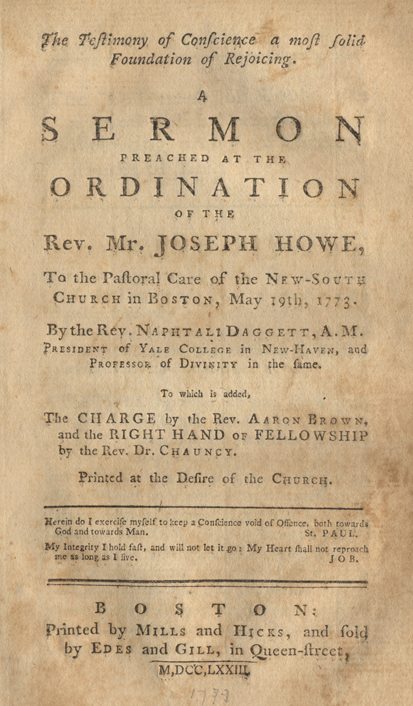

Naphtali Daggett (1727-1780) graduated from Yale in 1748. He was a pastor of a church in Long Island (1751-1756), professor of divinity at Yale (1756-1780), and president pro tempore at Yale (1766-1777). Daggett was taken prisoner in 1779 after personally taking part in fighting the British. He preached the following sermon in Boston on May 19, 1773.

A

SERMON

PREACHED AT THE

ORDINATION

OF THE

Rev. Joseph Howe,

To the Pastoral Care of the New-South Church in Boston, May 19th, 1773.

By the Rev. Naphtali Daggett, A. M.

President of Yale College in New-Haven, and

Professor of Divinity in the same.

To which is added,

The CHARGE by the Rev. Aaron Brown, and the RIGHT HAND

Of FELLOWSHIP by the Rev. Dr. Chauncy.

Printed at the Desire of the Church.

Herein do I exercise myself to keep a Conscience void of Offence, both towards God and towards Man.

St. PAUL.

My Integrity I hold fast, and will not let it go: My Heart shall not reproach me as long as I live.

JOB.

II COR. I. 12.

For our Rejoicing is this, the Testimony of our Conscience, that in Simplicity and godly Sincerity, not with fleshly Wisdom, but by the Grace of God we have had our Conversation in the World, and more abundantly to you-wards.

The Apostles of our Lord Jesus Christ had a very arduous and trying service enjoined them.—They were required to go forth into all the world, and teach all nations the Christian religion in direct opposition to the numerous, deep-rooted prejudices, corruptions and false religions then established upon earth; and to insist upon it, that all, who heard them, should believe in, trust and submit to One, as their God and Saviour, who had been lately executed in the ignominious character of a malefactor by his own nation, the Jews.

It was easy to foresee, that in the execution of this their commission they would necessarily meet with the most virulent opposition and persecution from an ignorant, degenerated, prejudiced world, who had slain their Lord and Master with wicked hands. And he had indeed clearly assured them before hand of this event; that they would be hated and persecuted of all men for his sake.

They had neither learning, civil or ecclesiastical power, nor the encouragement of the great ones of the earth to befriend their undertaking. On the contrary, all these were firmly and inveterately leagued against them, with Satan, the prince of the powers of the air, as their head and leader, who had long indulged the most implacable spite against the seed of the woman. Under these discouraging circumstances, it must have been the most extravagant, romantic enterprise ever attempted by mad-men, to set out upon the design of Christianizing the world, unless they had been absolutely certain of the truth of their doctrine, their mission from God, and his unfailing promise of assistance and success.

But God doubtless chose this chose this method for bringing the world to the Christian faith; that it might most evidently appear to after ages to have been effected, not by might, by worldly power and wisdom; but by the spirit of the Lord. So that the surprising success and progress of the gospel under all those unfavourable and forbidding circumstances might be a lasting evidence of its divine original, while at the same time 1 “the foolishness of God is hereby demonstrated to be wiser than man; and the weakness of God to be stronger than man.” The apostles in first propagating the gospel had nothing to support them but the evidence of truth, the God-like grandeur and dignity of their doctrines, the holiness of their lives, and those incontestable miracles which they were enabled to work in confirmation of their divine mission, together with the promised influences of the Holy Spirit upon the minds and hearts of men. By these they made their way surprisingly through all imaginable opposition, converting great multitudes to the Christian faith; yet not without meeting with the most cruel persecutions, reproaches, scourging, imprisonment and death itself; which sufficiently evidenced, how opposite the world was to embracing the religion of Jesus. And while multitudes died martyrs in the cause, still the cause lived, and gained ground, according to the prediction of Gamaliel,– 2 “If it be of God, ye cannot overthrow it.”

The apostle in this chapter mentions some of the tribulations, distresses and trials they had to undergo for the sake of the gospel. “The sufferings of Christ, says he, i. e. sufferings in some measure resembling his, abound in us:–For we would not, brethren, have you ignorant of our trouble which came to us in Asia, that we were pressed out of measure, above strength, insomuch that we despaired even of life.” In another place in this epistle he gives a more particular, but summary account of his sufferings;– 3 “In stripes above measure, in prisons more frequent, in deaths oft. Of the Jews five times received I forty stripes, save one. Thrice was I beaten with rods, once was I stoned, thrice I suffered shipwreck, a night and a day I have been in the deep, in journeying often, in perils of water, in perils of robbers, in perils by mine own countrymen, in perils by the heathen, in perils in the city, in perils in the wilderness, in perils in the sea, in perils among false brethren; in weariness and painfulness, in watchings often, in hunger and thirst, in fastings often, in cold and nakedness.”

