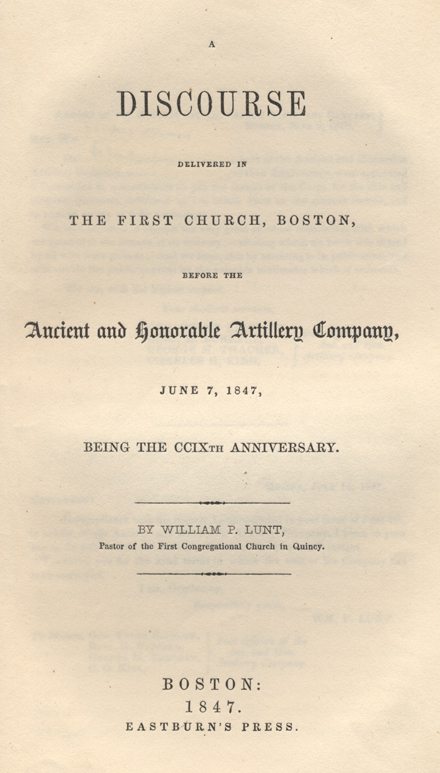

William Parsons Lunt (1805-1857) Biography:

At the age of ten, his parents sent him to an academy to prepare him for college. Lunt graduated from Harvard at the age of 18 and spent a year teaching in Plymouth. He then began the study of law in Boston, and in 1825 entered Cambridge Divinity School. In 1828, he became pastor of the Second Unitarian Church of New York City but left in 1833. For the next two years, he served as a visiting preacher in churches who needed a fill-in pastor, and then became an associate pastor in Quincy, Massachusetts, where he eventually became pastor, serving until 1856. His heart’s desire was to visit the Holy Land and walk where his Savior had walked, which he was finally able to do after he left the church in Quincy; but on that trip, he became ill, died, and was buried near the Red Sea. Across his life, he preached several notable sermons, including the funeral sermon of former President John Quincy Adams, a sermon on the great Daniel Webster, and a noted artillery sermon.

A

DISCOURSE

DELIVERED IN

THE FIRST CHURCH, BOSTON,

BEFORE THE

ANCIENT AND HONORABLE ARTILLERY COMPANY,

JUNE 7, 1847,

BEING THE CCIXth ANNIVERSARY.

BY WILLIAM P. LUNT,

Pastor of the First Congregational Church in Quincy.

ARMORY OF THE ANCIENT AND HONORABLE ARTILLERY COMPANY,

BOSTON, JUNE 9, 1847.Rev. Wm. P. Lunt,

Dear Sir:—The undersigned, by a vote of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, passed on the evening of their Anniversary, were appointed a Committee to communicate to you the thanks of the Corps for the able and eloquent discourse, delivered by you before them on the seventh instant, and to request a copy of it for publication.

We take occasion to express the very great personal satisfaction with which we listened to the sermon at its delivery;–a feeling which we know was shared by all who were present;—and we hope, that by assenting to its publication, you will enable the public to profit by the valuable sentiments which it embodies.

We are, with the highest respect,

Your obedient servants,

Past Officers of the Anc. And Hon. Artillery Company.

GEO. TYLER BIGELOW,

BENJ. H. BURRELL,

GEORGE M. THACHER,

CHARLES G. KING,

Quincy, June 14, 1847.GENTLEMEN:

In compliance with the request, communicated in your favor of June 9th, in behalf of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, I place in your hands, for publication, the discourse delivered on the seventh instant.

Thanking you for the kind terms in which the vote of the Company has been conveyed,

I am, Gentlemen,

Respectfully yours,

WM. P. LUNT.

Past Officers of the Anc. And Hon. Artillery Company.

To Messrs. GEO. TYLER BIGELOW,

BENJ. H. BURRELL,

GEORGE M. THACHER,

C. G. KING,

DISCOURSE.NUMBERS, CHAP. XXVII, V. 20.

“And thou shalt put some of thine honor upon him (Joshua) that all the congregation of the children of Israel may be obedient.”

HEBREWS, CHAP. III, V. 3.

“For this man was counted worthy of more glory than Moses.”

The words which I have just read have been selected, partly from one of the Sacred Books of the Old Testament, and in part from the Christian Scriptures, simply because they bring together three ideas, which it is the object of this discourse to treat of in connection. Moses, knowing that he must soon be removed from the earth, felt the importance of designating some person who should succeed him, as a Leader of the Hebrew people. The chief work, that of organizing the nation, and moulding the civil and ecclesiastical institutions under which they were to live,—this work had been done by Moses, the Prophet and Lawgiver. The most difficult duty of a Leader had, therefore, been already accomplished. It remained to appoint some one who should help to preserve what had been gained, and to consolidate what had been established, who should direct the energies of this compact community against their enemies, and secure for them the quiet possession of the promised land. A person competent for this office was found in Joshua, and Moses was directed to set him before the congregation. “And,” continues the divine charge to Moses, “thou shalt put some of thine honor upon him, that all the congregation of the children of Israel may be obedient.” The idea conveyed by these words seems to be, that although Joshua succeeded Moses, yet he did not,—it was not intended that he should,—fill the place of the great Hebrew Lawgiver. He had but a secondary office to discharge, and only a portion of the honor, of which Moses was the object, was transferred to him. This then may be regarded as the sentiment of the ancient Scriptures,—that the Lawgiver takes precedence of the Military Leader. But if such be the relative rank of Moses as compared with Joshua, we find a different place assigned to him when we turn to the new dispensation. A greater than Moses is here. “For this man (the author of Christianity) was counted worthy of more glory than Moses.”

