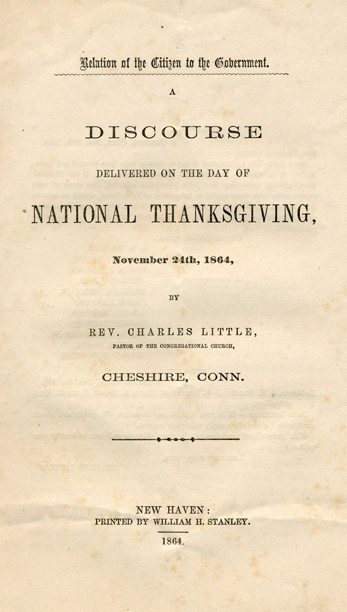

A sermon preached by Reverend Charles Little on the day of a National Thanksgiving. Rev. Little uses Titus 3:1 as the basis for his sermon.

A

Discourse

Delivered on the Day of

National Thanksgiving,

November 24th, 1864.

By

Rev. Charles Little

Pastor of the Congregational Church,

Cheshire, Conn.

“Put them in mind to be subject to principalities and powers, to obey magistrates, to be ready to every good work.” Titus iii, 1.

The subject which I present to you today, is one authorized by the text and demanded by the times. It is the relation of the citizen to the government. Civil government, like the family and the church, is a Divine institution. Ordained of God, whosoever resisteth it, reisteth the ordinance of God.

If any think that an apology is needed for the discussion of this subject in the pulpit, they will find one in its gospel associations. Paul made no mistake when he linked this subject with some of the grandest truths of God’s word. If an inspired Apostle thought it worthy to be classed with such topics—as free grace, the love of God, regeneration, justification, the Saint’s blessed hope, the coming of Christ to judge the world, and the inheritance of life eternal; if he, when commissioning Titus to ordain elders and perfect the churches, commanded him to instruct the converts on their duties to the government, who can claim that pastors are forbidden to speak of these things to their people from the pulpit?

Two preliminary inquiries demand our attention: What is the life of a nation? We hear it said—“The life of the nation is in danger”—“the nation is decaying.” What is meant?

The life of a nation is something more than the aggregate, or united, or concentrated life of its people. It is that which gives it vitality, which secures growth and greatness. It consists, if I mistake not, of three different elements combined and assimilated into that one mysterious principle, which we call life.

The first is found in its civil institutions, its constitution, laws, and the modes of their administration.

The second is in its physical resources, embracing climate, soil, minerals, facilities for manufactures and trade, and perfection of the mechanic arts.

The third is in the industry, intelligence and virtue of its people.

The nation which has the largest share of these in their greatest perfection, will enjoy the most vigorous and the longest life. Its influence will predominate in the counsels of the nations.

What is government? It is that form of fundamental rules and regulations by which a nation is governed, which are embodied in its constitution and laws, written and unwritten. This is the true meaning, though in common language, the right to govern, and the person or persons governing are called the government.

What, for example, is the government of these United States? Is it the President and his cabinet? Is it the congress? Is it the judiciary? Or is it all these combined? Neither. The Constitution of the United States and the laws made in conformity therewith constitute the government of this country. For the administering of this government, legislative power is vested in the congress, judicial power in the courts, and executive power in the President. This government was made by the people and for the people. This is evident from the Preamble to the Constitution:

“We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, * * * * and secure the blessings of liberty for ourselves and our children, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States.”

This government is also supreme. In the sixth article you will find these words:

“This Constitution and the laws of the United States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof, and all treaties made, or which shall be made under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land, and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.”

Thus, in imperishable letters engraven on the foundation of our government, are recorded the important truths that—it was framed by the people of the whole country, not by the separate States, and that is supreme over all—a true sovereignty, not a collection of sovereignties.

Do we not see here, standing out in bold relief, the fallacy of the much vaunted doctrine of State rights—the doctrine that each state may secede at pleasure?

Though the people reserved to their respective State governments all rights not specified in the Constitution, did they not explicitly say that that should be supreme? But if the general government is supreme, what are the others but subordinate.

The dogma that each State may secede at pleasure, if true, would destroy our government superstructure and foundation. Our constitution and laws would be as worthless as the waste and sand thrown up by the ocean in a storm.

What now is the relation of the citizen to the government; a citizen of our country to our general government?

