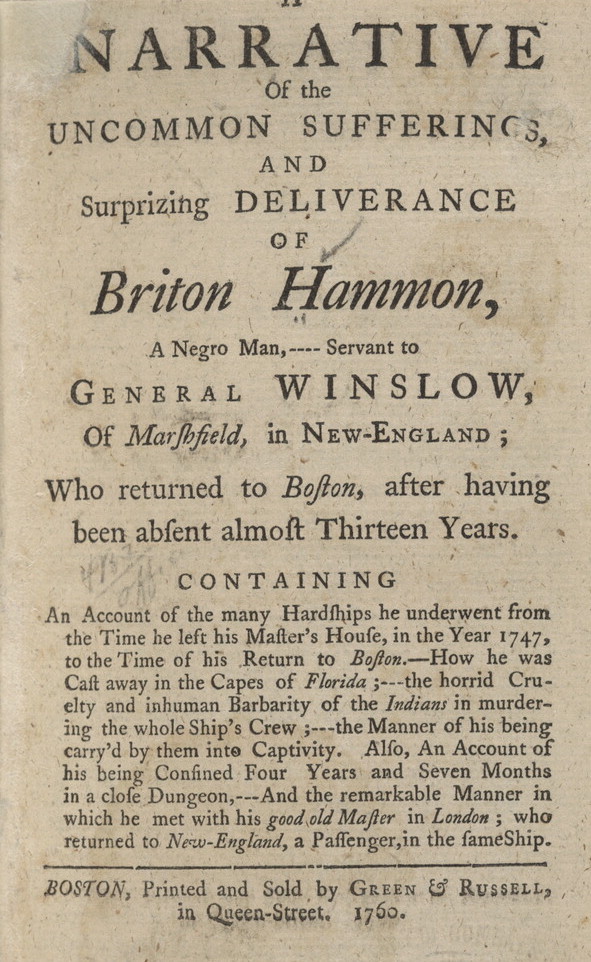

In 1760 America became the first nation to publish a work of prose by a writer of African descent.1 In fourteen pages, the slave and author Briton Hammon recounts nearly 13 years of trial, hardship, and adventure—ending in a way that would surprise most people today. Only two copies of his original work remain in existence, meaning Hammon’s remarkable story of hardship and God’s deliverance is rarely told today, but he deserves credit for beginning a literary tradition which would grow to include people like Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northup, and many others.

In 1760 America became the first nation to publish a work of prose by a writer of African descent.1 In fourteen pages, the slave and author Briton Hammon recounts nearly 13 years of trial, hardship, and adventure—ending in a way that would surprise most people today. Only two copies of his original work remain in existence, meaning Hammon’s remarkable story of hardship and God’s deliverance is rarely told today, but he deserves credit for beginning a literary tradition which would grow to include people like Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northup, and many others.

Hammon starts his narrative in 1747 when his master, General John Winslow (the great-grandson of the Mayflower Pilgrim Edward Winslow), granted him leave to sail by himself to Jamaica for Christmas.2 However, after a successful cruise to the Caribbean, the vessel accidentally ran onto a reef off the coast of Florida during its return voyage. For two days the ship and crew were stranded, unable to move and with little hope of rescue.

Before they were able to make it to shore, twenty Indian canoes approached them under the guise of an English flag. Upon getting closer, they attacked and killed all of the sailors except for Hammon who, “jumped overboard, choosing rather to be drowned, than to be killed by those barbarous and inhuman Savages.”3 The marauders soon captured him, however, and Hammons describes how the they:

“Beat me most terribly with a cutlass [sword], after that they tied me down… telling me, while coming from the sloop [the ship] to the shore, that they intended to roast me alive.”4

Upon reaching the Indian camp, Hammon was relieved that, “the Providence of God ordered it other ways, for He appeared for my help,” preserving his life till the chance for escape presented itself.5 Soon a Spanish ship, whose captain was a personal friend of Hammon’s, miraculously found him and helped him escape to Havana. The Indians nevertheless persisted, tracking him down and suing the Spanish Governor for his return. Instead of simply giving the shipwrecked slave back to his captors, the Governor purchased Hammon from the Indians for $10 to be one of his slaves.6

One year into his Havanan servitude while walking down the street, an impressment gang (groups of men who would physically coerce people to fight in the Spanish navy) suddenly captured Hammon and imprisoned him for nearly five years because he refused to serve in the fleet—all unbeknownst to the governor. Through years of appealing random visitors, Hammon successfully got word to the governor who freed him from the dungeon only to become a slave once more.

