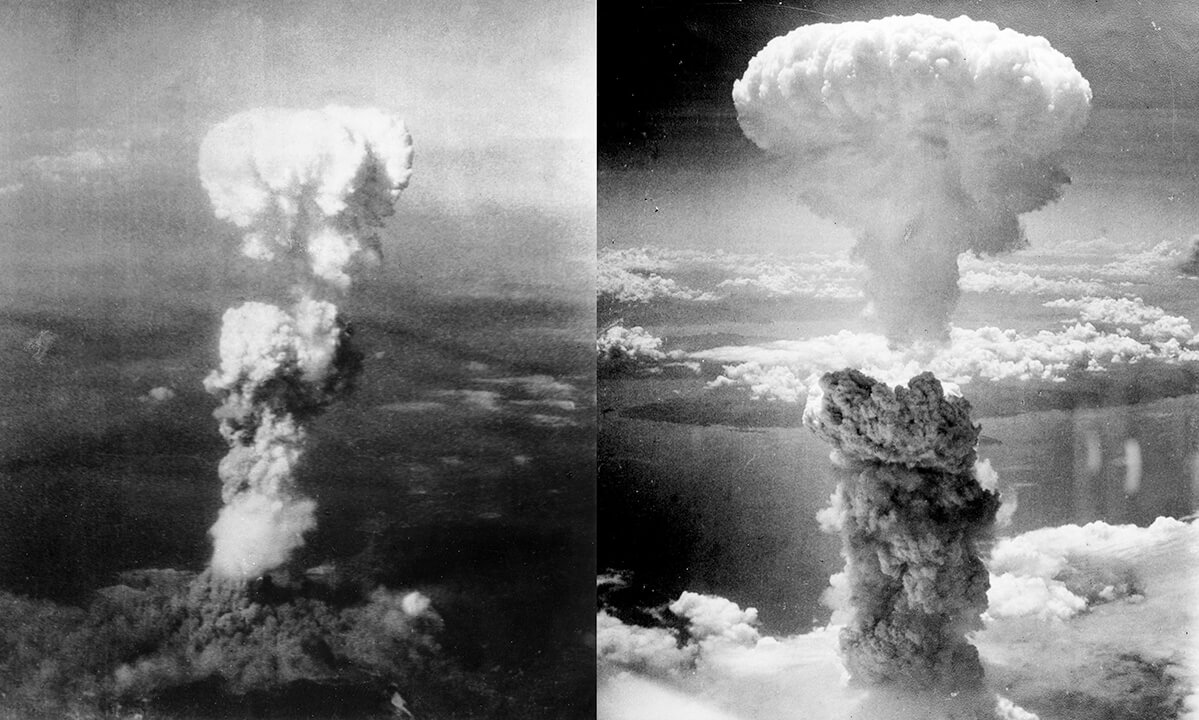

On May 27, 2016, President Obama visited Hiroshima – the only American president to do so since the city was hit by an atomic bomb on August 6, 1945. That bomb hastened the end of World War II and helped halt further war deaths in the Pacific Theater beyond the 20 million lives already lost. 1

Both supporters and opponents scrutinized the president’s speech to see whether he would issue any direct apology for America’s having dropped atomic bombs, thereby extinguishing between 200,000 and 250,000 Japanese lives. 2 The president carefully stayed on script and delivered no overt apology, but even the mainstream media did not miss the fact that by simply appearing at Hiroshima he was issuing an indirect apology:

A majority of Japanese people view the atomic bombings as inhumane attacks — war crimes for which the United States has never been punished. . . . Hiroshima is a decidedly one-sided location; the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Japan. At this setting one country is victim, the other assailant. 3 Washington Post

No American president has visited Hiroshima or Nagasaki in the 71 years since the attacks because of concerns the trip would be perceived as an apology for the two bombings that helped bring an end to World War II. 4 ABC News

