The Civil War

Casual students of the Civil War often disagree about whether the War was fought over slavery, unjust economic policies, or “states’ rights.” Yet for millions of Americans in the 1860s, their reason for going to war is different. It can be found in a famous 1830 speech made by Daniel Webster in the US Senate.

At that time, South Carolina was threatening secession. On the floor of the Senate, Webster eloquently proved that there was no such right and that to secede would be an act of treason. (Founding Fathers such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Quincy Adams, and others had rejected the doctrine of secession, later used by the Confederacy.) The closing words of Webster’s speech have become some of the most famous in American history:

When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union. . . . Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous [flag] of the republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced . . . not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured . . . [A]s they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, [may they unfurl] that sentiment dear to every true American heart: Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!

Black Americans

Liberty and Union. For millions in 1861, this was the driving motivation: Liberty (ending slavery), and Union (keeping the nation intact). Pursuing that double objective resulted in over 600,000 American lives being lost. Additionally, 410,000 were maimed and crippled. Thus, the Civil War was the bloodiest war in American history. Black Americans were not just spectators; from running the Underground Railroad to leading the charge in battle, they were often active participants.

Black Americans fought bravely in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, but their service in the Civil War silenced the myth that blacks could not perform well in battle. In fact, the battlefield bravery and tactical skill of black soldiers not only met but often surpassed that of their counterparts. And their deep Christian faith was just as visible as was their great courage.

The examples of distinguished black soldiers in the Civil War are many, but this issue will profile three heroic individuals.

Robert Smalls (1839-1916)

Robert Smalls was raised as a slave in Charleston, South Carolina, where he learned how to pilot large vessels along the Atlantic seaboard. He earned a reputation for exceptional navigational skills. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he was forced into service for the Confederacy as quartermaster on the Planter, a 300-ton side-wheel steamer. As quartermaster, Smalls was in charge of the ship’s steering. He was thus the de facto pilot of the Planter, but he did not hold that title. Such an important post was not allowed a black slave in the Confederate south.

The Planter

On the evening of May 12, 1862, the Planter was docked in Charleston. The Confederate officers left the ship to attend a party onshore, leaving Smalls and the rest of the crew to ready the ship for departure the next morning. Always watchful for an opportunity to gain his freedom, and recognizing the potential in this situation, Smalls alerted the families of the crew to be in hiding nearby. Upon receiving his signal, they quickly boarded the ship.

Smalls took the wheel and quietly headed toward open sea. Knowing he would have to pilot the ship past Confederate sentinels, he donned the captain’s clothing and hoisted the Confederate flag. Moving the ship along slowly, and blowing the usual signals, Smalls was successful in not attracting unwanted attention. In fact, a Confederate soldier later reported that he saw the Planter moving but didn’t “think it necessary to stop her, presuming that she was but pursuing her usual business.”

Sneaking Past Fort Sumter

Having surmounted the dangers of the initial departure, Smalls and his crew still faced two major obstacles. The first was Fort Johnson (which Smalls safely passed, giving the customary steam-whistle salute). The second – and much more ominous threat – was Fort Sumter, the starting place of the Civil War. As the Planter approached its stark gray walls, some of Smalls’ crew urged him to turn back, fearing that the Sumter guards would board and inspect the ship.

Smalls cried out to God: “Oh, Lord, we entrust ourselves into Thy hands. Like Thou didst for the Israelites in Egypt, please stand guard over us and guide us to our promised land of freedom.” Rather than retreating, he continued bravely on. He knew that if they were stopped or shot, at least they would enter Heaven as free men.

As they approached Fort Sumter, Smalls – still wearing the familiar hat and coat of the captain – turned his back slightly to the sentry in order to obscure his own face. He then signaled with the whistle, asking for permission to pass. The crew waited in tense expectation. After what seemed like hours, the Confederate guard finally answered, “Pass the Planter!”

