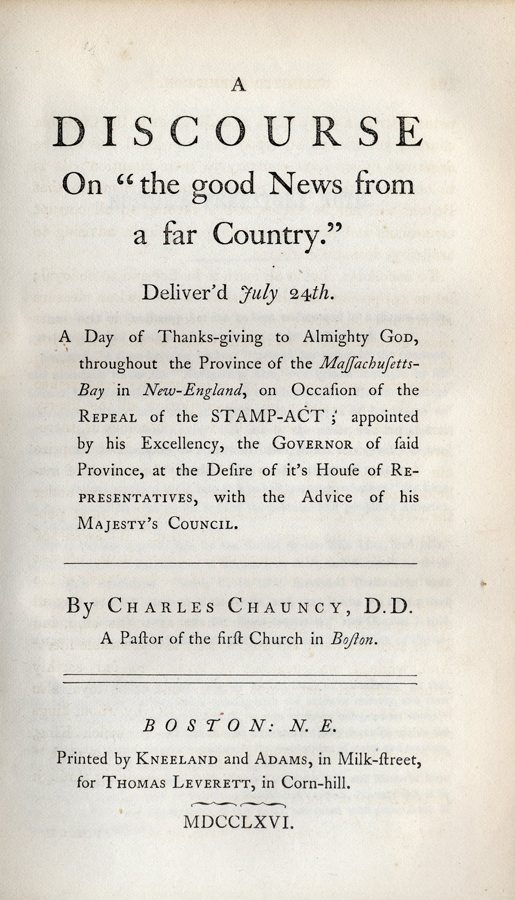

Charles Chauncy (1705-1787) was a minister from Boston. He attended Harvard, graduating in 1721. Chauncy preached at the First Church in Boston for sixty years (1727-1787).

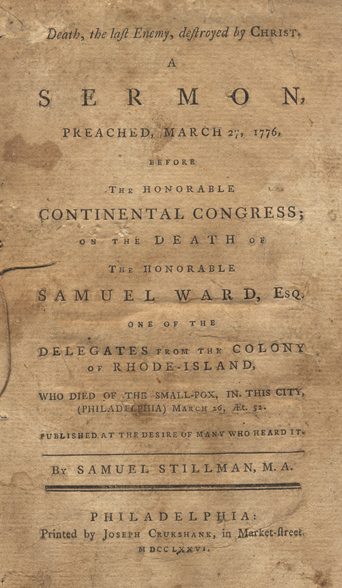

Below is Chauncy’s 1766 sermon on the day of Thanksgiving proclaimed in Massachusetts on occasion of the repeal of the Stamp Act.

A

DISCOURSE

On “the good News from a far Country.”

Deliver’d July 24th.

A Day of Thanks-giving to Almighty God, throughout the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in New-England, on Occasion of the Repeal of the STAMP-ACT; appointed by his Excellency, the Governor of said Province, at the Desire of it’s House of Representatives, with the Advice of his Majesty’s Council.

By Charles Chauncy, D.D.

A Pastor of the first Church in Boston.

EDITOR’S PREFATORY NOTE.The origin of the Stamp Act can be best understood by a glance at the previous political relations of the colonies to the mother land.

England, “a shop-keeping nation,” 1 gained her riches by the commercial monopoly under the “Navigation Acts,”—a system invented by Sir George Downing, the one whose name stands second on Harvard College catalogue. These acts were modified as the changes of commerce required, and the “Stamp Act,” but one of the series, was intended to retain the old monopoly of American trade, which was greatly endangered by the conquest of Canada. This was its origin and motive.

The dispute resolved itself into this naked question, whether “the king in Parliament 2 had full power to bind the colonies and people of America in all cases whatsoever,” or in none.

The colonists argued that, by the feudal system, the king, lord paramount of lands in America, as in England, as such, had disposed of them on certain conditions. James I., in 1621, informed Parliament that “America was not annexed to the realm, and that it was not fitting that Parliament should make laws for those countries;” and Charles I. told them “that the colonies were without the realm and jurisdiction of Parliament.” The colonists showed that the American charters were compacts between the king and his subjects who “transported themselves out of this kingdom of England into America,” by which they owed allegiance to him personally as sovereign, but were to make their own laws and taxes: for instance, a revenue was raised in Virginia by a law “enacted by the King’s most excellent Majesty, by and with the consent of the General Assembly of the Colony of Virginia.” They denied the authority of the legislature of Great Britain over them, but acknowledged his Majesty as a part of the several colonial legislatures.

But the colonies, while jealous of their internal self-control, had permitted the British Parliament to “regulate” their foreign trade, and, upon precedent, the latter now claimed authority to bind the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” Relying upon the royal compact in their chargers, the spirit of the British constitution, and “their rights as Englishmen,” the Americans denied the jurisdiction of their “brethren” in England.

“Nil Desperandum, Christo Duce,” was the motto on the flag of New England in 1745, when her Puritan sons conquered Louisburg, the stronghold of Papal France in the New World, and thus gave peace to Europe. This enterprise, in its spirit, was little less a crusade than was that to redeem Palestine from the thraldom of the Mussulman, and the sepulcher of Jesus from the infidels. One of the chaplains carried upon his shoulder a hatchet to destroy the images in the Romish churches. “O,” exclaimed a good old deacon, to Pepperell, “O that I could be with you and dear Parson Moody in that church, to destroy the images there set up, and hear the true gospel of our Lord and Saviour there preached! My wife, who is ill and confined to her bed, yet is so spirited in the affair . . . . . that she is very willing all her sons should wait on you, though it is outwardly greatly to our damage. One of them has already enlisted, and I know not but there will be more.” 3 “Christo Duce!” The extinction of French dominion was quickly completed by the conquest of Canada in 1759-60, and at the same moment ceased the colonial need of the red-cross flag of St. George, whose nationality had been their protection against the aggressions of the French. The French being driven from Canada, New England could stand alone. This was the point “in the course of human events” when the sovereignty of England over the colonies was ended, though their formal “Declaration of American Independence,” and of the dissolution of “the political bands” with the mother country, was not issued till several years later. The conquest of Canada was the emancipation of the colonies, as the opponents of the war predicted. British parliaments, though backed by British guns, and all the canons of the English church, were powerless against “the laws of nature and nature’s God;” and the Stamp Act was merely a touchstone for certain “self-evident truths”—not mere “sounding and glittering generalities”—enunciated on the Fourth of July, 1776. This attempt at despotism resulted in the alienation of the colonists from their brethren in England, the Union, the War of the Revolution, and the birth of a Nation. By it England lost her American dominion, won defeat and dishonor, and added to the national debt one hundred and four million pounds sterling, on which she is now paying interest,–the work of George III. And his servile ministers, his “domestics,” as they were called. But America saved not only her own liberty, but the liberty of England; the policy of George III. And his government, which the colonies defeated, if attempted at this day, would not only sever every colony, but overthrow the throne itself. In January, 1766, Mr. Pitt himself declared the American controversy to be “a great common cause,” and that “America, if she fell, would fall like a strong man. She would embrace the pillars of the state, and pull down the constitution along with her.” Hear Lord Camden, also: “I will say, not only as a statesman, politician, and philosopher, but as a common lawyer, you have no right to tax America. The natural rights of man and the immutable laws of nature are all with that people.” And General Burgoyne declared in Parliament, in 1781, that he “was now convinced the principle of the American war was wrong,. . . only one part of a system leveled against the constitution and the general rights of mankind.” It was equally for the sake of England as of America that Mr. Pitt and the high-minded men of that day “rejoiced” in our resistance to tyranny. “Passive obedience” then became an obsolete gospel.

One of the most efficient causes of the Revolution in the minds and hearts of the people—an accomplished fact before the war commenced—was the controversy begun in 1763 by the Rev. Dr. Mayhew in his attack on the conduct of the “society for Propagating the Gospel in Foreign Parts.” The most insidious scheme for reducing the colonies to slavery was that of this society, which was known to be only an association for propagating “lords spiritual” in America, 4 who should inculcate, in the name of religion, the Church of England principles of “submission and obedience, clear, absolute, and without exception.” Dr. Mayhew exposed this pious fraud. The Bishop of Landaff, in his sermon of 1766, before this society, ingenuously declared, that when Episcopacy should be established in America, “then this society will be brought to the happy issue intended”!

