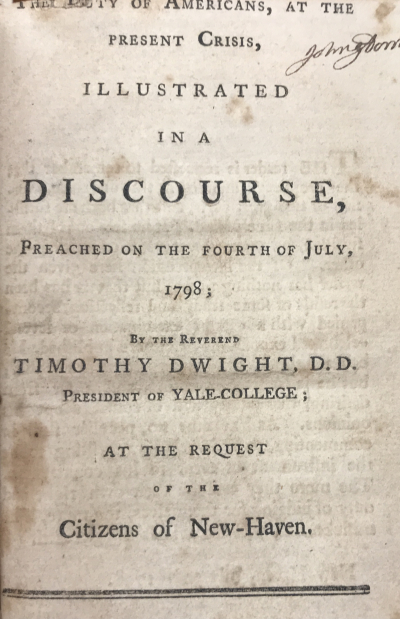

Timothy Dwight (1752-1817) graduated from Yale in 1769. He was principal of the New Haven grammar school (1769-1771) and a tutor at Yale (1771-1777). A lack of chaplains during the Revolutionary War led him to become a preacher and he served as a chaplain in a Connecticut brigade. Dwight served as preacher in neighboring churches in Northampton, MA (1778-1782) and in Fairfield, CT (1783). He also served as president of Yale College (1795-1817).

THE DUTY OF AMERICANS, AT THE

PRESENT CRISIS,

ILLUSTRATED IN A DISCOURSE,

PREACHED ON THE FOURTH OF JULY,

1798;

BY THE REVEREND

TIMOTHY DWIGHT, D. D.

PRESIDENT OF YALE-COLLEGE;

AT THE REQUEST

OF THE

Citizens of New-Haven.

NEW-HAVEN; PRINTED BY THOMAS AND SAMUEL GREEN, 1798.

REVELATION XVI.XV.

“Behold I come as a thief: Blessed is he

that watcheth, and keepeth his garments, lest he

walk naked, and they see his shame.”

THIS passage is inserted as a parenthesis in the account of the sixth vial. To feel its whole force it will be necessary to recur to that account, and to examine it with some attention. It is given in these words.

- 12. “And the sixth angel poured out his vial upon the great river Euphrates; and the water thereof was dried up, that the way of the king of the east might be prepared.”

- “And I saw three unclean spirits like frogs come out of the mouth of the dragon, and out of the mouth of the beast, and out of the mouth of the false prophet.

- “For they are the spirits of devils (Gr. Demons), working miracles, which go forth unto the kings of the earth, and of the whole world, to gather them to the battle of that great day of God Almighty.”

- “Behold I come as a thief: Blessed is he that watcheth, and keepeth his garments, lest he walk naked, and they see his shame.”

- “And he gathered them together into a place called in the Hebrew tongue Armageddon.”

TO this account is subjoined that of the seventh vial; at the effusion of which is accomplished a wonderful and most affecting convulsion of this guilty world, and the final ruin of the Antichristian empire. The circumstances of this amazing event are exhibited at large in the remainder of this, and in the three succeeding chapters.

INSTEAD of employing the time, allowed by the present occasion, in stating the several opinions of commentators concerning this remarkable prophecy, opinions which you can examine at your leisure, I shall, as briefly as may be, state to you that, which appears to me to be its true meaning. This is necessary to be done, to prepare you for the use of it, which is now intended to be made.

IN the 12th verse, under a natural allusion to the manner in which the ancient Babylon was destroyed, a description is given us of the measures, used by the Most High to prepare the way for the destruction of the spiritual Babylon. The river Euphrates surrounded the walls, and ran through the middle, of the ancient Babylon, and thus became the means of its wealth, strength and safety. When Cyrus and Cyaxares (The Darius of Daniel), the kings of Persia and Media, or, in the Jewish phraseology, of the east, took this celebrated city, they dried up, or emptied, the waters of the Euphrates, out of its proper channel, by turning them into a lake, or more probably a sunken region of the country, above the city. They then entered by the channel which passed through the city, made themselves masters of it, and overturned the empire. The emptying, or drying up, of the waters of the real Euphrates thus prepared the way of the real kings of the east for the destruction of the city and empire of the real Babylon. The drying up of the waters of the figurative Euphrates in the like manner prepares the way of the figurative kings of the east for the destruction of the city and empire of the figurative Babylon. The terms waters, Euphrates, kings, east, Babylon, are all figurative or symbolical; and are not to be understood as denoting real kings, or a real east, any more than a real Euphrates, or a real Babylon. The whole meaning of the prophet is, I apprehend, that God will, under this vial, so diminish the wealth, strength, and safety, of the spiritual or figurative Babylon, as effectually to prepare the way for its destroyers.

IN the remaining verses an event is predicted, of a totally different kind; which is also to take place in the same period. Three unclean spirits; like frogs, are exhibited as proceeding out of the mouth of the Dragon or Devil, of the Beast or Romish Government, and of the False Prophet, or, as I apprehend, of the regular Clergy of that Hierarchy. These spirits are represented as working miracles, as going forth to the kings, of the whole world, to gather them; and as actually gathering them together to the battle of that great day of God Almighty, described in the remainder of this chapter, and in the three succeeding ones. Of this vast enterprise the miserable end is strongly marked, in the name of the place, into which they are said to be gathered—Armageddon—the mountain of destruction and mourning.

THE writer of this book will himself explain to us what he intended by the word spirits in this passage. In his 1st Epistle, ch. iv. v. 1. he says,

Beloved, believe not every spirit; but try the spirits, whether they be of God; because many false prophets are gone out into the world. (See also v. 2, 3, 6.)

- E. Believe not every teacher, or doctrine, professing to come from God; but examine all carefully, that ye may know whether they come from God, or not; for many false prophets, or teachers passing themselves upon the Church for teachers of truth, but in reality teachers of false doctrines, are gone out into the world.

IN the same sense, if I am not deceived, is the word used in the passage under consideration. One great characteristic and calamity of this period is, therefore, that unclean teachers, or teachers of unclean doctrines, will spread through the world, to unite mankind against God. They are said to be three; i. e. several; a definite number being used here, as in many other passages of this book, for an indefinite one; to come out of the mouths of the three evil agents abovementioned; i. e. to originate in those countries, where they have principally co-operated against the kingdom of God; to be unclean; to resemble frogs; i. e. to be lothesome, clamorous, impudent, and pertinacious; to be the spirits of demons, i. e. to be impious, malicious, proud, deceitful, and cruel; to work miracles, or wonders; and to gather great multitudes of men to battle, i. e. to embark them in an open, professed enterprise, against God Almighty.

HAVING thus summarily explained my views of this prophecy, I shall now for the purpose of presenting it in a more distinct and comprehensive view draw together the several parts of it in a paraphrase.

