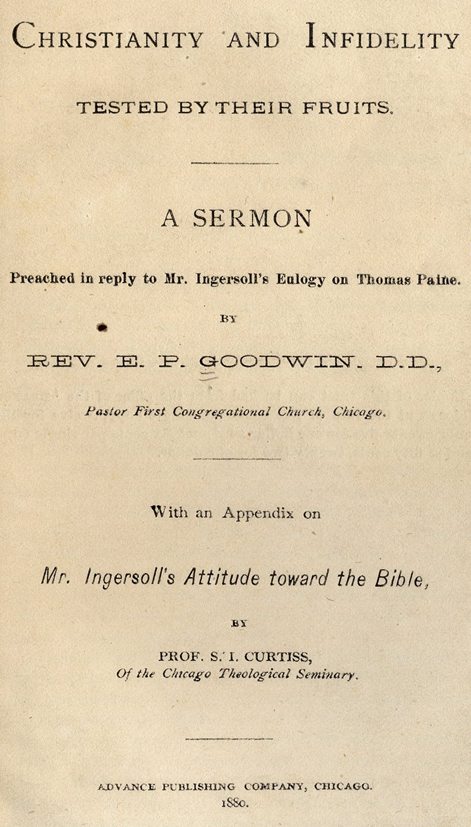

This sermon was preached by E. P. Goodwin in 1880 in Chicago.

Christianity and InfidelityTESTED BY THEIR FRUITS.

A SERMON

Preached in reply to Mr. Ingersoll’s Eulogy on Thomas Paine.

BY

REV. E. P. GOODWIN, D.D.,

Pastor of the First Congregational Church, Chicago.

With an Appendix on

Mr. Ingersoll’s Attitude toward the Bible,

BY

PROF. S. I. CURTISS,

Of the Chicago Theologial Seminary.

CHRISTIANITY AND INFIDELITY TESTED BY

THEIR FRUITS.

Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them.—Matt. vii: 20.

Teachers of men are like trees. We can no more trust the words and theorizing of the one, than the leaves and blossoms of the other. But when fruiting time has come we shall have tests that never fail. Grapes do not come of thorns, nor figs of thistles. Every good tree will have infallible witness in good fruit, and every evil tree in evil fruit. Just so of men who set up for prophets. When their doctrines have come to fruitage, there will be in the quality of that fruit, according as it is good or evil, the infallible test of the quality of what has been taught.

This is our Lord’s canon of proving things. And he bids us stand in the ways and challenge whatever claims authority over our hearts and lives. We are not to accept a teacher, because he has the look of an apostle. We are not to accept his doctrine, because it charms the ear and gives great promise of blessing. We are to demand as prime conditions of our acceptance a showing of fruits; results wrought, whereby the doctrine which appeals to us is unequivocally demonstrated to be that which exalts God and blesses men.

Of course Christ and his teachings must take the same test that is applied to other teachers and other doctrines. No question is a fairer one with which to meet the claims of Christianity, than, What fruits has it to show? Have its teachings made men better or worse? Have they tended to emphasize and exalt truth, purity, justice, benevolence, to secure the well-being of individuals, communities, nations, or have they tended to beget untruth, impurity, injustice, selfishness, cruelty, tyranny, and thus heap upon men increasing mischiefs and woes? And this is the question between Mr. Ingersoll and the ministers and churches he assails so bitterly in his glorification of Thomas Paine. We of the ministry and the churches stand upon the Bible as the divinely-inspired and hence divinely authoritative word of God. We affirm that this book sets forth the true character of God, the aims and methods of his moral government, the scheme of his devising, whereby shall be secured his own highest honor, and the highest well-being of his creatures. We affirm that upon men’s believing upon the crucified Son of God therein set forth as the Savior of men, depends their salvation. We affirm that only as men accept the doctrines of this book, and order their lives thereby, can they attain individually to the largest measures of intellectual and moral development; or as associated together, enjoy the highest social security, prosperity, and happiness; or as a nation make sure of real greatness and lasting glory.

CHARGES AGAINST CHRISTIANITY.

Mr. Ingersoll denies all this. He declares that Christianity is a “superstition,” a bundle of “ancient lies.” That the doctrine of salvation by faith is “infamous.” That the church is “ignorant, bloody, relentless.” That it “confiscates property,” “tortures,” “burns,” “dooms to perdition” all who are outside of its pale, and does it with supreme delight. That religion “puts fetters” on man’s intellect. That it is “destructive of happiness,”—a “hydra-headed monster, thrusting its thousand fangs into the bleeding, quivering hearts of men.” That it “fills the earth with mourning, heaven with hatred, the present with fear, the future with fire and despair.” And over against this Mr. Ingersoll sets as the true religion, the grand panacea of all human ills, the scheme of infidelity. “Infidelity,” he says, “is liberty.” It is this which “frees men from prison; this which civilizes; this that lights the fires on the altars of reason, that fills the world with light; this that opens dull eyes, brings music into the soul, wipes tears from furrowed cheeks, destroys from the earth the dogmas of ignorance, prejudice, and power, and dries from this beautiful face of the earth the fiend of fear.”

This is a clear, sharp issue. Mr. Ingersoll stands before our text and says, “Christianity cannot take its own test. It claims to yield grapes, but when the truth is told, it has only tearing, torturing thorns to show. It claims to be a gentle, innocent sheep, but is nothing other than a ravenous, blood-thirsty wolf in disguise. The only genuine grape-vine, the only true sheep, is the doctrine which I teach, which I learned of my master, the one great unequaled teacher of the ages, the apostle of liberty, the light and hope of the world—Thomas Paine.” 1

THE VERDICT OF HISTORY CHALLENGED.What I propose is to apply this test of the text to both these schemes; to set Christianity and its fruits side by side with infidelity and its fruits, and see whether Mr. Ingersoll has told us the truth. It does not concern my purpose to speak particularly of Thomas Paine, and I shall not stop, therefore, to consider at length Mr. Ingersoll’s apotheosis of him. He is entitled to his opinion, and so are we to ours. But I must confess to have read his oration with amazement. I had always supposed hitherto that there were some other unselfish, pure-minded, liberty-loving men in those old times, who had something to do with originating and carrying to success the scheme of American independence. But it seems we have all been mistaken, and history has been mistaken, and so for a hundred years the country has gone on heaping eulogies upon men that never deserved them. Somehow, this terrible despot and fiend of Christianity has contrived to falsify the records, blind the people, and keep hid away in its awful dungeons of disgrace and infamy the one purest hero, the one pre-eminent magnate of that glorious epoch. It does not exactly appear how this was done. It does not appear that any other patriot-infidel was doomed to like dishonor. Nevertheless, it has come to pass, that as to this man, the “first to perceive the destiny of the new world,” “the man that did more than any other to cause the declaration of Independence,” the very Achilles of the revolution, without whose voice and sword, apparently, everything would have come to naught—the whole nation has for a century been reading and re-reading its history, and hardly made mention of his name! What strange, what base ingratitude is this! For statesmen, historians, orators, poets, to keep sounding for decade after decade the praises of Washington and Jefferson, and Franklin, and the Adamses, and ever so many more, and yet never to have lifted one acclaim for the hero that overtopped them all! Evidently Mr. Ingersoll’s spectacles should have come into use long years ago.

Listening to this arraignment of history, one cannot feel sure that any of its so-called verdicts are to be trusted. How do we know that, as a nation, we have not been guilty of like injustice and tyranny in the judgments that have been passed on Jefferson Davis and Benedict Arnold? And who shall be quite sure that not only they may yet be rescued from the infamy that now envelops them, but even Judas Iscariot may prove to have been calumniated by this relentless tyranny of a misnamed gospel, and take his place alongside of Arnold and Paine among the stars. Here, at least, is a new field in which Mr. Ingersoll may acquire laurels.

PAINE AND AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE.

