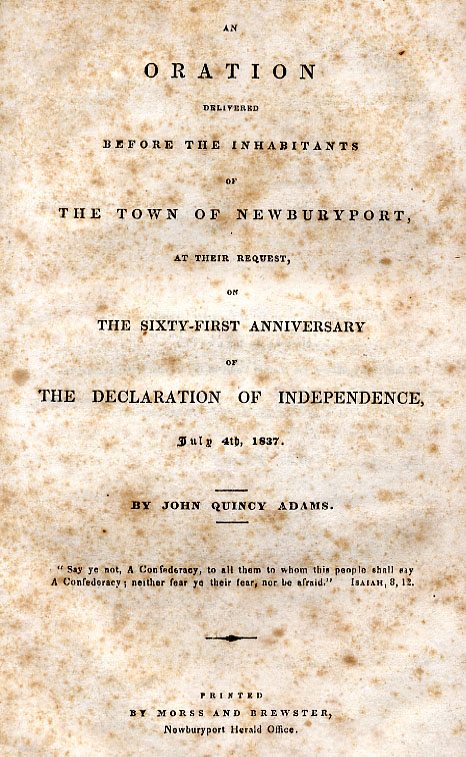

An

Oration

Delivered

Before the Inhabitants

of

the Town of Newburyport,

at their request,

on the Sixty-First Anniversary

of

theDeclaration of Independence,

July 4th, 1837.

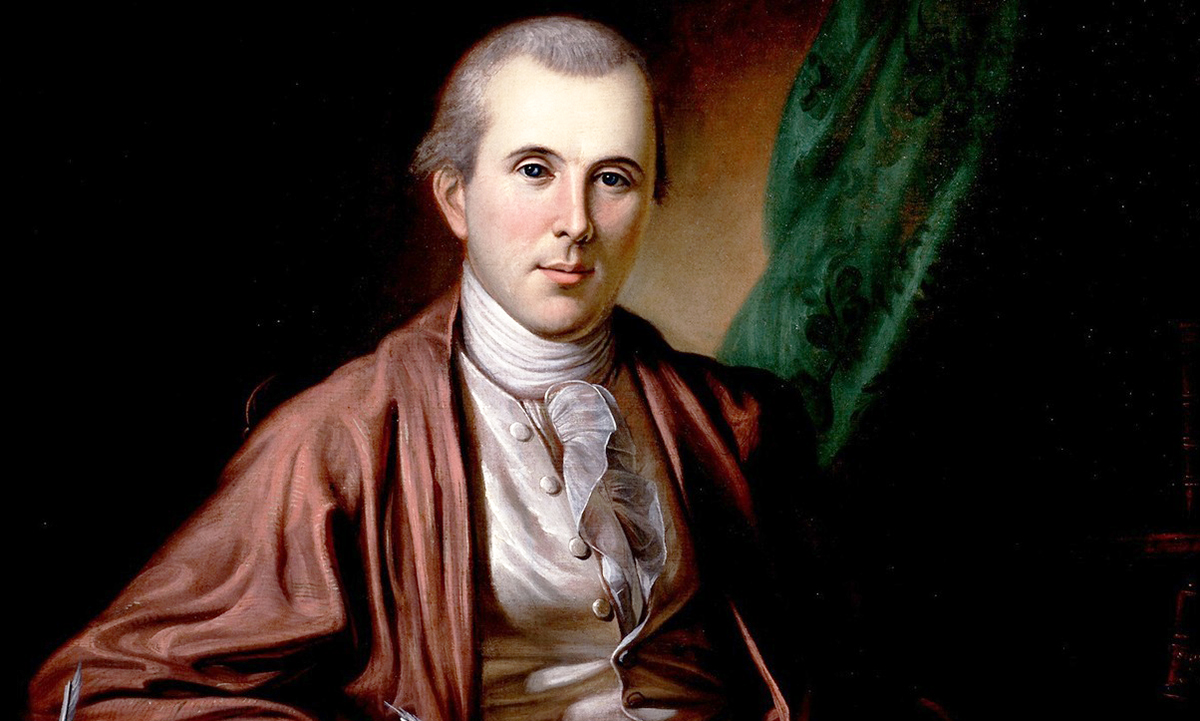

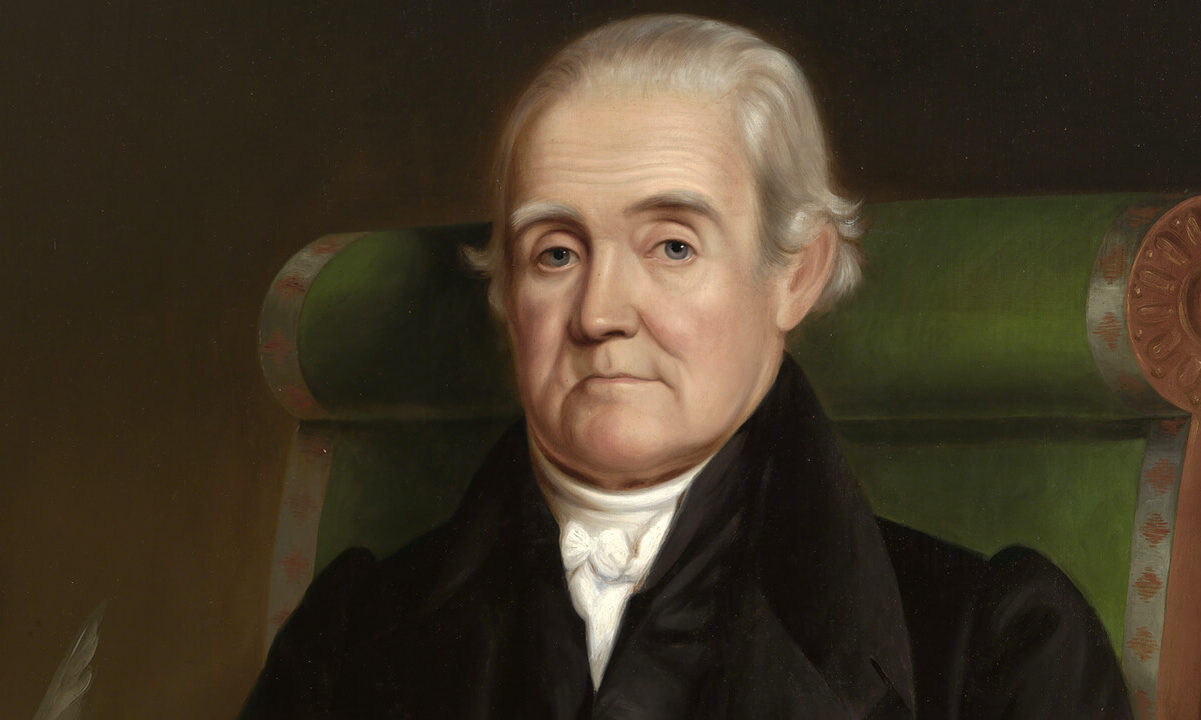

By John Quincy Adams.

“Say ye not, A Confederacy, to all them to whom this people shall say A Confederacy; neither fear ye their fear, nor be afraid.” Isaiah 8:12.

ORATION.Why is it, Friends and Fellow Citizens, that you are here assembled? Why is it, that, entering upon the sixty-second year of our national existence, you have honored with an invitation to address you from this place, a fellow citizen of a former age, bearing in the records of his memory, the warm and vivid affections which attached him, at the distance of a full half century, to your town, and to your forefathers, then the cherished associates of his youthful days? Why is it that, next to the birthday of the Savior of the World, your most joyous and most venerated festival returns on this day? – And why is it that, among the swarming myriads of our population, thousands and tens of thousands among us, abstaining, under the dictate of religious principle, from the commemoration of that birth-day of Him, who brought life and immortality to light, yet unite with all their brethren of this community, year after year, in celebrating this, the birth-day of the nation? Is it not that, in the chain of human events, the birthday of the nation is indissolubly linked with the birthday of the Savior? That it forms a leading event in the progress of the gospel dispensation?