The president wrote in a Washington Post op-ed in late March, “As the only nation ever to use nuclear weapons, the United States has a moral obligation to continue to lead the way in eliminating them.” “Moral obligation”? . . . Why would America assume a “moral obligation” if not because the nation was guilty of some ill-advised, even immoral, action? 5 US News

A visit would inevitably be construed by many as a de facto U.S. apology. . . It would be seen as vindication for Japanese claims of victimization, encouraging those in Japan who still deny responsibility for a war of aggression. . . . The goal of a presidential visit to the nuclear bombing sites is to finally come to terms with the morally difficult decisions made in World War II.6 The Diplomat

A Moral Revolution?

The media recognized that the issue of morals was inseparable from any official visit to Hiroshima, and as expected, the president did address that issue in his speech. According to President Obama:

The scientific revolution that led to the splitting of an atom requires a moral revolution as well. That is why we come to this place [Hiroshima]. We stand here, in the middle of this city, and force ourselves to imagine the moment the bomb fell. We force ourselves to feel the dread of children confused by what they see. We listen to a silent cry. We remember all the innocents killed across the arc of that terrible war, and the wars that came before, and the wars that would follow. Mere words cannot give voice to such suffering, but we have a shared responsibility to look directly into the eye of history and ask what we must do differently to curb such suffering again. Someday the voices of the hibakusha [survivors of the bombings] will no longer be with us to bear witness. But the memory of the morning of August 6th, 1945 must never fade. That memory allows us to fight complacency. It fuels our moral imagination. It allows us to change. . . . We can tell our children a different story – one that describes a common humanity; one that makes war less likely and cruelty less easily accepted. We see these stories in the hibakusha [survivors of the bombings] – the woman who forgave a pilot who flew the plane that dropped the atomic bomb, because she recognized that what she really hated was war itself. 7

Notice the interesting moral perspective communicated by the president. He asks that we imagine the suffering in Hiroshima – the dread of the children; the voice from the victims of the bombings; the silent cry. He also praises the forgiveness of the Japanese woman who forgave the American pilot who dropped the bomb. All of these statements point us toward the Japanese viewpoint. Human and losses are always tragic, but viewing them with a factually-accurate perspective is crucial.

Take for example, the woman who forgave the Americans. Did she also forgive her Emperor for the treacherous and unprovoked surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that killed 2,403 Americans and wounded 1,178, 8 thus bringing America into the war? Did she forgive Japan for declaring war on America when we were working diligently to stay out of the war and be uninvolved? Did she forgive the Japanese military leaders for keeping the war against America going long after the rest of the world had surrendered? America would not have dropped atomic boms without these three Japanese-initiated events. So why are the Americans the transgressors who need to be forgiven?

And empathizing with children is important. But shouldn’t we likewise imagine the cries of the American children whose fathers were mercilessly slaughtered by the Japanese in the Bataan Death March, or killed in the many other Japanese atrocities that in both brutality and scope parallel the war crimes perpetrated by the Nazis in Europe? Throughout the War Japan engaged in active genocides, including against its Asian neighbors in Korea, Manchuria, the Philippines, and China. (It is estimated that in China alone some ten million innocents were exterminated by the Japanese. 9) Japan’s military philosophy was barbaric with no respect for human life.

For example, Japanese officers reportedly held a competition to see which officer could kill 100 people with his sword first, with a runoff to determine a winner. 10 They callously burned alive American prisoners after capture. 11 Others had their heads smashed in with sledgehammers. 12 There are always brutalities and atrocities in war. But as historian Mark Felton termed it, with the Japanese “murder [was] the rule rather than the exception.” 13 There is a reason that after the war, war-crime trials were held in Japan and not just Germany.

