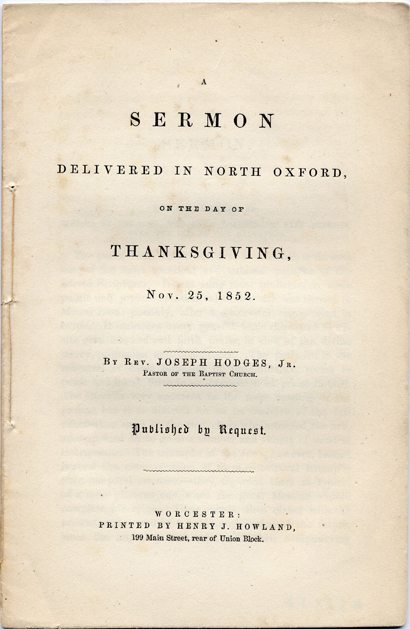

A sermon preached on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, 1852, by Reverend Joseph Hodges, Jr. in North Oxford.

Sermon

Delivered in North Oxford,

On the day of

Thanksgiving,

Nov. 25, 1852.

By Rev. Joseph Hodges Jr.

Pastor of the Baptist Church.

Sermon

Psalm LXVIII [68]:19.

Blessed be the Lord, who daily loadeth us with benefits, even the God of our Salvation.

The psalm from which our text is selected, is deemed one of the most excellent and sublime portions of the Sacred Scriptures. It was sung, most probably, on some public and joyous occasion, when the ark was carried to Mount Zion: possibly, after a successful engagement in battle. It embraces every general topic calculated to excite gratitude and call forth praise, in view of the divine mercy, protection and beneficence. The psalmist, in the rehearsal of these blessing of remembrance, seems to pause and break forth in an expression of praise to God. The effect is very apparent in the mere reading of the psalm; but it is difficult for us to conceive of the full effect when sung by the vast choir who attended the ark, accompanied by so great a number and variety of musical instruments. The triumphs of the Jews, however, looked beyond the mere occasion of them, – temporal triumphs over temporal enemies, — they regarded them as typical of a more glorious one, when the great Messiah should complete his reign. Their minds, thus elated with the present, and moved by a fervid anticipation of the future, amid the imposing multitude, with their overpowering music, must have been excited by a spectacle at once touching to the heart, inspiring to the imagination, and lasting in its associations.

It is indeed, in a manner less imposing, that we are called upon to offer our tribute of praise and thanksgiving. Amid the current of life, our usual duties and avocations, the routine of common events and obligation, it is appropriate for us to pause, and at this season of our annual festival, lift up our humble voice in praise to our usual fruitful harvest, and to engage in other worthy pursuits and enterprises, the results of which furnish evidence of general prosperity. Every useful undertaking has been sustained. Though sin and trouble, losses and accidents, sickness and death, are the usual lot of some, from which none are entirely exempt, amid it all there has been the good hand of a wise Governor and Benefactor to guide, to deal out the blessings of life, and to overrule all events of prosperity or adversity, for the happiness of all.

It would be appropriate to recount the many favors of heaven, to specify the instances of mercy and goodness common to us as individuals or a community. There might be drawn out a long catalogue of benefits, with which the good Providence of God has loaded us, and each so presented, as to excite afresh in our breast delightful emotions of gratitude. These benefits would not be unlike those, which have often, almost annually occurred. God, in his Providence, as you are aware, gives, withholds, and controls, so as not only to affect the mind and heart with a sense of the blessings bestowed, to produce the feeling of gladness; but to stimulate withal a sense of obligation in respect to enterprise and activity. We feel bound not only to laud our great Benefactor, but we are moved by our gratitude to adopt and carry out plans of serving him which shall result in the good of the world and to His honor.

If therefore, instead of recounting these benefits, I refer you to the enterprises and improvements which have grown out of these favors, and which are calculated to stimulate us to greater exertions, to engage in more elevated employments, I may accomplish quite as good a service.

