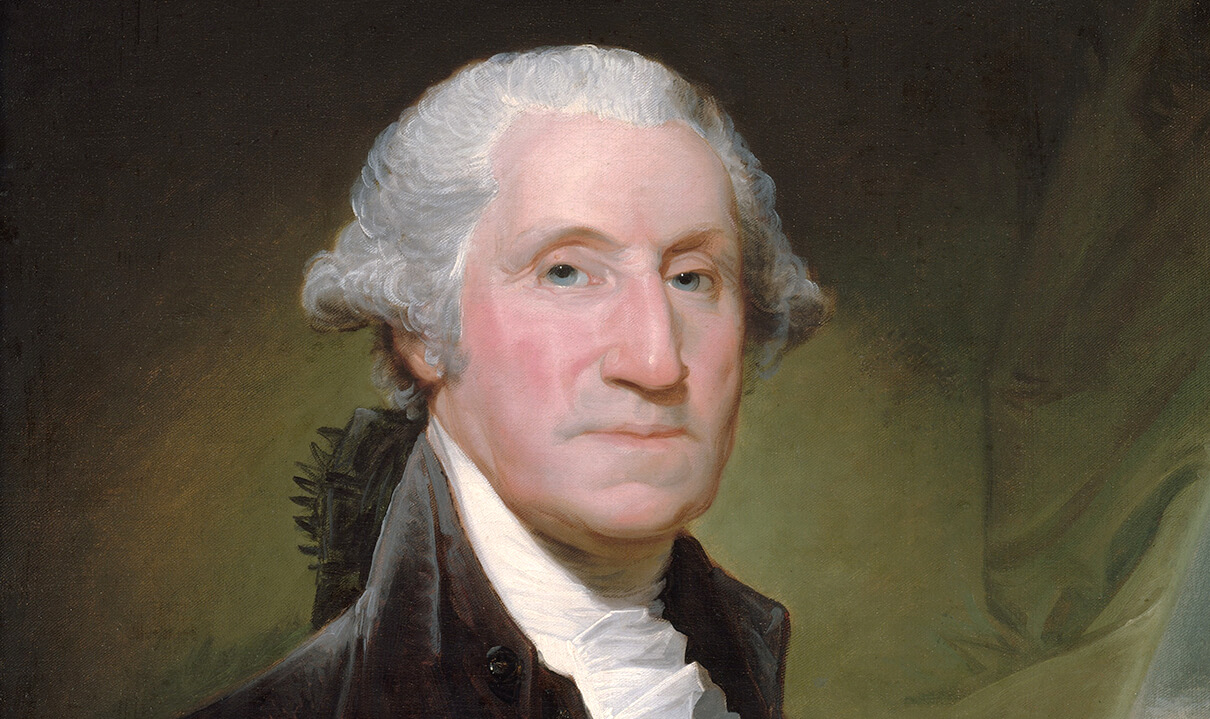

Samuel Thayer Spear (1812-1891) graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1833. He was pastor of the 2nd Presbyterian Church of Lansingburg, NY (1836-1843) and the South Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn, NY (1843-1871). The following sermon was preached on the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 by Spear.

LAW-ABIDING CONSCIENCE.

AND THE

HIGHER LAW CONSCIENCE;

WITH

Remarks on the Fugitive Slave Question.

A SERMON,

PREACHED IN THE SOUTH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, BROOKLYN,

DEC. 12, 1850,

BY REV. SAMUEL T. SPEAR.

“Then Peter and the other Apostles answered and said, We ought to obey God rather than men.”—Acts v, 29.

Using these Scriptures as a basis, I design to examine a great moral question, that is now agitating and somewhat distracting the American people. My object is not denunciation, or to promote unhealthy excitement here or elsewhere. I believe in the supremacy of truth, and in the safety as well as wisdom of temperate and Christian discussion. If I did not, I should not enter upon the task now proposed. I ask no man to accept the views I shall offer, except as they conform to his sense of truth. They will represent my sense.

One of our Senators in Congress employed the phrase “Higher Law,” in such connections as to call forth much rebuke at the time, and expose him to the censure of a portion of his constituents. Let us hear the passage as it originally fell from his lips:

“The Constitution regulates our stewardship; the Constitution devotes the domain to union, to justice, to defense, to welfare, and to liberty. But there is a higher law than the Constitution, which regulates our authority over the domain, and devotes it to the same noble purposes. The territory is a part—no inconsiderable part—of the common heritage of mankind, bestowed upon them by the Creator of the universe. We are his stewards, and must so discharge our trust as to secure, in the highest attainable degree, their happiness.”

This is the passage; and I confess that I see in it no heresy, political or moral, no repudiation of man or God. The honorable Senator affirms a coincidence, and not a discrepancy, between the Constitution and the Higher Law; and surely no man in his senses ought to complain of such an opinion.

Innocent and harmless as is this passage, still, in connection with other causes, it has had the effect of setting before the American people a great politico-moral question, in respect to which I deem it a duty to express an opinion. I am a lover of my country, without being an approver of its wrongs. I believe it, on the whole, the best country on the earth, made such mainly by its civil and religious institutions. Nothing which concerns its welfare is indifferent to my heart. Hence, I ask the privilege of speaking with freedom and honesty; the one, a chartered right, and the other, a solemn duty. To me it seems proper that the pulpit should be heard. The crisis demands it.

No one who has listened attentively to the conversation of others, or watched the public press for some months past, can fail to have perceived the existence of at least two classes of consciences: the one, a LAW-ABIDING conscience—the other, a HIGHER LAW conscience; in some hands, each repudiating and violently denouncing the other. I respect both, without relishing the extravagance, and much less the passions of either. I belong to both parties, with such qualifications of my adherence as will be unfolded in this Sermon. In each I see some truth—not the whole in either. The truth I see, I hold, and mean on this occasion to assert, as plainly and as kindly as I may be able. I do this as a matter of duty to you, being related to you as a pastor. I do it as an humble tribute of honest service to my country. Let me invoke your attention and candor.

Our present work will be to set before you the two consciences—the law abiding and the higher law conscience; each qualifying the other, and both moving in their proper sphere. In this it will be my earnest desire to guard your minds and hearts, and not less my own, against two fanaticisms: one, the fanaticism that repudiates civil government; the other, the fanaticism that virtually repudiates God, and the eternal distinction between right and wrong. I wish to get at the simple truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. How far I succeed in this, will be for you to judge, after hearing me.

First, the LAW-ABIDING CONSCIENCE.

Civil law undertakes to prescribe and enforce some of the social duties of men. This is made necessary mainly by our depravity. Law is the creature of some organized government, addressing its commands to the subject, and threatening its penalty in case of disobedience. It is not mere advice; it is clothed with authority, and is properly accompanied with the right of self-vindication in coercion and punishment. The supremacy of law consists in its maintenance—in the due and faithful administration of its principles by its authorized agents, and in its power to control and govern the practice of the subject. This supremacy is the grand doctrine asserted by the law-abiding conscience. This conscience affirms the sanctity and authority of law, and by consequence, the obligation of obedience. It sets forth a moral rule, namely, that obedience to civil law is a religious duty. It spends its whole strength in affirming this duty. Let the simple question be, shall a law enacted by the existing civil authority, or in process of execution, be respected and observed, treated as a law by all parties whom it involves? I say, let this be the question; and a law-abiding conscience always answers in the affirmative.

Such is the general doctrine of this conscience; and as a single particular to be placed in the great temple of truth, it is unquestionably correct. Perhaps I need not argue so plain a point. Lest, however, I might seem to undervalue it in another stage of this discussion, I will pause a moment on the question of its truth.