Is it not that the Declaration of Independence first organized the social compact on the foundation of the Redeemer’s mission upon earth? That it laid the corner stone of human government upon the first precepts of Christianity, and gave to the world the first irrevocable pledge of the fulfillment of the prophecies, announced directly from Heaven at the birth of the Savior and predicted by the greatest of the Hebrew prophets six hundred years before? Cast your eyes backwards upon the progress of time, sixty-one years from this day; and in the midst of the horrors and desolations of civil war, you behold an assembly of Planters, Shopkeepers and Lawyers, the Representatives of the People of thirteen English Colonies in North America, sitting in the City of Philadelphia. These fifty-five men, on that day, unanimously adopt and publish to the world, a state paper under the simple title of ‘A DECLARATION.’

The object of this Declaration was two-fold. First, to proclaim the People of the thirteen United Colonies, one People, and in their name, and by their authority, to dissolve the political bands which had connected them with another People, that is, the People of Great Britain. Secondly, to assume, in the name of this one People, of the thirteen United Colonies, among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station, to which the Laws of Nature, and of Nature’s God, entitled them. With regard to the first of these purposes, the Declaration alleges a decent respect to the opinions of mankind, as requiring that the one people, separating themselves from another, should declare the causes, which impel them to the separation. – The specification of these causes, and the conclusion resulting from them, constitute the whole paper. The Declaration was a manifesto, issued from a decent respect of the opinions of mankind, to justify the People of the North American Union, for their voluntary separation from the People of Great Britain, by alleging the causes which rendered this separation necessary. The Declaration was, thus far, merely an occasional state paper, issued for a temporary purpose, to justify, in the eyes of the world, a People, in revolt against their acknowledged Sovereign, for renouncing their allegiance to him, and dissolving their political relations with the nation over which he presided. For the second object of the Declaration, the assumption among the powers of the earth of the separate and equal station, to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitled them, no reason was assigned, – no justification was deemed necessary.

The first and chief purpose of the Declaration of Independence was interesting to those by whom it was issued, to the people, their constituents in whose name it was promulgated, and to the world of mankind to whom it was addressed, only during that period of time, in which the independence of the newly constituted people was contested, by the wager of battle. Six years of War, cruel, unrelenting, merciless War, – War, at once civil and foreign, were waged, testing the firmness and fortitude of the one People, in the inflexible adherence to that separation from the other, which their Representatives in Congress had proclaimed. By the signature of the Preliminary Articles of Peace, on the 30th of November 1782, their warfare was accomplished, and the Spirit of the Lord, with a voice reaching to the latest of future ages, might have exclaimed, like the sublime prophet of Israel, – Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God [Isaiah 40:1]. But, from that day forth, the separation of the one People from the other was a solitary fact in their common history; a mere incident in the progress of human events, not more deserving of special and annual commemoration by one of the separated parts, than by the other. Still less were the causes of the separation subjects for joyous retrospection by either of the parties. – The causes were acts of misgovernment committed by the King and Parliament of Great Britain. In the exasperation of the moment they were alleged to be acts of personal tyranny and oppression by the King.

George the third was held individually responsible for them all. The real and most culpable oppressor, the British Parliament, was not even named in the bill of pains and penalties brought against the monarch. – They were described only as “others” combined with him; and, after a recapitulation of all the grievances with which the Colonies had been afflicted by usurped British Legislation, the dreary catalogue was closed by the sentence of unqualified condemnation, that a prince, whose character was thus marked by every act which might define a tyrant, was unworthy to be the ruler of a free people. The King, thus denounced by a portion of his subjects, casting off their allegiance to his crown, has long since gone to his reward. His reign was long, and disastrous to his people, and his life presents a melancholy picture of the wretchedness of all human grandeur; but we may now, with the candor of impartial history, acknowledge that he was not a tyrant. His personal character was endowed with many estimable qualities. His intentions were good; his disposition benevolent; his integrity unsullied; his domestic virtues exemplary; his religious impressions strong and conscientious; his private morals pure; his spirit munificent, in the promotion of the arts, literature and sciences; and his most fervent wishes devoted to the welfare of his people. But he was born to be a hereditary king, and to exemplify in his life and history the irremediable vices of that political institution, which substitutes birth for merit, as the only qualification for attaining the supremacy of power. George the third believed that the Parliament of Great Britain had the right to enact laws for the government of the people of the British Colonies in all cases. An immense majority of the people of the British Islands believed the same. That people were exclusively the constituents of the British House of Commons, where the project of taxing the people of the Colonies for a revenue originated; and where the People of the Colonies were not represented. The purpose of the project was to alleviate the burden of taxation bearing upon the people of Britain, by levying a portion of it upon the people of the Colonies. – At the root of all this there was a plausible theory of sovereignty, and unlimited power in Parliament, conflicting with the vital principle of English Freedom, that taxation and representation are inseparable, and that taxation without representation is a violation of the right of property. Here was a conflict between two first principles of government, resulting from a defect in the British Constitution: the principle that sovereign power in human Government is in its nature unlimited: and the principle that property can lawfully be taxed only with the consent of its owner.

Now these two principles, carried out into practice, are utterly irreconcilable with each other. The lawyers of Great Britain held them both to be essential principles of the British Constitution. – In their practical application, the King and Parliament and people of Great Britain, appealed for the right to tax the Colonies to the unlimited and illimitable sovereignty of the Parliament. – The Colonists appealed to the natural right of property, and the articles of the Great Charter. The collision in the application of these two principles was the primitive cause of the severance of the North American Colonies, from the British Empire. The grievances alleged in the Declaration of Independence were all secondary causes, amply sufficient to justify before God and man the separation itself; and that resolution, to the support of which the fifty-five Representatives of the One People of the United Colonies pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, after passing through the fiery ordeal of a six years war, was sanctioned by the God of Battles, and by the unqualified acknowledgment of the defeated adversary.

This, my countrymen, was the first and immediate purpose of the Declaration of Independence. It was to justify before the tribunal of public opinion, throughout the world, the solemn act of separation of the one people from the other. But this is not the reason for which you are here assembled. The question of right and wrong involved in the resolution of North American Independence was of transcendent importance to those who were actors in the scene. A question of life, of fortune, of fame, of eternal welfare. To you, it is a question of nothing more than historical interest. The separation itself was a painful and distressing event; a measure resorted to by your forefathers with extreme reluctance, and justified by them, in their own eyes, only as a dictate of necessity. – They had gloried in the name of Britons: It was a passport of honor throughout the civilized world. They were now to discard it forever, with all its tender and all its generous sympathies, for a name obscure and unknown, the honest fame of which was to be achieved by the gallantry of their own exploits and the wisdom of their own counsels. But, with the separation of the one people from the other, was indissolubly connected another event. They had been British Colonies, – distinct and separate subordinate portions of one great community. In the struggle of resistance against one common oppressor, by a moral centripetal impulse they had spontaneously coalesced into One People. They declare themselves such in express terms by this paper. – The members of the Congress, who signed their names to the Declaration, style themselves the Representatives, not of the separate Colonies, but of the United States of America in Congress assembled. No one Colony is named in the Declaration, nor is there any thing on its face, indicating from which of the Colonies, any one of the signers was delegated. They proclaim the separation of one people from another. – They affirm the right of the People, to institute, alter, and abolish their Government: – and their final language is, “we do, in the name, and by the authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare that these United Colonies, are and of right ought to be FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES.”