After two failed attempts to escape from the Havana, Hammon successfully worked himself on board a British Man-of-War vessel about to depart for England. The governor was not one to let him go without a fight though and demanded the captain turn him over immediately. This British captain, however, was a man of courage and, “a true Englishman, [who] refused… to deliver up any Englishmen under English Colors.”7

Having now been liberated from Spanish slavery, Briton arrived in England and signed up for the British navy, fighting in several naval battles before being wounded. After an honorable discharge from the service, he continued to hire himself out on numerous voyages eventually signing up for a voyage to Guinea.8 However, before shipping out to Africa, Hammon heard of a boat set to sail to Boston. Instantly, he abandoned plans for Africa and instead joined the crew heading back to the colonies.

Having now been liberated from Spanish slavery, Briton arrived in England and signed up for the British navy, fighting in several naval battles before being wounded. After an honorable discharge from the service, he continued to hire himself out on numerous voyages eventually signing up for a voyage to Guinea.8 However, before shipping out to Africa, Hammon heard of a boat set to sail to Boston. Instantly, he abandoned plans for Africa and instead joined the crew heading back to the colonies.

To his great astonishment and apparent joy, Hammon heard that his old master, Gen. John Winslow on the same exact vessel. He explains that:

“the Truth was joyfully verified by a happy sight of his person, which so overcame me, that I could not speak to him for some time—my good master was exceeding glad to see me, telling me that I was like one arose from the dead, for he thought I had been dead a great many years, having heard nothing of me for almost thirteen years.”9

In short, Briton Hammon lived nothing short of a miraculous life, something which he was the first to admit, exclaiming:

“How Great Things the Lord hath done for me; I would call upon all men, and say, O magnify the Lord with me, and let us exalt his name together! O that Men would Praise the Lord for His Goodness, and for his Wonderful Works to the Children of Men!”10