It is manifestly a Scripture doctrine. This you see in one portion of our text. The “higher powers” spoken of by Paul, were the civil authorities of the Roman empire. He declares civil government to be of Divine appointment, for the proper regulation of human conduct, for the protection of society by the punishment of crime. He exhorts Christians to be subject to the “higher powers,” not only on account of the penalty, but also as a matter of duty. It was not his purpose to assert the Divine right of Kings, but of civil government, as such, and the duty of the subject. There was special pertinence as well as wisdom in this instruction. The “higher powers” referred to were Heathen powers; and there was no little danger that the disciples of Christ, mistaking the proper sphere of their Christian liberty, might come in conflict with them—might take up the idea that, being Christians, they owed no allegiance to a Heathen magistracy. Paul, as a judicious counselor and faithful apostle, endeavors to guard them against so fatal a mistake. Peter took the same course. “Submit yourselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake; whether it be to the King, as supreme; or unto governors, as unto them that are sent by him for the punishment of evil-doers, and for the praise of them that do well.” The doctrine of sedition, treason, rebellion, and tumultuous resistance, in civil society, is not inculcated in the teaching or the example of the apostles, or in those of Christ himself. This is a perfectly clear point. Hence, we say, the Scriptures give their sanction to the great principle affirmed by the law-abiding conscience.

Common sense and good citizenship must take the same ground-Society in the country or the town, and especially the latter, cannot exist a moment, with any safety, if this principle is practically discarded. Destroy the restraints and retributions of civil government, and leave every man to do as he pleases, and you have so much liberty that you have none at all;–you are out at sea in a tremendous gale, without a rudder or chart. No man would stay in such a community any longer than it would take him to get out of it. Men cannot live together without the agency of government. Nothing is worse than pure anarchy. It is the most cruel and dangerous of all tyrants. Governments, as the agent in creating and executing law, must have somewhere a sustaining power, else it is no government: it can do nothing, discharge none of the duties of government—neither protect the innocent nor punish the guilty. This sustaining power lies in the strong arms, the bones and muscles of men, whose services may be legally brought into action, to enforce the civil mandate. Without this, government rests on nothing—has no practicable character—is a mere idea. If every law it enacts is to be resisted and put down by popular violence—if every effort to execute the law is to be treated in the same way—if this is the state of things in the community, then there is no government of law in that community; society is in the state of chaos. Hence, if men wish to live under law, they must support the supremacy of law. This doctrine must have some practical and efficient shape, or they cannot live together as a civil community. Somebody must have a law-abiding conscience, or government has no sustaining power. Whatever may be the inconveniences of this doctrine, at times, or even its incidental injustice, still the consequences of its practical repudiation would be far more serious. It is a wholesome principle, pre-eminently useful, blessing a vast many more than it harms, averting incalculable evils. I am conscientiously its advocate. It commends itself to my common sense, as I have no doubt it does to that of the hearer.

This doctrine ought to be peculiarly welcome and sacred to the American bosom. Our Government, both State and Federal, is based on the representative principle. We have no law-makers or law-agents, that are born such. We make them after they are born, not as kings, but men. The powers they possess the people bestow in a legal way; and if they do not faithfully perform their duty so as correctly to represent the public will, there is always at hand a peaceful and law-abiding remedy. We can discuss and even denounce a law in this country. It is not treason to call in question its equity. We can peaceably meet in large or small assemblies, and by resolutions express an opinion. We can petition Government for a redress of grievances. Through the ballot-box the people have a perfect control over the laws under which they live. No law can stand any length of time that is opposed to the public will. This fact seals its doom. Now, a people possessing such privileges clearly have no occasion for attacking legal injustice, except in the legal way—no occasion for anything like popular violence. They can correct the abuses of Government without a mob. Politicians and office-seekers are very fond of being where the people are; they generally true to think with the majority. Hence, it is far better to wait till the public mind can be enlightened, than to attempt the cure of an evil by producing a greater one. Cry out against it as long and as loud as you please; write against it; speak against it; pray against it; vote against it; but be sure to stop here; never lend your sanction to tumultuous or illegal resistance. This must be the doctrine of the American citizen; since our civil institutions are not only wholly drawn from the people, but have no sustaining power except in their law-abiding spirit. I can think of no occasion likely to occur, in which I would be the advocate of any other course. If by popular tumults you may repudiate law on one subject, you may on another. The principle is full of its dangers, especially so in a Republic. It unsettles the very foundation of civil society. It can have no place in the convictions or sympathies of the virtuous and enlightened citizen. This great community of freemen must go according to law, or they must go to ruin. I speak strongly on this point; for I have always felt strongly; and I do not feel less so now. The civil authorities must put down mobs, immaterial what the issue be; and the people must sustain them.

So much I offer for your consideration in favor of the law-abiding conscience. The grand principle it affirms, I hold to be a sacred truth.

The charm of this idea, however, does not lie in its application to an unjust and cruel law, but in the fact that it is vital to the stability and safety of civil society. Here is its excellence—here the reasons which commend it to the good sense and patriotic feelings of men. The man who silences his moral sense in respect to injustice and wrong by pleading the supremacy of law, who not only abstains from all illegal resistance, but also declines the use of lawful measures to correct unjust enactments, whose whole conscience is summed up in the single sentence, “I believe in the supremacy of the laws,” with whom this is the while idea, who refuses to apply his conscience to the moral nature of the law, and his energies, if need be, to a constitutional remedy; that man, in my judgment, does no justice to himself or his legal privileges, and perhaps not to his moral duties. He shuts up his eyes as a moral being, and parrot-like shouts the supremacy of the law, and shouts nothing else. He misapplies the doctrine, forgetting his duties. His example need only be imitated to make a bad law a permanent fixture. Between him and me there is no debate as to the supremacy of law while it exists; but neither of us should cancel our obligation to seek the correction of legal injustice by a mere glorification on the ground of our common faith. He says to me, “I am a law-abiding man.” Very well; I am glad he is; so am I. I am also a law-correcting man by such measures as are lawful. I do not go for the perpetuity of unjust laws any longer than is necessary to procure their modification or repeal. My duty to seek this is perfectly consistent with all due respect for law while it exists.

There is another perversion of this doctrine, against which the citizen ought carefully to guard his mind. He should never associate with it the practical assumption that law is beyond the reach of moral inquiry, that law is the end of the chapter, as infallible as it is authoritative. This is a very dangerous, and it may be a very immoral course. Law proceeds from imperfect, and sometimes very wicked men. It has often legalized the greatest wrongs, legislated the grossest crime into civil virtue, and the purest virtue into crime. Hence it will not do in maintaining its supremacy, also to maintain its moral infallibility. The latter doctrine is properly no part of the former, and in the bosom of the citizen should be kept distinct from it. The king can do no wrong—can require no wrong; law is always right in morals. What is this? Political popery—the doctrine of despotism, unworthy of a home in the breast of a freeman. In the American theory of civil society, law claims no such attribute. It confesses its own fallibility in the provision for amendment or repeal. Hence the question whether it is right or wrong, whether it ought to be continued or not, is not to be ignored or repudiated by declaring its supremacy. I hold to the supremacy of no human laws in the sense of their infallibility. They may contradict God’s law; they may violate the plainest dictates of natural justice; and whether they do or not, it is my privilege and duty, and equally yours, to have an opinion. If I think they do, the voice of my reason and conscience is not answered by my faith in the supremacy of law. I then believe that the laws are bad, in themselves morally vicious, though not less really laws, and that all proper means should be used for their speedy amendment. We must hold on to this doctrine, else our law-makers will become Popes, and the people lose all the rights of private conscience. If there is danger in taking too much from Government, there is also danger in conceding too much to it. One thing I never can concede; I never can say that a Government is doing right, when I think it is doing wrong.

