The Trial of the Century

The 1925 State v. Scopes evolution-creation trial in Dayton, Tennessee, has been called “the world’s most famous court trial,” and it was a trial that certainly did arrest the world’s attention. As William Jennings Bryan, the special prosecutor in the trial, noted,

We are told that more words have been sent across the ocean by cable to Europe and Australia about this trial than has been sent by cable in regard to anything else happening in the United States.

Indeed, few other trials have produced such crowded courtrooms and worldwide media attention or have resulted in as many full-length movies and reenactments of its proceedings as has this trial.

Bryan believed that the trial had “stirred the world” because

this cause . . . goes deep. It is because it extends wide, and because it reaches into the future beyond the power of man to see. Here has been fought out a little case of little consequence as a case, but the world is interested because it raises an issue.

Award-winning historian Henry Steele Commager described how that “issue” became a sensationalized spectacle:

The religious question—the wisdom of the State law forbidding the teaching of evolution in public schools—was, to be sure, confused by the legal one—the right of the State to enact such a law. Both public opinion and counsel largely ignored the legal and concentrated on the religious issue. It was appropriate that [William Jennings] Bryan should have appeared as counsel for the prosecution, for he was not only the most distinguished and eloquent of American fundamentalists but largely responsible for the enactment of anti-evolution laws in several southern States. It was less appropriate, perhaps, that Clarence Darrow should have been chief counsel for the defense, for in the eyes of most Americans he represented not modernist religion but irreligion, and his advocacy of evolution and assault upon fundamentalism enabled the prosecution to identify science with atheism. . . . Constitutionally, Bryan’s case was unimpeachable, for in a democracy, as Justice Holmes never tired of pointing out, the people have a right to make fools of themselves. Bryan, however, did not adopt this logical but embarrassing position. Neither he nor Darrow argued the constitutional issue, and their evasion was encouraged by the Court, the press, and public opinion. It was not young John T. Scopes, after all, who was on trial, but fundamentalism itself. To the delight of the newspapermen and the chagrin of the devout, the trial degenerated into a circus and a brawl.

The trial had revolved around a 1925 Tennessee law which stated that “it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the divine creation of man as taught in the Bible and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

When substitute teacher John Scopes taught a biology class that he “classified man along with cats and dogs, cows, horses, monkeys, lions, horses and all

that,” he was charged with violating that law.

At the trial level, district judge John Raulston allowed only the introduction of evidence and arguments which pertained to whether the law as written had been violated by John Scopes. The jury believed that it had been, and found Scopes guilty. The jury, however, requested the judge to levy the fine, so the judge imposed on Scopes the minimum fine specified by the law for a conviction. On appeal to the State Supreme Court, the jury verdict was upheld but the fine was overturned, for the law had stipulated that the jury, not the judge, must determine the amount of the fine.

The district court, in examining only whether Scopes had violated the law, had refused to consider either of two objections raised by Clarence Darrow and the Scopes defense team: (1) that the law prohibited teaching the scientific theory of evolution and therefore violated the State’s requirement “to cherish . . . science”; and (2) that the law violated the constitutional prohibition against an establishment of religion.

On appeal, the State Supreme Court was willing to examine those two objections. On the first issue, the court upheld the law’s constitutionality, explaining:

Evolution, like prohibition, is a broad term. . . . [and i]t is only to the theory of the evolution of man from a lower type that the act before us was intended to apply, and much of the discussion we have heard is beside this case.

Although the general characterization of the Scopes case was that of a legal showdown between the opposing beliefs of creation and evolution, as the court noted, it was not. The issue of the case actually was whether one specific variety of evolution teaching—and not all evolution teaching—might be banned. This was further confirmed in Justice Chambliss’ concurring opinion in which he pointed out that under the law, several theories of evolution, and even evolution in general, could still be taught:

Conceding that “the theory of evolution is altogether essential to the teaching of biology and its kindred sciences,” it will not be contended by Dr. [E. N.] Reinke [a professor of biology at Vanderbilt University relied upon by the defense team], or by learned counsel quoting from him, that the theory of evolution essentially involves the denial of the divine creation of man. . . . The theories of Drummond, Winchell, Fiske, Hibbens, Millikan, Kenn, Merriam, Angell, Cannon, Barnes, and a multitude of others, whose names are invoked in argument and brief, do not deny the story of the divine creation of man as taught in the Bible, evolutionists though they be. . . . Our laws approve no teaching of the Bible at all in the public schools, but require only that no theory shall be taught which denies that God is the Creator of man—that his origin is not thus to be traced.

For these reasons, the Court rejected Darrow’s challenge to the law, and then added:

If the Legislature thinks that . . . the cause of education and the study of science generally will be promoted by forbidding the teaching of evolution in the schools of the state, we can conceive of no ground to justify the court’s interference. The courts cannot sit in judgment on such acts of the Legislature or its agents and determine whether or not the omission or addition of a particular course of study tends “to cherish science.”

On the second objection raised against the law, the court rejected the argument that the law violated any constitutional prohibition against the establishment of religion, explaining:

We are not able to see how the prohibition of teaching the theory that man has descended from a lower order of animals gives preference to any religious establishment or mode of worship. So far as we know, there is no religious establishment or organized body that has in its creed or confession of faith any article denying or affirming such a theory. So far as we know, the denial or affirmation of such a theory does not enter into any recognized mode of worship. Since this cause has been pending in this court, we have been favored, in addition to briefs of counsel and various amici curiae, with a multitude of resolutions, addresses, and communications from scientific bodies, religious factions, and individuals giving us the benefit of their views upon the theory of evolution. Examination of these contributions indicates that Protestants, Catholics, and Jews are divided among themselves in their beliefs, and that there is no unanimity among the members of any religious establishment as to this subject. Belief or unbelief in the theory of evolution is no more a characteristic of any religious establishment or mode of worship than is belief or unbelief in the wisdom of the prohibition laws. It would appear that members of the same churches quite generally disagree as to these things. Furthermore, Chapter 277 of the Acts of 1925 requires the teaching of nothing. It only forbids the teaching of the evolution of man from a lower order of animals.

Justice Chambliss, in his concurrence, further explained why nothing religious had been established:

Considering the caption and body of this act as a whole, it is seen to be clearly negative only, not affirmative. It requires nothing to be taught. It prohibits merely. And it prohibits, not the teaching of any theory of evolution, but that theory (of evolution) only that denies, takes issue with, positively disaffirms, the creation of man by God (as the Bible teaches), and that, instead of being so created, he is a product of, springs from, a lower order of animals. No authority is recognized or conferred by the laws of this state for the teaching in the public schools, on the one hand, of the Bible, or any of its doctrines or dogmas, and this act prohibits the teaching on the other hand of any denial thereof. It is purely an act of neutrality. Ceaseless and irreconcilable controversy exists among our citizens and taxpayers, having equal rights, touching matters of religious faith, and it is within the power of the Legislature to declare that the subject shall be excluded from the tax-supported institutions, that the state shall stand neutral, rendering “unto Caesar the things which be Caesar’s and unto God the things which be God’s,” and insuring the completeness of separation of church and state.

Interestingly, while that court viewed upholding the law as an act of neutrality, contemporary courts have found State acts which are far more innocuous than that 1925 Tennessee law—acts expressly mandating neutrality—now to be unconstitutional establishments of religion. For example, American Law Reports noted:

The Supreme Court held that the establishment clause was violated by Louisiana’s Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science in Public School Instruction Act, in Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) 482 US 578, 96 L Ed 2d 510, 107 S Ct 2573. The Act declared that it was enacted to protect academic freedom; required public schools to give balanced treatment to the “sciences” of creation and evolution in classroom lectures, textbooks, library materials, or other programs to the extent that they dealt in any way with the origin of man, life, the earth, or the universe; decreed that when creation or evolution is taught, each shall be taught as a theory rather than proven scientific fact; defined “Creation-Science” and “Evolution-Science” as the scientific evidence for, respectively, creation or evolution, and inferences therefrom; forbid discrimination against any public school teacher who chooses to be a creation scientist or to teach scientific data pointing to creationist; provided that instruction in the subject of origins is not required, but insisted on instruction in both creationist and evolutionary models if public schools chose to teach either.