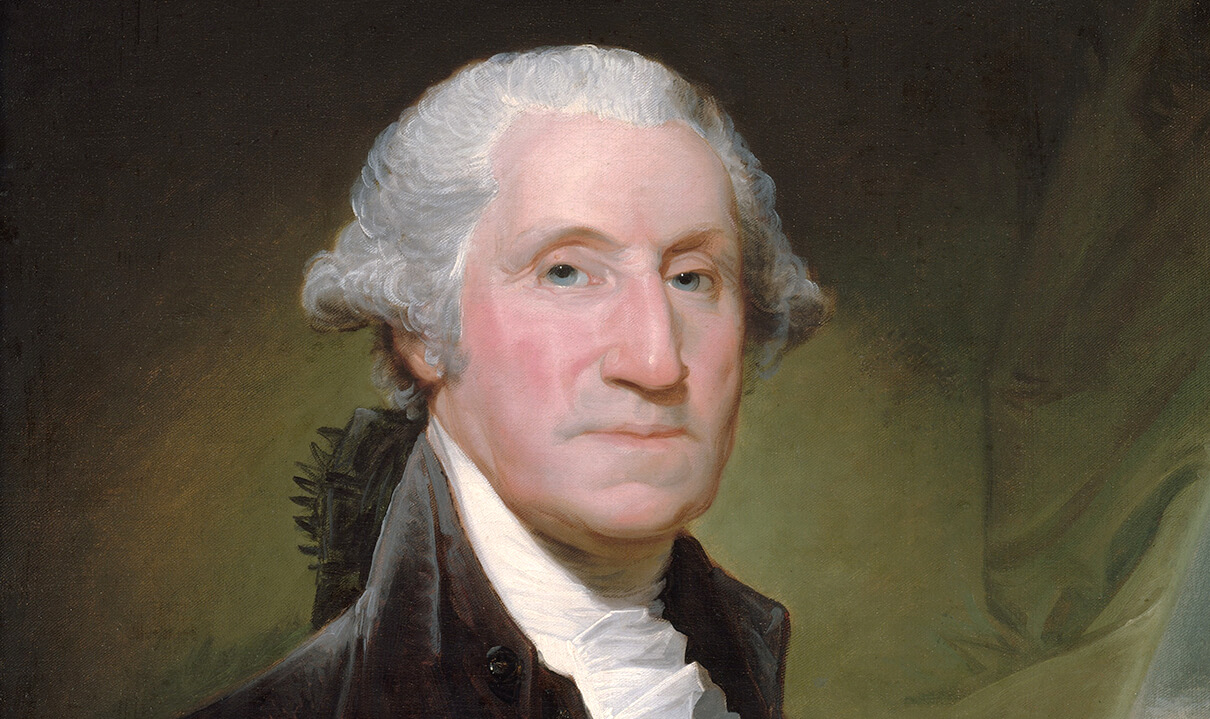

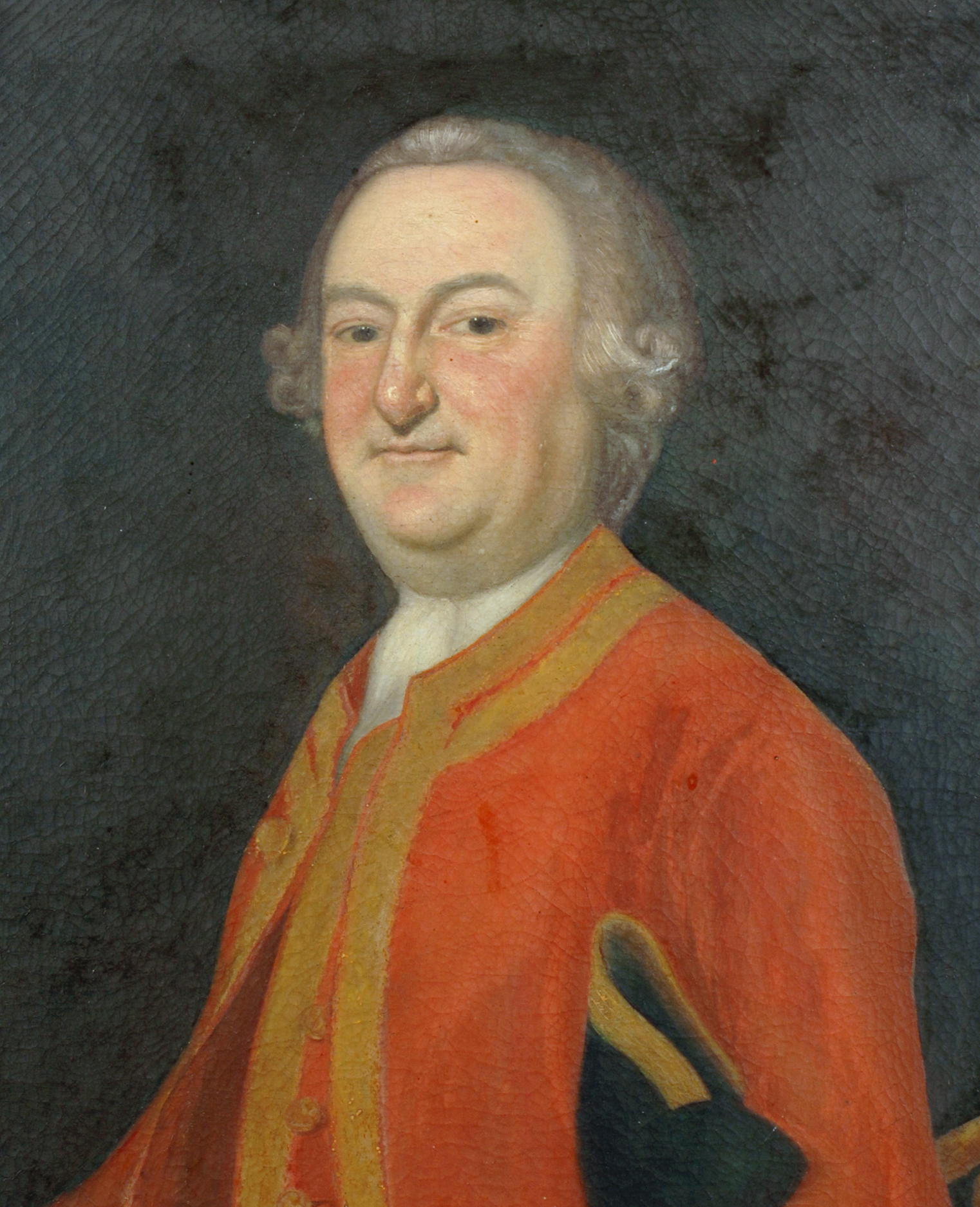

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Briton’s narrative is the apparent fondness he had for his master. In order to begin understand this, some context must be given. As mentioned, General John Winslow (1703-1774) was the great-grandson of the Governor Edward Winslow who came on the Mayflower in 1620. Although seemingly good-natured, over three generations the piety of the Winslow family was merged with a martial spirit and led John into the military, participating in operations from Cuba to Nova Scotia as a part of the British army.11 As a Major General and a descendant of an early governor, he commanded respect even during a period of increasing unrest as the War for American Independence was quickly approaching.

Naturally then, it is no small factor in Briton Hammon’s story that his master is none other than the noted General. However, on Christmas day 1747 when Briton departed, his master had yet to climb the ranks as most of Winslow’s military leadership would occur over the thirteen years while Briton was gone. Thus, upon his miraculous reunification with the now General Winslow, he remarks that, “I asked them what General Winslow? For I never knew my good Master, by that Title before; but after enquiring more particularly I found it must be Master.”12

That a slave would seek out his master or return to them after being away for many years almost recalls the Biblical story of Onesimus and Philemon. Interestingly, prior to the reunion Briton lamented that while he was extremely sick and poor it was, “unhappy for me I knew nothing of my good Master’s being in London at this my very difficult Time,” indicating that had General Winslow known of his condition his master would have undoubtedly come to his assistance.13

The fact that General Winslow is universally referred to in affectionate terms strikes the modern reader as especially remarkable considering the fact that at the end of his journey Briton had not arrived at what we would consider freedom, only a return to slavery. Combined with the decision to return to Boston instead of pursuing his career in the merchant marine on the voyage to Guinea, we are left to question why a slave would intentionally seek out his old master.

As mentioned above, Hammon’s slave narrative seems strangely different than the stories of Douglass, Northup, and the rest. Instead of fleeing from slavery, Hammon voluntarily returns to his master in America—choosing to board a ship to Boston instead of one to Africa. Why would Hammon choose America, the land of his slavery, over Africa, the land of his heritage? Why would he choose slavery abroad, over freedom at his ancestral home?

The answer to this is the realization that Hammon, far from identifying his home as Africa, has become a colonial American in thought and deed. Through his life in the colonies, an emerging nationalism has taken root and supplanted any previous attachments.