There is another circumstance that ought always to be taken into account, when we speak of the supremacy of law, especially in a Republic. Law upon its merits, and not simply its authority, ought to be addressed to the good sense and moral feelings of the community where it is to be executed. It has no power to change the convictions of men in respect to the subjects to which it refers. It cannot make a freeman think that black is white, or white is black. I cannot subvert the Christian ethics of a community, even by its supremacy. Hence, it must not assume that the subject is a brute, and that he will blindly swallow anything and call it sweet that comes to him with a legislative endorsement. Law, in a free country, has no such charm. You must go to the scenes of despotism and popular ignorance, in order to realize this result. In this land a law against the sense of the people, be that sense a prejudice or a just sense, is always the lawgiver’s folly. It comes into existence with the sentence of death upon it; and though it is a law, still on its merits it is not welcome to the subject, and must ultimately be repealed or modified. This is the fate of all laws that upon their trial are found to misrepresent the public will. They are born to die. They must run a short race. Their supremacy cannot save them from the ordeal and the doom of the press and the ballot-box. It is well that it is so; for in this way we rectify legal mistakes in the peaceful and orderly method, without insurrections or mobs.

Secondly, the HIGHER LAW CONSCIENCE.

The cardinal propositions affirmed by this conscience, are these:–First, that there is a God: Secondly, that this God is the moral governor of the universe: Thirdly, that every rational creature is directly a subject of his government: Fourthly, that God’s will, when ascertained, is in all possible circumstances the supreme rule of duty: and, finally, that every moral creature is by himself and for himself bound to know the Divine will, and, when knowing it, never to deviate from it. These are the great doctrines of this conscience. To the vision of piety their statement is their proof. Deny them, and you overturn or make morally impractible the government of God; you release man from his allegiance to his Maker, and upset all religious systems, that of the Bible not excepted. They are not to be denied, but admitted, be the consequences what they may. They are true, or nothing is true. If they are not true, duty is a fiction—moral conscientiousness, a whim—responsibility to our Maker, a delusion; and even God himself is nothing in respect to the duties of men. I hold these truths; hence I hold the elements of the Higher Law Conscience. I confess myself to be the subject of such a conscience.

In order to advance to a just application of these principles, we must pause a moment on a question of fact. God does not administer his moral government over men simply and wholly through the agency of civil government. If he did, the sum of all his commands would be obedience to “the powers that be;” they would be taken as the authoritative exponents of all the statutes of the Eternal Throne; and the subject would be referred to them in all cases, to know the will of God. Were this the fact, there could be no conflict between Divine and human authority; the former would always be identified with the latter; God’s WHOLE will being always found in man’s law. This is not the case. It is our duty to pray, to clothe the naked and feed the hungry, to do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with our God. Indeed, a great many duties besides subjection to the civil magistracy, are taught by the light of nature, and equally in the Bible. Hence, there may be a conflict between the requirements of the civil authorities and those of God. He is not so identified with them, neither does he so guide their action, as to make the result impossible. The event has often occurred; that is, man has commanded one thing, and God, the opposite, making obedience to both a natural impossibility. This fact is not to be put out of sight by the clamors of a mere law-mania. It is a fact. While it is true that there is no higher law than the law of God, which requires obedience to civil government, it is equally true that this is not the whole of God’s law. He has given other laws as well as this; and with these civil government may come in direct conflict. Does God require the subject to obey man, when the latter requires him to disobey God? This is a point not fairly and properly met by some, who have recently published their views on this subject. Bear these observations in mind. We shall have occasion for their use in another stage of this inquiry.

There are two distinct applications of the great principles set forth by the Higher Law Conscience, in regard to each of which I will express an opinion with its reasons.

1. The first refers to the powers that be, considered as the creators or executors of law. Are there any rules of morality for governments, for nations, as such; or do they create their own morality at option? Are law-agents responsible to God for what they do, and equally with the citizen subject bound by the principles of the Higher Law? We hold that they are. Our President, in his recent message, has uttered this sentiment. He says, “The great law of morality ought to have a national, as well as a personal and individual application.” Whatever has a moral nature as right or wrong, consonant or otherwise with the will of God, as disclosed in his Word or in the sacred rights of humanity, before legislation and compacts touch it, retains that nature. Morality is a fixture in God’s universe, neither made nor unmade by government, alike the legitimate sovereign of nations, kings and subjects. It is antecedent to all constitutions and laws—is the rule by which we try their equity. Were it otherwise, there could be no retribution for national crimes; government might become a conspiracy of unpunished assassins; and the agents of enormous wickedness might, by their official character, flee from the moral jurisdiction of the Divine law. God holds all men responsible to his rule of right, whether they are associated as a nation or exist in the state of nature, whether they are citizens and subjects, or are trusted with the duties and powers of the civil magistracy. They cannot innocently act in conflict with the Higher Law.

Assuming your assent to this view, let me remark that there are two practical questions which claim an answer.

Suppose that a people are adopting a Constitution for government, or that law-makers are giving birth to legal enactments, what in this stage of affairs is the relation of the Higher Law? Plainly, it requires them to establish justice, protect right, and provide for the punishment of wrong, to legislate not against God, but in coincidence with his authority. They ought to produce just and impartial laws. This is the mission and proper aim of civil government. It is not to be the instrument of despotism and oppression, but of justice and safety. The preamble of our national Constitution sets forth the true doctrine on this subject. “We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” This is a sound creed.

Suppose, again, government to be established, and that the execution of its will has passed into the hands of the duly authorized agents of law, what are they to do? I answer; execute that will as it lies on the statute-book, or in the fundamental law of the land. Suppose, however, that the laws themselves, one or more, are so morally vicious, that the agents cannot execute them without sinning against the Higher Law; what then? I answer, this being their view, they must either execute the laws or resign their trust. They must either fulfill the oath of office, or vacate it. There is no other alternative. On any other principle, civil society would sink to ruin in the hands of its executive agents. A man who holds office contrary to his conscience, must not please conscience against its duties. Which shall they do? Shall they keep their oath and do wrong, or vacate the office and do right? I answer, without one moment’s hesitation—the latter. They are wanting in moral honesty unless they take this course. A military officer, for example, who is commanded to fight, but who believes fighting to be sinful, must either fight or send in his protest and resignation. The view he takes of war in general, or of a particular war, makes the latter his only possible course. He must not hold the fighting commission, and yet refuse to fight at the legal call of his country. Neither must he fight against the mandate of God. Hence he must resign.

These are my views in respect to the application of the Higher Law to the powers that be, whether you consider them as a nation establishing the principles and rules of government, or as the personal agents of that government. Both are amenable to the God of truth; and the Higher Law ought to be the ultimate standard of both. Neither has a right by any legal process to trespass upon the supreme rule of right. It will be sin in either.

2. Let us now, secondly, look at the application of the Higher Law to the citizen-subject. Of course it presents no difficulties, where Divine and human laws are in harmony—where morality and legislation wear the same features. It is their conflict, and this only, that makes an occasion to test the authority of each. This conflict may come up in one or the other of the following practical shapes:

The first is where government, in the judgment of the people, has become so unjust and oppressive, as to be utterly destructive of its legitimate and proper ends. In such a crisis, the people have the inherent right of revolution, by which I mean the total subversion of the government that exists, and the erection of a new one. Tyranny and despotism have not an eternal license. The duty of obedience has a limit somewhere; when a suffering people may say to legal tyrants, “Be gone!—We can dispense with your services. We cannot tolerate you any longer.” The undertaking is always an awful one. It is open rebellion. It is to be the last resort of an oppressed people. It is never expedient except when there is a fair hope of success; yet, when the crisis comes for it, then the act is not treason, but a legitimate revolution. Government is not such an ordinance of God, that it may not write its own doom. The right, however, of actual revolution never belongs to a minority, but always to the majority. While the many say, let government stand as it is, the few must acquiesce, and bear its grievances. They have no other alternative.