As to the claims put forward in behalf of Mr. Paine’s leadership in securing our national independence, I cannot refrain from a passing word. There is no proof whatever that any injustice has ever been done Mr. Paine in the estimate of his services by our historians. Mr. Ingersoll has not added a single fact to those well known before. No doubt Mr. Paine rendered valuable service, especially with his pen, in the interests of freedom; no doubt he deserved all the encomiums and substantial rewards he received at the hands of State Legislatures and of Congress. So far as I know, no one has ever disputed this. But when Mr. Ingersoll attempts to go beyond this, and hold Mr. Paine up as the “great apostle of liberty,” the “first to perceive the destiny of the new world,” as “doing more to cause the declaration of Independence than any other man,” and declares his pamphlet, entitled “Common Sense” the “first argument for separation” of the colonies for the mother country—he goes vastly beyond the facts. He may believe Mr. Paine entitled to all the credit he claims, but he certainly can not prove it. The truth of history is not to be overborne by a lawyer’s specious plea, nor is its voice to be drowned beyond the passing moment, by the applause evoked by the wit and eloquence of a gifted orator.

The first significant fact is, that there is no proof whatever that Paine came to this country with any political purpose. He lost his place as exciseman, obtained an introduction to Benjamin Franklin, then U. S. Minister in England, who had received so many applications that he had written a tract giving information about America—and from him secured a note of introduction to Franklin’s son-in-law, Bache, commending him as needing employment, and so far as he could judge, worthy of confidence. He reached this country in December, 1774, and through Mr. Bache’s influence obtained employment as the editor of a magazine. And this is all there is of his coming. So far as appears, it was purely a matter of getting daily bread. 2

On Jan., 1776, when he had been in the country barely a year, he published his pamphlet. Mr. Bancroft says he did it at the suggestion of Mr. Franklin, who had then returned from England, hopeless of securing any peaceable adjustment of the difficulties between the colonies and the home government. The pamphlet was timely. It was written in a clear, vigorous, and telling style, took ground boldly in favor of independence, and was without doubt greatly effective in urging forward the cause which it championed. But this is all that can be claimed for it. 3

Franklin had long cherished and uttered the same views, and so had Patrick Henry, James Otis, both the Adamses, and many others. Indeed, ever since the passage of the Stamp Act there had been a growing conviction among nearly all the patriotic men of that day, that the separation of the colonies and the establishment of an independent government was inevitable—a mere question of time. 4 And at the date when this pamphlet appeared, this conviction was the dominant one among a vast majority of the people, and with reason. Boston port-bill was a fact, and had stirred the blood of all the colonists. Franklin had been insulted before the king’s privy council, and that made the red heat white. More than all, Lexington, and Concord, and Bunker Hill had been fought, and the smell of powder was everywhere in the air. The king had refused to listen to the second remonstrance of the colonies against taxation without representation, and had issued his proclamation for the suppression of rebellion. John Adams’ wife, Abigail, hearing that proclamation, stopped her spinning-wheel, and wrote to her husband:

“This intelligence will make a plain path for you, though a dangerous one. I could not join today in the petitions of our worthy pastor for a reconciliation between our no longer parent but tyrant State, and these colonies. Let us separate! They are unworthy to be our brethren. Let us renounce them! And let us beseech the Almighty to blast their counsels, and bring to naught all their devices.” 5

And Mr. Bancroft says of Mrs. Adam’s appeal, “Her voice was the voice of New England.”

James Warren, speaker of the Massachusetts legislature, writing to Samuel Adams, had said, “movements worthy of your Honorable body are to be expected; a declaration of independence, and treaties with foreign powers.” 6

Jefferson had said, speaking of the Stamp Act and kindred legislation, “I will cease to exist before I will submit to a connection with Great Britain on such terms as the British Parliament propose; and in this I speak the sentiment of America.” 7

And still beyond this, Franklin had introduced into the Continental Congress his plan for a confederation of the colonies. 8

This was the state of things when Mr. Paine’s utterances were put forth. They were opportune and helpful. But chiefly as inciting to an earlier inauguration of the conflict that was sure to come.

Washington was at the head of the army—Boston invested with 10,000 men—Norfolk had been burned—the whole country was ready to burst into a flame.

Doubtless to Mr. Paine belongs in part the honor shared by many of helping to strike the match which kindled the fires of the Revolution. But he no more merits all that honor than Joseph Warren or Crispus Attucks. The Continent was heaving and the eruption was sure to come. Mr. Paine simply helped to break the thin crust, and precipitate the outbreak of the long-pent fires of the volcano.

PAINE AND LOUIS XVI.

Mr. Ingersoll’s statement respecting Mr. Paine’s part in the assembly of the French Republic, deserves a passing word. His statement is, that “Thomas Paine had the courage, the goodness, the justice, to vote against the death of Louis XVI., when all were demanding the death of the king,” and hence when “so to vote was to vote against his own life.” This would make it appear that Mr. Paine stood almost, if not quite, alone in that assembly; took upon himself even the peril of martyrdom for his clemency. But read Lamartine’s history of the Girondists, and see how differently a Frenchman loving democracy, and hating kingship as ardently as Mr. Paine, puts the matter. M. Lamartine says, Mr. Paine having received from the king 6,000,000 francs for his country, had “neither the memory nor the dignity befitting his station,” but by his paper read before the convention, “ignoble in its language as cruel in its intentions,” heaped a long series of insults upon a man whose generous assistance he had formerly solicited, and to whom he owed the preservation of his own country.” And when the question of the death of the king was at last, after a full month of debate, brought to a vote—there were 721 voices uttered from the tribune. Of these 387 were for death, and 334 for exile or imprisonment. So that, whatever the “courage, the goodness, the justice, the sublimity of devotion to principle, the peril of life,” involved in Mr. Paine’s vote, he had 333 sharers of his heroism and his glory. 9

CHARACTER OF CHRIST.

But to come now to the purpose in hand and consider his arraignment of Christianity? It is possible to apply this test-principle of the text, so that we may know to a certainty what the relative claims of the two systems asking our acceptance are. For they have both been long enough before the world to produce ample results, results whose quality is ascertainable beyond all doubt. Let us take first, then, the character of the founder of Christianity, and test that, and then the character of the teachers of infidelity and test them. We shall be sure to be on the right track in such inquiry. For while it does not greatly matter what the character of a man may be who gives us a new theory of electricity, or light, or sewerage—his discovery being of equal value whether he be honest or dishonest, temperate or intemperate, moral or immoral—it does matter what the personal character of a teacher of a new scheme of morals is. He comes claiming our acceptance of certain doctrines which, he says, are vital to our welfare. He declares that only as we accept his dogmas can we lead lives of highest happiness and usefulness. That everything, in short, that can be called good, is bound up in his teachings. Naturally, therefore, and of right, we look to him for an illustration of what he teaches. If he wants us to be truthful, honest, moral, he must be. The moment we fail to find in the teacher the exemplification of the thing taught, that moment the power of his teaching is broken. I am speaking, of course, of one who has a system which he claims to be superior to others, and which he insists that men must receive or suffer great loss. It is only folly for a known deceiver to try to enforce truthfulness, for a known thief to teach honesty, or a libertine virtue. We say instinctively and scornfully to such—“Physician, heal thyself.”

We have hence the best of rights to test this great teacher of Christianity, and to test him rigidly. We have the right to put his life to proof everywhere, and see whether it show a quality accordant with his speech. For he claims for his teaching not only supreme authority, but the authority of truth that does not rest content till it has taken possession of a man in the very roots of his being, penetrated him through and through, and made him so entirely a lover of truth that he will tolerate no fellowship with anything else. More than this, his standards of morals deal not so much with words, and deeds, as with their underlying motives. With him covetousness, is not so much looking upon the things of others with the eyes of the body, as with the eyes of the soul. To lust after a woman is as truly adultery, as the open violation of the seventh commandment. It is murder, as truly, to have the thoughts dabbled in blood as the hands.

Furthermore, they who accept this teacher’s doctrine must stand ready to surrender everything on the call of their master; to leave home and its treasures; to take oppositions, persecutions, sufferings, death even, and to do this without murmuring. And only they, who covet to have their wills merged in their teacher’s, who carry in their souls the ideal of a perfection as high as God, and who consciously and absorbingly desire and seek the good of men,–can be counted true disciples.