Significantly, even though the Louisiana statute specifically mandated that instruction be limited to an examination of “scientific data” and the “scientific evidence for, respectively, creation or evolution” and never mentioned either God or the Bible, the Court nevertheless found it to be an unconstitutional establishment of religion. As one legal observer insightfully noted, “The courts. . . . apparently find creationism to be a religious doctrine, but will not make evident the definition of religion which underlies their decisions.”

Yet, why did the earlier Tennessee court find that a State statute that specifically acknowledged God in relation to creation was not an unconstitutional establishment of religion? Because, as Justice Chambliss explained, the law reflected the provisions of . . .

. . . our Constitution, and the fundamental Declaration lying back of it, through all of which runs recognition of and appeal to “God” and a life to come. The Declaration of Independence opens with a reference to “the laws of nature and nature’s God,” and holds this truth “to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator,” etc., and concludes “with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence.” The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union read, “And whereas it hath pleased the Great Governor of the world . . .

Because the state law was consistent with the explicit language in our federal governing documents, and because it negated only “the right to teach in the public schools a denial of the existence, recognized by our Constitution, of the Creator of all mankind,” it was upheld by the Court. Based, therefore, on the wording in the founding documents, Chambliss had concluded:

That the Legislature may prohibit the teaching of the future citizens and office holders to the State a theory that denies the Divine Creator will hardly be denied.

Significantly, to reach this conclusion, the decision had cited three of the four documents identified in the U. S. Code as “organic laws”—those documents that establish and define the operation of our government. Since those organic laws specifically fuse into the American structure of government the concept of a divine creator, a probing question is: may the judiciary nullify, or rule to be unconstitutional, a teaching expressly set forth in the documents it is charged with upholding?

The Timelessness of the Conflict

The response to this question often comes in the form of an objection: science has acquired new information unknown to those who framed our government; based, therefore, on this new information, the courts must reach conclusions at variance with those stipulated by the founding documents. Or, as Vermont Law School Professor Steven Wise argues,

Facts change and with them the scientific theories that assume those facts. . . . When facts change, the law that assumes those facts should change.

However, it is a mistake to believe that the arguments about evolution actually postdate the framers of our documents. While uninformed laymen erroneously believe the theory of evolution to be a product of Charles Darwin in his first major work of 1859, the historical records are exceedingly clear that our framers were well-acquainted with the theories and principle teachings of evolution—as well as the science and philosophy both for and against that thesis—well before Darwin synthesized those long-standing teachings in his writings.

For example, Nobel Prize winner Bertrand Russell explains: “The general idea of evolution is very old; it is already to be found in Anaximander (sixth century B.C.). . . . [and] Descartes, Kant, [and] Laplace had advocated a gradual origin for the solar system in place of sudden creation.” Professor Henry Fairfield Osborn, a zoologist and paleontologist, agrees, declaring that there are “ancient pedigrees for all that we are apt to consider modern. Evolution has reached its present fullness by slow additions in twenty-four centuries.” He continues,

Evolution as a natural explanation of the origin of the higher forms of life . . . developed from the teaching of Thales and Anaximander into those of Aristotle. . . . and it is startling to find him, over two thousand years ago, clearly stating, and then rejecting, the theory of the survival of the fittest as an explanation of the evolution of adaptive structures.

And British anthropologist Edward Clodd similarly affirms that,

The pioneers of evolution—the first on record to doubt the truth of the theory of special creation, whether as the work of departmental gods or of one Supreme Deity, matters not—lived in Greece about the time already mentioned; six centuries before Christ.

For example, Anaximander (600 b.c.) introduced the theory of spontaneous generation; Diogenes (550 b.c.) introduced the concept of the primordial slime; Empedocles (495-455 b.c.) introduced the theory of the survival of the fittest and of natural selection; Democritus (460-370 b.c.) advocated the mutability and adaptation of species; the writings of Lucretius, before the birth of Christ, announced that all life sprang from “mother earth” rather than from any specific deity; Bruno (1548-1600) published works arguing against creation and for evolution in 1584-85; Leibnitz (1646-1716) taught the theory of intermedial species; Buffon (1707-1788) taught that man was a quadruped ascended from the apes, about which Helvetius also wrote in 1758; Swedenborg (1688-1772) advocated and wrote on the nebular hypothesis (the early “big bang”) in 1734, as did Kant in 1755; etc. It is a simple fact that countless works for (and against) evolution had been written for over two millennia prior to the drafting of our governing documents and that much of today’s current phraseology surrounding the evolution debate was familiar rhetoric at the time our documents were framed.

In fact, Dr. Henry Osborn, curator of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, describes the third period in the history of evolution —the period in which our framers lived—as a period which produced the evolution writings of

Linnaeus, Buffon, E[rasmus] Darwin, Lamarck, Goethe, Treviranus, Geof. St. Hilaire, St. Vincent, Is. St. Hilaire. Miscellaneous writers: Grant, Rafinesque, Virey, Dujardin, d’Halloy, Chevreul, Godron, Leidy, Unger, Carus, Lecoq, Schaafhausen, Wolff, Meckel, Von Baer, Serres, Herbert, Buch, Wells, Matthew, Naudin, Haldeman, Spencer, Chambers, Owen.

Clearly, then, it was not in the absence of knowledge about the debate over evolution, but rather in its presence, that our framers made the decision to incorporate in our governing documents the principle of a creator.

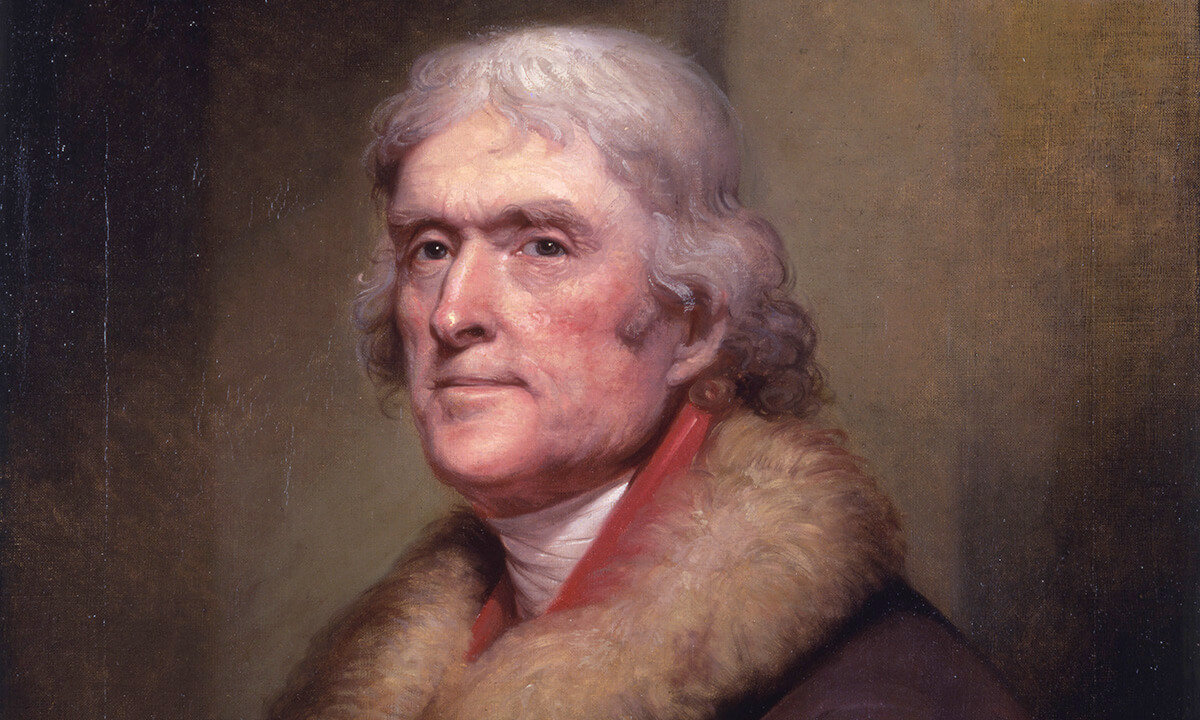

Thomas Paine provides one example affirming this. Although Paine was the most openly and aggressively anti-religious of the founders, in his 1787 Discourse at the

