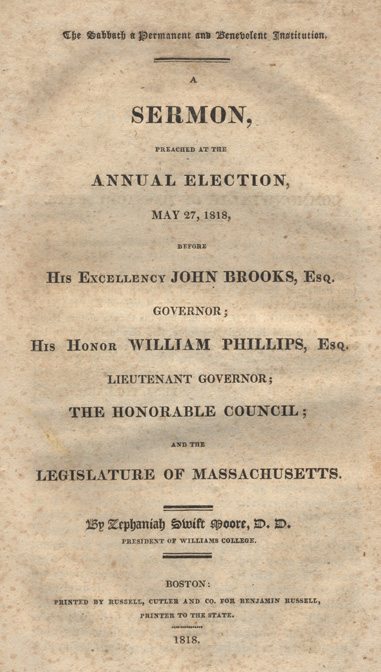

A

Sermon,

Preached

at Concord, Before His

Excellency the Governor,

The Honorable Council, The

Honorable Senate, and House of

Representatives, of the State

of New Hampshire,

June 6

1816.

Being

the Anniversary Election.

By

Pliny Dickinson,

Pastor

of the Church in Walpole.

State of New Hampshire, In the

House of Representatives, June 6th, 1816.

Voted, that Messrs. Appleton,

Healey and Brown, of Alstead, with such as the Senate may appoint, be a Committee to wait on the Rev. Mr. Dickinson and present him with the thanks of the Legislature for his ingenious, elegant and interesting discourse delivered this day before his Excellency the Governor, the Honorable Council and both branches of the Legislature, and request a copy for the press. Sent up for concurrence. D.L. Morril, Speaker.

II

Chron. XXIV. 2.

And

Joash did that which was right in the sight of the Lord all the days of Jehoida

the priest.

This Joash was the son of Ahaziah , king of Judah, who was slain by Jehu. After his death, the mother Atheliah, usurped the throne; and to perpetuate her possession of it, she destroyed all the seed royal of the house of Judah, except Joash; who, being then an infant, was secretly conveyed away by his aunt, the wife of Jehoida the priest, and was hidden in the house of God, and there preserved under the care of the priest, six years. It now being difficult to conceal him longer, Jehoida determined to place him on the throne; and he concerted his measures with such prudence and caution, that he effected his design without opposition: The usurper was at once deserted and given up to justice; and the young king was universally acknowledged, and the revolution diffused a general joy. Joash, at this time, was about seven years old: The times were exceedingly difficult; there had within a few years, been frequent changes in the government, and such as were not for the better: some partook of political oppression, and some tended to the extermination of true religion. Idolatry had been established in its grossest forms; the house of God had been broken up, and the sacred utensils had been carried away, and bestowed on the temple of Baal; so that the young king had much to do, and a difficult part to perform in a critical time:But it is remarked much to his honor, that he did that which was right in the sight of the Lord, all the days wherein Jehoida the priest instructed him; he chose him for his counselor, and acted by his advice. Educated in the temple of God, and under the care of this aged and godly priest, he seems to have entertained just sentiments of the divine character, and of the nature and importance of religion; especially as connected with a mild administration of government, and the prosperity of a nation. When he was raised to the throne, far from being intoxicated with his elevation, or inflated with pride, with a modesty becoming his youth, he sought the counsel of the wise; listened to the speech of the trusty, and leaned to the understanding of the aged. He did not, like Rehoboam, choose the young for his counselors; he prudently retained near his person the man whose wisdom and fidelity had been proved in his personal preservation and political promotion. He early discovered a zeal for the pure worship of God, while witnessing the deplorable declension of it. He had seen the ruinous state to which the house of God had been reduced by his idolatrous predecessors, and he was desirous to repair it. He called together the priests and Levites, and gave them orders to make that collection of money from the people which the law of Moses required, and to apply it when collected to this sacred purpose. When he saw them apparently slack in executing his orders. He expostulated even with Jehoida, and endeavored to animate him in the work. The zeal for religion which glowed in the young king soon spread through all ranks, civil and ecclesiastical. Both priests and princes, and all the people united and vied with each other in the great design. A collection was soon made more than sufficient to repair the house. With the surplus they restored its utensils and provided for its daily services. It is said, they set the house of God in its state and strengthened it; and of the rest of the money were made vessels for the house of the Lord, to minister and to offer withal, and spoons and vessels of gold and silver; and they offered burnt offerings in the house of the Lord continually all the days of Jehoida: And this undoubtedly was for a considerable length of time; for Jehoida lived till he was an hundred and thirty years old; and Joash continued on the throne forty years.

