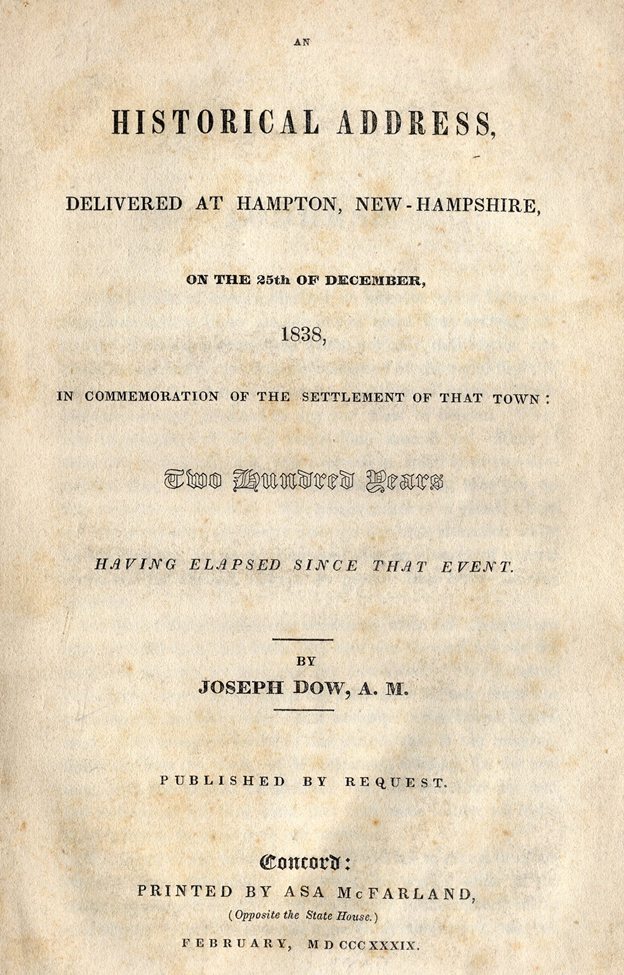

Joseph Dow preached this sermon in Hampton, NH on Christmas Day, 1838.

ANHISTORICAL ADDRESS,

DELIVERED AT HAMPTON, NEW-HAMPSHIRE,

ON THE 25TH OF DECEMBER

1838,

IN COMMEMORATION OF THE SETTLEMENT OF THAT TOWN:

TWO HUNDRED YEARS

HAVING ELAPSED SINCE THAT EVENT.

BY

JOSEPH DOW, A. M.

ADDRESS.As in the life of every individual, so likewise in the history of every community, there are seasons of more than ordinary interest. There are occasions, where not only individuals, but whole communities, are forcibly reminded of the rapid flight of time, and of the changes effected in a series of years. These changes are not confined to any one class of objects. They may be predicted of almost every thing around us. Many of them are so gradual, that, when viewed in relation to two successive days, they are wholly imperceptible; but they are, on this account, no less real. The countenance of a friend, whom we see every day, appears to undergo but little alteration while he is in health; but let us meet him after an absence of several years,, and the change, though no greater than before, is very apparent.

On one of those interesting occasions, when our thoughts are busy with the past, and when they also run forward to scan the events of futurity, we have this day assembled. Two hundred years have passed away since the settlement of our town was commenced, and the church that worships in this house, organized. Our thoughts revert to that period, and, in our imaginations, we hear the forests of Winnicumet, echoing, for the first time, with the sounds of civilized life. In the character and the fortunes of the little band that then came hither, we feel a deep interest, for they were our ancestors.

My object in the following remarks, will be, to give a brief account of the settlement of the town; to notice some of the more important transactions of the people, in the infancy of the settlement; to exhibit, however imperfectly, their trials, dangers, and sufferings; and then to trace, in a cursory manner, the history of the first church, through a period of two centuries.

The first permanent settlement in New-England was made near the close of the year 1620.

On the 10th day of August, 1622, a grant was made, by the Council of Plymouth, to Sir Ferdinando Gorges, and Captain John Mason, jointly, of all the land lying between the rivers Merrimack on Sagadehock, now the Androscoggin,–extending back to the great lakes and the river of Canada. This tract was called Laconia, and it was the first grant in which the territory of Hampton was included.

The next year a settlement was commenced near the mouth of the Piscataqua, and another further up the river, at the place which subsequently received the name of Dover.

The principle object in the formation of these settlements, both of which were commenced under the patronage of Gorges, Mason, and several English merchants, styled the “Company of Laconia,” was to carry on the fishing business, which, it was thought, would prove very lucrative.

May 17, 1629, a Deed is said to have been given by certain Indian chiefs, assembled at Swamscot falls, now Exeter, to Rev. John Whelewright and others, conveying to them, for what was deemed an equivalent, all the land along the coast, between the Merrimack and the Piscataqua rivers, and extending back to a considerable distance into the country. In this tract our own territory was evidently embraced.

Recently, however, the authenticity of this Deed has been denied, though it is admitted that Whelewright, several years afterwards, purchased of the Indians all the land lying within a considerable distance of Swamscot falls. A similar course was probably pursued by those who formed the first settlement in this place.

On the 7thday of November, 1629, the Council of Plymouth made a new grant to Captain Mason, of a tract of land “from the middle of Piscataqua river, and up the same to the farthest head thereof, and from thence north-westward, until sixty miles from the mouth of the harbor were finished; also through Merrimack river, to the farthest head thereof, and so forward up into the land westward, until sixty miles were finished; and from thence to cross over land to the end of the sixty miles as counted from Piscataqua river; together with all islands within five leagues of the coast.” This tract was called New-Hampshire, and it included the whole of Whelewright’s purchase, if such a purchase was ever made, and a part of the land previously granted to Massachusetts, as by the charter of that colony its territory extended three miles north of the Merrimack.

By other arrangements, made in 1630 and 1631, the settlements on the Piscataqua were divided into two parts, called the upper and the lower plantations. Captain Thomas Wiggen was appointed agent for the former, and Captain Walter Neal for the latter, which extended as far south as the stream called Little river, in the eastern part of North-Hampton.

In 1633 these two agents united in surveying their respective patents, and in laying out the towns of Portsmouth, Northam, afterwards called Dover—and Hampton; though no settlement had at that time been made at the place last mentioned.

Dr. Belknap sys, that this survey was made by order of the company of Laconia, and that these towns, together with Exeter, were named by that company. Hampton was, however, incorporated by is present name at the request of the first pastor of the church established here. Whether he chose the name in conformity to the wishes of the company of Laconia, I cannot tell.

I have been thus particular in noticing the different grants that were made of the same territory, as they gave rise to much subsequent litigation and expense, by which this town, as well as others, was exceedingly harassed.

In 1636 the General Court of Massachusetts authorized two persons, Mr. Dummer and Mr. Spencer, to erect a house at Hampton, which was then called by its Indian name, Winnicumet. A house was accordingly built by Nicholas Easton, under the direction of the two persons just mentioned, and at the expense of the Colony of Massachusetts. This house was called the Bound House, although, as Dr. Belknap observes, it was intended as a mark of possession rather than of limit.

There is no evidence that a settlement was actually made here, till two years afterwards. For what purpose, then, was the Bound House erected?

The General Court had learned, that there were in this vicinity extensive salt-marshes. These must, at that time, have been very valuable, as the upland had not been brought to such a state of cultivation as to afford a sufficient quantity of hay to winter the stock which might be kept through the summer. The court wished to secure these marshes, and, by causing a house to be erected near them, at the expense of the Colony, they virtually claimed jurisdiction over them. It was, perhaps, for the purpose of asserting such a jurisdiction, that they adopted this measure.

On what grounds could the General Court claim jurisdiction here? The chartered limits of Massachusetts extended only three miles north of the Merrimack; but the Bound House was probably much farther from that river.

That they did set up such a claim, is evident from the fact that they soon after made a formal grant of the territory to the company that actually formed a settlement here.

By a plain, natural construction of the meaning of their character, this place was, undoubtedly, beyond their limits, while it was evidently included in the grant made to Captain Mason. The charters, however, that were given by the Council of Plymouth, and also those granted by the Crown, were often worded with too little care. Sometimes, unquestionably, this arose from a want of sufficient geographical information concerning the portions of country granted, and, at other times, from sheer carelessness.

