Preface: There was a series of events that led to the need for this historical analysis. Below is a general chronology providing context. There were, no doubt, numerous other events that occurred– newspaper articles, magazine articles, government reports, meetings, etc.

However, these key events will preface the analysis:

January 20, 1993–William Jefferson Clinton assumes the Presidency, promising to end the historic ban on homosexuals serving in America’s Armed Forces.

January 29, 1993–President Clinton issues the following memorandum to the Secretary of Defense, Les Aspin:

I hereby direct you to submit to me prior to July 15, 1993, a draft of an Executive Order ending discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in determining who may serve in the Armed Forces of the United States.

June 2-21, 1993–survey entitled, “Congressional Survey of All Active-Duty Admirals and Generals Shows Overwhelming Opposition to Lifting Military Gay Ban.” Ninety-seven and a half percent do not wish to have homosexuals serve in the military. Over ninety percent of the military’s senior officers question “national security” if homosexuals are allowd to serve.

July 19, 1993–“Don’t ask; don’t tell” plan announced by the President. Under this plan, new recruits are not to be asked if they are homosexual. Homosexual “orientation” is allowed; homosexual conduct remains a reason for separation.

July 23, 1993–Senate Armed Services Committee votes to pass law supporting President Clinton’s policies.

July 27, 1993–House Armed Services Committee offers similar legislation.

Court challenges started by the ACLU and others, and debate rages in the media.

Elected officials and others begin requesting an historical perspective on homosexuals in the military. David Barton prepares the following essay, supporting the contention that immoral conduct never has been allowed in America’s Armed Forces.

In recent years, widespread discussions and hearings have been held concerning the issue of homosexuals serving in the United States military forces. This monograph will explore the issue via three questions:

- Has homosexuality always been incompatible with military service?

- Why should the military be concerned with a person’s morality?

- Why should homosexuality concern us as a society?

Has Homosexuality Always Been Incompatible With Military Service?

While the issue of homosexuals in the military has only recently become a point of great public controversy, it is not a new issue; it derives its roots from the time of the military’s inception. George Washington, the nation’s first Commander-in-Chief, held a strong opinion on this subject and gave a clear statement of his views on it in his general orders for March 14, 1778:

At a General Court Martial whereof Colo. Tupper was President (10th March 1778), Lieutt. Enslin of Colo. Malcom’s Regiment [was] tried for attempting to commit sodomy, with John Monhort a soldier; Secondly, For Perjury in swearing to false accounts, [he was] found guilty of the charges exhibited against him, being breaches of 5th. Article 18th. Section of the Articles of War and [we] do sentence him to be dismiss’d [from] the service with infamy. His Excellency the Commander in Chief approves the sentence and with abhorrence and detestation of such infamous crimes orders Lieutt. Enslin to be drummed out of camp tomorrow morning by all the drummers and fifers in the Army never to return; The drummers and fifers [are] to attend on the Grand Parade at Guard mounting for that Purpose. 1

General Washington held a clear understanding of the rules for order and discipline, and as the original Commander-in-Chief, he was the first not only to forbid, but even to punish, homosexuals in the military.

An edict issued by the Continental Congress communicates the moral tone which lay at the base of Washington’s actions:

The Commanders of . . . the thirteen United Colonies are strictly required to show in themselves a good example of honor and virtue to their officers and men and to be very vigilant in inspecting the behavior of all such as are under them, and to discountenance and suppress all dissolute, immoral, and disorderly practices, and also such as are contrary to the rules of discipline and obedience, and to correct those who are guilty of the same. 2

Noah Webster–a soldier during the Revolution and the author of the first American dictionary –defined the terms “dissolute” and “immoral” used by Congress:

Dissolute:

Loose in behavior and morals; given to vice and dissipation; wanton; lewd; debauched; not under the restraints of law; as a dissolute man: dissolute company.

