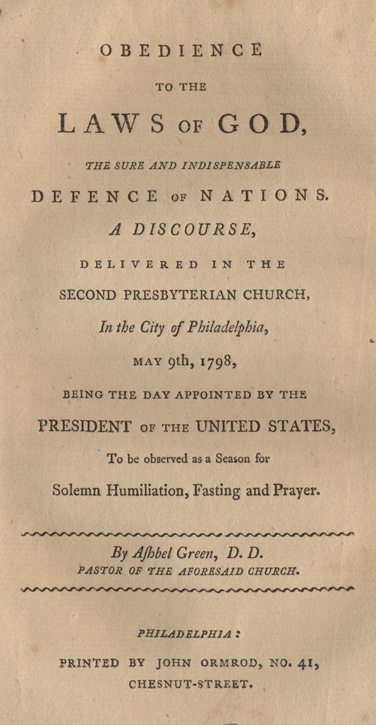

Ashbel Green (1762-1848) served as a sergeant in the Revolutionary War from 1778 to 1782. After the war he enrolled in Princeton and graduated in 1784. He was licensed to preach in 1786 and installed as the pastor of the 2nd Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia in 1787. In 1792 he was appointed chaplain to congress. Green became the president of Princeton from 1812 until 1822.

Laws of God,

Delivered in the

Second Presbyterian Church,

In the City of Philadelphia, May 9th, 1798.

By Ashbel Green, D.D.

The following discourse, when delivered from the pulpit, was divided, so as to form two addresses; one of which was made in the morning, and the other in the afternoon. Even with this division, it was found necessary to omit several paragraphs, which seemed proper to be introduced, on reviewing it for the press.

Discourse

I Chron: xv. Ch. 2nd. Verse.

—“Hear ye me, Asa, and all Judah and Benjamin, the Lord is with you while ye be with him. And if ye seek him he will be found of you; but if ye forsake him, he will forsake you.”

The proclamation of the Chief Magistrate of the nation which calls us to the service of this day, states, as the special reason of the call, that it is “a season of difficulty and danger” to our common country. That such is the fact, no one in this assembly will pretend to deny. Not an individual who seriously contemplates our national situation, can forbear to confess, that, on every hand, dangers threaten and difficulties beset us. To anyone who should suggest a sure, practicable and easy plan, for maintaining our honor and preserving our civil and religious rights, it would be acknowledged that every ear should listen with attention, and every heart offer a tribute of thanks. My brethren,—a prophet of Jehovah offers you this very plan in the words of my text. The sacred herald proclaims it to you this hour, as really as he did to the favorite people of heaven in ancient times:—As really as he then said—“Hear ye me Asa, and all Judah and Benjamin,” he now says—“Hear ye me, rulers and people of America!—the Lord is with you while ye be with him—If ye seek him he will be found of you.” This, I affirm, is a sure plan for national defense and prosperity: “For if God be for us who can stand against us!”—What wisdom can contend with omniscience? What power can resist omnipotence? “Associate yourselves O ye people, and ye shall be broken in pieces; and give ear all ye of far countries; gird yourselves and ye shall be broken in pieces: gird yourselves and ye shall be broken in pieces. Take counsel together and it shall come to naught; speak the word and it shall not stand; for God is with us.” Nay, more—the plan of the prophet is not only effectual, but it is the only one that can be effectual. The same veracity which gives the comfortable assurance, on one condition, connects with it an awful alternative on another. “If ye forsake God he will forsake you.”—If, forgetful of your dependence on Jehovah, ye violate his laws and condemn his ordinances, his protection and favor will be taken from you, and then cometh confusion and every evil work. Left to yourselves, you will speedily become the prey of your enemies or work out your own destruction. Vain will be all your exertions. “For there is no wisdom, nor understanding, nor counsel against the Lord.”—His hand will find you out, and with just displeasure will seal your final ruin.

Thus have I given what I take to be the true import of the text, and with that direct application to our own circumstances, which I hope may engage our serious attention to it—That the statement you have heard is just, I shall endeavor to prove, in establishing the following proposition, in which it is comprised,—namely, —The nation that adheres to the laws of God shall be protected and prospered by him, but the nation that forsakes and disregards those laws he will destroy.

In discussing this doctrine, it will not be necessary to give a separate treatment to its contrasted parts. More advantage may be derived from considering, in connection, the nature, both of that obedience and disobedience which is contemplated, and of that benefit or injury, which severally results from them.

First, the, let us consider what is that adherence or obedience to the divine laws, which will insure to a nation the protection and blessing of heaven; and from which we may also, see, that deficiency or disobedience, on which the threatening is pronounced.

The obedience contemplated is described in the text by being or remaining with God, and by seeking him. In this, I think, all must allow there is implied, that a nation pay some general and sincere regard to those laws and obligations of duty, which the light it possesses, manifests to be of divine institution and sanctioned by the divine authority. Reason and scripture evince, in the clearest manner, the justice of this demand. If reason remonstrates against the iniquity of requiring men to obey laws, of which they have had no knowledge, and to walk by light which they have never seen, she equally enforces their obligation to obey every equitable law with which they are acquainted, and to act agreeably to the best information which they have received. In other words, it is one of the plainest dictates of reason, that men should be answerable for their improvement of the advantages they possess, and for nothing more. Accordingly we find that inspiration, which is reason purified from all error, expresses this principle, thus,—–“That servant which knew his Lord’s will, and prepared not himself, neither did according to his will, shall be beaten with many stripes. But he that knew not, and did commit things worthy of stripes, shall be beaten with few stripes. For unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall much be required; and to whom men have committed much, of him they will ask the more.—Therefore, to him that knoweth to do good, and doeth not, to him it is sin.” This rule must be as applicable to nations as to individuals, for of individuals, nations are composed. Let us apply it, then, to the case before us, and see what will be its result, as it relates to Heathens, Jews, and Christians.

