Below is a Memorial Day sermon by Rev. Jewell, preached in San Fransisco on May 29, 1875. See additional sermons on Memorial Day here and here.

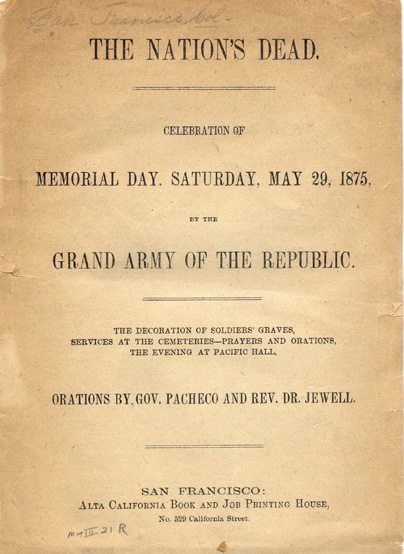

THE NATION’S DEAD

MEMORIAL DAY, SATURDAY, MAY 29, 1875,BY THE

GRAND ARMY OF THE REPUBLIC.

THE DECORATION OF SOLDIERS’ GRAVES,

SERVICES AT THE CEMETERIES – PRAYERS AND ORATIONS,

THE EVENING AT PACIFIC HALL,

ORATIONS BY GOV. PACHECO AND REV. DR. JEWELL.

SAN FRANCISCO:

ALTA CALIFORNIA BOOK AND JOB PRINTING HOUSE,

No. 529 California Street.

REV. MR. JEWELL’S ORATION.

Mr. President and Fellow Citizens: Words never seem more meaningless and feeble, than on an occasion like the present, yet are never consecrated to holier uses, than when they embalm such deeds, as we today are seeking to communicate. Yet we find encouragement in that. Historic precedent, declares the value of speech, and its power in reproducing the heroism, in which the nations of the past have gloried. It was thus that Marathon became the mother of Thermopylae. Thermopylae of Salamis, and Salamis of Platea.

It has been said that the tomb of Leonidas as long as an annual oration was delivered from its side, produced a yearly crop of heroes. It was thus that the dead body of Lucretia brought forth the liberators of Rome. Romans begat Romans, not more by raising triumphal arches to her victorious Consuls than by the constant recital of their glorious history.

Egypt not only reared obelisks and monuments to her braves, but on them carved the history of their bravery.

Greece enacted that her heroes slain should have an honored sepulture, amid imposing rites. She encased their ashes in cypress and gold, and after leaving them in state for four days, bore them to their resting place, amid fountains, and walks, and stately columns, amid groves sacred to Minerva, their tutelary Goddess, made doubly beautiful by monuments and statues carved by her illustrious masters. And here standing upon some lofty platform, her most eloquent orators would pronounce their valor in words of thrilling pathos.

Germany embalms the heroism of her sons in grateful sons and story, and makes their children feel, “’Tis sweet to die for Faderland.”

France not only confers her Legions of Honor, but chronicles the act of her heroes in fitting words.

England confers her titles of nobility, and grants her chieftains an honored sepulture in Westminster Abbey.

If these have thus sought to perpetuate the memory of their heroes slain, and thus reproduce their lofty example, what shall Americans not do to honor the resting place and memory of her fallen braves, of more than Roman or Spartan valor? Ours is indeed a nobler tribute, because it springs not from a monarch’s edict, but from millions of grateful, loyal hearts. Less demonstrative and imposing, it is true, but more heartfelt and appreciative – the simple commemorative services by which a nation saved, would tell the story of its gratitude. It sweeps the heart-strings with a touch of tenderness unknown to nations of the past, for it tells of privileges more exalted preserved to us; it tells of a patriotism more lofty and of heroism more sublime than was ever known by any nation of the world.

How thrillingly beautiful and touching the incipient history of this day, and the peculiar nature of the memorial offerings then made!