President Obama’s acknowledgment that Hiroshima calls for a moral revolution is a common view among Progressives, who repeatedly blame America for much of the evil in the world. Even the 2014 study guide for the Advanced Placement Test for high school U. S. History (written by the College Board, headed by Progressive educator David Coleman) told students that “the decision to drop the atomic bomb raised questions about American values.” 14 Following public outrage, the College Board modified that statement to read: “The use of atomic bombs hastened the end of the war and sparked debates about the morality of using atomic weapons.” 15 The change was an improvement, but it still preserved the view that the use of an atomic weapon was symbolic of America’s lack of morality. Other sources echo that belief:

Truman’s decision was a barbaric act that brought negative long-term consequences to the United States. 16

The . . . use of such a weapon was simply inhumane. Hundreds of thousands of civilians with no democratic rights to oppose their militarist government, including women and children, were vaporized, turned into charred blobs of carbon, horrifically burned, buried in rubble, speared by flying debris, and saturated with radiation. 17

The American government was accused [by modern Progressive writers] of racism on the grounds that such a device would never have been used against white civilians. 18

There are many similar claims. But what is missing is the compelling evidence that given what was occurring in Japan at that time, employing the atomic bomb was actually the more moral thing to do. Two categories of proof fully demonstrate this: (1) The reason the atomic bomb was used, and (2) The manner in which it was used. Consider the definitive evidence for each category.

The Reason the Atomic Bomb was dropped on Japan

Interestingly, there are many legitimate parallels between the Japanese military of World War II and ISIS more recently. In addition to the Japanese practices of open beheadings, mass executions, and other grotesque forms of torture intended to generate fear and terror among those they were seeking to subdue and control, they also specialized in suicide bombers. In fact, they leveled more than 2,000 suicide bombing attacks against Americans during the war, resulting in substantial losses of American lives. 19 Also, the Japanese military forcibly took Korean women and used them as sex slaves for their soldiers 20 in a manner similar to what ISIS terrorists do with non-Muslim women.

In World War II, America and the Allied Forces fought simultaneously on both the European and Pacific fronts. But late in the War they focused the bulk of their efforts on the European Theater until Germany and Italy finally capitulated. At that time, Japan, the remaining major Axis power, was losing battle after battle to Allied Forces in the Pacific but still refused to surrender along with their comrade nations.

With the war in Europe ended, Japan and the Pacific became the unitary focus of Allied military action. As American and Allied forces worked closer to Japan in victory after victory, they extended multiple informal opportunities to surrender to Japan before the official surrender declaration from the Potsdam Conference. But Japan rejected all offers. 21 The Allies therefore planned an assault on Japan similar to that which had ended the war in Europe.

They would conduct a D-Day style invasion followed by Allied troops incrementally fighting their way across the island until they finally took complete control, forcing the surrender that all sides knew was inevitable. Significantly, Japanese leaders fully understood that they could no longer win. But they wanted to extract as high a price as possible with their loss. Japanese leaders were defiant, determined to fight to the end regardless of the cost in human lives. As one foreign policy expert explained:

As U.S. forces in the Pacific advanced toward Japan, its people were committing suicide in hordes rather than face capture. Anticipating a land invasion, Japan’s leaders were preparing their people for a fight to the finish, conscripting boys as young as 15 and teaching them how to kill incoming U.S. troops and conduct kamikaze operations. 22

(Notice yet another similarity between the Japanese military and ISIS: training youth for suicide bombing missions.)

The Allies drew up plans for “Operation Downfall” – the code name assigned to the planned invasion of Japan. As part of the preparations, they prepared estimated casualties, calculating the probable loss of lives, both Japanese and Allied.

General Curtis Lemay, commander of the B-29 force that would be central to any invasion of Japan, was informed that the operation would result in at least 500,000 American deaths. 23 A study done for President Truman’s Secretary of War Henry Stimson estimated American casualties at 1.7 to 4 million (including up to 800,000 deaths), and from 5 to 10 million Japanese fatalities, depending on their level of determined resistance. 24 The projections included several million more casualties for other Allied Forces, which included nations such as Great Britain, China, Canada, and Australia. Evaluations thus placed the body count at around 7 million on the low side, to 14 million on the upper end.

