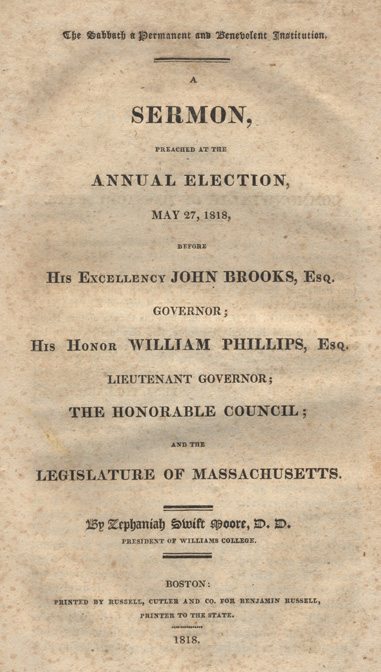

Zephaniah Swift Moore (1770-1823) graduated from Dartmouth in 1793. He was a teacher (1793-1796) and preached in Leicester, MA (1798-1811). Moore was professor of languages at Dartmouth and president of Williams College for a brief time in 1815. He was the first president of Amherst College (1821-1823). The following election sermon was preached by Moore in Massachusetts on May 27, 1818.

A

SERMON,

PREACHED AT THE

ANNUAL ELECTION,

MAY 27, 1818,

BEFORE

HIS EXCELLENCY JOHN BROOKS, Esq.

GOVERNOR;

HIS HONOR WILLIAM PHILLIPS, ESQ.

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR;

THE HONORABLE COUNCIL

AND THE

LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS.

By Zephaniah Swift Moore, D.D.

President of Williams College

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

In the House of Representative,

May 27th, 1818

Ordered, That Messrs. Porter, of Hadley, Hunt, of Northampton, Farley, of Ipswich, Osgood, of Methuen and Page, of Hallowell, be a Committee to wait upon the Reverend ZEPHANIAH SWIFT MOORE, to return him the thanks of this House, for his able and learned Discourse, this day delivered to both branches of the legislature and to request a copy for the press.

Attest,

BENJ. POLLARD, Clerk.

And he said unto them, The Sabbath was made for man and not man for the Sabbath: therefore the Son of Man is Lord also of the Sabbath.

The life of Christ was a life of benevolence. Of him it is emphatically said, “He went about doing good.” He exhibited evidence by his miracles and doctrines, that he was the Messiah and that his kingdom was not of this world. This evidence the chief men among the Jews resisted. They watched Christ, that they might discover some act, for which they might condemn him as a transgressor. No crime did they oftener allege against him, then that of violating the law of the Sabbath. When accused of this, he in no instance intimated that the law of the Sabbath is not of perpetual obligation. He performed no works on the Sabbath, but necessary works of mercy. These the law already admitted. Hence, in every instance, in which the Pharisees accused him of this crime, he effectually silenced them by appealing to the law itself; by reminding them of their own practical interpretation of the law; or by referring them to the conduct of someone, who performed necessary works of mercy on the Sabbath, but whom they never thought of accusing as a transgressor. His disciples, under pressure of hunger, plucked and ate of the corn in the field, through which they were passing to the synagogue on the Sabbath. Of this the Pharisees complained. He answered them by stating the conduct of David and his companions on the Sabbath, when they fled from Saul, and by saying, ”The Sabbath was made for man and man for the Sabbath: therefore the son of man is Lord also of the Sabbath.”

This general assertion very plainly implies that the Sabbath was not instituted for the benefit of the Jews only, but for the whole human family. To prohibit works of mercy on the Sabbath would be contrary to the benevolent design of God in appointing it and would involve the absurd notion that man was made for the benefit of the Sabbath and not the Sabbath for promoting his happiness. As anyone may do works of mercy on the Sabbath, especially might he, who is Lawgiver and Redeemer, and who has so regulated the day as to direct the attention of mankind to the greatest of all mercies, the finishing of his labours for their redemption.

The doctrine inculcated by the text, thus explained, is this,

The institution of the Sabbath is a permanent and a benevolent institution.

To elucidate this doctrine, I shall,

I. Show that the institution of the Sabbath is a permanent institution; and

II. That it is a benevolent institution.

The truth of the proposition, which asserts the perpetuity of the Sabbath, will appear, if we consider.

1. That it was appointed immediately after God had finished the work of creation. At the close of the account, which the sacred historian has given us of God’s creating the visible universe, he adds, “thus the heavens and the earth were finished and all the host of them. And on the seventh day God ended the work, which he had made; and he rested on the seventh day from all his work, which he had made. And God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it; because that on it he had rested from all his work, which God created and made.” 1 By blessing and sanctifying the seventh day we can understand nothing less, than appropriating it to religious duties exclusively. In this sense the temple and its utensils were sanctified. They were appropriated exclusively to religious services. By such an appropriation only can any portion of time be sanctified. That God did then thus sanctify the seventh day is as plainly asserted, as that he then ceased from creating. It is explicitly said, that he instituted the Sabbath on the seventh day, as it is that he created the lights in the firmament on the fourth day, animals on the fifth, and man on the sixth.