Society of Theophilanthropists in Paris, Paine nevertheless forcefully denounced the French educational system which taught students that man was the result of prehistoric cosmic accidents or had developed from some other species:

It has been the error of schools to teach astronomy, and all the other sciences and subjects of natural philosophy, as accomplishments only; whereas they should be taught theologically, or with reference to the Being who is the Author of them: for all the principles of science are of divine origin. Man cannot make, or invent, or contrive principles; he can only discover them, and he ought to look through the discovery to the Author.

When we examine an extraordinary piece of machinery, an astonishing pile of architecture, a well-executed statue, or a highly-finished painting where life and action are imitated, and habit only prevents our mistaking a surface of light and shade for cubical solidity, our ideas are naturally led to think of the extensive genius and talent of the artist.

When we study the elements of geometry, we think of Euclid. When we speak of gravitation, we think of Newton. How, then, is it that when we study the works of God in creation, we stop short and do not think of God? It is from the error of the schools in having taught those subjects as accomplishments only and thereby separated the study of them from the Being who is the Author of them. . . .

The evil that has resulted from the error of the schools in teaching natural philosophy as an accomplishment only has been that of generating in the pupils a species of atheism. Instead of looking through the works of creation to the Creator Himself, they stop short and employ the knowledge they acquire to create doubts of His existence. They labor with studied ingenuity to ascribe everything they behold to innate properties of matter and jump over all the rest by saying that matter is eternal.

And when we speak of looking through nature up to nature’s God, we speak philosophically the same rational language as when we speak of looking through human laws up to the power that ordained them.

God is the power of first cause, nature is the law, and matter is the subject acted upon.

But infidelity, by ascribing every phenomenon to properties of matter, conceives a system for which it cannot account and yet it pretends to demonstration.

Paine certainly did not advocate this position as a result of religious beliefs or of any teaching in the Bible, for he believed that “the Bible is spurious” and “a book of lies, wickedness, and blasphemy.” Yet, this anti-Bible Founder was nevertheless a strong supporter of teaching the theistic origins of man.

Theistic v. Non-Theistic Approaches

For the past twenty-five centuries, the debate has divided itself along two primary approaches. As Justice Chambliss noted:

Two theories of organic evolution are well recognized, one the theistic. . . . [and t]he other theory is known as the materialistic, which denies that God created man, that He was the first cause.

Confirming this general distinction between approaches, Dr. Robert Clark from Cambridge notes:

Haeckel [1834-1919] claimed that spontaneous generation must be true, not because its truth could be confirmed in the laboratory, but because, otherwise, it would be necessary to believe in a Creator. . . . Compare the remark of Sir Charles Lyell [1797-1875, author of several works that influenced Darwin], “The German critics have attacked me vigorously, saying that by the impugning of the doctrine of spontaneous generation, I have left them nothing but the direct and miraculous intervention of the First Cause.”

Yet, despite the fact that the arguments about evolution are frequently drawn toward religion, John Dewey accurately observed:

The vivid and popular features of the anti-Darwinian row tended to leave the impression that the issue was between science on one side and theology on the other. Such was not the case—the issue lay primarily within science itself, as Darwin himself early recognized.

Indeed, this has always been, and still is, a hotly contested debate among highly credentialed scientists from both sides; and these debates over evolution continue to prove that establishing the origin of man is, scientifically speaking, an inquiry still surrounded by much hypothetical conjecture and debate. That is, while science is settled among all scientists on issues like gravity, fluid dynamics, heliocentricity, the laws of motion, etc., there still is no clear consensus—or anything approaching it—among scientists on the issue of the origins of man.

While the debate over the origins of man has always been between a theistic and a non-theistic explanation, among those who embrace the theistic view have been found—and still are found—three distinct approaches (although the latter two are not incompatible with the first): (1) intelligent-design (that which exists came into being by divine guidance, but the period of time required or the specifics of the process are unsettled, possibly unprovable, and therefore remain debatable); (2) theistic evolution (that which exists came into being over a long, slow passing of time through natural laws and processes but under divine guidance); and (3) special creation (that which exists came into being in six literal days). This, then, makes four separate historical approaches to the origins of man: three theistic, and one non-theistic.

In the non-theistic camp, Empedocles (495-435 b.c.) was the father and original proponent of the evolution theory, followed by advocates such as Democritus (460-370 b.c.), Epicurus (342-270 b.c.), Lucretius (98-55 b.c.), Abubacer (1107-1185 a.d.), Bruno (1548-1600), Buffon (1707-1788), Helvetius (1715-1771), Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), Lamarck (1744-1829), Goethe (1749-1832), Lyell (1797-1875), etc.

In the theistic camp, Anaxigoras (500-428 b.c.) was the father of intelligent design; that same belief was also expounded by such distinguished scientists and philosophers Descartes (1596-1650), Harvey (1578-1657), Newton (1642-1727), Kant (1729-1804), Mendel (1822-1884), Cuvier (1769-1827), Agassiz (1807-1873), etc. Significantly, even Charles Darwin (1809-1882), strongly influenced by the writings of Paley (1743-1805), embraced the intelligent design position at the time that he wrote his celebrated work, explaining:

Another source of conviction in the existence of God, connected with the reason and not with the feelings, impresses me as having much more weight. This follows from the extreme difficulty, or rather impossibility, of conceiving this immense and wonderful universe, including man with his capacity of looking far backwards and far into futurity, as the result of blind chance or necessity. When thus reflecting I feel compelled to look to a First Cause having an intelligent mind in some degree analogous to that of man; and I deserve to be called a Theist. This conclusion was strong in my mind about the time, as far as I can remember, when I wrote the Origin of Species.

John Dewey, an ardent 20th century proponent of Darwinism, explained why the intelligent design position—scientifically speaking—was reasonable:

The marvelous adaptation of organisms to their environment, of organs to the organism, of unlike parts of a complex organ—like the eye—to the organ itself; the foreshadowing by lower forms of the higher; the preparation in earlier stages of growth for organs that only later had their functioning—these things are increasingly recognized with the progress of botany, zoology, paleontology, and embryology. Together, they added such prestige to the design argument that by the later eighteenth century it was, as approved by the sciences of organic life, the central point of theistic and idealistic philosophy.