To Freedom

Even though the most difficult part of the escape was now behind them, it was still too early to celebrate. When the Planter eventually reached the outer edge of Confederate waters, Smalls replaced the Rebel flag with a white sheet of surrender – but nearly too late. The commander of an oncoming Union vessel, the US Onward, had almost given the command to fire on the Planter before recognizing the flag of truce. He guided his ship alongside the Planter and the Union crew boarded the vessel. When they asked for the captain, Smalls proudly answered, “I have the honor, sir, to present the Planter, formerly the flagship of General Ripley!”

The ship was now in Union hands. Even more valuable to the Union was Smalls’ extensive knowledge of Confederate placements around Charleston. Upon delivering the ship, Smalls explained with a wry smile, “I thought they might be of some service to Uncle Abe.”

The Union Navy

President Lincoln personally invited Robert Smalls to Washington, where he and his crew were recognized for their bravery. Smalls was then commissioned as Second Lieutenant in the 33rd Regiment of United States Colored Troops. (For a black American to be commissioned as an officer was extremely rare and was an exceptional honor. At that time, most officers – even of black troops – were white.)

After receiving his commission, Smalls was made the official pilot of the Planter, now sailing for the Union. The Planter was assigned to transport service, delivering supplies along the coastal waterway near Charleston.

On a routine trip in November 1863, the Planter came under Confederate bombardment. The shelling proved so intense that the Union captain of the ship panicked, wanting to surrender. Smalls refused, knowing that he and the crew would be killed if captured. (The Confederacy had issued orders that blacks who surrendered were to be put to death on the spot.) The frightened Captain fled below deck, leaving Smalls in charge. He brought the ship safely through the shelling, landing amidst the cheers of thousands gathered at the dock awaiting the supplies. Union Major General Quincy Gillmore promoted Smalls to Captain, a position he held until the end of the war. Smalls eventually rose to the rank of Major General in the South Carolina Militia.

In Congress

After the War, Smalls was elected as a Republican to the South Carolina House. He was later elected to the United States Congress, where he served for nine years. As a Member of Congress, he pursued equal treatment for black Americans. As he explained: “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Robert Smalls was a strong Christian, whose faith was evident in both the military and the political arena.

Andre Cailloux (1825-1863)

Andre Cailloux was a member of the Afro-Creole community of New Orleans. (The Afro-Creoles were French in language and culture, and Roman Catholic in faith.) Cailloux was a pioneer in black American military history. Although born into slavery, he received his freedom in 1846. He then quickly began to make his mark as a leader within what was considered one of the most prosperous black regions in the nation. Cailloux received a formal education. He later married, purchased a home, and bought his mother out of slavery. He also sent his sons to a prestigious school and was elected to various posts within the Afro-Creole community.

During the Civil War

At the outbreak of the Civil War, most battlefield activity initially occurred far from Louisiana, in the North and the East. With the Union’s desire to break the communication and supply lines of the Confederates, gaining control of the Mississippi River became a priority. In April 1862, the Union army captured New Orleans. It authorized the formation of the Louisiana Native Guards: black Americans from New Orleans who would fight for the Union.

In 1862, Cailloux was commissioned as captain of E Company in the 1st Regiment of Louisiana Native Guards. This was the first black regiment officially recognized for military service in the Civil War. Upon receiving his commission, Cailloux began recruiting both free men of color and runaway slaves from the New Orleans region.

An imposing figure in character and stature, Cailloux was a direct visual repudiation to the image of black servility, inferiority, and cowardice long perpetuated by racists. His gentlemanly demeanor, athletic build, and keen intelligence gave him a confidence and charisma that made him a natural to help lead the newly formed Louisiana Native Guards.

Cailloux and his men faced many challenges – and not all from their Confederate enemy. Too often they had to endure insults from white troops, insufficient supplies (less than what their white counterparts often received), and excessive manual labor pushed on them by lazy soldiers. Nevertheless, they continued to train, anxious to prove their mettle on the battlefield.

