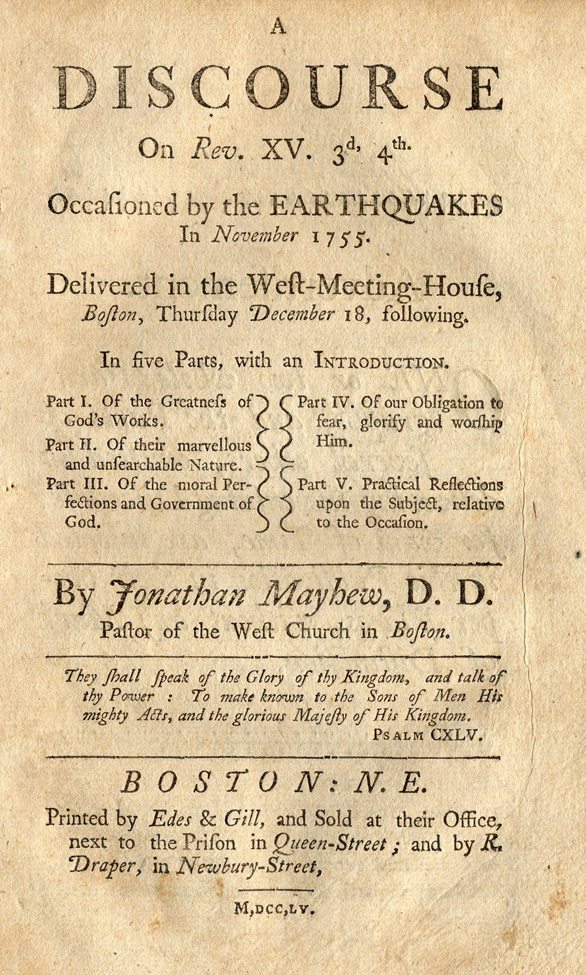

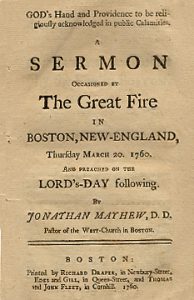

Rev. Jonathan Mayhew (1720-66) was a Massachusetts clergyman. He graduated with honors from Harvard in 1744 and began pastoring the West Church (Boston) in 1747. He preached what he considered to be a rational and practical Christianity based on the Scriptures. Mayhew was a true Puritan and staunchly defended civil liberty; he published many sermons related to the preservations of those liberties, including one immediately following the repeal of the Stamp Act entitled The Snare Broken (1766). Highly thought of by many patriots, including John Adams, who credited Rev. Mayhew with being one of the two most influential individuals in preparing Americans for their fight for independence. In this sermon, Mayhew exhorts his congregation after the Great Fire in Boston (March 20, 1760), providing them with a Biblical perspective of disasters and encouraging them to cultivate a humble and repentant heart before God. Rev. Mayhew’s sermon is an unambiguous example of how early American pastors used the events of their day to impart truth and promote the development of a Christian worldview within their flocks.

Rev. Jonathan Mayhew (1720-66) was a Massachusetts clergyman. He graduated with honors from Harvard in 1744 and began pastoring the West Church (Boston) in 1747. He preached what he considered to be a rational and practical Christianity based on the Scriptures. Mayhew was a true Puritan and staunchly defended civil liberty; he published many sermons related to the preservations of those liberties, including one immediately following the repeal of the Stamp Act entitled The Snare Broken (1766). Highly thought of by many patriots, including John Adams, who credited Rev. Mayhew with being one of the two most influential individuals in preparing Americans for their fight for independence. In this sermon, Mayhew exhorts his congregation after the Great Fire in Boston (March 20, 1760), providing them with a Biblical perspective of disasters and encouraging them to cultivate a humble and repentant heart before God. Rev. Mayhew’s sermon is an unambiguous example of how early American pastors used the events of their day to impart truth and promote the development of a Christian worldview within their flocks.

God’s Hand and Providence to be Religiously Acknowledged

in Public Calamities

A Sermon Occasioned by the Great Fire in Boston, New-England

Thursday March 20, 1760

And preached on the Lord’s Day following.

By Jonathan Mayhew, D.D. Pastor of the West-Church in Boston.

Amos 3:6 Shall there be evil in a city, and the Lord hath not done it?

What devastation have we lately seen made in a few hours! How many houses and other buildings suddenly consumed! How much wealth destroyed! How many unhappy families, rich and poor together, left destitute of any habitation, except those which either private friendship or public charity supplied! What distress in every face; some mourning their own unhappy lot, others tenderly sympathizing with them; and none knowing when or where the wide desolation would terminate!

“Affliction cometh not forth of the dust, neither doth trouble spring out of the ground;” to be sure, not such trouble and affliction as this, a calamity, so great and extensive! This is a visitation of providence, which demands a serious and religious consideration. And it is with a view to lead you into some proper reflections on this melancholy occasion that I have chosen the words read for the subject of my discourse at this time: “Shall there be evil in a city,” faith the prophet, “and the Lord hath not done it?”