(This position of intelligent design, also called the anthropic or teleological view, is now embraced by an increasing number of contemporary distinguished scientists, non-religious though many of them claim to be. )

The second camp within the theistic approach is theistic evolution, which was first propounded by Aristotle (384-322 b.c.). Other prominent expositors of this view included Gregory of Nyssa (331-396 a.d.), Augustine of Hippo (354-430 a.d.), St. Gregory the First (540-604 a.d.), St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), Leibnitz (1646-1716), Swedenborg (1688-1772), Bonnet (1720-1793), and numerous contemporary scientists. In fact, many of Darwin’s contemporaries embraced this view, believing that “natural selection could be the means by which God has chosen to make man.” As confirmed by Dr. James Rachels, professor at the University of Alabama at

Birmingham:

Mivart [1827-1900, a professor in Belgium] became the leader of a group of dissident evolutionists who held that, although man’s body might have evolved by natural selection, his rational and spiritual soul did not. At some point God had interrupted the course of human history to implant man’s soul in him, making him something more than merely a former ape. . . . Wallace [1823-1913, who advocated natural selection prior to Darwin] took a view very similar to that of Mivart: he held that the theory of natural selection applies to humans, but only up to a point. Our bodies can be explained in this way, but not our brains. Our brains, he said, have powers that far outstrip anything that could have been produced by natural selection. Thus he concluded that God had intervened in the course of human history to give man the “extra push” that would enable him to reach the pinnacle on which he now stands. . . . Natural selection, while it explained much, could not explain everything; in the end God must be brought in to complete the picture.

In fact, Darrow himself, during the trial, admitted that this was a prominent position of many in that day, and Dudley Malone, Darrow’s co-counsel, even declared:

[W]e shall show by the testimony of men learned in science and theology that there are millions of people who believe in evolution and in the stories of creation as set forth in the Bible and who find no conflict between the two.

Interestingly, writers who chronicle the centuries-long history of the evolution debate confirm that there have always been numerous evolutionists in both the theistic and the non-theistic camps, and much of the proceedings in the Scopes trial reaffirmed that a belief in evolution was not incompatible with teaching theistic origins and a belief in a divine creator.

The third camp, special (or literal) creation, was championed by Francisco Suarez (1548-1617) and later by Pasteur (1822-1895) as well as by subsequent contemporary scientists.

The history of this controversy through recent years and even previous centuries makes clear that scientific discovery has not significantly altered any of these four views. There have always been, and still continue to be, scientists in each group finding new scientific facts that they interpret to bolster their arguments. Remarkably, only judges seem comfortable in settling which side of an ongoing centuries-old scientific debate is correct.

Public Opinion on the Issue

Another noteworthy part of the Tennessee decision was the court’s desire to reach neutrality, as it explained, by teaching, on the one hand, neither the “Bible, or any of its doctrines or dogmas,” or, on the other hand, “teaching the denial of . . . divine creation,” because “it is too well established for argument that ‘the story of the divine creation of man as taught in the Bible’ is accepted—not ‘denied’—by millions of men and women.”

Today, nearly a century-and-a-half after Darwin’s original work, and following literally thousands of writings by scientists and philosophers on all sides of the evolution controversy, the courts’ characterization in the Scopes decision still seems accurately to reflect the public’s sentiment today.

For example, in the 1920s, twenty state legislatures considered measures to prohibit the teaching of anti-theistic evolution; in the 1990s, the number of states that considered such measures was identical—twenty. Polls also confirm that there has not been much shift in public opinion in recent decades. For example, in 1982, 9 percent of the nation believed in non-theistic origins, 38 percent in theistic evolution, and 44 percent in theistic special creation. In 1998, an average was compiled of polls from the 1980s and 1990s, finding that during that period, 10 percent believed in non-theistic origins, 40 percent in theistic evolution, and 45 percent believed in theistic special creation. Then a subsequent 1999 poll found that 9 percent believed in non-theistic origins, 40 percent in theistic evolution, and 47 percent in theistic special creation.

Numerous other polls regularly confirm that from 85 to 90 percent of Americans embrace a theistic view, yet the courts simply do not permit this view to be presented,

preferring instead what the Tennessee court had described as the “teaching of the denial” of the belief accepted “by millions of men and women.” The Supreme Court has indeed become a self-described “super board of education for every school district in the nation” by prescribing non-theistic origins as the state orthodoxy throughout all public school classrooms.

An Informed Decision

Significantly, each provision of our governing documents reflects a deliberate choice based on specific reasoning, and as previously demonstrated, the evolution controversy was well developed at the time our founding documents were drafted. The framers therefore deliberately chose to incorporate into those documents not only the belief in theistic origins over that of non-theistic origins but also a belief in elected representation over hereditary leadership, the consent of the governed over monarchy, separation of powers over consolidation, bicameralism over unicameralism, republicanism over democracy, etc.

Consequently, the fact that a position for a divine creator is officially made a part of our founding documents—documents of government and not documents of religion—makes theistic origins a part of our political, not merely religious or even scientific, theory. Under our founding documents, therefore, the judiciary can no more disallow theism than it can disallow republicanism or separation of powers.

Yet, if the contemporary courts are correct that either the acknowledgment of God or the teaching of a divine creator is an unconstitutional establishment of religion under the First Amendment, then evidently one of the purposes for the First Amendment was to keep specific principles in the Declaration of Independence from being taught. While such a conclusion is illogical, it is nevertheless defended by asserting that the belief of a creator is incorporated into the Declaration rather than the Constitution, and that the Declaration is a separate document from, and is not to affect the interpretation of, the Constitution.

This argument is of recent origin, however, for well into the twentieth century, the Declaration and the Constitution were viewed as interdependent rather than as independent documents. In fact, the U. S. Supreme Court declared:

[T]he latter [the Constitution] is but the body and the letter of which the former [the Declaration of Independence] is the thought and the spirit, and it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence.

No other conclusion logically can be reached since the Constitution directly attaches itself to the Declaration in Article VII by declaring:

Done in convention by the unanimous consent of the States present the seventeenth day of September in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty seven, and of the independence of the United States of America the twelfth. (emphasis added)

Additional evidence that the framers viewed the Declaration as inseparable from the Constitution is seen by the fact that Presidents George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, et al., dated their government acts under the Constitution from the Declaration rather than the Constitution.

Furthermore, the admission of territories as States into the Union was often predicated on an assurance by the State that the State’s. . .

. . . constitution, when formed, shall be republican, and not repugnant to the Constitution of the United States and the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

The framers believed that the Declaration provided the core values by which the Constitution was to operate, and that the Constitution was not to be interpreted apart from those values. As John Quincy Adams explained in his famous oration, The Jubilee of the Constitution:

[T]he virtue which had been infused into the Constitution of the United States . . . was no other than the concretion of those abstract principles which had been first proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence. . . . This was the platform upon which the Constitution of the United States had been erected. Its virtues, its republican character, consisted in its conformity to the principles proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and as its administration . . . was to depend upon the . . . virtue, or in other words, of those principles proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and embodied in the Constitution of the United States.

The framers never imagined that the Constitution could be interpreted to violate the values they had erected in the Declaration; for, under America’s government as originally established, a violation of the principles of the Declaration was just as serious as a violation of the provisions of the Constitution. Nonetheless, courts over the past half-century have isolated the two documents, now making them mutually exclusive.

A Battle of Civilizations

Returning to an examination of the Scopes case; since the point in question was not whether evolution teaching could be banned but rather whether evolution teaching that denied the principles of the founding documents could be banned, what, then, did the participants of the Scopes case see as the real issue? Strikingly, both sides believed that the case actually represented a struggle for society itself.

Scopes’ defense counsel Arthur Hays described the case as a “duel to the death,” and prosecutor Gen. Thomas Stewart confirmed that it was an issue that “strikes at the very vitals of civilization.” William Jennings Bryan called it “a duel between two great ideas,” and Darrow, shortly after the trial started, deprecatingly acknowledged that he was arguing the case as if it were “a death struggle between two civilizations.”

The participants on each side—like so many before and after them—understood that the ramifications of the question of theistic origins went far beyond any alleged scientific dispute and focused rather on what type of civilization America would experience. Interestingly, much of the debate in the trial actually addressed the societal ramifications that would be realized under each viewpoint.

