The Black Robed Regiment was the name that the British placed on the courageous and patriotic American clergy during the Founding Era (a backhanded reference to the black robes they wore).1 Significantly, the British blamed the Black Regiment for American Independence,2 and rightfully so, for modern historians have documented that:

There is not a right asserted in the Declaration of Independence which had not been discussed by the New England clergy before 1763.3

It is strange to today’s generation to think that the rights listed in the Declaration of Independence were nothing more than a listing of sermon topics that had been preached from the pulpit in the two decades leading up to the American Revolution, but such was the case.

Influence of The Clergy

But it was not just the British who saw the American pulpit as largely responsible for American independence and government, our own leaders agreed. For example, John Adams rejoiced that “the pulpits have thundered”4 and specifically identified several ministers as being among the “characters the most conspicuous, the most ardent, and influential” in the “awakening and a revival of American principles and feelings” that led to American independence.5

Across subsequent generations, the great and positive influence of the Revolutionary clergy was faithfully reported. For example:

As a body of men, the clergy were pre-eminent in their attachment to liberty. The pulpits of the land rang with the notes of freedom.6 The American Quarterly Register [MAGAZINE], 1833

If Christian ministers had not preached and prayed, there might have been no revolution as yet – or had it broken out, it might have been crushed.7 Bibliotheca Sacra [BRITISH PERIODICAL], 1856

The ministers of the Revolution were, like their Puritan predecessors, bold and fearless in the cause of their country. No class of men contributed more to carry forward the Revolution and to achieve our independence than did the ministers. . . . [B]y their prayers, patriotic sermons, and services [they] rendered the highest assistance to the civil government, the army, and the country.8 B. F. Morris, HISTORIAN, 1864

The Constitutional Convention and the written Constitution were the children of the pulpit.9 Alice Baldwin, HISTORIAN, 1918

Had ministers been the only spokesman of the rebellion – had Jefferson, the Adamses, and [James] Otis never appeared in print – the political thought of the Revolution would have followed almost exactly the same line. . . . In the sermons of the patriot ministers . . . we find expressed every possibly refinement of the reigning political faith.10 Clinton Rossiter, HISTORIAN, 1953

The American clergy were faithful exponents of the fullness of God’s Word, applying its principles to every aspect of life, thus shaping America’s institutes and culture. They were also at the forefront of proclaiming liberty, resisting tyranny, and opposing any encroachments on God-given rights and freedoms. In 1898, Methodist bishop and church historian Charles Galloway rightly observed of these ministers:

Mighty men they were, of iron nerve and strong hand and unblanched cheek and heart of flame. God needed not reeds shaken by the wind, not men clothed in soft raiment [Matthew 11:7-8], but heroes of hardihood and lofty courage. . . . And such were the sons of the mighty who responded to the Divine call.11

But the ministers during the Revolutionary period were not necessarily unique; they were simply continuing what ministers had been doing to shape American government and culture in the century and a half preceding the Revolution.

Clergy in American Colonies

For example, the early settlers who arrived in Virginia beginning in 1606 included ministers such as the Revs. Robert Hunt, Richard Burke, William Mease, Alexander Whitaker, William Wickham, and others. In 1619 they helped form America’s first representative government: the Virginia House of Burgesses, with its members elected from among the people.12 That legislature met in the Jamestown church and was opened with prayer by the Rev. Mr. Bucke; the elected legislators then sat in the church choir loft to conduct legislative business.13 As Bishop Galloway later observed:

[T]he first movement toward democracy in America was inaugurated in the house of God and with the blessing of the minister of God.14

In 1620, the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts to establish their colony. Their pastor, John Robinson, charged them to elect civil leaders who would not only seek the “common good” but who would also eliminate special privileges and status between governors and the governed15 – a radical departure from the practice in the rest of the world at that time. The Pilgrims eagerly took that message to heart, organizing a representative government and holding annual elections.16 By 1636, they had also enacted a citizens’ Bill of Rights – America’s first.17

In 1630, the Puritans arrived and founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and under the leadership of their ministers, they, too, established representative government with annual elections.18 By 1641, they also had established a Bill of Rights (the “Body of Liberties”)19 – a document of individual rights drafted by the Rev. Nathaniel Ward.20

In 1636, the Rev. Roger Williams established the Rhode Island Colony and its representative form of government,21 explaining that “the sovereign, original, and foundation of civil power lies in the people.”22