Of the Heathen nations the account given by unerring truth, is as follows—“The wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who hold the truth in unrighteousness. Because that which may be known of God is manifest in them, for God hath showed it unto them. For the invisible things of him, from the creation of the world, are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even his eternal power and Godhead; so that they are without excuse.” And again—“When the Gentiles which have not the law, do by nature the things contained in the law, these, having not the law, are a law unto themselves; which show the work of the law written upon their hearts, their conscience, also, bearing witness, and their thoughts, the mean while, accusing or else excusing one another.” From this it appears that the Heathen nations, though destitute of a revelation, had still so many advantages from the light of nature itself, as to render them inexcusable when they violated the great principles of duty either to God or man. To acknowledge the existence, the providence, and many of the perfections of the Supreme Being, to be sensible of their dependence on him in all their concerns, to realize their indebtedness to him for all their guilt and unworthiness, to implore his favor, and to deprecate his displeasure, was a service which, even in their circumstances, might reasonably be demanded of them. The law, also, which was written on their hearts, or discoverable from natural reason, was sufficient to teach them the duties of justice, truth, humanity and benevolence, toward each other. How little of all this was actually found among those nations, is well known to those who are acquainted with the melancholy history of their moral and religious state. But the rule of their duty was such as has been stated, and as far as they manifested any color or degree of conformity to it in their external conduct or national character, the divine mercy and condescension, as well shall see hereafter, treated them as coming within the condition on which protection and prosperity in this world, are promised and bestowed. But when all regard to the moral and religious principles that have been recited, became extinct among them as a people, then they subjected themselves to the threatened penalty.

To the Hebrew nation, the knowledge of the true God was clearly revealed. The unity and spirituality of his offense; the infirmity, eternity, purity and holiness of his nature and attributes; his creation, and his absolute and immediate government of the world; his moral laws; and his purposes of grace and mercy toward penitent sinners; were manifested to this people, in the fullest, most unequivocal, and most impressive manner. Their national polity itself was a theocracy, or mode of government in which the Deity sustained to them, not only the common relation of supreme governor of the world, but also that of a civil chief. He dictated all their political institutions; he presided over the administration of them; and with a view to secure them against falling into that ignorance of himself, that idolatry, superstition and immorality, which, at this time, characterized and degraded all the other nations of the world, as well as to be a shadow of good things to come, he instituted a complicated ritual of ceremonial observances and temporary regulations. These advantages laid the Jews under higher and more numerous obligations to moral and religious purity than any other nation then existing. It was, also, manifestly incumbent on them to regard, with sacred exactness, even those ceremonial rites, which had been enjoined by divine authority with the most wise and benevolent intention. Here, then, we have their rule of duty. While they walked agreeably to these advantages and institutions they might be said to abide with God and to seek him. When they departed from these they were said to forsake him. The observance of these things is precisely the ground of the promise in the text,—the promise of the divine presence and protection, with all its happy consequences. On the contrary, their departure from the rule of duty which has been specified, subjected them to the threatened dereliction and displeasure of God, with all its ruinous effects.

Under the Christian dispensation we have still a new accession of light. In addition to the knowledge of the Deity, and of his laws and designs, which the ancient Hebrews possessed, we have a bright display of the very method in which his purposes of mercy toward our fallen race are fully carried into effect. “He who spake unto us by the prophets hath, in these last days, spoken unto us by his son, whom he hath appointed heir of all things, by whom also he made the world”—who is “Immanuel, God with us.” By him “we have received the atonement.” We are distinctly informed, that “he was made sin for us, who knew no sin, that we might be made the righteousness of God in him.” We are assured that by faith in him “we are justified without the deeds of the law.” To us it has been declared by divine authority, that “all men should honor the Son, even as they honor the Father,” and that “he that honoreth not the Son, honoreth not the Father who hath sent him.” We have received information, more distinct than was given under the Mosaic economy, of the million and work of the blessed Spirit of God, emphatically styled “the Comforter”—We are told that man, “dead by nature in trespasses and sins,” can be saved only by “the washing of regeneration and the renewing of the Holy Ghost.” The spirituality and extent of the divine law is more completely unfolded to us than to the Jews, and the doctrine more powerfully inculcated that “without holiness no man shall see the Lord.” The obligations to justice, benevolence, charity, meekness, kindness, forgiveness, and every good work, are most powerfully enforced. “Life and immortality is brought to light by the gospel.” A future judgment is plainly revealed, and the states of eternal happiness and misery, which await the righteous and the wicked, are clearly and strikingly set before us.

It must immediately be perceived that this system of information originates many peculiar obligations and duties, which could not be binding or incumbent on those who were destitute of it:—And therefore the nation which is blest with the knowledge of this system, will then, and then only, come up to the condition on which the promise of protection and prosperity is founded in the text, when it pays some suitable regard to the leading principles which it contains. When those principles are generally and notoriously violated, the solemn declaration that God will forsake such a people, immediately becomes applicable.

Let me request that the statement which has now been of the rule of moral and religious duty to communities, in dissimilar circumstances or under different dispensations, may be carefully kept in mind through the remainder of the discourse, that repetition may be spared without producing mistake. Let it be understood and remembered that in speaking of the virtues or vices of nations as the cause of prosperity or adversity, I always consider the distributive justice of God as deciding the destiny of each by its relative advantages,—its relative knowledge of moral and religious truth, and that practice which is consonant or contrary to it.

This statement, however, has not been made, merely to furnish a basis of illustration to the following part of the subject; but also to show how totally void of force is a favorite remark in infidel writers on this topic. With much apparent triumph, they reproach the advocates of Christianity for representing national prosperity as any way connected with a regard to the Christian religion, and the adduce the prosperous condition of some pagan countries, both in ancient and modern times, as proof positive of the justice of the reproach. But we may here see that the fact alleged (allowing it to be a fact) is, in truth, no proof at all. Those nations never were under obligation to conform to the same standard which we are bound to regard. It will presently be seen that when they actually and generally departed from what was their rule of duty they were uniformly destroyed. But to say that a Christian nation, may with impunity become Pagan, while a Pagan nation (it is allowed on all hands) could not with justice be required to regard Christianity, is an assertion which does no honor to the sagacity or candor of its authors. It is to say that they who possess the most advantages may safely act like those who have enjoyed the least. The Heathen posses one degree of information, we another. They are dealt with by their own measure, we by ours. This is strictly the principle of justice; and the objection in question is annihilated by the obvious remark.