There is no circumstance in the account, which favors the opinion, that the Sabbath is here mentioned by way of anticipation. The reason given for sanctifying the seventh day prohibits this opinion. “Because that on it he had rested from all his work, which God has so wonderfully displayed his perfections, is one design of the Sabbath. In all other instances, in which God has appointed times for commemorating signal events, he has directed the celebration to commence at a period immediately succeeding the event to be celebrated. No reason can be given for a different procedure, as respects the appointment of the Sabbath.

The division of time into weeks or periods of seven days, which early and universally obtained, is a proof that the Sabbath was instituted when God had finished the work of creation. Of Cain and Abel it is said, “in process of time” they brought each of them an offering. The phrase, ”process of time,” literally rendered, is “at the end of days,” manifestly indicating that they had stated seasons of worship. These were probably the end of the days, appointed for labour, or on the seventh day, which God had blessed and sanctified.

Noah observed periods of seven days. Seven days before the flood, God commanded him to collect the animals to be preserved in the ark. When the waters were abated, he sent forth a dove, which returned. After seven days he sent forth the dove a second time, and again she returned. At the expiration of other seven days he sent forth the dove a third time. 2 In the history of Jacob and Laban a week is spoken of as a well period of time.

The Assyrians, Egyptians, Indians, Arabians and Persians have, have from time immemorial, made use of a week, consisting of seven days. The same custom prevailed among the ancient inhabitants of Greece and Italy, among the nations of the north and among almost all heathen nations, whether in some degree refined, or in the lowest state of barbarism. 3

This universal agreement in measuring time by weeks, among the nations of the earliest ages and among nations remote from each other, must have been derived from a common source. It is a measure, for which no natural reason can be given. For the division of time, into years, months and days, we can easily account. These are marked by the revolutions of the earth and moon. But there are no revolutions nor appearances in the material system, which mark periods of seven days. This division therefore must have been originally as arbitrary as a division into three, five or nine days. Yet it was from the earliest ages and among all nations without any variation in the form of it. For this there must have been some special reason. Such a reason will only account for its universal reception. “God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because that on it he had he had rested from all his works.” Here, and here only we have a satisfactory account of the origin of the division of time into weeks and here only a special and satisfactory reason for it. The division was made by God himself in the law, given to the common parents of our own race, for the sanctification of the seventh day. It is easy to see how this would be transmitted from them to Noah. From the sons of Noah and their families, all nations after the flood had their origin. From the known influence of customs, it is easy to see that this division of time would continue, even among those nations, who had in great measure lost the reason of it and whose religious notions were greatly corrupted.

This also affords the only satisfactory reason for the notions, which the ancient heathen had, of the sacredness of the seventh day. That they had such notions is evident from their poets. Homer, Hesiod and Linus term the seventh the sacred day. 4 The Pythagoreans held seven to be a perfect number, the most proper to religion and worthy of veneration. In the Hebrew, which was probably the first language, the word used to express seven, in its primitive meaning, denotes fullness, completion, sufficiency. “It is applied to a week or seven days, because that was the full time employed in the work of creation and to the Sabbath, because on it all things were completed.” From this, heathen nations derived their notions of the sacredness of the number seven. Among them a knowledge of the transactions at the creation was not entirely lost. The opinion, that they derived these notions from the Jews, has no evidence to support it. The single consideration, that the Jews were held in the utmost contempt by all idolatrous nations and all their religious rites were by them ridiculed, renders the opinion wholly improbable. The conclusion then is, that the Sabbath was instituted at the creation.

This conclusion is further supported by the manner in which the subject of the Sabbath was introduced after the Hebrews had left Egypt. Having advanced into the wilderness, they murmured for want of food—God said, “Behold I will rain bread from Heaven for you and the people shall go out and gather a certain rate every day, that I may prove them, whether they will walk with in my law or no. And it shall come to pass on the sixth day they shall prepare that which they bring in and it shall be twice as much as they gather daily.” The people obeyed this injunction and the rulers of the congregation came and informed Moses. “And he said unto them, this is that which the Lord hath said, tomorrow is the holy Sabbath unto the Lord.” 5

This account perfectly accords with the supposition that the Sabbath was now revived, the observance of which had been interrupted and perhaps wholly suspended, during the oppressive bondage of the Hebrews in Egypt. But it is wholly inconsistent with the supposition, that it had not before been instituted. The first thing commanded is a preparation for the holy rest. When that is completed, the Sabbath is mentioned as an institution previously known. “Tomorrow is the rest of the holy Sabbath unto the Lord.”