The same year, the Rev. Thomas Hooker (along with the Revs. Samuel Stone, John Davenport, and Theophilus Eaton) founded Connecticut.23 They not only established an elective form of government24 but in a 1638 sermon based on Deuteronomy 1:13 and Exodus 18:21, the Rev. Hooker explained the three Biblical principles that had guided the plan of government in Connecticut:

I. [T]he choice of public magistrates belongs unto the people by God’s own allowance.

II. The privilege of election . . . belongs to the people . . .

III. They who have power to appoint officers and magistrates [i.e., the people], it is in their power also to set the bounds and limitations of the power and place.25

Colonial Charters & Constitutions

From the Rev. Hooker’s teachings and leadership sprang the “Fundamental Orders of Connecticut” – America’s first written constitution (and the direct antecedent of the federal Constitution).26 But while Connecticut produced America’s first written constitution, it definitely had not produced America’s first written document of governance, for such written documents had been the norm for every colony founded by Bible-minded Christians. After all, this was the Scriptural model: God had given Moses a fixed written law to govern that nation – a pattern that recurred throughout the Scriptures (c.f., Deuteronomy 17:18-20, 31:24, II Chronicles 34:15-21, etc.). As renowned Cornell University professor Clinton Rossiter affirmed:

[T]he Bible gave a healthy spur to the belief in a written constitution. The Mosaic Code, too, was a higher law that men could live by – and appeal to – against the decrees and whims of ordinary men.27

Written documents of governance placed direct limitations on government and gave citizens maximum protection against the whims of selfish leaders. This practice of providing written documents had been the practice of American ministers before the Rev. Hooker’s constitution of 1638 and continued long after.

For example, in 1676, New Jersey was chartered and then divided into two religious sub-colonies: Puritan East Jersey and Quaker West Jersey; each had representative government with annual elections.28 The governing document for West Jersey was written by Christian minister William Penn. It declared:

We lay a foundation for after ages to understand their liberty . . . that they may not be brought in bondage but by their own consent, for we put the power in the people.29

Under Penn’s document . . .

Legislation was vested in a single assembly elected by all the inhabitants; the elections were to be by secret ballot; the principle of “No taxation without representation” was clearly asserted; freedom of conscience, trial by jury, and immunity from arrest without warrant were guaranteed.30

In 1681, Penn wrote the Frame of Government for Pennsylvania. It, too, established annual elections and provided numerous guarantees for citizen rights.31

Clergy Helped Secure Liberties

There are many additional examples, but it is indisputable that ministers played a critical role in instituting and securing many of America’s most significant civil rights and freedoms. As Founding Father Noah Webster affirmed:

The learned clergy . . . had great influence in founding the first genuine republican governments ever formed and which, with all the faults and defects of the men and their laws, were the best republican governments on earth. At this moment, the people of this country are indebted chiefly to their institutions for the rights and privileges which are enjoyed.32

Daniel Webster (the great “Defender of the Constitution”) agreed:

[T]o the free and universal reading of the Bible in that age men were much indebted for right views of civil liberty.33

Because Christian ministers established in America freedoms and opportunities not generally available even in the mother country of Great Britain, they were also at the forefront of resisting encroachments on the civil and religious liberties that they had helped secure.

For example, when crown-appointed Governor Edmund Andros tried to seize the charters of Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, revoke their representative governments, and force the establishment of the British Anglican Church upon them, opposition to Andros’ plan was led by the Revs. Samuel Willard, Increase Mather, and especially the Rev. John Wise.34 The Rev. Wise was even imprisoned by Andros for his resistance but he remained an unflinching voice for freedom, penning in 1710 and 1717 two works forcefully asserting that democracy was God’s ordained government in both Church and State,35 thus causing historians to title him “The Founder of American Democracy.”36

And when Governor Berkley refused to recognize Virginia’s self-government, Quaker minister William Edmundson and the Rev. Thomas Harrison led the opposition.37 When Governor Thomas Hutchinson ignored the elected Massachusetts legislature, the Rev. Dr. Samuel Cooper led the opposition.38 And a similar pattern was followed when Governor William Burnet dissolved the New Hampshire legislature, Governor Botetourt disbanded the Virginia House of Burgesses, Governor James Wright disbanded the Georgia Assembly, etc.

