John Clarke (1755-1798) biography

Born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Clarke grew up in a strongly patriotic family during the American War for Independence. In fact, his uncle, Timothy Pickering, was not only a military general under George Washington and later became Postmaster General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State under President Washington. Clark graduated from the Boston Public Latin School in 1761, while only six years old. In 1774 at the age of nineteen, he graduated from Harvard. He returned for his Master’s Degree (1777), and then studied theology, receiving his Doctor of Divinity from the University of Edinburgh. He took a job on the staff of First Church of Boston, alongside the great preacher Dr. Charles Chauncy, who himself had been a significant influence in the years leading up to the American War for Independence. When Chauncy died in 1787, Clarke became pastor, where he continued until he suffered a stroke while preaching in 1798, passing away the next day at the age of forty-three. A two-volume set of his sermons were published after his death. The following sermon was the one he preached at the interment of the Rev. Samuel Cooper of Boston on January 2, 1784. (Note: the Rev. Cooper was a highly influential clergyman, identified by Founding Father John Adams as one of the individuals “most conspicuous, the most ardent, and influential” in the “awakening and revival of American principles and feelings” that led to American independence.)

AN

ANSWER

TO THE

QUESTION

WHY ARE YOU A CHRISTIAN?

BY JOHN CLARKE

Minister of a Church in Boston

AN ANSWER TO THE QUESTION, “WHY ARE YOU A CHRISTIAN?”

Not because I was born in a Christian country, and educated in Christian principles; — not because I find the illustrious Bacon, Boyle, Locke, Clarke, and Newton, among the professors and defenders of Christianity; – nor merely because the system itself is so admirably calculated to mend and exalt human nature: but because the evidence accompanying the Gospel, has convinced me of its truth. The secondary causes, assigned by unbelievers, do not, in my judgment, account for the rise, progress, and early triumphs of the Christian religion. Upon the principles of skepticism, I perceive an effect without an adequate cause. I therefore, stand acquitted to my own reason, though I continue to believe and profess the religion of Jesus Christ. Arguing from effects to causes, I think, I have philosophy on my side. And reduced to a choice of difficulties, I encounter not so many, in admitting the miracles ascribed to the Saviour, as in the arbitrary suppositions and conjectures of his enemies.

That there once existed such a person as Jesus Christ; that he appeared in Judea in the reign of Tiberius; that he taught a system of morals, superior to any inculcated in the Jewish schools; that he was crucified at Jerusalem; and that Pontius Pilate was the Roman governor, by whose sentence he was condemned and executed, are facts which no one can reasonably call in question. The most inveterate deists admit them without difficulty. And indeed to dispute these facts would be giving the lie to all history. As well might we deny the existence of Cicero, as that of a person by the name of Jesus Christ. And with equal propriety might we call in question the orations of the former as the discourses of the latter. We are morally certain, that the one entertained the Romans with his eloquence; and the other enlightened the Jews with his wisdom. But it is unnecessary to labor these points, because they are generally conceded. They, who affect to despise the Evangelists and Apostles, profess to reverence Tacitus, Suetonius, and Pliny. And these eminent Romans bear testimony to several particulars, which relate to the person of Jesus Christ, his influence as the founder of a sect, and his crucifixion. From a deference to human authority, all therefore, acknowledge, that the Christian religion derived its name from Jesus Christ. And many are so just to his merits, as to admit that he taught better than Confucius; and practiced better than Socrates or Plato.

But, I confess, my creed embraces many more articles. I believe, that Jesus Christ was not merely a teacher of virtue, but that he had a special commission to teach. I believe, that his doctrines are not the work of human reason, but divine communications to mankind, I believe, that he was authorized by God to proclaim forgiveness to the penitent; and to reveal a state of immortal glory and blessedness to those who fear God, and work righteousness. I believe, in short, the whole evangelic history, and of consequence, the divine original of Christianity, and the sacred authority of the Gospel. Others may reject these things as the fictions of human art or policy. But I assent to them, from a full conviction of their truth. The grounds of this conviction, I shall assign in the course of this work. And I shall undertake to show, why the objections of infidelity, though they have often shocked my feelings have never yet shaken my faith.

To come then to the Question : WHY ARE YOU A CHRISTIAN? I answer, because the Christian religion carries with it internal marks of its truth; because not only without the aid, but in opposition to the civil authority, in opposition to the wit, the argument, and violence of its enemies, it made its way; and gained an establishment in the world: because it exhibits the accomplishment of some prophecies; and presents others, which have been since fulfilled : and because its author displayed an example, and performed works, which bespeak, not merely a superior, but a divine character. Upon these several facts, I ground my belief as a Christian. And, till the evidence on which they rest, can be invalidated by counter evidence, I must retain my principles and my profession.

Section I.

The internal evidence of Christianity.