Thus is the truth of the proposition established, which exerts, that the Sabbath was appointed immediately after God had finished the work of creation. As it was then appointed, it was not designed for one individual, or for one nation, to the exclusion of others, but was designed for the whole human family. It was made for man and of course is a permanent institution. It is acceded and in perfect correctness by those who deny the early institution of the Sabbath and suppose it was not given till the days of Moses, that “if the divine command was actually delivered at the creation, it was addressed to the whole human family alike and continues unless repealed by some subsequent revelation, binding upon all who come to a knowledge of it.” 6

2. That the institution of the Sabbath is a permanent institution will appear, if we consider that the law of the Sabbath is placed in the Decalogue.

The Decalogue contains not ceremonial, but the moral law. It is an epitome of the permanent laws of this part of God’s moral kingdom. It was written by the finger of God upon two tables of stone, which by his direction were deposited in the ark of the covenant. The law of the Sabbath is here placed not as a new law, but as one already existing. “Remember the Sabbath day.” This language clearly indicates an anterior institution. That there should be no mistake with respect to the time of its appointment, the law itself refers us to the day on which God ended the work of creation.

The very manner in which the Ten Commandments were given, particularly their having been written by the finger of God himself, seem designed to show that they are the permanent laws of this part of his kingdom; and that they form no part of that system of laws which was designed for the Jews only and which was to continue only for a time. The ground on which we conclude any law is of perpetual obligation is this, the reasons for obeying it are the same in every age. This is true of all laws, which result from the unvarying relations between God and man, and between man and man. There are permanent relations, from which result permanent duties. On this ground we conclude the obligation to obey the Ten Commandments is perpetual.

The first requires that we give God the highest place in our affections. The reasons for this are always the same. They cannot very so long as God retains his worthiness and we our faculties. The sixth requires “that we use all lawful endeavors to preserve our own life and the life of others.” The reasons for this are always the same. Take the fourth, and the same rule will apply. No reason can be assigned why man when first created should be required to devote one day in seventh exclusively to religious services, which will not apply to man in every age since. No reason can be given why the Jews should be required to cease on every seventh day from all worldly occupations and devote the day to the social worship of God and other religious services, which will not apply to us and to every nation where the Scriptures are known.

The reasons for the observance of the ceremonial law and of course the obligation to observe it, ceased when Christ finished the work of atonement. But this is not true of the law of the Sabbath. The same reasons for the public and social worship of God exist now, that did from the beginning. The duties of piety are the same. The observance of the Sabbath has the same salutary influence. Men stand in the same relation to God and to a future world. Not a reason can be named for instituting the Sabbath or for observing it in an age which does not now exist in all its force. And it is not to be forgotten that it is a fixed maxim in the Divine government, that no law shall cease till the reasons for enacting it have ceased.

“No duty is more strictly moral, or of more universal obligation, that that of worshipping Almighty god. As it is our duty to join in acts of public and social worship, some fixed time must be appointed for the exercise of this duty. There is, therefore, nothing more of a positive or ceremonial nature in the sabbatical institution, than what arises form the necessity of the case,” and must exist at all times and in all places. To God it belongs to determine what portion of our time shall be exclusively devoted to religious services.

3. That the law appointed the Sabbath is a perpetual law, appears from the Scriptures of the New Testament and from the practice of the primitive Christianity.

Christ, in his memorable sermon on the mount, explicitly says that he “came not to destroy the law,” meaning the moral law contained in the Ten Commandments as is evident from the subsequent part of his discourse. “Till Heaven and earth pass, one jot or one title shall in no wise pass from the law till all be fulfilled.” The Divine law was never clothed with more authority that in this discourse of him who “spake as never man spake.”

In our text he says, “The Sabbath was made for man,” and that he himself is Lord of the Sabbath. After making known to his disciples the destruction, which would come upon Jerusalem and the persecutions which awaited his followers, he said “Pray that our flight be not on the Sabbath day.” In this he contemplated the Sabbatical institution as existing may years after his ascension. “Should the flight of his followers be on the Sabbath, they must neglect the peculiar duties of the day in consequence of the concerns that would press upon them or neglect their own safety through fear of transgressing the command of God.”

On the law of circumcision and of sacrifices, the great Apostle of the Gentiles said much. With his accustomed clearances and force of argument he shows in his epistle of the Hebrews, that the whole ceremonial law was designed to be temporary that the reasons for its continuance had ceased and that the obligation to observe it had of course ceased. But he no where intimates this of the moral law or of any of the Ten Commandments. 7 He asserts the contrary when he says, “Do we then make void the law through faith? God forbid; yea we establish the law.” This he could not have said, if the Gospel annulled any part of the moral law and especially so important a part of it as the Fourth Commandment.

The Apostles observe the Sabbath in obedience to the moral law. The primitive Christians did the same, considered the Sabbath a permanent institution. Pliny the Younger, who was Roman governor of Potus and Bithynia, two districts in which the convers to the Christian faith were numerous, in a letter written to the emperor Trajan about eighty years after the ascension of Christ, testifies that the Christians kept a day in honor of Christ. Treanoeus, who was one of the disciples of Polycarp, says “Each of us spends the Sabbath in a spiritual manner, mediating on the law of God with delight and contemplating his workmanship with admiration.”8 In this passage Trenoeus is describing not the conduct of any particular number of Christians, but of the whole of them. This is I might add the testimony of Ignatius, Athanasius, Eusebius, and others, all agreeing in the fact that the Christians everywhere observed the Sabbath as a divine institution. This universal practice of the primitive converts to the Christian faith confirms the fact that neither Christ nor the Apostles considered the law of the Sabbath otherwise than a s perpetual law.

