatives, 1

of the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts,

May 28, 1788.

Being the Day of

General Election

By David Parsons, A.M. Pastor of A Church in Amherst.

Proverbs 29:2

When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice; but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn.

The preacher considers it to be the special design of our present meeting in this place (according to common usage, and the laudable example of our pious Ancestors) to seek the divine influence and direction in the important concerns of the day to express our grateful and devout praises for the inestimable blessings of government – to implore the divine blessing upon our civil magistrates in the discharge of the duties of their several departments – and to meditate on such suggestions from the oracles of truth, as may be pertinent to such an occasion.

Therefore he shall hope to have acquitted himself to the satisfaction of this numerous and respectable assembly in the part assigned him, if pursuant to the line of his own ministerial character, he shall offer such religious considerations, as may be thought proper for the business of the day; though he should avoid political disquisitions – though he should not decide in matters of controversy; or dictate in matters of state, or attempt to give instructions to politicians who are furnished with much better means or knowledge, and must be presumed to be already well informed, respecting the proper duties of their station.

Waving therefore whatever might favor of impertinency upon such subjects, I would observe, that the sentiment contained in the words under consideration, is clearly this, that the subjects or every government, however depraved, or insensible they may be to some purposes, have usually an ability to discern the virtues or defects of their rulers – that they quickly feel the advantages or embarrassments of a virtuous or vicious administration, and usually discover their internal sentiments, by exhibiting external demonstrations of sorrow or joy.

The words seem also to carry with them this further implication, that righteousness (which in the scriptures is used to signify sincere piety, or the fear of God) makes an important part of the character of a ruler. Yet there are many professors of Christianity, who, (not much to the honor of their profession) will strenuously maintain, that between religion and politics, there ought to be little or no connection – that an Infidel or an Atheist out to stand as fair a candidate for the suffrages of a people, as the pious man, or the exemplary Christian. Indeed it must not be disputed that persons of ability and accomplishments, who act from no higher motives than those of honor, popularity or ambition, are often improved by Divine Providence, to render very essential services to a community. But after all, must it not be allowed, that sincere piety, the true fear of God, refines and exalts the character of the ruler? Doth not this firm and unshaken principle which ever directs his actions, and give him a better foundation for the people’s confidence? He acts from the purest motives – he meditates the noblest actions -prompted by so divine a principle, his salutary influence, like the beams of the morning sun, disperseth the gloomy horrors of vice, tyranny and oppression; and diffuseth over the whole community, the blessings of light, joy, liberty and peace. Thus are the words of inspiration, “the spirit of the Lord spake by me, and his word was in my tongue; the God of Israel said; the rock of Israel spake to me, he that ruleth over men; must be just, ruling in the fear of God; and he shall be like the light of the morning, when the sun riseth, even a morning without clouds; as the tender grass springing out of the earth by clear shining after rain.”

Our subject naturally resolves itself into the two following propositions by way of inquiry, viz.

I. What evidence may be reasonably expected from rulers, that they possess those virtues which are the source of joy to the people?

II. When a people may reasonably express their grief on account of the corruption or ill administration of rulers?

Joy and grief are human passions, which are readily excited, and often very strongly expressed: and they are to be commended or blamed, according to the various causes whereby they are produced, and the measure to which they extend. The body of a people, may not always judge right respecting the qualifications of their rulers; yet with proper means of information, they generally form a just opinion; and the opinion which they form, is not to be holden in contempt: For no wise and good magistrate will wish to hide his character from the view of the people, or reduce to give them the best possible evidence of his integrity and virtue.

Ruler’s therefore in the legislative department, ought to enact laws which are well calculated to suppress vice; and punish the transgressor. The laws of men have often a more immediate influence upon mankind, than the laws of God; because human penalties, though not more certain, yet are expected to be more immediately inflicted. This makes it necessary that rulers should pay the utmost attention to the enacting good laws; for without these the community can never be safe; vice must reign and triumph, virtue be unprotected and depressed.

Rulers in the executive department, ought to see that good laws be well executed; for to what purpose doth it prove to enact the most excellent laws, with the proper penalties, when these penalties are never to be inflicted, nor the laws carried into execution? When the boldest transgressors may bid defiance to the laws of justice, and flatter themselves with impunity? To indulge the violators of law, with frequent instance’s of impunity – to make it easy for them to evade public justice, has always a tendency to destroy the influence of the magistrate, and bring government itself, into a state of contempt. When the guilty escape, the number of offenders is quickly found to increase: But when the laws are held sacred, and their penalties inflicted, the authority of the magistrate is established, his person respected, and the government revered.