This assertion of the revolutionary right will not, I trust, sound strangely in American ears. It is the doctrine of the Declaration of Independence. This government is founded upon the inherent right of revolution. Great Britain drove our fathers to its exercise; and had she triumphed, would have hung them as traitors, though we believe they were patriots—lovers of their country and their kind. No American surely, will repudiate this fundamental right of the people. The rights of government are the gift of God to the PEOPLE, and by the people to the king. His powers exist by their consent, and terminate with their dissent. Who doubts whether the collected people of Europe have a right to dethrone every monarch, and sweep away the whole system of aristocracy, that of the Pope not excepted, and establish free government? Austria thought Hungary to be guilty of treason, and butchered her heroes to satiate her vengeance. We think her to have been glorious in her struggle—not less so in her fall. The name of Kossuth has a charm, as the embodiment of the revolutionary right. The Pope thought the Italians seditious. We honor them, and despise the infamous course of the French nation. Charles I. thought Cromwell and the Roundheads to be a pack of traitors. Posterity regards them as the apostles of civil liberty. Forget not, that nearly all the liberty of the world has been procured by the revolutionary right; its exercise being actually put forth, or so menaced as to make kings tremble. Generally, despotism cannot be reasoned into justice. For a rule, the people have been compelled to frighten it or destroy it.

Thus, on this point, my doctrine, in a word, is this:–In all those cases where revolution is really a necessary expedient, being the only resource of an outraged people, resistance to tyrants is obedience to God. Here the Higher Law of right intervenes, and justly sweeps away the powers that be, in order to make better ones. I grant you that it is open rebellion against the existing government; and that it must be crushed, or government must be overturned by it. The ground on which I defend it, is this:–Passive subjection to legal tyranny has a limit; and at this limit “The Higher Powers” lose all their moral authority, giving place to those that shall be the product of a revolution. This doctrine I hold as a question of morality, and not merely of strength. Hence, I qualify the doctrine which asserts the supremacy of law, by the revolutionary right. I do not believe, that revolution upon a just and sufficient occasion is a crime. I hold it to be the virtue and right of the people. I must, however, add that the experiment is always a terrible one—the last resort; and that it should be well considered before undertaken. In a Republic such as ours, I do not see how such a crisis can ever arrive. It cannot, unless our civil officers should enter upon a career of despotism, of which there is not the faintest prospect. A people living under a government of chartered rights and limited powers, whose action they control, surely have no occasion to resort to the Higher Law of revolution.

The other form of conflict with government on the part of the citizen, is where not revolution, but obedience to God with non-resistance to man, is both his right and duty. Let me carefully state my ground on this point, and ask you to receive it as I state it.

Here are three parties. God is one; the subject is the second; and the civil authorities, the third. Between the first and the third there is a conflict, the last forbidding what the first requires, or requiring what the first forbids—man by law setting aside the imperative duties or prohibitions of God’s Word—man, for example, legally requiring me to abjure Christianity, or forbidding me to pray, or commanding me to worship an idol—man, in short, rendering illegal and criminal the duties that God imposes. This is the case supposed; and it is not merely a hypothetical case. It has often occurred, and it may again. Now what shall the subject do in the premises? I answer: first, he must be clear that the supposed case is a real one—a point in regard to which so far as he himself is concerned, he is the sole judge, and yet a point where he may not innocently be mistaken and act the part of a fool; and secondly, if in his view the conflict be real, then he must obey God rather than men, and as a martyr meekly suffer the consequences. I do not see how there can be any question as to the correctness of this answer. God’s law is certainly higher than man’s. The apostles acted upon this principle: Daniel did; so did the three men that were cast into the fiery furnace; and so have all the Christian martyrs, nearly everyone of them being slain not by mobs, but by legal enactment. They had not the seditious spirit; they were pious, willing to do right and suffer for it. The most eminent examples of Christian virtue have been produced on this theatre. Obedience to God even though it conflict with the laws of man, is as distinctly a doctrine of the Bible as any other found in that book. Some are disposed to overlook this point, to shove it out of sight. They seem to be afraid of it. I am not afraid of it; to me it is a part of the great system of truth. Every man believes it, whether he asserts it or not. I can suppose forty cases, in which every one of you would affirm its truth; and you will mark, if it is true anywhere, then the principle is yielded, and the only question that remains, is its application, in regard to which we might differ though perfectly agreeing as to the principle.

But I must not stop here, for I am anxious to give you an impartial view of the whole truth. What shall the civil authorities do, when the subject disobeys the law of the land on the ground of the Higher Law? I answer; inflict upon him its penalty. They have no other course. They can never assume what he alleges, that there is any conflict between the law of the land and the law of God. They can never make his conscience the rule of penal retribution at the hands of government. They must always assume that the law is right, and that he is wrong, and is therefore to be treated as a criminal. Without this moral consciousness in fact, government is a gross and detestable hypocrite. It can never surrender its ideas of what is right, and yet possess authority. This would be a confession of judgment against itself, and disarm it of all its power. It would leave every man to decide for himself not simply the question of his personal duty, but also in what cases law should punish him; that is, his conscience would be the law of the land, and the criminal would be his own judge. This would be giving him the rights of the subject, and at the same time the prerogatives of the sovereign. Now civil society can never concede this to the conscience of the private citizen. It would be tantamount to the destruction of all law. The subject violates the law for the sake of obeying God, knowing when he does so that government will deem him mistaken and punish him accordingly. He makes his choice between the precept and the penalty; and chooses the latter—that is, he chooses suffering in his view for righteousness sake. This is a fair transaction on the part of the subject towards the sovereign; and it may be a very virtuous one.

But which, it may be asked, is right? The subject says, “I am, I correctly expound the Higher Law.” The powers that be, say, “We are, we understand justice and right.” In respect to their action they are both right; each must follow their respective sense of duty. But which is right really—that is, has the right sense of duty? Who is to decide this question? This must be left to posterity and to God. Every professed martyr virtually appeals to posterity and to God, to review his case, and settle the question whether he was a martyr or a fool, a good man or a bad one. A great many who have died as criminals, are on the records of glorious fame. The judgment of posterity has reversed that of the age, in which they suffered. And then God has instituted a tribunal based wholly on the principles of the Higher Law, for the trial of all these affecting cases. At this tribunal God Himself will give a final and impartial decision, canvassing the responsibilities, beliefs and motives of both parties.

Thus, my brethren, without passion or prejudice, I have endeavored to give you my sober and earnest views in respect to the question, that was started in the outset. In this I have consulted the creed of no party, the preferences of no class of men, but the best light of my own reason, guided by the word of God. Both consciences, the law-abiding and the Higher Law conscience, have a place in a correct system of Christian Ethics. The first is supreme except where qualified by the second. To repudiate this, is treason to God for the sake of loyalty to man. I advocate both principles, assigning to each its proper sphere. I want to be a good citizen in the land that gave me birth, and whose laws are my protection. I want more to be a good citizen under the government of God. In respect to both I have a conscience. What that conscience is, has been explained.