Here, however, it may be observed, without cavil, that no nation ever fully conforms to the rule which has been specified as marking the line of duty; and it may be asked—what is that measure of conformity, which will secure the benefits of the promise? To answer this enquiry with precision and as it relates to particular cases God alone is competent. “He giveth not account of any of his matters.” In some instances his mercy may forbear with nations after considerable defection, and in others his justice may take speedy vengeance. While the guilty are never punished till they deserve it, equity is not violated in waiting longer for the reformation of some than of others. This exercise of sovereignty, this limited variety in his dispensation, is seen in all the administrations of the Deity. The most wise and important purposes answered by it. Presumptuous is restrained, on the one hand, and despondence or despair is prevented, on the other. The entire freedom of human action is, also, preserved by this order. The mind of man is left to that full exercise of judgment and choice, and that natural operation of desire and prosperity, which render him most completely accountable for his actions. From this cause it will come to pass that the method in which nations are treated will appear somewhat irregular. The virtuous, in some cases, will appear to suffer, and the vicious to be triumphant. A semblance of contradiction will hence arise to the doctrine I inculcate. Yet, as will be shown more fully in its place, it is only the semblance, and not the substance of opposition, that will thus be produced. A criterion of judging sufficiently exact, and most highly important, will still be left us. It will still remain a perspicuous and interesting truth, that when a nation is characteristically pious it will be ultimately protected, and that when it becomes characteristically impious it will be fast hastening to destruction; and that in proportion as it approaches to the one or the other of these extremes it has reason to hope or to fear. To explain my meaning, here, with reference to a Christian nation, I would say, that—When the rulers of a Christian country recommend Christianity by their practice and example: when they discover a reverence for it by faithfully enacting and executing laws for the suppression of vice and immortality: When, without infringing on the rights of conscience, they encourage true piety, by countenancing those who profess, practice and teach it: When, on suitable occasions, and in public acts, the Being and Providence of God, and our accountableness to him, are recognized, and the honor which is due to his Son is rendered: When the moral laws of God, relative to man, as well as to himself, are truly regarded, by those whose station gives influence and fashion to their conduct, and renders it in a sort the representation and expression of national sentiment on the subject of morals: And when, in addition to this, the great principles of piety and morality already recited, are so generally and effectually taught and inculcated on the people at large, as really to influence the public mind, and in some good degree to form the popular opinions and habits:—this I would say was a performance of duty,—this would secure to a Christian nation the benefits of the divine promise. But when, among those who preside over the people, the very being, attributes, and providence of God are denied, or when there is a studied omission of every idea that refers to his government, or to our dependence on him: When, through a hatred of Christianity, it is disavowed, despised, laughed at, and in the most contemptuous manner trampled underfoot; or when through pusillanimity or impious policy, a country conceals its attachment to the religion of Jesus; or when the profession of attachment is only a thin veil of hypocrisy: When the leading men of a nation flagrantly and shamelessly violate every moral law: And when the people at large love to have it so, and are rapidly assimilating to the same corrupt standard; then they subject themselves to the divine denunciation, and are treading on the brink of destruction.

Let us now

II. Attend to the proof of this assertion; or to the proof, rather, of the general position—That righteous nations will be protected and prospered, and that impious nations will be destroyed.

The remark scarcely needs to be made, that I am not here to maintain that God will either protect a righteous, or destroy a wicked nation, by any miraculous exertion of his power, or in any other way than by the use of those means, and the operation of those causes, which under the guidance of his providence are naturally calculated, and best adapted to produce such an effect. No, my brethren—When nations, in the early stages of the world, could not be fully instructed by experience in the principles of the divine government, because time for this experience had not yet been afforded; and that the most impressive proofs of the very truth which the text asserts might be furnished to all future time, God did, indeed, work miracles of salvation for the people who feared and served him, and miracles of destruction on those who departed from his laws. But as these examples are now furnished, and held up to our view as sure indications of what we are to expect from the same source of justice from which they flowed, and as abundant experience has shown what is the settled order of the divine dispensation, miracle is not to be expected, because it is not necessary. There have been some instances, indeed, in every age, both of the deliverance and destruction of nations, in which the divine interference has appeared but little short of miraculous. Such events, however, are not to be reckoned on, though they may sometimes occur. In general, if God intend to preserve a nation, he will either dispose others to be at peace with it, or he will stir up its inhabitants to a rational, vigorous and united exertion of their strength and means, to defend themselves; and these he will bless and crown with success. If he forsake a nation he will leave it to infatuated measures, to divided counsels, to supineness, to discord, treachery, and treason; or he will counteract its efforts, and thus effectually accomplish his designs of vengeance. Peace, health, and plenty, will be blessings flowing from his favor; sword, pestilence, and famine, will be the messengers of his wrath. Sometimes his hand will be invisible, and sometimes conspicuously displayed; but in either case its operations will be sure and irresistible whether to defend or to destroy.

In establishing the point before us, the proof on which I propose principally to rely is of the historical kind. The principles of human nature and of society do indeed offer strong and conclusive evidence of the same truth, and these will be occasionally taken to our aid in the answering objections to our doctrine. But these principles have been so often and so clearly explained and applied to this subject, that nothing seems capable of being added to what must already be familiar to you; and as the conclusions deduced from them have, notwithstanding, been lately denied by a daring spirit of innovation and infidelity, I think it most proper, in every view, to treat the subject historically and to show that the theory we maintain is incontrovertibly supported by fact. In pursuing this design we assume it as a principle that the plan of Providence, or the divine government, is uniform in its execution, so that what hath happened in all time past, may be expected to happen in all time to come. Atheists and infidels may, indeed, deny that the course of human affairs is under the direction or providence of God; but even they cannot, with a shadow of truth or candor, deny the fact, that nations have actually stood or fallen by the test in question, nor can they easily resist the belief that the future will resemble the past.