First—I am a Christian, because the intrinsic excellency of Christianity points it out as a system worthy of my belief; because the laws which it prescribes, the spirit which it breathes and the discoveries which it makes, are so admirably suited to the constitution and circumstances of man, that I cannot reject it. The perceptive part of Christianity has been very generally approved. And how is it possible, that any one should seriously object to laws, which tend to correct the errors, and reform the vices of human nature; and to exalt the character of man to the highest stage of moral perfection? If Christianity prescribed the austerities of the monk, the solitude of the hermit, or the wanderings of the pilgrim; if it even gave countenance to such extravagancies or allowed them the lowest degree of merit, I should esteem it a formidable objection to the system. But nothing of this description can be found in the writings of the Evangelists or Apostles. Those writings pure contempt upon al superstitious practices; and lead us to ascribe no value to any works, but those of true piety and virtue. They teach us to worship God in spirit and in truth; to love him supremely; to be grateful for his favors, and resigned to his dispensations; to trust his mercy, and rejoice in his government. They teach us to love our neighbor as ourselves; to forgive him when he has injured us; to bear with his infirmities, and to excuse his follies; to weep with him in his distresses; when he is in want, to afford him our assistance; and to do to him, as we should think it fit and reasonable, that he should do to us. They teach us to love even our enemies, so far at least, as to abstain from revenge; and to render them offices of kindness, when their circumstances call for commiseration. They teach us to govern our appetites and passions to be chaste, humble, temperate, pure, and as much as possible to be like our father in heaven, whose character is an assemblage of every natural and moral perfection. They teach children to reverence and obey their parents; and parents to love, instruct, and provide for their children. They teach the husband conjugal fidelity and affection; and the wife, the peculiar duties of her station, and the amiable virtues which adorn the sex; and bless the marriage union. They teach masters lenity, and the servants faithfulness. They teach rulers to exercise their authority for the public good; and persons in private life, not to withhold honor and submission from those, under whose wise and just administration, they lead quiet and peaceable lives. I a word, the affluent and the poor, the prosperous and the afflicted the aged and the young, may all find their duty in the sacred books. And the duties, there enjoined, are such as the enlightened reason of every man must approve.

These sublime lessons of morality are found in various parts of the New Testament. They enrich the divine sermon on the mount. And they are contained in the excellent parables delivered by Jesus Christ. I also find them in the discourses of the Apostles, and in their pastoral letters. I may say, wherever I open the Christian volume, I find some direction which if properly observed, would render me a good neighbor, a good member of society, a good friend, and a good man! And it is possible for me to doubt the divine original of a system, which furnishes such rules; and contemplates so glorious an object?

If the prohibitions of Jesus Christ were universally regarded, and his laws obeyed, what blessings would pour in on society? There would be no wars among the nations of the earth. There would be no oppression. There would be neither tyrants nor slaves. Every ruler would be just; every citizen would be honest; every parent would be faithful to his charge; every child would be dutiful; the purest affection would recommend domestic life; and neighbors would be mutual blessings. Under the dominion of Christianity, envy, pride, and jealousy would give way to the most enlarged benevolence. Human nature would recover its dignity. And every man would reap the present reward of his own virtues.

From these facts, others may draw their own conclusions : my inference is, that Christianity is true. I do not believe, that such a system of morals can be the work of human wisdom. That these laws originated with God; and that Jesus Christ was commissioned to promulgate them, appears to me a much more rational supposition. The more I inspect them, the less am I inclined to compliment human ingenuity with so glorious a production. If then, I continue to believe in this age of refinement, and free inquiry, it is because I am unable to resist the evidence arising from the transcendent excellency of the Christian precepts. I think it infinitely more probable, that they should be a communication from God, than that philosophy should justly claim the honor of the invention.

The doctrines of the Christian religion furnish an additional argument in its favor. They are such as appear worthy of God and answerable to the natural expectations of men. The perfections of the Deity, his agency in the creation and government of the world, the conditions of his approbation, the consequences, and a future state of existence, are points, respecting which every reasonable being would wish for information. And it is a fact, that the New Testament throws divine light on all these articles. It informs us, that there is One God; that he is infinitely holy, wise, benevolent, and just; that he is self-existent and independent; that his power is irresistible, and his presence universal; that he made and upholds all worlds; that he created the human species, and every inferior being; that he is moreover, their preserver and benefactor; that he exercises a moral government over man; that he requires obedience to his laws, and consequently, resents their infraction; that forgiveness is possible, and repentance and reformation the conditions; that death is not utter destruction; that all who die, will live again; that all who are raised, will be judged; and that there is a future state, in which virtue will shine with unfading luster, and receive an everlasting reward. These are not useless speculation, but doctrines of infinite moment. They interest as well the heart, as the understanding. And their influence extends both to our actions and our enjoyments.

It would be easy to produce the various passages, in which these points are maintained. But it is unnecessary; as everyone will allow them to be doctrines of Christianity. Whether the system be true or not, it certainly contains these articles. I would now put the question to every sober Theist, whether I must renounce either my understanding, or my creed? Is there anything incredible in this representation of God and man, of the demands of the one, and the destination of the other? Must I offer an affront to my reason, if I believe in one God, exercising the authority; and possessed of all the glorious attributes, ascribed to him in the Christian writings? Does my understanding revolt at the evangelical account of his providence and moral government? That I should make it my study to obey him; when guilty of disobedience, that I should repent and reform; and that, as I behave so I may expect to be treated; is there anything irrational in these doctrines? We read of a mediator, and a rich variety of blessings dispensed through him; and is not this agreeable to the established constitution of things in the world? Do not temporal mercies often flow to us through the mediation of others? And may not many instances be produced, in which the political redemption of a nation has been accomplished by the labors; or purchased by the blood of some virtuous patriot? Is common sense insulted by the doctrine of a resurrection? This has been asserted; but with what reason, I never could conceive. When I examine the power and wisdom of God, they do not appear incompetent to such an affect. When I consider the divine goodness, I see nothing in the resurrection of man irreconcilable with that perfection. And when I reflect, that God formed the human body; and inspired the breath of life, I can easily believe, that he is able to raise us up at the last day. Before I can reject the resurrection of mankind, it must therefore be demonstrated that the terms imply a contradiction.

As to a future state of retribution, I would ask, what presumption there is against it. We find, that we have already experienced great changes. Since our first introduction to this world, our active and intellectual powers have gained strength, as we have advanced towards maturity. And why may we not hereafter possess them in higher perfection? Why may we not move, not merely in a new, but in a nobler sphere? And as a moral government is evidently begun in this state, why may it not be completed in another? In these expectations, I think we are supported by the analogy of nature. As we have already existed in different states, new scenes may be in reserve for us; and new capacities of action, enjoyment, and suffering may await us beyond the grave.