It is to be observed, that although these words bear the form of a question, the design of them is strongly to assert, that there is no evil in a city, which the Lord hath not done. Interrogatory forms of expression are often to be thus understood; I mean, as the most peremptory, and animated kind of affirmations. Thus, for example, when it is demanded, “Can a man take fire in his bosom, and his clothes not be burnt?” [Prov. 6:27] everyone understands this, as equivalent to asserting the impossibility hereof in the strongest terms. So, when it is asked, “Can a man be profitable unto God? or is it gain to him, that thou maketh thy ways perfect? Will he reprove thee for fear of thee?” [Job 22:2-4] a peremptory denial of these several things is universally understood by those questions. As if it had been said, verily, a man cannot be profitable unto God! &c. and when, after a representation of the great wickedness and depravity of the Jewish nation, it is immediately subjoined, “Shall I not visit for these things?” saith the Lord: “Shall not my soul be avenged on such a nation as this?” [Jer. 5:29] It is equivalent to a positive denunciation of the divine vengeance against that sinful people: and even more expressive, than if it had been said directly “I will visit for these things: My soul shall be avenged on such a nation as this.” This would have been comparatively a cold, unanimated way of speaking; far less adapted to make an impression on the reader of hearer, than the other.

The manner of expression in the text is obviously the same with that, in the passages quoted above; being more forcible than a simple affirmation would have been, without some note of asseveration preceding. It is as if it had been said, verily, or, surely, there is no evil in a city, and the Lord hath not done it.

However, to prevent a dangerous error here, it must be particularly remembered that by “evil” in the text, is not meant moral evil, or sin; but only natural, viz, pain, affliction and calamity. It cannot be supposed, that the prophet intended to attribute any other evil to God, as the author of it, besides the latter. “Far be it from God, that he should do wickedly; and from the Almighty, that he should pervert judgment!” Nor can the sinful and evil actions of men, properly be attributed to him; or to any over-ruling providence of his, considered as their impulsive cause, or as making them become necessary. “Let no man say [therefore] when he is tempted, I am tempted of God: for God cannot be tempted with evil, neither tempteth he any man. But every man is tempted, when he is drawn away of his own lust, and enticed. Then when lust hath conceived, it bringeth forth sin.” [James 1:13-15] This is the account which the apostle gives of the origin of sin, or moral evil: beyond which, if we pretend to go, in the way of speculation and refinement; we shall probably, at best, only amuser ourselves, and perhaps not be innocent. If God is not properly said, even to “tempt” men to do evil; much less can it be truly said, that he compels them to do it, by any secret energy, or operation, of his. We are doubtless, therefore, to understand the prophet as speaking here, only of natural evil, in contradistinction from moral: so that it will amount to this, that God is the author of all those calamities and sufferings, which at any time befall a city, or community. They are not to be looked on as the effects of chance, or accident; which are but empty names; but as proceeding ultimately from him, the supreme governor of the world; and this, even though they are more immediately and visibly owing to the folly, or vice and wickedness, of men.

To say, in this sense, that there is no evil in a city, which the Lord hath not done, is indeed no more, in effect, than to assert the universal government and providence of God; which, I suppose, we all believe, whatever difficulties may attend our speculations on the subject. If God is the supreme ruler of the world, and exerciseth such a universal government over it, as the scriptures every where suppose and teach, and as nothing but folly or impiety can deny; he must, in some sense, either mediately or immediately, be the author of whatever events come to pass in it. We cannot suppose that there are any evils, or calamities, whether public or private, in the production whereof he has no concern, and which he did not design, with out a partial denial of his dominion and providence. For if any events come to pass, contrary to, or beside his design, or without, and independently of him; his dominion is not an universal dominion, nor does his kingdom rule over all, as the scriptures assert. These events, if any such there are, are plainly exceptions to the universality of his government; being according to the supposition itself, such as were neither done, nor ordered by him. But surely no man but an atheist, or at least one who disbelieves the Holy Scriptures, can think there are really any such events. It is not less a dictate of reason, than it is a doctrine of scripture, that as all things have one common Creator, they are all subject to one common Lord, and under one supreme administration; so that nothing does, or can come to pass, but in conformity to his will, either positive or permissive. The denial of which must terminate, not merely in the denial of a universal superintending providence, but of one or other of God’s attributes; either his omniscience, or his omnipotence, if not of both.

Some public calamities are indeed, as was intimated above, more immediately and visibly the Lord’s doings than others. He is, however, to be acknowledged as the author of them all in general; not excepting those which are brought upon us by the instrumentality of subordinate agents. These are all subject to his dominion and control, and dependent upon him in their various operations; at least so far that they can do us no harm, but by his will and consent.

It may be thought indeed by some, that God is more properly said only to permit, than to be himself the author of those evils, whether public or private, which are brought upon us immediately by inferior agents; or through the wicked devices and practices of men. It is not worthwhile to dispute this point, which is rather a question of words and names, than of things. For it must be observed, that when the word permission is used in this case, it implies in it a will and design, that the things permitted should actually come to pass. When God is said to permit any thing, the meaning hereof is not merely this, that he does not prevent it; for in this sense, we also might be said to permit whatever happens throughout the universe, though it were not in our power to prevent it: the impropriety of which way of speaking, would be obvious to all. When we speak of God’s permitting things, we mean that he does so, knowingly and voluntarily, having at the same time power to prevent them, if he pleased. He might doubtless, if he pleased, prevent them by an immediate interposition; or he might have originally predisposed and ordered things otherwise, and in such a manner, that these particular events should never have come to pass. For which reason, God’s permitting them seems to amount to a positive will, or determination, that they should come to pass; or at least, not differ very materially herefrom.