And yet amidst all their arduous labours, their severe trials and sufferings, we see the apostles were comfortably supported, and went on cheerfully in the work, in which they were engaged, notwithstanding all the ungrateful abuses, reproaches and ill treatment they met with from the world. They had no worldly honours, or secular advantages in view; no inviting prospects of an earthly nature to invite and animate them. It is therefore evident, they must have had supernatural assistance and support, which not only kept up their courage and resolution, but raised them superior to all difficulties, and made them even rejoice in tribulations. One important article of this divine support the apostle mentions in the text: For our rejoicing is this, the testimony of our conscience, that in simplicity and godly sincerity, &c. an inward consciousness of our integrity in the sight of God, with a confident reliance on his promise for success, and the glorious rewards of another world to crown our labours. The words suggest this doctrine:–

Doc. That the testimony of conscience in our favour is the most solid foundation of rejoicing under all circumstances in life.

The explanation of the text, if it needs any, will naturally come in, while we consider—What the testimony of conscience is:–What is requisite to its being in our favour:–And why it is the most solid foundation of rejoicing under all circumstances in life.

I. We may consider, what this testimony of conscience is:–Conscience, considered as a faculty, is nothing but our reason exercised in judging of the lawfulness or unlawfulness of our actions, compared with the divine law, the rule of duty. By this reason, which God hath given us, we judge of the truth and evidences of divine revelation, and search out the meaning of it. By this, under the assistance of the Holy Spirit, we examine into the nature, the tenour, and conditions of the gospel, the requirements of it, and the terms of salvation therein revealed. This is necessarily supposed in all the commands and directions given us, to search the scriptures:–To examine, try and prove ourselves, whether we be in the faith?—Whether we be the sons of God, or the children of disobedience. This supposes us able to understand the rule of trial, and to have a capacity of comparing ourselves, or our true character, in order to judge of our conformity to the rule.

Accordingly we find, that we have an immediate consciousness of what passes within us: Not only what our actions are; but what our dispositions, views and governing motives to action. The testimony of conscience then is the inward witness of our spirit to the sincerity and uprightness of our hearts before God, when compared with his laws, and the qualifications necessary to salvation required in the gospel. The testimony of conscience is that reflex act of the mind whereby we judge of the moral goodness or evil of our actions and dispositions, or of the goodness of our state, according to the prescribed rule of judging. Agreeable hereto the apostle says of the heathen,– 4 “Their conscience also bearing witness, and their thoughts the mean while either accusing, or else excusing one another.” And elsewhere,– 5 “if our heart condemn us not, then have we confidence towards God.” We read in scripture of a good conscience, and of an evil conscience. The latter intends a guilty, accusing conscience; the former means directly the reverse of this. The apostle in the text intends the testimony of a good conscience, as this only can be a just foundation for rejoicing. We are likewise to understand him to mean a well-regulated, and duly enlightened conscience: For although the testimony of an erroneous conscience in our favour will necessarily be attended with joy; yet this is only the joy of the hypocrite, that will perish.—Such a misguided conscience is so far from being a just and solid foundation for rejoicing, that ‘tis one of the most awful judgments.

In a word, the testimony of conscience intended in the text, is the inward approbation and witness of our heart, that we have sincerely complied with the offers of the gospel; have truly devoted ourselves to God and his service through Jesus Christ; and in consequence hereof do habitually and prevailingly endeavour to have our whole conversation such as becomes the gospel, in simplicity and godly sincerity.

But do not many enjoy the pleasure of this self-approbation, while in truth and reality they have no solid foundation for rejoicing? Does not the ignorant, conceited Deist feel very comfortably elated in thinking, that by a superior greatness of genius and rare discernment, he has been enabled to soar above he vulgar errors and prejudices of those weak souls, who perceive their need of a revelation from the Father of Lights; and are hence induced to believe, “that God at sundry times, and in divers manners spake to the fathers by the prophets, and to us in these last days by his Son;” and so are credulous enough to believe the bible to be the word of God? while he is conscious to himself that he hath most uprightly followed that sure unerring guide, the dictates of human reason, not only in those social virtues, which he may have occasionally practiced; but also in those more manly freedoms, which the contracted Decalogue unpolitely forbids?

Does not the self-righteous legalist feel extremely satisfied to think he hath been so upright, so sincere, practiced so many virtues, done so many good deeds to mankind, and performed so many acts of piety and devotion towards God, that he cannot imagine the best of beings will be so severely incomplaisant, as to mark against him the few slips and sins he may have been guilty of through inadvertency, or some unhappy inclination of nature?

Does not the affectedly humble, but really proud enthusiast exult with exceeding joy, while he pleasingly fancies himself indulged in the greatest familiarities with the Supreme Being, as one of his most distinguished favourites;–is caught up into the third heavens in the multiplicity of his revelations, and seems to hear from the throne of the Majesty on high such transporting declarations as these, in the very language of scripture,–“O, man, greatly beloved of God:–Son, be of good cheer, thy sins are forgiven thee?”—No doubt these and many other instances of groundless, delusive joy do, and will, take place in the hearts of men, notwithstanding the clearest external teachings and instructions heaven can give. Nor can we rely on anything, but sovereign grace, to secure us from being the unhappy subjects of these fatal delusions. The consideration of which may very justly excite us to have our eyes to the Father of Lights to direct us in judging impartially of ourselves, and in making a due application of the truth, while we consider,

II. What is really requisite to the testimony of conscience being in our favour. It is very plain, negatively, that it is not requisite, that it should bear testimony to our perfect innocence. This is impossible in this state of sin and great imperfection. The conscience of the holiest saint on earth must testify against him, that he hath sinned and come short of the glory of God: That he is in himself a guilty sinner; and that if God should mark iniquity against him, he could not stand:–That he hath been greatly deficient in every duty, and chargeable with continual criminal imperfections in all the holiest services he hath ever performed. The apostle very freely acknowledged he had not already attained what he was aiming at, neither was yet perfect; so that when he had a prevailing disposition to do good, evil was still present with him. Under a deep, affecting sense of this he sighed forth that heavy complaint, O wretched man that I am!

But then the apostle tells us positively, in the text, what was the matter or substance of the testimony which conscience bore in their favour, viz. that in simplicity and godly sincerity they had their conversation in the world.

