We have closed yet another school year – America’s 363rd since the passage of its first public education law. Many changes in education have occurred over the past four centuries; this report will focus on the current state of education in America.

Americans & Education

Americans cherish education. Jesus said: “Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” (Matthew 6:21). We spend over $470 billion each year on education; therefore, judging by the amount of “treasure” we invest in education, it must be dear to our hearts. Sadly, however, current statistics demonstrate that Americans are not getting a good return on their investment.

American students now regularly finish at the bottom in international competitions in math and science. Recent international testing found that American elementary students performed above average, junior high students at average, and high school students below average. This sequence of results prompted one observer to remark: “The longer US students stay in school, the less they seem to know.”

America’s education system has become so substandard that it actually prevents many students from entering post-graduate work. As national columnist Thomas Sowell confirms: “For years, most of the PhDs awarded by American universities in mathematics and engineering have gone to foreigners. We have the finest graduate schools in the world – so fine that our own American students have trouble getting admitted in fields that require highly trained minds.”

Despite the fact that America far outspends other nations on education, our students are outperformed by students from Poland, the Slovak Republic, Czechoslovakia, Iceland, China, Taiwan, Canada, Korea, Wales, and many other nations. America currently has one of the poorest outcomes per education dollar spent among all industrial nations.

The performance of American education is now so poor that the US Department of Education has concluded:

The educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a People. . . . If an unfriendly power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war. As it stands, we have allowed this to happen to ourselves.

What has caused the current problems with American education? Three significant factors will be examined in this report: (1) the current philosophy of education; (2) curricular content; and (3) teacher competency.

(Addressing this third category may offend some, but as Jesus noted in Luke 6:40: “Every student, when he is fully trained, will be like his teacher.” It is therefore appropriate to examine whether academic scores are falling because students are becoming like their teachers.)

Changing Philosophy of Education

Unbeknown to most Americans, in the last few years the philosophy of education has been radically transformed in basic subjects such as reading, grammar, and math.

Math

In recent months, a controversy has emerged in Massachusetts; many shocked parents have become aware that teaching math is no longer the top priority for math teachers. Written priority #1 in the new standards for math class is to teach “respect for human differences” and “live out the system-wide core value of ‘respect for human differences’ by demonstrating anti-racist/anti-bias behaviors.” Written priority #2 is “problem solving and representation – students will build new mathematical knowledge as they use a variety of techniques to investigate and represent solutions to problems.”

The primary purpose of math no longer is the teaching of math skills (i.e., learning to use fractions and integers, or doing multiplication and division); it is now viewpoint inculcation. When challenged as to the source of this new philosophy, school officials pointed to the “Principles and Standards for School Mathematics” from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM).

A stark example of this new math philosophy is exhibited in the recent textbook that some have dubbed “rain-forest algebra.” In that 800+ page text, not a single question on math was asked until page 107. The first 107 pages were dedicated to coverage of Maya Angelou poetry, competitive chili cook-offs, the Dogon tribe of West Africa, etc. In fact, the questions in that math book included: “What role should zoos play in today’s society?”; “What other kinds of pollution besides air pollution might threaten our planet?”; and “The topic for the essay this year is ‘Why should we save an endangered species?’”

A US Senator correctly summarized the effect of such texts: “This new mush-mush math will never produce quality engineers or mathematicians who can compete for jobs in the global market place. In Palo Alto, California, public school math students plummeted from the 86th percentile to the 56th in the first year of new math teaching. This awful textbook obviously fails to do in 812 pages what comparable Japanese textbooks do so well in 200. The average standardized math score in Japan is 80; in the United States it is 52.”

Grammar

Just as the national council of math teachers has changed its emphasis, so, too, has the National Council of English Teachers. Claiming that providing grammar instruction, and teaching fundamental skills such as diagramming sentences, only bores students and turns them off to writing, such training was dropped several years ago. The result? A recent national study revealed that a meager one-fourth of students can now write at a proficient level – and only 1 percent can write at an advanced level.

Reading

In reading, national educational groups and teaching professionals demanded that phonics be dropped and whole-language reading be adopted instead. Scores plummeted; in fact, they tumbled so far that the California Board of Education eventually took what one national newspaper described as “the drastic step” of re-adopting phonics – of going back to what had worked for generations. Reading scores have since shown some recovery, but millions of students have incurred lasting academic handicaps in the meantime.

