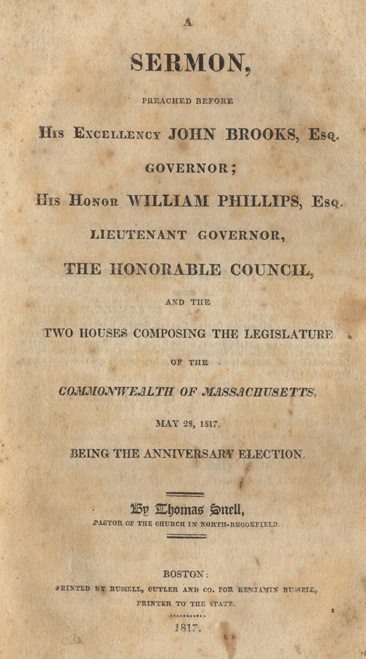

This election sermon was preached by Rev. Dan Huntington on May 12, 1814.

A PEOPLE

A

SERMON,

PREACHED AT THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

HARTFORD,

MAY 12, 1814.

BY DAN HUNTINGTON,

PASTOR OF A CHURCH IN MIDDLETOWN.

HARTFORD:

PRINTED BY HUDSON AND GOODWIN

1814.

ORDERED, That the Hon. Asher Miller, and Elijah Hubbard, Esq. return the thanks of this Assembly to the Reverend DAN HUNTINGTON, for his Sermon preached before this Assembly on the 12th day of May instant; and request a copy thereof that it may be printed.

Examined by

THOMAS DAY, Secretary.

PSALM cxxii. 6.

They shall prosper that love thee.

THE object placed before us in this promise is prosperity. The affection connected with, and leading to it, is love. The context shows us that it is the love of Jerusalem. “They shall prosper that love thee.”

The Psalm which contains these words was written by David, to be publicly sung by his countrymen assembled in that capital, to celebrate some public festival. “Our feet” they said, “shall stand within thy gates, O Jerusalem. Jerusalem is builded as a city that is compact together: whither the tribes go up, the tribes of the Lord; to the testimony of Israel; to give thanks unto the name of the Lord: for there are set thrones of judgment; the thrones of the house of David. Pray for the peace of Jerusalem. They shall prosper that love thee.”

WHAT IS INTENDED BY PROSPERITY? And

WHY MAY IT BE EXPECTED IN THE WAY HERE MENTIONED?—These are the two leading inquiries which will now direct our meditations.

By prosperity, we commonly understand success in our exertions, or the attainment of our wishes. If favoured in our enterprises, be they what they may, we think ourselves prosperous. In this general sense, the term is often used in the scriptures; and is there applied to the enemies of God, as well as his friends. The wicked are there represented, in many instances, as gratified to the extent of their most sanguine hopes. “They have more than heart could wish. They increase in riches. Their eyes stand out with fatness. Their strength is firm. They are not in trouble as other men; neither are they plagued like other men.”

Affluence, popularity, talents, health, long life, and an easy death, are often granted to the very basest of men. The unprincipled libertine, the sordid worldling, the wretch who would rise to influence upon the ruin of his country, the unbelieving and abominable of every description,–“who set their mouth against the heavens, and say—how doth God know, and is there knowledge with the Most High?—Behold these are the ungodly that prosper in the world.” They, as often as others, perhaps, have the attainment of their wishes and exertions, in whatever they set their hearts upon for happiness. Such prosperity, however, is undesirable. It is “the prosperity of fools,” which “shall destroy them.” “I was envious at the foolish,” says the Psalmist, “when I saw the prosperity of the wicked: until I went into the sanctuary of God: “Then understood I their end.”—When they have done the work, for which they were raised up; accomplished the period of their trial; and their characters are sufficiently developed, “they are brought into desolation in a moment;” and the advantages, with which they have been favoured, but have abused, all turn against them.

On the other hand, desirable prosperity is the attainment of our wishes, in whatever is conducive to real, permanent happiness. This is the prosperity, promised in the text; and is applicable, both to individuals and communities. The promise, you notice, is without limitation. It is as much as to say, all shall prosper, in whatever connexion, or under whatever circumstances, we contemplate them, who have the qualification mentioned.

As applied to individuals, it imports, that their souls shall be in health: it applies, peace of mind: reputation: property, so far as it is a blessing:–all, in short, that contributes to substantial enjoyment in life; consolation in death; and blessedness in immortality. Strictly speaking, it implies advancement in all these things: or the means of happiness, in a progressive state. This prosperity, being peculiar to the friends of God, is what we find spoken of in his word, as enjoyed by his servants, eminent for piety. Thus, it is said of Joseph, that “the Lord was with him, “and he was a prosperous man.” So it is said of Solomon, that “he prospered:” of Hezekiah, also: of Daniel: and of others.

As applied to communities, everything is included in the promise, which is conducive to national glory and happiness. That people may be said to prosper, who, elevated as to their national character, and happily exempted from national judgments, are, under the divine smiles, making improvement in their laudable pursuits; and who, aiming to regulate themselves by the great and leading principles of revealed religion, feel, in every grade and department of life, the benign influence of those principles.

Unmingled happiness, indeed, derived from these sources, to people have ever yet found, nor may ever expect to find in a world of sin. The promise of the text includes as large a portion of happiness, both private and social; political and religious; as may be expected to fall to the lot of mortals, in the present state. And who does not desire such prosperity? Who, that has the feelings of a man, does not wish it, for himself? Who, that justly claims the character of a patriot, does not wish it for his country? How readily are they, that have been the instruments of procuring it for us, whether in public, or in private stations, requited with our gratitude, our esteem, and our confidence!—And not without reason: for prosperity, we see, in the best sense of it, is increasing happiness. Our next enquiry is,

WHY MAY IT BE EXPECTED IN THE WAY MENTIONED IN THE TEXT?

But what is that way? Whence are we encouraged to hope for this prosperity? Is it a thing of chance? Is it to be derived from human means? Is it the effect of good calculations merely? May it be expected, from common endowments and efforts? Shall we look for it, from armies, and from navies? Shall we look for it, from splendid achievements in the field, or from brilliant talents in the cabinet? Good is the word of the Lord, “Let not the wise man glory in his wisdom; neither let the mighty man glory in his might. Put not your trust in princes, nor “in the son of man, in whom there is no help.” The promise is to none of these. It is, as has been observed, to those, that love Jerusalem.