In prosecution of the object which I have suggested, time will allow me only to glance at some of the improvements in agriculture and manufactures, with which we are more intimately connected, and refer to the condition of education amongst us, as associated with the various branches of industry.

Agriculture I may name as a science, as well as an art, of the first importance. Some may be disposed to smile because this employment is spoken of as science. As it has been too often conducted, or neglected, it may seem to be the business of the most limited capacities of the most ordinary calculators, for those alone who can perform drudgery. Too often we fear that this sentiment has been taken for granted by farmers themselves, and hence they have plodded on, too much in the same old track. Hence the rest of the world is in advance of them, and their sons frequently leave them to follow less honorable callings. It is however at the foundation of all other employments, and no less dignified, healthy, or profitable. Its study and practice will serve to develop improvements, resources, strength, and health, as much certainly as any other. A glance at the earlier ages of the world will afford us some idea of the improvements which have taken place. If we may use Jahn as authority; and I know of no better, we must conclude that the implements first employed for husbandry were of the rudest construction, and so continued to be with comparatively little change for ages. Instead of shovels and spades, only sharpened sticks and flattened pieces of wood were used. The plow was made of a bent bough sharpened at one end, requiring the greatest strength and attention to hold it. The harrow was nothing more than a cluster of limbs of trees, thrown together so as to scratch the soil, tear apart the clods, and level somewhat the earth. Every other farming implement was of the same rude character. To perceive the improvements in this branch of business, we need not go further back than our own boyhood. Compare the implements then in use with those now, both as to form and adaptation, and we are struck with the change. Hence the ease and rapidity with which we prepare the land, sow the seed, and reap the harvest. And many are the improvements for gathering fruits and grain, mowing and raking, pulling up stumps by their roots, sinking rock, ditching meadows, irrigating hills, and converting marshes into arable fields. Science has taught us how resuscitate worn-out lands and to make the rich richer. No man who has land paid for, a house to live in, and information which may be gained in our common schools, with a good paper on farming, with health and energy, need be destitute. As much, however, depends on the head as the hands, yea more. There are needed, activity, investigation, perseverance and economy. And on this festival day, when so much of the farmer’s care and productions are brought to our board, in token of our thankfulness we are bound to understand and carry out in the world the improvements which, under a kind Providence, have been developed. Nor should we stop with the present. We should not live without leaving our mark somewhere, in and on our age; such as shall call forth the gratitude of another generation for what we have done; such as shall stimulate that generation to do more, and become wiser, than the former. Thus from generation to generation, the capabilities for the production of fruits shall abundantly manifest that agriculture is in no respect inferior to any other employment in dignity, usefulness, tastes, or health.

It would be interesting to trace the history of improvements in manufactures from the earliest times to the present. We are struck with the improvements in the structure of machinery, and the architecture of the mills within the last twenty-five years. This is true of all manufactories. We have specimens of art in the manufacture of cloth in ancient times, that would compete with those of modern, possibly in beauty, texture, and durability. But the long process and great labor mad these fabric expensive and rare. None but kings and princes could afford to be clothed in soft raiment and embroidered garments. Formerly cotton was deemed the richest and most costly fabric, now the commonest and cheapest. Under what inconveniences too, in the earlier days was cloth woven and garments fabricated? The Israelites had learned the art among the Egyptians and became their superiors. They were the New Englanders among the Southerners. On their tedious return to Palestine, they wove curtains for the tabernacle rich and beautiful. There was work performed under difficulties which, even in this day, in patient, persevering New England, might be deemed insurmountable. Scarcely less astonished should we be, to view the improved facilities with which we are now favored, compared with the disadvantages under which manufactories were commenced in our county. These very disadvantages were such, however, as to give stimulus to every generous enterprise.

