UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF KENTUCKY

LONDON DIVISION

SARAH DOE and THOMAS DOE, on behalf of themselves and their minor child, JAN DOE Plaintiffs,

v

Civil Action No. 99-508 HARLAN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT; DON MUSSELMAN, in his official capacity

as Superintendent of the Harlan Country School District, Defendents.

Upon being duly sworn by the undersigned officer empowered to administer and attest to oaths, the Affiant, David Barton, testifies as follows:

- I am a recognized authority in American history, particularly concerning the Colonial, Revolutionary, and Federal Eras.

- I personally own a vast collection of thousands of documents of American history predating 1812, including handwritten works of the signers of the Declaration and the Constitution.

- As a result of my expertise, I work as a consultant to national history textbook publishers and have been appointed by the State Boards of Education in States such as California and Texas to help write the American history and government standards for students in those States. Additionally, I consult with Governors and State Boards of Education in several other States and have testified in numerous State Legislatures on American history.

- I am the recipient of several national and international awards, including the George Washington Honor Medal, the Daughters of the American Revolution Medal of Honor, Who’s Who in America (1997, 1999), Who’s Who in the World (1996, 1999), Who’s Who in American Education (1996, 1997), International Who’s Who of Professionals (1996), Two Thousand Notable American Men Hall of Fame (1995), Who’s Who in the South and Southwest (1995, 1999), Who’s Who Among Outstanding Americans (1994), Outstanding Young Men in America (1990), and numerous other awards.

- I have also written and published numbers of books and articles on American history and its related issues. (Original Intent, 1996; Bulletproof George Washington, 1990; Ethics: An Early American Handbook, 1999; Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, 1995, and many others).

- I offer the following opinion regarding whether the Ten Commandments are a historical document in America’s civil and judicial history based upon my expertise and study in the areas of American history and the forces and ideas that formed the basis for our system of laws and government.

INTRODUCTION

- Opponents to the public display of the Ten Commandments offer several grounds for their objections, including that “there is no ‘standard version’ of the Ten Commandments”;1 that “there is not agreement on exactly what constitutes the Ten Commandments”;2 and that “the Ten Commandments are not a ‘secular’ moral code that everyone can agree on”3 and therefore are not appropriate to be included in a display of documents that have helped shape America’s history. In fact, these groups warn that “if the Decalog [sic] was publicly displayed” it “could create religious friction, leading to feelings of anger and of marginalization” and that “these emotions are precisely the root causes of the Columbine High School tragedy.”4

- The Decalogue addresses what were long considered to be man’s vertical and horizontal duties. Noah Webster, the man personally responsible for Art. I, Sec. 8, ¶ 8, of the U. S. Constitution, explained two centuries ago:

The duties of men are summarily comprised in the Ten Commandments, consisting of two tables; one comprehending the duties which we owe immediately to God— the other, the duties we owe to our fellow men.5

- Modern critics, while conceding “six or five Commandments are moral and ethical rules governing behavior,”6 also point out that because the remaining “four of the Ten Commandments are specifically religious in nature,”7 that this fact alone should disqualify their display. They assert that only one of the two “tablets” of the Ten Commandments is appropriate for public display.8

- In an effort to substantiate this position historically, critics often point to the Rhode Island Colony under Roger Williams and its lack of civil laws on the first four commandments to “prove” that American society was traditionally governed without the first “tablet.”9 However, they fail to mention that the Rhode Island Colony was the only one of the thirteen colonies that did not have civil laws derived from the first four divine laws10—the so-called first “tablet.” Significantly, every other early American colony incorporated the entire Decalogue into its own civil code of laws.

- This affidavit will demonstrate that, historically speaking, neither courts nor civil officers were confused or distracted by the so-called “various versions” of the Decalogue and that each of the Ten Commandments became deeply embedded in both American law and jurisprudence. This affidavit will establish that a contemporary display of the Ten Commandments is the display of a legal and historical document that dramatically impacted American law and culture with a force similar only to that of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

THE INCORPORATION OF DIVINE LAW INTO AMERICAN COLONIAL LAW

- The Ten Commandments are a smaller part of the larger body of divine law recognized and early incorporated into America’s civil documents. For example, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut—established in 1638-39 as the first written constitution in America and considered as the direct predecessor of the U. S. Constitution11—declared that the Governor and his council of six elected officials would “have power to administer justice according to the laws here established; and for want thereof according to the rule of the word of God.”12

- Also in 1638, the Rhode Island government adopted “all those perfect and most absolute laws of His, given us in His holy word of truth, to be guided and judged thereby. Exod. 24. 3, 4; 2 Chron. II. 3; 2 Kings. II. 17.”13

- The following year, 1639, the New Haven Colony adopted its “Fundamental Articles” for the governance of that Colony, and when the question was placed before the colonists:

Whether the Scriptures do hold forth a perfect rule for the direction and government of all men in all dut[ies] which they are to perform to God and men as well in the government of families and commonwealths as in matters of the church, this was assented unto by all, no man dissenting as was expressed by holding up of hands.14

- In 1672, Connecticut revised its laws and reaffirmed its civil adherence to the laws established in the Scriptures, declaring:

The serious consideration of the necessity of the establishment of wholesome laws for the regulating of each body politic hath inclined us mainly in obedience unto Jehovah the Great Lawgiver, Who hath been pleased to set down a Divine platform not only of the moral but also of judicial laws suitable for the people of Israel; as . .. laws and constitutions suiting our State.15

- Significantly, those same legal codes delineated their capital laws in a separate section, and following each capital law was given the Bible verse on which that law was based16 because:

No man’s life shall be taken away . . . unless it be by the virtue or equity of some express law of the country warranting the same, established by a general court and sufficiently published, or in case of the defect of a law, in any particular case, by the Word of God.17 (emphasis added)

- There are other similar examples, but it is a matter of historical fact that the early colonies adopted the greater body of divine laws as the overall basis of their civil laws. Subsequent to the adoption of that general standard, however, the specifics of the Decalogue were then incorporated into the civil statutes.

WHICH ARE THE TEN COMMANDMENTS?

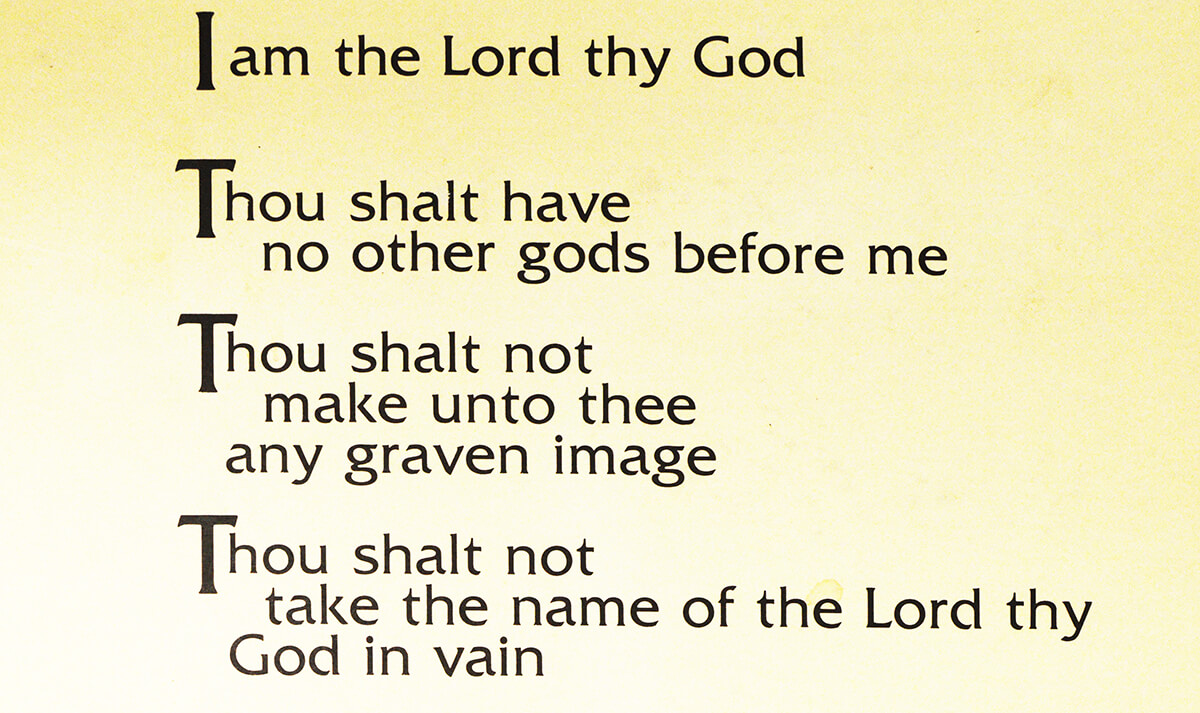

- In order to avoid the alleged misunderstanding that critics claim accompanies the reading of the Decalogue, for the purposes of this affidavit, these Commandments as listed in the Bible in Exodus 20:3-17 and Deuteronomy 5:7-21 (and in a shortened version in Exodus 34:14-28) will be summarized as:

Have no other gods.