Rulers are obliged to do justice, not only in respect to the laws, but in respect to the subjects; and they are to enforce the execution of them, (unless where some particular reasons of state may require a suspension, or omission) in order to make the best compensation that may be, for the injury of the offense. The neglect of punishment justly merited, is often the cause of God’s heavy judgments upon a people. The Benjamites refused to do justice upon the man who had occasioned the death of the Levite’s Concubine; multitudes of them were slain in battle, their cities were laid in ashes, and their whole tribe almost extinguished. To punish great and notorious acts of injustice, is called in scripture, “to put away evil from the land;” because to this purpose the sword is put into the hands of rulers; and they bear the sword in vain who refuse to protect their people. I am speaking in general of the neglect to put good and wholesome laws into execution, without having reference to particular instances; for surely not to punish an offense, is to encourage it, unless, as was said before, the indemnity is justified by particular reasons of state; by the neglect of the government to punish or suppress it. And it is certain that the impunity of the offender, is a spring of universal mischief – it is not owing to the public magistrate, if the best man in the community is not as vicious as the worst. A law had better be annihilated, than to exist with universal contempt. And no good magistrate will be an unconcerned spectator, and see the righteous laws of the State openly violated; but recollecting the duty of his office, will endeavor to bring offenders to their merited punishment.

Rulers ought to furnish the people with this further evidence of their virtue, that they are friendly to religion among their people, and use their influence and authority to uphold and promote it. Religious worship and order maintained among a people, hath a most salutary effect upon their morals; it promotes vital piety, and due obedience to the laws of God and man. Rulers therefore should, by their example and authority, encourage the worship of God, and see that it is maintained with dignity and reputation. For in this the glory of the great Supreme, and the best interest of men are jointly concerned, which are the great designs of the providential government of God in the world. It is by no means beneath the dignity of the greatest magistrate or monarch on earth, to yield the most profound subjection to God, and pay homage to the Redeemer of men; nor to consecrate themselves, to their power and authority, to his service. God requires that they cooperate with him in his designs to effect the best interest of his people – that they should be hearty friends to religion – devout worshipers of God – afford protection and encouragement to his servants – that they should be patrons, and nursing Fathers to the church of Christ; and use their utmost endeavors to advance his kingdom. All which they may do without binding the rights of conscience, or exerting their authority to impose articles of faith, or modes of worship; or enforcing these by penalties. Indeed such an exercise of power in a ruler would be to extend his commission beyond its limits and to defeat its design, which was to protect and preserve the rights of conscience. The authority of rulers may be exercised in matters of religion, so far as to tolerate, encourage and support the worship of God in some form or other. The pleas of conscience are frequently made to cover a design, and with intent only to form an excuse from contributing to the support of religion, or upholding any form of social worship. In this case the constitutional power of government ought to be employed to disappoint the dissemblers, and enforce the rights of religion.

Righteous rulers will also attend to the morals of their people. Morality is an essential part of religion, and intimately affects the very being of society: and the magistrate bears the sword in vain, who pays no attention to a matter which so much concerns the peace of society. He forgets the designs of his commission, which is “to be a terror to evil doers, a praise to such as do well.” A proper use of the authority vested in civil rulers is commonly effectual to check the rapid growth of impiety, to curb and refrain the vicious inclination of men. The profanation of God’s sacred name and worship, as well as other enormous crimes against the laws of God and the community, will be duly noticed and punished by the vigilant magistrate. The happy effects produced by the vigilant care of rulers in promoting religion and virtue – and by their attention to the morals of the people – by their exertions for the establishment of schools and seminaries of instruction, to form the morals of youth to virtue and religion, are hardly to be described. The community have had large experience of these salutary influences of the magistrate; and it is ardently to be wished that the sense of their importance, might produce a still greater degree of attention.

A people may reasonably expect to find in their rulers a love and esteem for virtuous men; and a disposition to advance those of that character to places of honor and truth. Thus the royal Psalmist, “Mine eyes shall be upon the faithful of the Land, that they may dwell with me;” “he that walketh in a perfect way, shall serve me.”