From a man, and especially from a ruler, who had so early discovered a zeal for true religion; had done so much to promote it, and had all along paid so much regard to the advice of the wise and good, we should have expected a constancy in a religious course, a perseverance in it to the end of life. If, when he was but a youth, he used his influence and authority so wisely, what might not be hoped from him, when arrived to maturity. But alas! we now find him quite another man. Though the worship of the true God was maintained in the nation, yet there were many, even among the leading men, who were friends to idolatry and infidelity: These, as soon as Jehoida was dead, and his restraining influence had ceased, came to the king, and by their insinuating address gained such an ascendancy over him, that he entirely renounced the good principles which he had received in his youth; and at the suggestion of his new counselors, established the worship of idols: And the people soon left the house of the Lord God of their fathers, and served groves and idols, till the divine displeasure kindled into wrath and consumed them.

In this time of alarming degeneracy and threatening calamity, there were some faithful prophets who testified against the apostasy of the people and labored to bring them back to the Lord; but, were unsuccessful: Among others, Zechariah, a son of the late priest, publicly expostulated, warned and entreated: Why transgress ye the commandments of the Lord that ye cannot prosper? because ye have forsaken him, he hath forsaken you: And they conspired against him, at the commandment of the king, and stoned him to death in the court of the Lord’s house. Thus Joash the king, the historian subjoins, remembered not the kindness, which Jehoida had done him, but slew his son, who, when he was dying, foretold that the Lord would look upon it and require it; which was fulfilled in a most memorable, melancholy manner.

This in substance is the history of Joash; and it may lead us to some profitable reflections.

1. We are reminded of the beneficial effects of a religious education. Although, it does not always prove as successful as might be hoped, yet there is always some benefit resulting from it; if not to those who are the immediate subjects of it, yet to others around them; and it is usually beneficial to the subjects. It operates, at least, as a restraint from vice and an aid to virtue, if it does not permanently improve the heart.

2. We see, in connection with the case before us, the fatal effects of listening to the advice of the wicked. Good beginnings are often defeated by corrupt counsel. Few youth ever enjoyed greater advantages, or seemed to make a better use of them, for a time, than king Joash. But as soon as his late instructor was laid in the grave, all his promising beginnings were blasted at once by the advice of wicked men.

3. Another thing observable, in view of the character before us, is the happy influence of religion in a ruler. As our observations upon this head will be predicated upon the character of Joash, we may here premise, that our deductions or references will respect him as he appeared in the days of Jehoida; not as he in heart may have been: We shall not stop to enquire, whether he acted solely under the influence of this pious priest; or whether his own feelings then cordially acquiesced; or in what sense, or to what degree, he, destitute as he was of a permanent principle of holiness, is said to have done that which was right in the sight of the Lord: It is sufficient for our present purpose to consider the religious part of his reign, and recommend it to others in authority.

Great good was done and much evil prevented under this part of administration. The nation, from the grossest idolatry, was raised to the rank of revealed rational religion. The king’s zeal provoked many; he led the way to this general reformation; his subjects fell in and followed of course. A ruler, who possesses the confidence of the people, and administers under influence of religion, as every one ought to, becomes a minister of God to the people for good, and may do wonders; may not only preserve the civil privileges, and promote the temporal prosperity of his subjects, but also enhance their spiritual happiness. Not that he can renew or sanctify a sinful heart, which is God’s prerogative; but he may honor, advocate and support the institutions by which God usually effects these ends. He may enact laws for promoting the observance, and for preventing the profanation of the Sabbath; for the encouragement of virtue and for the suppression of vice; for the distribution of justice, and for staying oppression; and having made, he will urge a prompt obedience to them. The former is useless without the latter. What is there, terrific, or restraining in a law which shrinks at the touch of the transgressor, or approaches him with a sluggish pace? While judgment is turned away backward, and justice standeth afar off, the wicked walk on every side, the enemy rush in like a flood, and perilous times appear: Shall I not visit for these things, shall I not be avenged on such a people, saith the Lord? But let a magistrate, as he would avoid perjury, act agreeably to his oath, put on judgment as a robe, clothe himself with righteousness as he is clothed with authority; gird on his armor, and become a terror to evil doers: Let him mingle mildness and mercy with justice; but while slow to condemn, be ready to protect; let him confirm the maxim, that the certainty rather than the frequency of punishments prevents crimes. Ah, rather let the transgressor pity the magistrate, and not challenge him to extremities; or have compassion upon himself, regard his own interest, refrain from his violations, reform, and consign the law to oblivion.