Ultimate Sacrifice

That opportunity arrived in May 1863. The Confederate stronghold of Port Hudson on the Mississippi River (north of Baton Rouge) was under siege. The forces were led by Union General Nathaniel P. Banks. The 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards was assigned to Banks and were chosen to mount an attack on the heavily fortified bluffs and rifle pits protecting Port Hudson. It was a critical but dangerous assignment. Cailloux’s E Company was designated to lead the charge as the standard bearer for the entire regiment.

As the regiment took the field, Cailloux encouraged his men with calm words of assurance. They charged and were met by extremely heavy Confederate fire. Cailloux and the other officers regrouped and rallied their men on several occasions. At last, Cailloux led a charge all the way to the backwater of the Port, just 200 yards shy of the bluffs. He and his men finally got off a round of musket shot, only to be answered with a wave of Confederate artillery. Their losses were heavy; and Cailloux himself was wounded, taking a bullet through his arm just above his elbow. He rallied his men once again and charged across the muddy waters toward the bluffs, his useless arm dangling beside him. This charge was his final heroic act; he received a fatal blow in the head from an enemy shell.

All along the line, Union forces were pushed back with heavy casualties. Both the 1st and the 3rd Regiments were finally forced to break ranks and seek shelter in the surrounding willow trees. Nevertheless, the bravery of Andre Cailloux did not go unnoticed, or the actions of so many of his troops who fought fiercely against overwhelming odds.

Black Soldiers in the Civil War

The story of Cailloux and his men quickly spread across the North. The false stereotype had been shattered and the black soldier was now viewed as a valuable and integral part of the war. This reputation was strengthened with the accomplishments of the Native Guards’ counterparts in the North, the Massachusetts 54th. By the end of the Civil War, some 180,000 black Americans had fought in the United States Armed Forces.

Andre Cailloux – a hero in New Orleans – received a hero’s funeral. He laid in-state for four days, watched over by a military guard. His funeral procession was led by a band of musicians playing somber dirges followed by a horse-drawn, tasseled caisson with Cailloux’s body. Mourners lined the streets for almost a mile along the funeral route, holding tiny American flags as his remains rolled by. The attack in which Cailloux lost his life had been unsuccessful. (As was a subsequent attack two weeks later.) Union General Banks eventually pulled back and laid siege to Port Hudson, forcing their surrender a month-and-a-half later. That surrender was considered one of the Confederacy’s most devastating defeats, opening the Mississippi River to Union troop and supply movements.

Over 12,000 lives were lost at Port Hudson. 5,000 of which were Union deaths with many occurring during the initial attack led by Cailloux. Nevertheless, the attack had not only produced the first black hero of the Civil War, it also proved the strength and courage of black American troops. Thus firmly cementing their permanent place in future American military service.

William Carney (1840-1908)

Sergeant William H. Carney – another black American renowned for his heroism – was born into slavery in Norfolk, Virginia. While William was still a boy, his father escaped to freedom on the Underground Railroad. He soon purchased the family out of slavery and brought them to New Bedford, Massachusetts.

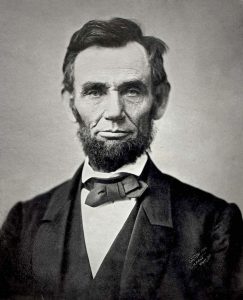

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War, black Americans – both slave and free – believed that God would use President Abraham Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant to bring them freedom in the same way that God had used Moses to lead the Israelites out of captivity. Viewing abolition as a spiritual mission made black Americans all the more eager to help, thereby hastening the arrival of freedom.

Joining the US Military

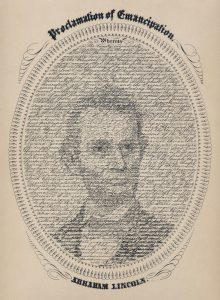

In 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The Union Army also began actively recruiting black volunteers. William understood the powerful spiritual dimension of emancipation and eagerly enlisted. This decision sprang from his deep Christian convictions. As he explained: “Previous to the formation of colored troops, I had a strong inclination to prepare myself for the ministry; but when the country called for all persons, I could best serve my God [by] serving my country and my oppressed brothers.”