In this case, the grant to Massachusetts was of land reaching to “three miles north of the Merrimack river, and of every part of it.” Now, though that river is more than three miles south of this place, yet, if we trace it up to its source, we shall find, that it rises much farther to the north than we are, and Massachusetts claimed the land to our east and west line, passing through a point three miles north of the most northerly part of the river.

Such a construction of their charter would give the people of that Colony all the land granted to Mason, and a large part of Maine, which had been granted to Gorges; thus rendering the claims of these two gentlemen null and void, as the grants to them were made after that to Massachusetts.

The agent of Mason’s estate made some objections to the claims and the proceedings of Massachusetts, yet no legal method was taken to controvert this extension of their claim; and, as the historian of New-Hampshire very justly observes, “the way was prepared for one still greater, which many circumstances concurred to establish.”

In 1638 a petition was presented to the General Court of Massachusetts, by a number of people, chiefly from Norfolk in England, praying for permission to settle at Winnicumet. On the 7th of October their request was granted. Few privileges, however, were allowed besides that of forming a settlement. In the language of the early records of our town, “the power of managing the affairs thereof was not then yielded to them, but committed by the court to” three gentlemen, not belonging to the settlement, “so as nothing might be done without the allowance of them, or two of them.” 1

It was not till the 7th of June, 1639, that the plantation was allowed to be a town, and to choose a constable and other officers, and, as our records state, “to make orders for the well ordering of the town, and to send a deputy to the court.” Even then the power of laying out land was not granted to the town, but was left to the three gentlemen to whom I have already alluded.

At that time three men belonging to the town, viz. Christopher Hussey, William Palmer, and Richard Swaine, were appointed by the General Court, as commissioners, or justices, to have jurisdiction over all causes of twenty shillings, or under.

On the 4th day of September, in the same year, at the request of Rev. Stephen Bachelor, the name of the town was changed from Winnicumet to Hampton, and about the same time, through the influence of their deputy, the right of disposing of the land, and laying it out, was vested in the town.

The number of the original settlers was fifty-six. Rev. Dr. Appleton, in his dedication sermon, preached in 1797, says, “of the names of the first settlers of Hampton, only sixteen are transmitted to us; and but four of these names continue in the place.” 2 The same four names are still found among us, though one of them will probably soon become extinct, as it is now borne by only two individuals, both of them aged females.

The names of the sixteen persons referred to by Dr. Appleton are given in the first volume of Belknp’s History of New-Hampshire. In that list the name of only one female is found, and it is probable that most of the other settlers were members of the families of these sixteen.

Though the number of settlers was at first only fifty-six, yet large additions were soon made. At the time when the settlement became a town, the number of inhabitants had very much increased. Indeed, a writer who lived and wrote about that time, says that in 1639 there were about sixty families here. 3 It has been supposed that this writer stated the number larger than it really was. There are, however, reasons for believing that his statement is not far from the truth. In the record of the proceedings at a town meeting, early in the following year, more than sixty individuals are mentioned; and it is probable, from the great diversity of their names, that they belonged to nearly as many different families.

The historian of New-Hampshire says, that the people here began the settlement by laying out the township into one hundred and forty-seven shares. Others, relying upon him as authority, have repeated the statement. Our records, however, furnish an abundance of evidence that it is incorrect; and had Dr. Belknap, in this instance, exercised his usual caution, he would not have been led into such an error. The transaction which probably gave rise to this remark, did not occur till more than seven years after the settlement was commenced, and, even at that time, there was a division of only a small portion of the land within the limits of the township.

The course the people really pursued was far different from that which has so often been imputed to them. Soon after they were allowed the privileges of freemen, they began to exercise them. The first town meeting, of which any record remains, was held October 31, 1639. William Wakefield was chosen town clerk. The freemen, instead of proceeding to lay out the township into any definite number of shares, appointed a committee, whose duty it should be, for the space of one year, “to measure, lay forth, and bound all such lots as should be granted by the freemen there.” The compensation allowed this committee, was twelve shillings for laying out a house lot, and in ordinary cases, one penny an acre for all other land they might survey.

Only one other article was acted upon at this meeting. The object of that was to secure the seasonable attendance of the freemen at town meetings. A vote was passed, imposing a fine of one shilling on each freeman, who, having had due notice of the meeting, should not be at the place designated, within half an hour of the time appointed.

On other occasions, similar votes were passed, and rules were adopted to secure order and regularity, when the people were assembled in town meeting. I will mention the substance of several regulations made in 1641.

At the close of each meeting, a moderator was to be chosen, to preside at the next meeting.

Every meeting was to be opened and closed with prayer by the moderator, unless one of the ministers were present, upon whom he might call to lead in that exercise.

After the prayer at the opening of the meeting, the names of the freemen were to be called, and the absentees noted, by the town clerk.

The moderator was then “to make way for propositions” to be considered at the meeting. In doing this, he might propose any business himself, or he might call upon others to mention subjects to be acted upon.

When any person wished to speak in the meeting, he was to do it standing, and having his head uncovered.

When an individual was speaking in an orderly manner, no other one was to be allowed to speak without permission; and no person was to be permitted to speak, at any meeting, more than twice, or three times at most, on the same subject.

When any article of business had been proposed, it was to be disposed of before any other business could be introduced.

Penalties were to be exacted for every violation of any of these rules.

December 24, 1639, grants of land, to the amount of 2,160 acres, were made to 13 persons, in parcels, varying from eighty acres to three hundred. These were merely grants of a certain number of acres, without determining where the different lots should be located. The locations were fixed at subsequent meetings.

It is worthy of notice, that the persons who were regarded as the principal men in the town, received grants of the largest tracts of land, and so uniformly was this the case in regard to those individuals whose rank is known, that we may probably judge, with a considerable degree of accuracy, concerning the standing of others, by the grants made to them. In making the grants just mentioned, the records inform us, that “respect was had, partly to estates, partly to charges, and partly to other things.”

Town meetings were frequently holden, at which, in addition to the election of the necessary town officers, the making of regulations for the government of the people, the laying out of highways, and the transaction of such business as ordinarily comes before town meetings, at the present day, the people by vote, admitted persons to enjoy the privileges of freemen, and, from time to time, made such grants of land as they thought proper.

We come now to the transaction, alleged to have been a division of the town into 147 shares. It took place on the 23d of the 12th month, 1645; that is, according to the method of reckoning time, afterwards adopted, in February, 1646. At that time the town having previously disposed of a large portion of the land that had been surveyed, agreed to reserve 200 acres to be disposed of afterwards, and to divide the remaining part of the commons into 147 shares, and to distribute it among persons, most or all of whom had received previous grants.

There is some uncertainty as to the extent that was intended to be given to this order. It is certain that it was not designed to include all the land within the township, which had not already been disposed of, as large tracts were afterwards ordered to be laid out, and others were granted to individuals at different times. The probability is, that it was intended to embrace only such parts of the town as had been actually surveyed, but had not been granted to individuals. 4

Six years after this transaction, it was determined at a public town meeting, that the great Ox-Common, lying near the Great Boar’s Head, “should be shared to each man according as it would hold out.” It appears from the records, that in conformity to this order the common was divided into about seventy-five shares, and distributed among a portion of the people; most of those to whom any part was granted, received one share each, though a few individuals received two, or even three shares apiece.

Four years afterward, Sargent’s Island was appropriated to the use of fishermen, for the purpose of building stages and other things necessary in curing fish. There was in the grant, however, a promise, that, if the island should be deserted by fishermen, it should still remain at the town’s disposal. On the 9th of June, 1663, it was voted in town meeting, that the land in the west part of the town should be laid out to the amount of four thousand acres, extending through the whole breadth of the town along its western boundary. Subsequently it was determined that this land should be laid out, partly in hares of 80 acres each, and partly in shares of 100 acres each.

About a year afterwards, it was agreed, that each one of the inhabitants of the town, who would assure the selectmen that he should settle on these lands within twelve months, should be entitled to twenty acres for a house lot.