Immoral:

Inconsistent with moral rectitude; contrary to the moral or Divine law. . . . Every action is immoral which contravenes any Divine precept or which is contrary to the duties which men owe to each other. 3

This meaning of the word “moral” versus “immoral” was understood throughout American society; the practice of sodomy was clearly adverse to and “contravene[d] Divine precept.” The order to “suppress all dissolute, immoral, and disorderly practices . . . contrary to the rules of discipline and obedience” was extended throughout all branches of the American military, both the Army and the Navy. 4

It can be safely said that the attitude of the Founders on the subject of homosexuality was precisely that given by William Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Laws–the basis of legal jurisprudence in America and heartily endorsed by numbers of significant Founders. 5

In addressing sodomy (homosexuality), he found the subject so reprehensible that he was ashamed even to discuss it. Nonetheless, he noted:

What has been here observed . . . [the fact that the punishment fit the crime] ought to be the more clear in proportion as the crime is the more detestable, may be applied to another offence of a still deeper malignity; the infamous crime against nature committed either with man or beast. A crime which ought to be strictly and impartially proved and then as strictly and impartially punished. . . .

I will not act so disagreeable part to my readers as well as myself as to dwell any longer upon a subject the very mention of which is a disgrace to human nature [sodomy]. It will be more eligible to imitate in this respect the delicacy of our English law which treats it in its very indictments as a crime not fit to be named; “peccatum illud horribile, inter christianos non nominandum” (that horrible crime not to be named among Christians). A taciturnity observed likewise by the edict of Constantius and Constans: “ubi scelus est id, quod non proficit scire, jubemus insurgere leges, armari jura gladio ultore, ut exquisitis poenis subdantur infames, qui sunt, vel qui futuri sunt, rei” (where that crime is found, which is unfit even to know, we command the law to arise armed with an avenging sword that the infamous men who are, or shall in future be guilty of it, may undergo the most severe punishments). 6

Because of the nature of the crime, the penalties for the act of sodomy were often severe. For example, Thomas Jefferson indicated that in his home state of Virginia, “dismemberment” of the offensive organ was the penalty for sodomy. 7

In fact, Jefferson himself authored a bill penalizing sodomy by castration. 8The laws of the other states showed similar or even more severe penalties:

That the detestable and abominable vice of buggery [sodomy] . . . shall be from henceforth adjudged felony . . . and that every person being thereof convicted by verdict, confession, or outlawry [unlawful flight to avoid prosecution], shall be hanged by the neck until he or she shall be dead.9 NEW YORK

That if any man shall lie with mankind as he lieth with womankind, both of them have committed abomination; they both shall be put to death.10 CONNECTICUT

Sodomy . . . shall be punished by imprisonment at hard labour in the penitentiary during the natural life or lives of the person or persons convicted of th[is] detestable crime. 11 GEORGIA

That if any man shall commit the crime against nature with a man or male child . . . every such offender, being duly convicted thereof in the Supreme Judicial Court, shall be punished by solitary imprisonment for such term not exceeding one year and by confinement afterwards to hard labor for such term not exceeding ten years. 12 MAINE

That if any person or persons shall commit sodomy . . . he or they so offending or committing any of the said crimes within this province, their counsellors, aiders, comforters, and abettors, being convicted thereof as above said, shall suffer as felons. 13

[And] shall forfeit to the Commonwealth all and singular the lands and tenements, goods and chattels, whereof he or she was seized or possessed at the time . . . at the discretion of the court passing the sentence, not exceeding ten years, in the public gaol or house of correction of the county or city in which the offence shall have been committed and be kept at such labor. 14 PENNSYLVANIA

[T]he detestable and abominable vice of buggery [sodomy] . . . be from henceforth adjudged felony . . . and that the offenders being hereof convicted by verdict, confession, or outlawry [unlawful flight to avoid prosecution], shall suffer such pains of death and losses and penalties of their goods.15 SOUTH CAROLINA

That if any man lieth with mankind as he lieth with a woman, they both shall suffer death. 16

Based on the statutes, legal commentaries, and the writings of prominent military leaders, it is clear that any idea of homosexuals serving in the military was considered with repugnance; this is incontrovertible, with no room for differing interpretations. 17

The thought of lifting this proscription is a modern phenomenon, and would have brought disbelief, disdain, and condemnation from those who established our Armed Forces.

Why Should the Military Be Concerned With a Person’s Morality?

Concern for the character and morality of military personnel has a strong historical basis. Our Founding Fathers recognized the importance of pure morals in our free society, and that philosophy extended to our military.