To the faithful page of history then let the impartial appeal be made. Let the Heathen, the Jewish, and the Christian nations pass in review before you, and you will find their prosperity or their adversity, meted to them by the measure we have examine. What was it that produced the most ancient and the most awful desolation and extinction of nations that the history of the world records? The sacred volume will inform you—“God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually—And the Lord said I will destroy man whom I have created, from the face of the earth, both man and beast—for the earth was filled with violence: And God looked upon the earth and behold it was corrupt; for all flesh had corrupted his way upon the earth: And God said unto Noah—The end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them, and behold I will destroy them with the earth.” Let every believer in revelation mark the cause which inspiration here assigns, for bringing the waters of a flood on the world of the ungodly: —Let him mark and remember that it was for general corruption and impiety; and let this be in his mind, the attestation of unerring truth, that, at least in one, and that the most conspicuous of all instances, the Deity forsook and destroyed the nations—even all the nations of the earth—because they had forsaken him. Let it also be remembered, that this happened in the infancy of the world, for the express purpose that it might be a warning to every succeeding generation of men; and that no reason can be assigned why the Deity should not be as much displeased with impiety now as then, nor why he should not punish the people who are guilty of it; though, for wise reasons, he may not use a miraculous but an ordinary method of chastisement.

But examples of the same import multiply upon us in perusing the sacred records. Why was it that “the Lord rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven, and overthrew those cities and all the plain, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew up on the ground.”? It was “because the cry of Sodom and Gomorrah was great, and because their sin was grievous”—Because nameless deeds of wickedness were perpetrated there, and ten righteous persons could not be found, as “the salt of the earth” to qualify its corruption, and to extinguish the fire of heaven. What was the cause of the destruction of the Canaanitish nations, whom the Lord drove out before the children of Israel? Was it mere arbitrary pleasure of Jehovah to destroy them, that he might make room for the settlement of his chosen people? Such is the favorite but false representation of infidels. Hear the account of Scripture, and observe, that it is held up as a warning to the Israelites themselves; “Defile not yourselves in any of these things; for in all these the nations are defiled that I cast out before. And the land is defiled; therefore I do visit the iniquity thereof upon it, and the land itself vomiteth out her inhabitants. Ye shall, therefore, keep my statutes and my judgments, and shall not commit any of these abominations; neither any of your own nation, nor any stranger that sojourneth with you: For all these abominations have the men of the land done which were before you, and the land is defiled.” Why was it, that the awful “voice from heaven: said to the proud King of Babylon, “O King Nebuchadnezzar to thee it is spoken—drive thee from men and thy dwelling shall be with the beasts of the field!” It was that he might “know that the Most High ruleth in the kingdoms of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will:—And all the inhabitants of the earth are reputed as nothing and he doth according to his will in the army of heaven and among the inhabitants of the earth; and none can stay his hand, or say unto him—what dost thou?” Why was it that, to the son and successor of this haughty monarch, the appalling, unconnected, self moved hand, came forth, and wrote on the wall of his palace—-“Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin—God hath numbered thy kingdom and finished it; thou art weighed in the balance and found wanting: Thy kingdom is divided and given to the Medes and Persians”? It was because he had not “humbled his heart” in the contemplation of his father’s doom. “But had lifted up himself against the Lord of Heaven”—-had profaned the vessels of his sanctuary—-“and the God in whose hand his breath was and whose were all his ways he had not glorified”—-Therefore “in that night was Belshazzar the King of the Chaldeans slain, and Darius the Median took his kingdom.”

These instances—so pointed and powerful that the aid of enforcement would but encumber them—demonstrating the truth on which I insist, are found in holy scripture; but observe that they all relate to Heathen nations, to nations that had no special revelation—had nothing but those great principles of religion and morality which the light of nature or the report of tradition taught, to guide them in the path of duty: And for the violation of these you have heard their destiny.

But if leaving the testimony of sacred, we resort to that of profane history itself, we shall find the same account. We shall find that when a nation of the heathen world regarded, in any tolerable degree, (for not one regarded in a high degree), the principles of religious and moral duty which I specified at the entrance, then they were most prosperous, and that when they wholly departed from these, then they were speedily destroyed. If the limits to which I am confined did not forbid it, the talk would not be difficult to evince, beyond all contradiction, from the most authentic accounts of these nations, that religion and morality, mistaken and imperfect as they were among pagans, were still their strength and security, and that a disregard to these always preceded their dissolution. The truth of this representation is recognized (it may be, some hundreds of times) by their own writers. The fact was so evident and notorious that it forced itself on observation, precluded denial, passed at length into one of those settled maxims of which there is neither doubt nor controversy, mingled itself with all their public instructions, and was regarded as essential in all their political institutions. The most learned and eloquent of the Roman philosophers and orators accounts for the superiority of the Roman state in language such as this, “We exceed not the Spaniards in number, nor Gauls in strength, nor the Carthaginians in subtly, nor the Greeks in arts, nor the Italians and Latins, who were the original inhabitants of this country, in natural strength of mind; but it is in piety and religion, in discerning that all things are directed and governed by the immortal Gods, that we have excelled all the nations and people of the earth.” Even a father of the Christian church has this remark, “That God would not give heaven to the Romans, because they were heathen, but he gave them the empire of the world, because were virtuous.” A writer of a far different character makes an extravagant assertion “That for several ages together never was the fear of God more eminently conspicuous than in the Roman republic.” But he is strictly correct, when he says, “That religion produced good laws, good laws good fortune, and good fortune a good end in whatever they undertook.” Nor are these observations less applicable to other nations of heathen antiquity. Consult the rise and fall of the Assyrian, the Persian, and the Macedonian empires, or of the free states of Greece, and you will find that their political prosperity waxed or waned very much by the measure of their religious and moral character. Their religion—I know and repeat it—was absurd, and their morals comparatively impure, but the degree of rectitude and purity which they possessed was their safety, and the contrary was their bane. I do not hold them up as objects to be envied or as examples to be imitated in the gross. They became eventually the curses and scourges of the world; but they became so by their degeneracy, which proved in the end their own destruction and—this is the point for which I contend.

