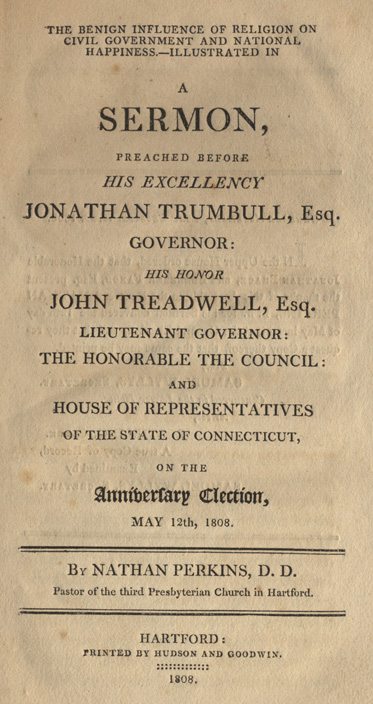

Nathan Perkins (1749-1838) graduated from Princeton in 1770. He preached in Wrentham, MA shortly after graduation, and at West Hartford Congregational Church (1772-1838). The following election sermon was preached in Hartford on May 12, 1808.

THE BENIGN INFLUENCE OF RELIGION ON CIVIL GOVERNMENT AND NATIONAL HAPPINESS.—ILLUSTRATED INA

SERMON,

PREACHED BEFORE

HIS EXCELLENCY

JONATHAN TRUMBULL, Esq.

GOVERNOR:

HIS HONOR

JOHN TREADWELL, Esq.

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR:

THE HONORABLE THE COUNCIL:

AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT,

ON THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

MAY 12TH, 1808.

BY NATHAN PERKINS, D. D.

PASTOR OF THE THIRD PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN HARTFORD.

GENERAL ASSEMBLY, MAY SESSION. A. D. 1808.

In the Upper House ordered, that the Honorable Jonathan Brace, and Ebenezer Faxon, Esq. present the thanks of this Assembly to the Reverend NATHAN PERKINS, D. D. for his Sermon delivered the 12th day of May instant, at the General Election, and that they request a Copy thereof, that the same may be printed.

Test,

SAMUEL WYLLYS, Secretary.

Concurred in the Lower House.

Attest,

E. STIRLING, Clerk.

A true Copy of Record,

Examined by

SAMUEL WYLLYS, Secretary.

ELECTION SERMON. NATIONAL VIRTUE, AND NATIONAL HAPPINESS

DEUT. XXVIII. 1, 2.

And it shall come to pas, if thou shalt hearken diligently unto the voice of the Lord thy God, to observe and do all his commandments which I command thee this day, that the Lord thy God will set thee on high, above all nations of the earth. And all these blessings shall come on thee, and overtake thee, if thou shalt hearken unto the voice of the Lord thy God.

TO render a nation happy and prosperous, the wise and reflecting will readily admit, is of the highest consequence. The first concern of civil rulers, of those who have the management of the public interests lodged in their hands, should, therefore, be to obtain and secure such a state. And if united in their exertions to accomplish it, as their main object, unquestionably, success would generally crown their labors. There is a way, without doubt, for a nation to be permanently prosperous and happy. A moderate share of true patriotism will lead us to wish that our nation, now in its infancy, and but lately risen to be one among the empires and kingdoms of the world, may be distinguished in the annals of history, for its virtue and prosperity.

Looking over the history of former ages and nations, we have to lament that the way to gain and establish public happiness has been seldom pursued. Concerning this way, a great diversity, likewise, of opinions, has prevailed in the history of the world. Of this diversity of opinions, all history is a proof. We know that wrong measures have been taken. And alas! we also know that most nations, in the past ages of the world, have never been long happy. They have either groaned under tyranny and oppression, been afflicted with famine, or plunged in bloody and expensive wars. The right measures to render a nation happy, have either not been discovered, or if discovered, have not been adopted. It may with high propriety be observed that a people must be free, in order to enjoy the greatest quantity of public happiness. An enslaved and oppressed people, cannot possess the necessary ingredient of national glory. Such a people, as live, or rather drag out their existence, under absolute despotism, where oppressive and unrighteous laws are enacted, and are oppressively and cruelly executed, may be calm, and tranquil; but their calmness or tranquility, is the calmness of the dead sea. The chief excellence of civil liberty, that pleasing and delightful sound, so dear to our citizens, is its tendency to put in motion all the human powers;–it promotes industry, and in this respect, happiness:–produces every latent quality, and improves the human mind; and is the source of riches, literature and heroism. People who live under arbitrary governments, are found to love their forms of government as ardently as those who live in a free state, love theirs; and often more ardently. They are as contented. Perhaps, impatience and discontent are more observable in free than in arbitrary governments. Immense advantages however, result from the enjoyment of a free government. And, in this land, we have a free government. The human race are all born EQUAL and FREE. The true notion of liberty and equality is the prevalence of law and order, and the security of individuals. This is supposed to be a primary source of national happiness. The grand enquiry is, how may a people under a free government, be most prosperous and happy. Virtue is essential to the well being of such a government. The truth contained in the words now read, is, that the GREAT MEANS of obtaining and securing national prosperity and honor, are piety and morality.—By harkening diligently to the voice of the Lord our God, and by observing and doing all his commandments, we are, past all doubt, to understand the whole of revealed religion, the duties of the first and second table of the law, piety and morality.—By God’s promising to set a people on high, above all nations of the earth, and blessing them, we are to understand, public happiness, and national glory and prosperity.

The doctrine of the text is, then, most obviously, this, that piety and morality are the only CERTAIN MEANS of national happiness and prosperity. This is a truth of the greatest possible consequence to mankind; is the uniform doctrine of the holy scriptures; and is clearly proved from the reason and nature of the thing, and yet after all has been overlooked by most philosophers and statesmen.

To this important and interesting truth, your attention is now to be directed. And no subject can be more worthy of the attention of civil rulers, and those who have the management of the national counsels and interest, or be better adapted to this great anniversary occasion, when our rulers, and the tribes of the people are assembled before God, to render their homage to him, and devoutly to implore his blessing on the commonwealth. If everyone, whether in public or private life, had a deep impression of this truth, the effect would be most salutary.

What is accordingly proposed, in the subsequent discourse, is,

I. Concisely to explain the nature of that piety and morality, which are said to be the CERTAIN MEANS of public happiness.

II. And chiefly, to enquire how it appears that they are the certain means of national glory and prosperity.—And we are to consider,

1. The nature of that piety and morality, which are said to be the certain means of public happiness. Little need be offered here. No more indeed will be offered, than may be necessary to present the subject, in a fair light, and to prevent mistakes and misapprehension. The nature of revealed religion is often delineated. It comprehends these two things, piety and morality; and they are put together, in this discourse; because, essentially connected. Morality is not only an important, but necessary part of true religion. No man can be really pious, who is not a moral man; neither can he be a moral man, in the largest and best sense of that word, who is not a pious man. In the words now under consideration, piety and morality are set forth, under the idea of hearkening diligently to the voice of God—and observing and doing all his commandments. To hear his voice, is to believe all the doctrines which he has revealed, and exercise all the affections of the heart towards him, which constitute vital piety. We cannot, with any propriety, be said to hear diligently his voice, if we disbelieve his truths, or omit devotional exercises and offices. To observe and do all his commandments is habitually to perform all moral, as well as religious duties. All revealed religion, consequently, may be considered as divided into these two great branches; piety and morality, or the love of God, and the love of our neighbor.