This excited general alarm. The hierarchy could be established only by Parliament; and if, they reasoned, Parliament can authorize bishops, tithes, ceremonies, and tests in America, they can tax us; and what can they not do? The question was, really, Does the British Parliament, three thousand miles off, in which we have neither voice nor vote, own us, three million people, souls and bodies? The people considered the matter, and gradually got ready to fight about it, seeing no more “divine right” of parliaments than of kings, which last had been “unriddled” [solved] by Dr. Mayhew in 1750.

The plot was to annul the charters, reduce the popular assemblies to a manageable size, and increase the royal appointments; revise all the colonial acts, in order to set aside those which provided for the support of the ministers. “But, if the temper of the people makes it necessary, let a new bill for the purpose of supporting them pass the House, and the Council refuse their concurrence; if that will be improper, then the governor to negative it. If that cannot be done in good policy, then the bill to go home,”—that is, to England,–“and let the king disallow it. Let bishops be introduced, and provision be made for the support of the Episcopal clergy. Let the Congregational and Presbyterian clergy who will receive ordination be supported, and the leading ministers among them be bought off by large salaries. Let the liturgy be revised and altered. Let Episcopacy be accommodated as much as possible to the cast of the people. Let places of power, trust, and honor be conferred only upon Episcopalians, or those that will conform. When Episcopacy is once established, increase its resemblance to the English hierarchy at pleasure”! 5

The wealth of England had been created by the “commercial servitude” 6 of her American colonies; and not only this monopoly of the colonial trade, but the commerce itself, was endangered by the aggressions of France, which had surrounded the English colonies by a chain of forts and settlements which reached from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to the mouth of the Mississippi. To save her commerce, her wealth, and her revenue, England drove “the haughty and insolent Gallic” out of Canada; not without ruinous drafts of men and money, especially from the northern colonies, which thereby contracted enormous debts and oppressive taxes. But England represented her own debt as a bill incurred for the benefit of the colonies, and so “the Commons of Great Britain in Parliament, . . . for the purpose of raising a further REVENUE within his Majesty’s dominions of America,” assumed “to give and grant” to his Majesty “a stamp duty” of pounds, shillings, and pence, upon all sorts of documents used by merchants, lawyers, in courts and custom-houses, or in any of the transactions of daily life. No farmer or tradesman could hang an “almanac” in the chimney-corner without paying the “stamp duty of twopence” or “fourpence” if this hated act was enforced. But, long before the “first day of November, one thousand seven hundred and sixty-five,”—the day when it was to take effect,–there burst forth in the colonies such a universal storm of wrath, that it was suddenly manifest that the Church of England gospel of implicit obedience did not prevail in America.

“Your Majesty’s Commons in Britain,” said Mr. Burke, “undertake absolutely to dispose of the property of their fellow-subjects in America, without their consent. . . . for they are not represented in Parliament; and indeed we think it impracticable; it is not reconcilable to any ideas of liberty . . . . I only say, that a great people, who have their property, without any reserve, in all cases, disposed of by another people at an immense distance from them, will not think themselves in the enjoyment of freedom. It will be hard to show to those who are in such a state which of the usual parts of the definition or description of a free people are applicable to them . . . . Tell me what one character of liberty the Americans have, and what one brand of slavery they are free from, if they are bound in their property and industry by all the restraints you can imagine on commerce, and at the same time are made pack-horses of every tax you choose to impose, without the least share in granting them? When they bear the burdens of unlimited monopoly, will you bring them to bear the burdens of unlimited revenue too? The Englishmen in America will feel that this is slavery; that it is legal slavery, will be no compensation either to his feelings or understanding . . . . The feelings of the colonies were formerly the feelings of Great Britain; theirs were formerly the feelings of Mr. Hampden when called upon for the payment of twenty shillings. Would twenty shillings have ruined Mr. Hampden’s fortune? No; but the payment of half twenty shillings, on the principle upon which it was demanded, would have made him a SLAVE.”

Among the “Navigation Acts” was one of 6th George II., “An Act for the better securing and encouraging the Trade of his Majesty’s Colonies in America,” which was commonly called the “Molasses Act.” The articles of molasses and sugar, it was demonstrated by Mr. Otis, entered into every branch of our commerce, fisheries, manufactures, and agriculture. The duty of sixpence on molasses was full one-half of its value, and its enforcement would have ruined commerce. Mr. Otis roundly declared that if the King of Great Britain in person were encamped on Boston Common, at the head of twenty thousand men, with all his navy on our coast, he would not be able to execute these laws; for “taxation without representation was tyranny.” This was in 1762, when the tyrannical writs of assistance 7 were applied for, to search for and seize smuggled goods, and under which the sanctuary of no home, no dwelling, no treasure would be sacred from the pollution and violence of any catchpole ready for the odious service, backed by the forms of law.

John Adams said: “Wits may laugh at our fondness for molasses, and we ought all to join in the laugh with as much good humor as General Lincoln did. General Washington, however, always asserted and proved that Virginians loved molasses as well as New England men did. I know not why we should blush to confess that molasses was an essential ingredient in American independence. Many great events have proceeded from much smaller causes.”

These acts were repealed while America was in open resistance. “See what firmness and resolution will do,” said the Sons of Liberty, when a copy of the act of repeal was received in Boston. With this act of repeal was another, simply declaratory of the authority of Parliament to bind the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” “But,” said Junius, “it is truly astonishing that . . . they should have conceived that a compliance which acknowledged the rod to be in the hands of the Americans, could ever induce them to surrender it.” Mr. Greenville desired Mr. Knox’s opinion of the effects which the repeal would produce in America. The answer was, “Addresses of thanks and measures of rebellion.”

The contemporary accounts from every part of the colonies show that never before had there been such rejoicings in America. It is a source of supreme satisfaction to reflect that Dr. Mayhew lived to share in this triumph of liberty.

We naturally feel a certain curiosity as to the places which are associated with great names and memorable scenes. Fortunately we have a lively description of the Council Chamber as it was when James Otis so eloquently opposed the writs of assistance, written by one who then heard the great patriot lawyer, and was familiar with its aspect, adornment, and fittings. “Whenever,” said the venerable Adams, “you shall find a painter, male or female, I pray you to suggest a scene and subject: The scene is the Council Chamber of the Old Town House in Boston; the date is the month of February, 1761. That Council Chamber was as respectable an apartment, and more so too, in proportion, than the House of Lords of House of Commons in Great Britain, or that in Philadelphia in which the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. In this chamber, near the fire, were seated five judges, with Lieutenant-Governor Hutchinson at their head as Chief Justice, all in their new, fresh robes of scarlet English cloth, in their broad bands, and immense judicial wigs. In this chamber was seated, at a long table, all the barristers of Boston and its neighboring county of Middlesex, in their gowns, bands, and tye-wigs. They were not seated on ivory chairs, but their dress was more solemn and more pompous than that of the Roman senate when the Gauls broke in upon them. In a corner of the room must be placed wit, sense, imagination, genius, pathos, reason, prudence, eloquence, learning, science, and immense reading, hung by the shoulders on two crutches, covered with a cloth great-coat, in the person of Mr. Pratt, who had been solicited on both sides, but would engage on neither, being about to leave Boston forever, as Chief Justice of New York. Two portraits, at more than full length, of King Charles the Second and King James the Second, in splendid golden frames, were hung up on the most conspicuous side of the apartment. If my young eyes or old memory have not deceived me, these were the finest pictures I have seen. The colors of their long flowing robes and their royal ermines were the most glowing, the figures the most noble and graceful, the features the most distinct and characteristic: far superior to those of the King and Queen of France in the Senate Chamber of Congress. I believe they were Vandyke’s. Sure I am there was no painter in England capable of them at that time. They had been sent over, without frames, in Governor Pownall’s time; but, as he was no admirer of Charleses or Jameses, they were stowed away in a garret among rubbish till Governor Bernard came, had them leaned, superbly framed, and placed in council for the admiration and imitation of all men, no doubt with the concurrence of Hutchinson and all the junto.” . . .

“Now for the actors and performers. Mr. Gridley argued with his characteristic learning, ingenuity, and dignity, and said everything that could be said in favor of Cockle’s petition; all depending, however, on the—‘If the Parliament of Great Britain is the sovereign legislator of all the British empire.’ Mr. Thatcher followed him, on the other side, and argued with the softness of manners, the ingenuity, the cool reasoning which were peculiar to his amiable character. But Otis was a flame of fire. With a promptitude of classical allusions, a depth of research, a rapid summary of historical events and dates, a profusion of legal authorities, a prophetic glare of his eyes into futurity, and a rapid torrent of impetuous eloquence, he hurried away all before him. American Independence was then and there born. The seeds of patriots and heroes, to defend the Non Sine Diis Animosus Infans, to defend the vigorous youth, were then and there sown. Every man of an immense crowded audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take arms against writs of assistance. Then and there was the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born. In fifteen years—that is, in 1776—he grew up to manhood, and declared himself free.”