Is it not a little surprising, that men should lay violent hands upon any, and especially upon the principal pillar of civil, social and religious order, and tear down the edifice upon their own heads? And yet nothing less than this is the tendency of every breach of the Sabbath. Strike off from your calendar, this sacred day, or profane it which is the same thing, and you drive away with it the appalling presence of God; the sense of man’s accountability; the solemnity of an oath; the thought of a judgment to come, and all the influence of morality and virtue; and where is your safety for your persons, or your property, to say nothing of your spiritual prospects?

In renewing our remarks upon the influence of religion in rulers, we may observe, that many will always form their opinion of a government from what they know of the characters of the men who administer it. They are better judges of the private characters of men, with whom they are conversant, than they are of the constitutionality, tendency or propriety of their political measures. When a government is administered by men of acknowledged wisdom and rectitude, it will have the confidence, attachment and support of good men. When it is administered by the irreligious and vile, it will be dreaded and despised.

A sound judgment and a general knowledge of the public interest are necessary qualifications in rulers; but these, useful as they are, will not ensure them the respect and confidence of an enlightened and virtuous people, unless they themselves are so. The greater their abilities and acquirements, if they are believed to be destitute of moral principle, the more they will be objects of fear and distrust. The servile and corrupt will seek and secure their favor, by co- operating with them in their nefarious designs; but good men, alarmed and discouraged at the degeneracy of the times, will, like Aristides the just, give way to the ambitious; submit to the Ostracism; retire into the shade, accounting, in such a state of things, a private station the most honorable post. It is expected of the ministers of the gospel, that they be fearers of God and haters of covetousness, patriotic and pious, not seekers of their own emolument and promotion, but of the welfare of their people. And why may not the same be reasonably expected of the ministers of state; and if essential to the former, why not to the latter? And alike endowed, and united in their exertions, how much may they strengthen each others hands; how much promote the public weal; purify the morals, correct the principles, perpetuate the peace and enhance the happiness of community?

The examples and exertions of men in places of public trust, are generally more influential and effectual, and more likely to be imitated, than those of other classes, who move in the lower walks of life. Their elevation renders them conspicuous, and attracts the public attention. Besides, there is a general disposition in people to pattern after their superiors; but unfortunately, they more easily learn to imitate their vices than their virtues. For this reason, men who are clothed with power, or raised by their wealth above their neighbors, ought to feel themselves in a degree responsible for the behavior of those around them.

While speaking upon the influence of example, we may observe, that good example acts with the greater effect, because it reproves without upbraiding; and teaches us to correct our faults, without giving us the mortification of knowing, that any but ourselves have observed them. We feel the force of counsel or authority, in proportion to the degree in which it is exemplified by the one from whom it proceeds. The best counsel from one who obeys not his own precepts, nor practices upon the principles of his own statute or creed, will generally be but little regarded.

“Would you, your public laws should sacred stand,

Lead first the way, and act what you command:

The crowd grow mild and tractable, to see

The author governed by his own decree:

The world turns round, as its great matter draws,

And princes’ lives bind stronger than their laws.”

