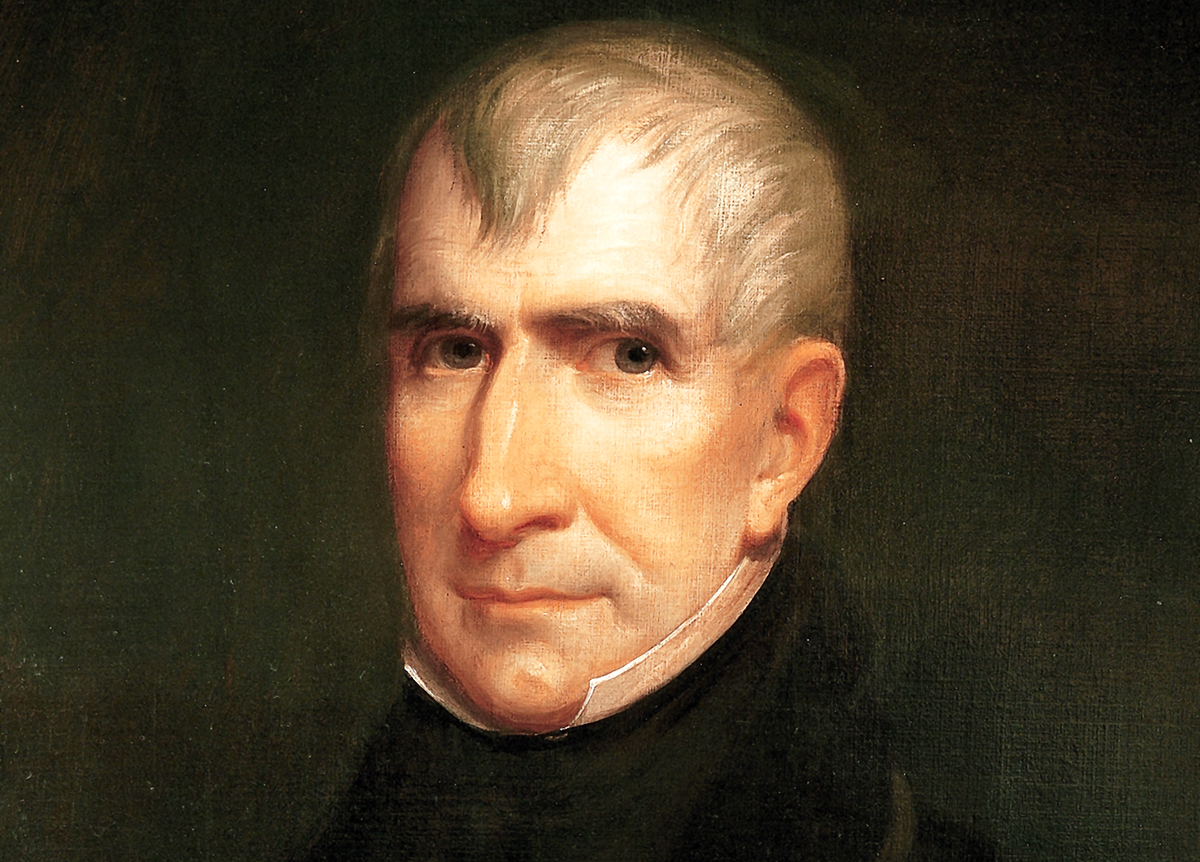

Isaac Parker (1768-1830) Biography:

Isaac Parker (1768-1830) Biography:

Born in Boston, Parker graduated from Harvard when 18. After teaching for many years, he began studying law. Admitted to the law profession in 1789, Parker relocated to Castine, Maine, and became its first lawyer. In 1796, he was elected to Congress as a Federalist and served one term. Leaving Congress, Parker served as a US Marshall from 1797-1801 under President John Adams. Five years later, he relocated to Portland (where he remained until his death) and became a judge on the Massachusetts Supreme Court. He taught law at Harvard for eleven years, was an overseer at Harvard, and a Trustee of Bowdoin College. In 1820, he served as president of the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. Two of his famous orations that were published included his Oration on Washington and Sketch of the Character of Chief-Justice Parsons.