Before considering the importance of morality to the military, first consider some general statements on the importance of morality by those responsible for originally creating the rules that have stirred so much controversy of late in the debate over homosexuals in the military. John Adams (the founder of the Navy), on October 13, 1798, while serving as President of the United States and Commander-in-Chief, told the military:

We have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. . . . Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other. 18

Adams similarly explained:

Statesmen, my dear sir, may plan and speculate for liberty, but it is religion and morality alone which can establish the principles upon which freedom can securely stand. The only foundation of a free constitution is pure virtue. 19

George Washington, the nation’s first Commander-in-Chief, summarized the same truth in his “Farewell Address.” Significantly, this address was also partially authored by John Jay (the author of America’s first military discipline manual) and Alexander Hamilton (a General during the Revolution). These three military leaders emphasized the necessity of moral behavior, declaring:

Of all the dispositions and habits which leads to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity [happiness]. Let it simply be asked, “Where is the security for property, for reputation for life, if the sense of religious obligations desert . . . ?” And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle. ‘Tis substantially true that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule, indeed, extends with more or less force to every species of free government. Who that is a sincere friend to it [free government] can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric? 20

Since moral behavior was necessary for society in general, it was even more necessary for military personnel in whose hands rested the security, and thus the future, of the nation. The importance of good morals in the military can be seen in the following three selections from Washington’s general orders:

It is required and expected that exact discipline be observed and due subordination prevail thro’ the whole Army, as a failure in these most essential points must necessarily produce extreme hazard, disorder, and confusions; and end in shameful disappointment and disgrace. The General most earnestly requires and expects a due observance of those articles of war established for the government of the Army which forbid profane cursing, swearing, and drunkenness; And in like manner requires and expects of all officers and soldiers not engaged on actual duty a punctual attendance on Divine service to implore the blessings of Heaven upon the means used for our safety and defence.21

His Excellency [George Washington] wishes [it] to be considered that an Army without order, regularity, and discipline is no better than a commissioned mob; Let us therefore . . . endeavor by all the skill and discipline in our power, to acquire that knowledge and conduct which is necessary in war–our men are brave and good; men who with pleasure it is observed are addicted to fewer vices than are commonly found in Armies; but it is subordination and discipline (the life and soul of an Army) which next under Providence, is to make us formidable to our enemies, honorable in ourselves, and respected in the world.22

Purity of morals being the only sure foundation of public happiness in any country and highly conducive to order, subordination, and success in an Army, it will be well worthy the emulation of officers of every rank and class to encourage it both by the influence of example and the penalties of authority. It is painful to see many shameful instances of riot and licentiousness. . . . A regard to decency should conspire with a sense of morality to banish a vice productive of neither advantage or pleasure.23

Consequently, moral improprieties were met with severe punishment in the American military– as illustrated by the opening example in this paper.

Why Should Homosexuality Concern a Society?

Public discussions concerning homosexuality are a purely recent phenomenon; it was long considered too morally abhorrent and reprehensible to openly discuss. Consider, for example, the legal works of James Wilson, a signer both of the Declaration and the Constitution and appointed by President Washington as an original Justice on the US Supreme Court. Wilson was responsible for laying much of the foundation of American Jurisprudence and was co-author of America’s first legal commentaries on the Constitution. Even though state law books of the day addressed sodomy, when Wilson came to it in his legal writings, he was too disgusted with it even to mention it. He thus declared:

The crime not to be named [sodomy], I pass in a total silence.24

America’s first law book, authored by founding jurist Zephaniah Swift, communicated the popular view concerning sodomy:

This crime, tho repugnant to every sentiment of decency and delicacy, is very prevalent in corrupt and debauched countries where the low pleasures of sensuality and luxury have depraved the mind and degraded the appetite below the brutal creation. Our modest ancestors, it seems by the diction of the law, had no idea that a man would commit this crime [anal intercourse with either sex]. . . . [H]ere, by force of common law, [it is] punished with death. . . . [because of] the disgust and horror with which we treat of this abominable crime. 25

John David Michaelis, author of an 1814 four-volume legal work, outlined why homosexuality must be more strenuously addressed and much less tolerated than virtually any other moral vice in society:

If we reflect on the dreadful consequences of sodomy to a state, and on the extent to which this abominable vice may be secretly carried on and spread, we cannot, on the principles of sound policy, consider the punishment as too severe. For if it once begins to prevail, not only will boys be easily corrupted by adults, but also by other boys; nor will it ever cease; more especially as it must thus soon lose all its shamefulness and infamy and become fashionable and the national taste; and then . . . national weakness, for which all remedies are ineffectual, most inevitably follow; not perhaps in the very first generation, but certainly in the course of the third or fourth. . . . To these evils may be added yet another, viz. that the constitutions of those men who submit to this degradation are, if not always, yet very often, totally destroyed, though in a different way from what is the result of whoredom.