In regard to the Hebrew nation, no man that has read his bible can be ignorant, that it stood or fell by the rule that has been given. Its whole history, indeed, is, and was intended to be, little else than the history of the truth of the doctrine which I now maintain. When the people “served the Lord God of their Fathers, with a perfect heart and with a willing mind:”—When they “did justly, loved mercy, and walked humbly with their God.” Then they had rest; or if their enemies attempted to injure them, “one man chased a thousand, and two put ten thousand to flight.” On the contrary, when they forgot the Lord and walked after the imagination of their own evil heart, then they experienced every sore and destructive calamity; till at length they were completely removed out of their own land, subjected to a most humiliating captivity and bondage, while their country was ravaged and rendered desolate for the space of seventy years. The text is but a single instance, among passages innumerable, in which the general truths here stated were brought in the most striking manner to their remembrance. Read with attention the 26th chap. Of the book of Leviticus, and you will there, find specified at large, the promises and the threatening which the whole of their subsequent history demonstrates to have been strictly fulfilled. But the most awful example which the Jews offer to the world, is in the punishment which they received after their rejection and crucifixion of the Messiah, and the persecution of his apostles and disciples. An historian of their own nation, who was an eye witness of what he records, gives such an account of the overthrow of their temple, city and nation, as has not its parallel in the annals of the world. It was accompanied by the most awful and manifest displays of the divine indignation, insomuch that Titus the Roman emperor confessed that it was the hand of God, rather than his own military prowess, that effected their destruction. From that time to the present hour, the Jews have been vagabonds over all the earth, furnishing a monument and miracle of the divine displeasure, against a nation that no mercies or judgments could reclaim.

If, turning form the Heathen and the Jews, we fix on the history of Christian countries, we shall find it still confirming the fact asserted, that when they have conformed to those principles of religious and moral duty which constitute the rule of their obedience to God, they have been protected and prospered, and when they have thrown aside a regard to these, they have been blasted and cut off.

It was not till more than three centuries after the birth of our blessed Lord, that any state professed a national attachment to the religion which he taught. During this whole period, however, the light of that religion in all its purity, was diffused over many countries, and rendered them, in a degree, responsible for a conformity to it. The consequences of refusing to be guided and influences by it have been awful indeed. The whole region of Asia Minor & of ancient Greece, where the most flourishing Christian churches were planted by St. Paul, have long since experienced the fulfillment of the threatening which the beloved apostle was commissioned to denounce. Not only have the inhabitants of that region been deprived of the gospel which they abused, but, under the Mahomedan power, they have sunk into the most gloomy political bondage;—slavery and wretchedness have been brooding over them for more than a thousand years.

A similar fate was reserved for the Roman Empire. Long had its impieties and prostrate morals been portending its fall. But when the bloody and relentless persecution, of the followers of Jesus were added to its other crimes, the vengeance of heaven could no longer be delayed. A celebrated historian of this period, whose prejudice would not suffer him to learn from it the truth of the Christian system, intimates that there is reason to believe, that in one space of about fifteen years, “war, pestilence, and famine, consumed the moiety of the human species.” Under Constantine the Great the Roman Empire became Christian; and then again her political power and internal happiness had a short revival. But in the revolution of a few years the corruptions of Christianity debased and degraded the worship of God, rent and divided and dishonored his church, and admitted of licentiousness in principle, and immorality in practice. Then desolation entered as a flood. And inundation of barbarians broke in upon the empire, razed it to the foundations, massacred its inhabitants, swept away every monument of grandeur, every achievement of art, every comfort of life; so that this period has obtained, descriptively, the appellation of the dark ages, and furnishes but scanty documents for its own history. To such a length, indeed, did barbarism and ignorance proceed, that for several centuries there was scarcely a term in the languages of Europe by which literature or learning could be expressed. This was the period in which all the abominations of Anti-Christ reigned without controul. It was the period too in which human misery was at its height. During its continuance, several of the plagues and phials of wrath, predicted in the apocalypse, were emphatically poured out. The imposter Mahomet arose, and with sword and rapine extended his power and established his superstition over a fourth part of the then discovered globe. The crusades, which the spiritual infatuation of the princes and nations of Europe carried on for a series of years to dispossess the infidel Mussel men of the holy land, beggared and depopulated the countries whence they proceeded, while oppression, rapacity and violence at home filled the cup of sorrow to the full. To recount the sufferings of those who bore the Christian name, and subjected it to reproach by their follies, hypocrites, impieties and vices, during this period, would carry me far beyond the proper bounds of this discourse. At length a glorious reformation began to dawn on the benighted and miserable nations. And then—let it be distinctly observed—then began, also, and amelioration of their political state. To this reformation, beyond all question, as the fundamental and most efficient cause, has been owing the literary improvement, the civil happiness, and the general superiority of Europe over all the other people of the earth. Its influence, was by no means confined to those nations that were active in promoting it, but was greatly extended to those that contended against it. Power, tyranny and superstition, were obliged to relax their demands, and to assume a milder tone, to prevent the extension of that which they equally hated and feared.