Have no idols.

Honor God’s name.

Honor the Sabbath day.

Honor your parents.

Do not murder.

Do not commit adultery.

Do not steal.

Do not perjure yourself.

Do not covet.

- The following sections will fully demonstrate that each of these commandments was individually encoded in the civil laws, and consequently became a part of the common law of the various colonies.

HOW THE TEN COMMANDMENTS ARE EXPRESSED IN CIVIL LAW IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Have no other gods.

- This first commandment of the Decalogue is incorporated into the very first written code of laws enacted in America, those of the Virginia Colony. In 1610, in a law enacted by the Colony leaders, it was declared:

[S]ince we owe our highest and supreme duty, our greatest and all our allegiance to Him from whom all power and authority is derived, and flows as from the first and only fountain, and being especially soldiers impressed in this sacred cause, we must alone expect our success from Him who is only the blesser of all good attempts, the King of kings, the Commander of commanders, and Lord of hosts, I do strictly command and charge all Captains and Officers of what quality or nature soever, whether commanders in the field, or in town or towns, forts or fortresses, to have a care that the Almighty God be duly and daily served, and that they call upon their people to hear sermons, as that also they diligently frequent morning and evening prayer themselves by their own example and daily life and duties herein, encouraging others thereunto.18

- A subsequent 1641 Massachusetts legal code also incorporated the thrust of this command of the Decalogue into its statutes. Significantly, the very first law in that State code was based on the very first command of the Decalogue, declaring:

- If any man after legal conviction shall have or worship any other god but the Lord God, he shall be put to death. Deut. 13.6, 10, Deut. 17.2, 6, Ex. 22.20.19

- The 1642 Connecticut law code also made this command of the Decalogue its first civil law, declaring:

- If any man after legal conviction shall have or worship any other god but the Lord God, he shall be put to death (Duet. 13.6 and 17.2, Ex. 22.20).20

- There are numerous other examples affirming that the first commandment of the Decalogue indeed formed an historical part of American civil law.

Have no idols.

- Typical of the civil laws prohibiting idolatry was a 1680 New Hampshire idolatry law that declared:

Idolatry. It is enacted by ye Assembly and ye authority thereof, yet if any person having had the knowledge of the true God openly and manifestly have or worship any other god but the Lord God, he shall be put to death. Ex. 22.20, Deut. 13.6 and 10.21

- Additional examples from colonial codes demonstrate that the second commandment also was historically a part of American civil law.

Honor God’s name.

- Civil laws enacted to observe this commandment were divided into two categories: laws prohibiting blasphemy and laws prohibiting swearing and profanity. Noah Webster, an American legislator and judge, affirms that both of these categories of laws were derived from the third commandment of the Decalogue:

When in obedience to the third commandment of the Decalogue you would avoid profane swearing, you are to remember that this alone is not a full compliance with the prohibition which [also] comprehends all irreverent words or actions and whatever tends to cast contempt on the Supreme Being or on His word and ordinances [i.e., blasphemy].22

- Reflecting the civil enactment of these two categories embodying the third commandment, a 1610 Virginia law declared:

- That no man speak impiously or maliciously against the holy and blessed Trinity or any of the three persons . . . upon pain of death. 3. That no man blaspheme God’s holy name upon the pain of death.23

- A 1639 law of Connecticut similarly declared:

If any person shall blaspheme the name of God the Father, Son, or Holy Ghost, with direct, express, presumptuous or high-handed blasphemy, or shall curse in the like manner, he shall be put to death. Lev. 24.15, 16.24

- Similar laws can be found in Massachusetts in 1641,25 Connecticut in 1642,26 New Hampshire in 1680,27 Pennsylvania in 1682,28 1700,29 and 1741,30 South Carolina in 1695,31 North Carolina in 1741,32 etc. Additionally, prominent Framers also enforced the Decalogue’s third command.

- For example, Commander-in-Chief George Washington issued numerous military orders during the American Revolution that first prohibited swearing and then ordered an attendance on Divine worship, thus relating the prohibition against profanity to a religious duty. Typical of these orders, on July 4, 1775, Washington declared:

The General most earnestly requires and expects a due observance of those articles of war established for the government of the army which forbid profane cursing, swearing, and drunkenness; and in like manner requires and expects of all officers and soldiers not engaged on actual duty, a punctual attendance on Divine Service to implore the blessings of Heaven upon the means used for our safety and defense.33

- Washington began issuing such orders to his troops as early as 1756 during the French and Indian War,34 and continued the practice throughout the American Revolution, issuing similar orders in 1776,35 1777,36 1778,37 etc.

- This civil prohibition against blasphemy and profanity drawn from the Decalogue continued well beyond the Founding Era. It subsequently appeared in the 1784 laws in Connecticut,38 the 1791 laws of New Hampshire,39 the 1791 laws of Vermont,40 the 1792 laws of Virginia,41 the 1794 laws of Pennsylvania,42 the 1821 laws of Maine,43 the 1834 laws of Tennessee,44 the 1835 laws of Massachusetts,45 the 1836 laws of New York,46 etc.

- Judge Zephaniah Swift, author in 1796 of the first legal text published in America, explained why civil authorities enforced the Decalogue prohibition against blasphemy and profane swearing:

Crimes of this description are not punishable by the civil arm merely because they are against religion. Bold and presumptuous must he be who would attempt to wrest the thunder of heaven from the hand of God and direct the bolts of vengeance where to fall. The Supreme Deity is capable of maintaining the dignity of His moral government and avenging the violations of His holy laws. His omniscient mind estimates every act by the standard of perfect truth and His impartial justice inflicts punishments that are accurately proportioned to the crimes. But shortsighted mortals cannot search the heart and punish according to the intent. They can only judge by overt acts and punish them as they respect the peace and happiness of civil society. This is the rule to estimate all crimes against civil law and is the standard of all human punishments. It is on this ground only that civil tribunals are authorized to punish offences against religion.47

- In 1824, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (in a decision subsequently invoked authoritatively and endorsed by the U. S. Supreme Court48) reaffirmed that the civil laws against blasphemy were derived from divine law:

The true principles of natural religion are part of the common law; the essential principles of revealed religion are part of the common law; so that a person vilifying, subverting or ridiculing them may be prosecuted at common law.49

The court then noted that its State’s laws against blasphemy had been drawn up by James Wilson, a signer of the Constitution and original Justice on the U. S. Supreme Court:

The late Judge Wilson, of the Supreme Court of the United States, Professor of Law in the College in Philadelphia, was appointed in 1791, unanimously by the House of Representatives of this State to “revise and digest the laws of this commonwealth. . . . ” He had just risen from his seat in the Convention which formed the Constitution of the United States, and of this State; and it is well known that for our present form of government we are greatly indebted to his exertions and influence. With his fresh recollection of both constitutions, in his course of Lectures (3d vol. of his works, 112), he states that profaneness and blasphemy are offences punishable by fine and imprisonment, and that Christianity is part of the common law. It is vain to object that the law is obsolete; this is not so; it has seldom been called into operation because this, like some other offences, has been rare. It has been retained in our recollection of laws now in force, made by the direction of the legislature, and it has not been a dead letter.50

- The Decalogue’s influence on profanity and blasphemy laws was reaffirmed by subsequent courts, such as the 1921 Supreme Court of Maine,51 the 1944 Supreme Court of Florida,52 and others.53

- Many additional sources may be cited, but it is clear that the civil laws against both profanity and blasphemy—many of which are still in force today—were originally derived from the divine law and the Ten Commandments. These examples unquestionably demonstrate that the third commandment of the Decalogue was an historical part of American civil law and jurisprudence.

Honor the Sabbath day.

- The civil laws enacted to uphold this injunction are legion and are far too numerous for any exhaustive listing to be included in this brief affidavit. While a representative sampling will be presented below, there are three points that clearly establish the effect of the fourth commandment of the Decalogue on American law.