Leading To War for Independence

And because American preachers consistently opposed encroachments on civil and religious liberties, when the British imposed on Americans the 1765 Stamp Act (an early harbinger of the rupture between the two nations soon to follow), at the vanguard of the opposition to that act were the Revs. Andrew Eliot, Charles Chauncey, Samuel Cooper, Jonathan Mayhew, and George Whitefield39 (Whitefield even accompanied Benjamin Franklin to Parliament to protest the Act and assert colonial rights).40 In fact, one of the reasons that American resistance to the Stamp Act became so widespread was because the “clergy fanned the fire of resistance to the Stamp Act into a strong flame.”41

Five years later in 1770 when the British opened fire on their own citizens in the famous “Boston Massacre,” ministers again stepped to the forefront, boldly denouncing that abuse of power. A number of sermons were preached on the subject, including by the Revs. John Lathrop, Charles Chauncey, and Samuel Cooke;42 the Massachusetts House of Representatives even ordered that Rev. Cooke’s sermon be printed and distributed.43

As tensions with the British continued to grow, ministers such as the Rev. George Whitefield44 and the Rev. Timothy Dwight45 became some of the earliest leaders to advocate America’s separation from Great Britain.

There are many additional examples, but the historical records respecting the leadership of the clergy were so clear that in 1851, distinguished historian Benson Lossing concluded:

[T]he Puritan preachers also promulgated the doctrine of civil liberty – that the sovereign was amenable to the tribunal of public opinion and ought to conform in practice to the expressed will of the majority of the people. By degrees their pulpits became the tribunes of the common people; and . . . on all occasions, the Puritan ministers were the bold asserters of that freedom which the American Revolution established.46

Clergy Fight in the War

However, Christian ministers did not just teach the principles that led to independence, they also participated on the battlefield to secure that independence. One of the numerous examples is the Rev. Jonas Clark.

When Paul Revere set off on his famous ride, it was to the home of the Rev. Clark in Lexington that he rode. Patriot leaders John Hancock and Samuel Adams were lodging (as they often did) with the Rev. Clark. After learning of the approaching British forces, Hancock and Adams turned to Pastor Clark and inquired of him whether the people were ready to fight. Clark unhesitatingly replied, “I have trained them for this very hour!”47 When the original alarm sounded in Lexington to warn of the oncoming British menace, citizens gathered at the town green, and according to early historian Joel Headley:

There they found their pastor the [Rev. Clark] who had arrived before them. The roll was called and a hundred and fifty answered to their names . . . . The church, the pastor, and his congregation thus standing together in the dim light [awaiting the Redcoats], while the stars looked tranquilly down from the sky above them.48

The British did not appear at that first alarm, and the people returned home. At the subsequent alarm, they reassembled, and once the sound of the battle subsided, some eighteen Americans lay on Lexington Green; seven were dead – all from the Rev. Clark’s church.49 Headley therefore concluded, “The teachings of the pulpit of Lexington caused the first blow to be struck for American Independence,”50 and historian James Adams added that “the patriotic preaching of the Reverend Jonas Clark primed those guns.”51

When the British troops left Lexington, they fought at Concord Bridge and then headed back to Boston, encountering increasing American resistance on their return. Significantly, many who awaited the British along the road were local pastors (such as the Rev. Phillips Payson52 and the Rev. Benjamin Balch53) who had heard of the unprovoked British attack on the Americans, taken up their own arms, and then rallied their congregations to meet the returning British. As word of the attack spread wider, pastors from other areas also responded.

For example, when word reached Vermont, the Rev. David Avery promptly gathered twenty men and marched toward Boston, recruiting additional troops along the way,54 and the Rev. Stephen Farrar of New Hampshire led 97 of his parishioners to Boston.55 The ranks of resistance to the British swelled through the efforts of Christian ministers who “were far more effective than army recruiters in rounding up citizen-soldiers.”56

Weeks later when the Americans fought the British at Bunker Hill, American ministers again delved headlong into the fray. For example, when the Rev. David Grosvenor heard that the battle had commenced, he left from his pulpit – rifle in hand – and promptly marched to the scene of action,57 as did the Rev. Jonathan French.58

This pattern was common through the Revolution – as when the Rev. Thomas Reed marched to the defense of Philadelphia against British General Howe;59 the Rev. John Steele led American forces in attacking the British;60 the Rev. Isaac Lewis helped lead the resistance to the British landing at Norwalk, Connecticut;61 the Rev. Joseph Willard raised two full companies and then marched with them to battle;62 the Rev. James Latta, when many of his parishioners were drafted, joined with them as a common soldier;63 and the Rev. William Graham joined the military as a rifleman in order to encourage others in his parish to do the same64. Furthermore:

Of Rev. John Craighead it is said that “he fought and preached alternately.” Rev. Dr. Cooper was captain of a military company. Rev. John Blair Smith, president of Hampden-Sidney College, was captain of a company that rallied to support the retreating Americans after the battle of Cowpens. Rev. James Hall commanded a company that armed against Cornwallis. Rev. William Graham rallied his own neighbors to dispute the passage of Rockfish Gap with Tarleton and his British dragoons.65

Clergy Targeted by British

There are many additional examples. No wonder the British dubbed the patriotic American clergy the “Black Regiment.”66 But because of their strong leadership, ministers were often targeted by the British. As Headley confirms:

[T]here was a class of clergymen and chaplains in the Revolution whom the British, when they once laid hands on them, treated with the most barbarous severity. Dreading them for the influence they wielded and hating them for the obstinacy, courage, and enthusiasm they infused into the rebels, they violated all the usages of war among civilized nations in order to inflict punishment upon them.67

Among these was the Rev. Naphtali Daggett, President of Yale. When the British approached New Haven to enter private homes and desecrate property and belongings, Daggett offered stiff and at times almost single-handed resistance to the British invasion, standing alone on a hillside, repeatedly firing his rifle down at the hundreds of British troops below. Eventually captured, over a period of several hours the British stabbed and pricked Daggett multiple times with their bayonets. Local townspeople lobbied the British and eventually secured the release of the preacher, but Daggett never recovered from those wounds, which eventually caused his death.68 When the Rev. James Caldwell offered similar resistance in New Jersey, the British burned his church and he and his family were murdered.69

The British abused, killed, or imprisoned many other clergymen,70 who often suffered harsher treatment and more severe penalties than did ordinary imprisoned soldiers.71 But the British targeted not just ministers but also their churches. As a result, of the nineteen church buildings in New York City, ten were destroyed by the British,72 and most of the churches in Virginia suffered the same fate.73 This pattern was repeated throughout many other parts of the country.

John Wise

Truly, Christian ministers provided courageous leadership throughout the Revolution, and as briefly noted earlier, they had also been largely responsible for laying its intellectual foundation. To understand more of their influence, consider the Rev. John Wise.

As early as 1687, the Rev. Wise was already teaching that “taxation without representation is tyranny,”74 the “consent of the governed” was the foundation of government,75 and that “every man must be acknowledged equal to every man.”76 In 1772 with the Revolution on the horizon, two of Wise’s works were reprinted by leading patriots and the Sons of Liberty to refresh America’s understanding of the core Biblical principles of government.77 (The first printing sold so fast that a quick second reprint was quickly issued.78) Significantly, many of the specific points made by Wise in that work subsequently appeared four years later in the very language of the Declaration of Independence. As historian Benjamin Morris affirmed in 1864:

[S]ome of the most glittering sentences in the immortal Declaration of Independence are almost literal quotations from this [1772 reprinted] essay of John Wise. . . . It was used as a political text-book in the great struggle for freedom.79

And decades later when President Calvin Coolidge delivered a 1926 speech in Philadelphia on the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, he similarly acknowledged:

The thoughts [in the Declaration] can very largely be traced back to what John Wise was writing in 1710.80

It was Christian ministers such as John Wise (and scores like him) who, through their writings and countless sermons (such as their Election Sermons and other sermons on the Biblical principles of government) laid the intellectual basis for American Independence.

Clergy Involvement in Politics

Christian clergy largely defined America’s unique political theory and even defended it in military combat, but they were also leaders in the national legislative councils in order to help implement what they had conceived and birthed. For example, the Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon was a member of the Continental Congress who served during the Revolution on the Board of War as well as on over 100 congressional committees.81 Other ministers who served in the Continental Congress included the Revs. Joseph Montgomery, Hugh Williamson, John Zubly, and more.

Numerous ministers also served in state legislatures – such as the Rev. Jacob Green of New Jersey, who helped set aside the British government in that state and was made chairman of the committee that drafted the state’s original constitution in 1776;82 the Rev. Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg, who helped draft Pennsylvania’s 1776 constitution;83 the Rev. Samuel Stillman, who helped draft Massachusetts’ 1780 constitution;84 etc.