May I not be permitted here to refer to the advantages growing out of our manufactories? That there are evils connected with them, we may not deny. The same may be said of every other enterprise under the sun, and it will be so, so long as human nature remains what it is, under the direction and restraints of similar impulses and influences. The evils are not necessarily of the business, but rather of the nature of the men who conduct and perform it. As the world advances there must necessarily be division of labor. Some may sigh for the time to return when in every family there shall be the loom, the spinning wheel, the shoe bench, the carpenter’s bench, the anvil, the chair-maker, the basket-maker, the broom-maker, the tailor, the dress-maker, as well as the farmer and dairy. And what manufacturers they were! Now as good and honest as those times were, who would roll back the world upon them? Now manufacture, commerce, agriculture, and all other honest employments or professions, help each other. What farmer would get twenty-five or thirty cents per pound for his butter in the country, such a season as this even, were all agriculturists who spun and wove their own cloth, and made their own garments and shoes? I do not speak as a partisan. Not at all. There have been in days gone by, honest differences as to the adoption of various measures in respect to political economy. There may be now. But the trouble was then, and now is, I divine, there was and is needed the light which comes from intercommunication of a practical character- a better understanding, not of theories, but of the working of them. When this light and understanding shall prevail, it will be found that all parties are nearer together than they supposed; that their true interest lies just on the line which divides these party interests, on which only the few quiet ones dare to walk. We need now the farmer, the merchant and manufacturer. Let each in his department adopt the principle “Live and let live.” For this purpose we have the world as the field of our operation. This village, this town, this county of Worchester, this our New England, these United States, none are large enough to operate in. Our action and industry must tell on the whole world. We have been inclined to circumscribe ourselves- or certainly to pen up ourselves within the old thirteen states. – Or perhaps we would somehow have New England set apart, or kept by itself, for fear with all honesty, that its industry, its ingenuity, its learning, its good taste, its good morals and religion, would be lost, no longer identified. But the Providence of God in its operations and developments is wiser than men. The foolishness of our Heavenly Father is wiser than the wisdom of the best of us. There is more wisdom in the plans of heaven that in all the concentrated wisdom of all political parties united, to effect the good of the world. When you have looked on the movements of our day, both of our own country and of Europe, some score of years hence, who shall be permitted to do so, will be fully convinced of this. We need not go to England, or China, of California, or Washington, or Boston, to exert any influence. The elements of this world, so far as intellect and principle are concerned, are elastic; and if you strike one, so as to make an impression, like a row of ivory balls suspended in contact, you affect all the rest. What you have to do then is not to turn from your calling, but act in your proper sphere; laying hold upon the information which comes in your path. If you have a farm to cultivate, do it with your might; as if you meant to accomplish something in this line business. If you have a manufactory to build, go about that most manfully. Whatever you have to lay your hand to that is good and honest, be about it in earnest. It is this spirit of earnestness and honesty and patient industry that has made New England what she is.

But as we are inclined to take pride to ourselves, not only as New England but also as a nation, as we have grown strong in our youth, and lest we might as we approached manhood become insolent, Providence is scattering among us thorns; sending- not the best specimens- the world to us. We may think in our vanity, that it is for the purpose of having them instructed and converted both politically and religiously. Would that they might become in both respects almost and altogether like ourselves, save those bands of Slavery for the South, and the Fugitive Slave law for the North. But may we not learn something from them? This truly; that man is our brother, and wherever he is found, in our country, or far away, in whatever circumstances, should be one with us. In this respect, the world is our country, our state, our town, our neighborhood, and whatever distinctions there may be in some respects, we are naturally dependent on each other. If England, proud in every thing as she is, has yielded to this nation the meed of praise, as superior to her in every useful employment, and awarded us a niche above all the world beside, we should be ambitious to prove ourselves as humane, as true to the world in all its wants and interests, as the mother country has been: not in arms and blood-shed, let what has been in this respect suffice, but in giving what is far more honorable, and the wiser policy, the advantages of civilization and pure christianity, of freedom and peace, through our faith and virtue, honesty and industry, ingenuity and energy, art and science, hope and charity. We have taught the world whatever may be the advantage of division of labor in its general character, that no artisan in free New England need confine himself to making the twentieth part of a pin. So sorry an account of his life he need not give, if he will but be a man.