The Declaration was not, that each of the States was separately Free and Independent, but that such was their united condition. And so essential was their union, both in principle and in fact, to their freedom and independence, that, had one of the Colonies seceded from the rest, and undertaken to declare herself free and independent, she could have maintained neither her independence nor her freedom. And, by this paper, this One People did notify the world of mankind that they thereby did assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station, to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitled them. This was indeed a great and solemn event. The sublimest of the prophets of antiquity with the voice of inspiration had exclaimed, “Who hath heard such a thing? Who hath seen such things? Shall the earth be made to bring forth in one day? Or shall a nation be born at once?” [Isaiah 66:8]. In the two thousand five hundred years, that had elapsed since the days of that prophecy, no such event had occurred. It had never been seen before. In the annals of the human race, then, for the first time, did one People announce themselves as a member of that great community of the powers of the earth, acknowledging the obligations and claiming the rights of the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God. The earth was made to bring forth in one day! A nation was born at once! Well, indeed, may such a day be commemorated by such a Nation, from year to year!

But whether as a day of festivity and joy, or of humiliation and mourning, – that, fellow-citizens, – that in the various turns of chance below, depends not upon the event itself, but upon its consequences; and after threescore years of existence, not so much upon the responsibilities of those who brought the Nation forth, as upon the moral, political and intellectual character of the present generation, – of yourselves. In the common intercourse of social life, the birth-day of individuals is often held as a yearly festive day by themselves, and their immediate relatives; yet, as early as the age of Solomon, that wisest of men told the people of Jerusalem, that, as a good name was better than precious ointment, so the day of death was better than the day of one’s birth [Ecclesiastes 7:1]. Are you then assembled here, my brethren, children of those who declared your National Independence, in sorrow or in joy? In gratitude for blessings enjoyed, or in affliction for blessings lost? In exultation at the energies of your fathers, or in shame and confusion of face at your own degeneracy from their virtues? Forgive the apparent rudeness of these enquiries: – they are not addressed to you under the influence of a doubt what your answer to them will be. You are not here to unite in echoes of mutual gratulation for the separation of your forefathers from their kindred freemen of the British Islands. You are not here even to commemorate the mere accidental incident, that, in the annual revolution of the earth in her orbit round the sun, this was the birthday of the Nation.

You are here, to pause a moment and take breath, in the ceaseless and rapid race of time; – to look back and forward; – to take your point of departure from the ever memorable transactions of the day of which this is the anniversary, and while offering your tribute of thanksgiving to the Creator of all worlds, for the bounties of his Providence lavished upon your fathers and upon you, by the dispensations of that day, and while recording with filial piety upon your memories, the grateful affections of your hearts to the good name, the sufferings, and the services of that age, to turn your final reflections inward upon yourselves, and to say: – These are the glories of a generation past away, – what are the duties which they devolve upon us? The Declaration if Independence, in announcing to the world of mankind, that the People comprising the thirteen British Colonies on the continent of North America assumed, from that day, as One People, their separate and equal station among the powers of the earth, explicitly unfolded the principles upon which their national association had, by their unanimous consent, and by the mutual pledges of their faith, been formed.

It was an association of mutual covenants. Every intelligent individual member of that self-constituted People did, by his representative in Congress, the majority speaking for the whole, and the husband and parent for the wife and child, bind his and their souls to a promise, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of his intentions, covenanting with all the rest that they would for life and death be faithful members of that community, and bear true allegiance to that Sovereign, upon the principles set forth in that paper. The lives, the fortunes, and the honour, of every free human being forming a part of those Colonies, were pledged, in the face of God and man, to the principles therein promulgated. My countrymen! – the exposition of these principles will furnish the solution to the question of the purpose for which you are here assembled. In recurring to those principles, let us remark, First, that the People of the thirteen Colonies announced themselves to the world, and solemnly bound themselves, with an appeal to God, to be One People. And this One People, by their Representatives, declared the United Colonies free and independent States. Secondly, they declared the People, and not the States, to be the only legitimate source of power; and that to the People alone belonged the right to institute, to alter, to abolish, and to re-institute government. And hence it follows, that as the People of the separate Colonies or States formed only parts of the One People assuming their station among the powers of the earth, so the People of no one State could separate from the rest, but by a revolution, similar to that by which the whole People had separated themselves from the People of the British Islands, nor without the violation of that solemn covenant, by which they bound themselves to support and maintain the United Colonies, as free and independent States.

An error of the most dangerous character, more than once threatening the dissolution by violence of the Union itself, has occasionally found countenance and encouragement in several of the States, by an inference not only unwarranted by the language and import of the Declaration, but subversive of its fundamental principles. This inference is that because by this paper the United Colonies were declared free and independent States, therefore each of the States, separately, was free, independent and sovereign. The pernicious and fatal malignity of this doctrine consists, not in the mere attribution of sovereignty to the separate States; for within their appropriate functions and boundaries they are sovereign; – but in adopting that very definition of sovereignty, which had bewildered the senses of the British Parliament, and which rent in twain the Empire; – that principle, the resistance to which was the vital spark of the American revolutionary cause, namely, that sovereignty is identical with unlimited and illimitable power. The origin of this error was of a very early date after the Declaration of Independence, and the infusion of its spirit into the Articles of Confederation, first formed for the government of the Union, was the seed of dissolution sown in the soil of that compact, which palsied all its energies from the day of its birth, and exhibited it to the world only as a monument of impotence and imbecility. The Declaration did not proclaim the separate States free and independent; much less did it announce them as sovereign States, or affirm that they separately possessed the war-making or the peace-making power. The fact was directly the reverse.

The Declaration was, that the United Colonies, forming one People, were free and independent States; that they were absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown; that all political connection, between them and the State of Great Britain, was and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as free and independent States, they had full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and do all other acts and things, which independent States may of right do. But all this was affirmed and declared not of the separate, but of the United, States. And so far was it from the intention of that Congress, or of the One People whom- they represented, to declare that all the powers of sovereignty were possessed by the separate States, that the specification of the several powers of levying war, concluding peace, contracting alliances, and establishing commerce, was obviously introduced as the indication of powers exclusively possessed by the one People of the United States, and not appertaining to the People of each of the separate States. This distinction was indeed indispensable to the necessities of their condition. The Declaration was issued in the midst of a war, commenced by insurrection against their common sovereign, and until then raging as a civil war. Not the insurrection of one of the Colonies; not the insurrection of the organized government of any one of the Colonies; but the insurrection of the People of the whole thirteen. The insurrection was one. The civil war was one. In constituting themselves one People, it could not possibly be their intention to leave the power of concluding peace to each of the States of which the Union was composed. The war was waged against all.

The war itself had united the inhabitants of the thirteen Colonies into one People. The lyre of Orpheus [Orpheus was, in Greek mythology, the son of the river god Oiagros and the Muse Calliope (the muse of epic poetry) and was called “the father of songs.” He was also considered to be the perfector of the lyre.] was the standard of the Union. By the representatives of that one People and by them alone, could the peace be concluded. Had the people of any one of the States pretended to the right of concluding a separate peace, the very fact would have operated as a dismemberment of the Union, and could have been carried into effect only by the return of that portion of the People to the condition of British subjects. Thirdly, the Declaration of Independence announced the One People, assuming their station among the powers of the earth, as a civilized, religious, and Christian People, – acknowledging themselves bound by the obligations, and claiming the rights, to which they were entitled by the laws of Nature and of Nature’s God. They had formed a subordinate portion of an European Christian nation, in the condition of Colonies. The laws of social intercourse between sovereign communities constitute the laws of nations, all derived from three sources: – the laws of nature, or in other words the dictates of justice; usages, sanctioned by custom; and treaties, or national covenants. Superadded to these, the Christian nations, between themselves, admit, with various latitudes of interpretation, and little consistency of practice, the laws of humanity and mutual benevolence taught in the gospel of Christ.