The literal Jerusalem, it will be remembered, was redeemed by David, the captain of the hosts of Israel, out of the hands of the Jebusites, to be God’s city; the holy place of his rest; where he would dwell forever. It was the place of the royal residence, and the city of the Jewish solemnities. There was the throne of the house of David. There was the temple. There the Most High established his worship. Thither the tribes resorted. There was statedly heard the voice of praise and thanksgiving. It was a place, for the protection of which, God repeatedly, and in a wonderful manner, interposed by his providence. The extraordinary regard, which he was pleased to testify toward it, ennobled this metropolis, above all other cities, however populous or magnificent. It was a city which, however contemptible, at times, it might appear, in the eyes of the world, was favoured with the special presence of her God. Here, by pouring out his soul a sacrifice, the beloved Saviour made atonement for the sins of the world. Here, was first heard the glad news of reconciliation with God, for penitent sinners in the name of Jesus. It was the city, which God had appointed to be the place for the first gathering of the converts to Christianity, after the ascension of the Saviour: the place of that remarkable effusion of the Holy Spirit, on the Apostles and primitive Christians, which took place, on the day of Pentecost: the place, also, whence the Gospel was to sound forth, into all the world. What it was, however, is but of little importance to us, since it has lain, now, for many centuries, in ruins, excepting that it was a lively emblem of the Spiritual Jerusalem. It was, doubtless, in all these respects, the most eminent type of the Christian Church, with which the people of God were formerly favoured. Accordingly, when speaking of the Church of God, how often do the sacred writers call it by the names Jerusalem; and “the city of the living God!” Unclothed of metaphor, then, the promise is to those, who have at heart the great interests of the Redeemer’s kingdom. That people will be truly prosperous, where the Gospel, and its institutions, are suitably regarded; and where the religion of Christ, in its several branches, is treated, as being what it is, “The one thing needful.” These, as will be more fully seen, in other parts of the discourse, are the things included in that love of Jerusalem, which is the condition of the promise.

It is evident, then, whence we are to look for prosperity. The enquiry now returns with force—Why are we to look for it, in the way here mentioned? Principally, I think for two reasons. Because it is the way, in which it always has been obtained: and because in the temper of heart, implied in the affection here specified, and in that tenour of life, which is the natural fruit of it, are found the only ingredients of true prosperity. It is the way, in which it always has been obtained.

That communities, as well as individuals, have ever enjoyed prosperity, in proportion to their attachment to the cause of God, in the world, and to their zeal in promoting its interests, is a fact which, from investigation, will be found incontrovertible. The experience of all past ages, in concurrence with the declarations and promises of Jehovah, evinces it. “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” equally to nations, as to individuals. “Them that honour me” saith the Most High, “I will honour.” “If ye be willing and obedient, ye shall eat the good of the land,” is a promise, by no means limited to Israel. Look the history, however, is more replete with instruction upon this point, than that of the Jews. Contrast their condition, then, with that of the nations around them, and you see the subject strikingly illustrated. “To them, pertained the adoption; and the glory; and the covenants; and the giving of the law; and the promises.” They were exalted to heaven, by their privileges, which they, often, shamefully abused. They, sometimes, fell into unbelief and idolatry. But as a people their attachment to Jerusalem was habitually ardent; and their prosperity, in conformity to the promises of God, was answerable to their piety.They, sometimes, fell into unbelief and idolatry. But as a people their attachment to Jerusalem was habitually ardent; and their prosperity, in conformity to the promises of God, was answerable to their piety.

The promises made them, were such as the following: “If ye walk in my statutes, and keep my commandments and do them; then will I give you rain in due season, and the land shall yield her increase, and the trees of the field shall yield their fruit: and your threshing shall reach unto the vintage, and the vintage shall reach unto the sowing time; and ye shall eat your bread to the full, and dwell in your land safely. And I will give peace in the land, and ye shall lie down, and none shall make you afraid. And ye shall chase your enemies, and they shall fall before you by the sword. And five of you shall chase an hundred, and an hundred of you shall put ten thousand to flight. And I will walk among you; and will be your God, and ye shall be my people.” These, and promises similar to them, were renewed, and often repeated to this people. What can be more explicit? But so exactly were they accomplished, that what is contained in them may be considered a king of prophetical abstract of their future history. So apparent was it, that the Lord was with them, to protect and bless them, that surrounding nations stood in awe of them. The remarkable prosperity, that attended them, in everything, convinced those, who beheld it, that they were under the immediate care of the God, whom they worshipped, and whose covenant people they professed to be.

We find an illustration of the same fact, from comparing particular periods, in the history of this people, when religion pervaded the different ranks in society, with other periods, when religion was generally neglected. What prosperity attended them, for instance when they came up, a handful comparatively, but came up in the strength of the God of armies, to take possession of Canaan! “The hearts of their enemies,” whither they went, “the kings of the Amorites, and the kings of the Canaanites, even melted,” when they heard what the Lord had done, and was doing for them. “The very stars, in their courses, fought for them,” till having completed their victories, and overcome innumerable difficulties and dangers, they obtained quiet possession of the goodly land, an inheritance for themselves, and their children. Their pious leader at the close of life, having assembled the elders of Israel, their heads, their judges, and their officers, is careful to remind them of the covenant faithfulness of God, in all this, and to impress it upon them, that their future prosperity would depend upon the continuance of their obedience. “Behold,” says Joshua, “this day, I am going the way of all the earth, and ye know, in all your hearts, and in all your souls, that not one thing hath failed of all the good things, which the Lord your God spake concerning you: all are come to pass unto you, and not one thing hath failed thereof. Be ye therefore very courageous, to keep, and to do, all that is written in the book of the law of Moses, that ye turn not aside therefrom, to the right hand, or to the left. But cleave unto the Lord your God, as ye have done, unto this day.” As their success, in every laudable undertaking, had hitherto been according to their reverence for God, and his institutions, so should it be, in all future periods. And so it proved. How exactly was it, according to the word of the Lord, by his prophet! “The Lord is with you, while ye be with him: and if ye seek him, he will be found of you, while ye be with him: and “if ye seek him, he will be found of you, but if ye forsake him, he will forsake you.” While they manifested a holy zeal for God, and for the honour of his house, they were, eminently, that happy people, whose God is the Lord.” When they sought him, he was found of them, and delighted to own, to bless, and to build them up. On the other hand, when they generally violated their covenant obligations, became unmindful of the God of their mercies, and forsook him, then did he forsake them. Forsaken have they now seen, for ages, and, in their different dispersions, stand as an awful beacon, to warn men everywhere of the danger of disobedience and unbelief.