Whoever, therefore, wishes to ruin a nation, has only to get this vice introduced; for it is extremely difficult to extirpate it where it has once taken root because it can be propagated with much more secrecy . . . and when we perceive that it has once got a footing in any country, however powerful and flourishing, we may venture as politicians to predict that the foundation of its future decline is laid and that after some hundred years it will no longer be the same . . . powerful country it is at present.26

In view of the arguments listed by historical and legal sources, there is substantial

merit for maintaining the ban on homosexuals in the military. 27

The Founders instituted this ban with a clear understanding of the damaging effects of this behavior on the military. This ban has remained official policy for over 200 years and one would be hard-pressed to perceive the need for altering a policy which has contributed to making America the world’s foremost military power.

Endnotes

1 George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, John C. Fitzpatrick, editor (Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1934), Vol. XI, pp. 83-84, from General Orders at Valley Forge on March 14, 1778.

2 Journals of the American Congress (Washington: Way and Gideon, 1823), Vol. I, p. 185, on November 28, 1775.

3 Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1849).

4 Acts Passed at the First Session of the Fifth Congress of the United States of America (Philadelphia: Richard Folwell, 1797), pp. 456-457.

5 See, for example, James Madison, Letters and Other Writings of James Madison (NY: R. Worthington, 1884), Vol. III, p. 233, in his letter dated October 18, 1821. See also the writings of Founders James Kent, James Wilson, Fisher Ames, Joseph Story, John Adams, Henry Laurens, Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, James Otis, et. al.

6 Sir William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1769), Vol. IV, pp. 215-216.

7 Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Philadelphia: Matthew Carey, 1794), p. 211.

8 Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Andrew A. Lipscomb, editor (Washington, D. C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. I, pp. 226-227, from Jefferson’s “For Proportioning Crimes and Punishments.”

9 Laws of the State of New-York . . . Since the Revolution (New York: Thomas Greenleaf, 1798), Vol. I, p. 336.

10 The Public Statute Laws of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), Book I, p. 295.

11 A Digest of the Laws of the State of Georgia (Milledgeville: Grantland & Orme, 1822), p. 350.

12 Laws of the State of Maine (Hallowell: Goodale, Glazier & Co., 1822), p. 58.

13 Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1810), Vol. I, p. 113.

14 Collinson Read, An Abridgment of the Laws of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, 1801), p. 279.

15 Alphabetical Digest of the Public Statute Laws of South-Carolina (Charleston: John Hoff, 1814), Vol. I, p. 99.

16 Statutes of the State of Vermont (Bennington, 1791), p. 74.

17 Randy Shilts’ revisionist work, Conduct Unbecoming, attempts to provide historical precedent for homosexuals in the military by claiming that the General Baron von Steuben, a Prussian fighting for the American cause, was gay (see also Newsweek, Feb. 1, 1993, “What’s Fair in Love and War,” pp. 58-59). Shilts’ accusations against von Steuben are unacceptable to the very source he cites–a biography authored by John Palmer (see John McAuley Palmer, General Von Steuben, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937). Palmer, although acknowledging an anonymous 1777 letter accusing the Baron of sexual improprieties, concluded that it was “probably a malicious slander that originated among Steuben’s enemies,” further stating that “the charge is inconsistent with the conception of Steuben’s personality that has grown up in my mind after eight years’ study.” Additionally, Shilts claims that the Baron’s 17 year old interpreter, Pierre Etienne Du Ponceau, was his lover, citing his youth and lack of linguistic skills as proof. However, Thomas McKean, signer of the Declaration of Independence, says that Du Ponceau had offered “satisfactory proof of his knowledge in the languages.” Furthermore, the Dictionary of American Biography says of the married Frenchman that “his contributions to historical and linguistic literature were numerous, particularly on philological subjects.” Shilts’ claims lack credible historical documentation, and are a hindrance to any substantive debate on this extremely important issue.

