One of the first rights to be protected in early America was the right of conscience – the right to believe differently on issues of religious faith. As John Quincy Adams explained, this right was a product of Christianity:

Jesus Christ. . . . came to teach and not to compel. His law was a Law of Liberty. He left the human mind and human action free. 1

Early American legal writer Stephen Cowell (1800-1872) agreed:

Nonconformity, dissent, free inquiry, individual conviction, mental independence, are forever consecrated by the religion of the New Testament. 2

President Franklin D. Roosevelt likewise declared:

We want to do it the voluntary way – and most human beings in all the world want to do it the voluntary way. We do not want to have the way imposed. . . . That would not follow in the footsteps of Christ. 3

The Scriptures teach that there will be differences of conscience (cf. 1 Corinthians 8) and that if an individual “wounds a weak conscience of another, you have sinned against Christ” (v. 12). We are therefore instructed to respect the differing rights of conscience (v. 13). (See also I Corinthians 10:27-29.) Extending toleration for the rights of conscience is urged throughout the New Testament. (See also Romans 14:3, 15:7, Ephesians 4:2, Colossians 3:13, etc.)

Leaders who knew the Scriptures therefore protected those rights. For example, in 1640, the Rev. Roger Williams established Providence, penning its governing document declaring:

We agree, as formerly hath been the liberties of the town, so still, to hold forth liberty of conscience. 4

Similar protections also appear in the 1649 Maryland “Toleration Act,” 5 the 1663 Charter for Rhode Island, 6 the 1664 Charter for Jersey, 7 the 1665 Charter for Carolina, 8 the 1669 Constitutions of Carolina, 9 the 1676 Charter for West Jersey, 10 the 1701 Charter for Delaware, 11 and the 1682 Frame of Government for Pennsylvania. 12 John Quincy Adams affirmed that: “The transcendent and overruling principle of the first settlers of New England was conscience.” 13

Then when America separated from Great Britain in 1776 and the states created their very first state constitutions, they openly acknowledged Christianity and jointly secured religious toleration, non-coercion, and the rights of conscience. For example, the 1776 constitution of Virginia declared:

That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other. 14

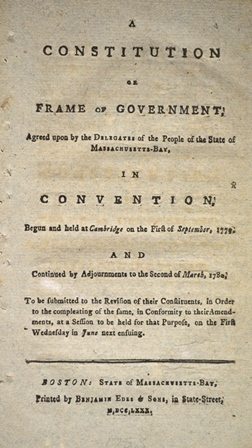

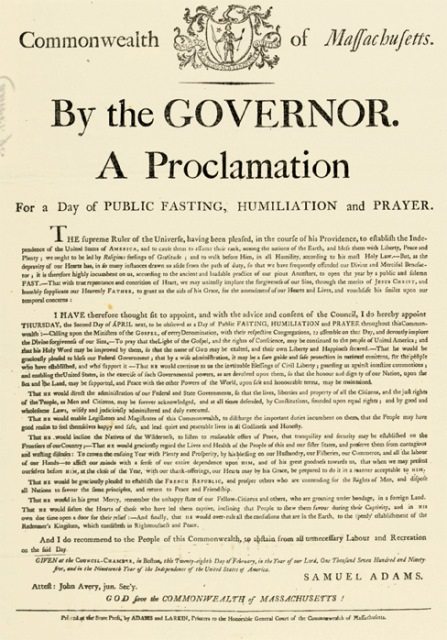

Similar clauses appeared in the constitutions of New Jersey (1776), 15 North Carolina (1776), 16 Pennsylvania (1776), 17 New York (1777), 18 Vermont (1777), 19 South Carolina (1778), 20 Massachusetts (1780), 21 New Hampshire (1784), 22 etc. Today, the safeguard for the rights of conscience pioneered by Christian leaders is a regular feature of state constitutions. 23