- First is the inclusion in the U. S. Constitution of the recognition of the Sabbath in Art. I, Sec. 7, ¶ 2, stipulating that the President has 10 days to sign a law, “Sundays excepted.” The “Sundays excepted” clause had previously appeared in the individual State constitutions of that day, and therefore, when incorporated into the U. S. Constitution, carried the same meaning that had been established by traditional usage in the States. That meaning was then imparted into the constitutions of the various States admitted into the Union subsequent to the adoption of the federal Constitution. The historical understanding of this clause was summarized in 1912 by the Supreme Court of Missouri which, expounding on the meaning of this provision in its own State constitution and in the U. S. Constitution, declared:

It is provided that if the Governor does not return a bill within 10 days (Sundays excepted), it shall become a law without his signature. Although it may be said that this provision leaves it optional with the Governor whether he will consider bills or not on Sunday, yet, regard being had to the circumstances under which it was inserted, can any impartial mind deny that it contains a recognition of the Lord’s Day as a day exempted by law from all worldly pursuits? The framers of the Constitution, then, recognized Sunday as a day to be observed, acting themselves under a law which exacted a compulsive observance of it. If a compulsive observance of the Lord’s Day as a day of rest had been deemed inconsistent with the principles contained in the Constitution, can anything be clearer than, as the matter was so plainly and palpably before the Convention, a specific condemnation of the Sunday law would have been engrafted upon it? So far from it, Sunday was recognized as a day of rest.54

- The second point establishing the impact of the fourth commandment of the Decalogue on American law is seen in the civil process clauses of the early State legal codes which forbade legal action on the Sabbath. For example, an 1830 New York law declared:

Civil process cannot, by statute, be executed on Sunday, and a service of such process on Sunday is utterly void and subjects the officer to damages.55

- Similar laws may be found in Pennsylvania in 168256 and 1705,57 Vermont in 1787,58 Connecticut in 1796,59 New Jersey in 1798,60 etc.

- The third point establishing the long-standing effect of the fourth commandment on American law and jurisprudence is demonstrated by the fact that Sabbath laws remain constitutional today,61 and many communities still practice and enforce those laws.

- Examples of the early implementation of this fourth commandment into civil law are seen in the Virginia laws of 1610,62 the New Haven laws of 1653,63 the New Hampshire laws of 1680,64 the Pennsylvania laws of 168265 and 1705,66 the South Carolina laws of 1712,67 the North Carolina laws of 1741,68 the Connecticut laws of 1751,69 etc.

- In 1775, and throughout the American Revolution, Commander-in-Chief George Washington issued military orders directing that the Sabbath be observed. His order of May 2, 1778, at Valley Forge was typical:

The Commander in Chief directs that divine service be performed every Sunday at 11 o’clock in those brigades to which there are chaplains; those which have none to attend the places of worship nearest to them. It is expected that officers of all ranks will by their attendance set an example to their men.70

Washington issued numerous similar orders throughout the Revolution.71

- In the Federal Era and well beyond, states continued to enact and reenact Sabbath laws. In fact, the States went to impressive lengths to uphold the Sabbath. For example, in 1787, Vermont enacted a ten-part law to preserve the Sabbath;72 in 1791, Massachusetts enacted an eleven-part law;73 in 1792, Virginia enacted an extensive eight part law74—a law written by Thomas Jefferson and sponsored by James Madison;75 in 1798, New Jersey enacted a twenty-one-part law;76 in 1799, New Hampshire enacted a fourteen-part law;77 in 1821, Maine enacted a thirteen-part law;78 etc.79

- These Sabbath laws—and scores of others like them—were nothing less than the enactment of the fourth commandment in the Decalogue. In fact, in 1967, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania provided a thorough historical exegesis of those laws and concluded:

“Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy; six days shalt thou labor and do all thy work; but the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God. In it thou shalt not do any work.” This divine pronouncement became part of the Common Law inherited by the thirteen American colonies and by the sovereign States of the American union.80

- In 1950, the Supreme Court of Mississippi had similarly declared:

The Sunday laws have a divine origin. Blackstone (Cooley’s) Par. 42, page 36. After the six days of creation, the Creator Himself rested on the Seventh. Genesis, Chapter 2, verses 2 and 3. Thus, the Sabbath was instituted, as a day of rest. The original example was later confirmed as a commandment when the law was handed down from Mt. Sinai: “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.”1

- Similar declarations may be found in the courts of numerous other States, including New York,82 Alabama,83 Florida, Oregon, and Kentucky,84 Georgia,85 Minnesota,86 etc.

- However, before any of these contemporary courts had acknowledged that the Sabbath laws were derived from the Decalogue, John Jay, the original Chief Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court, had confirmed that the source of civil Sabbath laws were the divine commands. As he explained:

There were several divine, positive ordinances . . . of universal obligation, as the Sabbath.87

- There are numerous other examples demonstrating that the fourth commandment of the Decalogue played an important historical role in American civil law.

- While contemporary critics argue that the first four commands of the Decalogue were inconsequential in our history or that they should not be publicly displayed today, the facts prove that they exerted a substantial influence on American law and jurisprudence. In fact, the 1922 Iowa Supreme Court rejected the assertion that only one side of the Decalogue was important to American law, declaring:

The observance of Sunday is one of our established customs. It has come down to us from the same Decalogue that prohibited murder, adultery, perjury, and theft. It is more ancient than our common law or our form of government. It is recognized by Constitutions and legislative enactments, both State and federal. On this day Legislatures adjourn, courts cease to function, business is suspended, and nationwide our citizens cease from labor.88

- Whether individuals today agree with those early laws based on the first four commandments in the Decalogue in no manner lessens their historical impact.

Honor your parents.

- This fifth command begins the so-called second “tablet” of the Decalogue—the section addressing “civil” behavior that even critics acknowledge to be appropriate for public display.89 This portion of the Decalogue formed the basis of many of our current criminal laws and modern courts are not reticent to acknowledge and enforce these commandments. As the Supreme Court of Indiana declared in 1974:

Virtually all criminal laws are in one way or another the progeny of Judeo-Christian ethics. We have no intention to overrule the Ten Commandments.90

- Yet the mandates of the Decalogue currently embodied in our criminal laws are no less religiously-based than were the first four commandments. For example, a 1642 Connecticut law addressing the fifth commandment specifically cited both the Decalogue and additional Bible verses as the basis for its civil laws related to honoring parents:

If any child or children above sixteen years old, and of sufficient understanding shall curse or smite their normal father or mother, he or they shall be put to death; unless it can be sufficiently testified that the parents have been very unchristianly negligent in the education of such children, or so provoke them by extreme and cruel correction that they have been forced thereunto to preserve themselves from death [or] maiming. Ex. 21:17, Lev. 20, Ex. 20:15.91

This law also appears in other State codes as well.92

- Even three centuries after these early legal codes, this commandment was still influencing civil laws—as confirmed in 1934 by a Louisiana appeals court that cited the fifth commandment of the Decalogue as the basis of civil policy between parents and children:

“ ‘Honor thy father and thy mother,’ is as much a command of the municipal law as it is a part of the Decalogue, regarded as holy by every Christian people. ‘A child,’ says the code, ‘whatever be his age, owes honor and respect to his father and mother.’ ”93

- Other courts have made similar declarations,94 all confirming that the fifth commandment of the Decalogue was an historical part of American civil law and jurisprudence.

Do not murder.

- The next several commands form much of the heart of our criminal laws, and, as noted by Noah Webster, one of the first founders to call for the Constitutional Convention, the divine law is the original source of several of those criminal laws:

The opinion that human reason left without the constant control of Divine laws and commands will . . . give duration to a popular government is as chimerical as the most extravagant ideas that enter the head of a maniac. . . . Where will you find any code of laws among civilized men in which the commands and prohibitions are not founded on Christian principles? I need not specify the prohibition of murder, robbery, theft, [and] trespass.95

- The early civil laws against murder substantiate the influence of the Decalogue and divine laws on American criminal laws. For example, a 1641 Massachusetts law declared:

- Ex. 21.12, Numb. 35.13, 14, 30, 31. If any person commit any willful murder, which is manslaughter committed upon premeditated malice, hatred, or cruelty, not in a man’s necessary and just defense nor by mere casualty against his will, he shall be put to death.

- Numb. 25.20, 21. Lev. 24.17. If any person slayeth another suddenly in his anger or cruelty of passion, he shall be put to death.

- Ex. 21.14. If any person shall slay another through guile, either by poisoning or other such devilish practice, he shall be put to death.96

- Perhaps the point is too obvious to belabor, but similar provisions can be found in the Connecticut laws of 1642,97 the New Hampshire laws of 1680,98 etc.

- Courts, too, have been very candid in tracing civil murder laws back to the Decalogue. For example, a 1932 Kentucky appeals court declared:

The rights of society as well as those of appellant are involved and are also to be protected, and to that end all forms of governments following the promulgation of Moses at Mt. Sinai has required of each and every one of its citizens that “Thou shalt not murder.” If that law is violated, the one guilty of it has no right to demand more than a fair trial, and if, as a result thereof, the severest punishment for the crime is visited upon him, he has no one to blame but himself.99

- Even the “severest punishment for the crime” is traced back to divine laws. As first Chief Justice John Jay explained:

There were several divine, positive ordinances . . . of universal obligation, as . . . the particular punishment for murder.100

- There certainly exist more than sufficient cases101 with declarations similar to that made by the Kentucky court above to demonstrate that the sixth commandment of the Decalogue exerted substantial force on American civil law and jurisprudence.