But not to enter any niceties upon a subject, so intricate in its nature; I shall content myself with observing here, that, in the language of scripture, God is not said to permit, but to do, those things in general, which come to pass under his government, evil as well as good. “I am the Lord, saith he, and there is none else: I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil; I the Lord do all these things.” [Isai. 45:6-7] The scriptures do not speak of God as an unconcerned, or inactive spectator, of any events; but as the author of them; and particularly the author of all the calamities which befall mankind. Only we are to take heed, that we do not so conceive of his over-ruling providence, as to make him the author, or approver, of men’s sinful actions. We are to ascribe to him the most universal dominion and agency, consistent with this necessary caution, or limitation. I say, consistent with this; lest we should be chargeable with blaspheming God, under the show and appearance of doing honor to him. And some there are, who could not perhaps easily acquit themselves of this charge, in respect of the manner in which they express themselves on the subject of God’s providence and decrees.

But to wave everything of a controversial nature, for which this is not, to be sure, a proper occasion; let me here just mention a few of those many public calamities, which God brings upon mankind from age to age. For the ways are numerous, in which he manifests his righteous displeasure against sinful nations; and many the evils which he brings on wicked cities and communities, from one generation to another. He sitteth upon the circuit of the earth; and all nations are before him less than nothing and vanity. All things are subject to his control; and he makes use of them in various ways, to accomplish the designs of his providence. Fire and hail, snow and vapor, and stormy winds, fulfill his pleasure: and the stars in their courses, at his command, fight against his enemies.

God sometimes lays cities desolate by the sword of their enemies. Numberless instances hereof are particularly recorded in sacred story. And this is one of the ways, in which God has often threatened to chastise a wicked and rebellious people. This threatening was executed in a most terrible manner, even on his chosen people Israel, after they had filled up the measure of their iniquities: when Jerusalem was turned into an heap of ruins by the Romans, whom he armed and sent against it.

At other times God manifests his righteous displeasure against wicked cities and countries, by famine. Thus he reminds his people Israel, for their warning, of what he had formerly done against them in this way; and reproves them for their stubbornness under his afflicting hand. “I have given you cleanness of teeth in all your cities, and want of bread “I have witholden the rain from you, when there were yet three months to the harvest: and I caused it to rain on one city, and caused it not to rain on another city. I have smitten you with blasting and mildew. When your gardens and vineyards, and your fig-trees, and olive-trees increased, the palmer-worm devoured them: yet ye have not returned unto me, saith the Lord” [Amos 4].

The pestilence is another of those terrible judgments, by which God sometimes lays cities and countries desolate. The Israelites were often punished for their sins in this way, as they had been before threatned. “I have sent amongst you the pestilence, saith God to them,” after the manner of Egypt “and have made the stink of your camps to come up unto your nostrils: yet have ye not returned unto me.”

Many cities have been destroyed by terrible earthquakes; some entirely; and others so far, as to be lasting monuments of God’s righteous displeasure.

Omitting innumerable other calamities and judgments, by which God makes know his wrath against wicked cities; I shall here only subjoin that of desolating fire. Thus God threatened the king of Babylon of old. “Behold, I am against thee, O thou most proud, saith the Lord God of hosts: for thy day is come, and the time that I will visit the—and I will kindle a fire in his cities, and it shall devour round about him [Jer. 50:31-32].” How many cities have been thus laid in ruins? Some by fire from heaven, or mighty tempests of thunder and lightning, as Sodom and Gomorrah: Of which cities it is said, that they are “set forth for an example, suffering the vengeance of eternal fire; called eternal, because those cities were never rebuilt, but remained to all generations the monuments of God’s wrath. But those fires by which God destroys, or sorely chastises, proud and wicked cities, are not always thus kindled from heaven, as it were immediately by the breath of God. They are more frequently lighted up by other means; either by treacherous intestine enemies with design, or accidentally by other persons. But by whatever means it comes to pass, it is not done but by the will and appointment of God, who over-rules all these events, and has, doubtless, important ends to accomplish by them. 1

Alas! We need not go to distant countries for examples of calamities of this kind. This capital of the province has several times suffered severely by means of fire: particularly about fifty years ago, when a considerable part of the town was reduced to ruins. 2 Since which there have been divers destructive fires in the town, though all of them far less extensive and ruinous. All of them, I mean, excepting that of the last week, which was doubtless by far the most terrible visitation of the kind, that ever it experienced; whether we consider the number of the buildings, the value of the effects consumed, or the multitude of people reduced to want and misery hereby. Some persons of easy, comfortable fortunes, are brought at once into a state of dependence but little better than that of beggary: some, of large and affluent ones, have lost the greater part of what they possessed: whilst others of the poorer sort have lost all; and are, for the present, deprived of all means of getting a subsistence; so that they must either perish, or become a public charge.

Some circumstances preceding and attending this great disaster, are not unworthy of our particular notice. Fires have been more frequent in the town of late, than perhaps they have ever been in times past. It is but three or four months since a considerable fire happened, where by many persons were great sufferers.3 A few weeks after this, another fire broke out; by which, though not so many dwelling houses were consumed, yet perhaps as much damage was sustained. 4

And for three days successively before this last, and most terrible conflagration happened, the town was alarmed by fire. The first of these fires broke out at a very small distance from this place (on Monday, March 17th.); it got to a great head, and threatened to lay waste this part of the town, together with this house of prayer, the house of God, wherein we are now assembled; on which the fire had actually taken hold. But, through the good providence of God, this very dangerous flame was happily extinguished, without the entire consumption of any one dwelling house: and we are again permitted, contrary to the expectation of many, to assemble ourselves for the worship of God, as usual, in this place. So that we have, in this respect, cause to sing of mercy, while, in others, we sing of judgment.