A

SKETCH

OF THE CHARACTER OF THE LATE

CHIEF JUSTICE PARSONS,

EXHIBITED IN

AN ADDRESS TO THE GRAND JURY,

DELIVERED

AT THE OPENING OF THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT

AT BOSTON,

ON THE TWENTY-THIRD DAY OF NOVEMBER, 1813.

AFTER THE

USUAL CHARGE.

PUBLISHED AT THE UNANIMOUS REQUEST OF

THE GRAND JURY AND THE BAR OF SUFFOLK.

BY ISAAC PARKER, ESQ.

ONE OF THE ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THAT COURT.

BOSTON:

PRINTED BY JOHN ELIOT, COURT STREET

1813.

INTRODUCTION.

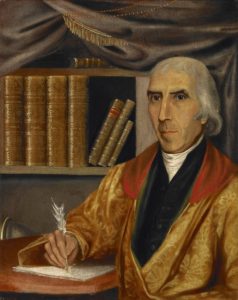

CHIEF JUSTICE PARSONS was born in February, 1750, and received the rudiments of his education under the celebrated Master Moody, at Dummer Academy, in his native parish of Byefield, within the ancient town of Newbury. His father was minister of that parish. He received the ordinary honours of the University in Cambridge in 1769. He entered upon the study of the law under the late Judge Bradbury, in Falmouth, now Portland, and while there kept the Grammar School in that town. He practiced law there a few years; but the conflagration of the town by the British obliged him to withdraw to his father’s house, where he met Judge Trowbridge, as stated in the address. He, in about a year from this time, opened his office in Newburyport. He has been honoured with degrees of Doctor of Laws, from the University of Cambridge and Dartmouth College, and from Brown University in Rhode Island. In 1801, he was presented by President Adams with a commission of Attorney General of the United States, which he did not accept. He had been also, by the choice of our state Legislature, one of the Commissioners to settle a controversy with the State of New York. He continued faithful to his chosen profession, until he was appointed Chief Justice of the State, which was in the summer of 1806.

While this Address was passing through the press, the following letter was received, and the testimony it contains cannot fail to gratify the publick.

Cambridge, 1 December, 1813.

My Dear Sir,

SINCE I handed you the note containing the testimonial of Professor Luzac to our venerated friend’s rank, as a proficient in Greek learning, I have received a letter from my respected friend Vanderkemp, from which I extract the following.

“We have then lost that ornament of the bench, that brilliant gem of your country.—The Giant of the Law, the polished Greek scholar, is gone. I knew him: I had learned to revere him through my friend Luzac. You introduced me to him, and he afterwards honoured me by visiting me three times at my lodgings in Boston. For this I was indebted to my deceased Luzac, whom he respected. I flattered myself that I should yet gather a rich harvest from his acquaintance; and he seemed inclined not to disappoint me “Make my compliments to Mrs. V.” these were his last words to me, “and tell her she ought to command you to return soon to Boston.”—Such a delicate compliment from a Parsons, was a treasure to an epicurean, in regard of praise.”

The good man then indulges his hopes, in a strain of enthusiasm, that the excellent properties of our deceased luminary may excite the emulation of professors of the law who survive him, and of those who may hereafter arise.

I am, dear Sir,

Your most obliged servant,

D. A. TYNG.

ADDRESS, &c.

Gentlemen of the Grand Jury,

At the first assembling of this Court in this place, after the death of that eminent man who has for some years been its head and ornament, our minds are naturally and forcibly led to a contemplation of those extraordinary qualities, which had secured to him an uncommon share of the veneration of his fellow-citizens.

Eulogies upon the dead have become, in publick estimation, but equivocal evidence of their virtues and talents, and indiscriminate panegyrick conveys no honour to its subject and no benefit to survivors.

But the illustrious dead—those who have brought signal reputation to their country, who have aided in rearing and supporting the edifice of state, whose learning has been devoted to general use, whose private virtues have afforded an example to the young—whose strength of mind and character has added to the dignity of man—these ought not to be forgotten.

The stores of human wisdom could never be increased, did not such men speak, even though dead. Their lives, and their actions, recorded with truth, are the voice of history speaking to successive generations, calling them to emulate what is great and noble, and shewing the practicability of almost infinite improvement in the capacities of the human mind.

