The rewriting of history in any area is possible only if: (1) the public does not know enough about specific events to object when a wrong view is introduced; or (2) the discovery of previously unknown historical material brings to light new facts that require a correction of the previous view. However, historical revisionism – the rewriting “of an accepted, usually long-standing view especially a revision of historical events and movements” 1 – is successful only through the first means.

Over the past sixty years, many groups, exploiting a general lack of public knowledge about particular movements or events, have urged upon the public various revisionist views in order to justify their particular agenda. For example, those who use activist courts to advance policies they are unable to pass through the normal legislative process defend judicial abuse by asserting three historically unfounded doctrines: (1) the judiciary is to protect the minority from the majority; (2) the judiciary exists to review and correct the acts of elective bodies; and (3) the judiciary is best equipped to “evolve” the culture to the needs of an ever-changing society. These claims are directly refuted by original constitutional writings, especially The Federalist Papers. (See also the WallBuilders’ book, Restraining Judicial Activism.)

Likewise, those who pursue a secular public square seek to justify their agenda by asserting that the Founding Fathers: (1) were atheists, agnostics, and deists, and (2) wrote into the Constitution a strict separation of church and state requiring the exclusion of religious expressions from the public arena. These claims are also easily rebuttable through the Founders’ own writings and public acts. (See also the WallBuilders’ book, Original Intent.)

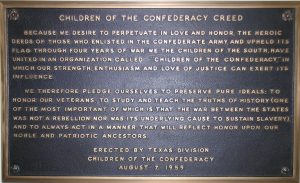

A third example of historical revisionism involves the claim that the 1860-1861 secession of the Southern States which caused the Civil War was not a result of the slavery issue but rather of oppressive federal economic policies. For example, a plaque in the Texas State Capitol declares:

Because we desire to perpetuate, in love and honor, the heroic deeds of those who enlisted in the Confederate Army and upheld its flag through four years of war, we, the children of the South, have united together in an organization called “Children of the Confederacy,” in which our strength, enthusiasm, and love of justice can exert its influence. We therefore pledge ourselves to preserve pure ideals; to honor our veterans; to study and teach the truths of history (one of the most important of which is that the war between the states was not a rebellion nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery), and to always act in a manner that will reflect honor upon our noble and patriotic ancestors. (emphasis added)

Other sources make the same false claim, 2 but four notable categories of Confederate records disprove these claims and indisputably show that the South’s desire to preserve slavery was indisputably the driving reason for the formation of the Confederacy.

1. Southern Secession Documents

From December 1860 through August 1861, the southern states met individually in their respective state conventions to decide whether to secede from the Union. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first state to decide in the affirmative, and its secession document repeatedly declared that it was leaving the Union to preserve slavery:

[A]n increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding [i.e., northern] states to the institution of slavery has led to a disregard of their obligations. . . . [T]hey have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery. . . . They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes [through the Underground Railroad]. . . . A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the states north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States [Abraham Lincoln] whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. He is to be entrusted with the administration of the common government because he has declared that “Government cannot endure permanently half slave, half free,” and that the public mind must rest in the belief that slavery is in the course of ultimate extinction. . . . The slaveholding states will no longer have the power of self-government or self-protection [over the issue of slavery] . . . 3

Following its secession, South Carolina requested the other southern states to join them in forming a southern Confederacy, explaining:

We . . . [are] dissolving a union with non-slaveholding confederates and seeking a confederation with slaveholding states. Experience has proved that slaveholding states cannot be safe in subjection to non-slaveholding states. . . . The people of the North have not left us in doubt as to their designs and policy. United as a section in the late presidential election, they have elected as the exponent of their policy one [Abraham Lincoln] who has openly declared that all the states of the United States must be made Free States or Slave States. . . . In spite of all disclaimers and professions [i.e., measures such as the Corwin Amendment, written to assure the southern states that Congress would not abolish slavery], there can be but one end by the submission by the South to the rule of a sectional anti-slavery government at Washington; and that end, directly or indirectly, must be the emancipation of the slaves of the South. . . . The people of the non-slaveholding North are not, and cannot be safe associates of the slaveholding South under a common government. . . . Citizens of the slaveholding states of the United States! . . . South Carolina desires no destiny separate from yours. . . . We ask you to join us in forming a Confederacy of Slaveholding States. 4

On January 9, 1861, Mississippi became the second state to secede, announcing:

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world. . . . [A] blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin. That we do not overstate the dangers to our institution [slavery], a reference to a few facts will sufficiently prove. The hostility to this institution commenced before the adoption of the Constitution and was manifested in the well-known Ordinance of 1787. [On July 13, 1787, when the nation still governed itself under the Articles of Confederation, the Continental Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance (which Mississippi here calls the “well-known Ordinance of 1787”). That Ordinance set forth provisions whereby the Northwest Territory could become states in the United States, and eventually the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota were formed from that Territory. As a requirement for statehood and entry into the United States, Article 6 of that Ordinance stipulated: “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory.”

When the Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation, the Founding Fathers re-passed the “Northwest Ordinance” to ensure its continued effectiveness under the new Constitution. Signed into law by President George Washington on August 7, 1789, it retained the prohibition against slavery.