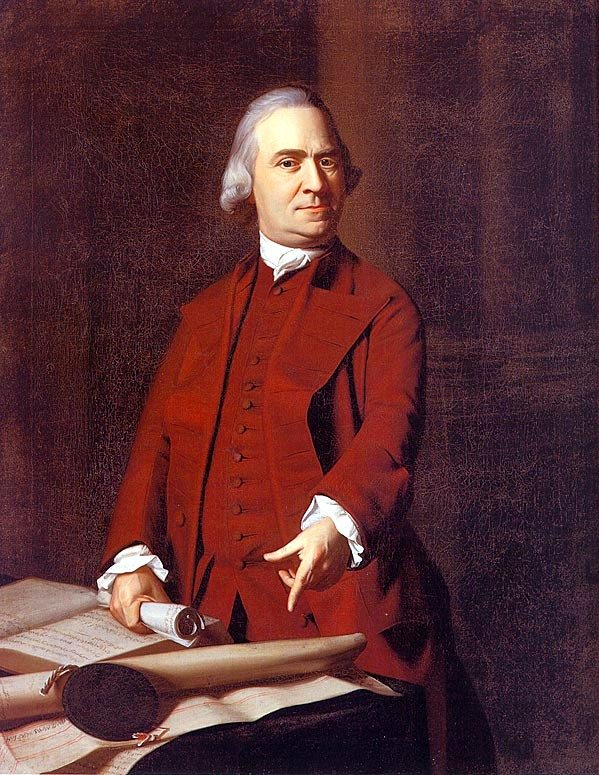

The Founding Fathers were outspoken about the importance of this God-given inalienable right. For example, signer of the Constitution William Livingston declared:

Consciences of men are not the objects of human legislation. . . . [H]ow beautiful appears our [expansive] constitution in disclaiming all jurisdiction over the souls of men, and securing (by a never-to-be-repealed section) the voluntary, unchecked, moral suasion of every individual. 24

And John Jay, the original Chief Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court, similarly rejoiced that:

Security under our constitution is given to the rights of conscience and private judgment. They are by nature subject to no control but that of Deity, and in that free situation they are now left. 25

President Thomas Jefferson likewise declared that the First Amendment was an “expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience.” 26

But President Obama disagrees with what for four centuries in American history has formerly been an inalienable right. He has specifically singled out and attacked the rights of religious and moral conscience, seeking to coerce dissenters into accepting his own beliefs. While Biblical teachings result in protection for differences of opinion on religious issues, secularists demand conformity of belief and practice to their own secular standards; they are especially intolerant of any differences that stem from Biblical faith.

While the President has targeted the Catholic Church for its religious beliefs, his attacks on religious conscience were ongoing, beginning shortly after he first took office when he first announced his plans to repeal religious conscience protection for medical workers. (We have posted on our website a piece showing the extreme and consistent hostility of this President against Biblical faith and values. As proven by his own actions and words, he is the most anti-Biblical president in American history.)

1 John Quincy Adams, A Discourse on Education Delivered at Braintree, Thursday, October 24th, 1839 (Boston: Perkins & Marvin, 1840), 17-18.

2 Stephen Colwell, Politics for American Christians: A World upon our Example as a Nation, our Labour, our Trade, Elections, Education, and Congressional Legislation (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co. 1852), 82.

3 “Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Christmas Greeting to the Nation,” American Presidency Project, December 24, 1940, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/209414.

4 “Plantation Agreement at Providence,” The Avalon Project, August 27 – September 6, 1640, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ri01.asp.

5 William MacDonald, Select Charters and Other Documents Illustrative of American History 1606-1775 (New York: MacMillan Company, 1899), 104-106.

6 “Plantation Agreement at Providence August 27 – September 6, 1640,” The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters and Other Organic Laws, ed. Francis Newton Thorpe (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), VI:3211; “Charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,” The Avalon Project, July 15, 1663, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ri01.asp.

7 “The Concession and Agreement of the Lords Proprietors of the Province of New Caesarea, or New Jersey,” The Avalon Project, 1664, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nj05.asp.

8 “Charter of Carolina,” The Avalon Project, June 30, 1665, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc03.asp.