Piety comprises all the affections and duties, which we owe to God and the Saviour. We are required to love our Maker, with supreme affection. And this supreme love to him is the grand principle of religion, and foundation of all right exercises of heart or duty to him. Here all religion begins; and divine worship, steadily maintained in its several forms, is the chief part of piety. He, indeed, is a neglecter of piety, who does not devoutly engage in the exercises of divine worship, public, social, and private. The fear of God is essential to a pious temper. We are not pious, unless we have a reverential awe of his sacred Majesty. We are to serve, to fear, to adore, and to praise him, as our Creator, Preserver and Benefactor. In every step of our conduct, we are to look up to him as the supreme disposer of events, to feel our obligations of reverence for his names, titles, ordinances and word. The first concern should be to give all glory to him, and render him, as honest minds, all the duties which he requires. No man can be really pious, who habitually and statedly omits the offices of devotion, and holy exercises of heart towards him. A principle of piety will necessarily lead to a trust in his mercy and wisdom—a becoming sense of all his infinite glories—a choice of him as our God—a cordial reception of the Redeemer of a ruined world, in all his saving work and offices, a reliance upon the revealed way of life and forgiveness—the high and mysterious dispensation of grace. It will create in the soul, a holy mourning for all our departures from God and duty, and violations of the divine law. It will dispose us to place him on the throne, as exercising a wise and beneficent government; and as ordering, directing, controlling, and conducting a dependent universe, at his sovereign pleasure, and in the best possible manner, so as eventually to cause the greatest sum of blessedness. In the exercise of pious affections to God, and stated and habitual practice of the duties which we owe him, we choose him for our portion; and say, for this God is our God forever and ever: he will be our guide even unto death.

Morality is the other constituent part of revealed religion. We are to observe and do all God’s commandments, as well as diligently to hear his voice. Our duty to our neighbor, and ourselves is to be uniformly practiced, as well as our duty to God, and a divine Mediator.—Scriptural morality comprehends the constant practice of every civil, social and relative duty. The moral man, according to the inspired volume, is honest and righteous, kind and charitable, compassionate and pure, in his intercourse with his fellow-creatures. He never allowedly oppresses by extortion—acquires property by injustice and fraud, falsehood and hypocrisy. He never habitually takes away the reputation of others by slander and lies; or wishes to destroy their peace by violence and deceit—and is careful to avoid all crimes against society—or sins against others, as malice, hatred, revenge, dissimulation and evil speaking.—His rule of duty is to do unto others as he would be done by, from a principle of benevolence. All things whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye the same unto them. Scriptural morality is summed up, in the following manner by the apostle Paul.—Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report, if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.

The moral man, according to scripture, is attentive likewise to all that class of duties, which relates to himself, as well as his neighbor. He uniformly endeavors to exhibit to all observers, strict temperance, continence, sobriety, self-government, and purity in heart, speech and behavior. If at any season of temptation, he wrong his fellow-men in their property, he hastens to make restitution. If in their good name, he honorably makes reparation, if he fall into sins, by the indulgence of passion and prejudice, pride and avarice, ambition and envy, against himself or neighbor, he penitently regrets his folly, and resolves, in future, on amendment. He makes conscience of living in all the ways of holy obedience—of assisting and helping all in his power—of molesting and injuring none.—Such is the nature of scriptural morality: of that morality required and recommended, in holy writ—and which must flow from a right principle, the love of God and our neighbor.—And we ought to remark here, to prevent all misapprehension and prejudice, that this morality cannot exist without piety—but is essentially connected with it.—There may be, we know, and very often is, an outward decorum of manners and conduct, or outward regularity of life, where there is no piety. Nay, where there is a total disbelief of all religion—of the being of God—the immortality of the soul—a state of future retributions, and of conscience. This is, many times, through ignorance, relied on as all the religion necessary to man, and is frequently called moral honesty. But it is totally different from scriptural morality, and is only built upon maxims of worldly convenience—customs of the country—a pretended sense of honor, or some selfish views; it is, however, beneficial to society.

Upon the whole, no man can be a moral man in the scripture sense, who is unjust to God, to himself, or his fellow-men. He, who feels his obligations to God, will feel his obligations to man. He, who loves his Maker, will love his neighbor. He, who reveres the divine Majesty and attributes, will regard the rights of man. We are as inexcuseable, in allowedly omitting the duties of piety, as of morality. The sum of the moral law is to love God with all our heart, and our neighbor as ourselves—on these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

2. We proceed to the next thing proposed, which is the principal design of the discourse, to enquire how it appears that piety and morality are the CERTAIN MEANS of national happiness and prosperity. This most important and interesting truth is strongly expressed, in the words now under consideration. And it shall come to pass that the Lord thy God will set thee on high, above all nations of the earth. And all these blessings shall come on thee, and overtake thee, if thou shalt hearken unto the voice of the Lord thy God. The whole nation was to be thus blessed and protected, defended and prospered, if virtuous. As long as they would be faithful and diligent in serving God, adhering to, professing, and practicing the true Religion, he would bestow temporal advantages—withhold national judgments—raise them, in character, and importance, above other nations, give them a name, and make them a praise in the earth. The religion, which God has revealed unto the children of men, is calculated, to make both individuals and nations happy. This is a point of supreme importance, and as the sons of philosophy, and rulers of the world, have both thought and acted very differently from it, it is eminently worthy to be accurately considered, and firmly established by argument. Had the Empires of the world, and politicians believed and acted upon this single principle, man would, long ago, have reached the highest point of perfection and happiness in society, attainable on earth. But now alas! he is as far from this desired point as ever. After so many nations have perished—so many kingdoms have risen and fallen—so many wars and revolutions, mankind have still to learn that free governments only can secure happiness to the ruled, and that free governments can only be supported by virtue. As long as the body of the people continue well informed and virtuous, freedom may be enjoyed.—The truth now to be established, is that piety and morality are the certain means of national glory and prosperity. And that they are so, will appear first, from a consideration of the origin of civil government, and what is, or ought to be its end or design. The wants of man are unquestionably the first cause or origin of the social compact. In a solitary state, he would find himself totally inadequate to procure what might be essential to his well-being. Every individual has many wants, which he cannot satisfy, is surrounded with evils, which he cannot remedy, exposed to fears, which he cannot remove, and open to dangers, against which he cannot provide. Unable is he of himself to supply his necessities. He wants knowledge to guide and direct him; laws to restrain and rule him; property to support him; food to nourish him; and clothing to cover him. All find themselves encompassed with these wants. Feeling the same wants, men unite, to provide for their own convenience; and by common industry to guard against famine, and to procure, in sufficient plenty, the means of subsistence. They, therefore, form society and government. Man, in his very nature, is social; was made by his adorable Creator, to derive his sweetest happiness from union in society. Man is naturally inclined to unite with man for protection, defense, and the common good. The end of all government, consequently, must be to secure the rights and property of all its subjects. Why should they form society and government, but to promote their own welfare and happiness! As a rational creature certainly this would be man’s object in forming government. Endowed with reason, and capable of reflection, his desire would be to possess the means of being happy. The design of forming government then must be the COMMON GOOD of the whole, and to obtain blessings for all the governed. The original purpose of the institution of government must of course be the best good of the people, at large; not to provide for the ease, and honor of such as might be entrusted from time to time with its management. The people are the source of power.—The design, then, of all government, must be the good of the governed, not the aggrandizement of the individuals, who hole its reins.