Here now is opportunity indeed for tests. And this founder of the new scheme, which he insists on having men receive, must demonstrate in himself the spirit of his own doctrines, must illustrate unequivocally their fruits, or be rejected. What, now are the facts? Why, clearly this, that he stands there on the track of history the exact embodiment of every truth he uttered. The keenest and most relentless criticism has had his life as in the focus of its blazing examination for centuries, has searched that life back and forth through every phase of it, from his childhood to the last agony on the cross, and yet is compelled to confess that nowhere is there a day or an hour, a deed or a word or a thought, that does not exactly mirror the teachings of his lips.

More than that, he stands there, the one only character of all the ages absolutely without a spot or blemish, and this, as I have said, not as the verdict of partial admirers, but of those who would, many of them, be only too glad to prove him a hypocrite or a cheat.

WITNESS OF INFIDELS.

Theodore Parker, and he is no enthusiastic devotee of Christianity, is compelled to say of him, that “he unites in himself the sublimest precepts, and divinest practices; that he rises free from all the prejudices of his age, nation or sect, pours out a doctrine beautiful as the light, sublime as heaven, true as God.” 10

Mr. Chubb, a noted English infidel, admits in his “True Gospel,” “that we hae in Christ an example of one who was just, honest, upright, sincere, who did no wrong, no injury, to any man, and whose mouth was no guile.” 11

Rousseau says: “What sweetness, what purity, in his manner; what sublimity in his maxims! What profoundness in his discourses! Where is the man, where the philosopher, who could so love, and so die, without weakness and without ostentation!

If the life and death of Socrates were those of a sage, the life and death of Jesus Christ were those of a God.” 12

And Thomas Paine himself is careful to testify in his Age of Reason, that “nothing that is here said,” in his holding up of Christianity to ridicule, “can apply, even with the most distant disrespect, to the real character of Jesus Christ. He was a virtuous and an amiable man. The morality that he preached and practiced was of the most benevolent kind.” 13

Such confessions as these from the lips of infidels are most amazing. They demonstrate that Jesus Christ made good his astounding pretensions, that he was literally without sin, and had the best of rights to call himself “the light of the world.” But the significance of these confessions goes beyond than this. For this stainless, perfect character is an absolute impossibility if the claims of infidelity are true.

CHRIST REPRESENTS CHRISTIANITY.

Where shall we look for the exemplification of a system of morals but to its founder? We look to Brigham Young, as the prophet and head of Mormonism, and we find exactly what we should expect from the teachings of that faith: a polygamist, and a despiser of all doctrines outside of the book of Mormon.

We look to Mohammed, and find him exactly what we should expect from the Koran, a man who believes in sensuality and in bloodshed to secure his ends.

So in the gods of the Romans, and Greeks, and Hindoos, and Egyptians, we find exactly such gods as we should look for from the religions to which they belong—gods stamped with deceit, cruelty, blood-thirstiness, lust.

So it should be here. If Christianity is what Mr. Ingersoll declares it to be, unloving, tyrannous, bloody, delighting in nothing so much as deceits and woes, then Jesus Christ should be of a piece with it. Nay, in him all these foul things should be headed up. The stream can not rise higher nor be purer than its source. If lying, and rapine, and lust, and violence are the law or the practice, then infallibly sure re we that some Henry VIII., or Philip II., or Caesar Borgia, or Nero, either makes the laws, or wields the scepter. If Christianity is a bundle of lies, a code of cruelty, then he that originated it stands proved either the prince of impostors or the worst of fiends. Whereas, upon the testimony of infidels themselves, he is the one in whose speech and life there is more of purity, goodness, heaven, than in any other character the world has ever seen. He is, in short, the one confessed God-man of all history.

Mr. John Stuart Mill, who is an avowed atheist, and, of course, denies the divine character and authority of Christianity, declares “that” it is of no use to say that Christ as exhibited in the gospels, is “not historical.” And he asks, “Who among his disciples, or among their proselytes, was capable of inventing the sayings ascribed to Jesus, or of imagining the life and character revealed in the gospels? Certainly not the fishermen of Galilee: still less the early Christian writers.” 14 And Mr. Lecky, who agrees with Mr. Mill in rejecting the divineness of Christianity, agrees also with him in conceding the historical claims of both Christ and his reputed doctrines. His language is, “It was reserved for Christianity to present to the world an ideal character, which through all the changes of eighteen centuries has filled the hearts of men with an impassioned love, and has shown itself capable of acting on all ages, nations, temperaments, conditions; has not only been the highest pattern of virtue, but the highest incentive to its practice. . . Amid all the sins and failings, amid all the priestcraft, the persecution and fanaticism which has defaced the church, it has preserved in the character and example of its founder an enduring principle of regeneration.” 15

Such language from such men is decisive. It demonstrates that Christ and Christianity stand or fall together. That they are as inseparable as a stream and its fountain; as essentially one in character as the light and the sun.

THE CHARACTER AND TEACHINGS OF INFIDELS.

But what now has infidelity to set over against all this? If it is, as is claimed by Mr. Ingersoll, the sublime and blessed truth which is to banish all evil, and fill the world with purity and heaven, it will have, of course, some grand examples of its superiority to show. There must needs be some among the apostles of this highest and divinest form of truth, before whom the founder of this Christian scheme of lies, cruelty, blood, will pale, as the stars before the sun. Who, then, are these grand luminaries who are to light our way to this millennium of freedom, purity, peace? There is no lack of apostles. Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Hume, Hobbes, Lord Herbert, Bolingbroke, Gibbon, Paine,–these are representative names, the highest and best that infidelity has to offer. Gibbon is one of the fairest as he is one of the ablest of them all; and he has given us a biographical account of himself, wherein, amid all the polish and splendor of the rhetoric of which he is such a master, “there is not a line or a word that suggests reverence for God; not a word of regard for the welfare of the human race. Nothing but the most heartless, sordid selfishness, vain-glory, desire for admiration, adulation of the great and wealthy, contempt for the poor, and supreme devotedness to his own gratification.” 16

Adam Smith calls Hume a “model man,” a man “as nearly perfect as the nature of human frailty will permit.” But David Hume maintained that our own pleasure or advantage is the test of what is moral; that “the lack of honesty is of a piece with the lack of strength of body”; that “suicide is lawful and commendable”; that female infidelity when known is a small thing, when unknown, nothing”; that “adultery must be practiced, if men would obtain all the advantages of this life; that if generally practiced, it would, in time, cease to e scandalous, and if practiced frequently and secretly would come to be thought no rime at all.” 17

Lord Herbert taught that the indulgence of lust and anger is no more to be blamed than thirst or drowsiness.” 18

Mr. Hobbes declared that civil law is the only foundation of right and wrong; that where there is no law, every man’s judgment is the only standard of morals; that every man has a right to all things, and may lawfully get them, if he can.” 19

Lord Bolingbroke held that self-love is the only standard of morality; that “the lust of power, avarice, sensuality, may be lawfully gratified if they can be safely gratified; that modesty is inspired by mere prejudice, polygamy is a law of nature, adultery no violation of morals, and that the chief end of man is to gratify the appetites of the flesh.’ 20 And he kept faith with his teachings, and led the life of a shameless libertine.

Voltaire advocated the unlimited gratification of the sensual appetites, and was a sensualist of the grossest type. He was likewise a blasphemer, a calumniator, a liar and a hypocrite; a man who all his life taught and wrought “all uncleanness with greediness,” and nevertheless had the amazing good sense to wish that he had never been born. 21

Rousseau was, by his own confessions, a habitual liar, and thief, and debauchee: a man so utterly vile that he took advantage of the hospitality of friends, to plot their domestic ruin a man so destitute of natural affection that he committed his base-born children to the charity of the public that he might be pared the trouble and cost of caring for them. To use his own language, “Guilty without remorse, he soon became so without measure.” 22

As to Thomas Paine, the verdict of history is too well settled to be reversed by Mr. Ingersoll’s wit, or ridicule, or denials. After all allowance that can be made for misrepresentation, this remains unquestionably true, on the authority of those who claimed to be his friends and knew him best, that in his last years he was addicted to intemperance, given to violence and abusiveness, had disreputable associates, lived with a woman who was not his wife, and left to her whatever remnant of fortune he had.