I shall not be accused of fulsome panegyrick, in asserting that the subject of this address has for more than thirty years been acknowledged the great man of his time. The friends who have accompanied him through life, and witnessed the progress of his mind, want no proof of this assertion; but to those who have heard his fame, without knowing the materials of which it is composed, it may be useful to give such a display of his character as will prove, that the world is not always mistaken in awarding its honours.

From the companions of his early years I have learned, that he was comparatively great, before he arrived at manhood; that his infancy was marked by mental labour and study, rather than by puerile amusements; that his youth was a season of persevering acquisition, instead of pleasure; and that, when he became a man, he seemed to possess the wisdom and experience of those who had been men long before him. And, indeed, those of us, who have seen him lay open his vast stores of knowledge in later life, unaided by recent acquirement, and relying more upon memory than research, can account for his greatness only by supposing a patience of labour in youth, which almost exhausted the sources of information, and left him to act rather than study, at a period when others are but beginning to acquire.

His familiar and critical knowledge of the Greek and Latin tongues, so well known to the literati of this country, and to some of the most eminent abroad, was the fruit of his early labours, preserved and perhaps ripened in mature years, but gathered in the spring time of his life (a) His philosophical and mathematical knowledge were of the same early harvest, as were also his logical and metaphysical powers.

Had he died at the age of twenty-one, I am persuaded he would have been held up to youth, as an instance of astonishing and successful perseverance in the severest employments of the mind.

Heaven, which gave him this spirit of industry, endowed him also with a genius to give it effect.

There were united in him an imagination vivid, but not visionary, a most discriminating judgment, the attentiveness and precision of the mathematician, and a memory, which, however enlarged and strengthened by exercise, must have been originally powerful and capacious.

With these wonderful faculties, which had, from the first drawings of reason, been employed on subjects most interesting to the human mind, he came to the study of that science, which claims a kindred with every other—the science of the law.

This was a field worthy of his labours and congenial with his understanding. How successfully he explored, cultivated and adorned it, need not be related to his cotemporaries.

Never was fame more early or more just, than that of Parsons as a lawyer. At an age when most of the profession are but beginning to exhibit their talents and to take a fixed rank at the bar, he was confessedly, in point of profound legal knowledge, among the first of its professors.

His professional services were everywhere sought for. In his native county, and in the neighbouring state of New-Hampshire, scarcely a cause of importance was litigated in which he was not an advocate. His fame had spread from the country to the capital, to which he was almost constantly called to take a share in trials of intricacy and interest.

At that early period of his life, his most formidable rival and most frequent competitor was the accomplished lawyer and scholar, the late Judge Lowell, whose memory is still cherished with affection by the wise and virtuous of our state. Judge Lowell was considerably his senior, but entertained the highest respect for the general talents and juridical skill of his able competitor. It was the highest intellectual treat, to see these great men contending for victory in the judicial forum. Lowell, with all the ardour of the most impassioned eloquence, assaulting the hearts of his auditors, and seizing their understandings also, with the most cogent as well as the most plausible arguments. Parsons, cool, steady and deliberate, occupying every post which was left uncovered, and throwing in his forces, wherever the zeal of his adversary had left an opening. Notwithstanding this almost continual forensic warfare, they were warm personal friends, and freely acknowledged each other’s merits.

The other eminent men of that day, with whom Parsons was brought to contend, did full justice to his great powers. I have myself heard the late Governor Sullivan declare, he was the greatest lawyer living.

So rapid and yet so sure was the growth of his reputation, that immediately upon his commencing the practice of the law, his office was considered, by some of the first men our state has produced, to be the most perfect school for legal instruction.

That distinguished lawyer and statesman Rufus King, having finished his education at our university, at an age when he was qualified to choose his own instructor, placed himself under the tuition of Parsons; and probably it was owing in some measure to the wise lessons of the master, as well as to the great talents of the scholar, that the latter acquired a celebrity during the few years he remained at the bar, seldom attained in so short a professional career.

Many others of our principal lawyers and statesmen are indebted to the same preceptor for their fundamental acquisitions in the science of jurisprudence and civil polity.