IN the sixth great division of the period of providence, denoted by the vials filled with divine judgments and emptied on the world, the wealth, strength and safety of the Antichristian empire will be greatly lessened, and thus effectual preparation will be made for its final overthrow.

IN the meantime several teachers of false and immoral doctrines will arise in those countries, where the Powers of the Antichristian empire have especially distinguished themselves, by corrupting the truth, and persecuting the followers, of Christ; the character of which teachers and their doctrines will be impure, lothesome, impudent, pertinacious, proud, deceitful, impious, malicious, and cruel.

THESE teachers will, by their doctrines and labours, openly, professedly, and in an unusual manner, contend against God, and against his kingdom in this world, and will strive to unite mankind in this opposition.

NOR will they fail of astonishing success; for they will actually unite a large part of the human race, particularly in Christendom, in this impious undertaking.

BUT they will only unite them to their destruction; a destruction most awfully accomplished at the effusion of the seventh vial.

FROM this explanation it is manifest, that the prediction consists of two great and distinct parts; the preparation for the overthrow of the Antichristian empire; and the embarkation of men in a professed and unusual opposition to God, and to his kingdom, accomplished by means of false doctrines, and impious teachers.

BY the ablest Commentators the fifth vial is considered as having been poured out at the time of the Reformation. The first is supposed, and with almost absolute certainty, to have begun to operate not long after the year 800. If we calculate from that period to the year 1517, the year in which the Reformation began in Germany, the four first vials will be found to have occupied about four times 180 years. 180 years may therefore be estimated as the greatest, and 170 years as the least duration of a single vial. From the year 1517 to the year 1798 there are 281 years. If the fifth vial be supposed to have continued 180 years, its termination was in the year 1697; if 170, in 1687. Of course the sixth vial may be viewed as having been in operation more than 100 years.

YOU will now naturally ask, What events in the Providence of God, found in this period, verify the prediction?

TO this question I answer, generally, that the whole complexion of things appears to me to have, in a manner surprisingly exact, corresponded with the prediction. The following particulars will evince with what propriety this answer is returned.

WITHIN this period the Jesuits, who constituted the strongest branch, and the most formidable internal support, of the Romish hierarchy, have been suppressed.

WITHIN this period various other orders of the regular Romish Clergy have in some countries been suppressed, and in others greatly reduced. Their permanent possessions have been confiscated, and their wealth and power greatly lessened.

WITHIN this period the Antichristian secular powers have been in most instances exceedingly weakened. Poland as a body politic is nearly annihilated. Austria has deeply suffered. Venice and the popish part of Switzerland as bodies politic have vanished. The Sardinian monarchy is on the eve of dissolution. Spain, Naples, Tuscany, and Genoa, are sorely wounded; and Portugal totters to its fall. By the treaty, now on the tapis in Germany, the Romish Archbishoprics and Bishoprics, in that empire, are proposed to be secularized, and as distinct governments to be destroyed. As the strength of these powers was the foundation, on which the Hierarchy rested; so their destruction, or diminution, is a final preparation for its ruin.

IN France, Belgium, the Italian, and Cis-rhenane republics, a new form of government has been instituted, the effect of which, whether it shall prove permanent, or not, must be greatly and finally to diminish the strength of the Hierarchy.

IN France, and in Belgium, the whole power and influence of the Clergy of all descriptions have, in a sense, been destroyed; and their immense wealth has been diverted into new channels. In France, also, an open, violent, and inveterate war has been made upon the Hierarchy, and carried on with unexampled bitterness and cruelty. (In the mention of all these evils brought on the Romish Hierarchy, I beg he may be remembered that I am far from justifying the iniquitous conduct of their persecutors. I know not that any person holds it, and all other persecution, more in abhorrence. Neither have I a doubt of the integrity and piety of multitudes of the unhappy sufferers. In my view they claim, and I trust will receive, the commiseration, and, as occasion offers, the kind offices of all men possessed even of common humanity.)

WITHIN this period, also, the revenues of the Pope have been greatly curtailed; the territory of Avignon has been taken out of his hands; and his general weight and authority have exceedingly declined.

WITHIN the present year his person has been seized, his secular government overturned, a republic formed out of his dominions, and an apparent and at least temporary end put to his dominion.

TO all these mighty preparations for the ruin of the Antichristian empire may be added, as of the highest efficacy, that great change of character, of views, feelings, and habits, throughout many Antichristian countries, which assures us completely, that its former strength can never return.

THUS has the first part of this remarkable prophecy been accomplished. Not less remarkable has been the fulfilment of the second.

ABOUT the year 1728, Voltaire, so celebrated for his wit and brilliancy, and not less distinguished for his hatred of christianity and his abandonment of principle, formed a systematical design to destroy christianity, and to introduce in its stead a general diffusion of irreligion and atheism. For this purpose he associated with himself Frederic the II, king of Prussia, and Mess. D’Alembert and Diderot, the principal compilers of the Encyclopedie; all men of talents, atheists, and in the like manner abandoned. The principal parts of this system were, 1st. The compilation of the Encyclopedie (The celebrated French Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, in which articles of Theology were speciously and decently written; but, by references artfully made to other articles, all the truth of the former was entirely and insidiously overthrown to most readers, but the sophistry of the latter.); in which with great art and insidiousness the doctrines of Natural as well as Christian Theology were rendered absurd and ridiculous; and the mind of the reader was insensibly steeled against conviction and duty. 2. The overthrow of the religious orders in Catholic countries; a step essentially necessary to the destruction of the religion professed in those countries. 3. The establishment of a sect of philosophists to serve, it is presumed, as a conclave, a rallying point, for all their followers. 4. The appropriation to themselves, and their disciples, of the places and honours of members of the French Academy, the most respectable literary society in France, and always considered as containing none but men of prime learning and talents. In this way they designed to hold out themselves, and their friends, as the only persons of great literary and intellectual distinction in that country, and to dictate all literary opinions to the nation. (So far was this carried, that a Mr. Beauzet, a layman, but a sincere Christian, who was one of the forty members, once asked D’Alembert how they came to admit him among them? D’Alembert answered, without hesitation, “I am sensible, this must seem astonishing to you; but we wanted a skillful grammarian, and among our party, not one had acquired a reputation in this line. We know that you believe in God, but, being a good sort of man, we cast our eyes upon you, for want of a philosopher to supply your place.” Brit. Crit. Art. Barruel’s Memoirs of the History of Jacobinism. August 1797.) 5. The fabrication of Books of all kinds against christianity, especially such as excite doubt, and generate contempt and derision. Of these they issued, by themselves and their friends, who early became numerous, an immense number; so printed, as to be purchased for little or nothing, and so written, as to catch the feelings, and steal upon the approbation, of every class of men. 6. The formation of a secret Academy, of which Voltaire was the standing president, and in which books were formed, altered, forged, imputed as post-humous to deceased writers of reputation, and sent abroad with the weight of their names. These were printed and circulated, at the lowest price, through all classes of men, in an uninterrupted succession, and through every part of the kingdom.