President Truman understood the scope of the new atomic weapon at his disposal. But the other nations had no such conception for such a bomb had never been used before. Truman therefore went to extraordinary lengths to warn the Japanese of what was to come if they did not surrender (amazing details on this will be presented shortly). He finally had a choice to make. He could continue fighting with traditional weapons until the Japanese finally surrendered, which was estimated to be another half year, costing millions of lives in the process. 25 Or he could use an atomic bomb, which might result in 100,000 deaths per bomb. These deaths would be tragic but the numbers paled in comparison to the potential loss of millions of lives. The psychological shock of the use of such a weapon should rapidly push the enemy toward an immediate surrender. Given the situation, there was no moral dilemma. Truman chose to save millions of Japanese and Allied lives by using the atomic bomb.

The Manner in which the Atomic Bomb was Used on Japan

Prior to the decision to use atomic bombs, Allied Forces conducted incendiary bombings against Japanese military production areas. The Tokyo bombings of March 9-10, 1945, alone killed 100,000. 26 (Note that this death toll from traditional warfare was higher than that caused by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, or the one on Nagasaki.) Despite the high mortality numbers from traditional warfare, the Japanese not only refused to surrender but actually became more recalcitrant, preparing their people for continued fighting.

Months earlier, on June 15, 1944, the US military launched a bloody but successful weeks-long campaign to recapture the strategic island of Saipan. Located less than 1,500 miles from Tokyo, it provided a base from which Allied bombers could reach Japan and a key location from which to launch an invasion. A 50,000-watt radio station (KSAI) was also constructed there, so Allied bombers could track its radio broadcast waves as a beacon safely back to the tiny island in the middle of the Pacific.

Saipan also became the center of Allied communication. Utilizing the radio station, the US Office of War Information began broadcasting important information and messages directly to the Japanese people, bypassing their fanatical leaders. They also constructed a print shop. Prior to Allied bombings, B-29s dropped 63 million leaflets across Japan, warning citizens about the specific cities that had been targeted for bombing, and urging civilians to flee and avoid those areas. 27 However, Japanese military officials ordered the arrest of any citizen who read the leaflets, or did not turn them into local authorities.

On the other side of the world Allied leaders gathered in Potsdam, Germany, on July 26, 1945, to establish terms of surrender for Japan. The resulting Potsdam Proclamation called for “disarmament and abolition of the Japanese military; elimination of military influence in political forums; Allied occupation of Japan; liberation of Pacific territories gained by Japan since 1914; swift justice for war criminals; maintenance of non-military industries; establishment of freedom of speech, religion, and thought; and introduction of respect for fundamental human rights.” 28 If the Japanese rejected these terms, the result would be “prompt and utter destruction.” 29

The Allies knew that Japanese leaders would say nothing to their people about this offer, so the radio station on Saipan began broadcasting the Proclamation directly into Japan even before it reached Japanese leaders through official channels. And B-29s also dropped 3 million leaflets (see some of these leaflets from the WallBuilders library here) telling the people about the Proclamation. But on July 27, Japan officially rejected the proposal, thus continuing the war. 30

The next day, July 28, bombers dropped one million leaflets over the 35 Japanese cities (including Hiroshima and Nagasaki) targeted for bombing in coming days, urging citizens to evacuate those cities. That leaflet (with its picture of five B-29s releasing their cargo of bombs) specifically warned:

Read this carefully as it may save your life or the life of a relative or friend.

In the next few days, some or all of the cities named on the reverse side will be destroyed by American bombs. These cities contain military installations and workshops or factories which produce military goods. We are determined to destroy all of the tools of the military clique which they are using to prolong this useless war. But, unfortunately, bombs have no eyes.

So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives. America is not fighting the Japanese people but is fighting the military clique which has enslaved the Japanese people.