4. The subject naturally leads us to consider more particularly the connection and mutual dependence of civil and religious institutions. They are the principal pillars of the same edifice; the protection, the temporal and spiritual happiness of man. Impairing this connection is exposing the whole superstructure; is putting asunder what God has joined together; joined and connected, we say, not blended. They are distinct establishments, but mutually dependant, and may be mutual assistants. The connection between them we can trace back to the civil administration of Moses and to the priesthood of Aaron. Though they were appointed to different offices, and in some respects officiated separately; yet in their mission to the children of Israel, they were sent forth together; to walk hand in hand; to speak alternately; to co- operate; to receive and enforce both the civil and sacred law. Under all the primitive dispensations, we find this connection recognized; particularly in the law that required the people to contribute a certain part of their annual income to the support of the services in the temple. Indeed, this connection is explicitly acknowledged in our own State constitution; particularly in the article, which, after specifying that morality and piety give the best and greatest security to government, empowers the legislature to authorize towns and societies to make provision, at their own expense, for the support of public Protestant teachers of religion.

And again: What less than a sense of this connection, is expressed by the oaths of initiation into office? Nay, what less is the intention of our present assembling, but to implore a blessing upon the several branches of our government; thus acknowledging the necessity of religion to a wise administration; and, of course, a readiness to reciprocate the influence it may receive; a readiness to observe and uphold those religious institutions which are the life of rational liberty; the foundation of a free government; and which, in their full, restraining, pacific influence, would be a complete substitute for it. The great use an design of civil government is to enforce the same duties; to restrain men within the same bounds; and to keep them from the same danger; and, in a measure to accomplish the same ends, to which the gospel and its ordinances are directed. The latter, therefore, are a mighty aid to the former; and might supersede the necessity of it; leaving nothing for the ruler to do, but simply to regulate the prudentials of society.

And even the present partial influence of religion, where it is acknowledged and maintained, greatly facilitates and strengthens civil government, and befriends and meliorates the conditions of man. But let it once decline; let its authenticity be doubted and its institutions neglected; imagine, if you can, the fatal effects that would follow! Look at those places, both ancient and modern, where the experiment has been tried; at Jerusalem, after Joash’s apostasy from the worship of the true God, and his establishing idolatry; witness the outpourings of the wrath of God upon him and his subjects. Consider the unparalleled prosperity of Israel, during the administration of King David and that of his son Solomon: and again, the melancholy contrast, the national calamities that followed, as soon as Jeroboam and Rehoboam, in turn, took the reins of government, adopted new political measures, and especially, forsook, and drave their subjects from following the Lord. Oppression, embarrassments and war immediately ensued. But were these special judgments of heaven? Consider, then, the natural political effect.

Let a nation assume the purest republicanism, and work into their constitution the most refined principles of liberty, and then discard the doctrines and crush the institutions of religion, and their fine wrought threads will be wiped away, like a cobweb, and chains will supply the place.

Where there is no influence of religion, of course no inherent principle to govern men, they must be held under restraint and kept in order and awe by the fear of punishment. Republicanism, divested of the influence of religion, sinks into despotism. Not aware of all this, but charmed at the name of the one, and frightened at the sound of the other, nations, not a few, have felt the iron rod and the scorpion’s sting, before they were even apprehensive of danger. The Romans were not only amused, but really made vain, by the boast of their liberty, while they sweated and trembled under the despotism of emperors, the most odious monsters that ever infested the earth. We have heard a more modern people prattle about their rights, shouting liberty and equality, even while tyranny was loading them with chains, dragging them to the scaffold, and deluging their streets with blood. Men frequently start at the name, and at the same moment, greedily grasp the nature of the some thing: frequently in fleeing from the shadow, rush upon the substance.