True, as yet, but little of the mere polish, the mere ornament, has occupied our attention. What has been done of this character is only a pastime effort, as a matter of temporary gratification. It is rather a matter of accident than aim, that good taste has been combined with utility. Or rather we may infer that whatever is truly arranged for utility and convenience, produces good proportions, beauty, taste, and permanency. This sentiment is well sustained by a graphic writer in the Edinburgh Review. He says: “The tomb of Moses is unknown; but the traveler slakes his thirst at the well of Jacob. The gorgeous palace of the wisest and wealthiest of monarchs, with cedar and the gold and ivory, and even the great Temple at Jerusalem, hallowed by the visible glory of the Deity himself, are gone; but Solomon’s reservoirs are as perfect as ever. Of the ancient architecture of the holy city, not one stone is left upon another; but the pool of Bethesda commands the pilgrim’s reverence at the present day. The columns of Persepolis are molding into dust; but its cisterns and aqueducts remain to challenge our admiration. The golden house of Nero is a mass of ruins; but the Aqua Claudia still pours into Rome its limpid stream. The Temple of the Sun, at Tadmore in the wilderness, has fallen, but its fountain sparkles in its rays, as when thousands of worshippers thronged its lofty colonnades. It may be London will share the fate of Babylon, and nothing be left to mark it, save mounds of crumbling brickwork. The Thames will continue to flow as it does now. And if any work of art should rise over the deep ocean, time, we may well believe, that it will be neither a palace nor a temple, but some vast aqueduct or reservoir; and if any name should flash through the mist of antiquity, it will probably be that of the man who in his day, sought the happiness of his fellow-men rather than glory, and linked his memory to some great work of national utility and benevolence. This is the true glory, which outlives all others, and shines with undying luster from generation to generation, imparting to works some of its own immortality, and in some degree rescuing them from the ruin which overtakes the ordinary monument of historical tradition, or mere magnificence.”

Utility has ever been the watch-word of American genius, and we are happy that it is so. Even in our more ornamental literature we discern it. A tribute is everywhere paid to utility- so that if one seeks to gratify his love of the beautiful and true, for their own sake, he manifests a disposition to vindicate his course on the score of utility. Our sweet poetry betrays it.

Blooming o’er fields and wave by day and night;

From every source your sanction bids me treasure

Harmless delight.”

I am inclined to think that utility and beauty are more nearly allied than we are generally disposed to allow. Are not strength and beauty usually combined? Is it not the strong and beautifully proportioned ship that weathers the most storms and outrides the most gales? Is it not the stateliest, the noblest, and hardiest trees, that gain strength through the pelting of a hundred winters? Now nature has furnished the outline, and made the suggestion which we as its learners should carry out in our enterprise. We are struck with the beauty, and acknowledge the advantages of natural scenery. View the valley of French River. Who as he passes along its stream, beholding the hills rising on either side in beauty and loveliness, extending in graceful and undulating curves, furnishing here and there a lively perspective; interspersed, as it was in early autumn, with trees reflecting from their changing foliage every variety of shade, giving a most picturesque and romantic appearance- not the less so on a misty, drizzly day like one of our October Sabbaths, than in the sunshine; -when the leaves and trees seemed fairy pictures, surrounding us with hills and vales of paradise, not in the soberness of reality, but in the beautiful wildness of a dream; as the gorgeous coloring of the imagination, or a rare deceptions of the painter’s skill, or some enchanted view which at best was a happy illusion. Can we say less, than that nature, in her suggestion of beauty as a model of taste, has done her part? But what do we behold amid this delightful landscape, where dashes along, eternally murmuring, the stream which gives name to the valley, itself full of beauty! Do we not here perceive utility? What constitutes the beauty, furnishes also the power which the ingenuity of man has improved, and thus added excellence and life to the picturesque scenery. But has man fully carried out the suggestion of nature? Some little more attention to the planting and nurturing of fruit and shade trees and shrubbery and flowers around our manufactories, dwelling houses, school houses, and house of worship, where the ancient forest has been torn up, would render this valley of the French River on of the most beautiful, unique, and inviting in the land! This might be the result without the expenditure of much money, time or labor. It would be better than a holiday for young persons to start out on some spring-like morning, collect and plant young trees which might take root and live many generations. This would be less fatiguing and much more satisfactory in the end than what is often done. Many a one, to enjoy a holiday, will hasten to the city and swelter in the sun, chasing pleasure which is ever eluding their grasp. Here, in the pastime of planting trees, there would ensue a living satisfaction; a satisfaction continuing and enhancing with the length of life. Here are change of employment, pastime, stimulus to the mind, interest, exercise, and utility, all combined. Besides it would more than gratify. It would cultivate a love for the beautiful, and serve to produce correct taste, drawn from nature herself.