NOR were the labours of this Academy confined to religion. They attacked also morality and government, unhinged gradually the minds of men, and destroyed their reverence for every thing heretofore esteemed sacred.

IN the mean time, the Masonic Societies, which had been originally instituted for convivial and friendly purposes only, were, especially in France and Germany, made the professed scenes of debate concerning religion, morality, and government, by these philosophists (The words Philosophism and Philosophists may in our opinion, be happily adopted from this work, to designate the doctrines of the Diestical sect; and thus to rescue, the honourable terms of Philosophy and Philosopher from the abuse, into which they have fallen. Philosphism is a love of Sephisms, and thus completely describes the sect of Voltaire: A Philosphists is a lover of Sophists. Brit. Crit. Ibid.) who had in great numbers become Masons. For such debate the legalized existence of Masonry, its profound secresy, its solemn and mystic rites and symbols, its mutual correspondence, and its extension through most civilized countries, furnished the greatest advantages. All here was free, safe, and calculated to encourage the boldest excursions of restless opinion and impatient ardour, and to make and fix the deepest impressions. Here, and in no other place, under such arbitrary governments, could every innovator in these important subjects utter every sentiment, however daring, and attack every doctrine and institution, however guarded by law or sanctity. In the secure and unrestrained debates of the lodge, every novel, licentious, and alarming opinion was resolutely advanced. Minds, already tinged with philosophism, were here speedily blackened with a deep and deadly die; and those, which came fresh and innocent to the scene of contamination, became early and irremediably corrupted. A stubborn incapacity of conviction, and a flinty insensibility to every moral and natural tie, grew of course out of this combination of causes; and men were surely prepared, before themselves were aware, for every plot and perpetration. In these hot beds were sown the seeds of that astonishing Revolution, and all its dreadful appendages, which now spreads dismay and horror throughout half the globe.

WHILE these measures were advancing the great design with a regular and rapid progress, Doctor Adam Weishaupt, professor of the Canon law in the University of Ingolstadt, a city of Bavaria (in Germany) formed, about the year 1777, the order of Illuminati. This order is professedly a higher order of Masons, originated by himself, and grafted on ancient Masonic Institutions. The secresy, solemnity, mysticism, and correspondence of Masonry, were in this new order preserved and enhanced; while the ardour of innovation, the impatience of civil and moral restraints, and the aims against government, morals, and religion, were elevated, expanded, and rendered more systematical, malignant, and daring.

IN the societies of Illuminati doctrines were taught, which strike at the root of all human happiness and virtue; and every such doctrine was either expressly or implicitly involved in their system.

THE being of God was denied and ridiculed.

GOVERNMENT was asserted to be a curse, and authority a mere usurpation.

CIVIL society was declared to be the only apostasy of man.

THE possession of property was pronounced to be robbery.

CHASTITY and natural affection were declared to be nothing more than groundless prejudices.

ADULTERY, assassination, poisoning, and other crimes of the like infernal nature, were taught as lawful, and even as virtuous actions.

TO crown such a system of falshood and horror all means were declared to be lawful, provided the end was good.

IN this last doctrine men are not only loosed from every bond, and from every duty; but from every inducement to perform any thing which is good, and, abstain from any thing which is evil; and are set upon each other, like a company of hellhounds to worry, rend, and destroy. Of the goodness of the end every man is to judge for himself; and most men, and all men who resemble the Illuminati, will pronounce every end to be good, which will gratify their inclinations. The great and good ends proposed by the Illuminati, as the ultimate objects of their union, are the overthrow of religion, government, and human society civil and domestic. These they pronounce to be so good, that murder, butchery, and war, however extended and dreadful, are declared by them to be completely justifiable, if necessary for these great purposes. With such an example in view, it will be in vain to hunt for ends, which can be evil.

CORRESPONDENT with this summary was the whole system. No villainy, no impiety, no cruelty, can be named, which was not vindicated; and no virtue, which was not covered with contempt.

THE means by which this society was enlarged, and its doctrines spread, were of every promising kind. With unremitted ardour and diligence the members insinuated themselves into every place of power and trust, and into every literary, political and friendly society; engrossed as much as possible the education of youth, especially of distinction; became licensers of the press, and directors of every literary journal; waylaid every foolish prince, every unprincipled civil officer, and every abandoned clergyman; entered boldly into the desk, and with unhallowed hands, and satanic lips, polluted the pages of God; inlisted in their service almost all the booksellers, and of course the printers, of Germany; inundated the country with books, replete with infidelity, irreligion, immorality, and obscenity; prohibited the printing, and prevented the sale, of books of the contrary character; decried and ridiculed them when published in spite of their efforts; panegyrized and trumpeted those of themselves and their coadjutors; and in a word made more numerous, more diversified, and more strenuous exertions, than an active imagination would have preconceived.

TO these exertions their success has been proportioned. Multitudes of the Germans, notwithstanding the gravity, steadiness, and sobriety of their national character, have become either partial or entire converts to these wretched doctrines; numerous societies have been established among them; the public faith and morals have been unhinged; and the political and religious affairs of that empire have assumed an aspect, which forebodes its total ruin. In France, also, Illuminatism has been eagerly and extensively adopted; and those men, who have had, successively, the chief direction of the public affairs of that country, have been members of this society. Societies have also been erected in Switzerland and Italy, and have contributed probably to the success of the French, and to the overthrow of religion and government, in those countries. Mentz was delivered up to Custine by the Illuminati; and that General appears to have been guillotined, because he declined to encourage the same treachery with respect to Manheim.

NOR have England and Scotland escaped the contagion. Several societies have been erected in boch of those countries. Nay in the private papers, seized in the custody of the leading members in Germany, several such societies are recorded as having been erected in America, before the year 1786. (See Robinson’s Conspiracy and the Abbe Barruel’s Memoirs of the History of Jacobinism.)

IT is a remarkable fact, that a large proportion of the sentiments, here stated, have been publicly avowed and applauded in the French legislature. The being and providence of God have been repeatedly denied and ridiculed. Christ has been mocked with the grossest insult. Death, by a solemn legislative decree has been declared to be an eternal sleep. Marriage has been degraded to a farce, and the community, by the law of divorce, invited to universal prostitution In the school of public instruction atheism is professedly taught; and at an audience before the legislature, Nov. 30, 1793, the head scholar declared, that he and his schoolfellows detested a God; a declaration received by the members with unbounded applause, and rewarded with the fraternal kiss of the president, and with the honors of the sitting. (See Gifford’s Letter to Erskine.)