Do not commit adultery.

- Directly citing the Decalogue, a 1641 Massachusetts law declared:

If any person committeth adultery with a married or espoused wife, the adulterer and adulteresses shall surely be put to death. Ex. 20.14.102

- Other States had similar laws, such as Connecticut in 1642,103 Rhode Island in 1647,104 New Hampshire in 1680,105 Pennsylvania in 1705,106 etc. In fact, in 1787, nearly a century-and-a-half after the earliest colonial laws, Vermont enacted an adultery law, declaring that it was based on divine law:

Whereas the violation of the marriage covenant is contrary to the command of God and destructive to the peace of families: be it therefore enacted by the general assembly of the State of Vermont that if any man be found in bed with another man’s wife, or woman with another’s husband, . . . &c.107

- Subsequent civil laws on adultery passed in other States used the same basis for their own laws.108

- Two-and-a-half centuries later, courts were still using divine laws and the Decalogue as the basis for the enforcement of their own State statutes on the subject. For example, in 1898, the highest criminal court in Texas declared that its State laws on adultery were derived from the Decalogue:

The accused would insist upon the defense that the female consented. The state would reply that she could not consent. Why? Because the law prohibits, with a penalty, the completed act. “Thou shalt not commit adultery” is our law as well as the law of the Bible.109

- Half-a-century later in 1955, the Washington Supreme Court declared that the Decalogue was the basis of its State laws against adultery:

Adultery, whether promiscuous or not, violates one of the Ten Commandments and the statutes of this State.110

- Other courts made similar declarations.111 These and numerous additional examples demonstrate that the seventh commandment of the Decalogue was an historical part of American civil law and jurisprudence.

Do not steal.

- The laws regarding theft that indicate their reliance on divine law and the Decalogue are far too numerous even to begin listing. Perhaps the simplest summation is given by Chancellor James Kent, who is considered, along with Justice Joseph Story, as one of the two “Fathers of American Jurisprudence.” In his classic 1826 Commentaries on American Law, Kent confirmed that the prohibitions against theft were found in divine law:

To overturn justice by plundering others tended to destroy civil society, to violate the law of nature, and the institutions of Heaven.112

- Subsequent to James Kent, numerous other legal sources have reaffirmed the divine origin of the prohibition against theft. For example, in 1951, the Louisiana Supreme Court acknowledged the Decalogue as the basis for the unchanging civil laws against theft:

In the Ten Commandments, the basic law of all Christian countries, is found the admonition “Thou shalt not steal.”113

- In 1940, the Supreme Court of California had made a similar acknowledgment:

Defendant did not acknowledge the dominance of a fundamental precept of honesty and fair dealing enjoined by the Decalogue and supported by prevailing moral concepts. “Thou shalt not steal” applies with equal force and propriety to the industrialist of a complex civilization as to the simple herdsman of ancient Israel.114

- Significantly, other courts acknowledged the same, including the Utah Supreme Court,115 the Colorado Supreme Court,116 the Florida Supreme Court,117 the Missouri Supreme Court,118 etc.

- However, the eighth commandment of the Decalogue provided the foundation for civil laws other than just those against theft. For example, in 1904, an Appeals Court in West Virginia cited the eighth commandment of the Decalogue as the basis for laws protecting the integrity of elections:

[T]here are some people who at least profess to believe that elections, being human institutions, are governed solely by human inclinations, and are not subject to the supervision or control of that moral code of ethics promulgated by God through the greatest of all human law-givers from Sinai’s hoary summit. This, however, is a great and grievous error, for the eighth commandment, “Thou shalt not steal,” forbids not only larceny as defined in the Criminal Code, but also the unjust deprivation of every person’s civil, religious, political, and personal rights of life, liberty, reputation, and property—even though done under the sanction of legal procedure.119

- And in 1914, a federal court acknowledged that the Constitution’s “takings clause” was an embodiment of the Decalogue’s eighth commandment:

Bared to nakedness, the facts show that the Rochester Company simply coveted and desired its neighbor’s property, and to make this covetous purpose effective it seeks to violate, not only the act of congress, which says, “But this shall not be construed as requiring any such common carrier to give the use of its tracks or terminal facilities to another carrier engaged in like business,” but that constitutional provision which in effect but restates another of the Decalogue when it provides, “Nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.”120

- There are numerous other examples demonstrating that the eighth commandment of the Decalogue was an historical part of American civil law and jurisprudence.

Do not perjure yourself.

- A 1642 Connecticut law against perjury acknowledged its basis to be in divine law, declaring:

If any man rise up by false witness, wittingly and of purpose, to take away any man’s life, he shall be put to death. Deut. 19:16, 18, 19.121

- Similar laws on perjury declaring their basis to be in divine law and the Decalogue may be found in Massachusetts in 1641,122 Rhode Island in 1647,123 New Hampshire in 1680,124 Connecticut in 1808,125 etc.

- Courts were also open in acknowledging their indebtedness to the Decalogue for the civil perjury laws. For example, 1924, the Oregon Supreme Court declared:

No official is above the law. “Thou shalt not bear false witness” is a command of the Decalogue, and that forbidden act is denounced by statute as a felony.126

- And in 1988, the Supreme Court of Mississippi, citing the Decalogue, reproached a prosecutor for introducing accusations during cross-examination of a defendant for which the prosecutor had no evidence:

When the State or any party states or suggests the existence of certain damaging facts and offers no proof whatever to substantiate the allegations, a golden opportunity is afforded the opposing counsel in closing argument to appeal to the Ninth Commandment. “Thou shalt not bear false witness . . . ” Exodus 20:16.127

- Numerous other courts have cited the Decalogue as the source of the laws on perjury, including courts in Missouri,128 California,129 Florida,130 etc. These and many other examples demonstrate that the ninth commandment of the Decalogue was incorporated into American civil law and jurisprudence.

Do not covet.

- This tenth commandment in the Decalogue actually forms the basis for many of the prohibitions found in the other commandments. That is, a violation of this commandment frequently precedes a violation of the other commandments. As William Penn, the framer of the original laws of Pennsylvania, declared:

[H]e that covets can no more be a moral man than he that steals since he does so in his mind. Nor can he be one that robs his neighbor of his credit, or that craftily undermines him of his trade or office.131

- John Adams, one of only two individuals who signed the Bill of Rights, also acknowledged the importance of this commandment, declaring:

The moment the idea is admitted into society that property is not as sacred as the laws of God, and that there is not a force of law and public justice to protect it, anarchy and tyranny commence. If “Thou shalt not covet” and “Thou shalt not steal” were not commandments of Heaven, they must be made inviolable precepts in every society before it can be civilized or made free.132

- Many courts have also acknowledged the importance of this provision of the Decalogue. For example, in 1895, the California Supreme Court cited this prohibition as the basis of civil laws against defamation.133 In 1904, the Court of Appeals in West Virginia cited it as the basis of laws preventing election fraud.134 In 1958, a Florida appeals court cited it as the basis of laws targeting white-collar crime.135 And in 1951, the Oregon Supreme Court cited this Decalogue prohibition as the basis of civil laws against modern forms of cattle rustling.136 There are numerous other examples that all affirm that the tenth commandment of the Decalogue did indeed form an historical part of American civil law and jurisprudence.

OPINIONS OF THE FRAMERS OF OUR GOVERNMENT

- The Colonial, Revolutionary, and Federalist Era laws, as well as contemporary court decisions,137 provide two authoritative voices establishing that the Decalogue formed the historical basis for civil laws and jurisprudence in America. As a third authoritative voice, the Framers themselves endorsed those commandments, both specifically and generally.