If the origin, and end of government, have been justly stated, it is apparent that the blessings sought by the social compact, cannot be attained, without piety and morality—a sense of moral obligation—a belief of a divine existence—of man’s accountability—and the ties of justice and humanity. Each individual should feel responsible to each individual, and to the whole. He must be industrious, that he may not be burdensome to the rest of the community. He is bound to avoid also all those practices, which will injure others, or trespass upon their rights. He must love mercy, as well as do justly, that he may be the most useful to others. All the branches of morality must be observed, that the community may be generally benefitted. No man may live for himself alone, but must look at the things of others, and that the public good may be advanced. But the various duties, which man owes to himself, and his fellow-men, as a part of the public, will not be habitually performed, and with a good conscience, if he feel not his accountableness to a superior tribunal, to an omniscient and omnipresent Judge,–If he have no fear of God—no regard to a future world—and if he, customarily and openly, CONTEMN the duties of piety. The moral duties are essential to the well-being of the community. But they are built on the fear of God, or piety, as their only solid foundation.

In order to cut off all objections and cavils, which those may raise, who disbelieve or deny the necessity OF ANY RELIGION, in order to the greatest national honor and glory, we ought to remark, that when it is affirmed, that piety and morality, are the best means of national prosperity and glory, it is not to be understood that no nations have flourished, except such as were governed by the precepts and doctrines of religion. Some states, which have only partially conformed to its laws, have long flourished, and enjoyed glorious advantages on the theatre of the world; either because their false religion, contained some principles in common with the true; or because in order to induce such people to practice such virtues as are essential to the being of society, success has attended such practices; or because virtue has never yet been fully rewarded, or vice punished in this world. But it will be found, that public happiness is best promoted by an adherence to religious and moral institutions. It is not pretended that this will, in every particular case, ensure the greatest temporal advantages. If an individual will love life and see good days, let him refrain from evil and do good, so if a nation would prosper and be exalted, they must adopt the same wise course. STATE-CRIMES, however, may be sometimes, for a season, successful; and may have been the steps, by which nations may have acquired worldly glory. National justice, moderation, and regard to the rights of other nations, may be sometimes an obstacle to grandeur. But if we consider a nation, in every point of light, and in all its circumstances, we contend, that the more piety and morality are practiced, the more prosperity it will enjoy; and that the more it abandons itself to vice, the more misery, sooner or later, it will suffer, according to the very nature of things, and a wise and governing Providence. If vice for a while seem to exalt, and virtue to abase it, still in the end, vice will be its overthrow, and virtue its exaltation. It is, also, worthy to be observed that by the prosperity or glory of a nation, is not intended what worldly heroes and tyrants consider as such, enlarging its territories by wars and conquests; acquiring power and influence over other nations by fraud and injustice; and becoming a terror and scourge, as executioners of divine vengeance. By national prosperity, I mean the happiness of the citizens at large, in their various orders and classes—attacking an enemy when invaded with courage—defending itself with resolution—negotiating successful treaties—possessing every blessing conducive to public tranquility—and favored with the protection and smiles of the divine Being. We do not suppose that piety and morality will free a nation from calamities. This is an imperfect world. Adversity will be mingled with prosperity. Untoward events are to be expected. There may be unhappy disputes with other nations on account of interfering interest—or a supposed interference. There may be wars—famine—pestilence—and other great and terrible evils. The most virtuous societies, like individuals, may labor under trials and difficulties, and must expect many misfortunes.

A further consideration to evince, secondly, the benign influence of religion on civil government and national happiness, is, that public bodies and communities only exist in this world; and of course, can only be rewarded and punished in this world by Divine Providence. Individuals are to exist in another life, and are capable, consequently, of being either rewarded or punished, in that state of retribution, according to their deeds. But nations or kingdoms can only be blessed or frowned upon in this world, as they have no existence in a future. A Being of infinite holiness and wisdom is at the head of the Universe, and rules among all the nations on earth. And it is infinitely desirable that he should rule and reign among them, as AS HE, in his sovereign pleasure, sees best. He is the disposer of events, and the sovereign Arbiter of the fate of kingdoms. He will let it be known that there is a righteous God in the earth. The honor of his providence is concerned to give ample testimony of his benevolent and righteous character, as ruler of the world. It is of incalculable importance to the interest of his moral kingdom, that he should manifest himself to be the lover of righteousness, and hater of iniquity, to all mankind. The righteous Lord loveth righteousness, and his countenance doth behold the upright. The eyes of the Lord are over the righteous, and his ears are open unto their prayers: but the face of the Lord is against them that do evil. Nations, then, will, by him, in his holy government of the world, be blessed and prosperous, generally, when virtuous and pious; and be frowned upon and punished, when vicious and profligate. Public happiness is the reward commonly of public virtue; frowns and divine rebukes follow national sins and immoralities. The wisest and most virtuous nations are usually the most prospered. Virtue walks with glory by her side. God testifies his anger against a people for their wickedness. He turneth a fruitful land into barrenness, for the wickedness of them that dwell therein. If they forsake him, he will forsake them. If they seek him, he will be found of them. He is with them, while they are with him. And Azariah went out to meet Asa, and said unto him, hear ye me, Asa, and all Judah and Benjamin, the Lord is with you while ye be with him; and if ye seek him, he will be found of you; but if ye forsake him, he will forsake you. Misfortunes and calamities, follow national immoralities and profligacy, as the natural consequence, as well as by special appointment of an all-governing Providence. Could we have, in one view, the reasons of the decline and fall of kingdoms, we should find them to be chiefly national crimes and vices. Idleness, dissipation, luxury, voluptuousness, pride, irreligion and contempt of moral principles have gradually impaired; and, at length, ruined former empires and states. The natural effect of vice, and gross crimes widely diffused among a people is to destroy them. As each individual makes a part of the nation, it is his indispensible duty, to contribute, what in him lies, to the good of the nation; and as his piety will tend to bring down blessings on the state, he is answerable to the public for his conduct as it respects religion. Many philosophers and statesmen, very erroneously conceive that religion is only an AFFAIR BETWEEN GOD AND THE SOUL, and may be necessary to a preparation for future happiness, but that it is of little or no consequence to the state, whether the Christian religion be believed or disbelieved, practiced or not practiced, protected and supported, or reproached, profaned and extinguished. The idea attempted to be disseminated, is, that every citizen is answerable only to God for his reception and practice, or rejection and neglect of it; not that he is, also, answerable at the bar of the public, and to civil society. But such are the effects of religious institutions upon men with respect to their moral character, their political state, and their domestic life; that whoever totally neglects, or impiously contemns them, has to answer for it to his God, to his neighbor, to his country, and to his family. “He partakes with other men in their sins. He associates with the enemies of mankind. He does what in him lies, to undermine the basis, on which the order and happiness of civil society is built. He teaches the false swearer to take the name of his God in vain. He directs the midnight robber to his neighbor’s house. And he delivers into the hand of the assassin, a dagger to shed innocent blood.” Hence it is worthy of remark, that the most of those daring and atrocious offenders, who, by their crimes, have forfeited life, and brought themselves to an untimely death, and the ignominy of a public execution, by their own voluntary confession, have traced their career in vice, to a profanation of the Sabbath, and total neglect or contempt of religious institutions.

We add, as a third argument, to evince the importance of religion to government and civil society, God’s special treatment of his people of old. Out of all the nations, he selected one people, who should be the depository of his revealed will, and towards which his providential conduct was, for ages, to be very singular.

