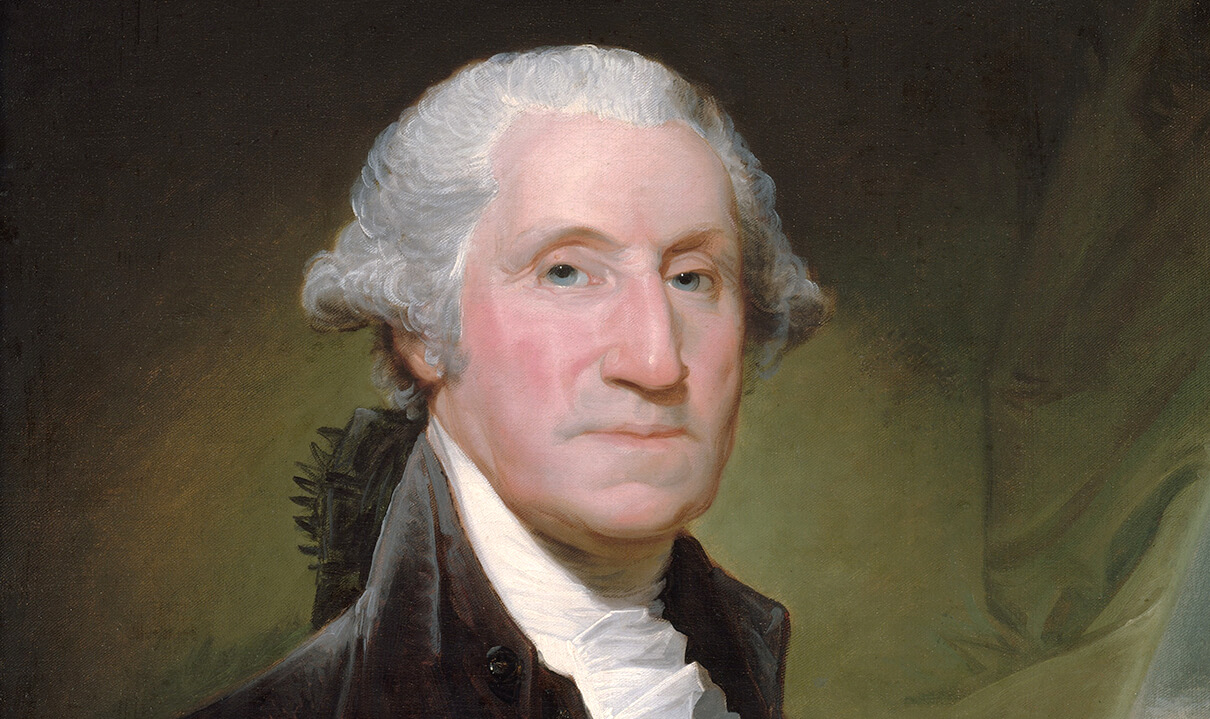

This is a question often asked today, and it arises from the efforts of those who seek to impeach Washington’s character by portraying him as irreligious. Interestingly, Washington’s own contemporaries did not question his Christianity but were thoroughly convinced of his devout faith–a fact made evident in the first-ever compilation of the The Writings of George Washington, published in the 1830s.

That compilation of Washington’s writings was prepared and published by Jared Sparks (1789-1866), a noted writer and historian. Sparks’ herculean historical productions included not only the writings of George Washington (12 volumes) but also Benjamin Franklin (10 volumes) and Constitution signer Gouverneur Morris (3 volumes). Additionally, Sparks compiled the Library of American Biography (25 volumes), The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution (12 volumes), and the Correspondence of the American Revolution (4 volumes). In all, Sparks was responsible for some 100 historical volumes. Additionally, Sparks was America’s first professor of history–other than ecclesiastical history–to teach at the college level in the United States, and he was later chosen president of Harvard.

Jared Sparks’ decision to compile George Washington’s works is described by The Dictionary of American Biography. It details that Sparks began . . .