The peace which America will bring will free the people from the oppression of the military clique and mean the emergence of a new and better Japan. You can restore peace by demanding new and good leaders who will end the war. We cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked but some or all of them will be, so heed this warning and evacuate these cities immediately. 31

Understandably, the crews scheduled to bomb those areas were concerned for their own safety, for the leaflets not only told the Japanese military exactly what was about to occur but also where. Nevertheless, humanitarian concerns for Japanese civilians remained foremost in American thinking, even jeopardizing the lives of Allied pilots and crews.

America specifically avoided bombing the Emperor’s palace or the historic temple area of Kyoto. But after days of bombings, “Japan’s Air Defense General Headquarters reported that out of 206 cities, 44 had been almost completely wiped out, while 37 others, including Tokyo, had lost over 30 percent of their built-up areas.” 32 But despite the increasingly extensive devastation, Japan still refused to surrender.

Bombings alone had proved insufficient to end the war. The only remaining traditional warfare option was a full-scale land invasion of Japan, which could produce the millions of casualties predicted in the various official reports. Facing this prospect, President Truman therefore approved the B-29 Enola Gay dropping the atomic bomb “Little Boy” over Hiroshima. The devastation that occurred is a matter of historical record.

Japan still refused to surrender. President Truman publicly and explicitly warned Japan that unless they ended the war quickly, more such bombs would be forthcoming:

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war. 33

B-29s then dropped five million leaflets across Japan, warning citizens:

TO THE JAPANESE PEOPLE:

America asks that you take immediate heed of what we say on this leaflet.

We are in possession of the most destructive explosive ever devised by men. A single one of our newly developed atomic bombs is actually the equivalent in explosive power to what 2000 of our giant B-29’s can carry on a single mission. This awful fact is one for you to ponder and we solemnly assure you it is grimly accurate.

We have just begun to use this weapon against your homeland. If you still have any doubt, make inquiry as to what happened to Hiroshima when just one atomic bomb fell on that city.

Before using this bomb to destroy every resource of the military by which they are prolonging this useless war, we ask that you now petition the Emperor to end the war. Our President has outlined for you the thirteen consequences of an honorable surrender. We urge that you accept these consequences and begin the work of building a new, better, and peace-loving Japan.

You should take steps now to cease military resistance. Otherwise, we shall resolutely employ this bomb and all other superior weapons to promptly and forcefully end the war.

EVACUATE YOUR CITIES 34

The radio station on Saipan also began broadcasting warnings every fifteen minutes directly to the Japanese people. America had undertaken every means possible to prevent dropping the first bomb, and did so again with the second one. Yet even days after the bomb on Hiroshima, the Japanese leadership remained unmoved. So on August 9, 1945, America dropped a second atomic bomb, “Fat Man,” over Nagasaki.

By 2AM the following morning (August 10), following extensive debates by Japanese authorities, Emperor Hirohito ordered acceptance of the surrender terms of the Potsdam Declaration. At 7AM the Japanese Cabinet transmitted word to the Allies that they accepted most of the terms, but insisted that the Emperor remain the sovereign ruler of the empire. Allied leaders tentatively agreed to this change so long as “from the moment of surrender, the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied powers.” 35 They awaited Japan’s official acceptance of this provision.

While awaiting the Japanese response, the Allies temporarily halted further bombing of Japan. The decision to end the war was now back in the hands of Japan’s leaders, but the people still knew nothing of Japan’s official offer of surrender. So the radio station on Saipan began announcing the news to the people, and the printing presses went into high-speed production. On August 12, B-29s dropped five million leaflets telling the Japanese:

These American planes are not dropping bombs on you today. American planes are dropping these leaflets instead because the Japanese Government has offered to surrender, and every Japanese has a right to know the terms of that offer and the reply made to it by the United States Government on behalf of itself, the British, the Chinese, and the Russians. Your government now has a chance to end the war immediately. You will see how the war can be ended by reading the two following official statements. 36

(The two statements included in the leaflet were the text of the Japanese offer to surrender, and the Allied response.)