- In addition to the approbation already given throughout this affidavit by John Adams, John Jay, Noah Webster, et. al, there are many other specific declarations, including that of William Findley, a soldier in the Revolution and a U. S. Congressman, who declared:

[I]t pleased God to deliver on Mount Sinai a compendium of His holy law and to write it with His own hand on durable tables of stone. This law, which is commonly called the Ten Commandments or Decalogue, . . . is immutable and universally obligatory. . . . [and] was incorporated in the judicial law.138

- Additionally, John Quincy Adams, who bore arms during the Revolution, served under four Presidents and became a President, and who was nominated (but declined) a position on the U. S. Supreme Court under President Madison, similarly declared:

The law given from Sinai was a civil and municipal as well as a moral and religious code; it contained many statutes . . . of universal application—laws essential to the existence of men in society, and most of which have been enacted by every nation which ever professed any code of laws. . . . Vain, indeed, would be the search among the writings of profane antiquity . . . to find so broad, so complete and so solid a basis for morality as this Decalogue lays down.139

- However, in addition to their specific references to the Decalogue, the Framers also used other terms to describe that code of laws—terms such as the “moral law.” For example, John Witherspoon, President of Princeton and signer of the Declaration, declared:

[T]he Ten Commandments . . . are the sum of the moral law.140

- Thomas Jefferson agreed, declaring that “the moral law” is that law “to which man has been subjected by his creator.”141

- The Framers also used a third descriptive term synonymous with the Decalogue and the moral law: the natural law. As Chief Justice John Jay, an author of the Federalist Papers, explained:

The moral, or natural law, was given by the sovereign of the universe to all mankind.142

- The Framers’ understanding of natural law must not be confused with the secular view of natural law embraced in Europe at that time. The American view of natural law was not secular—a fact made exceptionally clear by Justice James Wilson, a signer of the Constitution and the father of the first organized legal training in America. As Wilson explained:

As promulgated by reason and the moral sense, it has been called natural; as promulgated by the Holy Scriptures, it has been called revealed law. As addressed to men, it has been denominated the law of nature; as addressed to political societies, it has been denominated the law of nations. But it should always be remembered that this law, natural or revealed, made for men or for nations, flows from the same divine source; it is the law of God. . . . What we do, indeed, must be founded on what He has done; and the deficiencies of our laws must be supplied by the perfections of His. Human law must rest its authority ultimately upon the authority of that law which is divine. . . . Far from being rivals or enemies, religion and law are twin sisters, friends, and mutual assistants. Indeed, these two sciences run into each other. The divine law as discovered by reason and moral sense forms an essential part of both.143 The moral precepts delivered in the sacred oracles form part of the law of nature, are of the same origin and of the same obligation, operating universally and perpetually.144

- Notice additional evidence that the Framers considered “natural law” as a synonym for divine law:

In the supposed state of nature, all men are equally bound by the laws of nature, or to speak more properly, the laws of the Creator.145 Samuel Adams, Father of the American Revolution, Signer of the Declaration

[T]he laws of nature . . . of course presupposes the existence of a God, the moral ruler of the universe, and a rule of right and wrong, of just and unjust, binding upon man, preceding all institutions of human society and government.146 John Quincy Adams

The law of nature, “which, being coeval with mankind and dictated by God Himself, is, of course, superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times. No human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this.”147 Alexander Hamilton, Signer of the Constitution

The “law of nature” is a rule of conduct arising out of the natural relations of human beings established by the Creator and existing prior to any positive precept. . . . [These] have been established by the Creator, and are, with a peculiar felicity of expression, denominated in Scripture, “ordinances of heaven.”148 Noah Webster,Judge and Legislator

The law of nature being coeval with mankind, and dictated by God Himself, is of course superior to and the foundation of all other laws. . . . No human laws are of any validity if they are contrary to it; and such of them as are of any validity, derive all their force and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from their original.149 William Findley, Revolutionary Soldier, Member of Congress

[The] law established by the Creator, which has existed from the beginning, extends over the whole globe, is everywhere and at all times binding upon mankind. . . . [This] is the law of God by which He makes His way known to man and is paramount to all human control.150 Rufus King, Signer of the Constitution, Framer of the Bill of Rights

God . . . is the promulgator as well as the author of natural law.151 James Wilson, Signer of the Declaration and the Constitution, Original Justice on the U. Supreme Court

The transcendent excellence and boundless power of the Supreme Deity . . . [has] impressed upon them those general and immutable laws that will regulate their operation through the endless ages of eternity. . . . These general laws . . . are denominated the laws of nature.152 Zephaniah Swift, Author of America’s First Legal Text

- The Framers clearly considered that the natural law and the moral law, of which the Decalogue was a major component, provided the basis for our civil laws and jurisprudence.

- However, even if it should be argued that the Decalogue is nothing more than the embodiment of a religious rather than a secular code, even this, in the views of the Framers, would be insufficient grounds for its exclusion from the public arena. For example, Justice William Paterson, a signer of the Constitution placed on the Supreme Court by President George Washington, declared:

Religion and morality . . . [are] necessary to good government, good order, and good laws.153

- Justice Joseph Story, later appointed to the Supreme Court by President James Madison, similarly declared:

I verily believe Christianity necessary to the support of civil society.154 One of the beautiful boasts of our municipal jurisprudence is that Christianity is a part of the Common Law. . . . There never has been a period in which the Common Law did not recognize Christianity as lying its foundations.155 (emphasis added)

- John Adams, an accomplished attorney and an author of a commentary on the Constitution of the United States, similarly declared:

The study and practice of law . . . does not dissolve the obligations of morality or religion.156

- Dewitt Clinton, the Framer who introduced the 12th Amendment, also declared:

The laws which regulate our conduct are the laws of man and the laws of God. . . .The sanctions of the Divine law . . . cover the whole area of human action.157

- Perhaps the best reflection of the collective belief of the Framers that religion was not to be excluded from civil society is enactment of the Northwest Ordinance, one of the four organic laws of the United States.158 That law, passed in 1789 by the same Congress that framed the Bill of Rights, declared:

Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.159

- This federal law declares that “religion, morality, and knowledge” are necessary for “good government.” Expounding on the reasoning behind this belief, signer of the Declaration John Witherspoon, who served on over 100 committees while in Congress, declared:

[T]o promote true religion is the best and most effectual way of making a virtuous and regular people. Love to God and love to man is the substance of religion; when these prevail, civil laws will have little to do.160

- However, the Decalogue clearly is more than just a religious code. It—in its entirety—provides the base for much of America’s common law. As the Supreme Court of North Carolina declared in 1917:

Our laws are founded upon the Decalogue, not that every case can be exactly decided according to what is there enjoined, but we can never safely depart from this short, but great, declaration of moral principles, without founding the law upon the sand instead of upon the eternal rock of justice and equity.161

- In 1950, the Florida Supreme Court similarly declared:

A people unschooled about the sovereignty of God, the Ten Commandments, and the ethics of Jesus, could never have evolved the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution. There is not one solitary fundamental principle of our democratic policy that did not stem directly from the basic moral concepts as embodied in the Decalogue.162

CIVIL DISPLAYS

- Significantly, Americans seem to recognize the important contributions made to our society by the Decalogue. Consequently, there is a centuries old American propensity to honor both the Ten Commandments and Moses, the deliverer of the Decalogue.

- For example, in 1776 immediately following America’s separation from Great Britain, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were placed on a committee to design a seal for the new United States.163 Both of them separately proposed featuring Moses prominently in the symbol of the new nation. Franklin proposed “Moses lifting his wand and dividing the Red Sea”164 while Jefferson proposed “the children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night.”165

- A further indication of this American proclivity to honor Moses, the deliverer of the Ten Commandments, is seen in the U. S. Capitol. Adorning the top of the walls around the House Chamber are the side-view profile reliefs of 23 great lawgivers, including Hammurabi, Justinian, John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, William Blackstone, Hugo Grotius, George Mason, and 16 others. Significantly, there is only one relief of the 23 that is full faced rather than in profile, and that one relief is placed where it looks directly down onto the House Speaker’s rostrum, symbolically overseeing the proceedings of the lawmakers. That relief is of Moses.

- Not only Moses but also depictions of the Ten Commandments adorn several of the more important government buildings in the nation’s capitol. For example, every visitor that enters the National Archives to view the original Constitution and Declaration of Independence (and other official documents of American government) must first pass by the Ten Commandments embedded in the entryway to the Archives. Additionally, in the U. S. Supreme Court are displayed two depictions of the Ten Commandments. One is on the entry into the Chamber, where, engraved on the lower half of the two large oak doors, are the Ten Commandments. The other display of the commandments is in the Chamber itself on a marble frieze carved above the Justices’ heads. As Chief Justice Warren Burger noted in Lynch v. Donnelly:

The very chamber in which oral arguments on this case were heard is decorated with a notable and permanent—not seasonal—symbol of religion: Moses with the Ten Commandments.166

- Other prominent buildings where large displays of the Ten Commandments may be viewed include the Texas State Capitol, the chambers of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, and scores of other legislatures, courthouses, and public buildings across America. In fact, the Ten Commandments are more easily found in America’s government buildings than in her religious buildings, thus demonstrating the understanding by generations of Americans from coast to coast that the Ten Commandments formed the basis of America’s civil laws.

SUMMARY

- Historical evidence, drawn from civil law codes, judicial decisions, and declarations of great American lawgivers, affirms and reaffirms that the entire Decalogue has made a seminal contribution to the early common law and still continues today to make a significant contribution to the modern common law.

- The fact that some may not agree with all of the commandments of the Decalogue does not mean it should be prohibited from display any more than does the fact that not everyone agrees with all of the protections in the Bill of Rights requires that the Bill of Rights should not be displayed—or that because not everyone agrees with what the American flag represents requires the flag should not be displayed. Even though some may wish that the American ensign was the Stars & Bars rather than the Stars & Stripes, the reality is otherwise—and the reality is also that all ten of the commandments in the Decalogue had a unique, distinct, and significant impact on both American law and jurisprudence.

