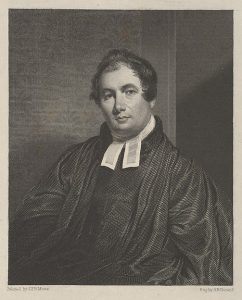

Amos Bassett (1764-1828) graduated from Yale in 1784. He was pastor of a church in Hebron, CT (1794-1824) and in Monroe, CT (1824-1828). This election sermon was preached by Rev. Bassett in Hartford, CT on May 14, 1807.

ADVANTAGES AND MEANS OF UNION

IN SOCIETY.A

SERMON,

PREACHED AT THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

IN

HARTFORD,

May 14th, 1807.

BY AMOS BASSETT, A. M.

Pastor of a Church in Hebron.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, on the second Thursday of May, A. D. 1807.

ORDERED, That the Honorable Henry Champion and Mr. Asaph Trumbull, present the Thanks of this Assembly to the Reverend AMOS BASSETT, for his Sermon preached at the General Election, on the 14th day of May instant, and request a copy thereof, that it may be printed.

A true copy of record,

Examined by

SAMUEL WYLLYS, Secretary.

ELECTION SERMON.PSALM CXXXIII. 1.

Behold how good and how pleasant it is, for

brethren to dwell together in unity!

THIS Psalm, it is thought, was composed and sung on occasion of the reunion of the twelve tribes of Israel after a distressing civil war of eight years. However this may be, it is probable that the inspired author of the pleasing and excellent sentiments contained in it, had on some occasions witnessed the numerous blessings arising from union in society. He had also, without doubt, had frequent opportunities invites them to “behold how good and how pleasant it is, for brethren to dwell together in unity.”

Though the term brethren, in its primary import, is applied to descendants of the same parents; yet, it is also used in the sacred scriptures, and in the general language of mankind, with some variety of signification. While the scriptures treat those as brethren, in the most exalted sense, who, in addition to other bonds of union, possess the holy image of the living God, they call those, also, in a more general sense, brethren, who, from their local situation, ought to consider themselves connected together for mutual benefit, and ought to aim for the promotion of the common good. 1 Of the last description are the members of a neighbourhood—a town—a state—and, indeed, of every civil community however extensive.

Of brethren of every description, and probably there are brethren of all the above descriptions present, it may truly be said, that it is “good and pleasant for them to dwell together in unity.” The favour of your candid attention is therefore requested, while an attempt is made to point out, with special reference to a civil community,

I. Some of the advantages of union among brethren.

II. Means for promoting this union.

I. Some of the advantages of union among brethren.

The union, now contemplated, is very different from a selfish combination of partisans. Such a combination contains the seeds of dissolution within itself. Drawn together at first by self interest and self gratification men may unite for a season. But such cannot, they will not long “dwell together in unity.” The basis of their union is essentially defective. The more they know of each other, the more their mutual jealousy will increase. The same unjustifiable motives that drew them together at first will invariably produce discords and contentions: and wretched is that society which must sustain the conflict.

Nor will this discourse contemplate that union, if anyone choose to call by this name, a mere quiet, enforced by the arm of a despot, who is subject to no law—controlled by no principle of virtue.

What is now advocated is the union of a free people in unfeigned regard for the public good—in benevolent, virtuous affection for each other—and in harmony of sentiment relative to the leading measures which are to direct their public concerns. Where the two first properties of a salutary union prevail, the last will be attained without great difficulty. Erroneous information will not be designedly given. Confidence may be placed in the opinions of the ablest members; and the disinterested, candid and diligent enquirer will be able to ascertain, to a sufficient degree, the men whose superior merit entitles them to promotion.

The advantages to be derived from such an union among brethren are numerous. The first that will be mentioned is peace—peace in society, resulting from the prevalence of pure principles, and from an universal attachment to them. This is among the richest blessings of divine providence. The benevolent Creator, in the promise of good things to be enjoyed in the present life, includes peace, as being one of his greatest favours. Yea, it is one of the blessings which constitute the perfect state of enjoyment in the heavenly world.

Another advantage of this union is strength. The union of a people, in real regard for the common good, powerfully braces and strengthens the public arm. Society can now avail herself of the united talents of her most able and respectable members. Her union presents also a firm and stable bulwark against violence from abroad—a far better defence than artificial mounds and ramparts erected without her walls, while the community within is confused with discord, and distracted with party divisions, frequently more opposed to each other than even to a common enemy. Infinite wisdom has declared “every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation, and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand.” The declaration of the destructive tendency of discord applies with peculiar force to a people enjoying a republican government. How many miserable examples of the truth of this declaration have even our own times produced! They fell—they were brought to desolation, and their enemies divided the spoil; because they were disunited, and of course destitute of strength. Behold, and consider them well: look upon them, and receive instruction.

Again—while “brethren by dwelling together in unity” are thus rendered powerful, another advantage is gained in a consciousness of security, both public and private. This consciousness of security attaches a value of great importance to all their possessions and to all their enjoyments. They tremble not with apprehensions of falling a prey to foreign enemies. Neighbours also, dwell securely by the side of each other.

How much does it abate, and oftentimes, how entirely does it destroy the enjoyment of blessings, to consider that they are entirely insecure from the violence of man? The enjoyment in such a case, is like that of the person mentioned in history, attempting to regale himself at a rich entertainment; but beholding at the same time a sword suspended over his head by a single hair. Need much be said to a considerate people upon this subject?

Who, in surveying and forming an estimate of the blessings with which he is surrounded, would not find his pleasure unspeakably abated did he know that his enjoyment of them was suspended upon the uncertain events of changes and revolutions,–upon the mercy of some foreign tyrant,–or upon the capricious humours and frenzy of irritated partisans. To-day he is surrounded with the dearest friends, and favoured with a tranquil enjoyment of his possessions. To-morrow he is doomed, perhaps, to behold those friends bleeding around him, and those possessions falling a prey to lawless invaders.

Happy is that people, who, “in union, dwell together,” and in security enjoy their liberties and their privileges. Happier still, when favoured by heaven with wisdom to prize, and resolution to preserve them.

Again—in a union thus constituted the pleasures of friendly intercourse are enjoyed in the highest degree. Each one is made happy by beholding the happiness of his neighbour and of the public. Where friendship is cordial and benevolence sincere, the prosperity of a neighbour can be beheld, not only without envy, but with delight. The eye of the beholder will not be evil because divine providence has been good.—nor because the favours of God have been distributed, in that proportion which seemed best to infinite wisdom.

Where even two or three are thus cordially united, in benevolent affection, the pleasure is great. The happiness is increased in proportion as the subjects of this union become numerous. Extend, then, this union, to neighbourhoods, to towns, to a whole community. Contemplate them,–all in harmony—all seeking the public good—all observing the duties of their respective stations—all engaged in offices of mutual kindness, wishing well to each other, counseling, warning, assisting and instructing each other in love. Notice their mutual civilities, their unsuspecting confidence, their numerous charities;–each person taking pleasure in the happiness of others, and endeavouring to his utmost to promote it.

If the mind be truly benevolent, the sight must be highly grateful: and while the heart of the observer expands with sensations of the sincerest joy, he adopts, as his own, the excellent sentiments of this psalm; “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity. It is like the precious ointment,”—(made in those days of the most rich and costly materials)—“like the precious ointment upon the head, that ran down upon the beard, even Aaron’s beard; that went down to the skirts of his garments;” not only refreshing and delighting with its fragrance, the whole assembly that were present; but perfuming the names of the twelve tribes, written upon the garment of Aaron; and representing thereby the advantages that might be derived to the whole nation, from that “unity” which true virtue produces. It is “as the dew of Hermon, and as the dew that descended upon the mountains of Zion.” How different is the origin of this from the origin of discord. This, like the dew, descendeth from heaven. Discord cometh up from beneath, accompanied with hatred, envy, and bitter revenge,–unhallowed, malignant passions, that mingle a portion of gall with the most valuable ingredients of our happiness.