I presume I have sufficiently proved the fulfilment of the second part of this remarkable prophesy; and shewn, that doctrines and teachers, answering to the description, have arisen in the very countries specified, and that they are rapidly spreading through the world, to engage mankind in an open and professed war against God. I shall only add, that the titles of these philosophistical books have, in various instances, been too obscene to admit of a translation by a virtuous man, and in a decent state of society. So fully are these teachers entitled to the epithet unclean.

ASSUMING now as just, for the purposes of this discourse, the explanation, which has been given, I shall proceed to consider the import of the Text.

THE Text is an affectionate address of the Redeemer to his children, teaching them that conduct, which he wills them especially to pursue in this alarming season. It is the great practical remark, drawn by infinite Wisdom and Goodness from a most solemn sermon, and cannot fail therefore to merit our highest attention. Had he not, while recounting the extensive and dreadful convulsion, described in the context, made a declaration of this nature, there would have been little room for the exercise of any emotions, beside those of terror and despair. The gloom would have been universal and entire; a blank midnight without a star to cheer the solitary darkness. But here a hope, a promise, is furnished to such as obey the injunction, by which it is followed; a luminary like that, which shone to the wise men of the east, is lighted up to guide our steps to the Author of peace and salvation.

BLESSED, even in this calamitous season, saith the Saviour of men, is he that watcheth, and keepeth his garments, lest he walk naked and they see his shame.

SIN is the nakedness and shame of the scriptures, and righteousness the garment which covers it. To watch and keep the garments is, of course, so to observe the heart and the life, so carefully to resist temptation and abstain from sin, and so faithfully to cultivate holiness and perform duty, that the heart and the life shall be adorned with the white robes of evangelical virtue, the unspotted attire of spiritual beauty.

THE cautionary precept given to us by our Lord is, therefore,

THAT WE SHOULD BE EMINENTLY WATCHFUL TO PERFORM OUR DUTY FAITHFULLY, IN THE TRYING PERIOD, IN WHICH OUR LOT IS CAST.

TO those, who obey, a certain blessing is secured by the promise of the Redeemer.

THE great and general object, aimed at by this command, and by every other, is private, personal obedience and reformation of life; personal piety, righteousness, and temperance.

TO every man is by his Creator especially committed the care of himself; of his time, his talents, and his soul. He knows, or may know, better than any other man, his wants, his sins, and his dangers, and of course the means of relief, reformation, and escape. No one, so well as he, can watch the approach of temptation, so feelingly pray for divine assistance, or so profitably resolve on future obedience. In truth no resolutions, no prayers, no watchfulness of others, will profit him at all, unless seconded by his own.

No other person can make any useful impressions on our hearts, or our lives, unless by rousing in us the necessary exertions. All extraneous labours terminate in this single point: it is the end of every doctrine, exhortation, and reproof, of every moral and religious institution.

THE manner, in which such obedience is to be performed, and such reformation accomplished, is described to you weekly in the desk, and daily in the scriptures. A detail of it, therefore, will not be necessary, nor expected, on the present occasion. You already know what is to be done, and the manner in which it is to be done. You need not be told, that you are to use all efforts of your own, and to look humbly and continually to God to render those efforts successful; that you are to resist carefully and faithfully every approaching temptation, and every rising sin; that you are to resolve on newness of life, and to seize every occasion, as it presents itself, to honour God, and to bless your fellow men; that you are strenuously to contend against evil habits, and watchfully to cherish good ones; and that you are constantly to aim at uniformity and eminency in a holy life, and to “adorn the doctrine of God our Saviour in all things.”

BUT it may be necessary to remind you, that personal obedience and reformation is the foundation, and the sum, of all national worth and prosperity. If each man conducts himself aright, the community cannot be conducted wrong. If the private life be unblamable, the public state must be commendable and happy.

INDIVIDUALS are often apt to consider their own private conduct as of small importance to the public welfare. This opinion is wholly erroneous and highly mischievous. No man can adopt it, who believes, and remembers, the declarations of God. If “one sinner destroyeth much good,” if “the effectual fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much,” if ten righteous persons, found in the polluted cities of the vale of Siddim, would have saved them from destruction, the personal conduct of no individual can be insignificant to the safety and happiness of a nation. On the contrary, the advantages to the public of private virtue, faithful prayer and edifying example, cannot be calculated. No one can conjecture how many will be made better, safer, and happier, by the virtue of one.

WHEREVER wealth, politeness, talents, and office, lend their aid to the inherent efficacy of virtue, its influence is proportionally greater. In this case the example is seen by greater numbers, is regarded with more respectful attention, and felt with greater force. The piety of Hezekiah reformed and saved a nation. Men far inferior in station to kings, and possessed of far humbler means of doing good, may still easily circulate through multitudes both virtue and happiness. The beggar on the dunghill may become a public blessing. Every parent, if a faithful one, is a public blessing of course. How delightful a path of patriotism is this?

IT is also to be remembered, that this is the way, in which the chief good, ever placed in the power of most persons, is to be done. If this opportunity of serving God, and befriending mankind, be lost, no other will by the great body of men ever be found. Few persons can be concerned in settling systems of faith, moulding forms of government, regulating nations, or establishing empires. But almost all can train up a family for God, instil piety, justice, kindness and truth, distribute peace and comfort around a neighbourhood, receive the poor and the outcast into their houses, tend the bed of sickness, pour balm into the wounds of pain, and awaken a smile in the aspect of sorrow. In the secret and lowly vale of life, virtue in its most lovely attire delights to dwell. There God, with peculiar complacency, most frequently finds the inestimable ornament of a meek and quiet spirit; and there the morning and the evening incense ascends with peculiar fragrance to heaven. When angels became the visitors, and the guests, of Abraham, he was a simple husbandman.

BESIDES, this is the great mean of personal safety and happiness. No good man was ever forgotten, or neglected, of God. To him duty is always safety. Around the tabernacle of every one, that feareth God, the angel of protection will encamp, and save him from the impending evil.

- AMONG the particular duties required by this precept, and at the present time, none holds a higher place than the observation of the Sabbath.

THE Sabbath and its ordinances have ever been the great means of all moral good to mankind. The faithful observation of the sabbath is, therefore, one of the chief duties and interests of men; but the present time furnishes reasons, peculiar, at least in degree, for exemplary regard to this divine institution. The enemies of God have by private argument, ridicule, and influence, and by public decrees, pointed their especial malignity against the Sabbath; and have expected, and not without reason, that, if they could annihilate it, they should overthrow christianity. From them we cannot but learn its importance. Enemies usually discern, with more sagacity, the most promising point of attack, than those who are to be attacked. In this point are they to be peculiarly opposed. Here, peculiarly, are their designs to be baffled. If they fail here, they will finally fail. Christianity cannot fall, but by the neglect of the Sabbath.