Sometimes indeed, we have views of the sublime in nature which seem to cast into the background the beautiful. The grand cataract, the overshadowing mountain, the wild tornado, the tempest at sea, and the battle-field even, are accounted grand and sublime. The final results of each may be utility. Such, however, are rare. So in life there are projects and actions and engagements which may correspond. Amid destruction and terror, utility in the end may ensue. But the sunrise, the sunset, the sunlight, the moonlight, the starlight, the veiling cloud, the cheering landscape where waves the grass and grain, where murmurs the gentle stream, where are the pleasant vale, undulating hill, and the rich plain, the village with its spire and manufactories and the distant farm house; these are the common things, intimately connected with the useful and the beautiful which all may enjoy, all full of interest, all connected with pleasant, tender, associations varying in different families and different individuals, according to the checkering of their lives. For every thing bears on it the impress of the character and hue of events, sorrows, and joys which have moved our souls and given interest to our lot.

I may be permitted to remark further, that would we have intelligence and good taste prevail with utility, we need education. It is the instrumentality of success. Let all become ignorant in the true sense of the term, and there will follow a combination of ignorance, worthlessness, folly, and dissipation; indeed any thing rather than thrift and comfort. All persons, old and young, have minds; natural powers; some more, some less. All have a thirst for knowledge. They are inclined, however, to put into operation such knowledge as will furnish them immediate gratification. Some kind of knowledge will be practiced, if not for good, for evil; if not from books, from other sources; if not from schools like the one established in this district during the year; certainly from that extemporaneous school which occurs the year round in the street, or in the bar-room, the bowling alley, the card-table, or some other place of which it is a shame to speak. Now one kind of instruction, such as the Commonwealth provides, and which the munificence of individuals in this vicinity aids to carry out, in our common schools, strengthens the powers of the mind and fits them for the business of human life. But the other kind, gained in the street and other places where virtue is derided, serves to weaken the intellectual powers, as well as the moral and physical. Soon as the buoyancy of youth has passed away there are no resources to which to apply for interest or gratification. The mind can be moved only through the baser passions. Hence many become old, young. Their intellect becomes as feeble as that of an infant. Whatever may be their physical strength, they have no moral or intellectual.

It is wise, therefore, and very wise, to give particular attention to the education of the young all over the land. Education properly conducted is intended and calculated to furnish light and power for the accomplishment of good; not to make the world worse than it is, but better; so as to develop its latent powers and put them into operation. Knowledge is power. To be efficient, it must be practical. Mere theory is not power. Theory and practice, or the knowledge which embrace each, is power. The world has grown old, and yet we have just begun to develop its resources, and to use to advantage principles which have lain dormant since its existence. Fields of action and interest are continually opening. The more we do, the more we may. This is a law, which in its general bearings is true; and still, labor will have the better pay. This may seem paradoxical, and yet it is true and philosophical. There may be occasionally an overaction, producing reaction. But this will correct itself and serve to bring about a true balancing of things. We have been afraid to pay much for education, and too often the cause has been permitted to go begging. There can be no better investment than funds secured for the education of the young. When we pay for schoolhouses, teachers, and apparatus, it is like putting money into the bank, or a premium paid for the insurance of property. If we are not safe now, it is because we have not been heretofore sufficiently liberal. Complaints of taxation, or withholding the proper amount of appropriation by the towns, for purposes of schooling, only proves that the voters have not been properly educated. We are therefore happy to know there are some who feel an interest in this subject, and their actions and professions are alike honorable to their minds and hearts.