The benefits attached to society are lost, and its enjoyments destroyed, in proportion to the prevalence of the malignant passions. “A fire devoureth before them, and behind them a flame burneth: the land is as the garden of Eden before them, and behind them a desolate wilderness.”

The peaceful and cordial friend of his fellow creatures, deprived now, of the sweet enjoyments which before had rendered society so desirable, and pained to behold the sufferings and wretchedness of those around him, will feelingly adopt the words of the Psalmist, on an occasion very opposite to that which produced the text: “I mourn in my complaint, because of the voice of the enemy, because of the oppression of the wicked. My heart is sore pained within me. Fearfulness and trembling are come upon me, and horror hath overwhelmed me. And I said, O that I had wings like a dove! For then would I flee away and be at rest; I would hasten my escape from the windy storm and tempest.”

The virtuous and upright union of brethren cometh down from heaven. Like the dew that distilled on Hermon and on the mountains of Zion, it is gentle, sweet, and mild in its influence. And, as the dew is most refreshing and fruitful in its effects, causing the earth to “yield her increase, and the bud of the tender herb to spring forth;” so, the seeds of public happiness shall abundantly spring up,–flourish—and issue in a joyful harvest; where “brethren dwell together in unity.” Instead of the thorn, shall come up the fir tree, and instead of the brier, shall come up the myrtle tree; and the happy inhabitants “shall go out with joy and be led forth with peace.”

To cultivate such an union by all proper means, must, surely, be an object worthy the attention of every wise people, and especially of that people who are favoured with a free government. Let the attention, therefore, of the good citizen, be directed,

II. To means for promoting this union.

And here two means present themselves, as being of primary importance, information and virtue.

1. Correct and liberal information is highly to be prized. Great pains ought to be taken to diffuse this, as far as is practicable, among the body of the people; for it deservedly claims a high regard in the public patronage. At the same time it ought not to be forgotten, that, without the prevalence of virtuous principle, the union of a free people cannot be preserved by mere information, however extensive. It is indeed a very valuable price put into the hand of man; but it may and will be abused by a corrupt heart. Extensive knowledge and great abilities, without virtue,–without principle—are dangerous in the extreme. The truth is suggested as necessary to be kept in view in all arrangements made for education; not as an objection against promoting and diffusing knowledge as far as is practicable. The only valid objection is against the abuse. Information is dangerous in the hands of the vicious only. Place it in the hands of a free and virtuous people, and it becomes of immense advantage to them. Hereby they are assisted to understand their privileges—to set a just value upon them—judiciously to defend them—to distinguish between what will contribute to preserve, and what will tend to destroy them—and to have a correct discernment of characters qualified to be their rulers.

Let information, then, be extended to every class of the community, by all proper means, and especially by the institution of schools and seminaries of learning, and let them receive the liberal patronage of government.

And further, as it is of indispensable importance that information be connected with virtue, and as youth are almost the only persons who are members of these institutions, it becomes peculiarly necessary that the instructors who are to superintend them be cautiously chosen. Our children are our hope and our joy. Whoever is engaged in corrupting their minds is doing them and us an injury which he can never repair. A person of vicious conduct, and who is zealously engaged in disseminating principles which tend to vice, is clearly disqualified to be a teacher of youth, whatever may be his learning.

Many are the unhappy dupes of vicious artifice, even among those who are arrived at manhood. Much more are youth liable to imposition. It is not difficult for an artful man to take advantage of their inexperienced years—to avail himself of the prevalence of passion in that early period of life—and, instead of giving them just ideas of what is practicable, and consistent with the being of well ordered society, to bloat them with pride, and excite in them an extravagant ambition. It is not difficult, by fostering their irregular propensities, to fill them with an impatience of control, to persuade them to despise the restrictions of moral virtue, and to engage them in a warfare against every wholesome and necessary restraint.

But, to do thus, is to train up a generation for slavery here, and perdition hereafter. Should our youth become thoroughly and generally abandoned,–should the gratification of vicious propensities become their supreme object—what can be expected from them in manhood? Will they hesitate to sell themselves and the liberties of their country for their favourite indulgences? No. The spirit of a people abandoned to vice is the spirit of slaves. While, as individuals, they are tyrannical to those who are under them, they can easily cringe and fawn around a despot without any material change of feeling.

Is a government attempting to promote the public union and happiness by means of schools and colleges? Let them not destroy with one hand what they attempt to build up with the other.

To improve the minds of your children by correct and useful information, is to do them an immense favour; but to confirm them in principles of virtue, is to do them a favour unspeakably greater: unite them both, and you bequeath to them the richest inheritance. When you are about to depart from the state of action, and to be gathered to your fathers, you may bid them adieu, with the pleasing prospect that they will be free and happy.

2. In every advance that is made in illustrating the subject under consideration, the essential importance of virtue becomes more and more evident.

The past and present experience of mankind authorizes the declaration, that virtue, including that morality which is the fruit of it, is the only sure and permanent bond of public union. Banish this from a people, and the blessings of union and freedom depart with it. It is impossible that the tranquility of a vicious people should be preserved long, except by means which will destroy their liberty.

Are any disposed to call this in question? They are requested, candidly to compare the nature and effects, both of virtue and vice, with the valuable objects of a free government. Are they still unsatisfied, and, at the same time, free from a criminal bias upon their minds? Let them next repair to history, sacred and profane, and they must be effectually convinced, that vice is the reproach and ruin of a people—that it alienates their affections from the public good—and tends to discord with all its train of miseries.

Virtue—living, operative virtue, which always includes pure morals, has such a decided influence in promoting “unity among brethren,” that it merits a further and more particular consideration.

A view will now be taken,–first, of the influence of morals,–secondly, of the nature of that virtue which will produce and preserve them.

(1.) Of the influence of morals. A practical view is now designed, which will be contrasted with a view of the tendency of their opposite vices.

Upon every good citizen, a conviction of the importance of morals to the welfare of his country, as well as motives of a higher consideration, will have a practical influence. In all his intercourse with society, he will maintain truth and integrity. He will take heed that he offend not against truth or justice with his tongue. This member, under the influence of an envious and malicious heart, frequently becomes “a fire, a world of iniquity. It setteth on fire the course of nature, and is set on fire of hell. It is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison. Behold how great a matter a little fire kindleth.” By malicious falsehoods, the nearest friends are often set at variance, and the most peaceable neighbourhoods are distracted with contentions. Envy and strife are excited: and “where envy and strife are, there is confusion and every evil work.” The fairest character cannot escape, and the most undeviating rectitude cannot shield the citizen, when envy and ambition aim their darts at him secretly.

In all the dealings of men with each other—in the transaction of every kind of business, let the same regard to truth and integrity be maintained. Thus, neighbours may “dwell together in unity.” Peaceful and secure, they will put confidence in the declarations and engagements of each other.

As in private intercourse, so, especially, in public communications, a sacred regard ought ever to be had to integrity. That man who has the public good at heart, will see, that all his communications are founded on truth. The means will be consistent with the motive. To practice deceit, by design, in information professedly given to the public, is to embarrass the public mind; and, so far, to deprive a people of the means of their security. Such conduct may proceed from a variety of motives; but it can never be dictated by a regard to the common welfare. It is an insult offered to the public, which deserves to be reprobated by every upright man.