Combining the doctrines and precepts of Christianity, I am led then to infer from them the truth of the system. Because the former are so important, and the latter so beneficial; because the doctrines of Christ tend to make us so wise, and hiss laws so good, I am , in a manner, compelled to receive them as divine. Such is their supreme excellence, that I must ascend to heaven for an adequate cause. I assent therefore, most unfeignedly to those words of our savior, “my doctrine is not mine, but his who sent me.” And I do Assert, were there no other evidence that our religion is from God, it would be more reasonable to admit its claims to a divine original, than to reject them.

Section II.

Evidence arising from the early triumphs of Christianity.

But my faith, as a Christian, does not rest on this single foundation. I have other reasons for believing the Gospel. The early triumphs of Christianity furnish a Second, and in my view, a most weighty argument in support of my religion. And my conviction of its truth gains strength every time I examine its introduction, progress, and establishment in the world. Recurring to the period of its infancy, I find, that it made its way not only without the aid, but in opposition to the civil authority. I observe, that it rose superior to the wit, the argument, and the violence of its enemies. I perceive, that it baffled the arts of the Jewish priests and rulers; and supported itself against the rage of the multitude. When Heathens become its enemies and persecutors, I find their opposition as ineffectual as that of the Jews. Though it was the contempt and derision of the more leading characters in society, yet I take notice, that it gained a wonderful ascendency over the human mind; and at length became the religion of the Roman world. These are facts : and how am I to account for them, if Christianity be a mere fable?

I can easily believe, that an imposture may succeed, if it have the public prejudices, the learning, wealth, and influence of the country, or the sword of the magistrate on its side. I never wondered that the attempts of Mahomet to establish his religion, were crowned with successes. When I peruse the Koran, and examine the materials of which it is composed; —when I observe how much art the whole is accommodated to the opinions and habits of Jews, Christians, and Pagans; —when I consider what indulgences it grants, and what future scenes it unfolds; —when I advert to the peculiar circumstances of the times, when its author formed the vast design of assuming the royal and prophetic character; —and more than all, when I contemplate the reformer at the head of a conquering army, the Koran in one hand, and in the other, a sword, — I cannot be surprised at the civil and religious revolution which has immortalized his name. With his advantages, how could he fail of success? Everything favored the enterprise. The nations beheld a military apostle. And they, who were unconvinced by his arguments, trembled at his sword.

But did Jesus Christ have recourse to such measures in order to establish his religion? Was he a general, or his apostles soldiers? In proof of his divine mission, did he affront the reason of mankind, by appealing to the sword? Did the learning of the age come to his assistance? Di genius and eloquence plead his cause? Were the principles of his religion such as would easily captivate persons of figure and fashion? Would wealth be partial to them? It is granted, that the laws of Christianity are perfectly accommodated to the reasonable, and moral nature of man; but did the habits of the age, in which they were promulgated, predispose the public mind to receive those laws? An were the doctrines of the gosp0el consonant to prevailing and popular opinions? There is not a man, who has examined the life, the actions, and the religion of Jesus Christ, Who will answer one of these queries in the affirmative.

In the whole compass of history, no fact is better established than the pacific character of our great master, and the inoffensive measures by which he prosecuted his cause. He proclaimed the truths; and inculcated the duties of his religion; but he used no violence to make men believe the one, or practice the other. He addressed himself to the reason of mankind; and then let them to make up their own judgment. At length he suffered; and his cause developed upon certain persons who had attended upon his ministry, and been witnesses of his actions. These persons, called apostles, went forth into the world; and taught the same truths, which they had learned from their master, and which he had sealed with his blood. In imitation of their great pattern, they likewise applied, not to the passions, but to the reason of the age. With the Jews, they argued on their own principles. And for the conviction of Gentile, they appealed to facts. Not one of their enemies ever pretended, that more formidable weapons were employed by the apostles in the Christian Cause. How then shall we account for their success? What induced several thousands of the Jewish nation to embrace Christianity? And why did such multitudes of the Gentile world forsake their superstitions; and receive the religion of the Gospel?

Was Christianity a popular system? None could be less so. Did it open the way to a seat in the Sanhedrim, to the honors of the priesthood, or to an office under the Roman government? I never heard the insinuation. Was it an introduction to wealth or power? It was the very reverse. Did it flatter any of the ruling passion of the human heart, or permit their gratification? Every one, who has examined it, knows the contrary. If then, as the terms are generally understood, it was neither honorable, profitable, nor popular; — if it was the derision of philosophy, and the contempt of learning; — if the wit of the age was exerted against it, — if the priesthood hated, and the magistrate persecuted it, to what cause am I to ascribe the prevalence of Christianity? Under all these disadvantages, what enabled it to keep its ground? Upon one principle only, can I account for this fact to my own satisfaction, and that is the truth of the system, and the patronage of heaven. I can believe, that truth may triumph over the most formidable opposition; and that God is able to defend his own cause.