We see, then, that the general aspect of the Christian history confirms our position in the fullest manner. To descend to particulars, is forbidden by the limits to which I am confined. Let me, only, call your attention, for a moment, to the origin of that Happy state of society which our own country has experienced, even since our forefathers formed political establishments in it. Can anyone deny that those establishments owe their excellence to the fervent piety and pure morals of their original founders? It is impossible to deny it. To Christianity, in its genuine spirit, we have rendered our country the envy of the world, which we cannot change but to an infinite disadvantage, and which, if we are careful to maintain them, will be our everlasting glory and defense.[*] Our defense they have certainly been in time past. From the fist settlement of these States till the present hour, the signal care of heaven, in preserving us from all machinations of our enemies, has been such as to confound unbelief itself, and to furnish a most comfortable illustration of the truth I inculcate. Often, very often, both in early and latter times, has the safety and salvation of our country been dependent on circumstances which no human means could manage or control, and on discoveries which no human wisdom could make. In all these cases, when standing on the brink of destruction, the good providence of God has interposed and saved us; so that it would seem as if it were only necessary that we should be in imminent danger, in order to see a wonderful interposition of the divine hand to deliver us from destruction—God of his mercy grant that the impieties which now prevail, may not change his dispensations toward us!

If it be demanded, after all, whether history will not demonstrate that some nations distinguished for religion, have not suffered by the attacks of others, and whether some that have been distinguished for irreligion, have not been prospered?—the demand may be met without the least disadvantage to my argument. As a reply to the whole it would, I think, be sufficient to remind you of the remark already made, that, as in all the other divine dispensations, so in this, it is to be expected that there will be some appearances which seem to be exceptions to a general rule, which we must resolve into the sovereignty of God—or into our imperfect views and knowledge of his designs; and that such appearances ought by no means to weaken the influence of the general rule, or to diminish our care to walk agreeably to it. But though this might be a sufficient answer to the inquiry, and though there may be some real need for it, in a few cases that might possibly be specified in regard to this subject; yet I am persuaded that there is much less occasion for such remarks on this subject, than on almost any other, where the ways of God are concerned. In answer to the first part of the demand, let it be observed that the conformity of nations to the standard which ensures protection is often very imperfect, while yet the fear of God and obedience to his laws are considerably regarded. In these circumstances the Deity may, and commonly does, afflict to a certain degree, with a view to reform and not to destroy. If reformation take place, the correction is withdrawn, and his favor returns. This is precisely the statement of the text, where we are assured that if a nation seeks the Lord he will be found of them. But if reformation do not take place, chastisement will continue and crease, till, at length, the people who prove incorrigible will be finally destroyed. This accounts for the appearance –. It shows that the divine blessing is not only conferred on obedience but is proportioned to it. But my recollection does not serve me for a single instance, in which a nation, however small, that could make any plausible pretension to religious and moral purity, was ever totally destroyed. On the contrary, a number of the small states of Europe have been almost miraculously preserved, when contending for real liberty and religion, against the most powerful and impetuous nations of the earth. Different, I know, has been the effect of the struggles of some of those nations, lately, to preserve their very existence. They have been carried away like dust before the whirlwind. But what has been the cause? Examine it well, and you will find the doctrine I inculcate very powerfully supported by the result. You will find that the punishment inflicted on these nations, has been most wonderfully proportioned to the measure of their and notorious hypocrites, impieties and immoralities.

But it is time to turn to the opposite part of this enquiry, and attempt to answer what many will esteem a more formidable objection, namely—that impious and immoral nations have sometimes been blest and prospered. It may even be supposed, that this point has already been yielded in a measure, when it was suggested, that the conquerors of the earth have frequently been distinguished by a disregard to everything sacred. Such a conclusion however, does not follow with justice, from the premises whence it is drawn. Why may not God, for the purposes of chastising those whom ultimately he intends to save, confer success on the unlawful enterprises of wicked nations as he does on those of wicked individuals, and yet, in both cases, be only preparing the way for the final and more awful ruin of the transgressors? That he may do this is not only possible but in some instances certain. There cannot be two grosser errors than to believe, that military success is always a mark of the divine approbation, and that conquest or extended dominion always secures happiness and prosperity to a conquering nation. As to the first, which is a favorite idea with some, that military success is a proof of the divine approbation, I would beg of those who cherish the delusion, to consider where it will lead them. It will lead them unavoidably to maintain, that Alexander and Caesar, that Goths and Vandals, that Turks and Tartars, have been the most distinguished favorites of Heaven, for in military success none have been equal to these. No, my brethren, military success is, by itself, no proof of the divine patronage. God may, as already intimated, use a nation as the rod of his anger to chastise the guilty, and then he may break and burn it, and make its destruction a useful warning to every beholder. We are assured by scripture, that de did so with the Assyrian empire of old—Nay, he hath done it in every age, and it is his usual method of procedure. Military success, in war merely defensive, May be evidence of the divine favor; but in every other case, if we judge from experience, the presumption is against the victor. Neither is conquest and dominion a proof that the conquering nation is truly prosperous. A few of its distinguished chiefs may acquire fame and wealth, while the mass of its inhabitants are wretched in the extreme. The fact commonly happens thus—It happens thus remarkably, at present, with that nation of Europe, that is subduing others, and threatening us. Is it really prosperous? Are its citizens happy? Have they, while they have been ravaging and subduing other kingdoms, possessed true national felicity among themselves? No, assuredly—Fear and anxiety, convulsion and terror, massacre and blood, the destruction of arts, of property, of all domestic enjoyment, of all religious, moral, and social principles, of all that renders existence not a curse, has reigned in the midst of them, with infernal triumph. It is even true, that among all the nations that they have conquered, rendered tributary, pillaged, partitioned, bartered and trafficked away, not one has suffered more than themselves. The volcano which has poured desolation in burning torrents on every circumjacent region has still glowed most intensely at the centre of its force, and there, in its own bowels and crater, with the most rapid and energetic fury, it has tortured, and transmuted and consumed, every useful material, which heaven, nature, art or accident, has offered to its touch. The scene with this nation is yet unclosed; and I grant the conclusion, that its fate will subvert the doctrine of my text completely, if its catastrophe be not an illustrious display of the divine indignation: For in the most shocking and avowed atheism, in the most marked contempt of all the dictates of religion, both natural and revealed, it has exhibited a specimen, which, as far as my knowledge extends, has never been witnessed before since the creation of the world. But that it is ultimately doomed to peculiar judgments, I have, for myself, no more doubt than of the truth of God—no more question than of my own existence. And I should feel that I acted as a traitor to my sacred trust, if, when the success of this nation are held up (and thus they have been) as a contradiction to the word of life, and when they stand particularly opposed to the truth which, from that word, I am, this day, called to maintain, I should hesitate to make this avowal, and to make it publicly.