Further—The true patriot, who wishes to preserve purity of morals, and, by means of them, to share in the union and happiness of a free people, ought carefully to guard against party spirit. Party spirit and discord are plainly the same; and whoever imbibes and indulges this spirit subjects himself to many dangerous temptations. This spirit never fails to injure the morals of a people. Passions of the most dangerous kind obtain the ascendency over reason, and the moral sense is gradually weakened;–the moral sense—which ought ever to be feelingly alive to the essential difference between virtue and vice. Destroy this, and you reduce the public body to a wretched mass of corruption. No longer will such a people experience, under a free government, “how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.” They cannot dwell together at all, without some government; and for forlorn expedient must now be a despotism. There are but two ways in which order is preserved among mankind, when they “dwell together.” The one is principle—the other is force. In proportion as the former prevails, the latter becomes unnecessary. Extinguish the former, and the latter must be applied in the fullest degree.

FURTHER—A temperate, yet faithful execution of the laws enacted for the suppression of vice and the preservation of order, is of great importance as a guard to the morals of a people. The best regulated society is liable to be disturbed by individuals who have not moral principle to restrain them from crimes injurious to themselves, destructive to moral and civil order, and, of course, subversive of the public union, peace and security. Law and government therefore become indispensably necessary. They are ordained by that Being who is perfectly acquainted with the state and dangers of our race. He has pointed out the objects of them,–and also, those qualifications which he requires civil officers to possess. Such officers, if they are faithful to God and man, will see that the laws are executed for the suppression of vice. The “oath of God is upon them;” they will endeavour to be “ministers of God for good” to society.

WHAT, then, shall be thought of the fidelity of civil officers, in places where Sabbath-breaking and riotous collections are publicly known, and yet meet with no legal censure? What of their fidelity, who by improper forbearance, give countenance to places employed as retreats for intemperance and various species of disorder? To pass by such places and not censure them is to sanction them.

You will suffer yourselves, in this place to be detained for a moment, by some remarks on the excessive use of spirituous liquors—an alarming, and, in some places, it is to be feared a growing evil; and that which needs the correction of executive authority. A great part of what is consumed is, in particular instances, worse than thrown away. Through the frantic influence of these spirits, rational beings are transformed into furies,–the peace of society is broken, and many crimes are wantonly committed. To procure this liquid poison, families of the poor are deprived of their necessary food and clothing; and not a season passes, in which many victims of intemperance are not registered in the bills of mortality. The excessive use is indeed confined to comparatively few, and therefore it is less impracticable to prevent it. There is no necessity of suffering individuals to consume, annually, from 50 to 70, and perhaps an hundred gallons of ardent spirits. Let the civil officer appointed to take cognizance of this, as well as of other crimes,–when he attends one and another of these wretched victims to their graves, lay his hand upon his heart, and be able to declare, as in the solemn presence of God, “I have done my duty,–I am free from the blood of this man.” Let retailers of spirits, and keepers of public houses be able, also, to make the same declaration.

FURTHER—among the things favourable to morals may be reckoned industry.

PERSONS engaged in some reputable, industrious calling, endeavouring to “provide things honest in the sight of all men,” are found, more usually than the idle, to be friends of morality and order. They have property to be protected. They wish for that security which is attached to union in society where all are engaged in seeking the public good.

A STATE of idleness, on the contrary, exposes to many temptations. It tends to extravagant expense—to poverty—to discontent—to envying others, and coveting their possessions—and, in many instances, to that turbulent conduct which endangers the public welfare.

The view, which has now been taken of the opposite tendencies of morality and vice, is thought sufficient to furnish decisive evidence of the importance of the former, as a means of union in society.

The inference is obvious. A wise republic will guard the morals of her citizens with the most assiduous care. No labour or expense, requisite to guard these, will be deemed too great, no watchfulness too strict; fully convinced, that to neglect or abandon them is to give up the public happiness, and to render insecure every valuable blessing of social life. She will take heed, also, that the same sentiment does feelingly and practically evade every branch of her government.

Apprized of the almost unbounded influence of the examples and sentiments of men in public stations, she will watch over her elections with a jealous eye, and guard against bribery, corruption and intrigue with persevering zeal. Knowing that the progress of degeneracy among a people, once virtuous, is commonly gradual, proceeding from small beginnings at first; she will “look diligently, lest any root of bitterness, springing up,” spread its malignant influence, till “many be defiled” With her, it will be a first principle, sealed with her seal, a principle which no man, on any pretence, may reverse; that all those who are elevated to public and important stations must be men of sound, approved virtue.

It becomes important to ascertain, as was proposed,

(2.) The nature of that virtue which will effectually produce and preserve morals.

It is here desirable to obtain a true description comprising the whole of virtue, in principle as well as practice. To neglect this, in the consideration of the present subject, would occasion a material defect. It is also desirable and necessary to find, if possible, a system of religion, which not only speaks of morals; but effectually influences mankind to practice them. Where then is this to be found? Shall we go to the heathen moralists? They have, indeed, written many valuable truths relating to virtue and morals; but they have failed in essential things: they cannot furnish what is now sought. Shall we repair to the modern infidel philosophy? The world has already tried enough of the bitter fruits of this philosophy to ascertain the nature of the tree. The wretched situation of those nations, who have “experimented” on the principles of this philosophy, forbids us to adopt it. Turn your eyes to these nations. The principles of Voltaire preceded the destruction and misery in which they are now involved. “Hath not God made foolish the wisdom of this world?” Do they experience, in the enjoyment of the blessings of freedom and happiness, “how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity?” Far from it. “Destruction and death can only say, we have heard the same thereof with our ears.” That Being who alone possesses infinite benevolence and unerring wisdom has put into our hands “a sure word,” comprising a complete and perfect system of moral virtue,–including everything that is now sought—and accompanied with “promise of the life that now is, and of that which is to come.”

As it has been much disputed by some whether it is of advantage to civil government to patronize the Christian religion; the subject under consideration authorizes me to state some of the first principles of this religion, that it may be seen how far they comport with the justifiable objects of a civil community.

The existence and perfections of God are at the foundation of all true virtue. Begin, then, with the character of the Deity. This religion reveals to us a Deity rendered glorious and perfect by such attributes as commend themselves to every enlightened conscience. Infinitely just, holy, wise, powerful, merciful and faithful, he is necessarily the unchangeable friend of virtue, and the determinate enemy of vice.

It is, surely desirable to know the original cause of the vices and distresses of the nations. The sacred scriptures point it out. It is the apostacy of our race from God.

In the same scriptures, a law of moral virtue is stated to us, which, in its strictness and purity, resembles God. Holy, just, and good, it leaves not to every man to say what is virtue and what is vice, but both, as will presently appear, are truly and accurately defined.

No vicious propensities are fostered by this law or palliated. The pride of no person whatever, high or low, is flattered with any prospect, that it will or can be abated, in the least, on his behalf. But, a way is revealed in which God can be just and yet justify the penitent and reformed sinner, thro’ faith in Jesus Christ the son of the Highest who, by becoming a sin offering, has magnified the law and made it honourable. Thus, the divine law is supported, and moral virtue secured.

Not only does this religion shew to man the origin and nature of his moral disorder, but, different from all other religions, it makes effectual provisions for his cure, in a radical and total change of heart. In this change, “a new creature” is formed, by the power of the Holy Ghost, and a thorough, permanent principle of moral virtue is given. Men are “created unto good works,”—formed to act with fidelity in every situation of life.