18 John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Little, Brown, 1854), Vol. IX, p. 229, dated October 11, 1798.

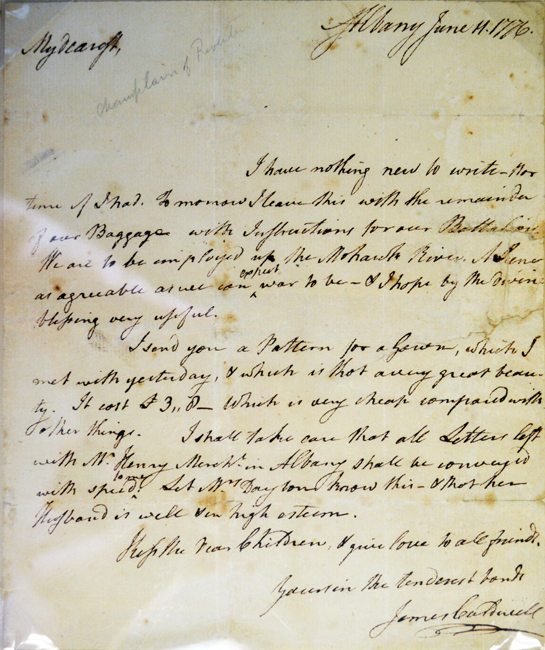

19 Ibid, Vol. IX, p. 401, dated June 21, 1776.

20 Address of George Washington . . . Preparatory to His Declination (Baltimore: Christopher Jackson, 1796), pp. 22-24.

21 Washington, Writings, Vol. III, p. 309, from General Orders from Cambridge on July 4, 1775.

22 Ibid, at Vol. IV, pp. 202-203, from General Orders from Cambridge on January 1, 1776.

23 Ibid, Vol. XIII, pp. 118-119, from General Orders from Fredericksburgh on October 21, 1778.

24 James Wilson, The Works of James Wilson (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1967), Vol. II, p. 656, from lectures given in 1790 and 1791.

25 Zephaniah Swift, A System of Laws of the State of Connecticut (Windham: John Byrne, 1796), Vol. II, pp. 310-311.

26 Sir John David Michaelis, Commentaries on the Laws of Moses, Alexander Smith, translator (London: F. C. and J. Rivington, 1814), Vol. IV, pp. 115-117.

27 For a summary of the current medical and military arguments supporting the ban on homosexuals, see Gays: In or Out? The U. S. Military & Homosexuals–A Sourcebook, by Col. Ronald D. Ray, USMCR (NY: A Maxwell Macmillan Company, 1993). Col. Ray’s Bibliography lists many of the numerous books and studies detailing homosexuality’s inherent physiological, sociological, and psychological problems.

* This article concerns a historical issue and may not have updated information.