Perhaps some will now be ready to remark, that the prosperity which it must be confessed, accompanies a national observance of the divine laws is owing to the natural influence which religious and moral observances have to produce this desirable effect. Be it so; this influence I do not deny, but maintain. But remember, that this natural connection between piety and prosperity, vice and ruin, is still the appointment of God, and even, on this plan, is as much his order as if it had been made for every particular case, in which its effects are felt. Scripture and experience, however, do, I think, concur in teaching, that beside this natural connection, God does often and especially interfere by his providence, both to preserve and bless those who obey him, and to destroy those who reject and despise his laws.

It may be objected, finally, that the representation given, goes to unsettle an important principle which has generally been understood to belong to the Christian system, namely, that the present is a state of probation, and not of retribution. A short answer to this would be, that whatever doctrine is established by facts, is not responsible to theory for its consequences, and that all that has been said, is but an appeal to undeniable experience. But I will never answer thus where Christianity is even supposed to be implicated by it—its dictates are eternal truth. I grant that the doctrine I advocate requires some explanation in regard to this point, and I am confident it may be given in a manner that shall be perfectly satisfactory to every candid mind, and even illustrative and confirmatory of the doctrine itself.

It will be remembered, then, that the concession has already been made and repeated, that righteous nations may experience partial and temporary sufferings, and that those of an opposite character may obtain some temporary, or rather apparent advantages. This will be a call for the faith and patience of pious men, who may suffer in the general calamity, and may teach them to look forward to that better world “where the wicked cease from troubling, and where the weary are at rest.”

But in reality, the doctrine which teaches that men are not to look for rewards or punishments in this life, though true and important when judiciously applied to individuals, is often mistaken even in its relation to them, and when applied to nations and considered as a general principle, is not true at all. It is only in this world that communities as such have an existence or character. In the world to come the whole of our race will appear as individuals, and not as communities. If any, retribution, then, be awarded to nations as nations, it must be in the present state, and not in that which is to come. But it appears to be of the highest importance in the moral government of God, that national character should be the subject both of his favor and of his frowns; and this, consequently must be experienced in the present state. It accordingly does take place in fact, and is generally to be expected.

It should also be considered, that the established connection between virtue and prosperity, vice and ruin, which has already been noticed, is much closer, and more powerful, in relation to communities than to individuals; and draws after it a present retribution as an unavoidable consequence. It is, indeed, the general tendency of virtue to produce happiness, and of vice, to beget misery, in every individual who practices the one or the other. But in a vicious society, a virtuous man will suffer in many ways from his unavoidable connection with wicked associates. In a virtuous society, on the contrary, a vicious man has many enjoyments, and derives many advantages, merely from the circumstance, that the mass of the community are not like himself. They form, as it were, a barrier around him, and their goodness is the food on which his vices live and prey. But when the greater part of the individuals of a community come to posses this character, that is, when a nation as such becomes abandoned to vice, there is no longer any suitable tie by which it can be holden together and every salutary source from which safety and happiness can proceed is dried up. Without religion there can be no obligation of an oath, no sufficient sanction to a promise, and consequently no rational and solid ground of confidence—no operative and universal motive to truth, fidelity, and integrity, either in the intercourse and transactions of individuals with each other, or in their engagements to the public. Without morality all regard to the happiness and claims of others, to public and private justice, to parental authority, to filial duty, to conjugal fidelity, to temperance, chastity, sympathy, charity and humanity, is wholly destroyed, or left to rest on the airy principle of honor, or the dangerous foundation of personal inclination. Man becomes a selfish sensual brute. And when the component parts of a nation of this description it is impossible that they should remain united, except by the most powerful compulsion. Civil liberty cannot exist at all in such a community. Society must either be dissolved entirely, or it must assume a state and form which is a greater evil than dissolution itself.

On the other hand, where religious and moral principles, in their vigor and purity, pervade the great body of individuals in a state, every social tie is strengthened, every part of the community draws toward the good of the whole, society is easily governed, because it requires but little governing, civil liberty may be extensively enjoyed, and all the happiness of the social state will be fully realized. So intimately is religion and morality connected by a natural bond, or rather by the divine constitution, with the safety and prosperity of nations. So just is the remark that any kind of religion in a state is better than none: And it will be manifest to ever one who pursues the clue here given, that just in proportion as the religious and moral system of a nation is pure in that proportion will it naturally tend to promote the public safety and happiness; and consequently that the Christian system, as the purest of all, is the best of al—the best of all, for communities, as well as for individuals—“having the promise of the life which now is, as well as of that which is to come.”

But the conclusion which I am here particularly to form, and I think it may now be formed with advantage, is—That nations do receive a retribution in the present world according to their several characters: —That this cannot be otherwise if they are every treated as nations, and that the divine constitution unavoidably produces this effect.

On the whole, then, the doctrine which I proposed to demonstrate has been shown to be supported by facts, and to be sanctioned by the soundest principles of reason—It has been proved to be true; and how, and why, it is true, has been explained.

A few important deductions from what your heart will now conclude the discourse.

1. We may learn from what has been said, how totally devoid of truth it that darling principle of modern unbelievers, that a nation may be as happy without religion as with it.