I HAVE been credibly informed, that, some years before the Revolution, an eminent philosopher of this country, now deceased, declared to David Hume, that Christianity would be exterminated from the American colonies within a century from that time. The opinion has doubtless been often declared and extensively imbibed; and has probably furnished our enemies their chief hopes of success. Where religion prevails, their system cannot succeed. Where religion prevails, Illuminatism cannot make disciples, a French directory cannot govern, a nation cannot be made slaves, nor villains, nor atheists, nor beasts. To destroy us, therefore, in this dreadful sense, our enemies must first destroy our Sabbath, and seduce us from the house of God.

RELIGION and Liberty are the two great objects of defensive war. Conjoined, they unite all the feelings, and call forth all the energies, of man. In defense of them, nations contend with the spirit of the Maccabees; “one will chase a thousand, and two put ten thousand to flight.” The Dutch, in defense of them, few and feeble as they were in their infancy, assumed a gigantic courage, and grew like the fabled sons of Alous to an instantaneous and gigantic strength, broke the arms of the Spanish empire, swept its fleets from the ocean, pulled down its pride, plundered its treasures, captivated its dependencies, and forced its haughty monarch to a peace on their own terms. Religion and liberty are the meat and the drink of the body politic. Withdraw one of them, and it languishes, consumes, and dies. If indifference to either at any time becomes the prevailing character of a people, one half of their motives to vigorous defense is lost, and the hopes of their enemies are proportionally increased. Here, eminently, they are inseparable. Without religion we may possibly retain the freedom of savages, bears, and wolves; but not the freedom of New-England. If our religion were gone, our state of society would perish with it; and nothing would be left, which would be worth defending. Our children of course, if not ourselves, would be prepared, as the ox for the slaughter, to become the victims of conquest, tyranny, and atheism.

THE Sabbath, with its ordinances, constitutes the bond of union to christians; the badge by which they know each other; their rallying point; the standard of their host. Beside public worship they have no means of effectual descrimination. To preserve this is to us a prime interest and duty. In no way can we so preserve, or so announce to others, our character as christians; or so effectually prevent our nakedness and shame from being seen by our enemies. Now, more than ever, we are “not to be ashamed of the gospel of Christ.” Now, more than ever, are we to stand forth to the eye of our enemies, and of the world, as open, determined christians; as the followers of Christ; as the friends of God. Every man, therefore, who loves his country, or his religion, ought to feel, that he serves, or injures, both, as he celebrates, or neglects, the Sabbath. By the devout observation of this holy day he will reform himself, increase his piety, heighten his love to his country, and confirm his determination to defend all that merits his regard. He will become a better man, and a better citizen.

THE house of God is also the house of social prayer. Here nations meet with God to ask, and to receive, national blessings. On the Sabbath, and in the sanctuary, the children of the Redeemer will, to the end of the world, assemble for this glorious end. Here he is ever present to give more than they can ask. If we faithfully unite, here, in seeking his protection, “no weapon formed against us will prosper.”

- ANOTHER duty, to which we are also eminently called, is an entire separation from our enemies. Among the moral duties of man none hold a higher rank than political ones, and among our own political duties none is more plain, or more absolute, than that which I have now mentioned.

IN the eighteenth chapter of this prophecy, in which the dreadful effects of the seventh vial are particularly described, this duty is expressly enjoined on christians by a voice from Heaven. “And I heard another voice from heaven, saying, Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins, and that ye receive not of her plagues.” Under the evils and dangers of the sixth vial, the command in the Text was given; under those of the seventh, the command which we are now considering. The world is already far advanced in the period of the sixth. In the Text we are informed, that the Redeemer will hasten the progress of his vengeance on the enemies of his church, during the effusion of the two last vials. If, therefore, the judgments of the seventh are not already begun, a fact of which I am doubtful, they certainly cannot be distant. The present time is, of course, the very period for which this command was given.

THE two great reasons for the command are subjoined to it by the Saviour—”that ye be not partakers of her sins; and that ye receive not of her plagues;” and each is a reason of incomprehensible magnitude.

THE sins of these enemies of Christ, and Christians, are of numbers and degrees, which mock account and description. All that the malice and atheism of the Dragon, the cruelty and rapacity of the Beast, and the fraud and deceit of the false Prophet, can generate, or accomplish, swell the list. No personal, or national interest of man has been uninvaded; no impious sentiment, or action, against God has been spared; no malignant hostility against Christ, and his religion, has been unattempted. Justice, truth, kindness, piety, and moral obligation universally, have been, not merely trodden under foot; this might have resulted from vehemence and passion; but ridiculed, spurned, and insulted, as the childish bugbears of driveling idiocy. Chastity and decency have been alike turned out of doors; and shame and pollution called out of their dens to the hall of distinction, and the chair of state. Nor has any art, violence, or means, been unemployed to accomplish these evils.

FOR what end shall we be connected with men, of whom this is the character and conduct? Is it that we may assume the same character, and pursue the same conduct? Is it, that our churches may become temples of reason, our Sabbath a decade, and our psalms of praise Marseillois hymns? Is it, that we may change our holy worship into a dance of Jacobin phrenzy, and that we may behold a strumpet personating a Goddess on the altars of JEHOVAH? Is it that we may see the Bible cast into a bonfire, the vessels of the sacramental supper borne by an ass in public procession, and our children, either wheedled or terrified, uniting in the mob, chanting mockeries against God, and hailing in the sounds of Caira the ruin of their religion, and the loss of their souls? Is it, that we may see our wives and daughters the victims of legal prostitution; soberly dishonoured; speciously polluted; the outcasts of delicacy and virtue, and the lothing of God and man? Is it, that we may see, in our public papers, a solemn comparison drawn by an American Mother club between the Lord Jesus Christ and a new Marat; and the fiend of malice and fraud exalted above the glorious Redeemer?

SHALL we, my brethren, become partakers of these sins? Shall we introduce them into our government, our schools, our families? Shall our sons become the disciples of Voltaire, and the dragoons of Marat (See a four years Residence in France, lately published by Mr. Cornelius Davis of New York. This is a most valuable and interesting work, and exhibits the French Revolution in a far more perfect light than any book I have seen. It ought to be read by every American.); or our daughters the concubines of the Illuminati?

SOME of my audience may perhaps say, “We do not believe such crimes to have existed.” The people of Jerusalem did not believe, that they were in danger, until the Chaldeans surrounded their walls. The people of Laish were secure, when the children of Dan lay in ambush around their city. There are in every place, and in every age, persons “who are settled upon their lees,” who take pride in disbelief, and “who say in their heart, the Lord will not do good, neither will he do evil.” Some persons disbelieve through ignorance; some choose not to be informed; and some determine not to be convinced. The two last classes cannot be persuaded. The first may, perhaps, be at least alarmed, when they are told, that the evidence of all this, and much more, is complete, that it has been produced to the public, and may with a little pains-taking be known by themselves.