The European Colonies in America had all been settled by Christian nations; and the first of them, settled before the reformation of Luther, had sought their justification for taking possession of lands inhabited by men of another race, in a grant of authority from the successor of Saint Peter at Rome, for converting the natives of the country to the Christian code of religion and morals. After the reformation, the kings of England, substituting themselves in the place of the Roman Pontiff, as heads of the Church, granted charters for the same benevolent purposes; and as these colonial establishments successively arose, worldly purposes, the spirit of adventure, and religious persecution took their place, together with the conversion of the heathen, among the motives for the European establishments in this Western Hemisphere. Hence had arisen among the colonizing nations, a customary law, under which the commerce of all colonial settlements was confined exclusively to the metropolis or mother country. The Declaration of Independence cast off all the shackles of this dependency. The United States of America were no longer Colonies. They were an independent Nation of Christians, recognizing the general principles of the European law of nations. But to justify their separation from the Parent State, it became necessary for them to set forth the wrongs which they had endured. Their colonial condition had been instituted by charters from British kings. These they considered as compacts between the king as their sovereign and them as his subjects. In all these charters, there were stipulations for securing to the colonists the enjoyment of the rights of natural born Englishmen. The attempt to tax them by Act of Parliament, to sustain their right of taxing the Colonies had appealed to the prerogative of sovereign power, the colonists, to refute that claim, after appealing in vain to their charters, and to the Great Charter of England, were obliged to resort to the natural rights of mankind; – to the laws of Nature and Nature’s God.

And now, my friends and fellow citizens, have we not reached the cause of your assemblage here? Have we not ascended to the source of that deep, intense, and never-fading interest, which, to your fathers, from the day of the issuing of this Declaration, – to you, on this sixty-first anniversary after that event, – and to your children and theirs of the fiftieth generation, – has made and will continue to make it the first and happiest of festive days? In setting forth the justifying causes of their separation from Great Britain, your fathers opened the fountains of the great deep. For the first time since the creation of the world, the act, which constituted a great people, laid the foundation of their government upon the unalterable and eternal principles of human rights.

They were comprised in a few short sentences, and were delivered with the unqualified confidence of self-evident truths. “We hold,” says the Declaration, “these truths to be self-evident: – that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new government, laying its foundations on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.” It is afterwards stated to be the duty of the People, when their governments become incorrigibly oppressive, to throw them off, and to provide new guards for their future security; and it is alleged that such was the condition of the British Colonies at that time, and that they were constrained by necessity to alter their systems of government.

The origin of lawful government among men had formed a subject of profound investigation and of ardent discussion among the philosophers of ancient Greece. The theocratic government of the Hebrews had been founded upon a covenant between God and man; a law, given by the Creator of the world, and solemnly accepted by the people of Israel. It derived all its powers, therefore, from the consent of the governed, and gave the sanction of Heaven itself to the principle, that the consent of the governed is the only legitimate source of authority to man over man. But the history of mankind had never before furnished an example of a government directly and expressly instituted upon this principle. The associations of men, bearing the denomination of the People, had been variously formed, and the term itself was of very indefinite signification. In the most ordinary acceptation of the word, a people, was understood to mean a multitude of human beings united under one supreme government, and one and the same civil polity. But the same term was equally applied to subordinate divisions of the same nation; and the inhabitants of every province, county, city, town, or village, bore the name, as habitually as the whole population of a kingdom or an empire. In the theories of government, it was never imagined that the people of every hamlet or subordinate district of territory should possess the power of constituting themselves and independent State; yet are they justly entitled to the appellation of people, and to exemption from all authority derived from any other source than their own consent, express or implied.

The Declaration of Independence constituted all the inhabitants of European descent in the thirteen English Colonies of North America, one People, with all the attributes of rightful sovereign power. They had, until then, been ruled by thirteen different systems of government; none of them sovereign; but all subordinate to one sovereign, separated from them by the Atlantic Ocean. The Declaration of Independence altered these systems of government, and transformed these dependant Colonies into united, free, and independent States. The distribution of the sovereign powers of government, between the body representing the whole People, and the municipal authorities substituted for the colonial governments, was left for after consideration. The People of each Colony, absolved by the People of the whole Union from their allegiance to the British crown, became themselves, upon the principles of the Declaration, the sovereigns to institute and organize new systems of government, to take the place of those which had been abolished by the will of the whole People, as proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence. It will be remembered, that, until that time, the whole movement of resistance against the usurpations of the British government had been revolutionary, and therefore irregular. The colonial governments were still under the organization of their charters, except that of Massachusetts-Bay, which had been formally vacated, and the royal government was administered by a military commander and regiments of soldiers. The country was in a state of civil war. The people were in revolt, claiming only the restoration of their violated rights as subjects of the British king. The members of the Congress had been elected by the Legislative assemblies of the Colonies, or by self-constituted popular conventions or assemblies, in opposition to the Governors. Their original mission had been to petition, to remonstrate; to disclaim all intention or purpose of independence; to seek, with earnest entreaty, the redress of grievances, and reconciliation with the parent State. They had received no authority, at their first appointment, to declare independence, or to dissolve the political connection between the Colonies and Great Britain. But they had petitioned once and again, and their petitions had been slighted. They had remonstrated, and their remonstrances had been contemned. They had disclaimed all intention of independence, and their disclaimer had been despised. They had finally recommended to the People to look for their redemption to themselves, and they had been answered by voluntary and spontaneous calls for independence. They declared it, therefore, in the name and by the authority of the People, and their declaration was confirmed from New Hampshire to Georgia with one universal shout of approbation. And never, from that to the present day, has there been one moment of regret, on the part of the People, whom they thus declared independent, at this mighty change of their condition, nor one moment of distrust, of the justice of that declaration.

In the mysterious ways of Providence, manifested by the course of human events, the feeble light of reason is often at a loss to discover the coincidence between the laws of eternal justice, and the decrees of fortune or of fate in the affairs of men. In the corrupted currents of this world, not only is the race not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong [Ecclesiastes 9:11], but the heart is often wrung with anguish at the sight of the just man that perisheth in his righteousness, and of the wicked man that prolongeth his life in his wickedness [Ecclesiastes 7:15]. Far different and happier is the retrospect upon that great and memorable transaction. Every individual, whose name was affixed to that paper, has finished his career upon earth; and who, at this day would not deem it a blessing to have had his name recorded on that list? The act of abolishing the government under which they had lived, – of renouncing and abjuring the allegiance by which they had been bound, – of dethroning their sovereign, and of discarding their country herself, – purified and elevated by the principles which they proclaimed, and by the motives which they promulgated as their stimulants to action, – stands recorded in the annals of the human race, as one among the brightest achievements of human virtue: – applauded on earth, ratified and confirmed by the fiat of Heaven. The principles, thus triumphantly proclaimed and established, were the natural and unalienable rights of man, and the supreme authority of the People, as the only legitimate source of power in the institution of civil government. But let us not mistake the extent, nor turn our eyes from the limitation necessary for the application, of the principles themselves.