This a mere Atheistic hypothesis and speculation, not only unsupported by any experience, but in direct hostility, as we have seen, with the experience of all nations, in all ages of the world. It is one of the most daring, extravagant, and unaccountable chimeras, that every entered the head even of a metaphysical infidel; and nothing but the most inveterate hatred to God and his laws could never have given it birth. Yet it has been and with many who are not destitute of influence, I fear it still is, a tenet for which they have a peculiar fondness. They endeavor to give it currency by professing separate religion form morality, and to be advocates for disarming the former, and warm contenders retaining the latter. But that morals can exist without religion, is as destitute of proof and probability, as the whole position is without this qualification. No nation has ever yet existed where this phenomenon of morals without religion has made its appearance; and there is no reason to believe that it is even possible from the very nature and structure of the human mind. Our late venerable President therefore, in his farewell address—well knowing how earnestly some were laboring to inculcate this horrid doctrine—did with great propriety warn us not to admit the idea that “morals can be separated from religion.” The very truth is, infidels first endeavor to exclude religion from the state, that they may give the name of morality to any set of principles they may choose to adopt, and that thus, in the end, they may fully accomplish their wishes by getting rid of both. Be warned, my brethren, by what you have this day heard, be warned, that without religion and morality, harmoniously united, we are an undone people; without these our civil liberty and social happiness cannon possibly be preserved. Let us esteem these our principal and most essential defense at the present hour and let us be thankful to God that he has given us a chief magistrate who, in looking to the defense of the country, has seen this important truth in its just light—has seen that we must implore and obtain the favor of God, or all other means will be ineffectual. Let each of us be deeply convinced of this as a practical truth: And therefore I add—sadly, that viewing the religious and moral state of our country in connection with this subject, we may see how urgent is the call for humiliation, fasting and prayer, for which this day has been expressly set apart.

If God deals with nations according to their relative light and advantages, and where he has given much, will always require the more—and such we have seen really to be the case—verily, my brethren, this is a truth of most solemn import to the people of America at this time. Our advantages, in point of religious and moral information, have been second to those of no people upon earth; and our circumstances for carrying this information into practice are, I believe, superior to those which any other nation now enjoys. Has our improvement then, been, in any measure answerable to our privileges? Is our moral and religious state at present, such, in any degree, as our circumstances demand? Every serious and candid mind, penetrated with grief, will answer, no! It is a most melancholy fact, that we have greatly forgotten, and departed from the Lord God of our fathers. Of the arm that has so often and remarkably defended us in the hour of distress,—that so lately and marvelously prospered us when we contended for our independence—we have been unmindful. We have returned base ingratitude for the favors of heaven, which we have experienced as a nation. Those civil and religious privileges which God from the first bestowed upon us, and which he has all along continued to us, we, have abused in the service of sin. There has certainly been a loss, and not an increase of piety and morality, in our country, since our late revolution. Infidelity does most awfully abound among all descriptions of people from the highest to the lowest. Profaneness of every description, most lamentably prevails. The ordinances of God’s day and house are neglected, deserted, and despised. His word is openly ridiculed and his Son treated as an imposter. A dissoluteness of manners and morals, like a deadly leprosy, is fast spreading itself among the people at large, and far beyond any former example.

In these circumstances we are threatened with a war from the most powerful, the most active, and the most insidious nation upon earth. A nation which has already proved a scourge to many others and which appears to be permitted by God to affect its designs for the express purpose of chastising this guilty age—this age of infidel reason. What is the language of this situation? It undoubtedly is—“God hath come forth against you for your iniquities—your conduct toward him is changed for the worse, tremble left is toward you should change likewise. Turn unto him speedily, left his anger consume you.” Yes, my brethren, let our opinion be what it may of second causes, manifest it is, that the Deity hath a controversy with us.—For some time past he hath given us intimation of his displeasure, but now he hath, as it were, set himself in array against us. Let us then truly humble ourselves before him. Let us “repent in dust and ashes” in his presence this day. Let us mourn our land defiling iniquities. Let this be to us a day of humiliation, not merely in name, but in deed and in truth. Let us “rent our heart and not our garment:”—let us, in very truth, plead with him, in secret and in public, “to turn us from our sins and to turn his anger from us.” Let us entreat for this, as sensible that we are pleading for our very existence. Let us pray that God would pour out his holy and blessed spirit upon the people, to convince them effectually of sin; and to turn them effectually to himself. Let us pray that he would bless the rulers of our land, and make them examples of real religion and found morals:—That he would dispose them all, instead of countenancing and encouraging vice and infidelity by their practice and profession, to set themselves against it, as that which will destroy both them and those they govern, if it proceed much farther. Let us resolve in God’s name and strength, to act as well as to pray. Let those who have power be conjured to use it for him from whom all power is derived and to whom they must solemnly account for the manner in which they employ it. Let each of us, in our proper places and stations, be earnest, resolute and persevering, in promoting the work of reformation. Let us each reform himself, and endeavor to set an example, purer than heretofore, of true religion, and of the discharge of every moral, social, and relative duty. Believe it, my hearers, the serious hour is come. Reformation or severe chastisement is just before us. But if we will turn unto the Lord in the manner recommended, and will, at the same time, “play the man for the people and cities of our God,” by unanimity and strenuous exertion in the cause of our country, we have nothing to fear. God will be “found of us” if we “shall seek him”—This is the assurance of the text—It encourages repentance and reformation, by the kindest and most gracious promise. If we, in very deed, put our trust in him, and act, as those who do so, let the world rise in arms against us, still we shall be safe. As therefore we love our country, our souls or our God—as we regard the happiness of time or of eternity—let us be on the Lord’s side that he may be on ours.

3rdly, Finally—Let us be thankful for the past experience we have had of the divine mercies. Hitherto we have been preserved in peace, while most other nations have been at war; and though we have not been without correction, yet light, indeed, hath been its strokes in comparison with our sins. Countless and peculiar favors are still continued to us—domestic happiness and enjoyment, health and comparative plenty— the means of knowledge and information—a spirit of growing concord, and above all, the precious gospel of the Redeemer, and the sweet and heavenly hope that it inspires. These mercies, preserved to us when we have so little deserved them, should swell our hearts with the humblest and liveliest gratitude. And let this gratitude be expressed, in leading us truly to our heavenly Father; and again I repeat it, we shall be safe in this world and happy in that which is to come. ——-Amen.