Encouraging Achievement

The new philosophy of education also opposes any competition that recognizes student achievement. As a result, many schools no longer post honor rolls or exemplary work on bulletin boards. Also disappearing from local schools are publicly graded events such as spelling bees as well as other academic competitions. As one elementary principal explains: “I discourage competitive games at school. They just don’t fit my worldview of what a school should be.”

Many traditional educational practices no longer fit the new “worldview of what a school should be” – including homework. Education specialists amazingly claim that doing away with homework will “give kids ownership over their education.”

The use of red ink also does not fit the new educational worldview; and in schools from New York to Alaska, red ink is now on the educational blacklist. Explains a Massachusetts teacher: “If you see a whole paper of red, it looks pretty frightening. Purple stands out, but it doesn’t look as scary as red.” A Florida teacher agreed: “I do not use red; red has a negative connotation, and we want to promote self-confidence. I like purple. I use purple a lot.” Color consultants concur: “Red is a bit over-the-top in its aggression.”

Of course, that is just the opinion of teachers and educational specialists; then there is the opinion of a student who voiced the common sense that the experts seem to lack: “I hate red. But because I hate it, I want to work harder to make sure there isn’t any red on my papers.”

School Discipline

Under the new educational worldview, students with the worst behavioral problems are protected from any accountability so long as they also have certain academic so-called weaknesses. For example, a Virginia student brought a loaded gun to school – and bragged about it – but went unpunished because he had been diagnosed with a “weakness in written language skills.” Similarly, a Georgia student repeatedly urinated on his classmates, but because of a similar “diagnosis,” he could not be punished. In Pennsylvania, a student set fire to a school cafeteria; upon being disciplined, he filed and won a federal lawsuit against the school for violating his rights. And in Oklahoma, a public school suspended nearly all of the sixth-grade class for disruptions and quasi-riots. The principal ruefully estimated that teachers now “spend 85 percent of their time reprimanding students.”

Since schools cannot punish the real offenders, they apparently go after whomever they can punish. For example, a 13- year old was recently ordered suspended for 10 days from a Florida school for committing a Level 4 offense – the most serious level. The offense? He “assaulted” and threatened others with a “weapon” (he shot a rubber band). In another school, two kindergartners were sent home for “assault” with “weapons” (they had pointed their fingers at each other and said “bang!”).

Viewpoint Indoctrination

While core academics, discipline, and red ink do not fit the new “worldview of what a school should be,” viewpoint indoctrination does. For example, the largest teacher’s group in America (the National Education Association) aggressively promotes what it calls “diversity education”; it has been relatively successful in passing state laws mandating such teaching at all grade levels.

In compliance with such a law, schools in one state held a “Week of Diversity” in which outside speakers made 82 presentations to students. Of the 82 presentations, 14 were pro-homosexual; 11 were pro-left, urging support for communist Cuba, guerilla forces in Columbia, etc.; 17 promoted animal rights, vegetarianism, and radical environmentalism; and 5 were anti-law enforcement. A week of academic instruction was sacrificed in order to indoctrinate specific viewpoints.

Another clear indication of viewpoint indoctrination was evident in the NEA lesson-plan distributed nationally to teachers following the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The lesson taught that no group was responsible for the attacks and that instead, teachers should discuss “historical instances of American intolerance” in order to avoid “repeating terrible mistakes.” Unfortunately, the new educational “diversity” regularly expresses itself in anti-Americanism.

Apparently, many professional educators now want to be known more for introducing something “new” or “innovative” than for the success of the students they teach. Consequently, academics take a backseat as students become classroom guinea pigs for a new generation of educrats. Peter Murphy, a New York educational consultant, properly asks: “How many more years of declining scores will it take for the school committee and state officials to put a stop to this educational malpractice on schoolchildren?”

Evangelists for a New Worldview

Who has been behind these radical changes? A new breed of professional educators – working through two primary vehicles: teachers’ colleges, and teachers’ unions.

Concerning the former, a professor writing in the Texas Education Review charges: “Schools of education have been transformed into agencies of social change with mandates to achieve equality at all costs. Colleges of education no longer believe that knowledge should be the center of the educational enterprise. Colleges of education do not serve the interests of children or parents. Instead, they serve the interests of an educational bureaucracy by pushing the growth of the profession, protecting it from competition, and discouraging outside scrutiny.”