Now the truth and reality of this is the grand requisite to conscience bearing testimony for us, so that it may be a just and solid foundation of rejoicing to us. I will therefore only briefly consider, what is necessarily comprised in this testimony, as

I. A consciousness that we have sincerely devoted and dedicated ourselves to God through Christ, according to the call and demand of the gospel.

Our hearts must testify this, that we have truly given ourselves up to the Lord and his service, with an hearty desire of glorifying him in such business and employments as Providence shall point out to be our duty. That we have at least a prevailing hope of what the apostle was so well assured of respecting himself, when he says, “I know whom I have believed.” Conscience must give some comfortable evidence to us, that we have really complied with the call of the gospel, have received, and humbly submitted to Christ, as our king to reign over us, as his willing and loyal subjects.

II. That we have faithfully endeavoured to do the work and business which he hath assigned us.

Let our calling be what it will, faithful, vigorous activity and diligence therein is our indispensable duty. And if we do not labour industriously in the service of our Lord, instead of having the testimony of conscience in our favour, it will condemn us, as wicked and slothful servants. If we be called to the sacred work of the ministry, we must “do the work of an Evangelist.” Assiduous labour and vigilance, and that not of the easiest kind, is most plainly assigned to ministers of the gospel. This is evidently required in their character of labourers and soldiers &c. and it is needless to mention how repeatedly and solemnly this is enjoined upon them in the word of God, or to enumerate the various articles of service and labour allotted to them. Nor can slothfulness and idleness in any case be followed with more fatally dreadful consequences than in this. Most applicable to this is what was said by the prophet concerning another work, 6“cursed be he that doth the work of the Lord deceitfully.” How frequently do we find this apostle making mention of his, and his fellow-labourers striving and laboring, even night and day with the greatest ardour and diligence in the work of the ministry? 7 “Whom we preach (meaning Christ) warning every man, and teaching every man, in all wisdom, that we may present every man perfect in Christ Jesus. Whereunto I also labour, striving according to his working, which worketh in me mightily.” The apostles being able to make these and such-like declarations with truth, was what laid a solid foundation for his rejoicing: And we must be able to say the same, if we would share in, and be partakers of that noble joy.

III. A consciousness that we have been incited and influenced by a right principle of action in our conversation.

By the principle of action here I would be understood to mean that temper of mind, or disposition of foul, whereby a person hath been inclined to that course of actions which he hath performed in the world. ‘Tis exceeding manifest, that persons may be influenced to the same visible conduct, or materially good actions from very different springs or principles at heart. The apostle therefore observes, in the text, that their conscience bore testimony with regard to this, that their conversation in the world had proceeded from a principle of godly sincerity, or the grace of God, in opposition to fleshly or carnal wisdom. They had been powerfully inclined to devote themselves to the service of God in the gospel-ministry by the grace of God ruling in their hearts.

If we be induced to action merely from a natural principle of self-love, without a supreme regard for God, his honour and glory, we have not that godly sincerity mentioned in the text. The apostle could say, “We preach not ourselves, but Christ Jesus the Lord; and ourselves your servants for Jesus’ sake.” He may be justly considered as explaining what he means by the grace of God, or godly sincerity in the test, where he tells us in this same epistle, “That the love of Christ constrained them” to their ministerial labours. It was by a supernatural principle of divine grace implanted in their hearts by the spirit of God, that they were irresistibly borne along and carried forward in the service of God; so that while this reigned in their hearts, no obstacles could stop them in their course.

Natural sincerity is, when a person acts from the impulse of mere natural principles, or a regard merely to self-interest, in what he does. Godly sincerity is, when the love of God bears sway, as the ruling spring of action in the soul.

The apostle elsewhere speaks of the wisdom of the flesh, and the wisdom of the spirit; and of that wisdom which is from above, and that which is from beneath, as different or opposite principles of action. And the testimony of conscience can be of no avail to us, unless it witnesses by an inward consciousness, that we are actuated by the wisdom of the spirit, or by a gracious disposition wrought in our hearts by the spirit of God.

IV. That we have fixed upon, aimed at, and pursued a right end in what we have done in the world.

This hath an essential influence in determining the quality of our actions. If our highest, ultimate end be wrong, our conduct, completely viewed, cannot be right, or meet with the divine approbation. Could we suppose the apostles to have been inspired, and have performed all their extraordinary labours and services for any lower end, than the honour and glory of God, the testimony of their conscience would have been essentially defective. But their conscience witnessed for them, that they had behaved with simplicity in the world: That their grand, governing end and design was such, as was naturally indicated by their actions. “Their eye was single.” The word simplicity, in the original, seems to be nearly of the same signification with sincerity. It denotes an uprightness of intention and design, in opposition to hypocrisy, or acting under a disguise: In which case a person’s real end is different from that which he professes, or makes a shew of: When his profession or actions naturally indicate a certain end to be aimed at by him, while he really hath a different one in view. The meaning of the word simplicity, above-given, is agreeable to the etymology of it, and the sense in which it is frequently used in the new testament, as in Romans xii. 8. “Let him that giveth, do it with simplicity;” with an upright intention, and not with any such low, selfish end, as that of being seen of men. Eph. vi. 5. “Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with singleness of heart, as unto Christ.” The apostles plainly professed, both by words and actions, that they aimed not at any thing this world could bestow, but at the highest and noblest end in the extraordinary services they undertook. This was the tenour of their declarations: “We seek not yours, but you.”-—“For whether we be beside ourselves, it is to God; or whether we be sober it is for your cause.”-—“For we which live are always delivered unto death for Jesus’ sake.” 8 “Therefore I take pleasure in infirmities, in reproaches, in necessities, in persecutions, in distresses for Christ’s sake.” This being their profession, they must have had an ultimate view to God and his glory, and a disinterested regard to the good of mankind, in order to support the truth of this testimony, that they had their conversation in simplicity. Godly sincerity requires and implies a supreme regard to God as our last end. 9 “For whether we live, we live unto the Lord, or whether we die, we die unto the Lord.” Whatever regard we may lawfully have for our own honour, ease or interest, these must not be uppermost in the view of our minds; but all subordinated to God, and his honour. This is a most material thing, when we come to view ourselves in the sight of God, and under his omniscient eye, who searcheth the heart, and most perfectly views all the springs of action in us, all our motives and designs. It is plainly of the last importance, that a well regulated conscience be able to testify to our sincerity in this respect.