Who were the People, thus invested by the laws of Nature and of Nature’s God, with sovereign powers? And what were the sovereign powers thus vested in the People? First, the whole free People of the thirteen United British Colonies in North America. The Declaration was their act; prepared by their Representatives; in their name, and by their authority. An act of the most transcendent sovereignty; abolishing the governments of thirteen Colonies; absolving their inhabitants from the bands of their allegiance, and declaring the whole People of the British Islands, theretofore their fellow subjects and countrymen, aliens and foreigners. Secondly, the free People of each of the thirteen Colonies, thus transformed into united, free, and independent States. Each of these formed a constituent portion of the whole People; and it is obvious that the power acknowledged to be in them could neither be co-extensive, nor inconsistent with, that rightfully exercised by the whole People. In absolving the People of the thirteen United Colonies from the bands of their allegiance to the British crown, the Congress, representing the whole People, neither did nor could absolve them, or any on individual among them, from the obligation of any other contract by which he had been previously bound. They neither did nor could, for example, release any portion of the People from the duties of private and domestic life. They could not dissolve the relations of husband and wife; of parent and child; of guardian and ward; of master and servant; of partners in trade; of debtor and creditor; – nor by the investment of each of the Colonies with sovereign power could they bestow upon them the power of dissolving any of those relations, or of absolving any one of the individual citizens of the Colony from the fulfillment of all the obligations resulting from them. The sovereign authority, conferred upon the People of the Colonies by the Declaration of Independence, could not dispense them, nor any individual citizen of them, from the fulfillment of all their moral obligations; for to these they were bound by the laws of Nature’s God; nor is there any power upon earth capable of granting absolution from them.

The People, who assumed their equal and separate station among the powers of the earth by the laws of Nature’s God, by that very act acknowledged themselves bound to the observance of those laws, and could neither exercise nor confer any power inconsistent with them. The sovereign authority, conferred by the Declaration of Independence upon the people of each of the Colonies, could not extend to the exercise of any power inconsistent with that Declaration itself. It could not, for example, authorize any one of the United States to conclude a separate peace with Great Britain; to connect itself as a Colony with France, or any other European power; to contract a separate alliance with any other State of the Union; or separately to establish commerce. These are all acts of sovereignty, which the Declaration of Independence affirmed the United States were competent to perform, but which for that very reason were necessarily excluded from the powers of sovereignty conferred upon each of the separate States. The Declaration itself was at once a social compact of the whole People of the Union, embracing thirteen distinct communities united in one, and a manifesto proclaiming themselves to the world of mankind, as one Nation, possessed of all attributes of sovereign power. But this united sovereignty could not possibly consist with the absolute sovereignty of each of the separate States.

“That were to make Strange contradiction, which to God himself Impossible is held, as argument of weakness, not of power.” [Quoted from Milton’s Paradise Lots (London: S. Simmons, 1674), Book 10.]

The position, thus assumed by this one People consisting of thirteen free and independent States, was new in the history of the world. It was complicated and compounded of elements never before believed susceptible of being blended together. The error of the British Parliament, the proximate cause of the Revolution, that sovereignty was in its nature unlimited and illimitable, taught as a fundamental doctrine by all the English lawyers, was too deeply imprinted upon the minds of the lawyers of our own country to be eradicated, even by the civil war, which it had produced. The most celebrated British moralist of the age, Dr. Samuel Johnson, in a controversial tract on the dispute between Britain and her Colonies, had expressly laid down as the basis of his argument, that:

“All government is essentially absolute. That in sovereignty there are no gradations. That there may be limited royalty; there may be limited consulship; but there can be no limited government. There must in every society be some power or other from which there is no appeal; which admits no restrictions; which pervades the whole mass of the community; regulates and adjusts all subordination; enacts laws or repeals them; erects or annuls judicatures; extends or contracts privileges; exempts itself from question or control; and bounded only by physical necessity.” [Johnson’s Taxation no Tyranny (1775).]

The Declaration of Independence was founded upon the direct reverse of all these propositions. It did not recognize, but implicitly denied, the unlimited nature of sovereignty. By the affirmation that the principal natural rights of mankind are unalienable, it placed them beyond the reach of organized human power; and by affirming that governments are instituted to secure them, and may and ought to be abolished if they become destructive of those ends, they made all government subordinate to the moral supremacy of the People. The Declaration itself did not even announce the States as sovereign, but as united, free and independent, and having power to do all acts and things which independent States may of right do. It acknowledged, therefore, a rule of right, paramount to the power of independent States itself, and virtually disclaimed all power to do wrong. This was a novelty in the moral philosophy of nations, and it is the essential point of difference between the system of government announced in the Declaration of Independence, and those systems which had until then prevailed among men.

A moral Ruler of the universe, the Governor and Controller of all human power, is the only unlimited sovereign acknowledged by the Declaration of Independence; and it claims for the United States of America, when assuming their equal station among the nations of the earth, only the power to do all that may be done of right. Threescore and one years have passed away, since this Declaration was issued, and we may now judge of the tree by its fruit. It was a bold and hazardous step, when considered merely as the act of separation of the Colonies from Great Britain. Had the cause in which it was issued failed, it would have subjected every individual who signed it to the pains and penalties of treason, to a cruel and ignominious death. But, inflexible as were the spirits, and intrepid as were the hearts of the patriots, who by this act set at defiance the colossal power of the British Empire, bolder and more intrepid still were the souls, which, at that crisis in human affairs, dared to proclaim the new and fundamental principles upon which their incipient Republic was to be founded. It was an experiment upon the heart of man. All the legislators of the human race, until that day, had laid the foundations of all government among men in power; and hence it was, that, in the maxims of theory, as well as in the practice of nations, sovereignty was held to be unlimited and illimitable. The Declaration of Independence proclaimed another law. A law of resistance against sovereign power, when wielded for oppression. A law ascending the tribunal of the universal lawgiver and judge. A law of right, binding upon nations as well as individuals, upon sovereigns as well as upon subjects. By that law the colonists had resisted their sovereign. By that law, when that resistance had failed to reclaim him to the rule of right, they renounced him, abjured his allegiance, and assumed the exercise of rightful sovereignty themselves. But, in assuming the attributes of sovereign power, they appealed to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of their intentions, and neither claimed nor conferred authority to do any thing but of right. Of the war with Great Britain, by which the independence thus declared was maintained, and of the peace by which it was acknowledged, it is unnecessary to say more.

The war was deeply distressing and calamitous, and its most instructive lesson was to teach the new confederate Republic the inestimable value of the blessings of peace. When the peace came, all controversy with Great Britain, with regard to the principles upon which the Declaration of Independence had been issued, was terminated, and ceased forever. The main purpose for which it had been issued was accomplished. No idle exultation of victory was worthy of the holy cause in which it had been achieved. No ungenerous triumph over the defeat of a generous adversary was consistent with the purity of the principles upon which the strife had been maintained. Had that contest furnished the only motives for the celebration of the day, its anniversary should have ceased to be commemorated, and the Fourth of July would thenceforward have passed unnoticed from year to year, scarcely numbered among the dies fasti [Latin for the days on which law business was allowed to be transacted, these days are part of the Fasti Diumi (the official year book of Rome included directions and dates for religious ceremonies, court days, and more).]of the Nation. But the Declaration of Independence had abolished the government of the thirteen British Colonies in North America. A new government was to be instituted in its stead.