This is three-fold. First.—He is an elector, charged with the high duty of giving his suffrage for those who are to make or to execute the laws. The distinguishing feature and crowning glory of a republican government is the right of suffrage, the proper use of which, in this country, will solve the problem whether such a government can be permanent.

If, as we believe, a republican form of government will most effectually secure the good of the people, and will the soonest elevate the nations to the highest civilization; if, as we are assured, the oppressed of the world are now looking to the success of our government as their chief hope, and if the failure of free institutions here will roll back the sun of liberty beneath the horizon, and give to decaying despotisms a new lease of life for centuries to come, is it not evident that the right of suffrage involves momentous responsibilities?

The citizen who violating his solemn oath to vote for those men whose election he believes will be for the best good of the nation, gives his suffrage for men whom he knows to be unworthy, is he not largely guilty of the curse which such rulers bring upon the land? And does the citizen who refuses to vote, escape his responsibility or materially lessen his guilt?

Every elector is bound to study and understand, as far as him lies, the nature of our government, and the principles which will best sub serve its high ends—he is bound, so far as possible, to qualify himself for the selection of suitable men for office. Especially is he under obligation to acquire that virtue which will lift him above bribery, fraud, and every dishonorable motive. And the fact that many unworthy men have received this inestimable privilege, increases the obligation of every true citizen to use his right more intelligently and conscientiously.

Again, the citizen is a subject bound to obey the laws. The laws made according to the collective will of the electors are obligatory upon all alike.

The obligation to obedience is two-fold. It exists in the nature of things. A nation cannot live without government, and government cannot continue without obedience. Without this there will be speedy anarchy and ruin.

This obligation arises also from the will of God. He commands obedience. Government is His institution; rulers are his ministers; obedience to them He regards as to Himself.

Therefore, every citizen is bound to obey the laws. The only exception is when a person believes that compliance with a particular requisition will violate his conscience. He may then disobey, but must submit to the penalty. It has also been held that when the laws become cruelly oppressive, and there is no remedy, if a majority of the people believe that success is probable, they may unite in resisting the laws.

Happily, under our constitution there is a peaceable remedy for all oppressive laws and therefore, a justifiable revolution in this country is hardly within the limits of possibility.

Once more the citizen is eligible to office. Hence, it is the duty of each elector, so far as his opportunities will allow, to qualify himself for office, and when this is tendered to accept, unless other duties prevent. True loyalty and patriotism require some persons to make sacrifices in this service of their country. Whoever accepts an office, high or low, should remember that he is the minister of God, that he is to labor in it with fidelity, seeking, alike, the glory of God, the safety of the government, and the welfare of the people.

Besides the peculiar obligations which spring from these three special relations of the citizen to the government, there are others more general, yet too important to be overlooked.

By a decree of the ancient Roman Senate, the Consuls were commanded to see that the republic received no detriment. This duty is now laid upon every American citizen. Providence, philanthropy and true self-interest, make each elector a conservator and defender of our country. Each one is bound to aid in the enforcement of the laws, for laws unexecuted are a source of weakness and of danger. Personal obedience is not enough, we must do what we can to secure the obedience of others. We are bound therefore, to labor for the extension of right principles, for the creation and sustaining of a public sentiment, which will frown down all violations of law, which will demand and ensure the punishment of criminals of every grade. Each elector is also obliged to give his effective influence against all practices which tend to increase ignorance and vice, and for every institution which will promote knowledge and virtue.

These duties, comprehensive and important, follow necessarily form the text and other scriptures, and are as binding upon us as any Divine precept.

In view of the truths thus set forth, in view of the probable future of our country, the glorious possibilities before it, are we not constrained to acknowledge that, in this land, citizenship with the elective franchise is one of the highest earthly distinctions, and when worthily worn, is more honorable than the monarch’s crown?

A prophet’s vision only could picture that future.

Its possibilities appall us. Seven hundred millions of people might dwell here and not equal in proportion the population of Great Britain and Ireland.

Its probabilities oppress us. We expect that there hundred millions will by and by reap the results of this war, in the enjoyment of earth’s richest treasures.

Its certainties surpass belief. One hundred millions are soon to bless God for a home in this land. And then with every material resource developed, every mental gift employed, a government, free and perfect, and these all sanctified; this nation shall be the power and glory of the world; the white robed angel of peace shall continually hove above and guard this land, while rays of light and life shall spread over the earth, hastening the true millennium of the ages.