THERE are others, who, admitting the fact, deny the danger. “If others,” say they, “are ever so abandoned, we need not adopt either their principles, or their practices.” Common sense has however declared, two thousand years ago, and God has sanctioned the declaration, that “Evil communications corrupt good manners.” Of this truth all human experience is one continued and melancholy proof. I need only add, that these persons are prepared to become the first victims of the corruption by this very selfconfidence and security.

SHOULD we, however, in a forbidden connection with these enemies of God, escape, against all hope, from moral ruin, we shall still receive our share of their plagues. This is the certain dictate of the prophetical injunction; and our own experience, and that of nations more intimately connected with them, has already proved its truth.

LOOK for conviction to Belgium; sunk into the dust of insignificance and meanness, plundered, insulted, forgotten, never to rise more. See Batavia wallowing in the same dust; the butt of fraud, rapacity, and derision, struggling in the last stages of life, and searching anxiously to find a quiet grave. See Venice sold in the shambles, and made the small change of a political bargain. Turn your eyes to Switzerland, and behold its happiness, and its hopes, cut off at a single stroke: happiness, erected with the labour and the wisdom of three centuries; hopes, that not long since hailed the blessings of centuries yet to come. What have they spread, but crimes and miseries; Where have they trodden, but to waste, to pollute, and to destroy?

ALL connection with them has been pestilential. Among ourselves it has generated nothing but infidelity, irreligion, faction, rebellion, the ruin of peace, and the loss of property. In Spain, in the Sardinian monarchy, in Genoa, it has sunk the national character, blasted national independence, rooted out confidence, and forerun destruction.

BUT France itself has been the chief seat of the evils, wrought by these men. The unhappy and ever to be pitied inhabitants of that country, a great part of whom are doubtless of a character similar to that of the peaceable citizens of other countries, and have probably no voluntary concern in accomplishing these evils, have themselves suffered far more from the hands of philosophists, and their followers, than the inhabitants of any other country. General Danican, a French officer, asserts in his memoirs, lately published, that three millions of Frenchmen have perished in the Revolution. Of this amazing destruction the causes by which it was produced, the principles on which it was founded, and the modes in which it was conducted, are an aggravation, that admits no bound. The butchery of the stall, and the slaughter of the stye, are scenes of deeper remorse, and softened with more sensibility. The siege of Lyons, and the judicial massacres at Nantes, stand, since the crucifixion, alone in the volume of human crimes. The misery of man never before reached the extreme of agony, nor the infamy of man its consummation. Collot D. Herbois and his satellites, Carrier and his associates, would claim eminence in a world of fiends, and will be marked with distinction in the future hissings of the universe. No guilt so deeply died in blood, since the phrenzied malice of Calvary, will probably so amaze the assembly of the final day; and Nantes and Lyons may, without a hyperbole, obtain a literal immortality in a remembrance revived beyond the grave.

IN which of these plagues, my brethren, are you willing to share? Which of them will you transmit as a legacy to your children?

WOULD you escape, you must separate yourselves. Would you wholly escape, you must be wholly separated. I do not intend, that you must not buy and sell, or exhibit the common offices of justice and good will; but you are bound by the voice of reason, of duty, of safety, and of God, to shun all such connection with them, as will interweave your sentiments or your friendship, your religion or your policy, with theirs. You cannot otherwise fail of partaking in their guilt, and receiving of their plagues.

4thly. ANOTHER duty, to which we are no less forcibly called, is union among ourselves.

THE same divine Person, who spoke in the Text, hath also said, “A house, a kingdom, divided against itself cannot stand.” A divided family will destroy itself. A divided nation will anticipate ruin, prepared by its enemies. Switzerland, Geneva, Genoa, Venice, the Sardinian territories, Belgium, and Batavia, are melancholy examples of the truth of this declaration of our Saviour; beacons, which warn, with a gloomy and dreadful light, the nations who survive their ruin.

THE great bond of union to every people is its government. This destroyed, or distrusted, there is no center left of intelligence, counsel, or action; no system of purposes, or measures; no point of rallying, or confidence. When a nation is ready to say, “What part have we in David, or what inheritance in the son of Jesse?” it will naturally subjoin, “Every man to his tent, O Israel!”

THE candour and uprightness, with which our own government has acted in the progress of the present controversy, have forced encomiums even from its most bitter opposers, and excited the warmest approbation and applause of all its friends. Few objects could be more important, auspicious, or gratifying to christians, than to see the conduct of their rulers such, as they can, with boldness of access, bring before their God, and fearlessly commend to his favour and protection.

IN men, possessed of similar candour, adherence to our government, in the present crisis, may be regarded as a thing of course. They need not be informed, that the existing rulers must be the directors of our public affairs, and the only directors; that their views and measures will not and cannot always accord with the judgment of individuals, as the opinions of individuals accord no better with each other; that the officers of government are possessed of better information than private persons can be; that, if they had the same information, they would probably coincide with the opinions of their rulers; that confidence must be placed in men, imperfect as they are, in all human affairs, or no important business can be done; and that men of known and tried probity are fully deserving of that confidence.

AT the present time this adherence ought to be unequivocally manifested. In a land of universal suffrage, where every individual is possessed of much personal consequence as in ours, the government ought, especially in great measures, to be as secure, as may be, of the harmonious and cheerful co-operation of the citizens. All success, here, depends on the hearty concurrence of the community; and no occasion ever called for it more.

BUT there are, even in this State, persons, who are opposed to the government. To them I observe, That the government of France has destroyed the independence of every nation, which has confided in it.

THAT every such nation has been ruined by its internal divisions, especially by the separation of the people from their government.

THAT they have attempted to accomplish our ruin by the same means, and will certainly accomplish it, if they can;

THAT the miseries suffered by the subjugated nations have been numberless and extreme, involving the loss of national honour, the immense plunder of public and private property, the conflagration of churches and dwellings, the total ruin of families, the butchery of great multitudes of fathers and sons, and the most deplorable dishonour of wives and daughters;

THAT the same miseries will be repeated here, if in their power.

THAT there is, under God, no mean of escaping this ruin, but union among ourselves, and unshaken adherence to the existing government;

THAT themselves have an infinitely higher interest in preserving the independence of their country, than in any thing, which can exist, should it be conquered;

THAT they must stand, or fall, with their country; since the French, like all other conquerors, though they may for a little time regard them, as aids and friends, with a seeming partiality, will soon lose that partiality in a general contempt and hatred for them, as Americans. That should they, contrary to all experience, escape these evils, their children will suffer them as extensively as those of their neighbours; and

THAT to oppose, or neglect, the defence of their country, is to stab the breast, from which they have drawn their life.

I KNOW not that even these considerations will prevail: if they do not, nothing can be suggested by me, which will have efficacy. I must leave them, therefore, to their consciences, and their God.