Dr. Chauncy, the preacher, was one of the greatest divines in New England, and no one except President Edwards and Dr. Jonathan Mayhew had been so much known among the literati of Europe. He was zealous for liberty, and, on the death of Dr. Mayhew, continued the war against its most specious enemy with great power and learning. He was born January 1, 1705, graduated at Harvard College in 1721, and was pastor of the first church in Boston from 1727 till his death in 1787.

This sermon—an admirable historical picture, drawn by a master, himself a leader of the hosts—abounds in facts, discusses the great principles involved with energy and power, and with the calmness and precision of the statesman.

The following witty lines, from the London “Craftsman” newspaper of March 29th, 1766, give a lively and just idea of the effect of the Stamp Act on British industry, temper, and politics.

CHAPTER IV. OF THE BOOK OF AMERICA.1. The men of the cities assemble. 3. Their discourse to each other. 11. They petition the Grand Sanhedrim. 14. The lamentation of George the Treasurer. 19. Newspapers. 22. And hireling Scribes. 25. These Scribes write against taking off the tribute. 26. The subject of their letters. 32. They prevail not. 34. But are answered. 38. The tribute taken off. 39. Great rejoicings thereat. 41. The song of the people.

1. After these things the men of London, and the men of Birmingham, and the men of the great cities and strong towns; even all who made cloth, and worked in iron and in steel, and in sundry metals, communed together.

2. And they met in the gates of their cities, and of their towns;

3. And they said unto each other, Behold now the children of America are waxed strong; and they have not only opposed he men who were sent by George the Treasurer to collect the tribute on the marks which are called stamps;

4. But they make unto themselves the wares wherewith we were wont to furnish them;

5. And they will buy no more of us unless this tribute is taken off:

6. And, moreover, they cannot pay unto us the monies which they owe; and the loss is great unto us, and the burthen thereof exceeding grievous:

7. Neither can we give bread unto those who labored for us; and behold! They, and their wives, and their little ones, have not bread to eat.

8. What then shall we do? and wherewithal shall we be comforted?

9. Shall we not petition our Lord the King, and his Princes, and the wise men of the nation, even the Grand Sanhedrim [Jewish high court convened in Europe by Napoleon] of the nation?

10. For we know that they are good and gracious, and will hearken to the voice of the people, who open their mouths and cry unto them for bread.

11. Then the men of London, and the men of the great cities, sat them down and wrote petitions.

12. And they sent men from amongst them, that were goodly men to look at; and they stood before the Grand Sanhedrim: [Jewish high court convened in Europe by Napoleon]

13. And they presented their petitions, and they were read, and days were appointed to consider them.

14. Now it came to pass, that while these things were doing, that George the late Treasurer, and those who had joined in laying the tribute on the stamps, were wroth, and their countenances fell;

15. And they said in themselves, If this tribute is taken off, then William the late Scribe, and those who are now in authority, and who have taken our places, will be had in remembrance of men.

16. And we also shall be had in remembrance, but it will be with evil remembrance indeed.

17. For behold the people will say, It is we that have cursed the land; and it is they who have blessed it.

18. Therefore we must bestir ourselves like men, to oppose the taking off the tribute, let whatsoever hap besides.

19. And in those days there were papers sold daily among the men of Britain, which declared those which were joined in marriage, those which were gathered unto their fathers, and those who had found favour in the eyes of the King and his rulers, and were exalted above their brethren,

20. And also of whatsoever was done in the land.

21. And these papers were called newspapers; and all men read them.

22. And there were certain also Scribes who let themselves out unto hire.

23. And one of the chief of these was a Levite, and his name was Anti Sejanus.

24. And these Scribes were hired to poison the minds of the people, and to cause them to set their faces against the men of America their brethren.

25. Then came Anti Sejanue, and Pacificus, and Pro Patria, and sundry other children of Belial, and they wrote letters which were put into the newspapers.

26. And they said in those letters, Men and brethren! Behold, the men of America are rich, and they are grown insolent, being full of bread;

27. And they are not mindful of the days of old when they were poor, but they would withdraw themselves from under the wings of their mother Britain.

28. And they would establish themselves as a people, and suffer us to have no power over them.

29. Behold, they have opposed the edict, and they are become as rebels.

30. Wherefore then go we not forth with a strong hand, and force them unto obedience to us?

31. And if they are still murmuring, and shall still oppose our authority, why do we not send fire and sword into their land, and cut them off from the face of the earth?

32. And these children of Belial who dipped their pens for hire, and would scatter plagues in wantonness, and say, This is sport;

33. Even these men wrote still more. Yet they prevailed not.

34. For they were answered, So the men of America are our brethren; they are the children of our forefathers; and shall we seek their blood? If they are mistaken shall we not pity them, and keep them obedient unto us through love?

35. For behold, it is a wise saying of old, That many files may be caught with a little honey; but with much vinegar ye can catch not one.

36. Neither are they inclined to be a people of themselves, but wish yet to be under our wing.

37. And the counsel of these men prevailed; for the counsel of the hireling Scribes was defeated; even as was the counsel of Achitophel in the days of David, King of Israel.

38. For behold, the Grand Sanhedrim took off the tribute from the people; and George THE GRACIOUS King of Britain assented thereto.

39. Then were great rejoicings made throughout the land; and fires were lighted up in the streets, and the people eat, drank, and were merry.

40. And they sang a new song, saying,

41. Long live the King; let his name be glorious, and may his rule over us be happy.

42. And may the princes and the rulers of the land, and the wise men of the Lord the King, and all those who joined to take off this tribute, be blessed.

43. For they have listened unto the cries of the people, and have given ear unto the voice of calamity; they have procured the payment of the debts of the merchants of this land, ease to the children of America, and labor and bread to the poor.

44. And the women shall sing their praises; and the little children shall lisp out, Bless the King and his Sanhedrim.

45. For we were desolate and distressed; our hammers and our shuttles were useless; for we got no work; neither had we bread to eat for ourselves, nor our little ones.

46. But now can we work, rejoice, and be exceeding glad.

47. And there was peace in the land.

48. But to Anti Sejanus and the rest of the hirelings there was shame, and the scorn of all good men fell upon them, and their employers, so that their names were had in abomination.

BY HIS EXCELLENCY

FRANCIS BERNARD, ESQ.,

Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief in and over His Majesty’s Province of Massachusetts Bay in New England, and Vice-Admiral of the same.

A PROCLAMATION

FOR A DAY OF PUBLIC THANKSGIVING.Whereas the House of Representatives of this Province having in the last session taken into their consideration the kind interposition of Providence in disposing our most gracious Sovereign and both Houses of Parliament to hearken to the united supplications of his dutiful and loyal Subjects in America, and to remove the great difficulties which the Colonies in general, and this Province in particular, labored under, occasioned by the Stamp Act, did resolve that the Governor be desired to appoint a Day of General Thanksgiving to be observed throughout this Province, that the good People thereof may have an opportunity in a public manner to express their Gratitude to Almighty GOD for his great Goodness in thus delivering them from their Anxiety and Distress and restoring the Province to its former Peace and Tranquility: which Resolution was concurred in by the Council, and has since been laid before me:

In pursuance of such Desire, so signified unto me, I have thought fit to appoint, and I do, by and with the advice of his Majesty’s Council, appoint Thursday, the twenty-fourth day of this instant July, to be a Day of Prayer and Thanksgiving; that the ministers of God’s holy word may thereupon assemble to return Thanks to Almighty God for his Mercies aforesaid, and to desire that he would be pleased to give his People Grace to make a right improvement of them, by observing and promoting a dutiful Submission to the Sovereign Power to which they are subordinate, and a brotherly Love and Affection to that People from whom they are derived, and to whom they are nearly related by civil Policy and mutual interests.

And I command and enjoin all Magistrates and Civil Officers to see that said Day be observed as a Day set apart for Religious Worship, and that no servile Labor be permitted therein.

