Introduction

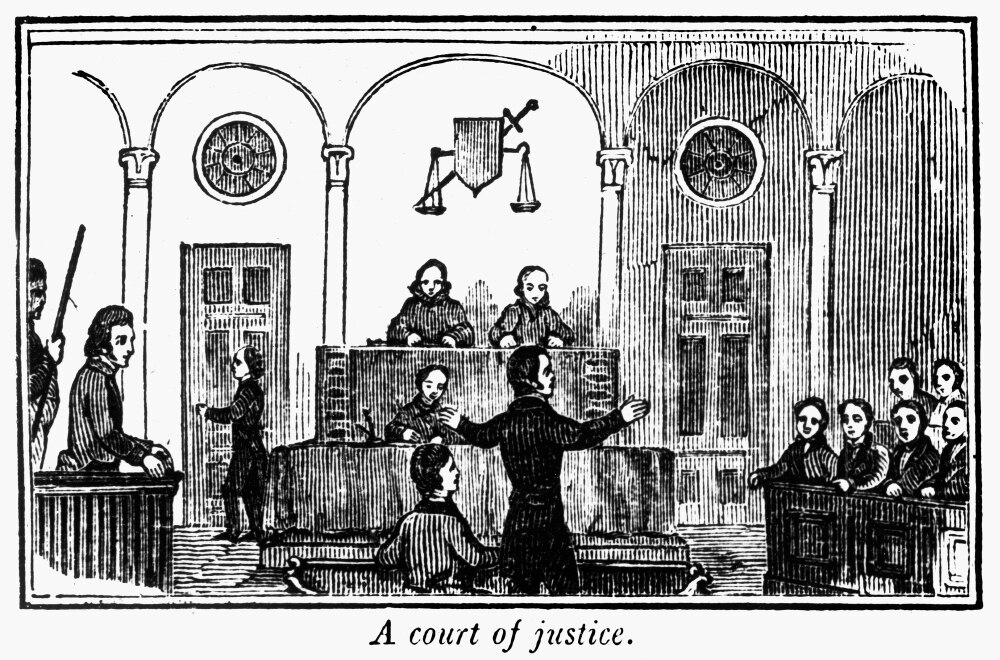

Since much public policy is now created by the judiciary, the federal judicial system in America receives increasingly more attention from politicos, pundits, and reporters. Federal judicial appointments are often closely watched, as are cases at the US Supreme Court. Yet despite the attention, the original intent of the judiciary is not well understood today. And ironically, although 90 percent of all cases are heard at the state rather than the federal level,[i] the role and operation of the state judicial system is almost completely overlooked. With so much resting on state courts, how those judges are selected is undeniably important. Texas has recently become a center of attention for this issue.

Texas currently selects its judges by a vote of citizens through popular elections, but some want this to change. Due to the rise of Democratic voters in the larger urban areas of the state (such as Dallas and Houston), some Republican-leaning groups are urging a move away from allowing the people to choose their judges. Instead they urge the adoption of what has become known as the “Missouri Plan” (also known as “Merit Selection” or “Assisted Selection”), which eliminates contested judicial elections. However, as will be documented below, this so-called “Merit Selection” is based on subjective personal opinions rather than any objective standard of measurement. Instead of advancing well-prepared constitutional judges to seats, the “Missouri Plan” consolidates power into the hands of an unelected and unaccountable group of administrators, making the state judiciary more partisan and polarized.

Before examining the results of Merit Selection in other states, how does the plan work? While there is some difference in the way various states employ this system, the overarching details are similar. A small group of undemocratically appointed commissioners of supposed elite legal “experts” choose a tiny handful of nominees for a particular judgeship. The governor then picks one of those privately-selected nominees to become judge, and that largely ends the process.

But who are these “experts” that choose a state’s judges for the people of that state? In some states, the members of that small nominating commission are appointed by the governor, but usually the private state bar, legal associations, the legislature, the governor, and sometimes sitting judges split the choice of commissioners. Nearly 75% of the board members end up being lawyers,[ii] which has become such a problem that some states have passed laws limiting the number of attorneys that may be appointed. Texas is now being urged to accept this system as a replacement for having voters choose the judges who will rule over them.

Texas, The Nation, And Various Other Methods

A prominent group arguing for this shift is Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR), an organization that has achieved many good things in the past, including major substantive tort reform. On its website, TLR explains why Texans should no longer be allowed to choose their judges:

A prominent group arguing for this shift is Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR), an organization that has achieved many good things in the past, including major substantive tort reform. On its website, TLR explains why Texans should no longer be allowed to choose their judges:

Texas is one of only a few states that elects its judges.[1] Because there are often so many judges on the ballot and because these are often lower-profile election contests, many Texans simply don’t have enough knowledge about the candidates for judicial office to make informed decisions. Many voters cast their votes for judges based on party affiliation or name recognition, since they have no knowledge of the relative merits of the candidates. Historically, this has led to groups of long-serving, competent, experienced judges being swept out of office based on nothing other than partisan affiliation.[iii] (emphasis added)

Their aim is to prevent larger blue cities from electing an increasing number of Democrat judges rather than Republican ones by moving Texas away from democratically contested elections. But before examining whether adopting the Missouri Plan (or any of its derivatives) would be good for Texas, it is worthwhile to review the six different types of state judicial selection systems currently in use.

Nonpartisan Elections:

Used by 15 states, this is the most popular method. These are contested races in which judicial candidates do not formally identify with any official party—Democrat, Republican, or otherwise. This is done in hopes of encouraging voters to look deeper into the candidates’ actual record on issues and past a simple party designation. (The first non-partisan judicial election took place in 1873.[iv])

The Missouri Plan (Assisted Appointment, Merit System)

The second most popular system is the Missouri Plan, with a total of 14 states employing it at the State Supreme Court level. Begun in Missouri in 1940, it expanded rapidly, but since 1994 states have stopped adopting it, opting instead to retain their older systems.[v]