Many of the views recently expressed on this general subject, have failed to satisfy my mind. They lack what Locke the philosopher, used to call “the round-about view.” Some of them are greatly wanting in prudence; others, exceedingly doubtful in morality; others, positively immoral. Some have so urged the Higher Law doctrine, as virtually to throw off all the obligations due to civil government, and advance very near if not quite, to open treason. They would almost dissolve civil society, or at least stop its operations, by the force of their own conscience. Others have rushed into the extreme, pressing the duty of obedience to the civil authorities as if it had no limit, except in the rare cases of revolution.” We confess no little surprise, that even ministers of Christ should preach this as the morality of the Bible. What will they do with the case of Daniel, of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, of Peter and John, of Paul himself, and the long line of Christian martyrs? Do they mean to repudiate the allegiance to God evinced by these men, though in conflict with the laws of man? This is really a new doctrine, and as dangerous as it is new. Let it be proved that human government is such an ordinance of God, that all its decrees are to be taken as the infallible expression of His will; and then, we shall have the “Divine right of kings. The citizen will then have little else to do but seek God’s whole will in the laws of the land. This is the very worst kind of Toryism—better suited to the dark ages than to the 19th Century. It makes civil government to be what God and truth never made it. And still others have failed to distinguish between the declinature to obey an immoral mandate of civil government, and a positive forcible resistance to the execution of its laws—things morally as wide apart as the poles. Men, even great men, when excited or unduly captivated with one idea, run into extremes. They shout a single thought, true in its proper sphere, in a way to make practically a false impression, and inculcate heresy. I have sought to shun all these extremes, and speak to you as nearly as possible, in the language of simple truth.

My first opinion is, that it is best for all men to keep cool, to separate between their passions and their moral convictions. Men of equal respectability do not see alike. The Northern mind is confessedly in an unsettled state; and I can see nothing to be gained by a crusade of denunciation. Some, in their zeal to stop “agitation,” almost repudiate the right of free discussion, except for themselves. This is as bad in policy, as it is questionable in principle. In a free country it always costs more to gag a man than it does to hear him. Violent and passionate denunciation frightens nobody in this land. Hence, I think it best to keep cool. I mean for one to have my own opinions, and yet I mean to know what I say, and what I do. I think this becomes every man.

In the next place, there are some facts to be looked at as facts. It is a fact, that the Constitution of the United States is the fundamental civil law of this land. It is also a fact, that this Constitution does provide for the capture of fugitive slaves, and their return to Southern bondage. Let me give you the words:–“No person held to service or labor in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor; but shall be delivered up, on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.” 1 The term slave is not used, but the thing was meant. The circumstances, too, in which the agreement was made, were not those of the present time; yet the agreement has not, by any legal process, been canceled. It still remains on the national charter—the contradiction of all its other principles. It is also a fact, that a very large number of slaves have fled from their masters, and taken refuge in the free States. Some of them have become members of Northern churches. Many of them have entered into the sacred relations of domestic life—have become fathers and mothers; and probably some of them are even citizens. Every one of them is legally liable to be captured and returned to slavery. They will be so, till they die, or the Constitution is altered, or they flee to another land. I pity them with all my heart. Their condition is a sad one. It is an awful spectacle in a free country.

These, my brethren, are facts. It does no good to deny them, or to reason as if they were not facts. What then shall be done in view of such facts? I can answer this question only for myself, as an individual.

If I were a Southern man, and a friend of the Union—as I am not the former, but am most cordially the latter—I should, with my present views, say some things to my fellow-citizens at the South. This would be the substance of my speech:–As a matter of prudence, patriotism, and wisdom, I would advise them not to insist on the constitutional right secured by this provision. The argument I would use in support of this advice, is various. I would tell South Carolina, that she has on her own statute-book, laws in respect to colored citizens of other States, that expressly nullify the national Constitution; and that the wise way for her would be to keep quiet. I would remind the entire South, that in three instances, namely, in the purchase of Louisiana, of Florida, and the annexation of Texas, the national government exceeded its constitutional powers for the benefit of slavery: that although the nation has acquiesced in these acts, still there is not one syllable to show their constitutionality. I would also exhort the South to remember, that when this provision was admitted, it was not understood to be permanent, slavery, then, being supposed to be on its death-bed. I would point them to the fact, that they have never been able to recover a sufficient number of these fugitives, and in the nature of things never will be, to make the experiment one of any great practical value to them. The slave, once at the North, has facilities for escape that not the most stringent laws can ever supersede. And finally, I would ask them to turn philosophers upon human nature, and as such to remember, that the capture of slaves on Northern ground, by any process, with law or without it, must necessarily be a sore and exciting offense to the mass of the people. It brings directly before their eyes one of the very worst scenes of slavery—a scene for which they are not prepared, and with which nothing can make them sympathize. Northern civilization has entirely outgrown the thing. There is a strong element of religious feeling adverse to it; and this feeling takes hold of the better classes—men who have stern convictions, and form no inconsiderable portion of the bone and sinew of the Northern mind.

Now, in view of all these circumstances, the dictate of prudence for the South is, not to excite either themselves or the North with the effort to capture slaves in the free States. This would be the greatest “peace measure” that can be adopted. The thing cannot be done without excitement on both sides; and all the “Union meetings” in creation will not be able to avert the result. The sympathies of nine men in ten at the North are, and must be, on the side of the fugitive slave. The fact is a credit to their humanity. It is not fanaticism and wildfire, but the natural and necessary effect of existing causes. Hence, I would say to the South:–If you wish quietude, let the runaway slave go; you will not catch one in a hundred by all the laws that can be put into action, and this will never pay for the evils produced. I would say this if I were a slaveholder, and at the same time a friend to the peace of the Union.

Suppose, however, the South do not choose to act upon this advice; suppose they insist upon the execution of the provision, as they have a constitutional right to do—what then? This is the pinching question. I will endeavor to meet it with candor. It has two sides, both of which deserve our attention.

On the side of the Southern claim is the argument drawn from the compact in the national charter; and as a constitutional question, it is a complete and perfect argument. Of this there can be no doubt. The States cannot constitutionally legislate against this provision; they cannot repudiate it without invading the terms of the national charter. I am not aware that any State has ever attempted this. No State has the power to do it, except in violation of the Federal Constitution. Those who have lectured the Northern conscience on this subject, use this argument, and this only. That it is a strong argument, no candid man will deny.

On the other side of the question, is the argument drawn from the Higher Law—a law much older than the Constitution. This argument contemplates the moral nature of the thing to be done, and affirms its essential iniquity. To my conscience, as an individual, this too is a complete and perfect argument. I am not able to view the act in any other light than as a gross moral wrong against the victim. I put the matter directly to the conscience of the hearer. If it is not morally wrong before God to capture a man who has committed no crime, and forcibly drag him back to a bondage he loathes, and has a right to loathe, and which he has done his best to shun—if this be not morally wrong, then what is there in the distinction between the right and wrong, then what is there in the distinction between the right and wrong, that is of any moment? Answer my question. What would you think of the act, if made its victim? Is it any better for another than it would be for you? Possibly, my judgment on this point is incorrect. Whether it is or not, depends on two questions; first, whether the slave is a MAN; and secondly, whether the principles on which this government is founded, are true—whether there is any truth, reality, or sacredness in the natural and inherent rights of man, as a moral and immortal being, made in the image of his God’ whether the Divine law of love and equal justice to our neighbor has any claim upon human regard. I have no secrets on this subject. I will not shout one thing in the public ear, and profess another privately. My view of man is such, that I could neither agree to do the thing, nor do it to fulfill the agreement of others. I would sooner die than be its agent. The Higher Law of Eternal Right would be in my way; and by its decision I must abide.