Anyone who doubts the accuracy of these charges need only review the resolutions passed at the annual NEA conventions. Those resolutions routinely avoid academic issues and instead advocate the teaching of social positions that most Americans oppose. For example, at recent conventions, NEA educators have passed resolutions calling for schools to encourage:

• Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered people

• Globalism and nuclear disarmament

• The United Nations and the International Court of Justice

• School-based health clinics that promote abortion

• National healthcare, population control, and Earth Day

• Multi-culturalism and diversity education

• Pre-K-12 AIDS programs (yes, pre-K:

AIDS education for three and four-year-olds!)

While the NEA supports these issues, it also opposes many, including:

• Competency testing of teachers

• Standardized testing to evaluate students, teachers, or schools

• Educational choice or competition in education

• Homeschooling

• “Homophobia” (the belief that homosexuality is wrong or that marriage should

be between a man and a woman)

• A moment of silence to open the school day

Where is the emphasis on academics? Conspicuously absent. As one national columnist queried: “Since the National Education Association describes itself as ‘America’s largest organization committed to advancing the cause of public education,’ is it not fair to ask why it spends so much of its energy on political issues having little to do with education?” That point was not lost on all NEA delegates (some teachers do oppose the current direction of the NEA, but they are in a clear minority); in fact, one such delegate – after seeing the resolutions passed at the convention – lamented: “We’re the National Education Association, not the National Everything Association.”

Results of this Philosophy

The academic weaknesses of this new educational worldview are statistically measurable in a number of curricular areas.

Civics & Citizenship

According to current studies, after twelve years of school, only a meager 26 percent of students have enough preparation in civics to make informed choices at the polls. Imagine! American education currently is producing only one in four students capable of informed voting!

Furthermore, only 9 percent can name two ways that society benefits from the active participation of its citizens. And while 80 percent of students can name the winner of “American Idol,” only half know the political affiliation of their own state governor; and less than 10 percent can name both of their US Senators. Our educational system simply no longer produces civically prepared, well-informed citizens.

Geography

Thirty-four percent of students know that the island on the “Survivor” television program was in the South Pacific, but only 30 percent can find New Jersey on a United States map; 50 percent of students cannot find New York and 30 percent cannot locate the Pacific Ocean. And although Americans have been involved in a lengthy war in Iraq, only 13 percent of students can find Iraq on a map.

Reading & Math

By the fourth grade, only 30 percent of students are competent in reading and math; the number is much lower by the eighth-grade level; and by the end of high school, less than one fourth of college-bound students have the basic academic knowledge necessary to succeed in college (one can imagine how much worse it is for non-college-bound students).

History

Only one in ten high school seniors is proficient in American history. Why? Because the new educational worldview emphasizes behavior rather than knowledge. Consequently, the recent history standards proposed by the State of New Jersey excluded the Pilgrims and the Mayflower, and George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson. This trend has been growing for a decade, and a number of states now teach what is called “The Twentieth Century Model” under which high school students are taught only 20th century history. According to one astute educational observer, in American schools “history is not dumbed down, but erased.”

Consequently, 70 percent of fourth-graders thought that Illinois, Texas, and California were part of the original 13 colonies; and 60 percent had no idea why the Pilgrims came to America. And when students were asked to identify “Memorial Day,” the most common answer was, “The day when the pools open.” Recent testimony before a congressional hearing correctly concluded: “We are raising a generation of people who are historically illiterate.”

Ignoring the Obvious

The above academic results have been revealed primarily through independent surveys of students rather than through academic testing conducted by educators. Why? Recall the position of the teachers’ unions? “The [NEA] opposes the use of standardized tests when . . . results are used to compare students, teachers, programs, schools, communities, and states.”

Professional educators oppose testing and argue that it is not an accurate measure of what students really know. Of course, they offer no other proposal for measuring student knowledge; they just don’t like testing that exposes academic weaknesses, and thus could lead to teacher accountability.

Despite the opposition of educators to testing, legislators are beginning to demand it – but they are not liking what they find. For example, in Virginia, students were required to pass a state exam, but when 93 percent of students failed the test, the requirement was dropped.