For every phenomenon in nature, there must be a sufficient reason. This is a doctrine of philosophy; and not only so, but a dictate of common sense. Taking this principle for granted, I therefore, endeavor to account for the existence of Christianity. I find, that the religion of Jesus is not coeval with many events preserved in history. By means of various records, which have escaped the ravages of time, I perceive, that less than eighteen centuries will carry me back to the age, in which this religion was first proposed to the world. By the confession of its enemies, it derived no support from the family connections, outward circumstances, or fate of its author. So far from it, all these things operated against it. Jesus Christ, though a very excellent, was in the estimation of the world, a very obscure person. His family though once exalted, had fallen into decay. And his fate was as infamous as it was unmerited. His followers likewise, and those with whom he left his cause, were generally as obscure as their master, they had not wealth, to give them importance. They were not men in power. Nor were their natural abilities, or literary attainments so great, as to give them a decided superiority over their enemies. It is certain therefore, that Christianity did not woe its successes to anything dazzling in the personal accomplishments or circumstances of its first preachers.

Where then, shall I look for the cause? The religion of Christ did prevail; though to persons of figure and influence, its author was an object of contempt; and though his fate was that of the vilest malefactor. It did make its way; though its ministers were the farthest possible from that description of men, who take the lead in society; whose example it is their ambition to follow. It did succeed; though it bore an uniform testimony against all the impiety and immorality practiced in the world. Without flattering one disorderly passion of the human hart, without accommodating itself to one corrupt habit, it triumphed over the prejudices of multitudes. And whilst its profession was attended with every temporal discouragement, not only the provinces, but the very city of Rome, abounded with Christians! I ask the question once more, if Christianity be a fable how am I to account for this revolution?

I well know the solution which modern ingenuity has proposed. Gibbon’s secondary causes I have repeatedly examined; I would hope, with impartiality: I certainly have done it with attention. But they never gave me satisfaction; and for a reason, which the great Sir Isaac Newton shall assign. He says, that a cause must be known to exist; and that it must be adequate to an effect, before it can be admitted into sound philosophy; and before such effect can with propriety, be referred to it. But the causes, assigned by those who reject the Christian religion, appear to want both these conditions. We have no proof that many of them ever existed. And united, they seem utterly inadequate to explain the various appearances; and account for the phenomena, to which they have been applied. I am therefore a Christian, because the early conquests of Christianity will not suffer me to reject it as a fable.

Section III.

Evidence arising from the completion of prophecy.

But though conclusive, yet these are not the only arguments which give authority to the Gospel. The completion of prophecy furnishes a Third reason for that reverence, which I feel for Christianity; and for my assent to it as a divine religion. In perusing the Jewish and Christian writings, I find several predictions. Some of these preceded the savior; and others were uttered by him. Some were accomplished in him; and others in events, which took place after his appearing. Examples of each I shall first exhibit; and then show, why they determine me to be a Christian.

It was predicted that the Messiah should come, “before the scepter departed from Judah.” And does not history confirm this prediction? Did not Jesus Christ appear and suffer, before the Jewish government was subverted by the Romans? It was predicted, that “he should come whilst the second temple was standing” and that the house should derive glory from the occasional visits of so great a character. And was not this prophecy fulfilled? It was predicted, that he should come “in four hundred and ninety years,” from the time in which the city of the Jews should recover from the disgrace, under which it had lain during the captivity; that he should “be cut off;” and that “Jerusalem and the temple should be afterwards made desolate.” And did not these things happen in the order, and at the period here described? It was predicted, that in that age of the Messiah many astonishing works should be performed. And were not such works performed by Jesus Christ? At least, is it not an article in his history, that through his benevolent interposition, and in consequence of his supernatural powers, the blind received their sight, the lame walked, the deaf heard, the dumb spake, the sick recovered, and the dead revived? Finally, it was predicted, that “he should enter the holy city in triumph;” that his enemies should conspire against him; that “he should be sold for thirty pieces of silver;” that “he should be scourged,” and treated with every species of contempt; that his persecutors should “spit upon him;” that they should “pierce his hands and feet;” that the spectators of his crucifixion should mock him; that “the soldiers should draw lots for his garment;” that he should be numbered with transgressors; that “gall and vinegar” should be presented to him, when in his last agonies; and that he should “make his grave with the rich.” And in the history of Christ, have we not the completion of these prophecies? Comparing the predictions and the events, can we deny, that the latter are a perfect counterpart to the former?

But the person, whose fate was so particularly foretold, was himself a prophet. On various occasions, he declared to his followers, that he should suffer a violent death. He predicted, that his own countrymen would condemn him; and the Gentiles execute the sentence. He foretold the cowardice of Peter, the treachery of Judas, the terror and flight of all his disciples, when he should be arrested, his resurrection from the grave, the effusion of the holy spirit, the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple, with all the horrors attending it the dispersion of the Jews, the persecutions of his followers, and the success of the Gospel, notwithstanding the opposition, which would be made by its enemies.

And, according to the records of that age, did not all these things come to pass? Have we not the highest evidence, which history can afford, that Jesus Christ both suffered, and triumphed in the manner, which he had before described? Were not his disciples hated of all men? Were not the most wanton cruelties exercised upon them? And did not the time come, when their extermination from the earth was contemplated as a sacrifice, which the honor of God, the interests of truth, and the good of society required? Was not Jerusalem destroyed by the Romans? And as to the temple, did the resentment of the conquering army leave one stone of that magnificent building on another? Before their reduction, were not the sufferings of the Jews such as no other people had ever experienced? And after that event, were they not dispersed among all nations? Does not their dispersion still continue? And are they not, at this very moment, a standing proof of his veracity, who predicted their ruin? When I compare the denunciations of Jesus Christ with the fate of the Jews, I am unable to account for their conformity, if I reject his divine inspiration? The history of Josephus, who beheld the ruin of his country, comes in aid of the evangelists. And I feel the same confidence, that Christ foretold, as that the historian related, this terrible event.