The alarm on the next day, viz. on Tuesday, was very great, and not without sufficient reason: when, by some means, the Laboratory of the royal train of artillery here took fire, and was blown up; when the adjoining buildings took the fire also, which was in imminent danger of being communicated to the king’s stores, in which, it is said, a large quantity of powder, charged shells, &c. were deposited. The apprehension of the fire’s making its way to these stores, and of the fatal consequences that might thence ensue, put the town into a general consternation. It was some time before people thought it prudent, or advisable, to approach the fire, so as to use any methods to extinguish it. But on further information, and a more exact knowledge of the situation and circumstances of things, they applied themselves to the business with great alertness and resolution. And thus this fire was extinguished, when it had done only a small part of the damage that was apprehended from it; though in itself that was not inconsiderable.

The day following (Wednesday the 19th), different parts of the town, at different times, were alarmed with the cry of fire. It did not, however, then get to a considerable head any where, so as to become dangerous: only as there is always some danger from a fire, though but small, in such a town as this; especially in such a dry and windy time as it was then.

By these fires was ushered in, that far greater, and more fatal one, which has left so considerable a part of the town in desolation and ruin (It was discovered between one and two o’clock on Thursday morning, the 20th.). And there is one thing that deserves to be particularly mentioned with reference hereto; as it may tend to lead us into a proper consideration of the providence of God in this affair. When this fire broke out, and for some time before, it was almost calm. And had it continued so, the fire might probably have been extinguished in a short time, before it had done much damage; considering the remarkable resolution and dexterity of many people amongst us on such occasions. But it seems that God, who had spared us before beyond our hopes, was now determined to let loose his wrath upon us; to “rebuke us in his anger, and chasten us in his hot displeasure.” In order to the accomplishing of which design, soon after the fire broke out, he caused his wind to blow; and suddenly raised it to such a height, that all endeavors to put a stop to the raging flames, were ineffectual: though there seems to have been no want, either of any pains or prudence, which could be expected at such a time. The Lord had purposed, and who should disannul it? His hand was stretched out, and who should turn it back [Isai. 14:27]. “When he giveth quietness, who then can make trouble? And when he hideth his face, who then can behold him? Whether it be done against a nation, or against a man only [Job 34:29].” It had been a dry season for some time; unusually so for the time of the year. The houses, and other things were as fuel prepared for the fire to feed on: and the flames were suddenly spread, and propagated to distant places. So that, in the space of a few hours, the fire swept all before it in the direction of the wind; spreading wider and wider from the place where it began, till it reached the water. Nor did it stop even there, without the destruction of the wharfs, with several vessels lying at them, and the imminent danger of many others. 5 We may now, with sufficient propriety, adopt the words of the psalmist, and apply them to our own calamitous circumstances, “Come, behold the works of the Lord, what desolation he hath made in the earth.” So melancholy a scene, occasioned by fire, was, to be sure, never beheld before in America; at least not in the British dominions. And when I add, God grant that the like may never be beheld again, I am sure you will all say, Amen!

In short, this must needs be considered, not only as a very great, but public calamity. It will be many years before this town, long burdened with so great, not to say, disproportionate, a share of the public expenses, will recover itself from the terrible blow. Nor will this metropolis only be affected and prejudiced hereby. The whole province will feel it. For such are the dependencies and connections in civil society, regularly constituted. That one part of a community cannot be much hurt, without detriment to the rest: as in the human body, if one member suffer, all the other members suffer with it. Especially, if the HEAD be sick, or maimed, the whole body will soon feel the effects hereof, and partake of its sufferings And whatever some weak, or envious persons may imagine, the good of the province in general, is very closely connected with the welfare, and flourishing condition of this CAPITAL: so that if it should fall into decay and ruin, the most remote parts of the country would very soon feel the bad effects of it.

At whatever time this disaster had befallen us, it would have been a very great one: but it is particularly so at present, when both the town and country are so much exhausted by public taxes, especially the former: when we have such a load of debt lying upon us; a load still increasing, instead of lessening; and when the season of the year is just coming on, for prosecuting our military designs and operations. This calamity could not well have befallen us at any time, or conjuncture, wherein we should have been less able to bear up under it, and surmount the difficulties occasioned by it. But without any reference to these peculiar circumstances, which enhance the misfortune, the loss or damage, considered in so short a time as that since the calamity befell us. 6

It highly concerns us rightly to improve this visititation of providence, and to conduct ourselves properly under it. This will be, not only our wisdom, but our greatest security against public calamities and disasters for the future, whether of this, or any other kind. We should neither despise the chastening of the Lord, nor faint when we are rebuked of him.

Now, this being truly a public, as well as a great calamity, I shall, in the first place, make some reflections upon it, which concern us all in common. Secondly, I shall direct my discourse particularly to those amongst us, who have been more immediate sufferers therein. An thirdly, to those, whose dwellings and substance have been preserved; and who are not directly involved in this calamity.

First, it becomes us all in general, seriously to regard the hand and providence of God in this evil that has befallen us. This evil, this great evil, has not surely come upon us, but by his appointment, and according to his sovereign pleasure. Various conjectures have been made, and rumors spread abroad, concerning the particular means, by which this raging and destructive fire was first kindled up. Which of them is right, or whether either of them be so or not, I am not able to tell: nor is this very material to my present design. By whatever means this calamitous event has come to pass, we are to look still higher; to the great Author and disposer of all things: for the lord himself hath done it. We ought ultimately to regard him therein, if there be any such thing as a providence superintending human affairs. “Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh in vain: it is vain for us to rise up early, or sit up late, to eat the bread of sorrows.” And the first thing requisite, in order to a due improvement of this visitation, is a fixed, firm persuasion, that God’s hand and counsel determined it to be done; or that it is really a visitation from him. We cannot proceed a step, in the way of religious reflection upon it, unless we lay this down first as a certain principle.