The ceremony is said to be older than the organization by whom it is chiefly superintended now.

In 1864, thousands of our sons and brothers who had worn the blue were sleeping in soldiers’ graves all through the Southern States, and those who would could not and those who would not visit them or do them honor. Amid the beauties of the vernal bloom, the women of the South went forth to strew flowers on the graves of their slain.

Immediately those whose dusky brows had been baptized with the sparkling dews of Freedom, and knowing to whom they owed their emancipation, anxious to recognize their obligations to the vicarious sufferings, toil and death of those who slept in the unhonored graves, and with a love and devotion as lofty as ever thrilled a human heart went forth to field and wood, and gathered the wild flowers in their beauty. Under the cover of a darkness, only relieved by the twinkling stars, they stole softly and silently to the slighted graves of our fallen heroes; and bedewing them with tears and breathing benedictions over them, reverently and tenderly laid thereon their humble floral offerings.

Beautiful and fitting initiation of a custom which is now fully enshrined in the hearts of us all, and shall be continued by our children’s children to the end of time. As beautiful and touching and well-nigh as religiously sacred as the offerings of the women who came to the sepulcher, very early in the morning, while it was yet dark, for fear of the Jews, bringing spices with which to anoint the body of their Lord. Each recognized in the one whose grave they blessed; a Savior, from degrading chains, to a heritage of manhood. But what is it that we celebrate, and why do we feel called upon to continue this beautiful and touching observance? Like those who originated the custom, we feel that we are debtors to those who, living or dead, became a part of that great holocaust of blood which stained so many fields of our land, and made so many decks slippery with human gore. It is ours equally with them to sing:

The brave and good and true,

In tangled wood, in the mountain glen,

On battle plain, in prison pen,

Lie dead for me and you.Four hundred thousand of the brave

Have made our ransomed soil their grave,

For me and you.In many a fevered swam

By many a black bayou,

In many a cold and frozen camp

The weary sentinel ceased his tramp,

And died for me and you.From Western plain to ocean tide,

Are stretched the graves of those who died

For me and you.In treason’s prison hold

Their martyr spirits ‘grew

To stature like the saints of old,

While mid dark agonies untold

They starved for me and you.The good, the patient and the tried,

Four hundred thousand men have died,

For me and you.

[Edward C. Porter,”The Nation’s Dead,” Round Table, September 9, 1865.]

How unquestioning and unhesitating the patriotism, and how awfully sublime the uprising! The war took the Nation by surprise. The chief conspirators thought they had effected their object fully. In four years of assiduous care, they had stripped the Northern arsenals and conveyed the arms to the South. They had sent the Navy to the ends of the earth, so that at the critical moment it was good as no Navy. They had reduced the Treasury to bankruptcy, and destroyed its credit , as they thought, hopelessly. They had compelled a weak-spined President to say in his annual message, and contrary, we believe, to his convictions, that the Union was going to pieces and he had no authority to interfere.

We stood watching and trembling as one. State after another declared itself out of the Union. One after another of the Southern forts and arsenals were appropriated. One after another of those educated to the arts of war, in our military schools, joined themselves to the Rebels. A deep and ominous silence seemed to settle down upon us, of the North. It was mysterious, and unintelligible. Some thought it meant distrust of our forms of government. Some even interpreted it as a sympathy with the Southern uprising.

It was as the silence of Nature in the torpid Winter. It was as the hush of life in the darkness of night. It was as the stillness of earth and sky, that precedes the breaking of the tempest.

But no seer could divine what that waking would be. The silence was deep and awful. Men began to feel that the sentiment of loyalty was wanting in American hearts that ours was not a style of nationality to inspire that lofty sentiment.

But we soon learned better. The silence was broken and interpreted. The suppressed fire flamed out. In that mysterious silence the fires of a holy patriotism were nursing themselves, and the glow was becoming hotter and whiter. The pent up forces were moving and accumulating, like the meeting and commingling elements of subterranean fires before the mountain’s summit opens, or the earthquake rocks a continent.