. . . what was destined to be his greatest life work, the publication of the writings of George Washington. [Supreme Court] Justice Bushrod Washington, [the nephew of George Washington, the executor of the Washington estate, and] the owner of the Washington manuscripts, was won over by an offer to share the profits, through the friendly mediation of Chief Justice [of the Supreme Court, John] Marshall [who from 1804-1807 had written a popular five volume biography of George Washington], who also consented to take an equal share, twenty-five per cent, with the owner. In January 1827, Sparks found himself alone at Mount Vernon with the manuscripts. An examination of them extending over three months showed that years would be required for the undertaking; and with the owner’s consent, Sparks carried off the entire collection, eight large boxes, picking up on the way to Boston a box of diplomatic correspondence from the Department of State, and the [General Horatio] Gates manuscripts from the New York Historical Society. Not content with these, he searched or caused to be searched public and private archives for material, questioned survivors of the Revolution, visited and mapped historic sites. In 1830, for instance, he followed [Benedict] Arnold’s [1775] route to Quebec. The first of the twelve volumes of The Writings of George Washington to be published (vol. II) appeared in 1834 and the last (vol. I, containing the biography) in 1837.

In Volume XII of these writings, Jared Sparks delved into the religious character of George Washington, and included numerous letters written by the friends, associates, and family of Washington which testified of his religious character. Based on that extensive evidence, Sparks concluded:

To say that he [George Washington] was not a Christian would be to impeach his sincerity and honesty. Of all men in the world, Washington was certainly the last whom any one would charge with dissimulation or indirectness [hypocrisies and evasiveness]; and if he was so scrupulous in avoiding even a shadow of these faults in every known act of his life, [regardless of] however unimportant, is it likely, is it credible, that in a matter of the highest and most serious importance [his religious faith, that] he should practice through a long series of years a deliberate deception upon his friends and the public? It is neither credible nor possible.

One of the letters Sparks used to arrive at his conclusion was from Nelly Custis-Lewis. While Nelly technically was the granddaughter of the Washingtons, in reality she was much more.

When Martha [Custis] married George, she was a widow and brought two young children (John and Martha–also called Patsy) from her first marriage into her marriage with George. The two were carefully raised by George and Martha, later married, and each had children of their own. Unfortunately, tragedy struck, and both John and Patsy died early (by 1781). John left behind his widow and four young children ranging in age from infancy to six years old.

At the time, Washington was still deeply involved in guiding the American Revolution and tried unsuccessfully to convince Martha’s brother to raise the children. The young widow of John was unable to raise all four, so George and Martha adopted the two younger children: Nelly Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis, both of whom already were living at Mount Vernon.

Nelly lived with the Washingtons for twenty years, from the time of her birth in 1779 until 1799, the year of her marriage and of George Washington’s untimely death. She called George and Martha her “beloved parents whom I loved with so much devotion, to whose unceasing tenderness I was indebted for every good I possessed.”

Nelly was ten years old when Washington was called to the Presidency, and she grew to maturity during his two terms. During that time, she traveled with Washington and walked amidst the great foreign and domestic names of the day. On Washington’s retirement, she returned with the family to Mount Vernon. Nelly was energetic, spry, and lively, and was the joy of George Washington’s life. She served as a gracious hostess and entertained the frequent guests to Mount Vernon who visited the former President.

On Washington’s birthday in 1799, Nelly married Washington’s private secretary, Lawrence Lewis. They spent several months on an extended honeymoon, visiting friends and family across the country. On their return to Mount Vernon, she was pregnant and late that year gave birth to a daughter. A short few weeks later, on December 14, General Washington was taken seriously ill and died.

Clearly, Nelly was someone who knew the private and public life of her “father” very well. Therefore, Jared Sparks, in searching for information on Washington’s religious habits, dispatched a letter to Nelly, asking if she knew for sure whether George Washington indeed was a Christian. Within a week, she had replied to Sparks, and Sparks included her letter in Volume XII of Washington’s writings in the lengthy section on Washington’s religious habits. Of that specific letter, Jared Sparks explained:

I shall here insert a letter on this subject, written to me by a lady who lived twenty years in Washington’s family and who was his adopted daughter, and the granddaughter of Mrs. Washington. The testimony it affords, and the hints it contains respecting the domestic habits of Washington, are interesting and valuable.”

Woodlawn, 26 February, 1833.

Sir,

I received your favor of the 20th instant last evening, and hasten to give you the information, which you desire.