On August 14, 1945, Japanese leaders accepted the terms and officially surrendered.

Conclusion

Neither bomb came as a surprise to the Japanese. They had been forewarned what would happen, and they chose a path of preventable destruction. Both bombs were dropped as a result of choices made by the Japanese leadership. Therefore, any “moral dilemma” that exists should center on Japanese decisions, not American ones.

By the way, Japan still has never officially apologized to America for the attack on Pearl Harbor. And Japan has other World War II skeletons in its closet that are just now being openly addressed. As one news service reported:

Japan and South Korea have only recently reached a compromise agreement to finally offer compensation and apology to the so-called “comfort women” compelled into sexual service in Japan’s wartime brothels. It remains a fragile agreement, not yet implemented, and many other wartime issues — such as the compensation for hundreds of thousands of Asians and Allied POWs dragooned into forced labor — remain unresolved. 37

Also indicative of positive American morals, after the war was over America rebuilt Japan – something it had no obligation to do. American General Douglas MacArthur guided Japan through transformational reforms in military, political, economic, and social areas. 38 An international military tribunal swiftly punished Japanese war crimes and war criminals and abolished official military Shintoism. America poured emergency food relief and economic aid into the nation, also extending $2.2 billion to Japan 39 (about $15.2 billion today). Under American leadership, the people were raised, women elevated, the economy rebuilt, and the country democratized. The transformation under American leadership was so thorough that by 1952, Japan was openly accepted back into the world community of nations.

From the American side, what happened at Hiroshima demonstrates no need for any “moral revolution,” as President Obama called it. Contrary to the claims of critics, the use of the bomb did not show a lack of morality on the part of America. On the contrary. The true immorality would have been for America to allow the war to drag on for another year, costing millions of lives, when it could have been stopped quickly, ending further deaths. No civilized person should ever want to take innocent life but rather should always seek to preserve it. The use of the atomic bomb did exactly that, saving the lives of millions, both Japanese and Allied.

Originally written Summer, 2016. Updated October, 2024.

Endnotes

1 There was a total of 60 million casualties during WWII (45 million civilian and 15 million military deaths). See “By the Numbers: World-Wide Deaths,” National WWII Museum, accessed June 24, 2016. Chinese civilian deaths alone numbered in the millions. See Micheal Clodfelter, Warfare and Armed Conflicts Fourth Edition (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 2017), 367.

2 See, for example, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Death Toll,” UCLA, accessed June 24, 2016; “The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Chapter 10 – Total Casualties,” The Avalon Project, accessed June 24, 2016.

3 Jennifer Lind, “As Obama goes to Hiroshima, here are 3 principles for a successful visit (with no apologies),” Washington Post, May 26, 2016.

4 Margaret Chadbourn, “A Look at Whether Obama Should Visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” ABC News, May 9, 2016.

5 Lawrence J. Haas, “Don’t Apologize for Hiroshima: The president mustn’t express guilt over U.S. use of nuclear weapons during World War II,” US News, April 19, 2016.

6 Gi-Wook Shin and Daniel Sneider, “Should President Obama Visit Hiroshima?” The Diplomat, April 16, 2016.

7 “Remarks by President Obama and Prime Minister Abe of Japan at Hiroshima Peace Memorial,” The White House, May 27, 2016.

8 “Pearl Harbor by the Numbers,” Pearl Harbor, May 27, 2017.

9 Professor R.J. Rummel estimates that there were over 10 million Chinese civilian casualties during the Sino-Japanese war. – R.J. Rummel, China’s Bloody Century (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1991), 103.