Surely a man ought not to be advanced to a station of honor merely because he has a high sense of his own merit – nor because he requires very great respect to be paid him – or because he is able to flatter, and willing to do any thing for preferment – nor perhaps because he may be used as an instrument to effect a particular purpose – nor because he is indigent, yet scorns to submit to the duties of his proper calling – or because he hath important friends to solicit for him. Therefore good rulers will regard the safety and true interest of the public, and will let those share their favors who best deserve them; having regard both to their accomplishments and virtues. They will commit no trust to a man devoid of principle, sensible that he would be likely to oppose every good purpose, as he who hates to be reformed, will hinder reformation. The unprincipled person is never to be trusted; for the most trifling consideration he will betray his trust, and make use of his power and influence to subvert the government that gave them. The frequent instances of this nature which have happened, furnish matter of caution to every government, respecting the servants they employ, and what characters they trust, with such powers as they have a constitutional right to confer. Those who are strangers to a principle of virtue and conscience, and who contemn the laws of God, will not hesitate to trample upon the laws of men, whenever it answers any sinister purpose of their own. But the man of virtue will be ready to sacrifice every private consideration, that he may promote the interest of his country, and discharge the duties of his trust with fidelity and success. He will hazard both reputation and life, as the case may be, in support of the dignity of government, and the honor of the laws. Such an one will be proof against the evil insinuations of the designing and crafty; and both in public and private will bear testimony against faction, sedition, and every evil work. Such characters therefore, will be in great estimation with righteous rulers.

It is not degrading the character of righteous rulers to pay a decent and candid attention to the complaints of their subjects, expressed in a decent manner; but it is such an evidence of their virtue as may excite a people’s joy. Rulers derive their authority from the people, and they cannot suppose themselves elevated beyond the reach of their addresses or applications. They hold their offices for a short term, after which, they must stand upon a level with their subjects. Those who are worthy of the honor, and who accept their election with proper views, will be desirous to know the particular state and circumstances of their subjects, that they may be under the greater advantage to sub-serve their interest. They will therefore pay a particular regard to their complaints, and as far as they can (consistently with the interest, reputation and safety of the Commonwealth) afford them relief; or assign a satisfactory reason why supposed grievances are not redressed; and convince the people that their want of success in their applications to government, is not owing to want of sympathy and affection; but because their petitions are incompatible with the interest of the state. Such attention paid to the supposed grievances of subjects, naturally procures affection and confidence, and seldom fails of establishing such rulers’ interest in the hearts of a grateful people. It disposeth their subjects to pay to them all due subjection and honor, according to the inspired Apostle, “not for wrath, but for conscience sake;” and to do it from interest, inclination and choice. Thus will they become the joy of their subjects, and the terror of their foes. As the wise man asserts, “when the righteous are in authority the people rejoice.” They will enjoy peculiar satisfaction to see persons of known virtue and integrity promoted in the government, and the administration put to the hands of such, as both understand in what manner to use their power; and are disposed to use it with equity and moderation. This will have a tendency to conciliate the esteem, and procure the veneration of the people; one and all will be ready to unite their influence to render their administration easy and happy.

Let us now attend to the second question, viz. When a people may reasonably express their grief on account of the corruption or ill administration of rulers?

By contrasting the former character, we have the answer. For if a people have reason to rejoice when their rulers give the most plenary evidence of a righteous and faithful administration, by suppressing and punishing vice, encouraging virtue protecting the virtuous, and religious, promoting such to office, and cherishing a fellow feeling of the distresses of the community at large, they cannot forbear to mourn and weep when they observe in their rulers, a reverse of this excellent character. For as we have before remarked, mankind have not lost all sense of the Excellency of virtue they retain such an idea of goodness, that they are willing to see it exemplified in the character of their rulers, even when they find it not in themselves. They have an exalted opinion of it in others, however averse they may be from admitting its influence in their own practice.

Nothing occasions more grief to a people than to find their rulers like Omri, the Israelitish king, making ungodly statutes – when mischief is established by laws, and the people enjoined to enforce them under sever penalties. God has often times permitted the rulers of a people to be so devoid of all sense of justice and equity, as to frame the most pernicious statutes, which in their operation, have been productive of infinite mischiefs: and which, with tolerable discernment, might have been easily foreseen. When therefore a people have the extreme misfortune to have rulers of such a description, they can expect nothing from them; but such administration as will be the occasion of sorrow and mourning as long as it shall continue.

And hence originates that dishonor and contempt in which the rulers of a people are sometimes holden by their subjects. When a people despise their magistrates, contemn their government, profane the worship of God, and insult the ministers of religion, we are ready to consider such conduct as the effect of some weakness in government, or want of virtue in the magistrate. But when a people discover a disposition in their rulers, to subvert the principles of natural justice, and injure them of their just rights under color of law; is it matter of surprise, in the present state of human nature and passions, to see them meditating to reform government, and to procure deliverance from such intolerable oppression?

Add to this, when the great political characters who ought to be the most exemplary persons, are without a sense of religion shew no proper reverence of authority, or regard for the church of Christ; do not act under the influence of conscience, or the fear of God; this is a sufficient cause for public mourning and lamentation! As such persons are greater in power influence, so much greater is the calamity of the people; for they are not only unhappy by natural and immediate consequences, but are thereby exposed to the more severe judgments of God, which will undoubtedly succeed. When iniquity or irreligion is “framed into a law,” and God must be dishonored, or the rights of his people invaded, this surely is a source of grief to every good man.