This land was called the New Plantation, and it extended from Salisbury to Exeter, and of course was a part of land now embraced in three or four towns.

I have mentioned these instances of grants and of laying out land, merely as a specimen of the course which our forefathers pursued. 5

When the settlement was in its infancy, it would have been very much exposed to injury if no precautions had been taken in regard to receiving inhabitants. Mischievous and disorderly persons might have come in and harassed the settlers. This was foreseen, and measures were taken to prevent it. The power of admitting inhabitants and of granting them the privileges of freemen, was strictly guarded. After the town was once organized, none were admitted from abroad without the permission of the freemen. It was voted, “that no manner of person should come into the town as an inhabitant, without the consent of the town, under the penalty of twenty shillings per week, unless he give satisfactory security to the town.”

On different occasions, votes were passed to prohibit the selectmen from admitting inhabitants. I will cite several of these, nearly in the words of the Town Records, as they will serve to show the course that was taken in regard to the subject.

The first vote of this kind, on record, is dated on the 6th of the 10th month, 1639, and is as follows:–

“Liberty is given to William Fuller of Ipswich, upon request, to come and sit down here as a planter and smith, in case he bring a certificate of approbation from the elders.”

“On the 25th of the 9th month, 1654.—By an act of the town, Thomas Downes, shoemaker, is admitted an inhabitant, who is to make and mend shoes for the town, upon fair and reasonable terms.”

“May 22, 1663. Thomas Parker, shoemaker, desiring liberty to come into the town and follow his trade of shoemaking, liberty accordingly is granted him by the town.” Ten men, however, dissented from this vote.

On the 8th of the 10th month, 1662, an order of the town was passed determining who should be regarded as inhabitants. It runs thus:–“It is acted and ordered, that henceforth no man shall be judged an inhabitant in this town, nor have power or liberty to act in town affairs, or have privilege of common-age, at least, according to the first division, and land to build upon.”

The sources of some of the troubles and perplexities of the early settlers, will next claim our attention. They were harassed by wild beasts, and by lawless men. No wonder, indeed, that they were troubled by the former. Until the English settlements were formed, the wild beasts had been free to range the country, their right undisputed, and themselves unmolested, except occasionally by the Indian hunter. It could hardly be expected that they would tamely yield to the new settlers, and acknowledge their right of jurisdiction over them. Though they did not often attack the people, yet they showed less respect for their herds and flocks. It then early became an object with the people to destroy such beasts as were found to be troublesome. Perhaps none annoyed them more than the wolves; and bounties were offered by the town, as an inducement for killing them.

In January, 1645, a bounty of ten shillings was offered for each wolf that might be killed in the town. 6 Nine years afterwards the bounty was increased to forty shillings. In 1658 it was raised to five pounds.

In 1663 a bounty of twenty shillings was likewise offered for each bear killed within the limits of the town.

The settlers were also troubled by disorderly persons. Depredations were often made upon the common lands owned by the town. The making of staves appears to have been a profitable employment, and some persons, who were engaged in this business, were not very scrupulous in regard to the means employed to procure timber. Wherever they could find any, that was suitable for staves, they took it, without inquiring to whom it belonged. The very best of the timber was thus, in many instances, taken from the commons. The town adopted various expedients to prevent such acts, but still depredations continued to be committed.

In some instances, persons, whom the town had never admitted as inhabitants, settled on the public lands. In other cases, difficulties occurred, and disputes arose, in consequence of the boundaries of the town not being well defined. There were disputes of this kind with Salisbury, and with Portsmouth.

The township extended so far north as to include a portion of the present town of Rye, and near the northern limit several persons settled without permission from the town. One of the most resolute and stubborn of them was John Locke, who settled at Jocelyn’s,–now Locke’s,–Neck. He was ordered to leave the town, but seems not to have regarded the order; and at length, a committee was chosen at a public town meeting, to go and pull up Locke’s fence, and give him notice not to meddle further with the town’s property. The difficulty with him was not settled till he, having expressed a willingness to demean himself peaceably as a citizen, was received as an inhabitant, by a vote of the town.

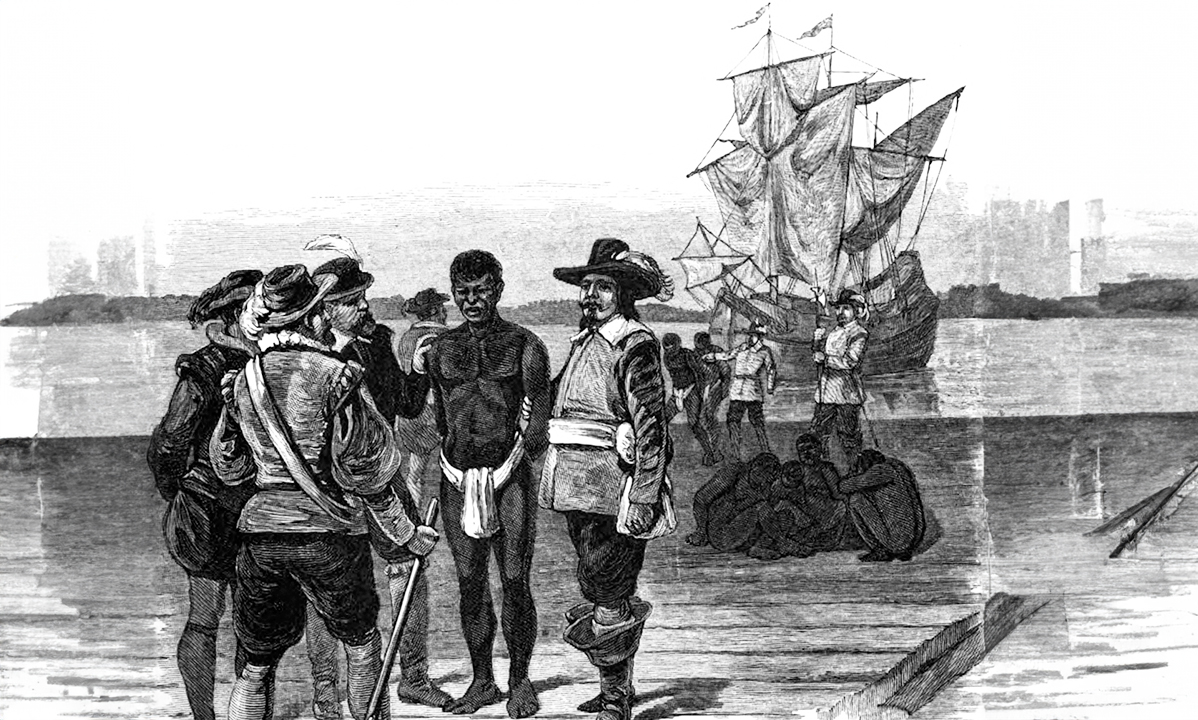

In speaking of the trials of our forefathers, it would be inexcusable to pass over in silence the dangers and the sufferings which resulted from the hostility of the Indians. It is uncertain how soon after the first settlement of the town they began to manifest their hostility. It is, however, evident that it was at a very early period.

In the latter part of the year 1640, the town passed a vote in relation to a watch-house, appropriating the meeting-house porch to this purpose, temporarily, till another could be procured. The object of providing a watch-house is not, indeed, stated, but we can hardly conceive of any object, unless fears were entertained from Indian hostility. That such was really the case will appear probable, if we compare this vote of the town with another passed several years afterward, at a time when it is well known that most of the settlements in this vicinity were exceedingly harassed by the Indians. The selectmen were then ordered “to build a convenient watch-house, and to provide powder, balls, watches, flints, and what else the law requires, for a town stock for the soldiers.”

Trainings were also ordered at an early period. Our records mention one that was appointed by the officers to be held on the 18th of May, 1641. Whether military duty was required by the town, or enjoined by the government of Massachusetts, is not of consequence. In either case, it shows that danger was apprehended from some source or other; but whence, except from the Indians, could the early settlers in this section of our country anticipate danger, which might be repelled by force of arms?