A task more trying had devolved upon the People of the Union than the defense of their country against foreign armies; a duty more arduous than that of fighting the battles of the Revolution. The elements and the principles for the formation of the new government were all contained in the Declaration of Independence; but the adjustment of them to the condition of the parties to the compact was a work of time, of reflection, of experience, of calm deliberation, of moral and intellectual exertion; for those elements were far from being homogeneous, and there were circumstances in the condition of the parties, far from conformable to the principles proclaimed. The Declaration had laid the foundation of all civil government, in the unalienable natural rights of individual man, of which it had specifically named three: – life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, – declaring them to be among others not enumerated. The revolution had been exclusively popular and democratic, and the Declaration had announced that the only object of the institution of governments among men was to secure their unalienable rights, and that they derived their just powers from the consent of the governed. The Declaration proclaimed the parties to the compact as one People, composed of united Colonies, thenceforward free and independent States, constrained by necessity to alter their former systems of government. It would seem necessarily to follow from these elements and these principles, that the government for the whole People should have been instituted by the whole People, and the government of each of the independent States by the People of that State.

But obvious as that conclusion is, it is nevertheless equally true, that it has not been wholly accomplished even to this day. On the tenth of May preceding the day of the Declaration, the Congress had adopted a resolution, which may be considered as the herald to that Independence. After its adoption it was considered of such transcendent importance, that a special committee of three members was appointed to prepare a preamble to it. On the fifteenth of May this preamble was reported, adopted, and ordered to be published, with the resolution, which had been adopted on the tenth. The preamble and resolution are in the following words:

“Whereas his Britannic Majesty, in conjunction with the Lords and Commons of Great Britain, has, by a late Act of Parliament, excluded the inhabitants of these United Colonies from the protection of his crown; and whereas no answer whatever to the humble petitions of the Colonies, for redress of grievances and reconciliation with Great Britain, has been or is likely to be given, but the whole course of that kingdom, aided by foreign mercenaries, is to be exerted for the destruction of the good people of these Colonies; and whereas it appears absolutely irreconcilable to reason and good conscience for the people of these Colonies now to take the oaths and affirmations necessary for the support of any government under the crown of Great Britain, and it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed, and all the powers of government exerted under the authority of the people of the Colonies, for the preservation of internal peace, virtue, and good order, as well as for the defense of their lives, liberties, and properties, against the hostile invasions and cruel depredations of their enemies: – Therefore, Resolved,

“That it be recommended to the respective assemblies and conventions of the United Colonies, where no government sufficient to the exigencies of their affairs hath been hitherto established, to adopt such government as shall, in the opinion of the Representatives of the People, best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular, and America in general.”

The People of some of the Colonies had not waited for this recommendation, to assume all the powers of their internal government into their own hands. In some of them, the governments constituted by the royal charters were continued without alteration; or with the mere divestment of the portion of the public authority, exercised by the crown. In others, constitutions had been adopted, or were in preparation by representative popular conventions. Massachusetts was represented by a Provincial Congress, elected by the people as the General Court had been under the royal charter, and from that assembly the general Congress had been urgently invoked, for their advice in the formation of a government adapted to the emergency, and unshackled by transatlantic dependence. The institution of civil government by the authority of ‘the People, in each of the separate Colonies, was thus universally recognized as resulting from the dissolution of their allegiance to the British crown. But, that the union could be cemented and the national powers of government exercised of right, only by a constitution of government emanating from the whole People, was not yet discovered.

The powers of the Congress then existing, were revolutionary and undefined; limited by no constitution; responsible to no common superior; dictated by the necessities of a death-struggle for freedom; and embracing all discretionary means to organize and maintain the resistance of the people of all the Colonies against the oppression of the British Parliament. In devising measures for giving permanence, and, as far as human wisdom could provide, perpetuity, to the Union which had been formed by the common sufferings and dangers of the whole People, they universally concluded that a confederation would suffice; and that a confederation could be instituted by the authority of the States, without the intervention of the People. On the twenty-first of July, 1775, nearly a year before the Declaration of Independence, a sketch of articles of confederation, and contingently perpetual union, had been presented to Congress by Doctor Franklin, for a confederacy, to be styled the United Colonies of North America. It was proposed that this confederacy should continue until a reconciliation with Great Britain should be effected, and only on failure of such reconciliation, to be perpetual.

This project, contemplated only a partnership of Colonies to accomplish their common re-subjugation to the British crown. It made no provision for a community of independent States, and was encumbered with no burden of sovereignty. No further action upon the subject was had by Congress, till the eleventh of June, 1776. Four days before this, that is, on the seventh of June, certain resolutions respecting independency had been moved and seconded. They were on the next day referred to a committee of the whole, and on Monday, the tenth of June, they were agreed to in the committee of the whole and reported to the Congress. The first of these resolutions was that of independence. The second was, that a committee be appointed to prepare and digest the form of a confederation, to be entered into between these Colonies. The third, that a committee be appointed to prepare a plan of treaties to be proposed to foreign powers. The consideration of the first resolution, that of independence, was postponed to Monday the first day of July; and, in the meanwhile, that no time should be lost, in case the Congress should agree thereto, it was resolved, that a committee be appointed to prepare a Declaration, to the effect of the resolution. On the next day, the eleventh of June, the committee to prepare the Declaration of Independence was appointed; and immediately afterwards, the appointment of two other committees was resolved; one to prepare and digest the plan of a confederation, and the other to prepare the plan of treaties to be proposed to foreign powers. These committees were appointed on the twelfth of June.

The one, to prepare and digest the plan for a confederation, consisted of one member from each Colony. They reported on the twelfth of July, eight days after the Declaration of Independence, a draught of articles of confederation and perpetual union between the Colonies, naming them all from New Hampshire to Georgia. The most remarkable characteristic of this paper is the indiscriminate use of the terms Colonies and States, pervading the whole document, both the words denoting the parties to the confederacy. The title declared a confederacy between Colonies, but the first article of the draught was – “The name of this confederacy shall be the United States of America.” In a passage of the 18th article, it was said, – “The United States assembled, shall never engage the United Colonies in a war, unless the delegates of nine Colonies freely assent to the same.” The solution to this singularity was that the draught was in preparation before, and reported after, the Declaration of Independence. The principle upon which it was drawn up was, that the separate members of the confederacy should still continue Colonies, and only in their united capacity constitute States. The idea of separate State sovereignty had evidently no part in the composition of this paper. It was not countenanced in the Declaration of Independence; but appears to have been generated in the debates upon this draught of the articles of confederation, between the twelfth of July, and the ensuing twentieth of August, when it was reported by the committee of the whole in a new draught, from which the term Colony, as applied to the contracting parties, was carefully and universally excluded. The revised draught, as reported by the committee of the whole, exhibits, in the general tenor of its articles, less of the spirit of union, and more of the separate and sectional feeling, than the draught prepared by the first committee; and far more than the Declaration of Independence.

This was, indeed, what must naturally have been expected, in the progress of a debate, involving all the jarring interests and all the latent prejudices of the several contracting parties; each member now considering himself as the representative of a separate and corporate interest, and no longer acting and speaking, as in the Declaration of Independence, in the name and by the authority of the whole People of the Union. Yet in the revised draught itself, reported by the committee of the whole, and therefore exhibiting the deliberate mind of the majority of Congress at that time, there was no assertion of sovereign power as of right intended to be reserved to the separate States. But, in the original draught, reported by the select committee on the twelfth of July, the first words of the second article were, – “The said Colonies unite themselves so as never to be divided by any act whatever.” Precious words! – words, pronounced by the infant Nation, at the instant of her rising from the baptismal font! – words bursting from their hearts and uttered by lips yet glowing with the touch from the coal of the Declaration! – why were ye stricken out at the revisal of the draught, as reported by the committee of the whole? – There was in the closing article, both of the original and of the revised draught, a provision in these words, following a stipulation that the articles of confederation, when ratified, should be observed by the parties – “And the union is to be perpetual.” – Words, which, considered as a mere repetition of the pledge, the sacred pledge given in those first words of the contracting parties in the original draught, – “The said Colonies unite themselves so as never to be divided by any act whatever,” – discover only the intenseness of the spirit of union, with which the draught had been prepared; but which, taken by themselves, and stripped of that precious pledge, given by the personification of the parties announcing their perpetual union to the world, – how cold and lifeless do they sound! – “And the union is to be perpetual!” – as if it was an after-thought, to guard against the conclusion that an union so loosely compacted, was not even intended to be permanent.