After a cool and impartial examination of these facts, can it be strange that I should profess myself a Christian? How can I resist the evidence arising from the completion of prophecy? I find many predictions of prophecy? I find many predictions accomplished in Jesus Christ. And many, which were uttered by him, I find incontestably verified by succeeding events. Will it satisfy my reason, to insinuate that this may be the work of chance? Will it be sufficient to say, that the author of our religion, and certain persons, who assumed the name of prophets, happened to guess right? To those, who have any acquaintance with the doctrine of chances, this insinuation will appear both impertinent and absurd. That there could not have been such a series of fortunate guesses, is a point capable of arithmetical demonstration.

The man who can persuade himself to admit this supposition, must, with a very ill grace, object to the miracles, wonders, and signs, ascribed to Jesus Christ. And of all persons, he ought to be the last to charge others with credulity. As to myself, I cannot believe, that some hundreds of years before the savior appeared, the peculiar circumstances of his life and death were guessed by some imposing diviner. I cannot be reconciled to the supposition, that one by mere accident, guessed that he would enter Jerusalem, riding on an ass, and be there sold for thirty pieces of silver; another, that his enemies would pierce his hands, and his feet, would mock his agonies, and cast lots for his garment; a third, that he would be numbered with transgressors, and be laid in the tomb of a rich man. Such a wonderful resemblance of mere conjecture and fact would exceed any prodigy recorded in the sacred volume.

And the same observation will apply to the predictions of Jesus Christ; whether they relate to his own sufferings, or those of his devoted country. It is impossible that he should have described them with so much precision, unless his mind had been divinely illuminated. The success of modern conjectures is well known and if Jesus Christ be degraded to the rank of those, who have been most expert at guessing, I must say, their talents will admit of no comparison with his. The art, if it was only an art, makes no figure at the present age. I must therefore, conclude, that real predictions were uttered and accomplished. And I must draw from them the inference, that the system is divine, in support of which they have been urged. I have no other alternative, than either to admit this conclusion, or the most extravagant suppositions that ever disgraced the human kind.

Section IV.

Evidence arising from the character and miracles of Christ.

But I have a Fourth reason for my belief and principles as a Christian : and that is, that the author of my religion displayed an example: and performed works, which proclaim, not merely a superior, but a divine character. No human language can do justice to the temper and morals of Jesus Christ. The excellency of the one, and the purity of the other, render him an object worthy of our highest admiration. In ho wonderful a manner did he exemplify his own moral lessons? And how divinely did he support his character, as the friend of mankind? With what exquisite tenderness did he conduct towards the miserable? And what patience did he display, under every species of provocation? How condescending was he to the weak, how humble, how just, how ready to forgive his enemies, how benevolent to all? What a sublime devotion possessed his heart? And in scenes of the deepest distress, how perfect was his resignation? How amiably did he converse? How unblamably did he live? How nobly did he die? And can I reconcile the appearance of such virtue with the mean and interested views of an ambitious impostor? Is it credible, that such pure streams should proceed from a corrupt fountain?

Many, who reject the claims, and deny the miracles of Jesus Christ, admit the moral excellency of his character. A greater inconsistency cannot be conceived! What, is it no offence against the laws of morality to appeal to works never performed; and to pretend to the exercise of powers, which never existed? Are deliberate falsehood, imposition, and hypocrisy, to be crafted from the catalog of crimes? Is impiety no stain? And to die with an obstinate and inflexible adherence to false pretensions, is there nothing immoral in such behavior? I confess, I have very different views of right and wrong. And I feel a strong conviction, that falsehood and deceit, for whatever purpose they may be employed; and to whatever end they may be directed, are to the last degree, criminal and disgraceful.

Yet this accusation must be brought against Jesus Christ, if he did no miracle; and was only a self commissioned reformer. He certainly did profess to work miracles; and he did appeal to them, as divine attestations to his sacred character. If he insisted, that he was sent of God to enlighten and save mankind, he was careful to add, “The works, which I do, they bear witness of me.” I must therefore, deny that he was that excellent person, which some modern unbeliever profess to esteem him. Or, I must admit the reality of those miracles, to which he so often, and with so much solemnity, appealed. There is no other alternative. It cannot be, that he was a splendid pattern of pure and sublime morality; whilst his mission, and supernatural powers, were an artful pretence.

Reduced then, to the necessity either of admitting, together with the moral excellencies, the miracles of Jesus, or of rejecting both, I can, without difficulty, make up my judgment. However unphilosophical it may be thought, I am persuaded that he “did such works as no man could perform, unless God were with him.” Yes, notwithstanding the metaphysics of some and the sneers of others, I do believe that he appealed to facts, when he said, “The blind see; the lame walk; the lepers are cleansed; the deaf hear; and the dead are raised.” God who ordained the laws of nature, can certainly control or suspend them. Nor is there anything absurd in the supposition, that occasions may offer, on which such an application of almighty power may be worthy of God; and reflect honor on his wisdom and benevolence.

It is true, such interruptions of the general course of nature are not visible at the present age. Our eyes have never been gratified with the sight of a miracle. But this is no proof that they eyes of other men in other ages, have imposed upon their understandings. The king of Siam, because he had never seen ice, denied the possibility of its existence. His narrow experience, under a burning sun, was opposed to the testimony of a credible witness. If this prince had been a metaphysician, with what a multiplicity of arguments, would he have encountered and overwhelmed the European, who related the effects of cold upon the waters of his country? If he had been a philosopher, how learnedly would he have reasoned upon the elementary particles of fluids; and from their spherical form, how easily would he have demonstrated the impossibility of congelation? But what is logic, when opposed to fact?