Briton’s narrative is not one of slavery to manumission, but rather one of coming to the place he considered his home. In fact, after having suffered at the hands of un-Christian Indians and barbarous Spaniards, Briton sees the reunification with Winslow as a kind of freedom and a return to his true home. He explains:

“And now, that in the Providence of that GOD, who delivered his servant David out of the paw of the lion and out of the paw of the bear, I am freed from a long and dreadful captivity, among worse savages than they; And am returned to my own Native Land” (emphasis added).14

The fact that he considers New England as his native land explains why he chose to abandon his plans to sail for Africa. For Briton Hammon, Massachusetts is his homeland and where he desires to return. In this sense, his story actually does relate closely to the later slave narratives—they all were seeking a home. Hammon saw himself as an Englishman, and was seen by others (such as the helpful ship captain) as an Englishman. A new identity had sprouted within him, and he now claimed a new homeland.

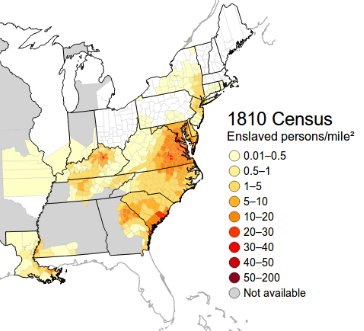

In the years following Hammon’s return, his proclaimed homeland changed dramatically. As the colonists felt the increasingly heavy hand of the English monarchy, more and more Massachusetts men began to realize the hypocrisy inherent in slavery. Leaders like John and Samuel Adams who were coming of age during that time rejected the institution entirely, by the time of the War for Independence the state was leading the world in progress towards emancipation, earning the honor of being the only state to have totally abolished slavery by the time the first census was completed in 1790—achieving legal emancipation 43 years before England followed suit.15

In fact, Massachusetts’ push towards liberty signaled a major shift in the Northern states concerning slavery. All of the New England states, as well as New York and New Jersey, had passed laws for either the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery by 1804. This directly translated into a rapid increase of manumissions, and from 1790 to 1810 the number of free blacks in America increased from 59,466 to 108,395, displaying a growth rate of 82%. The next decade saw that number expand another 72% to 186,446.16

The 1810 census documented that the total population of those states—Massachusetts (Maine included), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey—stood at 3,486,675.17 This was approximately 48% of the total population, slave and free, of the United States at that time. Although not entirely free of slavery due to the gradual emancipation laws in states such as New York and New Jersey, the total percentage of the population waiting for emancipation was only 0.9% in those states.