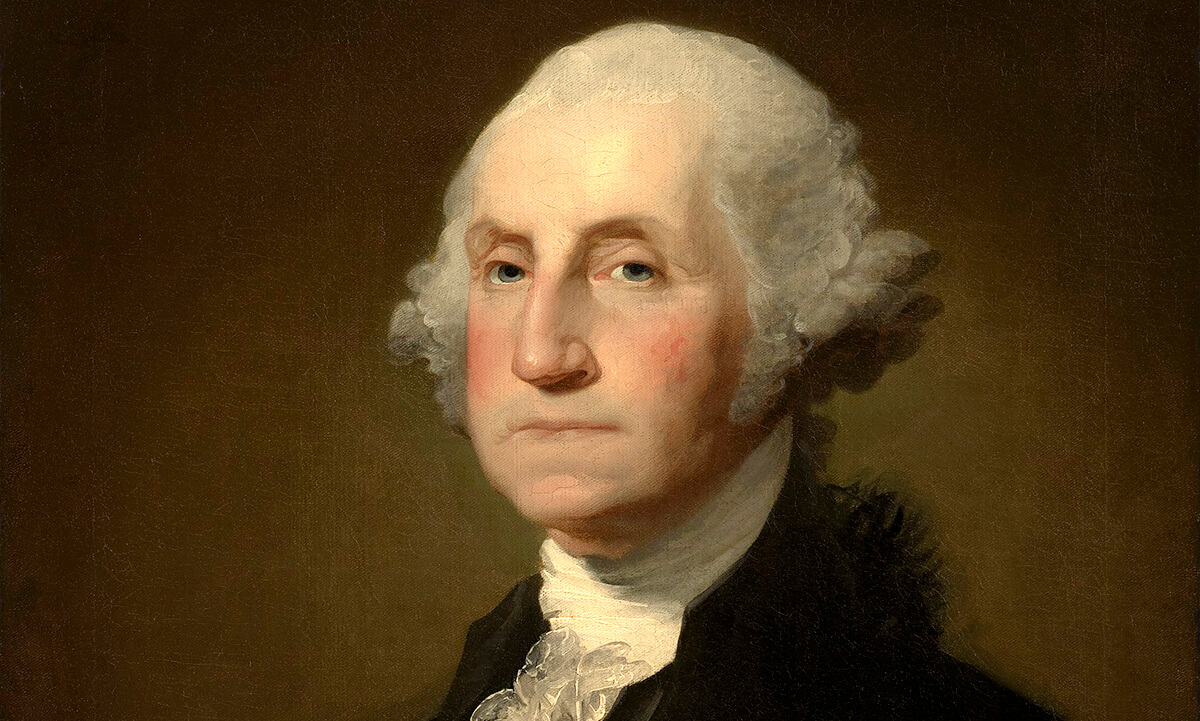

Given at the Council Chamber in Boston, the fourth day of July, 1766, in the Sixth year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord GEORGE the Third, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, KING, Defender of the Faith, etc.

FRA. BERNARD.

By His Excellency’s Command.

John Cotton, Dept. Sec’y.

God save the king.

DISCOURSE II.

A THANKSGIVING SERMON.

AS COLD WATERS TO A THIRSTY SOUL, SO IS GOOD NEWS FROM A FAR

COUNTRY.—Proverbs xxv. 25.

We are so formed by the God of nature, doubtless for wise and good ends, that the uneasy sensation to which we give the name of thirst is an inseparable attendant on the want of some proper liquid; and as this want is increased, such proportionably will be the increase of uneasiness; and the uneasiness may gradually heighten, till it throws one into a state that is truly tormenting. The application of cooling drink is fitted, by an established law of heaven, not only to remove away this uneasiness, but to give pleasure in the doing of it, by its manner of acting upon the organs of taste. There is scarce a keener perception of pleasure than that which is felt by one that is athirst upon being satisfied with agreeable drink. Hence the desire of spiritual good things, in those who have had excited in them a serious sense of God and religion, is represented, in the sacred books, by the “cravings of a thirsty man after drink.” Hence the devout David, when he would express the longing of his soul to “appear before God in his sanctuary,” resembles it to the “panting of a hart after the water-brooks.” In like manner, “cold water to a thirsty soul” is the image under which the wise man would signify, in my text, the gratefulness of “good news.” ‘T is refreshing to the soul, as cold waters to the tongue when parched with thirst. Especially is good news adapted to affect the heart with pleasure when it comes “from a far country,” and is big with important blessings, not to a few individuals only, but to communities, and numbers of them scattered over a largely extended continent.

Such is the “good news” lately brought us 8 from the other side the great waters. No news handed to us from Great Britain ever gave us a quicker sense, or higher degree, of pleasure. It rapidly spread through the colonies, and, as it passed along, opened in all hearts the springs of joy. The emotion of a soul just famished with thirst upon taking down a full draught of cold water is but a faint emblem of the superior gladness with which we were universally filled upon this great occasion. That was the language of our mouths, signifying the pleasurable state of our minds, “As cold waters to a thirsty soul, so is this good news from a far country.”

What I have in view is, to take occasion, from these words, to call your attention to some of the important articles contained in the good news we have heard, which so powerfully fit it to excite a pungent sense of pleasure in the breasts of all that inhabit these American lands. They way will then be prepared to point out to you the wisest and best use we can make of these glad tidings “from a far country.”

The first article in this “good news,” obviously presenting itself to consideration, is the kind and righteous regard the supreme authority 9 in England, to which we inviolably owe submission, has paid to the “commercial good” of the nation at home, and its dependent provinces and islands. One of the expressly assigned reasons for the repeal of the Stamp Act is declared in these words: “Whereas the continuance of said act may be productive of consequences greatly detrimental to the commercial interests of these kingdoms, may it therefore please”—The English colonies and islands are certainly included in the words “these kingdoms,” 10 for they are as truly parts of them as either Scotland, Ireland, or even England itself. It was therefore with a professed view to the commercial good, not only of the nation at home, but of the plantations also abroad, that the authority of the British King and Parliament interposed to render null and void that act, which, had it been continued in force, might in its consequences have tended to the hurt of this grand interest, inseparably connected with the welfare of both. From what more noble source could a repeal of this act have proceeded? Not merely the repeal, but that benevolent, righteous regard to the public good which gave it birth, is an important ingredient in the news that has made us glad. And wherein could this “good news” have been better adapted to soften our hearts, soothe our passions, and excite in us the sensations of unmingled joy? What that is conducive to our real happiness may we not expect from a King and Parliament whose regard to “the commercial interest” 11 of the British kingdoms has over powered all opposition from resentment, the display of sovereign pleasure, or whatever other cause, and influenced them to give up even a crown revenue for the sake of a greater national good! With what confidence may we rely upon such a supreme legislature for the redress of all grievances, especially in the article of trade, and the devising every wise and fit method to put and keep it in a flourishing state! Should anything, in time to come, unhappily be brought into event detrimental in its operation to the commerce between the mother country and these colonies, through misrepresentations from “lovers of themselves more than lovers” of their king and country, may we not encourage ourselves to hope that the like generous public spirit that has relieved us now will again interpose itself on our behalf? Happy are we in being under the government of a King and Parliament who can repeal as well as enact a law, upon a view of it as tending to the public happiness. How preferable is our condition to theirs who have nothing to expect but from the arbitrary will of those to whom they are slaves 12 rather than subjects!

Another thing, giving us singular pleasure, contained in this “good news,” is, the total removal of a grievous burden we must have sunk under had it been continued. Had the real state of the colonies been as well known at home as it is here, it is not easily supposable any there would have thought the tax imposed on us by the Stamp Act was suitably adjusted to our circumstances and abilities. There is scarce a man 13 in any of the colonies, certainly there is not in the New England ones, that would be deemed worthy of the name of a rich man in Great Britain. There may be here and there a rare instance of one that may have acquired twenty, thirty, forty, or fifty thousand pounds sterling,–and this is the most that an be made of what they may be thought worth,–but for the rest, they are, generally speaking, in a low condition, or, at best, not greatly rising above it; though in different degrees, variously placing them in the enjoyment of the necessities and comforts of life. And such it might naturally be expected would be the true state of the colonists; as the lands they possess in this new country could not have been subdued and fitted for profitable use but by labor too expensive to allow of their being, at present, much increased in wealth. This labor, indeed, may properly be considered as a natural tax, which, though it has made way for an astonishing increase of subjects to the British empire, greatly adding to its dignity and strength, has yet been the occasion of keeping us poor and low. It ought also to be remembered the occasions, in a new country, for the grant or purchase of property, with the obligations arising therefrom, and in instances of comparatively small value, are unavoidably more numerous than in those that have been long settled. The occasions, also, for recourse to the law are in like manner vastly multiplied; for which reason the same tax by stamped paper would take vastly more, in proportion, from the people here than in England. And what would have rendered this duty the more hard and severe is, that it must have been paid in addition to the government tax here, 14 which was, I have good reason to think, more heavy on us in the late war, and is so still, on account of the great debt then contracted, at least in this province, in proportion to our numbers and abilities, than that which, in every way, was laid on the people either of Scotland, Ireland, or England. 15 This, if mentioned cursorily, was never, that I remember, enlarged upon and set in a striking light in any of the papers written in the late times, as it might easily have been done, and to good purpose. Besides all which, it is undoubtedly true that the circulating money in all the colonies would not have been sufficient to have paid the stamp duty only for two years; 16 and an effectual bar was put in the way of the introduction of more 17 by the restraints that were laid upon our trade in those instances wherein it might in some measure have been procured.