The soil and atmosphere of Turkey are probably no more adapted to the spontaneous production of despotism, than those of America: Let the latter be divested of the influence of religion, equally with the former, and you probably would see a despotic sway, equally prevalent in both. To improve upon the various systems of government, much has been written upon the balance of power; particularly as to the point where it should be placed. Some have fixed it in an individual; some in a few; and some in a popular government. But after all, unless the scales of legislation and jurisprudence are held by hands sanctified, and steadied by wisdom that cometh from above, they will tremble and waver and give you fraudulent weight. Every government, of whatever form, without the influence of the one thing needful, degenerates into oppression and anarchy: Every ruler, of whatever name, whether king, emperor, governor, legislator, judge or magistrate, without the fear of God before his eyes, without a sense of his accountability, without feeling an interest and a responsibility for the persons and privileges of his fellow men, all which is among the first requisitions of religion, he will become an oppressor to all within his power. As the tyranny of a single despot is more tolerable than that of many, the oppression of a popular government, unchecked, uninfluenced by virtue, may be the greatest of all. The rage of one man, even that of a Tiberius, a Nero, or a Caligula, may be eluded by art or flight; or like a gust, may soon be expended, after having uprooted the trees that overtop the forest; but the frenzy, the fire of the people, once excited to action, by the friction of licentiousness, is universal, unavoidable and irresistible; it sweeps, deadens and demolishes every thing before it. It is a Briareus, with an hundred hands, each bearing a dagger: It is a Cerberus, a Hydra with ten thousand throats, all parched and thirsting for blood. The power of a single despot, like the scorching summer’s sun, dries up the grass, but the roots remain in the soil. But a popular despotism, if I may use the expression, like an Indian tornado, instantly strews the fruitful earth with promiscuous ruins, and turns the sky yellow with pestilence. To approach its atmosphere, is to perish in the attempt. Men inhale a vapor like the Sirocco, or like the effluvia of the Upas, and die in the open air for want of respiration: “It is a winged curse that envelopes the obscure as well as the distinguished, and is wafted into the lurking places of the fugitives.” Indeed the revolutions and consequences of a licentious popular government, are as dangerous and destructive as the irruptions of Vesuvius. They are an earthquake that loosens its foundations, lifts them to the skies, and buries, in an hour, the accumulated wealth and wisdom of ages. Those, who after the calamity, would reconstruct the edifice of the public liberty, will scarcely be able to collect enough of the scattered fragments; to rake out enough from the ruins, to make even a model of the former magnificence. “Mountains have split and filled the fertile vallies; rivers have changed their beds; populous towns have sunk, leaving only frightful chasms, out of which are creeping the remnant of living wretches, the monuments and victims of despair.”

This is no exaggerated description. A review of the history of nations, presents a cloud of witnesses to the melancholy facts. It shows us rulers and governments of every description, when unrestrained by virtue and led on by licentiousness, trampling on the necks, rioting on the spoils, and sporting with the miseries of their subjects. Subjects, falling before them with impious homage, or rescuing themselves from oppression, to run mad with the frenzy of anarchy, and to wanton in plunder and blood. Nations, of this character, as if in love with misery, and unsatisfied to see their sufferings so small, have reached out an eager hand to grasp at woe. Hence war has become a profession for man, and dexterously to wield the weapons of death an honorable achievement. Of course, conquest, like a roaring lion, has stalked around the desolated globe, seeking whom might devour. In his train, ambition has smoked with slaughter; avarice has ground the poor into dust; and pollution, like the messenger of death to the army of Sennacherib, has changed the host of men into putrid corpses: fiends have looked on and triumphed; angels have wondered and wept; and heaven, as if discouraged from efforts, has given up its work to waste & destruction.

God forbid that we should ever see this dismal group, but upon yonder heights of history; yet, let it not be doubted, that every step of degeneracy lessens the distance between us; and tends to bring the whole train to our doors; to lay waste our heritage, and to subject us to all the calamities incident to national apostasy. As it is easier preventing than remedying an evil, let the state, the nation, that thinketh it standeth, take heed lest it fall. Let her know, and attend to the things that belong to her peace and prosperity, before they are hidden from her eyes. Strong as our mountain appears, it may be moved. Those, as strong, and perhaps stronger, have been shaken to the centre. Witness the republics of ancient Greece, and modern Europe; particularly those of Italy, which sickened and died as it were in a day: while virtue was their basis, they stood; when infidelity touched and contaminated them, they fell. “The turnpike road of history is white with the tombstones of such republics.”

Hence we are cautiously to adopt the opinion, that our political probation is ended; that a republican constitution, when “once fairly engrossed in parchment, is prepared for perpetual practice, is a bridge over chaos that defies the discord of all its elements.”