I will not omit to mention, for I wish not to exaggerate his powers, that he enjoyed one advantage in his education beyond any of his cotemporaries, except the learned, able and upright Chief Justice Dana, whose long and useful administration in this court ought to be remembered with gratitude by his fellow citizens. I refer to the society and conversation of Judge Trowbridge, perhaps the most profound common lawyer of New England before the revolution. This venerable old man, like some of the ancient sages of the law in England, had pursued his legal disquisitions, long after he had ceased to be actively engaged in the profession, from an ardent attachment to the law as a science, and had employed himself in writing essays and forming elaborate readings upon abstruse and difficult points of law.

Many of his works are now extant in manuscript, and some in print, and they abundantly prove the depth of his learning, and the diligence and patience of his research.

When Parsons had retired to the house of his father, a respectable minister of Newbury, in consequence of the destruction of Falmouth by the British, he there met Judge Trowbridge, who had sought shelter from the confusion of the times in the same hospitable mansion. How grateful must it have been to the learned sage, in the decline of life, fraught with the lore of more than a half century’s incessant and laborious study, to meet in a peaceful village, secure from the alarms of war, a scholar panting for instruction and capable of comprehending his profound and useful lessons; and how delightful to the scholar to find a teacher so fitted to pour instruction into his eager and grasping mind. He regarded it as an uncommon blessing, and has frequently observed, that this early interruption to his business, which seemed to threaten poverty and misfortune, was one of the most useful and happy events of his life.

His habit of looking deeply into the ancient books of the common law, and tracing back settled principles to original decisions, probably acquired under this fortunate and accidental tuition, was the principal source of his early and continued celebrity.

He entered upon business also, after this connexion ceased, early in our revolutionary war, when the courts of admiralty jurisdiction were open and crowded with causes, in the management of which he had a large share. This led him to study with diligence the civil law, law of nations, and the principles of belligerent and neutral rights, in all which he soon became as distinguished as he was for his knowledge of the common and statute law of the country. Twenty-six years ago, when I with others of my age were pupils in the profession of the law, we saw our masters call this man into their councils, and yield implicit confidence to his opinions. Among men eminent themselves, and by many years his seniors, we saw him by common consent take the lead in causes which required intricate investigation and deepness of research.

In the art of special pleading, which more than anything tests the learning of a lawyer in his peculiar pursuit, he had then no competitor.

In force of combination and power of reasoning he was unrivalled, and in the happy talent of penetrating through the mass of circumstances which sometimes surround and obscure a cause, I do not remember his equal.

His arguments were directed to the understandings of men, seldom to their passions; and yet instances may be recollected, when, in causes which required it, he has assailed the hearts of his hearers with as powerful appeals as were ever exhibited in the cause of misfortune or humanity. I do not disparage others by placing him at their head. They were great men, he was a wonderful man. Like the great moralist of England, he might be surrounded by men of genius, literature and science, and neither he nor they suffer by a comparison. Indeed, he seemed to form a class of intellect by himself, rather than a standard of comparison for others.

Even his enemies, for it is the lot of all extraordinary men to have them, paid involuntary homage to his greatness; they designated him by an appellation which from its appropriateness became a just compliment, the Giant of the Law.

I have spoken now of his early life only, before he was thirty five years of age, and yet it is known that common minds and even great minds do not arrive at maturity in this profession until a much later period.

From this time for near twenty years I lived in a remote part of the state, and had no opportunity personally to witness his powers; but his fame pursued me even there. He was regarded by those lawyers, with whom I have been conversant, as the living oracle of the law. His transmitted opinions carried with them authority sufficient to settle controversies and terminate litigation.

On my accession to the bench, I had an opportunity to see him in practice at the bar, when he possessed the accumulated wisdom and learning of fifty-six years. Though laboring under a valetudinarian system, his mind was vigorous and majestic. His great talent was that of condensation. He presented his propositions in regular and lucid order, drew his inferences with justness and precision, and enforced his arguments with a simplicity yet fullness which left nothing obscure or misunderstood.

He seemed to have an intuitive perception of the cardinal points of a cause, upon which he poured out the whole treasures of his mind, while he rejected all minor facts and principles from his consideration.

He was concise, energetic and resistless in his reasoning. The most complicated questions appeared in his hands the most easy of solution; and if there be such a thing as demonstration in argument, he, above all the men I know, had the power to produce it.