As more territory was gradually ceded to the United States (the Southern Territory – Mississippi and Alabama; the Missouri Territory – Missouri and Arkansas; etc.), Congress applied the requirements of the Ordinance to those new territories. Mississippi had originally entered the United States under the requirement that it not allow slavery, and it is here objecting not only to that requirement of its own admission to the United States but also to that requirement for the admission of other states.]. . . It has grown until it denies the right of property in slaves and refuses protection to that right on the high seas [Congress banned the importation of slaves into America in 1808], in the territories [in the Northwest Ordinance of 1789, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854], and wherever the government of the United States had jurisdiction. . . . It advocates Negro equality, socially and politically. . . . We must either submit to degradation and to the loss of property [i.e., slaves] worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union framed by our fathers to secure this as well as every other species of property. 5

(Notice that the Union’s claim that blacks and whites were equal both “socially and politically” was a claim too offensive for southern Democrat states to tolerate.)

Following its secession, Mississippi sent Fulton Anderson to the Virginia secession convention, where he told its delegates that Mississippi had seceded because they had unanimously approved a document “setting forth the grievances of the Southern people on the slavery question.” 6

On January 10, 1861, Florida became the third state to secede. In its preliminary resolutions setting forth reasons for secession, it acknowledged:

All hope of preserving the Union upon terms consistent with the safety and honor of the Slaveholding States has been finally dissipated by the recent indications of the strength of the anti-slavery sentiment in the Free States. 7

On January 11, 1861, Alabama became the fourth state to secede. Like the three states before her, Alabama’s document cited slavery; and it also cited the 1860 election victory of the Republicans as a further reason for secession, specifically condemning . . .

. . . the election of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin to the offices of President and Vice-President of the United States of America by a sectional party [the Republicans], avowedly hostile to the domestic institutions [slavery] and to the peace and security of the people of the State of Alabama . . . 8

Georgia similarly invoked the 1860 Republican victory as a cause for secession, explaining:

A brief history of the rise, progress, and policy of anti-slavery and the political organization into whose hands the administration of the federal government has been committed [i.e., the Republican Party] will fully justify the pronounced verdict of the people of Georgia [in favor of secession]. The party of Lincoln, called the Republican Party under its present name and organization, is of recent origin. It is admitted to be an anti-slavery party. . . . The prohibition of slavery in the territories, hostility to it everywhere, the equality of the black and white races, disregard of all constitutional guarantees in its favor, were boldly proclaimed by its [Republican] leaders and applauded by its followers. . . . [T]he abolitionists and their allies in the northern states have been engaged in constant efforts to subvert our institutions [i.e., slavery]. 9

Why was the Republican election victory a cause for secession? Because the Republican Party had been formed in May of 1854 on the almost singular issue of opposition to slavery (see WallBuilders’ work, American History in Black and White). Only six years later (in the election of 1860), voters gave Republicans control of the federal government, awarding them the presidency, the House, and the Senate.

The Republican agenda was clear, for every platform since its inception had boldly denounced slavery. In fact, when the U. S. Supreme Court delivered the 1857 Dred Scott ruling protecting slavery and declaring that Congress could not prohibit it even in federal territories, 10 the Republican platform strongly condemned that ruling and reaffirmed the right of Congress to ban slavery in the territories. 11 But setting forth an opposite view, the Democrat platform praised the Dred Scott ruling 12 and the continuation of slavery 13 and also loudly denounced all anti-slavery and abolition efforts. 14

The antagonistic position between the two parties over the slavery issue was clear; so when voters gave Republicans control of the federal government in 1860, southern slave-holding Democrat states saw the proverbial “handwriting on the wall” and promptly left the United States before Republicans could make good on their anti-slavery promises. It was for this reason that so many of the seceded states referenced the Republican victory in their secession documents.

It was not just southern Democrats who viewed the election of Lincoln and the Republicans as the death knell for slavery; many northern Democrats held the same view. In fact, New York City Democrat Mayor Fernando Wood not only attacked the Republican position on slavery but he also urged New York City to join with the South and secede, explaining:

With our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States, we have friendly relations and a common sympathy. We have not participated in the warfare upon their constitutional rights [of slaveholding] or their domestic institutions [slavery]. . . . It is certain that a dissolution [secession of the State of New York from the Union] cannot be peacefully accomplished except by the consent of the [Republican New York] Legislature itself. . . . [and] it is not probable that a partisan [Republican] majority will consent to a separation. . . . [So] why should not New York City, instead of supporting by her contributions in revenue two-thirds of the expenses of the United States, become also equally independent [i.e., secede]? . . . In this she would have the whole and united support of the southern states. 15

Other northern Democrats also assailed the anti-slavery positions of the Republicans – including Samuel Tilden (a New York state assemblyman and later the chair of the state Democrat Party, state governor, and then presidential candidate). Tilden affirmed that southern secession be could halted only if Republicans publicly abandoned their anti-slavery positions:

[T]he southern states will not by any possibility accept the avowed creed of the Republican Party as the permanent policy of the federative government as to slavery. . . . Nothing short of the recession [drawing back] of the Republican Party to the point of total and absolute non-action on the subject of slavery in the states and territories could enable it to reconcile to itself the people of the South. 16