Yet, how does a conflict between a theistic and a non-theistic view of the origins of man actually affect civilization? Because the view embraced determines a culture’s approach to the meaning of life, and therefore subsequently will define both the purpose of government and the manner in which it will interact with its citizens. As Princeton Professor Peter Singer explains:

In what sense does rejection of belief in a god imply rejection of the view that life has any meaning? If this world had been created by some divine being with a particular goal in mind, it could be said to have meaning, at least for that divine being. If we could know what the divine being’s purpose in creating us was, we could then know what the meaning of our life was for our creator. If we accepted our creator’s purpose (though why we should do that would need to be explained), we could claim to know the meaning of life.

When we reject belief in a god we must give up the idea that life on this planet has some preordained meaning. Life as a whole has no meaning. Life began, as the best available theories tell us, in a chance combination of molecules; it then evolved through random mutations and natural selection. All this just happened; it did not happen for any overall purpose. Now that it has resulted in the existence of beings who prefer some states of affairs to others, however, it may be possible for particular lives to be meaningful.

As Singer observes, if there is a creator, then there can be a purpose and meaning—even an intrinsic value—to life; however, if there is no creator, then there is meaning only for “particular” lives. Thus, how government touches the lives of its citizens will be radically different, depending on which view is adopted.

For example, will all lives have intrinsic worth and therefore be protected equally by government, or will just “particular” lives have worth and therefore receive special protection and treatment? And if not all lives have equal worth, then who determines which lives will have worth—and what criteria will be used to make that determination? And if there is no creator, then there is no special purpose for a life—or a society—and in place of order and design instead will be policies reflecting chance and variableness; and if there is no design, then even morality itself must become relative, dependent upon time, place, and circumstances.

John Dewey, a strong supporter of Darwin, recognized the difference that a belief in design made to a society. As he acknowledged, a society that embraced the “design argument” was characterized by “purposefulness,” and “this purposefulness gave sanction and worth to the moral and religious endeavors of man.” However, as he also recognized, “the Origin of Species introduced a mode of thinking that in the end was bound to transform the logic of knowledge, and hence the treatment of morals, politics, and religion.”

In short, to embrace Darwin’s principles would result in a paradigm shift throughout the whole of society. As Commager confirmed:

The impact of Darwin. . . . repudiated the philosophical implications of the Newtonian system, substituted for the neat orderly universe governed by fixed laws, a universe in constant flux whose beginnings were incomprehensible and whose ends were unimaginable, reduced man to a passive role, and by subjecting moral concepts to its implacable laws deprived them of that authority which had for so long furnished consolation and refuge to bewildered man.

Darrow recognized—and Dewey, Singer, and others subsequently confirmed—that Darwinism would result in a new approach to civilization.

However, this difference in the societal—that is, the civilizational—effects proceeding from which view of the origins of man was adopted was already understood and articulated centuries ago both by the framers and by the political theorists on whom they relied. Therefore, their decision to invoke the belief in a creator into our form of government was willfully to establish an approach that would distinguish the American philosophy of a civilized society from the non-theistic approaches to civilization present in so many other nations of that day.

The remainder of this work will document the various manners in which the judiciary’s rejection of theistic origins has dramatically altered the American civilization—her approach to law, morality, crime and punishment, and even the role, and the form, of government.

(Note: Whereas evolution in past generations could mean either theistic or non-theistic origins, as a result of court decisions over the past three decades, evolution is now understood to mean only the non-theistic view. In fact, even theistic evolution is currently called creationism and is seen to be “religious,” notwithstanding the fact that many of its proponents—including Darwin, Paine, Dewey, etc.—were not even remotely religious. Therefore, for the remainder of this work, the terms “evolution”

and “Darwinism” will, according to their contemporary usage, refer to the non-theistic approach to the origins of man.)

Uniqueness v. Speciesism

From the belief that a creator made human life (that, according to the Declaration of Independence, “all men are created”), and that human life was made with design or purpose, proceeded the ancillary belief that human life was therefore distinct. Consequently, not only was all human life equal in value (“all men are created equal”) but also all human life was unique from and more important than other life; and so man must be a good steward of the world in which he is placed. More, therefore, would be expected from man than from any other being in creation.

Pufendorf, one of the chief political theorists on whom the framers relied and whom they highly recommended to following generations, encapsulated this belief in these words:

[T]he word humanity import[s] that condition in which man is placed by his creator, who hath been pleased to endue him with excellencies and advantages in a high degree above all other animate beings. . . . and that ‘tis expected that he should maintain a course of life far different from that of brutes.

William Blackstone, in his famous Commentaries on the Laws, similarly explained:

In the beginning of the world . . . the all-bountiful creator gave to man, “dominion over all the earth; and over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” This is the only true and solid foundation of man’s dominion over external things, whatever airy metaphysical notions may have been started by fanciful writers upon this subject. The earth therefore, and all things therein, are the general property of all mankind, exclusive of other beings, from the immediate gift of the creator.

Thus, from the belief in a creator came the ensuing belief that man was a unique species, alone endowed with superior rational and moral capacities, and that he held intrinsic worth surpassing that of what John Locke had called “all inferior creatures,” or all other species. Man’s life, therefore, had purpose—or, in the words of

John Dewey, “the classic notion of species carried with it the idea of purpose.”

Darwin changed that view, asserting that man actually was not very special after all. As he explained, “Man, in his arrogance, thinks himself a great work, worthy of the interposition of a deity. More humble and, I believe, true, to consider him created from animals.” Regarding this statement, Dr. James Rachels observed:

Darwin wrote these words in 1838, twenty-one years before he was to publish The Origin of Species. He would go on to support this idea with overwhelming evidence, and in doing so he would bring about a profound change in our conception of ourselves.

Independent observers had quickly grasped the ramifications of this change in the value of man. In fact, one critic challenged Sir Charles Lyell (a writer who strongly influenced Darwin) on this very point. As Lyell reported, “one of Darwin’s reviewers put the alternative strongly by asking ‘whether we are to believe that man is modified mud or modified monkey.’ The mud is a great comedown from the ‘archangel ruined’.” Because of Darwin, man was now just one of the animals, and as Commager noted:

The impact of Darwin. . . . was a blow to man rather than to God who, in any event, was better able to bear it, for if it relegated God to a dim first cause, it toppled Man from his exalted position as the end and purpose of creation, the crown of nature, and the image of God, and classified him prosaically with the anthropoids.

Consequently, since man was now just one of the animals, English scholar Henry Salt urged in 1892 that

we must get rid of the antiquated notion of a ‘great gulf’ fixed between them [animals] and mankind and must recognize the common bond of humanity that unites all living beings in one universal brotherhood.

And since man had now become part of one “universal brotherhood” with all other animals, then all shared the same future. That is, if man had a soul and a spirit, so did the animals; if they did not, neither did he. As Salt explained, “mankind and the lower animals have the same destiny before them, whether that destiny be for immortality or for annihilation.” As Dr. Rachels so well summarized:

After Darwin, we can no longer think of ourselves as occupying a special place in creation—instead, we must realize that we are products of the same evolutionary forces, working blindly and without purpose, that shaped the rest of the animal kingdom.

Dr. Margot Norris, professor at the University of California at Irvine, confirms, “Darwin collapsed the cardinal distinctions between animal and human.” Princeton Professor Peter Singer agrees, observing that because of Darwin’s proposals, “Human beings now knew that they were not the special creation of God, made in the divine image and set apart from the animals; on the contrary, human beings came to realize that they were animals themselves.” Therefore, as Henry Salt pointed out, “the term ‘animals,’ as applied to the lower races, is incorrect . . . since it ignores the fact that man is an animal no less than they.”

Today, the belief that man is in any way different from, or superior to, other animal species is known as “speciesism” —a term coined in 1920 by Oxford psychologist Richard Ryder. Peter Singer, a founder of PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) calls speciesism “a form of prejudice, immoral and indefensible in the same way that discrimination on the basis of race is immoral and indefensible.” Just as a racist considers those from another race as inferior, a speciesist considers those from another species as inferior. A speciesist is simply a more universal form of a racist.