THE CONTRAST.

These, now, are the representative names of infidelity, the most saintly apostles it has to offer: men, the very best of whom are characterized either by vanity, or selfishness, or pride, or envy; while some are given to deceit, blasphemy, drunkenness, sensuality. Yet these are held up as the examples and illustrators of this new and better gospel that is to banish from the world the “dogmas of ignorance, prejudice and powe,” “the poisoned fables of superstition,” and in their stead guarantee to us “freedom, truth, goodness, heaven.” What say you friends? Here they are—the representatives of Christianity, the advocates of the ignorance, bigotry, despotism, which is declared to so blight this world,–Wesley, Whitefield, Luther, Calvin, Anselm, Augustine, John, Paul, Jesus Christ; and here over against them, are the representatives of infidelity, the advocates of the doctrines that are to bring back to the world the lost Paradise,–Bolingbroke, Hobbes, Hume, Voltaire, Rousseau, Thomas Paine. With which shall we make surest of truth, virtue, happiness? With which will our wives and little one be in the safest keeping? With which the purity of the community, the security of the State, the glory of the nation be most surely guarantied? Such questions answer themselves. No amount of sophistry with even Mr. Ingersoll’s brilliant rhetoric to help it, could make us mistake the night for the day. But as well attempt that as try to make us put infidelity in the place of Christianity as the light and hope of the world.

THE FRUITS OF CHRISTIANITY.

But let us advance the thought, and ask what are the fruits of the teaching of Christ as contrasted with those of the apostles of infidelity. In looking for these fruits, this remarkable fact appears, that Christ stands everywhere as the ideal character which those who accept his doctrine are pledged to realize so far as lies within their power. This is a peculiarity of Christianity. To study Aristotle, or Plato, or Bacon, and accept what they teach, implies nothing of this. I may receive all they have to offer, and yet come into no sort of personal relations to either of them. I may accept such teachings as truth and yet know nothing about their personal character. But not so as to Christ. I cannot take what he says about God and sin, or obedience, or prayer, and set about carrying out such truths, realizing the ends for which they were set forth, and yet sustain no personal relations to him, have no desire to become like him. That is an impossibility. He and his Word are indissolubly wedded, are inseparably one. To hear that Word, from whosesoever lips, is the same as hearing him; to receive it, is to receive him, and to reject it is to reject him. The only possible way of accepting his truth, is to accept him. The whole object of his teaching may be summed up in the simple idea of bringing men to be like him; not to have the spirit of Christ is to be none of his. Not to covet to be conformed to his image, not to set that clearly before the mind as a constant aim of life, is to be proved not a true disciple. This is a fundamental principle or law of Christianity.

Hence, the power of Christianity as it relates to men’s lives. In the nature of the case, in just so far as it gets control of men’s hearts, it must produce disciples stamped by the spirit of its founder. They who receive the truth of Christ will inevitably reveal the likeness of Christ. Paul’s eager coveting, whereby he “counted all things but loss that he might win Christ and be found in him,” and his constant exhortations to believers to “put on Christ,” to be “conformed to him,” are the spirit which all true disciples feel. In other words, Jesus Christ is the one, universal model held steadily before the hearts of all who receive his truth. And there results just what we should expect,–a spiritual transformation wrought in every heart, whereby it takes on more and more of the likeness of Christ. Take Peter, for example,–a rough, hard, very likely profane fisherman, vehement and impetuous to the point of rashness, and yet cowardly even to falsehood and blasphemy, to escape being reckoned a friend of his manacled Master.

But when this gospel of Christ has gotten thorough possession of him, and the power of it comes to be felt, this same man is all inflamed with zeal; reveals a courage that does not flinch before thousands of his spiteful countrymen; takes up a life full of ridicule, insults, scourges, prisons; and goes steadily on to the sure death that waits, only eager to be more and more like him, the unseen, yet inspiring Lord, in whom his faith is anchored. So Paul, a scholar, but full of the scholar’s scorn of the friend of publicans; a Pharisee of the straitest sect, and hence stirred with intensest hate toward all who forsook the faith of their fathers; so aflame with wrath that he stooped to fill, the place of an executioner, and breathing forth threatenings and slaughter went out even as some fierce inquisitor of Torquemada, glad to redden his hands in the blood of men, women, and children, holding the despised gospel.

But this gospel by and by gets hold of him, and what a change! The lion becomes the lamb; the hate, ferocity, bloodthirstiness is not only all gone, but a baptism of heavenly gentleness and love has come instead. He casts aside all his high opportunities, burns his back on the sure prospects of affluence and renown, and taking to his heart the very doctrines he despised, puts himself on the level of the publicans and harlots who have received the new truth, and goes forth to face an experience that for thirty-five years is one perpetual succession of indignities, and sufferings, which it is next to impossible to conceive. And he does it with a sublime patience, nay, rejoices in his tribulations, and glories in his infirmities, because he thereby realizes more fellowship with the Christ of his hope, more power to commend him unto men.

So always. The spirit which animated Pater and Paul animates all his disciples. It is the spirit of Christ, his pity for men, his love, his desire to do them good, his longing to clear their hearts and lies of everything false, corrupt, mischievous, and thus ennoble and bless them, reproducing itself in all who receive his truth. Augustine, John Newton, John Bunyan, and thousands of others, rise up all through the centuries to witness what fruits of character transformation this gospel everywhere insures. No matter of what race, or clime, of what condition in life, of what temperament or idiosyncrasies or habits, the one fact that inevitably marks the reception of this scheme of Christianity is, that its disciples take on the image of their Lord and Master. And if it could only have its way, and men would everywhere receive it into good and honest hearts, make it the law of their choosing, loving, doing, it would fill the world with the likenesses of Jesus the Christ. And that I take it, would end all debate.

For our city, filled with men, women, children, all bearing his image, all filled and led of his spirit, all using his speech, repeating his life, would be what a city of love and purity and heavenliness! And the world so filled would be, how plainly, that old prophetic word come true—the wolf dwelling with the lamb, the leopard with the kid, the swords beaten into plough-shares, the spears into pruning hooks, the tears wiped from off all faces, sorrow and sighing forever fled away, the light of everlasting peace on all faces, the joy of everlasting blessedness in all hearts.

And when to this there is added all the mighty influence over men that comes from such conceptions of God as Christianity unfolds, and requires men to accept; conceptions of God, as infinitely good, and holy, and just, and suffering men to set up and to live by no standards but his own; conceptions, hence, which send men out to daily duty as under the conscious flash of omniscience, and in the conscious fellowship of perfect purity, unselfishness and love; conceptions, further, of God as administering a moral government, pledged, with omnipotence behind it, to secure the triumph of holiness and the retribution of sin, sin of act, or speech, or thought; when, I repeat, all these considerations are brought to bear upon men’s hearts and lives as constant forces, as by the scheme of Christianity they are, who can doubt what the quality of their fruitage in human conduct will be. As well might we doubt whether the sun will scatter darkness where it shines, or evoke life and beauty from the seeds embosomed by its warmth.

But what has infidelity to set over against these forces? What are the potent influences by which it is to surpass in efficiency for good, the example and teaching of Christ, and his apostles, the law of God and its standards, and thus renovate society and clear the earth of evil, and fill it with blessing? Why, that there is no absolute standard of morals, that every man is to be his own judge of what is right, and seek what will minister to his happiness or profit. That we may gratify our appetites at pleasure. That modesty is a mere prejudice. That to secure the highest good, we must lie and steal, and practice adultery! That there is, probably, no God, and if there be, he is above taking cognizance of the petty matters of this life. That there is no hereafter, or if there be, there is no punishment for sin. That God, if there be a God, wants men to despise all creeds, all teachings, all authorities that cross their preferences, give themselves to seeking happiness, and with utter contempt of pulpits and preachers of hell-fire, live while they lie, and let the future take care of itself.