From what has taken place, since the Messiah’s advent, we gain still further proof of the point in question. Why have nations, professedly Christian, been preserved, like God’s chosen people of old, through a series of ages; and though comparatively feeble, and unprotected by any human arm, been highly elevated; while the great pagan empires of the East, by an influence unseen, have been successively crumbling into atoms? Any why, in civilization, in refinement, in liberty, in religion, and in everything, that stamps dignity upon the character of a people, and renders existence a blessing, have the reformed nations of Europe been distinguished from those, that have been led away, by the delusions of Mohammed and the abominations of Antichrist? Are we at loss for an answer? We have it, in the text. “They shall prosper that love Jerusalem.”

The nations, that have enjoyed this prosperity, were the lovers of the Lord, and of his interest. They were careful to maintain a reverence for divine institutions. “The Sabbath was their delight, and the holy of the Lord, honorable.” Their children were brought up in “the nurture and admonition of the Lord.” Unwearied pains were taken, to render them pious. Seminaries were extensively established, and liberally patronized to educate them for the service of the church. Faithful ministers, devoted to the business of their calling, and honourably supported in it, proclaimed the gospel message, with success. The love of Jerusalem warmed the hearts of the Legislators and Magistrates, and animated their exertions, in everything, that was laudable. Indeed, we need not go abroad, for illustration of the fact. We see its truth, in our own country. So obvious, and so striking is it, that the traveler, as he passes, can almost mark with his eye those districts, where the institutions of religion have been for any length of time regularly observed: and those, where the degraded inhabitants, in a Christian land have chosen to live like heathen. Thus, events, as they have hitherto taken place, in the world, are so many monuments, erected by the hand of heaven, for the benefit of succeeding ages. They lay open and help us profitably to explore the sources, both of prosperity and adversity. They solemnly admonish us, to avail ourselves of the means by which the latter may be avoided, and the former secured.

I am aware, that it will be said by some, prosperity is by no means confined to nations, enjoying the blessings, and regulating themselves by the principles of revealed religion. Others have enjoyed it. What others? Is it true, of the great pagan empires of antiquity? The last, and most flourishing of these, was the Roman. This was an extensive, and a wealthy dominion. The people were far advanced in many of the arts of civilized life. But were they, what is denominated by the Spirit of God, prosperous? Were they happy? Could that people be happy where lust and cruelty were not only practiced, but licensed; where human sacrifices loaded their altars; where deformed children were murdered; and where the shows of gladiators cost them more lives, than the most bloody wars? These, and the like enormities, in that day, were common.

Among modern nations, as examples of prosperity, without Christianity, China and India, are sometimes mentioned. They, also, are great, I allow. They are powerful and politic. They are ingenious. Their soil is fruitful, and they are favoured with the commerce of all civilized nations. They have been, particularly the former of these empires has been happily exempt from bloody wars. It has existed for ages, unsubdued. After all, what is the condition of China? As to moral and social character, they are, as a people, singularly debased. With respect to many of their customs, decency must blush, and humanity shudder to behold them. Nor is the eye relieved, at all, by being turned to the neighbouring country, that has been mentioned; where delusion holds, if possible, a more extensive sway; where infanticide is common; where a family of children, when by the providence of God, they have lost one parent, are left doubly orphans, deprived by a barbarous superstition of the other: where to avoid the scorn and resentment of nearest relatives, tens of thousands, of wretched females, are yearly compelled to ascend the funeral pile of their husbands, there to be burned alive, their own children kindling the fire, whilst their agonizing shrieks are drowned by the noise of drums, and the savage shouts of surrounding multitudes. 1

But we need not examine, too closely, the dark shades of the picture; we need not go far, into “the chambers of their imagery,” to understand the state of society, among this people. Their delusions, their horrid rites and ceremonies, are familiar to our ears. With all the advantages indulged them, prosperity is not theirs. When these examples are mentioned, to invalidate the doctrine contended for, it seems to be forgotten, that the happiness of nations depends more upon their moral habits, than upon any natural endowments, or political greatness.

From what we have yet seen, then, of the dealings of God with communities, in times past, we resume the ground that was taken, under this head of argument, and say, that he will continue to prosper those, that love Jerusalem, and in direct proportion to their love, because he always has done it. That he will do this, we may believe, also, Because in the temper of heart, implied in the affection, here specified, and in that tenour of life, which is the natural fruit of it, are found the only ingredients of true prosperity. THEY SHALL PROSPER THAT LOVE THEE. The affection here specified is LOVE. In this affection abstractly considered, is implied every quality, that assimilates the creature to the Creator, who, when described, in the whole assemblage of his perfections by a single term, is called LOVE. It is an affection, which, as it “is the fulfilling of the law,” embraces all the essential principles and duties of real religion. It imports a sound faith, and a life of obedience: purity of heart, and unspotted manners: godliness and honesty: the bridling of the tongue, and the government of the passions: a sincere profession of religion, in short, and a correspondent practice. Inspired with this affection, the glory of God, the honour of the Redeemer, and the good of souls, rise superior to every other consideration. Beholding the transcendent beauty, reflected from such objects, they who are thus favoured, look down with disgust, upon the pursuits of sin. Captivated with the scenes, continually unfolding themselves, and with the objects passing in review before them, under the government of the Most High God, they not only rest satisfied that all things are in good hands, but their hearts are lifted up in joy, admiration, gratitude, and praise. “They rejoice in hope of the glory of God.” Animated by the “hope, which entereth into that within the vail,” they set a just estimate upon the world and the things of it. Having in them, “the same mind that was also in Christ Jesus,” their ardent desire, above everything, is to be found faithful to their Master by doing good to all men, as they have opportunity. Feeling, in their own souls, the blessings of the great salvation, they long to have all men, partaking with them. Their hearts burn, with the most ardent desires; their fervent prayers are poured forth; their hands are opened to contribute; their services are offered; that the Redeemer’s name, and salvation through him, may be known as far as the earth is inhabited. Under the impulse of such a principle of action, they cannot fail to be useful. If called to fill stations of power and trust, their influence is “as the light of the morning, when the sun ariseth, even a morning without clouds: as the tender grass springing out of the earth, by clear shining, after rain.” “How beautiful, upon the mountains, are the feet of him so,” cloathed with such a spirit, “bringeth good tidings of good,” to the perishing; “that publisheth peace and salvation; that saith unto Zion, thy God reigneth!” And in every condition, whether humble or exalted, “Whatsoever things are hones; whatsoever things are just; whatsoever things are pure; whatsoever things are lovely; whatsoever things are of good report,” they all grow, as natural fruit, from this spirit of Love. We need not enquire, therefore, why communities, made up of such characters, and where such an affection predominates, are prosperous. All the necessary ingredients are inherent in the very constitution of such bodies, which can promote prosperity. To such communities, as well as to such characters, the Apostle Paul says, “All things are yours.” “The righteous Lord loveth righteousness,” and will never fail to be “the rewarder of them, that diligently seek him.” Where “pure and undefiled religion” is maintained among a people; where the true God is known and adored; where his law is acknowledged as the proper standard of morality; where guilty mortals, feeling themselves condemned by it, fly to the gospel of his Son, as “a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation;” where the ordinances of the gospel are generally observed, with implicit faith in their adorable Author; and where, as the natural effect of the gospel spirit, thus prevalent, the rising generation are trained up for God; where human laws are good, and faithfully executed; where qualifications for office are properly attended to; and the duties of office are properly discharged; that people are the secure of all that can rationally be desired.