This religion having thus formed men for moral virtue, proceeds to furnish them with instructions relative to duty in every condition of life. The law of God is continually placed before them, for their study and practice. A summary of it is given in these words, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength:–and—Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thy self.” This is true virtue. A transgression of this law is sin,–is vice.

This summary, so far as is necessary, is traced out into its several branches. The disciple of Christ is taught to “deny ungodliness and worldly lusts; and to live soberly, righteously, and godly:” soberly, as it respects personal duty, exercising temperance, modesty and humility;–righteously, in his intercourse with his neighbour, “doing to others as he would that they should do to him;”—and godly in his treatment of the Deity, honoring him in all his institutions, and having a supreme regard to his glory in every transaction of life.

The religion of the Bible commands the public worship of the Deity. It enjoins the observation of the Sabbath, and, on this holy day, it forms a public school of moral virtue. While men stand in the holy presence of their Creator, a sense of his attributes is awakened,–they are reminded that they must be like him,–that they must “love one another, and live in peace.”

Men are taught, by this religion, their duty, in all their relative stations. The ruler finds his duty pointed out,–the subject finds his. The ruler is taught that he is to be a “minister of God,”—sent by him to be a “terror to evil doers and a praise of them who do well.” The subject is taught “to obey magistrates, and to submit to every ordinance of their appointment for the Lord’s sake.” If the citizen be favoured with the privilege of electing his rulers, the characters to be chosen are plainly pointed out to him. They are to be “just men, men of truth, haters of covetousness, fearers of God.” In the important transaction of choosing a ruler, the person cannot disregard the “oath of God” and be guiltless; for, even in the common concerns of life, he is not to abandon religious principle, but “whatever he does, is all to be done to the glory of God.”

Masters and servants—husbands and wives—parents and children—all find appropriate directions, relative to the duties of their respective stations. Every vice is condemned. Every social virtue is enjoined.

The religion communicated in the sacred scriptures having taught men that in this life they form their characters, and fix their destination for eternity, places before them the eternal retributions. Nothing can be so dreadful as the punishments that will assuredly be inflicted upon the vicious,–nothing so glorious as the rewards that will be bestowed upon the virtuous. They both infinitely exceed all that human laws can pretend to. The laws of Christ extend to every motive of action. They take cognizance of crimes which neither the law nor the eye of man can reach. They enjoin many acts of kindness and humanity which are not to be known till “the resurrection of the just.” They follow the workers of iniquity into every place of darkness where they may attempt to screen themselves from human view; assuring them that they are “naked and opened” to the penetrating eye of an almighty avenger, always present, always noticing their conduct for the purpose of a future judgment,–thus “placing by the side” of every crime an adequate and certain punishment.

To the consciences, and not to the passions of my audience is the appeal now made. Cannot this religion be of service to civil government?—In the consequence of every intelligent hearer, the answer is ready,–and it is the same.

Let it be added, that the period is advancing when there shall be the fullest display of the salutary influence of this holy religion upon civil government. “The kingdoms of this world shall become the kingdoms of the Lord and of his Christ: for the mouth of the Lord of hosts hath spoken it.”

Previous to this period, there are to be dreadful desolations in the earth; men having, by their great wickedness, become ripe for the execution of divine vengeance. These desolations are signified to us in scripture by the representation of “an angel standing in the sun, crying with a loud voice, and saying to all the fowls that fly in the midst of heaven, Come and gather yourselves together unto the supper of the great God; that ye may eat the flesh of kings, and the flesh of captains, and the flesh of mighty men, and the flesh of horses, and of them that sit on them, and the flesh of all men both free and bond, both small and great.”

If the time referred to in this representation be now commenced, the next important event will be the binding of Satan, and the ushering in of the millennial day.

“Behold, I come as a thief,” saith the glorious judge. A careless, unbelieving world will not know his judgments, nor consider the operation of his hand, in the passing events.

Blessed are those servants, of all descriptions, who watch, and are found, of their Lord, faithfully performing the duties of their respective stations.

Civil Rulers, exalted in the providence of God to decree and administer justice, will feel themselves addressed by the subject. While they bestow due praise upon those who do well, they will be a terror to evil works.

Duly impressed, also, with a sense of their obligations to the most High, they will adorn their honourable stations by “adorning the doctrine of God their Saviour.”

The Lord commanded the ruler of his people to pay great attention to the divine law. “It shall be with him,” saith the command, “and he shall read therein all the days of his life; that he may learn to fear the Lord his God; that his heart be not lifted up above his brethren; and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand or to the left.”

The same general reasons for cultivating an intimate acquaintance with the word of God must ever exist. The commandment of the Lord is pure, enlightening the eyes.”

“God is not a respecter of persons,” but of moral character. May the honoured and respected rulers of this state, ever be influenced by the most High, to honour him, and become blessings to his people, by maintaining a religious, firm, upright deportment. “Them that honour me I will honour,” saith the Lord.

Ministers of the gospel are reminded, by the subject under consideration, of the duties, which they, in their proper spheres, are required to perform to God, to their country, and to the souls of men.

When we engaged in the sacred office, my brethren, though we did not give up our rights as citizens, yet the chief employment assigned to us was to promote virtue, and bear testimony against sin. We are to beseech men, in Christ’s stead, to be reconciled to God. We are also to bear testimony against sin. When the voice of every friend of God, and of mankind ought to be lifted up against the vices that destroy the peace of society and the souls of men, let us not keep undue silence.

It is our acknowledged duty also, continually to intercede with the Most High for our common country, and for the churches of the Saviour, that he would “spare his people and not give his heritage to reproach.”

If we may be the happy instruments of promoting that love to God and man, and that pure morality which the gospel of our Lord and Saviour enjoins, we shall do an essential service, not only to the souls of men, but also to our country.

The chief design of the gospel is to fit men for the eternal enjoyment of God in heaven. And, in doing this, it necessarily enforces those principles and that conduct in the present life, which cannot fail to produce the most benign effect on civil society. The great duty of love or charity which the gospel enjoins is the strongest bond of union in society of any that can be named. Short is the period of duty in the present world. The recent and numerous deaths 2 of our brethren in the ministry remind us that “the time is short.” Let us “give all diligence in making full proof of our ministry. There is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom in the grave.”

The Freemen of the State have also a real and important interest in considering and understanding the subject suggested by the text. God has entrusted with you, fellow-citizens, the protection of your rights and privileges. Be thankful to him for the favour. Let no flattery entice, nor the gratification of any sordid passion allure you to part with the sacred deposite. Rising superior to every partial and degrading motive, and looking steadily at the common good, labour to strengthen the bonds of that “unity,” which causes it to be “good and pleasant for brethren to dwell together.” Virtuous principle is the basis of your government and must be the pledge of your security.

God, through the influence of his religion, has blessed your native state with a very high degree of prosperity, for more than a century and a half. Is not this a sufficient proof of the excellency of the plan on which the settlement was formed? “Consider the years of many generations: ask thy father, and he will shew thee, thy elders, and they will tell thee.”

It is not a vain thing to preserve your institutions,–“it is your life.”

“I beseech you in Christ’s stead, Be ye reconciled to God.” Bring up your children for him. Let their minds be enriched with knowledge, and their hearts with the love of their Creator. Labour to secure, for yourselves and for them, the protection of the Almighty; and you need not fear. Your enemies, however numerous, shall not overwhelm you; if the Lord do not deliver you over into their hands.