That the disciples, after the resurrection of Christ, observed the first day of the week as the Sabbath admits of no doubt. Their meetings for religious worship were on that ay. The inference from this fact is that they were thus directed by Christ. His authority to change the Sabbath from the seventh to the first day of the week, he intimated when eh said “The son of man is Lord also of the Sabbath.” The first day of the week was early distinguished by the title “the Lord’s day,” from its having been appointed by Christ as the Sabbath and from its being kept in commemoration of his having on that day completed the work of atonement.

This change, it is easy to see, instead of implying a repeal of the law of the Sabbath is a strong confirmation of its perpetuity. Should the legislative authority of any kingdom change the day of holding a court, it would be an explicitly acknowledgment of the authority of the law which appointed the court, and a confirmation of its continuance.

Thus evident is it, that the law requiring that one day in seven be exclusively devoted to t he worship of God and other religious services is a perpetual law and binding on all persons where the law is known.

II. The Sabbath is a benevolent institution.

That this is true may be inferred from the known character of God. “The Lord is good to all and his tender mercies are over all his works.” He delights in holiness and in the diffusion of happiness. He is a holy and perfectly benevolent sovereign. In this character he planned and created the universe; and in this character he governs in all parts of his kingdom. Hence we may always know that obedience to any law which he prescribes and the observance of any institution which he appoints is connected with happiness. Men may enact laws and form institutions, the observance of which is not conducive to this end. From ignorance or from a want of benevolence they may err. But in neither of these respects is it possible for God to err. The divine goodness then assures us that the Sabbath is a benevolent institution, and the observance of it conducive to man’s highest happiness. It having been proved that it is an institution of God we cannot doubt its benevolence without impeaching his character.

But we are not left to this argument only though a conclusive one for proof of the proposition which asserts the benevolence of the Sabbath. Its truth appears form the nature and influence of the duties required on the Sabbath. Of these we have a statement in the law as written by God himself. “Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy. Six days shalt thou labor and do all thy work: But the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God; in it thou shalt not do any work, thou nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy man-servant, nor thy maid-servant, nor thy cattle, nor the stranger that is within thy gates.” That we devote ourselves exclusively to the duties of religion, the pursuits of the world are to cease. And not only are we ourselves, to cease from all worldly occupations but all over whom we have authority are to do the same. We are not to direct nor permit them to do anything, which the law does not permit us to do. They are to be employed in the duties of religion.

God has also by the prophet Isaiah, given us a still more ample account of the duties, implied in sanctifying the Sabbath. If thou turn away thy foot from the Sabbath from doing thy pleasure on my Holy day; and call the Sabbath a delight, the holy of the Lord honorable; and shalt honor him, not doing thine own ways nor finding thine own pleasure, nor speaking thine own words; then shalt thou delight thyself in the Lord. 9 This passage deserves peculiar attention, as it not only describes the duties of the Sabbath, but also the temper of mind with which they are to be performed. We are not to do our own ways which relate to our worldly occupations. We are not to find our own pleasure on the Sabbath. All those ways of spending the day, which are contrived for sensual pleasure or for mere amusement are to be avoided. As we are prohibited pursuing our ordinary labors on the Sabbath, so we are also prohibited from making them the subjects of our discourse. Our conversation ought to be suited to the sacred offices of the day.

‘This beautiful passage teaches us also what ought to be the temper of our mind in the holy exercises required. Far from being weary of the spiritual employments of the Sabbath, we ought to account them our pleasure and call the Sabbath a delight as well as holy of the Lord. This day we are to esteem honorable above all other days. This day we are to honor him who is the Creator and Redeemer of the world.’ 10 This day we are to unite in his worship and to learn from his instructions our duty as subjects of his government as being united in society placed under a dispensation of mercy and preparing for a future state of retribution.

An attention to the duties of the Sabbath is closely connected with the improvement of the intellectual powers of man. It is a well-known fact that these powers are brought to maturity only by proper culture and that their growth depends on the objects with which we are conversant. He who never raises his mind above the world whose whole soul is occupied by objects of sense and the pursuits of this world debases his intellectual nature and rises little above the brutes.