No injury so great, no iniquity so much to he abhorred as a wicked law, therefore it concerns every state to see that their laws are righteous and just. And whenever any Legislature, find on a review, that laws have been passed, though perhaps by inadvertency, which deserve that description, justice to God and man, and demands that they be instantly repealed. That rulers should frame laws notoriously unjust, deprive innocent citizens of their liberty, subject them to grievous penalties, for no cause but to gratify their own evil passions, is such a direct violation of the laws of God, and the rights of men, as must fill every sensible heart with grief and horror. Every citizen of every description, as he contributes an equal share towards the support of government, hath a right to expect equal justice and protection; unless by some crime or errors in his conduct, he hath forfeited that right; and when the right is denied, unless on account of some defect of his own, he hath certainly a good cause to complain. And when causes of complaint, by the administration of unprincipled and tyrannical magistrates, become general, and perhaps almost universal, the effects will also be as extensive as the causes; little besides expressions of lamentation and sorrow, will be seen or heard through the whole community.

The people have equal reason to mourn when wicked men are preferred by their rulers, and distinguished by their special favors. In times of confusion and degeneracy, wicked and designing men, obtain promotion; and of times such persons are entrusted with the more important concerns of the public, who were never possessed of virtue and economy, sufficient to transact their own. Hence the public are deprived of the abilities of such in the Commonwealth, who are persons of the best understanding, and the greatest wisdom. This is a sure consequence of the promotion of wicked men, that many of the most valuable characters, retire into obscurity, and decline any part in government. As Solomon observes, “when the wicked rise, men hide themselves, but when they perish the righteous increase.” Flatterers and parasites are the men who find favor with a wicked administration, but such as govern their lives by the maxims of religion, and the laws of virtue, if not wholly neglected, will commonly be disposed to excuse themselves. If they are possessed of large property, they will soon find that their exertions in favor of virtue, will render their property insecure – have they great talents and abilities, they will soon find that to use them in favor of virtue, will be to expose them to the depredations and persecutions of a wicked, lawless power – do they exert themselves in favor of the public interest, and to deliver their country from embarrassments and distresses, they find that their virtuous efforts, do but expose them to the fury of a wicked administration.

Happy is it for a land, when good men increase, and more happy when their talents are exercised for the good of the community. “But when the wicked rise, a man is hidden.” They who are void of principle, detest every thing which is sacred, as far as they have power they thrust good men into obscurity, and they are forced to abscond for their own safety. Those who are lost to all sense of virtue, duty or moral obligation, will improve their power to the worst purposes; and by this means they debase their character in the elimination of the people, who feel themselves truly miserable under their oppressive administration. They cannot but mourn to see their rulers so devoid of the principles of virtue, while they behold the melancholy effects of their wickedness, wherever they turn their eyes – they cannot but mourn when they anticipate the event of such unrighteous measures of government, and the miserable consequences which must necessarily be produced. Sad indeed is the condition of that people, who have just occasion for such complaints! They cannot but give their attestation to the truth of the observation, in the text, “when the wicked beareth rule the people mourn.”

IMPROVEMENT.

A very natural reflection, which may be made upon the subject is this, viz. That virtue is honorable, and adds an eminent luster to the reputation of a ruler. And in this view particularly that it is praised and admired by those that love it not, that it is honored by the followers and family of vice – that it forces glory out of shame, honor from contempt – that it reconciles men to the fountain of honor, the Almighty God, “who will ever honor those that honor him.” Certain it is, that religion sub serves even our temporal purposes; no great end of state, can be well attained without it; even ambition itself often seeks to derive its support from a pretense of religion. “If a new opinion be commenced, and the author would make a party, and draw disciples after him, at least he must be thought to be religious.” This is a demonstration how great an instrument or means of reputation, piety and religion are. Now if only the pretense will do us such good offices amongst men, the reality will do us much more, besides the advantages we may hope to receive from the divine benediction. The power of godliness, will certainly do more than the form alone.

No one it is presumed, can infer from any thing which hath been suggested, that obedience is not due to rulers from their subjects, although they might have reason to be suspicious of their moral character, and although there be many things in their administration, which might be a just cause of grief and mourning. The obedience we owe to magistrates, differs essentially from that which we owe to God. We ought to obey God with our understanding, and will, that is, we ought to obey him intelligently and freely; our obedience resulting from a sense of the rectitude of his precepts. But such obedience to human laws is not always required; for we may sometimes doubt of the fitness or equity of them. For so long as magistrates are liable to error, though it be highly necessary, considering ourselves as members of society, that we conform our own actions to their laws; yet it is not always our duty to believe that their laws are most salutary or convenient, because human laws may be sometimes otherwise. But our social obligations require us to be subject to laws which we may think very inconvenient, provided they be not sinful in themselves. It would be happy if inferiors would not employ themselves too much in disputing the policy and prudence of their rulers, and the propriety of their laws. We are not to obey laws, which cannot be obeyed without conscience; but an action may be wrong in respect of the person commanding it, and yet innocent in respect of the person who executes the command.