Even the editorial page of the New York World endorsed the Democrats’ pro-slavery positions and condemned Republicans:

We cannot ask the South – we will not ask anybody – to live contentedly under a government . . . which burdens white men with oppressive debt and grinding taxation to try an unconstitutional experiment of giving freedom to Negroes. . . . A proposal for an abolition peace can never gain a hearing in the South. If the Abolition Party [Republicans] continues in power, the separation is final, [both] in feeling and in fact. 17

However, returning to an examination of southern secession documents, on January 19, 1861, Georgia became the fifth state to secede. Georgia then dispatched Henry Benning to Virginia to encourage its secession. At the Virginia convention, Benning explained to the delegates:

What was the reason that induced George to take the step of secession? That reason may be summed up in one single proposition: it was a conviction – a deep conviction on the part of Georgia – that a separation from the North was the only thing that could prevent the abolition of her slavery. This conviction was the main cause. 18

On January 26, 1861, Louisiana became the sixth state to secede. Days later, Texas was scheduled to hold its secession convention, and Louisiana sent Commissioner George Williamson to urge Texas to secede. Williamson told the Texas delegates:

Louisiana looks to the formation of a Southern Confederacy to preserve the blessings of African slavery. . . . Louisiana and Texas have the same language, laws, and institutions. . . . and they are both so deeply interested in African slavery that it may be said to be absolutely necessary to their existence and is the keystone to the arch of their prosperity. . . . The people of Louisiana would consider it a most fatal blow to African slavery if Texas either did not secede or, having seceded, should not join her destinies to theirs in a Southern Confederacy. . . . As a separate republic, Louisiana remembers too well the whisperings of European diplomacy for the abolition of slavery in the times of annexation [Great Britain abolished slavery in 1833; by 1843, southern statesmen were alleging – without evidence – that Great Britain was involved in a plot to abolish slavery in America. Southern voices therefore called for the immediate annexation of pro-slavery Texas into the United States in order to increase pro-slavery territory, but anti-slavery leaders in Congress – including John Quincy Adams and Daniel Webster – opposed that annexation. Their opposition was initially successful; and in his diary entry for June 10 & 17, 1844, John Quincy Adams enthused: “The vote in the United States Senate on the question of [admitting Texas] was, yeas, 16; nays, 35. I record this vote as a deliverance, I trust, by the special interposition of Almighty God. . . . The first shock of slave democracy is over. Moloch [a pagan god requiring human sacrifices] and Mammon [the god of riches] have sunk into momentary slumber. The Texas treason is blasted for the hour.” That victory, however, was only temporary; in 1845, Texas was eventually admitted as a slaveholding state.] not to be apprehensive of bolder demonstrations from the same quarter and the North in this country. The people of the slaveholding states are bound together by the same necessity and determination to preserve African slavery. The isolation of any one of them from the others would make her a theatre for abolition emissaries from the North and from Europe. Her existence would be one of constant peril to herself and of imminent danger to other neighboring slave-holding communities. . . . and taking it as the basis of our new government, we hope to form a slave-holding confederacy . . . 19

Williamson’s encouragement to the Texans turned out to be unnecessary, for on February 1, 1861, even before he arrived from Louisiana, Texas had already become the seventh state to secede. In its secession document, Texas announced:

[Texas] was received as a commonwealth, holding, maintaining, and protecting the institution known as Negro slavery – the servitude of the African to the white race within [Texas] – a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race and which her people intended should exist in all future time. Her institutions and geographical position established the strongest ties between her and other slaveholding states of the Confederacy. . . . In all the non-slave-holding states . . . the people have formed themselves into a great sectional party [i.e., the Republican Party] . . . based upon an unnatural feeling of hostility to these southern states and their beneficent and patriarchal system of African slavery, proclaiming the debasing doctrine of equality of all men irrespective of race or color – a doctrine at war with nature, in opposition to the experience of mankind, and in violation of the plainest revelations of divine law. They demand the abolition of Negro slavery throughout the Confederacy, the recognition of political equality between the white and Negro races, and avow their determination to press on their crusade against us so long as a Negro slave remains in these states. . . . By the secession of six of the slave-holding states, and the certainty that others will speedily do likewise, Texas has no alternative but to remain in an isolated connection with the North or unite her destinies with the South. 20

On April 17, 1861, Virginia became the eighth state to secede. It, too, acknowledged that the “oppression of the southern slave-holding states” (among which it numbered itself) had motivated its decision. 21

On May 8, 1861, Arkansas became the ninth state to join the Confederacy. Albert Pike (a prominent Arkansas newspaper owner and author of numerous legal works who became a Confederate general) explained why secession was unavoidable:

No concessions would now satisfy (and none ought now to satisfy) the South but such as would amount to a surrender of the distinctive principles by which the Republican Party coheres [exists], because none other or less would give the South peace and security. That Party would have to agree that in the view of the Constitution, slaves are property – that slavery might exist and should be legalized and protected in territory hereafter to be acquired to the southwest [e.g., New Mexico, Arizona, etc.], and that Negroes and mulattoes cannot be citizens of the United States nor vote at general elections in the states. . . . For that Party to make these concessions would simply be to commit suicide and therefore it is idle to expect from the North – so long as it [the Republican Party] rules there – a single concession of any value. 22

As Pike knew, the federal government under the Republicans was unwilling to abandon its anti-slavery positions; therefore the only recourse for the guarantee of continued slavery in Arkansas was secession – which Arkansas did.