9 “Fundamental Constitution of Carolina,” The Avalon Project, March 1, 1669, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc05.asp.

10 “The Charter or Fundamental Laws of West New Jersey,” The Avalon Project, 1676, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nj05.asp.

11 “Charter of Delaware,“ The Avalon Project, 1701, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/de01.asp.

12 “ Frame of Government of Pennsylvania,“ The Avalon Project, May 5, 1682, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/pa04.asp.

13 John Quincy Adams, A Discourse on Education Delivered at Braintree, Thursday, October 24th, 1839 (Boston: Perkins & Marvin, 1840), 28.

14 “Constitution of Virginia: Bill of Rights,” The American’s Guide: Comprising the Declaration of Independence; the Articles of Confederation; the Constitution of the United States, and the Constitutions of the Several States Composing the Union (Philadelphia: Hogan & Thompson, 1845), 180.

15 “Constitution of New Jersey,” The Avalon Project, 1776, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/nj15.asp.

16 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), 132.

17 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), 77.

18 “The Constitution of New York,” The Avalon Project, April 20, 1777, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/ny01.asp 1777.

19 The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws, 3d. Francis Newton Thorpe (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), VI:3740.

20 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America, (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), 152-154.

21 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), 6.

22 Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman & Bowen, 1785), 3-4.

23 “State Policies in Brief: Refusing to Provide Health Services,” Guttmacher Institute, March 1, 2012, https://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_RPHS.pdf.

24 William Livingston, The Papers of William Livingston, eds. Carl E. Prince, et al (Trenton: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1980), 2:235-237, writing as “Cato,” February 18, 1778.

25 Benjamin F. Morris, Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States, Developed in the Official and Historical Annals of the Republic (Philadelphia: George W. Childs, 1864), 152.

26 Thomas Jefferson to Messrs. Nehemiah Dodge, Ephraim Robbins, and Stephen S. Nelson, A Committee of the Danbury Baptist Association, in the State of Connecticut, January 1, 1802 Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Albert Ellery Bergh (Washington D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), XVI:281-282.

* This article concerns a historical issue and may not have updated information.

is celebrated in America each year on January 16 — the date of the 1786 passage of Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom. That measure ended the state-established church in Virginia and for the first time placed all denominations on the same legal footing. That act fully protected the right of religious conscience — one of the first rights protected in America. As John Quincy Adams affirmed, “The transcendent and overruling principle of the first settlers of New England was conscience.”

is celebrated in America each year on January 16 — the date of the 1786 passage of Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom. That measure ended the state-established church in Virginia and for the first time placed all denominations on the same legal footing. That act fully protected the right of religious conscience — one of the first rights protected in America. As John Quincy Adams affirmed, “The transcendent and overruling principle of the first settlers of New England was conscience.”

The rights of religious conscience were then enshrined at the federal level in the First Amendment of the Constitution. As Thomas Jefferson affirmed multiple times:

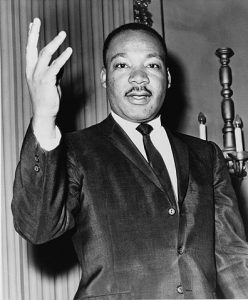

The rights of religious conscience were then enshrined at the federal level in the First Amendment of the Constitution. As Thomas Jefferson affirmed multiple times: Also celebrated today is the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. This pastor practiced many First Amendment rights, including not only that of free-exercise of religion but also assembly, petition, and speech. Dr. King’s use of non-violent protests during the Civil Rights movement caused him to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Also celebrated today is the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. This pastor practiced many First Amendment rights, including not only that of free-exercise of religion but also assembly, petition, and speech. Dr. King’s use of non-violent protests during the Civil Rights movement caused him to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