In the case of wars between nations or States, the subjects cannot be a competent judge of the equity of the dispute, yet perhaps he must bear arms, i. e. he must pay due obedience to the powers of the State. And in the case of executing an unjust sentence on a supposed criminal; not the executioner, but the judge is commonly considered as the author of the injury. He who serves his Prince in an unjust war, is but the executioner of an unjust sentence. It is generally true, that subjects are obliged to yield obedience to the laws of the State, without questioning the policy of them, if they are not apparently repugnant to the laws of God: Whereas to oppose the ruler, on any other principle than this, tends to introduce confusion into society; weakens the bands of government; destroys the authority and influence of rulers, and is in danger to issue in the subversion of the State.

Human government is of divine ordination, and our understandings are impressed, at first view, with the necessity of it. Every one must feel and acknowledge the propriety and utility of that subordination in society, which is required by the divine constitution. And he who is ever ready to impeach the conduct of rulers, reproach their administration, and dispute the wisdom, propriety or policy of their laws, obstructs their usefulness, weakens their influence, and exposeth himself to the displeasure of him, whose servants or vicegerents they are: He doth all in his power to bring the wisdom and power of the magistrate into contempt, and plunge the State into confusion and disorder. Suffer me to add, that he who is confident of his own understanding (and who is more so than he who thinks himself wiser than the laws?) needs no other tempter, than himself, to pride and vanity, which are the natural parents of disobedience. The laws ready to impeach the conduct of rulers, reproach their administration, and dispute the wisdom, propriety or policy of their laws, obstructs their usefulness, weakens their influence, and exposeth himself to the displeasure of him, whose servants or vicegerents they are: He doth all in his power to bring the wisdom and power of the magistrate into contempt, and plunge the State into confusion and disorder. Suffer me to add, that he who is confident of his own understanding (and who is more so than he who thinks himself wiser than the laws?) needs no other tempter, than himself, to pride and vanity, which are the natural parents of disobedience. The laws which are enacted by wise and just legislators, are not dictated by an arbitrary will, but result from the principles of reason and justice. They are reasonable and good in themselves; they are calculated not to sub-serve any sinister purposes, or private views, but to advance and secure the happiness of men. Whenever it happens otherwise, the legislators are tyrannical, and the government oppressive: Statutes contradictory and inconsistent are to be expected, and even such as might invert the order of things, and substitute vice, in the room of virtue. From the rotations of subjects to rulers, obligation to rulers, and duties upon those obligations, do necessarily result. Subjection to laws being considered the first and most essential of those duties, ought to be cheerfully yielded by the good subject, though in some cases it may be apprehended that the laws are not the most salutary to the interest of the people. Every citizen cannot be supposed to be able to determine absolutely on a subject of so great importance. But it must be his duty to persevere in his subjection and allegiance, till his rulers may perhaps be convinced that their measures ought to be changed; which conviction, if there be real foundation, they may quickly receive from the complaints of the people, and from such regular remonstrances, as will proceed from the most loyal and virtuous citizens.

Let us all endeavor to cultivate within our sphere, a reverence for authority, and a due submission to laws and government. Lifting up our desires to God that he would ever favor this Commonwealth with righteous rulers, who shall not feel indifferent to the rejoicings, or complaints of their subjects. And that under their wise and prudent administration, “the people may lead quiet and peaceable lives in all godliness and honesty.”

The usual addresses on such occasions as the present, will close the subject.

And as decency and propriety dictate, I would address my subject to his Excellency the Governor and Commander in Chief of this Commonwealth.

May it please your Excellency, God in his good providence hath conferred a signal honor upon you in repeatedly placing you in the highest seat in government, and entrusting you with the principal management of the most important concerns of this Commonwealth. It cannot, Honored Sir, but excite in your breast the most pleasing sensation, to find your character thus revered, and your person holden in such high estimation by so numerous and respectable a people as compose this State; and to see the evidence which it gives that your administration is of a similar complexion with that mentioned in our text, which is ever a source of general joy.

And however gloomy and difficult the day is in which you preside, your administration being of the description above, you may look for and expect all needed aid from him “who giveth wisdom to the wise, and knowledge to them that know understanding.”