Eventually, North Carolina and Tennessee became the tenth and eleventh states to secede, thus finishing the formation of the new nation that titled itself the Slave-Holding Confederate States of America. Southern secession documents indisputably affirm that the South’s desire to preserve slavery was the driving force in its secession and thus a primary cause of the Civil War.

2. The Declarations of Congressmen who left Congress to Join the Confederacy

Beginning on January 21, 1861, southern Democrats serving in Congress began resigning en masse to join the Confederacy. During this time, many stood in their respective federal legislative chambers and delivered their farewell statements unequivocally affirming what the secession documents clearly declared.

For example, Democrat U. S. Senator Alfred Iverson of Georgia bluntly told his peers:

I may safely say, however, that nothing will satisfy them [the seceded states] or bring them back short of a full and explicit recognition and guarantee of the safety of their institution of domestic slavery. 23

Democrat U. S. Senator Robert Toombs of Georgia (soon to become the Secretary of State for the Confederacy, and then a general in the Confederate Army) declared that the seceded South would return to the Union only if their pro-slavery demands were agreed to:

What do these Rebels demand? First, that the people of the United States shall have an equal right to emigrate and settle in the present or an future acquired territories with whatever property they may possess (including slaves). . . . The second proposition is that property in slaves shall be entitled to the same protection from the government of the United States, in all of its departments, everywhere, which the Constitution confers the power upon it to extend to any other property. . . . We demand in the next place . . . that a fugitive slave shall be surrendered under the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 without being entitled either to a writ of habeas corpus or trial by jury or other similar obstructions of legislation. . . . Slaves – black “people,” you say – are entitled to trial by jury. . . . You seek to outlaw $4,000,000,000 of property [slaves] of our people in the territories of the United States. Is not that a cause of war? . . . My distinguished friend from Mississippi [Mr. Jefferson Davis], another moderate gentleman like myself, proposed simply to get a recognition that we had the right to our own – that man could have property in man – and it met with the unanimous refusal even of the most moderate, Union-saving, compromising portion of the Republican party. . . . Mr. Lincoln thus accepts every cardinal principle of the Abolitionists; yet he ignorantly puts his authority for abolition upon the Declaration of Independence, which was never made any part of the public law of the United States. . . . Very well; you not only want to break down our constitutional rights – you not only want to upturn our social system – your people not only steal our slaves and make them freemen to vote against us – but you seek to bring an inferior race into a condition of equality, socially and politically, with our own people. 24 (emphasis added)

Democrat U. S. Senator Clement Clay of Alabama (soon to become a foreign diplomat for the Confederacy) also expounded the same points:

Not a decade, nor scarce a lustrum [five year period], has elapsed since [America’s] birth that has not been strongly marked by proofs of the growth and power of that anti-slavery spirit of the northern people which seeks the overthrow of that domestic institution [slavery] of the South, which is not only the chief source of her prosperity but the very basis of her social order and state polity. . . . No sentiment is more insulting or more hostile to our domestic tranquility, to our social order, and our social existence, than is contained in the declaration that our Negroes are entitled to liberty and equality with the white man. . . . To crown the climax of insult to our feelings and menace of our rights, this party nominated to the presidency a man who not only endorses the platform but promises in his zealous support of its principles to disregard the judgment of your courts [i.e., Lincoln had indicated that he would ignore the Supreme Court’s egregious Dred Scott decision], the obligations of your Constitution, and the requirements of his official oath, by approving any bill prohibiting slavery in the territories of the United States. 25

Democrat U. S. Senator John Slidell of Louisiana (soon to be a Confederate diplomat to France and Great Britain), echoed the same grievances:

We all consider the election of Mr. Lincoln, with his well-known antecedents and avowed [anti-slavery] principles and purposes . . . as conclusive evidence of the determined hostility of the Northern masses to our institutions. We believe that he conscientiously entertains the opinions which he has so often and so explicitly declared, and that having been elected on the [anti-slavery] issues thus presented, he will honestly endeavor to carry them into execution. While now [as a result of secession] we have no fears of servile insurrection [i.e. a slave revolt], even of a partial character, we know that his inauguration as President of the United States, with our assent, would have been considered by many of our slaves as the day of their emancipation. 26

Democrat U. S. House Representative William Yancey (who became a Confederate diplomat to Europe and then a Confederate Senator) similarly complained:

[The North is] united in pronouncing slavery a political and social evil. . . . There exists but one party that, either in spirit or sentiment, manifests any disposition to stand by the South and the Constitution, and that is the Democratic Party. . . . The institution of slavery. . . . exists for the benefit of the South and is its chief source of wealth and power; and now in the hour of its peril – assailed by the great Northern antagonistic force [the Republicans and abolitionists] – it must look to the South alone for protection. . . . The question then, naturally arises, what protection have we against the arbitrary course of the Northern majority? . . . The answer is . . . withdraw from it [i.e., secede]! 27

Perhaps the no-holds-barred pro-slavery position of Democrats and southern states was best summarized by Democrat U. S. Senator Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana (who became the first Attorney General of the Confederacy, then its Secretary of War, and finally its Secretary of State), who declared:

I never have admitted any power in Congress to prohibit slavery in the territories anywhere, upon any occasion, or at any time.28 (emphasis added)

Once the South seceded and organized its Confederate government, it immediately sought official diplomatic recognition from Great Britain and France, wrongly believing that by halting the export of Southern cotton into those nations they could strong-arm them into an official recognition of the Confederacy. But Great Britain and Europe already held large stores of cotton in reserve and also had access to textile imports from other nations, so the poorly conceived Confederate plan was unsuccessful.