On the 8th of July, 1689, a vote was passed, very explicit, in regard to the town’s apprehension of danger from the Indians. The vote is as follows:–“That all those who are willing to make a fortification about the meeting-house, to secure themselves and their families from the violence of the heathen, shall have free liberty to do it.”

A fortification was accordingly built around the meeting-house, distinct traces of which remained till the academy was removed, a few years ago, to the spot it now occupies, and the land around it ploughed. I believe that, even now, a small portion of the mound may be seen, just without the east side of the academy yard.

May 17, 1692, it was voted to extend the line of this fortification, so as to enclose more space, and liberty was given “to build houses in it according to custom in other forts.”

At the same time it was voted to build within the fort, at the town’s expense, a house 14 by 16 feet, for the use of the minister, and that, when he made no use of it, it should be improved as a school-house.

About a year previous to the transaction just named, “it was voted that a committee should be chosen to agree with, and to send out two men as scouts, to see what they could discover of the enemy, so long as they could go upon the snow, or so long as the neighboring towns sent out.”

A distinguished historian says of a period a little subsequent to this, that “the state of the country at this time was truly distressed: a large quota of their best men were abroad, the rest harassed by the enemy at home, obliged to do continual duty in garrisons, and in scouts, and subject to severe discipline for neglects. They earned their bread at the continual hazard of their lies, never daring to stir abroad unarmed; they could till no lands but what were within call of the garrisoned houses, into which their families were crowded; their husbandry, lumber trade and fishery, were declining, and their taxes increasing, yet these people resolutely kept their ground.” 7

But we need not confine our attention to a recital of their fears and apprehensions, and to their preparations for self-defence. We may look at the actual loss of lives among them. How many of the early inhabitants of Hampton were slain by the Indians, we cannot confidently tell. The following facts rest on good authority.

On the 13th of June, 1677, four persons were killed in that part of the town which is now North-Hampton. These men were Edward Colcord, Jr., Abraham Perkins, Jr., Benjamin Hilliard, and Caleb Towle.

August 4, 1691, Capt. Samuel Sherburne and James Dolloff, both of Hampton, were killed by the Indians, near Casco Bay, in Maine.

August 26, 1696, John Locke was killed, while at work in his field, in the northeast part of the town, at Locke’s neck, now in the town of Rye. 8

August 17, 1703, five persons were killed between this town and Salisbury. One of them was a little boy, named Huckley. The others were Jonathan Green, Nicholas Bond, Thomas Lancaster and the widow Mussey. The last two were quakers. One of them, Mrs. Mussey, was distinguished as a speaker among the quakers, by whom her death was much lamented.

Dr. Belknap states that these persons were killed at Hampton village y a party of Indians under Capt. Tom, and further, that at the same time, the Indians plundered two houses, but having alarmed the people, and being pursued by them, they fled.

August 1, 1706, Benjamin Fifield was killed in the pasture near his house, and at the same time a boy was either killed or taken.

Having mentioned these instances of murder, nearly all of which were committed within the limits of Hampton, I will merely subjoin a brief account of an expedition, which proved fatal to Capt. Swett, one of the inhabitants of this town. He was sent by the government to assist the eastern settlements against the Indians. He was accompanied by forty English soldiers, and 200 friendly Indians. With these forces he marched to Ticonic falls, on the Kennebeck, where it is said the Indians had six forts, well furnished with ammunition. Having met the enemy, Swett and his men were repulsed, and he himself with about sixty others slain. Probably a part of this number, as well as their leader, belonged to this town.

We shall next glance at the civil and political history of the town during the early period of its existence. In doing this, it may be proper, not only to consider the connection of the town with the colonial governments of Massachusetts and of New-Hampshire, but also the policy pursued by the people, considered simply as a town.

Very soon after the inhabitants acquired corporate powers, we find them, as has already been remarked, assembled in town meeting. The transactions at the first meeting of which any record remains, have already been noticed. A town clerk, and three lot layers were chosen, the latter for the term of one year. It appears from the records that some of the town officers were from the first elected annually. Others seem to have been chosen for an indefinite period, or till their places should be supplied by a new election. The first town clerk held his office more than four years, probably without being annually reelected. His successor continued in office nearly three years before any new election was made. There is no evidence from the records that this became an annual office for more than sixty years after the settlement was commenced.

It may be well here to notice the fact, that the people of this place have not, during any period of their history, been disposed to change their town clerks frequently, there having been less than twenty during the two hundred years that the town has existed.

The duties and the compensation of the lot-layers have been already mentioned.

Another set of officers, chosen at a very early period, was that of woodwards, an office which long ago became extinct among this people. It would be very natural to suppose that when almost the whole township was a wilderness, no objection would have been made to cutting trees in any part of it; but such was not the case.

As early as 1639, three woodwards were elected, and no man was to fell any trees except on his own lot, without permission from these men, or at least two of them; and at another meeting during the same year, the town voted a similar prohibition, and also a fine for its violation. The fine was ten shillings for every tree felled without license from the woodwards.

It was further voted, that if any man had any trees assigned to him, he should fell them within one month, and make use of them within three months after felling, or the trees should be at the disposal of any two of the woodwards.

In taking a brief notice of the town officers, during the early part of our history, it will probably be expected that the board of selectmen should hold a prominent place. It does not appear, however, that such officers were elected till the settlement had been begun several years. The practice of choosing selectmen seems to have been of New-England origin, and to have grown up from the circumstances in which the early inhabitants were placed. After they had established themselves in the wilderness, far from their native land, and from the seat of that government to which they acknowledged allegiance, they found themselves under the necessity of managing their own affairs. At first these seem to have been conducted in a purely democratic way, so far at least as those who were regarded as freemen were concerned. They held frequent town meetings, and delegated power to committees from time to time, only for a specific purpose. This method of proceeding being at length found inconvenient, several persons were chosen to act for the town, as it is expressed in the records, “in managing the prudential affairs thereof.” This board of officers, to which at length the name of selectmen was given, at first, consisted in Hampton, of seven persons. The first notice of such a board is in 1644. On the 4th of May in that year, the following vote was passed—“These several brethren, namely—William Fuller, Thomas Moulton, Robert Page, Philemon Dalton, Thomas Ward, Walter Ropper, and William Howard, are chosen to order the prudential affairs of the town for a whole year, next following; reserving only to the freemen the giving out of commons and receiving of inhabitants.”

In about ten or twelve instances the number of selectmen has been seven. Generally five were chosen, till the year 1823, and from that time to the present only three have been elected annually, except in the year 1829, when the board consisted of five persons.

It is unnecessary to speak particularly of other town officers, as they were generally the same, and possessed of similar powers, with those of more modern times.

To show that the town took cognizance of some matters which at the present day are left to adjust themselves, I will mention a regulation, made in 1641, in regard to wages. From September to March, workmen were to be allowed only 1s. 4d. per day, and from March to September, 1s 8d. except for mowing, for which 2’s should be allowed. For a day’s work for a man with four oxen and a cart, five or six shillings were to be allowed, according to the season of the year. Soon after it was voted that the best workmen should not receive more than 2s. a day, and others not more than 1s. 8d.

It has already been noticed, that Hampton was settled by the authority of Massachusetts, and it was for many years considered under the jurisdiction of that colony. In 1639 the town was authorized to send a deputy, or representative, to the General Court at Boston.

This privilege was not long neglected, for about five months afterwards the town assessed a tax to pay their deputy, John Moulton, who had at that time been twice to the court, having spent twenty-seven days in the service of the town. The compensation allowed him was 2s. 6d. per day, besides his expenses.

In September, 1640, John Cross was elected a deputy to the court to be holden on the 7th day of the next month. He was the second representative chosen by the town.

Hampton was probably for a short time under the immediate jurisdiction of the courts at Boston. On the 25th of July, 1640, a “grand juryman” was chosen for the court to be holden at Boston in the following month.

The town was soon annexed to the jurisdiction of the county of Essex, whose courts were held at Ipswich.

In 1643 a new country was formed, embracing all the towns between the Merrimack and Piscataqua rivers. This was called the county of Norfolk. The number of towns within its limits however, had courts of their own, and in each of the towns there was an inferior court, whose jurisdiction extended to causes of twenty, had courts of their own, and in each of the towns there was an inferior court, whose jurisdiction extended to causes of twenty shillings and under.