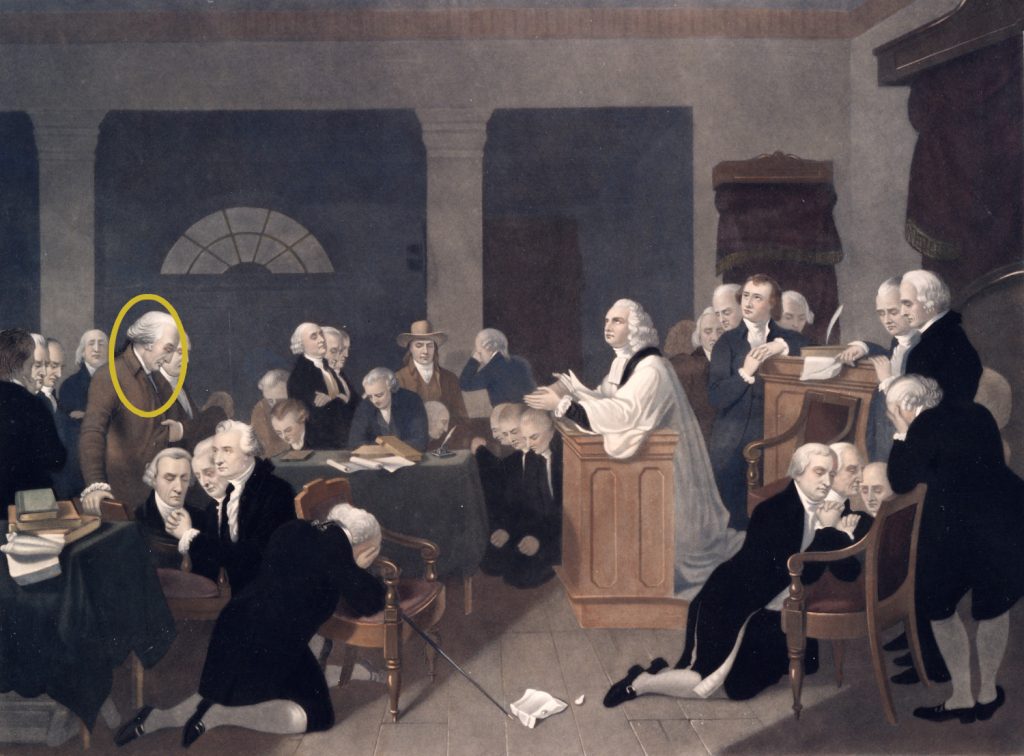

I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth- that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that “except the Lord build the House they labor in vain that build it.” I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without His concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel.

I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth- that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that “except the Lord build the House they labor in vain that build it.” I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without His concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel.

In the wake of the heart-rending massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School,

In the wake of the heart-rending massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School,  The Founders understood that the inside was the most important focus, not the outside. This is why Thomas Jefferson believed the teachings of Jesus were so effective, explaining:

The Founders understood that the inside was the most important focus, not the outside. This is why Thomas Jefferson believed the teachings of Jesus were so effective, explaining:

The right . . . of bearing arms . . . is declared to be inherent in the people. Fisher Ames, A Framer of the Second Amendment in the First Congress

The right . . . of bearing arms . . . is declared to be inherent in the people. Fisher Ames, A Framer of the Second Amendment in the First Congress

[I] beg I may not be understood to infer that our general Convention was Divinely inspired when it formed the new federal Constitution . . . [yet] I can hardly conceive a transaction of such momentous importance to the welfare of millions now existing (and to exist in the posterity of a great nation) should be suffered to pass without being in some degree influenced, guided, and governed by that omnipotent, omnipresent, and beneficent Ruler in Whom all inferior spirits “live and move and have their being” [Acts 17:28].

[I] beg I may not be understood to infer that our general Convention was Divinely inspired when it formed the new federal Constitution . . . [yet] I can hardly conceive a transaction of such momentous importance to the welfare of millions now existing (and to exist in the posterity of a great nation) should be suffered to pass without being in some degree influenced, guided, and governed by that omnipotent, omnipresent, and beneficent Ruler in Whom all inferior spirits “live and move and have their being” [Acts 17:28].  As to my sentiments with respect to the merits of the new Constitution, I will disclose them without reserve. . . . It appears to me then little short of a miracle that the delegates from so many different states . . . should unite in forming a system of national government.