From the very beginning of the settlement of this state, to the present day, Jehovah has been acknowledged by the people, and by the government, as their “strength, their refuge, their deliverer, and the horn of their salvation.” Still do both appear openly on the side of Christ, and publicly patronize his cause.

This anniversary reminds us all of our obligations to praise and bless the God of our fathers, who “sheweth mercy unto the thousandth generation, of them that fear him and keep his commandments.”

Appearing, this day, as his messenger, in the revered and beloved assembly of the Governors, the Counselors, the Representatives and the Judges of this free and happy republic; and uniting in my wishes with my brethren the ministers of the Saviour; I close, in conformity to the tenor of this discourse, by “putting the name” of Jehovah, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, upon this assembly, as including the sum of all blessings.

“The LORD bless thee and keep thee: The LORD make his face to shine upon thee and be gracious unto thee: The LORD lift up his countenance upon thee, and give thee peace.”

AMEN.

Endnotes

Amos Bassett (1764-1828) graduated from Yale in 1784. He was pastor of a church in Hebron, CT (1794-1824) and in Monroe, CT (1824-1828). This election sermon was preached by Rev. Bassett in Hartford, CT on May 14, 1807.

ADVANTAGES AND MEANS OF UNION

IN SOCIETY.A

SERMON,

PREACHED AT THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

IN

HARTFORD,

May 14th, 1807.

BY AMOS BASSETT, A. M.

Pastor of a Church in Hebron.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, on the second Thursday of May, A. D. 1807.

ORDERED, That the Honorable Henry Champion and Mr. Asaph Trumbull, present the Thanks of this Assembly to the Reverend AMOS BASSETT, for his Sermon preached at the General Election, on the 14th day of May instant, and request a copy thereof, that it may be printed.

A true copy of record,

Examined by

SAMUEL WYLLYS, Secretary.

ELECTION SERMON.

PSALM CXXXIII. 1.

Behold how good and how pleasant it is, for

brethren to dwell together in unity!

THIS Psalm, it is thought, was composed and sung on occasion of the reunion of the twelve tribes of Israel after a distressing civil war of eight years. However this may be, it is probable that the inspired author of the pleasing and excellent sentiments contained in it, had on some occasions witnessed the numerous blessings arising from union in society. He had also, without doubt, had frequent opportunities invites them to “behold how good and how pleasant it is, for brethren to dwell together in unity.”

Though the term brethren, in its primary import, is applied to descendants of the same parents; yet, it is also used in the sacred scriptures, and in the general language of mankind, with some variety of signification. While the scriptures treat those as brethren, in the most exalted sense, who, in addition to other bonds of union, possess the holy image of the living God, they call those, also, in a more general sense, brethren, who, from their local situation, ought to consider themselves connected together for mutual benefit, and ought to aim for the promotion of the common good. 1 Of the last description are the members of a neighbourhood—a town—a state—and, indeed, of every civil community however extensive.

Of brethren of every description, and probably there are brethren of all the above descriptions present, it may truly be said, that it is “good and pleasant for them to dwell together in unity.” The favour of your candid attention is therefore requested, while an attempt is made to point out, with special reference to a civil community,

I. Some of the advantages of union among brethren.

II. Means for promoting this union.

I. Some of the advantages of union among brethren.

The union, now contemplated, is very different from a selfish combination of partisans. Such a combination contains the seeds of dissolution within itself. Drawn together at first by self interest and self gratification men may unite for a season. But such cannot, they will not long “dwell together in unity.” The basis of their union is essentially defective. The more they know of each other, the more their mutual jealousy will increase. The same unjustifiable motives that drew them together at first will invariably produce discords and contentions: and wretched is that society which must sustain the conflict.

Nor will this discourse contemplate that union, if anyone choose to call by this name, a mere quiet, enforced by the arm of a despot, who is subject to no law—controlled by no principle of virtue.

What is now advocated is the union of a free people in unfeigned regard for the public good—in benevolent, virtuous affection for each other—and in harmony of sentiment relative to the leading measures which are to direct their public concerns. Where the two first properties of a salutary union prevail, the last will be attained without great difficulty. Erroneous information will not be designedly given. Confidence may be placed in the opinions of the ablest members; and the disinterested, candid and diligent enquirer will be able to ascertain, to a sufficient degree, the men whose superior merit entitles them to promotion.

The advantages to be derived from such an union among brethren are numerous. The first that will be mentioned is peace—peace in society, resulting from the prevalence of pure principles, and from an universal attachment to them. This is among the richest blessings of divine providence. The benevolent Creator, in the promise of good things to be enjoyed in the present life, includes peace, as being one of his greatest favours. Yea, it is one of the blessings which constitute the perfect state of enjoyment in the heavenly world.

Another advantage of this union is strength. The union of a people, in real regard for the common good, powerfully braces and strengthens the public arm. Society can now avail herself of the united talents of her most able and respectable members. Her union presents also a firm and stable bulwark against violence from abroad—a far better defence than artificial mounds and ramparts erected without her walls, while the community within is confused with discord, and distracted with party divisions, frequently more opposed to each other than even to a common enemy. Infinite wisdom has declared “every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation, and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand.” The declaration of the destructive tendency of discord applies with peculiar force to a people enjoying a republican government. How many miserable examples of the truth of this declaration have even our own times produced! They fell—they were brought to desolation, and their enemies divided the spoil; because they were disunited, and of course destitute of strength. Behold, and consider them well: look upon them, and receive instruction.

Again—while “brethren by dwelling together in unity” are thus rendered powerful, another advantage is gained in a consciousness of security, both public and private. This consciousness of security attaches a value of great importance to all their possessions and to all their enjoyments. They tremble not with apprehensions of falling a prey to foreign enemies. Neighbours also, dwell securely by the side of each other.

How much does it abate, and oftentimes, how entirely does it destroy the enjoyment of blessings, to consider that they are entirely insecure from the violence of man? The enjoyment in such a case, is like that of the person mentioned in history, attempting to regale himself at a rich entertainment; but beholding at the same time a sword suspended over his head by a single hair. Need much be said to a considerate people upon this subject?

Who, in surveying and forming an estimate of the blessings with which he is surrounded, would not find his pleasure unspeakably abated did he know that his enjoyment of them was suspended upon the uncertain events of changes and revolutions,–upon the mercy of some foreign tyrant,–or upon the capricious humours and frenzy of irritated partisans. To-day he is surrounded with the dearest friends, and favoured with a tranquil enjoyment of his possessions. To-morrow he is doomed, perhaps, to behold those friends bleeding around him, and those possessions falling a prey to lawless invaders.

Happy is that people, who, “in union, dwell together,” and in security enjoy their liberties and their privileges. Happier still, when favoured by heaven with wisdom to prize, and resolution to preserve them.

Again—in a union thus constituted the pleasures of friendly intercourse are enjoyed in the highest degree. Each one is made happy by beholding the happiness of his neighbour and of the public. Where friendship is cordial and benevolence sincere, the prosperity of a neighbour can be beheld, not only without envy, but with delight. The eye of the beholder will not be evil because divine providence has been good.—nor because the favours of God have been distributed, in that proportion which seemed best to infinite wisdom.

Where even two or three are thus cordially united, in benevolent affection, the pleasure is great. The happiness is increased in proportion as the subjects of this union become numerous. Extend, then, this union, to neighbourhoods, to towns, to a whole community. Contemplate them,–all in harmony—all seeking the public good—all observing the duties of their respective stations—all engaged in offices of mutual kindness, wishing well to each other, counseling, warning, assisting and instructing each other in love. Notice their mutual civilities, their unsuspecting confidence, their numerous charities;–each person taking pleasure in the happiness of others, and endeavouring to his utmost to promote it.