The original draught, prepared by the committee contemporaneously with the preparation, by the other committee, of the Declaration of Independence, was in twenty articles. In the revised draught reported by the committee of the whole on the twentieth of August, the articles were reduced to sixteen. The four articles omitted, were the very grappling hooks of the Union. They secured to the citizens of each State, the right of native citizens in all the rest; and they conferred upon Congress the power of ascertaining the boundaries of the several States, and of disposing of the public lands which should prove to be beyond them. All these were stricken out of the revised draught. You have seen the mutilation of the second article, which constituted the Union. The third article contained the reserved rights of the several parties to the compact, expressed in the original draught thus:

“Each Colony shall retain and enjoy as much of its present laws, rights, and customs, as it may think fit; and reserves to itself the sole and exclusive regulation and government of its internal police, in all matters that shall not interfere with the articles of this confederation.”

In the revised draught, the first clause was omitted, and the article read thus:

“Each State reserves to itself the sole and exclusive regulation and government of its internal police, in all matters that shall not interfere with the articles of this confederation.”

From the twentieth of August, 1776, to the eighth of April, 1777, although the Congress were in permanent session, without recess but from day to day, no further action upon the revised draught reported by the committee of the whole was had. The interval was the most gloomy and disastrous period of the war. The debates, on the draught of articles reported by the first committee, had evolved and disclosed all the sources of disunion existing between the several sections of the country, aggravated by the personal rivalries, which, between the leading members of a deliberative assembly, animated by the enthusiastic spirit of liberty, could not fail to arise. When, instead of a constitution of government for a whole People, a confederation of independent States was assumed, as the fundamental principle of the permanent union to be organized for the American nation, the centripetal and centrifugal political powers were at once brought into violent conflict with each other.

The corporation and the popular spirits assumed opposite and adversary aspects. The federal and anti-federal parties originated. State pride, State prejudice, State jealousy, were soon embodied under the banners of State sovereignty, and while the cause of freedom and independence itself was drooping under the calamities of war and pestilence, with a penniless treasury, and an all but disbanded army, the Congress of the people had no heart to proceed in the discussion of a confederacy, overrun by a victorious enemy, and on the point, to all external appearance, of being crushed by the wheels of a conqueror’s triumphal car. On the eighth of April, 1777, the draught reported by the committee of the whole, on the preceding twentieth of August, was nevertheless taken up; and it was resolved that two days in each week should be employed on that subject, until it should be wholly discussed in Congress. The exigencies of the war, however, did not admit the regular execution of this order. The articles were debated only upon six days in the months of April, May, and June, on the twenty-sixth of which month the farther consideration of them was indefinitely postponed. On the eighteenth of September of that year, the Congress were obliged to withdraw from the city of Philadelphia, possession of which was immediately afterwards taken by the British army under the command of Sir William Howe. Congress met again on the thirtieth of September, at Yorktown, in the state of Pennsylvania, and there, on the second of October, resumed the consideration of the articles of confederation. From that time to the fifteenth of November, the debates were unremitting.

The yeas and nays, of which there had until then been no example, were now taken upon every prominent question submitted for consideration, and the struggle between the party of the States and the party of the People became, from day to day, more vehement and pertinacious. The first question upon which the yeas and nays were called was, that the representation in the Congress of the confederation should be proportional to a ratio of population, which was presented in two several modifications, and rejected in both. The next proposal was, that it should be proportional to the tax or contribution paid by the several States to the public treasury. This was also rejected; and it was finally settled as had been reported by the committee, that each State should have one vote. Then came the question of the proportional contributions of the several States. This involved the primary principle of the Revolution itself, which had been the indissoluble connection between taxation and representation. It follows as a necessary consequence from this, that all just taxation must be proportioned to representations; and here was the first stumbling block of the confederation. State sovereignty, which in the collision of debates had become stiff and intractable, insisted that, in the Congress of the Union, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, Virginia and Delaware, should each have one vote and no more. But when the burdens of the confederacy came to be apportioned, this equality could no longer be preserved; a different proportion became indispensable, and a territorial basis was assumed, apportioned to the value of improved land in each State. From the moment that these two questions were thus settled, it might have been foreseen that the confederacy must prove an abortion. Inequality and injustice were at its root. It was inconsistent with itself, and the seeds of its speedy dissolution were sown at its birth. But the question of the respective contributions of the several States, brought up another and still more formidable cause of discord and collision. What were the several States themselves? What was their extent, and where were their respective boundaries?

They claimed their territory by virtue of charters from the British kings, and by cessions from sundry tribes of Indians. But the charters of the kings were grossly inconsistent with one another. The charters had granted lands to several of the States, by lines of latitude from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Yet by the treaty of peace of February, 1763, between Great Britain and France, the King of Great Britain had agreed that the boundary of the British territories in North America should be the middle of the river Mississippi, from its source to the river Iberville, and thence to the ocean. The British colonial settlements had never been extended westward of the Ohio, and when the peace should come to be concluded, it was exceedingly doubtful what western boundary could be obtained from the assent of Great Britain. Besides which, there were claims of Spain, and a system of policy in France, in no wise encouraging to the expectation of an extended western frontier to the United States. Here then were collisions of interest between the States narrowly and definitely bounded westward, and the States claiming to the South Sea or to the Mississippi, which it was in vain attempted to adjust.

In the original draught of the articles of confederation, reported on the twelfth of July, among the powers proposed to be within the exclusive right of the United States assembled, were those of “limiting the bounds of those Colonies, which, by charter, or proclamation, or under any pretence, are said to extend to the South sea; and ascertaining those bounds of any other Colony that appear to be indeterminate: assigning territories for new Colonies, either in lands to be thus separated from Colonies, and heretofore purchased or obtained by the crown of Great Britain of the Indians, or hereafter to be purchased or obtained from them: disposing of all such lands for the general benefit of all the United Colonies: ascertaining boundaries to such new Colonies, within which forms of government are to be established on the principles of liberty.” This had been struck out of the revised articles reported by the committee of the whole.

A proposition was now made to require of the legislators of the several states, a description of their territorial lands, and documentary evidence of their claims, to ascertain their boundaries by the articles of confederation. This was rejected. Another proposition was, to bestow upon Congress the power to ascertain and fix the western boundary of the States claiming to the South Sea, and to dispose of the lands beyond this boundary for the benefit of the Union. This also was rejected, as was a similar proposal with regard to the States claiming to the Mississippi, or to the South Sea. These were all unavailing efforts to restore to the definitive articles of confederation, the provisions concerning the boundaries of the several States which had been reported in the original draught, and struck out of the draught reported by the committee of the whole, on the twentieth of August, 1776. An interval of fourteen months had since elapsed, which seemed rather to have weakened the spirit of union, and to have strengthened the anti-social prejudices, and the lofty pretensions of State sovereignty.