As to my sentiments with respect to the merits of the new Constitution, I will disclose them without reserve. . . . It appears to me then little short of a miracle that the delegates from so many different states . . . should unite in forming a system of national government.

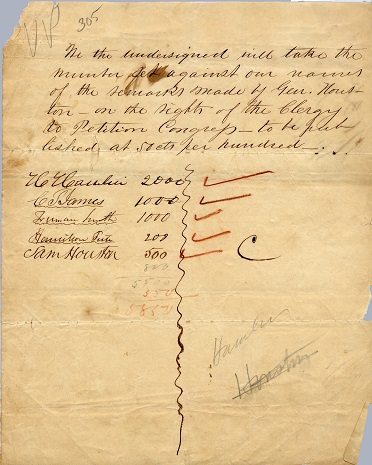

…I certainly can see no more impropriety in ministers of the Gospel, in their vocation, memorializing [petitioning] Congress than politicians or other individuals. . . . Because they are ministers of the Gospel, they are not disfranchised of political rights and privileges and . . . they have a right to spread their opinions on the records of the nation. . . . The great Redeemer of the World enjoined duties upon mankind; and there is [also] the moral constitution from which we have derived all the excellent principles of our political Constitution – the great principles upon which our government, morally, socially, and religiously is founded. Then, sir, I do not think there is anything very derogatory to our institutions in the ministers of the Gospel expressing their opinions. They have a right to do it. No man can be a minister without first being a man. He has political rights; he has also the rights of a missionary of the Savior, and he is not disfranchised by his vocation. . . . He has a right to interpose his voice as one of its citizens against the adoption of any measure which he believes will injure the nation. . . . [Ministers] have the right to think it is morally wrong, politically wrong, civilly wrong, and socially wrong. . . . and if they denounce a measure in advance, it is what they have a right to do.

…I certainly can see no more impropriety in ministers of the Gospel, in their vocation, memorializing [petitioning] Congress than politicians or other individuals. . . . Because they are ministers of the Gospel, they are not disfranchised of political rights and privileges and . . . they have a right to spread their opinions on the records of the nation. . . . The great Redeemer of the World enjoined duties upon mankind; and there is [also] the moral constitution from which we have derived all the excellent principles of our political Constitution – the great principles upon which our government, morally, socially, and religiously is founded. Then, sir, I do not think there is anything very derogatory to our institutions in the ministers of the Gospel expressing their opinions. They have a right to do it. No man can be a minister without first being a man. He has political rights; he has also the rights of a missionary of the Savior, and he is not disfranchised by his vocation. . . . He has a right to interpose his voice as one of its citizens against the adoption of any measure which he believes will injure the nation. . . . [Ministers] have the right to think it is morally wrong, politically wrong, civilly wrong, and socially wrong. . . . and if they denounce a measure in advance, it is what they have a right to do.

A Founding Father who exerted great influence in our constitutional government was Alexander Hamilton. As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and one of its thirty-nine signers, he played what would be considered a minor role in the debates of the Convention itself. However he (along with John Jay and James Madison) became one of the three men most responsible for the adoption and ratification of the Constitution through the writing and publication of a series of articles which became known as The Federalist Papers.

A Founding Father who exerted great influence in our constitutional government was Alexander Hamilton. As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and one of its thirty-nine signers, he played what would be considered a minor role in the debates of the Convention itself. However he (along with John Jay and James Madison) became one of the three men most responsible for the adoption and ratification of the Constitution through the writing and publication of a series of articles which became known as The Federalist Papers. (By the way, during that election cycle in 1800, a number of ministers preached and published pulpit sermons against Jefferson, including Hamilton’s good friend, the Rev. John Mitchell Mason.)

(By the way, during that election cycle in 1800, a number of ministers preached and published pulpit sermons against Jefferson, including Hamilton’s good friend, the Rev. John Mitchell Mason.)