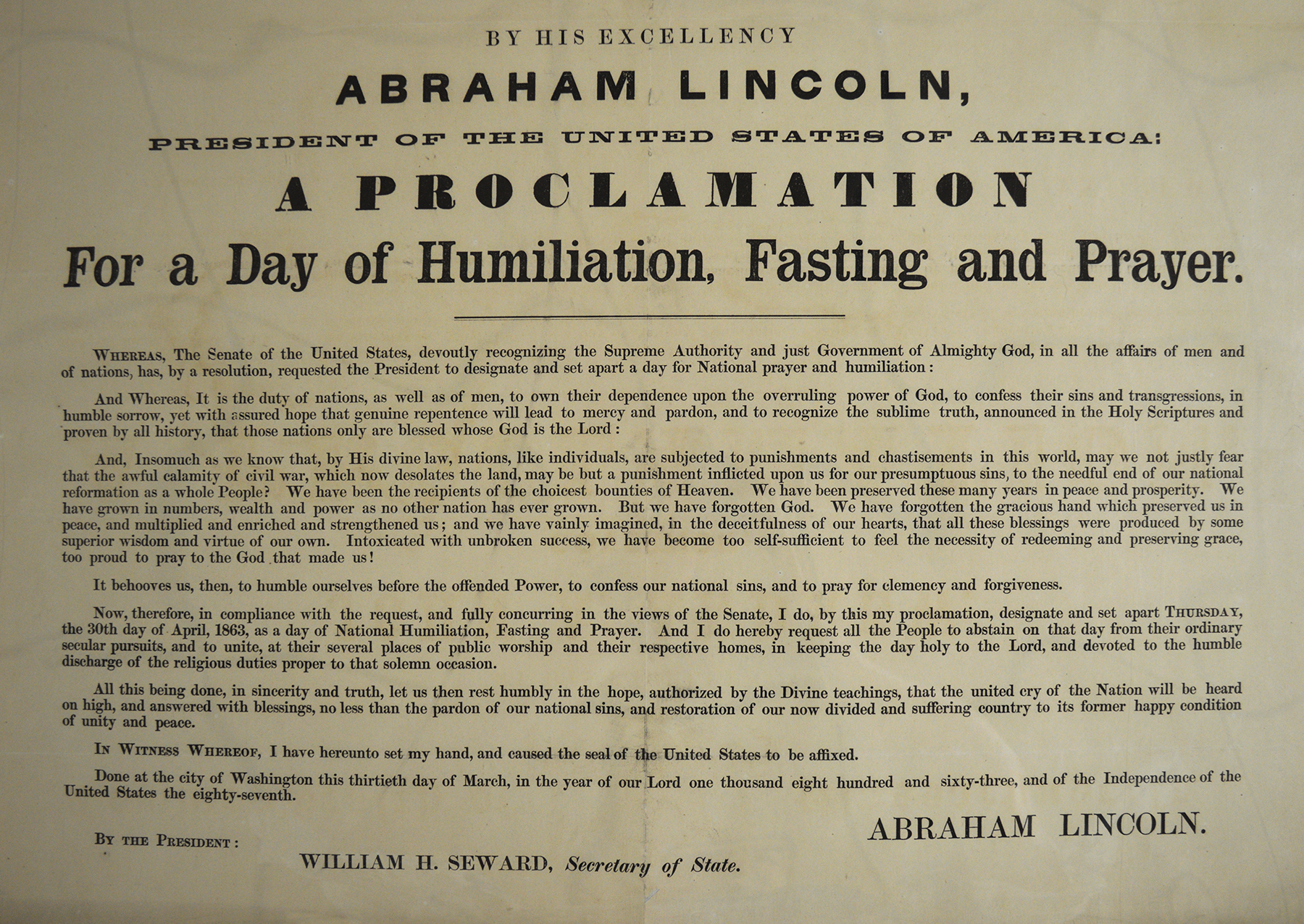

France had been willing to extend official recognition to the Confederacy but would not do so unless Great Britain did the same. But Charles Francis Adams (U. S. Minister to England, and the son of John Quincy Adams and grandson of John Adams) rallied anti-slavery forces in Europe and England to successfully lobby Great Britain not to extend official recognition to the Confederacy. Those early diplomatic successes by the Union were bolstered by President Lincoln’s 1862 announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves in the American states in rebellion – an act very popular among working-class Britons. By October 1863, the Confederacy, not having received the official support it so badly needed, expelled British representatives from southern states.