In other states where legislators require testing, educators find ways to evade the purpose of the tests by simply lowering the bar. For example, in Florida, 13,000 high school seniors failed to pass the state exit test. (Originally many more had failed, but the passing grade was lowered to only 40 percent to reduce the number of failures to just 13,000!) Similarly, so many students were having difficulty passing the state’s required history test that the passing score was lowered to a mere 23 out of 100 – that is, students can get three out of four history answers wrong and still pass the test!

So what do educators propose as a solution for these high failure rates? According to national columnist Thomas Sowell: “The National Education Association – the biggest teachers’ union in the country – is urging that an extra year be added to high school for those students who fail to meet the standards for graduation. In other words, when educators fail to educate for 12 years, the 13th year will be the charm.” Too many students now spend their educational career in what one commentator described as “legally enforced incarceration in government buildings that are euphemistically called schools.”

Many of the good public school educators have come to recognize that public schools are no place to educate their own children. In fact, public school teachers are twice as likely as other parents to place their own children in private schools – including 44 percent of public school teachers in Philadelphia, 41 percent in Cincinnati, 39 percent in Chicago, etc. Why do so many public school teachers place their own children in private schools? A common answer given by these educators is: “Private and religious schools impose greater discipline, achieve higher academic achievement, and offer overall a better atmosphere.”

A Call for Results – and an Unexpected Response

Educators unreasonably assert that the current problems in education can be fixed only through more money and higher teacher salaries. Most citizens see a different problem; as Star Parker of the Coalition on Urban Renewal and Education pointedly notes: “Businesses that face competition deliver more and more for less and less. Monopolies deliver less and less for more and more. What else can we expect from the NEA and government school monopoly than claims that spending is the alleged answer for everything?”

The public is starting to deafen to the incessant and unceasing clamor for more money and is instead beginning to demand more bang for the buck. As a result, laws are now being crafted at the state and federal levels that attach school funding to academic performance but because teachers’ jobs may now depend on how well they teach as measured by objective testing scores, some schools and teachers are taking unorthodox steps to ensure that scores remain high: they have resorted to cheating.

For example, on the accountability test in Texas, organized teacher-led cheating was uncovered. What initially alerted investigators to the cheating? An elementary school in Dallas in which students had previously ranked in the bottom 4th percentile in one year, suddenly finished as the second best school in the state the next year. Similar teacher-led cheating has been exposed in Nevada, Mississippi, Massachusetts, Ohio, New York, Michigan, Connecticut, Kentucky, South Carolina, Arizona, and elsewhere. In the classic “end justifies the means” mentality, teachers from the new educational worldview are simply cheating to help bolster testing scores and preserve their jobs.

One testing expert correctly notes: “When you have a system where test scores have real impact on teacher’s lives, you’re more likely to see teachers willing to cheat.” And because the problem of teacher-led cheating is growing rather than shrinking, a whole new industry has sprung up to provide monitoring of

teachers as they administer tests. Perhaps a reporter from the Indianapolis Star best summarized this new trend when he said: “I hope people are aware of the irony of the situation that America now faces. We are talking about how to keep teachers from cheating.”

Teacher Competency

Because the current rash of testing has revealed deep academic weaknesses in students, attention properly has been focused on teachers: why can’t teachers produce students with a grasp of academic basics? There may be many answers, but statistics irrefutably document that one of the causes is a widespread epidemic of academically incompetent teachers.

The federal government’s own National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reports that college education majors have the lowest Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores of any undergraduate major. And the results of the standardized entry exam for students seeking post-graduate degrees reveals that education majors have the second-lowest scores of all majors. And if an education major decides to enter law, the LSAT (the Law School Admission Test) shows that education majors rank at the bottom – 26th out of 29 majors. This is not to suggest that all teachers lack basic academic knowledge; but the fact is undeniable that their profession ranks as one of the lowest in academic competency.

Sadly, once these low-performing education majors become teachers, states demand even less from them. For example, of the 29 states that test teachers, only one requires math teachers to attain the national average in math to be able to teach math; and no state currently requires a teacher to reach the national average in reading in order to teach reading. In many states, a teacher can score in the bottom quarter in math and reading and still be rated competent to teach those subjects. In the current system, it is relatively easy for underperforming teachers to be certified.