When hostilities ceased at the end of the Revolution, Christian ministers led in the movement for a federal constitution. For example, the Revs. Jeremy Belknap, Samuel Stanhope Smith, John Witherspoon, and James Manning began pointing out the defects of the Articles of Confederation,85 and when the Constitution was finally complete and submitted to the states for ratification, nearly four dozen clergymen were elected as ratifying delegates,86 many of whom played key roles in securing its adoption in their respective states.

Following the adoption of the new federal Constitution, ministers were highly active in celebrating its ratification. For example, of the parade in Philadelphia, signer of the Declaration Benjamin Rush happily reported:

The clergy formed a very agreeable part of the procession. They manifested by their attendance their sense of the connection between religion and good government. They. . . . marched arm in arm with each other to exemplify the Union.87

When the first federal Congress under the new Constitution convened, several ministers were Members, including the Revs. Frederick Augustus and John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg, Abiel Foster, Benjamin Contee, Abraham Baldwin, and Paine Wingate.

Lasting Influence of American Ministers

Ministers were intimately involved in every aspect of introducing, defining, and securing America’s civil and religious liberties. A 1789 Washington, D. C., newspaper therefore proudly reported:

[O]ur truly patriotic clergy boldly and zealously stepped forth and bravely stood our distinguished sentinels to watch and warn us against approaching danger; they wisely saw that our religious and civil liberties were inseparably connected and therefore warmly excited and animated the people resolutely to oppose and repel every hostile invader. . . . [M]ay the virtue, zeal and patriotism of our clergy be ever particularly remembered.88

Incidentally, besides their contributions to government and civil and religious liberty, the Black Robed Regiment was also largely responsible for education in America. Ministers, understanding that only a literate people well versed in the teachings of the Bible could sustain free and enlightened government, therefore established an education system that would teach and preserve the religious principles so indispensable to the civil and religious liberties they forcefully advocated.

Consequently, in 1635 the Puritans established America’s first public school,89 and in 1647 passed America’ first public education law (“The Old Deluder Satan Act”90). And Harvard University was founded through the direction of Puritan minister John Harvard;91 Yale was founded by ten congregational ministers;92 Princeton by Presbyterian ministers Jonathan Dickinson, John Pierson, and Ebenezer Pemberton;93 William and Mary by Episcopal minister James Blair;94 Dartmouth by Congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock;95 etc.

This trend of Gospel ministers founding and leading American educational institutions continued for the next two-and-a-half centuries, and by 1860, ninety-one percent of all college presidents were ministers of the Gospel – as were more than a third of all university faculty members.96 Of the 246 colleges founded by the close of that year, only seventeen were not affiliated with some denomination;97 and by 1884, eighty-three percent of America’s 370 colleges still remained denominational colleges.98 As Founding Father Noah Webster (the “Schoolmaster to America”) affirmed, “to them [the clergy] is popular education in this country more indebted than to any other class of men.”99

Conclusion

In short, history demonstrates that America’s elective governments, her educational system, and many other positive aspects of American life and culture were the product of Biblical-thinking Christian clergy and leaders. Today, however, as the influence of the clergy has waned, many of these institutions have come under unprecedented attack and many of our traditional freedoms have been significantly eroded. It is time for America’s clergy to understand and reclaim the important position of influence they have been given. As the Rev. Charles Finney – a leader of the Second Great Awakening – reminded ministers in his day:

Brethren, our preaching will bear its legitimate fruits. If immorality prevails in the land, the fault is ours in a great degree. If there is a decay of conscience, the pulpit is responsible for it. If the public press lacks moral discrimination, the pulpit is responsible for it. If the church is degenerate and worldly, the pulpit is responsible for it. If the world loses its interest in religion, the pulpit is responsible for it. If Satan rules in our halls of legislation, the pulpit is responsible for it. If our politics become so corrupt that the very foundations of our government are ready to fall away, the pulpit is responsible for it. Let us not ignore this fact, my dear brethren; but let us lay it to heart, and be thoroughly awake to our responsibility in respect to the morals of this nation.100

America once again needs the type of courageous ministers described by Bishop Galloway:

Mighty men they were, of iron nerve and strong hand and unblanched cheek and heart of flame. God needed not reeds shaken by the wind, not men clothed in soft raiment [Matthew 11:7-8], but heroes of hardihood and lofty courage. . . .And such were the sons of the mighty who responded to the Divine call.101

It is time to reinvigorate the Black Robed Regiment!