If, however, the civil community of which I am but a member, and in which I have the rights and responsibilities of but a single man, looking at this subject in all its relations, judge differently: if the good people of the State of New York, for example, have either less or a better conscience than I have; then, let them execute the provision in the most equitable legal way; and all I will do, is in these two sentences: As a moral being I will, whenever it is my duty so to do, put on record my expression of the wrong: As a good citizen I will submit. Here I stand in moral conviction; and here I must, or be a traitor to the God who made me. Those who urge the argument of the compact which we have honored in its place, and even some of God’s ministers who have spoken on this subject, are very careful to keep clear of the moral question. Forgetting this point, they make a very easy matter of it. Let them tell us distinctly, in plain Saxon English, what they believe in respect to the righteousness or unrighteousness of capturing men and sending them back to the bondage of Slavery. Let them not shun this question, but fairly meet it; and then both the South and the North will understand them. If the thing is morally right, then say so; if not, then say this. We concede that it is constitutional, while we believe it to be morally wrong.

Here it may be asked—Do you suppose the North wish to repudiate the Constitution as a whole, and dissolve the Union on account of this provision? This may be the feeling of some; but there is no evidence that it is so with the great mass of the people. It is not my feeling, when I look at all sides of this embarrassing and difficult question. I have no idea that now such a compact could be formed; but being formed, there is no evidence to show that the civil authorities, if called upon, would not execute it, and that, on the whole, the mass of the people would not sustain them. The ground would be solely the argument drawn from the compact, and not at all the merits of the thing to be done. While my moral convictions are and must be against it, still, I see no other course that is consistent with the terms of the Union, so long as the States remain together under the provisions of the national charter. The people feel the obligation of constitutional law; and so do I as much as they; yet, being a subject of God’s government as well as man’s, I feel the obligation of the Higher Law more. “Not that I loved Caesar less, but Rome more.” No compact, no law man ever made, shall restrain me from the declinature of what I believe to be a sin. The obligation of an oath even has its limitation; for no man is morally bound before God by his oath to the performance of a wicked and immoral act. Yet, he must not profess to keep it, and at the same time mean to repudiate it. This is insincere—a virtual perjury. So the Northern States must not profess a compliance with all the terms of the Constitution, unless they mean to be faithful to its injunctions. From this there is no escape, without destroying the legal sanctity of the instrument.

It may be asked—How will you reconcile these declarations of conscience with the legal duties of good citizenship under the Constitution of the United States? I answer: My citizenship in its relations to earth must never be so interpreted, as to annihilate all the rights and responsibilities of a personal conscience. My citizenship is no obligation to execute the will of this nation, or any part of it, unless I am its officer and chosen to remain such. The Quakers believe it to be wrong to fight. Hence, they refuse to bear arms; yet, they do not resist the civil authorities when collecting the militia fine. They suffer this penalty for conscience sake. Are they traitors? Are they bad citizens? Now in respect to the capture of the fugitive slaves, I stand on the Quaker principle. I will neither do it myself, nor say that I think it right when done by the civil authorities. But does not this imply some reflection upon the Constitution? It expresses myhonest conviction in respect to one of its features. I have never been taught to worship that instrument, or highly as I appreciate it, to assume its perfection as a standard in morals, especially in those clauses which refer to slavery. Let it not be forgotten, that this very Constitution contains the toleration of the foreign slave trade for twenty years—a trade now declared piracy punishable with death; that is, the people made a bargain to tolerate for twenty years what the nation now visits with its highest penalty. Was the thing any better for the bargain? Did it cease to be a crime for this reason? Forget not that morality and God are older and more infallible than the Constitution, and that a compromise with wrong for the sake of union does not convert it into right. Those who choose to give up their moral sense to the decisions of the Constitution, let them do so; I will not. I acknowledge no such citizenship under any government man ever made, as destroys the present obligation invariable and irrepealable of the Supreme Rule. What then will you do in respect to the wrongs of your country? Just what I am doing to-day: give you my opinions; state what I believe to be the truth; do my best to have those wrongs rectified. Anything else? Nothing else. Here I stop, where good citizenship and God equally bid me to pause. This is my creed as a Christian, being a citizen.

In respect to the recent Fugitive Slave Law, professedly built on this provision of the Constitution, I will say a word. The conflicting opinions in regard to it abundantly show, that it is not adapted to meet the public sentiment of the North. To me it seems questionable, whether Congress has any legislative power in the premises. The provision in the Constitution for the delivery of fugitive slaves is not a grant of power to Congress, but the imposition of an obligation upon the States. Such is the published opinion of Daniel Webster. In his speech in the Senate, March 7th, 1850, he says: “I have always thought that the Constitution addressed itself to the legislatures of the States themselves. It is said that a person escaping into another State, and becoming therefore, within the jurisdiction of that State, shall be delivered up. It seems to me that the plain import of the passage is, that the State itself, in obedience to the injunction of the Constitution, shall cause him to be delivered up. This is my judgment; I have always entertained it; and I entertain it now.” Such is the opinion of Daniel Webster. Whoever examines the Constitution, will fail to find any grant of power to Congress express or implied, to pass a fugitive slave law. He will find a compact addressing itself to the States, and making the delivery of fugitive slaves a matter of State obligation, and therefore of State legislation. 2 And here I frankly confess that if it were left to the State, I see no way, in which she could constitutionally avoid the obligation, when the claim for the slave is established by “due process of law,” without repudiating so much of the national charter. The Constitution does in plain words impose this duty upon the States. I am sorry that it is so; but my sorrow does not change the fact. This is the sad consequence of an agreement to do wrong.

The main ground, however, upon which the North have most strongly objected to the recent law of Congress, is to be sought in its features. It is to be remembered, that at the North we have no slaves and no slave-laws. Hence every man, black or white, is legally presumed to be a freeman, until he is proved to be a slave. It is also to be remembered, that the provision of the Constitution does not point out the process, by which the fact of slavery as against a person claimed, shall be judicially ascertained. It simply says that the slave shall be delivered up. What! Any person whom another may choose to claim as a slave? Surely not this; but the person who is proved to be such as the Constitution describes, namely, a fugitive slave. Here then is manifestly a trial on a question of fact. Is the man a slave? The mere fact, that he is claimed as such, is no proof. There is a fact to be proved before a competent tribunal, before the Constitution in the remotest sense puts his liberty in peril. How shall this question be tried? We answer; it ought to be by the ordinary method of judicial procedure—by what is known in the Constitutions and usage of the country as a “due process of law”—that is to say, a regular, open trial by a JURY of freemen, hearing the evidence and pleading on both sides, and then giving a verdict accordingly. The burden of proof, by the rule of justice, falls wholly upon the claimant. He must show all the facts supposed in the Constitution, in relation to the particular man he claims; namely, that the man is a slave under the laws of one of the States—that he the claimant is the owner, or his authorized agent—and that the person has made his escape from his legal master. These facts ought to be proved to the satisfaction of a jury, before the legal presumption of freedom is surrendered in the Free States. If, in any instance under the sun, a jury trial should be had, it is when a man is tried on the question, whether he is a freeman or a slave. This question ought to be thus settled before the act of delivery takes place. Let it not be said that it can be tried at the South, after the delivery is effected. The North ought never to surrender colored men to be transported to the South, and there tried under the presumptions and disadvantages of the slave code. This would be injustice. It is practically equivalent to consigning them to slavery. The act of delivery is in effect a verdict of slavery against the man. Suppose, that he is a freeman; how is he to show it, where a black skin presumes slavery, and possession presumes title? How is he to procure witnesses, and provide himself with a competent defense? The delivery of a person claimed as a slave, is essentially unlike that of a fugitive from justice. The latter is delivered up that he may be tried by an impartial jury, with all the legal securities of a freeman. Such is not the fact in regard to the person alleged to be a slave. Hence, the legal ascertainment of slavery, by a “due process of law” as recognized where the claim is prosecuted, ought to precede the delivery. So it strikes a large portion of the Northern mind; and I confess, this is my judgment, as a Christian and a citizen.