I am not insensible how difficult it is for us, in this imperfect state of blindness and self-partiality, clearly to know our deceitful hearts in this matter, nor of the danger we are in of drawing up a wrong judgment in our own favour, which should make us exercise the greatest care and caution, while we examine ourselves by attending to the workings of our hearts, and comparing them with the tenour and habitual course of our conduct, enquiring what we are enabled to do for God, and how far we can readily deny ourselves for his sake, and give up, and sacrifice our interest to his honour and interest. And yet I am fully persuaded, that those, whose hearts are right with God, and found in his statutes; who daily exercise themselves to keep consciences void of offence towards God and towards man, may, by due attention and careful self-examination, upon solid evidence, obtain a comfortable, satisfactory testimony of conscience in their favour, and be able to appeal to God, with humble modesty, “Thou knowest that I am not wicked,” i.e. allowedly so.

V. That we have, according to the best of our knowledge and skill, used the proper means for attaining this best end. Conscience must be able to testify, that we have not regulated our conversation by the principles and maxims of fleshly wisdom. Fleshly wisdom is that craft or policy whereby the men of this world govern their conduct in order to attain their ends. And as they are prevailingly determined by a regard to their own gratification, they will not ordinarily stick at the greatest unlawfulness of the means they use, provided they can judge them most subservient and conducive to their purpose.

This was not the manner of the apostles conduct: Nor did they govern themselves by these rules of prudence. They were harmless and blameless, as the sons of God, without rebuke: Yet very far from being supinely inactive. They were vigilant and attentive; sagacious to espy dangers, cautious not to create them needlessly, and wary to escape them. Their prudence consisted much in giving no just occasion of offence to Jew or Gentile: In performing every innocently-winning office of goodness and condescension, without meanly seeking applause of men. They were discrete and wise: But then their wisdom was not only consistent with, but greatly consisted in, the innocence of the dove. They were harmless as sheep in the midst of wolves;–yet not cowardly timorous.—They were bold as lions, when the honour of God and the Redeemer, the cause of truth and pure religion was endangered: Nor did they, when called to action, shun to expose themselves to the most formidable dangers in defence of it. They would not comply with an unlawful measure, to conciliate the favour of monarchs and the whole world, or extricate themselves out of the greatest difficulties and dangers. They would not neglect a plain, known duty, or shun to declare the whole counsel of God, even the most obnoxious, offensive truths, that were profitable, and that before kings, in order to avoid the severest persecution. For it was their governing maxim, to obey God rather than man, when their commands clashed with each other. When the Holy Ghost assured them, that bonds and imprisonments awaited them in every city, and the affectionate, kind entreaties of Christian friends urged them hard not to expose themselves to the threatened dangers, though they could not indeed be unaffected with the expressions of their kindness, they felt it deeply, almost to the breaking of their hearts; but still a deeper sense of duty and obligation to their divine Redeemer supported their resolution undaunted, as we have it expressed with inimitable beauty, and the liveliest sensibility in such language as this, “What mean ye to weep and break my heart? For I am ready not only to be bound, but also to die at Jerusalem for the name of the Lord Jesus.”

There was a just and noble simplicity in their conduct in this respect; that they would not descend to mingle carnal measures, and crafty devices of their own invention, with the means which God had directed them to use. They kept strait and close to the line of truth. Thus they express themselves; 10 “We can do nothing against the truth, but for the truth.”-—“We have not followed cunningly devised fables, when we made known unto you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.” They had no party to espouse, besides that which Christ had made himself the head of, who came to bear witness to the truth. They had no little party designs or interest to serve; were not therefore necessitated to deal in ecclesiastical intrigues and politics. 11 “They renounced the hidden things of dishonesty; not walking in craftiness, nor handling the word of God deceitfully; but by manifestation of the truth commending themselves to every man’s conscience in the fight of God.” They were not indifferent about the great distinguishing truths of the gospel; nor did their Catholicism consist in (what some have since valued themselves upon) regarding the treating almost all the doctrines of the gospel, as indifferent points of speculation. They boldly and fairly oppose all false religion, and all corruptions of the Christian doctrine by blending error with the truth. This condescending apostle, who was willing to become all things to all men, in matters of mere indifference, did not scruple to anathematize an angel from heaven, that should dare to advance any other, i.e. contrary, doctrine to what he had preached, as knowing that he had received his from the unerring spirit of truth. 12 Those who advanced pernicious errors in doctrine, subversive of, or highly prejudicial to, the gospel-scheme and plan of salvation, or favouring licentious practices, they openly and boldly declared to be enemies to the cross of Christ. But then they practiced no little fly craft, no low, under-hand measures to blacken the character of their enemies needlessly.—They willingly left the honour of such low dealing to their enemies, who did not fail to practice it very freely, as many since have done, who will scarcely allow common sense to those who differ a little from them in some immaterial points, not unfrequently characterizing them for fools and dunces. Or if they oppose any of their peculiar, darling whims, or more hurtful errors, they will be sure, either by fly insinuations, or confident majesterial assertions, to endeavour to stigmatize them with the frightful, ambiguous name of heretics, or the still more unmeaning epithet of contracted bigots. I know it is good to be zealously affected always in a good thing; nor is it surely any evidence of meanness or malevolence to contend earnestly for the faith once delivered to the saints with the meekness of wisdom, and with that zealous boldness, which the high importance of sacred truth justly requires, in opposition to all those adversaries, who endeavour to corrupt or pervert the gospel of Christ. All that I mean to condemn is, the using sly, crafty, ill natured artifices in support of what we deem to be the cause of Christ, which cause always disdains such ill chosen and unfriendly assistance. It rests securely on the open, honest evidence of truth: It never deigns to call in, or ever thinks it can be served by, any aid that wickedness can afford it. It may not be improper to observe here, those who are engaged on the side of error are by much the most likely, in their straits, to have recourse to such an impolitic, wicked refuge, like Saul to the witch of Endor, when God had departed from him.