The claim of Massachusetts to jurisdiction over the whole territory embraced within the county of Norfolk, was not undisputed. Mason, to whom a large part of it had been granted by charter, was dead. His heirs made some opposition, but there were at that time almost insurmountable difficulties in the way of obtaining redress by a civil process. In England, Charles and his Parliament were at variance, and civil war was raging among the people. When, after the execution of the king, Cromwell was at the head of the Commonwealth, Mason’s heirs could not hope for success in bringing an action against Massachusetts, for his family had always been adherents to the royal cause.

At the restoration in 1660, an attempt was made to influence the king to grant relief to the heir, or rather to the heir, of Mason. A petition for this purpose was presented to Charles II., who referred it to his Attorney General, and he reported that the petitioner had a good and legal title to the Province of New-Hampshire.

In 1664 commissioners were appointed by the crown to settle disputes in the New-England Colonies. These commissioners were not very favorably received, as their appointment, with such powers as were conferred upon them, was considered by the colonists an infringement of their chartered rights.

On their arrival in New-England, they made inquiries in regard to the bounds of Mason’s patent, and decided that the jurisdiction of Massachusetts should extend no farther north than the Bound House.

The proceedings of the commissioners gave umbrage to a large portion of the people. A party, however, had been previously disaffected towards the government of Massachusetts. A person by the name of Corbett, who belonged to this party, instigated, probably, by the commissioners, prepared a petition to the king in the name of the towns of Portsmouth, Dover, Exeter, and Hampton, complaining of the usurpation of Massachusetts, and praying for a release from that government. A large majority of the people, however, did not countenance these proceedings, and at their request the General Court of Massachusetts appointed a committee, before whom the people of the four towns had an opportunity to show their disapprobation of Corbett’s proceedings. Corbett himself was apprehended by warrant from the secretary of Massachusetts, in the name of the General Court, and tried and found guilty of sedition, and punished with severity.

Soon after this period the New-England colonies were involved in a general war with the Indians. Previous to that time, the wars with them had been of limited extent. For many years their minds had been full of suspicions and of jealousies. These were fanned and blown into a flame by Philip, a powerful sachem, who resided at Mount Hope, in Rhode Island. He was resolved upon a war of extermination. He sent runners to most of the tribes in New-England, and succeeded in engaging nearly all of them in an enterprise so adroitly planned.

Open hostilities commenced in June, 1675. The eastern Indians, who resided in Maine, extended their incursions into New-Hampshire. Houses were burned, and people slain, in various places. One man was killed and another captured, by a small party that lay in ambush near the road, between this town and Exeter. The one who was taken afterwards made his escape.

I shall not proceed to narrate in detail the events of this war. The dangers and the sufferings of the people of Hampton, at that time, have been already noticed. It must suffice to add, that the war terminated in the southern part of New-England, with the death of Philip, in August, 1676. In New-Hampshire, it raged two years longer, and for a time seemed to threaten the extinction of the whole colony.

During this war, the heir of Mason made another attempt in England to recover possession of New-Hampshire. Massachusetts was called upon by the crown to show cause why she exercised jurisdiction over this province. The royal order was brought to Boston by Edward Randolph, a kinsman of Mason. He soon came to New-Hampshire, and published a letter from Mason, in which he claimed the soil of the province as his own property. The people here were alarmed, and called public meetings, in which they protested against the claim, and agreed to petition the king for protection.

They stated that they had purchased the land of the natives; that they had labored hard to bring it under cultivation, and they thought it very unjust that their hard earned property should now be wrested from them.

Agents were sent over to England, after Randolph’s return, and a hearing was granted them before the highest judicial authorities. After the hearing, the judges reported that Mason’s heir had no right of government in New-Hampshire; and further, that the four towns of Portsmouth, Dover, Exeter, and Hampton, were beyond the limits of Massachusetts. In regard to Mason’s right to the soil of New-Hampshire, they expressed no opinion.

This report was accepted and confirmed by the king in council.

New-Hampshire was then separated from Massachusetts, with which it had been for so long time so happily united. The commission for the government of New-Hampshire passed the great seal on the 18th of September, 1679.

Under the new order of things, a President and six Counsellors were appointed by the crown, and these were authorized to choose three other persons, to be added to their number. An Assembly was also to be called. The powers of the respective branches of the government were tolerably well defined.

Among the counselors named in the commission, was Christopher Hussey, of this town, and one of the three afterwards chosen also belonged to Hampton, viz—Samuel Dalton.

This change of government was very far from being satisfactory to the people generally, and even those appointed to office entered upon their duties with great reluctance.

In the writs issued for calling a General Assembly, the persons in each town, who were considered as qualified to vote, were expressly named. The whole number in the four towns was 209, fifty-seven of whom belonged to Hampton. The oath of allegiance was administered to each voter. A public fast was observed, to ask the divine blessing on the assembly that was soon to convene, and to pray for “the continuance of their precious and pleasant things.”

The assembly consisted of eleven members, three from each of the four towns, except Exeter, which sent only two, that town having but twenty voters. The members from Hampton were Anthony Stanyan, Thomas Marston, and Edward Gove. The assembly met at Portsmouth, on the 16th of March, 1680. Rev. Joshua Moody, of that town, preached the election sermon.

Under the new government, the President and Council, with the Assembly, were a Supreme court of Judicature, a jury being allowed when desired by the parties. Inferior Courts were established at Dover, Portsmouth, and Hampton.

In 1682, another change was introduced into the government. Edward Cranfield was appointed Lieutenant Governor and Commander-in-chief of New-Hampshire. This change was effected through the influence of Mason’s grandson and heir. Cranfield’s commission was dated May 9, 1682.

Within a few days after publishing his commission, he began to exhibit his arbitrary disposition, by suspending two of the counselors. The next year he dismissed the Assembly, because they would not comply with all his requests.

This act of Cranfield’s very much increased the discontent of the people. In this town particularly, and in Exeter, it created a great excitement. Edward Gove, of this town, a member of the Assembly that had been dismissed, was urgent for a revolution. He went from town to town, crying out for “liberty and reform,” and endeavoring to induce the leading men in the Province to join him in a confederacy to overturn the government. But they were less rash than he was. However they might feel towards the government, they disapproved of Gove’s measures, and informed against him; upon which he collected his followers and appeared in arms; but was at length induced to surrender. He was soon after tried for high treason, was convicted, and received sentence of death. His property was confiscated. He was sent to England, and after remaining imprisoned in the Tower three years, was pardoned, and returned home, and his estate was restored to him.

Several other persons were also tried for treason, two of whom belonged to Hampton. These were convicted of being accomplices with Gove, but were reprieved, and at length pardoned without being sent to England.

Not long after, when the courts had all been organized in a way highly favorable to Mason, he commenced suits against several persons for holding lands and felling timber which he claimed. These suits were decided in his favor; the persons prosecuted, generally, indeed, making no defences. Some of the people of this town gave in writing their reasons for not offering a defence. The jury, however, gave their verdicts without hesitation. A large number of cases were dispatched in a single day, and the costs were made very great.

Still, those who were prosecuted, and against whom executions were obtained, had one consolation. When their estates were exposed to sale, no purchaser could be found, so that they still retained possession of them.

At length the grievances of the people were past endurance, and they resolved to complain directly to the king. Nathaniel Weare, of this town, was accordingly chosen their agent, and dispatched to England.

In 1684, Cranfield wishing to raise money to relieve himself from embarrassment, under false pretences induced the Assembly to pass an act for raising the money by taxation. The constables either neglected or refused to collect the tax, and a special officer was appointed for the purpose. When this officer came to Hampton, he was beaten, deprived of his sword, seated on a horse and conveyed out of the Province, to Salisbury, with a rope about his neck, and his feet tied together beneath the horse’s body.

At the time of this transaction, Weare, the agent of the people, was in England. In consequence of his representations, censures were passed on some of Cranfield’s proceedings, and he soon after left New-England and sailed to the West-Indies.