With this fullness of learning and reputation, having had thirty five years of extensive practice in all branches of the law, and having indeed for the last ten years acted unofficially as judge in many of the most important mercantile disputes which occurred in this town, he was, on the resignation of Chief Justice Dana, selected by our present Governour to preside in this court. (b) This was the first, and I believe the only instance of a departure from the ordinary rule of succession; and, considering the character and talents of some who had been many years on the bench, perhaps no greater proof could be given of his pre-eminent legal endowments, than that this elevation should have been universally approved. Perhaps there never was a period when the regular succession would have been more generally acquiesced in as fit and proper, and yet the departure from it in this instance, was everywhere gratifying.

That the man who, in England would, probably, by the mere force of his talents, without the aid of family interest, have arrived to the dignity of Lord Chancellor or Lord Chief Justice, should be placed at the head of so important a department, was considered a most favourable epoch in our juridical history. (c)

The imperfect system of judicature, which had prevailed here until about that period, had rendered even great legal abilities inadequate to the establishment of a course of proceedings, and uniformity of decisions, so necessary to the safe and satisfactory administration of justice. There had been no history of past transactions preserved by a reporter, the sage opinions and learned counsels of departed judges had been lost even from the memory, and precedents were sought for only in the books of a foreign country. The most interesting points of law had been settled in the hurry and confusion of jury trials; and conflicting opinions of judges, arising from pressure of business and want of time to deliberate, were adjusted by that body which is supposed by the constitution and the laws to be competent to try the fact alone.

But a new era had arisen; our system had been wisely assimilated to that of England, imperfectly it is true, but with great improvements upon the old.

Its success depended much upon the character of those who were called to administer it. There were men upon the bench qualified to illustrate its advantages, (I need not say to a candid auditory that I speak altogether of others,) yet the appointment of parsons was hailed by all, and especially by those who best understood our past difficulties, with the highest approbation. His profound learning, long and uninterrupted employment in the country and in the capital, and especially his accurate knowledge of forms and practice peculiarly fitted him to take the lead in the new and improved order of things. How fully publick expectation has been satisfied, I need not declare. The reformed state of the dockets throughout the commonwealth, the promptness of decisions, the regularity of trials, attest the beneficial effects of a system, which he has done so much to render popular and permanent.

If to some respectable and eminent men he at times appeared precipitate, in his nisi prius opinions, I am sure they will admit that he of all men had the most right to decide promptly, and that the rectitude of his decisions generally justified their apparent haste.

On this subject I would also remark, that in the course of thirty-five years practice almost every subject of legal inquiry had passed in review before his mind; that his memory, the most distinguished of all his great faculties, retained everything he had ever read, and almost everything he had ever heard; and that, thus supplied with principles and precedents, it is not astonishing that great minds, should sometimes be surprised at the suddenness of his opinions, and should be inclined to impute to haste what was the effect of knowledge. He appeared to have an instantaneous perception of the legal merits of a controversy, and to see the beginning, middle and end of a cause with one comprehensive glance. I acknowledge myself among those who have sometimes imputed to precipitancy, what I have afterwards found to be the result of learning and memory.

To have had a depository for the preservation of the learned efforts of so eminent a judge, must be considered fortunate for us and for posterity. The six first volumes of the present series of reports will long endure, as a monument of the technical learning and deep juridical reasonings of the late chief justice. The principles of the common law, relating to real estates, are there clearly and familiarly explained, and most of our important legislative acts have there received constructions consonant to their real, but often obscure, intent. In these books will also be found many important mercantile cases, in which the principles of commercial and marine contracts have been discussed with remarkable clearness, and the law merchant has been fully and satisfactorily explained. Had he been speared to us, as I had always hoped he would be, for a period of ten years of judicial life, the abundant stores of his knowledge would have been thus drawn out for publick use, and his fellow-labourers who survive, and their successors, perhaps for centuries, would have enjoyed the fruits of his studies and experience. But more than two years ago it pleased Heaven to afflict him with a malady, which, though it left his mind unimpaired, rendered corporeal exercise, particularly that of writing, extremely irksome. In this respect only was his usefulness diminished, but the consequence has been a loss to the publick of much of his learning and juridical wisdom.