Jesus, Moses, Joshua,—the inspired moral teacher, the wise lawgiver, the skilful and brave captain. The Bible, which commands us to render unto all their dues, seems to assign this relative order and rank, in the scale of honor, to the three personages I have named. And this is the order in which mankind have generally consented to esteem the three kinds of greatness represented by these individuals. It is true that this order has been occasionally disturbed in the judgments of the world; but in the long course of events men’s minds settle down upon this estimate. Sometimes there has been a disposition to rate too high the military chief. And this pernicious idolatry has encouraged wars and oppressions in the earth. But such perverted feelings short-lived. They soon yield to a sounder and juster way of thinking. What renowned master of the art of war, from “great Julius” to still greater Napoleon, occupies such a space in the world’s regard as Moses, the Hebrew legislator and statesman? Or has exerted such a powerful influence (not to speak at present of the kind of influence, but simply of its amount) upon the actual condition of the world?

And this order, which the Bible assigns, to the moral teacher, the lawgiver, and the military leader, has, uniformly and from the commencement of our history, accorded with the sentiment of New England. It is a curious fact, quite characteristic of our forefathers, that, when application was first made for a charter for the Military Company whose anniversary we are met to observe, according to Gov. Winthrop, “the Council, considering (from the example of the Pretorian Band among the Romans, and the Templars of Europe) how dangerous it might be to erect a standing authority of military men which might easily, in time, overthrow the civil power, thought fit to stop it betimes.” We might be disposed to smile at the great jealousy evinced by our ancestors towards what has always seemed to us a harmless situation, if we did know that this jealousy was connected, in their characters, with qualities to which we are indebted for all we most highly prize. Let the philosophical student of history say, to what other portion of the inhabited earth shall we turn, to find, in the early half of the seventeenth century, such a wholesome distrust of military influence, such a wise precaution with regard to any thing that threatened danger to “the civil power.” We can forgive the exaggeration which brought up before the imaginations of the Puritan settlers of New England, the lordly Templars and the despotic Pretorians, when we reflect upon the civil virtues of which they left the world such eminent examples.

And do I err, in supposing that the sentiment which was so strong in the minds of the fathers of New England, which we have seen to be the sentiment of the Hebrew and of the Christian Scriptures, which allowed only part of the honor belonging of right to Moses to be given to Joshua, and which counted the teacher of Galilee “worthy of more glory than Moses,”—in supposing that this is the sentiment of those who have invited me to address them on the present occasion? I am not standing in the presence of men whose trade is war. Pleasant as are the associations of this day to those most interested in it, I presume they all, without exception, think more highly of their civil relations and of their duties as citizens and Christian men, than of military distinction. We have never had among us a class of fighting-men, whose training has been only that of the camp of the gun-deck. It is to be hoped that we may never need or know such a class in the midst of us, and that we may not go beyond our own limits to seek an idol of this sort for the worship of our people. And we have never failed to have among us a large class of men, with strong arms and stout hearts, who, when danger threatened, or rebellion lifted its head, or the country was invaded, or our citizens were immured in foreign prisons, or the laws needed to be supported and upheld, could seize their weapons, and use them with effect. May the number of this class never be smaller.

I have remarked that the order which the Bible assigns to the three individuals already named, is, Jesus the inspired moral teacher, Moses the lawgiver, Joshua the military leader. It may be said, I know, in regard to Moses and Jesus, that they were both lawgivers and both moral teachers. They were so in a certain sense. But there is a lain distinction between them which our minds readily make. Moses was a teacher of morals. But his distinguishing peculiarity is, that he conveyed his moral influence to men’s minds, in the shape of commandments which were to be obeyed, rather than of moral truth which was designed to live in men’s convictions, and to work obedience through the action of those convictions upon the conscience, the will and the life. And so too in a certain sense Jesus may be called a lawgiver, inasmuch as he taught doctrines and principles which have ruled the minds and hearts of thousands of human beings the world over. But his was “the law of the spirit of life,” pertaining to the soul, and not the law which enjoins obedience, without regard to the state of the mind, upon penalty of suffering and death. Moses gave the world a code of laws. He went into particulars. He invented and prescribed a special form of civil and ecclesiastical polity. He organized a community and nation, and his laws extended to the minute detail of life. Christ, on the other hand, devised and enjoined no particular form of civil or ecclesiastical polity. His kingdom was not intended to be visible, or to take any outward shape; it was to be set up in the souls of men. His truth was to rule his followers through the convictions of the mind, the sentiments of the heart, and the principles of the conscience. It did not limit men’s choice to any particular modes of expressing its principles. It did not dictate any pattern for social organization. It was a spirit rather than a rigid rule. It was a new atmosphere which men were to inhale, and thereby receive and be conscious of a higher, intenser, more healthy moral life. Christ was a teacher of moral truth, and communicated it in such a shape that it should dwell in men’s minds, be appropriated by them, made their own, through faith, inward conviction, and manifest itself outwardly in whatever acts, features of character, virtues, modes of life, habits, and manners, social institutions usages, conventional arrangements and political combinations it might incline men spontaneously to adopt. In this way Christian truth, being enthroned in the mind as a principle, would operate so steadily and powerfully as to render unnecessary all express statutes. It would produce a better kind of righteousness than that which consists in literal obedience, in mere conformity to rules, the reason of which is not seen and acknowledged.