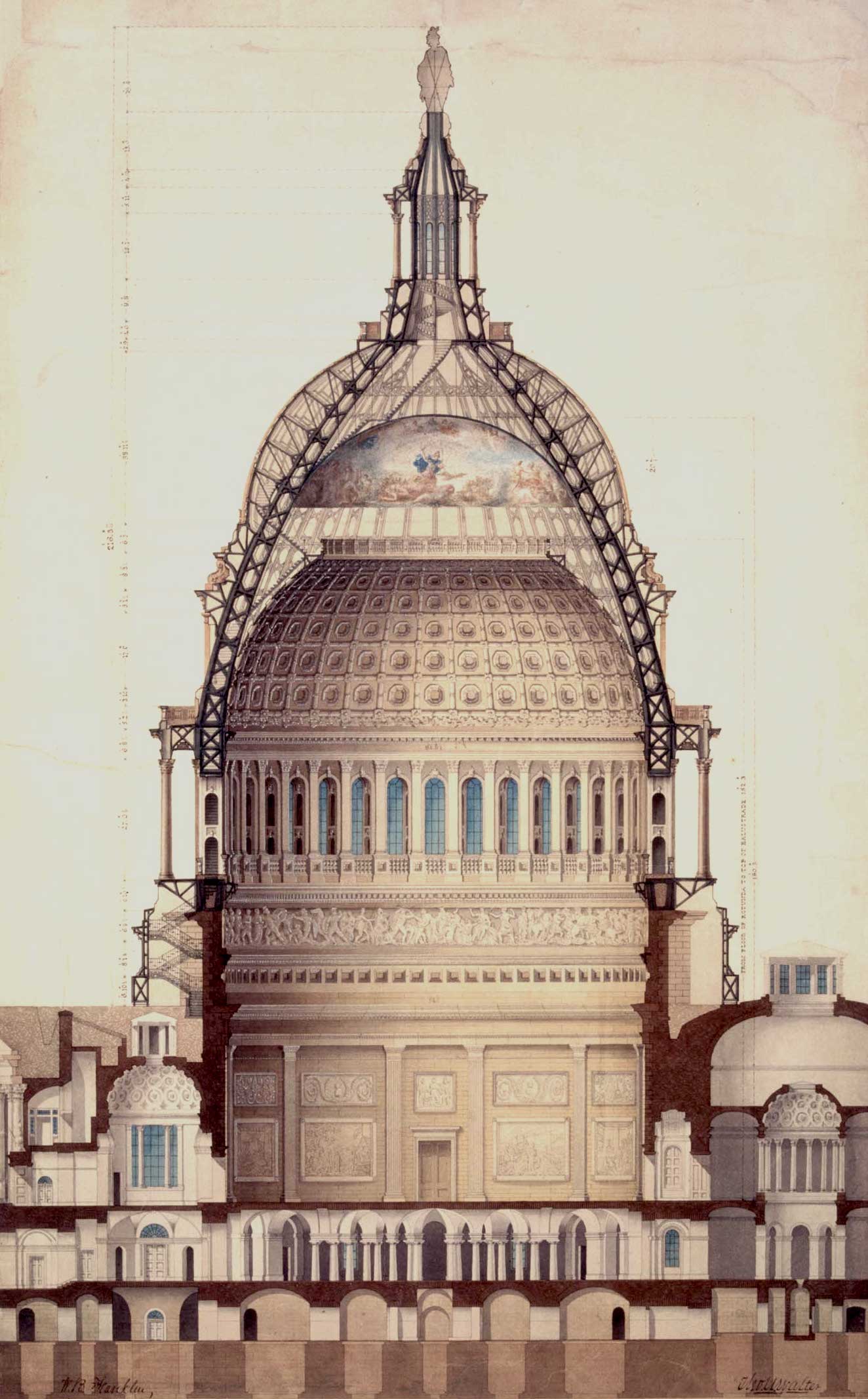

Gubernatorial Appointment

Also known as the federal model, the governor makes judicial appointments that then go before the legislative branch for confirmation. This method is currently used by 10 states, especially in the New England area. Originally, every new state that entered the Union after 1789 adopted the federal model but by the mid-to-late-1800s, most had moved to popular elections. In fact, since 1847, Hawaii has been the only state to enter the Union and select the federal model; the rest have opted for some form of citizen elections.[vi]

Partisan Elections

In 1832, Mississippi first moved away from the federal model and adopted partisan elections. New York followed suit in 1846, and then most of the rest of the nation.[vii] By the time the Civil War was fully underway, 70 percent of the states used contested partisan judicial elections,[viii] but some have since chosen other elections.

Hybrid

California, Maryland, and New Mexico use a hybrid system that merges the Missouri Plan with elements of the federal model—notably legislative confirmation. This retains at least a portion of the original constitutional checks and balances, but like the full-blown Missouri Plan, it often utilizes methods that keep the process of choosing judges excluded from the public.

Legislative Appointment

Used only in Virginia and South Carolina, this is the least common system. The legislature selects judges in a manner similar to the way Senators were chosen for the US Senate prior to the addition of the 17th Amendment to the Constitution in 1913, and has the option of reappointing those judges once their initial term has been completed.[ix]

The Philosophy Behind the Missouri Plan

With the push to adopt the Missouri Plan/Merit Selection in Texas, it is important to examine whether it justifies abandoning longstanding citizen voting traditions. Supporters offer two primary reasons for adopting a new system.

The first argument was presented above by Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR): “Texans simply don’t have enough knowledge” to make “informed decisions.”[x] This premise leads them to conclude that an unelected body of supposed experts (on whom TLR hopes to have substantial influence) is more likely to choose the type of judges TLR would prefer to have on the bench.