Your Excellency’s early and intimate acquaintance with the situation of the Commonwealth, and a thorough knowledge of the constitution particularly, render you a more able instrument in the hands of Providence, and give you peculiar advantages for guiding our public affairs with a skillful hand. An uncommon share of knowledge, prudence and wisdom in a Governor is specially necessary in such an important and critical day as the present; to steer the helm of government with discretion – to afford light to a people enveloped in darkness and doubtful expectation – to relieve them of unnecessary burdens – and to protect their liberties from any encroachments. Your Excellency will find occasion for the improvement and exercise of all your peculiar talents in directing and regulating the public affairs of government, so as to preserve the rights of conscience, and give satisfaction to all your citizens. The popular account is very uncertain; and though the important services rendered to your country in the most hazardous transactions, have raised your Excellency’s reputation, and enrolled your name among the patriotic heroes of the age, yet such is the uncertainty of human things, that is possible that some inconsiderable circumstance, which might counteract the wishes of a misguided people, might sully the luster of all your former glories.

If your Excellency had no higher spring of action, and were not actuated by the noblest, and most disinterested motives, in your arduous and unwearied endeavors to promote to promote the lasting reputation, interest and peace of your citizens, your situation might expose you to the severest mortification. But we flatter ourselves that you have a more stable foundation of security and honor from a conscience witnessing your integrity; and your sincere endeavors that righteousness shall mark all the steps of your administration; that the present and future joy of your citizens may not be interrupted or diminished.

As your Excellency’s character stands high in the estimation of this people, it gives you a greater advantage, and should be no less a motive with you to study, and invariably to pursue their best interest and happiness. In seeking the common good and welfare of your people, you will secure your interest in their affections, and live in their hearts; which must afford the greatest satisfaction to a good magistrate. You will doubtless think it your duty to discover a becoming zeal in promoting and maintaining that righteousness among the people “which exalteth a nation;” and for the want of which, the basis of the happiest governments, in other respects, have been wholly subverted.

Your example and influence will not be wanting to the support of religion and religious order that the worship of God be upheld – the Sabbath duly sanctified-the ministers of Christ encouraged and supported – that schools of learning be duly maintained, according to the true spirit and intent of the good laws of our Land, and the pious examples of our ancestors.

But especially will your Excellency be disposed to use the influence of your dignified and exalted station, to bring vice and irreligion into disrepute, the rapid growth of which, is truly alarming! As the minister of God you cannot be an unconcerned spectator, while his enemies are profaning his sacred name, degrading his worship, contemning his Sabbaths, and treating his faithful servants with scorn. Your pious indignation in this case, will be roused, and with zeal will you countenance and support the arm of the proper magistrate, in executing the laws of the land, against bold transgressors, that they may flee or fall before them. In this way, Honored Sir, you will mightily sub serve the cause of reformation, and lay a restraint upon vice, which will in the final issue of things, be branded with eternal infamy.

In every part of your Excellency’s administration, your reverence for God and zeal for his cause, will induce you to make his revealed will, that unerring standard of truth and righteousness, the basis of your conduct: Not unmindful that this is not only the rule by which your administration is to be regulated; but whereby Deity itself will be guided in the final decisions of the last day; in which the greatest Potentate will be equally interested with the meanest peasant. A suggestion which your Excellency will not judge unreasonable, from the recent instance of the death of your worthy, pious and truly excellent contemporary in office, 2 since the last anniversary Election: Whose virtuous character, and unwearied endeavors to promote the true interest and reputation of his country, will render his memory dear, and lasting, with all the sons of freedom.

That you Excellency may long live the joy and ornament of this great people; that your health may be confirmed, and your usefulness protracted – that your administration may be productive of still greater rejoicing with the people of this Commonwealth; and when filled with days and replete with grace, you shall be discharged from further services here, that you may share the honors of the heavenly world, will be the unceasing prayers of the virtuous and good.

Our subject is next addressed with due humility to the Honorable the Senate, and House of Representatives.

Honored and respectable Gentleman, The sovereign powers of this Commonwealth vested in you, by the united voice of this large people, give high importance to your character, and entitle you to their respect and confidence. And that you may not disappoint their most sanguine expectations, you will make religion and righteousness the basis of your administration and rule of your proceedings. That all your laws shall favor of piety and a sacred regard for the honor of God, and the best good of your constituents.

This was the original design of the institution of civil government, and so far as you should deviate there from, you would defeat the end of your promotion.