There are some considerations to which it would be appropriate to refer today worthy of our attention and sympathy. Death has made inroads upon men in high stations within a few months. Though such events are associated with grief and cast over the mind and heart the gloom of sadness, we may not pass them by when some of them are of so recent occurrence. The community has been thereby affected. Not like those whose hearts have been penetrated by deeper sorrow, where the head of a family circle has been stricken down by the common destroyer, and his place left vacant, literally made an aching void, reminding of the reality in form, in countenance, in affection, in voice, and excellence that was, and is no more. True it may be no more of an affliction for the family of Webster, to part with the honored and beloved head, than for another family unknown beyond private life. Many of the latter class possess keen sensibilities, and strong ties of attachment, equal to those of the former. And in view of such an event they are as deeply afflicted. This day comes to all, thus situated, reviving associations long cherished. The day which has been heretofore the occasion of much happiness, now produces the keenest sorrow; not without mitigation. In view of past joys, and intimacies, and virtues, and hopes, there is even to them occasion of gratitude. It is that which bears the pleasant melancholy of a sunny autumn day when the wind suddenly striking the trees with its startling rustle, drops the golden leaves to turn to earth. They who thus die live in the hearts of their friends and are there cherished, how muchsoever to the bustling, unthinking world they may have passed into oblivion. But the memory of great and influential men, who have been active in the world for scores of years and have left their mark upon it, cannot be effaced. That world, that nation, that community which have known their worth, will be profoundly affected. It is natural for us to inquire, who shall fill their places? Who shall ever exert so powerful and happy influence? Not only do men of the world and political virtue make similar inquiries, as they have done successively in regard to the lamented Calhoun of the South, Clay of the West, and Webster of the North; but we are accustomed to hear the same from other professions, and in respect to men occupying smaller sphere- of the bar, of the pulpit, of the bench, and of the seat of science. Though we mourn their departure, that is human, yet we may be grateful for the lives they have been permitted to live; that what they have done, spoken, and written, are in our possession, and may be preserved so far as on examination and the test of time, there are virtue, truth, and value in them. The Providence of God furnished them with their powers of mind, fitted them for and placed them in their posts. It has removed, checked, or prospered them according to its wisdom. So that we see enough of them to show us that they were human, fallible, erring. And therefore we may not adore the men, whilst we may venerate the principles which they inculcated. In the Providence of God we are tough lessons, which we may receive with thankfulness. Instead of regretting the dispensation which removes them as instrumentalities, and thus honors them, it should be rather a matter of gratitude. We complain sometimes of the ingratitude of the majority towards one who is excellent and deserving. We may not be able to judge of the correctness of the decision of the majority in the time of its expression. If it be of God, it will stand, but if it be of men, it will come to naught. Remember the case of Joseph.The majority of his brethren were against him. They in their wisdom plotted his destruction. Their own wisdom was folly. Their plotting was the plan of God to save both him and them. So God meets individual and nations. He teaches them that they are only men, nothing more. It is not the popular will or effort that saves always, or destroys. But some hidden spring which God touches brings out unforeseen results. These results may be in the highest sense an occasion of gratitude to all concerned. Hence we rely not on any system which men of a party may devise for the perfection or permanency of our government, not on the measures of any political party ever in power or that ever will be. These parties, however proper they may be, or however honest, or whatever name they may assume to catch the popular ear, must be, as they ever have been, changing as to the policy of their action. We rely however, on the overruling power and goodness of God. The things which will save or ruin us do not depend upon so slight a circumstance as securing free trade or a protective system. There are currents of honesty and virtue, of truth and sincerity, of charity and good will; or of falsehood and deception, of vice and wrong, of oppression and ambition, which will bless or curse this nation. All other policies, though they be not the wisest, we may meet. Our government may continue to prosper, if we but have the principles of truth and righteousness as their foundation.