There are objects and truths with which the more intimately we are conversant the greater will be the improvement of our intellectual powers. Such are those to which our attention is directed by the duties of Sabbath. These duties direct our attention to the truths of that science which God himself has taught and which treats of his being and glorious perfections and of the nature and extent of his kingdom. They direct the mind not to the works of man but the works of the ever blessed God; not to the displays of human power and skill but to the displays of infinite power and wisdom; not to the displays of the beneficence of a creature but to the manifestations of infinite benevolence; not to systems of human jurisprudence and civil polity but to the laws and government of Jehovah. The duties and employments of the Sabbath especially direct our minds to that part of the divine economy which relates to this god now placed under a dispensation of mercy by the introduction of the mediatorial scheme in which all the divine perfections appear in their peculiar glory. They call our attention to ourselves as the creatures of God formed by his power, supported by his goodness, redeemed by his love, and the objects of his constant care; to ourselves as made a little lower than the angles, possessing capacities for endless advancement in knowledge and destined by the purpose of God for immortality.

The very nature of these truths, an attention to which is involved in all the duties of the Sabbath shows how closely they are connected with intellectual improvement. If any truths within the circle of all the sciences are fitted to enlarge and exalt the powers of the mind, certainly these are. They are truths which God himself has taught. In point of importance and sublimity they exceed all others. 11 What are the most sublime and interesting productions of human genius, when compared with that volume which bears an impress of the glories of the Divine Majesty which like the sun throws a light on every thing around us, makes the study of the works of nature pleasing and eloquent in the praise of their creator. The influence, then, of the employments of the Sabbath upon the intellectual powers of man, shows its benevolence.

But the benevolence of the sabbatical institution appears with is proper evidence from the influence an attention to its duties on the heart or moral feelings. It is well-known that all human conduct springs from these, and is directed to that which is good or to that which is evil, according as these are virtuous or vicious, sinful, or holy. The capacity for happiness depends for its increase on the improvement of the intellectual powers; but the happiness actually enjoyed depends on the temper of mind or moral feelings. On these the duties of the Sabbath are fitted to have an influence and a most important influence. Their whole tendency is to bring man to that state of moral feeling which is necessary to raise him to his true dignity, to restore him to the favor of God, and to prepare him for endless felicity. Their whole tendency is to deter men from sin and misery, and to influence them to be holy and happy. The duties of the Sabbath do this by bringing into view the character of God, the purity of his law, man’s dependence on him, and a future judgment. They constantly present arguments and motives to duty, the most powerful and persuasive.

To see the benevolence of the Sabbath in this respect in all its extent, we must view man as he is, in a state of moral degradation, and now on trial for a state of endless retribution. The testimony of him who cannot err and facts which speak too loud not to be heard and too plain not to be understood, show that man is alienated from the righteous sovereign of the universe, and has no relish of heart for the sources of heavenly happiness and that he is in his moral feelings unprepared for the employments of those blessed mansions, where all are devoted to God and where all is praise and all is love. To reclaim men from their state of moral degradation, to reunite them to the holy part of God’s empire, and prepare them for mansions of blessedness in the grand scope of the dispensation of mercy. To accomplish this infinitely benevolent design the Sabbath was instituted. It is an institution in which the sons and daughters of God Almighty are to receive their education for eternity. It was appointed with this expressly in view. All its duties and employments have an ultimate reference to this end and to this end have they, in every age of the world, been made subservient.

In every place where the Sabbath has been regarded as God requires, he has come according to his promise, granted his blessing and recorded his name. He has distinguished this institution above all others by making its exercises the means, by the accompanying influences of his spirit, of freeing men from the dominion of sin and preparing them for the kingdom of Heaven. To the appointed exercises of this day do the redeemed in Heaven look back with humble gratitude and praise, as the means of rescuing them from deserved ruin and raising them to immortal glory.

Go through Christendom and search every spot and the conclusion will be that in every place where the Sabbath is regarded by an attention to its duties, there are those who possess a preparation of heart for the society of the blessed. Go back to the garden of Eden and follow down the history of human family to the present time and the conclusion will be the same. Where this institution has been regarded according to Divine requirement, it has been like the river of god on either side of which is the tree of life, whose leaves are for the healing of the nations.

Those in every age who have renounced this institution by neglecting its duties seem to have placed themselves beyond the influence of those means, which God has mercifully appointed for their recovery from a state of moral death to a state of moral life and blessedness. Go to those places where the duties of the Sabbath are wholly neglected and search for those whose life exhibits evidence of that state of moral feeling, which prepared for the kingdom of Heaven. The search is vain. The benign influence of the Gospel of peace is not felt. The fruits of the spirit of God are not seen. No heart is warmed with love to the redeemer; no voice speaks his praise; no cheering hope in distress; darkness and despair are spread over the tomb.

In view of the influence of the exercises of the Sabbath in reclaiming the rebellious and preparing them for future blessedness, what intuitions is benevolent, if this is not? Indeed we shall never be able to comprehend the whole of the good of which it is the means, till we behold that multitude of the redeemed, which St. John in vision saw which no man could number of all nations and kindreds and people and tongues before the throne of God ascribing salvation to him that sitteth on the throne and to the Lamb.