Truro [Episcopal] Parish is the one in which Mount Vernon, Pohick Church [the church where George Washington served as a vestryman], and Woodlawn [the home of Nelly and Lawrence Lewis] are situated. Fairfax Parish is now Alexandria. Before the Federal District was ceded to Congress, Alexandria was in Fairfax County. General Washington had a pew in Pohick Church, and one in Christ Church at Alexandria. He was very instrumental in establishing Pohick Church, and I believe subscribed [supported and contributed to] largely. His pew was near the pulpit. I have a perfect recollection of being there, before his election to the presidency, with him and my grandmother. It was a beautiful church, and had a large, respectable, and wealthy congregation, who were regular attendants.

He attended the church at Alexandria when the weather and roads permitted a ride of ten miles [a one-way journey of 2-3 hours by horse or carriage]. In New York and Philadelphia he never omitted attendance at church in the morning, unless detained by indisposition [sickness]. The afternoon was spent in his own room at home; the evening with his family, and without company. Sometimes an old and intimate friend called to see us for an hour or two; but visiting and visitors were prohibited for that day [Sunday]. No one in church attended to the services with more reverential respect. My grandmother, who was eminently pious, never deviated from her early habits. She always knelt. The General, as was then the custom, stood during the devotional parts of the service. On communion Sundays, he left the church with me, after the blessing, and returned home, and we sent the carriage back for my grandmother.

It was his custom to retire to his library at nine or ten o’clock where he remained an hour before he went to his chamber. He always rose before the sun and remained in his library until called to breakfast. I never witnessed his private devotions. I never inquired about them. I should have thought it the greatest heresy to doubt his firm belief in Christianity. His life, his writings, prove that he was a Christian. He was not one of those who act or pray, “that they may be seen of men” [Matthew 6:5]. He communed with his God in secret [Matthew 6:6].

My mother [Eleanor Calvert-Lewis] resided two years at Mount Vernon after her marriage [in 1774] with John Parke Custis, the only son of Mrs. Washington. I have heard her say that General Washington always received the sacrament with my grandmother before the revolution. When my aunt, Miss Custis [Martha’s daughter] died suddenly at Mount Vernon, before they could realize the event [before they understood she was dead], he [General Washington] knelt by her and prayed most fervently, most affectingly, for her recovery. Of this I was assured by Judge [Bushrod] Washington’s mother and other witnesses.

He was a silent, thoughtful man. He spoke little generally; never of himself. I never heard him relate a single act of his life during the war. I have often seen him perfectly abstracted, his lips moving, but no sound was perceptible. I have sometimes made him laugh most heartily from sympathy with my joyous and extravagant spirits. I was, probably, one of the last persons on earth to whom he would have addressed serious conversation, particularly when he knew that I had the most perfect model of female excellence [Martha Washington] ever with me as my monitress, who acted the part of a tender and devoted parent, loving me as only a mother can love, and never extenuating [tolerating] or approving in me what she disapproved of others. She never omitted her private devotions, or her public duties; and she and her husband were so perfectly united and happy that he must have been a Christian. She had no doubts, no fears for him. After forty years of devoted affection and uninterrupted happiness, she resigned him without a murmur into the arms of his Savior and his God, with the assured hope of his eternal felicity [happiness in Heaven]. Is it necessary that any one should certify, “General Washington avowed himself to me a believer in Christianity?” As well may we question his patriotism, his heroic, disinterested devotion to his country. His mottos were, “Deeds, not Words”; and, “For God and my Country.”

With sentiments of esteem,

I am, Nelly Custis-Lewis

George Washington’s adopted daughter, having spent twenty years of her life in his presence, declared that one might as well question Washington’s patriotism as question his Christianity. Certainly, no one questions his patriotism; so is it not rather ridiculous to question his Christianity? George Washington was a devout Episcopalian; and although as an Episcopalian he would not be classified as an outspoken and extrovert “evangelical” Founder as were Founding Fathers like Benjamin Rush, Roger Sherman, and Thomas McKean, nevertheless, being an Episcopalian makes George Washington no less of a Christian. Yet for the current revisionists who have made it their goal to assert that America was founded as a secular nation by secular individuals and that the only hope for America’s longevity rests in her continued secularism, George Washington’s faith must be sacrificed on the altar of their secularist agenda.