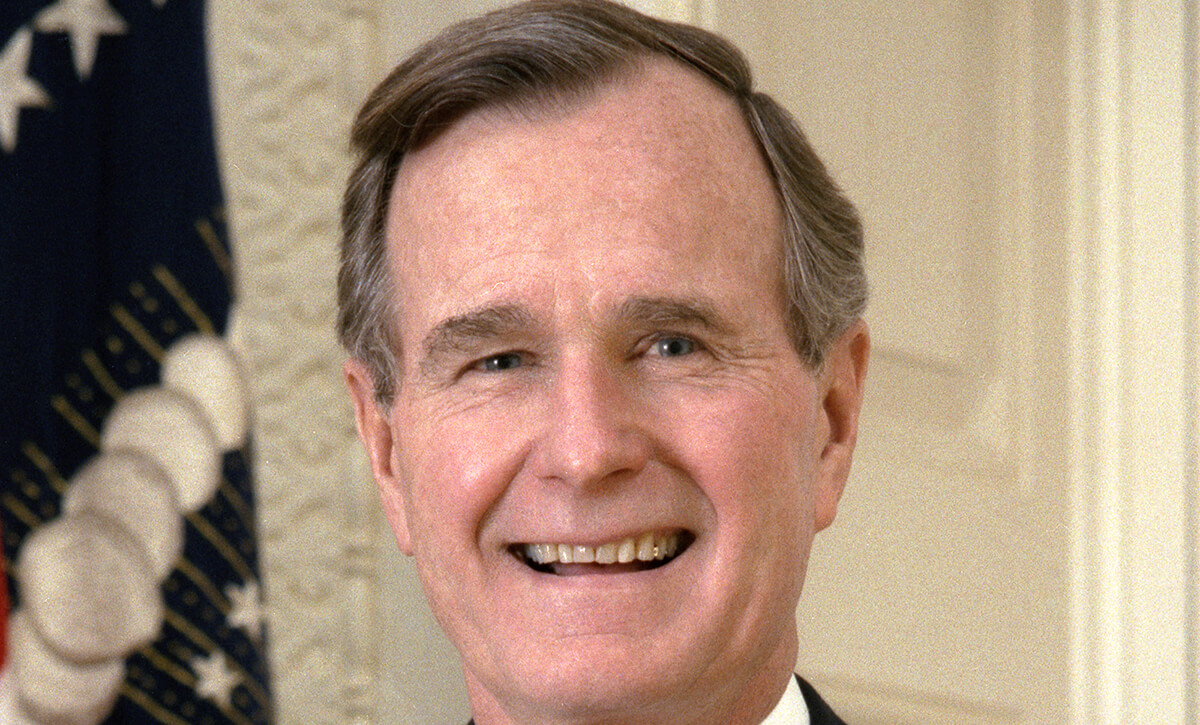

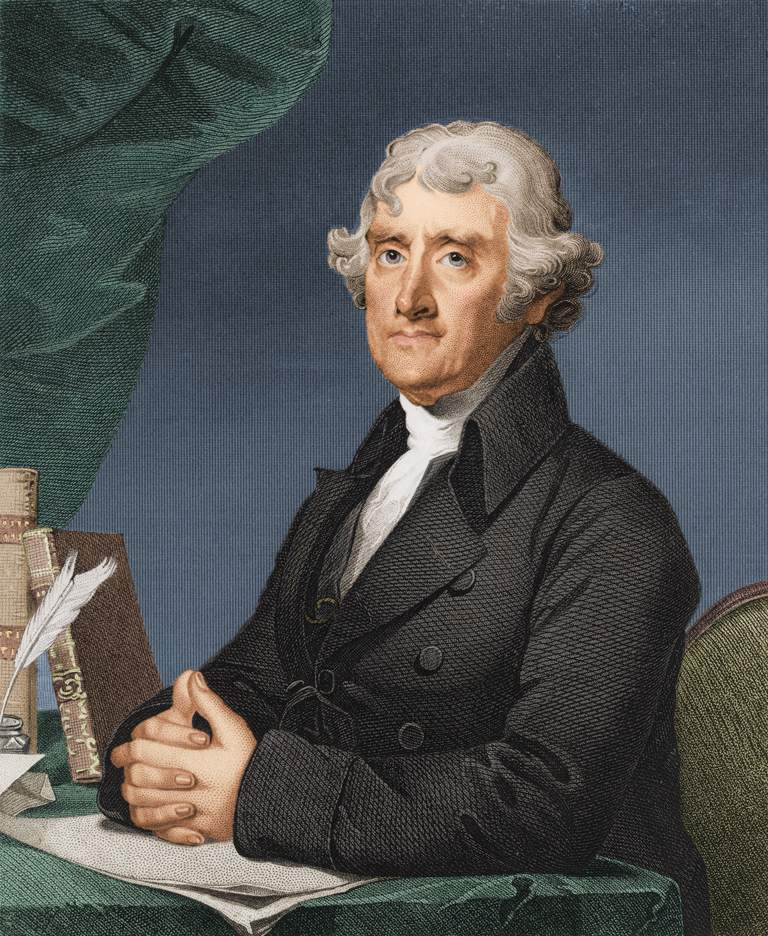

In one regard, TLR is absolutely right that an educated citizenry is vital for a healthy and vigorous political life. As Thomas Jefferson affirmed, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”[xi]

Signer of the Declaration Samuel Huntington agreed, declaring:

While the great body of freeholders are acquainted with the duties which they owe to their God, to themselves, and to men, they will remain free. But if ignorance and depravity should prevail, they will inevitably lead to slavery and ruin.[xii]

But if the problem TLR is trying to solve is citizen ignorance, the solution is citizen education, not reducing their rights and increasing an already over-bloated and unaccountable government bureaucracy. Informing citizens may not be the shortest or easiest route to their objectives, but it is undoubtedly the best for preserving political freedom.

The second argument for the Missouri Plan is that Merit Selection will stop corruption. Supporters allege that judicial corruption occurs because elections not only invite special interest money but they make judges too accountable to the people. As one group explained, “justices should be freed from wondering if their rulings will affect their job security.”[xiii] Proponents believe that if both money and the people are removed from the process, there will be less corruption.

Of course, this argument ignores the fact that the appointing commissioners also have their own vested interests and personal opinions as to how things should go in the judiciary, and they will select candidates accordingly. And if the concern is that special interest groups are “buying off” judges through donations, giving more political power to an unelected body is not the solution. There is no direct accountability for that body, their biases are not transparent, and recourse is difficult if not impossible to achieve, which increases rather than reduces opportunities for political malfeasance.

At its base, the Missouri Plan violates three core constitutional principles originally set forth by the Framers of our documents.

Three Fundamental Constitutional Principles the Missouri Plan Violates

1. Accountability

The first question that should always be asked with any political decision is, “How does this measure affect our liberty? —does it increase or reduce the rights and power of the citizenry?” If any part of the government is made less accountable, that proposal will be destructive of constitutional integrity.

The first question that should always be asked with any political decision is, “How does this measure affect our liberty? —does it increase or reduce the rights and power of the citizenry?” If any part of the government is made less accountable, that proposal will be destructive of constitutional integrity.

Revolutionary patriot and signer of the Declaration Elbridge Gerry affirmed, “The origin of all power is in the people, and they have an incontestable right to check the creatures of their own creation.”[xiv] Whenever the people lose their ability to hold governmental bodies accountable for the execution of their public trust, it is a fundamental infringement on the rights of the people.

Defenders of the Missouri Plan claim their system does provide methods of recourse for the people, but even a cursory glance shows that the committee selection process is perhaps the least accountable system of all. The logic is so backward that one of the groups actively promoting this plan strangely argues that it is good “because concentrating power in one decision maker promotes greater accountability”[xv]

The lessons of history are clear and its voices of experience unanimous: whenever power becomes more concentrated, it generates increased autonomy, decreased accountability, and diminished freedom.