If the mind be truly benevolent, the sight must be highly grateful: and while the heart of the observer expands with sensations of the sincerest joy, he adopts, as his own, the excellent sentiments of this psalm; “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity. It is like the precious ointment,”—(made in those days of the most rich and costly materials)—“like the precious ointment upon the head, that ran down upon the beard, even Aaron’s beard; that went down to the skirts of his garments;” not only refreshing and delighting with its fragrance, the whole assembly that were present; but perfuming the names of the twelve tribes, written upon the garment of Aaron; and representing thereby the advantages that might be derived to the whole nation, from that “unity” which true virtue produces. It is “as the dew of Hermon, and as the dew that descended upon the mountains of Zion.” How different is the origin of this from the origin of discord. This, like the dew, descendeth from heaven. Discord cometh up from beneath, accompanied with hatred, envy, and bitter revenge,–unhallowed, malignant passions, that mingle a portion of gall with the most valuable ingredients of our happiness.

The benefits attached to society are lost, and its enjoyments destroyed, in proportion to the prevalence of the malignant passions. “A fire devoureth before them, and behind them a flame burneth: the land is as the garden of Eden before them, and behind them a desolate wilderness.”

The peaceful and cordial friend of his fellow creatures, deprived now, of the sweet enjoyments which before had rendered society so desirable, and pained to behold the sufferings and wretchedness of those around him, will feelingly adopt the words of the Psalmist, on an occasion very opposite to that which produced the text: “I mourn in my complaint, because of the voice of the enemy, because of the oppression of the wicked. My heart is sore pained within me. Fearfulness and trembling are come upon me, and horror hath overwhelmed me. And I said, O that I had wings like a dove! For then would I flee away and be at rest; I would hasten my escape from the windy storm and tempest.”

The virtuous and upright union of brethren cometh down from heaven. Like the dew that distilled on Hermon and on the mountains of Zion, it is gentle, sweet, and mild in its influence. And, as the dew is most refreshing and fruitful in its effects, causing the earth to “yield her increase, and the bud of the tender herb to spring forth;” so, the seeds of public happiness shall abundantly spring up,–flourish—and issue in a joyful harvest; where “brethren dwell together in unity.” Instead of the thorn, shall come up the fir tree, and instead of the brier, shall come up the myrtle tree; and the happy inhabitants “shall go out with joy and be led forth with peace.”

To cultivate such an union by all proper means, must, surely, be an object worthy the attention of every wise people, and especially of that people who are favoured with a free government. Let the attention, therefore, of the good citizen, be directed,

II. To means for promoting this union.

And here two means present themselves, as being of primary importance, information and virtue.

1. Correct and liberal information is highly to be prized. Great pains ought to be taken to diffuse this, as far as is practicable, among the body of the people; for it deservedly claims a high regard in the public patronage. At the same time it ought not to be forgotten, that, without the prevalence of virtuous principle, the union of a free people cannot be preserved by mere information, however extensive. It is indeed a very valuable price put into the hand of man; but it may and will be abused by a corrupt heart. Extensive knowledge and great abilities, without virtue,–without principle—are dangerous in the extreme. The truth is suggested as necessary to be kept in view in all arrangements made for education; not as an objection against promoting and diffusing knowledge as far as is practicable. The only valid objection is against the abuse. Information is dangerous in the hands of the vicious only. Place it in the hands of a free and virtuous people, and it becomes of immense advantage to them. Hereby they are assisted to understand their privileges—to set a just value upon them—judiciously to defend them—to distinguish between what will contribute to preserve, and what will tend to destroy them—and to have a correct discernment of characters qualified to be their rulers.

Let information, then, be extended to every class of the community, by all proper means, and especially by the institution of schools and seminaries of learning, and let them receive the liberal patronage of government.

And further, as it is of indispensable importance that information be connected with virtue, and as youth are almost the only persons who are members of these institutions, it becomes peculiarly necessary that the instructors who are to superintend them be cautiously chosen. Our children are our hope and our joy. Whoever is engaged in corrupting their minds is doing them and us an injury which he can never repair. A person of vicious conduct, and who is zealously engaged in disseminating principles which tend to vice, is clearly disqualified to be a teacher of youth, whatever may be his learning.

Many are the unhappy dupes of vicious artifice, even among those who are arrived at manhood. Much more are youth liable to imposition. It is not difficult for an artful man to take advantage of their inexperienced years—to avail himself of the prevalence of passion in that early period of life—and, instead of giving them just ideas of what is practicable, and consistent with the being of well ordered society, to bloat them with pride, and excite in them an extravagant ambition. It is not difficult, by fostering their irregular propensities, to fill them with an impatience of control, to persuade them to despise the restrictions of moral virtue, and to engage them in a warfare against every wholesome and necessary restraint.

But, to do thus, is to train up a generation for slavery here, and perdition hereafter. Should our youth become thoroughly and generally abandoned,–should the gratification of vicious propensities become their supreme object—what can be expected from them in manhood? Will they hesitate to sell themselves and the liberties of their country for their favourite indulgences? No. The spirit of a people abandoned to vice is the spirit of slaves. While, as individuals, they are tyrannical to those who are under them, they can easily cringe and fawn around a despot without any material change of feeling.

Is a government attempting to promote the public union and happiness by means of schools and colleges? Let them not destroy with one hand what they attempt to build up with the other.

To improve the minds of your children by correct and useful information, is to do them an immense favour; but to confirm them in principles of virtue, is to do them a favour unspeakably greater: unite them both, and you bequeath to them the richest inheritance. When you are about to depart from the state of action, and to be gathered to your fathers, you may bid them adieu, with the pleasing prospect that they will be free and happy.

2. In every advance that is made in illustrating the subject under consideration, the essential importance of virtue becomes more and more evident.

The past and present experience of mankind authorizes the declaration, that virtue, including that morality which is the fruit of it, is the only sure and permanent bond of public union. Banish this from a people, and the blessings of union and freedom depart with it. It is impossible that the tranquility of a vicious people should be preserved long, except by means which will destroy their liberty.

Are any disposed to call this in question? They are requested, candidly to compare the nature and effects, both of virtue and vice, with the valuable objects of a free government. Are they still unsatisfied, and, at the same time, free from a criminal bias upon their minds? Let them next repair to history, sacred and profane, and they must be effectually convinced, that vice is the reproach and ruin of a people—that it alienates their affections from the public good—and tends to discord with all its train of miseries.

Virtue—living, operative virtue, which always includes pure morals, has such a decided influence in promoting “unity among brethren,” that it merits a further and more particular consideration.

A view will now be taken,–first, of the influence of morals,–secondly, of the nature of that virtue which will produce and preserve them.

(1.) Of the influence of morals. A practical view is now designed, which will be contrasted with a view of the tendency of their opposite vices.

Upon every good citizen, a conviction of the importance of morals to the welfare of his country, as well as motives of a higher consideration, will have a practical influence. In all his intercourse with society, he will maintain truth and integrity. He will take heed that he offend not against truth or justice with his tongue. This member, under the influence of an envious and malicious heart, frequently becomes “a fire, a world of iniquity. It setteth on fire the course of nature, and is set on fire of hell. It is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison. Behold how great a matter a little fire kindleth.” By malicious falsehoods, the nearest friends are often set at variance, and the most peaceable neighbourhoods are distracted with contentions. Envy and strife are excited: and “where envy and strife are, there is confusion and every evil work.” The fairest character cannot escape, and the most undeviating rectitude cannot shield the citizen, when envy and ambition aim their darts at him secretly.