Dr. Steve Sapontzis, a professor at Cal State, argues that since man is not superior to other species, it is therefore wrong to be a speciesist. He asserts:

[I]t is not membership in any particular species that confers higher value on one’s life. It is the possession of intellectual abilities, which could belong to a wide variety of life forms. It is an empirical accident, a fluke of evolution, that only the human species has developed these abilities.

North Carolina State University Professor Tom Regan concurs:

[I]t has long seemed to me that far too much moral importance is attached to being a person. . . . That someone is a person is morally relevant, certainly. But that being a person makes one morally superior, or confers on that individual moral rights no other living being can possibly possess: these seem to me to be more in the nature of arrogant dogma than reasoned belief.

Dr. Marc Hauser, professor at Harvard, agrees:

To admire our species for its qualities is natural. To place us with the gods and angels, above all the others, is both pompous and boring. It is pompous because it places us on top of an intellectual pyramid without articulating the criteria for evaluation. It is boring because it ignores differences in thinking, and fails to search for an understanding of how different shades of mind evolved.

Steven Wise, instructor of animal law courses at four universities, therefore ridicules as ‘imbecilic’ the belief that human beings are superior to other animals and charged with dominion over them.

Very simply, all species are equal—or, in the words of Ingrid Newkirk, director of a powerful animal rights group, “A rat is a pig is a boy is a dog.”

If there is no significant difference in value between the species, then the death of a member of a non-human species is as great a tragedy as the death of one from the human species. As Singer explains:

[W]hether a being is or is not a member of our species is, in itself no more relevant to the wrongness of killing it than whether it is or is not a member of our race. The belief that mere membership of our species, irrespective of other characteristics, makes a great difference to the wrongness of killing a being is a legacy of religious doctrines.

In fact, when Dr. Regan was asked, “If you were aboard a lifeboat with a baby and a dog, and the boat capsized, would you rescue the baby or the dog?” Regan responded, “If it were a retarded baby, and bright dog, I’d save the dog.”

With the rejection of the theistic approach to origins, all other life forms are now elevated in value to that once uniquely held by humans. This view has resulted in an aggressive animal rights movement. Dr. Jack Albright, professor at Purdue, summarizes the main tenets of the animal-rights non-speciesists:

[P]roponents of animal rights hold that animals must not be exploited in any manner. In other words, the only interactions humans should have with animals are those that occur by happenstance or those that are initiated by an animal. Animal rights advocates believe that animals have basic rights—many say, the same as people—to be free from confinement, pain, suffering, use in experiments, and death for reason of consumption by other animals (including humans). Thus, animal rights advocates oppose the use of animals for food, for clothing, for entertainment, for medical research, for product testing, for seeing-eye dogs, and as pets. . . . The animal rights proponents believe that humans have evolved to a point where they can live without any animal products—meat, milk, eggs, honey, leather, wool, fur, silk, by products, etc. These advocates offer a long list of concerns in support of the conclusion that neither medical researchers nor the cosmetic industry has the right to experiment on animals. They also conclude that the animal kingdom is exploited by hunters, zoos, circuses, rodeos, horse racing, horseback riding, the use of simians (small primates) to assist quadraplegics in wheelchairs, and by the keeping of animals as pets.

Under this more “evolved” non-speciesist view, the alleged mistreatment of animals is often described in terms of human brutalities and compared to human atrocities. For example, the co-director of one national animal rights group declared: “Six million people died in concentration camps, but six billion broiler chickens will die this year in slaughter houses.” Others, like Peter Singer, a candidate from the Green Party, make similar comparisons:

You cannot write objectively about the experiments of the Nazi concentration camp “doctors” on those they considered “subhuman” without stirring emotions; and the same is true of a description of some of the experiments performed today on nonhumans in laboratories in America, Britain, and elsewhere.

Long time Cal State professor Steve Sapontzis agrees:

Believing that the superior value of human life justifies sport hunting, luxury furs, or veal production presumes a hidden, feudalistic premise. That is an easy presumption, however, when we are sure that we are and will remain at the top of the feudal power pyramid. That is, of course, just what we are sure of in our relation to animals, and why we can with such clear consciences continue to be Nazis to our animals.

Singer also finds similarities with African-American slavery, declaring that what animals have endured “can only be compared with that which resulted from the centuries of tyranny by white humans over black humans.” In fact, Dr. Susan Finsen, professor at Cal State, believes that those human atrocities—and even the current “exploitation of women, gays, third world peoples, etc., is bound up with the exploitation of animals.” Singer therefore asserts, “It can no longer be maintained by anyone but a religious fanatic that man is the special darling of the whole universe, or that other animals were created to provide us with food.”

Believing, then, that the death of an animal is the equivalent of a Nazi murder, non-speciesists make every effort to bring to bear the full force of the law to protect animals.

So strong is the movement resulting from this non-theistic belief of origins that courses on animal law are now being offered at Harvard, the University of California, Vermont Law School, Georgetown, John Marshall Law School, Tufts University, the University of Oregon, and a number of other prominent schools.

Seeking to remove any and all distinctions between humans and animals, the effort is underway to obtain not only legal “personhood status” for animals but also to win for them “[m]any of the ‘rights’ that humans consider profoundly dear, such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Professor Steven Wise of the John Marshall Law School sets forth the goal:

For centuries, a Great Legal Wall has divided humans from every other species of animal in the West. On one side, every human is a person with legal rights; on the other, every non-human is a thing with no legal rights. Every animal rights lawyer knows that this barrier must be breached.

The difficulties faced in ultimately achieving these legal rights for non-human animals—according to Professor Wise— is that:

Since “animal law” is primarily a matter of state concern, the battle for the legal personhood of non-human animals will have to proceed on fifty state fronts.

Recognizing that non-human animals “have no more power to bring their own claims [before a court] than do human incompetents,” Wise therefore recommends several methods by which humans might sue in behalf of non-human animals, including the seeking of guardianship, the use of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, intervening in a forfeiture action against non-human animals, etc. Significantly, his methods have proven successful.

For example, in 1994, Taro, an Akita dog, was sent to “death row” for attacking and marring a young child, but New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman signed an official state pardon for the dog on the basis of forfeiture intervention. In 1998, the U. S. Court of Appeals for DC granted legal standing to a man suing on behalf of monkeys in a Long Island zoo. And in 1993, the Federal Rules for Civil Procedures were extended to a dolphin, with the court declaring that the “rule could ‘apply to . . . non-human entities’.”

With attorneys thus “fighting for the rights of the disenfranchised,” an amazing cadre of suits now blurs the distinction between human animals and non-human animals. In fact, the rhetoric surrounding those cases increasingly describes non-human animals in terms that once were limited solely to humans.

For example, a family in Massachusetts, suing the owners of dogs that killed their sheep, is seeking more than just the traditional recovery for damages to their livestock. As they explain, because they were forced to watch “a lamb grow up without a mother” and to “live with this fear” of dogs, they are seeking “emotional damages and loss of companionship, just as if a child had been killed.” In a separate case based on the injury of a pet at a kennel, a family sued for “emotional distress” because they “deem that animal as a part of their family [and] look at the animal as another person.” In fact, damages were even awarded in one case because a dog “cried” when a vet worked on its teeth.

Not only do such cases routinely employ once uniquely human rhetoric but also the cases now decide issues for animals based on how similar issues for humans would be determined. In fact, courts even acknowledge that in cases settling disputes over the possession of animals, they may “analogize it to a child custody case, inquiring into what was in the ‘best interests’ ” of the animal —terms usually reserved for children in divorce proceedings. Therefore, in a “custody dispute” over a cat, the court made its determination based on what was in the “cat’s best interests,” thereby allowing it to remain where it had “lived, prospered, loved and been loved” for the previous four years.