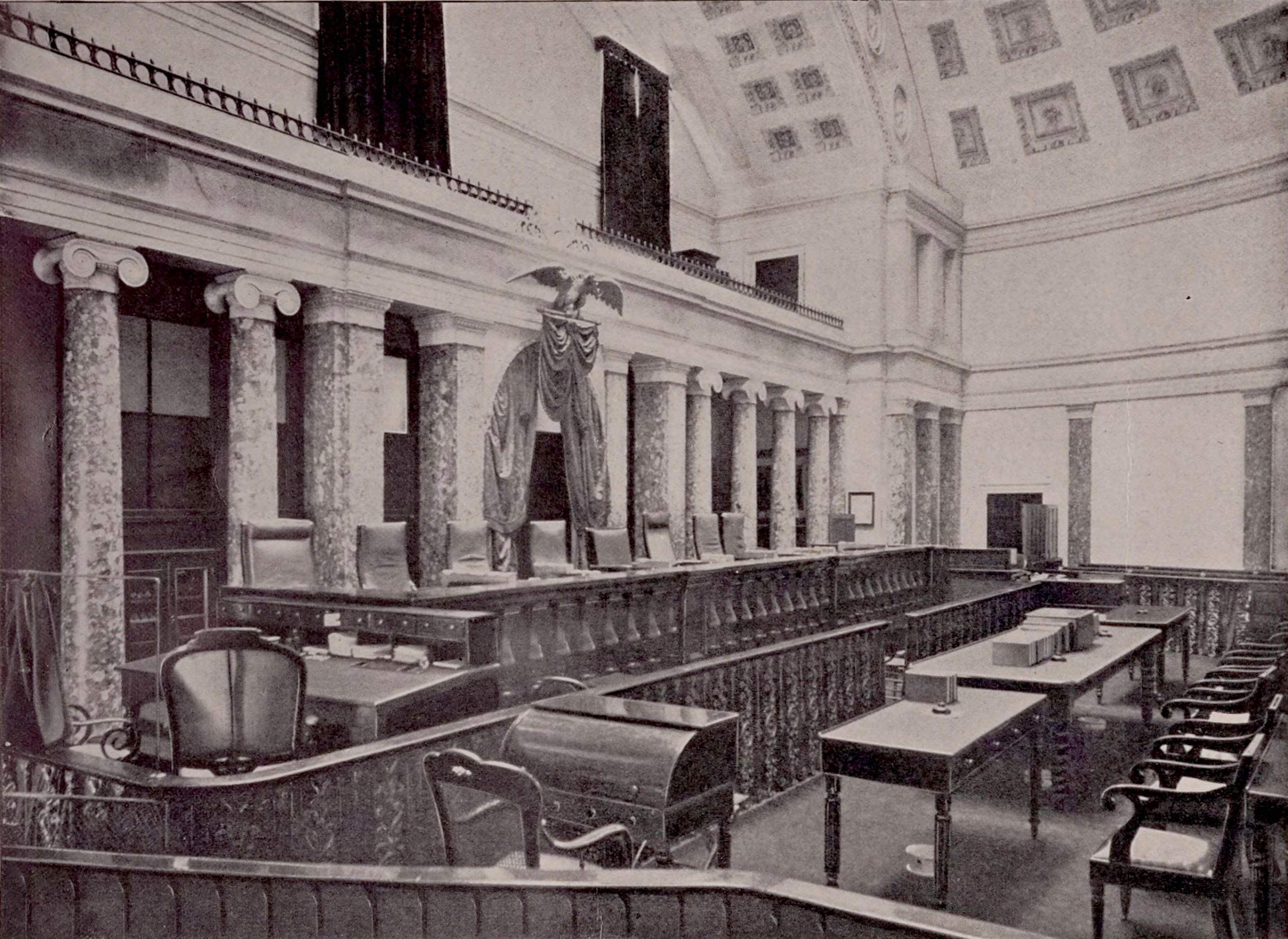

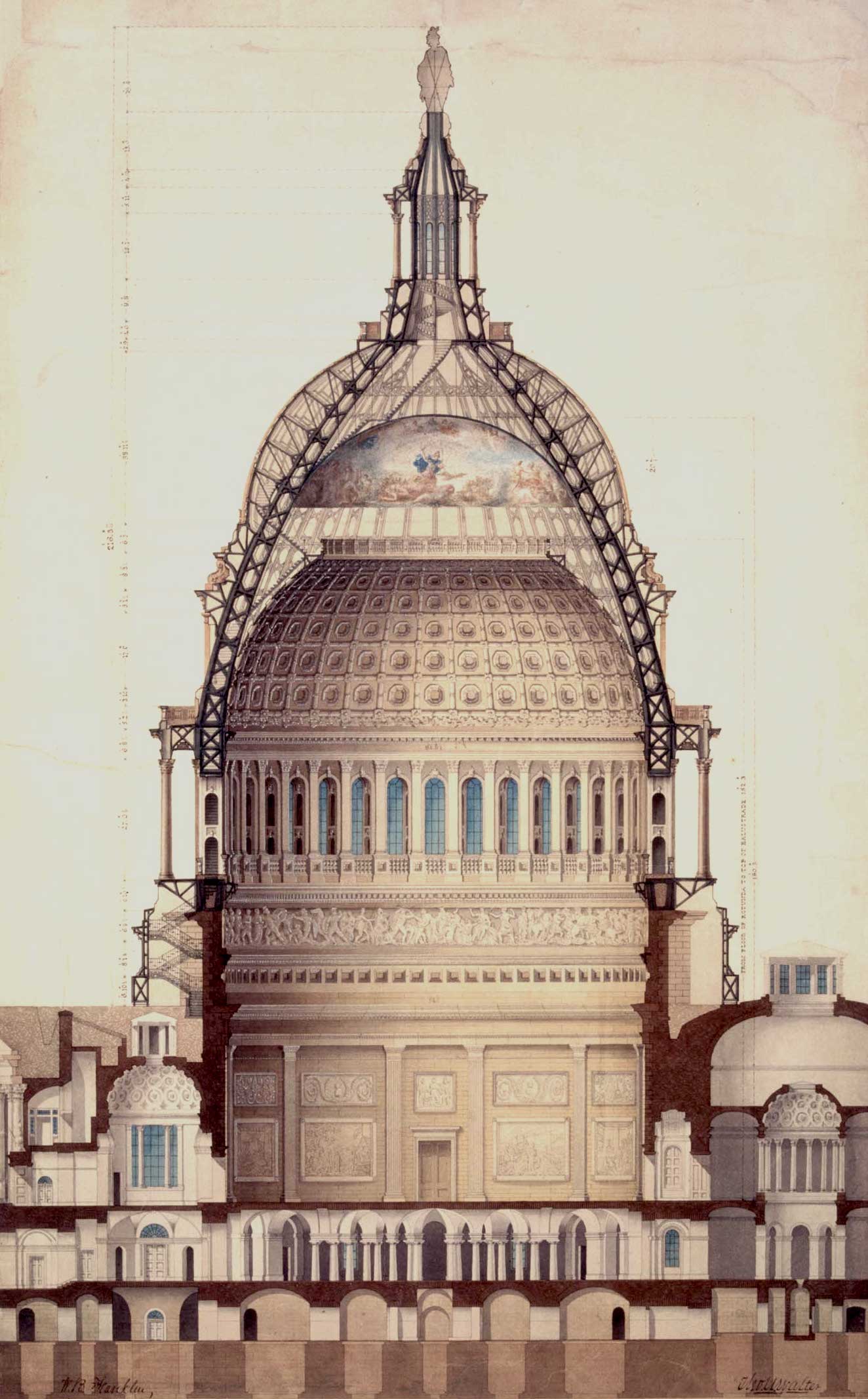

2. Preserving Constitutional Checks and Balances

Proponents of the Missouri Plan claim that citizen accountability over the judiciary is retained through judicial retention elections. (A retention election is one in which only the name of the sitting judge is on the ballot. A citizen simply votes yes or no for that judge, and if enough citizens vote no, then that judge is removed and the commission will select someone else to be judge.)

Not surprisingly, under this system the incumbent is reelected more than 99 percent of the time.[xvi] The reason for this is simple: in a contested election there is an opponent to point out and publicize what the incumbent has done wrong; without this, citizens rarely know that a wrong has occurred. (By the way, if citizens are too uneducated to make the initial selection of a good judge, why do proponents believe they will make a wiser choice in a retention election?)

Despite claims to the contrary, Merit Selection is not a neutral system that chooses the best judges. To the contrary, it can be even more partisan and polarizing than popular elections. As an example, in Missouri from 1995 to 2008, Democrats received just over half of the general election vote, but of judges selected by the Merit System who made political contributions, 87 percent of them donated to the Democrat party.[xvii] Clearly, judges chosen by Merit Selection accurately reflects the beliefs of those who chose them, not the beliefs of the voters in the state they are to judge.