Believe not, my brethren, that these remarks are made to excite false alarm; to weaken your confidence in the state or national constitution, or in those who administer agreeably to their true intent, and the sure standard of righteousness; God forbid, nothing can be further from my heart; but they are designed the more indelibly to impress the doctrine before us, that virtue and religion are essential to the establishment, administration and continuance of a good governmentI would therefore that these suggestions stand as beacons to point out the rocks and whirlpools to which you are exposed, and by which you may, as others have been, be dashed in pieces and swallowed up. I would that they correct, or qualify the prevalent impression, that true republicanism is commensurate with, and inseparable from the American soil; that the genius of genuine liberty has here erected a permanent asylum for oppressed humanity.

Do we open our arms and extend our embrace to every wayfaring foreigner? No matter in what land or language his birth was announced; no matter of what country or complexion incompatible with freedom; whether an Indian, or an African sun may have burnt upon him; whether the sands of Arabia or the snows of Switzerland may have beaten upon him; whether he be from Ceylon or England, from Bombay or France; from the barbarous and impoverished, or from the civilized and improved parts of the world; from heathen or Christian climes; whether he have been consecrated at the pagan altar, or at the baptismal font; “The first moment he touches the soil of America he breathes a new air; he rises in the ranks of rational beings; he stands redeemed, regenerated and disenthralled by the irresistible genius of universal emancipation.”

Do we hold out such alluring encouragements to emigration; let us not deceive, or be deceived; present is not perpetual possession. If we have privileges, let us take care to preserve them. And in respect to the present, particularly, remember, that righteousness exalteth a nation; that it is the life, the substance of a good government; detach it, and you leave nothing but the caput mortuum. They who imagine, says an eminent divine, that if religion and government, in the present state of things, were wholly separated, both would be more perfect; may as well go a little farther, and say, If in such a world as this, body and soul were separated, both would live much betterthe soul would labor better without a body, and the body would reason better without a soul. If a separation be made, the soul indeed will live; but it will pass away, and carry with it all that is rational; and the body will be left a mass of corruption, the food of worms. If from government, you banish religion, the latter will live; but it will take with it all that is amiable and excellent; and government will be like that putrid carcass. It may breed and nourish some odious vermin, but to those who have their senses, it will be an object of disgust and horror. Religion is connected with government by the principles of morality, as the soul is connected with the body by the principles of animation; and in both cases, a separation, though it will not extinguish the former, yet will be death to the latter.

As in point, I will here introduce the familiar remarks of another illustrious Sage, who, though dead, yet speaketh:

“Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness; these firmest props of men and citizens.The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and cherish them: A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity. Let it be simply asked, where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in the courts of justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.” Thus spake the man, whose maxims we delight to repeat, whose memory we delight to honor; thus declared he, the inseparable connection between religious influence and political prosperity.

5. We may next observe, in connection with the character and subject before us, the intoxicating influence of popular favor; and the not less fatal effects of the fear of man that bringeth a snare. Joash, while under the influence of Jehoida and the principles of piety, did that which was right in the sight of the Lord. But after good Jehoida was dead and gone, the subtle princes went and made obeisance to him, and flattered him to renounce Jehoida’s system of religion and government, and try experiments; strike out a new course. He complied; but woeful was the effect. As soon as he forsook the Lord, the Lord forsook him; suffered his servants to assassinate him; and sent an enemy and slew all the princes of the people. Saint John speaks of the rulers of his day, who did not confess Christ, because they were afraid of the Pharisees; loved the praise of men more than the praise of God. Aaron was overawed by the clamors of the Israelites, when he consented to make them an image to worship. Pilate condemned our Savior and sentenced him to be crucified, not because he found him guilty of any crime, but to please the people. Herod, the king, stretched forth his hands to vex certain of the church; killed James, and because he saw it pleased the Jews, proceeded further to take Peter also. Felix, Festus and Agrippa conducted in the same manner, and were actuated by the same motives in the arrest and trial of Paul. And even Peter, if I may mention him in this connection denied his Lord, through the fear of man that bringeth a snare. But the sequel is very different from the other cases: “The blush of dishonest shame had hardly time to tinge his cheek, ere the tears of contrition washed away the stain. The tempter dropt his prey as soon as he had grasped it; the moment of his fall coincided with the moment of his repentance.”