The argument gains strength, too, I think, from considering, a little more minutely, the precise object, to which the affection here specified is to be directed. It is Jerusalem; by which, as we have seen, is intended the church of God. To his redeemed church, and covenant people, the ever blessed God has always sustained a peculiar relation. It is a relation, which will never be dissolved. Accordingly, we uniformly find him expressing the most tender regard for them. “They shall prosper,” therefore, “that love Jerusalem,” because, in loving her, they love what God loves. Their affections meet and centre in the same object. Jerusalem, the church of God, is, emphatically, the beloved city. The plan of it was in the divine mind, from eternity. All that is passing before us, in the kingdoms of nature, of providence, and of grace, are but parts, included in this plan. Before the world was, God determined to make a display of his rich grace, in Christ Jesus, by erecting and completing such a city. It was in view in creation; it was, all along, in view, in the great work of redemption; and all events have hitherto rolled on, with reference to it, in the government of the world. It is, not only altogether the most important of the works of God, other things are important, only as they bear relation to it, and help it forward. The materials for it, gathered from the ruins of the fall, God has been preparing, and bringing together, in different ages, with reference to the final consummation, which shall be, “to the praise of the glory of his grace.” “God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth,” but determined that his own glory should not, on this account, be the less conspicuous. His purposes must be accomplished. “From Zion was to go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem,” that the ravages of sin might be counteracted; that those lusts and passions, which would otherwise, keep the world in confusion, might be restrained; that many sons and daughters might be brought home to glory; that finally the world might be regenerated; and thus the machinations of the Devil be defeated; and that, thus, also, “unto principalities and powers in heavenly places, unto angels, as well as unto men,” might be known by the church “the manifold wisdom of God.”

This city is peculiarly the residence of the living God: and hence, in answer to her supplications, he makes all the most glorious displays of himself, that are ever made, in the world. It is a city which, in answer to the prayer of faith, has been “enlarging the place of her tent,” and “stretching forth the curtains of her habitations,” in defiance of all opposition. “The kings of the earth have set themselves, and the rulers have taken counsel together, against the Lord, and against his anointed, saying let us break their bands asunder, and cast away their cords from us.” The cry of the pagan idolater of the unbelieving Jew, of the beast, and of the false prophet, concerning this feeble, and apparently contemptible city, has been “raze it; raze it; even to the foundations thereof:” but always, hitherto, have they found themselves disappointed. “Having, for its foundation, the apostles and prophets;” having “Jesus Christ, as the chief head and corner stone;” it still lives, and rises into “an holy temple of the Lord:” a temple, in which every believer is a “lively stone;” a temple which grows, with every revival of religion; and with the conversion of every redeemed soul; and which finally, embracing every child of God, of every age and nation, will become, in a peculiar sense, “an habitation of God through the Spirit,” where he will be worshipped, in a pure and perfect manner forever. Never will he forsake the city of his love. Never will he abandon those, who have an attachment to her. Never will he forsake the dear people, for whom the Redeemer bled, and on whose behalf, the Holy Ghost was sent down. As God is faithful to his promises, “They shall prosper.” “Behold! Saith the Lord,” to Jerusalem, “I have graven thee, upon the palms of my hands, thy walls are continually before me.” “No weapon, that is formed against thee, shall prosper, and every tongue, that shall rise against thee, in judgment, thou shalt condemn.” “Glorious are the things, spoken of thee, O thou city of God!” Happy are all they who, enrolled as thy citizens, have for their friend and father, the God who is in the midst of thee! With Balaam, therefore, may we not take up our parable and say, “Surely there is no enchantment against Jacob, neither is there any divination against Israel! How shall we curse, whom God hath not cursed; or how shall we defy, whom God hath not defied? Behold! We have received commandment to bless: He hath blessed and we cannot reverse it.”

A direct inference from the whole is, that Where there is not a love for Jerusalem, that people cannot prosper. If there be a God, and if not, “let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we die”—if there be a God, “who loveth righteousness, and who hateth iniquity,” they cannot prosper. As his declarations are true, they cannot. As the promise, in the text, together with others, that speak the same language, have any meaning in them, they cannot. They cannot prosper in the nature of things. Communities, made up of irreligious characters, “who regard not the work of the Lord, neither consider the operation of his hands,” contain within themselves all the materials of wretchedness and dissolution. For wise reasons, they may be permitted to exist, and for a time to flourish, as we often see, but they cannot prosper. They cannot be happy. Nothing gives permanent peace, real happiness, or that which deserves the name of prosperity to a state, but the influence, derived from the purposes of God’s redeeming love in Jesus Christ, extensively diffused and felt, through its different departments.