The history of this people is very peculiar, and is worthy of the attentive perusal and regard of rulers, and may afford the most useful lessons to all governments. They were the care of God’s watchful providence. His hand was ever visible in what of good or evil happened to them. He warned and counseled them. He often and abundantly, tenderly and affectionately exhorted and entreated them to fear and obey him, to receive and practice the true religion. If they would be faithful to him, fear and serve him, abstain from idolatry and immoralities, he would bless them, defend them against all their enemies—lift them up on high—make them a great, a flourishing and happy nation—order favorably the seasons, cause the earth to be fruitful, and be their God, their covenant God; but if they refused to obey him, renounced his religion, would commit gross crimes, and fall into idolatry, he would bring upon them his judgments, he would punish and afflict them, give them into the hand of their enemies, distress them by national misfortunes and calamities. He uniformly treated them, as they treated him and his religion. If moral and pious, public blessings were conferred; if otherwise, judgments were inflicted; all their history is a proof of this. God, treated them, in his holy Providence, as they treated his religion. If they forsook him, he forsook them. If they sought him, he was found of them. National piety was followed invariably with national mercies. But they were only a sample of his treatment of all other nations. One grand object indeed in chusing them to be his people, was to shew all mankind, that he rules in the world; disposes of nations; and loves righteousness, and hates iniquity; that national virtue will be rewarded; and national wickedness punished. He, in general, deals with nations, in a similar manner, to what he did with the Jews, as their history fully evinces. The Lord ruleth among all nations. By him kings reign, and princes decree justice. An invisible hand guides and directs, among all nations, and in all ages. They do not rise and fall as atoms float in the atmosphere without his providence. At what instant I shall speak concerning a nation, and concerning a kingdom to pluck up, and to pull down, and to destroy it. If that nation against whom I have pronounced, turn from their evil, I will repent of the evil, that I thought to do unto them. And at what instant I shall speak concerning a nation, and concerning a kingdom, to build and to plant it; if it do evil in my sight, that it obey not my voice, then I will repent of the good wherewith I said I would benefit them.

This matter is by the decree of the watchers, and the demand by the word of the HOLY ONES: to the intent that the living may know that the Most High ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will, and setteth up over it the basest of men.—The doctrine that an infinitely wise and benevolent Being rules over the kingdoms of men, is a most important doctrine. He raises up one, and destroys another at pleasure. He afflicts and destroys, when a nation becomes awfully corrupt and wicked; and blesses, and prospers, when there is national virtue. Religion has a no less intimate relation to the present life, than to another world. Its beneficial influence affects the happiness not only of individuals, of every temper and disposition, in all circumstances and situations; but, also, of societies and nations. “As the Sun, although he regulate the seasons, lead on the year, and dispense light and life to all the planetary worlds, yet disdains not to raise and beautify the flower, which opens in his beams; so the christian religion, though chiefly intended to teach us the knowledge of salvation, and to be our guide to happiness on high; yet, also, regulates our conversation in this world, extends its benign influence to the circle of society, and diffuses its blessed fruit in the path of domestic life.”

The necessity of religion to aid government, has been felt, and generally owned by wise men, in all ages, and under all forms of government. It is well known by the learned, that the wisest statesmen, in ancient kingdoms and republics, invented and framed a religion suited to their various kinds of government, and INCORPORATED THEM TOGETHER. Their object was to civilize and reduce mankind to order and law. The idea that religion of some kind is absolutely necessary to the existence and well-being of the state or civil government; whatever be its form, especially REPUBLICS, has generally obtained among the nations. Hence in pagan countries, where there has been no revealed religion, a system of false religion has been interwoven in the particular form of the government. The reviler of religion was deemed an enemy to the state. The superstitious rites were celebrated, in much pomp, and at great expense. The design of the whole, was to strengthen the ties of conscience, and by this means to add force to government. The fears of the people were wrought upon; and to be profane towards the PUBLIC DIVINITIES of the nation was considered as an atrocious offence against the laws of the land. It will always be found, even, among the most civilized and polished, and best informed people, on experiment, to administer government, without the ties of conscience is impossible. Hence the origin of kind of religion is necessary to civil society; and where the true was unknown, politicians and impostors have invented and disseminated a false one. Even the city of Athens, learned and polite as it was, obtained this character from an ancient historian, “hospitable to the gods,” but whether by way of reproach or encomium, at this distance of time and place, cannot be ascertained. It grew into a maxim among the wisest men of Greece, “to know no man beyond the altar.”

The SCHEMES of false religion invented by the famous impostors, Zoroaster, among the Persians; Numa Pompilius, among the Romans; Mahomet, among the Arabians; and Cophal Mango among the Romans; Mahomet, among the Arabians; and Cophal Mango among the Peruvians in South America, were all intended to soften and CIVILIZE a barbarous and savage people; or to inspire them with courage; or to make them thirst for the blood of their enemies.—How deep a sense the rulers and statesmen, in ancient lands, had of the absolute necessity of good morals and some kind of religion to the safety and well-being of the state and prosperity of the nation is evident from history.

It may be acceptable to my audience, on this great occasion, to recite from authentic history, a few instances.—These shall be ancient Egypt, Persia and Rome. 1

A fourth argument to prove the benign influence of piety and morality on a free government, and society at large, is their natural tendency or operation.

That order of society is the most happy where all are obliged to be industrious; and where industry has all the benefits of its own care. Every branch of business, by which the nation is subsisted, should be diligently prosecuted, and each citizen protected in all his rights. Religion, in its natural tendency, has a most friendly and favorable influence on this order of society. That the Christian religion has this tendency, in the highest degree possible, deserves to be numbered among its great excellencies, and satisfactory evidences. It however interferes not with POLITICS, or directs to forms of government, but requires such a temper, and such a life and conversation, as will constitute quiet, peaceable, and useful citizens, in any government, and good rulers. It regards the civil and temporal, as well as the spiritual and eternal good of mankind. While this is strenuously maintained, no one can apprehend that the idea of a RELIGIOUS ESTABLISHMENT OR HIERARCHY, as in modern Europe, is either tacitly insinuated, or advocated. In our happy land, nothing resembling, even, in a remote degree, the INCORPORATION OF CHURCH AND STATE, to make one whole body politic, exists. Neither in the state or general government, as that phrase is understood, in modern Europe, and naturally imports, is there any UNION OF CHURCH AND STATE. And I trust never will be. In the various Christian nations of Europe, since the fourth century, Christianity has been variously blended with all the existing governments, let the form be what it might. Out of pious motives, and from a belief of the beneficial effect, of such a scheme of worldly policy, the church and state formed an INTIMATE ALLIANCE, OR UNION. In this way, both civil and ecclesiastical history of the nations of Europe, reciprocally aided and strengthened each other. To this source, it is apprehended, most of the abuses and perversions of, and even errors blended with Christianity, are to be traced. No friend to civil and religious freedom, can suppose, considering the love of power in all men, that the RELIGIOUS ESTABLISHMENTS of modern Europe, could be introduced to advantage in this country. The holy scriptures know of no such ALLIANCES. They are the fruit of worldly wisdom. The office of the magistrate, and the office of the minister of Christ are altogether different. CHRIST’S KINGDOM IS NOT OF THIS WORLD. In our free governments, in the United States, we have no religious establishments. Many learned statesmen, however, in Europe, and some in this land, consider this, at least, as an infelicity; and venture to predict, that in the compass of a few years, the gospel will be left unprovided for, and unsupported in this land; and of course, be driven out of it; and the name of Jesus be obliterated in the United States; or an effectual door be opened to all kinds of enthusiasm, and even atheism; and so our free government be overturned. Whether they judge right, time, the great expositor of events, must decide.

It is one of the perfect rights of man, in natural liberty, and which he may never alienate, to judge for himself in matters of religion. But as religious sentiments are very various, how far the magistrate or government ought to interfere, in matters of religion, becomes a question of great importance. While all idea of religious establishments, as understood in modern Europe, is utterly disclaimed—I submit to the hearer, whether the following observations be not built on the scripture, and reason?—The civil ruler ought to encourage piety by his own example, and to endeavor to make it an object of public esteem. Whatever is in general esteem, many will follow. The civil ruler may encourage, and promote men of piety and virtue, and discountenance those, whom it would be improper to punish.—He may and ought, again, to defend the rights of conscience, and tolerate all in their religious sentiments, when not subversive of society, and inconsistent with the rights of others.