The articles containing the grant of powers to Congress, and prescribing restrictions upon those of the States, were fruitful of controversial questions and of litigious passions, which consumed much of the time of Congress till the fifteenth of November, 1777, when the articles of confederation, as finally matured and elaborated, were concluded and sent forth to the State Legislatures for their adoption. They were to take effect only when approved by them all, and ratified with their authority by their Delegates in Congress. It was provided, by one of the articles, that no alteration of them should ever be admitted, unless sanctioned with the same unanimity. There was a solemn promise, inserted in the concluding article, that the articles of confederation should be inviolably observed by every State, and that the Union should be perpetual. The consummation of the triumph of unlimited State sovereignty over the spirit of union, was seen in the transposition of the second and third of the articles reported by the committees, and the inverted order of their insertion in the articles finally adopted.

The first article in them all gave the name, or as it was at last called, the style, of the confederacy, “The United States of America.” The name, by which the nation has ever since been known, and now illustrious among the nations of the earth. The second article, of the plans reported to the Congress by the original committee and by the committee of the whole, constituted and declared the Union, in the first project commencing with those most affecting and ever-memorable words, – “The said Colonies united themselves so as never to be divided by any act whatever:” In the project reported by the committee of the whole, these words were struck out, but the article still constituted and declared the Union. The third article contained, in both projects, the rights reserved by the respective States; rights of internal legislation and police, in all matters not interfering with the articles of the confederation.

But on the fifteenth of November, 1777, when the partial, exclusive, selfish and jealous spirit of State sovereignty had been fermenting and fretting over the articles, stirring up all the oppositions of the corporate interests and humors of the parties, when the articles came to be concluded, the order of the second and third articles was inverted. The reservation of the rights of the separate States was made to precede the institution of the Union itself. Instead of limiting the reservation to its municipal laws and the regulation and government of their internal police, in all matters not interfering with the articles of the confederation, they ascend the throne of State sovereignty, and make the articles of confederation themselves mere specific exceptions to the general reservation of all the powers of government to themselves. The article was in these words: “Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States in Congress assembled.” How different from the spirit of the article, which began, – “The said Colonies unite themselves so as never to be divided by any act what ever!” The institution of the Union was now postponed to follow and not to precede the reservations; and cooled into a mere league of friendship and of mutual defense between the States.

More then sixteen months of the time of Congress had been absorbed in the preparation of this document. More than three years and four months passed away before its confirmation by the Legislatures of all the States, and no sooner was it ratified, than its utter inefficiency to perform the functions of a government, or even to fulfil the purposes of a confederacy, became apparent to all! In the Declaration of Independence, the members of Congress who signed it had spoken in the name and by the authority of the People of the Colonies. In the articles of confederation they had sunk into Representatives of the separate States. The genius of unlimited State sovereignty had usurped the powers which belonged only to the People, and the State Legislatures and their Representatives had arrogated to themselves the whole constituent power, while they themselves were Representatives only of fragments of the nation.

The articles of confederation were satisfactory to no one of the States: they were adopted by many of them, after much procrastination, and with great reluctance. The State of Maryland persisted in withholding her ratification, until the question relating to the unsettled lands had been adjusted by cessions of them to the United States, for the benefit of them all, from the States separately claiming them to the South sea, or the Mississippi. The ratification of the articles was completed on the first of March, 1781, and the experiment of a merely confederated Union of the thirteen States commenced. It was the statue of Pygmalion before its animation, – beautiful and lifeless. And where was the vital spark which was to quicken this marble into life? It was in the Declaration of Independence. Analyze, at this distance of time, the two documents, with cool and philosophical impartiality, and you will exclaim, – Never, never since the creation of the world, did two state papers, emanating from the same body of men, exhibit more dissimilarity of character, or more conflict of Principle! The Declaration, glowing with the spirit of union, speaking with one voice the vindication of one People for the act of separating themselves from another, and ascending to the First Cause, the dispenser of eternal justice, for the foundation of its reasoning: – The articles of confederation, stamped with the features of contention; beginning with niggardly reservations of corporate rights, and in the grant of powers, seeming to have fallen into the frame of mind described by the sentimental traveler, bargaining for a post chaise, and viewing his conventionist with an eye as if he was going with him to fight a duel! Yet, let us not hastily charge our fathers with inconsistency for these repugnances between their different works. Let us never forget that the jealousy of power is the watchful handmaid to the spirit of freedom.

Let the contemplation of these rugged and narrow passes of the mountains first with so much toil and exertion traversed by them, teach us that the smooth surfaces and rapid railways, which have since been opened to us, are but the means furnished to us of arriving by swifter conveyance to a more advanced stage of improvement in our condition. Let the obstacles, which they encountered and surmounted, teach us how much easier it is in morals and politics, as well as in natural philosophy and physics, to pull down than to build up, to demolish than to construct; then, how much more arduous and difficult was their task to form a system of polity for the people whom they ushered into the family of nations, than to separate them from the parent State; and lastly, the gratitude due from us to that Being whose providence watched over, protected, and guided our political infancy, and led our ancestors finally to retrace their steps, to correct their errors, and resort to the whole People of the union for a constitution of government, emanating from themselves, which might realize that union so feelingly expressed by the first draught of their confederation, so as never to be divided by any act whatever. The origin and history of this Constitution is doubtless familiar to most of my hearers, and should be held in perpetual remembrance by us all.

It was the consummation of the Declaration of Independence. It has given the sanction of half a century’s experience to the principles of that Declaration. The attempt to sanction them by a confederation of sovereign States was made and signally failed. It was five years in coming to an immature birth, and expired after five years of languishing and impotent existence. On the seventeenth of next September, fifty years will have passed away since the Constitution of the United States was presented to the People for their acceptance. On that day the twenty-fifth biennial Congress, organized by this Constitution, will be in session. And what a happy, what a glorious career have the people passed through in the half century of their and your existence associated under it! When that Constitution was adopted, the States of which it was composed were thirteen in number, – their whole population not exceeding three millions and a half of souls; the extent of territory within their boundary so large that it was believed too unwieldy to be manageable, even under one federative government, but less than one million of square miles; without revenue; encumbered with a burdensome revolutionary debt, without means of discharging even the annual interest accruing upon it; with no manufactures; with a commerce scarcely less restricted than before the revolutionary war; denied by Spain the privilege of descending the Mississippi; denied by Great Britain the stipulated possession of a line of forts on the Canadian frontier; with a disastrous Indian war at the west; with a deep-laid Spanish intrigue with many of our own citizens, to dismember the Union, and subject to the dominion of Spain the whole valley of the Mississippi; with a Congress, imploring a grant of new powers to enable them to redeem the public faith, answered by a flat refusal, evasive conditions, or silent contempt; with popular insurrection scarcely extinguished in this our own native Commonwealth, and smoking into flame in several others of the States; with an impotent and despised government; a distressed, discontented, discordant people, and the fathers of the revolution burning with shame, and almost sinking into despair of its issue.

Fellow citizens of a later generation! You, whose lot it has been to be born in happier times; you, who even now are smarting under a transient cloud intercepting the dazzling sun-shine of your prosperity; – think you that the pencil of fancy has been borrowed to deepen the shades of this dark and desolate picture? Ask of your surviving fathers, cotemporaries of him who now addresses you, – ask of them, whose hospitable mansions often welcomed him to their firesides, when he came in early youth to receive instruction from the gigantic intellect and profound learning of a Parsons, – ask of them, if there be any among you that survive, and they will tell you, that, far from being overcharged, the portraiture of that dismal day is only deficient in the faintness of its coloring and the lack of energy in the painter’s hand. Such was the condition of this your beloved country after the close of the revolutionary war, under the blast of the desert, in the form of a confederacy; when, wafted, as on the spicy gales of Araby [Arabia] the blest, your Constitution, with Washington at its head,

“Came o’er our ears like the sweet sound That breathes upon a bank of violets, Stealing and giving odor.” [Quoted from William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, Act. 1, Scene 1 (c. 1601).]