There is one view in which we may consider the deaths of these great men calculated to excite the gratitude of the good. In the providence of God they have so occurred, often, as to rebuke the animosity of party spirit. When Adams the elder and Jefferson died, on the same birthday of our national Independence, this was most happily the effect. Years after, when occurring one of the most exciting canvassings for president which resulted in the choice of Harrison, the Providence of God rebuked that spirit by the marked defeat of one candidate, and the death of the other in a few days after his inauguration. Other instances less marked have occurred which were peculiarly salutary in their effects on the community. And now, just in the height of the excitement in respect to the presidential election, he who was deemed the greatest statesman of the age was smitten down, as if God would rebuke this partly spirit. The lesson, which we are taught is a matter of gratitude inasmuch as we are directed to repose confidence in the great and good Sovereign who knows how and when to make use of the great instrumentalities of mind for accomplishing great purposes and of teaching lessons which take immediate effect. We are compelled to pause long enough in our career to notice it. These dispensations and lessons may not be such as to produce elation of mind; yet such they may be as to afford peace, confidence, and hope, and prompt to happy exertions, and result in more holy and charitable sentiments towards men as our brethren who are of the same blood and bound to the same tribunal.

In closing, we are deeply impressed with importance of religious instruction. Man is naturally a religious being. But his religion frequently degenerates into superstition, and seldom does he pursue the course of truth and consistency. We ought to remember, whilst so much is done for the physical powers and the intellect, the most important and elevated are the religious. Notwithstanding the commendation we give to physical and mental sciences, and the importance we attach to their culture, yet little real advantage, lasting benefit will accrue where the sentiments of the Bible are not inculcated and adopted. Look at intelligent, philosophical France; an enlightened nation, almost literally without the Bible. What is the consequence? Other things may contribute to make the nation what it is. But much of their instability and want of true principle spring from the destitution of that religious element which the use of the Scriptures, with due reverence to their Author and true regard for his government, begets. Whilst the French are the politest nation on the earth, the most polished and scientific perhaps, a nation of gentlemen and ladies, doing everything according to the strictest rules of etiquette; they are the lowest in the scale of truth and virtue. If he adheres strictly to this established code, there is not a sin named in the Decalogue which a Frenchman may not commit and yet be esteemed a gentleman, a man of honor. Now education of the intellect and polished manners, without virtue and religion would make this nation like France. And fatal indeed would the prevalence of such principles of virtue and ambition prove to the permanency of our free government. Hence the need of teaching the truth as the Bible contains it. We need a religion which teaches and enforces the Sabbath as a day to be devoted to God, not a mere holiday. We need a religion which shall have control of the heart and life; which shall put an active faith and a conscience into all our works. The measure of religion called for by many, if not the many, is rather just enough to put conscience to rest and turn faith to presumption. They are not willing to live day by day according to their teaching, their principles. Men like to have seasons when by penalties and penances, they may pay off their accumulated debts of sin, with permission from their conscience thus bought off, to indulge themselves again, or to do up their work of religion a little beforehand. To borrow an illustration from the playful, almost sacrilegious suggestion of young Franklin to his Puritan father, when he was laying down the pork for the season in the cellar; “Why would it not be well,” said he, “to crave a blessing on the whole barrel, and thus save time at the table?” Now though men may not be so light and playful about their religion, yet it is the inclination of the human heart to do up their religious matters in a day, and enjoy the world and sin the rest. This disposition tends to sap the foundation of public virtue. It will, if permitted to gain universal ascendency, serve eventually to overthrow our government. This is an evil with which we have to contend in every good and worthy improvement, not only with respect to the virtues of the heart, but such as are common to the intellect, which are requisite in the true progress of science and the arts and human governments, the true progress of the world.

The End

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!