“A legislature, may enact laws for the punishment of acts of profanity and iniquity. For however different the religious opinions of the citizens may be, yet all ought to condemn, profanity and impiety—and they ought to be punished as injurious to the commonwealth. Every government has a right to restrain by law and penalties, all acts subversive of itself.—Unquestionably, also, the civil magistrate, or the ruling part of any society ought to make provision for the public worship of God in such a manner as is agreeable to the great body of the society, though all who dissent are at the same time fully tolerated.—Multitudes would never have any religious instruction, or public worship, if the government did not interpose, to provide a way, for respectable ministers of the gospel to be decently supported, while employed in teaching the people. If a parent may and ought to provide for the instruction of his children, then the state may provide for the instruction of the whole family of the state in the great duties of godliness and virtue.” 2—Perhaps, in our own free and happy state, our government has hit upon the golden mean, of not interposing too much or too little in matters of religion. It is one of the chief glories of our civil constitution, or government that it encourages, countenances, and provides for piety and morality;–looks up with reverence to the Christian religion; and interposes for its maintenance. But there is no resemblance of a religious hierarchy in our state, or any improper interference of our government in matters of religion. What it does, in this respect, is fully warranted by the word of God, and perfectly consonant to reason.

The natural effect of religion is to secure and promote the peace, order, and well-being of society, and to give efficacy to the wholesome laws of a free government. The value or goodness of a thing is justly argued from its natural tendency. The advantages of revealed religion, as to this world, are great and interesting. It blesses very society. It sweetens every relation. It exalts every character. Exalt her, and she shall promote thee: she shall bring thee to honor, when thou dost embrace her. She shall give to thine head an ornament of grace, a crown of glory shall she deliver to thee. The community is made up of individuals. A nation is composed of all the families in it. In the same way that a family or individual is to be made happy and prosperous, is the community or nation. Virtue, consisting in the fear of God, and practice of morality, can alone make man happy. If we would, as individuals, be happy in life and death, we must feel the power, and practice the duties of religion. Would we, as a nation, enjoy the blessing of God, and be prosperous, we must fear him and work righteousness. Happy is that people whose God, is the Lord. Yea, happy is that people that is in such a case. Our help is in the name of the Lord, who made heaven and earth.

The influence of religion to render a people flourishing and happy is most powerful. From being a pious Christian, to a regular and good citizen, the transition is easy. So far as any individual is pious, so far he is happy. The same may be said of a nation. The means of private and public happiness are substantially the same. That which makes one individual or family happy, will make another happy, and the whole body politic. It is as necessary for the public to be honest and virtuous, as for an individual, in order to enjoy a divine blessing. A dissolute, idle, and profligate family must be eventually ruined, and so must a vicious nation. And all these blessings shall come upon thee, and overtake thee, if thou shall hearken to the voice of the Lord thy God.

We will show the operation of PIETY AND MORALITY, in producing public happiness, in a few important instances.—What is the natural effect of a full belief of the being of God on the mind of men? Here all religion begins. He that cometh to God must believe that he is, and that he is a rewarder of all them that diligently seek him. A disbelief of him, and his governing Providence, as ever been found, to lead to all manner of wickedness, excess, and dissipation. By necessary consequence, a belief of these will restrain the vile passions of man. He will fear to violate his oath, to commit murder, or robbery, theft, or any other secret or open crime. Conscious that he cannot hide his crimes from an omniscient and holy God, he will dread his anger, and refrain from open transgressions of his law. This belief, in a nation, will necessarily have an astonishing effect to preserve, amid all classes, a degree of order and decorum, and to prevent those heinous crimes, which destroy public happiness, and bring down on a nation the judgments of heaven.

Again; The knowledge of the various divine attributes, both natural and moral, has a direct tendency to produce great effects on the public character of a nation, and by necessary consequence, on civil government. Take away a sense of these, and you remove the very foundation of public morals. A sense of the divine perfections, power, wisdom, universal presence, independence, self-existence, holiness, goodness, justice and truth, leads to happy consequences, both on the mind and life. Realizing these glorious attributes, we shall dread to offend the divine Majesty, and feel our obligations to serve and obey HIM, who is possessed of such transcendent excellencies. Sensible that he is the greatest, best, and wisest of all beings, our Creator, Preserver, Benefactor, Lawgiver, Sovereign Lord of the universe, Disposer of all events, and Ruler among the nations of the earth, we shall continually aim to please him by a life conformed to his will; by a reverential fear; by seeking daily his blessing; by thankfulness for mercies received; by owning his providence and government; and by looking to him for general health, for fruitful seasons, for defense and protection in times of national danger, and public calamities.

Further; A belief of accountableness, and of the retributions of eternity has a wonderful influence on the public mind, to excite both hope and fear, two of the most powerful springs of action in the human frame; the one to restrain from vice, and the other to urge us to virtue. This belief is essential to the Christian religion. And the astonishing influence which it must have on the MORALS of a community, all are competent to understand. The very idea of our accountableness at the bar of a righteous and impartial Judge, insensibly leads to a fear, lest by sin, we offend and provoke him. Knowing, that when we shall have done with time, we must render an exact account of all our thoughts, words, and actions, is one of the most powerful considerations to induce to a regular and sober life. No doctrine is more either solemn or affecting, than that we must all appear, rulers, and ruled, before the judgment-seat of Christ Jesus, and give an account of the deeds done in the body, according to what every man has done, whether it be good or bad. Add to this, the exact retributions of eternity, of endless glory, or endless misery; and no motive can possibly have more weight to induce to a circumspect behavior, to prevent or reclaim from gross wickedness. In another world, ah my brethren! We shall be rewarded, or punished precisely according to our moral and religious character, to our good or evil deeds.—The more good we have done, in our place and station in life, or been the active means of, the more distinguished will be our reward: and the more sins we have committed, and vices, immoralities, and irreligion, we have been the means of others practicing, the heavier will be our condemnation, and the deeper our misery.—How solemn and affecting a doctrine! How well calculated is the full persuasion of it, to produce most beneficial effects on the public mind and morals; on all classes of people! And, of course, to prevent those gross abominations, which lay waste and destroy society. He, therefore, is doing the greatest conceivable mischief to the community, who attempts to rid the mind of the fear of punishment, or to banish the hope of reward, or to render doubtful the accountability of men to a future tribunal, and the immortality of the soul.

It is obvious still, further, to observe, that the constant exercise of divine worship, and the feelings of our dependence on God, and the infinite obligations of gratitude we are under to him for national, as well as personal blessings, have an inconceivable influence on civil government, and the temporal interests of a people. There can be no religion among a people, where the worship of the Supreme Being, public, social, and private, is wholly neglected; and his institutions set at naught. Public worship, at the religious instructions of the sanctuary, and the holy Sabbath are absolutely essential to the very being of Christianity. Every willful and total neglecter and contemner of these, is contributing, although he may think not of it, his proportion of influence to annihilate religion. The prevalence of religious principles, and the practice of religious duties among a people are essential to the morals; and the morals of the people are essential to their national prosperity. The decline, therefore, of religion in a nation, is an awful presage of evil impending that nation. When the worship of God, in its several forms, is disesteemed and neglected, when the dispensation of the word in the sanctuary is in disrepute, when the Lord’s day is vilely abused, hen morality will fail. Industry, learning, education, peace, the social duties, and with them, all public happiness will fail—RULERS will be disrespected—wholesome laws be trampled upon—and unfounded and unreasonable clamors be excited against the government. The institutions of religion, and constant exercise of divine worship, not only tend to harmonize the sentiments of the people, and to promote amity, civility and humanity, but, also, alone support the interests of morality. If a people reverence and statedly attend upon the ministrations of the gospel, feel their dependence on God, on the wisdom, goodness, and bounty of his Providence for general health, fruitful seasons, and success in their lawful pursuits; if they feel their obligations to be thankful for mercies received, and of humiliation and penitence under his frowns and righteous rebukes, they will be disposed to such a conduct as will subserve their highest temporal interest. Nay, I go farther and affirm, that, merely performing divine service, and expressing, in prayer and praise, gratitude to God for all his blessings, national and private, and acknowledging our entire dependence on his providential government, have a happy effect, both on the mind and morals of the public.