Once certified, many states require teachers to participate in some form of continuing education to stay certified. The concept is reasonable on paper, yet teachers in Illinois get professional development credits for taking Tai Chi classes, learning to give massages, and for gambling at racetracks. For gambling at racetracks? Reporters who investigated that class reported: “The afternoon of gambling was part of a two day, 15-credit hour class called ‘Probabilities in Gaming.’ The teachers learned how to read the racing guide and calculate the payout. Before placing their bets, they discussed betting odds and how to pick a winner, such as considering the age of the horse and the days since his last race. . . . The professor who taught this course claimed that a day at the race track gets teachers excited about math.”

Regrettably, when groups clamor for “certified” teachers, today the phrase has become relatively meaningless. In fact, home-schooled students average 30 to 37 academic points higher than their counterparts in public schools on the same academic tests, even though less than 14 percent of homeschool “teachers” (i.e., moms) are certified. Similar results are seen in private schools, where the majority of teachers are not certified yet produce academic results well above their counterparts in public schools. Public school certification is no longer any assurance of quality.

Teachers Oppose Accountability

Not only are teachers’ scores collectively among the lowest of all groups in the nation, but teachers’ groups stridently resist efforts to raise the bar. For example, in Massachusetts, suit has been filed against the testing of math teachers, claiming that such testing is “unfair, illegal and discriminatory.” As national commentator Thomas Sowell points out, teachers appear to be saying, “We know our algebra and geometry so well that we don’t want anybody testing us to find out. . . . What makes this huffy response especially ironic is that over half the applicants for teaching jobs in Massachusetts a couple of years ago failed a very simple test. Here is a chance for Massachusetts educators to vindicate themselves and prove their critics wrong. Yet somehow they are passing up this golden opportunity.”

Similarly, the Philadelphia Inquirer reports that in Philadelphia, “half of the district’s 690 middle school teachers who took exams in math, English, social studies and science in September and November failed.” Notice: half of the currently-certified teachers failed the relatively easy state teaching test but are still teaching in the classroom! Why have so few heard about this? Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell explains, “releasing the data could subject teachers to humiliation.” Great! – permanently impair students rather than embarrass incompetent teachers!

This “circle the wagons” mentality to defend failure is predictable, though illogical. Chester Finn of the Fordham Foundation seemed to express the thoughts of most rational Americans when he stated: “Pressure to perform is not a bad thing. Educators have been spared it for so long that they’ve forgotten that it’s part of life in almost every other line of work. I mean, bus drivers are under pressure not to crash their buses. Prison guards are under pressure not to let their prisoners escape. Doctors are under pressure not to let their patients die. Lawyers are under pressure to win their lawsuits. Everybody is under pressure

in their job. Educators have had this curious sort of charmed life in which results don’t matter. This is just nuts.”

Dismissing Incompetent Teachers

So why not just get rid of incompetent teachers? Because under the current tenure rules, getting rid of just one teacher can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in expenses and years of time. For example, it took three years to get rid of a teacher who engaged in brawls with students, was unable to control her classrooms, and who changed her name to “God”; it took four years to get rid of a teacher who refused to follow a lesson plan and who swore at her students; it took five years to get rid of a teacher who showed first-graders a R-rated movie; and it took eight years and $300,000 to get rid of a teacher who refused to answer students’ questions in class.

In Los Angeles, it is so difficult to get rid of incompetent teachers that in that district of 35,000 teachers, over the span of a decade the district was able to get rid of only one incompetent teacher. And of the 300,000 teachers in California, only 227 were dismissed over that same decade – only one-tenth of one percent were dismissed as incompetent, despite the fact that national studies find as high as 18 percent of current teachers are incompetent. One school official lamented, “It takes longer to fire a teacher than to convict a murderer.” A state legislator agreed: “Unless you’re molesting children or robbing banks, you can’t be fired.”

The story is the same in state after state – all because of tenure. (Currently, all states provide, and about 80 percent of teachers have been awarded, tenure.) A Florida group properly notes that tenure “creates an environment where there is simply no incentive to be a good teacher. . . . Serving time is what is rewarded, not teaching excellence.” A California school board member agrees: “Good teachers do not need tenure. Poor or incompetent teachers use it to protect their jobs.”

So why do educational unions fight so hard for teacher tenure, and then fight so hard to keep incompetent teachers from being dismissed? As one Kansas legislator explained: “Unions fight for poor-performing teachers because then the schools hire more remedial teachers. More teachers equals more money for the union. . . . They want as many teachers as possible making as much money as possible. . . . It means more teachers, more pay, more money for the union.”