Although Great Britain never extended official recognition, she did indirectly assist the South in many ways, including supplying the Confederacy with naval cruisers that pillaged Union merchant shipping and also providing weapons to southern troops, including the Whitworth rifle (considered one of the most accurate rifles in the Civil War). A number of Britons even crossed the ocean to serve in the Confederate Army; and in some British ranks, the sympathy for the Confederacy was so strong that after popular Confederate General Stonewall Jackson was accidentally shot down by his own troops, the mourning was just as visible in parts of England as it had been throughout the Confederacy. Some in the British press even likened the death of Jackson to that of their own national hero, Lord Nelson; and a British monument to General Jackson was even commissioned, paid for, and transported to Richmond, Virginia by Confederate sympathizers in Great Britain.

Christian leaders in France – seeing Britain’s unofficial support for the slave-holding Confederacy – dispatched a fiery letter to British clergy, strongly urging them to oppose every British effort to help the Confederacy. As the French clergy explained:

No more revolting spectacle has ever been before the civilized world than a Confederacy – consisting mainly of Protestants – forming itself and demanding independence, in the nineteenth century of the Christian era, with a professed design of maintaining and propagating slavery. The triumph of such a cause would put back the progress of Christian civilization and of humanity a whole century. 29

Foreign observers clearly saw what southern Democrat U. S. Representatives and Senators in Congress had already announced: the Civil War was the result of the South’s desire to perpetuate slavery.

3. The Confederate Constitution

On February 9, 1861 (following the secession of the seventh state), the seceded states organized their new Confederate government, electing Jefferson Davis (a resigned Democrat U. S. Senator from Mississippi) as their national president and Alexander Stephens (a resigned Democrat U. S. Representative from Georgia) as their national vice-president. On March 11 (only a week after the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln as President [Confederate apologists not only claim that slavery was not the central issue to the Confederacy but they also frequently portray Abraham Lincoln as a dictator, tyrant, atheist, homosexual, incompetent, drunk, etc. To “prove” this view, they rely heavily on The Real Lincoln by Thomas Dilorenzo (2002), The Real Lincoln by Charles Minor (1901), and Herndon’s Lincoln by William H. Herndon (1888). These three books (and a few others) portray Lincoln in a negative light, but literally hundreds of other scholarly biographies written about Lincoln – including by Pulitzer Prize-winning historians such as Carl Sandburg, Ida Tarbell, Garry Wills, Merrill Peterson, Don Fehrenbacher, and others – reached an opposite conclusion.

A similar corollary would be to study the life of Jesus only by reading The DaVinci Code or The Last Temptation of Christ, or to study the life of George Washington only by using W. E. Woodward’s George Washington: The Image and the Man. In both cases, those writings present a view of that person but hundreds of other writings present an opposite and more accurate view; so, too, with Lincoln. The view of Lincoln presented by Confederate apologists is indeed a view, but it is contradicted by scores of other writers who, after examining all the historical evidence, reached an opposite conclusion.]), a constitution was adopted for the new confederacy of slave-holding states – a constitution that explicitly protected slavery in numerous clauses:

ARTICLE I, Section 9, (4) No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in Negro slaves shall be passed.

ARTICLE IV, Section 2, (1) The citizens of each state . . . shall have the right of transit and sojourn in any state of this Confederacy with their slaves and other property; and the right of property in said slaves shall not be thereby impaired.

ARTICLE IV, Section 2, (3) [A] slave or other person held to service or labor in any state or territory of the Confederate States under the laws thereof, escaping or lawfully carried into another, shall . . . be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such slave belongs.

ARTICLE IV, Section 3, (3) The Confederate States may acquire new territory. . . . In all such territory, the institution of Negro slavery as it now exists in the Confederate States shall be recognized and protected by Congress and by the Territorial government; and the inhabitants of the several Confederate States and Territories shall have the right to take to such Territory any slaves lawfully held by them in any of the States or Territories of the Confederate States. 30

Ironically, southern apologists claim that the Confederacy was formed to preserve “states’ rights,” yet the Confederacy expressly prohibited any state from exercising its own “state’s right” to end slavery. Clearly, the Confederacy’s real issue was the preservation of slavery at all costs – even to the point that it constitutionally forbade the abolition of slavery by any of its member states.

4. Declaration of Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens

On March 21, 1861 (less than two weeks after the Confederacy had formed its constitution), Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens delivered a policy speech setting forth the purpose of the new government. That speech was entitled “African Slavery: The Corner-Stone of the Southern Confederacy.” In it, Stephens first acknowledged that the Founding Fathers – even those from the South – had never intended for slavery to remain in America:

The prevailing ideas entertained by him [Thomas Jefferson] and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old Constitution were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature – that it was wrong in principle – socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that somehow or other, in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent [temporary] and pass away. 31

What did Vice-President Stephens and the new Confederate nation think about these anti-slavery ideas of the Founding Fathers?

Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. . . . and the idea of a government built upon it. . . . Our new government [the Confederate States of America] is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid – its cornerstone rests – upon the great truth that the Negro is not equal to the white man. That slavery – subordination to the superior [white] race – is his natural and moral condition. This – our new [Confederate] government – is the first in the history of the world based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth. 32 (emphasis added)

Notice that by the title (as well as the content) of his speech, Confederate Vice-President Stephens affirmed that slavery was the central issue distinguishing the Confederacy.

Were Economic Policies a Major Factor in Secession?