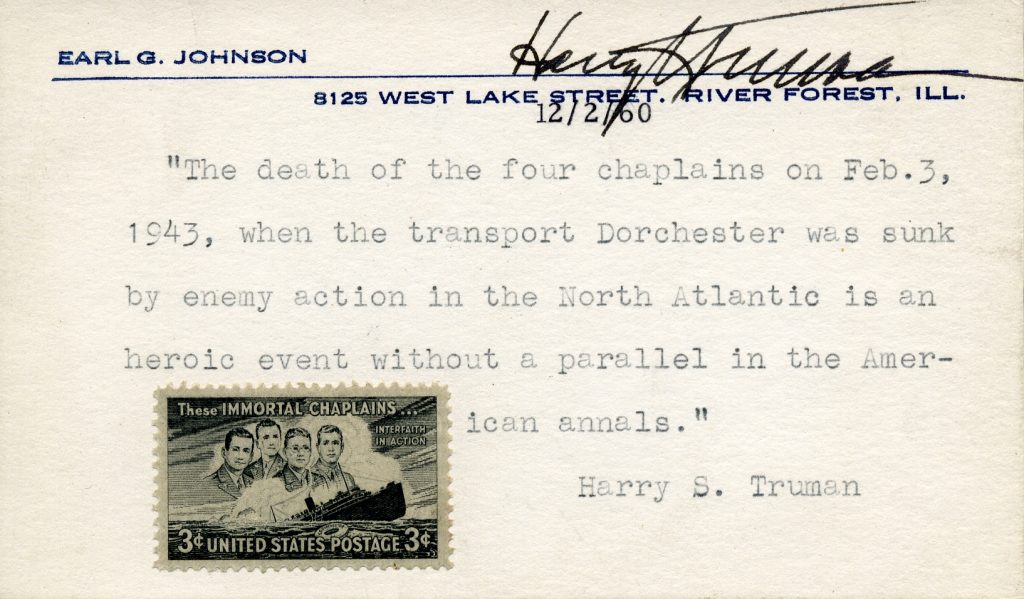

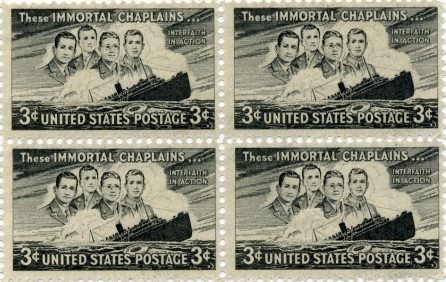

America has a long history of military members who have shown extraordinary courage, with many willingly giving their lives to secure the freedoms our nation enjoys, freedoms we often take for granted. On Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day1) we honor the sacrifice of these brave men and women.

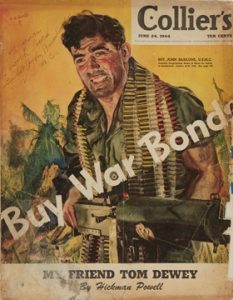

America has a long history of military members who have shown extraordinary courage, with many willingly giving their lives to secure the freedoms our nation enjoys, freedoms we often take for granted. On Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day1) we honor the sacrifice of these brave men and women. One amazing example of heroism occurred during the Campaign of Guadalcanal (August 1942-February 1943).4 Sergeant John Basilone and his handful of men were responsible for holding back a Japanese assault of thousands on October 24-25, 1942. Basilone, throughout this engagement, personally repaired and manned multiple machine guns. At times, he was unable to shoot his guns over the piles of dead Japanese who fell at the brink of his hill. When his small detachment ran low, Basilone fought his way through the Japanese lines to resupply critically-needed ammunition. The Americans eventually won this long campaign. As a result of his actions, Basilone was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.5 (The picture on the left is of a magazine personally signed by Basilone, one of the many World War II treasures we have in WallBuilders’ Collection.)

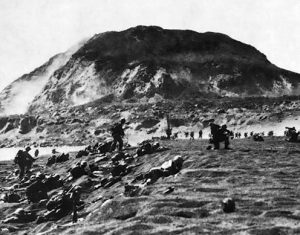

One amazing example of heroism occurred during the Campaign of Guadalcanal (August 1942-February 1943).4 Sergeant John Basilone and his handful of men were responsible for holding back a Japanese assault of thousands on October 24-25, 1942. Basilone, throughout this engagement, personally repaired and manned multiple machine guns. At times, he was unable to shoot his guns over the piles of dead Japanese who fell at the brink of his hill. When his small detachment ran low, Basilone fought his way through the Japanese lines to resupply critically-needed ammunition. The Americans eventually won this long campaign. As a result of his actions, Basilone was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.5 (The picture on the left is of a magazine personally signed by Basilone, one of the many World War II treasures we have in WallBuilders’ Collection.) Later in the war at the Battle of Iwo Jima (February 19-March 26, 1945),6 Basilone came ashore with the first wave of Marines. Shortly after landing, his unit was trapped by machine guns from Japanese blockhouses. Basilone worked his way around one of these blockhouses and single-handedly destroyed it. Later, as he was making his way towards an airfield, he came across an American tank trapped in a minefield. While under fire, he guided the tank out of the minefield and to safety. He was later killed by flying shrapnel. Basilone was awarded the Navy Cross for his courageous actions during the battle.7

Later in the war at the Battle of Iwo Jima (February 19-March 26, 1945),6 Basilone came ashore with the first wave of Marines. Shortly after landing, his unit was trapped by machine guns from Japanese blockhouses. Basilone worked his way around one of these blockhouses and single-handedly destroyed it. Later, as he was making his way towards an airfield, he came across an American tank trapped in a minefield. While under fire, he guided the tank out of the minefield and to safety. He was later killed by flying shrapnel. Basilone was awarded the Navy Cross for his courageous actions during the battle.7