Endnotes

1 Boston Gazette, December 7, 1772, article by “Israelite,” and Boston Weekly Newsletter, January 11, 1776, article by Peter Oliver, British official. See also Peter Oliver, Peter Oliver’s Origin & Progress of the American Rebellion, eds. Douglas Adair and John A. Schutz (San Marino California: The Huntington Library, 1961), 29, 41-45; Carl Bridenbaugh, Mitre and Sceptre (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962), 334; Alice M. Baldwin, The New England Clergy and the American Revolution (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1958), 98, 155.

2 Alpheus Packard, “Nationality,” Bibliotheca Sacra and American Biblical Repository (London: Andover: Warren F. Draper, 1856), XIII:193, Article VI. See also Benjamin Franklin Morris, Christian Life and Character of the Civil Institutions of the United States (Philadelphia: George W. Childs, 1864), 334-335.

3 Baldwin, New England Clergy (1958), 170.

4 John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1851), III:476, “The Earl of Clarendon to William Pym,” January 20, 1766.

5 Adams, Works, ed. Adams (1850), X:284, to Hezekiah Niles, February 13, 1818; X:271-272, to William Wirt, January 5, 1818.

6 “History of Revivals of Religion, From the Settlement of the Country to the Present Time,” The American Quarterly Register (Boston: Perkins and Marvin, 1833), 5:217; Morris, Christian Life and Character (1864), 334-335.

7 Alpheus Packard, “Nationality,” Bibliotheca Sacra (1856), XIII:193, Article VI; Morris, Christian Life and Character (1864), 334-335.

8 Morris, Christian Life and Character (1864), 334-335.

9 Baldwin, New England Clergy (1958), 134.

10 Clinton Rossiter, Seedtime of the Republic (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1953), 328-329.

11 Charles B. Galloway, Christianity and the American Commonwealth (Nashville, TN: Publishing House Methodist Episcopal Church, 1898), 77.

12 “The First Legislative Assembly at Jamestown, Virginia,” September 4, 2022, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/the-first-legislative-assembly.htm.

13 Galloway, Christianity (1898), 1131-114; John Fiske, Civil Government in the United States Considered with some Reference to Its Origins (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1890), 146.

14 Galloway, Christianity (1898), 114.

15 Old South Leaflets (Boston: Directors of the Old South Work), 372, “Words of John Robinson (1620)”; “John Robinson’s Farewell Letter to the Pilgrims, July 1620,” Pilgrim Hall Museum, https://pilgrimhall.org/pdf/John_Robinson_Farewell_Letter_to_Pilgrims.pdf.

16 “Plymouth Colony Legal Structure,”1998, Plymouth Colony Archive Project, http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/ccflaw.html; Robert Baird, Religion in America (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1845), 51.

17 “Plymouth Colony Legal Structure,”1998, Plymouth Colony Archive Project, http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/ccflaw.html.

18 Henry William Elson, History of the United States of America (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1904), Ch. IV, 103-111.

19 “Plymouth Colony Legal Structure,”1998, Plymouth Colony Archive Project, http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/ccflaw.html.

20 George Bancroft, History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1858), I:416-417; Galloway, Christianity (1898), 124-125; Old South Leaflets, 261-280, “The Body of Liberties: The Liberties of the Massachusetts Colonie in New England, 1641.”

21 “Charter of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,” July 15, 1663, The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/ri04.asp.

22 Baldwin, New England Clergy (1958), 27, quoting Roger Williams’ The Bloody Tenet, 137, quoted by Isaac Backus, Church History of New England, I. 62 of 1839.

23 “Timeline: Settlement of the Colony of Connecticut,” Connecticut History Online, May 26, 2021, https://connecticuthistory.org/timeline-settlement-of-the-colony-of-connecticut/.

24 The Federal and State Constitutions, Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws, ed. Francis Newton Thorpe (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), 1:534, “Charter of Connecticut-1662.”

25 Rossiter, Seedtime (1953), 171.

26 John Fiske, The Beginnings of New England (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1898), 127-128.

27 Rossiter, Seedtime (1953), 32.; J. M. Mathews, The Bible and Civil Government, in a Course of Lectures (New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1851), 67-68.

28 “Province of West New Jersey in America,” November 25, 1681, Art. I, The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nj08.asp; “The Fundamental Constitutions for the Province of East New Jersey in America, Anno Domini 1683,” Art. II-III, The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nj10.asp.

29 Ernest Sutherland Bates, American Faith (New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 1940), 186-187.

30 Bates, American Faith (1940), 186-187.

31 “Charter for the Province of Pennsylvannia-1681,” The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/pa01.asp.

32 Noah Webster, Letters of Noah Webster, ed. Harry R. Warfel (New York: Library Publishers, 1953), 455, to David McClure, October 25, 1836.

33 Daniel Webster, Address Delivered at Bunker Hill, June 17, 1843, on the Completion of the Monument (Boston: T. R. Marvin, 1843), 31.

34 Fiske, Beginnings of New England (1898), 267-272.

35 John Wise, A Vindication of the Government of New- England Churches (Boston: John Boyles, 1772), 45.

36 J. M. Mackaye, “The Founder of American Democracy,” The New England Magazine (September 1903), XXIX:1:73-83.

37 John Fiske, Old Virginia and Her Neighbors (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1901), II:57 & I:306, 311.

38 Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930), s.v. “Samuel Cooper.”

39 Baldwin, New England Clergy (1958), 90; Stephen Mansfield, Forgotten Founding Father: The Heroic Legacy of George Whitefield (Cumberland House, 2001), 112.

40 Mansfield, Forgotten Founding Father (2001), 112.

41 Baldwin, New England Clergy (1958), 30.

42 Claude H. Van Tyne, The Causes of the War of Independence (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922), 362.

43 John Wingate Thornton, Pulpit of the American Revolution (Boston: Gould and Lincoln, 1860), 147-148; Van Tyne, Causes of the War of Independence (1922), 362.

44 Bancroft, History of the United States (1858), V:193.

45 Morris, Christian Life and Character (1864), 367-368.

46 Benjamin Lossing, Pictorial Fieldbook of the Revolution (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1851), I:440.

47 Franklin Cole, They Preached Liberty (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1941), 34.

48 J. T. Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864), 79.

49 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 79-82

50 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 82.

51 James L. Adams, Yankee Doodle Went to Church: The Righteous Revolution of 1776 (Old Tappan, NJ: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1989), 22.

52 Cole, They Preached Liberty (1941), 36.

53 Cole, They Preached Liberty (1941), 36.

54 Cole, They Preached Liberty (1941), 36.

55 Cole, They Preached Liberty (1941), 36.

56 Adams, Yankee Doodle (1989), 153.

57 Cole, They Preached Liberty (1941), 36.

58 Cole, They Preached Liberty (1941), 36.

59 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 68.

60 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 69; Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, s.v. “John Steele.”

61 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 71-72.

62 Cole, They Preached Liberty (1941), 36.

63 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 72.

64 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 69.

65 Daniel Dorchester, Christianity in the United States from the First Settlement Down to the Present Time (New York: Phillips & Hunt, 1888), 265.

66 Boston Gazette, December 7, 1772, article by “Israelite,” and Boston Weekly Newsletter, January 11, 1776, article by Peter Oliver, British official. See also Oliver, Peter Oliver’s Origin & Progress, eds. Adair and Schutz (1961), 29, 41-45; Bridenbaugh, Mitre and Sceptre (1962), 334; Baldwin, New England Clergy (1958), 98, 155.

67 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 58.

68 William Buell Sprague, Annals of the American Pulpit: Trinitarian Congregation (New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1857), 482.

69 Morris, Christian Life and Character (1864), 350.

70 Dorchester, Christianity in the United States (1888), 265.

71 Headley, Chaplains and Clergy (1864), 58.

72 Dorchester, Christianity in the United States (1888), 266.

73 Dorchester, Christianity in the United States (1888), 267.

74 Linda Stewart, “The Other Cape,” April 2001, American Heritage, https://www.americanheritage.com/other-cape.

75 Rossiter, Seedtime (1953), 219.

76 J. M. Mackaye, “The Founder of American Democracy,” The New England Magazine (September 1903), XXIX:1:73-83.

77 J. M. Mackaye, “The Founder of American Democracy,” The New England Magazine (September 1903), XXIX:1:73-83.

78 Van Tyne, Causes of the War of Independence (1922), I:357.

79 Wise, Vindication of the Government of New England Churches: and the Churches’ Quarrel Espoused (Boston: Congregational Board of Publication, 1860), xx-xxi, “Introductory Remarks” by Rev. J. S. Clark; Morris, Christian Life and Character (1864), 341

80 Calvin Coolidge, “Speech on the One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence,” July 5, 1926, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/267359.