There is no positive certainty, indeed, that the best rulers will wholly escape the invectives of disappointed individuals, but integrity and uprightness will be sure to establish the approbation and esteem of all that are truly virtuous. Such persons are not unapprised of the difficulties and embarrassments with which all public business is attended – and they very well know that great allowances are to be made for the seeming inconsistencies that are many times discoverable in governmental matters; and are more likely to be found in republican governments, where it is so peculiarly necessary to comply with the humors and conform to the wishes of the people. When rulers make it evident that they are governed by principles of integrity; and there is no appearance of injustice in any of their acts, the judicious part of the community will revere their authority and obey the laws, even when they may not be exactly conformed to their own political sentiments. The public are in no danger from its virtuous citizens; for they never will be found to lessen the influence of authority, or unhinge the bands of government, even though they should consider the operation of some particular laws as being unjust, oppressive, and severe, if at the same time, they considered their legislators as honest men, who had no intention to oppress.

Rulers therefore should study to approve themselves to God, to their own consciences, and to the virtuous among their people, if they would be desirous to be useful, and increase the joy of their citizens. Envious and disappointed individuals will be able to make but a feeble opposition to the measures of government, if the character and conduct of rulers justly command a general reverence with the virtuous and good in the Commonwealth. These will feel themselves constrained from a love of order, from a respect to real merit, from a sense of interest, from a regard to the morals of the people, and from the more important conviction of duty to God’s institution, to exert their influence in favor of established government.

If then, Gentlemen, you would answer the end of your delegation, and would “be a terror to evil doers, and a praise and encouragement to them who do well,” it will be a principal object of your attention to rule in righteousness. And in order to rule well, it will be equally necessary that you should exhibit an example of virtue, that religion and piety may not only be discovered in your laws, but in your conversation, “rendering you conspicuous for piety and mercy, justice and sobriety;” in this way will your authority be strengthened, and your administration supported. Your constituents will be induced to take their measures and example from you. And they will be encouragers of peace or licentiousness, in some measure, as they shall find countenance or encouragement from your conversation and example.

The eyes of the people are upon their rulers, and upon you, Gentlemen, in particular, to hear your sentiments in the most critical cases, and disputable subjects; and may expect from you such things as do not fall within your department. In such a case, Gentlemen, you will doubtless recollect the powers vested in you by your commission, and keep within its limits.

However, Gentlemen, I would not presume to go out of my line, to dictate to you any measures of a civil or political nature; your wisdom and good sense do not require this from me.

Permit me to say, that as magistracy is of God’s ordination, you have a right to expect and demand due respect and obedience from your subjects. And we “ought for ever to consider it as a peculiar favor of Heaven, that Christians are promoted to be rulers and judges among Christians.”

It belongs to your department, Gentlemen, not only to enact righteous laws, but according to your constitutional department, to judge righteous judgment – to plead the cause of the oppressed; to relieve the fatherless and widow, and him that hath no helper; to render to every one according to the justice of his cause which shall be brought before you. You will remember, gentlemen, that you commission is limited by God. He who has dignified you above your brethren, hath limited your powers by his holy word. You are not authorized to obey the dictates of passion or arbitrary will, but to act agreeably to the revealed will of God. When Joshua was appointed chief magistrate, God installed him in his powers, and put the law into his hand saying, “this book of the law shall not depart our of thy mouth.” Look then gentlemen upon the copy that is before you, then upon the commission which is given you. And as you are God’s vicegerents to carry on the affairs of his kingdom on earth, you will take your directions from his word, and imbibe his spirit.

We being sensible, gentlemen, that your wok is difficult, and that you have an arduous task to cure all the disorders of the political body, restore harmony and peace, and to unite the jarring interests of parties, and fix them to one common center, do most sincerely commend you to that God, “who giveth wisdom to the wise, and understanding to the prudent”. Ye yourselves cannot but be sensible of your need of divine aid and direction: “In all your ways then acknowledge God, and he shall direct you paths.” Let a consciousness of human weakness prompt you, to repair to the fountain of light and knowledge, and may you improve them, when obtained, to the honor of God and the good of your constituents. And may you obtain the divine presence and blessing in the faithful discharge of the duties of your department during your whole administration. And as a reward for your services, may you be honored as the political saviors of this people, and meet their most cordial approbation with great rejoicing. And more especially may you reap the effects of a serene and acquitting conscience. And having served your generation according to the will of God, may you participate the joys of the blessed forever.

This whole assembly of God’s people will permit me to make the suggestion, that virtue in rulers is not more necessary than in the body of the citizen’s collectively. The more virtuous the community, the less is the occasion for the exercise of the gifts and graces of those in authority, and the less is the danger of injury from rulers if they were ill disposed. When we are tempted to complain of our rulers and feel anxious least they should betray their trust, and expose the people to the loss of their liberties, we may recollect that a virtuous people cannot be enslaved, and that it would be impracticable for rulers to involve their citizens in calamities that are grievous and mournful, if there were not a large proportion of abandoned and unprincipled men to give countenance to, and aid them in their evil designs. And if a community are so lost to a sense of their own interest, and so regardless of their obligations to God and each other, as justly to expose themselves to the most fatal injuries, who can declare that their calamity is unmerited?