In all the dealings of men with each other—in the transaction of every kind of business, let the same regard to truth and integrity be maintained. Thus, neighbours may “dwell together in unity.” Peaceful and secure, they will put confidence in the declarations and engagements of each other.

As in private intercourse, so, especially, in public communications, a sacred regard ought ever to be had to integrity. That man who has the public good at heart, will see, that all his communications are founded on truth. The means will be consistent with the motive. To practice deceit, by design, in information professedly given to the public, is to embarrass the public mind; and, so far, to deprive a people of the means of their security. Such conduct may proceed from a variety of motives; but it can never be dictated by a regard to the common welfare. It is an insult offered to the public, which deserves to be reprobated by every upright man.

Further—The true patriot, who wishes to preserve purity of morals, and, by means of them, to share in the union and happiness of a free people, ought carefully to guard against party spirit. Party spirit and discord are plainly the same; and whoever imbibes and indulges this spirit subjects himself to many dangerous temptations. This spirit never fails to injure the morals of a people. Passions of the most dangerous kind obtain the ascendency over reason, and the moral sense is gradually weakened;–the moral sense—which ought ever to be feelingly alive to the essential difference between virtue and vice. Destroy this, and you reduce the public body to a wretched mass of corruption. No longer will such a people experience, under a free government, “how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.” They cannot dwell together at all, without some government; and for forlorn expedient must now be a despotism. There are but two ways in which order is preserved among mankind, when they “dwell together.” The one is principle—the other is force. In proportion as the former prevails, the latter becomes unnecessary. Extinguish the former, and the latter must be applied in the fullest degree.

FURTHER—A temperate, yet faithful execution of the laws enacted for the suppression of vice and the preservation of order, is of great importance as a guard to the morals of a people. The best regulated society is liable to be disturbed by individuals who have not moral principle to restrain them from crimes injurious to themselves, destructive to moral and civil order, and, of course, subversive of the public union, peace and security. Law and government therefore become indispensably necessary. They are ordained by that Being who is perfectly acquainted with the state and dangers of our race. He has pointed out the objects of them,–and also, those qualifications which he requires civil officers to possess. Such officers, if they are faithful to God and man, will see that the laws are executed for the suppression of vice. The “oath of God is upon them;” they will endeavour to be “ministers of God for good” to society.

WHAT, then, shall be thought of the fidelity of civil officers, in places where Sabbath-breaking and riotous collections are publicly known, and yet meet with no legal censure? What of their fidelity, who by improper forbearance, give countenance to places employed as retreats for intemperance and various species of disorder? To pass by such places and not censure them is to sanction them.

You will suffer yourselves, in this place to be detained for a moment, by some remarks on the excessive use of spirituous liquors—an alarming, and, in some places, it is to be feared a growing evil; and that which needs the correction of executive authority. A great part of what is consumed is, in particular instances, worse than thrown away. Through the frantic influence of these spirits, rational beings are transformed into furies,–the peace of society is broken, and many crimes are wantonly committed. To procure this liquid poison, families of the poor are deprived of their necessary food and clothing; and not a season passes, in which many victims of intemperance are not registered in the bills of mortality. The excessive use is indeed confined to comparatively few, and therefore it is less impracticable to prevent it. There is no necessity of suffering individuals to consume, annually, from 50 to 70, and perhaps an hundred gallons of ardent spirits. Let the civil officer appointed to take cognizance of this, as well as of other crimes,–when he attends one and another of these wretched victims to their graves, lay his hand upon his heart, and be able to declare, as in the solemn presence of God, “I have done my duty,–I am free from the blood of this man.” Let retailers of spirits, and keepers of public houses be able, also, to make the same declaration.

FURTHER—among the things favourable to morals may be reckoned industry.

PERSONS engaged in some reputable, industrious calling, endeavouring to “provide things honest in the sight of all men,” are found, more usually than the idle, to be friends of morality and order. They have property to be protected. They wish for that security which is attached to union in society where all are engaged in seeking the public good.

A STATE of idleness, on the contrary, exposes to many temptations. It tends to extravagant expense—to poverty—to discontent—to envying others, and coveting their possessions—and, in many instances, to that turbulent conduct which endangers the public welfare.

The view, which has now been taken of the opposite tendencies of morality and vice, is thought sufficient to furnish decisive evidence of the importance of the former, as a means of union in society.

The inference is obvious. A wise republic will guard the morals of her citizens with the most assiduous care. No labour or expense, requisite to guard these, will be deemed too great, no watchfulness too strict; fully convinced, that to neglect or abandon them is to give up the public happiness, and to render insecure every valuable blessing of social life. She will take heed, also, that the same sentiment does feelingly and practically evade every branch of her government.

Apprized of the almost unbounded influence of the examples and sentiments of men in public stations, she will watch over her elections with a jealous eye, and guard against bribery, corruption and intrigue with persevering zeal. Knowing that the progress of degeneracy among a people, once virtuous, is commonly gradual, proceeding from small beginnings at first; she will “look diligently, lest any root of bitterness, springing up,” spread its malignant influence, till “many be defiled” With her, it will be a first principle, sealed with her seal, a principle which no man, on any pretence, may reverse; that all those who are elevated to public and important stations must be men of sound, approved virtue.

It becomes important to ascertain, as was proposed,

(2.) The nature of that virtue which will effectually produce and preserve morals.

It is here desirable to obtain a true description comprising the whole of virtue, in principle as well as practice. To neglect this, in the consideration of the present subject, would occasion a material defect. It is also desirable and necessary to find, if possible, a system of religion, which not only speaks of morals; but effectually influences mankind to practice them. Where then is this to be found? Shall we go to the heathen moralists? They have, indeed, written many valuable truths relating to virtue and morals; but they have failed in essential things: they cannot furnish what is now sought. Shall we repair to the modern infidel philosophy? The world has already tried enough of the bitter fruits of this philosophy to ascertain the nature of the tree. The wretched situation of those nations, who have “experimented” on the principles of this philosophy, forbids us to adopt it. Turn your eyes to these nations. The principles of Voltaire preceded the destruction and misery in which they are now involved. “Hath not God made foolish the wisdom of this world?” Do they experience, in the enjoyment of the blessings of freedom and happiness, “how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity?” Far from it. “Destruction and death can only say, we have heard the same thereof with our ears.” That Being who alone possesses infinite benevolence and unerring wisdom has put into our hands “a sure word,” comprising a complete and perfect system of moral virtue,–including everything that is now sought—and accompanied with “promise of the life that now is, and of that which is to come.”

As it has been much disputed by some whether it is of advantage to civil government to patronize the Christian religion; the subject under consideration authorizes me to state some of the first principles of this religion, that it may be seen how far they comport with the justifiable objects of a civil community.

The existence and perfections of God are at the foundation of all true virtue. Begin, then, with the character of the Deity. This religion reveals to us a Deity rendered glorious and perfect by such attributes as commend themselves to every enlightened conscience. Infinitely just, holy, wise, powerful, merciful and faithful, he is necessarily the unchangeable friend of virtue, and the determinate enemy of vice.

It is, surely desirable to know the original cause of the vices and distresses of the nations. The sacred scriptures point it out. It is the apostacy of our race from God.

In the same scriptures, a law of moral virtue is stated to us, which, in its strictness and purity, resembles God. Holy, just, and good, it leaves not to every man to say what is virtue and what is vice, but both, as will presently appear, are truly and accurately defined.