While the exercises of the Sabbath have respect to man, as now receiving of his education for another world and are designed to direct his attention to that world as his proper home and as the place where virtue will receive its final reward, and sin its final punishment, they also have respect to his happiness here. The same state of moral feeling and the same course which leads to happiness in a future life leads to happiness in this. It is the nature of virtue to produce happiness. “As this is its natural tendency, so this is always its tendency. Wherever and how long soever it exists, the happiness of which it is the parent will also exist.” A society be it more or less numerous, possessing that character which prepared for future blessedness will be happy in this world.

If mankind loved God with all the heart there would be no idolatry on the earth, nor any of its attendant abominations. The name of God would not be profaned. There would be no perjuries nor hypocrisies, no ingratitude, pride, nor self-complacency under the smiles of Providence, nor any murmurings under its frowns. If men loved God supremely to honor and obey him would be their constant delight. If they universally loved their neighbor as themselves, there would be no wars, no envying’s, nor strife’s; no slanders, litigations, nor intrigues between neighbors; no persecuting bitterness, fraud, nor deceit; no haughtiness nor oppression among the great; no murders, robberies, nor thefts; no unkindness, treachery, nor implacable resentments among friends; no jealousies nor bitter contentions in families; in short none of those streams of death, one or more of which flows through every vein of society and poisons its enjoyments. Everyone would pursue that course and that only which would be conducive the happiness of those whom his conduct might in any way affect. Peace would prevail in families, in societies, and through the world.

Love to God and love to man constitute true virtue and are the foundation of every virtuous character. So far then as the observance of the Sabbath is connected with the formation of such characters, it is conducive to the happiness of society. To the value of such characters even for the preservation of society, God testified when he said if there were ten of this character in Sodom, he would spare the place for their sake; and Christ when he said to such “Ye are the salt of the earth, ye are the light of the world.”

The benevolence of the Sabbath appears from the influence of an attention to its duties in restraining the vicious and preventing crimes. The public worship of God is necessary to preserve in the minds of men that sense of their accountability to him without which society could not exist. It was remarked by Judge Hale of England that among all who were convicted of capital crimes while he was judge, he found a few only who would not confess on inquiry that they began their career of wickedness by a neglect of the duties of the Sabbath and vicious conduct on that day. Were we to go to the prison of this state, we should probably not be able to select one who after an honest and correct analysis of his character and of the influence which led him to the commission of crimes, of whom it would not be true that he began his downward course by a neglect and contempt of the duties of the Sabbath. Among all that have been sentenced to that prison, not one will be found who had been in the practice of observing the Sabbath till he committed the crime for which he was condemned. Those who interrupt the peace of society by their vices and crimes, are not from among those who observe the Sabbath as God has directed.

The very act of assembling together every seventh day and uniting in prayer and praise to God has a powerful tendency to unite mankind together. On the salutary influence of public worship in this respect, a writer of celebrity observed, “So many pathetic reflections are awakened by every exercise of devotion that most men carry away from public worship a better temper towards the rest of mankind than they brought with them. Sprung from the same extraction, preparing together for the period of all worldly distinctions, reminded of their mutual infirmities and common dependency, imploring support and supplies form the same great source of power and bounty, having all one interest to secure and Lord to serve, one judgment the supreme object of all their hopes and fears to look towards it is hardly possible, in this position to behold mankind as strangers, or not to regard them as children of the same family assembled before their common parent and with some portion of the tenderness which belongs to the most endearing of our domestic relations. The frequent return of such sentiments as the presence of a devout congregation naturally suggests will gradually melt down the ruggedness of many unkind passions.”12

That the Sabbath is a benevolent institution appears from its comprising in its design the religious education of the young. God has explicitly required of parents that they give religious instruction to their families. Without stated times for the performance of this duty, it would be wholly omitted. The law of the Sabbath requires that heads of families see that all under their care be devoted on that day to the duties of religion. The law as written by God himself is explicitly on this subject. The observance of it then secures the religious education of the young. It is well known that no education can supply the place of this. Instruction in human science is important; but of infinitely greater importance to their personal happiness and to the happiness of society is the religious instruction of those who are yet beginning life.

As an institution securing by its observance this important object the Sabbath stands above all others, as respects its influence on the happiness of society and as manifesting the wisdom and goodness of god. It makes those the religious instructors of the young whom they love and revere to whose example they have always looked as a pattern for their imitation and of whose ardent desire for their happiness they never doubted. In forming the tender mind the parent has an influence which no one else can have.

Much has been said by theoretical projectors in favor of certain systems of scientific and literary education to the exclusion of that which is religious, which if adopted and pursued would fit men to live under mild laws and secure to them the highest happiness attainable in the social state. These systems al involve this fundamental error that the evils which have been suffered in society and that conduct which renders severe laws necessary have arisen from a bad understanding and not from a bad heart. The history of nearly sixty centuries and the oracles of God teach us that the corrupt passion and vices of men and not their ignorance have been the cause of the evils which have been suffered and of the destruction of nations. It is a maxim, confirmed by universal history that righteousness exalteth a nation but sin is a reproach to any people.