We ought, in the next place, to acknowledge the justice and righteousness of God, in bringing this sore calamity upon us: for the Lord is righteous in all his ways, and holy in all his works. Justice and judgment are the habitation of his throne, not only when the light of his countenance is lifted up, and shines upon us in our prosperity; but also when clouds and darkness are round about him, and we are overwhelmed with adversity. God does not afflict willingly, or grieve the children of men, even when thy have incurred his just displeasure: much less does he wantonly punish the innocent. We may assure ourselves, it is not without just and sufficient provocation, that he has appeared thus against us. It becomes us therefore to be humble and submissive under his chastening hand; under his great frown of his providence. For “wherefore should a living man complain, a man for the punishment of his sins!”

This is a season, wherein it doubtless becomes us all seriously to examine our ways, in order to discover, as far as may be, what are the special grounds and reasons of God’s displeasure against us, and of his contending with us in so terrible a manner. Indeed this general consideration, that we are sinful creatures in common with the rest of mankind, were plainly sufficient to justify God’s dealings with us, even though this calamity had been far greater than it is. However, the holy scriptures give us reason to think, that God seldom, or never, brings very great and public calamities upon a community, unless it is for sins of a very heinous and provoking nature. In which respect, there seems to be a wide and material difference between the conduct of providence towards nations, or communities, and towards particular persons. For with regard to the latter, this certainly will not hold true; the best men being often the greatest sufferers in this world. “All things come alike to all; and there is one event to the righteous and to the wicked,” if we speak with reference to individuals, in this present state: so that “no man knoweth either love or hatred from all that is before him;” either by the prosperity he enjoys, or the adversity which he suffers. Which seems not applicable to communities; at least, not easily reconcilable with the scripture account of God’s conduct towards them, to say nothing of what we are taught by experience.

I pretend not to penetrate so far into the views and designs of providence, as to be able particularly and positively to determine, for what reasons it is that God has thus sorely chastised us. “His judgments are a great deep.” We may, however, conclude in general, that whatever sins are most prevalent amongst us, these are sins which have contributed most to bring this great calamity upon us. In going thus far, there is no presumption. No particular sins, or sinners, are indeed to be excluded, as not contributing to bring calamities upon a people, whenever God sends them. However, I suppose we are to look for the primary, or chief cause of common calamities, not in a comparatively small number of particular person, however impious or profligate; but in the main body of a people. Common judgments must ordinarily be supposed to have some common cause.

And are there not some sins, with which we are very generally chargeable? If any one swears, whoremongers, drunkards, adulterers, thieves or liars, he would doubtless himself deserve no better a character than that of a false accuser, and shameless calumniator. There, are indeed, many such sinners amongst us; but it is to be hoped their number is small, in comparison of those who are guiltless of any of these crimes. But suppose any one should say, that pride was a sin very generally prevalent amongst us, would he merit the character of a false accuser? If another were to assert, that we were generally addicted to luxury, would he be a calumniator? If a third were to tax us with being generally selfish, and greedy of gain, without a due and proportionate regard to the welfare of the public, or of our neighbor; could we truly deny the charge? If a fourth were to accuse us of formality in our religion, of laying too great stress on some things of little or no importance, and comparatively neglecting the weightier matters of the law and gospel, could we justly deny this to be our character? I do not myself bring these general accusations; but it would not be amiss for us seriously to consider, how far they might be just. If there be a real and sufficient foundation for them, we need not be at any loss for such causes of God’s displeasure, as are common to us.

Nor would it be improper for us, on this occasion, to inquire, whether we have been duly thankful to God for the signal mercies and deliverances which he hath vouchsafed to us in times past. He has shown great favor and kindness to us at sundry times, and in divers manners. Though he has often contended with us by fire heretofore; yet how often have very threatening fires been seasonably extinguished; and not permitted to prevail against us. Have we generally been thankful, properly thankful, for these favorable appearances of providence for us, in the times of danger and fear? If not, our ingratitude in this respect, may be supposed one special reason of the late terrible calamity. God’s design may be, to make us more sensible of former mercies, by the greatness of the evil he has now brought upon us.

God has repeatedly visited us with earthquakes, the most alarming in their nature of any of his providential dispensations. However his goodness and compassion have still spared us in these times of our distress, when we had reason to apprehend the most awful and fatal effects of these visitations; particularly of one of them, a few years since: though about the same time, the most amazing desolations were wrought by earthquakes in some other parts of the world. Have we taken proper notice of his dealings with us in this respect? If not, this may be another reason of the great calamity now brought upon us.

Moreover: our enemies, during the late and present war, have been forming dangerous designs against us, even against this metropolis. But God has repeatedly blasted their designs; and has lately given us the most remarkable success against them: so that our once just apprehensions from them, are vanished away; and even turned into triumph over them. Have we been duly thankful for these deliverances and mercies? If not, this may be one cause, why he has destroyed by fire, what he would not permit the enemy to destroy.

Perhaps we have rejoiced with an unchristian, and inhuman joy, in the distresses and calamities lately brought upon our enemies; when great part of their country was ravaged, their villages burnt, their capital city besieged, and partly consumed by fire. If we have rejoiced in their misery with an unrelenting, savage temper of mind, God may have been hereby provoked to bring this great evil upon us; which, in its kind, bears some resemblance to what they have suffered. Or if we have not rejoiced in the misery of our enemies with an unchristian, barbarous joy, perhaps we have triumphed over them with unchristian pride; and been vainly elated with the successes God has given us, instead of being humbly thankful to him therefore. And if this be the case, God doubtless designed to check our pride by this visitation, and make us think more soberly of ourselves.