By the mere politician, whose views are limited to the present condition of man; who sees, in the great events, that are taking place, in the world, only the workings of human passions; and who looks for the destinies of Empires, no higher, than to the fellow-worm, who fills the chair of state, such a sentiment, I know will be spurned, as weak and visionary. I do not, however, retract the suggestion. Let the luke-warm professor start at it, and let infidel sneer, if he will; but let them know from God, that accursed is everything, which is not in subserviency to the interests of the Redeemer’s kingdom. That “sin is a reproach to any people”; that obedience to the divine institutes shall e rewarded; and that disobedience shall be punished; is the general tenor of the word of God. “Hath he said, and shall he not do it? Hath he spoken, and shall he not make it good.” “Thus saith the Lord of hosts, I am jealous for Jerusalem, with a great jealousy.” He is jealous for her honour, as he is for that of his own name. He watches over her continually. He notices what is done, both for and against her. His love, and endeared relation to her, will not permit him to overlook any circumstance, either of injury or neglect. Under his government, therefore, communities, where the interests of his church are, for the most part, excluded; where her sacred institutions, to say the least, are treated with cold indifference by the multitude; where his very being is not acknowledged; where his perpetual and universal providence is not regarded; where his authority is not felt; and where, as the natural effect of all this, gross immorality is rampant, cannot long flourish. They may have the appearance of prosperity, for a time, but “Their root is as rottenness, and their blossom shall go up, as the dust, because “they have cast away the law of the Lord of hosts, and despised the word of the Holy One of Israel.”

The covenant with Israel was, indeed, in some respects, peculiar, and no other people is governed, exactly, according to the same rule. God, however, deals with nations everywhere, as collective bodies: and to all who believe in his existence, and are favoured with his revealed will, as their guide, he says, as to his people of old, “If thou wilt not hearken to the voice of the Lord thy God, to do all his commandments, and his statutes, which I command thee, this day; cursed shalt thou be in the city, and cursed shalt thou be in the field. Cursed shall be thy basket and thy store. Cursed shalt thou be, when thou comest in, and cursed shalt thou be, when thou goest out.” Individuals will exist, and be judged, and be recompensed, in a future state: but collective bodies, having no future existence, will, therefore, be recompensed in this world. And as a tender regard to the cause of God, in the world, ensures national prosperity; so impiety, especially, where churches are established, and the ordinances of the gospel are enjoyed, will inevitably end, in the ruin of a people. In that government, which is to stand, and for any length of time to be happy, in the enjoyment of the divine smiles, there must be “pure religion”; there must be a careful attention to the soul; there must be a love for Jerusalem; and a sincere attachment to her interests, interwoven in its very contexture.

The world stands, as a theatre, on which the mighty work of redemption is carried on, until that work shall be accomplished. Civil government is an ordinance of God, instituted with express reference to this kingdom, and is to be administered, in subserviency to its interests. If it be not administered for Jehovah, it is against him, and will certainly incur his malediction. The potentates of the earth, be they good or bad men, wise or foolish, are raised up, with reference to this kingdom, and are employed in carrying on the dispensations of the Most High, towards his people, either of mercy, or of judgment, as their obedience, from time to time, pleads for the one, or their transgressions call for the other.

Two grand and leading interests divide the whole order of intelligent creatures, that of Him, “who hath on his vesture, and on his thigh, a name written, King of Kings, and Lord of Lords”; and that of him who is styled “The God of this world: the prince of the power of the air, who worketh in the children of disobedience.” The former, with all that appertains to it, will endure when this earth and these heavens are no more; it will flourish, in immortal youth and beauty. The latter, and everything leagued with it, shall be utterly consumed.

We, therefore, further learn from our subject, the importance of having for rulers, men who are decidedly religious. And, here, I am happy to avail myself of an observation of the pious and learned Scott; who says, “Magistracy is an ordinance of God; they therefore, who are employed, even in the most subordinate offices of government, should be chosen persons, able men, of clear heads, and sound judgments; such as fear God, and from a principle of genuine piety, are steadily men of truth, of integrity and fidelity; and have learned to hate covetousness; that they may shake their hands, from holding of bribes, and administer justice impartially. What then,” he enquires, “ought law-givers, and supreme magistrates, to be? Happy, indeed, are the people, that are blessed with such rulers, yea blessed are the people who have the Lord for their God.” 2

In a free government, the example of rulers must necessarily be commanding and influential. If they have not a love for Jerusalem, it can hardly be expected that this affection will very extensively diffuse itself in society. To have the streams salubrious, the fountain must be pure. Thus, then, as it respects the prosperity of a state, the character of those, to whom the management of its public concerns is entrusted, is a thing of vast importance. Their influence, in fixing the standard of public sentiment, upon all political and religious concerns, renders it desirable, that they should have the qualifications, pointed out by unerring wisdom. How desirable, that they should have personal piety! That virtue is necessary, all allow. All the changes of her praises have been repeatedly rung in our ears, ‘till the desired effect is lost.

Men and brethren, bear with me, while I freely plead before you, the cause of vital godliness.—I am always ready, to testify my regard to what is commonly called morality. It is entitled to commendation. It has its reward. But, there is not a single consideration, in favour of morality, as a qualification for office, which is not as much more in favour of undissembled piety, as the motives for action, drawn from eternity, outweigh those of time. Indeed, nothing but piety gives proper security for morality.

The grand morality, is love of thee.”

On the other hand, when men were exalted to places of distinction, who manifested no proper regard to the authority of God, like a deadly plague, the infection ran through the vitals of the body politic, polluting the whole frame. The same is visible, in a degree, in every other nation. How desirable, then, to see men in office, decidedly religious. Those, therefore, entrusted with the right of suffrage, cannot be too careful in exercising it. Be it impressed upon the people, that in exercising that right, it is unsafe to place the concerns of civil society, in the hands of men destitute of religion.