But he possessed other qualities of a judge, not exposed to the publick eye, but equally important with those which have been mentioned. He was a patient and diligent inquirer after truth, revolving and revising his own opinions, until it was scarcely possible they should not be correct, communicating freely to his brethren his own reasonings, and candidly listening to theirs, suppressing all pride of opinion, and being ready to adopt another’s, instead of his own, if found more conformable to truth, and never being willing to give the sanction of the whole court to a principle, until it had been tested by every method which learning and ingenuity could devise.

The remarkable coincidence of opinion, which appears in our reports, is not more a testimony of his power of enforcing his own, than of his candid estimation of that of others. He was not an arrogant man; for, though he well knew his own powers, he also knew the fallability of all human power, and that no man is so sufficient of himself as to want no assistance from others. The decisions of the court, with the reasons on which they were founded, when digested and committed to writing by him, were submitted to the consideration of his brethren, with a strong desire that they should be criticized and pruned, and he lent a willing ear to suggestions of alteration and improvement.

Though fraught with all the technical learning of the bar, and accustomed to a strict adherence to rules in his own practice, he yet, like Lord Mansfield, was averse from suffering justice to be entangled in the net of forms; and he, therefore, exerted all his ingenuity to support by technical reasoning the principles of equity and right.

In the administration of criminal law, however, he was strict, and almost punctilious, in adhering to forms. He required of the publick prosecutors the most scrupulous exactness, believing it to be the right, even of the guilty, to be tried according to known and practiced rules; and that it was a less evil for a criminal to escape, than that the barriers established for the security of innocence should be overthrown.

He was a humane judge, and adopted, in its fullest extent, the maxim of Lord Chief Justice Hale, that doubts should always be placed in the scale of mercy.

I have thus attempted a sketch of the professional and judicial character of Chief Justice Parsons; but he was always a man belonging to the publick, and his political character requires some attention. I abstain from any observations upon the political doctrines he uniformly espoused, so far as they relate to the administrations of our government, for I wish not to offend the feelings of some who are obliged to hear, and who, probably, differ from him, and from me, upon that subject. I mean only to show what he has done, in order that you may not refuse to join me in ascribing to him the character of a statesman and a patriot. He was always tenaciously attached to home, and unwilling to engage in scenes which drew him from it; so that it was difficult to prevail upon him to take so great a share in publick councils as his townsmen and the people of his county desired.

But on great and solemn occasions, when the commonwealth was organizing, and when it was in jeopardy, he yielded to the impulse of patriotism and the solicitations of his neighbours, and gave his time and talents to the state. Accordingly in 1779 he became a member of the convention which deliberated upon and formed the frame of state government, which has so happily continued, in spite of the many rude shocks it has received, to the present day. At a time when the people had freed themselves from a government which had become tyrannical, when they were held together as a body politick by a sense of danger rather than by the restraints of law, and when an enthusiastic love of liberty was universally felt, so that the rigours of a bad government would naturally excite jealousy of any which should be proposed, it was no easy task to introduce into the compact vigour enough to prolong its existence beyond the time of peril, which seemed to supersede the necessity of all government.

There were great and amiable men in that convention, so enraptured with the view of order, discipline and regard to right, spontaneously existing without coercive power, that they in some measure lost sight of the lessons of history, and concluded that the people would always remain wise and virtuous, and that the most lax system of government for such a people was the best. There were others equally attached to true liberty, but less ardent in their feelings, who believed, that man was in all ages, and in almost all places, the same; a being of many virtues and many vices, thoughtful and moderate in adversity, rash and presumptuous in prosperity, and at all times requiring the strong arm of government and law to repress his passions, and restrain his propensity to errour.

In the latter class was Parsons; and he was indefatigable in his exertions to obtain as energetic a system as the people would bear, and to introduce into it those checks and balances which would ensure its durability. I have the authority of contemporary statesmen for declaring, that, among these wise men and patriots, Parsons, at that time not thirty years old, discovered an intelligence, strength of mind, and force of reasoning, which gave him a decided influence in that venerable assembly. Many of the most important articles of the constitution were of his draught, and those provisions which were most essential, though least palatable, such as dignity and power to the executive, independence to the judiciary, and a separation of the branches of the legislative department, were supported by him with all the power of argument and eloquence, which could be derived from deep historical information and wise reflections upon the nature and character of mankind. Wherever he was placed, his influence was immediately felt, and his assiduity and patience of investigation, added to his ability to enforce his opinions, put him in the front rank in all arduous and anxious conflicts. (d)