Carney joined the Morgan Guards, who later became part of the Massachusetts 54th (featured in the 1989 movie Glory). The regiment was led by the 25 year-old white Colonel Robert Shaw, son of prominent Boston abolitionists. The all-black 54th had freeborn men and former slaves, including two sons of Frederick Douglass who played a major role in establishing the 54th. Upon completing their training, the 54th was assigned to attack Fort Wagner, South Carolina.

Fort Wagner

On the evening of July 18, 1863, the 600 men of the 54th lay along the sandy beach 1,000 yards from Fort Wagner. Chosen to lead the charge, they were awaiting orders to move out. Union guns had pounded the Confederate stronghold all day long, attempting to weaken its defenses. That evening, the order to advance finally came.

The men set with fixed bayonets, running toward the enemy. But the Union bombardment had failed to weaken the gun emplacements, so the 54th ran into heavy Confederate cannon fire and torrents of bullets. They suffered extensive casualties. Among those who fell was Sergeant John Wall, the carrier of the United States flag. Sergeant William Carney, who had been running next to Wall, dropped his rifle and caught the flag before it could hit the ground.

Protecting the Flag

As Carney carried the flag, he was shot in the leg, but he continued to lead the attack. Ignoring the searing pain, he and his forces pushed forward and were able to gain control of a small part of the fort. Carney proudly planted the American flag and held his position against the wall of Fort Wagner for nearly half an hour through hand-to-hand combat. In the darkness of the night, Carney saw troops moving toward him and made the mistake of believing them to be fellow Union fighters. Suddenly surrounded by Confederate soldiers, he quickly wrapped the flag around its staff as his unit fell back down the embankment.

Retreating across the chest high water, he held the flag high. He was shot twice more, once in the chest and again in the leg. Still, he continued on, resolved not to let the flag fall. A member of another regiment pleaded with the injured Carney to let him carry the flag, but he quickly replied, “No one but a member of the 54th should carry the colors.” Carney was shot again (for the fourth time), this time narrowly escaping death as the bullet creased his skull. At last he reached the safety of what remained of the 54th. He proclaimed breathlessly before collapsing, “Boys, I only did my duty. The flag never touched the ground.”

After the Battle

The attack against Fort Wagner was unsuccessful, and the battle was a defeat for the Union. The total lives lost that day were 351, only twelve of whom had been Confederates. But the 54th had acquitted itself courageously, just like their counterparts in the Louisiana Native Guards.

On May 23, 1900, Sergeant William Harvey Carney was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. (Several black Americans had already received the prestigious award for gallantry in both the Civil War and the subsequent western Indian Campaigns. However, Carney’s heroism at Fort Wagner was the earliest action of the Civil War to be recognized.)

He died eight years later in New Bedford, still strong in his Christian faith. His grave is marked with a gold image of his nation’s highest award for valor in battle.

Conclusion

The list of black American heroes of the Civil War is long and impressive. All the more impressive is that many of these men not only fought bravely against the enemy but also against occasional racism in their own army. Admirably, their response to racist opposition did not include personal animosity, bitterness, or hate, but rather an increased determination to prove wrong the misconceptions. In fact, to have harbored destructive feelings of ill-will would have violated their strong Christian faith. They lived by Biblical admonitions such as those delivered long before by the Rev. Richard Allen (himself a former slave), who had urged:

[L]et no rancor or ill-will lodge in your [heart] for any bad treatment you may have received from any. If you do, you transgress against God, Who will not hold you guiltless. He would not suffer it even in His beloved people Israel; and you think He will allow it unto us? . . . I am sorry to say that too many think more of the evil than of the good they have received.

The illustrious stories of Robert Smalls, Andre Cailloux, and William Carney are the stories of heroes who not only followed the teachings of Christianity but who also fought with exceptional courage, doing the work of the Lord in “Liberty and Union.”