The most effectual security against those vices which debase and ruin a people is to be found in domestic and family instruction; but not in that which excludes religion. No system of education which excludes this will lead to the practice of those virtues which are connected with social happiness and prevent those vices which render severe laws necessary.

Will it be said that most of the good effects which have been attributed to the observance of the Sabbath are to be attained to the religion of the Bible? It is admitted. But this religion has no influence where the Sabbath is disregarded. On this subject we have the evidence of facts. I need only refer you to those places and families in our own land in which the Sabbath is treated with neglect and contempt. There public and family worship are neglected; there many families do not own the sacred Scriptures and those who do neglect to read them. Let the observance of the Sabbath wholly cease for half a century in this metropolis and who would think of looking here for piety or the practice of any of the Christian virtues or even for a single Bible? Let the observance of the Sabbath wholly cease for the same period of time in this Commonwealth and what would be its religious and moral character? Go to those places within the limits of the United States where there has been no Sabbath for only half that period and they will tell you. How vulnerable, how benevolent is the institution which ever has been and still is the means of preserving the religion of God in the world and of perpetuating all its happy influences.

From the doctrine of the text thus illustrated we may see why God has so often manifested his displeasure against those who have disregarded the Sabbath. Transgressions of the law of the Sabbath are oftener referred to in the Scriptures than any others as the procuring cause of the displeasure of God. The reason is obvious. On its observance depends the observance of all the other laws of God, the whole influence of the religion which he has given the progress of the work of redemption and the happiness of man in this and the future world. Hence the same benevolence, the same tender regard to the happiness of man which influenced God to institute the Sabbath, influences him to express in a most solemn manner his displeasure against any people who despise and neglect its duties. When other motives have no influence, exemplary punishment is sure to be inflicted. The history of ancient Israel is fully illustrative of this. The indignation of Infinite Benevolence against those who despise this institution will be proportionate to his regard for the happiness of man and his own glory.

From the subject we may see how we ought to feel in view of the prevailing neglect and open violations of the law of the Sabbath. It is a fact which cannot be concealed that there is no law of God oftener transgressed than this. Instead of devoting the day exclusively to the worship of God and the duties of religion not a few pursue with their wonted eagerness the business of the world. In too many instances other employments take the place of the duties of the sanctuary, other books the place of the Bible and other conversation the place of that which is religious. How have we degenerated in our attention to the duties of this instruction form the practice of our venerable ancestors. In too many instances the evil is increased by the example of those who are high in authority who are respected for their talents and who would not be thought unfriendly to the best interests of our country. Of such may we not say, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” They know not that they are as really violating the law of God as those who clandestinely take the property of others, are acting against the best interests of society and pursuing a course and forming a character which infinite purity must and will condemn. In view of the prevailing neglect and open violations of the Sabbath, we ought to feel that deep concern which the preservation of an institution requires, on which depends the continuance of all that rich inheritance of civil, social, and religious blessings, transmitted to us by our fathers and on which depends the happiness, the endless happiness, of unborn millions.

With gratitude to Him who had distinguished us by his goodness, we behold dour civil rulers presenting themselves before the Lord for his direction and blessing.

His Excellency, the Chief Magistrate of this Commonwealth, has renewed testimony of the approbation of his fellow citizens and will not accept our very respectful congratulations. Confidence that he will, by his authority and example, continue to support the institutions of that God who has, in war and peace, been his protector and benefactor, we wish him his blessing. May he continue to execute his trust with integrity and impartiality and when he shall have finished with the cares of this world may he be admitted to the rewards of the just.

His Honor, the Lieutenant Governor, will accept our cordial congratulations on the renewed expression of the confidence of the Commonwealth in his integrity, public spirit, and patriotism. Having esteemed the Sabbath a delight, holy of the Lord, honorable and having remembered the words of him who is Lord of Sabbath, how he said, “It is more blessed to give than to receive,” may he, when he shall have finished the duties of this lie be admitted to the enjoyment of a never ending Sabbath in the kingdom of the blessed.

The Honorable Council from the dignity of their station and the fidelity with which they discharge their trust, merit and receive our respectful attention. May He, who cannot err in counsel, be their guide and may their receive the reward of the faithful.

The Honorable Senate and House of Representatives will accept our high respects.