81 Political Sermons of the American Founding Era: 1730-1805, ed. Ellis Sandoz (Indianapolis, Liberty Fund: 1998), 1:530, from Sermons 17 on John Witherspoon intro.

82 Morris, Christian Life and Character (1864), 366.

83 William Warren Sweet, The Story of Religion in America (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1950), 182.

84 Frank Moore, Patriot Preachers of the American Revolution (Boston: Gould and Lincoln: 1860), 260.

85 James Hutchinson Smylie, American Clergymen and the Constitution of the United States of America (New Jersey: Princeton Theological Seminary, doctoral dissertation 1958), 127-129, 139, 143.

86 John Eidsmoe, Christianity and the Constitution (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1987), 352, n.15.

87 Benjamin Rush, Letters of Benjamin Rush, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Princeton: American Philosophical Society, 1951), I:474, to Elias Boudinot, “Observations on the Federal Procession in Philadelphia,” July 9, 1788.

88 Gazette of the United States (Washington, D.C.: May 9, 1789), 1, quoting from “Extract from “American Essays: The Importance of the Protestant Religion Politically Considered.”

89 “BLS History,” Boston Latin School, accessed June 4, 2024, https://www.bls.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=206116&type=d.

90 The Code of 1650, Being a Compilation of the Earliest Laws and Orders of the General Court of Connecticut (Hartford: Silus Andrus, 1822), 90-92; Church of the Holy Trinity v. U. S., 143 U. S. 457, 467 (1892).

91 Appleton‘s Cyclopedia of American Biography (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1888), s.v. “John Harvard.”

92 Noah Webster, Letters to a Young Gentleman Commencing His Education (New Haven: Howe & Spalding, 1823), 237.

93 John Maclean, History of the College of New Jersey, from its Origin in 1746 to the Commencement of 1854 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1877), I:70.

94 The History of the College of William and Mary, from its Foundation, 1660, to 1874 (Richmond, VA: J.W. Randolph & English, 1874), 95.

95 “Eleazar Wheelock,” Dartmouth, accessed June 4, 2024, https://president.dartmouth.edu/people/eleazar-wheelock.

96 Warren A. Nord, Religion & American Education (North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 84, quoting from James Tunstead Burtchaell, “The Decline and Fall of the Christian College I,” First Things, May 1991, p. 24; George Marsden, The Soul of the American University (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 11; Galloway, Christianity (1898), 198.

97 E. P. Cubberley, Public Education in the United States (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin Co., 1919), 204; Luther A. Weigle, The Pageant of America: American Idealism, ed. Ralph Henry Gabriel (Yale University Press, 1928), X:315.

98 Galloway, Christianity (1898), 209-210.

99 Noah Webster, A Collection of Papers on Political, Literary, and Moral Subjects (New York: Webster and Clark, 1843), 293, from his “Reply to a Letter of David McClure on the Subject of the Proper Course of Study in the Girard College, Philadelphia. New Haven, October 25, 1836.”

100 The Christian Treasury Containing Contributions from Ministers and Members of Various Evangelical Denominations (Edinburgh: Johnstone, Hunter and Co., 1877), 203.

101 Galloway, Christianity (1898), 77.

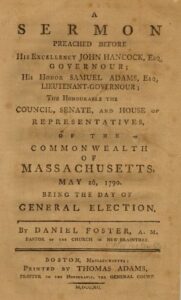

These sermons were preached to government officials at the state capitol upon the annual opening of the legislature

These sermons were preached to government officials at the state capitol upon the annual opening of the legislature The American practice of calling days of fasting or thanksgiving was so strong that by 1815, civil governments had issued at least 1,400 official prayer proclamations. Thousands more have been issued since that time—a tradition that now spans more than four centuries of the American Story, and one that continues to the present day since a 1952 federal law requires that every president issue a prayer proclamation on the National Day of Prayer, commemorated the first Thursday of every May, and observed by every president since Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The American practice of calling days of fasting or thanksgiving was so strong that by 1815, civil governments had issued at least 1,400 official prayer proclamations. Thousands more have been issued since that time—a tradition that now spans more than four centuries of the American Story, and one that continues to the present day since a 1952 federal law requires that every president issue a prayer proclamation on the National Day of Prayer, commemorated the first Thursday of every May, and observed by every president since Dwight D. Eisenhower.