The 1810 census documented that the total population of those states—Massachusetts (Maine included), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey—stood at 3,486,675.17 This was approximately 48% of the total population, slave and free, of the United States at that time. Although not entirely free of slavery due to the gradual emancipation laws in states such as New York and New Jersey, the total percentage of the population waiting for emancipation was only 0.9% in those states.

In fact, by 1804 nearly half of America had succeeded in passing laws for the abolition of slavery, and only six years later they had been 99% effective in accomplishing that goal. Nowhere else in the world was anywhere close to what those Northern States had succeeded in doing.

So, what happened to Briton Hammon upon returning home? Unfortunately, the historical record is extremely sparse. It seems likely that General Winslow assisted in the production of Hammon’s Narrative, as the publishers, John Green and Joseph Russell, worked for the English government as the, “appointed printers to the English commissioners.”18 Suggesting that Winslow, with his extensive government connections, might have recommended the book to them or offered it to them first, instead of going to other prominent Bostonian or New England printers.

Two years after his book was published, records suggest that Briton married a long-standing member of the inter-racial First Church of Plymouth.19 After Gen. Winslow passed away in 1774, Briton seemingly was passed to Winslow’s sister and brother-in-law, the Nichols family. A certain “Briton Nichols” appears at this time indicating that Hammons took the name of his new masters. When the War for Independence broke out, however, Briton served four different times from 1777 to 1780 in Washington army, eventually winning his freedom and heading a family of three by the time of the first census.20

While there are many questions remaining to be answered about the remarkable life of Briton Hammon (and even more concerning his likely second round of adventures as Briton Nichols), his place as the first printed black prose author in America (and likely the world) deserves to be remembered. From slave to soldier, imprisonment to independence—Briton’s life is a valuable part of the American story. We ought to heed his words and, “Magnify the Lord…and let us exalt his Name together!”21

Endnotes

1 Frances S. Foster, “Briton Hammon’s ‘Narrative’: Some Insights Into Beginnings,” CLA Journal 21, no. 2 (1977): 179; “Briton Hammon,” Rayford Logan and Michael Winston, eds., Dictionary of American Negro Biography (New York: Norton, 1982), xxx.

2 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 3, here.

3 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 6, here.

4 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 6-7, here.

5 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 7, here.

6 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 7, here.

7 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 11, here.

8 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 12, here.

9 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 13, here.

10 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 14, here.

11 Maria Bryant, Genealogy of Edward Winslow of the Mayflower and His Descendants, From 1620 to 1865 (New Bedford: E. Anthony & Sons, 1915), 37.

12 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 13, , here.

13 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 12, here.

14 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 14, here.

15 The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge for the Year 1858 (Boston: Crosby, Nicholas, and Company, 1858), 214.

16 Joseph Kennedy, Preliminary Reports on the Eighth Census, 1860 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1862), 7.

17 Aggregate Amount of Each Description of Persons Within the United States of America, and the Territories Thereof (Washington: 1811), 1.

18 Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America (Worchester: Isaiah Thomas, Jr., 1810), 245, here.

19 Robert Desrochers, “‘Surprizing Deliverance’?: Slavery and Freedom, Language, and Identity in the Narrative of Briton Hammon, ‘A Negro Man,’” Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic, edited by Carretta Vincent and Gould Philip (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 168.

20 Robert Desrochers, “‘Surprizing Deliverance’?: Slavery and Freedom, Language, and Identity in the Narrative of Briton Hammon, ‘A Negro Man,’” Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic, edited by Carretta Vincent and Gould Philip (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 168.

21 Briton Hammon, A Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings and Surprizing Deliverance of Briton Hammon, A Negro Man, Servant to General Winslow, Of Marshfield in New England (Boston: Green & Russell, 1760), 14, here.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!