It was this grievance that occasioned the bitter complaint all over these lands: “We are denied straw, and yet the full tale of bricks is required of us!” Or, as it was otherwise uttered, We must soon be obliged “to borrow money for the king’s tribute, and that upon our lands. Yet now our flesh is as the flesh of our brethren, our children as their children: and lo! We must bring into bondage our sons and our daughters to be servants.” We should have been stupid had not a spirit been excited in us to apply, in all reasonable ways, for the removal of so insupportable a burden. And such a union in spirit was never before seen in the colonies, nor was there ever such universal joy, as upon the news of our deliverance from that which might have proved a yoke the most grievous that was ever laid upon our necks. It affected in all hearts the lively perceptions of pleasure, filling our mouths with laughter. No man appeared without a smile in his countenance. No one met his friend but he bid him joy. That was our united song of praise, “Thou hast turned for us our mourning into dancing; thou hast put off our sackcloth, and girded us with gladness. Our glory (our tongue) shall sing praise to thee, and not be silent: O Lord our God! we will give thanks to thee forever.”

Another thing in this “news,” making it “good,” is, the hopeful prospect it gives us of being continued in the enjoyment of certain liberties and privileges, valued by us next to life itself. Such are those of being “tried by our equals,” and of “making grants for the support of government of that which is our own, either in person or by representatives we have chosen for the purpose.” Whether the colonists were invested with a right to these liberties and privileges which ought not to be wrested from them, or whether they were not, ‘tis the truth of fact that they really thought they were; all of them, as natural heirs to it by being born subjects to the British crown, and some of them by additional charter-grants, the legality of which, instead of being contested, have all along, from the days of our fathers, been assented to and allowed of by the supreme authority at home. And they imagined, whether justly or not I dispute not, that their right to the full and free enjoyment of these privileges was their righteous due, in consequence of what they and their forefathers had done and suffered in subduing and defending these American lands, not only for their own support, but to add extent, strength, and glory to the British crown. And as it had been early and deeply impressed on their minds that their charter privileges were rights that had been dearly paid for by a vast expense of blood, treasure, and labor, 18 without which this continent must have still remained in a wilderness state and the property of savages only, it could not but strongly put in motion their passion of grief when they were laid under a parliamentary restraint as to the exercise of that liberty they esteemed their greatest glory. It was eminently this that filled their minds with jealousy, and at length a settled fear, lest they should gradually be brought into a state of the most abject slavery. This it was that gave rise to the cry, which became general throughout the colonies, “We shall be made to serve as bond-servants; our lives will be bitter with hard bondage.” Nor were the Jews more pleased with the royal provision in their day, which, under God, delivered them from their bondage in Egypt, than were the colonists with the repeal of that act which had so greatly alarmed their fears and troubled their hearts. It was to them as “life from the dead.” They “rejoiced and were glad.” And it gave strength and vigor to their joy, while they looked upon this repeal not merely as taking off the grievous restraint that had been laid upon their liberties and privileges, but as containing in it an intention of continued indulgence 19 in the free exercise of them. ‘Tis in this view of it that they exult as those who are glad in heart,” esteeming themselves happy beyond almost any people now living on the face of the earth. May they ever be this happy people, and ever have “God for their Lord”!

This news is yet further welcome to us, as it has made way for the return of our love, in all its genuine exercises, towards those on the other side of the Atlantic who, in common with ourselves, profess subjection to the same most gracious sovereign. The affectionate regard of the American inhabitants for their mother country 20 was never exceeded by any colonists in any part or age of the world. We esteemed ourselves parts of one whole, members of the same collective body. What affected the people of England, affected us. We partook of their joys and sorrows—“rejoicing when they rejoiced, and weeping when they wept.” Adverse things in the conduct of Providence towards them alarmed our fears and gave us pain, while prosperous events dilated our hearts, and in proportion to their number and greatness. This tender sympathy with our brethren at home, it is acknowledged, began to languish from the commencement of a late parliamentary act. There arose hereupon a general suspicion whether they esteemed us brethren and treated us with that kindness we might justly expect from them. This jealousy, working in our breasts, cooled the fervor of our love; and had that act been continued in force, it might have gradually brought on an alienation of heart that would have been greatly detrimental to them, as it would also have been to ourselves. But the repeal, of which we have had authentic accounts, has opened the channels for a full flow of our former affection towards our brethren in Great Britain. Unhappy jealousies, uncomfortable surmising and heart-burnings, are now removed; and we perceive the motion of an affection for the country from whence our forefathers came, which would influence us to the most vigorous exertions, as we might be called, to promote their welfare, looking upon it, in a sense, our own. We again feel with them and for them, and are happy or unhappy as they are either in prosperous or adverse circumstances. We can, and do, with all sincerity, “pray for the peace of Great Britain, and that they may prosper that love her;” adopting those words of the devout Psalmist, “Peace be within thy walls, and prosperity within thy palaces. For our brethren’s sake we will say, peace be within thee.”

In fine, this news is refreshing to us “as cold waters to a thirsty soul,” as it has effected an alteration in the state of things among us unspeakably to our advantage. There is no way in which we can so strikingly be made sensible of this as by contrasting the state we were lately in, and the much worse one we should soon have been in had the Stamp Act been enforced, with that happy one we are put into by its repeal.

Upon its being made certain to the colonies that the Stamp Act had passed both Houses of Parliament, and received the king’s fiat, a general spirit of uneasiness at once took place, which, gradually increasing, soon discovered itself, by the wiser sons of liberty, 21 in a laudable endeavors to obtain relief; though by others, in murmurings and complaints, in anger and clamor, in bitterness, wrath, and strife; and by some evil-minded persons, taking occasion herefor from the general ferment 22 of men’s minds, in those violent outrages upon the property of others, which by being represented in an undue light, may have reflected dishonor upon a country which has an abhorrence of such injurious conduct. The colonies were never before in a state of such discontent, anxiety, and perplexing solicitude; some despairing of a redress, some hoping for it, and all fearing what would be the event. And, had it been the determination of the King and Parliament to have carried the Stamp Act into effect by ships of war and an embarkation of troops, their condition, however unhappy before, would have been inconceivably more so. They must either have submitted to what they thought an insupportable burden, and have parted with their property without any will of their own, or have stood upon their defence; in either of which cases their situation must have been deplorably sad. So far as I am able to judge from that firmness of mind and resolution of spirit which appeared among all sorts of persons, as grounded upon this principle, deeply rooted in their minds, that they had a constitutional right 23 to grant their own moneys and to be tried by their peers, ‘t is more than probable they would not have submitted 24 unless they had been obliged to it by superior power. Not that they had a thought in their hearts, as may have been represented, of being an independent people. 25 They esteemed it both their happiness and their glory to be, in common with the inhabitants of England, Scotland, and Ireland, the subjects of King George the Third, whom they heartily love and honor, and in defence of whose person and crown they would cheerfully expend their treasure, and lose even their blood. But it was a sentiment they had imbibed, that they should be wanting neither in loyalty to their king, or a due regard to the British Parliament, if they should defend those rights which they imagined were inalienable, upon the foot of justice, by any power on earth. 26 And had they, upon this principle, whether ill or well founded, stood upon their defence, what must have been the effect? There would have been opened on this American continent a most doleful scene of outrage, violence, desolation, slaughter, and, in a word, all those terrible evils that may be expected as the attendants on a state of civil war. No language can describe the distresses, in all their various kinds and degrees, which would have made us miserable. God only knows how long they might have continued, and whether they would have ended in anything short of our total ruin. Nor would the mother country, whatever some might imagine, have been untouched with what was doing in the colonies. Those millions that were due from this continent to Great Britain could not have been paid; a stop, a total stop, would have been put to the importation of those manufactures which are the support of thousands at home, often repeated. And would the British merchants and manufacturers have sat easy in such a state of things? There would, it may be, have been as much clamor, wrath, and strife in the very bowels of the nation as in these distant lands; nor could our destruction have been unconnected with consequences at home infinitely to be dreaded. 27

But the longed-for repeal has scattered our fears, removed our difficulties, enlivened our hearts, and laid the foundation for future prosperity, equal to the adverse state we should have been in had the act been continued and enforced.