Summary

The successful philosophy of education that characterized America for centuries clearly has undergone a radical revolution in recent years. Many are unaware of the changes, and others are simply complacent about them. Yet, every citizen should be concerned and informed about the condition of education. As educator Noah Webster long ago warned:

The education of youth should be watched with the most scrupulous attention. . . . [I]t is much easier to introduce and establish an effectual system . . . than to correct by penal statutes the ill effects of a bad system. . . . The education of youth . . . lays the foundations on which both law and gospel rest for success.

It is our responsibility as citizens not only to protect the proven educational philosophy that made and has kept America great but also to do everything that we can to transmit a successful educational philosophy to future generations, just as our forebears did throughout the first four centuries of American education.

A Solution

What is the solution for many of the education problems that America now faces? Much of the answer may be found in a new DVD we have just introduced on the national market: Four Centuries of American Education. (This new work was entered into national competitions with works from groups such as CBS, HBO, Paramount, Fox, etc., and won the top award in its class!)

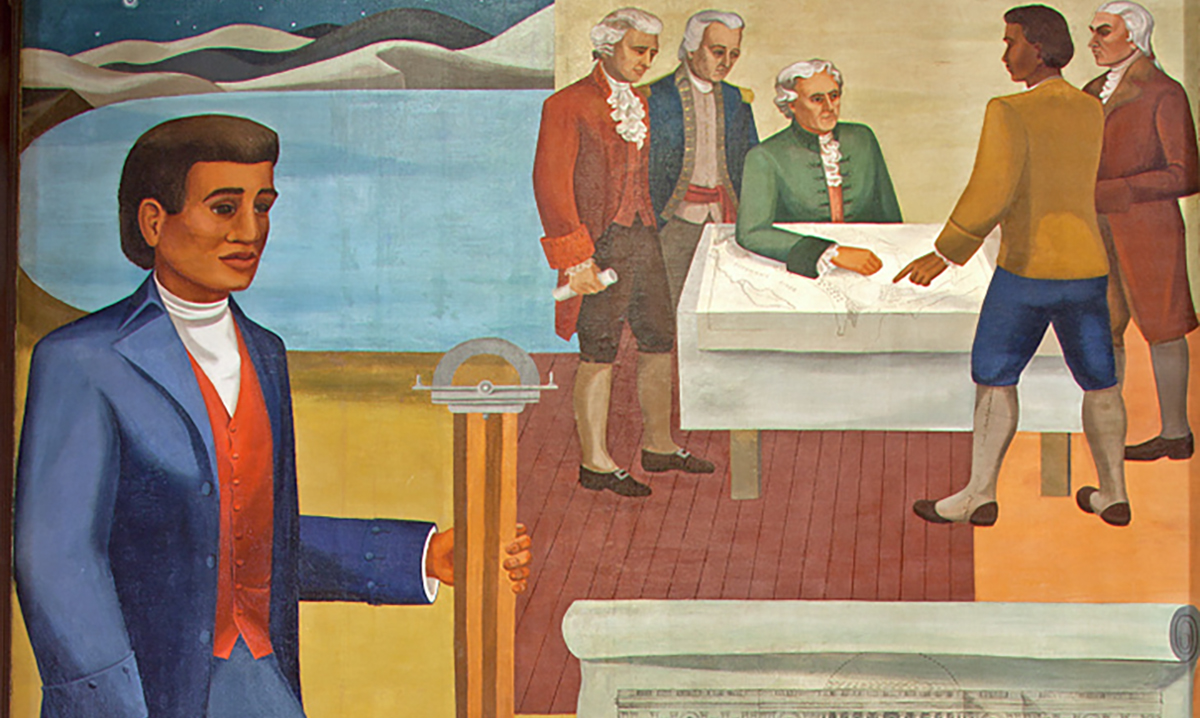

Four Centuries of American Education examines education both past and present. It presents not only many of America’s greatest textbooks but also its greatest educators from Benjamin Rush and William McGuffey to Emma Willard and Booker T. Washington. It documents what long made America a world leader in education, what caused the change, and what can be done to re-attain genuine educational achievement.

Four Centuries of American Education is an excellent tool for educating others about our educational system and is appropriate for use at home or school, or in churches or civic clubs. The remarkable information in this work will both challenge and inspire you.