Moreover, it is an expressly commanded duty of the gospel to pray for civil rulers, from the highest to the lowest, and for all in authority over us, for the peace of government, for public order and stability, for good laws to be enacted, and that there may be obedience and submission to them, among all classes of people. I exhort that first of all, supplications, prayers, intercessions, and giving of thanks be made for all men. For kings, and for all that are in authority, that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life, in all godliness and honesty. For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Saviour. How reasonable and benevolent the Christian religion! It requires of all, peace, friendship, faithfulness, good will to man, to all men, and the forgiveness of injuries, GODLINES, AND HONESY. All are to seek blessings for one another, for all orders, and classes, rulers and ruled, that the administrators of government may be guided by wisdom, be kept from wrong measures and counsels, that we may all lead quiet and peaceable lives, in all godliness and honesty. Godliness and honesty are united. Piety and morality go together. MERELY PRAYING, in daily addresses to the throne of grace, for all in authority, for civil government—for good laws—for freedom, civil and religious—for a spirit of obedience to good laws—for a wise use of civil liberty has a direct and powerful tendency to honor civil authority, good laws, and good government; and, at the same time, to prevent unfounded jealousies, evil surmises, variance, hatred, calumny, sedition, pestilent ambition, mean and disingenuous artifices and intrigues against government. The gospel, alone, establishes on a due basis, the rights of man, liberty and equality of the rational kind, and fraternal sentiments. The gospel is an enemy to all tyranny and oppression, slavery and arbitrary government. How wise and suitable that we should pray for all men, when our morning and evening oblations ascend to heaven: and that all orders of the community, may lead a quiet and peaceable life, in all godliness and honesty. Would all classes of people comply with this one duty, the effect on government, on society in all its interests, would be most salutary. Prayer has a causal influence in procuring the blessings devoutly implored. Piety is indeed the strength of morality. Take away the former, and the latter will wither and fade, as a tender plant, from which you remove moisture and nourishment.

The practice of moral duties, as already remarked, is an essential part of the true religion. No man can be a really religious man, without morality. There may be hypocrisy, feigned pretences, and external observances of religion, where there is no morality, or even where heinous sins are allowedly committed; but there can be no real heart-religion, without the strictest regard to every moral duty. A man can no more be a Christian, or have the evangelic graces and temper, without morality, than he can be a Christian, without piety, or faith towards our Lord Jesus Christ, and repentance towards God. Those, therefore, who have attempted to separate piety and morality, or faith and good works, have done an unspeakable injury to religion, and greatly disserved the cause, which they meant to promote. They have, most unwisely and unhappily, crated a prejudice against either faith on the one hand, or good works on the other, and tempted some to disbelieve the usefulness of the gospel as to our present temporal well-being. Moral duties are as obligatory as devotional, and have the most friendly aspect on government, and the general welfare of society. This might be evinced, most clearly, from a large and critical examination of them in detail. All that the limits, to which I am confined, will permit, is briefly to enumerate some of the moral duties, which constitute an essential part of religion, and examine their tendency in respect to the public mind and civil government, in general. The several moral duties, which will be concisely mentioned and argued upon, are truth, righteousness between man and man, humanity and love of enemies, kindness and compassion, meekness, candor and humility, sobriety, temperance and self-government.

The religion, enjoined upon us by an infinitely wise and holy God, who perfectly knew what would be most for our good, in time and in eternity, and who would prescribe no duty to be done by us, which had not a happy tendency on society, requires strict veracity. It teaches us that truth between man and man, with which is inseparably connected faithfulness, is universally biding; obligatory at all times. It forbids all evil speaking and falsehood, from perjury down to all mental reservation, or equivocation. It allows us to depart from truth, on no occasion, even the most pressing, and from no temptation. How important a moral duty this is; and how necessary even to the existence of public happiness, all must be sensible, who give themselves leisure to reflect on the subject. What dependence can be placed, or safety had in the lying tongue, in perfidious treacherous men! When a man is habitually unfaithful, and pays no regard to truth, in his words, we can repose no confidence. There will be no binding power in an oath. In a multitude of cases, right cannot, therefore, be obtained.

Religion, also, requires strict justice, in the various dealings, among men, in every government. This includes, integrity, equity, honesty. The heart must be upright, and the whole of the conduct be regulated y inflexible righteousness. Justice between man and man is the pillar, on which rests the welfare of society. We may never be guilty of injustice and dishonesty to others: never oppress, extort from, or injure them: not in wish or act injure them in their good name, property, or right; all orders and classes of citizens are to observe all the laws of righteousness towards each other. JUDGES, on the BENCH, are to administer, impartially, without favor or affection, justice. The most of the laws indeed of society are to prevent dishonesty, and keep people upright in their intercourse with each other. So selfish, so full of malicious passions, is human nature, that even heavy penalties, exemplary punishment, and courts of justice cannot keep people from deviating from the rules of equity, in their connections in trade and business. A man, who has religion in his heart, will constantly and uniformly aim to walk in all HONESTY, as well as GODLINESS, though he may sometimes mistake the nature of justice; or through a selfish bias, or strength of temptation, be carried away from it. For no man is free from sin. How much to the honor, peace, and interest of the community, justice between man and man is, all must feel. An unjust and dishonest, cannot be long a flourishing and respected people. A national observance of strict equity will tend to prevent wars—bloodshed—and costly disputes; as well as to preserve national respectability, independence, and honor.—In a free, perfectly republican government, recourse by the citizens is too often had to the LAW and COURTS to decide on their claims. A litigious spirit should be discountenanced.

Religion, tends, further, to exalt a people, and to make them prosperous, as it censures and condemns all idleness, dissipation, excess, and vicious amusements; and requires of man INDUSTRY, in some lawful calling. It requires an attention to the duties of our several callings and stations, and a right improvement of all our time, talents, and opportunities to do good. How directly this contributes to wealth, and competency, to peace, contentment, and order, the least reflection is sufficient to convince us. Can a people be happy, or civil government be well supported, where idleness, murmurs, discontent, factions, vicious amusements, dissipation, debauchery, and luxury prevail? If a people or individuals would be either wealthy or virtuous, they must be industrious.—The prosperity of religion is, then, the prosperity of a nation.

We add, again—religion requires of all, humanity, kindness, candor, compassion to the poor, and all THE OFFICES of benevolence and tenderness. We are to be patient and forbearing under losses and injuries,–to be mild and forgiving in our temper,–to be gentle and condescending—to be obliging to all.—Conscious how often we ourselves offend—how liable to mistakes—to unreasonable prejudices, we shall feel how much we need candor from others. We are required, by our holy religion continually to exercise compassion to the poor;–sympathy to the afflicted;–kindness to the unfortunate;–patience to the forward;–humanity to all;–to think evil of no man without a justifiable cause;–to speak evil of no man unnecessarily;–to be bitter, malicious, and envious to no man;–to slander, abuse, oppress, and ill-treat no man: but to extend our good offices to all—and by a patient continuance in well-doing, to seek for glory, honor, and immortality. How happy does the practice of these mild and amiable virtues tend to make society, to sweeten the intercourse, and cherish the civilities and charities of human life!