When the revolution occurred, which placed William, Prince of Orange, on the throne of England, the people of New-Hampshire were left in an unsettled state. A convention of deputies was holden, to resolve upon some method of government. Dr. Belknap says that “it does not appear from Hampton records whether they joined in this Convention.” This statement is incorrect. The town determined to unite with the other towns in the Convention, and for this purpose they chose and instructed six delegates. The persons chosen were Henry Green, Henry Dow, Nathaniel Weare, Samuel Sherburne, Morris Hobbs, and Edward Gove. 9

At the first meeting, the Convention came to no conclusion. Afterward they thought it best to become united with Massachusetts again. Massachusetts very readily agreed to receive them till the king’s pleasure should be known. In 1692, the king having refused to allow this union, sent over John Usher as lieutenant governor of New-Hampshire.

The people in general were so well satisfied with the government of Massachusetts, that they were very reluctant to be again separated from it. They, however, submitted to the king’s order, as a case of necessity.

We have now arrived at a period upon which we cannot look back without astonishment and regret, at the infatuation which prevailed in regard to witchcraft. I cannot relate, in detail, the proceedings of courts, and of churches, too, in relation to this subject. The chief seat of the infatuation was in and near Salem. Many persons were accused of being witches, were tried and condemned. Several were executed, while others were pardoned. The delusion was not confined to the vicinity of Salem. It extended to this town, and persons here fell under suspicion, and were tried for the crime of witchcraft. “In fine,” to use the language of an old writer, “the country was in a dreadful ferment, and wise men foresaw a long train of bloody and dismal consequences.”

We may wonder that the people of that period could be so deluded; but in New-England a belief in witchcraft was then almost universal. The same belief also prevailed in England, and even took strong hold of some powerful minds. It is said that several persons were tried and condemned by Sir Matthew Hale, a gentleman of noble intellectual endowments, and great moral worth, and one of the most distinguished judges that ever sat upon the English bench.

The author of the “Magnalia,” after relating several wonderful feats, said to have been performed by those who were reported to be witches, gravely adds: “Flashy people may burlesque these things, but when hundreds of people, in a country where they have as much mother wit certainly s the rest of mankind, know them to be true, nothing but the absurd and forward spirit of Sadducism can question them.”

But this feeling has passed away, and few people now fear that they shall be called Sadducees, or infidels, for maintaining the opinion that witchcraft is all a delusion.

It would be interesting to go back to our earliest history, and trace the progress of education in the town; to inquire what methods were adopted by our fathers, to instruct the young, and to notice the self-denials and the expenses to which the people subjected themselves, to afford the means of instruction to their children. A subject so important and so interesting, must, however, be passed over with a very few remarks.

It is probable that the ministers of the gospel, who were, from the first settlement of the town, stationed here as religious teachers, improved the opportunities which were afforded them, to inform the minds of those to whom they ministered, particularly the minds of the young. To judge otherwise would be derogatory to the good sense, the intelligence, and the discretion of the ministers themselves.

But straitened as were the circumstances of the people, they as a town were not unmindful of their duties to the young. Provision was early made for furnishing them with the means of acquiring knowledge. It is, indeed, uncertain at how early a period schools were established among them; probably soon after the formation of the settlement.

There is on record an agreement of the selectmen with a school-master, made in 1649, employing him, for a stipulated sum, to instruct the children of the town daily, for a whole year, when the weather would permit them to come together. 10 It is hardly probable that a contract would have been made with an instructor for so long a term, unless schools, or a school, had been previously established. It is not unreasonable to suppose that the origin of schools here is nearly coeval with the settlement of the town. While the town was under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts, the people were required by law to maintain a free school during a considerable portion of the time. Still, it is not certain that this law went into operation here till after the date of the agreement already mentioned. Since that time, there can be but little doubt that free schools have been maintained during a part at least of every year, where opportunities have been furnished for acquiring the rudiments of an education.

The next thing I shall notice, is the Ecclesiastical History of the town.

The object of the first settlers near the Piscatqua, as already mentioned, was to prosecute the fishing business. That business has undoubtedly been carried on here from a very early period; but this seems not to have been the prime object in forming the settlement. Our fathers came hither for the enjoyment of religious freedom. One of their first movements was to secure a minister, who should be to them a spiritual guide. They came hither united in church covenant, and at the very commencement of the settlement they were supplied with a pastor. It has been handed down to us by tradition, that the church was formed, and a pastor procured, before the settlement of the town was actually commenced; and the language of our early records seems to give countenance to this tradition. The records state that, “It was granted unto Mr. Stephen Bachelor and his company, who were some of them united together by church government, that they should have a plantation at Winnicumet, and accordingly they were shortly after to enter upon and begin the same.” This purports to have been taken from the Massachusetts court records.

A fair inference from this language is that the formation of the plantation was subsequent to that of the church.

It has sometimes been said that this was the second church formed in New-Hampshire,–a church having been previously gathered at Exeter. Both churches were formed in the year 1638; but I have been unable satisfactorily to determine which may justly claim priority of date; nor is it of much consequence. This church is acknowledged to be the oldest now existing in New-Hampshire, as the first church formed in Exeter became extinct a few years after its formation, when that town came under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts. The pastor of the church was under sentence of banishment from that Province, and he retired to Wells, in the Province of Main, whither he was followed by a considerable portion of his church.

In an old book, entitled “Wonder-Working Providence of Zion’s Saviour,” the church at Hampton is said to have been the seventeenth formed in the colony of Massachusetts.

The first pastor of the church was Rev. Stephen Bachelor. He was, at the time he came hither, advanced in life, being 77 years of age. He had been a minister in England for many years. In 1632, he removed to this country, and became the first pastor of the church at Lynn. In 1638 he came to Hampton with the little band that settled here. He was pastor of this church about three years, and was removed in 1641, at the age of 80. 11 He lived to a very advanced age, and is said to have died in England, in 1661, having completed a whole century.

Mr. Bachelor’s descendants are very numerous in Hampton, and in several other towns in New-Hampshire.

When the settlement was in its infancy, a log-house afforded the people a temporary place of worship. That house was located nigh the spot where here of the subsequent meeting-houses stood; very near the present site of the academy.

At the early period of which we are speaking, the people were called together for worship by the ringing of a bell, as appears from a vote of the town, Nov. 22, 1639, when one of the inhabitants was appointed “to ring the bell before the meetings on the Lord’s days and on other days,” for which he was to have a specified sum. How interesting to the settlers must have been the sound of that bell, as its peals echoed through the forest and broke the stillness of the Sabbath morning, inviting them to assemble for the worship of Jehovah; and how strange to the untutored sons of the forest, to see the settlers laying aside their implements of husbandry, and all the tools which they were accustomed to use, resting from their labors, and wending their way, along different paths, to the log-house whence the sound of the bell proceeded.

In 1639, the year after the formation of the church, Rev. Timothy Dalton was associated with the former minister, in the pastoral office. 12 Mr. Bachelor was indeed generally designated as the Pastor, and his associate as the Teacher of the church.

Mr. Dalton came to Hampton very soon after the formation of the settlement, and it is said a considerable company of settlers came with him.

After the removal of Mr. Bachelor, in 1641, Mr. Dalton was sole pastor of the church about six years, when Rev. John Whelewright, who had previously been settled at Exeter, was associated with him. How long they were thus connected does not appear from any records which I have consulted. Mr. Whelewright was at length dismissed, when Mr. Dalton was again left sole pastor of the church. He continued in the ministry till his death.

Our records do not show what compensation was made to Mr. Bachelor, nor to Mr. Dalton, in the early part of his ministry. Large tracts of land were granted to them both. At one town meeting in 1639, 300 acres were granted to each, Mr. Bachelor having a house lot before. Grants of land were also made to them, or to one of them, at other times. It is pretty evident that at first they received no stated salary. This appears from an agreement with Mr. Dalton, in 1651, when, on certain conditions, he released the town from all “debts and dues” to him, from his first coming until he had “a set pay” given him by the town. After he had been here several years, he seems to have had about L40 per annum. Mr. Dalton is called by an old writer, “the reverend, grave and gracious Mr. Dalton.” He died on the 28th of December, 1661, at an advanced age, probably about 84 years, having been here 22 years in the ministry. Our records state that he was “a faithful and painful laborer in God’s vineyard.”

Mr. Dalton, it is well known, was the minister who gave by deed to the church and town of Hampton the property from which the ministerial funds of this town, Hampton Falls, and North Hampton, have been derived.

Soon after his ministry commenced, the town adopted measures for building a new meeting-house, of framed work, to take the place of the log-house which had served temporarily as a place of worship. By vote of the town, the new house was to be forty feet in length, twenty-two in width, and thirteen in height, between joints, with a place for the bell, which was given by the pastor.

The agreement with the contractor for building this house was mutually subscribed by the parties on the 14th of September, 1640. Soon afterwards it was determined to defray the expense by voluntary contribution. The house was not wholly finished for several years. In July, 1644, persons were appointed to ask and receive the sums which were to be given towards building it, and, in case any should refuse to pay voluntarily, this committee was required to use all lawful means to compel them. The committee was farther instructed to lay out upon the meeting-house, to the best advantage, the money they might raise. When this house was first occupied as a place of worship, is not known.

In 1649, liberty was given to certain persons to build a gallery at the west end of the meeting-house, and these persons, on their part, agreed to build the gallery, provided that the “foremost seat” should be appropriated to them, for their own use, and as their own property.

The meeting-houses first built in this town were without pews. They were constructed simply with seats; and for the purpose of preventing any disorder that might otherwise be occasioned, committees were from time to time appointed, to direct the people what seat each one might occupy.

Early in the year 1647, the church and town gave a call to Rev. John Whelewright to settle as colleague with Mr. Dalton. They stated that Mr. Dalton had labored faithfully among them in the ministry, “even beyond his ability and strength of nature.”

Mr. Whelewright accepted the invitation extended to him. The agreement made with him is dated the 12th of the 2nd month, 1647. By this agreement, he was to have a house lot, and the farm which had once belonged to Mr. Bachelor, but which had been purchased by the town. This was to be given to him, his heirs and assigns, unless he should remove himself from them without liberty from the church. The church and town were also to pay some charges and give Mr. Whelewright as a salary L40 per annum. The farm was afterward conveyed to him by deed.

How long Mr. Whelewright retained his connection with this church, is uncertain. He was here in 1656, and probably left about the year 1658.

He was a person of considerable notoriety. Hutchinson, in his History of Massachusetts, calls him “a zealous minister, of character both for learning and piety.” When residing in Massachusetts, he was accused of Antinomianism, and one of his sermons was said to savor of heresy and sedition; and refusing to make any acknowledgment, when called to an account, he was banished from the province. He then came into this vicinity, and laid the foundation of the town and church at Exeter. When Exeter came under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts, as has already been stated, he retired into Maine and resided at Wells. He remained at that place till he received a all to come to Hampton, and settle as colleague with Mr. Dalton. This took place in the year 1647. Previous to this, his sentence of banishment seems to have been removed. After his dismission from this church, he went to England, where he was in favor with Cromwell, with whom he had in early life been associated at the University of Cambridge, in England. After Charles II came to the throne, Mr. Whelewright returned to New-England, and took up his residence at Salisbury, Massachusetts, where he died November 15, 1679, aged, probably, about 85 years.

It is worthy of notice that the first three pastors of this church all lived to an advanced age—one of them dying at the age of 100, and each of the others at the age of 84 or 85 years, so that the average age of the three was not far from 90 years.

Soon after Mr. Whelewright was removed from the church, and before the death of Mr. Dalton, Rev. Seaborn Cotton was settled as colleague with the latter. His settlement took place in 1660, and Mr. Dalton died the year after.

The father of Mr. Cotton was Rev. John Cotton, one of the most distinguished of the early New England divines. He was many years settled as pastor of a church at Boston, in England. Being driven thence by persecution, he sought an asylum in this country, and soon became pastor of a church at Boston, Massachusetts. Seaborn was his eldest son, and was born in 1633, during the passage of his parents across the Atlantic, from which circumstance he received his name.

He graduated at Harvard college, Aug. 12, 1651. Dr. Cotton Mather says of him, that he was “esteemed a thorough scholar and an able preacher.”

Of Mr. Cotton’s records, only a few fragments remain, so that we know but little of the state of the church while he was pastor of it. He continued in the ministry 16 uears, and died April 19, 1686, at the age of 53 years.

During Mr. Cotton’s ministry, a new meeting-house was erected, it being the third built in the town for the use of this church. It was built in the summer of 1675, and was placed near the old house then standing. By an order of the town, all the inhabitants of more than twenty years of age were required to attend and assist in the raising of this house, under a specified penalty for neglecting to do it. The house erected at that time was the one around which a fortification was made as a defence against the Indians. It is uncertain when the house was finished and began to be occupied. The old meeting-house was taken down in 1680, having stood about 40 years.

After the death of Mr. Cotton, the church was destitute of a pastor more than ten years; a period far longer than all the other periods during which it has been without a settled minister. It must not, however, be inferred that the people had no preaching during this long destitution of a pastor. The fact probably is that they were favored with preaching nearly every Sabbath during that time, and, for a considerable portion of it, by the son of the deceased pastor, the gentleman who at length succeeded his father in the pastoral office.

Nov. 28, 1687, a committee was chosen to treat with Mr. John Cotton, to ascertain whether he would be willing to be settled in the work of the ministry and to be ordained, agreeably to the desire of the town.

Mr. Cotton probably complied with this request, so far as to preach, but not to be ordained as pastor of the church. During the ten years immediately succeeding the death of his father, he received several urgent requests from the town to be ordained. For some reason or other, he declined ordination, though he continued his preaching. For some months, however, in the years 1690 and 1691, Mr. Cotton was absent from Hampton, residing in the vicinity of Boston. He also preached three months at Portsmouth, where he was invited to settle. During a portion of the time that he was absent, Rev. John Pike, minister of Dover, supplied the pulpit here, and received an invitation to become pastor of the church. He gave some encouragement that he would accept the invitation; but probably he was unable to procure a dismission from the church at Dover, as he retained his pastoral connection with that church till his death, which occurred in 1710.

The invitation to Mr. Cotton was renewed, and after much solicitation he consented to be ordained. His ordination took place Nov. 19, 1696. He continued in the ministry till his death, March 27, 1710. At the time of his decease he was fifty-two years of age. When he was ordained there were only ten male and fifteen female members, in full communion with the church. Mr. Cotton appears to have been a very worthy man, and an acceptable and successful preacher. During the fourteen years of his ministry, two hundred and twenty persons were admitted into full communion with the church.

After his death, the people were not long destitute of a stated minister. Rev. Nathaniel Gookin was ordained pastor, on the 15th of November, in the same year.

About one year after his ordination, a new church was formed in the south part of the town, and forty-nine persons, nineteen males and thirty females, were dismissed from the first church for the purpose of being organized into the new one.

The vote, dismissing these members, passed Dec. 9, 1711, and the church was organized soon after, and Rev. Theophilus Cotton settled over it as pastor. Several years afterward, that part of the town was formed into a new town, and called Hampton-Falls.

During Mr. Gookin’s ministry, the last meeting-house was erected, which stood at the meeting-house green, near where the academy now stands. The house was sixty feet in length, forty in breadth, and twenty-eight in height, between joints. It was finished with two galleries, one above the other, as many now present will recollect; for this was the same house that was taken down in 1808, having been built eighty-nine years. The frame was erected on the 13th and 14th of May, 1719, and the house was completed, so that it was occupied for the first time as a place of worship, Sabbath day, October 18th, of the same year. This house at first was finished with only one pew, and that was for the use of the minister’s family. Other pews were added at subsequent period.

In 1725 nine persons were dismissed from this church, in order to be, probably with others, formed into a church at Kingston.

It may be proper to remark, in this connection, that the charter of Kingston was granted Aug. 16, 1694, to James Prescott, Ebenezer Webster, and several other persons, belonging to Hampton. The grant embraced not only the territory of Kingston, as it now is, but also that of East-Kingston, Sandown and Danville. The first settlers there had many difficulties to encounter and hardships to endure, on account of Indian hostilities. No church was formed at Kingston till 1725.