All these practices are intirely inconsistent with that simplicity and godly sincerity, on which the apostles justly valued themselves.

However good therefore our cause may be, we must be ware that we do not take undue methods for the support of it; but trust it with God, in the use of those means which he hath prescribed. The cause of God, in which the salvation of souls is concerned, may not, cannot be maintained or served by craft, carnal policy, or any measures not consistent with the strictest truth, justice and goodness. And if by a close, prudent adherence to these we cannot obtain the desired success, or accomplish what we sincerely aimed at, yet we shall have the testimony of a good conscience, if it witness for us, that we have used all lawful and proper means for attaining the end. Not the greatness of success; but the sincerity of our intentions, and the suitableness of the measures used are the grand articles requisite to be attested by conscience.

III. I proceed to consider why or how this testimony of conscience is the most solid foundation of rejoicing under all circumstances of life.

Not because it implies, that we have done the whole of our duty. No, there will still be an humbling consciousness of many criminal defects and neglects of duty, which will effectually exclude all boasting or glorying in ourselves, under any such notion as this, that we have hereby in the least merited the favour or approbation of God. A deep sense of guilt will stop the mouth, and lay the holiest saint on earth low before God. His rejoicing therefore will not be in himself, but in the Lord, in his sovereign abounding mercy through Christ. And yet this testimony of conscience will afford as many just reasons for rejoicing, as,

I. That we have in any good measure, or only in some small degree acted up to our character and obligations.

Our being entirely indebted to rich grace, for any good we may have been enabled to do, doth not at all exclude a real, just self-approbation, wherein we have in any measure complied with the will of God, and performed our duty. Perfectly consistent are these several declarations of this great apostle Paul;–“By the grace of God I am, what I am.—I labored more abundantly than they all; yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me.” And yet this is my rejoicing, the testimony of my conscience, that in simplicity and godly sincerity, &c. I have had my conversation in the world.”

While we ascribe to God the whole praise of whatever good he hath been pleased to bestow upon us, or enabled us by his grace to do, there is just room to feel a humble, self-complacency in being what God hath made us, although the more we are enabled to do for him, and act up to our character, the more we are indebted to him.

II. ‘Tis just cause of rejoicing, that we have been instrumental of doing any good to mankind.

It is an high honour to be faithful servants to our generation.

The apostle Paul magnified his office, while at the same time he declared himself a debtor to the Greeks and Barbarians, to the wise and the unwise:–And that a necessity was laid upon him to preach the gospel. “It is more blessed to give than to receive;” to communicate good to others, than to receive it from them, however indisposed our selfish hearts may be to relish this blessedness. The ever blessed God delights in thus communicating good: And an imitation of him herein affords a pleasing gratification to a benevolent heart, and yields the soul a sublime, refined joy and pleasure. If we have the same mind in us, which was also in Christ; if we have that law of kindness written on our hearts, requiring and disposing us to love our neighbour as ourselves, we cannot fail of feeling a sensible joy in the thought of having contributed to the promoting their happiness.

III. This testimony of conscience is just cause of rejoicing, as it assures us of our having been designed active in advancing the glory of God and the Redeemer.

The infinite blessedness of God renders it impossible for us to be really profitable to him; yet we may be said in some proper sense to honour and glorify him by serving him: And he condescends to represent himself as honoured by the willing, faithful services of his creatures. It is, it will forever be, the inseparable effect of love to make us rejoice and take delight in pleasing and honouring the object of it. Gratitude for the infinite blessings of redemption by Christ will necessarily make the creature’s heart rejoice in thinking he hath contributed his mite in displaying the honour of the Redeemer, and the glory of God’s grace:–That he hath herein been a worker together with God; and is unto him a sweet savour of Christ in them that are saved, and in them that perish.

IV. As it furnishes us with a comfortable refutation of the reproaches and calumnies that may be cast upon us.

To be suspected, vilified and reproached, and injuriously robbed of that good name, which is as precious ointment, hath something in it very painfully grating to human nature. There is likewise something tenderly affecting in the thought of the injuriousness of this conduct, especially when it springs from, and has base ingratitude mingled with it. Innocence however, like a brazen wall of defence, affords a comfortable shelter, a mighty support under such attacks of ignorance or malice; enables the soul to rise superior to them, and to esteem it comparatively a little thing to be judged by man’s judgment, while he can appeal to the Searcher of Hearts, as the Judge of his integrity, assured that he will bring forth his judgment as the light, and his righteousness as the noon-day.

But just reproaches, the echo of the voice of conscience, sting and cut to the quick, when they come keenly edged with conscious guilt; which will often be our mortifying situation, if we have not the testimony of conscience to our simplicity and godly sincerity.

But a well-grounded testimony of conscience in our favour appears a matter of still infinitely greater importance, when we consider it.