Many southern apologists assert that the primary cause of the Civil War was unjust economic policies imposed on the South by northerners in Congress, 33 but secession records refute that claim. In fact, of the eleven secession documents, only five mention economic issues – and each was in direct conjunction with slavery. For example:

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions; and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. 34 MISSISSIPPI

Texas [and] Louisiana . . . have large areas of fertile, uncultivated lands peculiarly adapted to slave labor; and they are both so deeply interested in African slavery that it may be said to be absolutely necessary to their existence and is the keystone to the arch of their prosperity. 35 LOUISIANA

They [the northern abolitionists in Congress] have impoverished the slave-holding states by unequal and partial legislation [attempting to abolish slavery], thereby enriching themselves by draining our substance. 36 TEXAS

We had shed our blood and paid our money for its [slavery’s] acquisition. . . . [But b]y their [the North’s] declared principles and policy they have outlawed $3,000,000,000 of our property [i.e., slaves] in the common territories of the Union. . . . To avoid these evils, we . . . will seek new safeguards for our liberty, equality, security, and tranquility [by forming the Confederacy]. 37 GEORGIA

We prefer, however, our system of industry . . . by which starvation is unknown and abundance crowns the land – by which order is preserved by an unpaid police and many fertile regions of the world where the white man cannot labor are brought into usefulness by the labor of the African, and the whole world is blessed by our productions. 38 SOUTH CAROLINA

Clearly, even the economic reasons set forth by the South as causes for secession were directly related to slavery. Therefore, to claim that economic policies and not slavery was the cause of the Civil War is to make a distinction where there is no difference.

Summary

Numerous categories of official Confederate documents affirm that slavery was indeed the primary issue that drove the secession movement and was central to the rebellion; it is therefore blatant and unmitigated revisionism to assert – as do Confederate apologists – that “one of the most important” of the “truths of history” is “that the War Between the States was not a rebellion nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery.” 39

[Many southerners ardently insist on describing the conflict as “The War Between the States” and strenuously object to use of the descriptor “Civil War” (see, for example, “Let’s Say ‘War Between The States’ “ (at: https://www.civilwarpoetry.org/FAQ/wbts.html)). However, cursory examinations of dozens of Confederate documents, as well as histories of the war written by Confederates immediately following the conflict, demonstrate that the descriptor they themselves most frequently used was “Civil War.” (Other descriptors used much less often by southern authors include “War Between the States,” “War of Southern Secession,” and “War for Southern Independence.”) Therefore, the assertion that the term “Civil War” is an inaccurate or biased title for the conflict is refuted by an examination of Confederate soldiers and historians who lived at the time of that conflict. While the question of whether the conflict constituted a “rebellion” was not addressed by this work, a simple query raises a significant implication: If the “war between the states” was not a “rebellion” (as modern southern apologists assert), then why did southern leaders during the Civil War describe themselves and other southern participants as “Rebels” – a derivate of the word “rebellion”? The simple descriptor “Rebels” used by the Confederates themselves certainly suggests that they certainly viewed the Civil War as a “Rebellion.”]

Endnotes

1.The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, © 2004, by Houghton Mifflin Company.

2. “Derby, Kansas Middle School Suspension Denounced by Sons of Confederate Veterans,” Sons of Confederate Veterans which declares “[T]he War Between the States was fought over issues such as the rights of individual states to set their own tariffs, establish their own governments, and receive full profit from their agricultural production. . . . the question of slavery was brought into the war by Lincoln in late 1862 as an emotional one to bolster the sagging Northern war effort . . .”; and “Children of the Confederacy: Creed,” United Daughters of the Confederacy which declares “We, therefore pledge ourselves . . . to study and teach the truths of history (one of the most important of which is, that the War Between the States was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery)”; etc.

3.Edward McPherson, The Political History of the United States of America During the Great Rebellion (Washington: Philip & Solomons, 1865), 15-16, “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union,” December 24, 1860.

4.Convention of South Carolina, “Address of South Carolina to Slaveholding States,” Teaching American History, December 25, 1860.

5. “A Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union, January 9, 1861.”

6. Addresses Delivered Before the Virginia State Convention, February 1861 (Richmond: Wyatt M. Elliott, 1861), “Address of Hon. Fulton Anderson, of Mississippi,” 7.

7. Orville Victor, The History, Civil, Political and Military, of the Southern Rebellion (New York: James D. Torrey, 1861), 1:194, Florida, “Preliminary Resolution Prior to Secession,” January 7, 1861.

8. Victor, The History (1861) 1:195, “An Ordinance to dissolve the union between the State of Alabama and the other States united under the compact styled ‘The Constitution of the United States of America,’” January 11, 1861.

9. “A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Georgia to Secede from the Federal Union, January 29, 1861.”

10. Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U. S. 393, at 449-52 (1856). The Dred Scott decision is arguably the first example of judicial activism by the Supreme Court: it struck down the congressional law of 1820 prohibiting the extension of slavery into certain federal territories.

11. Thomas Hudson McKee, The National Conventions and Platforms of All Political Parties, 1789-1905 (New York: Burt Franklin, 1906), 98, Republican Platform of 1856.