After this constitution had been adopted by the people, and had gone into operation, he appeared but seldom in the political assemblies of the state. The ordinary business of legislation was not of importance enough in his mind to draw him from a profitable pursuit of his profession, which was necessary for the support and education of an increasing family. Yet when the seeds of disorder sprang up in the community, and the most dangerous principles of disorganization had begun to spread, he was again prevailed upon to take a seat in the legislature, where his great political knowledge, and his peculiar address, contributed largely to the preservation of that constitution he had done so much to establish.

But another great national revolution occurred. The constitution of the United States was presented to the people for their approbation, and a convention of delegates from the several towns in this commonwealth was assembled to discuss its merits, and adopt or reject it. This was the crisis of life or death to the union of the states, and ruin or prosperity hung upon the decision. Parsons again appeared in the cause of order, law and government, the cause indeed of the people, though they did not recognize it; for no doubt was entertained that, at the first meeting of that convention, a great majority of its members were predetermined to reject the constitution. I, then a young man, was an anxious spectator of these doings. I heard there the captivating eloquence of Ames, the polished erudition of King, the ardent and pathetic appeals of Dana, the sagacious and conciliating remarks of Strong, and the arguments of other eminent men of that body. But Parsons to me appeared the master spirit of that assembly. Upon all sudden emergencies, and upon plausible and unexpected objections, he was the centinel to guard the patriot camp, and to prevent confusion from unexpected assault. He labored there in season and out of season, the whole energies of his mind being bent upon the successful issue of a question which was, he believed, to determine the fate of his country. This finished his political engagements, except some few years in the legislature at subsequent periods, when his influence was visible, but the subjects which occurred only of ordinary import.

But though he was only occasionally engaged as a member of the legislature, he yet was an active observer of publick measures, and without doubt contributed his councils in many of the arrangements which took place. His political friends frequently sought his advice, and they always found him perfectly acquainted with passing events and ready to communicate his opinions.

More has been imputed to him on the score of political influence than was true. By those who felt the weight of his character, without enjoying his confidence, it was believed, or at least asserted, that he dictated most of the measures which his political friends adopted. From seven years most intimate and confidential intercourse with him, I can testify, that his influence has not been exerted during that period in projecting publick measures, that it appeared only in giving advice when solicited for it, and that if his opinions were adopted, it was not from any authority claimed by him or submitted to by others, but because they were deemed wise and beneficial.

He was undoubtedly a bold politician, and on any interesting crisis his system was to take the ground which he thought was right, and maintain it without regard to the difficulties to be encountered, and especially never to be deterred by fear of unpopularity. This sometimes led even his friends to think that his political courage partook of temerity, and that he overlooked expediency in pursuit of right; but it not unfrequently happened, that the difference between them was owing to his greater share of political foresight, or to his instantaneous perception of what the times and circumstances required.

In his political, as well as in his judicial character, there was an apparent suddenness of opinion, which at the moment seemed precipitancy, but which has in most instances been discovered to be the effect of a process of reasoning astonishingly rapid, or the immediate decision of judgment upon fact and principles stored in his memory and always ready for use. Instances could be adduced, in which his friends have rejected his opinions, from a doubt of their correctness, and yet have been necessarily brought, by the course of events which he had the sagacity to foresee, to the very point from which they had prudently, as they thought, receded.

I add, that I most sincerely believe that he had no private or personal views to gratify, and that his sole object was the permanent interest and prosperity of his country.