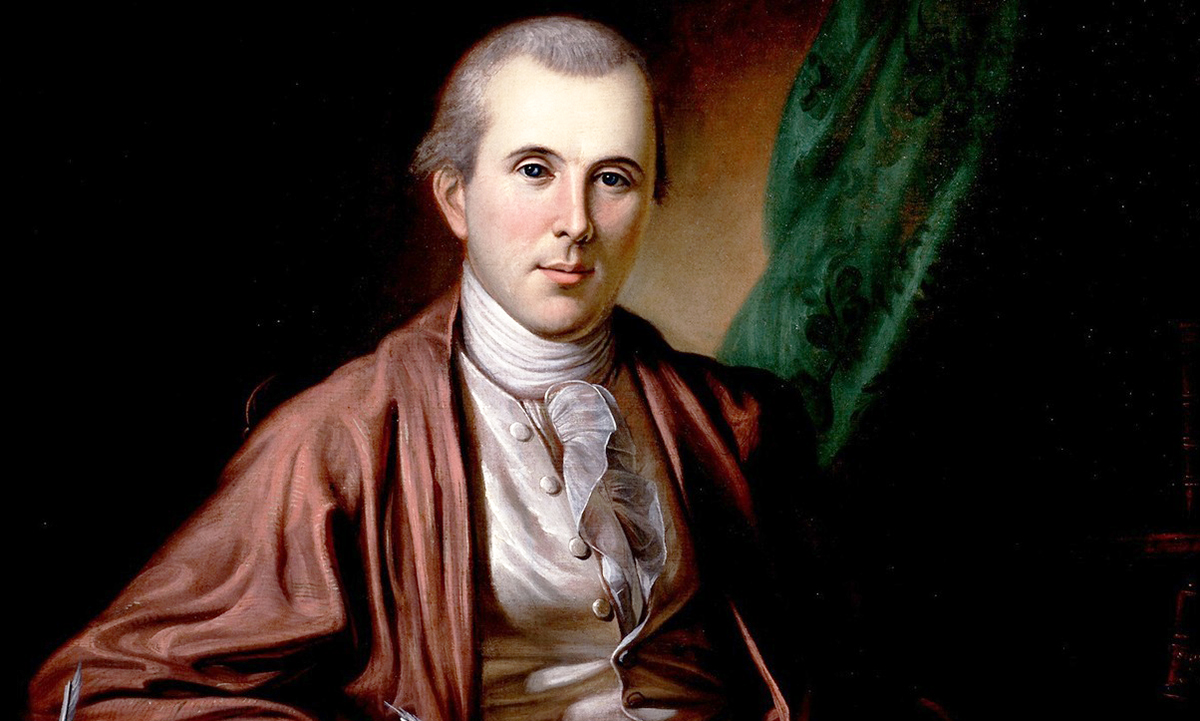

WallBuilders mission is “presenting America’s forgotten history and heroes, with an emphasis on our moral, religious, and constitutional heritage.” Two of our great heroes largely forgotten today include Dr. Benjamin Rush (signer of the Declaration, who John Adams considered as one of America’s three most notable Founders 1) and Elias Boudinot (pictured to the right; president of the Continental Congress and a framer of the Bill of Rights in the first federal Congress).

WallBuilders mission is “presenting America’s forgotten history and heroes, with an emphasis on our moral, religious, and constitutional heritage.” Two of our great heroes largely forgotten today include Dr. Benjamin Rush (signer of the Declaration, who John Adams considered as one of America’s three most notable Founders 1) and Elias Boudinot (pictured to the right; president of the Continental Congress and a framer of the Bill of Rights in the first federal Congress). Elisha was active in the patriot cause 3 and served as a Justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey. 4 He was anti-slavery 5 and also worked to help prepare men for the Gospel ministry. 6 His wife was active in helping the poor and needy in their community. 7

Elisha was active in the patriot cause 3 and served as a Justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey. 4 He was anti-slavery 5 and also worked to help prepare men for the Gospel ministry. 6 His wife was active in helping the poor and needy in their community. 7

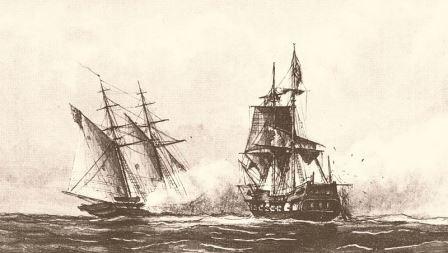

The Barbary Powers Wars were the first wars officially declared against America following our victory in the War for Independence.