Also reflective of the use of traditional human descriptions is that of placing animals “in adoptive homes,” of seeking damages for the loss of the “companionship, loyalty, security, and friendship” of animals killed in “wrongful death” scenarios, and even of comparing the handling of a deceased pet in terms of “the anguish resulting from the mishandling of the body of a child.”

Clearly, many distinctions between humans and animals, legally speaking, are blurring, as evidenced by the language in this ruling:

[Dogs] represent some of the best human traits, including loyalty, trust, courage, playfulness, and love. . . . At the same time, dogs typically lack the worst human traits, including avarice, apathy, pettiness, and hatred. Scientific research has provided a wealth of understanding to us that we cannot rightly ignore. We now know that mammals share with us a great many emotive and cognitive characteristics, and that the higher primates are very similar to humans neurologically and genetically. It is not simplistic, ill-informed sentiment that has led our society to observe with compassion the occasionally televised plights of stranded whales and dolphins. It is, on the contrary, a recognition of a kinship that reaches across species boundaries. The law must be informed by evolving knowledge and attitudes.

Notice the adoption of the legal position that there is a “kinship” between man and other animals, and that the “kinship” reaches “across species boundaries” because of our “evolving knowledge and attitudes.”

This language diminishing legal distinctions between species—between “human animals” and “non-human” animals—is a direct result of the non-theistic approach to the origins of man. Clearly, Darwinism has changed the face of American law.

Each of the previous cases, and the new type of American civilization they represent, proceeds from acceptance of Darwin’s statement that “the differences between human beings and animals are not so great as is generally supposed.” And science certainly seems to confirm Darwin’s thesis—as well as the position held by non-speciesists—for there is “scientific evidence suggesting that chimpanzees and humans diverged from the same evolutionary path and that their DNA is nearly 98.5 percent identical.” Yet, as explained by Chapman University Professor Tibor Machan, it is not the similarities that are the most consequential element of the comparison between man and animals:

Indeed, while humans share about 97% of their DNA structure with some higher non-human animals, those last 3% are so vital that all of human civilization, religion, art, science, philosophy and, most importantly, their moral nature depends upon it. And this is attested to by most vegans [vegetarians]—e.g., when they appeal to human beings to deal with other animals in considerate ways rather than to other animals to do this. None of them turn to a lion, for example, to implore it not to kill the zebra or to do it more humanely.

It is the three- percent that distinguishes the theistic view of man’s origin from the non-theistic view, as well as from the various societal and cultural consequences distinguishing each belief. As John Quincy Adams warned long ago, without a belief in theistic origins—in that three percent difference—“man will have no conscience. He will have no other law than that of the tiger and the shark.”

Transcendency v. Relativism

If the human species is superior to other species, then, morally speaking, more should be expected from him than from other species. But what should be the standard for determining man’s morality? And what should be the authority for establishing the moral standards for man? And should those standards be established objectively or subjectively? The answers to these questions vary dramatically depending on whether a theistic or non-theistic approach is applied.

Under the theistic approach, man was not the source of the moral standards by which his conduct was to be governed. As James Wilson explained:

When we view the inanimate and irrational creation around and above us, and contemplate the beautiful order observed in all its motions and appearances, is not the supposition unnatural and improbable that the rational and moral world should be abandoned to the frolics of chance or to the ravage of disorder? What would be the fate of man and of society was every one at full liberty to do as he listed without any fixed rule or principle of conduct, without a helm to steer him—a sport of the fierce gusts of passion, and the fluctuating billows of caprice?

Blackstone had identified the source of what Wilson termed the “fixed rules or principles of conduct” which were to “steer” man:

Man, considered as a creature, must necessarily be subject to the laws of his creator, for he is entirely a dependant being. A being independent of any other has no rule to pursue but such as he prescribes to himself; but a state of dependence will inevitably oblige the inferior to take the will of Him on whom he depends as the rule of his conduct. . . . And consequently, as man depends absolutely upon his Maker for everything, it is necessary that he should in all points conform to his Maker’s will. This will of his maker is called the law of nature. . . . This law of nature, being coeval with mankind and dictated by God Himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original.

This “law of nature”—the “natural law” of which our framers so often spoke, and which they incorporated into our founding documents—was to be the basis for man’s moral standards. As Zephaniah Swift, author of America’s first legal text, explained:

[T]he transcendent excellence and boundless power of the Supreme Deity . . . impressed upon them [mankind] those general and immutable laws that will regulate their operation through the endless ages of eternity. . . . These general laws . . . are denominated the laws of nature.

Others were equally succinct that man’s moral conduct was to conform to the “natural law” established by the creator. For example:

In the supposed state of nature, all men are equally bound by the laws of nature, or to speak more properly, the laws of the creator. Samuel Adams

[T]he laws of nature and of nature’s God . . . of course presupposes the existence of a God, the moral ruler of the universe, and a rule of right and wrong, of just and unjust, binding upon man, preceding all institutions of human society and of government. John Quincy Adams

[The] “law of nature” is a rule of conduct arising out of the natural relations of human beings established by the creator and existing prior to any positive precept [human law]. . . . These . . . have been established by the creator. Noah Webster, legislator, judge

The natural law embodied transcendent values—values and truths which our framers described with adjectives such as “immutable,” “fixed,” “superior in obligation,” “paramount,” “binding upon man,” etc. These were principles and truths that, according to Montesquieu, “do not change”; or as Declaration signer Dr. Benjamin Rush had described it, it was a set of principles and laws “certain and universal in its operation upon all the

members of the community.” Commager summarized this view and its effect on American government and civilization:

[T]he laws of England, happily transferred to America, were patterned on the laws of nature. A generation bathed in the Enlightenment pledged its lives, its fortunes, and its sacred honor to the conviction that the laws of Nature and Nature’s God required American independence and justified faith in the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It was not surprising that Americans wrote natural law into their constitutions, enshrined it in their Bills of Rights, and pronounced it from their judicial tribunals. According to the philosophy of natural law, laws are discovered, not made. They are deduced from the nature of things rather than patterned on the needs of man.

Therefore, under transcendent values, there were objective standards for morality: that is, murder (as opposed, for example, to justifiable homicide or self-defense) was always wrong, as was theft, perjury, and so many other immutable values enshrined in the traditional common law. Darwin’s views, however, embodied a converse approach to values. As Professor James Rachels explains, Darwinism poses . . .

. . . a problem for traditional morality. Traditional morality, no less than traditional religion, assumes that man is a “great work.” It grants to humans a moral status superior to that of any other creatures on earth. It regards human life, and only human life, as sacred, and it takes the love of mankind as its first and noblest virtue. What becomes of all this, if man is but a modified ape?

Dr. David Wigdor, an analyst at Human Sciences Research, similarly affirms:

Natural law theorists argued that there were absolute, unchanging principles to which temporal laws must correspond. This doctrine of a higher law provided an alternative to the moral neutrality of the command theory, which accepted the legitimacy of any existing pattern of legal obligation. . . . Darwinism had undermined its [natural law’s] mechanical, formalistic elements, and apologists for business had discredited its claims to superior morality.

Leading legal theorists who acknowledged their debt to Darwin’s ideas quickly implemented into the legal arena (and therefore throughout society and culture) a new approach which rejected transcendent values. For example, Justice Benjamin Cardozo (1870-1938), declared that law must no longer “work from pre-established truths of universal and inflexible validity” because principles must “vary with changing circumstances” and “must be declared to be essentially relativistic.” And legal educator Roscoe Pound (1870-1964) similarly advocated that legal “principles are not absolute but are relative to time and place” because “ ‘nature’ did not mean to antiquity what it means to us who are under the influence of the idea of evolution.”