10 “The Contest to Cut Down 100 People,” google.com, English translations of 4 Japanese articles from 1937; see also Bob Wakabayashi, “The Nanking 100-Man Killing Contest Debate: War Guilt amid Fabricated Illusions, 1971-75,” Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 26, 307-340.

11 “The Palawan Massacre: The Story from One of its Few Survivors,” Warfare History Network, from an article in the WWII Quarterly, Spring 2019, Vol. 10, No. 3.

12 Michael Sturma, Surface and Destroy, The Submarine Gun War in the Pacific (University Press of Kentucky, 2011).

13 Mark Felton, The Slaughter at Sea, The Story of Japan’s Naval War Crimes (South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword Books Ltd., 2007).

14 The College Board, AP United States History Course and Exam Description (September 2014), 71.

15 The College Board, AP Course and Exam Description: AP United States History (Fall 2015), 75.

16 “The Decision to Drop the Bomb,” U.S. History (accessed on June 20, 2016).

17 “Reasons Against Dropping the Atomic Bomb” History on the Net, accessed September 25, 2024.

18 “The Decision to Drop the Bomb,” U.S. History, accessed June 20, 2016.

19 Saul David, “The Divine Wind: Japan’s Kamikaze Pilots of World War II,” The National WWII Museum, May 19, 2020.

20 Comfort Women Speak: Testimony by Sex Slaves of the Japanese Military, Includes new United Nations Human Rights report, ed. Sangmie Choi Schellstede (New York: Holmes & Meier, 2000).

21 Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori, The Cause of Japan (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 313.

22 Lawrence J. Haas, “Don’t Apologize for Hiroshima: The president mustn’t express guilt over U.S. use of nuclear weapons during World War II,” US News, April 19, 2016.

23 Thomas M. Coffey, Iron Eagle: The Turbulent Life of General Curtis LeMay, (New York: Crown Publishers, 1986), 147.

24 Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (New York: Random House, 1999), 340; see also, Samuel J. Cox, “H-057-1: Operations Downfall and Ketsugo – November 1945,” Naval History and Heritage Command, January, 2021.

25 Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, Vol. 1 (1994 Reprint), “‘Downfall’ The Plan for the Invasion of Japan.”

26 “Hellfire on Earth: Operation MEETINGHOUSE,” The National WWII Museum, March 8, 2020.

27 Richard S. R. Hubert, “The OWI Saipan Operation,” Official Report to US Information Service, Washington, 1946, Richard S. R. Hubert Papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives, charts pp. 88-89 .

28 Josette H. Williams, “The Information War in the Pacific, 1945,” Studies in Intelligence (2002), Vol 46, No 3, referencing “Proclamation by the Head of Governments, United States, China, and the United Kingdom,” Potsdam, Germany, July 26, 1945.

29 “Proclamation by the Head of Governments, United States, China, and the United Kingdom,” Potsdam, Germany, July 26, 1945.

30 Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori, The Cause of Japan (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 313.

31 Richard S. R. Hubert, “The OWI Saipan Operation,” Official Report to US Information Service, Washington, 1946, Richard S. R. Hubert Papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives, charts pp. 88-89, cited in Josette H. Williams, “The Information War in the Pacific, 1945,” Studies in Intelligence (2002), Vol 46, No 3. For an image of this leaflet and its translation, see “WWII Japanese Leaflets,” WallBuilders, May 29, 2023.

32 OWI [Office of War Information] Daily Digest, series 7, no. 46, 23 August 1945 cited in Josette H. Williams, “The Information War in the Pacific, 1945,” Studies in Intelligence (2002), Vol 46, No 3.

33 Harry S. Truman, “Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima,” August 6, 1945, The American Presidency Project, accessed October 3, 2024.

34 Lilly Rothman, “See a Leaflet Dropped on Japanese Cities Right Before World War II Ended,” Time, December 14, 2015.

35 Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (New York: Random House, 1999), 302.