My subject furnishes some important practical inferences. It affords a triumphant justification of those who have supported the government in this war. It has been thought strange that good men, and especially the ministers of Christ, should be so strenuously earnest in advocating the putting down of this rebellion by force of arms.

In view of the truths presented above, the answer is obvious. Good citizenship required this, good citizenship made this a religious duty. The nation must attempt to conquer the rebellion or give up its life. If, without a struggle, it had permitted one third of its subjects to revolt, and take with them its ships, forts and arsenals, what prestige or power would have remained? It was, undoubtedly, incumbent on those who administered the government to conquer the rebellion, if possible. What other course was open? Negotiations? Who negotiates with armed traitors? Arbitration? When a burglar opens your safe and takes your valuables, do you leave it to referees to decide what part he shall restore? What trust could we have placed in those who had violated their oaths of allegiance? Would they have abided by any arbitrament, if opposed to their wishes?

Again—could we not have granted the traitors all which they wished, and so have allowed them to remain? There was no desire on the part of the leaders to remain, they sought occasion to rebel. No terms would have kept them in the Union except those which would have made the mass of Northern freeman the subjects of a Southern oligarchy.

But you might have let the seceding States go in peace. Yes! And then, where would have been the oath of the President, who had solemnly sworn to “faithfully execute the office of President of the United States,” and to the best of his ability, to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States?” Where would have been the oaths of office holders and electors, those oaths by which they all had sworn to be faithful to the Constitution, that Constitution which declares—that it and the laws made in pursuance thereof, shall be the supreme law of the land, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State, to the contrary notwithstanding? These solemn oaths would have been, where? Broken, violated, trodden in the dust. And then the guilty violators, office holders, electors, all, would they not have stood forth before the world, their fair fame blackened and disgraced, their meanness despised of men, and abhorred of God, themselves worthy of the infamy which would have immortalized their names? Would not the very statutes and portraits in our national halls have blushed for shame?

Let the seceding States go in peace, and you destroy the government; for then other States may separate when they shall please. Let Oregon and California request it, the Western Empire rises upon the shores of the mighty Pacific. Let the ingathering crowds of hardy adventures demand it, the Rocky Mountain Empire exists, the Switzerland of America, rich beyond estimate, in mines of gold and silver. Let the dwellers in the great valley wish it, the Mississippi Empire, with its teeming multitudes will claim supremacy over the continent. Let the Middle States agree, the Central Empire is before you bidding for the trade of the world. Where then will be the Union, where the boasted government of our Fathers—the glory of the people and the fear of despots? Where?

New England will indeed remain, the last to abandon, as she was the first to inaugurate the ancient honored Republic. New England will remain intact in her resources of granite and ice, safe in the knowledge and virtue of her people. She will remain with a record honorable above others, marred only by the memory of a few degenerate sons who would not sacrifice themselves to save their country. She will remain with a future, noble, prosperous and worthy of her origin and her history.

Let the seceding States go, and you invite anarchy and despotism to run riot in our hitherto happy land. Think you that these various empires can be established, consolidated and perfected in peace? Will there be no sub-secessions, no counter rebellion, no disputes respecting boundaries, extradition treaties, division of public property, duties on exports and imports? Will these questions be settled peacefully? As well might you expect that the planets, broken loose from their central sun, and whirling uncontrolled through space, would find their way back in safety to their former orbits.

No! Let the general government be destroyed, and in the view of right reason, there will be wars on this continent, of which the present is but a dim shadow. There will be long years red with human blood and gore, before the angel of peace shall again spread her blessed wings over the land. With such facts and probabilities before them, how could religious, thoughtful, loyal men, refrain from giving their influence for the speedy and utter destruction of the rebellion?

Did not their cheeks blanch and their hearts beat wildly while they beheld the vials of Jehovah’s wrath pouring their dread contents upon the guilty land, filling it with these gory battle fields, these groaning hospitals, these shrouded homes and crushed hearts? At such a sight could they remain unmoved? Could they fail to pray for the shortened time, for speedy peace? Having prayed, must they not work?

Moses prayed, but deliverance came not till “he stretched his hand over the sea.” So these true men have prayed and labored till now the nation is walking on dry land, through waters which soon are to whelm the rebel leaders in remediless ruin.

Another inference from my subject, and following necessarily from the last, is this:

It is now the duty of every citizen to use his utmost exertions in sustaining the government and in aiding the administration to subdue the rebellion. Obedience to God requires this, for He commands you to be subject to principalities and powers, to obey magistrates, and to be ready for every good work.