The Barbary Powers Wars were the first wars officially declared against America following our victory in the War for Independence.  There is here an order of priests called the Mathurins, the object of whose institutions is the begging of alms for the redemption of captives. About eighteen months ago, they redeemed three hundred, which cost them about fifteen hundred livres [$1,500] apiece. They have agents residing in the Barbary States, who are constantly employed in searching and contracting for the captives of their nation, and they redeem at a lower price than any other people can.

There is here an order of priests called the Mathurins, the object of whose institutions is the begging of alms for the redemption of captives. About eighteen months ago, they redeemed three hundred, which cost them about fifteen hundred livres [$1,500] apiece. They have agents residing in the Barbary States, who are constantly employed in searching and contracting for the captives of their nation, and they redeem at a lower price than any other people can.  When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, he decided that it was time to take military action to end the two-decades-old unprovoked Muslim terrorist attacks against Americans.

When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, he decided that it was time to take military action to end the two-decades-old unprovoked Muslim terrorist attacks against Americans.  Shortly after President James Madison took office, he became engulfed in the War of 1812. With America preoccupied in a second war against the British, Algerian Muslim terrorists again began attacking Americans. But upon concluding the war with the British, President James Madison dispatched the American military and warships against three Muslim nations: Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli.

Shortly after President James Madison took office, he became engulfed in the War of 1812. With America preoccupied in a second war against the British, Algerian Muslim terrorists again began attacking Americans. But upon concluding the war with the British, President James Madison dispatched the American military and warships against three Muslim nations: Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli.

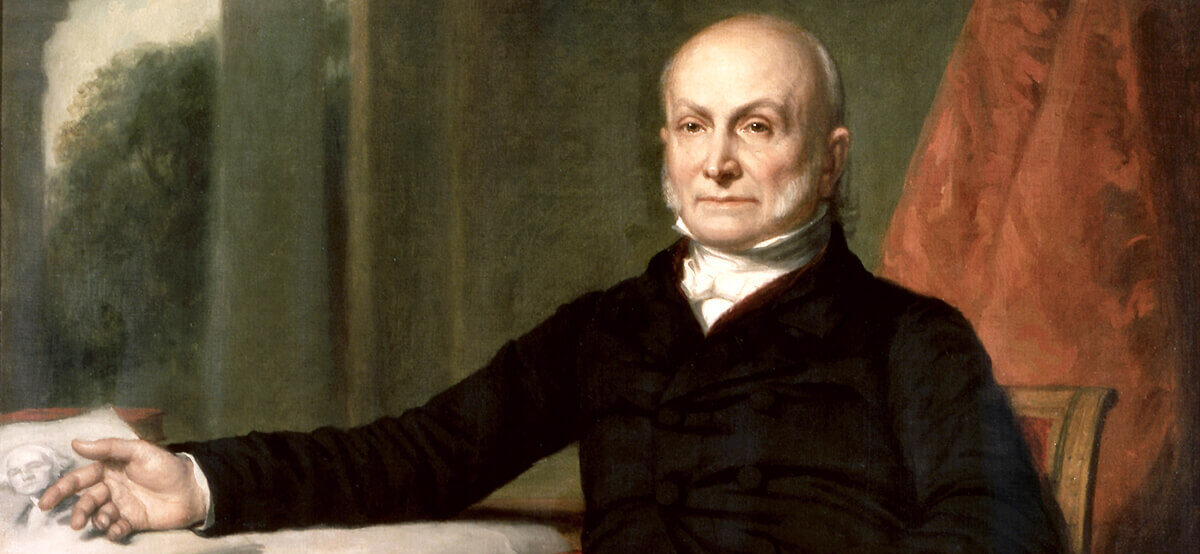

If you answered John Quincy Adams (the earliest serving President to have a photograph taken of him), then you were right!

If you answered John Quincy Adams (the earliest serving President to have a photograph taken of him), then you were right!

Shortly after John Quincy’s death on the floor of the House of Representatives in 1848, those nine letters were quickly printed as a book for all of America’s youth,

Shortly after John Quincy’s death on the floor of the House of Representatives in 1848, those nine letters were quickly printed as a book for all of America’s youth,