Oh how grand was the bursting forth. It was deeper and broader than the “father of waters.” It was more forceful and impetuous than the gushing life of Spring. It was like the rushing mighty wind, in which was the sounding beat of celestial pinions, and which filled Jerusalem on Pentecost, crowning each mute disciple with cloven tongues of fire.[Acts 2:1-3] No sooner did the electric current smite us with the intelligence that on that April morn the old flag had been dishonored and trailed in Southern dust, than up went the Stars and Stripes hillside of the loyal North, and thousands sprang forth as one man to defend that which had made America tremble as a magic word of hope, among all the down-trodden nationalities of the world.

Then it was, as our noble chief began to speak, the long columns began to move. Soon as the voice was heard, thousands of those who seemed wholly absorbed in industrial pursuits, sprang to arms. At the first call seventy-five thousand responded HERE. Again the call was made, and the answer was in fact and in song,

We are coming, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand more.”

[Robert Morris, “We Are Coming Father Abraam,” New York Evening Post, July 16, 1862.]Our foreign-born sons, God bless them, stood side by side with those born on American soil.The Irishman followed Sheridan, and the Dutchman “fought mit Sigel.”

Partisanship gave way to patriotism. Douglass, the defeated Presidential candidate, all honor to his memory. Dickinson and Dix stood side by side with those who had been their political antagonists, and from every shade of political complexion came declarations of unconditional loyalty to country. When the war broke out, the London Times predicted that the Rebellion could not be subdued without extreme conscription, and in enforcing this, none could be forced into the service who did not vote for the existing administration.

They knew not the intensity of American patriotism. They forgot that each man here is a sovereign; an integral part of the nation, and calls no man lord and master. That each was striking the blow for himself, and felt the greatness and responsibility of American citizenship. That no man regarded the payment of any sacrifice or treasure too great which was required to perpetuate the Republic in the consummation of her missions as the political and civil evangel of the nations.

Men were there as privates in the ranks who were fit to be Presidents and Ministers of State; and men there died whose ashes are worthy of sepulture in Westminster Abbey nay, more, that are worthy of being buried in American soil and have their graves annually showered with the floral offerings of their surviving comrades-in-arms. Oh, how sublime was the scene. Souls took fire with the holiest patriotism.

Mothers, hiding the starting tears, sent their sons to battle, with tender benedictions; wives, and sisters, and maiden lovers, girding themselves with womanly fortitude to meet an hour awful with anguish, bade adieu to the young and brave, who were to return no more.

Fathers forced back the manly tenderness that choked in their words of inspiring counsel, and little children clung with indefinable forebodings to loved papas they should never embrace again.

Our streets echoed to the soldier’s tread, and “God bless you” was breathed in accents tremulous with hope and fear.

Our army was the wonder of the world. Over 2,600,000 soldiers entered the ranks, and the heroism which sent them forth remained with them to the last.

How bright seem today the examples of illustrious daring which then fascinated the gaze of an admiring world.

A Sherman mowing a swath thirty miles wide through the very center of the rebellious territory, and he serried ranks of the protesting chivalry.

A Hooker charging the enemy above the clouds on Lookout Mountain.

A Sheridan streaming through forty miles of foam and dust, and bringing order out of chaos and organizing victory out of defeat.

A Farragut lashed to the mast-head of the Hartford, and amid the storms of shot and shell, winning immortal triumphs.

A Grant holding on like a bulldog to the throat of the Rebellion, even when Lee sent his Generals with an army to the very gates of Washington.

Come with me for a moment and let me lift the curtain, and take a look into the tent of the Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Potomac. It is past the hour of midnight. Sad hearts are entering there, for it is a gloomy hour in the great campaign of the Wilderness, a night following a day of disaster. The army was fearfully hewn in pieces, and it seemed almost inevitable that the morrow would find our battered, bleeding regiments, reeling and staggering toward Washington. Hard by them on the gory field lay fifteen thousand of our noble braves, wounded, dying, dead.