The miracles ascribed to Jesus Christ, and the apostles, rest upon the same foundation with other articles, which we find in the narratives of his life. They have not come down to us through the channel of tradition; but by means of a formal record, made by persons, who declare themselves witnesses of the scenes which they describe. Nor are they introduced into these records merely by way of ornament; or to animate a dull narration: they are an essential part of the work. In the same page, we find the miracles and moral lessons of Jesus Christ. In the same artless manner, they are both related. For which reason, I feel myself unable to draw the line, where truth ends; and fiction begins. All my information concerning Jesus Christ, is derived from the same source. Where testimony is so explicit and circumstantial, I must therefore, admit the whole; or reject the whole. I mention this, because some have professed to believe the history of our Lord’s discourses, whilst they denied that of his miracles. But these articles are so connected, that there can be no discrimination. If an evangelist deserves credit, when he solemnly declares the things which he heard; why not, when he as solemnly declares the facts which he saw? Why should I ascribe more veracity to his ears, than to his eyes?

That the miracles of Jesus sand as fairly recorded as his moral instruction, is not however, my only reason for believing them. Certain events which took place at the memorable period, when these miracles are said to have been exhibited, are a demonstration of their reality. I find, that multitudes, who had the best means of informing their minds on this subject; and who could have detected the imposition, if any had been practiced, were fully persuaded; that supernatural powers had been exercised by Christ and his apostles. So strong was their conviction, that it overcame early habits; and induced them to embrace the religious system, which appealed to this evidence. Nor was this all : it overcame the apprehensions of contempt, of worldly losses, of every species of injury, and of a cruel and infamous death. Upon the principle of miracles, it is easy to account for this magnanimity. But, if the Christian record of miracles be a mere fable, how came the conviction of their reality to take possession of so many fair and honest minds; and to produce such astonishing effects? Why did they believe, who were placed beyond the reach of imposition; and who could have no motive assent to the powers, claimed by the founder, and first preachers of religion, but the certainty that they existed? I am free to confess, that the faith of multitudes, situated as they were, has great influence in confirming my own.

But to pursue the argument : I believe the miracles recorded in the New Testament, because they were not called in question by early infidels. The Jews were compelled to won, that the powers, occasionally exercised by Jesus Christ, were supernatural. “This man doeth many miracles,” was the confession even of the priests and Pharisees. And the modern Jews do not pretend to deny, that the founder of the Christian sect performed many things, which no man could do, unless he were assisted by invisible agents. But, to avoid the consequences of such a concession, they both ascribe his miracles to an infernal cause. Succeeding unbelievers were likewise as well convinced of this part of our Lord’s history. Julian acknowledges, that Christ opened the eyes of the blind; restored limbs to the lame; and recovered demoniacs of their malady. But he intimates, that these are no very extraordinary feats. And Celsus, another violent enemy to Christianity, not presuming to deny the mighty works of Jesus endeavors to depreciate them, by pretending that he learned magic in Egypt. Besides, it is well known, that because the miracles of Christ could not be denied, attempts were made to eclipse their glory. Appollonius Tyanaeus was brought into public view by two unbelievers, as a person whose powers exceeded those of Jesus. The concessions of Julian and Celsus, and this attempt to set up a rival to the savior, may be easily accounted for, if we admit that signs were displayed; and miracles performed by him. But if his supernatural powers were an artful pretence, why did not these adversaries publish the imposition? They did not want sagacity to detect any unfair dealing. And such a discovery would have given the triumph to their cause. That early unbelievers, and some of them persons of the most extensive information; that a Julian and a Celsus did not deny the miracles of Chris, is with me a very strong argument in favor of those miracles. And combined with other evidence, this circumstance is sufficient for my conviction.

Finally, the lying wonders, and pretended miracles of impostors, are a proof that supernatural powers have been employed for religious purposes. This appears to be the just conclusion from these facts. Impostors would not have had recourse to such arts, if they had not known the success of real miracles. Would counterfeits have found their way into circulation, if there never had been genuine coin? Did not the latter unquestionably suggest the former? We may be assured, that pretended miracles would never have enriched the legend of a faint, if real miracles had never attracted the attention of mankind. Supernatural powers have been feigned tin later times, because, in the primitive ages, such powers really existed. And lying wonders, at the tomb of the Abbe DeParis, cam in aid of his doubtful reputastion, because the tomb of Christ was the scene of wonders and sign, which gave immortal spendor to his character; and ensured the final triumphs of his cause.

I have now assigned the various reasons, on which I ground my assent to the miracles, which stand recorded in the Christian volume. I believe them, because they rest on the same historic evidence, with the moral instruction, and common facts contained in that book. I believe them, because co-temporary and subsequent events were such as might have been expected from the operation of miracles on the human mind. I believe them, because the early opposers of Christianity did not call them in question. And I believe them, because their reality appears to me, to be a fair deduction from many unsuccessful attempts to imitate, and to rival them. Thus convinced of the supernatural powers of Jesus Christ and the apostles, I am persuaded that they spake by authority; and consequently, that the religious system, church derives its name from the former, is not only superior to all others, but that it is DIVINE.

With such force, do these arguments operate on my understanding, that I feel an increasing confidence in my principles as a Christian. The more I examine the evidences of my religion, the more am I convinced, that it will not be overthrown by the weapons usually employed against it. The foundation which supports it, is not to be weakened by the shafts of wit; or blown down by the breath of ridicule. I am sensible, that there is no subject which may not be placed in a ludicrous point of light; as there is no character which may not be vilified. Religion, patriotism, chastity, and almost every moral and social virtue, have, in their turn, been so exposed as to invite contempt. Soame Jeyns has discharged all wit upon the rights of man, and the leading principles of a free government. If ridicule were the test of truth, his book would be unanswerable. But though it abounds with wit, it contains one argument. And for this reason, the cause of civil freedom has suffered no injury from such an assailant. Though republican principles be the butt of his ridicule, yet they command the highest respect, wherever they are seriously examined. And the same observation may be applied to the subject of religion. To overthrow the faith of one, who has studied its evidence, arguments must be employed, and not the false colorings of wit. Facts must be fairly and clearly disproved. Otherwise, the Christian will retain his reverence for religion; and thoughts ashamed of the disingenuity of an opposer, he will not be ashamed of the Gospel.