V. In connection with the divine approbation, and as giving assurance of final acceptance with him.

In this view of it the mind cannot conceive of any equally just foundation for rejoicing. This makes heaven:–This must give joy unspeakable and full of glory.—Let us pause a moment, my brethren, and consider what an importantly critical situation we are in this moment, while probationers for eternity, I mean in this life, which is but a moment. We stand, as it were, in the middle between Heaven and Hell, this moment of life determines the event, and consigns us over to the one or the other for eternity. The favour and approbation of the Almighty is life and endless felicity: His frowns and displeasure are death and hell. Imagination cannot suggest any real good, any thing possibly desirable for us, but it is all fully comprehended in final acceptance with God.—When therefore we anticipate in our thoughts the decisive sentence to be very shortly given from the tribunal of Christ, with assurance from the testimony of conscience, that we shall be able in that solemn day to give up our account with joy and not with grief, it is impossible not to feel ourselves supported by the most solid foundation of rejoicing, a foundation as firm and solid, as the immutable rock of ages. The rejoicing that can spring from any other consideration, of riches, honour, and all the enjoyments of time and sense, will bear no more comparison with this, than a moment’s laughter of the fool with the endless, ever-fresh, unsatiating joys of Paradise, and those deep rivers of pleasure, which flow perpetual at God’s right hand. With the utmost reason then did the apostles make this the matter of their rejoicing, even a consciousness of their simplicity and godly sincerity.

The present state, though very wisely calculated for a state of probation, is far from yielding uninterrupted joy and pleasure. We cannot travel long on earth, under the most promising circumstances, before we shall descend into some Bokim, a vale of tears; and very often are but just ascended from one to higher ground and fairer prospects, before we are obliged to descend again into another, which we must wade through in grief and sorrow, with the wearisome, lonely steps of pilgrims. Under these dark, solitary scenes, when the joy of our heart is ceased; when the fig-tree blossoms not, nor creation wears a smile, to what shall we betake ourselves for rest and consolation? The whole creation cannot give it.—Happy then, if we can find solid cause of rejoicing in the testimony of our conscience: This will give peace and joy; not as the world giveth: Will enable us to rejoice in the Lord, and joy in the God of our salvation, yea, even to rejoice in tribulations. Or, if we suppose the best that possibly can be supposed relative to the present state, that we may live many days and rejoice in them all; yet let us remember the days of darkness, for they will be many. All that cometh is vanity. For what is our life! It is even a transient vapour, which appeareth a little while, and then vanisheth away. When therefore our declining sun is just setting, and we are got into the dusky, lonely evening of life; or when any other indubitable symptoms declare death to be just entering our doors, to what shall we then have recourse for support or consolation? Will all the past pleasures or enjoyments of the world afford us any relief? ‘Tis impossible; for they are annihilated;–they are not. Will any future expectations from earth come in to our aid, when we shall stand in the most pressing need of it? Alas! we cannot reach them: They are absolutely cut off by the supposition, and flee away before us. Will the kindest assistance of friends be of any avail to us? No; we are in the very article of biding a lasting adieu to them, our dying hands withdrawing from theirs. Nothing therefore will be able to administer any relief, or solid rejoicing, or even tolerable support, but that testimony of conscience which assures us of the divine favour, “That when our heart and strength shall fail, God will be the strength of our heart, and our portion for ever.”

At these solemn seasons, and indeed through the whole of life, this testimony of conscience will be of infinite importance to all, whatever their rank, condition or employment may be. But when we consider the words of our text, as coming from the mouth of a minister of Jesus Christ, under inspiration, with a particular application to himself and his brethren in the ministry, they seem in a special manner to demand the most serious attention of those who sustain that sacred character.

Permit me then, my reverend fathers and brethren in the ministry, with all humility and freedom, to address to you and to myself the hints that have been offered on the subject.

Such a solemnity as this before us cannot but impress our minds afresh with a sense of the very sacred obligations we laid ourselves under to God, when we devoted ourselves to his service in the gospel ministry. And it highly concerns us at such a time to review our past conduct with the strictest impartiality, as in the awful presence of him who searches our hearts, and enquire how we have acted up to these obligations: And to enter into ourselves, and examine, whether conscience testifies for us, that in simplicity and godly sincerity, not with fleshly wisdom, but by the grace of God, we have hitherto had our conversation in the world?—Have our prevailing motives and principles of action been such, as will meet with the divine approbation?—Have we made God, his interest and glory, the highest end of our ministerial labours, while at the same time we have been prompted and constrained to faithfulness by a benevolent solicitude for the souls committed to our charge?

For our quickening to industry and diligence in the work of the Lord, let us consider, that we may well afford to be active and laborious therein. We have not such an hard, trying service, in many respects, assigned to us, as was laid on the apostles and primitive ministers of Christ. Instead of the want of all things, hunger and nakedness, which they were called to endure, we are comfortably supported, have a competency, if not an affluence, of worldly good. Instead of that infamy, reproach and contempt, with which they were loaded, we are kindly treated with all the esteem and honour we deserve (and sometimes more) by the world around us, except some few profligate sons of Belial, in whose power it is not to honour us so much any other way, as by their spiteful reproaches, thereby giving a lively specimen of the ancient enmity put between the woman’s seed and the seed of the serpent: At the same time they treat us full as respectfully as they do their Maker. It must then be most criminal ingratitude in us to be slothful in our business, while we are serving the Lord, who hath made our work so much easier than was that of the apostles. Not but that we have toil and labour enough, with many sinking discouragements, and exercising scenes to pass through, in the faithful discharge of our trust. But let none of these things move us, any otherwise than only to animate us to labour and strive, that we may obtain the rejoicing testimony of conscience. And let us daily bear in mind the solemn, closing scene, when we must give up an account of our stewardship, and be no longer stewards; when our departure shall be at hand, and we shall be ready to be offered up. When it shall be at hand, did I say? It is at hand now, even with the youngest of us; for the time is short. And with respect to some of us the shadows of evening, already arrived, are extended long from the hoary head, and remind us, that our sun is just setting. May we all be faithful to the death; and while we live, have the testimony of our conscience for our rejoicing, as a sure earnest of a crown of glory to be bestowed upon us at the last day.

But I must briefly address myself more particularly to this our younger brother, who is now to be solemnly set apart to the work and service of the sanctuary.