What, then, are the objections to the recent Fugitive Slave Law? I answer; it does not conform to these principles. It disposes of the whole question in a “summary manner.” Without the form of so doing, it in effect nullifies the right to the writ of Habeas Corpus. It precludes a trial of the questions of fact by a jury. It contains the anomaly of judicial tribunals created by other tribunals—a principle wholly unknown in the legislation of this country. In respect to the rule of testimony to be had in the case, it throws all the advantages on the side of the claimant, and against the person claimed. It makes acts of hospitality, and gospel mercy to the unhappy fugitive, a crime for which the agent may be severely punished. It authorizes the officers of the law, to compel the services of the people in capturing the slave, and returning him to bondage. In a word, it is an effort to carry out, upon the soil of freedom, the legal principles and practice of the slave-code. Such a law would be very much in harmony with Southern institutions and ideas; but is not so with those of the FREE STATES.

I might sustain this general estimate of the law by a long list of very respectable authorities. I will give you two opinions.

The Hon. Josiah Quincy, Sen., remarks:–“Could it have been anticipated by the people that a law would be passed superseding that great principle of human freedom, and that in this State, (Massachusetts) in which the claimant of ownership for a cow, an ox, or a horse, or an acre of land, could not be divested of his right without a trial by jury, yet that by the operation of such a law, a citizen might be seized, perhaps secretly carried before a single magistrate, without the right of proving before a jury his title to himself, and be sent out of the State, on the certificate of such single magistrate, into hopeless and perpetual bondage; it is impossible, in my judgment, that the Constitution of the United States could have received the sanction of one-tenth part of the people of Massachusetts.” Again he says:–“The people of Massachusetts understood that such claim should be enforced, in conformity to, and coincidence with, the known and established principles of the Constitution of Massachusetts.” Again he remarks: “Let the laws upon this subject be so modified as to give to every person, whose service is thus claimed, the right of trial by jury before being sent out of the land, and the universal dissatisfaction would be almost wholly allayed.”—New York Tribune, Oct. 17th, 1850.

The other opinion proceeds from the Governor of Ohio, in his recent message to the Legislature of that State. He objects to the law on the following grounds:–“Because it makes slavery a national, instead of a State institution, by requiring the costs of reclaiming the slave in some instances to be paid out of the United States Treasury: because it attempts to make ex parte testimony, taken in another jurisdiction, final and conclusive, in cases where its effects may be to enslave a man and his posterity for all time, and commits the decision of this question of civil liberty to officers not selected for their judicial wisdom or experience: because it attempts to compel the citizens of free States to aid in arresting and returning to slavery the man who is only fleeing for liberty, in the same manner as they would rightfully be bound to aid in arresting a man fleeing from justice, charged with the commission of a high crime and misdemeanor: finally, in relation to the manner of trial, and other particulars, the law is contrary to the genius and spirit of our free institutions, and therefore dangerous to both free and slave States, and consequently ought to be amended or repealed.”—New York Tribune, Dec. 10th, 1850.

Now, I suppose, these opinions represent the general sentiments held by a very large portion of the Northern people. They deem the features of the law to be an infringement upon chartered rights, not required by the provision of the Constitution, and in express conflict with other provisions of the same instrument. No one will deny that it has awakened a very strong excitement among the Northern people; and this is enough to prove that it is not well adapted as a “peace measure,” to settle the vexed questions that have been agitating this Union. In my judgment, it has made things worse rather than better. The legislature of Vermont, for example, has recently passed an act, securing to the person claimed as a slave, a right to the writ of habeas corpus, and directing the judge issuing the writ, to order a trial by jury on all the questions of fact involved in the issue. This takes the person claimed from the jurisdiction of the Commissioner, and places him under State law. It is not done for the protection of the slave against the demand of the Constitution, but for the due protection of her own citizens. Vermont virtually says by this act, that no man on her soil shall be deemed a slave, until so adjudged by a jury. It is her legal protest against not the end, but the features of the fugitive Slave Law.

I think it a great misfortune to both sections of the Union, that Congress should have passed the law in question. It does not, and in its present form never can, answer the mission of a “peace measure.” If it is to be practically a dead letter on the part of the South, this will be one thing; but if it is to be executed with stringency and rigor, then I mistake public sentiment, especially in the interior of the country, if the petitions are not long and loud for its modification or repeal. I do not see how, in view of all the facts, we can reasonably expect anything else. It is well to look at facts as they are on all sides, as well as one side.

After having heard this expression of my views in regard to the law itself, you may ask me, what shall be done, the law having been passed? I deem it a privilege to have the opportunity of answering this question.

In the first place, let every citizen remember that our system of government provides a competent tribunal to test its constitutionality. While it is to be lamented that legislation should ever be so extraordinary, as to make its constitutionality even doubtful, still, no private citizen can authoritatively settle this point. This must be done by a tribunal having jurisdiction. I have an opinion, and so have you, and both of us have a right to an opinion; but neither your opinion nor mine is clothed with any legal authority. This fact should be remembered by those who warmly condemn the law. They may express their opinions; yet they are not the legal judges in the case.

In the second place, let no citizen, be his opinions what they may in regard to this law, think himself entitled to resist the civil authorities in its execution. The moment he does this, he makes a new issue—one in which he ought to be crushed. He has no right to an opinion that shall be made the basis of rebellion. If, in his judgment, any or all of the requirements of this law are in conflict with the Higher Law, then let him obey God, always remembering that God does not require him to fight the civil authorities; and if there is any penalty incurred by this course, then let him meekly suffer it. This is orthodox for both worlds. While I could not force one of my fellow-creatures into bondage under any law it is possible for man to create; yet, if I were a civil officer, required to do it by the legal duties of my office, I would either do it or resign my trust; and I should certainly take the latter course. This is good morality also for both worlds. I would not hold the office, and violate my oath. I would not hold it, and violate the Higher Law. Hence, I would not hold it at all.

In the third place, let no citizen feel himself authorized to advise the fugitive slave to arm himself, and prepare for a deadly conflict with the civil authorities, in case of an effort to arrest him under this law. I regard such advice as positively immoral. I regard it as wanting in every element of good sense. Whatever may be the motive, the man who gives it is not, in fact, the friend of the slave, or of the community in which he lives. He has not well considered his own words; and, in my judgment, is justly obnoxious to public censure. If he were himself to do what he advises others to do, he would be guilty of open treason. He patronizes a war upon civil society in an illegal way. Much as I hate slavery and slave-catching, I have no sympathy with this doctrine. The natural and inherent right of self-defense is not the natural and inherent right of slaughter for no purpose, for no attainable end. I would not fight for freedom even, when I should be sure to involve both myself and others in greater calamities by it. If I said anything to the fugitive slave, I would exhort him to quietude, to good behavior amid his griefs and dangers; and if he could not feel safe in this land, then with shame and sorrow of soul I would point him to the north star, and tell him, if possible, to quit a country of so much peril to himself. I pity him, though I cannot unmake the fact that he is legally a slave in this land, go where he will. He cannot destroy this government, and I do not wish to do so. Hence, I cannot tell him to fight. He never will at my instigation. I reprobate the advice. This advice has been severely and deservedly rebuked. Yet, we cannot withhold the expression of our regret, that some who have ministered this rebuke, had not applied their conscience with equal intensity to another moral question. As Christians, what do they think of capturing and returning men to slavery?

In the fourth place, this law like every other, is amenable to the power of public sentiment. It has no sanctity that places it above the judgment of the people. If it misrepresent their will, nothing can save it from repeal or modification. It is one of the glories of our system, that when the people are displeased with a law, they can freely discuss it, and then vote it into its grave. It takes a little time to do this; but the event is always certain. In respect to this law, I wish for it no other doom than the legally ascertained judgment of the people. Those who think it right as it is, let them advocate it and vote for it. This is their right—as much so as it is mine not to do so, dissenting as I do from their opinion. If the majority think as they do, the law will stand; if not, it will not stand. For one taking into view all the circumstances of the nation, I doubt the practical wisdom of any attempt to alter it by the present Congress; yet, I greatly misinterpret the signs of the times, as well as the character of the Northern heart, if this law is not ultimately modified, especially if the South seek to use it with rigor. And in the meantime, I protest against any effort to silence or frighten Northern sense on this subject. I do honestly suppose, that Northern people have a right to think, and freely to express their thoughts. I am a Unionist, and so is the great body of the Northern mind; yet, I doubt whether this Union is to be preserved by getting up a panic. Congress enacted this law; and it has as much power to change it as it had to make it. To say that its modification or repeal will dissolve the Union, is a confession that some people are ready for treason. Much as I dislike the features of the law, I am willing to wait till an ascertained public will can do its work; and in the meantime, let no man think himself acting the part of wisdom or duty, in denouncing his neighbor for a difference of opinion. Let us have light and love, always remembering that no one is justly required to put out his own eyes, or repudiate either his common or moral sense, for the sake of love.

In the fifth place, as I doubt not, the President of these United States will do his official duty, as the Chief Magistrate of this nation—“take care (I am quoting his recent Message) that the laws be faithfully executed.” As a citizen, I honor the doctrine, and the man for its utterance. As a public officer, acting under the solemnity of an oath, he has no other course; we the people, no other safety. He is the sworn executive of the will of this nation, legally ascertained. The will of this nation is not that there should be rebellion anywhere, North or South. Hence, if necessary, as I hope it never may be, he must crush it by the last resort of government—the power of the sword. He is to show no favor to the accursed spirit of treason. I mean this equally for both sections of the Union. Whoever tries this, I trust, will have an ample opportunity to judge whether this is a practicable government, whether it has any power, and can execute its own laws. If government must coax and pet every man who chooses to whine, then it is no government. Both the North and South are in this Union; and if we have a faithful President, as I trust we have, they will stay there. Let it be well understood, that this government is to go forward and do its proper work, making laws or altering them at the command of the public voice; let it be known that traitors are to be hung as high as Haman, that the first man who is guilty of treason within the meaning of the Constitution, forfeits his life, and so of the second, and the third, and so on; let not a threat be followed by a panic, but met with that calm and dignified firmness that becomes government; and there will be no civil tumult anywhere; the party of disunionists will lose all their thunder, and run down to nothing. There is no occasion for a resort to the revolutionary right. There are no grievances that call for it. Neither section has so invaded the chartered rights of the other, as to justify in either a rebellion against the Federal Government.

It is a species of incipient treason to be constantly threatening the dissolution of the Union, in case of certain contingencies. He who open resists this Government, who attempts to revolutionize it, let him be treated according to law. He starts a new question, very different from the one whether slavery and slave-catching are right or wrong. With him on this point I have no sympathy. If the Government, State or Federal, pass a law which, in his judgment, imposes duties in direct conflict with the Higher Law of his God, then let him obey God, and quietly suffer the legal consequences, if there be any, leaving the final judgment to decide whether he was a martyr or a fool.

And, finally, let us commend our country to the God of nations, invoking the care and direction of his Providence. Nations as such, are amenable under His government. In His sight “righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach to any people.” Of the nation that will not serve God, it is written, that it shall perish, that it shall be utterly wasted. There is no principle truer, none of more thrilling interest to this Republic, than that God holds organized communities responsible for their conduct. The American people must do right, and thus please God; or in due season the day of vengeance will come. His favor is more important than a vast navy, or strong ramparts, or the skill of politicians. Let us invoke that favor. Let us beseech the great God to dispose events for his own glory, and the nation’s good. There are great dangers in our path. There are serious evils that call for redress. There is an awful incongruity in our practice, evidenced in the melancholy fact that on this soil of freedom, blest with the purest civil system man ever formed, millions of our fellow-creatures are doomed to the toil and bondage of slavery. The sigh of the bondman has entered into the ears of the Lord of Sabbath. Say what we will, conceal it as we may, slavery is our great danger—the most stupendous form of wrong found in the bosom of this people. It always has been, and always will be, the curse of a people who practice it. It is the source of our present difficulties. It has outlived its day. It ought long since to have gone to rest. It is the fretting sore of our institutions. It ever will be a difficulty, until a rectified public sentiment shall demand and secure its removal. Neither by a divine, nor by a human right, does it exist on this soil. That sober, and honest, and earnest, and moderate counsels—not the less determined for their modification—free, on the one hand, from the spirit of reckless passion and wild denunciation, and on the other, from that dishonorable policy which is ever ready to sacrifice the truth;–counsels neither palsied by a panic, nor driven by a storm of fury—counsels commending themselves to God for the equity of their purpose, and the wisdom of their mode – counsels that embody the honest and manly sense of enlightened Christian men, exercising their rights, and doing their duty in the fear of God: – that all this is needed, greatly needed, in all parts of this Union, is very apparent.

I see not what benefit is to arise from the sundering of the political ties that make us one nation. I thank God that there is very little desire for this at the North. Most of the menaces proceed from the South. Let them well consider before they act. The attempt would be to themselves the most perilous experiment, a misguided people ever undertook. The weakness is with themselves. The power of this nation is not in their hands, if brought into effective and vigorous action. This power is in the free States; and there it must remain, by the inevitable necessity of a natural cause. May God preserve the South from committing themselves to the dreadful issue. I can conscientiously and piously pray for the peaceful perpetuity of this Union, and not less so for the removal of the evils that constitute its danger, and so most expose us to the displeasure of God. This is my prayer. I trust it is yours, while to day we thank our common Father for blessings past, and implore others yet to come.

In closing let me say that you now have my whole soul on this great subject. God is my witness that I have not made a speech for Northern or southern ears, to manufacture capital with either. I despise the infamous trick on a theme of so much importance. I have not sought to magnify one truth at the expense of another. These are my sentiments. So I believe. Not a sentence has fallen from my lips, which, so far as I can now perceive, I should wish to recall. I came here not to please or offend any body, but to speak the truth according to the best light of my own understanding. Whether these opinions suit you, is for you to settle. I have, under a solemn sense of duty, assumed the responsibility of their utterance; and I do not expect to disclaim it. Thanking you for having attentively listened to these observation, I now commend you and my country, and the slave, to the guidance and mercy of that God, whose government is always just, whose grace is equal to our wants, whose providence is our personal and national shield, whose law is the HIGHEST in the universe, and at whose bar both speaker and hearer will soon appear. May He be merciful t us all!

Endnotes

1. The legal reason for this provision is very plain. Slavery is not recognized by the law of nations. Hence, as a general doctrine, the moment the slave leaves the local law of bondage, he becomes free;–he does not carry his legal chain from one civil community to another. The States in this Republic are distinct and separate communities, existing in the bosom of one nation. If, therefore, there were no provision in respect to fugitive slaves, each State might determine for itself, whether the local law of slavery shall follow the victim, when coming within its jurisdiction. The people, in adopting the Constitution, agreed that it should—that the question should not be left to the option of the States. They made an exception to a general rule of justice. They agreed that a slave, by the laws of one of the States, escaping into another State, should not in the latter become a freeman, but should be delivered up on claim of his legal owner. They limited the powers of the State in this respect, and by the Constitution created a State obligation. The manner of legally ascertaining the facts supposed, is not specified.