- To prohibit the display of the Decalogue simply because the first four commandments are more religious in nature than are the other six is like permitting the display of George Washington’s “Farewell Address” or Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech or the “Mayflower Compact” only if each document is displayed without its religious portions. In a display of any of the aforementioned works, it is not the advocation of religion that is occurring but rather the recognition of a significant historical contribution made to America that also happens to include religion.

- Aside from the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, it is difficult to argue that there is any single work that has had a greater or more far-reaching impact on four centuries of American life, law, and culture than the Decalogue. For this reason alone, the Decalogue merits display.

Footnotes

1 Americans United Statement in Response to the Family Research Council’s “Hang Ten” Campaign (November 4, 1999). Americans United for Separation of Church and State ; B. A. Robinson (July 1999). Posting of the Decalogue (Ten Commandments) in U. S. Courtrooms, Public Schools, Government Offices, etc. Religious Tolerance.org.

2 Marc D. Stern, The Ten Commandments: Innocent Display or Weapon in a Religious War? (January 1999). American Jewish Congress; the articles cited supra note 1.

3 Americans United, supra note 1.

4 B. A. Robinson, Religious Tolerance, supra note 1.

5 Noah Webster, Letters to a Young Gentleman Commencing His Education: To Which is Subjoined A Brief History of the United States (New Haven: S. Converse, 1823), 7; Noah Webster, A Collection of Papers on Political, Literary, and Moral Subjects (New York: Webster & Clark, 1843), 296.

6 B. A. Robinson, Religious Tolerance, supra note 1.

7 Americans United, supra note 1.

8 B. A. Robinson, Religious Tolerance, supra note 1.

9 Isaac Kramnick and Laurence Moore, The Godless Constitution (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996), 58-60 and passim.

10 Alvin W. Johnson, Sunday Legislation, XXIII Ky.L.J. 131, n 1 (1934-1935).

11 John Fiske, The Beginnings of New England (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1898), 127-128.

12 Select Charters and Other Documents Illustrative of American History, 1606-1775, William MacDonald, editor (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1899), 61, “Fundamental Orders of Connecticut” (1638-1639).

13 Colonial Origins, 163, “Government of Pocasset” (Rhode Island, 1638).

14 Select Charters, 68, “Fundamental Articles of New Haven” (1639).

15 Colonial Origins of the American Constitution: A Documentary History, Donald S. Lutz, editor (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1998), 250, “Preface to the General Laws and Liberties of Connecticut Colony” (1672).

16 The Code of 1650, Being a Compilation of the Earliest Laws and Orders of the General Court of Connecticut: Also, the Constitution, or Civil Compact, Entered into and Adopted by the Towns of Windsor, Hartford, and Wethersfield in 1638-9. To Which is Added Some Extracts from the Laws and Judicial Proceedings of New-Haven Colony Commonly Called Blue Laws (Hartford: Silas Andrus, 1825), pp. 28-29, “Capital Laws”; see also Select Charters, 87-88, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641), “Capital Laws”; Colonial Origins, pp. 102-103, “The Laws and Liberties of Massachusetts” (1647), “Capital Laws.”

17 The Code of 1650, 19; Select Charters, 73-74, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641); Colonial Origins, 71, “The Massachusetts Body of Liberties, 1641.”

18 Colonial Origins, 315-316, “Articles, Laws, and Orders, Divine, Politic and Martial for the Colony of Virginia” (1610-1611).

19 Colonial Origins, 83, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641).

20 Colonial Origins, 229, “Capital Laws of Connecticut” (1642); The Code of 1650, 28.

21 Colonial Origins, 6, “General Laws and Liberties of New Hampshire” (1680).

22 Noah Webster, Letters to a Young Gentleman, 8; Noah Webster, A Collection of Papers, 296.

23 Colonial Origins, 316, “Articles, Laws, and Orders, Divine, Politic and Martial for the Colony of Virginia” (1610-1611).

24 The Code of 1650, 28-29.

25 Select Charters, 87, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641).

26 Colonial Origins, 230, “Capital Laws of Connecticut” (1642).

27 Colonial Origins, 6, “General Laws and Liberties of New Hampshire” (1680).

28 Colonial Origins, 289, “An Act for Freedom of Conscience” (Pennsylvania, 1682).

29 An Abridgement of the Laws of Pennsylvania, Collinson Read, editor (Philadelphia: 1801), p. 32; see also Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, from the Fourteenth Day of October, One Thousand Seven Hundred, to the Twentieth Day of March, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Ten (Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1810), 7, “An Act for the Prevention of Vice and Immorality, and of Unlawful Gaming, and to Restrain Disorderly Sports and Dissipation, Passed April 22, 1794.”

30 Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1810), I:7, “An Act to Prevent the Grievous Sins of Cursing and Swearing within this Province and Territories.”

31 Alphabetical Digest of the Public Statute of South Carolina, Joseph Brevard, editor (Charleston: John Hoff, 1814), I:87-88, “Blasphemy-Profaneness” (1695).

32 A Manual of The Laws of North Carolina, Arranged Under Distinct Heads, In Alphabetical Order, John Haywood, editor (Raleigh: J. Gales, 1814), 264, “Vice and Immorality” (1741).

33 George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, John C. Fitzpatrick, editor (Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1931), Vol. III, 309, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Cambridge, July 4, 1775.

34 George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, Jared Sparks, editor (Boston: Ferdinand Andrews, 1836), II:167, n, from his “Orderly Book,” an undated order issued between June 25 and August 4, 1756.

35 Washington, Writings (1932), V:367, General Orders, Head-Quarters, New York, August 3, 1776.

36 Washington, Writings (1933), VIII:152-53, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Middle-Brook, May 31, 1777.

37 Washington, Writings (1936), XIII:118-19, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Fredericksburg, October 21, 1778.

38 The Public Statute Laws of the State of Connecticut, Book I (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), pp. 295-296, “An Act for the Punishment of divers Capital and other Felonies.”

39 The Laws of the State of New Hampshire, the Constitution of the State of New Hampshire, and the Constitution of the United States, with its Proposed Amendments (Portsmouth: John Melcher, 1797), pp. 280-281, “An Act for the Punishment of Profane Cursing and Swearing,” passed February 6, 1791, and pp. 286-287, a separate act passed February 10, 1791; see also Constitution and Laws of the State of New-Hampshire; Together with the Constitution of the United States (Dover: Samuel Bragg, 1805), p. 277, “An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes not Capital,” passed February 16, 1791.

40 Statutes of the State of Vermont (Bennington: Anthony Haswell, 1791), p. 51, “An Act for the Punishment of Drunkenness, Gaming, and Profane Swearing,” passed February 28, 1787, and p. 75, “An Act for the Punishment of Divers Capital and other Felonies,” passed March 8, 1787.

41 A Digest of the Laws of Virginia, which are of a Permanent Character and General Operation, Joseph Tate, editor (Richmond: Shepherd and Pollard, 1823) pp. 453-454; see also, The Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia: Being A Collection of all such Acts of the General Assembly, of a Public and Permanent Nature as are now in Force (Richmond: Thomas Ritchie, 1819), Vol. I, pp. 554-556, “An Act for the Effectual Suppression of Vice, and Punishing the Disturbers of Religious Worship and Sabbath Breakers.”

42 An Abridgment of the Laws of Pennsylvania (1801), p. 380, Act of April 22, 1794.

43 Jeremiah Perley, The Maine Justice; Containing the Laws Relative to the Powers and Duties of Justices of the Peace (Hallowell: Goodale, Glazier, & Co., 1823), pp. 7, 236; see also Laws of the State of Maine (Hallowell: Goodale, Glazier & Co., 1822), pp. 66-67, “An Act Against Blasphemy and Profane Cursing and Swearing,” passed February 24, 1821.

44 James Coffield Mitchell, The Tennessee Justice’s Manual and Civil Officer’s Guide (Nashville: J. C. Mitchell and C. C. Norvell, 1834), p. 428, “ Breaking the Sabbath.”

45 The Revised Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Passed November 4, 1835 (Boston: Dutton & Wentworth, 1836), p. 185, “Title VII: Of Towns and Town Officers,” Section 76.

46 George C. Edwards, Treatise of the Powers and Duties of the Justices of the Peace and the Town Officers in the State of New York (Ithaca: Mack, Andrus, & Woodruff, 1836), pp. 379-380, “Of Profane Cursing and Swearing,” Rev. Stat. 673, Art. 6.