We may now be easy in our minds—contented with our condition. We may be at peace and quiet among ourselves, every one minding his own business. All ground of complaint that we are “sold for bond-men and bond-women” is removed away, and, instead of being slaves to those who treat us with rigor, we are indulged the full exercise of those liberties which have been transmitted to us as the richest inheritance from our forefathers. We have now greater reason than ever to love, honor, and obey our gracious king, and pay all becoming reverence and respect to his two Houses of Parliament; and may with entire confidence rely on their wisdom, lenity, kindness, and power to promote our welfare. We have now, in a word, nothing to “make us afraid,” but may “sit every man under his vine and under his fig-tree,” in the full enjoyment of the many good things we are favored with in the providence of God.

Upon such a change in the state of our circumstances, we should be lost to all sense of duty and gratitude, and act as though we had no understanding, if our hearts did not expand with joy. And, in truth, the danger is lest we should exceed in the expressions of it. It may be said of these colonies, as of the Jewish people upon the repeal of the decree of Ahasuerus [Esther’s husband], which devoted them to destruction, they “had light and gladness, joy and honor; and in every province, and in every city, whithersoever the king’s commandment and his decree came, they had joy and gladness, a feast day, and a good day;” saying within themselves, “the Lord hath done great things for us, whereof we are glad.” May the remembrance of this memorable repeal be preserved and handed down to future generations, in every province, in every city, and in every family, so as never to be forgotten.

We now proceed—the way being thus prepared for it—to point out the proper use we should make of this “good news from a far country,” which is grateful to us “as cold waters to a thirsty soul.”

We have already had our rejoicings, in the civil sense, upon the “glad tidings” from our mother country; and ‘tis to our honor that they were carried on so universally within the bounds of a decent, warrantable regularity. There was never, among us, such a collection of all sorts of people upon any public occasion. Nor were the methods in which they signified their joy ever so beautifully varied and multiplied; and yet, none had reason to complain of disorderly conduct. The show was seasonably ended, and we had afterwards a perfectly quiet night. 28 There has indeed been no public disturbance since the outrage at Lieut. Governor Hutchinson’s house. That was so detested by town and country, and such a spirit at once so generally stirred up, particularly among the people, to oppose such villainous conduct, as has preserved us ever since in a state of as great freedom from mobbish actions as has been known in the country. Our friends at home, it should seem, have entertained fears lest upon the lenity and condescension of the King and Parliament we should prove ourselves a factious, turbulent people; and our enemies hope we shall. But ‘t is not easy to conceive on what the fears of the one or the hopes of the other should be grounded, unless they have received injurious representations of the spirit that lately prevailed in this as well as the other colonies, which was not a spirit to raise needless disturbances, or to commit outrages upon the persons or property of any, though some of those sons of wickedness which are to be found in all places 29 might take occasion, from the stand that was made for liberty, to commit violence with a high hand. There has not been, since the repeal, the appearance of a spirit tending to public disorder, nor is there any danger such a spirit should be encouraged or discovered, unless the people should be needlessly and unreasonably irritated by those who, to serve themselves, might be willing we should gratify such as are our enemies, and make those so who have been our good friends. But, to leave this digression:

Though our civil joy has been expressed in a decent, orderly way, it would be but a poor, pitiful thing should we rest here, and not make our religious, grateful acknowledgments to the Supreme Ruler 30 of the world, to whose superintending providence it is principally to be ascribed that we have had “given us so great deliverance.” Whatever were the means or instruments in order to this, that glorious Being, whose throne is in the heavens, and whose kingdom ruleth over all, had the chief hand herein. He sat at the helm, and so governed all things relative to it as to bring it to this happy issue. It was under his all-wise, overruling influence that a spirit was raised in all the colonies nobly to assert their freedom as men and English-born subjects—a spirit which, in the course of its operation, was highly serviceable, not by any irregularities it might be the occasion of (in this imperfect state they will, more or less, mix themselves with everything great and good), but by its manly efforts, setting forth the reasons they had for complaint in a fair, just, and strongly convincing light, hereby awakening the attention of Great Britain, opening the eyes of the merchants and manufacturers there, and engaging them, for their own interest as well as that of America, to exert themselves in all reasonable ways to help us. It was under the same all-governing influence that the late ministry, full of projections 31 tending to the hurt of these colonies, was so seasonably changed into the present patriotic one, 32 which is happily disposed, in all the methods of wisdom, to promote our welfare. It was under the same influence still that so many friends of eminent character were raised up and spirited to appear advocates on our behalf, and plead our cause with irresistible force. It was under this same influence, also, that the heart of our king and the British Parliament were so turned in favor to us as to reverse that decree which, had it been established, would have thrown this whole continent, if not the nation itself, into a state of the utmost confusion. In short, it was ultimately owing to this influence of the God of Heaven that the thoughts, the views, the purposes, the speeches, the writings, and the whole conduct of all who were engaged in this great affair were so overruled to bring into effect the desired happy event. 33

And shall we not make all due acknowledgments to the great Sovereign of the world on this joyful occasion? Let us, my brethren, take care that our hearts be suitably touched with a sense of the bonds we are under to the Lord of the universe; and let us express the joy and gratitude of our hearts by greatly praising him for the greatness of his goodness in thus scattering our fears, removing away our burdens, and continuing us in the enjoyment of our most highly valued liberties and privileges. And let us not only praise him with our lips, rendering thanks to his holy name, but let us honor him by a well-ordered conversation. “Behold, to obey is better than sacrifice;” and “to love the Lord our God with all our heart, and mind, and strength, and to love our neighbor as ourselves,” is better than whole burnt-offerings and sacrifices.” Actions speak much louder than words. In vain shall we pretend that we are joyful in God, or thankful to him, if it is not our endeavor, as we have been taught by the grace of God, which has appeared to us by Jesus Christ, to “deny all ungodliness and worldly lusts, and to live soberly, righteously, and godly in the world;” doing all things whatsoever it has pleased God to command us.

And as he has particularly enjoined it on us to be “subject to the higher powers, ordained by him to be his ministers for good,” we cannot, upon this occasion, more properly express our gratitude to him than by approving ourselves dutiful and loyal to the gracious king whom he has placed over us. Not that we can be justly taxed with the want of love or subjection to the British throne. We may have been abused by false and injurious representations upon this head; but King George the Third has no subjects—not within the realm of England itself—that are more strongly attached to his person and family, that bear a more sincere and ardent affection towards him, or that would exert themselves with more life and spirit in defence of his crown and dignity. But it may, notwithstanding, at this time, 34 be seasonable to stir up your minds by putting you in remembrance of your duty to “pray for kings, and all that are in subordinate authority under them,” and to “honor and obey them in the Lord.” And if we should take occasion, from the great lenity and condescending goodness of those who are supreme in authority over us, not to “despise government,” not to “speak evil of dignities,” not to go into any method of unseemly, disorderly conduct, but to “lead quiet and peaceable lives in all godliness and honesty,”—every man moving in his own proper sphere, and taking due care to “render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s,”—we should honor ourselves, answer the expectations of those who have dealt thus favorably with us, and, what is more, we should express a becoming regard to the governing pleasure of Almighty God.

It would also be a suitable return of gratitude to God if we entertained in our minds, and were ready to express in all proper ways, a just sense of the obligations we are under to those patrons of liberty and righteousness who were the instruments employed by him, and whose wise and powerful endeavors, under his blessing, were effectual to promote at once the interest of the nation at home, and of these distant colonies. Their names will, I hope, be ever dear to us, and handed down as such to the latest posterity. That illustrious name in special, Pitt, 35 will, I trust, be never mentioned but with honor, as the savior, under God, and the two kings who made him their prime minister, both of the nation and these colonies, not only from the power of France, but from that which is much worse, a state of slavery, under the appellation of Englishmen. May his memory be blessed! May his great services for his king, the nation, and these colonies, be had in everlasting remembrance!