An awful responsibility, also, methinks, rests upon those who accept the trust reposed in them, of “ruling over men.” They are the “Ministers of God,” and how amazing the consequences, both to themselves and to society, if they be not found “Ministers of God, for good!” How amazing the consequences, if found unfaithful to the interests of that cause, for which they were raised up, and brought forward to the places, which they fill! “He that ruleth over men”—with what solemnity and force, does the sacred penman preface the precept! “Now these be the last words of David: David the son of Jesse said: and the man, “who was raised up on high, the anointed of the God of Jacob, and the sweet Psalmist of Israel, said: the Spirit of the Lord spake by me, and the word was in my tongue; the God of Israel said; the rock of Israel spake to me.”—What? What is it thus ushered into special notice? “He that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God.” He must be just. Now justice demands that we render to all their due; not only “to Cesar the things that are Cesar’s, but to God, also, the things that are God’s.” To be just toward God, is to render him his due: it is to render him the honour and glory, which are his due, by listening to his instructions; by walking in his statutes; and by obeying his commandments. It is nothing less, than by a voluntary act of self-dedication, to acknowledge ourselves as his, in the New Covenant. It is to be truly religious. He that ruleth over men, then, to be what he ought to be, must have an attachment to the Redeemer’s kingdom, with “the love, that is strong as death, which many waters cannot quench, neither can the floods drown it.”

It is not morality, which the inspired writers speak of, as the leading qualification in rulers. Laying the axe at the root of the tree, they, everywhere, insist upon Justice: The fear of the Lord; Righteousness; which imply real piety. How, as is required of them, can they be “nursing fathers and nursing mothers” to the church, if they have not a real, sincere friendship to her interests? What, in short, have they to do, with the kingdom of the Redeemer, who belong to another kingdom?

Let us enquire then, are we, as a community, enjoying the prosperity, promised in the text? Are we seeking it, in the way here mentioned? If not, how may we expect to find it? We profess to reverence our forefathers. We speak of them, as wise, religious and happy. But are we walking in their footsteps? How did they seek and find prosperity? They did not forget Jerusalem. The interests of the church lay near their hearts. To enjoy civil and religious liberty unmolested, they sacrificed the endearments of life, in their native country. For these, they encountered innumerable dangers and difficulties, on the land, and on the ocean. Under the divine smiles, they planted the fair vine, which we now behold: under the shadow of which we so comfortably repose ourselves, and the fruits of which we so richly enjoy. But in what they did, let us remember, they kept the ark of God before them. The Bible was their guide. Their trust was in Zion’s God. In all their ways, they acknowledged him. Religion was incorporated, in their civil code. Our historian remarks, “all government was in the church. They early resolved, as a fundamental principle,” he further observes, “that the scriptures hold forth a perfect rule, for the direction and government of all men, in all the duties, which they perform to God and man; in families, in the commonwealth, and in the church; 3

That the work of the ministry might not be left undone, every religious society supported a pastor and a teacher. Magistrates and ministers of the gospel, like Moses and Aaron, and like Zerubbabel and Joshua, went hand in hand together, in building up the interests both of the church and the state. The religious instruction of the rising generation was provided for, and particular attention paid to establish them, in the great truths of the Bible. The happy effect was, that they grew up, favourably impressed with their importance, and were zealous to communicate the same blessings to their offspring. Thus was transmitted to us the fair inheritance, which we now behold. And shall ICHABOD be written upon it, under our guardianship? We felicitate ourselves, upon belonging to a section of the country, that has enjoyed almost unexampled prosperity. But are we secure of its continuance? Stands our mountain so strong, that it cannot be moved? Far otherwise. Have we not, already, reason to tremble at our departure, from the great principles, which regulated our illustrious forefathers? Does not our love for Jerusalem sensibly wax cold? What irreverence for God and his institutions, is there, in many places! What disregard to the Sabbath! What coldness in the things of religion! “How do the ways of Zion mourn, because so few come to her solemn feasts!” In how small a proportion of the families of Connecticut, is there the morning and evening sacrifice! What an inordinate attachment to property is there observable, as if it were the chief good! What a rage for speculations in trade, without regard to means or consequences; and as naturally connected with it, what a spirit of extravagance and dissipation is creeping in! How many silent laws, and how many inefficient magistrates! What an unnecessary multiplication of oaths administered, seemingly, but to be trifled with, and egregiously violated! Yes, Brethren, “Because of swearing the land mourneth.”

Permit me to add, as what I believe to be, at present, one of the darkest traits, in our public character, that in promoting men to places of distinction, and in filling those places, so little regard is shown to the great Head of the church; to his just and reasonable claims upon us; and to the general interests of his kingdom. Swerving from the simplicity and purity of the pilgrims of New-England, are there not those, brought forward to minister for God, in his temples of justice, and in the respective departments of our government, who scarcely believe in a Holy Ghost, who are “aliens from the commonwealth of Israel;” who are “strangers from the covenants of promise,” and who, in accepting the sacred trust committed to them, have regard to little else, than the honours, or the emoluments of office? “Because of these things, cometh the wrath of “God upon the children of disobedience.” Things being thus with us, to expect the continuance of prosperity, that prosperity, which is derived from the approbation and smiles of our God, is preposterous. “And knowing the time, is it not now high time to awake out of sleep?”

In speaking of the happiness of our forefathers, in comparison with our own, and the causes of it, I pretend not that “the former days were better than these,” in all respects. It would be attributing to them something more than human, to say that they had left no ground for improvement, to those who should come after them; and it would be, but justifiable self-respect, to say that this ground has been, in some measure, occupied. At the same time, be we careful to remember, that wherein we depart from “the faith” and practice “once delivered to “the saints,” we make no improvement. If the system pursued by our ancestors was not entirely unexceptionable; if it would not, in all its forms, adapt itself to the present state of society, where I ask, do we find one which, for so great a length of time, has secured to any people so large a portion of happiness?

I am, by no means, an advocate for laws which shall favour any one description of men to the injury of another. I have no desire to see, an empty profession of religion, the test for office. The unnatural and meretricious connexion of church and state, such as we observe in some of the corrupt governments of the east, are the abhorrence of my soul. What is desirable, is to see the minds of the people raised to a proper standard on the subject; aiming at the glory of God, and the honour of his Son; to see those who enjoy the elective franchise, voluntarily promoting men to places of power and trust, who are “not ashamed of the gospel of Christ.” If we have men who, by “a walk of faith,” “patience of hope,” and “labour of love,” give evidence of piety, by all means, other things being equal, let them have the preference.