No vicious propensities are fostered by this law or palliated. The pride of no person whatever, high or low, is flattered with any prospect, that it will or can be abated, in the least, on his behalf. But, a way is revealed in which God can be just and yet justify the penitent and reformed sinner, thro’ faith in Jesus Christ the son of the Highest who, by becoming a sin offering, has magnified the law and made it honourable. Thus, the divine law is supported, and moral virtue secured.

Not only does this religion shew to man the origin and nature of his moral disorder, but, different from all other religions, it makes effectual provisions for his cure, in a radical and total change of heart. In this change, “a new creature” is formed, by the power of the Holy Ghost, and a thorough, permanent principle of moral virtue is given. Men are “created unto good works,”—formed to act with fidelity in every situation of life.

This religion having thus formed men for moral virtue, proceeds to furnish them with instructions relative to duty in every condition of life. The law of God is continually placed before them, for their study and practice. A summary of it is given in these words, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength:–and—Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thy self.” This is true virtue. A transgression of this law is sin,–is vice.

This summary, so far as is necessary, is traced out into its several branches. The disciple of Christ is taught to “deny ungodliness and worldly lusts; and to live soberly, righteously, and godly:” soberly, as it respects personal duty, exercising temperance, modesty and humility;–righteously, in his intercourse with his neighbour, “doing to others as he would that they should do to him;”—and godly in his treatment of the Deity, honoring him in all his institutions, and having a supreme regard to his glory in every transaction of life.

The religion of the Bible commands the public worship of the Deity. It enjoins the observation of the Sabbath, and, on this holy day, it forms a public school of moral virtue. While men stand in the holy presence of their Creator, a sense of his attributes is awakened,–they are reminded that they must be like him,–that they must “love one another, and live in peace.”

Men are taught, by this religion, their duty, in all their relative stations. The ruler finds his duty pointed out,–the subject finds his. The ruler is taught that he is to be a “minister of God,”—sent by him to be a “terror to evil doers and a praise of them who do well.” The subject is taught “to obey magistrates, and to submit to every ordinance of their appointment for the Lord’s sake.” If the citizen be favoured with the privilege of electing his rulers, the characters to be chosen are plainly pointed out to him. They are to be “just men, men of truth, haters of covetousness, fearers of God.” In the important transaction of choosing a ruler, the person cannot disregard the “oath of God” and be guiltless; for, even in the common concerns of life, he is not to abandon religious principle, but “whatever he does, is all to be done to the glory of God.”

Masters and servants—husbands and wives—parents and children—all find appropriate directions, relative to the duties of their respective stations. Every vice is condemned. Every social virtue is enjoined.

The religion communicated in the sacred scriptures having taught men that in this life they form their characters, and fix their destination for eternity, places before them the eternal retributions. Nothing can be so dreadful as the punishments that will assuredly be inflicted upon the vicious,–nothing so glorious as the rewards that will be bestowed upon the virtuous. They both infinitely exceed all that human laws can pretend to. The laws of Christ extend to every motive of action. They take cognizance of crimes which neither the law nor the eye of man can reach. They enjoin many acts of kindness and humanity which are not to be known till “the resurrection of the just.” They follow the workers of iniquity into every place of darkness where they may attempt to screen themselves from human view; assuring them that they are “naked and opened” to the penetrating eye of an almighty avenger, always present, always noticing their conduct for the purpose of a future judgment,–thus “placing by the side” of every crime an adequate and certain punishment.

To the consciences, and not to the passions of my audience is the appeal now made. Cannot this religion be of service to civil government?—In the consequence of every intelligent hearer, the answer is ready,–and it is the same.

Let it be added, that the period is advancing when there shall be the fullest display of the salutary influence of this holy religion upon civil government. “The kingdoms of this world shall become the kingdoms of the Lord and of his Christ: for the mouth of the Lord of hosts hath spoken it.”

Previous to this period, there are to be dreadful desolations in the earth; men having, by their great wickedness, become ripe for the execution of divine vengeance. These desolations are signified to us in scripture by the representation of “an angel standing in the sun, crying with a loud voice, and saying to all the fowls that fly in the midst of heaven, Come and gather yourselves together unto the supper of the great God; that ye may eat the flesh of kings, and the flesh of captains, and the flesh of mighty men, and the flesh of horses, and of them that sit on them, and the flesh of all men both free and bond, both small and great.”

If the time referred to in this representation be now commenced, the next important event will be the binding of Satan, and the ushering in of the millennial day.

“Behold, I come as a thief,” saith the glorious judge. A careless, unbelieving world will not know his judgments, nor consider the operation of his hand, in the passing events.

Blessed are those servants, of all descriptions, who watch, and are found, of their Lord, faithfully performing the duties of their respective stations.

Civil Rulers, exalted in the providence of God to decree and administer justice, will feel themselves addressed by the subject. While they bestow due praise upon those who do well, they will be a terror to evil works.

Duly impressed, also, with a sense of their obligations to the most High, they will adorn their honourable stations by “adorning the doctrine of God their Saviour.”

The Lord commanded the ruler of his people to pay great attention to the divine law. “It shall be with him,” saith the command, “and he shall read therein all the days of his life; that he may learn to fear the Lord his God; that his heart be not lifted up above his brethren; and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand or to the left.”

The same general reasons for cultivating an intimate acquaintance with the word of God must ever exist. The commandment of the Lord is pure, enlightening the eyes.”

“God is not a respecter of persons,” but of moral character. May the honoured and respected rulers of this state, ever be influenced by the most High, to honour him, and become blessings to his people, by maintaining a religious, firm, upright deportment. “Them that honour me I will honour,” saith the Lord.

Ministers of the gospel are reminded, by the subject under consideration, of the duties, which they, in their proper spheres, are required to perform to God, to their country, and to the souls of men.

When we engaged in the sacred office, my brethren, though we did not give up our rights as citizens, yet the chief employment assigned to us was to promote virtue, and bear testimony against sin. We are to beseech men, in Christ’s stead, to be reconciled to God. We are also to bear testimony against sin. When the voice of every friend of God, and of mankind ought to be lifted up against the vices that destroy the peace of society and the souls of men, let us not keep undue silence.

It is our acknowledged duty also, continually to intercede with the Most High for our common country, and for the churches of the Saviour, that he would “spare his people and not give his heritage to reproach.”

If we may be the happy instruments of promoting that love to God and man, and that pure morality which the gospel of our Lord and Saviour enjoins, we shall do an essential service, not only to the souls of men, but also to our country.

The chief design of the gospel is to fit men for the eternal enjoyment of God in heaven. And, in doing this, it necessarily enforces those principles and that conduct in the present life, which cannot fail to produce the most benign effect on civil society. The great duty of love or charity which the gospel enjoins is the strongest bond of union in society of any that can be named. Short is the period of duty in the present world. The recent and numerous deaths 2 of our brethren in the ministry remind us that “the time is short.” Let us “give all diligence in making full proof of our ministry. There is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom in the grave.”

The Freemen of the State have also a real and important interest in considering and understanding the subject suggested by the text. God has entrusted with you, fellow-citizens, the protection of your rights and privileges. Be thankful to him for the favour. Let no flattery entice, nor the gratification of any sordid passion allure you to part with the sacred deposite. Rising superior to every partial and degrading motive, and looking steadily at the common good, labour to strengthen the bonds of that “unity,” which causes it to be “good and pleasant for brethren to dwell together.” Virtuous principle is the basis of your government and must be the pledge of your security.