The gospel, also, no less strictly and solemnly enjoins upon all classes and ranks, ruler and subject, high and low, the moral duties, which relate to self: sobriety, temperance, purity, and the due discipline of the passions. It never allows us to do anything with sobriety—the great duties of temperance, purity, meekness, and humility. The two Christian tempers of meekness and humility, would prevent anger, wrath, revenge, hatred, envy, pride, and all the violent passions; and of course would prevent all murder and dueling; crimes, of a scarlet color, though alas! fashionable, where the fear of God, and the love of a Redeemer have no place, or little influence. It cannot but be apparent to all, that the duties now mentioned, more than is generally conceived, contribute to secure one’s own, and to promote the happiness of others. A larger and fuller elucidation would prove the point before us, the beneficial influence of religion on civil government and national prosperity so as to stop the mouth, one would imagine, of the most bitter reviler of piety, and hardened gainsayer.

It is only subjoined, that religion has a powerful influence on public happiness and civil government, as it nourishes an ardent wish and desire to advance all useful arts, and the sciences. It is auspicious to everything, which can adorn life, or dignify human nature. It cannot be diffused, where there is no civilization or knowledge, or even exist. It, therefore, always consults how human learning may be promoted, and displays its excellence in the education of children and youth. The welfare of a nation rests much on the right education of children. As religion enlarges our views and expands the soul by the grandeur of its objects, and sublimity of its doctrines, so it affectionately regards the education of children.—It devises liberally for the teaching of the rising generation. It is unwearied in exertions for the public good. Peculiarly happy is OUR OWN STATE in having such ample provision for the education of the children of our citizens. And greatly have the legislature honored themselves by their attention to this important OBJECT. We cannot be long either a pious or free people, if this object be neglected.

It was the saying of a great orator and statesman of antiquity, “that the loss which the community sustains by a want of education, is like the loss which the year would suffer by the destruction of the spring.” If the bud be blasted, the tree will yield no fruit. If the springing corn be cut down, there will be no harvest. So if the youth be ruined through a fault in their education, the community sustains a loss which cannot be repaired. For it is too late to correct them, when they are spoiled. 3 Thus, plain is it that religion, free from superstition and enthusiasm, has a direct and powerful influence to secure and promote the public happiness, and to aid and bless civil government.

In the manner above illustrated, is Christianity propitious to the dearest interests of society. It prescribes rules to regulate the conduct and conversation of all, in every station, from the highest to the lowest. Its benevolent spirit wishes well to all; and requires all, to direct supremely their whole strength to promote the public good—to do as they would be done by—and forbids them to make self their chief end, on the pain of the divine displeasure, here and hereafter. What wise instructions does it give to all mankind, whatever be their station, to kings and subjects—to magistrates and people—to citizens and soldiers—to the church and world.—How important that we contemplate and adopt the means, by which free states may be happy. “Of the states called Republics, in ancient or modern times, all have lost their independence or ceased to exist, except the United States of America. As exhibiting to mankind one example of Republican government, we now stand alone on the globe, surrounded by ruins.” Were we to enquire into the decline of free states, we should find it owing to the general prevalence of vice among all classes of people, to luxury, voluptuousness, dissension, corruption in the exercise of the elective franchise, and boundless ambition, to a total disregard of religion.

The declarations of scripture are abundant to this purpose. If any should be inclined to doubt the friendly influence of true religion, an essential part of which are pure morals, on the public happiness, after all the arguments above advanced, they are requested candidly to weigh the proofs from the sacred pages. The text, and all the blessings and curses pronounced, in the verses next following, down to the 45th verse prove the doctrine. Hear the tender words addressed to the people of Israel on account of their neglect of God and his laws. O! that they were wise, that they understood this; that they would consider their latter end! How should one chase a thousand, and two put ten thousand to flight. Agreeably to this are the affecting words uttered by the Psalmist. O! that my people had hearkened unto me, and Israel had walked in my ways. I should have soon subdued their enemies, and turned mine hand against their adversaries. Their time should have endured forever. I should have fed them also with the finest of the wheat, and with honey out of the rock should I have satisfied them. What a rich promise is made in Isaiah?—Thus saith the Lord thy Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel, I am the Lord thy God which teacheth thee to profit, which leadeth thee by the way thou shoudst go. O! that thou hadst hearkened to my commandments! Then had thy peace been as a river, and thy righteousness as the waves of the sea. Thy seed also had been as the sad, and thy name should not have been cut off, nor destroyed before me. See also the threatenings denounced by Jeremiah against a degenerate and corrupt people. Though Moses and Samuel stood before me, yet my mind could not e towards this people; cast them out of my sight, and let them go forth. And it shall come to pass, if they say unto thee, whither shall we go forth, then thou shalt tell them, thus saith the Lord, such as are for death, to death, and such as are for the sword, to the sword, and such as are for the famine, to the famine, and such as are for the captivity, to the captivity. Thou hast forsaken me, saith the Lord, thou art gone backward; therefore will I stretch out my hand, and destroy thee; I am weary of repenting. A people are said to be happy, who have God, for their God. Happy is that people that is in such a case, yea, happy is that people whose God is the Lord. Righteousness is said to exalt, and sin to reproach a people. Righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach of any people. The happy effect to a people of virtuous rulers, and unhappy effect from wicked rulers are thus stated. When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice: but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn.—It is needless to recite more proofs from the word of God. Suffice it to say, that a wise and holy God, in his providence, conducts towards a people according to their treatment of him; and that the people of Israel were constantly prosperous or afflicted, as religion flourished or declined among them; and that he deals with all nations, to whom to whom he has revealed his will, in a similar manner. If we were called, to offer an apology for religion, before such an audience, the subject above discussed, would be the BEST: and, indeed, is an ample vindication of it against all the objections and cavils of infidelity. That it hath been, alas! abused to the purposes of superstition, and been employed to support ecclesiastical and civil tyranny, cannot be denied. But what blessing of heaven, has not often, by the corrupt passions of man, been abused?

Men and brethren, preserved by an indulgent Providence, in our various ways and stations, thro’ another year, while many of our friends 4 are removed by death from the theatre of the world, we have the opportunity of assembling on this joyful Anniversary, agreeably to the wise institution of our fathers, DEVOUTLY TO IMPLORE the blessings and smiles of Almighty God on the NATION, of which we are a part,–on OUR STATE—ON OUR RULERS—ON THE LGISLATURE—and ON ALL OUR CITIZENS.