The view which has been taken of the perpetuity and benevolence of the Sabbath is familiar to a Legislature which has said “that an uniform and enlightened observance of the Lord’s day is solemnly binding on the conscience of every individual; that without the appointment and continuance of the Lord’s day public instruction and worship would soon languish and perhaps entirely cease; that private worship and the best virtues of social life would share the same fate; that the Scriptures containing the records, the principles, the duties, and the hopes of our religious would pass from the recollection of multitudes of our citizens who now regard them and never become known to the great body of the rising generation; that the powerful and happy influence which they now exert upon public sentiment and morals would be seen no longer; that the powerful and happy influence, which they now exert upon public sentiment and morals, would be seen no longer; that the safety of the State, the moral and religious improvement of the people, the personal security and happiness of all are intimately connected with the uniform and conscientious observance of the Lord’s day.” 13

These sentiments are such as add dignity to a Christian Legislature. They are expressive of views and feelings like those of our venerable ancestors. They have gladdened the heart and excited the confidence of every friend to the best interest of the Commonwealth. They assure us that as the guardians of the State you feel yourselves bound to protect by your example, by your united efforts, and by laws so far as laws will protect, the Sabbath from open violation. We are assured that with these enlightened views of the influence of the observance of the Sabbath, you will consider yourselves as “more effectually protecting individuals in the possession of their property, their reputation, and their lives, by interposing to preserve the Sabbath from neglect and contempt than by any other exercise of your power.” We are assured that, collected form every part of the state, possessing a full view of the prevailing violations of the Sabbath and a knowledge of the existing laws for tis protection, if further legislative interposition is necessary, you will interpose. If the fault is wholly in those who are entrusted with the execution of the laws how solemn must be their account to him who are appointed the Sabbath. The oath of the Lord is upon them. Will he accept the excuses which they now offer for their neglect?

You will allow me to observe that by protecting the Sabbath from open violation, you set up a rampart around the paternal government and wholesome laws of the Commonwealth which will better secure their observance than millions expended in erecting prisons. To protect the Sabbath then is the part of kindness and benevolence.

Impressed with a deep sense of your responsibility to God in the care you take of the Commonwealth you cannot for a moment be influenced by the feelings of those who complain of all laws, restraining them on the Sabbath as oppressive and vexatious. You will deeply regret the want of discernment in those who can see no difference between a national religious establishment and the legislative protection of an institution appointed by the benevolent sovereign of the universe for the happiness of the whole human family.

As the legislators and guardians of the rights and liberties of more than seven hundred thousand people, may you be under the guidance of him whose wisdom is infinite, and be the ministers of the God for good.

The subject reminds this whole assembly of their obligation to bless God for the institution of the Sabbath. It also reminds them of their obligation to attend to all tis duties, that they may obtain the blessings of which it is designed to be the means. Duty and interest impose upon as all a sacred obligation to set our hearts to all the words of God’s law and especially to this institution for it is our life.

“If thou turn away thy foot from the Sabbath from doing thy pleasure on my holy day; and call the Sabbath a delight, holy of the Lord honorable; and shalt honor him, not doing thine own ways, nor finding thine own pleasure, nor speaking thine own words; then shalt thou delight thyself in the Lord; and I will cause thee to ride upon the high places of the earth and feed thee with the heritage of Jacob; for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it.”

“Blessed is the man that keepeth the Sabbath from polluting it.”

Endnotes

1. Genesis II 1,2,3.

2. Genesis vii. 4 viii. 10,12.

3. President De Goguet, Origin of Laws, vol. i. p. 230. Grotius, Rollin and others, as referred to by Doddridge, Leet, exxvi.

4. These poets are quoted by Aristobulus, a learned Jew, by Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius. By each of them the seventh is called the sacred day. Encyclopedia, art. Sabbath.

5. Exodus. xvi. chap.

6. Paley’s Prin. Mor. And Plit. Book v. chap 7. The sentiments of this very interesting writer have had a very extensive influence, in weakening a sense of obligation strictly to observe the Sabbath. He wholly mistakes as to the time when the Sabbath was instituted ; classes the law appointing it among those , which were peculiar to the Jews ; and deduces the obligations to observe a Sabbath now from considerations of expediency merely. It is to be regretted that he did not attend with more care to the arguments, which have never yet been answered, in support of the primeval institution of the Sabbath.

7. There are two passages in the Epistles of Paul which to the inattentive reader may seem to favor the opinion that the law of the Sabbath has ceased under the Gospel dispensation. Rom. xiv, 15 and Coloss. Ii. 16. A very little attention to the context will convince anyone, that these passages have respect to the ceremonial law which was designed to cease under the Gospel dispensation and that they have no respect to the Sabbath of the fourth commandment, which was appointed at the creation and was never a part of the ceremonial law.

8. Unusquiesque nostum sabbatizat spiritulaiter, mulitatione legis gaudens, oppoisnum Dei admivans.” According to Eusebius Trenoeus was born at Smyrna, about the year 140 and was one of Polycarp’s disciples.

9. Isaiah lviii. 13, 14.

10. The Christian Observer, Vol. I, p. 419.

11. The following testimony of Sir William Jones was transcribed by his biographer, Lord Teignmouth, from his own manuscript in his Bible. “I have carefully and regularly perused these holy Scriptures; and am of opinion that the volume, independently of its divine origin, contains more infinite e sublimity, purer morality, more important history, and finer strains of eloquence, than can be collected from all other books in whatever language they may have been written.” Memoirs of the Life of Sir William Jones, page 374.

12. Paley’s Mor. And Polit. Phil. Book v. chap. 4.

13. Report of the Legislature of 1814.