Shall we here be met with the objections, that such sentiments, put in practice, are calculated to make hypocrites: that real characters of men cannot be known: and the like? But “who art thou, that judgest another man’s servant? Why dost thou judge, and why dost thou set at nought thy brother? To his own master, he standeth or falleth.” To denominate this or that man a hypocrite, is not our province, any further than we are evidently authorized by the rules of our Saviour. When we feel ourselves thus authorized; when we see men, in practice, deviating from their profession, it is easy, at any time, in a free government, like ours, to rank them with the openly immoral and irreligious. And though men cannot be known by their professions; yet our Lord has told us, how they may be known. “By their fruits,” says he, “shall ye know them.” And one of the first fruits of the Spirit of God, dwelling in the heart by faith, is obedience. “If ye love me, keep my commandments.” Where love and obedience are visible in the characters of men, they may be sufficiently known to be trusted.

Although, as has been publicly said, “it is not by profession, only, that men become the disciples of Christ;” although it is to be lamented, that the most detestable characters are sometimes found in the visible family of the Redeemer; although profession is nothing, without the Christian spirit, yet with the Christian spirit, is is a duty of an imperious character. It is what our master Jesus enjoins upon those that love him. No sincere follower of Christ will think lightly of it. Either Christ is our prince and lawgiver, or he is not. If not let us be consistent, and renounce the Christian name. If he be, let us obey him, in all his requirements.

Real religion so raises the disciple above the fear of men, and the shame of the cross; that he is not unwilling to stand forward, and own himself the friend of that Emmanuel, on whose atoning merits, he reposes himself for the salvation of his soul.

Like a good, and faithful, and obedient soldier, he wishes to be seen fighting under the banner of his Captain. “The child of Abraham,” who is “an heir according to promise,” esteems it an honour to “subscribe with his hand to the Lord, and to sirname himself by the name of Israel.” The citizen of the spiritual Jerusalem will be careful to have his name enrolled as a citizen, and will feel his obligations to do duty accordingly. He will not be deterred from what he believes to be his duty, through fear of incurring the odious appellation of hypocrite; nor from popular motives; nor by any selfish consideration.

The objections, therefore, to the “old way” of our fathers, and of the God of our fathers, are groundless. A departure from the “good paths,” in which they have walked, “and found rest to their souls,” I must think an ill-boding omen. So wide a departure as we witness at present, is peculiarly alarming. Unrepented of, what have we to expect, but that a holy God, “jealous for the honour of his name” and “jealous for his Jerusalem,” will leave us as his revolted heritage? What remains, then, but in “this our day to know the things that belong to our peace.”

The subject claims the special attention of the constituted authorities of the state, here present; and of the servants of Christ in the work of the gospel ministry. It has been, till of late, equally the honor and the happiness of this state, that from its first settlement, our principal offices have been filled by men, not backward to acknowledge themselves the friends of the great Redeemer. I mention it with peculiar pleasure, that to the present time, the chair of state has been filled, almost without exception, by men, not merely professors of religion, but men, whose characters have adorned their profession. The natural effect has been that religion and its institutions have ever been held in reverence, by the great body of the people. And where, on the whole, have we known greater prosperity? Our eyes, then, upon this occasion, are turned toward our civil fathers, while with some anxiety we ask, What are our prospects for the future?

You have now assembled, gentlemen, professedly to consult for the prosperity of the community, in which we live. You have seen, whence it is derived. You have seen, that as we have enjoyed, so we may expect prosperity, in proportion to our love for Jerusalem. For an example in this, as in every other thing which is laudable, we are looking to those who have, from their station, a leading influence. Have you then, sirs, that generous affection of heart; are you governed by that love, which is the condition of the blessing? Sustaining the relation which you do, to the community in which you live, you in justice owe to them the prosperity with which you are, in a sense, entrusted on their behalf. You owe to the present, and to future generations, the making of them virtuous and happy. It is with you to say, under the great Head of the church, whether the wise institutions of our venerable ancestors, which have secured to us so many blessings, shall be cherished; whether the gospel shall be preached to dying sinners; whether faithful men shall be supported in devoting themselves to the good work; whether the rising generation shall have the advantages which they need, to qualify them for the learned professions; whether seminaries of learning shall be well endowed, where they may be trained up for extensive usefulness in church and state; whether good and wholesome laws shall be enacted, and steadily enforced, and in these ways God be glorified, and the desolate, waste places of our Jerusalem be built up; or whether, by relaxing yet more and more, we shall become a prey to the destroyer. “If the Lord” THEN “BE God, follow him.” “Follow the Lamb, whithersoever he goeth.” Taking the word of God as your guide, be directed by it implicitly; and let it be seen, that the religion which it inculcates has a decision of character that is unwavering.

However the sentiments advanced in this discourse may be now received, the period cannot be far distant, when the Redeemer’s kingdom will rise to view, in its importance and glory.

“Fulfill’d their tardy and disastrous course,

“Over a sinful world.”

“Behold the measure of the promise fill’d!

“See Salem built the labour of a God?

“Bright as a Sun, the sacred city shines;

“All kingdoms, and all princes of the earth,

“Flock into her; unbounded is her joy,

“And endless her increase.”

Whether we may see this day, in its brightness, or not, we may, if we will, begin to enjoy many of the blessings of it, as individuals, and as a people. From the commanding stations, which they hold, we are looking, with the mingled emotions of hope and fear, to those, who have the management of our public affairs to learn our destiny. “May the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, give unto you” fathers, “the spirit of wisdom, that the eyes of your understanding being enlightened, ye may know what is the hope of his calling; and what the riches of the glory of his inheritance in the saints; and what is the exceeding greatness of his power, toward those who believe: according to the working of his mighty power; which he wrought in Christ Jesus, when he raised him from the dead, and set him at his own right hand in the heavenly places; far above all principality, and power, and might, and dominion, and every name, that is named, not only in this world, but, also, in that which is to come: and hath put all things under his feet, and gave him to be head over all things to the church, which is his body, the fullness of him that filleth all in all.”