“Be strong and of a good courage;

fear not, nor be afraid of them,

for the Lord thy God –

He it is that doth go with thee;

He will not fail thee

nor forsake thee.”

Deuteronomy 31:6, Joshua 1:9

This quote probably remains as accurate today as it was 100 years ago when it was made by famous black pastor Francis James Grimké. 1

This quote probably remains as accurate today as it was 100 years ago when it was made by famous black pastor Francis James Grimké. 1 Grimké pastored this church for almost 50 years,6 and during one of his sermons, he reminded his congregation:

Grimké pastored this church for almost 50 years,6 and during one of his sermons, he reminded his congregation:

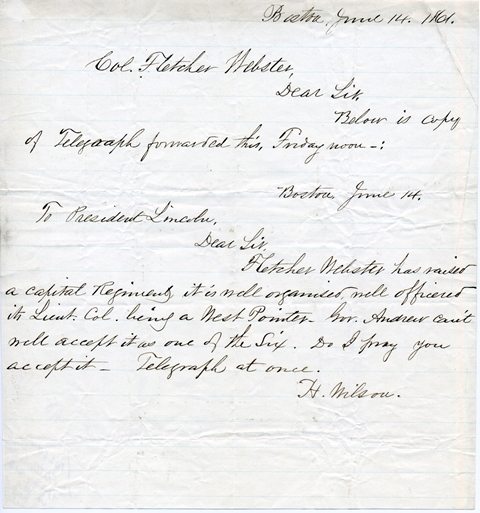

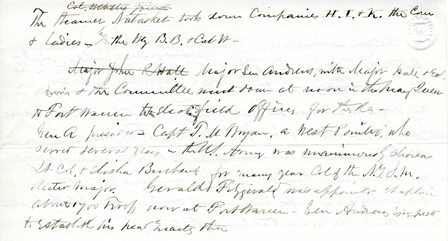

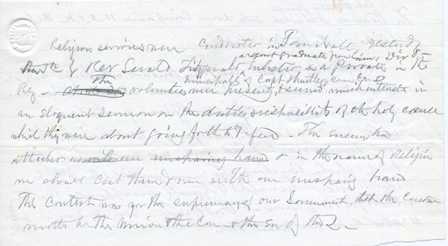

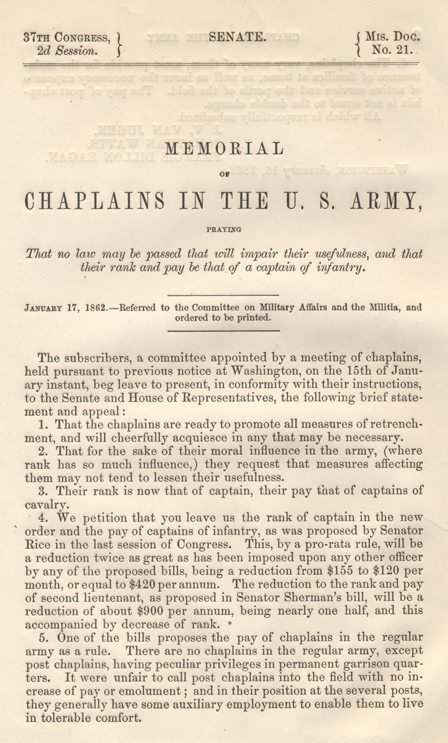

An anniversary occurs each April of an 1861 event: the formation of the Twelfth Massachusetts Regiment. Benjamin F. Cook, who enlisted as a Union private in the Civil War and quickly rose through the ranks, was later tasked by his comrades with documenting the history of that regiment.

An anniversary occurs each April of an 1861 event: the formation of the Twelfth Massachusetts Regiment. Benjamin F. Cook, who enlisted as a Union private in the Civil War and quickly rose through the ranks, was later tasked by his comrades with documenting the history of that regiment. Webster concluded that speech by stating:

Webster concluded that speech by stating:

The

The  Lincoln learned to read from the Bible,

Lincoln learned to read from the Bible,