IN the mean time, since the great facts, of which this controversy has consisted, have not, during the preceding periods, been thoroughly known, or believed, by all; and since all questions of expediency will be viewed differently by different eyes; I cannot but urge a general spirit of conciliation. To men labouring under mere mistakes, and prejudices void of malignity, hard names are in most cases unhappily applied, and unkindness is unwisely exhibited. Multitudes, heretofore attached to France with great ardour, have, from full conviction of the necessity of changing their sentiments and their conduct, come forth in the most decisive language, and determined conduct, of defenders of their country. More are daily exhibiting the same spirit and measures. Almost all native Americans will, I doubt not, speedily appear in the same ranks; and none should, in my opinion, be discouraged by useless obloquy.

- ANOTHER duty, injoined in the text, and highly incumbent on us at this time, is unshaken firmness in our opposition.

A STEADY and invincible firmness is the chief instrument of great atchievements. It is the prime mean of great wealth, learning, wisdom, power and virtue; and without it nothing noble or useful is usually accomplished. Without it our separation from our enemies, and our union among ourselves, will avail to no end. The cause is too complex, the object too important, to be determined by a single effort. It is infinitely too important to be given up, let the consequence be what it may. No evils, which can flow from resistance, can be so great as those, which must flow from submission. Great sacrifices of property, of peace, and of life, we may be called to make, but they will fall short of complete ruin. If they should not, it will be more desirable, beyond computation, to fall in the honourable and faithful defence of our families, our country, and our religion, than to survive, the melancholy, debased, and guilty spectators of the ruin of all. We contend for all that is, or ought to be, dear to man. Our cause is eminently that, in which “he who seeketh to save his life shall lose it, and he who loseth it,” in obedience to the command of his Master, “shall find it” beyond the grave. To our enemies we have done no wrong. Unspotted justice looks down on all our public measures with a smile. We fight for that, for which we can pray. We fight for the lives, the honor, the safety, of our wives and children, for the religion of our fathers, and for the liberty, “with which Christ hath made us free.” “We jeopard our lives,” that our children may inherit these glorious blessings, be rescued from the grinding insolence of foreign despotism, and saved from the corruption and perdition of foreign atheism. I am a father. I feel the usual parental tenderness for my children. I have long soothed the approach of declining years with the fond hope of seeing my sons serving God and their generation around me. But from cool conviction I declare in this solemn place, I would far rather follow them one by one to an untimely grave, than to behold them, however prosperous, the victims of philosophism. What could I then believe, but that they were “nigh unto cursing, and that their end was to be burned.”

FROM two sources only are we in danger of irresolution; Avarice, and a reliance on those fair professions, which our enemies have begun to make, and which they will doubtless continue to make, in degrees, and with insidiousness, still greater.

ON the first of these sources I observe, that, if we grudge a part of our property in the defence of our country, we lose the whole; and not only the whole of our property, but all our comforts, and all our hopes. Every enjoyment of life, every solace of sorrow, will be offered up in one vast hecatomb at the shrine of pride, plunder, impurity, and atheism. Those “who fear not God, regard not man.” All interests, beside their own, are in the view of such men the sport of wantonness, of insolence, and of a heart of millstone. They and their engines will soon tell you, if you do not put it out of their power, as one of the same engines told the miserable inhabitants of Neuwied (in Germany) unhappily placing confidence in their professions.

Hear the story, in the words of Professor Robison, “If ever there was a spot upon earth, where men may be happy in a state of cultivated society, it was the little principality of Neuwied. I saw it in 1770. The town was neat, and the palace handsome and in good state. But the country was beyond conception delightful; not a cottage that was out of repair; not a hedge out of order. It had been the hobby of the Prince (pardon me the word) who made it his daily employment to go through his principality, and assist every housholder, of whatever condition, with his advice and with his purse; and when a freeholder could not of himself put things into a thriving condition, the Prince sent his workmen and did it for him. He endowed schools for the common people and two academies for the gentry and the people of business. He gave little portions to the daughters, and prizes to the well-behaving sons of the labouring people. His own houshold was a pattern of elegance and economy; his sons were sent to Paris, to learn elegance, and to England, to learn science and agriculture. In short the whole was like a romance, and was indeed romantic. I heard it spoken of with a smile at the table of the Bishop of Treves, and was induced to see it the next day as a curiosity. Yet even here the fanaticism of Knigge (one of the founders of the Illuminati) would distribute his poison, and tell the blinded people that they were in a state of sin and misery, that their Prince was a despot, and that they would never be happy ’till he was made to fly, and ’till they were made all equal.”

“THEY got their wish. The swarm of French locusts sat down at Neuwied’s beautiful fields, in 1793, and intrenched themselves; and in three months Prince’s and Farmers’ houses, and cottages, and schools, and academies, all vanished. When they complained of their miseries to the French General, René le Grand, he replied, with a contemptuous and cutting laugh, “All is ours. We have left you your eyes to cry.”

WILL you trust such professions? Have not your enemies made them to every country, which they have subjugated? Have they fulfilled them to one? Will they prove more sincere to you? Have they not deceived you in every expectation hitherto? On what grounds can you rely on them hereafter?

WILL you grudge your property for the defence of itself, of your families, of yourselves. Will you preserve it to pay the price of a Dutch loan? to have it put in requisition by the French Directory? to label it on your doors, that they may, without trouble and without a tax bill, send their soldiers and take it for the use of the Republic? Will you keep it to assist them to pay their fleets and armies for subduing you? and to maintain their forts and garrisons for keeping you in subjection? Shall it become the purchase of a French fete, holden to commemorate the massacres of the 10th of August, the butcheries of the 3d of September, or the murder of Louis the 16th, your former benefactor? Shall it furnish the means for Representatives of the people to roll through your streets on the wheels of splendour, to imprison your sons and fathers; to seize on all the comforts, which you have earned with toil, and laid up with care; and to gather your wives, sisters, and daughters, into their brutal seraglios? Shall it become the price of the guillotine, and pay the expense of cleansing your streets from brooks of human blood?

WILL you rely on men whose principles justify falshood, injustice, and cruelty? Will you trust philosophists? men who set truth at nought, who make justice a butt of mockery, who deny the being and providence of God, and laugh at the interests and sufferings of men? Think not that such men can change. They can scarcely be worse. There is not a hope that they will become better.

BUT perhaps you may be alarmed by the power, and the successes, of your enemies. I am warranted to declare, that the ablest judge of this subject in America has said, that, if we are united, firm, and faithful to ourselves, neither France, nor all Europe, can subdue these States. Against other nations they contended with great and decisive advantages. Those nations were near to them, were divided, feeble, corrupted, seduced by philosophists, slaves of despotism, and separated from their government. None of these characters can be applied to us, unless we voluntarily retain those, which depend on ourselves. Three thousand miles of ocean spread between us and our enemies, to enfeeble and disappoint their efforts. They will not here contend with silken Italians, with divided Swissers, nor with self-surrendered Belgians and Batavians. They will find a hardy race of freemen, uncorrupted by luxury, unbroken by despotism; enlightened to understand their privileges, glowing with independence, and determined to be free, or to die: men who love, and who will defend, their familes, their country, and their religion: men fresh from triumph, and strong in a recent and victorious Revolution.