These are the two systems which are the claimants for our acceptance. Which shall we take for the vine, and which the thornbush; Which is the sheep, and which the wolf? Looking at the two classes of teachers as now put in contrast, and the spirit and tendency of their teachings, can there be any difficulty in making answer? As little as between a royal palm on the one hand, its branches filled with singing birds, groups of parents and children gathered underneath rejoicing in the grateful shade, the bubbling fountains, the fragrant flowers, and the luscious fruit; and on the other a baleful upas-tree, not a bird in its branches, nor a fountain, nor a flower, nor a living thing beneath, but far and near the bones of its victims thickly strewn, and the poison of death tainting all the air.

And just as little doubt can there be, when we apply this same test of the text to the ages, and ask for the fruits of these respective systems of belief. I commend the inquiry to you to examine it at your leisure.

CHRISTIANITY NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ITS DISCIPLES’ ERRORS.

Mr. Ingersoll prefers fearful charges against Christianity. Wherever he finds a witch hung, a philosopher put into prison, or an unbeliever put to death by those who wear the Christian name, there he raises the cry of tyranny and bloodthirstiness, and accuses Christianity of pulling the rope, turning the key, kindling the fire. I have no defense to make for such things. They are sad facts in church history, and I condemn them as earnestly as does Mr. Ingersoll.

But, admitting all such facts that can be hunted out in the sweep of eighteen centuries, the genius of the gospel, the spirit of Christianity, is in no respect proved to be cruel and tyrannous thereby. As well say that Peter’s lifting his sword and smiting off the ear of the high-priest’s servant, or the desire of James and John to call down fire from heaven on the unfriendly Samaritans, was the spirit of Christ and his gospel.

These things are not the product of Christianity. They are in no sense the legitimate fruit of its teachings, and in no sense do they truly represent its spirit. They are the product of human nature sometimes falsely interpreting, sometimes boldly overriding, the Word of God.

Good men may be led astray, may be blinded, hurried on by passion, and do things which in cooler blood and under better light they would be the first to condemn. Christianity has never taught, has never approved, such things. The Roman-Catholic Church may have done so, and John Calvin, and Cotton Mather, but the Bible never. And while we condemn the misdirected zeal of these good men, we ought not to forget, as Mr. Ingersoll is at pains to, the extenuations to which they are justly entitled; the fact, for example , that the highest authority in English law, Sir Matthew Hale, held Cotton Mather’s view about witches, and sentenced them to death: and the fact, also, that the sentence of Servetus was not the act of John Calvin, but of the Swiss magistrates, and their decision to burn him adhered to in spite of Calvin’s earnest appeal that he should be otherwise executed. Nor, making the most and worst of such mistakes, or cruelties, if any choose to term them so, ought we to be blinded thereby to the splendid services in behalf of truth, justice, liberty, rendered by these very men. There are spots even on the sun, but we forget about them in the wealth and blessings of its life-giving effulgence.

But whatever may be true of the conduct of particular disciples of Christianity, they never constitute the standards by which its teachings are to be tested. Such conduct throws us back upon the question, is this what the Bible teaches? That is our statute-book, and its express doctrines, not men’s interpretations of them, are what settles its spirit. If good men anywhere in our State, angered by the depredations of a gang of horse-thieves or burglars, organize into a vigilance committee, lay hands upon a suspected person, take him from bed or from prison, and hang him to a limb of the nearest tree, we do not arraign the laws of Illinois, nor the people of Illinois, for the act. We charge the violence, the lawlessness, upon the particular wrong-doers engaged.

So here. The Bible nowhere teaches cruelty or tyranny; nowhere encourages putting men to death because of their beliefs, or even their shamelessness in sin. God did, indeed, in given instances, take the administration of human government into his own hands, and sweep the face of the earth clean of its vile inhabitants by the deluge, and blot out Sodom and Gomorrah, and the cities of the plain with a fiery storm of retributive wrath. So he likewise gave orders for the purging of the land of promise of the hordes of Canaanitish idolaters whose cup of abominations was overfull. And for these things God stands ready to make answer to all who arraign him.

THE SPIRIT OF CHRISTIANITY ILLUSTRATED.

But he has laid on men no injunctions requiring them to take his place and pas upon their fellows in judgment. Throughout his book one spirit runs. On the authority of the one great expounder of it, the sum of all its commands is supreme love for God, unselfish love for man. And this is the spirit which Christianity has always taught and always exemplified in its true disciples. Look at the proof before us to-day. Consider these thousands of churches, their pulpits all aiming to exalt this Bible with its law of love, to magnify this Christ with his life of devotion to the welfare of men. And this is the spirit which Christianity has always taught and always exemplified in its true disciples. Look at the proof before us to-day. Consider these thousands of churches, their pulpits all aiming to exalt this Bible with its law of love, to magnify this Christ with his life of devotion to the welfare of men. Consider the millions of worshipers, all seeking to know God, all accepting his standards of character, all seeking to possess the spirit and wear the likeness of his Son. Consider the countless multitudes of children in Sunday-schools, filling the air with the praises of Jesus Christ, and all taught, if nothing else, that he is the one model they are to imitate, and his teachings to be the law of their deeds, their words, their thoughts. Consider these innumerable Christian newspapers filling the land with the same doctrines and using their prodigious influence to make them the supreme faith of the nations. Consider the hundreds of Christian colleges and Seminaries training young men and young women for lives of beneficence and usefulness. Consider the scores and hundreds of publishing societies all animated with one purpose and sending forth their mighty streams of tracts, books, Bibles, to fill the earth with the story of Christ and with the spirit of his life. Consider the countless institutions established by Christianity to relieve distress, to provide for the unfortunate, to administer the gospel of practical beneficence. Consider the manifold organizations aimed at spreading the gospel among all the debased races of the earth; at making the victims of superstition with its nameless terrors know the glad tidings of a salvation that puts an end to bloodshed, cruelties and woes, fills all hearts with love, all homes with peace, all lives with blessing. Consider how this spirit of Christianity illustrated in all these diverse lines of effort, everywhere carries on its banner the doctrine of the universal brotherhood of man, recognizes no distinction between the negro, the Indian, the Chinaman, the Hottentot, the cannibal, but seeks to make them all one in the fellowship and liberty of Jesus Christ. And consider yet again, that it requires, as one of its fundamental principles, as a condition in fact of all true discipleship, that all who receive its truths shall pledge themselves, to give, and pray, and toil without ceasing, till this gospel has penetrated every jungle, climbed every mountain fastness hunted out every cavern, every kraal, every wigwam, every snow hut, and sounded its invitations and promises in the ears of all mankind.

Whether all this signifies anything as a power for good in the world, judge ye. Mr. Ingersoll seems to think it goes for nothing. But against his opinion I put that of Mr. Lecky, who in his history of European morals, speaking of the contrast between the influence of Christianity and paganism, says, “It was reserved for Christianity to present to the world an ideal character which through all the changes of eighteen centuries has been not only the highest pattern of virtue, but the strongest incentive to its practice, and has exercised so deep an influence that it may be truly said to have done more to regenerate and to soften mankind than all the disquisitions of philosophers and all the exhortations of moralists.” 23

THE SPIRIT OF INFIDELITY ILLUSTRATED.

But when was ever infidelity so engaged? Where are the organizations it has instituted, the missionaries it has sent forth, to fill the world with the blessings of faith, freedom, virtue? But I forget. Infidelity has such a record of organized endeavor to regenerate mankind. Turn to the history of the French Revolution and read it there. The leaders of that revolution, as you know, were the very class whom Mr. Ingersoll glorifies: the disciples of Diderot, Voltaire, Rousseau. They were avowed atheists or infidels, and Thomas Paine was one of the number, sat in their midst, participated in their discussions, aided in drawing up the constitution they enacted. What that convention said and did, the world knows, and will never forget.

They did what Mr. Ingersoll would be glad to have the Congress of the United States do. They abolished Christianity by vote. They declared there was no God, and forbade the public instructors to utter his name to the children. They struck the Sabbath out of the calendar and made the week consist of ten days instead of seven. They wrote over the gates of the cemeteries, “Death is an eternal sleep.” They tore down the bells from the church spires and cast them into cannon. They stripped the churches of everything used in worship, and made bonfires in the streets, and then instituted the rights of the old pagan religions where the altars had stood. Not content with this, Chaumette, one of the leaders of the convention, appeared one day before that body, leading a noted courtesan with a troop of her associates. Advancing to the president, he raised her vail, and exclaimed:

“Mortals! Recognize no other divinity than Reason, of which I present to you the loveliest and purest Personification.”