3. Maintaining Judicial Oversight

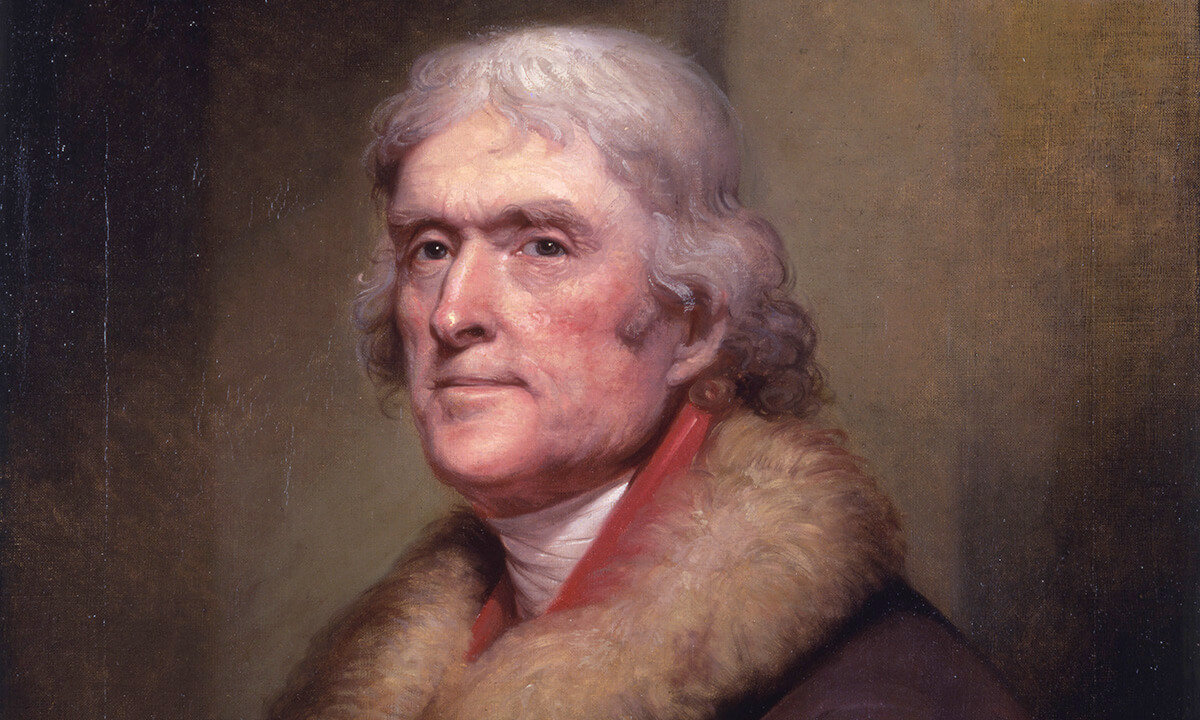

America’s concern with having judges not directly accountable to the people can be traced back to well before the American War for Independence. For example, in 1765, after years of living under British appointed judges, Founding Fathers like Samuel Adams began advocating for increased judicial accountability.[xviii] Consequently, when the Declaration of Independence was penned, four of its 27 grievances addressed judicial abuses, specifically lamenting that the King had “made judges dependent on his will alone for the tenure of their office and the amount and payment of their salaries.” This was Britain’s version of a “Merit Selection” system.

The Constitution sought to correct this by greatly limiting the power of the Judicial Branch. As Federalist 78 affirmed, the judiciary in America:

has no influence over either the sword or the purse—no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society—and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither force nor will.… [T]he judiciary is, beyond comparison, the weakest of the three departments of power.…[and] the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter.[xix] (emphasis added)

Jefferson explained why the Judiciary should never be independent from the people:

It should be remembered as an axiom of eternal truth in politics that whatever power in any government is independent is absolute also…. Independence can be trusted nowhere but with the people in mass.[xx]

It should be remembered as an axiom of eternal truth in politics that whatever power in any government is independent is absolute also…. Independence can be trusted nowhere but with the people in mass.[xx]

In fact, he specifically argued that if the people were to be left out of any branch, it definitely should not be the judiciary:

We think, in America, that it is necessary to introduce the people into every department of government….Were I called upon to decide whether the people had best be omitted in the legislative or judiciary department, I would say it is better to leave them out of the legislative. The execution of the laws is more important than the making them.[xxi]

Because the impact from an unaccountable judiciary can be so substantial, it was intentionally designed to be what the Federalist Papers had called “the weakest branch.” At the federal level, judges were to be kept in check by the threat of impeachment, and unlike today, that was not an empty threat during the Founding Era. A number of judges were impeached and removed due to improper judicial behavior, including offenses such as rudeness to witnesses, profanity in the courtroom, judicial high-handedness, and judicial activism.[xxii]

Joseph Hopper Nicholas (who served in the federal Congress under Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson) led several of the judicial removal efforts. When some objected that the judiciary should be more independent, he warned:

Give them [judges] the powers and the independence now contended for and.…your government becomes a despotism and they become your rulers. They are to decide upon the lives, the liberties, and the property of your citizens; they have an absolute veto upon your laws by declaring them null and void at pleasure.…If all this be true—if this doctrine be established in the extent which is now contended for—the Constitution is not worth the time we are now spending on it. It is—as it has been called by its enemies—mere parchment, for these judges, thus rendered omnipotent, may overleap the Constitution and trample on your laws.[xxiii]

Massachusetts understood this, and its state constitution made the point that all three branches—including the judiciary—were to be accountable to the people. (Ratified in 1780, the Massachusetts constitution is still in use today, making it the only active constitution in the world older than the US Constitution.) Written by notables such as John Adams, John Hancock, Sam Adams, and others, it declared:

All power residing originally in the people and being derived from them, the several magistrates and officers of government vested with authority—whether Legislative, Executive, or Judicial—are their substitutes and agents and are at all times accountable to them. [xxiv] (emphasis added)

Today an “independent judiciary” (meaning one unaccountable to the people or any other branch) has become the standard advanced by anti-constitutional Progressive groups such as Open Society (Soros funded), the Brennan Center for Justice, and the Equal Justice Initiative. Groups like these join TLR in their claim that the American people can’t be trusted to choose the right judge through regular elections and therefore a Merit Selection system such as the Missouri Plan is needed. (These groups fully understand that it is easier for them to influence or take over a small appointing commission than the full electorate of a state.)

Conclusion

In summary, the primary arguments for “Merit Selection” are: (1) the people lack the capacity to “appoint for themselves judges and officers” (Deuteronomy 16:18), and (2) elections, which make judges accountable, cause judges to become too political. The Founding Fathers believed the opposite on both points.