Doubled, since that Revolution began, in their numbers, and quadrupled in their resources and advantages, at home, in a country formed to disappoint invasion, and to prosper defence, under leaders skilled in all the arts and duties of war, and trained in the path of success, they have, if united, firm, and faithful, every thing to hope, and, beside the common evils of war, nothing to fear.

THINK not that I trust in chariots and in horses. My own reliance is, I hope, I ardently hope yours is, also, on the Lord our God. All these are his most merciful blessings, and, as such, most supporting consolations to us. They are the very means, which he has provided for our safety, and our hope. Stupidity, sloth, and ingratitude, can alone be blind to them as tokens for good. We are not, my brethren, to look for miracles, nor to expect God to accomplish them. We are to trust in him for the blessings of a regular and merciful providence. Such a providence is over us for good. I have recited abundant proofs, and could easily recite many more. All these are means, with which we are to plant, and to water, and in answer to our prayers God will certainly give the increase.

BUT I am peculiarly confident in the promised blessing of the Text. Our contention is a plain duty to God. The same glorious Person, who has commanded it, has promised to crown our obedience with his blessing; and has thus illumined this gloomy prediction, and shed the dawn of hope and comfort over this melancholy period.

TO you the promise is eminently supporting. He has won your faith by the great things he has already done for your fathers, and for you. The same Almighty Hand, which destroyed the fleet of Chebucto by the storm, and whelmed it in the deep; which conducted into the arms of Manly, and of Mugford, those means of war, which for the time saved your country; which raised up your Washington to guide your armies and your councils; which united you with your brethren against every expectation and hope; which disappointed the devices of enemies without, and traitors within; which bade the winds and the waves fight for you at Yorktown; which has, in later periods, repeatedly disclosed the machinations of your enemies, and which has now roused a noble spirit of resistance to intrigue and to terror; will accomplish for you a final deliverance from the hand of those, “who seek your hurt.” He has been your fathers’ God, and he will be yours.

LOOK through the history of your country. You will find scarcely less glorious and wonderful proofs of divine protection and deliverance, uniformly administered through every period of our existence as a people, than shone to the people of Israel in Egypt, in the wilderness, and in Canaan. Can it be believed, can it be, that Christianity has been so planted here, the Church of God so established, so happy a Government constituted, and so desirable a state of Society begun, merely to shew them to the world, and then destroy them? No instance can be found in the providence of God, in which a nation so wonderfully established, and preserved, has been overthrown, until it had progressed farther in corruption. We may be cast down; but experience only will prove to me, that we shall be destroyed.

BUT the consideration, which ought of itself to decide your opinions and your conduct, and which adds immense weight to all the others, is that the alternative, as exhibited in the prediction, and in providence, is beyond measure dreadful, and is at hand. “Behold,” saith the Saviour, “I come as a thief”—suddenly, unexpectedly, alarmingly— as that wasting enemy, the burglar, breaks up the house in the hour of darkness, when all the inhabitants are lost in sleep and security. How strongly do the great events of the present day shew this awful advent of the King of Kings to be at the doors?

TURN your eyes, for a moment, to the face of providence, and mark its new and surprising appearance. The Jews, for the first time since the destruction of Jerusalem by Adrian, have, in these States, been admitted to the rights of citizenship; and have since been admitted to the same rights in Prussia. They have also, as we are informed, appointed a solemn delegation to examine the evidences of Christianity. In the Austrian dominions, it is asserted, they have agreed to observe the Christian Sabbath; and in England, have in considerable numbers embraced the Christian religion. New and unprecedented efforts have been made, and are fast increasing, in England, Scotland, Germany, and the United States, for the conversion of the Heathen. Measures have, in Europe, and in America, been adopted, and are still enlarging, for putting an end to the African slavery, which will within a moderate period bring it to an end. Mohammedism is nearly extinct in Persia, one of the chief supports of that imposture. In Turkey, its other great support, the throne totters to its fall. The great Calamities of the present period have fallen, also, almost exclusively upon the Antichristian empire; and almost every part of that empire has drunk deeply of the cup. France, Belgium, Spain, Ireland, the Sardinian monarchy, the Austrian dominions, Venice, Genoa, popish Switzerland, the Ecclesiastical State, popish Germany, Poland, and the French West-Indies, have all been visited with judgments wonderful and terrible; and in exact accordance with prophecy have furthered their own ruin. The Kings, or states, of this empire are now plainly “hating the whore, eating her flesh, and burning her with fire.” Batavia, Protestant Switzerland, some parts of protestant Germany, and Geneva, have most unwisely, not to say wickedly, refused “to come out” and have therefore “partaken of the sins, and received of the plagues,” of their enemies. To the same unhappy cause our own smartings may all be traced; but blessed be God, there is reason to hope, that “we are escaping from the snare of the fowler.”

SO sudden, so unexpected, so alarming a state of things has not existed since the deluge. Every mouth proclaims, every eye looks its astonishment. Wonders daily succeed wonders, and are beginning to be regarded as the standing course of things. As they are of so many kinds, exist in so many places, and respect so many objects; kinds, places and objects, all marked out in prophecy, exhibited as parts of one closely united system, and to be expected at the present time; they shew that this affecting declaration is even now fulfilling in a surprising manner, and that the advent of Christ is at least at our doors. Think how awful this period is. Think what convulsions, what calamities, are portended by that great Voice out of the temple of Heaven from the Throne.—”It is done!” by the voices and thunderings and lightnings, by the unprecedented shaking of the earth, the unexampled plague of hailstones, the fleeing of the islands, the vanishing of the mountains, the rending asunder of the Antichristian empire, the united ascent of all its sins before God, the falling of the cities of the nations, the general embattling of mankind against their Maker, and their final overthrow, in such immense numbers, that “all the fowls shall be filled with their flesh.”

“GOD is jealous, and the Lord revengeth; the Lord revengeth and is furious; the Lord will take vengeance on his adversaries, he reserveth wrath for his enemies. The Lord is slow to anger, and great in power, and will not at all acquit the wicked. The Lord hath his way in the whirlwind, and in the storm, and the clouds are the dust of his feet. The mountains quake at him, and the hills melt; and the earth is burnt at his presence, yea the world, and all that dwell therein. Who can stand before his indignation? Who can abide in the fierceness of his anger?”

IN this amazing conflict, amidst this stupendous and immeasurable ruin, how transporting the thought, that safety and peace may be certainly found. O thou God of our fathers! our own God! and the God of our children! enable us so to watch, and keep our garments, in this solemn day, that our shame appear not, and that both we and our posterity may be entitled to the blessing which thou hast promised. AMEN.

John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography: