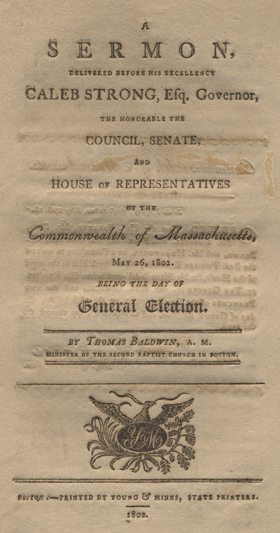

Thomas Baldwin (1753-1823) represented the town of Canaan, NH in the state legislature for a time. He was ordained in 1783 and ministered in towns in New Hampshire until 1790 when he became the pastor of the Second Baptist Church in Boston. This election sermon was preached by Rev. Baldwin in Boston, MA on May 26, 1802.

SERMON,

DELIVERED BEFORE HIS EXCELLENCY

CALEB STRONG, Esq. Governor,

THE HONORABLE THE

COUNCIL, SENATE,

AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

OF THE

Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

May 26, 1802.

BEING THE DAY OF

General Election.

By Thomas Baldwin, A. M.

MINISTER OF THE SECOND BAPTIST CHURCH IN BOSTON.

BOSTON:–PRINTED BY YOUNG & MINNS, STATE PRINTERS.

1802.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Attest,

HENRY WARREN, Clerk of the

House of Representatives.

I PETER, ii. 16.

“AS FREE, AND NOT USING YOUR LIBERTY FOR A CLOKE OF MALICIOUSNESS; BUT AS THE SERVANTS OF GOD.”

INNUMERABLE are the favors which indulgent heaven bestows on the children of men. Among the choicest of an earthly nature, we may reckon the enjoyment of personal safety, the acquisition of property, and in general the liberty of doing whatever will not be injurious to the rights of others.

In order to secure these blessings men have been induced to associate together. Their mutual wants and weaknesses urge them to unite for their common safety; and a reciprocation of kind offices, in assisting and protecting each other, forms the bond of their social union.

To give force, however, to such combinations, they must be reduced to system, their principles defined, and order and subordination established. By thus uniting, the strength of the whole body, upon any emergency, can easily be collected to a single point. In this union only individual and personal safety can be enjoyed. It will hence follow, that where the rights and privileges of all are secured, and equal protection extended, all must be under obligations to contribute to the support, and to yield obedience to them who are appointed to carry the public will into effect.

These duties are inferred from the nature of civil government in general, from the express principles of our social compact, and from the plain declarations in the word of God.

The sacred scriptures inform us of the origin and progress of society, several centuries beyond what can be found in any other writings.

The particular history of the Jewish nation for many ages together, and God’s providential dealings towards that highly favoured people, afford us much interesting instruction. Their civil policy, which was principally dictated by God himself, and the influence which religion had in forming their national character, have been faithfully recorded and handed down to us.

The glory of this nation had been gradually declining for five centuries before the Christian era; and at this time they were groaning under the Roman yoke. They were indeed looking for a Messiah, but had no idea that Jesus of Nazareth was the person. They were expecting a temporal deliverer, and not a spiritual Saviour. Therefore when Christ attempted to introduce the gospel dispensation among them, they charged him with a seditious design against the Roman government. And although he declared that his kingdom was not of this world, yet his enemies insisted that he was endeavouring to establish a separate interest, which in its tendency was subversive of social order, and hostile to the existing powers. No inference could be more unjust, nor a charge more false and cruel; yet this pretence Pilate was prevailed upon to give sentence against him. “If, said they, thou lettest this man go, thou art not Caesar’s friend; for whosoever maketh himself a king speaketh against Caesar.”

The same invidious charge was brought against the Disciples of Christ, and often made the pretext for their persecution. They charged Paul with being “a pestilent fellow, and a mover of sedition among all the Jews throughout the world.” In order to wipe off a stigma so foul, and to convince his adversaries that the benevolent religion of the gospel was not unfriendly to social order, we find him frequently inculcating upon his Christian brethren, the duties of submission and obedience to established authority. In his epistle to the Romans, he charged them to “be subject to the higher powers;” by which he evidently meant civil magistrates. To give force to the exhortation he adds, “for there is no power but of God; the powers that be are ordained of God.” The same Apostle directed Timothy to offer up “supplications, prayers, and intercessions for all that were in authority.” He also charged Titus to put the flock to which he ministered in mind, “to be subject to principalities and powers, to obey magistrates, and to be ready to every good work.”

It is worthy of observation, that when the Apostle wrote these epistles, the civil authority was wholly in the hands of Heathen magistrates. And some of them too the greatest monsters of cruelty, that were ever suffered to sway a scepter, or disgrace a throne. Tyrants, who were distinguished only by their crimes, and rendered immortal only by their infamy. Yet such was the pacific spirit of the gospel, that Christians were exhorted to “be subject, not only for wrath,” that is for fear of punishment, “but for conscience sake.”

Sentiments similar to these were enforced by the Apostle Peter, in our context. “Submit yourselves, said he, to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake. For this is the will of God, that with well-doing ye may put to silence the ignorance of foolish men. As free, and not using your liberty for a cloke of maliciousness; but as the servants of God.”

The sense of the text will more fully appear, by the following familiar paraphrase. As if he had said; “you will not, my brethren, mistake the nature of your Christian liberty, to suppose that because you profess to be the disciples of Christ, you are freed from your allegiance to the government under which you are placed. It is true, that if the Son hath made you free, then are you free indeed. But this freedom consists in being delivered from the guilt and power of sin, from the dominion of your own lusts, and from final condemnation at the great day when God shall judge the world by Jesus Christ. But instead of lessening your obligations to contribute to the peace and order of society, it greatly increases them. Your duty as Christians is urged by higher motives, and your obedience secured by more solemn sanctions. Submit yourselves therefore to every ordinance of man, designed for the good of society, and not inconsistent with the dictates of your own consciences, or the duties you owe to your God: And thus, by well-doing, you will put to silence the ignorance of foolish men, who represent your sentiments as tending to disloyalty and sedition. As free, but not abusing your liberty in using it as a cloke for malicious conduct; but in all circumstances conducting yourselves faithfully as the servants of God.”

From the subject thus placed before us, we are naturally led to the following inquiries. When may a people be said to be free? What are the means best calculated to preserve their freedom, and promote their happiness and prosperity? And, in what respects are they in danger from the abuse of their liberty?

In order to find a free people, we need not repair to Lybia’s burning sands, to learn the savage customs and manners of those barbarous descendants of Ismael, who indeed boast of their freedom, but whose liberty essentially consists, in committing, with impunity and without a blush, the most flagrant acts of violence and injustice. Nor is it necessary that the restraints imposed by wise and equitable laws should be taken off, and the force of moral principle removed in order to render a people free. Such a state of things would only produce a lawless ungovernable freedom, which would terminate in the worst kind of anarchy and confusion.

It is evident that many who pretend to be the votaries of liberty, never understood its true principles, nor conducted themselves worthy of its blessings. Genuine social liberty can never exist without being protected and supported by law, enlightened and aided by morality and religion.

But what peculiarly distinguishes a free people from all others, is, the right they collectively possess to govern themselves: Or in other words, the right of choosing and establishing their own forms of government; and of appointing to office those who make and execute the laws.

That very considerable privileges may be enjoyed under a despotic government, and that the rights of justice may in general be maintained, will be readily admitted. But if the government exists independent of the governed, they cannot be said to be free. Their security for the few privileges they do enjoy, depends not on their acknowledged rights, but entirely on the will and disposition of the persons in office.

All legitimate governments are, or ought to be founded in compact. For it is not easy to conceive how one man should have a right to rule over another, equally free as himself, without his consent: And should any one presume to exercise authority over any portion of his fellow-men, without their express or implied consent; they might, with great propriety, demand of him by what authority he did it? And who gave him this authority?

But, instead of being founded in compact, most of the governments which exist, owe their origin to some usurping tyrant; who, being more crafty, or more powerful than his neighbors, assumed dominion over them. Power thus wrongfully obtained at first, after descending from hand to hand for a few generations, at length becomes legitimated and confirmed by time.

The people of these United States are peculiarly happy in this respect. Our history does not begin with narrating the exploits of some sanguinary Chief, whose blood-stained crimes like those of Pizarro rendered him the terror of defenceless innocence, and the execration of mankind. No; we glory in a race of ancestors, who were men of the purest morals, and most unsullied virtue. Who were too pious to dissemble, and to independent to submit to ecclesiastical fulminations. Men who were willing to leave their dear native shores, and cross the wide spreading ocean in quest of this better country. Who cheerfully encountered the numerous perils of an inhospitable wilderness, in order to secure to themselves and their posterity, the unmolested enjoyment of civil and religious liberty.

These blessings and privileges they bequeathed with their dying breath to their children; and in defence of this precious legacy, we feel ourselves justified to God and the universe, in appealing to arms in our late glorious revolution.

Our cause was just, and heaven succeeded it. The contest was severe, but victory and glory followed. The sun of freedom which had been gradually rising upon these infant states, now burst forth in meridian splendor. A nation was born in a day. A new era commenced. Another empire appeared on the map of the world. Astonished Europe beheld in this western hemisphere a new constellation. Conjecture was on tiptoe gazing, and speculation with unusual adroitness was endeavouring to find its magnitude and motion. Some thought they discovered a new planet in the political horizon, moving regularly in its own orbit. Others concluded it would prove only a satellite of some European power. But many who viewed it through a set of royal optics, conceived it to be only a baleful comet, portending revolution and war, making a hasty transit, and expected momently it would disappear. But, they had yet to learn that we were “a world by ourselves;” that we were independent Republicans; that we were free.

When the passions incident to a state of war had subsided, and God had given us rest from all our enemies round about, the public attention was naturally drawn to our internal situation. Our provisional government, which, like the tabernacle in the wilderness, had been erected during our revolutionary march, was too defective and inefficient for our future security. It was unable to preserve public credit, or secure public confidence. It hence became indispensibly necessary in order to consolidate the union of the States, and to give permanency and dignity to our national character, that a new Constitution should be formed. That the powers of the different branches of the general government should be specifically defined; their limits so distinctly marked as not to interfere with each other; and sufficient energy given to the whole, to support order and tranquility at home, honor and good faith with all nations with whom we were connected abroad.

Delegates were accordingly appointed by the different States who met in convention for this purpose. This was at a time and under circumstances peculiarly favourable to the design. The attachments which we once felt for royalty, had been completely subdued, by a long series of tyrannical and vindictive oppression. Nor had been completely subdued, by a long series of tyrannical and vindictive oppression. Nor had the Republican name at this time, been disgraced by acts of cruelty and irreligion. The friendly ties which bound us together during the period of our common danger, had scarcely began to slacken; and invidious distinctions between the different States were made (if at all) with great caution. Party-spirit, that Apollyon of all popular governments as yet slept in silent embryo. (Would to God its sleep had been perpetual.) No suspicious circumstances of personal power and aggrandizement, awakened either our jealousies or our fears. Nor could we feel any, for at the head of this venerable assembly was our late illustrious Chief. But not in arms like a perpetual Dictator, awing them into submission to his will. No; for like Timolion when he saw his country free, he sheathed his sword and returned to the rank of a private citizen. Never was there an Assembly convened upon a more interesting and important occasion. For not only the present fate of their country, but the future destiny of unborn millions depended upon their decisions. They were to lay the foundation of an empire, the extent and duration of which it was impossible to calculate.—What an august spectacle was here! The Fathers of our tribes deliberately forming a plan of government. The volumes of antiquity were open before them, and the experience of all nations and ages enriched their discussions. After surveying the interests of the whole, and making such mutual concessions, as local circumstances required, they unanimously agreed in the essential articles of our present excellent Constitution. It was then submitted again to the several States, and by them examined, approved and accepted, and thus became the supreme law of the land. This it is conceived is literally a social compact, what political writers 1 have said to the contrary, notwithstanding.

This sacred instrument ought to be considered as the great charter of our rights and privileges, and as the foundation of our national civil policy. So long as we preserve it inviolate, and govern ourselves according to its true spirit, so long we shall continue to be a free people. It will be impossible for despotic power to support itself in America, until we basely degenerate from the spirit of our ancestors, and depart entirely from the principles of our confederation.

One great security against the abuse of power, is the short tenure by which it is held. No offices are made hereditary, and for this plain reason I conceive, that talents and virtue, which are essential qualifications, are not hereditary.

No country ever exhibited a fairer specimen of moral justice than ours, nor can any be found of equal population where capital punishments are less frequent. It is not because we suffer crimes to go unpunished, but by encouraging sober habits and moral principles, we in a great degree prevent them. Our laws indeed are mild, and not like those of Draco, written in blood.

Religion, at all times essential to the well-being of society, though not established, is protected and encouraged by the laws of our country. This sentiment corresponds with that divine declaration, “By Me kings reign and princes decree justice;” importing, that they need Christ’s religion to support their tottering thrones, but that his cause could exist without their authority. No sectarian creed is imposed by law upon any man, nor have we any national formulary excepting the Bible; and every man is at liberty to interpret this according to the dictates of his own conscience, and is accountable only to God for his errors.

Oppression may gain a temporary existence under the purest government, by the mismanagement of particular agents; but it ought not to be attributed to the laws, but to their perversion.

The Constitution of this Commonwealth declares itself the friend and protector of every man, who demeans himself quietly and peaceably as a good subject, let his religious sentiments be what they may. It has also decreed, that “no subordination of any one sect or denomination to another shall ever be established by law.”

If it be acknowledged that men have a right to serve God according to the light of their own understandings, then they cannot be constitutionally deprived of the means of serving him. It is not enough that the mind be left free; for the command is, thou shalt “honor the Lord with thy substance.” What Moses said when he was about to leave Egypt will apply in the present case; “Our cattle also, said he, shall go with us, there shall not an hoof be left behind; for thereof must we take to serve the Lord our God; and we know not with what we must serve the Lord until we are come hither.”

It is with peculiar pleasure that we observe at the present day, the increasing prevalence of Christian candor and liberality. This candor it is hoped, is not the offspring of torpid indifferency; much less of infidelity; but arises from more just and enlarged views of the nature and genius of the gospel. While Christians are less zealous in defending some of the outworks of the system, they ought to be more firmly united in supporting the essential articles of the “Faith once delivered to the Saints.”

Having thus considered some of our most essential rights both civil and sacred which we possess, and which we hope to convey unimpaired to our children; shall I be chargeable with vanity in saying, there never has been a nation whose history has come down to our knowledge, which has enjoyed civil and religious liberty in a greater degree than we do. If we are not a free people, I confess it surpasses my ingenuity to conceive how a people can be so.

We proceed Secondly to inquire, What are the means best calculated to preserve our freedom, and to promote our happiness and prosperity?

To which it may be answered, 1. That as all popular governments depend in a great degree on public sentiment, it is highly important that this should be enlightened.

It is an observation which I believe will not be controverted; that the more despotic a government is, the more ignorant the people generally are. It is undoubtedly the interest of those in power to keep them so. For were they once so enlightened as to understand the nature of civil liberty, and to act upon any rational system in recovering their usurped rights, it would be impossible to keep them in subjection. It is justly observed by Paley, that “the physical strength resides in the governed.” It is, therefore, truly astonishing to see millions of rational beings, no ways “deficient in strength or courage,” submitting to the will of a single tyrant; and with all the docility of the laboring ox, put their necks quietly under his yoke. Still to keep up this ignorance every manly sentiment is suppressed, and every ray of political light shut out, and the slavish doctrine of nonresistance and passive obedience inculcated, with all the zeal of fanaticism, and enforced with the terrors of everlasting punishment.

In a representative republic just the reverse of this becomes necessary. Here, it is all-important that the people should be enlightened; as they are the acknowledged source of all power, whether legislative or executive. Correct political information, therefore, cannot be too generally and widely diffused.

As the public papers are the common medium of this information, it is of the highest importance to the well-being of society, that they should be conducted with intelligence and ability, and like a witness under oath, that they should “tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.” Public opinion, which often controls the most important concerns of a government, is itself controuled and directed by so trifling a thing as a News-paper. If misrepresentations and falsehood are propagated instead of truth, the consequence will be, the people will be misled, and their liberties endangered. But the full vengeance of an abused public, will in the end, return upon the heads of those who have been thus guilty of deceiving them.

We also add, those literary institutions founded by our venerable ancestors, for the education of youth, with others of a later date; and to which the present improved state of society is so much indebted, must be cherished and supported with unabating solicitude. There can hardly be a subject more interesting to a community, or more deserving of legislative attention, than the education of youth and children. When this is neglected, an injury is done to society which it is impossible to repair. It is equally a violation of the law of nature, and of the express command of God. To bring up our children in the “nurture and admonition of the Lord;” is an apostolic injunction. It will be impossible to do this, if we neglect their education. The Legislature of this Commonwealth have done much already, and we hope they will not “be weary in well doing;” and that their last works may be more than their first.

As those impressions which are made upon the minds of children, are seldom if ever erased; it is the more important that their education should be properly conducted. It was a judicious remark of an ancient king of Lacedemon, “That nothing should be taught children, but what may be eventually useful.” Their tender minds frequently imbibe sentiments at a much earlier period than we are apt to conceive, which have an influence ever after upon their conduct. Hannibal, was but nine years old when he was led to the altar by Hamilcar his father, and took the oath of perpetual enmity to the Romans. The solemnity of this transaction made an impression upon his mind, which probably accounts for his future conduct towards that people.

Those to whom this important trust is committed, ought to be men of principle as well as talents. A vicious man, always lacks an essential qualification to inculcate the principles of virtue. To protect and aid the opening germ of genius; “to teach the young ideas how to shoot;” to give a proper set to the wayward passions; and above all to impress the tender mind with the love of virtue and religion; though a delightful is a very arduous task. Favoured, as we are, with public schools, academies, and other literary institutions, we may hope “that our sons may be as plants grown up in their youth; that our daughters may be as corner stones, polished, after the similitude of a palace.”

But however polished and enlightened a people may be; they cannot expect long to enjoy either freedom or prosperity unless they are virtuous.—We therefore add, 2d. That the practice of moral virtue, or religion, is essential to the prosperity, if not to the existence of a free government. Where the authority of God is treated with contempt, and the great principles of morality and religion are disregarded, it must be expected that the vile passions will triumph and reign; and instead of rational liberty nothing will remain but an unbounded licentiousness.

Public confidence always attaches to moral principle; and hence in the same proportion this is vitiated, that is weakened. I appeal to the good sense of this enlightened audience, whether you can possibly repose the same confidence in a man who convinces you that he has no belief in the moral perfections of the Deity, and who does not feel himself accountable to such a Being, as in one who gives evidence that he acts under the influence of religious principle, and with a view to a day of final retribution?

If we look back into the remotest depths of Jewish antiquity, we shall find their most distinguished Patriarchs acting under the influence of this principle; and not unfrequently appealing to an invisible Power, to confirm and give solemnity to their social transactions. The same sentiment prevailed in the Pagan world.

Amphictyon, by whose eloquence and address the Grecian cities were first prevailed upon to unite for their common safety, was so fully convinced, that “those political connections are the most lasting, which are strengthened by religion,” that he committed to the council at Thermopylae, the care of the Delphian Temple.

The religion of the Bible, above all others, has a peculiar tendency to cement and strengthen the bands of society, and promote the happiness of mankind. It inculcates the purest precepts, and exemplifies the most amiable virtues. Every man, let his rank in society be what it may, will here find his duty plainly pointed out, and illustrated by example.

From the history given of the Jewish people, and the different characters of their civil rulers, the magistrates of other nations may derive the most interesting lessons of instruction. They will find, that those who ruled in integrity and uprightness, and walked in the fear of the Lord, were blessed in their administrations, and their people were prosperous and happy. On the other hand, those who disregarded the counsels of heaven, and chose out their own ways, generally involved themselves and the nation in calamity and ruin.

When a virtuous pious Prince was upon the throne, it frequently produced an immediate effect upon the manners and moral character of the people. What a surprising and happy change was often visible! The monuments of idolatry were destroyed, and the worship of the true God restored. The temple doors which had been closed, were opened, the sanctuary cleansed, and the fire which had gone out rekindled upon their altars. The Priests and Levites, who had fled to their fields, were invited back, and placed in their courses, and the service of the house of the Lord set in order.

What was the consequence of all this? Universal joy and gladness. Righteousness, peace, and tranquility reigned throughout the nation.

Whenever their government fell into the hands of wicked idolatrous rulers, their pernicious principles and example, like a contagious leaven, would seem to run through the whole lump. The people would relapse again into idolatry, and vice and irreligion triumph.

Perhaps it may be asked, whether this people might not, upon the whole, have been as free and happy without any religion as with? Or whether the worshipping the true God rather than Baal had a tendency to promote their national prosperity? Their history shall furnish the answer. God forbid, that we should make the experiment, as it may be attended with very dangerous consequences!

The following account will serve to illustrate the idea: When the ten tribes revolted from the family of David, they set up Jeroboam, the son of Nebat, who made Israel to sin. After his death we have the following account given by the sacred historian:–“Now for a long time Israel hath been without the true God, without a teaching priest, and without law.” This bore a strong resemblance to what in modern times is called the “age of reason.” What a happy situation this people must have thought themselves in? Delivered from all fear and dread of that holy, just Being, whom we call God! Not only so, but they were freed from the intolerable burden and imposing dogmas of a teaching priest. This sacred class of men were deemed entirely useless, and were either dismissed or driven from the sanctuary. And to complete this happy state of things, they were also without law. No restraint from any quarter. What, no God! No priest! No law! Then consequently no future accountability! This was liberty worthy the name. What an immense harvest of felicity was now ripening before them? Could they possibly fail of being the happiest people in the world, when every obstacle was so entirely removed out of the way? We appeal to experience and fact, those great detectors of human errors, for an answer. They declare with great solemnity, that “in those times there was no peace to him that went out nor to him that came in; but great vexations were upon all the inhabitants of the countries; and nation was destroyed of nation, and city of city; for God did vex them with all adversity.”

This is no more than what might be reasonably expected: For when a people give up their religion, and renounce the authority of God, they will not hesitate to overleap all bounds of law and morality, and destroy one another.

From this brief specimen it appears, that the social order and happiness of a community depend essentially on the influence of moral principle; and we may venture to say, should this be destroyed, exterior force can never supply its place. Without it, we shall never practice that “righteousness which exalteth a nation;” but shall inevitably fall into those “sins which are the reproach of any people.”

There never has been a people, since the tribes ransomed from Egyptian bondage, under greater obligations to their God than we are; and should we basely apostatize from our holy religion, and use our liberty only for a cloke of maliciousness, we must expect some chosen curse will pursue us to final ruin.

But in a world like this, neither innocency nor uprightness will always preserve a people from the designs of avarice and ambition.

We, therefore, add 3d, Another mean of preserving our liberty and of promoting our prosperity is the power we possess of defending ourselves. Without the means of self-defence, the liberties of a people can never be safe. A state of weakness always invites aggression. Ambitious men seldom want a pretext to plunder and destroy such as have not the power of resistance. Popular governments have been supposed less capable of self-defence, than those of a monarchical form; because it is thought to be more difficult to collect their energies, and direct them to any certain point. Hence the destiny of our Republic has often been predicted by the fate of others. It has been supposed that the seeds of mortality are sown in the constitution of all Republics, that they grow with their growth, and strengthen with their strength, and that their early dissolution follows of course. But this is not true as applied to them in particular. No human government is exempt from disaster and change. Should it be asked, where are those republics of Greece and Rome, which make such a figure in ancient history? In reply, I would ask, where are those mighty monarchies which were raised on their ruins? The Grecian republics, retained their freedom for seven centuries; whereas the monarchy, which by the arms of Alexander was extended over great part of the known world, scarcely outlived its founder. The republic of Rome, after the expulsion of Tarquin, maintained its liberties for five hundred years. Nor did the empire, though one of the most powerful and despotic that ever existed, continue longer. It commenced nearly with the Christian era, was divided in the beginning of the 4th century, by Constantine, and in the fifth, wholly subverted, and a barbarous Chieftain seated on the throne of the Caesars. The causes which brought on the ruin of Sparta, Carthage, and Rome itself, are too well known to require a recital on this occasion.

It must here be remembered, however, that our republic differs essentially, in its constitution and genius, from all others, both ancient and modern. Had the Grecian states, instead of their Amphictyon Council, formed a permanent government like ours, they could not have been practiced upon separately, and ruined by the insidious arts of Philip, of Macedon. But, my brethren, we are blessed with a government which combines energy with freedom. God hath also put in our power ample means of defence; and we may hope, under the auspices of an indulgent Providence, long to enjoy our precious privileges.

When we look back to that perilous moment when we first assumed the attitude of self-defence, and compare our present situation and resources with what they then were, gratitude and joy rush in upon our souls, and constrain us to say, “the Lord hath done great things for us, whereof we are glad.”

We are by the providence of God, at this time, in the honorable and quiet possession of a country of vast extent and fertility. Our soil, luxuriant as the land of Nile; and our atmosphere, pure as that which surrounded the famed Helicon. The wide Atlantic laves our eastern board, and forms one barrier to the progress of invasion; and at the same time wafts to our shores the fruits and treasures of every clime. On its bays and inlets our ancient towns and cities are planted. Here, the busy multitude throng; and trade, and commerce collect their immense stores of wealth. Here, elegance and refinement unite their powers, to please the imagination and improve the heart.

On the west, the Mississippi rolls in majestic grandeur; and by receiving the waters of the Ohio into its bosom, opens a communication of vast extent into those fertile regions. Here, the wilderness is turned into a fruitful field, and golden harvests smile in the rays of a setting sun. Where the Savage lately pursued his nimble chase, we now behold large towns and flourishing villages, adorned with temples sacred to religion, and crowded with devout and adoring worshippers of the Lamb.

No considerable part of our extensive territory, but what is capable under the hand of cultivation, of yielding subsistence for man.

Were we to rise with the morning sun, and travel on its rays round the globe, we should not find a nation more distinguished by its blessings than our own. Every uneasy thought therefore must be deemed ingratitude, and every murmur rebellion against heaven.

Should a foreign enemy attempt to invade our country, he would meet a phalanx of veterans more impenetrable than walls of granite. Our dependence is not on foreign auxiliaries or mercenary aid; but under God, we rely on the skill and bravery of our own citizens. Do we need ships of war? Our own immense forests, our forges and work-shops furnish the materials; and our skillful artisans construct them in a manner, equal, if not superior to any which float on the bosom of the deep. Indeed, every article necessary in the whole apparatus of war, is, or may be furnished by ourselves. It is not then to be believed, that five millions of people, breathing the air of freedom and tasting her joys, inured to hardy enterprise, and lords of the soil they cultivate, can ever be conquered by any foreign foe, unless the stars in their courses fight against them.

With such immense and increasing resources, our only danger arises from the abuse of our liberty, which was the last thing in the method to be attended to.

Permit me briefly to observe on two or three particulars. The right of private judgment, or what is commonly called liberty of conscience, is one of our dearest privileges. This right is unalienable in its nature. For the enjoyment of this, our forefathers left their friends and country, and sought an asylum in this then howling wilderness. But precious as this privilege is, it is liable to abuse. A very malicious design may be concealed under the cloke of religious liberty. It is to be feared that many under this pretence, are in reality opposing and endeavouring to destroy all religion. Some by denying, others by corrupting its important doctrines and institutions. This is an abuse too for which there is no legal remedy. It seems to be beyond the jurisdiction of the civil magistrate. According to our context, his power extends only to the punishment of evil doers, and not erroneous or heretical opinions. He that undertakes to decide on another’s sincerity, ought certainly to know his heart; other ways, in attempting to root out these tares, he will be in danger of destroying the wheat. I know of nothing but light that will remove darkness; nor any antidote to error but truth. If men will abuse their Christian liberty, they must answer it to God.

Another important privilege, is the right of electing our own civil rulers. This is the distinguishing criterion of a free government. But we are in great danger of abusing this privilege; and especially at such a season as the present, when party spirit is wrought up to its highest pitch. When we suffer our prejudices and passions to influence our choice; when our judgment and conscience are sacrificed at the shrine of party zeal; when we pass over tried merit, and prefer an unworthy candidate because he is of a particular party; do we not then abuse our liberty? If our elections are biased and corrupted, our government will be corrupt, and consequently, our liberty will be endangered.

I add once more, The right to investigate the official conduct of all public agents, and in a respectful decent manner to publish our opinions of them, is one of the privileges of a free people. But, when under this pretence, we calumniate and asperse the characters of our rulers, and endeavour to expose them to public contempt, this is a very malicious and dangerous abuse of our liberty. It is not easy to calculate the extent of this mischief; for by traducing their characters, and misrepresenting their motives and measures, we destroy public confidence, and prepare the minds of the less informed part of the community for complete opposition and revolt. This abuse has also another bad effect: It tends to alienate one citizen from another, and kindle the flame of discord throughout the nation.

To guard against this, we need only to reflect, that our national safety and prosperity depend chiefly upon our union. So long as we continue virtuous and united, we have little to fear. But should patient Heaven, offended by our aggravated provocations, give us up to a spirit of national distraction and discord, our ruin would be speedy and inevitable.

The fate of all preceding Republics, and the causes which accelerated their ruin, have been recorded by the faithful historian. Signals also have been placed on all the rocks and shoals on which they foundered, to give us the friendly warning. I have been trying to read the inscriptions on these monuments, but can make out distinctly only the three following words, which seem to have been written in capitals, LUXURY, EFFEMINACY, and DISUNION. “United we stand, divided we fall.” This was our motto in those “times which tried men’s souls.” The sentiment is equally important at this time. Young Sampson’s great strength, we are told, lay in seven locks united in one head; but ours in seventeen. If we suffer them to be shorn, or a part cut off, our strength will most certainly depart from us.

Is it not then the duty of every friend to his country to discountenance every attempt to alienate one part of our citizens from another? Whoever endeavours to induce the belief, that the interests of one State are incompatible with those of another, or with the interests of the whole, ought to be considered, at least, as a very doubtful friend.

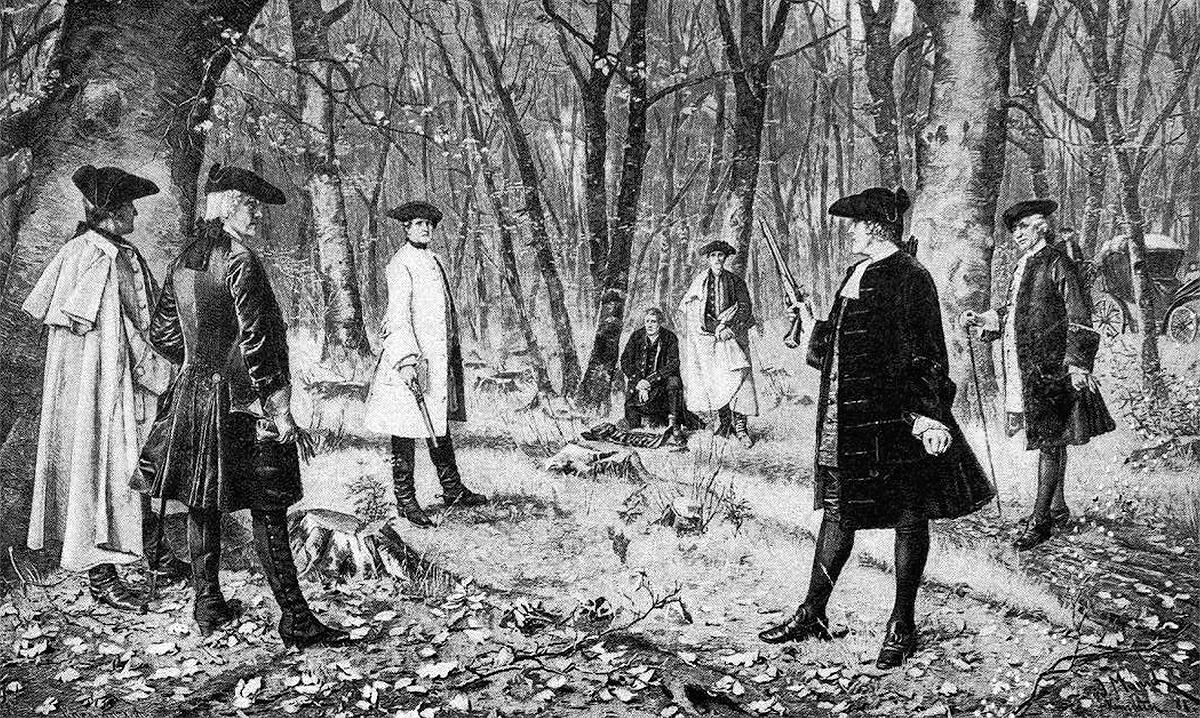

But it may be said, the speaker is only opposing a “man of straw.” I could wish indeed we had been said and done been without meaning? If so, it ought to have been suppressed. I am sure many well-informed persons 2 have been seriously alarmed at the progress of arty disaffection; and have feared lest some untoward circumstance should provoke the mad attempt to divide our hitherto happy Republic. Should we once begin the work of separation, God knows where it may end, and what the consequences may be. It will be remembered that the imprudent conduct of Rehoboam, urged on by the impetuous zeal of the young men who were about him, caused ten tribes to revolt from the house of David. What was the consequence? A civil war; in which half a million fell by the sword! The greatest slaughter, which, perhaps, has ever been in a single battle since the world began.

The danger of disunion, which we are considering, was contemplated by our late beloved Washington, and a most solemn warning given us in his farewell address. Permit me to enrich my discourse with a paragraph from it. “The unity of government, (saith he) which constitutes you one people, is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is the main pillar in the edifice of your real independence; the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety, of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But, as it is easy to foresee, that from different quarters much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress, against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual and immoveable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of an attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.” This seasonable advice, it is hoped, will have its weight. You will remember that though dead, he yet speaketh.

Nor can a doubt be entertained, but his worthy successor, our late excellent President, held the same sentiment with regard to our union; and had he addressed the people when retiring from office, we may presume he would have exhorted us to cleave to our federal union as the “sheet-anchor” of our hopes.

Permit me to add, that whatever difference of opinion there may be in other respects, our present Chief Magistrate, in his inaugural speech, has recommended the same important sentiment with peculiar beauty and energy. But I am not insensible, that, considering the divided state of public opinion, I am here venturing on a point of very great delicacy; and yet to pass wholly unnoticed the Federal Administration, which has been constantly mentioned on all similar occasions, might be deemed disrespectful to the constituted authorities of our country. I do not, however, feel myself authorized, either to eulogize or to censure.

It is but just to observe, that our present Chief Magistrate, as well as his predecessors, was among the first asserters of our freedom and independence. At this early period, his distinguished talents and patriotism, procured him the esteem and confidence of his fellow citizens. When we add to this, the many important offices he has sustained with reputation, both in his own State and under the General Government, we shall not doubt his ability to conduct our public affairs, in such a manner as shall promote our prosperity, and do honor to the American character.

It will not be denied that the present administration differs in some important points from the preceding; and that a new order of things in some respects is taking place. What the final effect will be upon our political happiness and prosperity must be left for time to determine. I will only add, our religious as well as our political sentiments, oblige us to “give custom to whom custom, and honor to whom honor is due.”

It is confidently hoped, that the distinguished rank which this Commonwealth has hitherto held in the American union, will be maintained with increasing influence and splendor. That our citizens may be as remarkable for the practice of moral virtue, as for their regard to rational liberty and social order; and that we may ever be indulged with the propitious smiles of that gracious Providence, which has hitherto directed our destiny. Happy indeed shall we be, if our heavenly Parent may say of us as of Israel of old; “They seek me daily, and delight to know my ways, as a nation that did righteousness, and forsook not the ordinance of their God; they ask of me the ordinances of justice; they take delight in approaching unto God.” “Happy is that people that is in such a case, yea happy is that people whose God is the Lord.”

The pleasures of this interesting anniversary, which collects together so many of our civil and religious Fathers, are greatly heightened by the presence of the Chief Magistrate of our Commonwealth.

Whilst decency forbids adulation, it is presumed that every good man esteems the approbation of his friends, next to that of his own conscience. And although he does not seek their applause, yet it must afford him pleasure to know, that his endeavours to serve their interests have not been unacceptable.

The increasing marks of esteem and confidence, manifested in the late election, are the best eulogy upon his Excellency’s past administration. He will please to accept our sincere congratulations on his re-election to the important office he sustains. Every class of citizens look up to him with an emboldened confidence, that he will cherish their interests, and consider himself with his people, as a father with his children. They have the fullest satisfaction, that his authority and example will be united in supporting good order, in encouraging and protecting virtue and religion; and in promoting every measure which shall tend to the general interest of the people.

It must be pleasing to his Excellency to reflect, that by their own choice he presides over a free people; and he may be assured that he cannot enjoy greater pleasure in serving them, than they do in honoring him. That his Excellency’s life and health may be preserved, and that he may be enabled to discharge the difficult duties of his exalted station to acceptance, our fervent prayer shall be offered up continually to Almighty God on his behalf; that when his term of service on earth shall be completed, he may be received to the immortal felicities and rewards of the heavenly state.

His Honor the Lieutenant Governor elect, will indulge us to express the satisfaction we feel, in his election to the second office in the gift of the people of this Commonwealth. From his long acquaintance with our public affairs, as well as from his talents and patriotism, we have full confidence in his assistance and co-operation with the Executive, in all the important concerns of the government. He will remember that he is to fill a place which has lately been rendered vacant by the death of one of the most amiable and best of men. A man in whom “political wisdom, patriotic virtue,” and undissembled piety all united and shone.

While the life of the deceased may serve as an example to his successor, his death will admonish him of the end of all human greatness. With such an example before him, may his public career be equally honorable to himself, and acceptable to the multitude of his brethren.

The Honorable Council, share in our respectful attention, as an assistant branch in the executive department of our government.

The elevated station they fill, as well as their own personal qualities, entitle them to our esteem and veneration. We repose great confidence in their candor and integrity in those cases where their advice and consent may be required; especially in the appointment of persons to office. That they will feel themselves above the reach of party influence, and will recommend the claims of merit, arising from fitness of character, rather than those of interest and ambition.

We have only to add our best wishes, that, whilst they essentially aid the interests of government, they may also by their example give encouragement to the cause of religion; and like that honorable Counselor of Arimathea, may they be willing, not only to lend their tombs to Jesus if needed, but may they consecrate their hearts for his throne.

The Honorable Gentlemen composing the two Branches of the Legislature, will permit us to express the lively interest we feel in the repeated marks of respect with which their friends have honored them; but especially in their present appointment. By accepting this confidential trust, they pledge themselves to the faithful discharge of it.

The duty of legislation is at all times difficult, and often perplexing. It is rendered peculiarly so at this time, by the divided state of public opinion. It would favor of an intolerant spirit to suppose, that good men may not be aiming to promote the same object, while they differ in the means best calculated to attain it. Mutual candor and forbearance, therefore, will be necessary, in order to preserve peace, and promote the public welfare.

It is reasonably expected that our honored Rulers, in the whole of their conduct as legislators, will be governed by the great principles of justice and benevolence; and that every other interest will be subordinated to the public good. That they will enforce by example, what they inculcate by precept.

In all their attempts to aid the interests of morality and religion, great care will be taken not to infringe the rights of conscience. These ought to be held sacred as the prohibited tree in the garden of Eden, and the flaming sword should be employed only to guard the way. What Pindar said of Magistrates, may be applied on the present occasion. “Be just, said he, in all your actions, faithful in all your words, and remember that thousands of witnesses have their eyes upon you.”

Many are the motives to fidelity, but none more weighty than the consideration of future accountability. Under these solemn impressions, our honored Rulers will attend to the important duties of this day, and during their continuance in office. In their most zealous deliberations they will not forget, that “God standeth in the congregation of the mighty, and judgeth among the gods.” May all their public transactions tend to promote the various interests of the Commonwealth; and to strengthen the bonds of our National Union. And after having served their generation according to the will of God, when they shall fall asleep, may they be gathered to their fathers in peace.

Ye venerable Ministers of the Sanctuary; ye servants of the most High God; who show unto men the way of salvation. While our civil rulers, who have invited us this day to the house of God, continue to reverence the institutions of religion, and to respect and honor its ministers; you will not cease daily to offer up intercessions and prayers for all that are in authority. Nor will you cease to “put the people in mind to be subject to principalities and powers, to obey magistrates, and to be ready to every good work.” And may God Almighty bless your unwearied labors of love.

Fellow citizens of this respectable audience. How great, and how precious the privileges we enjoy! While so many of our fellow beings inhabit the dark regions of slavery and despotism; and bow with degrading reverence before some lordly tyrant, who sits upon a throne of ebony, swaying an iron scepter; we have the peculiar felicity to live under a free government. Our rulers are of ourselves, and our governors proceed from the midst of us. When thus cloathed with power, we are bound to honor them as the ministers of God, who exercise their authority not for their own emolument, but for the public good. Let us therefore endeavour to strengthen their hands, by a cordial acquiescence in every measure promotive of our common interest. If we do not protect our laws, our laws will not protect us. By our civil and religious habits let us shew to the world that Americans are worthy of freedom.

Be careful how you entertain unreasonable jealousies and suspicions of your old and long tried friends. But when you hear a man, whose integrity and talents never introduced him to public notice, saying, “Oh that I were made judge in the land;” although his face may be as fair as Absolom’s, you have reason to suspect that there are “seven abominations in his heart.” I feel a persuasion, my fellow citizens, that you are from principle attached to our republican system; and that you would oppose with energy and firmness any attempts to change it. Should any furious demagogue hereafter presume to play the tyrant, and by any unconstitutional measures place himself in the chair of state, should we tamely submit to it? No, the spirit of the American people would rise indignant, and hurl the wretch from his seat, and turn him out to graze as the Chaldeans did Nebuchadnezzar.

Brethren, “you have been called unto liberty, only use not your liberty for an occasion to the flesh, but by love serve one another.” Cherish therefore all those friendly affections which unite man with man, and sweeten the pleasures of social life. Above all things let the gospel of the grace of God rule in your hearts. If you are made free from civil tyranny and oppression, never suffer yourselves to be the slaves of sin. No servitude can be more degrading. But having obtained redemption through the blood of Christ, even the forgiveness of sins, let us “stand fast in the liberty wherewith he hath made us free, and not be entangled again with the yoke of bondage.” And will the God of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Israel; the God of our Fathers, delight to dwell with us and bless us, and be our God now and evermore; Amen.

1.Paley, supposes there never was such a thing as a social compact, strictly speaking, but allows that this comes the nearest of anything to be met with. See also Burgh’s Polit. Disq.

2.See Governor Trumbull’s Speech, at the opening of the Conecticut Assembly in October last.

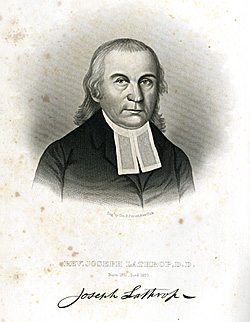

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.