Concerning the first, Thomas Jefferson pointed out that if voters are ill-informed, the remedy certainly is not to reduce their involvement with the judiciary:

When the Legislative or Executive functionaries act unconstitutionally, they are responsible to the people in their elective capacity. The exemption of the judges from that is quite dangerous enough. I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them [the people] not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education. This is the true corrective of abuses of constitutional power.[xxv]

Concerning the second point (that judges should not be directly accountability to the people), signer of the Constitution John Dickinson queried “what innumerable acts of injustice may be committed—and how fatally may the principles of liberty be sapped—by a succession of judges utterly independent of the people?”[xxvi] Abraham Lincoln likewise affirmed that if judges are given the final word without accountability to the people, then “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having…resigned their government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”[xxvii]

Concerning the second point (that judges should not be directly accountability to the people), signer of the Constitution John Dickinson queried “what innumerable acts of injustice may be committed—and how fatally may the principles of liberty be sapped—by a succession of judges utterly independent of the people?”[xxvi] Abraham Lincoln likewise affirmed that if judges are given the final word without accountability to the people, then “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having…resigned their government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”[xxvii]

If America is to remain a strong constitutional republic, we must protect the safeguards established by our forefathers to disperse power and authority. The safest repository was and always will be the citizens—and if the citizens lack proper knowledge, the correct solution is citizen education, not a return to the same authoritarian practices the British once employed against our colonial ancestors.

Thomas Jefferson reminded us of the fundamental principle of American government that should guide our considerations in the question of whether a system such as the Missouri Plan is worthy:

[T]he will of the majority—the natural law of every society—is the only sure guardian of the rights of man. Perhaps even this may sometimes err, but its errors are honest, solitary and short-lived. Let us then, my dear friends, forever bow down to the general reason of the society. We are safe with that, even in its deviations, for it soon returns again to the right way.[xxviii]

The American experiment rests upon the basic premise that we would rather suffer from the ignorant errors of the people than the deliberate machinations of a political elite. To voluntarily surrender the rights of the people for fear they might vote for the wrong party is to betray both today’s citizens as well as the great historical sacrifices made in order for Americans to make their own political choices.

The creation of a body of unelected bureaucrats deciding who will be the people’s judges weakens liberty, politicizes courts, and reduces accountability. In Texas (as well as the rest of America), the Missouri Plan/Merit Selection should be rejected. ▀

Endnotes

[1] To the contrary, 21 states use the direct election of judges (both partisan and non-partisan), far more states than use any of the other five systems.

[i] Anisha Singh, “State or Federal Court,” Center for American Progress (August 8, 2016), here.

[ii] Douglas Keith, Judicial Nominating Commissions (New York: Brennen Center for Justice, 2019), 1, here.

[iii] “Courts and Judges,” Texans for Lawsuit Reform (accessed December 9, 2019), here.

[iv] Larry Berkson, “Judicial Selection in the United States: A Special Report,” American Judicial Society (April 2010), here.

[v] John Kowal, “Judicial Selection for the 21st Century,” The Brennan Center for Justice (June 6, 2016), here.

[vi] “Nonpartisan Election of Judges,” Ballotpedia (accessed December 17, 2019), here

[vii] Laura Zaccari, “Judicial Elections: Recent Developments, Historical Perspective, and Continued Viability,” Richmond Journal of Law and the Public Interest (Summer 2004), 139, here.

[viii] “Nonpartisan Election of Judges,” Ballotpedia (accessed December 17, 2019), here

[ix] Laura Zaccari, “Judicial Elections: Recent Developments, Historical Perspective, and Continued Viability,” Richmond Journal of Law and the Public Interest (Summer 2004), 143, here.

[x] “Courts and Judges,” Texans for Lawsuit Reform (accessed December 9, 2019), here.

[xi] Thomas Jefferson, “To Charles Yancey, January 6, 1816,” Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Bergh, editor (Washington, DC: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Assoc., 1904), 14.384.

[xii] Jonathan Elliot, editor. Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Washington, DC: Printed for the Editor, 1836), 2.200, see Samuel Huntington, January 9, 1788.

[xiii] Alicia Bannon, Choosing State Judges: A Plan for Reform (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, 2018), 1, here.

[xiv] Elbridge Gerry, “Observations On the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State Conventions, By a Columbian Patriot,” Pamphlets on the Constitution of the United States (Brooklyn: 1888), 6, here.

[xv] Alicia Bannon, Choosing State Judges: A Plan for Reform (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, 2018), 9, here.

[xvi] Deborah O’Malley, “Defense of the Elected Judiciary,” The Heritage Foundation (September 9, 2010), here.

[xvii] Brian Fitzpatrick, “Politics of Merit Selection,” Missouri Law Review Volume 74 Issue 3 (Summer 2009), 698, here.

[xviii] See, Samuel Adams, “Instructions of the Town of Boston to its Representatives in the General Court. September 1765,” The Writings of Samuel Adams (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 1.9; Samuel Adams, “The House of Representatives of Massachusetts to Dennys De Berdt. January 12, 1768,” The Writings of Samuel Adams (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 144; Samuel Adams, “The House of Representatives of Massachusetts to the Marquis of Rockingham. January 22, 1768,” The Writings of Samuel Adams (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 172; “Samuel Adams to Joseph Warren, Dec. 9, 1772,” The Warren-Adams Correspondence (Boston: The Massachusetts Historical Society, 1915), 1.14-15.

[xix] James Madison, John Jay & Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist (Philadelphia: Benjamin Warner, 1818), pp. 419-420.

[xx] Thomas Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, pp. 213-214, to Judge Spencer Roane on September 6, 1819.

[xxi] Thomas Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D.C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. VII, pp. 422-423, to M. L’Abbe Arnoud on July 19, 1789.

[xxii] Debates and Proceedings, Fifth Congress, First Session, July 8, 1797, 499-502; Debates and Proceedings, Seventh Congress, Second Session, March 3, 1803, 645 (Congress voted not to print the actual articles of impeachment against Pickering; See Debates and Proceedings, Eight Congress, First Session, March 24, 1804, 298); Register of the Debates in Congress, Twenty0First Congress, First Session, April 26, 1830, 383, and May 4, 1830, 411-413.

[xxiii] The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States (Washington: Gales & Seaton, 1851), Seventh Congress, 1st Session, pp. 823-824, February 27, 1802.

[xxiv] A Constitution or Frame of Government Agreed Upon by the Delegates of the People of the State of Massachusetts-Bay (Boston: Benjamin Edes & Sons, 1780), p. 9, Massachusetts, 1780, Part I, Article V.

[xxv] The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Andrew A. Lipscomb, editor (Washington, DC: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, p. 278, to William Charles Jarvis, September 28, 1820.

[xxvi] John Dickinson, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies (New York: The Outlook Company, 1903), p. 92, Letter IX.

[xxvii] The Works of Abraham Lincoln, John H. Clifford, editor (New York: The University Society Inc., 1908), Vol. V, pp. 142-143, “First Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1861.

[xxviii] Thomas Jefferson, “II. The Response, 12 February 1790,” Founders Online (accessed December 11, 2019), here.