Fulfillment of oaths requires this: Is that man true to his oath, is he faithful to the Constitution, who, when he sees the Constitution violated, and the beautiful flag, emblem of its power, shot down with rebel bullets, sits in silence, caring not and rebuking not the traitor? Justice to a large portion of the Southern people demand this. They did not vote for secession, they did not wish it. They do not today enjoy that which the General Government is bound to secure to every State, a republican form of government. The safety of your children demands this. Let the Government be destroyed and where is you assurance that they will pass safely through scenes of anarchy and blood?

Once more, the welfare of the world demands this. Without doubt, the existence on this territory of on united, free, powerful Republic, firmly grounded in the knowledge and virtue of the whole people, would be the hope, the joy of the oppressed everywhere. This nation would then become the beacon light of the world, before whose brightness the chains of the oppressed, and the sword of the oppressor would disappear.

Under the pressure of these motives, Divine and human, personal and philanthropic, can we hesitate to labor with our might for the entire subjugation of the rebels, which is the only practicable way for the speedy return of peace. And when peace shall come with healing in her wings, by the blessing of God, no more to depart; when peace shall come, filling the expanding hearts of the people with intensest joy, holding in store blessings, unmeasurable and invaluable for the hundred millions yet to dwell on the mountains, in the valleys, and by the shores of this one blessed land, will it not add infinitely to your satisfaction, if you can then feel that, in the hour of her peril, you were faithful to your country, and to you God?

This subject, my friends, sheds a brilliant light upon the grounds of our Thanksgiving, today.

Where are we? On the road to ultimate victory—past the middle mile-stone—within sight of the enemies’ capital—within hearing of their despairing groans.

What have we escaped? The wreck of our Government, the ruin of our nation, the reproach of the world.

What have we saved? Our country’s honor, our self-respect, our power and place among the nations.

What are our hopes? Bright, beautiful as the rainbow tints. Beyond the dark dread path which now we tread, we discern the open plain. Beyond the tide of blood which yet for a time must flow, beyond the burden of debt which, for a little while, must still increase, we behold the early dawn which heralds the rising sun of peace. Even now we seem to see his beams, gilding with gold and purple, the upper edges of the black sulphureous clouds which obscure our lower vision.

There is confidence in the cabinet, confidence in the army, confidence in the hearts of the people.

What are our hopes? They are strong, they energize, they prolong endurance, they produce strength, they give power.

What are our hopes? They are firm in the wisdom of our officers, civil and military, firm in the strong arms and hearts of our patriotic soldiers and sailors, firm in the unswerving loyalty of the mass of the people. They strengthen, as we listen to the echoes of our booming cannon, from sea and land, and to the resounding triumph of our victorious legions.

Our hopes? They are sure because grounded in the justice of a sacred cause, a cause the tidings of whose success shall vibrate over the world and along the coming centuries, thrilling millions of hearts with purest joy.

Our hopes? They are unfailing because sustained by the marked interpositions of an Almighty God, who judgeth among the nations, and who hath proclaimed liberty unto the people.

A few more heavy blows and the double-monster, slavery and secession, dies; a few more months of labor, and rest will come; the woes of war endured a little longer, and peace shall return, a peace, peace-inspiring and permanent, a peace which shall soothe the weeping mourner, nerve the maimed sufferer, free the last slave, and thrill the souls of all.

Is there not in these things reason for devout thanksgiving to Almighty God? Add to these our other blessings—health and fruitful seasons, domestic joys and social happiness, educational facilities and literary privileges; churches, Sabbaths, communion of saints, the mercy seat and hopes of heaven; is there not cause, is there not motive for thanksgiving, such as were never ours before?

How should this day be kept? With praise and prayer, with joy and gladness, with the gathering of households, and the renewal of friendships, with the enjoyment of Providential bounties and gifts to the destitute, with the remembrance of God’s mercies, and the worship of His holy name.

Once in ancient time a nation delivered kept holy day, with timbrels and dances, and with a memorable, memorial song. In a coming eternity, hosts redeemed shall sing that song, and the song of the Lamb, in Eternal Thanksgiving.

Here today, midway between the two, we, a nation richly blessed by the God who delivered them, we, in memory and hope, offer up the tribute of our rejoicing hearts.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!