That the administration of civil rulers may be such as may occasion rejoicing, it becomes us not only to solicit God’s presence with them and his blessing upon them; but to demean ourselves as good citizens, and remove all the embarrassments which may render it excessively difficult, if not wholly impracticable, to do equal justice in all cases.

It cannot be denied but that a people may have sometimes a mighty influence upon a righteous administration, and procure such measures to be adopted as are fraught with matter for grief and mourning. But this evil ought not to be palmed upon our rulers. We ought, in such cases, as honest men, to reprobate our own conduct, and keep within our own province. There is not a greater mischief which can befall a people, than to be divided into sects and parties, either in respect to religion or civil policy. The consequences are fatal to peace, harmony and order; and it is this, my friends, which renders our present situation very threatening.

On all accounts it is our interest, and we are bound in honor and conscience faithfully to adhere to, and vigorously to pursue the same glorious cause. We are bound to unite our influence that religion and righteousness may spread and prevail – that practical piety and holiness may be more visible in our lives, and that the worship of God in private and public, may ornament our society, and that our own hearts especially, may become a fit habitation for the Holy Spirit.

True Piety in the hearts of men, will render them the best citizens. And both rulers and people are under the same divine laws, are subject to the same authority, encouraged and animated by the same motives, and favored with the same example. It would be happy if their object might be the same; and they were equally studious to promote the honor and glory of their common Lord.

Let us not forget that the same rules that will teach, and the same grace and integrity, that will dispose rulers to discharge the duties of their office faithfully, are equally necessary and ought to be equally regarded by those whom God hath made subject to them:

And that all opposition to lawful authority, “is resisting the ordinance of God,” who hath made it our duty to be “subject not only for wrath, but for conscience sake.”

And let me suggest, that as we make our religious character our boast, and have so oft made our appeal to Heaven, that we are God’s people, and our cause the cause of God, we ought strenuously to endeavor to make the sincerity of this profession, more evident to the world; otherwise we shall justly deserve the imputation of having our hearts and tongues at the greatest remove from each other.

If declarations entitled us to credit abroad, and even with Deity itself, our deserts could hardly be compensated. But let us deal faithfully with ourselves, and confess our personal and national unworthiness, if we expect God’s forgiveness and blessing. And let us cultivate a principle of justice, of public spirit, and benevolence in the community; and live as the grace of God teacheth. Let us be sensible of the invaluable blessings, which indulgent Heaven bestows – and particularly, that we enjoy the great advantage of civil government, by the continuance and support of which, we are, for the present, secure in our persons and properties. And while we all affect to seek a mild and equal government, may we unite our influence to support the same, that “in the peace thereof, we may have peace.”

And though we might be apprehensive that there were grievances which ought to be redressed, yet ought we to let a manly firmness and resolution be discovered in pursuing the paths of virtue till the object be obtained.

A people may be as criminal in adopting means of relief, as they can suppose those to be, who originated the cause of complaint. And while our conduct is such as it ought to be towards our rulers, and we suitably address them upon the subject of public burdens, let us encourage ourselves that they will feel our distresses, and ease our complaints.

Let us resume courage and hope for better times – when peace and good order shall be established upon a proper basis – when justice shall be impartially administered – when friendship, brotherly love, and Christian fellowship, shall be universal. When it shall be reckoned an honor to be sincerely religious, and to be subjected to the rules of righteousness in all our transactions with men. When none but the virtuous shall rule and judge the people of God, the administration of whom shall greatly increase their joy and gladness.

Then truly “blessed is the people that know the joyful sound; they shall walk, 0 Lord, in light of thy countenance. In thy name shall they rejoice all the day, and in thy righteousness shall they be exalted. For thou art the glory of their strength; and in thy favor our horn shall be exalted. For the Lord is our defense, and the holy one of Israel is our King.”

AMEN

NOTES

[1] Ordered, that Mr. Cooley, Mr. Carnes, and Mr. Parsons, be a Committee to wait on the Reverend David Parsons, and thank him, in the name of the House, for the Sermon delivered by him, this day, before His Excellency the Governor, the Council, and the two Branches of the General Court; and also to request of him a copy thereof for the press.

[2] His Honor Thomas Cushing, the first Lieutenant-Governor of the Commonwealth, who died February 28, 1788.

(1731-1820) Biography:

(1731-1820) Biography: