This sermon was preached by George Glover in 1816.

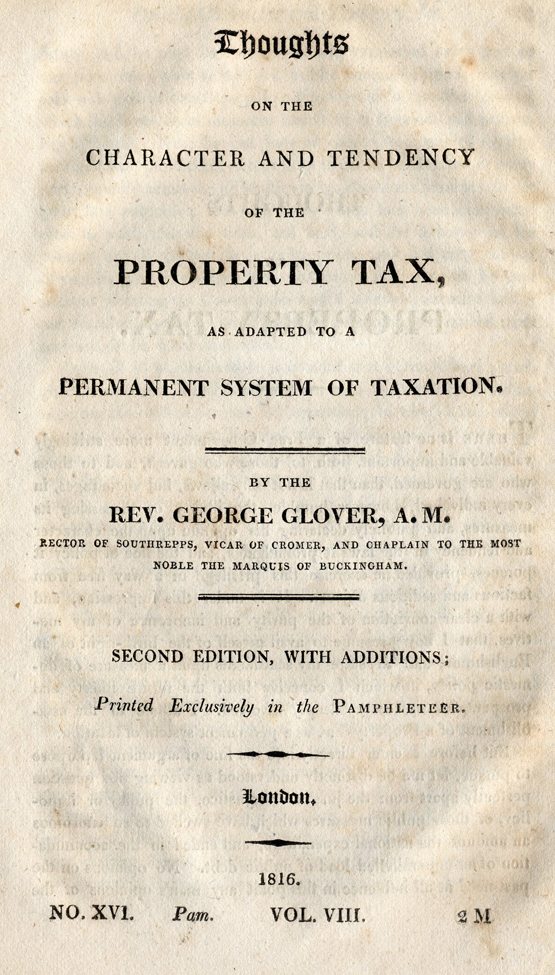

THOUGHTS

ON THE

CHARACTER AND TENDENCY

OF THE

PROPERTY TAX,

AS ADAPTED TO A

PERMANENT SYSTEM OF TAXATION.

BY THE

REV. GEORGE GLOVER, A.M.

RECTOR OF SOUTHREPPS, VICAR OF CROMER, AND CHAPLAIN TO THE MOST NOBLE THE MARQUIS OF BUCKINGHAM.

THOUGHTS

ON THE

PROPERTY TAX.There is no feature of a Free Government more strikingly valuable and important, both to those who govern, and to those who are governed, than that it not only allows, but encourages, in every individual, however humble, the liberty of discussing its measures, and publicly declaring his opinion upon the character and tendency of the laws it promulgates, and the line of policy it pursues, provided he exercise this privilege in a way free from factious and seditious objects. It is under this impression, and with a clear conviction of the purity and innocence of my motives, that I now presume to avail myself of the birth-right of an Englishman, and to state my sentiments upon a measure of domestic policy, in which I conceive both the future liberty and prosperity of my country deeply involved. I allude to the establishment of a Property Tax as a permanent system of taxation.

But before I enter directly into the line or argument I purpose to pursue, let me be distinctly understood as viewing this question perfectly apart from the justice or injustice, the policy or impolicy, of those public measures which have swelled to so enormous an amount the national expenditure, and ended in the accumulation of an unparalleled load of public debt. No opinions on the past need at all influence in this point any man’s opinions of the future, and he who has most zealously supported every part of our persevering contest with its public enemies abroad, may yet join with perfect consistency in an endeavour to save that country which he loves, from measures hostile to its freedom and prosperity at home. Nay, he can have no claims to unsullied loyalty, and genuine patriotism, if he refuse to do so. All men, of every party, equally admit the difficulties in which we are involved to be great and palpable; that the debt which has been contracted must be paid, that the faith, the land, and the industry of the country are all pledged for its redemption; and the only subject of enquiry now is, whether these difficulties may not yet be met without violating the Constitution itself; whether, notwithstanding the dreadful impression made upon its outworks, the citadel itself may not yet be saved from ruin.

Again, if it on one hand be demanded that extraordinary emergencies may arise, which may fully justify a Government in deviating from the ordinary course of legislation; in which speculations in political science must be tried, like speculations in trade and commerce, and in which, as in flights of poetic fancy, “something must be ventured, or nothing can be won,” we may readily concede it. And we may likewise concede further, that on the part of the subject also, it may in every such crisis be perfectly consistent with the greatest love of freedom, and the purest patriotism, willingly to sacrifice a large portion of his rights, his liberties, or his property, as the price of securing the remainder. But then on the other hand, it must equally be conceded, that all such occasions are strictly limited to the duration of the circumstances from which they arise, and that the expediency of all measures emanating from them entirely ceases with the danger they were intended to meet and to repel. If in times of great public calamity and alarm, when the very existence of the state was endangered, Rome wisely had recourse to a dictator, and more than once owed her safety or her victories to a measure which necessity dictated, we never can forget also that not only were all the benefits, which heretofore resulted from such a measure, lost and forfeited, but exchanged for the heaviest calamities and oppressions, from the very moment that the delegation of this high and despotic authority ceased to be carefully measured in continuance by the same necessity that prescribed it. If the temporary power of Cincinnatus ensured the safety and added to the glories of his country, the perpetual exercise of the same authority by Sylla and by Caesar, mark the very period of the commencement of the decline and fall of the greatest empire of the ancient world.

It is unfortunately the natural inclination of all power and authority, however acquired, to endeavour to perpetuate themselves. Their universal maxims are to advance whenever they can, to recede only when the post can no longer be maintained; to consider even a momentary acquiescence as a tacit admission of their claim, and the uninterrupted possession of a somewhat longer period, as directly confirming their title, and sanctioning even the principle itself upon which they are established. To this invariable propensity it is owing that the wisest and purest institutions become gradually corrupted and undermined, and abuses, like evil habits, gathering strength by connivance, or fattened by indulgence, grow till they either entirely destroy the fabric, or render some desperate measures needful to correct and restore them to their original character and use. It is in this sense that states and empires have been justly compared to bodies, as equally distinguished by youth, by manhood, and by old age. It is on this ground that in politics, as well as in morals, the ancient axiom of “Principiis obsta” is for ever applicable and useful; an axiom peculiarly recognized in the British Constitution, and upon the strict observance of which its very existence must depend. To check innovation by a mutual watchfulness over the proceedings of each other, and to sound the alarm on every attempt at encroachment upon each other’s hallowed ground, and thus to preserve unimpaired that nice balance of power which forms the very essence of the Constitution itself, is the express scope and object for which the several estates of the realm are invested with the trusts and privileges they hold.

Whichever therefore, whether it be King, or Lords, or Commons, either remits or relaxes this vigilance, that branch of the Constitution not only forfeits and abandons its own rights and privileges, but betrays the sacred duty it is pledged to perform, and is guilty of a direct injury against the community at large. There is this further reason also for guarding against political innovations, particularly such as I now allude to, that they commonly produce many effects besides those that are directly seen or intended by them. Paley 1 has justly observed, that “the direct consequence is often the least important; that it is from the silent and unobserved operation, from the obscure progress of causes set at work for different purposes, that the greatest revolutions take their rise;” and has illustrated by several striking instances, drawn from our own history, the truth of his remark. De Lolme 2 has also, with no less accuracy, told us, that “governments are often found to have adopted unawares measures entirely calculated to change the very character of their constitution, and to go on without perceiving their error till it be too late to correct it.”

That the measure to which I mean these prefatory observations to apply, is of that insidious tendency above described, is, alas! too obvious, from the present attempt to impose it on us as a permanent burthen, when compared with the arguments and professions held out at its original enactment; and that it partakes also very strongly of the nature of those measures alluded to by Paley and De Lolme will, I fear, be likewise too clearly proved when we come to consider it in that point of view.

But let me previously crave the indulgence of a few words only on its rise and origin. The circumstances attending it are indeed too notorious to need much illustration, but yet it seems necessary just to advert to them in order to clear and make good my way as I go on, and to establish the point of its being not only a novel and extraordinary system of finance, but to have arisen from a very extraordinary crisis of public affairs; to have been originally proposed as a temporary measure of unqualified necessity, and on these grounds alone submitted to by the country. We all remember how the ministry of that day, as well as a great majority of Parliament, impressed with the most violent apprehensions of the spread of that revolutionary frenzy which had deluged France with the blood of her subjects, which had led her monarch to the block, and overturned or profaned her altars, had judged that the only means of safety and honour to this country was to be found in an appeal to arms. Even those who had hailed the first heavings of this great volcano as symptoms of regenerating health, and greeted them as the struggles of an oppressed people in the sacred cause of freedom and of independence, as the auspicious pangs of liberty just dawning upon a land of darkness, spiritual as well as civil, now terrified at the magnitude of the explosion, joined in the general forebodings of an universal wreck and desolation, unless every effort was exerted to ward off the impending storm, and the sword and the purse, and the pulpit and the press, were all summoned to answer what was termed the calls of religious and social order. A small but resolute phalanx did indeed still remain unawed by the fears which staggered others, and widely differing as to the best means of stilling the impetuous impulse; who still clung to pacific measures, still viewed the thunder that rolled and the lightning that flashed around us as the natural attendants of a hurricane which might yet settle into a tranquil calm, and perhaps even purify and improve the atmosphere in which it had spent its rage; who still thought that other nations should be left to their own discretion as to what form of government they might judge it expedient to adopt, and that policy, no less than justice, demanded from us to forbear interfering with the internal affairs of France. But the warnings and admonitions of these men were unheeded in the general panic, or unheard in the general outcry; and the war-whoop of government was re-echoed from an immense majority. An immediate and determined course of hostilities was agreed on; the ocean was soon covered with our fleets and transports, and our blood and our treasures were equally lavished with unsparing energy. The powers of the continent were pressed into the hallowed cause, and entreated to accept the aid and subsidies of Britain in defraying the expenses of the contest. Coalitions were formed and crumbled away, fresh ones again tried and proved faithless to their object, and our bleeding country still persevered undaunted or uninstructed by the lessons she received.

The enemy, instead of being prostrate at our feet, as had been so confidently anticipated, seemed only to gather fresh vigour from every attack, to imbibe fresh means of resistance from every blow, and to acquire union and consistency, and strength and wisdom, from the very means of experience we afforded her. She even threatened in her turn to become the invader. “Delenda est Carthago,” was her motto. The sacking of London was held out as the recompense of their toils and dangers to her exasperated soldiery, and her chieftains threatened that the waters of the Thames should be reddened with British blood. It was at such a crisis, after six years of unparalleled exhaustion of blood and treasure, when voluntary contributions had been dried up; when the old taxes on luxury and consumption had been doubled and trebled in vain; when new ones had been imposed and proved ineffectual; when the monied interest had been drained of its funds, and loans were hardly made, even at the most exorbitant rate of interest; it was at such a crisis, I say, that the measure of the Income Tax was pressed upon the adoption of the British Parliament, and submitted to by the British people.

In the discussions which took place concerning it, it was never attempted to be argued but upon the ground of extreme necessity alone, nor do I believe that either Pitt himself, to the latest moment of his life, or those who acted with him, ever entertained a thought of saddling such a burthen as a permanent load upon the country, nor that even in the zenith of his popularity, he would have ventured to propose it. When the Lord Chancellor supported it in the House of Lords, he was glad, in the scantiness of better matter, to avail himself of this anecdote, as the best illustration of his subject. “A noble person, a friend of mine,” said his lordship, “had a conversation with a tradesman on the subject of this bill, who said his income might amount to about L300 a year, and declared that he thought it hard to pay L30 out of it for this tax. The tradesman, however, was a barber, and on a little reflection said, ‘But perhaps if I did not pay the L30, so many of my customers would not long have their heads upon their shoulders to be dressed and shaved.’ And this,” added his lordship, “is the true and proper defence of a bill like this.” And further also, when Lord Sidmouth, at the head of an administration composed of those very men, who are now endeavouring to perpetuate this despotic and intolerable measure, brought down to Parliament the treaty of the peace of Amiens, he embraced also the same opportunity of instantly moving the repeal of the Income Tax, and emphatically declared that he wished to record his sentiments upon it, “that he had ever viewed it as a measure which extreme necessity alone could justify, and as totally inapplicable to a state of peace.” Surely, then, a measure thus introduced, thus supported by its ablest advocates, and thus described by ministers themselves, bore in its very character, independent of the terms of the act itself, the pledge of its being discontinued the very moment the crisis passed away which had called for its enactment, and surely the people who have so long patiently submitted to its operation under such circumstances, have now an unquestionable right to look for its repeal.

If any man be disposed to think such arguments of but little weight, and the principle for which I am contending of but little value, I would beg him to reflect only upon the paramount consequences they involve, and to examine with me, by a short reference to the history of taxation in this country, how they were estimated by our ancestors, how firmly, how constantly, how successfully, (except in one solitary instance, which I shall shortly notice, viz. land-tax,) they were acted on by those illustrious men to whom we owe every political blessing and pre-eminence we enjoy; to whom we owe a debt of gratitude, which can only be discharged by faithfully transmitting to posterity, unsullied and unimpaired, the legacy they bequeathed to us.

The revenue of the crown is divided into two great branches, namely, the ordinary and extraordinary. By the former is meant the real actual property of which it is possessed, and a few sources of income which do not come under the denomination of contributions levied on the people. These were in the early periods of our history so large as almost, if not entirely, to meet the ordinary expenses of the state, and might, by the laws of forfeiture and escheat, have been augmented to an extent truly formidable. But, fortunately for the liberty of the subject, this hereditary landed revenue has been, by the extravagance or neglect of the crown itself, dilapidated and sunk almost to nothing, and the casual profits, arising from the other branches of the census regalis, have been almost all of them alienated likewise. These deficiencies as they gradually occurred, were necessarily to be supplied by those who had succeeded to these new sources of wealth, or by those who, being protected by the government and constitution, were bound both by duty and interest to contribute to its support and maintenance. The first contributions demanded and paid were those of personal military service at their proper charge, and sometimes small temporary aids of money or merchandize, for the equipment of ships, or defraying the extraordinary expenses attendant on particular expeditious.—Henry the Second availed himself of the fashionable zeal of the times for crusades, to induce the people to submit to a new species of taxation, denominated Tenths and Fifteenths, but these were never levied except for extraordinary emergencies, and though the basis of a regular assessment was afterwards laid in the eighth year of Edward III. yet it still both originated from a war, till that period, unmatched either in exertions or expence, and, what is more to our present purpose, was never acted on but in times of necessary and absolute emergence. In short, in whatever shape, or under whatever denomination, whether of tenths, scutages [Medieval tax paid to avoid military service], talliages [Medieval tax paid by peasants to the manor lord], or subsidies, supplies were levied on the people, this principle was up to the period of the Revolution never violated, that a tax imposed upon an emergency ceased with it; it was never suffered to become a permanent engine of supply, and Blackstone is in this important point inaccurate when he asserts that those ancient levies were in the nature of a modern land-tax. Rude as we are apt to consider the notions of political economy in those times, and limited as were the advances of civil liberty, yet our fathers were not so rude, and, fortunately for us, neither so profligate nor abject as to go the strongest constitutional check a subject can possess against the encroachments of despotic power. And it is obvious to remark, that whilst to their determined courage and perseverance in maintaining it, we owe all the freedom and political advantages we enjoy, to a deviation from it, in later times, we owe the numerous evils and corruptions with which we are now weighed down, the purity of our Constitution sullied, and its beauty tarnished and impaired.

The period of the Revolution is often looked back to as an era glorious to the cause of freedom civil and religious, as an immortal triumph of rational liberty over oppression and arbitrary power. In very many instances it really was so. But human blessings seldom come unalloyed; and if it was distinguished by acts calculated to promote the happiness, and exalt the dignity of our nature, it was instantly followed by acts as unfriendly to them both, and as directly subversive of the character of the Constitution it had contributed to form. Amidst the violent collision of parties alternately in power, and each consenting to purchase that power by a servile compliance with the unconstitutional demands of the crown; amidst the shameless scenes of bribery and corruption, and consequent prostitution of public principle which pervaded the national Councils and polluted the morals of the whole kingdom, aided by the opportunities for giving them full exercise, which arose from the unsettled state of the times, and the obstinate wars which were waged in order to support the change that had been effected, and in which the people were assured, not only that every right and privilege they had just established, but also the very lives and fortunes of all who had shared in contending for them were at stake: in short, in times not very dissimilar in some points to those we have lately witnessed, was laid the ground work of almost all those great political errors which have since been committed and pursued amongst us. It was then that the first sanction was given to a standing army; it was then began the prevalence of those foreign connections which involve us in every quarrel of every Power of Europe; it was then sprung up the pernicious practice of borrowing upon remote funds, and leaving to posterity to pay the amount of our extravagance and folly: it was then was laid the foundation of our national debt, and, to crown all, it was then that first appeared that great prototype of the odious measure we are now discussing, the establishment of an Income Tax a measure from which the struggle of 120 years has not been able to redeem us. For though the tax on personal property, on trade, and on individuals was soon found too oppressive to be borne, yet the Lane Tax, which formed a part of it, was not only most unjustly and inequitably continued, but established as a perpetual charge, its produce mortgaged as a freehold estate vested in the crown for ever, and like a freehold we have seen it held up to sale, and become a fit object of purchase to whoever maybe inclined to buy it.

With such a precedent as this before him, standing like the warning beacon on the hill, and distinctly pointing out the shoals and eddies with which it is surrounded, that man must be infatuated indeed who will not use his utmost effort to avoid them. For such in all human probability is the destined progress of the present Income Tax, if allowed to proceed one step further than the point at which it has now arrived. 3 As a war tax its duration is now expired. As a part of a system for the peace establishment, it assumes a character new and formidable in the extreme, and I trust no man can be so blind as not to be sensible, that, in submitting to it longer, he is not only giving up for ever for himself, his heirs, and successors, under every possible situation of public affairs, 1/10th or 1/5th, or whatever may be the ratio at which it is now proposed to continue it, but that he is giving his sanction to the principle itself upon which this tax is founded; namely, that the Government of this country is entitled to demand a certain part, absolutely unlimited, of the income of every individual, and is also entitled to enforce that compulsive requisition by the strictest and harshest regulations; a principle fitted perhaps for the meridian of Constantinople, but surely unfitted for the tempered atmosphere of Britain.

I have thus far argued the question upon the general abstract principles of legislation, and confined myself to simply illustrating those principles by a few opposite examples, drawn from our own or other countries. Let us now proceed to a more distinct and minute examination of this financial monster, and see whether there be not enough even in its peculiar features and character to induce us to reject it with abhorrence and disdain.

All taxes which can be imposed in a country like this, without tending to destroy the character of the Constitution under which we live, must necessarily have these three essential properties:–

1. They must not infringe that nice balance between the revenue of the state, and the wealth of the individuals who compose it, without which neither national liberty nor prosperity can exist.

2. They must not tend to obstruct that salutary control over the raising or the expenditure of the public money which belongs to the Legislative, over the Executive, Branches of the State.

3. They must, in common justice, bear, as far as possible, with an equal and impartial weight upon the various classes of the community. By these plain rules, of which the most zealous supporters of administration can neither question the propriety nor the truth, let us try the tax in question.

First—As it affects the balance between the revenue of the state, and the individuals who compose it.

Montesquieu lays it down as an established maxim, that “the public revenues are not to be measured by what the people are able, but by what they ought to pay;” 4 and the reason is plain and obvious. Because, unless the demands of the state have some definite limit or control, they may proceed to swallow up the whole wealth and property of the country. The revenue may thus fatten upon the poverty of those who supply it; and the state may outwardly make a brilliant and imposing figure, while it is inwardly groaning under the pressure of the heaviest misery and want: and we accordingly find this to be more or less the case in every despotic state, in which the principle I have mentioned is usually but little regarded.—Whether our own country has not of late years been fast approximating to such a situation, may perhaps be questioned or denied; but it must at all events be admitted, that no measure, which human ingenuity could devise, can be more calculated to produce such an effect, than that which we are now discussing. So long as our taxes were imposed on articles of luxury or consumption, they found their natural limit, and their progressive or diminished amount could always supply to the government that invaluable criterion of the country’s ability or wealth, without which every speculation in finance becomes vain and arbitrary, and even the most able and patriotic minister can no more justly regulate his expenditure by his means, than the mariner can steer his prescribed course through the trackless ocean, without either compass or star to guide him.

Whilst, therefore, on one hand, a timid and cautious administration might be led by an ignorant and groundless apprehension of the magnitude of our resources, to compromise the national interests or honor, a lavish and ambitious government might be led, with equal ignorance of what they were about, to plunge headlong into the wildest and most extravagant schemes, and to persevere till they ended in irremediable ruin. For there is in fact no other safe rule whatsoever, of what a people ought to pay, and consequently of what a free government has a right to expect or to demand, than what it is willing to pay. The general habits of a whole country are never so marked by parsimony and self-denial as not fairly and fully to spend as much as their means and situations of life will justify; the danger is, lest they should run into the contrary extreme. And though, perhaps, a few individuals should be found whose love of accumulating wealth was carried to an improper length, and whose circumscribed way of life led them to avoid many contributions in which they might justly be expected to share; yet these solitary instances can never affect a great general rule, and still less when we observe these niggard propensities hardly ever to extend beyond a single generation, and that accumulation itself always eventually turns out to the direct advantage of the state. The above mentioned great authority has therefore, with his accustomed penetration and truth, observed, that “if some subjects do not pay enough, the mischief is not great, but if any individual whatsoever pay too much, his ruin must redound to the public detriment.” Whenever, then, a country finds the ordinary course of indirect taxation ineffectual, and is driven to the extremity of a tax on Property and Income, it may rest assured it is passing the limit of regular supply; that it is deducting the full amount of whatever is raised in that way, from the actual wealth and capital of its subjects; that it is withdrawing just so much from the useful and profitable employment of agriculture, trade, or commerce; that it is cutting up by the roots the very means and sources of future prosperity, both public and private, and, like the man in the fable, killing the goose to arrive at the golden egg.

Let any man but apply the same process to the management of his affairs in domestic life, and the consequence is too direct and inevitable to require even to be stated. Remember that nations are but private families on an extended scale. If even as a temporary measure then such be its operation and effect, how can it ever be suited to become any part of a permanent system?

And whilst considering it in this point of view, reflect upon the complete extinguisher it applies to every spark of patriotism and of public spirit. Is it possible that the subjects of any government can feel a proper degree of attachment to it, or support with any feelings of national interest the measures of policy it pursues, when they find not only that portion of income exacted from them which they can really and prudently afford to pay or to expend, but their very capital itself systematically encroached upon, without any regard whatever paid either to the exigencies of their situation, their family, or their means? Must they not necessarily have constantly before their eyes both national and individual bankruptcy, and who can then wish to support the national honor, or even to defend a country when it has been bereft of everything in it worth defending? No—the natural progress of human feeling will be this: industry, no more encouraged and rewarded, will sink into apathy and disgust; indolence and indifference will usurp their place, and the only resources left will be despair and exile, or perhaps a burst of manly indignation, or a paroxysm of revolutionary frenzy.

If this picture be suspected of being overcharged, show me but in what point my premises are wrong and I will readily acknowledge the error of my conclusions. Let me not, however, be told, as the country often has been, that the Income Tax has gone on for years gradually increasing wealth and property of the country. Let me not be told that numbers of individuals may be found whose capital has gone on increasing under its operation, and that this also is a proof that it is not incompatible with private prosperity any more than with public welfare. Alas! the former of these effects may unhappily be traced to a very different source and origin; to the augmented energies of tax gatherers and inspectors, excited like officers of police by extravagant premiums allowed them upon the detection of frauds, to a more exact and rigorous assessment, to the exemptions originally conceded being gradually withdrawn, to the deductions at first allowed being narrowed or excluded, and, above all, to the rapid and accelerated depreciation of the circulating medium. Whoever will but minutely examine these several heads, will not only find a direct and easy clue to the solution of such a financial problem, but he will arrive, as I have done, at a directly opposite conclusion: he will find from these operative causes, when combined together, an aggregate infinitely greater than will be met by the increased produce of the tax in question, and instead of being led away by an argument so specious and so plausible, he will find himself irresistibly compelled to admit that the progress of compulsive taxation can never be established as a safe criterion of the progress of public wealth, and that in the point in question it is directly the reverse. He will find a balance which nothing but the diminished wealth and prosperity of the country can be made to account for. Until this position therefore be controverted, it is almost needless to go into any refutal of the other; it is nonsense to talk of public prosperity which is purchased at the price of private misery and oppression. Nor can the instance of a few individuals, who have even grown rich under its operation, be ever correctly pleaded against the sweeping general effect unquestionably produced by it; an effect, the force of which has never until now been left to its natural impulse, but has been fenced off by the increasing and exorbitant price of corn and provisions, which has enabled both the land owner and occupier to struggle with its burthens, and by a thousand other causes connected with a state of war, which will suggest themselves without enumeration. But these stimulants act but for a season, and any permanent system, attempted to be bolstered up by such expedients, carries with it the seeds of speedy dissolution.

But there is another point connected with its influence on capital, which seems entirely to have escaped those who can rest satisfied with arguments such as I have been just now combating. They forget that exactly as an estate loaded with a private mortgage is diminished in value to the proprietor by the full amount of the encumbrance, just so does every shilling added to the public debt lessen the capital pledged for its redemption, and every direct tax levied to defray the interest, or raised to discharge the principal, constitute an outgoing, detracting in its full proportion from the worth of every acre of land in the country; and if any one should require to have this fact still more fully illustrated, let him but ask himself whether a property, producing a clear rental of one thousand pounds a year be not of more actual value than one subject to a deduction of one hundred.

2. We will not proceed to examine it as affecting that control over the levying and expenditure of the public money, which is so wisely entrusted to the legislative, over the executive, branches of the state.

When the historian of the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” is enumerating the measures adopted by Augustus, to destroy the liberties of his country, he reckons these as the most prominent and effectual: “The establishment of the customs was followed by the establishment of an excise, and the artful scheme of taxation was completed by an assessment upon the real and personal property of every individual.” Alas! how little did Gibbon think, at the time he penned this sentence, that not thirty years would have revolved before his own native country would furnish an exact parallel, as to its finances, of the melancholy picture which he drew. It is from the warnings of history that the statesman should imbibe instruction; for he is there neither exposed to the bias of prejudice, nor left to the perilous hazard of probabilities and conjecture; he has before him the sure test of experience for his guidance, and as Lucian beautifully observes, is “οντι ώδε η τωδε δοξει λογιζομενος, αλλα τι πεπρακται λεγων.” De Hist. Scribend. To the strength and power of this political engine, in extorting money from the people, which can be extorted in no other way, we are undoubtedly to attribute the fondness with which it is adhered to as a measure of finance; added to the clear prospect it affords to any government, if once firmly established, of setting at defiance all defalcations of revenue which might arise from the extraordinary pressure of other taxes, or from the unpopularity of its own conduct. Nay, give but to an unprincipled and profligate administration, such an instrument as this, and it never can want the means of securing a majority to uphold its measures; and let us but remember the high authority which has told us, “whenever that day shall arrive, that the legislative branches of the state shall be more corrupt than the executive, the death warrant of the British constitution will be signed and sealed for ever.” Again, the facility which it affords, by its unlimited character, of raising the most exorbitant supplies, will for ever operate as a direct incentive to extravagance at home, and a temptation to wars and all their attendant train of evils abroad. The best security of peace has ever been found to consist in the difficulty of supporting war. The friend of humanity and religion surely then will pause before he gives his sanction to such a source of bloodshed and of crimes, to the establishment of a system which no good government should ever wish for, and with which no bad one should ever e entrusted.

Let me but again and again implore the attention of my country to the few topics I have suggested on this head. They are pregnant with matter and reflections, upon which I could write whole volumes.

3. The third criterion by which I proposed to try how far the Income Tax was consistent with the character of our constitution, was its pretensions to equality and justice.

That every individual, possessed of an income beyond a very limited amount, should indiscriminately contribute to the state the same percentage upon the income he so enjoys, may appear, at first sight, a fair and equitable allotment of the public burthen. But this illusion soon vanishes, and fresh proofs of inequality and oppression strike us in every possible view in which it can be contemplated. In the first place, the difference between a real and personal estate, between the positive value of one hundred pounds a-year arising from land, and the same sum derived from the interest of a mortgage, or the funds, is too palpable to be disputed. In most instances, the one is nearly double, and in many treble the value of the other. Now as a tax can only be considered as a price paid for the protection and security enjoyed, it is clear that any equitable principle would demand, that the amount of the insurance, if I may so term it, should be proportioned to the amount of the property insured.—The Income Tax, however, not only acknowledges no such distinction, in the instance now before us, but it is perfectly notorious, that whilst the tax upon personal property is rigorously and exactly levied, the assessment on real property is, in nine instances out of ten, very considerably below the actual income derived from it. On the other hand, in cases where no evasion is practiced by the landowner, the pressure falls upon him with an excessive and disproportioned weight. It is true that as landlord, he is demanded to pay but his ten per cent; but it is perfectly clear, that whatever is levied upon his tenant, must be ultimately borne by him; and that in every contract made for his land, the amount of Income tax will, and must, form as necessary and regular an item in calculating the amount of outgoings, as compared with the amount of produce, as either his rent, his poor’s rate, or his tithes; and thus the nominal assessment of ten per cent is in fact seventeen and a half. And to this again may fairly be added also, the amount he pays for land tax, where it has not been redeemed, (and in that case his exemption has been dearly purchased) for the land tax I have already shown to be neither more nor less than the remnant of an old income tax, established soon after the revolution, and which is the only part that most inequitably has not been repealed; thus making aggregate of thirty-seven and a half direct taxation.

Again also, with respect to land, how does this apply to those who occupy their own? They are subjected to its operation in the double capacity of landlord and of tenant; and in any depression of agriculture, are called on to pay a tax upon that occupation, which is not only productive of no profit or income whatsoever, but of direct loss. This melancholy fact needs no illustration from supposed circumstances, nor any ingenuity of argument to support it. A simple appeal to the present situation of things in this country, will speak with more energy than any powers of language—A situation which has driven even ministers themselves, either impressed with the manifest hardships and oppression of such a demand, or with the total impracticability of enforcing it, to burst through one of the strongest barriers of the constitution, and without any sanction of an assembled Parliament, to remit a portion of its claims. Will any man then pretend to imagine, that a system of taxation, liable to such circumstances, and to such fluctuations, can be a fit permanent system of supply, in a free country, and under a government which is intended to afford an equal and effectual protection to all those who live under it?