And the three individuals who have been named represent three principles which obtain in the government of the world in which we live, viz: Force, Reason, Love. These principles all enter into the methods by which Providence controls and governs the world. They all have a place, an appropriate place, in the Divine administration of the affairs of the universe. Not force alone, nor reason alone, nor yet love alone, is to govern in such a world as we are living in. Each of these principles has its sphere marked out for it, its office to perform, its part to contribute to the general end. And every theory, that would do justice to the plain facts of life, must recognize all these principles. He who is Almighty does yet not depend solely upon his irresistible power and absolute sovereignty. He is wise and just too; and would have his proceedings and laws understood and allowed to be wise and just by his rational creatures. And he seeks also, not merely to control, as he may, our destiny, nor merely, through the convictions of the rational faculty in the human mind, to extort a cold acknowledgment that his government is right and just, but to attach us to himself by the strongest affection of the heart, the love of God.

The three principles we are considering are seen operating in the government of a family. Parental authority, the right and duty, if need be, to enforce obedience, is every where acknowledged. The child is reasoned with as soon as he comes to years of discretion. And the affections of the young heart ought to be cultivated, appealed to and relied on in every Christian home. There may be ground for saying that that household is in the best condition, where no force is needed, where it is not necessary even to reason with children, to produce submission and obedience, where all is accomplished by love. But there seems to be no ground for asserting that any one of the three principles just named can be dispensed with at once and in all cases; much less can it be maintained, that either of them is inadmissible in any circumstances. And the same is true in regard to the human race at large, considered as the great family of God. He appeals to the reason or intelligence which he has bestowed upon us. He reveals himself also as our Father, and inspires us with love. But at the same time it is a fact which we cannot gainsay, and ought not to thrust out of sight, or to nullify by our favorite theories, that we are living under a system of absolute Power which is as appalling as it is irresistible. The great difficulty with many is that they take up theories, or contract prejudices, which narrow the mind’s vision and pervert the judgment. There is a place for force in the arrangements of the world. But those who have been accustomed to the use of force exclusively to govern their fellow-men, are too apt to be skeptical concerning the efficacy or practicability of any other kind of influence. The rigid disciplinarian of the quarter-deck, the “Iron Duke” of armed legions, or the stern pedagogue of the type of the last century are unable to conceive it possible to govern boys or men in any other way than by the rope’s end, or the rod, or the bayonet. The suggestion that other modes may be employed with success, would furnish proof positive, to such minds, of derangement on the part of him who should make it. And an equally narrow way of thinking is often witnessed in those who take up the notion that every thing is to be effected by reason or by love, and who exclude force from the lawful and God-appointed instrumentalities by which the world is to be controlled. Now against this narrow way of thinking, the Bible as well as human live, is a continued protest.

Force, Reason, Love. The military represents and embodies the first of these ideas, Force. The second, Reason, expresses itself in Law, understood in the largest sense; comprising common, municipal, constitutional, international Law; all those usages and customs which are the ruts in which the wheels of society run for unmeasured periods of time, until the track is worn smooth, and deviation from them is not thought of; all those express statutes and enactments which legislators make and adapt to existing and temporary exigencies in any community; all those fundamental, organic principles which are agreed on by men, in framing the particular governments under which they consent to live; all those general ideas of right and justice, the materials of an uncompiled code of catholic Law by which different nations are united virtually in a kind of world-confederacy, or what Sir James Mackintosh happily calls “the great commonwealth of mankind;” a union and commonwealth, let it be observed, in passing, which it is the tendency of civilization, especially of Christian civilization, to promote and strengthen, to make possible, and so to make actual. All these branches of Law we may properly refer to the Reason or Intelligence which God has given us, even if we adopt the theory of a separate and appropriate faculty of the human mind for the apprehension and judgment of moral facts and the moral ideas which every mind gins, of necessity, in this world, and forms them into systems, laws, commandments, and thus gives shape and body to what, through instinct, or original sentiment, or inborn principle, the Creator may be supposed to have implanted in the human constitution.

The third idea of which mention has been made is Love. This is the foundation principle of Christianity. The first commandment according to Christ is love to God. The second is like to it, love to our neighbor. And all the Law and Prophets are summed up in these two precepts. Nor does the fact that Christianity does not make use of force or of reason, to effect its intended objects, prove that it condemned the use of force and reason under all circumstances. The special work it proposed to accomplish did not require force. “If my kingdom were of this world,” said Jesus, “then would my disciples fight.” He had no outward visible polity to establish, as Moses had. Neither did he come to found a school of science, to discourse logically concerning philosophy, morals, theology, to unfold the abstruse subjects upon which the profoundest minds have been meditating, almost without result, for centuries. If this had been a chief or a prominent object with him, then would he have relied, as he never did, upon reason; he would have speculated and theorized; he would not have “taught as one having authority,” but would have shown the reason of what he enjoined upon his followers by formal arguments. Yet who pretends that Christianity condemns the use of reason or appropriate appeals to reason, or all attempts to influence men through their reason? And is there any more reason for alleging that Christianity condemns all use of force, because it had no occasions for force itself? It in fact expressly declares, that the civil magistrate “beareth not the sword in vain;” and commands its disciples to “render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s.”

I say, therefore, again, that force has its appropriate place in the government of the world. Among the attributes which we are taught to ascribe to the Deity, is omnipotent might. Nor does Christianity, the religion emphatically of love, leave out of view this dread feature of the Godhead. Christ not only presented to men’s minds the mild idea of God the Father, but warned his disciples to “fear him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.” Can the theorists of our day repeat this awful language, and then say that our religion entertains no other idea of government than love? It would not be easy to turn to a passage in either sacred or profane writ,—search, if we will, the records of the world through—of more terrible import than the words which I have quoted from the lips of him whose great law at the same time was love.