But from the wit exerted upon Christianity, I proceed to more sober objections. And I must say, that however plausible they may seem at first, they do not, by any means, invalidate its evidence. Many of them are impertinent; because they are leveled, not against the Christian religion, but against its corruptions. And many more are sufficiently answered by an appeal to the constitution of nature; and the degree of evidence upon which we act in general concerns. Some objections, if admitted, would overthrow the credit of all history. And others, when pursued to their just consequences, would not only subvert the religion of Christ, but would bury natural religion in its ruins.

In vain then, are objections of this kind urged against Christianity. In vain am I reminded that the Gospel was first preached to the multitude; and not to the learned wise. I know that there is as much fairness of mind in the former, as in the latter; and, in regard to matters of fact, that they are as competent judges. In vain am I called to reflect, that false pretences to inspiration, and lying wonders, have, in all ages, been employed for political purposes. The fact I do not dispute; but I deny the conclusion. Falsehoods are daily uttered; but does it follow, that the truth is never spoken? Because many counterfeits are in circulation, is there no unadulterated coin? As I have before had occasion to observe, the various arts of religious imposition take their origin from real miracles, and a real inspiration. In vain am I told, that the Christian system is not universal; and of consequence, cannot proceed from the common parent of mankind. I know that reason is imparted in various degrees; that the means of improvement, civil liberty, and all the outward blessings of life, are bestowed in different measures on different objects : and yet, I am persuaded, that they all come from God. In vain is my attention called to the angry disputes of Christians, respecting the doctrines of the Gospel I am convinced that such is the weakness of the human mind, disputes may arise on any subject. I hear men dispute on the principles of government, the rights of citizens, and the nature and extent of civil liberty : and yet, I doubt not, that these rights, and this liberty, have a real foundation; and that the end of government is their security. Why then, should the disputes of Christians discredit the Gospel? In vain is my faith insulted with the mortifying insinuation, that professors do not exemplify the virtues of their religion; that their principles and practice are often at variance. I am sensible that Christians are rational agents; and that the influence of their religion is not compulsory, but moral. Why then, should I be more surprised that the laws of the Gospel should be occasionally disregarded, than that the dictates of conscience, or the laws written on the heart, should not always maintain their authority? In vain will any urge, to the prejudice of Christianity, the ambition of a priesthood; and the various steps, by which the ministers of religion ascended from the condition of instructors, to that of oppressors. The Gospel I am certain, gives no countenance to such abuses. So far from it spiritual pride, and spiritual tyranny, are objects of its execration. I might go on to enumerate other popular objections against the system; but he who has formed his ideas of Christianity from the writings of the apostles and evangelists, will be certain that its credit is not injured by them.

As there is not any subject, which may not be turned into ridicule, neither is there any historical fact against which many plausible objections may not be raised. Considering his power, influence and popularity, the destruction of Cesar, by the Roman senators, may be opposed with great ingenuity; and many arguments may be brought to fix a suspicion on this part of ancient history. The execution of Charles the first, and the triumphs of Cromwell, are likewise articles which a logician might assail with many objections. And if a skeptic were so disposed, now easily might he refute (as the term is sometimes understood) the American history of independence4? He might contrast the naval and military strength, the riches, and the population of Britain, with the poverty and weakness of the colonies: —he might also expatiate on the different principles, habits, interfering interests, and jealousies of the colonists; — and subjoining the fears of some, and the strong attachment of others to their political parent, he might, from the whole, show the incredibility of our revolution. Still, the glorious fact is a refutation of such reasonings. And I must observe, that in regard to historical relations, the testimony of one credible witness will outweigh millions of such objections, as a fruitful imagination may easily invent.

This conviction never fails to accompany me, when I repair to the sacred oracles. In the New Testament, I find a detail of instructions given, of wonders performed, and of futurities revealed. I am also entertained with a particular account of the sufferings, death resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Other astonishing events likewise, as circumstantially related. And the history containing these things appears to be as fairly written; and to carry with it as substantial proofs of its authenticity, as any history which has gained credit in the world. Do any ask, why I believe the antiquity of the Christian records? I answer, for the same reason that I believe the antiquity of Virgil’s Poems, Cesar’s Commentaries, or Sallust’s Narrations: and that is, the concurring testimony of all intervening ages. Do any ask, why I believe, that the several books were written by the persons whose names they bear? I answer, for the same reason that I believe the Georgics to be the production of Virgil; — Jerusalem Delivered, that of Tasso; — Paradise Lost, that of Milton; —an Essay, upon the subject of Miracles to be the work of Hume; —and a Refutation of that Essay the performance of Campbell. Do any inquire, whether the sacred pages have not been greatly corrupted? I answer, they have not been greatly corrupted; as appears by a collation of the earliest manuscripts, and an appeal to the earliest versions, and ancient fathers. So many corroborating circumstances plead in favor of the Gospel, that I must either distrust all records; or continue to admit the authenticity of those, which display the duty and hopes of a Christian.