But if there are no particular sins, with which we are chargeable in common; yet are we not all in general chargeable with some? Some of us with one vice, or misdemeanor, and some with another? If so, this is a sufficient ground for our being thus chastised by a common calamity. And we were doubtless ripe for some signal punishment from the hand of providence, when this great evil came upon us. Many atrocious sins, and flagrant abominations, are found in the midst of us. To what an amazing pitch of wickedness and impudence, some persons amongst us were arrived, is evident even from some transactions at the time of the late terrible fire. For, instead of being affected with so melancholy a providence, and charitably assisting people in saving their effects, some there were, so hardened and shameless, as to take the opportunity of the general confusion, to steal and rife their neighbor’s goods! One would hardly have thought it possible for people to be so wicked, impious and abandoned. I hope, indeed, there were not many such; and that there were not born and educated amongst us, though I am not certain. But wherever they were born and bred, they are certainly a disgrace, not only to their own country, gut to the world itself, and to human nature.

It does not become us, even the best of us, on such an occasion as this, to justify or excuse ourselves; or to attribute this public calamity wholly to the sins of others. Probably none of us can entirely acquit ourselves of having contributed to it, by our own particular miscarriages. And it highly concerns us all, seriously to reflect upon the righteous hand of God.

We may all learn some very useful and important lessons from this visitation, if we duly attend to it. We are hereby more particularly reminded of the vanity of worldly riches, and the folly of depending on, or placing our chief happiness in them. How suddenly do they take to themselves wings, and fly away, as an eagle towards heaven, leaving the possessors of them destitute, not only of superfluous wealth, but even of those things which are needful for the body! This is one of those dispensations of providence, which give a particular force and energy to those words of the apostle. “Charge them that are rich, that they trust not in uncertain riches, but in the living God, who giveth us richly all things to enjoy”: and also to that more general admonition of our Savior himself. “Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust do corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal; but lay up for yourselves treasure in heaven,” &c.

To finish these general reflections; we are all in common admonished by this visitation of providence, to consider and amend our ways. Doubtless the end of our being thus visited and chastised, is our reformation. Whatever serious reflections we may at present make upon this calamitous event; yet the great design of it will not be answered upon us, if we continue unreformed. This is often the case. Pharaoh and his people were in some measure humbled, at the time when the plagues were upon them. But they soon forgot the judgments of heaven; and became more hardened afterwards. This was sometimes the case also with the people of Israel. “Thou hast stricken them,” says the prophet, “but they have not grieved; thou hast consumed them, but they have refused to receive correction. They have made their faces harder than a rock, they have refused to return.” If we are not reclaimed from our sins and vices by this calamity, we have reason to apprehend greater and heavier ones. God’s anger will not be turned away; but his hand will still be stretched out against us. O let us not, by our impenitence and hardness of heart under this correction, provoke God to smite us with greater severity; lest, perhaps, we perish under his hand, while there is none to deliver! But, on the other hand, if we duly lay to heart this sore chastisement, and return to God, he will doubtless return unto the “Lord: for he hath torn, and he will heal us; he hath smitten, and he will bind us up.” Though he hath visited our transgressions with a rod, and our iniquities with stripes; yet his loving kindness will he not utterly take from us; nor suffer his faithfulness to fail.

But I was in next place, secondly, to direct my discourse particularly to those amongst us, who have been the more immediate sufferers in this common calamity. My brethren, I trust we all in general heartily sympathize with you, and bear a part in your affliction. But if it concerns us all in common, seriously to consider the hand of God in this visitation, allow me to remind you, that it more especially concerns you to do so, on whom this great calamity, by his appointment, has more immediately fallen. To us, this providence more than whispers; to you it speaks still louder, even in thunder. I would, however, be very far from insinuation, that the unhappy persons who are the immediate subjects of this calamity, are in general more guilty in the sight of God than other. This would be at once uncharitable in itself, and a plain violation of a rule, or maxim, which our Savior laid down on an occasion not altogether unlike to the present. But still you must acknowledge that although the call and admonition of providence in this visitation, be to all of us in common; yet to you it is more direct and immediate, as well as louder. You are especially admonished to examine your ways, in this day of visitation and trial. And if you should disregard this providence, you would doubtless be more inexcusable than others.

It becomes you to bear your losses, however great, with patience, and humble resignation to the will of God: for he it is, you will remember, that has brought this evil upon you. Nor has he taken any thing from you, which he did not first give to you. All that is in the heaven and in the earth, is his: both riches and honor are of him [I Chron. 29:11-12]. And you are sensible that all his worldly and temporal gifts, are gifts only during his good pleasure: not absolute, perpetual grants; but such as he has an indisputable right to recall, at whatever time, and in whatever manner, he sees fit. You have therefore no reasonable ground of complaint; but ought meekly to acquiesce in what he hath done. It were not amiss for you on this occasion, to reflect on the much greater losses and sufferings of Job; and on the manner in which he conducted himself under them. He “fell down upon the ground, and worshipped, and said, naked came I out of my mothers womb; and naked shall I return thither: the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord. In all which Job sinned not, nor charged God foolishly” [Job 1].