But if these instances of inequality be sufficient to render it objectionable, what shall we say of its boasted impartiality and equity when applied to the poor annuitant, whose income, already burthened by a variety of other taxes, is again rigorously and sternly decimated by its operation, by an assessment which acknowledges no distinction between a precarious supply, constituting in thousands of cases, all the present means of subsistence for a numerous family, and the savings from which are the only hope to which they cling for a provision in the future? Could those who enacted, and still more those who are yet inclined to support such a measure of taxation, but place themselves in the situation of the humble individual who is now penning these remarks, they could not fail to be actuated by his feelings.—Every notion of party spirit, every distinctive sensation of Whig and Tory, as well as all those false ideas of national splendor by which mankind are so apt to be dazzled and led away, would be at once absorbed in the more tender, and I will add, more amiable sensations of a husband’s or a father’s duty. They would feel that the private scenes of life demand attention as well as the public; and that it is too much to require from human nature, to witness calmly the wide waste of a lavish expenditure, in maintaining standing armies abroad, in providing sinecures or in building palaces at home, and to feel at the same time the total inability of either supporting the charities demanded from one’s situation, or laying up a single sixpence for future exigencies, or even of fighting against the imperious demands of the present moment; and still more to submit with silent resignation to have such a scheme of finance established as a perpetual burthen; and to be told at the same time; that it is pursued because it is fair in principle and equitable in operation and effect.

Again, the varied situations and professions of life render the unavoidable expenses attending them equally varied; and whilst one man may be enabled to fulfill the duties, and support the decencies of his station, upon 500l a year, another is necessarily exposed to the demands of at least 1000l. No direct tax whatsoever can meet these varied exigencies, and much less the tax in question, which passes over the whole, and leaves them unnoticed or unknown; which sweeps, with indiscriminating severity, its equal demands from all, and contemplates a numerous family, or an expensive profession, as not less subject to its claims than the unexpensive bachelor or the retired maiden. I am not begging for charity; I am not urging my own case, as one of peculiar hardship, but I feel it necessary to give it in defence of the argument I maintain. I have a wife and seven children looking up to me for protection and support: my means of affording these are chiefly derived from the tithes of not an extensive parish; the income tax upon those tithes has been exacted and paid, and yet one half of the income at which they are so assessed neither has yet been discharged, nor is likely to be soon, if ever recovered; some of it unquestionably lost. Thus much for its mild and equitable operation, as applied to annuitants and life interests.

When I go on to consider the income tax as applied to trade, I am totally at a loss which I should most wonder at, the boldness of him who proposed it, or the patience of those who have so long submitted to this oppressive burden. Credit and mutual confidence are the great bases of commercial intercourse. Secrecy both as to gains and losses, is always deemed not less essential to its prosperity. But with unceremonious intrusion, the income tax violates and invades every one of these stamina, and while it tempts on one hand the ruined bankrupt to make a show of profits and of income which he does not possess, and affords him a friendly screen for his frauds and his imposture, it pries with inquisitorial eye into the concerns of the honest and substantial trader, and exposes the channels of his trade; and if the commissioners, vested with an authority greater than the dictators of ancient Rome, happen only to suspect him of making too limited a return, an oath is immediately demanded, in direct violation of that sacred maxim of British jurisprudence, which compels no man to criminate himself.

We have hitherto supported the character of a great commercial nation, and, like Tyre and Carthage of old, have made the whole world our tributaries, and induced them to pour, with a lavish hand, their wealth into our lap. Arts and sciences have felt the inestimable value of such an extended intercourse; and even the great truths of divine revelation have been illustrated and confirmed by its means. When that distinguished author, Mr. Roscoe, portrays to us, in the family of the Medici, the characters of a few Florentine merchants, becoming at once the patrons of whatever of science and of literature then existed, and the restorers of whatever could be redeemed from the wrecks of time, the lesson, which such examples hold out to us, rises in value and importance every step we advance in its perusal, and we cannot help feeling a pride and exultation in reflecting that we have ourselves gone far to emulate their virtues; that characters not to be surpassed in any age or any country may be found in the annals of British commerce. But Florence was a free republic, and I remember no traces of an income tax like ours, being there established. We also have a constitution virtually and essentially free: a splendid monument of the accumulated wisdom of past ages. Let us endeavour to keep it, if possible, from being tarnished. Let us not give such a death-blow as this to commercial integrity and independence. It has been thus far borne up against by the fond and constant expectation of soon seeing it at an end; but, if it is now to be continued, farewell hope, and farewell commerce!!!

There is one point more which I feel myself peculiarly bound, as a minister of religion, as well as a subject of my king and country, not to pass by unnoticed, which is the dreadful influence upon public morals which has already been produced by it, and will continue to spread with accelerated progress, so long as this odious tax shall continue to be saddled upon us. The best ground of national prosperity has always been admitted to consist in national virtue. But the income tax, by placing men’s interests in a regular and systematic opposition to their duties, holds out so direct a premium to fraud and perjury, that no man who has attended to the duties of a commissioner, can have failed to remark the bare-faced prostitution of principle, the gradual and increasing disregard of the solemn obligation of an oath, and the various temptations to subterfuge and deceit, which are perpetually held out and yielded to, under its wicked and abominable operation. For instance, the capitals employed in trade and in agriculture have been ascertained to be very nearly equal, and there can need no further illustration of the sum of fraud and evasion which have been practiced under this tax, than the simple fact, that out of the fourteen millions a year to which it has been pushed, two millions and a half is the very greatest sum that could ever be extorted from trade. In fact, even the commissioners themselves have shrunk back from the scenes of iniquity arising out of it, and acquiesced in correcting or softening the hardships of the legislature by admitting a mitigated claim. If, then, no other argument can influence, at least let this have some weight with us. If we are careless and indifferent to encroachments on public freedom, let us at least not add to that havoc the devastation of public morals. We have no superfluity of virtue, whether public or private, to be idly sported with. It is a stake which should never be hazarded, and especially when the odds are so fearfully against us.

I have now done with my reflections on the character and tendency of the income tax, and have, I trust, distinctly shown it to be inconsistent with all our best notions of those principles of legislation which are applicable to a country like this, and deficient in every essential property of a tax suited to a free government; that it is arbitrary and unlimited in principle, partial and unjust in operation, destructive of agriculture, and ruinous to commerce; that it saps the foundation of public virtue, and commits the most horrible havoc upon public morals.

To the principle of this tax, I would finally most earnestly implore the attention of my country; because by keeping our eye steadily fixed upon it, we shall be best put upon our guard against being lulled by pretended modifications and flattering amendments. No, the principle itself is so wrong, so hostile to the character of our constitution, so directly opposed to our future welfare and prosperity, that nothing can make it right. You might as well reconcile truth with falsehood or light with darkness. However sweetened or seasoned to make it palatable, it will still be a sop of deadly poison; however covered and concealed, it will still contain a hook within it, which will not fail to fasten upon the vitals of the constitution of this country, if the people should ever be unfortunately prevailed upon to gorge it.

I am aware that the general and sweeping objection to all I have here urged will be this: “You have admitted the difficulties of the state, and you have admitted that they must be met; but whilst you have confined yourself to exposing the tendency, the character, the errors, and the defects of one system, you have scrupulously abstained from suggesting any other. It is easy to find fault, but he that presumes to do this, should be prepared to show a remedy.”

I must, however, totally disclaim the correctness of such a conclusion, and I must distinctly maintain that the onus of extricating us from our dilemma rests entirely with those who brought us into it. The country has a right to demand from those, in whom it reposes its confidence, that they shall, in the first place, adopt no measures calculated to infringe the liberties, or obstruct the happiness and prosperity of its subjects; and if, unfortunately, any emergency should arise, which may call for extraordinary means to meet it, that they shall take care that the means so adopted shall not be more than commensurate with the exigence; and that they affect as little as possible the public interests; and the very moment the exigence has past away, they are answerable for restoring us to our former state.

Still, I will not avail myself of such an apology, but shall proceed with unfeigned diffidence though without reserve, to state what I conceive to be the best and shortest path out of the miserable labyrinth in which we are involved. 5

There appear to be three ways of effecting this desirable object.

The first is that of continuing the Property Tax as a permanent burthen. This, I think, I have fairly proved ought not, cannot for one single moment be entertained by any one that knows what the constitution of his country is, and would willingly preserve it.

The next is by laying our hands upon the Sinking Fund, and appropriating a considerable part of its produce to the present wants of the country, a scheme but very little less objectionable than the former, because, instead of being calculated to remove, it must directly operate towards rendering the public burthen permanent. You can never get rid of debt by cutting up the means of discharging it. The Sinking Fund has always been looked to as our great palladium and shield by all parties; and when Fox pronounced his funeral oration over his deceased rival, he said, “widely as I have differed from him through life, in public measures in general, I will not withhold my praise from one, viz. the Sinking Fund; a measure which will go down to posterity as a monument of his talents as a financier, and if honestly maintained and adhered to, may one day save the country from ruin.” The too rapid extinction of the National Debt, and the prevailing dread of its influence upon the money market, are bugbears which I should be very glad to see assuming a more distinct and substantial form. At present they are but barely visible, even with a powerful microscope. If, however, we must believe such dangers to exist, they are at least so remote as not to press for any immediate attention, and abundant expedients are always at hand to anticipate or draw off a superfluity of wealth.

The third, and only remaining expedient, then is a plain and manly avowal of our insolvency, and a composition with the public creditor; a measure which appears to me to be infinitely the best, and, in fact, the sole means of future prosperity. I have before observed that nations are but private families on an extended scale, and, after every effort of political casuistry, must at last be contented to be guided by the same rules. You have accumulated an amount of debt more than the sum of what the whole fee simple of the real property of the country would fetch at public auction, if put up to sale to-morrow. You have tried in vain every method of legitimate taxation, every means, vested in your power by the constitution, to discharge its interest. The only alternative then remaining is, either to violate the constitution, in order to keep your faith, or to compromise your faith, and preserve the constitution. There can be no scruple in such a choice, no hesitation in asserting that the latter is infinitely less criminal, and incalculably more politic and wise. And with respect to the question of public faith, it involves not one atom more of violation than has already been committed by the establishment of the tax we are now discussing; and will again be committed by making it a part of your permanent supply. A clear ten per cent has been annually withheld from the payment of the interest originally promised, and though it has been disguised under another name, yet it has been, in effect, a bona fide diminution of interest, and, if now perpetuated, will amount to the very same thing in principle with the measure I propose. Again, also, the public faith has not been less violated by your interference with the Sinking Fund, which stood directly pledged to the public creditor, as security for his debt.

The mode in which I conceive this compromise might be made, is nearly similar to that which was acted on by Mr. Pelham, in the year 1749, with a degree of success which astonished Europe, and the plan of which, when submitted to parliament, appeared so necessary and so eligible at that time, that it was carried through both Houses without a single division; not a shilling was withdrawn from the public debt, and the funds suffered not the slightest depression whatsoever. It will easily be remembered that the measure was simply a reduction of one per cent upon the whole National Debt, with the option of being paid off at par if required; and that it was adopted at a period not unlike the present, except that the exigency that led to it was infinitely less urgent, and that the interest which may now be made by money vested in the funds is almost doubled. 6

The difference in the value of stock is indeed very important, but then the different rate at which that stock must have been originally purchased is sufficient to meet the inequality. Out of the eleven hundred millions, now constituting our public debt, eight hundred millions have been borrowed since 1795, and probably three-fourths of the remainder bought and sold; during which period, I believe, the average price of the three per cents will be found to be considerably below 60, and of course the other kinds of stock in the same proportion. What then I should now propose would be to offer to the fund-holder, either to pay off the principal at the present market price, which is peculiarly favorable to both parties, or that he should submit to a reduction of ½ per cent interest; which I trust would be found a relief fully adequate to the public wants of the state. I am aware that, as the description of funded property is various, the same per centage cannot be equitably applied to the whole eleven hundred millions of which it is composed, but the modification is so obvious and easy, that I feel it unnecessary to go into details.

The reduction above alleged I should suppose would, when modified and equalized, still produce four millions, and the relief from the Income Tax would be naturally succeeded by an increased productiveness in other departments of taxation. Windows would again be opened that are now closed; the tax-cart without a cushion would then aspire to an accommodation so valuable and important; and that which already had one, would probably be still improved by the elastic motion of a spring; and the great aphorism of finance be exemplified, that the Treasury was rich because the taxation was not oppressive.