47 Zephaniah Swift, A System of the Laws of the State of Connecticut (Windham: John Byrne, 1796), Vol. II, p. 320.

48 Church of the Holy Trinity v. U. S., 143 U. S. 457, 470-471 (1892).

49 Updegraph v. Commonwealth, 11 Serg. & Rawle 393, 401 (Penn. 1824).

50 Updegraph v. Commonwealth, 11 Serg. & Rawle 393, 403 (Penn. 1824).

51 State v. Mockus, 14 ALR 871, 874 (Maine Sup. Jud. Ct., 1921).

52 Cason v. Baskin, 20 So.2d 243, 247 (Fla. 1944) (en banc).

53 Jaqueth v. Town of Guilford School District, 189 A.2d 558, 563 (Vt. 1963), (Shangraw, J. dissenting).

54 State v. Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co., 143 S.W. 785, 803 (Mo. 1912).

55 Edwards, Justices of the Peace . . . in the State of New York, p. 38, “General Rules Applicable to a Summons, Warrant of Attachment,” Rev. Stat. 675.

56 Colonial Origins, p. 281, “Charter of Liberties and Frame of Government of the Province of Pennsylvania in America” (1682).

57 Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1810), Vol. I, p. 25, “An Act to Restrain People from Labor on the First Day of the Week,” passed October 14, 1705.

58 Statutes of the State of Vermont (1791), p. 157, “An Act for the Due Observation of the Sabbath,” passed March 9, 1787.

59 Swift, A System of the Laws, Vol. II, p. 326, “Of Crimes Against Religion.”

60 Laws of the State of New Jersey, Revised and Published Under the Authority of the Legislature, William Paterson, editor (New Brunswick: Abraham Blauvelt, 1800), pp. 329-330, “An Act for Suppressing Vice and Immorality,” passed March 16, 1798.

61 McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961).

62 Colonial Origins, pp. 316-317, “Articles, Laws, and Orders, Divine, Politic and Martial for the Colony of Virginia” (1610-1611).

63 Charles J. Hoadly, Records of the Colony or Jurisdiction of New Haven, From May, 1653, to the Union, Together With the New Haven Code of 1656 (Lockwood and Company, 1858), p. 605.

64 Colonial Origins, pp. 10-11, “General Laws and Liberties of New Hampshire” (1680).

65 Colonial Origins, p. 288, “An Act for Freedom of Conscience” (Pennsylvania, 1682).

66 Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, (1810), Vol. I, p. 25-26, “An Act to Restrain People from Labor on the First Day of the Week,” passed October 4,1705; see also Abridgement of the Laws of Pennsylvania (1801), p. 362.

67 Alphabetical Digest of the Public Statute Law of South Carolina (1814), Vol. II, pp. 272-275, “Title 160: Sunday.”

68 A Manual of The Laws of North Carolina (1814), p. 264, “Vice and Immorality” (1741).

69 The Public Statute Laws of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), Vol. I, pp. 577-578, “An Act for the Due Observation of the Sabbath, or Lord’s Day”; see also Swift, A System of the Laws, Vol. II, pp. 325-326.

70 Washington, Writings (1934), Vol. XI, p. 342, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Valley Forge, Saturday, May 2, 1778.

71 Washington, Writings (1931), Vol. III, p. 402-403, General Orders, Cambridge, August 5, 1775; Vol. VII, p. 407, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Morristown, April 12, 1777; Vol. VIII, p. 77, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Morristown, May 17, 1777; Vol. VIII, p. 114, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Morristown, May 24, 1777; Vol. VIII, p. 153, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Middle Brook, May 31, 1777; Vol. VIII, p. 308, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Middle Brook, June 28, 1777; Vol. IX, p. 275, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Pennybecker’s Mills, September 27, 1777; Vol. IX, p. 329, General Orders, Head-Quarters, Perkiomy, October 7, 1777; etc.

72 Statutes of the State of Vermont (1791), pp. 155-157, “An Act for the Due Observation of the Sabbath,” passed March 9, 1787.

73 The Revised Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Passed November 4, 1835 (1836), pp. 385-386, “Of the Observance of the Lord’s Day and the Prevention and Punishment of Immorality.”

74 The Revised Code of the Laws of Virginia (1819), Vol. I, pp. 554-556, “An Act for the Effectual Suppression of Vice, and Punishing the Disturbers of Religious Worship, and Sabbath Breakers,” passed December 26, 1792; see also A Digest of the Laws of Virginia (1823), pp. 453-454.

75 James Madison, The Papers of James Madison, Robert A. Rutland, editor (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), Vol. VIII, pp. 391-396, “Bills for a Revised State Code of Laws,” and Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Julian P. Boyd, editor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), Vol. II, p. 322, “The Revisal of the Laws, 1776-1786.”

76 Laws of the State of New Jersey (1800), pp. 329-333, “An Act for Suppressing Vice and Immorality,” passed March 16, 1798.

77 Constitution and Laws of the State of New Hampshire (1805), pp. 290-293, “An Act for the Better Observation of the Lord’s Day, and for Repealing All the Laws Heretofore Made for that Purpose,” passed December 24, 1799.

78 Laws of the State of Maine (1822), pp. 67-71, “An Act Providing for the Due Observation of the Lord’s Day.”

79 See, for example, William Waller Hening, The Virginia Justice, Comprising the Office and Authority of the Justice of the Peace in the Commonwealth of Virginia (Richmond: Shepherd & Pollard, 1825), p. 612, “Sabbath Breakers”; see also Coffield, The Tennessee Justices’ Manual (1834), pp. 427-428; see also Edwards, Justices of the Peace . . . in the State of New York (1836), pp. 386-387; etc.

80 Bertera’s Hopewell Foodland, Inc. v. Masters, 236 A.2d 197, 200-201 (Pa. 1967).

81 Paramount-Richards Theatres v. City of Hattiesburg, 49 So.2d 574, 577 (Miss. 1950).

82 People v. Rubenstein, 182 N.Y.S.2d 548, 550 (N.Y. Ct. Sp. Sess. 1959).

83 Stollenwerck v. State, 77 So. 52, 54 (Ala. Ct. App. 1917) (Brown, P. J. concurring).

84 Gillooley v. Vaughn, 110 So. 653, 655 (Fla. 1926), citing Theisen v. McDavid, 16 So. 321, 323 (Fla. 1894), citing cases in Oregon and Kentucky.

85 Rogers v. State, 4 S.E.2d 918, 919 (Ga. Ct. App. 1939).

86 Brimhall v. Van Campen, 8 Minn. 1 (1858), cited in Kentucky Law Journal, Vol. XXIII, 1934-1935, Alvin W. Johnson, “Sunday Legislation,” p. 140.

87 John Jay, The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, Henry P. Johnston, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), Vol. IV, pp. 403, to John Murray Jr., on April 15, 1818.

88 City of Ames v. Gerbracht, 189 N.W. 729, 733 (Iowa 1922).

89 B. A. Robinson, Religious Tolerance, supra note 1.

90 Sumpter v. State, 261 Ind. 471, 306 N.E.2d 95, 101 (Ind. 1974); see also State v. Schultz, 582 N.W.2d 113, 117 (Wis. Ct. App. 1998).

91 The Code of 1650, p. 29; see also Colonial Origins, p. 230, “Capital Laws of Connecticut” (1642).

92 See, for example, Colonial Origins, p. 7, “General Laws and Liberties of New Hampshire” (1680); and p. 103, “The Laws and Liberties of Massachusetts” (1647); etc.

93 Ruiz v. Clancy, 157 So. 737, 738 (La. Ct. App. 1934), citing Caldwell v. Henmen, 5 Rob. 20.

94 See, for example, Pierce v. Yerkovich, 363 N.Y.S.2d 403, 414 (N.Y. Fam. Ct. 1974); see also Mileski v. Locker, 178 N.Y.S.2d 911, 916 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1958); see also Beaty v. McGoldrick, 121 N.Y.S.2d 431, 432 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1953).

95 Noah Webster, Letters of Noah Webster, Harry R. Warfel, editor (New York: Library Publishers, 1953), pp. 453-454, to David McClure on October 25, 1836.

96 Select Charters, pp. 87-88, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641); see also Colonial Origins, pp. 83-84, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641).

97 Colonial Origins, p. 230, “Capital Laws of Connecticut” (1642).

98 Constitution and Laws of the State of New-Hampshire; Together with the Constitution of the United States (Dover: Samuel Bragg, 1805), p. 267; see also Colonial Origins, p. 7, “General Laws and Liberties of New Hampshire” (1680).

99 Young v. Commonwealth, 53 S.W. 963, 966 (Ky. Ct. App. 1932).

100 John Jay, Correspondence, Vol. IV, pp. 403-404, to John Murray Jr., on April 15, 1818.

101 See, for example, Matter of Storar, 434 N.Y.S.2d 46, 48 (N.Y. App. Div. 1980) (Cardamone, J. dissenting); see also Ex parte Mei, 192 A. 80, 82 (N.J. 1937); etc.