The church at Hampton also furnished twenty of the original members of the church at Rye. They were dismissed from this church, July 10, 1726, and the church at Rye was formed ten days after. Most of these persons, however, resided within the limits of that town, which was made up of portions of Portsmouth, New-Castle, Greenland and Hampton, and was incorporated in 1719.

An event occurred during the ministry of Rev. Mr. Gookin, worthy to be noticed on this occasion, not only on its own account, but more particularly on account of circumstances connected with it. I refer to the great earthquake, October 29, 1727. This phenomenon is here associated with the name of Mr. Gookin, from his being led, in the providence of God, to preach to his people on the very day preceding the night on which the earthquake happened, a solemn discourse, from Ezekiel vii: 7. “The day of trouble is near.”

In the course of his sermon he remarked thus:–“I do not pretend to a gift of foretelling future things, but the impression that these words have made upon my mind in the week past, so that I could not bend my thoughts to prepare a discourse on any other subject, saving that on which I discoursed in the forenoon, which was something of the same nature; I say, it being thus, I know not but there may be a particular warning designed by God of some day of trouble near, perhaps to me, perhaps to you, perhaps to all of us.”

How forcibly must these solemn words have been impressed on the minds of those who heard them, when, after only a few hours had elapsed, and while the words still seemed ringing in their ears, a low, rumbling sound was heard, which soon increased to the loudness of thunder, while the houses shook from their very foundations, and the tops of some of the chimnies were broken off and fell to the ground, the sea in the mean time roaring in a very unusual manner.

Mr. Gookin labored to improve this event of Providence for the spiritual benefit of his people, and his labors were richly blessed. Within a few months after it occurred, large additions were made to the church.

On the 19th of June, 1734, Rev. Ward Cotton was associated with Rev. Mr. Gookin, as a colleague in the pastoral office. Mr. Gookin was then in feeble health, and he lived only about two months afterwards. He died of a slow fever, August 25, 1734, aged 48 years. During this time three hundred and twenty persons were admitted to the full communion of the church.

Mr. Gookin was much esteemed by his people, who, after his death, often spoke in high terms of his worth. He was regarded as a man of good learning, great prudence, and ardent piety. He ranked high as a preacher, and his opinions in ecclesiastical affairs were very much respected by contemporary divines.

Here I shall do injustice to this people, if I neglect to mention their generous provision for the maintenance of Mr. Gookin’s widow. Soon after his death the town agreed to give her L80 a year; to furnish her with the keeping of cows and a horse, summer and winter, and to give her fifteen cords of wood per annum. They also built, for her use, a house and a barn. All this they performed as a memento of their love to Mr. Gookin, and their high regard to the worth of his widow. Mrs. Gookin was a daughter of Rev. John Cotton, her husband’s immediate predecessor in the pastoral office.

The notice I shall take of the succeeding pastors of the church will be extremely brief.

The ordination of Rev. Ward Cotton has been already alluded to. He was pastor of the church more than 31 years. He was dismissed November 12, 1765, in accordance with the advice of a mutual council. He died at Plymouth, Mass., November 27, 1768, aged 57 years.

Seven persons were dismissed from this church, September 25, 1737, in order to be formed into a church in the third parish, now the town of Kensington. The same number was dismissed, one week afterwards, to be united with them. Among these was Mr. Jeremiah Fogg, who was ordained pastor of that church November 23d, of the same year.

The fourth society was formed soon after, in that part of the town then called North Hill, but which was incorporated as a town November 26, 1742, and received the name of North-Hampton. The first meeting-house was erected there in 1738, and about the same time those members of the church residing in that part of the town requested a dismission, for the purpose of being organized into a new church. Their request was not granted. The town also refused to liberate the people there from aiding in the support of Rev. Mr. Cotton. The reason is not known. It is, however, probable that the church and town considered the formation of a new church at that time unnecessary. A council was called, that, after due deliberation, proceeded to organize the church, over which Rev. Nathaniel Gookin, son of the late pastor of the first church, was ordained, October 31, 1739.

Rev. Ebenezer Thayer became pastor of the old church, September 17, 1766, and continued in that office till his death. He died September 6, 1792, aged 58 years.

A few months after Mr. Thayer’s death, the church and town invited his son, Nathaniel, to become their minister. He did not accept the invitation. About a year afterwards they gave a call to Rev. Daniel Dana. He also declined.

After this a division arose in the town and church, which resulted in leading a majority of the town and a part of the church to declare themselves Presbyterians. They invited Rev. William Pidgin to become their pastor; and he, having accepted the invitation, was ordained January 27, 1796. Mr. Pidgin was pastor of that church a little more than eleven years. He was dismissed in July, 1807.

A minority of the town formed themselves into a society, and united with the congregational church for the maintenance of public worship, and Rev. Jesse Appleton became their pastor, February 22, 1797. As the old meeting-house was occupied by the Presbyterians, the Congregationalists made arrangements for building a new house. Accordingly, the one where we are now assembled was erected, on the 24th of May, 1797, and dedicated on the 14th of November following.

In the year 1807, Mr. Appleton was elected President of Bowdoin College; and, having accepted the appointment, was dismissed from this church on the 16th of November, in the same year. He died at Brunswick, Mc., Nov. 12, 1819, aged 47 years.

After Mr. Appleton’s dismission both churches were without pastors, and it was proposed that they should be united. Articles of union having been agreed upon, the Presbyterian church was merged in the Congregational, from which it had sprung about thirteen years before, and Rev. Josiah Webster was installed pastor, June 8th, 1808, and sustained that office till his death, March 27, 1837—almost twenty-nine years. At the time of his death Mr. Webster was about 65 years old.

The present pastor of the church, Rev. Erasmus D. Eldredge, was ordained April 4, 1838.

From these remarks it appears that this church has been organized two hundred years. During that time it has had eleven pastors. Of the first ten, six died in office, and four were dismissed. The average length of the ministry of these ten was about twenty years; for although the church, since its formation, has been destitute of a pastor about fourteen years, yet it has enjoyed the labors of two associate pastors for about the same length of time.

What important and wonderful changes have taken place during the period which we have been contemplating. If we compare our condition with that of our ancestors at the commencement of this period, in almost every circumstance we shall perceive a great alteration. The same sky is indeed spread out over us, which covered them. The same sun enlightens us by day, and the same moon by night. The same stars still beautify the heavens, and the same ocean, too, extends along the eastern border of the town; but even that is viewed with very different emotions from those felt by our ancestors, when they looked upon its broad bosom. Now, many of the little eminences within our borders afford picturesque and delightful views of the ocean and the scenery near it. Pleasant roads lead to its shore; and as we stand upon this shore, and observe the waves rolling forward and dashing upon the sand, and then look abroad upon the ocean itself, our minds are filled with agreeable sensations. We see vessels moving in various directions, and occasionally a steam-boat passing rapidly along, almost in defiance of winds and currents, having its source of motion within itself. But let us go back, in our imaginations, two hundred years, and how unlike the present! Seldom was a vessel seen off our coast; but rarely was the shore itself visited by the early settlers, as between that and their settlement were fens, creeks and marshes, rendering the way almost impassable. When they did stand by the ocean and look abroad upon its mighty mass of waters, their emotions must have been very different from ours. They were undoubtedly reminded of a place beyond the ocean; of the land of their nativity. They would naturally call to mind the scenes of their infancy and childhood—the loved scenes, the kind and affectionate friends, they had left behind, and that were separated from them by the world of waters upon which they were gazing. With their other feelings, then, must have been blended those of sadness.

But suppose we go and stand upon the sea-shore during the raging of a storm, when the water is lashed into tremendous commotion by the violence of the tempest; our feelings are indeed indescribable, but those of sublimity or grandeur are predominant. With our ancestors, other feelings must have been most powerful. When they, from their log cabins, heard the noise of the tempest; when they saw the violent agitation of the forest, as the wind moaned among its branches; and when, in addition, they heard the roar of the ocean, they must have been reminded, even more forcibly than on other occasions, of the separation to which they had been called. They then felt that an almost impassable barrier was between them and their native land.