Whereupon the president and the members of the convention bowed and professed to render devout adoration. And a few days later the same scene was re-enacted in the cathedral of Notre Dame, with increased profanations and more outrageous orgies, and was declared to be the public inauguration of the new religion of the commune. And like desecrations and blasphemies throughout all France took the place of the old worship.

Worse than this, all distinctions of right and wrong were confounded. The grossest debauchery was inaugurated, the wildest excesses prevailed and were gloried in. Contempt for religion and for decency became the test of attachment to the government. The grosser the infractions of morals, the greater the so-called victory over prejudice, the higher the proof of loyalty to the State. To accuse one’s father was the best proof of citizenship; to neglect it was denounced as a crime, and was punishable with death. Wives were bayoneted for the faith of their husbands, and husbands for that of their wives.

One of the chief tools of the commune, Carrier, ruling at Nantes, declared that the “intention of the Convention was to depopulate and burn the country,” and he was as good as his word.

He gathered those suspected of disloyalty in flocks. He shut up 1500 women and children in one prison without beds, without straw, without fire or covering, kept them for two days without food, and then caused them to be shot. The only escape was, for men to surrender their fortunes, for women their virtue.

He contrived ships with slides in their hulls below the waterline, loaded these with his prisoners under pretext of transporting them elsewhere, and when the vessels were in the middle of the Loire, ordered the valves opened and the victims plunged into the water, while he, surrounded by a troop of prostitutes looked on and gloated over the scene.

And this is only a type of what occurred elsewhere. Proscription followed proscription, tragedy followed tragedy, till the whole country was one huge field of rapine and of blood. 24

Mr. Ingersoll admits that 17,000 perished in the city of Paris during this combined reign of infidelity and terror; but he forgets to add that throughout France not less than 3,000,000 lives were the costly price of establishing the new religion.

There is no disputing these facts, nor the reasons that under-lay them. This whole terrific record—and history knows none that is darker or more damning—was the direct and legitim ate fruit of the doctrines which Mr. Ingersoll lauds as the sublime truth “that is to fill the world with peace.”!

The men who originated and carried out this combined scheme of government and religion, were the men with whom Thomas Paine sat, and voted, and was in every way identified. His faith was their faith. And at his door equally with theirs does this series of the most fiendish outrages that ever disgraced a people pretending to be civilized, cry for vengeance.

INFIDELITY WOULD REPEAT ITS RECORD.

What infidelity was then, it is now. What it did then, so far as its assaults upon religion were concerned, and its overturning of civil order, it would do to-day, if it had the power.

If Mr. Ingersoll could have his way, he would abolish God, and the church, and the Christian Sabbath, and the Bible, and everything pertaining thereto. He would banish Christian newspapers and colleges, and benevolent societies; proscribe all oaths in courts of justice; expunge the name of God from all statute books, the name of Christ from all calendars and text books; annihilate all moral standards; would, in a word, not only quench all prayer, and praise, and honoring of God, but sweep the world clear of everything that bears the name, or shows the spirit of Christianity.

And what would he give us for all this? For our Bible, the Age of Reason. For the Sabbath, the beer garden and the theater. For worship, the rites of paganism or the adoration of an apotheosized courtesan. For the standards of God’s law, that which should seem right in every man’s eyes. For the law-making power, the blasphemous horde of the French commune. For security, the guillotine dripping with blood at every street-corner. For truth, candor, love, temperance, purity—deceit, treachery, hate, drunkenness, sensuality, with all their crimes and shames. In a word, for this is the outcome of all such teaching, if the infidelity that Mr. Ingersoll glorifies could have its way, it would strike the sun from the sky of our Christian civilization, and give us instead the lurid night of the reign of terror, only it would make it a night with no Napoleon or Chateaubriand to break the gloom—a night of tears, and blood, and woe without an end!

Shall we open our arms to welcome this new gospel? Are we eager to substitute vultures for doves, wolves for sheep? During this frightful period of French history alluded to, one of the five Directors in whose hands the government was lodged, asked Tallyrand what he thought of Theophilanthropism, the name given to the religion. “I have but a single observation to make,” was his reply. “Jesus Christ, to found his religion, suffered himself to be crucified, and he rose again. You should try and do as much.” 25

Friends, when this new gospel of infidelity shall furnish us such proofs of its right to claim our acceptance, it will be entitled to a hearing. Until then, let us cling to the teachings of him whose words and deeds alike attest him the Light and the Life of the world.

MR. INGERSOLL’S ATTITUDE TOWARD THE BIBLE.

BY PROF. S. I. CURTISS, OF THE CHICAGO THEOLOG. CAL SEMINARY.

Mr. Ingersoll, in his lecture on the Mistakes of Moses, and elsewhere, denies the Divine origin and authority of the Bible, although not in so many words, substantially for the following reasons:

1. Because of its false science.

2. By reason of its unhistorical character.

3. On account of its immoral tendency.

4. On the ground of its barbarism and cruelty.

Before examining these charges, which are involved in some of his lectures, in detail, let us inquire whether Mr. Ingersoll is prepared to treat the question with candor. Probably no living orator has greater power with the masses, but it must be remembered that eloquence is not always enlisted on the side of truth and soberness, and that facility in making telling points and bringing down the house, is perhaps unfavorable to patient research and careful statement.

There is abundant evidence of the following facts which ought to unfit him in the mind of every intelligent person for being a leader of public opinion:

1. He indulges in the grossest errors and misstatements. 26

NO BLADE OF GRASS IN THE DESERT OF SINAI.

In his Mistakes of Moses he affirms that there was “no blade of grass” in the Desert of Sinai, and that Sahara, compared to it, is a garden. This assertion, however, is utterly false, since “at the present time, under the most unfavorable conditions, it affords some facilities for pasturage and gardening.” 27

THE HOLY LAND A FRIGHFUL COUNTRY.

He speaks of the Holy Land as a frightful country, covered with rocks and desolation, and says that there never was a land agent in the city of Chicago, that would not have blushed with shame to have described that land as flowing with milk and honey, and this in spite of the fact that Tacitus, Josephus, and other writers, both ancient and modern, mention its fertility. 28

THE JEWS NEVER AGREED AS TO WHAT BOOKS OF THE BIBLE WERE INSPIRED.

In speaking of the Bible he declares that “the Jews themselves never agreed as to what books were inspired,” although Josephus boasts that the Jews have a definite number of books in the Old Testament, and the Talmud asserts that the man who reads apochryphal books forfeits eternal life. 29

OUR INDEBTEDNESS TO MURDERERS FOR OUR BIBLES AND CREEDS.

One of his strangest assertions is that we are indebted to murderers for our Bibles and Creeds. He mentions Constantine, Henry VIII., and Elizabeth, in confirmation of this statement. The remark, however, is due to an utter perversion and misrepresentation of history. 30

NO CONTEMPORANEOUS LITERATURE.

He moreover affirms that there was no contemporaneous literature when the Bible was composed. He evidently knows nothing of the papyrus rolls which date back even earlier than the time of Moses. 31

But such erroneous statements are not the only things which should make us distrustful of Mr. Ingersoll’s method for

2. He manifests a deadly enmity against the Bible.

HIS SPECIAL PLEAS AGAINST THE BIBLE AND CHRISTIANITY. 32

This is evident from his uniform treatment of the Scriptures. He is so mad against them, that they do not even appeal to him as containing some of the finest compositions from a purely literary standpoint. Nor does he seek to ascertain the doctrines of Scripture from a critical point of view. He looks only for blemishes, hence he is incapable of treating the subject fairly. His lectures are special pleas against the Bible and Christianity. His methods are worthy of those famous attorneys described by Mr. Dickens, in the Pickwick papers.