The emblem that represents the government of the world is a wheel within a wheel, as seen in the vision of God’s ancient Prophet. Force, Reason, Love, these are the principles of three kingdoms, one within another, involved in a perplexed general system, ruling men by their fears, by their convictions, and by their affections.

But in the modern Platonic Republic which the wise men of our day construct in idea, force is not admitted; it is not regarded as a legitimate agent in effecting any purpose which rational beings may aim at; it is accordingly condemned, disowned, and rejected. This way of thinking is approved by those particularly who oppose war as unjustifiable under any circumstances. War is undeniably, professedly, an appeal to physical force, to settle national differences. But force is at the foundation of all society, as society has hitherto always been constituted. Society is based upon a compulsory, not a voluntary principle. There always has been, and it would seem that there must be, allegiance to a sovereign will, however that will may be expressed, and wherever men may consent that it shall be lodged. “The powers that be are ordained of God.” Such is the form of words in which the Christian Scriptures recognize the important principle I have stated. In this language is expressed the idea of the divine right of government; not the divine right of kings; not the divine right of a republic; not the divine right of any particular form of government which men have devised or can devise; but the divine right of government, the divine right then of force. The Divine Providence allows mankind the privilege of choosing what form of government they will live under. But they are not allowed to go farther than this. They have never been permitted to choose between some government and none at all.

The right of any government to call upon those who live under its protection to contribute a portion of their substance, in the shape of a tax, for public uses, will be generally conceded. But suppose I resist the call, and choose to reason against the justice or propriety of such payment, not against the particular amount that may be assessed, but against the right to impose any amount whatever, will the officer or agent of government, who may be charged with the collection of the tax, stand and reason with me the point; or will he not proceed, in the execution of his official duty, to compel payment, by the seizure of such portion of my property, if he can find any, as shall meet the demand, and if need be, the escort of my person to the safe lodgings for such cases made and provided? Now this escort is not conducted, and this whole process, called with some humor (for the law, it seems, has its humor as well as its fictions) a civil process, is not served, by armed officials, by plumed and sworded knights, nor is it accomplished by sweet and resonant music; but in what, except these unessential accidents, does it differ from the way of “an army with banners?” It is force—physical force—the force of the stronger, compelling me, whether I will or not, whether to my mind what is required may seem rational and right, or tyrannical and unjust, compelling me to contribute my proportion to the public weal.

We hear much, (not too much certainly) concerning the horrors of war. The picture which is drawn of those horrors is not overcharged. It is all true to fact and reality. The catalogue of atrocities which war occasions is easily filled up, because those atrocities are public, notorious transactions, enacted in the open face of heaven. The passions that lead to them are such as may be indulged, through the license of the world’s opinion, without scruple. But can any reflecting man doubt, that as large, if not a still larger catalogue of what may be called the horrors of peace, such, I mean, as belong exclusively to a time of peace, such as war banishes, and may perhaps be regarded as a remedy for in Providence, might be made out? Take, for example, the times that preceded the first French Revolution; consider the state of society in that country, the morals of the people in all classes, the monstrous abuses which were not only tolerated but consecrated by the insane delusion which left, unburied and chained to the living body of society, the dead and corrupt past; and if our horror at the bloody scenes which followed is not diminished, is not our amazement less, when we trace those scenes to their true cause? Who at the present day speaks or writes of the French Revolution, in the manner of Edmund Burke, at the close of the last century, when the personal sufferings of the royal and noble exiles who carried to England all the grace, vivacity and elegance of the French Court, might well inspire a romantic interest, in their behalf, in all cultivated and generous minds? Instead of lamenting, in the musical language of Burke, that “the age of chivalry is gone,” we are disposed rather to pray that it may never be allowed to return. We can see, what the contemporaries of the great tragedy were too near to discern, that the interests of humanity required that there should be a violent social convulsion, and an overthrow of existing institutions. The soil of society must be broken up by the ploughshare of revolution and war, before it could be prepared to produce what humanity craved. Consider the thirty years of peace with which the nations of the first class in Christendom have been blessed since the career of Napoleon was terminated on the decisive field of Waterloo. And is there any thinking man among us, so blindly wedded to theory, or so afraid of betraying a good cause by acknowledging a plain truth, who believes or will assert that such a peace could have been enjoyed for so long a period, had it not been preceded by the desolating but purifying flame of war, which was allowed to pass over the earth, and to burn up the corrupt, noxious materials that had been accumulating for centuries?

Peace, then, we must conclude, is sometimes essentially promoted by war. This seems to be one of the appointments of the Divine Providence that rules in the world’s affairs. God make the “wrath of man to praise him, and the remainder of wrath he restrains.” In the story of the Hebrew champion, Samson, we read, that, after he had exerted his prodigious strength in the destruction of a lion, in one of his journeys over the same region, “he turned aside to see the carcass of the lion, and behold there was a swarm of bees and honey in the carcass of the lion.” And upon this incident he founded the riddle which he “put forth” to his companions; “out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong come forth sweetness.” This is, in truth, the riddle which the Sphinx proposes to man’s mind in all ages. Out of the fierce wars whose office is to rend, and destroy, and devour, there comes forth a better social condition of the world for man. You may say, my hearers, that this is a sad view to take of human affairs. I will not dispute with any on that point. It is sad, awfully mysterious. But we need not on that account, shut our eyes to the plain facts of life.