On April 18th….Dr. Joseph Warren hastily dispatched Paul Revere on the ride that has made his name immortal. About midnight, Revere galloped up to the Rev. Mr. Clark’s house….By daybreak, one hundred and fifty men had mustered for the defense. John Hancock, with gun and sword, prepared to go out and fight with the minute-men, but [Samuel] Adams checked him….Hancock…went with him back through the rear of the house and garden to a thickly wooded hill where they could watch the progress of events. Dorothy Quincy and Aunt Lydia remained in the house, as no danger was apprehended there, and so by chance were eye witnesses of the first battle of the Revolution. Dorothy watched the fray from her bedroom window and in her narration of it notes: “Two men are being brought into the house. One, whose head has been grazed by a ball, insisted that he was dead, but the other, who was shot through the arm, behaved better.”

My Dear Dear Dolly….I shall make out as well as I can, but I assure you, my Dear Soul, I long to have you here….When I part from you again it must be a very extraordinary occasion….I was exceeding glad to hear from you & hope soon to receive another letter.

The education of our children is never out of my mind. Train them to virtue. Habituate them to industry [hard work], activity, and spirit [endurance]. Make them consider every vice as shameful and unmanly. Fire them with ambition to be useful. Make them disdain to be destitute of any useful or ornamental knowledge or accomplishment. Fix their ambition upon great and solid objects, and their contempt upon little, frivolous, and useless ones. (

The education of our children is never out of my mind. Train them to virtue. Habituate them to industry [hard work], activity, and spirit [endurance]. Make them consider every vice as shameful and unmanly. Fire them with ambition to be useful. Make them disdain to be destitute of any useful or ornamental knowledge or accomplishment. Fix their ambition upon great and solid objects, and their contempt upon little, frivolous, and useless ones. ( he would often spend extended periods away from his family. Wanting to encourage and advise his children during these times, especially on growing strong spiritually, he wrote a series of letters giving his son advice on how to read and study the Bible. In one of these letters, he

he would often spend extended periods away from his family. Wanting to encourage and advise his children during these times, especially on growing strong spiritually, he wrote a series of letters giving his son advice on how to read and study the Bible. In one of these letters, he

This is a part of our Alumni Series of articles written by past participants of the WallBuilders/Mercury One Leadership Training Program (now called “AJE Summer Institute”). Click

This is a part of our Alumni Series of articles written by past participants of the WallBuilders/Mercury One Leadership Training Program (now called “AJE Summer Institute”). Click  We also visited a multitude of Biblical sites ranging from the Garden of Gethsemane, to the Via Dolorosa, to Caesarea Philippi, to the Dead Sea and the Sea of Galilee. We explored the Jewish and Muslim quarters, shopped at the markets of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and walked in the ancient underground irrigation tunnels in the City of David. Each place we visited provided a greater understanding of the historical context of the biblical stories told in the Bible.

We also visited a multitude of Biblical sites ranging from the Garden of Gethsemane, to the Via Dolorosa, to Caesarea Philippi, to the Dead Sea and the Sea of Galilee. We explored the Jewish and Muslim quarters, shopped at the markets of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and walked in the ancient underground irrigation tunnels in the City of David. Each place we visited provided a greater understanding of the historical context of the biblical stories told in the Bible.

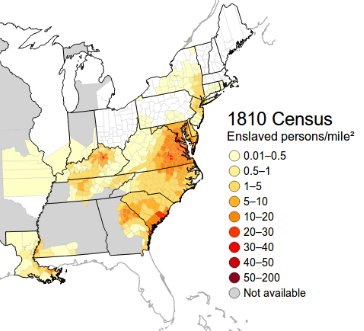

The 1810 census documents that the total population of those states—Massachusetts (Maine included), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey—stood at 3,486,675.

The 1810 census documents that the total population of those states—Massachusetts (Maine included), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey—stood at 3,486,675.