102 Colonial Origins, p. 84, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641).

103 The Code of 1650, pp. 28-29; see also Colonial Origins, p. 230, “Capital Laws of Connecticut” (1642).

104 Colonial Origins, pp. 189-190, “Acts and Orders of 1647” (Rhode Island).

105 Colonial Origins, pp. 8-9, “General Laws and Liberties of New Hampshire” (1680).

106 Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1810), Vol. I, pp. 25-27, “An Act Against Adultery and Fornication,” passed in 1705.

107 Statutes of the State of Vermont (1791), pp. 16-17, “An Act Against Adultery, Polygamy, and Fornication,” passed March 8, 1787.

108 See, for example, Swift, A System of the Laws, Vol. II, pp. 327-328; see also Constitution and Laws of the State of New Hampshire (1805), pp. 278-279, “An Act for the Punishment of Lewdness, Adultery, and Polygamy”; see also Perley, The Maine Justice (1823), p. 6; etc.

109 Hardin v. State, 46 S.W. 803, 808 (Tex. Crim. App. 1898).

110 Schreifels v. Schreifels, 287 P.2d 1001, 1005 (Wash. 1955).

111 See, for example, Barbour v. Barbour, 330 P.2d 1093, 1098 (Mont. 1958); see also Petition of Smith, 71 F.Supp. 968, 972 (D.N.J. 1947); see also S.B. v. S.J.B., 609 A.2d 124, 125 (N.J. Super. Ct. Ch. Div. 1992); etc.

112 James Kent, Commentaries on American Law (New York: O. Halsted, 1826), Vol. I, p. 7.

113 Succession of Onorato, 51 So.2d 804, 810 (La. 1951).

114 Hollywood Motion Picture Equipment Co. v. Furer, 105 P.2d 299, 301 (Cal. 1940).

115 State v. Donaldson, 99 P. 447, 449 (Utah 1909).

116 De Rinzie v. People, 138 P. 1009, 1010 (Colo. 1913).

117 Addison v. State, 116 So. 629 (Fla. 1928) and Anderson v. Maddox, 65 So.2d 299, 301-302 (Fla. 1953).

118 State v. Gould, 46 S.W.2d 886, 889-890 (Mo. 1932).

119 Doll v. Bender, 47 S.E. 293, 300 (W.Va. 1904) (Dent, J. concurring).

120 Pennsylvania Co. v. United States, 214 F. 445, 455 (W.D.Pa. 1914).

121 The Code of 1650, pp. 28-29; see also Colonial Origins, p. 230, “Capital Laws of Connecticut” (1642).

122 Colonial Origins, p. 84, “Massachusetts Body Of Liberties” (1641); see also, Select Charters, p. 88.

123 Colonial Origins, pp. 190-191, “Acts and Orders of 1647,” (Rhode Island).

124 Colonial Origins, p. 7, “General Laws and Liberties of New Hampshire” (1680).

125 The Public Statute Laws of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), p. 295, “An Act for the Punishment of Divers Capital and Other Felonies.”

126 Watts v. Gerking, 228 P. 135, 141 (Or. 1924).

127 Hosford v. State, 525 So.2d 789, 799 (Miss. 1988).

128 L——— v. N———, 326 S.W.2d 751, 755-756 (Mo. Ct. App. 1959).

129 People v. Rosen, 20 Cal.App.2d 445, 448-449, 66 P.2d 1208 (1937).

130 Pullum v. Johnson, 647 So.2d 254, 256 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1994).

131 William Penn, Fruits of Solitude, In Reflections and Maxims Relating To The Conduct of Human Life (London: James Phillips, 1790), p. 132.

132 John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1851), Vol. VI, p. 9, “A Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America.”

133 Weinstock, Lubin & Co. v. Marks, 42 P. 142, 145 (Cal. 1895).

134 Doll v. Bender, 47 S.E. 293, 300-01 (W.Va. 1904) (Dent, J. concurring).

135 Chisman v. Moylan, 105 So.2d 186, 189 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1958).

136 Swift & Co. v. Peterson, 233 P.2d 216, 231 (Or. 1951).

137 A search of court decisions just from 1880 to 1975 records that the Decalogue was cited authoritatively and approvingly in well over five hundred cases.

138 William Findley, Observations on “The Two Sons of Oil” (Pittsburgh: Patterson & Hopkins, 1812), pp. 22-23, 36.

139 John Quincy Adams, Letters of John Quincy Adams, to His Son, on the Bible and Its Teachings (Auburn: James M. Alden, 1850), pp. 61, 70-71.

140 John Witherspoon, The Works of John Witherspoon (Edinburgh: J. Ogle, 1815), Vol. IV, p. 95, “Seasonable Advice to Young Persons,” February 21, 1762.

141 Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington, D. C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1903), Vol. III, p. 228, from his “Opinion on the Question whether the United States have a Right to Renounce their Treaties with France or to Hold them Suspended till the Government of that Country shall be Established,” on April 28, 1793.

142 John Jay, The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, Henry P. Johnston, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), Vol. IV, p. 403, letter to John Murray Jr. on April 15, 1818.

143 James Wilson, The Works of the Honorable James Wilson, Bird Wilson, editor (Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press, 1804), Vol. I, pp. 104-106, “Of the General Principles of Law and Obligation.”

144 Wilson, Works, p. 138, “Of the Laws of Nature.”

145 Samuel Adams, The Writings of Samuel Adams, Harry Alonzo Cushing, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1908), Vol. IV, p. 356, To the Legislature of Massachusetts on January 17, 1794.

146 John Quincy Adams, The Jubilee of the Constitution (New York: Samuel Colman, 1839), pp. 13-14.

147 Alexander Hamilton, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 1768-1778, Harold C. Syrett, editor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), Vol. I, p. 87, from “The Farmer Refuted,” February 23, 1775, quoting from Blackstone.

148 Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), s.v. “law,” definitions #3 and #6.

149 Findley, Observations on “The Two Sons of Oil,” pp. 33-34.

150 Rufus King, The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King, Charles R. King, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900), Vol. VI, p. 276, to C. Gore on February 17, 1820.

151 Wilson, Works, Vol. I, p. 64, “Of the General Principles of Law and Obligation.”

152 Swift, A System of the Laws, Vol. I, pp. 6-7.

153 William Paterson, United States Oracle (Portsmouth, NH), May 24, 1800; see also The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800, Maeva Marcus, editor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), Vol. III, p. 436.

154 Joseph Story, Life and Letters of Joseph Story, William W. Story, editor (Boston: Charles C. Little, and James Brown, 1851), Vol. I, p. 92, in a letter on March 24, 1801.

155 Story, Life and Letters, Vol. II, p. 8.

156 John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), Vol. II, p. 31, from his diary entry for Sunday, August 22, 1756.

157 William W. Campbell, The Life and Writings of De Witt Clinton (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1849), pp. 305, 307.

158 United States Code Annotated (St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1987), “The Organic Laws of the United States of America,” p. 1. This work lists America’s four fundamental laws as the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Northwest Ordinance.

159 The Constitutions of the United States of America With the Latest Amendments (New York: Evert Duyckinck, 1813), p. 375, “An Ordinance of the Territory of the United States Northwest of the River Ohio,” Article III.

160 John Witherspoon, The Works of John Witherspoon (Edinburgh: J. Ogle, 1815), Vol. VII, pp. 118-119, Lecture XIV, “Jurisprudence.”

161 Commissioners of Johnston County v. Lacy, 93 S.E. 482, 487 (N.C. 1917).

162 State v. City of Tampa, 48 So.2d 78, 79 (Fla. 1950).

163 B. J. Cigrand, Story of the Great Seal of the United States (Chicago: Cameron, Amberg & Co, 1892), pp. 103-147.

164 John Adams, Letters of John Adams Addressed to His Wife, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1841), Vol. I, p. 152, letter to Abigail Adams on August 14, 1776.

165 Adams, Letters, Vol. I, p. 152, letter to Abigail Adams on August 14, 1776.

166 166 Lynch v. Donnelly, 465 U. S. 668, 677 (1984).

* This article concerns a historical issue and may not have updated information.

To contact your Representative or Senator: From a constitutional perspective, it is unconscionable that the current policy penalizing the free speech of religious institutions has remained intact and unchallenged for this long. The government has long recognized that institutions of faith and houses of worship have provided vital services to our communities and our nation. In fact, our public policy has been to honor the valuable contributions of these organizations with an exemption from taxes both for the organizations themselves and for the individuals and groups who support them. Regrettably, because of a simple appropriations rider in 1954, our public policy changed to recognizing the valuable contributions of houses of worship only if they gave up their constitutional right to free speech. (What an amazing exchange: we will honor your charitable contributions but only if you will give up your constitutional rights!) This obviously represents bad public policy and unjustly muzzles thousands of churches across America by preventing them from exercising their fundamental right to free speech. Free speech is most valuable when it is exercised during the elections of our government leaders.