Objective standards for morality were therefore replaced by new values that, according to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841-1935), would now be based on “the felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories . . . [and] the prejudices which judges share with their fellowmen.” Quite simply, under the non-theistic paradigm, transcendent, immutable values do not exist because, as explained by Singer, “they draw on presuppositions—religious, moral, metaphysical—that are now obsolete.”

So, if man is not a unique species superior to the other species, and if there are no transcendent values to govern his behavior, what, then, is the standard for measuring his morality? From what source are his values to be derived? From the standards of behavior demonstrated by non-human animals—at least so say psychologists such as Dr. David Buss of the University of Texas, Dr. Randolph Neese of the University of Michigan, Dr. Douglas Kenrick of Arizona State, et al., from the emerging field known as evolutionary psychology.

Robert Wright, an award-winning writer of The Sciences magazine who has studied in depth the works and writings of evolutionary psychologists, summarizes their findings on what man can learn about his own behavior based, for example, on the sexual behavior of animals:

By studying how the process of natural selection shaped the mind, evolutionary psychologists are painting a new portrait of human nature, with fresh detail about the feelings and thoughts that draw us into marriage—or push us out. . . . According to evolutionary psychology, it is “natural” for both men and women—at some times, under some circumstances—to commit adultery or to sour on a mate, to suddenly find a spouse unattractive, irritating, wholly unreasonable. . . . The premise of evolutionary psychology is simple. The human mind, like any other organ, was designed for the purpose of transmitting genes to the next generation; the feelings and thoughts it creates are best understood in these terms. . . . Feelings of lust, no less than the sex organs, are here because they aided reproduction directly. . . . According to evolutionary psychologists, our everyday, ever shifting attitudes toward a mate or prospective mate—trust, suspicion, rhapsody, revulsion, warmth, iciness—are the handiwork of natural selection that remain with us today because in the past they led to behaviors that helped spread genes. . . . [And] while both sexes are prone under the right circumstances to infidelity, men seem much more deeply inclined to actually acquire a second or third mate—to keep a harem. They are also more inclined toward the casual fling. Men are less finicky about sex partners. . . . There is no dispute among evolutionary psychologists over the basic source of this male open-mindedness. A woman, regardless of how many sex partners she has, can generally have only one offspring a year. For a man, each new mate offers a real chance for pumping genes into the future. . . . Lifelong monogamous devotion just isn’t natural.

Darwin, by lowering the status of man to that of the animals, lowered the standard for human morality. As acknowledged by Professor James Rachels of UAB, “The whole idea of using animals as psychological models for humans is a consequence of Darwinism. Before Darwin, no one could have taken seriously the thought that we might learn something about the human mind by studying mere animals.”

Yet consider the implications: if man is to establish his moral standards based on those displayed by the animals, then not only will monogamy become the exception rather than the rule but also our laws on theft and murder eventually must be discarded, for in nature, “might makes right”—possession is based solely on whatever can be taken and held by force. The implications are frightening for a civilization governed by the “values” of evolutionary morality rather than by the transcendent, immutable values derived from theistic origins.

God-Given, Inalienable Rights v. Man-Created, Alienable Rights

From the belief that there were immutable and transcendent values proceeded the belief that there were corresponding immutable and transcendent rights—or what the framers called inalienable rights. As Constitution signer John Dickinson explained, an inalienable right was a right “which God gave to you and which no inferior power has a right to take away.” John Adams similarly attested that the inalienable rights of man were rights “antecedent to all earthly government; rights that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws; rights derived from the great Legislator of the universe.” It was from among such inalienable—or natural—rights that the framers specifically identified the right to life, liberty, property, self-protection, pursuit of happiness, etc.

Since, as John Adams explained, natural rights were not to be “repealed or restrained by human laws,” it was therefore—under the theistic view—the purpose of government to protect the natural rights that had been bestowed on man by his creator. As James Wilson confirmed, our government documents were drafted solely . . .

. . . to acquire a new security for the possession or the recovery of those rights to . . . which we were previously entitled by the immediate gift or by the unerring law of our all-wise and all-beneficent creator.

Wilson therefore concluded that “every government which has not this in view as its principal object is not a government of the legitimate kind.” Thomas Jefferson also asserted that government was “to declare and enforce only our natural rights and duties and to take none of them from us.” In fact, Jefferson even queried, “can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis: a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God?”

American government was built around the belief that there were inalienable rights that it was the purpose of government to protect, and those rights were protected so that man was free to enjoy the pursuit of happiness. As John Quincy Adams explained:

That bestowed as they [natural rights] were by God, their creator, they [humans] never could be divested of them, even by themselves, and much less could they be wrested from them by the might of others. . . . And hence the rights derived from it are declared to be inalienable. . . . And thus the acknowledgment of the unalienable right of man to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, is at the same time an acknowledgment of the omnipotence, the omniscience, and the all-pervading goodness of God. Man thus endowed is a being of loftier port, of larger dimensions, of infinitely increased and multiplied powers, and of heavier and deeper responsibilities than man invested with no such attributes or capacities. . . . Now the position to which I would invite your earnest and anxious consideration is this: That the form of government founded upon the principle of the natural equality of mankind, and of which the unalienable rights of individual man are the cornerstone, is the form of government best adapted to the pursuit of happiness as well of every individual as of the community. . . . and I think I am fully warranted in adding that in proportion as the existing governments of the earth approximate to or recede from that standard, in the same proportion is the pursuit of happiness of the community and of every individual belonging to it, promoted or impeded, accomplished or demolished.

However, under the new Darwinian view, the belief that there were certain rights of man which were to remain untouched by government was to change dramatically. In fact, Darwinian legal theorists began to assert that “[t]he fundamental weakness of conventional legal theory was its attempt to erect a closed system of immutable principles.” As Roscoe Pound asserted, “legal principles are not absolute but are relative to time and place” and “the fiction [of absolutes] should be discarded.” As he explained, “We are thinking of interests, claims, demands, not of rights.” (emphasis added)

Since it was thus deemed that there were no natural rights pertaining to man, then the natural law theory of absolute rights and wrongs came under attack. Vocal opponents like Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes “did not just refuse to acknowledge the influence of natural law; he attacked natural law jurisprudence repeatedly and effectively. . . . His intellectual activity contributed to the decline of natural law theory in this century.” With natural law discarded, there was no longer an inviolability for particular rights.

Perhaps the most perceptible illustration of this change in the role of government is seen in its approach to human life. As Dr. James Rachels insightfully observes:

The big issue in all this [Darwinism] is the value of human life. Darwin’s early readers—his friends as well as his enemies—worried that if they were to abandon the traditional conception of humans as exalted beings they could no longer justify the traditional belief in the value of human life. They were right to see this as a serious problem. The difficulty is that Darwinism leaves us with fewer resources from which to construct an account of the value of life.

The consequence is that, according to Rachels, not only will views toward life vis a vis abortion change but also a “revised view of such matters as suicide and euthanasia . . . will result.”

Formerly, a right to life was inalienable because it was bestowed upon man by a creator who had established that right superior to intrusion by government. Currently, however, the right to life, regardless of its stage of development or age, from conception to advanced seniority, is subject to the discretion of government. As a result, not only has abortion become acceptable but so has infanticide. And academicians are now advocating—and logically so—not only euthanasia but also the termination of those lives considered to be below “normal.” How are such policy positions reached?

First, it must be accepted that man, rather than a creator, has the right to determine the outcome of life for humans. Once that proposition is accepted, then a distinction is made between “humans” and “persons.” That is, it is asserted that although someone may be human, that does not mean he is a person—and only persons, rather than humans, should have a right to life. As a common example, the fact that a human fetus or a human embryo is acknowledged to be a human is not pertinent to the decision of whether it should be destroyed, for it clearly is not a “person.”