12. See, for example, the Democrat Platform following the Dred Scott decision; not only was there no condemnation of decision, but the platform instead declared: “The Democrat Party will abide by the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States upon these questions of constitutional law.” McKee, Platforms, 108.

13. See, for example, the Democrat Platform of 1856 declaring: “That Congress has no power under the Constitution, to interfere with or control the domestic institutions of the several States. . . . [And] the Democratic party will resist all attempts at renewing, in Congress or out of it, the agitation of the slavery question under whatever shape or color the attempt may be made. . . . [T]he only sound and safe solution of the ‘slavery question.’ . . . [is] non-interference by Congress with slavery in state and territory, or in the District of Columbia.” McKee, Platforms, 91-92.

14. See, for example, the Democrat Platform of 1856 declaring: “All efforts of the abolitionists, or others, made to induce Congress to interfere with questions of slavery, or to take incipient steps in relation thereto, are calculated to lead to the most alarming and dangerous consequences; and that all such efforts have an inevitable tendency to diminish the happiness of the people and endanger the stability and permanency of the Union.” McKee, Platforms, 91.

15. “Civil War Era: Mayor Wood’s Recommendation of the Secession of New York City,” TeachingAmericanHistory.org, January 6, 1861.

16. The Union! It’s Dangers! And How they can be Averted. Letters from Samuel J. Tilden to Hon. William Kent (New York: 1860), 14-15.

17. William P. Rogers, The Three Secession Movements in the United States (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1876), 16-17, quoting an editorial in the New York World, September 1, 1864, “The Democratic Platform.”

18. Addresses Delivered Before the Virginia State Convention, February 1861 (Richmond: Wyatt M. Elliott, 1861), “Address of Hon. Henry L. Benning, of Georgia,” 21.

19. Journal of the Secession Convention of Texas, ed. E. W. Winkler (Austin Printing Company, 1912), 122-123, address of George Williamson, Commissioner from Louisiana, February 11, 1861.

20. “A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union, February 2, 1861.”

21. “An Ordinance to repeal the ratification of the Constitution of the United State of America by the State of Virginia, April 17, 1861.”

22. Southern Pamphlets on Secession, November 1860 – April 1861, ed. Jon Wakelyn (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 334, 338, “State or Province? Bond or Free?” by Albert Pike, March 4, 1861.

23. Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 2nd Session (Washington: Congressional Globe Office, 1861), 589, January 28, 1861; Thomas Ricaud Martin, The Great Parliamentary Battle and the Farewell Addresses of Southern Senators on the Eve of the Civil War (New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Co., 1905), 214, farewell speech of Alfred Iverson, January 28, 1861.

24. Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 2nd Session (1861), 268-270, January 7, 1861; Martin, The Great Parliamentary Battle (1905), 148-152, 167, 169, 170-171, 172, farewell speech of Robert Toombs, January 7, 1861.

25. Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 2nd Session (1861), 486, January 21, 1861; Martin, The Great Parliamentary Battle (1905), 202, 204, farewell speech of Clement Clay, January 21, 1861.

26. Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 2nd Session (1861), 721, February 4, 1861; Martin, The Great Parliamentary Battle (1905), 222-223, farewell speech of John Slidell, February 4, 1861.

27. The Secession Crisis, 1860-1861, ed. P. J. Staudenraus (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1963), 16-18, speech of William Yancey, delivered at Columbus, Georgia, in 1855.

28. Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 2nd Session (1861), p. 238, January 3, 1861; Martin, The Great Parliamentary Battle (1905), 222-223, speech of Judah P. Benjamin, January 3, 1861.

29. William J. Jackman, History of the American Nation (Chicago: K Gaynor, 1911), 4:1124.

30. “Constitution of the Confederate States; March 11, 1861,” Avalon Project; Edward McPherson, The Political History of the United States of America During the Great Rebellion (Washington: Philip & Solomons, 1865), 98-99.

31. Echoes From The South (New York: E. B. Treat & Co., 1866), 85; The Pulpit and Rostrum: Sermons, Orations, Popular Lectures, &c. (New York: E. D. Barker, 1862), 69-70, “African Slavery, the Cornerstone of the Southern Confederacy,” by Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy.

32. Echoes From The South (1866), 85-86; The Pulpit and Rostrum (1862), 69-70, “African Slavery, the Cornerstone of the Southern Confederacy,” by Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy.

33. Mike Scruggs, “Understanding the Causes of the Uncivil War,” Georgia Heritage Council, June 4, 2005; Charles Oliver, “Southern Nationalism – United States Civil War,” Reason, August, 2001, where he is talking about Charles Adams viewing “the Civil War as a fight about taxes, specifically tariffs.”

34. “A Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union,” January 9, 1861.

35. Journal of the Secession Convention of Texas, ed. E. W. Winkler (Austin Printing Company, 1912),122-123, address of George Williamson, Commissioner from Louisiana, February 11, 1861.

36. “A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union, February 2, 1861.”

37. “Georgia Declaration of Secession,” January 29, 1861.

38. Edward McPherson, The Political History of the United States of America During the Great Rebellion (Washington: Philip & Solomons, 1865), 15, “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union,” December 24, 1860.

39. Plaque from the Children of the Confederacy hanging inside the Texas State Capitol. See also “Children of the Confederacy: Creed,” United Daughters of the Confederacy.