Dear Sir,

The solemn hour is now come, in which you are publicly to devote yourself, and be consecrated, to the noble, arduous work of the gospel-ministry, and take upon yourself one of the weightiest trusts ever committed to a mortal. You are about to inlist under the Captain of our salvation, as a fellow-soldier with the apostles, a fellow-servant with angels, who are ministering spirits to the church; yea, as a worker together with God himself, for the grand purpose of accomplishing the designs of redeeming mercy towards your fellow-sinners. Doth not the weight of the charge make your heart tremble, and constrain you to look up by faith and fervent prayer to God through Christ for that grace, which alone can make you an able and faithful minister of the new testament? Both duty and affection incline me to say a few words to you on this solemn, joyful occasion. I trust you have weighed well the importance of your undertaking, and often seriously considered the great necessity of those being truly and experimentally religious, whose business and profession engages them to spend their lives in making others so. let it then be your first care to save your own soul: Then will you be the more likely to save the souls of them that hear you. May this affecting thought daily engage your attention to the concerns of your soul, and quicken you to walk humbly and closely with God. The agreeable, intimate acquaintance I have had with you, while you faithfully discharged the office of a tutor in our college for several years to its great advantage, and with equal reputation to yourself, gives me the pleasure of knowing both your natural and acquired accomplishments for the work you are engaging in, as well as your soundness in the faith. Hold fast that form of sound words, which you have learned from the sacred oracles, and which (may I not say) you have in part heard of me. Practice all that condescension to the weakness and prejudices of others, which the apostle intended by becoming all things to all men. Be gentle towards all men. To which I know your natural disposition is very inclinable. But then be on your guard, lest a condescending and pacific temper at any time betray you into compliances, injurious to your virtue and dishonourable to your profession. Set down your foot at the line of truth, and let not fear, frowns, flatteries or reproaches, or any temporal inconveniencies whatever, make you swerve an hair’s-breadth from it. Condescendingly sacrifice any thing for the sake of peace, except truth and duty: But invariably keep to these. In all your instructions study to be plain and intelligible, which is the prime end of language. And let not your taste for elegance of stile, accuracy of diction and composition, by any means prevent the most plain, close and pungent application to the hearts and consciences of your hearers. Study infinitely more to recommend Christ and his religion to your hearers, than yourself. Keep the great end of the gospel-ministry always in view, the advancing the glory of God and Christ in the salvation of souls committed to your charge. Let me just intreat you to pay a particular attention to the youths and children, and those under serious, religious impressions in your congregation, as having the greatest prospect of success with these: And herein imitate the great Shepherd of the sheep, “who carries the lambs in his arms, and gently leadeth those that are with young.” I cannot now suggest to you the numerous, weighty motives, that might be urged to excite you to the greatest faithfulness and diligence in discharging the high rust you are now to have committed to you. I trust you will daily bear in mind the vast importance to yourself, as well as others, of being able to adopt, with application to yourself, through the course of your ministry, and especially at the close of it, the declaration of the apostle in the text. May you experimentally know the solid rejoicing, which this testimony will not fail to give all those who are faithful to the death; and may you than receive the promised crown.

Let me now say a few words to the church and congregation, at whose call and request a minister is now to be ordained over them in the Lord.

Beloved Brethren,

My unacquaintedness with your particular circumstances will excuse me with only saying a few words to express our joy and congratulation with you in having been directed to, and succeeded in, your unanimous choice of one to be your pastor, who, we have reason to hope, will be an able and faithful minister of the new-testament among you, and naturally care for the welfare of your souls. We desire to join with you in thankful acknowledgments to the great Shepherd and Head of the church, for the provision he is making from time to time for the edification of the same, by raising up and qualifying men to feed his sheep and his lambs, the flock which he hath purchased with his own blood. And that you have this day the experience of this his kind care for you, in providing one to take the oversight, and act the part of a bishop towards your souls; in consequence of which you are like to enjoy the ministry of the gospel and the administrations of its ordinances resettled among you; and that under prospects very encouraging, and joyfully promising happy success. O let your eyes and fervent prayers be directed this day to the God of all grace for his blessing to accompany these solemn transactions, and render the means of grace provided for you a favour of life unto life to the salvation of all your souls: That you and your pastor may have sweet communion with God and one another, while you dwell here in the house of the Lord, feasting on the rich provisions, with which the gospel abundantly furnishes you. Dear brethren, I trust our hearts all ardently breathe out this wish and prayer, The Lord send you the blessing out of Sion.

I close with a word to this great assembly in general. What doth conscience now testify to you, respecting the manner of your conversation in the world? That it is conducted and regulated in simplicity, godly sincerity, and by the grace of God? Blessed are ye indeed, if this be the case. How thankfully and joyfully may you live; and how cheerfully go on in the ways of the Lord, while you have this for your rejoicing, even the testimony of your conscience; a testimony that carries with it an assurance of the divine approbation and final acceptance with God? But if it be the reverse of this with you, and conscience either be asleep, or pronounce plainly to you, that you have your conversation with fleshly wisdom, and live after the flesh, in the neglect of God and religion, think seriously, with what torturing fears and distressing apprehensions, this conscience, if it be duly enlightened, will distract your guilty souls at the near approach of death, when your next speedy remove must be into eternity, and to the bar of God, who is greater than your conscience, and knoweth all your wickedness. And what an everlasting source of unutterable anguish will its accusations be to you, when it shall be fully awakened to the liveliest sensibility, in the regions of horror and despair, and pour in continual reproaches and self-condemnation upon your souls, like a stream of fire from incensed Omnipotence! O be persuaded now to turn its testimony in your favour, by turning from all your sins unto God through Jesus Christ: Then will it speak peace to you here, as a sure pledge of peace and joy everlasting in the presence and favour of God in the coming world.

The CHARGE, by the Rev. Aaron Brown.

Reverend and Dear SIR,

It having pleased God to lead this church into the unanimous choice of you to be their pastor, and to incline you to accept of their call; we, whose hands are imposed, do in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, and by virtue of authority derived from him, ordain and separate you, Joseph Howe, to the great, important and laborious work of the gospel-ministry; especially committing to your pastoral care and oversight the Christian Society, who usually assemble in this place for public worship.