But some one may say, admitting all that, does it substantially change the aspects of the question? Has not Mr. Ingersoll after all, given utterance to objections which are none the less unanswerable, although presented by him?

Let us now turn to some of the reasons on account of which Mr. Ingersoll denies the Divine origin and authority of the Bible. He does so substantially, on account of the following assumptions. 33

I. Because of its false science.

THE BIBLE NOT A SCIENTIFIC BOOK.

It must be evident to any one on a little reflection, that the Bible is not a scientific book, nor could it be such. Scientific language would have been misunderstood by the mass of men, and would have seemed false to every age except the one which shall arrive at certainty. Moreover, only so much was revealed in regard to creation as was necessary to imprint the truth upon the minds of men that God made the universe. The Bible is just as unscientific as the best scientists are, when they speak of the sun as rising and setting, and it is no more an impeachment of the Divine wisdom, that we find phenomenal language in the Scriptures, than such expressions are of the knowledge of the astronomer respecting the true relation of the planets.

Now when we remember that it was not in God’s plan to reveal how the world was made, but rather that he created it, and that this revelation was not given through scientific men, nor for them, it still remains to be proved that there is any real contradiction between the artless account in Genesis, and what shall finally appear to be the true science in regard to the origin of the world.

THE BIBLE NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR MISINTERPRETATIONS.

The Bible is not responsible for the misinterpretations which have been placed upon its statements from the standpoint of false science. There is not a difficulty, not even that of the sun’s standing still, which may not be explained, when we remember that much of the language of the Old Testament relating to nature is phenomenal. How, then, could the author of the Book of Joshua have accounted for what seemed to him to be the lengthening of the day in any other way than by saying: “So the sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down about a whole day.” We must remember that the Old Testament, while it contains much valuable instruction for us, especially in the light of the New, was immediately designed for those who knew nothing of the true nature of astronomy, and who could never have understood this great deliverance if it had been described in scientific terminology.

THE HARE.

So the prohibition regarding the hare, because it chews the cud (Lev. Xi: 6,) was designed for practical use. It would have been absurd for the lawgiver to have added a note in regard to the true-state of the case, so as to prevent the cavils of critics in the nineteenth century. The hare fell under the class of unclean animals. One of his peculiarities was that he seemed to chew the cud. Moses therefore describes him in such a way as that he would be recognized by every one, while a zoological description of the animal would have entirely befogged the minds of the Israelite4s for whom the statute was solely intended.

ISRAELITISH SKEPTICS.

The Old Testament was subject to the criticism of the skeptics (Prov. xiv: 6; xix: 25,) of Solomon’s time, who would just as certainly have deemed scientific statements as unreasonable and inaccurate; as modern critics do the simple, phenomenal language, which for conveying religious truth is alone adapted to the infancy of the race as well as to its prime.

DIVINE WISDOM IN THE UNSCIENTIFIC CHARACTER OF THE BIBLE.

Instead, therefore, of finding in the unscientific character of the Bible a reason for distrusting its Divine origin and authority, we find therein the proof of God’s wisdom, since he has thus made those parts of Scripture intelligible to the mass of mankind, and has impressed the great lesson which he designed to teach, that he was the Creator of the universe.

Some, however, who may be inclined to admit this point, may say: Has not Mr. Ingersoll greater reason for rejecting the Bible?

II. Because of its unhistorical character.

MYTHICAL ELEMENTS.

This assumption is based on two grounds. It is affirmed that the accounts of every nation are at first unhistorical. The first chapters of the older Grecian and Roman histories are mythical, hence for the same reason it follows, as Mr. Ingersoll thinks, that the entire Pentateuch, so far as it claims to be historical, is really mythical. This view is confirmed in many minds by such incredible occurrences as the flood.

ATHEISTIC AND DEISTIC PRE-SUPPOSITIONS.

It must not be forgotten, however, that this view of the Scriptures proceeds either upon the deistic supposition that God has left the race to take care of itself, 34 or upon the atheistic delusion that there is no God. If we grant that God created the earth and man, and that he is a Holy Being, just such accounts as we have in Genesis are reasonable. Those which relate to the early history of the race before their dispersion are confirmed by traditions which have evidently been derived from the ancestral house.

LENORMANT ON THE DELUGE.

A famous French Semitic scholar 35 says, respecting the deluge: “The result then, of this long review, authorizes us to affirm the story of the Deluge to be a universal tradition among all branches of the human race, with one exception, however, of the black. Now a recollection thus precise and concordant, cannot be a myth voluntarily invented. * * * It must arise from the reminiscence of a real and terrible event, so powerfully impressing the imagination of the first ancestors of our race, as never to have been forgotten by their descendants.”

OBJECTIONS MAY BE SATISFACTORILY ANSWERED.

Indeed all the common objections to the historical character of the Old Testament, such as the wonderful increase of the Israelites in Egypt, the number of their first-born children, when the primal census was taken, their sustenance in the wilderness, and the gradual extinction of the Canaanitish nations, admit of explanations which are deemed by excellent scholars to be sufficient. 36

TESTIMONY FROM CONTEMPORARY SOURCES.

From the nature of the case, but little support could be expected from the scanty memorials of ancient nations for the historical accuracy of the Old Testament, and yet there are not wanting on ancient monuments, and in the excavated libraries of Assyria, testimonies not only to the faithfulness of the delineations, 37 but also confirmations of historical facts as related in the Bible.

Indeed it is difficult to see how any work of such antiquity could, on the whole, have greater corroboration from internal and external evidence, with reference to its historical character, than the Old Testament.

It is however too much to expect that such a bitter enemy of the Bible as Mr. Ingersoll, should admit the historical character of the Scriptures on such grounds as I have mentioned. Prejudice blinds his mind to every argument in their favor. He even rejects them.

III. On account of their immoral tendency.

The evidence which he adduces is, that the Bible teaches polygamy, and because of some of the statutes respecting captive maidens, as well as on account of certain pages which he characterizes as “too obscene, beastly, and vulgar to be read in the presence of men and women.”

POLYGAMY.

It is certain that the Bible does not teach polygamy. Proof of that has been produced elsewhere. 38 God is represented as creating man in a holy state. In that state he gave him but one wife, although the earth might have been peopled faster if he had furnished him with more. Lamech, a descendant of a murderer, and as is generally supposed, himself a murderer, was the inventor of polygamy. Pictures of domestic bliss are only connected in the Old Testament with monogamy, 39 while the bickering which are portrayed in the families of Abraham and Jacob are anything but a recommendation of polygamy.

CAPTIVE MAIDENS.

The law respecting captive maidens was, as has been shown in another place, 40 a merciful provision. It was far in advance of the barbarous practices characterizing every nation, which has not been permeated with a Christian civilization, where booty and beauty have fallen a prey to the brutal conqueror.

THE ALLEGED OBSCENITY OF THE BIBLE.

The Bible cannot, except under the eyes of prejudice, be called “obscene, beastly, and vulgar.” It contains laws which condemn certain practices, and which we would not read before a mixed company any more than we would certain legal statutes, or certain sections from medical books. Where it records lust as in the story of Lot’s daughters, Joseph’s temptation, David’s adultery, and in the warnings against her whose steps take hold on hell, there is no indelicacy of expression. Those whose imaginations gloat over certain paragraphs in our public prints, would find these narratives insufferably tame. There are many things which might offend public delicacy, which are profitable for private reading and admonition. It would be a happy thing if every youth could always remember such passages as Prov. ii: 10-20; v: 3-14; vi: 20-32; vii: 1-23.

Even Solomon’s Song cannot be reckoned as impure except by those to whom nothing is pure. Prof. Oort, who rejects a large portion of the Old Testament as mythical, is candid enough to say of it: “A people who loved such songs, celebrating an invincible love, passionate indeed, to the last degree, but perfectly innocent, such a people cannot have been a prey to moral corruption.”

THE PURITY OF THE BIBLE.