God has doubtless wise and holy, and even gracious ends, to answer by visiting you in this manner. The visitation is particularly calculated to wean your affections from this evil world; and excite you to seek, with greater diligence, the true spiritual riches. Perhaps your hearts have been heretofore too much set upon the world; and those riches which will not “profit in the day of wrath.” If this be the case, God hath shown you your error by this visitation of his providence; and calls upon you hereby, for the future to set your affections only on those things that are above, where Jesus Christ sitteth at his right hand. It will be happy for you, if you make so reasonable and wise improvement of your worldly losses; they will then be the greatest gain to you in the end. Any accession to, or increase of your virtues, is of far more benefit and importance to you, than thousands of silver or of gold would be, or all worldly riches. These are corruptible and transitory: but that is a treasure that fadeth not away, incorruptible and eternal. And a good man, in the language of the apostle, equally bold and beautiful, “having nothing, possesseth all things!”

Those whose habitations and wealth have been consumed by this desolating fire, have still great cause of thankfulness, that their lives have been preserved. “The life is more than meat, and the body than raiment.” Considering the time when this fire broke out, being the dead of the night, when people were in their beds, and some of them on beds of sickness; considering the violence of the wind, and the rapidity with which the flames spread, and caught from place to place; the wide extent of them, and the general confusion and consternation which they occasioned; considering these things, I say, it would not have been strange, if many persons had perished together with their substance, and mixed their own ashes with that of their dwellings. But no life was lost. In this respect, God remembered mercy in the midst of judgment; which demands our grateful acknowledgements; and particularly the thanks of those, who were in danger of being consumed in their dwellings, as many of the unhappy sufferers were.

Besides: I take it for granted, that few. Or none of you, my brethren and usual hearers, have lost all your worldly substance, as some others are said to have done. Let me therefore exhort you to be thankful to God for what he has left you still possessed of; especially if that be sufficient for you to subsist comfortably upon, in the way of honest industry. Though you ought not to despise the chastening of the Lord in the losses you have sustained; yet it becomes you to acknowledge his goodness in what is left you. It is not a great deal that is necessary to the ends of life: virtue, and moderate desires, are satisfied with little; and having food and raiment, you ought to be therewith content. We brought nothing into this world, and it is certain we can carry nothing out of it, how much forever we possess: though if we could, it would be of no advantage to us. In heaven we should not need, but despise and neglect it; and in hell it would not alleviate our torments.

But if any of you should have lost all your worldly substance by this calamity, you ought not, however, to despond under this trial, or to saint, being thus rebuked of the Lord; but still to place your hope and trust in him, who heareth the young ravens when they cry. “O fear the Lord, ye his saints; for there is no want to them that fear him. The young lions do lack, and suffer hunger; but they that seek the Lord shall not want any good thing [Psalm 34:9-10].” I reminded you above of the sufferings and patience of Job; let me now remind you of the “end of the Lord” with respect to him; “that the Lord is very pitiful, and of tender mercy [James 5:11].” That good man saw at length a happy issue of his troubles. For “the Lord blessed the latter end of Job more than the beginning [Job 42:12].” You may from hence take some encouragement: God is able to make all things abound to you. And it is a circumstance not unworthy to remind you of, for your consolation, that you live in a country, at least in a town, wherein there is a general disposition in the people to afford necessary relief to the poor and afflicted: so that you have no reason to be under any anxiety of mind respecting a livelihood; especially if you enjoy bodily health and strength, with ability to exercise some lawful calling. But whatever be your condition in this world, godliness with contentment will be, not only your duty, but your grateful gain. You should endeavor to be prepared for whatever circumstances God shall order for you; and to this end, beseech him to give you the temper of the holy apostle, who said, “I have learned in whatsoever state I am, therewith to be content: I know both how to be abased, and I know how to abound; every where, and in all things I am instructed, both to be full and to be hungry, both to abound and to suffer need [Phil. 4:11-12].” Even the Son of man had not where to lay his head, though the foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests. And if the same mind be in you, which was in Christ Jesus, you will bear the extremist poverty without repining. Lest therefore you should be weary or faint in your minds, consider him, how “though he were rich, yet for your sake became poor:” learn of him to be truly “meek and lowly in heart; and whatever be your outward condition, you will then find rest unto your souls;” such rest as the greatest worldly prosperity cannot give!

Thirdly: let me now turn my discourse to those, whose habitations and substance have been preserved in this time of desolation; especially to those, who have been in imminent danger of being shares with others therein. As this calamity is from God, so it is he who has directed it where to fall, and prescribed its bounds and limits. You should therefore be sensible, that he has been your preserver; and made this distinction between you and others If others ought to acknowledge his providence in the calamity which has befallen them, certainly it is not less incumbent on us to acknowledge it in our own preservation. Had God, who commandeth the wind when and where to blow, given a different direction to it, our habitations might have been consumed, while those of the present unhappy sufferers were preserved. I mention this circumstance particularly, because it is familiar and obvious; plainly showing, that it is God, and not man, who has made this difference; and important truth, which might be evinced by other considerations also, were there time and occasion for it.