A file of noble officers, one by one, reach the door of that tent, give a silent salute, and pass in, and as silently take their seats.

Meade, Sedgwick, Hancock, Warren, and others, make up the circle. For thirty minutes not a word is uttered. It is an awful silence, which at length is broken by the most reticent man among them. The question passes from one to another, “General can you tell me what is to be done?” A sad and tremulous “No!” came from the lips of each. The Chieftain seized a pen, hastily passed it over a fragment of paper, and passing it to Meade, and, “Break the seal at four o’clock and march.”

He did the same for each of them, and each retired ignorant of what was ordered, but anticipating a retreat. Anything else seemed madness run mad. Had they known that the orders were to advance a possible mutiny had followed.

The next morning, before 5 o’clock, the army moved and within an hour Lee’s scouts stood before him, disclosing the state of affairs. He read the dispatch; he tore it in fragments – and, stamping vehemently, he exclaimed: “Sir, our enemy have a leader at last, and our cause is lost, sir, lost!”

He supposed us hopelessly hewn in pieces, and had ordered that his men be allowed to take a long rest that morning; but awoke to see the army he thought demoralized, flanking him and cutting off his base. He fought and retreated and acknowledged his doom was sealed. Who but the man of iron nerve could have met the responsibilities of that midnight hour? I confess to a liking of that kind of Caesarism it be.

It is recorded of a French soldier of many battles that although offered promotion, he persisted in remaining in the ranks. His admiring and grateful sovereign sent him a sword inscribed, “First among the Grenadiers of France.” When he fell on the field of glory, the Emperor ordered his heart embalmed and placed in a silver case, and passed into the keeping of his company, with the command that his name be called at each roll-call, and the oldest grenadier respond, “Dead upon the field of honor.” Oh, how many names are left to us, upon the mention of which the response should ever be: “DEAD UPON THE FIELD OF HONOR.” When in reverential love, as this anniversary returns, and floral wreaths shall fall from comrade hands upon the honored graves of many a hero slain, shall not angels, who keep the camp-fires along celestial heights, hear a million throbbing hearts bearing gratefully the answer to the roll-call of our heroes, BAKER – Dead upon the field of honor. LYON – Dead upon the field of honor. MITCHELL – Dead upon the field of honor. RENO, KEARNEY, MANSFIELD, WADSWORTH, SEDGWICK, McPHERSON – all dead upon the field of honor. “Probe a little deeper,” said a wounded soldier to the surgeon feeling for a ball in the region of the heart, “Probe a little deeper, Surgeon, and you will find the Emperor.”

Oh, how many an idolized commander is enshrined in the hearts of comrades her tonight. Well may you lead us to these sacred shrines, and allow our tears to mingle with yours as you pay them you undying homage.

They sleep well, and henceforth their names belong to American history. These mounds will never cease to preach liberty and heroism more eloquently than the living orator. It is well that comrades move in garlanded processions to the shrines of deeds so immortal. It is a pageantry burdened with honors which can find no other adequate expression.

But we are not to forget that it is not alone the personal heroism manifested, that justifies these memorial demonstrations. It was not a mere match of prowess or display of personal courage. It was not a mere exhibition of matchless endurance and patient suffering for championship. It was not a a mere gladiatorial combat for the entertainment and admiration of the on-looking Nations. It was an issue between right and wrong; between political truth and heresy; between preservation and destruction. It was a conflict for the life of our nationality, “the green graves of our sires, God and our native land.” In vain all the struggles of the past; in vain all the sufferings of the heroes of the Mayflower; in vain the struggles of our Revolutionary sires; in vain the blood that crimsoned Bunker Hill and Lexington, Monmouth and Yorktown, had not America’s sons shown themselves worthy custodians of freedom’s lofty heritage.