Nor with respect to the fund-holder, can I see how such a measure need be attended with alarm, nor complained of as one of peculiar hardship. He has chosen to advance his money, with his eyes perfectly open to the kind of security given him in return; he knows and feels that every means has been exhausted of paying the whole of his demand, which is at all compatible with the character of that constitution, under the protection indeed of which his property is vested, but yet amenable to its laws; and that, by insisting further on his claims, he is himself contributing to throw down an edifice, which it is an incalculably greater objet for him to preserve, than any consideration he can lose by the sacrifice required.

I have already shown that the present price at which he might resume his principal, is probably more than it originally cost him, and that his capital is therefore unimpaired. And if, on the other hand, he chose to allow it to remain, his security is improved by the improving solvency of the state, and the value of his principal increased by the certain prospect of increased prosperity to the country. In the reduction of the public burthens he will further find an additional compensation, which he will share in full proportion with the community at large; and if he receive less from government, he will have less to pay to it. He will free himself, his heirs, and successors, I hope, for ever, from a direct outgoing absolutely unlimited, and which, though now assessed at no more than ten or perhaps but five per cent nothing forbids hereafter to be augmented even to fifty. Again also by turning his view only to the depressed state of agriculture, and the depreciated value of land, together with the almost unprecedented stagnation of commerce and of trade, he will feel satisfied that he is, even then, in a much better relative situation than any other class of the community, and that he still hardly bears an equitable portion of the common suffering. All jealousy on that score will soon be dissipated; and in short, if he impartially reflects upon the limited sacrifices required, he will not fail readily to acquiesce in a measure which the public welfare seem so imperiously to call for.

On the part of government, again, I should conceive but little uneasiness need be apprehended. The superior confidence reposed in our stability over that of any other country, and on which the present measure can make but little impression; the situation of public affairs, the prospect of a long peace, and consequently that enormous loans are not to be contemplated, but, on the contrary, that the monied market will be more and more abundantly supplied, together with many other minor circumstances that might be mentioned, all most powerfully contribute to recommend it. But even supposing all these hopes to be salacious, and that some few individuals did conspire to obstruct its peaceful operation, or were really alarmed at such a step, what forbids the government to meet such a difficulty by a corresponding loan? Or, by some other of those financial arrangements which have often been applied to measures much less justifying their adoption? Perhaps even a gradual reduction would be found sufficiently effectual. In fact the variation of its interest, which has already been so repeatedly acted on, of late, in the case of its Exchequer Bills, must have gradually habituated the public mind to see such expedients resorted to; and when we add to this the impossibility of finding a better channel of employment for the capital withdrawn, and the conviction, that by shaking the ability of government they would be endangering whatever stake they themselves have in it, I cannot see any cause whatever for looking on such a scheme with serious alarm. I cannot help viewing it as infinitely preferable to any other, as less detrimental to the public welfare, and ultimately but little, if at all, injurious to the public creditor; as calculated to restore us to something like our former state, to rid us of unconstitutional, as well as oppressive, burthens, and by so doing, to promote commerce, to favor agriculture, to aid the extinction of our debt, and in short, to give us back Old England. With these impressions I cannot help clinging to such a scheme with fondness, until I am convinced of greater difficulties and dangers attending it than any with which I am yet acquainted. Let me now, however, be understood as speaking slightly of its character, or as insensible to the dangers of acting upon such precedents as these. I contemplate it as a measure of most dire but yet salutary necessity. As a choice of evils between the continuance of a tax, of which I have already shown the character and tendency to be destructive of the constitution itself, and the adoption of a scheme which involves, I readily admit, a violation of faith; but such a violation as has already been committed, and must again be committed, by the very adoption of the measure proposed in order to avoid it.

Lastly, let me not be censured, if unskilled in the intricacies of finance, I have rashly presumed to tread so dangerous a ground. Nor let me be thought inclined, by disposition or habit, to dabble in political discussions. This is the first upon which I ever ventured, and will probably be the last. But though merged in the depths of obscurity and retirement, and employed in duties still more solemn and important, yet I could not rest an unconcerned spectator of the passing scene; I could not, in a crisis such as this, forget that wise and salutary law of Athens, which decreed that man infamous and dishonoured, who remained neuter and indifferent when the liberties of his country were endangered.

Endnotes

1 Moral and Political Philosophy.

2 On the British Constitution.

3 This prophecy has already, since the first publication of these remarks, received, as far as relates to the intention of his majesty’s present ministers, its exact fulfillment. The Chancellor of the Exchequer has distinctly avowed his purpose of continuing the tax on its present footing at 5 per. Cent, for two or three years, and then to leave it to parliament to decide what part of it shall be made permanent.

4 Esprit des Lois.

5 I beg leave here to obviate an error which might possibly occur, viz. that I admitted a substitute for the Property Tax to be absolutely needful. Nothing is farther from my intention than to encourage such an idea. Supposing the net permanent revenue to be only adequate to discharge the interest of our public debt, yet the war taxes alone amount to 24 millions, and upon no principle of equity or justice, or policy, or prudence, can the peace establishment be admitted to require more than 10 millions. You might then have the whole military and naval establishment which Mr. Pitt thought needful in 1792, a period of infinitely greater external danger than the present; and besides this, you might have also the whole civil establishment as it now stands. The former branches then cost but four millions and a half, including ordnance, and cannot now, with the increase of pay and pensions added to it, demand more than six millions, and the latter, by the last returns, was but four millions more. You have, therefore, a relief of 14 remaining millions, the whole amount of the Property Tax, which the people of this country have an unquestionable right to look for and demand. But when I considered the depressed and suffering state of agriculture, and when I further considered how deeply every part of the laboring classes of the community were interested in the relief it would afford, I ventured to suggest the following scheme of reducing the interest of the debt, in the hope of its enabling us to dispense with the war-duty upon malt, upon horses used in husbandry, and some few other of those taxes which press most heavily upon us.

6 Mr. Malthus, in considering the comparative ratio of wealth, has justly remarked, that the fund-holder who vests his property so as to produce five per cent when corn is 100 shillings a quarter, receives an equivalent to 7, 8, or 9 per cent whenever the price of corn shall fall to 50 shillings. That day has now arrived.