To conclude: Let us be ambitious to make it evident, by the manner of our conduct, that we are good subjects and good Christians. So shall we in the best way express the grateful sense we have of our obligations to that glorious Being, to the wisdom and goodness of whose presidency over all human affairs it is principally owing that the great object of our fear and anxious concern has been so happily removed. And may it ever be our care to behave towards him so as that he may appear on our behalf in every time of danger and difficulty, guard us against evil, and continue to us all our enjoyments, both civil and religious. And may they be transmitted from us to our children, and to children’s children, as long as the sun and the moon shall endure. AMEN.

Endnotes

1 This phrase is from a tract, 1766, by Tucker, Dean of Gloucester. At that date he advocated “a separation, parting with the colonies entirely, and then making leagues of friendship with them, as with so many independent states;” but, said he, “it was too enlarged an idea for a mind wholly occupied within the narrow circle of trade,” and a “stranger to the revolutions of states and empires, thoroughly to comprehend, much less to digest.”

2 The answers of the Massachusetts Council, January 25th, and House of Representatives, January 26th, to Governor Hutchinson’s speech, January 6th, 1775, are rich in historical illustrations of this point, presented with great force of reason, and are decisive.

3 Life of Pepperell, by Usher Parsons, M.D. 3d ed. 1856, p. 52.

4 Mr. Arthus Lee, of Virginia, wrote from London, Sept. 22, 1771: “The Commissary of Virginia is now here, with a view of prosecuting the scheme of an American Episcopate. He is an artful, though not an able man. You will consider, sir, in your wisdom, whether any measures on your side may contribute to counteract this dangerous innovation. Regarding it as threatening the subversion of both our civil and religious liberties, it shall meet with all the opposition in my power.” To the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Massachusetts.

5 Dr. Stiles, in Gordon’s History of the American Revolution, i. 102, 103. Ed. 1794.

6 Burke.

7 Just as the above is going to press, there is brought to light, by Mr. David Roberts, an original volume of the Salem custom-house records, May 22, 1761-1775, which fills an important gap in the documentary history of the writs of assistance.—Hist. Collect. Essex Inst., August, 1860. 169.

8 The Massachusetts Gazette Extraordinary, Thursday, April 3, 1766, contains an account of the earliest rumor in Boston of the repeal, and of the public enthusiasm:–“Upon a Report from Philadelphia of the Repeal of the Stamp Act, on Tuesday last, a great Number of Persons assembled under Liberty Tree,”—near the corner of Essex and Washington streets,–“where two Field Pieces were carried, a Royal Salute fired, and three Huzzas given on such a joyful Piece of Intelligence. A considerable Number of the Inhabitants of this Town assembled at Faneuil-Hall on Tuesday last, when they made choice of the Hon. James Otis, Esq., as Moderator of the Meeting. The Moderator then acquainted the Assembly that the Probability of very soon receiving authentic Accounts of the absolute Repeal of the Stamp Act had occasioned the present Meeting; and as this would be an Event in which the Inhabitants of this Metropolis, as well as North America, would have the greatest Occasion of Joy, it was thought expedient by many that this Meeting should come into Measures for fixing the Time when those Rejoicings should be made, and the Manner in which they should be conducted; – whereupon it was

“Voted, That the Selectmen be desired, when they shall hear the certain News of the Repeal of the STAMP ACT, to fix upon a time for general Rejoicings; and that they give the Inhabitants seasonable Notice in such Manner as they shall think best.” The expressions of joy were as extravagant throughout England as they were in the colonies. “There were upwards of twenty men, booted and spurred, in the lobby of the Hon. House of Commons, ready to be dispatched express, by the merchants, to the different parts of Great Britain and Ireland, upon this important affair.”—Ed.

9 This doctrine was expressed by Mr. James Otis, early in 1764, that we “ought to yield obedience to an Act of Parliament, though erroneous, till repealed.” And by the Council and House of Representatives, Nov. 3d, 1764: “We acknowledge it to be our duty to yield obedience to it while it continues unrepealed.” But want of representation, and, next, that the colonies were not within the realm, soon led to a denial of the authority of Parliament, for a submission to a tax of a farthing would have abandoned the great principle. It was not the amount of the tax, but the right to tax, that was in issue. “In for a penny, in for a pound.”—Ed.

10 That “the colonies were without the realm and jurisdiction of Parliament,” was demonstrated in the learned and able answers of the Council and House of Representatives to Governor Hutchinson’s speech of January 6, 1773: “Your Excellency tells us, ‘you know of no line that can be drawn between the supreme authority of Parliament and the total independence of the colonies.’ If there be no such line, the consequence is, either that the colonies are the vassals of the Parliament, or that they are totally independent.” In his gratitude, Dr. Chauncy took quite too generous a view of the “repeal.” The interests of the colonies were always subordinate. The Navigation Act, 12th Chas. II. ch. 19, and the colonial policy of England, as of all nations, considered only the interests of the realm.—Ed.

11 Mr. Burke, in his speech on “American taxation,” years afterward, 1774, said the laws were repealed “because they raised a flame in America, for reasons political, not commercial: as Lord Hillsborough’s letter well expresses it, to regain ‘the confidence and affection of the colonies, on which the glory and safety of the British empire depend.’”—Ed.

12 “If we are not represented, we are slaves.”—Letter to Massachusetts agent, June 13, 1764.—Ed.

13 Mr. Burke, in 1763, showing the difficulties of American representation in Parliament, said: “Some of the most considerable provinces of America—such, for instance, as Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay—have not in each of them two men who can afford, at a distance from their estates, to spend a thousand pounds a year. How can these provinces be represented at Westminster?” Governor Pownall, at Boston, Sept. 6th, 1757, wrote to Admiral Holbourn: “I am here at the head and lead of what is called a rich, flourishing, powerful, enterprising country. ‘Tis all puff, ‘tis all false; they are ruined and undone in their circumstances. The first act I passed was an Act for the Relief of Bankrupts.”—Ed.

14 Massachusetts, of about two hundred and forty thousand inhabitants, expended in the war eight hundred and eighteen thousand pounds sterling, for four hundred and ninety thousand pounds of which she had no compensation. Connecticut, with only one hundred and forty-six thousand inhabitants, expended, exclusive of Parliament grants, upwards of four hundred thousand pounds sterling. Dr. Belknap’s pertinent inquiry, in view of he parliamentary pretence for their revenue acts “to defray the expenses of protecting, defending, and securing” the colonies, was, “If we had not done our part toward the protection and defence of our country, why were our expenditures reimbursed by Parliament,” even in part? Dr. Trumbull says that Massachusetts annually sent into the field five thousand five hundred men, and one year seven thousand. Connecticut had about three thousand men, in the field, and for some time six thousand, and for some years these two colonies alone furnished ten thousand men in actual service. Pennsylvania disbursed about five hundred thousand pounds, and was reimbursed only about sixty thousand pounds. New Hampshire, New York, and especially Rhode Island in her naval enterprise, displayed like zeal. Probably twenty thousand of these men were lost,–“the most firm and hardy young men, the flower of their country.” Many others were maimed and enervated. The population and settlement of the country was retarded, husbandry and commerce were injured. “At the same time, the war was unfriendly to literature, destructive of domestic happiness, and injurious to piety and the social virtues.”

In 1762 Mr. Otis said: “This province”—Massachusetts—“has, since the year 1754, levied for his Majesty’s service, as soldiers and seamen, near thirty thousand men, besides what have been otherwise employed. One year in particular it was said that every fifth man was engaged, in one shape or another. We have raised sums for the support of this war that the last generation could have hardly formed any idea of. We are now deeply in debt.”

Mr. Burke, in 1775, cited from their records “the repeated acknowledgment of Parliament that the colonies not only gave, but gave to satiety. This nation has formally acknowledged two things: first, that the colonies had gone beyond their abilities—Parliament having thought it necessary to reimburse them; secondly, that they had acted legally and laudably in their grants of money and their maintenance of troops, since the compensation is expressly given as a reward and encouragement.” Indeed, the “Albany Plan of Union,” a scheme by which America could protect herself against France, had been sent “home” for government approbation; but it was not sanctioned.—Ed.