6. We further infer the importance of firmness and stability, particularly to a man in a public station. To these, among other directions, he will do well to take heed: Be not carried about with every wind of doctrine, and cunning craftiness of men, whereby they lie in wait to deceive; but be steadfast and unmovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord. The man in whom I see these exemplified; who, unmoved by the seducing charms of promised promotion on the one hand, or by threatening deposition on the other, conscientiously and self- collected, proceeds to the independent and faithful discharge of his duty; who, like the magnanimous Mansfield, chooses rather to merit and precede, than to run after popularity; who can say, with Paul, “None of these things move me:” such a character, whether in the principal chair of State, in the Senate, at the altar, the bar, or the bench, I venerate; I view him as a minister of God sent to the people for good. Dazzled with his angelic appearance, I almost forget that he is a mortal. Like the polar star, he remains fixed, while the inflated, self- promoted patriots, chase each other, like meteors across the galaxy; they appear, blaze, dash and dissolve.

In connection with the subject, I may, in the next place, respectfully remind His Excellency the Governor, the Hon. Council, the Senate and House of Representatives, of the high responsibility attached to their respective offices.

Gentlemen-

Your appearance here is a proof that you possess the confidence of your constituents, and warrants a belief that you will not disappoint their reasonable expectations. For them you are to legislate; not only so, but for posterity also; future generations, long after you are in the grave, will feel the effect of what you do: were we to predicate your legislative proceedings upon the past, or upon wisdom and prudence, we should predict favorably. Notwithstanding the conflict of political parties, and the several changes of administration incident to popular governments, we are happy to believe that a sacred regard has ever been had to ancient establishments, both civil and religious; and particularly a readiness uniformly shown, to recognize and cherish, rather than to deny and exterminate, their mutual connection and reciprocal influence. And we confidently hope that the same respect will continue to be conspicuous; to be a prominent feature in the government of New- Hampshire.

Any particulars wherein your predecessors may have erred, you will avoid; wherein they have done well, you will go and do likewise. It is presumed that a pacific, tranquilizing spirit will pervade all your measures. You have many motives to moderation and fidelity; but none that ought so deeply to impress you as thisthat you are accountable for all your conduct to the King of kings and Lord of lords; who standeth in the congregation of the mighty, and judgeth among the nations. Your public and private conduct now will have a permanent influence on your future state. You will consider, therefore, that though you are rulers over men, you are God’s servants; and his approbation is of more importance than all other interests. May you have his benediction here, and be thus addressed by him hereafter: “Well done, good and faithful servant; enter into the joy of your Lord.”

As to our late Chief- Magistrate, who for several years held a conspicuous office under the old Constitution, and that of Governor fourteen years under the present, eleven in succession; few have had stronger and more repeated expressions of public confidence; but, as he has done; has closed his political course, and is retiring to private life. we wish him a calm retreat; hoping that the evening of his days will be passed in as much pleasantness, as the meridian has in usefulness; that the gloomy thought of his leaving none in office whom he found there, the most of them having gone to the grave, and that he must soon draw after them, may be cheered by an assurance, that he has not forsaken the faith of his fathers, but has fought a good fight and kept the faith; and that there is laid up for him a crown of glory which fadeth not away.

Men and brethren, rulers and subjects!

Though ye be gods on earth, know that ye must die as men. You have an affecting proof of this, in the recent removal of the amiable and eminent Judge Ellis. While you lament his loss, embalm his memory upon your hearts.

Finally; one thought more, and I have done. My friends and fellow- mortals!

The impression that I shall see your faces, collectively, no more; that this solemn assembly will, identically, meet no more, till they meet at the bar of God, chills my heart, and checks the current in my veins. In taking leave of you, permit me to urge the importance of living in reference to you accountability, and to the consummation of all things. Look forward to your dying day; to the awful era, when time shall be no longer; when these visible heavens shall depart as a scroll; when the elements shall melt with fervent heat; when the earth, and the works that are therein, shall be burnt up; when the Judge shall descend and every eye shall see him; when the last trumpet shall sound, and the dead in Christ shall rise first; then they who are alive and remain, shall be caught up with them to meet the Lord in the air, and so shall they be forever with the Lord. Wherefore comfort one another with these words.