36 Josette H. Williams, “The Information War in the Pacific, 1945,” Studies in Intelligence (2002), Vol 46, No 3.

37 Gi-Wook Shin and Daniel Sneider, “Should President Obama Visit Hiroshima?” The Diplomat, April 16, 2016.

38 “Occupation and Reconstruction of Japan, 1945-52,” Department of State, accessed June 24, 2016.

39 Nina Serafino, et. al, U.S. Occupation Assistance: Iraq, Germany and Japan Compared (Congressional Research Services, 2006), 14, “Table 2. Japan: U.S. Assistance FY1946-1952.”

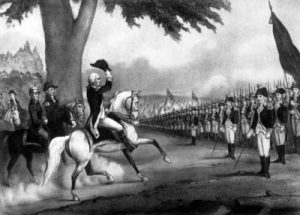

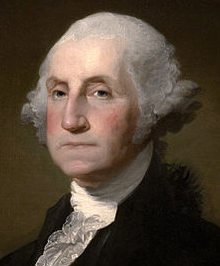

On July 3, 1775 George Washington took command of the newly formed Continental Army.

On July 3, 1775 George Washington took command of the newly formed Continental Army. Washington longed for military life from the time he was a young boy, and he got his first experience during the French and Indian War, two decades before the American Revolution. He should have been killed in the Battle of the Monongahela, but his life was saved by God’s Divine intervention. As he told his brother:

Washington longed for military life from the time he was a young boy, and he got his first experience during the French and Indian War, two decades before the American Revolution. He should have been killed in the Battle of the Monongahela, but his life was saved by God’s Divine intervention. As he told his brother: It was largely because of Washington’s experiences in that early war that he was chosen by his fellow citizens as a member of Congress, and then chosen by his peers in Congress as Commander-In-Chief.

It was largely because of Washington’s experiences in that early war that he was chosen by his fellow citizens as a member of Congress, and then chosen by his peers in Congress as Commander-In-Chief.

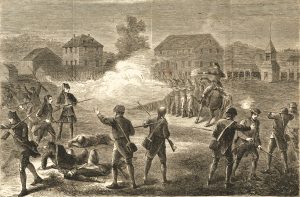

The events of April 18-19, 1775 are some of the most famous in the story of how Americans won the liberty that we still enjoy today.

The events of April 18-19, 1775 are some of the most famous in the story of how Americans won the liberty that we still enjoy today. After the alert by Revere had been delivered in Lexington, the local militia (largely the men from Clark’s church) was mustered. On the morning of April 19, 1775, some 70 Americans would face about 800 British troops.

After the alert by Revere had been delivered in Lexington, the local militia (largely the men from Clark’s church) was mustered. On the morning of April 19, 1775, some 70 Americans would face about 800 British troops. The much larger British force, having prevailed in that Lexington skirmish, continued their march towards Concord,

The much larger British force, having prevailed in that Lexington skirmish, continued their march towards Concord,

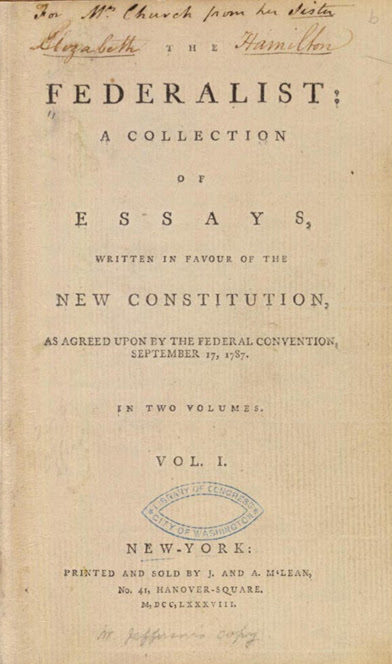

On October 27, 1787 a New York newspaper published the very first article that would come to be known as the Federalist Papers.

On October 27, 1787 a New York newspaper published the very first article that would come to be known as the Federalist Papers.