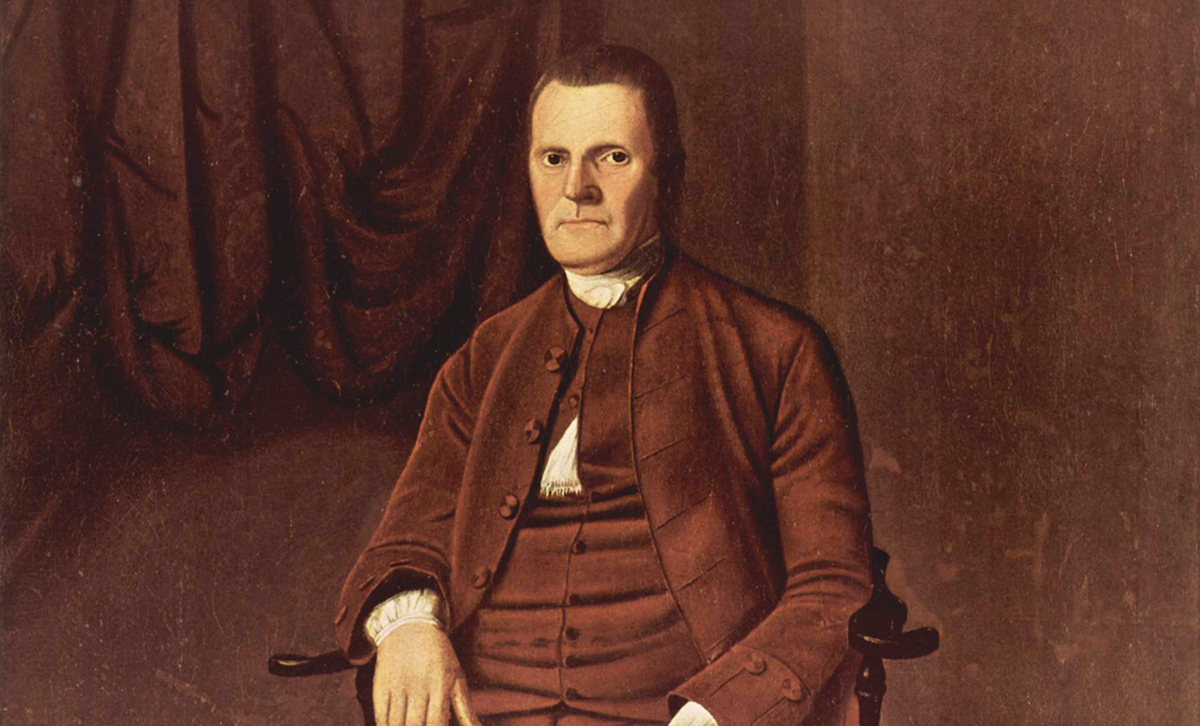

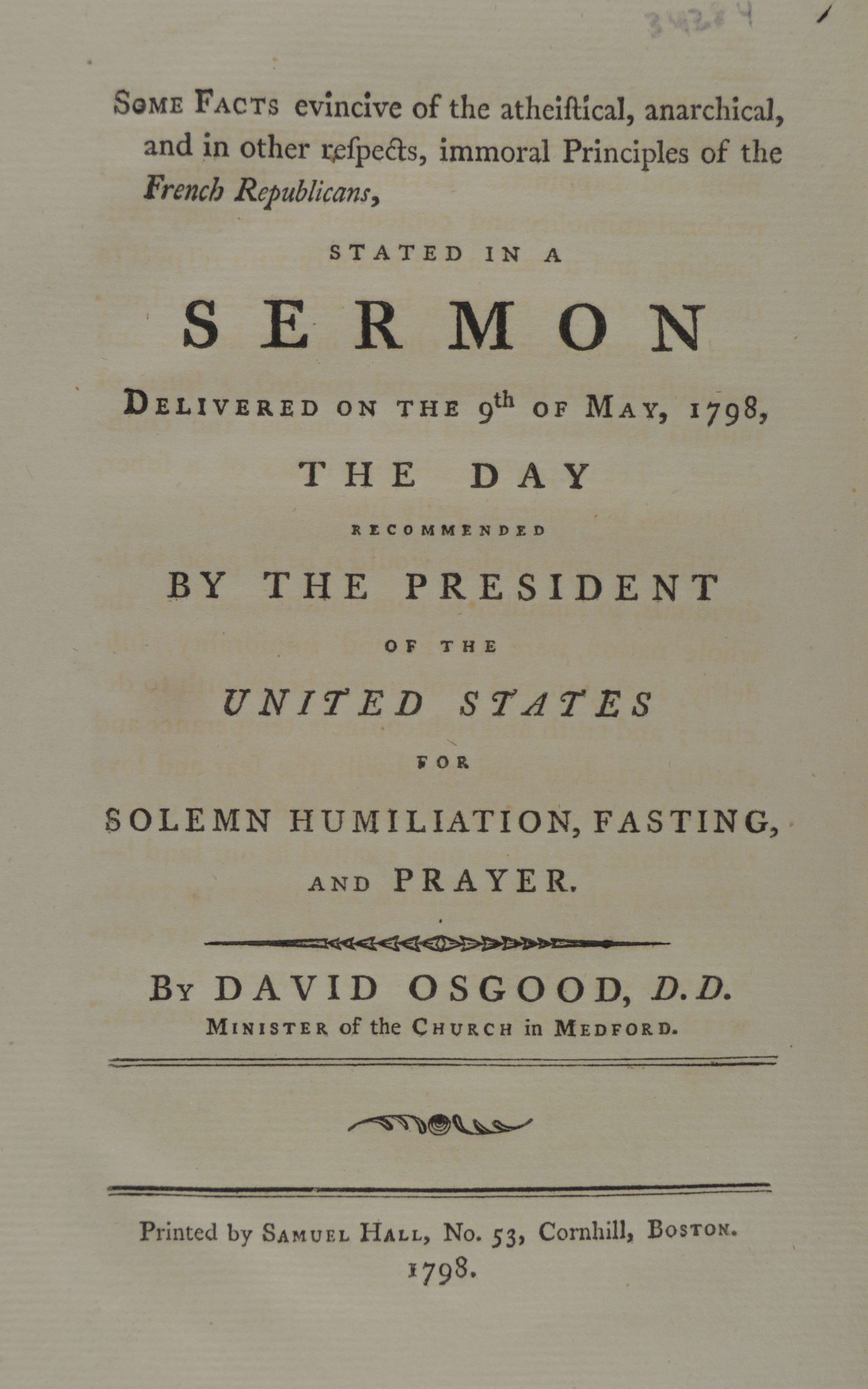

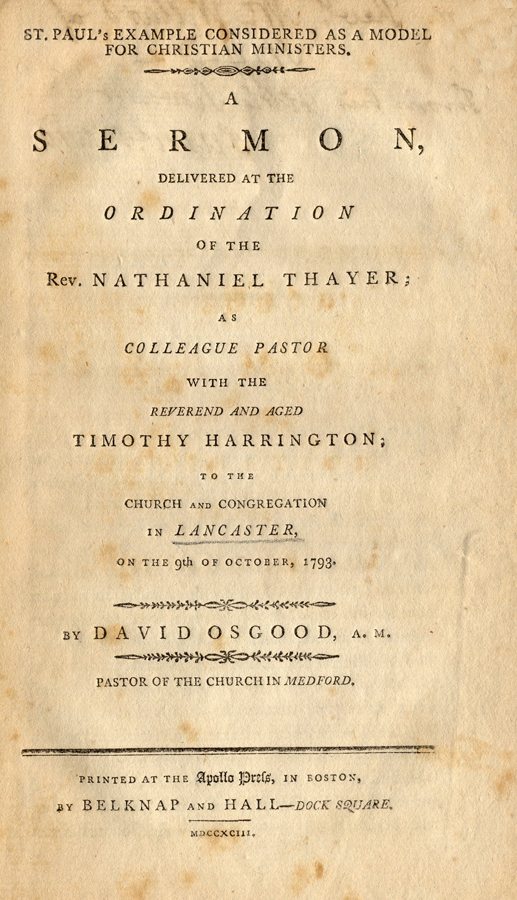

David Osgood (1747-1822) graduated from college in 1771 and spent a year studying theology in Cambridge. He preached in many different places (including Boxford, Charlestown, and Medford – all in Massachusetts) throughout his life. The following sermon was preached by Osgood at the ordination of Nathaniel Thayer in 1793.

FOR CHRISTIAN MINISTERS.

A

S E R M O N

DELIVERED AT THE

O R D I N A T I O N

OF THE

Rev. N A T H A N I E L T H A Y E R;

AS

COLLEAGUE PASTOR

WITH THE

REVEREND AND AGED

T I M O T H Y H A R R I N G T O N;

TO THE

CHURCH AND CONGREGATION

IN LANCASTER,

ON THE 9TH OF OCTOBER, 1793.

BY D A V I D O S G O O D, A. M.

PASTOR OF THE CHURCH IN MEDFORD.

AN

ORDINATION SERMON.

ACTS XX. 27.

I HAVE NOT SHUNNED TO DECLARE UNTO YOU

ALL THE COUNSEL OF GOD.

The discourse with which these words are connected, is most pathetic and affecting. As addressed to Christian ministers, it furnishes directions highly suitable for them in fulfilling their ministry. What the apostles and first preachers of the gospel were, exclusive of their supernatural call and qualifications, all who still succeed them in teaching the religion of Jesus, ought undoubtedly to be. In their example we have a model for the right discharge of the duties of the ministry. Their doctrines, manner of preaching, temper and conduct through the various scenes of their ministry, are recorded, as for the instruction of Christians in general, so for the imitation of ministers in special. And as the labours of Paul abounded beyond those of the other apostles, so his example is exhibited in scripture with a distinguished lustre. After the evangelists, his epistles and the history of his ministry, form the principal part of the writings in the new testament. But in no other single passage, have we so full an account of his ministry, and of the manner of his fulfilling it, as that which he himself gives, in the context, to the elders of Ephesus.

With unwearied pains, and amidst many fears and dangers, he had planted the church of Christ in that city. And being now called away, and obliged to leave the work in other hands, he was anxious for its success, and that it might still flourish, under the fostering care of those to whom it was committed. He therefore called for their attendance, that he might, with his own lips, renew the solemn charge and say, “Take heed unto yourselves, and to all the flock, over which the Holy Ghost hath made you overseers, to feed the church of God, which he hath purchased with his own blood.” To quicken them in keeping this charge, he sets his own example before them in some of its more signal instances during his ministry among them; bringing to their recollection both his preaching and his practice. And having apprized them, that he was now taking his leave of them, and that they would see him no more; on this solemn occasion, he testifies to them, that whatever the issue of his preaching might be with respect to some, whatever melancholy consequences might ensue after his departure, if any of them, or of the people of their charge, should finally miscarry, yet for himself, he was clear from the blood of all men having fully and faithfully delivered the gospel message. For I have not shunned to declare unto you all the counsel of God.

In holding up the apostle’s example as a model for us, we may consider both the subject and the manner of his preaching.

In the first place, the subject, viz. the counsel of God, or the Gospel of his grace, concerted by the divine wisdom, and now, in its most full and complete dispensation, published to the world for the obedience of faith. The whole Christian system is included in that counsel of God which Paul preached. To its peculiar and distinguishing doctrines, however, he did not, upon every occasion, confine his discourses. In addressing the idolatrous Gentiles, he began with asserting the great principles of natural religion, 1 the unity of God, his perfections and universal providence; our relation to him as his creatures, dependence upon him, and consequent obligations to serve him with our mental faculties, in distinction from those bodily exercises which cannot profit. These primary truths of religion, together with those equally obvious ones of morality, of doing justly and loving mercy in our dealings with one another, and walking humbly in the government of ourselves, are that good which God hath shewed unto men in furnishing them with the gift of reason. They are the great law of our nature, coeval with our existence, written upon the hearts of all men, and binding at all times.

Yea, God has so constituted our nature and the frame of things around us, that while reason discerns these fundamentals of religion and morality, experie4nce teaches us how essential to happiness is our conformity to them. Our self-love, the principle of self-preservation, so strong in every one, is made to sanction these dictates of reason, and to urge our compliance with them. And were our reason clear and perfect, unclouded by passion, unbiased by prejudice, unimpaired by disease or intemperance; did it retain its original strength and supremacy over the propensities of nature, it might prove a sufficient guide to virtue and happiness. If it hath totally failed of these ends, the cause lies in its perversion and abuse through the strength of prevailing corruption.

After the apostacy, men became vain in their imaginations; and while they retained some knowledge of God, yet glorified him not as God; but rebelling against reason, gave themselves up to vile affections. These darkened their understandings more and more, and gradually sunk them into deplorable ignorance, superstition and idolatry. Under this mass of rubbish, the light of reason was nearly extinguished, and many ages elapsed, while the moral world lay buried in darkness, gross and heavy, like that which overspread this earth in its chaotic state.

And when, at length, the divine mercy introduced the gospel dispensation for the general benefit of the world, the first object of this revelation was, to recover reason from its degradation, and re-establish the principles of natural religion. This voice from heaven confirms the dictates of reason, restores those which had been lost, enlightens those which had been obscured, strengthens those which had been weakened, and clothes them all with a divine authority; giving to the voice of reason and conscience the commanding energy of the voice of God.

But, were this all that is effected by revelation, (so great is the change made in the condition of man by sin) this which was ordained to life, would be found to be unto death—serving only to show us the extent of our misery. It would be like the appearance of God to our first parents after their transgression, arraigning, convicting and condemning, and then leaving them without the hope which he actually gave in his sentence upon their seducer. By clarifying our reason, and setting before us in its purity and perfection the great law of our nature, revelation enables us to behold the number and aggravations of our sins. “By the law is the knowledge of sin.”

Astonished at the view of his guilt, and alarmed with the apprehension of the divine displeasure, the awakened convinced sinner is anxious to find some mercy to pardon, some kind power to save. He earnestly inquires, by what sacrifices and offerings, or in what way, he may appease an offended Deity, and make satisfaction for breach of his law. Reason cannot answer the inquiry. All nature is silent, and affords no certain ground of hope. The more we think and reason upon our condition, the more helpless and desperate it appears.

These are the real circumstances of all men as under sin and guilty before God. And thus circumstanced, the gospel, in its literal import, as glad tidings of great joy, comes in to our relief. Its glorious peculiarities, the scheme of mediation, the person, character and offices of the Mediator, his propitiation for the sins of the world, and ability to save all who come to God through him, these are our only grounds of hope.

To the inquiry upon what terms this hope may be ours, St. Paul answers when he testifies both to the Jews, and also to the Greeks, repentance toward God, and faith toward our Lord Jesus Christ: A return from iniquity, and cordial submission to him who is made King in Zion, obedience to his precepts, and conformity to his example; these are the requisitions of the gospel; these form the distinguishing character of real Christians.

In attempting these things, however, we find a new difficulty arising. All our moral powers have been weakened in the service of sin, and evil habits have gained such dominion over us, that it is no easy matter to turn the current of our affections from earthly to heavenly things, to mortify the deeds of the body, get free from the bondage of corruption, and recover the lost rectitude of our nature. After some unsuccessful efforts, we should be in danger of giving over the attempt, were we not encouraged to expect aid from above. But so complete is the provision made in the divine counsels for our salvation, that the gospel is the ministration of the Holy Spirit. This divine agent is tendered as the guide of our feeble steps in our return to virtue. We are directed to seek, and encouraged to hope for his assistance on our first honest attempts to reform. “Turn ye at my reproof: Behold, I will pour out my spirit unto you. Ask, and it shall be given; seek and ye shall find; if e being evil, know how to give good gifts unto your children: How much more shall your heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to them that ask him?”

And that nothing proper to quicken our exertions, may be wanting, the sanctions with which the gospel is enforced, are as full and perfect as can be imagined. Its promises and threatenings addressed to our hopes and fears, are so great, solemn and awful, that, when duly considered, they seem sufficient, to overwhelm the mind, and seizing upon all our faculties, to bear us away by an irresistible influence from all other objects of attachment and pursuit, to the great and momentous concerns of eternity.

These things, in their connection with various other particulars in the inspired writings, were those divine counsels which Paul, with such unremitting diligence, declared. Not this account of them however, but the scriptures themselves are to be regarded as the law and the testimony, the oracles of God, in conformity to which every discourse upon religion and Christian morality is to be composed. By the study of these inspired writings, every Christian, and especially every Christian minister is to satisfy himself what are indeed the counsels of God. The studies of a minister principally consist in searching the scriptures. From these he must derive the things new and old with which he is to entertain and edify his hearers. That he may “rightly divine the word of truth,” and approve himself “a workman who needeth not to be ashamed,” it is necessary, that he have a thorough and intimate acquaintance with every part of divine revelation. Its doctrines and duties should be so familiar to this thoughts, that on every occasion his lips may preserve knowledge, drop as the rain and distil as the dew. As set for the defence of the gospel, it is also necessary, that he be so versed in the various and abundant evidence of its truth both internal and external, that he may be ready at all times, to remove the scruples of the yet wavering and unsettled inquirer, answer the objections of infidels, and stop the mouths of gainsayers.

In searching out the meaning of the scriptures, and determining what doctrines they really contain, a knowledge of ancient manners, customs and languages, especially of those languages in which the scriptures were originally written, is highly requisite. Much useful information may be derived from those profane authors who were cotemporary with the inspired writers. With as many of these, as have reached modern times, the interpreter of scripture should be acquainted. He should know what allowance to make for the difference between ancient and modern languages; and for the peculiar phrases, idioms and proverbial sayings of the people for whose use the scriptures were at first designed. In construing those passages which are hard to be understood, he must keep in view the general aim and scope of the writer, and by comparing spiritual things with spiritual, make what is clear and plain to reflect light upon that which is doubtful and obscure.

To the disgrace of all Christendom, it has been the too general practice, to adopt, with little or no inquiry, a set of doctrines as the standard of orthodoxy from some celebrated Father, Reformer, established Church, Synod or Council. And having thus embraced our scheme of divinity, all our studies have been to weave these doctrines into our interpretations of scripture; and detached texts, sentences and phrases have been turned and twisted in every direction to the support and defence of pre-conceived opinions. “Instead of impartially examining the sacred writings with a view of discovering the truth, in whatever shape it may appear, we enter on the inquiry with a system already adopted, and have erected the edifice, even before the ground has been explored, on which it must be reared. It is from this cause, that the Greek and Latin churches have discovered in the new testament their different tenets, and that the most opposite parties, which have arisen in the Christian world, have made the same divine oracles the basis of their respective creeds. It is from this source that the church of Rome derives her seven sacraments, the Divine of the church of England his thirty nine articles, the Lutheran his symbolic books, and the Calvinist his confession of faith.”

To the honour of the present age, a more rational method of treating the scriptures seems to be gaining ground. These shackles upon the minds of men are evidently loosened, and we may hope, will gradually fall off. It begins to be generally acknowledged that “as an historian should be of no party, an interpreter of scripture should be of no sect. His only business is to inquire what the apostles and evangelists themselves intended to express; he must transplant himself, if possible, into their situation, and in the investigation of each controverted point, must examine, whether the sacred writers, circumstanced as they were, could entertain or deliver this or that particular doctrine. This is a piece of justice that we refuse not to profane authors, and no reason can be assigned, why we should refuse it to those who have a still higher title to our regard.”

Having, by diligent and impartial inquiry, settled in his mind what are the doctrines of scripture, the preacher, who would regard Paul as his model, will make these the constant theme of his discourses: And his great concern and study will be, to teach them in their purity and simplicity, and with such persuasive force and energy as if possible to impress a just sense of them upon the minds of his hearers. This he will be most likely to effect, if in the discharge of his ministry, he sets before him,

Secondly, the manner of the apostle; his faithfulness, earnestless, constancy, and sincerity in practicing himself what he inculcated upon others. These virtues are highly important, are indispensably requisite in the character of a gospel minister, and they were all eminently illustrated in the example of Paul. Each of them is strongly implied in what he says of himself to the Ephesian elders. His faithfulness is the direct import of the text. “I have not shunned to declare unto you all the counsel of God.” Nor was it more obvious in the unreservedness of his communications than in his manner of making them. As he kept back nothing that might be profitable, his constant study was, how to be most profitable, and accomplish the great end of his ministry in persuading men. Every faithful minister will copy after him in this respect, and will propose to himself the same object as his grand and ultimate aim. To promote this end, all his studies and endeavours will be steadily directed. In the choice of his subjects, and in his manner of handling them, he will be guided by what in his conscience he thinks will be most useful to his hearers. Merely to amuse and entertain them with the pop of language, or the charms of eloquence; or to gain their applause by gratifying their curiosity, or feeding their passions and prejudices, he will always esteem unbecoming the solemnity of a religious assembly, and below the dignity of a Christian minister. St. Paul preached not himself, but Christ Jesus the Lord. That desire of fame to himself, that ambition of being known and distinguished, which fired the ancient orators of Greece and Rome, was far below the sublime views by which the apostle was actuated. Had he been capable of seeking praise with men, his knowledge as an apostle might have been no impediment. The man who had been admitted within the veil, caught up into heaven, and initiated into the secrets of the invisible world, had it undoubtedly in his power to have gratified human curiosity on a number of questions concerning which it eagerly inquires. Should not his silence upon such questions, correct the vanity of those preachers who are always studying to surprise their hearers with some new discovery in divinity?

If such pretended discoveries have no conceivable relation to practical godliness; if curious disquisitions upon subjects of little consequence, uninteresting speculations, or dry criticisms even upon the scriptures themselves, form the bulk of a preacher’s discourses; or if he confounds his hearers with controversial divinity, and is always endeavouring to reestablish some favourite system of human construction, and under the impression of its peculiarities, gives to every discourse, be the text what it may, the same general complexion; if his preaching be destitute of that variety of different views and illustrations which the rich treasure of scripture affords; or if in treating on the important doctrines of the gospel, he introduces a train of intricate and perplexed reasoning; or if in teaching the moral virtues, he recommends them by no other arguments than a Plato or a Socrates would have used; if he forgets to assign them their proper place in the Christian system, or to enforce them by those peculiar motives which the gospel furnishes; if he adopts either of these defective modes of preaching, though he should be ever so laborious in his studies, yet must he not fall short of that profit to his hearers which is essential to faithfulness?

As the arts of persuasion are the only ones by which success in preaching is to be attempted, with what diligence should they be studied? How solicitous will the faithful minister be in acquainting himself with the most engaging methods of address? How careful and circumspect, left in little things, he stir up prejudices which may lessen his influence in matters of greater moment. In this respect, few of us, perhaps are sufficiently wary. Some, indeed, when they have once settled in their own minds, what is right, seem to make it a point of conscience, to pay no respect to the opinions or prejudices of others. Rigid and inflexible, they push their sentiments with a zeal often subversive both of peace and charity.

How very different was the conduct of the apostle? To gain upon believers, to edify the faithful and strengthen the weak in faith, with what ease did he accommodate himself to their known prepossessions? With what condescending tenderness, in matters not essential, did he become all things to all men, that by all means he might save some. With those under the law, or who looked upon themselves as bound by its ceremonial rites, he readily complied with those rites, though he knew them to have been abolished: Whilst with those who had obtained the same knowledge with himself, he as constantly used his Christian liberty. “To the weak he became, as weak, and would eat no meat, whilst the world standeth, rather than make the weakest brother to offend.” Had the same temper continued universally to prevail in the church, the bonds of charity would never have been broken. From the beginning, all the different sects and denominations of Christians would have dwelt together in unity like brethren.

The faithful minister will consider, not only the prevailing prejudices of his people, but their capacities, characters and religious circumstances; and to these adapt his discourses, his method of reasoning and address. Thus he will distinguish the precious from the vile, warn the unruly, and comfort the feeble indeed, and give to every one his portion in due season. With admirable wisdom and a nice discernment of circumstances and characters, this was done by the apostle on every occasion. To the heathen worshipping dumb idols, he set forth the absurdity of idolatry. Their objection against him was, his saying, that, they be no Gods, which are made with hands. To the Jews who had received by Moses and the prophets the shadow of the gospel, the hope of the Messiah, he immediately testified, that Jesus was the Messiah whom they expected. To the awakened jailor inquiring, What he should do to be saved, “he immediately answers, believe on the Lord Jesus Christ: Whilst with the hardened unprincipled Felix, he reasons of righteousness, temperance and a judgment to come. Knowing himself the terror of the Lord, he fought to persuade men, to alarm the vicious, and arouse the thoughtless, by a faithful denunciation of that wrath, “which is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness, and unrighteousness of men.” Many there are in every congregation, to whom these warnings are still necessary. 2 And whether they will hear, or whether they will forbear, the watchman cannot, with safety, shun to declare them. For he is himself warned, “If thou speak not to warn the wicked from his way, he shall die in his iniquity; but his blood will I require at thine hand. Yet if thou warn the wicked and he turn not, he shall die in his iniquity; but thou hast delivered thy soul.”

In dispensing these warnings, and indeed all the other truths of the gospel, the fervor and earnestness of the apostle, as well as his faithfulness, are to be our model. Upon his mind the gospel took full hold, and knowing its truth, he felt its importance “counting all things to be loss for the excellency of the knowledge of Christ,” he felt no other interest or concern here below but in its spread and success. Of course his preaching, was not with the enticing words of man’s wisdom, or the studied forms of human eloquence, but in the words of truth and soberness warm from his heart. With an air of deep and awful concern he persuaded men. In his addresses to them, his soul melted, (if we may so speak) and like his divine Master weeping over Jerusalem, flowed forth in streams of tenderness and compassion. To those addressed in the text he says, remember that by the space of three years I ceased not to warn every one night and day with tears.

This appearance of earnestness cannot be tolerably imitated without the reality. The affectation of it in feigned tears and a melancholy tone, or by vociferation and unusual gestures, succeeds with a very few only of the most ignorant and undiscerning: To a judicious audience these hypocritical arts are always disgusting. A degree of St. Paul’s faith, charity and piety is essential to that earnestness which he expressed. If the great principles of religion warm the heart of the preacher, they will influence him in the composition as well as in the delivery of his discourses. Despising frivolous ostentations harangues, he will study to place divine truth in a light the most advantageous for conviction and persuasion, that it may at once enlighten the understanding and touch the heart. In order to this it is necessary, that the composition be solid, cogent and animated, free from dull explanations of what is already sufficiently obvious, and uninteresting paraphrases on passages of scripture needing no illustration. The plain simple language of the Bible is always more lively and striking, than the circumlocution of a paraphrase. 3

When due care has been taken in the composition of a discourse to render it worthy of attention, the consciousness of this in the preacher will animate his delivery. And if he enters into the spirit of his subject, and feels it upon his own heart; his earnestness being real, will prove affecting to the hearers: The piety which glows in his bosom will be in a measure communicated to theirs.

With this earnestness is to be united the most persevering diligence in fulfilling the private as well public duties of the ministry. In the example of Paul we behold an unremitting attention to his work. He taught not in public only, but from house to house, and by night as well as by day. And he charges Timothy to be instant in season and out of season, “watching for souls as one that must give an account.” The Christian minister should be always ready to deliver those who are drawn unto death; pulling them out of the fire, giving to every one that asketh a reason for the gospel hope, reproving, rebuking, exhorting families and individuals as there may be occasion from day to day. In the course of providence favourable opportunities frequently occur for rendering in a private way, important services to the souls of men. Among the sons and daughters of affliction, in the chambers of sickness and houses of mourning the visits of a sympathizing minister are always welcome, and his counsels and exhortations are heard with more than ordinary attention. In this way it is expected of him, that he go about doing good.

Yea, it is expected, not only in those kind offices which belong immediately to his profession, but in his whole conversation and deportment, and that he exhibit the benevolent spirit of the gospel and exemplify its precepts. It is essential to the right discharge of their office, that ministers consider themselves, “not as Lords over God’s heritage, but as ensamples to the flock; in a word, in conversation, in charity, in faith, in purity.” Having the same interest with their hearers in the gospel which they preach, it will not be believed, that they are earnest in pointing out the way of salvation to others, unless they themselves visibly walk in this way. Their exemplary deportment as Christians will add weight to their instructions as ministers of Christ; and have an happy influence in recommending his religion. No arguments have a more persuasive force with the world in general to the practice of religion, than the beholding of it illustrated and shining in the lives of its teachers. Every minister should so live, as to be able thus to address his people, Be ye followers of me as I also am of Christ.

In Paul we behold a disinterestedness, fortitude and sincerity in practicing himself what he inculcated upon others, worthy of universal imitation. To the Ephesian elders he appeals as having witnessed the display of these virtues through the whole period of his continuance among them. “Ye know, from the first day that I came into Asia, after what manner I have been with you at all seasons, serving the Lord with all humility of mind, and with many tears and temptations; shewing you all things, how that so laboring ye ought to support the weak; coveting no man’s silver, or gold or apparel. Yourselves know, that these hands have ministered to my necessities, and to them that were with me.” While he strongly asserted the right of those who preach the gospel, to live of the gospel; for special reasons he waved this right in his own case. Straights and difficulties he frequently experienced, and in every city had the certain prospect of bonds and afflictions; yet no distresses, however heavy, no dangers, however formidable, did in the least dishearten him, or shake his resolution.

“None of these things move me, says he, neither count I my life dear unto myself, so that I might finish my course with joy, and the ministry, which I have received.” And so well did he finish, so complete was his fulfillment of this ministry among the Ephesians, that he adds, “I take you to record this day, that I am pure from the blood of all men.” Happy Paul! Who had managed so high a trust with such fidelity as to enjoy the comfort of this reflection.

To us, my fathers and brethren, the same trust, though in an inferior sense, is committed. With the office of declaring the counsels of God for the salvation of men we are honoured. To ourselves, as well as to our respective charges, it is of no small moment, that we form ourselves after the model of Paul and the other apostles; that the principles and views from which they acted, have a governing influence over us, that like them we approve our fidelity by keeping back nothing that may be profitable, and enforcing the whole by our own example. Moderate desires with respect to the good things of this life, and patience and fortitude in bearing its evil things, are highly becoming the ministers of a crucified Saviour. Some evil things are to be expected. From men of corrupt minds opposition is scarcely avoidable. Faithfulness, when it fails of reclaiming them, often provokes their angry passions and draws upon itself a torrent of abuse. Let none of these things move us from the steady discharge of our duty. Knowing that it is but a small thing to be judged of man’s judgment, let our great concern be to stand approved at an higher tribunal. Behold, our witness is in heaven our record is on high. Stewards of the mysteries of God let it satisfy us, if our faithfulness be known to him. The period will soon arrive when his judgment will be manifested. Let the serious thought of this, under every discouragement, animate our diligence and fidelity. The expected summons, give an account of thy stewardship; for thou mayest be no longer steward, may well arouse our utmost exertions.

In the mean while, changes are continually taking place. Paul is constrained to bid adieu to his Ephesian friends: The period of separation arrives, and they can see his face no more. Thus all earthly friendships, relations and connections are dissolved. While we ourselves are suffered to continue, the flight of time, of days, months and years bears away from under our care the fouls at first committed to our charge, and transmits them into that state where they try the reality of those discoveries which we announce to them from the word of God. How many who once sat under our ministry, are gone already! What their condition is in the world on which they have entered, we know not. But to ourselves it may be of importance, seriously to inquire, whether if any of them have miscarried, it has been in no degree owing to our negligence? Are we indeed pure from the blood of all men?

Under a consciousness of our defects, it becomes us to humble our souls before God, and while we implore his pardon for the past, to renew our resolutions, by his grace assisting, of greater diligence for the future. And may his mercy grant, that when our day shall end, we may be able to look back upon its labours with comfort, and forward to their reward in the world of glory with hope and joyful expectation!

To you, my brother, in particular, at the close of that scene of labour on which you are now entering, I most ardently with this felicity. To point out the way leading to it, has been the design of the preceding discourse. From my acquaintance with you I have just grounds to believe that your heart is steadily inclined towards what has been now recommended, and that you wish to excel in all the qualifications of an able and faithful minister of Christ. Descended from one of this character, 4 an ornament to his profession, and trained up with every advantage from his instruction and example; you now come forward with the raised hopes of your friends, and the good wishes of all your acquaintance. Providence is casting your lot in a pleasant part of the vineyard, and many circumstances concur in rendering the prospect before you agreeable and pleasing.

But you are not insensible of the arduous nature of the work in which you are engaging, nor of the trials to be expected in its prosecution. Oft have you contemplated the charge which you are now to receive, and under the apprehension of its weight and solemnity, have breathed forth the sigh, who is sufficient for these things! Had your father’s life been still spared, what a tide of paternal affection would have swollen his bosom in addressing you on this solemn occasion! How would he have poured forth his soul in tenderness for you; in soothing your spirit; in encouraging, directing and animating you! A sovereign God has ordered it otherwise, and one stands in his place who can only say, “Look to thy Father in heaven whose grace is sufficient for thee.” A lively spirit of devotion, my brother, is not more suitable to the character of a Christian minister, than necessary to fit him for the right discharge of every part of his duty. It raises the mind to an elevation proper either for studying the great mysteries of godliness, or performing its sacred offices. It invigorates all the faculties, and renders that a pleasure which would otherwise be gone through as a burden. It even leads to the hope of communication and assistance from above. If under a sense of our lack of wisdom, we humbly ask it of God, we are encouraged to expect, that he will give liberally.

Of every advantage from devotion, reading, conversation and study you will endeavour to avail yourself. With your aged and venerable colleague you will frequently consult, and by a respectful tenderness and sympathy with him under his growing infirmities, console the evening of his life. From his experience and knowledge of the state of this people you may receive much useful information. By adapting your discourses to their spiritual circumstances and giving to every one their portion in due season, you will, in the course of your ministry, declare all the counsel of God. May he prolong your life, give eminence to your character, success to your labours, and in the end, accept you with a well done good and faithful servant!

It is with pleasure, my brethren of this church and society, that we witness your zeal for the institutions of the gospel, and desire of hearing those divine counsels which concern the common salvation. The decays of nature having withdrawn your aged pastor from those labours, which, through the course of many years, he performed with honour to himself and profit to his people; you early sought, and this day happily obtain another to be set over you in the Lord. We rejoice in your peace and unanimity; and honour you for the wisdom and judgment, which, in our esteem, you have shown in this election. We are persuaded of the good abilities and good dispositions of our friend, who is now to be inducted into office.

With you it remains, to give an hearty welcome to him who thus cometh in the name of the Lord. Know him in his office as a minister of Christ. Esteem him highly in love for his work’s sake. Assist him with your prayers, and encourage him by a regular and general attendance on his ministrations. Look with candour on his public performances and private conduct. Forbear to notice those failings which are inseparable from human weakness. Guard his reputation with the vigilance of true friendship, and protect it from every rude assault. Clear his way before him of all difficulties and obstacles so far as you are able. Study to extend his influence, and promote his usefulness to the utmost. And let him see, that you profit by his labours; that you improve in knowledge and virtue, and in a conversation becoming the Gospel of Christ. Thus he will prove an helper of your joys, and you will become his in the day of the Lord Jesus.

My respected hearers of this great assembly, we find ourselves lately brought into existence, and rapidly hurrying through life. We are anxious to know what is to be done with us hereafter, and what are the intensions of our Creator concerning us. But who hath known the mind of the Lord? Or who can penetrate the secrets of his will? The things of God knoweth no man; but the spirit of God searcheth all the depths of his counsels, and is conscious of all his designs; and by his spirit they are revealed unto us in the gospel of his son. This divine revelation removes the veil, and lays open to human view his eternal counsels with respect to the present and future destinations of men. On these subjects your ministers from time to time address you. They declare to you the counsel of God—the gospel of his grace. Your recovery from sin and ruin, and final salvation are the object of this high dispensation. For the obtaining of this end, it makes the most ample provision, and furnishes every necessary mean. Suffer it to have its due effect upon your hearts and lives, and it will guide you to life eternal. Let me entreat you, therefore, not to receive the grace of God in vain. For how shall we escape, if we neglect so great salvation? To day if ye will hear his voice, harden not your hearts. The wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life, through Jesus Christ our Lord; to whom be glory for ever,

BY THE

Rev. WILLIAM EMERSON

OF HARVARD.

To imagine the Deity, therefore, to be deficient in love towards any of his creatures is criminally to mistake his true character. It is, without doubt, less wrong to deny the existence of a God, than to suppose the God, whom we adore, is not infinitely good.

Hence, Christianity seems principally concerned to display the benignity of the divine nature. Christ has, indeed, taught us truths, which we could not have known, except by preternatural revelation. It is, however, a distinguishing excellence in his religion, that it ripens the hope, which nature, from the first, produced, that the original of all things is full of placability [forgiveness] and good will. I say, it is the glory of the gospel to confirm to us the truth, which, since time began, was imprinted, as with a sunbeam, on the face of the world, that God is love.

It is remarkable, as this divine dispensation had its origin in love, and is the most illustrious instance of love, that the history of man can furnish, so it must be perfected by the same heavenly quality.

Accordingly, its professors and teachers are happy to embrace every fit opportunity sensibly to manifest to each other and to mankind, that they are in truth governed by the spirit of their religion.

Wherefore, reverend and dear Sir, perceiving the grace that is given to you, and ardent to love you, not in word only and in tongue, we thus express to you the joy we derive from the late solemn transaction.

In observing, on the present occasion, this significant and apostolic custom, the elders and messengers from many branches of the Christian church, now convened, acknowledge you a disciple of Jesus Christ, and duly commissioned to preach his religion. We hereby welcome you to a place in our fellowship and affections. We rejoice, that God has qualified you for the office of a Christian minister, and that he has inclined your heart to devote yourself to so useful and pleasurable an employment. It also gladdens us, that the bounds of your habitation are fixed in this part of Christendom, that the lines have fallen to you so pleasantly, and that you have so goodly an heritage. As long, as you continue to feed this heritage with knowledge, and to sustain the function, you have assumed, with true dignity, it will form one of our most exalted pleasures to be auxiliary and kindly affectioned towards you, as well in the private scenes, as in public labours of your life.

At the same moment, Sir, we are filled with the joyful persuasion, that you will ever readily meet us in the exercise of the friendly dispositions. Yes, my friend, this hand, which I have long been used to receive as the faithful representative of a sound heart, is to me, and, I presume, to my reverend fathers and brethren, a sure evidence of your purpose to live with us in the charity of our holy faith, and in the cordial reciprocation of benevolent offices.

Now fare thou well, brother, whom I love in the truth! May the God of thy fathers bless thee, and make thee happy through the course of a long and successful ministry. Let the dictates of an enlightened understanding, the love of humanity, the shade of a pious parent, the honour of Christ, and the desire of God’s approbation uniformly incite thee to fidelity in thy sacred character, and to deeds of honest glory in the various relations, thou mayest hold, in the brotherhood of man. And, at the last, mayest thou be crowned with consummate and eternal felicity!

We congratulate you, brethren of this religious society, on the joyous solemnities of this day. Surely this is the day, which the Lord hath made. Well may your hearts rejoice and be glad in it. For it is the day, to which ye have long anxiously looked, and which confers upon you the minister of your early choice, whom ye justly consider as an Israelite indeed in whom there is no guile. Behold, now, the man Blessed be he, that cometh to you in the name of the Lord! Be entreated to own him as a gift of our ascended Redeemer, and to know him in his station Yea, beloved in the Lord, we beseech you, by ministering to his necessities, by fair construction of his conduct, courteous behavior to his person, and chiefly, by giving heed to the words of his mouth confirm your love towards this our brother.

Amid the important concernments of the hour your aged and worthy pastor has a dear interest in our memory and feelings. We have blessed him this day out of the house of the Lord. We trust, ye will solace the evening of his days by the continuance of those amiable kindnesses, which have so long endeared you to his heart, and whose commendation gives such an unction to the precepts of our Lord and yours.

Finally, brethren, seeing that ye walk in the truth, and in love one with another, we do recognize you, as the church of God and of Christ. So, then, ye are the temple of the living God. As God hath said, I will dwell in them, and will walk in them; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people.

Arise now, therefore, O Lord God, into thy resting place, thou and the ark of thy strength! Let thy priests be clothed with salvation, cause thy saints to rejoice in goodness, and let all the people say—Amen

Endnotes

1 See Acts xvii. 22.

2 It is matter of regret, that any should object to this part of ministerial faithfulness. No excuse indeed is to be offered for those preachers who endeavour to supply the want of sensible composition and of a serious and rational method of address by overbearing noise and terror: Censure upon them is just. Yet it is a melancholy fact, that the refinement of modern times has produced some occasional hearers, (for they are not in general, very constant in attending public worship) whose delicacy seems to be shocked at the least mention of the threatenings in scripture. “Let us, say they, be drawn by the beauties of virtue and the hopes of heaven, and not driven by the terrours of hell. We chuse not to be frightened into our duty.” Upon this principle, they openly avow their disapprobation of all discourses upon the terrours of the world to come and the doom of the ungodly at the last day. They affect to despise the preacher, who, by these motives would persuade men to holiness. In their opinion he not only exposes his ignorance of human nature, but his want of sensibility and benevolence of heart, by thus endeavouring to alarm his hearers. Pronouncing him to be both ignorant and unfeeling, they glory in their contempt of all his admonitions. But, before men suffer themselves to receive the prejudice which such sentiments and language are adapted to convey, they ought seriously to consider, whether the danger of which they are warned, be real or not. From ignorance or ill design false alarms do indeed proceed. With these we are justly displeased. But no man is offended at being apprized of a danger which he believes to be real, especially when the warning tends to facilitate his escape, and is given solely for this purpose. Were you walking in the dark till your feet approached an unsuspected precipice? Were you sitting secure in your house, or sleeping in your bed, while your habitation was kindling into flames? Or in any other circumstance of real danger to your person, family or interest; previous warning of it would be so far from being deemed unkind, that he would be accounted a wretch indeed unfit to live in society, who should willfully withhold it from his neighbor or friend. The only reason why men are offended at being warned of the danger to which their souls are exposed, is because they believe not this danger to be real. Lot seemed as one that mocked unto his sons in law. In the same light every monitor appears whose warnings are not believed. And hence it will come to pass, that, as it was in the days of Lot; even thus will it be in the day when the son of man is revealed.

3 “By a multiplicity of words the sentiment is not set off and accommodated, but like David equipt in Saul’s armour, it is encumbered and oppressed. Yet this is not the only, or perhaps the worst consequence resulting from this manner of treating sacred writ. We are told of the Torpedo, that it has the wonderful quality of numbing every thing it touches. A paraphrase is a Torpedo. By its influence the most vivid sentiments become lifeless, the most sublime are flattened, the most served chilled, the most vigorous enervated. In the very best compositions of this kind that can be expected, the gospel may be compared to a rich wine of a high flavor, diluted in such a quantity of water as renders it extremely vapid.” Campbell.

4 The Rev. Ebenezer Thayer, late of Hampton, in New-Hampshire, who died Sept. 6, 1792, Et. 59.