For much more on George Washington and the evidences of his strong faith, examine the following sources:

- George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, Jared Sparks, editor (Boston: Ferdinand Andrews, Publisher, 1838), Vol. XII, pp. 399-411.

- George Washington, The Religious Opinions of Washington, E. C. M’Guire, editor (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1836).

- William Johnson, George Washington The Christian (1917).

- William Jackson Johnstone, How Washington Prayed (New York: The Abingdon Press, 1932).

- The Messages and Papers of the Presidents, James D. Richardson, editor (Published by the Authority of Congress, 1899), Vol. I, pp. 51-57 (1789), 64 (1789), 213-224 (1796), etc.

- George Washington, Address of George Washington, President of the United States, Late Commander in Chief of the American Army, to the People of the United States, Preparatory to his Declination (Baltimore: George & Henry S. Keatinge, 1796), pp. 22-23.

- George Washington, The Maxims of Washington (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1855).

* Originally Posted: Dec. 31, 2016.

America’s first attempt at a national governing document was in 1777 with the Articles of Confederation.

America’s first attempt at a national governing document was in 1777 with the Articles of Confederation. James Madison agreed:

James Madison agreed: Many delegates involved with writing the Constitution were trained in theology or ministry,

Many delegates involved with writing the Constitution were trained in theology or ministry,

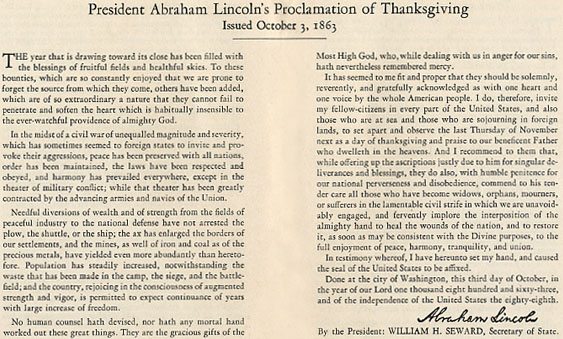

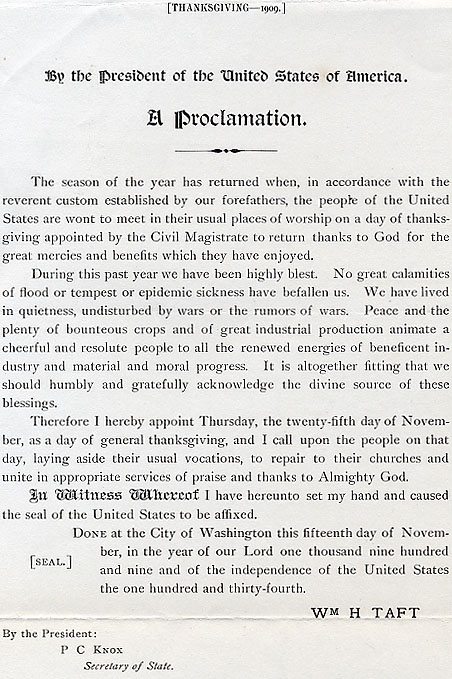

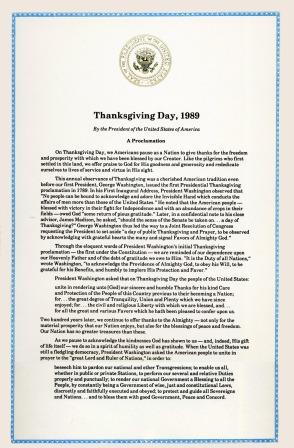

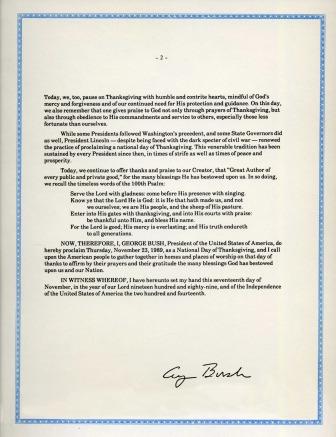

Whereas it is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor; and whereas both Houses of Congress have, by their joint committee, requested me “to recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.”

Whereas it is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor; and whereas both Houses of Congress have, by their joint committee, requested me “to recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.”