15 I have been assured, by a gentleman of reputation and fortune in this town, that in the late time of war he sent one of his rate-bills to a correspondent of note in London for his judgment upon it, and had this answer in return from his friend: “That he did not believe there was a man in all England who paid so much, in proportion, towards the support of the government.” It will render the above account the more easily credible if I inform the reader that I have lately and purposely conversed with one of the assessors of this town, who has been annually chosen by them into this office for a great number of years, for which reason he may be thought a person of integrity, and one that may be depended on, and he declares to me that the assessment upon this town, particularly in one of the years when the tax on account of the war was great, was as follows: On personal estate, thirteen shillings and fourpence on the pound; that is to say, if a man’s income from money at interest, or in any other way, was sixty pounds per annum, he was assessed sixty times thirteen shillings and fourpence, and in this proportion, whether the sum was more or less. On real estate the assessment was at the rate of six years’ income; that is to say, if a man’s house or land was valued at two hundred pounds per annum income, this two hundred pounds was multiplied by six, amounting to twelve hundred pounds, and the interest of this twelve hundred pounds—that is, seventy-two pounds—was the sum he was obliged to pay. Besides this, the rate upon every man’s poll, and the polls of all the males in his house upwards of sixteen years of age, was about nineteen shillings lawful money, which is only one quarter part short of sterling. Over and above all this, they paid their part of an excise that was laid upon tea, coffee, rum, and wine, amounting to a very considerable sum.

How it was in the other provinces, or in the other towns of this, I know not; but it may be relied on as fact, that this was the tax levied upon the town of Boston; and it has been great ever since, though not so enormously so as at that time. Every one may now judge whether we had not abundant reason for mournful complaint when, in addition to the vast sums—considering our numbers and abilities—we were obliged to pay, we were loaded with the stamp duty, which would in a few years have taken away all our money, and rendered us absolutely incapable either of supporting the government here or of carrying on any sort of commerce, unless by an exchange of commodities.

16 Dr. Franklin testified, in 1766: “In my opinion there is not gold and silver enough in the colonies to pay the stamp duty for one year.”—Ed.

17 “Most of our silver and gold, . . . great part of the revenue of these kingdoms, . . . great part of the wealth we see,” says an English statistical writer of 1755, we “have from the northern colonies.” This silver and gold was obtained by the colonial trade with the West Indies, and other markets, where fish, rice, and other colonial products and British manufactures were sold or bartered. This coin, or bullion, was remitted to English merchants, monopolists, who always held a balance against the colonists. “The northern provinces import from Great Britain ten times more than they send in return to us.”—Burke. This left very little “circulating money” in their hands, and much of their trade had to be done by barter. The act of April 5, 1764, for raising a revenue in America, exacted the duties in specie, and at the same time the “regulations” for restricting their trade with the West Indies, enforced by armed vessels and custom officers, cruising on our coasts, suddenly destroyed this best portion of their commerce, and the flow of gold and silver through New England hands as quickly ceased. This spread a universal consternation throughout the colonies, and they likened the threatened slavery under George III. And the Parliament to the Hebrew bondage to Pharaoh.—Ed.

18 These various considerations were set forth at length in statements of the services and expenses of the colonies, which were sent to England to furnish the colonial agents with arguments why the colonies should not be taxed.—Ed.

19 The colonists claimed the repeal as matter of right, and not of favor. The English merchants urged it s a commercial necessity, and the politicians dared not do less. Hutchinson says: “The act which accompanied it, with the title of ‘Securing the Dependency of the Colonies,’ caused no alloy of the joy, and was considered as mere naked form.”—Ed.

20 This sentiment was ever appealed to in all our difficulties. Burke and Pitt made frequent use of it.—Ed.

21 This name, “SONS OF LIBERTY,” was used by Colonel Isaac Barre, in his off-hand reply to Charles Townshend, Wednesday, February 6, 1765, when George Grenville proposed the Stamp Act in Parliament. Jared Ingersoll heard Colonel Barre, and sent a sketch of his remarks to Governor Fitch, of Connecticut, who published it in the New London papers; and, says Bancroft, “May had not shed its blossoms before the words of Barre were as household words in every New England town. Midsummer saw it distributed through Canada, in French; and the continent rung from end to end with the cheering name Sons of Liberty.” Mr. Ingersoll, in a note to his pamphlet (New Haven, 1766), p. 16, says: “I believe I may claim the honor of having been the author of this title (Sons of Liberty), however little personal good I may have got by it, having been the only person, by what I can discover, who transmitted Mr. Barre’s speech to America.”

Boston voted that pictures of Colonel Barre and General Conway “be placed in Faneuil Hall, as a standing monument to all posterity of the virtue and justice of our benefactors, and a lasting proof of our gratitude.” But the pictures are not there; and Mr. Drake (History of Boston, p. 705) aptly suggests that the city “would lose none of its honor by replacing them.” The town of Barre, in Massachusetts, perpetuates the memory of this statesman, and of the public indignation toward Hutchinson, whose name it had borne from 1774 to 1777. Towns in Vermont, New York, and Wilkesbarre in Pennsylvania, also bear the honored name.—Ed.

22 In August, 1765, when Lieut. Governor Hutchinson’s house, Andrew Oliver’s, William Storey’s, and the stamp-office in Kilby Street, were ransacked or demolished. A minute account of places and names, and details in these riots, fill several interesting pages in Drake’s History of Boston, chap. lxix.; Bancroft’s United States, chap. xvi., 1765.

President Adams said, “None were indicted for pulling down the stamp-office, because this was thought n honorable and glorious action, not a riot.” And in 1775 he said: “I will take upon me to say, there is not another province on this continent, nor in his majesty’s dominions, where the people, under the same indignities, would not have gone to greater lengths.”

“I pardon something to the spirit of liberty,” said Burke.

The Bishop of St. Asaph said: “I consider these violence’s as the natural effects of such measures as ours on the minds of freemen.”—Ed.

23 The colonists may reasonably be excused for their mistake (if it was one) in thinking that they were vested with this constitutional right, as it was the opinion of Lord Camden, declared in the House of Lords, and of Mr. Pitt, signified in the House of Commons, that the Stamp Act was unconstitutional. This is said upon the authority of the public prints.

Lord Camden said: “The British Parliament have no right to tax the Americans . . . . Taxation and representation are coeval with and essential to this constitution.” Mr. Pitt said: “The Commons of America, represented in their several assemblies, have ever been in possession of the exercise of this, their constitutional right, of giving and granting their own money. They would have been slaves if they had not enjoyed it.”—Ed.

24 An examination of the newspapers and legislative proceedings of the period admits of no doubt of this. From the passage of the Stamp Act till certain news of its repeal, April, 1766, the newspaper, “The Boston Post Boy,” displayed for its heading, in large letters, these words: “The united voice of all His Majesty’s free and loyal subjects in America,–Liberty and Property, and no Stamps.”

Dr. Gordon says the Stamp Act was treated with the most indignant contempt, by being printed and cried about the streets under the title of The folly of ENGLAND and ruin of AMERICA.

It was now—May, 1765—that Patrick Henry, in bringing forward his resolutions against the act, exclaimed, “Caesar had his Brutus; Charles the First had his Cromwell; and George the Third”—“Treason!” cried the Speaker; “Treason!” cried many of the members—“may profit by their example,” was the conclusion of the sentence. “If this be treason,” said Henry, “make the most of it!”

President John Adams, referring to this sermon in 1815, said: “It has been a question, whether, if the ministry had persevered in support of the Stamp Act, and sent a military force of ships and troops to force its execution, the people of the colonies would then have resisted. Dr. Chauncy and Dr. Mayhew, in sermons which they preached and printed after the repeal of the Stamp Act, have left to posterity their opinions upon this question. If my more extensive familiarity with the sentiments and feelings of the people in the Eastern, Western, and Southern counties of Massachusetts may apologize for my presumption, I subscribe without a doubt to the opinions of Chauncy and Mayhew. What would have been the consequence of resistance in arms?” (See note to page 136.) Dr. Franklin, before the House of Commons in 1766, said: “Suppose a military force sent into America, they will find nobody in arms; what are they then to do? They cannot force a man to take stamps who chooses to do without them. They will not find a rebellion, but they can make one.”—Ed.

25 Not one of the English colonies, or provinces, would now submit for a moment to the control which the American colonies would then have cheerfully accepted. The royal governors are accepted as pageants on which to hang the local governments, which are essentially independent, but enjoy a nationality by this nominal connection with the crown; and it may be doubted if any of them have that degree of loyalty which once animated the “rebellious” colonies of 1776. Happily time has destroyed the animosities engendered by a vicious policy, and there is now that nobler unity (for we be brethren) which is cultivated by commerce and the amenities of literature and science. In this view, the cordial reception, at this time, of England’s royal representative in our chief cities, and by our National Executive, is an event of great interest. See p. 143 and note.—Ed.