It was the last great conflict for freedom, the point of history upon which hung the hopes of freedom’s lovers among all nations. It was the culmination of a conflict of a thousand years.

Other lands had struggled for freedom. Greece struggled long and bravely, and come short of the goal. Poland and Hungary in their turn had grappled with the oppressor, and again been ground into the earth. Again and again had our exalted guest, the Goddess of Human Rights, come from dungeons with the dust of ages on her garments – from chains which had eaten into her soul – from scaffolds, with the blood of martyrdoms on her forehead – from attics, where she had drunk her tears in the bitterness of her soul, and looked in among the nations for a place where she might remain as a presiding genius.

I see her in the forests of Germany, away back before the Christian era proper, as is her swathing bands she lay nursed by those liberty-loving tribes.

I see her as she comes to England, and in her childhood asserts herself, as with Magna Charta in her grasp, she resisted Absolutism through so many eventful years. I see her in her youth, standing with Cromwell, and uttering her protest against the Norman-French idea of sovereignty. I see her, finally, as she came across the sea to find in our loved land a broader field and a more congenial clime. I see her, as she stands with our fathers at Yorktown, Monmouth and Bunker Hill.

I see her breathing on that noble assembly in old Independence Hall, as one by one, with trembling hand, they pledge their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor.

I see her as she smiles and weeps at Valley Forge. I see her as she bends over a Washington as he prays, and says, “We must, we shall prevail.”

I see her, as afterward she presided over a history, which, verified before a wondering world, had all the charms of romance.

But did we not also see her, as on our National Birthday Anniversary we read our “Bill of Rights,” which pronounced all men free and equal, bring a tear from her fair cheek, as she caught the echo of that disrespectful titter which ran around the world, as four millions, bearing the image of their Maker, clanked their chains and groaned for freedom?

Of heroes of the Blue, we say: “Your devotion not only bound the Union, but unbound the slave and buried beyond the hope of resurrection, the shameful relic of a barbarous age.”

For this all nations thank you, and shall continue to thank you to the end of time.

And may we not rejoice that in that fiery ordeal the pestilent heresy of State Rights was burned up? And hereafter we are to be known as an absolute organic unity? Woe, unmingled woe, to the profane hand which shall ever seek to sever us. No North, no South, no East, no West!

A union of principles none may sever,

A union of hearts, and a union of hands

The American Union Forever.

[George Pope Morris, Poems (New York: Charles Scribner, 1860), pp. 68-69, “The Flag of Our Union.”]

The war and its attendant history has made us more capable of self-government.

The fundamental principles of our institutions have been made clearer and dearer to us.

The whole people have accepted as never before, the whole democratic theory of nationality. “For weal or for woe,” our future is the future of a consistent and inexorable democracy.

To the comrades of the Grand Army of the Republic here gathered, allow me a parting word. To the life-long enjoyment of the peaceful heritage your valor helped to win – to our sanctuaries, our homes, our hearts, we receive and welcome you. Never was the Angel that records the deeds of true heroes made busier than when your brave hearts and strong hands furnished him employment. Your bravery challenged and received the homage of the world. Great interests confided to your hands were not betrayed, and a grateful nation shall continue to pay you honor. Our children shall be taught to lisp your names with reverence, and our children’s children shall moisten your resting places with their tears. Ye heroes of many a hard and well-fought battle, we will never, never forget the story of your heroism. Our youth shall emulate your virtues. Future generations shall study your record, and transmit to others the story of your sacrifice; and those who, in after years, shall join in the services of the Soldiers’ Memorial Day, inspired by your glorious example as they drop the garland upon your patriot grave, shall lift the hand to Heaven and say, “THIS SHALL BE LIBERTY’S HOME FOREVER.”

At the conclusion of the exercises, one of the Brothers of the Grand Army sang “John Brown.” Being accompanied by the band and a chorus of the entire audience, after which the meeting was adjourned, satisfied with the days’ good done.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!