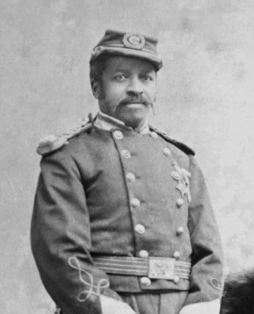

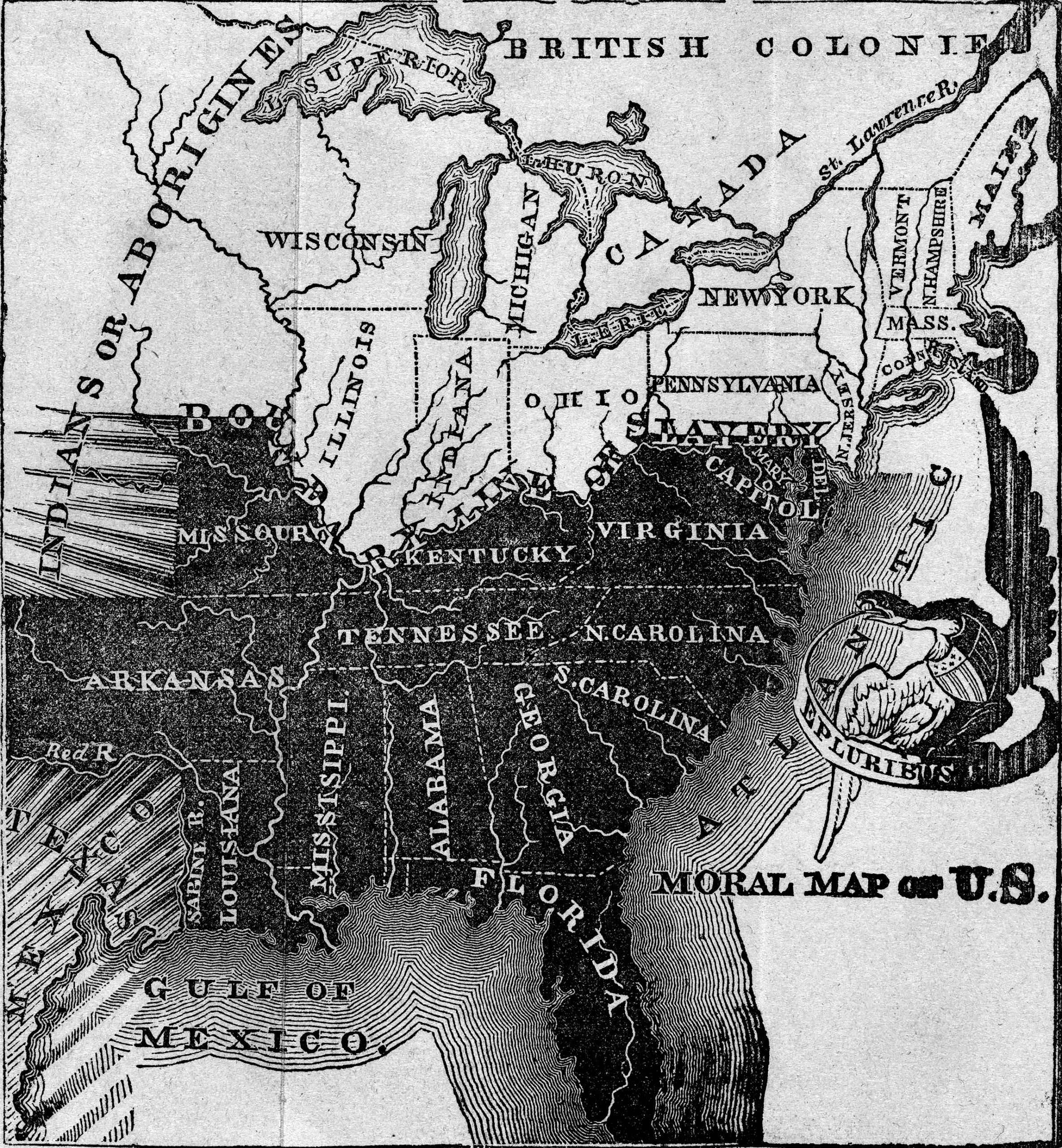

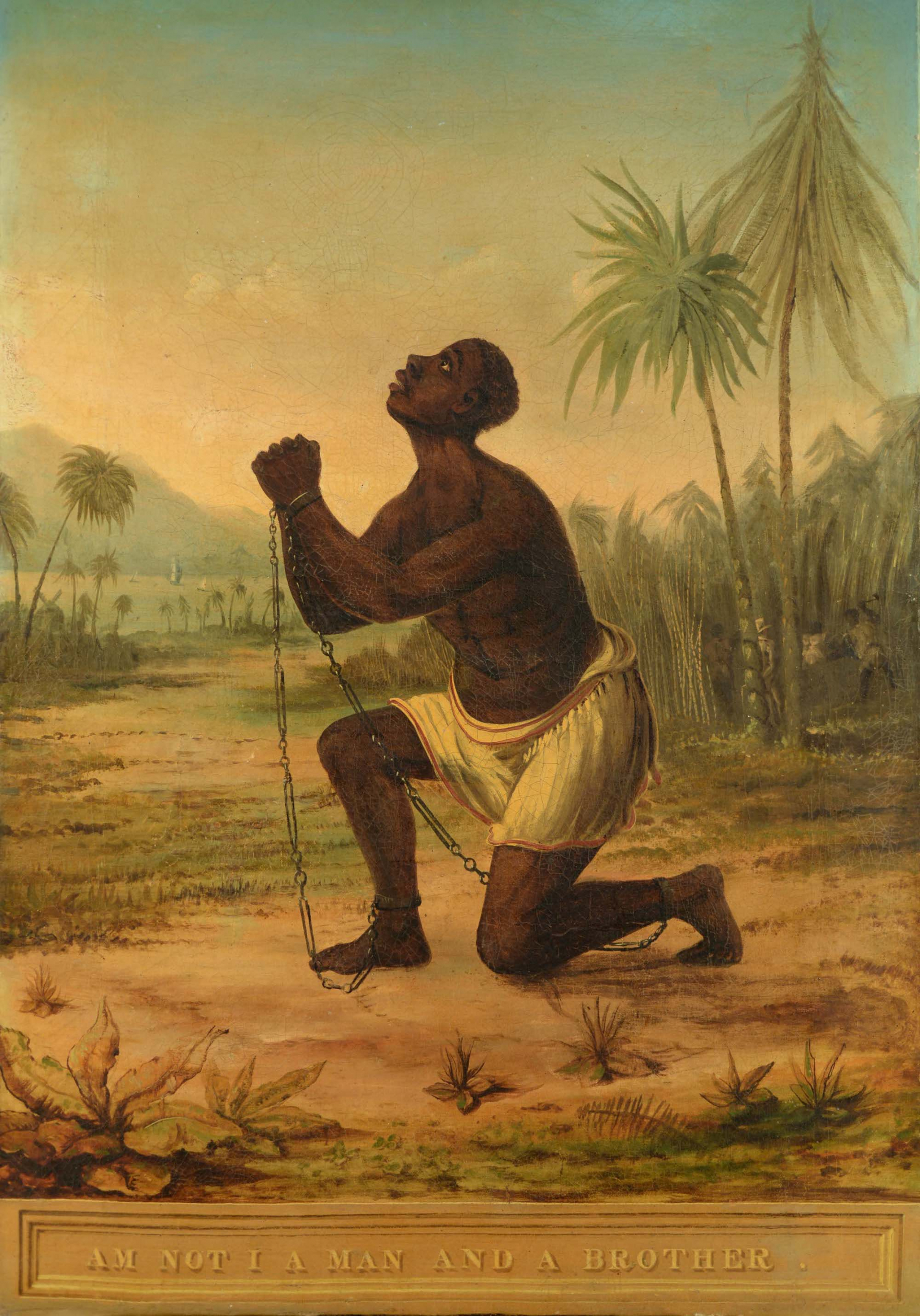

What is more, slavery both globally and in America was never simply white on black. Just as every people group has owned slaves, every people group has correspondingly been enslaved. Prior to the 1700s there were more white slaves globally than there were black slaves.

What is more, slavery both globally and in America was never simply white on black. Just as every people group has owned slaves, every people group has correspondingly been enslaved. Prior to the 1700s there were more white slaves globally than there were black slaves.

Throughout both American and world history, the Church has arisen and become a much-needed leader in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic provides us another such opportunity to be a shining light to people and communities. Gratefully, we have seen many churches across the nation rolling up their sleeves and taking the lead in extending God’s love to others and truly helping those in need during this difficult time.

Throughout both American and world history, the Church has arisen and become a much-needed leader in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic provides us another such opportunity to be a shining light to people and communities. Gratefully, we have seen many churches across the nation rolling up their sleeves and taking the lead in extending God’s love to others and truly helping those in need during this difficult time. Assist working parents.

Assist working parents. Activate people to keep praying.

Activate people to keep praying.

A prominent group arguing for this shift is Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR), an organization that has achieved many good things in the past, including major substantive tort reform. On its website, TLR explains why Texans should no longer be allowed to choose their judges:

A prominent group arguing for this shift is Texans for Lawsuit Reform (TLR), an organization that has achieved many good things in the past, including major substantive tort reform. On its website, TLR explains why Texans should no longer be allowed to choose their judges: The first question that should always be asked with any political decision is, “How does this measure affect our liberty? —does it increase or reduce the rights and power of the citizenry?” If any part of the government is made less accountable, that proposal will be destructive of constitutional integrity.

The first question that should always be asked with any political decision is, “How does this measure affect our liberty? —does it increase or reduce the rights and power of the citizenry?” If any part of the government is made less accountable, that proposal will be destructive of constitutional integrity. It should be remembered as an axiom of eternal truth in politics that whatever power in any government is independent is absolute also…. Independence can be trusted nowhere but with the people in mass.

It should be remembered as an axiom of eternal truth in politics that whatever power in any government is independent is absolute also…. Independence can be trusted nowhere but with the people in mass. Concerning the second point (that judges should not be directly accountability to the people), signer of the Constitution John Dickinson queried “what innumerable acts of injustice may be committed—and how fatally may the principles of liberty be sapped—by a succession of judges utterly independent of the people?”

Concerning the second point (that judges should not be directly accountability to the people), signer of the Constitution John Dickinson queried “what innumerable acts of injustice may be committed—and how fatally may the principles of liberty be sapped—by a succession of judges utterly independent of the people?”