Moreover in regard to war, the question deserves attention, what constitutes its real evil, in the eye of the Christian moralist? We commonly confine our attention to its external signs and effects. The millions of treasure which it helps to squander, the suspension of useful arts which it occasions, the blood which it causes to be shed, the pillage, depopulation, misery, which follow in its train, these are usually set forth as the saddest signs and fruits of war. But if we view the subject from the highest ethical point of observation, it is not these external evils we shall look to, so much as to the passions out of which war springs, and which it helps to create and cherish. A Christian apostle asks, “From whence come wars and fightings? Come they not from hence, even from your lusts?” War is passion embodied in the terrific action of contending hosts. But are there no lusts and passions raging in men’s bosoms in time of peace? In a purely ethical point of view, is there much to choose between the rivalries of opposite factions and sects, the bitter feuds of social life, the brood of viperous passions that are engendered in a state of what we call peace, and the martial sentiments which inflame men on the field of battle? Are not the evils which accompany war made less by reason of the discipline which is essential to an armed host among civilized nations? Compare the warfare of two hostile Indian tribes, those Nimrods of the prairie, meeting each other in small bodies, each man singling out his adversary, and directing against some individual the fury of his whole wrath; or the battles narrated with so much spirit by Homer, which are in fact a series of personal encounters of the fiercest kind; compare these with the maneuvers and conflicts of modern armies in civilized nations, disciplined in a scientific manner, whose missiles of destruction take effect at great distances, and I presume it will be allowed that, although there may be greater sacrifice of life, in civilized warfare, (yet that is not always the case, if we take into view the comparative numbers engaged) there is less exasperation of spirit, less of ferocious passion awakened, less of brutal inhumanity, less of wanton waste of blood from the cruel love of shedding blood, than in the combats of savages or of classical heroes. And is this consideration not worthy of any regard. Does it make no difference in our ethical judgment of two scenes? Is it no gain in a moral point of view, that the improvement of military science makes a battle depend more upon skill in maneuvers, than on a desperate, malevolent, and revengeful struggle between matched foeman?

The abolition of war is far less important, in a moral point of view, than the object which Christianity aims to effect, which is to moderate and soften those dispositions of which war is an outward expression, and only one expression. The “action of the tiger” in war is no more opposed to Christianity than the stealthy venom of the serpent in time of peace. The history of the Christian Church even exhibits not a little of the war-spirit rankling in the breasts of those who have had words of peace and love upon their lips. Out of the hearts of two theological disputants, who boast that they war not with carnal weapons (though it is not easy to see why the tongue is not a carnal weapon; the Psalmist speaks of those whose tongue was a sharp sword) if there were any method of extracting the gall and malice with which they are actuated, there might be procured of anger, hatred and revenge enough to sustain quite a long campaign of modern field service. Nor if one were seeking for models of the true Christian spirit, would he be advised to go into the stormy assemblies of modern reformers, where a person must substantiate his claim to be a philanthropist by pronouncing the shibboleth of abuse.

It is alleged by some that the use of force is inconsistent with the Christian Religion, which commands its disciples to love their enemies, and to overcome evil with good. But those who produce these precepts with a view to show the unlawfulness of that particular exhibition of force which is seen in war, do not go far enough. The principles from which they reason would carry them much farther than they are inclined to go. The only persons who can consistently use these and similar Christian precepts literally, are the advocates of non-resistance, those who are opposed to any government on a compulsory principle. If any are disposed to retain the Navy of the country, “as a part of the police of the seas,” while they reason against all war as inconsistent with Christianity, where is their consistency, and what becomes of the principle which they start from? What right has any country, according to their interpretation of the Christian precepts, to establish such a “police of the seas?” Why seek to “purge the seas of pirates,” by the strong force of a naval armament? Why attempt to put down “the hateful traffic in human flesh,” by firing into the vessels employed in this traffic, and thus putting at hazard the lives of the innocent and guilty? Is the pirate to be excluded from Christ’s law of forgiveness? Is the slave-dealer not a man, that those who are in favor of a strict construction of the Christian rules, cannot give him the benefit of the command to “love our enemies?”

Besides, if the precept “love your enemies” is to be taken literally and applied to public national affairs, it is plain that it must be applied to criminal law, that it must overthrow the whole fabric of penal jurisprudence, nay, it will be found to be opposed to all legal measures for redressing wrongs or maintaining human rights. If we must take literally the precepts Love your enemies,” and “overcome evil with good,” what right have you to incarcerate the incendiary, the highway robber, the forger, the homicide? Not only the gallows must be torn down, but the question will recur, with all its original force to a conscience formed on such a construction of the Christian rules,—what right have you, on your principles, to save a human being’s life, merely that you may immure him in a stone cage; that you may take from him his liberty, which ought to be dearer to every person than life; that you may separate him from wife and children, whom he has sworn before God to support; that you may deprive him, for a term of years, perhaps during life, of the rights of a citizen; that you may shut him up with companions whose society is likely to be demoralizing, which perhaps may kill what little remains of vitality his soul and conscience may have retained?

But again, if he who consents to enjoy the fruits of crime be in part responsible for it, then it may be asked of the ultra peace men of our day, how they can justify themselves in foro conscientiae, in continuing to use whose institutions, and to enjoy those rights and privileges which have been purchased in past ages, and for which was paid the price of blood? The conscientious anti-slavery man refuses to sweeten his meals with the sugar which has been produced by the lash-stimulated labor of the negro slave of the tropics. And why should the equally conscientious anti-war man be willing to enjoy the freedom, the political privileges, the liberty to worship God in the way that he may judge right? This freedom, and these social blessings were won for us in former times by men clad in mail, with drawn swords in their hands, contending in mortal combat for the rights which they faithfully transmitted to posterity. Who ever heard of a person, by reason of his conscientious principles, his abhorrence of all war, abjuring is country, giving up home and all the social blessings he has enjoyed from his youth, and all because these blessing were procured for us, as they certainly were, on the field of battle, and at the cannon’s mouth? Among the many forms of extravagance that abound in our day, why is it that we never hear of an instance of this kind?

The Discourse thus far has aimed to show that there is a place for Force in the appointments of Providence; that it is only in such an imaginary Commonwealth as Gonzalo pictures, there is “no sovereignty;” and that if it be lawful and consistent with Christianity to employ force in upholding social order, and restraining crime, it may be used too in maintaining the independence of a nation, or in defending it from invasion. But our general speculations on the subject of Force and War need not prevent our opposition to an unnecessary, an unjust, and an inglorious war. One feature in the Reform movements of our day is the disposition to adopt the most extravagant general doctrines, for the sake of bringing to bear upon special evils the greatest amount of indignant and condemnatory sentiment. But this fails, as all intellectual, as well as all pious frauds, always must fail, of affecting the object for which they are resorted to. The finds of moderate, sober, honest persons, who love the truth, the exact truth, the whole truth, and who are disposed to rest content when they have obtained the whole, without seeking for more, such minds feel that a deception has been practiced upon them, when advantage has been taken of their real love of any good cause, or of their sincere wish to remove any acknowledged evil, to oblige them to endorse general doctrines which they do not esteem sound and true, which they perhaps detest.

But if there be, as the Discourse has endeavored to show, a place for Force, in the arrangements of Providence, there is also a place, and a much higher place for Reason. The influence which the great lawgiver exerts upon the world, by the laws and institutions which he frames, is surely of a better kind and entitled to more honor, than the skill of the great captain, who plans enterprises, and conducts men in disciplined masses, inspired with his sentiments, and obedient to his will, to the execution of his purposes. The declaration of the inspired volume finds an echo in every sound mind, when it says,—that “wisdom is better than weapons of war;”—that wisdom by which “kings reign, and princes decree justice;” which is described by the ancient Hebrew sage, as “the breath of the power of God,—the brightness of the everlasting Light, the unspotted mirror of the power of God,” as “more beautiful than the sun, and above all the order of stars;” that large, comprehensive wisdom, which looks before and after, which includes, in one survey, a wide field of objects and relations, which turns, by a well-timed word or act, the tide of events, which founds institutions whose plastic influence is felt by remote generations. “In Orpheus’s theatre,” says Lord Bacon, “all beasts and birds assembled, and forgetting their several appetites, some of prey, some of game, some of quarrel, stood all sociably together, listening to the airs and accords of his harp, the sound whereof no sooner ceased, or was drowned by some louder noise, but every beast returned to his own nature, wherein is aptly described the nature and condition of men, who are full of savage and unreclaimed desires of profit, of lust, of revenge, which as long as they give ear to precepts, to law, to religion,—so long is society and peace maintained; but if these instruments be silent, all things dissolve into anarchy and confusion.”

If the influence of Force, as employed and directed by the military leader, be most speedy and brilliant in its results, the influence of Reason or Wisdom in law, and social institutions, is most enduring. What memorials are there in the world of ancient Rome? 1 “Its martial glory,” to use the words of another, “has long since departed, but the ‘eternal city’ still continues to rule the greatest part of the civilized and Christian world, through the powerful influence of her civil codes. In every civilized country of Europe, the Scandinavian nations and England excepted, the Roman civil law either formed the original basis of the municipal jurisprudence, or constitutes a suppletory code of ‘written reason,’ appealed to where the local legislation is silent, or imperfect, or requires the aid of interpretation to explain its ambiguities.”

The ancient Scriptures furnish a striking illustration of the two kinds of greatness we are comparing, in the history, which they record, of the two nations that sprang from Esau and Jacob. Esau was a “cunning hunter;” and he afterwards became a successful military chief. He possessed himself, by force, of Mount Seir, established there a splendid military authority, and left to succeed him, a line of dukes and kings, who built for themselves a safe, and, for a long time, an impregnable fortress “in the clefts of the rock.” But what is there left now to testify of Edom? They who lifted themselves up as the eagle, and who set their nest among the stars, were long since brought low. The fierce scream of that mountain eagle was long ago silenced. And when, as a people, they passed away, they left no perceptible influence upon the world; there is nothing to show how great they once were, in any institutions, any modes of thought, any social, political, religious, moral principles, left by them as a legacy to after times. Nothing of Edom remains except the rocky city which still stands, without inhabitants, in the desert, to convince the awe-struck traveller of the truth of God’s prophetic denunciations.

Jacob too, was the father of a nation, but how different in its character and destiny, and influence upon the world, from that we have been contemplating! As different as were the personal qualities and habits of their respective founders. The Patriarch Jacob was a man of mild and gentle disposition. He “dwelt in tents;” he led a regular life, a life of quiet industry, that served to moderate the passions, that encouraged thought and reflection. His pursuits, instead of exciting and inflaming, sobered and calmed the mind, and gave room for reason and the higher sentiments to operate. While employed as a shepherd or as a “tiller of the ground,” he would receive into his soul the bland and awful influences of Nature; there would be stamped upon his mind an image of the order, regularity, obedience to fixed laws, which mark the works of God; he would experience the full power of the religious sentiment; he would see visions of angels ascending and descending above his head; he would make covenants with his unseen Guide and Protector; he would set up pillars of stone to mark as sacred, the spots where his mind had been elevated and inspired by religious ideas and emotions. And the peculiar character which was in this way formed would be communicated to his descendants. The people that traced their origin back to the Patriarch Jacob, were eminently religious, and they were governed by fixed laws. The whole civilized world has been influenced by Hebrew thoughts and principles. “Out of Jacob came the star” which still shines to guide the nations, and “out of Israel came the scepter” which is destined to bear sway through the earth.