The subject, also, claims the special attention of the servants of the Lord, in the work of the gospel ministry. As “watchmen upon the walls of Jerusalem,” brethren, we hold a station, under the great Head of the church, both honourable and useful. As “watchmen,” our duty may be comprised, perhaps, in vigilance and fidelity: vigilance to descry danger, and faithfulness, in time of danger, to give the alarm. “Son of man,” said the Spirit of God, to his servant of old “I have made thee a watchman unto the house of Israel: therefore hear the word, at my mouth, and give them warning from me.” The words are applicable to every minister of Christ. Let us remember, brethren, if we fail to give warning to the wicked, and they die in their iniquity, their blood will God require at our hand. But if they have the warning, and turn not from their wickedness, though they perish, we have delivered our souls. Awakened by all the animating motives, thus presenting themselves, in view of the station, which we hold, and the account we must give, at last, let us think of nothing but perseverance. Let each say with God’s servant of old, “For Zion’s sake will I not hold my peace, and for Jerusalem’s sake I will not rest, until the righteousness thereof go forth as brightness, and the salvation thereof as a lamp that burneth.” Our work is the noblest ever committed to mortals. If there are trials in it, they are the allotments of our Master. Whatever they may be, may we endure them with fortitude, and see to it, that we be found faithful to the interests of the beloved city. It is but a little time, in which we have either to do, or to suffer. Our fathers, where are they? Our brethren, also, where are they? In quick succession, they are passing away from the earth, and following each other to the retributions of eternity.

When last together, upon a similar occasion, the removal of eight ministers was mentioned, as “an unusual and awful mortality.” We have not to mourn the loss, of the same number, 4 who have left us, since the last anniversary election, some of whom were then our fellow-worshippers. Very soon, and we shall all be with them in the world of spirits. Let us so live and labour, that, through grace, our works may follow us to a blessed reward.

And who of this assembly can be named, that does not feel an interest in the truths, now suggested? Who, among us, does not wish prosperity to our common country? Who does not wish for private happiness? Behold them, here made over, and secured by promise, to all who love Jerusalem! How little, has either national or individual prosperity hitherto been sought, by an implicit reliance upon the divine promise! And shall the lively oracles of God, the only guide to happiness, lie by us thus neglected? Is there an object before us, so interesting, of such amazing magnitude—a city of which the blessed Redeemer is the head and law giver; which is the place of his peculiar residence; which he has principally regarded in all the administrations of his providence and grace; to the interests of which, all events are subservient; a city, which he never will forsake; holy in its character; immeasurable in its extent; and in its duration everlasting; all the inhabitants of which, he will make happy for time and eternity, and shall it not attract and ravish all hearts? Are we invited to become partakers together, in its immunities and shall acceptance be, with any, a thing of indifference? No longer, I beseech you, despise your mercies. We live in a day, in which, we peculiarly stand in need of these privileges. In such a day, precious to the believer are the promises of God’s word. Though “Heaven and earth pass,” yet what is here recorded will be remembered. When called to behold on the earth, “distress of nations with perplexity, the sea and the waves roaring, men’s hearts failing them for fear,” how comfortable to know that Zion’s God reigns, and that the Head of the church has mercifully provided for those that love him. “Though the earth be removed, and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea; though the waters thereof roar and be troubled, though the mountains shake with the swelling thereof: There is a river, the streams whereof shall make glad the city of God; the holy place of the tabernacles of the Most High. God is in the midst of her: she shall not be moved. God shall help her, and that right early.”

Whatever calamities there may be in the world, or persecutions in the church, before the end come, we are sure it shall be well with them, that love Jerusalem. They shall not only be preserved, they shall prosper. “All things shall work together, for good to them that love God.” Inconsiderable, and even contemptible, as this city may now appear to the eye of unbelief, yet Christ the Lord is in the midst of her in his glory, and she shall one day “become a praise in the earth.” That day cannot be far distant. We have striking, and constantly increasing evidence, of its near approach, in precious revivals of religion; in a mighty spirit stirred up, in many parts of Christendom, to make the name of Emmanuel known and glorified in the earth; in the removal of those barriers, which have hitherto obstructed the blessed work; and in the general fulfillment of prophecy. “The signs of the times” cannot be mistaken. The period in which we live forms an era, for Christian enterprise. Great projects, and great achievements, are daily coming into notice in the church, such as, from the days of the apostles, have been unknown. He who hath said, “Surely I come quickly,” is evidently on his way. Many “wise men have seen his star in” the east, and, attracted by his love, have “already presented unto him their gifts.” The holy scriptures, that testify of him, are now translated into almost every language. Millions, emerging from horrible darkness, begin to read in their own tongue the wonderful works of God. The princes and potentates of the earth are seen subscribing with their hands to the Lord, and lending their aid for the diffusion of his truth. Indeed, the train seems to be laid for an explosion, which will soon lay in ruins the infidelity and paganism of the old world. 5 The plot thickens, as the scene is drawing to a close. “The Sun of righteousness” is breaking from the cloud, that has long vailed his glory. There is a general movement of the church of God, upon earth. The servants of the Lord begin to “speak comfortably to Jerusalem,” and to cry to her, that her warfare is “well-nigh accomplished.” In a little time, and “the mystery of iniquity” will cease to work; neither the literal nor the mystical Jerusalem shall be longer “trodden down of the Gentiles,” but both Jews and Gentiles shall be “turned to the Lord.” “The vision is yet for an appointed time, but at the end it shall speak and not lie: though it tarry, wait for it, because it will surely come, it will not tarry.

Look, then, at the great events which are passing before you in the light of divine truth. Amidst the commotions and distractions, that agitate the world, keep your eye upon that kingdom, which cannot be moved. Let every revolution be contemplated, as connected with, and subservient to the Messiah’s reign upon earth. Enter into his views. Cast in your lot, with his people. Bind yourselves to the interests of his cause. Be obedient; be humble; be prayerful; be watchful. “Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have a right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates, into the city—the NEW JERUSALEM”—whose foundations are upon the holy and everlasting hills, which cannot be removed but standeth fast forever….AMEN.

Endnotes

1 See the splendid speech of Mr. Wilberforce, found in the parliamentary discussions on Christianity, in India.

2 Scott’s Family Bible—Practical observations on the xviii Chapter of Exodus.

3 Doct. Trumbull’s History of Connecticut. Chapters vi and xiii.

4 Reverend Joshua Belden, Wethersfield. Ozias Eells, Barkhamsted. John Foot, Cheshire. William Graves, Woodstock. Ammi R. Robbins, Norfolk. Lucas Hart, Wolcott. Simon Waterman, Plymouth. Samuel Mills, Chester.

5 As vouchers for the facts here stated, see the letter from Prince Galitzin, President of the Petersburgh Bible Society, to Lord Teignmouth, also that from Josiah Roberts, Esq. London, to Robert Ralston, Esq. of Philadelphia; also a very interesting communication from Dr. Naudi, relative to the spreading of Christianity, in the East, found in most of the religious magazines of the day.