And in that same all-glorious name, we do now most solemnly charge thee, before God and the elect angels (which are doubtless witnesses of these solemnities) that to the utmost of thy power thou discharge thyself, in all parts of that ministry and trust we are now committing to thee.—Preach the word, and declare the whole counsel of God, that you be pure from the blood of all men; for it is required of ministers, who are stewards of the mysteries of God, that a man be found faithful.—Keep back nothing that may be profitable to this people. Let them know from the word of God, that they are naturally guilty and depraved, that “there is a vast and unspeakable difference between a sinner and a saint,” between those who are in a state of nature and those who are in a state of grace. Testify unto them repentance towards God and faith towards our Lord Jesus. Preach Christ and him crucified, the doctrine of his atonement and satisfaction, justification through faith in his blood, and sanctification by his spirit.

Remember that you are a minister of the gospel of Christ: Let Christianity therefore, and not the subtleties of wit and philosophy, be the grand matter and aim of your discourses.—Be not of those who corrupt the word of God, or handle it deceitfully; but by manifestation of the truth commend yourself to every man’s conscience in the sight of God. Nor speak with the enticing words of man’s wisdom, but in the demonstration of the spirit and of the power. Study more to be profitable, than to be popular,–more to gain the divine approbation, than the applauses of a polite and respectable assembly.

Reprove, rebuke, exhort, with all long suffering and doctrine; and in the discharge of this part of your trust, variously accommodate yourself to the needs and circumstances of every one; instructing the ignorant,–convincing the unconvinced,–reproving the transgressor,–refuting and putting to silence the gain-sayer,–exhorting the indolent and slothful, and comforting the feeble minded.—In a word, like the great and good Shepherd, gather the lambs in your arms, carry them in your bosom, and gently lead those that are with young.

We, moreover, authorize and charge thee to administer to all persons, duly qualified, the sacraments of the new-testament, (baptism and the Lord’s supper) with becoming solemnity, and agreeable to the rules of the gospel.—Feed Christ’s sheep and feed his lambs.

Exercise also that holy discipline with which, as a gospel-minister, you are entrusted; exercise it with fidelity and tenderness; not lording it over God’s heritage, nor doing any thing by partiality.

We likewise commit unto you authority to assist in ordaining others to the sacred office, as you may be called of God thereunto: But lay hands suddenly on no man.

Let no man despise thee, but esteem thee highly in love, for thy works sake: Therefore be thou an example to believers, in word, in conversation, in charity, in spirit, in faith, in purity.—Give attendance to reading, to exhortation and doctrine. Neglect not the gift that is in thee, which is given by the laying on of the hands of the Presbytery. Meditate on these things give thyself wholly to them, that thy profiting may appear unto all.

Pray fervently, constantly for this people, and bless them from time to time in the name of the Lord. Pray also for yourself, that the grace of Christ may be sufficient for you; for who is sufficient for these things?

Finally, and in a word, in all things approve thyself a faithful minister of the new-testament, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed.

Long may you be continued a great blessing to this people, and they a comfort to you. May the blessing of many souls ready to perish, come upon you; and the God of peace, which brought again our Lord Jesus Christ, the great Shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant, make you perfect in every good work to do his will, working in you, that which is well pleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom be glory forever and ever,

The Right Hand of Fellowship, by the Rev. Dr. Chauncy.

Dear Sir,

As you have now been separated to the work of the Gospel ministry, and to the charge of the Christian society who worship God in this place, “by prayer and the laying on of the hands of the Presbytery.” In conformity to the common usage upon these occasions, founded on apostolic example, at the desire of the venerable council present, and in their name, I give you my right hand. and I do it, to signify to you, to this great assembly, and to all the churches in the land, that we esteem you a true minister of Jesus Christ, well furnished for, rightly called to, and regularly instated in, the ministerial office; that we affectionately embrace you, as one who has been solemnly devoted to the service of souls; and that we shall always be in readiness to lend you our help by our prayers, advices, and in all other Christian ways, according to our respective abilities, as you may need, and desire it; especially in things “pertaining to the kingdom of God, and Jesus Christ.” Expecting the same expressions of pious charity from you, as the interest of religion may make them proper.

At the same time we “bow our knee to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies, and God of all grace,” humble and importunately beseeching, that he would adorn you more and more with the gifts and graces of His spirit; that He would animate you to your work, guide and assist you in it, and support and comfort you under all the trials you may be called to meet with in the upright and faithful discharge of it; that he would make you “wise to win souls,” and happily instrumental in “turning many to righteousness;” and that, at “the time of the time,” you may be found among those servants of our Lord Jesus Christ, who shall shine in the kingdom of His Father as “the brightness of the firmament, and as the starts for ever and ever.”

We now salute you, the Christian church, who statedly worship in the Deity in this house; rejoicing with you in that kind Providence, which has given you, with so much unanimity, love, and peace among yourselves, “a pastor (as we trust) after God’s own heart;” one who is well qualified to “feed you with knowledge and understanding.”

Brethren, we own you as members, in common with yourself, of that “one body” of which Christ is “the head;” we profess a cordial regard to you as such; and we promise, that we will cheerfully afford your own assistance, to all the purposes of “spiritual edification;” as we are able, and may be called thereto; expecting and desiring the like office of brotherly love and duty from you.

Finally, we commend both you and your pastor “to God, and to the word of His grace; which is able to build you up, and give you inheritance among the sanctified by faith in Jesus Christ,” to whom be glory in the church, on earth, and in Heaven, both now and throughout all ages.

Endnotes

1. I. Cor. 1. 25.

2. Acts v. 39.

3. Chap. xi. 23-27.

4. Rom. II. 15.

5. 1st John III. 21.

6. Jerem. Xlviii. 10.

7. Col. i. 28, 29.

8. xii. 10.

9. Rom. xiv. 8.

10. 2d Cor. xiii. 8.

11. 2d Cor. iv. 2.

12. Gal. i. 13.