Nor ought we to attribute our preservation to any supposed merit, or superior goodness in ourselves; or the sufferings of our neighbors, to any greater guilt or demerit in them. Our Savior seems to have designed a general caution against such imaginations, in a passage which was alluded to above. When certain persons told him of some Galileans, whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices, expecting, probably, that he would have attributed this to the great wickedness of those Galileans in comparison with other, his reply was – “Suppose ye that these Galileans were sinners above all the Galileans, because they suffered such things? I tell you, nay – or those eighteen, on whom the tower of Siloam fell, and slew them; think ye that they were sinners above all men that dwelt at Jerusalem? I tell you, nay: but except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish.” Our Savior’s meaning here is not, that those Galileans, and those Jews, were not sinners; or that they did not justly suffer such things on account of their sins. Neither of these things can be supposed. But the obvious design of this remarkable passage is, to teach us that God, in his providential government of the world, does not always single out the greatest sinner, to make them the greatest sufferers in the sight of men; and, consequently, that we ought not to conclude ourselves more righteous than others, merely because we at present escape those judgments which befall others. God will finally give to every man according to his deeds, in weight and measure, and exact proportion. But at present he acts as a sovereign; I mean, in the outward dispensations of his providence towards particular person; agreeably to the observations of Solomon, mentioned in the former part of this discourse, that “all things come alike to all; that there is one event to the righteous and the wicked; and that no man knoweth either love or hatred from all that is before him.” A greater than Solomon has confirmed these remarks on the conduct of divine providence. We should therefore take heed, that we do not attribute to our own superior piety or virtue, what we ought to ascribe solely to the sovereign pleasure of God, and his distinguishing favor towards us. For to apply our Savior’s language and reasoning above, to the melancholy occasion before us: suppose ye that those who have lately suffered such things, were sinners above all that dwell in Boston? I tell you, nay! At least, we have no reason to think them so, on this account. Many who have escaped this disaster, and perhaps we ourselves, are as great, or greater sinners; and except we repent, some “worse thing may come unto us.”

What shall we render unto the Lord for his distinguishing goodness to us in this respect? It becomes us to render praise to him; for “whose offereth praise, saith the Lord, glorifieth me.” We should also show our gratitude to God, by devoting ourselves, and all we have, to his honor and service. His goodness and forbearance lead us to repentance, while his righteous severity is exercised towards others for the same general end. Us he draweth with the cords of love, while he scourgeth others, not more guilty, with the rod of affliction. And shall we despise his goodness, forbearance and long-suffering! If there be any peculiar audaciousness, or presumption, in despising the chastening of the Lord; there is certainly a peculiar baseness and disingenuity, in despising his goodness. We and our substance, have been as it were plucked out of that fire, by which other have suffered so much. Let us therefore take heed, lest we incur that heavy censure, Amos Chap. IV. “I have overthrown some of you as God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrha; and Ye were as a fire-brand plucked out of the burning yet have ye not returned unto me, saith the Lord!”

Will it not particularly become us to show our gratitude to God for his distinguishing mercy to us, by cheerfully imparting of our substance for the relief of our indigent brethren? The government has already done something for their present relief. But there being so many of these unhappy sufferers, they will doubtless stand in need of farther succor and assistance, before they are in any method of supporting themselves. And God forbid. That any of us who have escaped this calamity, should be backward to distribute, or unwilling to communicate, as there may be occasion, and we have ability! One reason, we may well suppose, why God has spared our substance, is, that we might be in a capacity to relieve and assist those, whom his holy providence has rendered objects of our charity. It is partly for their sakes, not wholly for our own, that our substance has been preserved. Nor can I indeed doubt, but that the people of the town will be generally disposed to liberality on this occasion; especially when I reflect, how largely and cheerfully they contributed a few months since, on a similar occasion. 7

But it is time to draw a conclusion of this discourse. When God’s judgments are abroad in the earth, it is then more especially incumbent upon the inhabitants thereof to learn righteousness. If we do not regard the past, or present, there may probably be other, and heavier ones, in store for us. At least it is certain, that the wicked shall not finally escape the righteous judgment of God. “For behold the day cometh that shall burn as a oven, and all the proud, yea, and all that do wickedly, shall be as stubble; and the day that cometh shall burn them up, saith the Lord of Hosts, that it shall leave them neither root nor branch. [Mal.4:1]” Such a fire as we have lately seen, especially in the night, diffuses general terror and distress. What then will be the consternation, how great the amazement, of a guilty world, when the Son of man shall be revealed from heaven in flaming fire, taking vengeance on them that know not God, and that obey not his gospel! The old world perished by water: but the heavens and the earth that now are, are reserved unto fire, against the day of judgment, and perdition of ungodly men. And even these lesser fires and conflagrations, which strike us with so much awe, may naturally remind us of that general, and far more awful one, which the prophets and apostles have foretold: when the earth itself, with the works that are therein, shall be burnt up, and the elements shall melt with fervent heat. “Seeing then that all these things shall be dissolved, what manner of person ought we to be, in all holy conversation and godliness? Looking for, and hasting unto, the coming of the day of God!” To the wicked this will be a day of unutterable woe; but to them that fear his name, and serve him, a day of triumph and exultation. Happy are they who diligently prepare for it. But, alas! there are many, who will not be persuaded, that there is such a day approaching; “scoffers, walking after their own lusts, and saying, where is the promise of his coming? For since the fathers fell asleep, all things continue as they were from the beginning.” And many of those who profess to believe it, do not practically regard it, minding only earthly things: and such as these will accordingly be overwhelmed with a sudden and remediless destruction. For “As it was in the days of Noah, so shall it be also in the days of the son of man. They did eat, they drank, they married wives, they were given in marriage, untill the day that Noah entered into the ark: and the flood came, and [38] destroyed them all. Likewise also as it was in the days of Lot; they did eat, they drank, they bought, they sold, they planted, they builded: but they same day that Lot went out of Sodom, it rained fire and brimstone from heaven; and destroyed them all: even thus shall it be in the day when the Son of man is revealed! [Luke 17:26-30]”

The End.

NOTES