The Bible, considering the age in which it arose, the character of the people for which it was originally designed, and the delicate subjects of which it treats, is a singularly pure book. There are works in English literature which have won the highest commendation of refined scholars, whose pages are defiled with descriptions which would excite lustful imaginations in the purest minds. There is nothing of that kind in the Bible. Compared with the finest works which the bloom of Grecian philosophy produced, it is infinitely superior. While Plato contemplates an ideal state, from which conjugal affection is banished, 41 God sets the race in families, and according to his law there is no dissolution of the marriage tie except through death or infidelity. When we take the teaching of the Bible as a whole, we find that in its requirements of purity of thought (Matt. v. 28) and action, it is infinitely in advance of our statute law, and of the depraved standards of the natural heart, hence we conclude that the system of morals which it inculcates, must be of Divine origin.

There is only one other point which is to be answered here. Mr. Ingersoll rejects the Bible.

IV. On the alleged ground of its barbarism and cruelty.

SLAVERY.

He finds in it a justification of slavery which almost all now regard as a relic of barbarism. But he overlooks the condition of the people. God allowed slavery as a kind of necessity of ancient society, but under limitations which tended greatly to alleviate the condition of servants. I have already shown elsewhere 42 that the servants of Israelites were treated with immeasurably greater kindness than those of the Romans, who were subject to the most dreadful tortures. The Roman matron might stab the unprotected arms and bosom of her maid-servant with a long needle, which she kept for the purpose, as many times as she pleased, 43 but if the Jewish master knocked out one of his slave’s teeth he must grant him his freedom. (Ex. Xxi: 27.) While the Old Testament recognizes slavery in the statutes which it enacts for its alleviation, it is certain that the spirit of the New Testament is antagonistic to this institution.

CAPTIVES.

Much is said with reference to the cruelty manifested in the extinction of captives taken in war, but it is forgotten that the existence of these foreign elements in the Israelitish body politic, would have been a constant menace against its life, on account of the ancient custom of avenging the blood of relatives not to speak of the danger of Israelites being led into idolatry by the conquered races.

CONCLUSION.

Now when we carefully examine all such allegations against the Bible, which are now so prevalent, and mark the absence of sober argument, the malignant spirit with which they are urged we cannot but feel that we have to do with “the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that now worketh in the children of disobedience,” who can transform himself into an angel of light, and be erudite with the learned, or superficial and brilliant with the masses, and who speaks “great swelling words of vanity.

“For still our ancient foe,

“Doth seek to work his woe:

“His craft and power are great,

“And armed with cruel hate,

“On earth is not his equal.”

Endnotes

1. The Chicago Times, Friday, Jan. 30, 1880.

2. Bancroft’s History, Vol. VIII, p. 236. Paton’s Life of Franklin, Vol. II, pp. 21-22.

3. Bancroft. Vol. VIII, pp. 140, 236-242.

4. Ib. Vol.. VI, VII, VIII, generally.

5. Bancroft, Vol. VIII. Pp. 135, 136.

6. Ib. p. 136.

7. Ib. p. 143.

8. Ib. pp. 53, 54.

9. Lamartine’s Girondists, Bohn’s Ed., Vol. II. pp. 285, 286-341.

10. Bushnell’s Nature and the Supernatural, p. 326.

11. McIlvaine’s Evidences of Christianity, p. 307.

12. McIlvaine’s Evidences of Christianity, p. 307.

13. Age of Reason, p. 5. Paris, 1794.

14. Three Essays on Religion, p. 254.

15. History of European Morals, Vol. II, p. 9. Comparo also pp. 46, 65, 107, 163.

16. McIIvaine’s Evidences of Christianity, p. 335. Horne’s Introduction, N.Y. 1860. Vol. I. P. 25, Lecky Hist. European Morals, Vol., I., p. 51 , note.

17. McIlvaine’s Evidences of Christianity, p. 335. Horne’s Introduction, N.Y. 1860. Vol. I. p. 25, Lecky Hist. European mOrals, Vol., I., p. 51, note.

18. McIlvaine’s Evidences, pp. 333-341. Horne’s Introd., Vol. I, p. 25.

19. McIlvaine’s Evidences, pp. 333-341. Horne’s Introd. Vol. I, p. 25.

20. McIlvaine’s Evidences, pp. 333-341. Horne’s Introd. Vol. 1, p. 25.

21. McIlvaine’s Evidences, pp. 333-341. Horne’s Introd. Vol. I, p. 25.

22. McIlvaine’s Evidences, pp. 333-341. Horne’s Introd. Vol. I, p. 25.

23. Lecky’s History European Morals, Vol. I., p. 9.

24. Lamartine’s Girondists, Bohn’s Ed., Vol. III. Pp. 287-317. Carlyle’s French Revolution, Tauchnitz Ed., Vol. II. Bk. 5, Chap. 3. Morris’ French Revolution, pp. 97-125. Horne’s Introd., Vol. I., pp. 25-26.

25. Guizot’s Meditations, second series, p. 13.

26. Mr. Ingersoll more than six months after the delivery of his lecture in Chicago, on the Mistakes of Moses, and after the report of that lecture had been circulated by thousands in the streets of the city and on the trains, seeks refuge from the well-deserved castigation of his own ignorant blunders by hiding himself behind the skirts of the reporters. He says, “The lecture was never written, and consequently never delivered twice the same. On several occasions it was reported and published without revision. All these publications were grossly and glaringly incorrect.” This may account for mistakes in words and sentences. But it is impossible that all the city reporters, among whom are some of the finest stenographers in the country, should have misunderstood the drift of Mr. Ingersoll’s statements. Such a supposition is simply ridiculous. The fact that Mr. Ingersoll has quietly suppressed some of his errors and tamed down others in what he terms “the only correct edition of some of the Mistakes of Moses,” is simply due to the unspraring criticisms of some of those clergymen whom he affects to despise. Notwithstanding the above excuse, Mr. Ingersoll must father his lecture as given to the public in Haverly’s Theatre, March 23, 1879.

27. See appendix E., Ingersoll and Moses, Jansen, McClurg & Co., Chicago, 1880, p. 101.

28. Ingersoll and Moses, p. 107.

29. The same, pp. 70-77.

30. The same, pp. 78-80.

31. The same. p. 82.

32. He says, in Some Mistakes of Moses: “The real oppressor, enslaver and corrupter of the people is the Bible. That book is the chain that binds, the dungeon that holds the clergy. That book spreads the pall of superstition over the colleges and schools. That book puts out the eyes of science, and makes honest investigation a crime. That book unmans the politician and degrades the people. That book fills the world with bigotry, hypocrisy and fear.”

33. For a reply in detail to Mr. Ingersoll’s lecture on the Mistakes of Moses, delivered March 23d, 1879, the reader is referred to my book entitled, Ingersoll and Moses, Jansen, McClurg & Co., Chicago.

34. Mr. Ingersoll seems to be a deist, He says: “There may be, for aught I know, somewhere in the unknown shoreless vast, some being whose dreams are constellations and within whose thoughts the infinite exists.”

35. Lenormant, The Contemporary Review, London, November, 1879, p. 500; Compare Ingersoll and Moses, Chicago, 1880, p. 95.

36. Ingersoll and Moses, p. 42, etc.

37. See Ebers, Aegypten und Die Buecher Mose’s, Leipzig, 1868, pp. 261-360.

38. Ingersoll and Moses, pp. 63, 113.

39. Prof. Oort, who belongs to the rationalistic school of interpreters, but who is t least a man of too much scholarship to be blinded by narrow prejudices, remarks: “The touching story told to David by Nathan proves beyond all doubt that the Israelites well knew how deep the love of a man for his one wife may be. That single ewe lamb that the poor man had bought and loved so tenderly, that grew up with him and his children, ate of his bread, drank from his cup, and slept on his breast at night, represents Uriah’s one and only wife, so truly loved by her husband. So, too, in the Proverbs, the praise of a good wife is sung again and again; ‘A capable wife is the crown of her lord:’ ‘A prudent wife is a gift of Yahweh.’ Evidently, then, domestic virtue and domestic bliss were held in high esteem.”

40. Ingersoll and Moses, pp. 65, etc.

41. Compare Grote’s Plato, London, 1875, vol. III., p. 205.

42. Ingersoll and Moses, pp. 68-72; 112-113.

43. The Same, p. 113.