And, let not the truths, to which we have been attending, be with us, mere speculation. Let us endeavor to reduce them to practice. Let us never suffer our political principles to clash with the principles of religion. Let us make it our supreme object to accept of the offered salvation, and obey the precepts of Jesus Christ, our divinely benevolent Redeemer, to believe the doctrines, and conform to the laws of his religion, and always seek the Lord, then he will be found of us: For public happiness is of him. Our help is in the name of the Lord, who made heaven and earth. By so doing we shall draw down blessings on our nation, still more valuable, than we have already enjoyed. The blessings which we have enjoyed, are such as ought to inspire us with lasting gratitude to the great Author of every good and perfect gift, the wise RULER among the nations, who setteth up one, and pullet down another. Through the good hand of our God upon us, we enjoy yet our liberties, and a free, equal, republican government. The same spirit of rational liberty, removed far from all licentiousness; the same love of our country, the same desire to enjoy the blessings of both civil and religious freedom; which were so conspicuously manifested, when our independence was established, should still operate with the same vigor. The grand question, which is equally interesting to all, is how may this great nation be long free, prosperous and happy; our rights; civil and religious, be enjoyed by all classes of citizens; our favored republic be perpetuated; saved from the evils, which have overwhelmed all past republics, buried the people under oppression and tyranny, and left them to mourn the loss of that liberty, which they never could again recover. History faithfully records by WHAT MEANS, free states have been ruined. May we have wisdom to receive the lessons of experience. In the United States, we have a free government. Few nations have enjoyed the opportunity of taking up government, upon its first principles, and chusing that form, which is best adapted to their situation, and most productive of their public interests and happiness. The government of the United States approaches the nearest to the social compact of any that history can furnish. It is as well, or better, perhaps, calculated for promoting the happiness, and preserving the lives, liberty, and property of the citizens, than any ever yet framed by the wisdom of man. Placing liberty in the custody of the people, it wisely guards against anarchy and confusion, on the one hand, and tyranny and oppression on the other. It is framed upon an extent, not only of civil, but of religious liberty, unexampled in any other country. The sacred rights of conscience are so secured, that no citizen is molested on account of his religious profession and sentiments. How should this consideration endear it, to its citizens, and induce them to regard it with a veneration and affection, rising even to enthusiasm, like that which prevailed at Sparta and at Rome. Happy people whose lot has fallen to them in pleasant places, and who have a goodly heritage! Happy people! If we have wisdom and virtue to improve aright, the advantages which we enjoy! Blessed be God who hath isited and redeemed his people: who hath called them to liberty, and granted them a free government! We have attempted above, to prove from reason and scripture, what are the certain and infallible means of national glory and prosperity; of establishing and perpetuating public happiness; and these are the prevalence of religious and moral principles, and practices, piety and morality. The great object of civil rulers, of those who make laws, or administer justice, or preside over the public interests, from the chief magistrate to the lowest, should be to render, as far as possible, the state happy, to advance the public good, the order and well-being of society. Consulting the annals of every government and people, we shall find, that arms and wealth, have been considered by most nations, and most politicians as the principal means of securing to a people, national glory and happiness. Piety and morality have been generally overlooked. If the arguments above urged, be conclusive, the civil ruler will feel it his duty, to endeavor to make the people happy, by making them virtuous. Much may he do, by example, by promoting men of good moral and religious principles and lives. We have been happy, in having from the beginning, even to the present day, a series of chief magistrates, who have been not only an honor to the state, but ornaments to our churches. May such a series be still continued, of EXCELLENT MEN, and EXCELLENT RULERS. Not only those clothed with civil offices and power, but the ministers of the glorious gospel of the Son of God, may, in the light of this subject, see their duty. The object of their office is to promote the spiritual and eternal good of man, his well-being in this world, and his future blessedness. Their business is to minister in holy things, avoiding all subjects foreign to their sacred calling. It is our business to study and teach Christianity, and thus to promote the civil, as well as spiritual good of man. What a noble employment! To fidelity and zeal, the motives of religion call us; and, also, motives of regard to our country. From love to religion and the souls of men, from a regard to the prosperity of our state and land, let us diligently study the evidences, nature, doctrines and duties of Christianity, and inculcate them with all plainness, assiduity and perseverance.

A consideration that we have but a short period, in which to labor in the gospel ministry, may well animate us to greater, and still greater zeal. We cannot continue long by reason of death. Since the last anniversary of this kind, several of our brethren in the Christian ministry, in our state, have closed life, and been called off from their labors. Let us drop a tear over their memory, and prepare to follow them to the silence of the tomb! 5

All this numerous assembly are deeply interested in the truths which I have illustrated. Men and brethren—you cannot be happy as individuals, but in the way of piety and virtue. You have not only the motive of eternal happiness, to choose the Lord for your God, but the motives of the peace, good order and happiness of the people, as a body politic, and the general happiness of the state. In a republic, all authority is derived from the people; and such as they are generally, such will be their representatives, legislators and civil authority. In order for the prosperity, and even existence of a FREE GOVERNMENT, there must be virtue and good morals among the great body of the people.—Where the elective franchise is enjoyed, those who rule, will, in character, be the same as the ruled. Let all make it their first and highest concern, to devote themselves to a life of piety, to the fear, love and service of God. And remember, your day of probation is rapidly passing away. Soon, at the longest, you will all be removed from earth, and go down to the dust of death. It is, therefore, of infinite importance that you embrace the gospel, receive a Saviour, who died for you, and prepare for a blessed immortality. How glorious the end of true religion! How desirable its effects!

We are happy, in being now met together in this large assembly, on this great occasion, and, for the first time, in this beautiful, elegant, and magnificent temple of worship, erected at great expense, and by the commendable exertions of this people.—But before the next return of this Anniversary, how many, who are now here, will belong to the great congregation of the dead, and be fixed unalterably in their eternal state! Who—where now in this Assembly are the persons thus destined so soon to another world.—Ah!—we all must travel the same dark road of death. What one individual here present can say he is not one of this number? Are we all prepared for our eternal state? In that state we shall all be soon found, while other busy mortals like ourselves, will take our places on this stage of life.—Never—never shall we all meet together again, till we meet with the assembled universe, before the tribunal of our final Judge.

The God of all grace, enable us so to live, that we may, at that solemn period, be found on the right hand of our Judge, and by the sentence of his mouth, have our portion assigned us with the general assembly and church of the firstborn, which are written in heaven, with the spirits of just men made perfect, with an innumerable company of angels, with Jesus the Mediator of the new covenant, and with God the Judge of all.

Blessing and honor, and glory, and power be unto him that sitteth on the throne, and unto the Lamb for ever and ever. AMEN.

Endnotes

1. By what mysterious art did ancient Egypt subsist, with so much glory during the period of fifteen or sixteen ages? By a benevolence so extensive that he who refused to relieve the wretched, when he had it in his power to assist him, was himself punished with death; by a justice so impartial that their kings obliged the judges to take an oath that they would administer impartial justice, though they, the kings should command the contrary; by an aversion to bad Princes so fixed as to deny them the honors of a funeral; by entertaining such just ideas of the vanity of life as to consider their houses as Inns, in which they were to lodge, as it were only for a night; and their sepulchers, as habitations, in which they were to abide for many ages; for which reason, they united, in their famous Pyramids, all the solidity and pomp of architecture; by a life so abstemious that even their amusements were adapted to strengthen the body and improve the mind; by such a remarkable readiness to discharge their debts that they had a law, which prohibited the borrowing of money, except on the condition of pledging the body of a parent for payment; a deposit so venerable that a man who deferred the redemption of it was looked upon with horror; in a word, by a wisdom so profound that Moses himself is renowned in scripture for being learned in it.—See Diodorus, Siculus, and Herodotus, Liber 2—The Persians, also, obtained a distinguished place of honor, in ancient history, by considering falsehood in the most odious light, as a vice the meanest and most disgraceful; by a noble generosity, conferring favors on the nations they conquered, and leaving them to enjoy all the ensigns of their former grandeur; by an universal equity, obliging themselves to publish the virtues of their greatest enemies; by educating their children so wisely that they were taught virtue as other nations were taught letters. The children of the royal family and of the nobles were at an early period of life, put under the tuition of four of the wisest and most virtuous statesmen. The first taught them the worship of the gods; the second trained them up to speak the truth and practice equity; the third habituated them to subdue voluptuousness, and to enjoy real liberty, to be always masters of themselves and their own passions; the fourth inspired them with courage, and by teaching them how to command themselves, taught them how to rule over others.