Thus it is that Reason perpetuates itself, while Force, however violent, soon comes to an end and leaves no trace upon the world. Reason may be likened to the “still small voice,” which the Prophet heard in the holy mountain. Long after the fire, and the strong wind, and the earthquake of human passions have wasted their violence and died way in silence, the whisper of God comes down through the ages, and is heard by all listening minds to the end of time.

And if those individuals deserve honor who legislate for particular portions of the human race, still more highly should they be ranked whose large and comprehensive genius investigates the principles of general law or international morality. International law, or the extension of the rules of truth, justice and fidelity, which are acknowledged to be binding among individuals, to nations in their mutual intercourse, is the growth of modern times. It marks the Christian era of the world’s history. 2

The science of international law is, as yet, but in its infancy. Its future improvement opens to the vision of the mind a condition of the world that shall approximate nearer and nearer to the picture which prophecy has drawn of universal and perpetual peace.

While any positive institution, such as a Congress of nations, which has been proposed for the settlement of national questions, is open to strong objections on the ground that it would be likely to interfere with the independence of separate States, the labors of individual writers, whose genius qualifies them to codify the notions of justice and right which are recognized by all minds, such labors are sure to produce good results. 3 “If, says a writer on international law, “the international intercourse of Europe, and the nations of European descent, has been marked by superior humanity, justice, and liberality, in comparison with the usages of the other members of the human family, they are mainly indebted for this glorious superiority to those private teachers of justice, to whose moral authority sovereigns and states are often compelled to bow.”

An apology for war has very frequently grown out of the want of some acknowledged rule or standard of public right and justice, by which nations shall try their differences. This is a want which it is the happy tendency of civilization to supply more and more. The extended and still increasing intercourse which commerce and Christian enterprise are encouraging, among the inhabitants of different lands, helps to form a treasury of common moral ideas, ideas of what is right and just and true; and thus are collected the materials which constitute a universal reason, a world-opinion, a catholic conscience; and the stronger this becomes, the more likely will it be to supersede brute force in the adjustment of national differences. Already this moral world-power, which was wholly unknown to ancient civilization, has acquired a mighty weight. And I would ask to what work so noble, so truly worthy of the acutest, profoundest, and most comprehensive intellect, can the attention of the publicist of our day be directed, as to the task of giving form and body to the loose ideas of public right and duty that are floating in men’s minds, and which, if brought together and digested into a consistent system, could not fail of exerting a powerful and benign influence upon the destinies of mankind? That statesman or political moralist who invents a happy form of speech for fitly expressing, making current and portable, those convictions of justice and right which belong, in the ore, to all human minds, confers an incalculable benefit upon the world. “How forcible,” says the Scripture, “are right words.” “Like apples of gold in pictures of silver.”

He who puts a principle of public justice and international morality into such a shape, by the help of verbal statement, as to command assent from the minds of men educated in different countries, and under the most various, perhaps opposite influences,—who makes the principle harmonize with their convictions, and who thus gives truth the force of law to human beings in the most distant regions of the earth,—he is really the king, the ruler of his fellows. He bears sway in the world, not indeed by any visible presence, not because seated in any chair of state, not with visible tokens and insignia of authority, but by the secret, irresistible influence which he exerts upon men’s minds, upon the sources of action. And I trust I may be allowed, without the charge of impropriety, to say, in this connection, that the services of that distinguished individual, who, while occupying the office to which pertained the foreign relations of the country, adjusted a controversy of long standing with the most powerful nation on the globe, and whose pen, in that critical juncture, was the wand of Prospero allaying the tempest of war, will not, it is to be feared, be appreciated as they deserve, till an impartial posterity shall assign him the place he will occupy among the benefactors of his age.

I say, then, and will not my audience join me in this sentiment, if we must elevate above the level and measure of common mortals any human being, let it be, no the Military Leader, not the Joshua’s of the past or of the present, but the Lawgiver, who moulds the institutions of a people, and gives them an individual existence, or the moral Teacher who communicates to the souls of men universal truth, and who thus becomes the Founder of a universal empire. And this, we find, to be in fact the direction which men’s men’s sentiments have, in the long run, taken. It is Moses the Lawgiver who, in the conceptions of the world, “saw God face to face.” It is Christ, who became, in men’s belief, a part of the very Deity. If any be disposed to regard these judgments as extravagant, it must yet be allowed to be an error on the right side. If we must call it so, the mythology of Israel and of Christendom is of a far higher and more excellent kind than the mythology of Greece and Rome, which deified brute force and military valor.

Finally, while Force is the agent employed by the Military Leader, and Reason or Intelligence is appealed to by the Lawgiver, Christianity relies upon Love. Christianity, by this principle of universal love which it inculcates, by this spirit of humanity which it breathes into the soul, lays the foundation of a kind international sentiment, which cannot but modify the relations of different countries to each other, and prevent the growth of those bitter prejudices and antipathies which are sure to find bloody expression in war. The Christian precept which commands its disciples to love their enemies, that is, not to allow their hearts to harbor so much hatred and hostility to any human being, let his acts and deserts be what they may, as to be unable to exercise towards him, should there be occasion, the offices of justice, benevolence, mercy,—this precept has sometimes been objected to by unbelievers as impracticable, and such reasoners have made the precept an argument against the claims of our Religion. But if we consult History we find the great truth illustrated, that, in exact proportion as men have approximated to the temper of this precept, has been the progress of civilization and social advancement. In the savage state we seldom, if ever, meet with large nations, a great number of inhabitants living together in peace under the shelter of a common government. But they are cut up into petty tribes, few in number, ranged under their respective chieftains, and perpetually at war with each other. This has always been the case with the aboriginal inhabitants of our continent. They present to our view the picture of society broken into a great number of fragments. On the other hand it is the office of civilization, and especially of Christian civilization, to collect together these fragments, to unite them into one compact body, to multiply the ties and relations that make them one. In a Christian community men, instead of standing isolated, or in narrow circles, eyeing with jealousy and hatred all beyond that narrow line, are grouped together by millions and hundreds of millions, and their hearts learn to expand, their affections reach abroad widely, their sentiments become large, and comprehensive. And there cannot manifestly, be any large nation, without an approach to the sentiment of universal love which the Divine Religion of Christ inculcates. In accordance with this cardinal precept of love, it is the noble aim of Christianity, without interfering directly in political or civil arrangements, and without prescribing any form of polity, or establishing any visible kingdom, to form a communion of man with man the world over, irrespective of place of birth, of color, or of race. And our best hope for the world must be that this Christian idea of communion, of a community, may be realized more and more perfectly. It has already proved fatal to many of the odious inequalities and oppressions that have afflicted our race. Christianity was sure, if its doctrines and maxims were received, to result in free political institutions. And the more fully the Christian idea of communion is understood and acted on, the stronger, more permanent, and safer will be the basis upon which society will rest. Stronger than all external bands of mere force, is that communion of feeling which grows out of the love which our Religion inspires.

In the early period of the history of society, the sentiment is quite weak. Communion, or what resembles it, is known only among the members of the same family circle, or of the same tribe. In course of time the sentiment extends, and becomes the binding principle of neighborhoods and small societies. Then it extends still farther and becomes the basis and cement of large Commonwealths. And finally the sentiment grows so as to link together the inhabitants of different countries, and it is a cheering fact that this international sentiment, this communion of man with man, exists as an element of modern society, and that it is continually growing stronger. Nor let it be imagined that the Christian principle of love has yet reached its full, intended expansion. The enlarged and still enlarging intercourse of the human race must effect changes in the condition of man upon the earth, and of governments in their relations to each other, the nature of which we cannot foresee or predict. It will be likely to modify essentially men’s notions of patriotism, of exclusive allegiance to any one government, and of national independence, ideas which have hitherto been held with a jealous tenacity.

But whatever may be our particular speculations on these points, we cannot refuse to entertain the vision, which has ever been seen by hopeful minds, of a period, in the coming ages, of perpetual and universal peace, when the trumpet shall be hung in the hall, no more to bray its harsh summons to conflict, when the arts of peace, the earth over, shall “beat men’s swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks.” Grant, if you will, that this is but a vision, a dream of philanthropy. That is no reason why it should be sneeringly rejected. It has gladdened and strengthened the hearts of the good and of the wise too, in every generation. Blot out, if any are bold enough so to do, from the pages of Scripture, the prophesy which foreshows this blessed era, still some similar promise would before long, be uttered from the depths of man’s soul. That soul is ever prophetic of good, through the principle of hope which God has implanted in it. Tossed as human beings are on a flood of restless, boisterous waters, hope brings to the ark, in which the interests of the race are floating, a sign of some Ararat on which man shall rest at last, and the bow of God upon the black cloud is cheering token of serene skies that are yet to smile upon the world. We cannot afford to dismiss this hope from our hearts.

Gentlemen of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, if I were to assert that our fathers were the authors of and deserve the credit of originating a citizen-soldiery, some perhaps might not assent to the entire truth of such a claim, And yet, if it must be conceded that they only continued in use what had existed to some extent, and in a certain form, in their native country, we may certainly claim for them what is, practically considered, as important and as honorable to their character, that they gave a prominence and assigned an office to the institution of a citizen-soldiery, by making it a substitute for a standing army, which it had never had before. It was a favorite idea with them to train a body of men, who, without making war a trade, without foregoing the peaceable pursuits of industry, without dropping the character, the manners, the sentiments of citizens and of Christians, should yet be enrolled in bands of convenient size, and learn the use of arms, and submit to the necessary subordination and discipline of an armed host, and be ready, on any exigency and in a righteous cause, not for the sake of fighting, but because a sacred duty to the common weal impelled them, to practice their acquired skill, and to put to hazard their lives. If this was, for all practical purposes, a new thing among the nations, if the Puritan settlers of this Continent brought into use an instrument for maintaining social order and stability, which should effect the good objects proposed, without incurring the danger which had usually accompanied a resort to force, then, gentlemen, your Company, which was the first enrolled on this continent, is deserving of honorable mention in the history of civilization. Your anniversary, in that case, deserves to be noticed, not merely as the annual and pleasant gathering of a band of friends, but as one of the signs marking the opening of a new era in the progress of man. If we can say of the Fathers of New England, that they were the authors of the free Common School, for the instruction of the children of the people, and that they entrusted to the people themselves, their own defence as citizen-soldiers, then have they given to the world two institutions which have exerted an incalculable influence in favor of the prosperity, the improvement, the Christian peace and stability of modern society.

We will honor them for this. And we will hope and pray that the place which they assigned to military talent, as compared with other higher and more sacred forms of service to society and humanity, may ever accord with the sentiment of New England.

Endnotes

1. Wheaton’s History of International Law.

2. Among the Greeks and Romans a foreigner was regarded as a barbarian and an enemy, and was treated accordingly. With the Hebrews, foreigners were all included under a common term of reproach as Gentiles, and if they escaped hatred and contempt, were not placed upon an equality with the chosen people.

3. Wheaton’s History of International Law.

*Originally Published: December 20, 2016.