To conclude: the religion of Jesus Christ does not decline a fair examination. It consents to meet opposition; but in the character of its opponent, it requires certain qualifications, which have not always appeared in the contest. It requires a large acquaintance with the system itself, an acquaintance formed, not through the medium of human creeds, but by a direct application to the evangelic records. And it requires an extensive knowledge of the peculiar language, in which those records were originally composed, of the various readings grounded on different manuscripts of Heathen and Jewish testimonies, of the customs and moral state of those countries where Christianity was first published, of the concessions and objections of the earliest unbelievers, and of the general history of the church. Thus furnished, several have attacked this religion; but the contest has generally terminated in their conviction. I know many instances, where men have opened the history of Christ with the disrespect of unbelievers; and closed it with the reverence of Christians.

The prevailing sentiments of Americans will be naturally on the side of that religion, which has been the subject of this work. Its influence in the first settlement of the country, will not be soon effaced from their minds. Their political principles will inspire a reverence for a system, which admits of no respect of persons; but inspire a reverence for a system, which admits of no respect of persons; but enjoins the same duties on all; and opens to all, the same prospects of glory, honor, and immortality. Its benevolent tendency, conspiring with its evidence, must ensure to it a fair examination. And those, who thus examine, even if they remain unconvinced will consent, that others should cultivate its temper; and follow its rules. They will not be displeased at seeing the virtue of their neighbors, directed and invigorated by Christian principles. And though they may not see fit to adopt their language yet they will impute no uncommon weakness, credulity, or fanaticism to those, who say with apostle, “LORD TO WHOM SHALL WE GO? THOU HAST THE WORDS OF ETERNAL LIFE.”

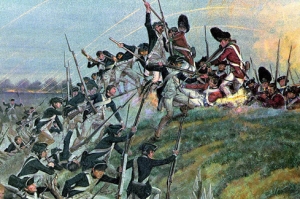

The Siege of Yorktown is recognized as the final major military action in the War for Independence. This

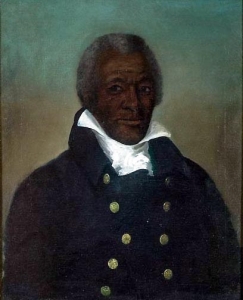

The Siege of Yorktown is recognized as the final major military action in the War for Independence. This  For example, a black man,

For example, a black man,  Cornwallis was heavily outnumbered (there were

Cornwallis was heavily outnumbered (there were

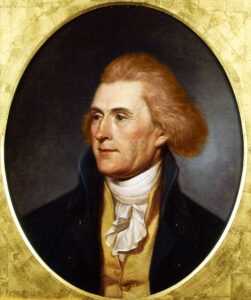

On July 4, 1776 a group of Americans approved a document declaring the United States of America free from English rule. This document was the Declaration of Independence,

On July 4, 1776 a group of Americans approved a document declaring the United States of America free from English rule. This document was the Declaration of Independence, When forced, therefore, to resort to arms for redress, an appeal to the tribunal of the world was deemed proper for our justification. This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind.

When forced, therefore, to resort to arms for redress, an appeal to the tribunal of the world was deemed proper for our justification. This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind. [The] Declaration unleashed not merely a revolution against the British but a revolution in human affairs. Its authors were highly conscious of its worldwide implications. And

[The] Declaration unleashed not merely a revolution against the British but a revolution in human affairs. Its authors were highly conscious of its worldwide implications. And

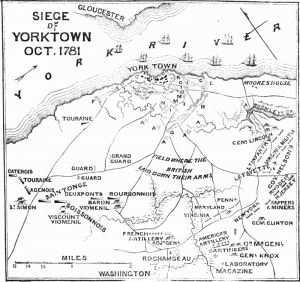

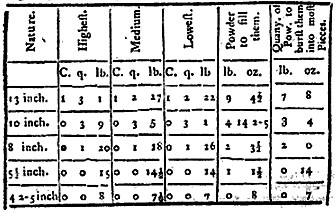

Starting on September 28th and ending with British capitulation on October 19th, the Battle of Yorktown was the last major military engagement of the war. Commanders for the Allied land forces included Generals Henry Knox, Marquis de Lafayette, and Rochambeau under George Washington, while the Allied naval forces consisted of the French fleet led by Comte de Grasse. Most of the engagement at Yorktown centered on the artillery of the two sides, while the main infantry movements were the capture of Redoubts 9 and 10.

Starting on September 28th and ending with British capitulation on October 19th, the Battle of Yorktown was the last major military engagement of the war. Commanders for the Allied land forces included Generals Henry Knox, Marquis de Lafayette, and Rochambeau under George Washington, while the Allied naval forces consisted of the French fleet led by Comte de Grasse. Most of the engagement at Yorktown centered on the artillery of the two sides, while the main infantry movements were the capture of Redoubts 9 and 10.

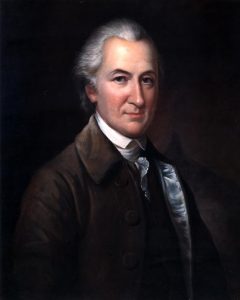

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city

March 17 is annually celebrated in Boston as “Evacuation Day,” commemorating the departure of the British from the city Hancock and Adams were staying in the home of Lexington Pastor Jonas Clark.

Hancock and Adams were staying in the home of Lexington Pastor Jonas Clark.

The rights of religious conscience were then enshrined at the federal level in the

The rights of religious conscience were then enshrined at the federal level in the  Also celebrated today is the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. This pastor practiced many First Amendment rights, including not only that of free-exercise of religion but also assembly, petition, and speech. Dr. King’s use of non-violent protests during the Civil Rights movement caused him to receive the

Also celebrated today is the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. This pastor practiced many First Amendment rights, including not only that of free-exercise of religion but also assembly, petition, and speech. Dr. King’s use of non-violent protests during the Civil Rights movement caused him to receive the