You will spare me a few moments, while I briefly exhibit to you the private character of this distinguished man. He was just, regular and punctual in all his transactions. Simplicity and order presided over his household; hospitality, without ostentation or ceremony, reigned within his mansion. Domestick tranquility and cheerfulness beamed from his countenance, and was reflected back upon him from his happy and delighted family. It has been the misfortune of many, if not most of those, who have been devoted to literature, and who have attained great celebrity, to have been so much absorbed in grave contemplations as to acquire a distaste to those charities of life which are the sources of its happiness, or to become insensible to the ordinary excitements to recreation and pleasure. It was not so with Parsons. He was great even in common affairs. His conversation could instruct or amuse, as times and seasons suited. Neither philosophers nor children could leave his society without being improved or entertained. Amid the multifarious occupations of his mind in business and scientific pursuits, he had still found room for all the lighter literature, and was ready with his critique even upon the ephemeral works of fancy and of taste. The more solid productions of polite literature had passed the ordeal of his judgment, so that his materials for social converse were abundant, and his power of using them unlimited. Indeed, his memory may be considered a capacious store house, separated into an infinite number of apartments, in which principles, facts and anecdotes were laid up according to their classes, marked and numbered, so that he could draw them out and appropriate them whenever occasion offered, without confusion or misapplication. His conversation was illumined with flashes of wit and merriment, which captivated his hearers, and rendered him at the same time the most edifying and the most entertaining of companions. He was accessible, familiar and communicative, never morose or ill-natured, a patron of literature and literary men, a warm friend to the clergy and to the institutions of religion and learning, and a most ardent admirer and promoter of merit among the young. (e) He was not an avaricious man, for, after a long life of labour in a lucrative profession, with as much opportunity as was ever enjoyed to amass riches, he has left no greater estate, than is frequently accumulated by a prudent and respectable tradesman.

The man whom he most resembled in powers of mind could be brilliant and astonishing, when surrounded by kindred spirits, and spurred on to intellectual conflicts; but when the tournament was over, he retired with exhausted spirits and debilitated mind, and sunk into the gloom of superstition and the horrours of self-condemnation. But Parsons could leave the theological controversy, the mathematical problem, or the legal inquiry, and enter, at once, with spirit and interest into domestick conversation, and even into children’s sports. When fatigued with the labour of deep legal research, or exhausted by a continued train of thought upon one subject, it was not uncommon for him to relax his mind with some abstruse arithmetical or geometrical demonstration, or to turn over the pages of some popular and interesting novel. And, strange as it may seem, it is true, that, from his earliest years to the latter season of his life, these two sources of amusement were constantly enjoyed by him. (f)

I know that I am in danger of being thought so infatuated with admiration, as to exaggerate his talents, or at least to give them too high a colouring. But death has destroyed all motives for flattery, if any could have existed, and a month’s interval has given opportunity to reflect upon the folly of overstrained praise. I confess, the more I contemplate his character, the more I revere it. To some of its strongest points I consider myself a witness, and should disdain to pass beyond the limits of truth. In relation to his professional and publick judicial character, I speak in the presence of men, who are witnesses as well as myself. As to his classical and literary acquirements I profess not to judge, except from the testimony of those best qualified to decide. I can appeal with confidence to the learned and reverend governours of our university, who for more than ten years have enjoyed the benefit of his counsels, and witnessed the depth of his learning. For his mathematical and philosophical eminence, I could summon the chosen professors of those branches, and I could add to them the modest and scientific Bowditch. (g) For his knowledge in astronomy, mechanicks, chemistry and electricity I would venture to call the most distinguished masters we have in those several branches, and I believe the testimony from each witness would be, that Parsons was great in each particular department.

Should anyone ask, had this great man no faults, no foibles? I answer, he had, for he was a man—but none which ought to enter into a candid estimation of his character. I leave them to those who are hardy enough to violate the sanctity of the tomb for the purpose of magnifying and exposing them.

That such a man as this, whose mind had never been at rest, and whose body had seldom been in exercise, should have lived to the age of sixty three, is rather a matter of astonishment, than that he should then have died.

At this distance from the period of his death, when the first painful sensations at so great a loss have subsided, it is not unsuitable to take consolation from the possible, if not probable consequences of a prolonged life. Beyond the age at which he had arrived, I do not know, that an instance exists of an improvement of the faculties of the mind, but many present themselves of deplorable decay, and humiliating debility. An opposite example exists in the case of that venerable Judge Trowbridge, whom I have had occasion to mention before in this address. The last twenty years of his life passed in almost entire forgetfulness of and by the world. Should it not be considered a happy, rather than a lamentable event, to escape the infirmities, the disabilities, and perhaps the neglects of a protracted old age? Parsons died in the zenith of his reputation, in the strength of his understanding; and so dying, has left a legacy to his children and to the publick, in his character, more valuable than exhaustless riches.

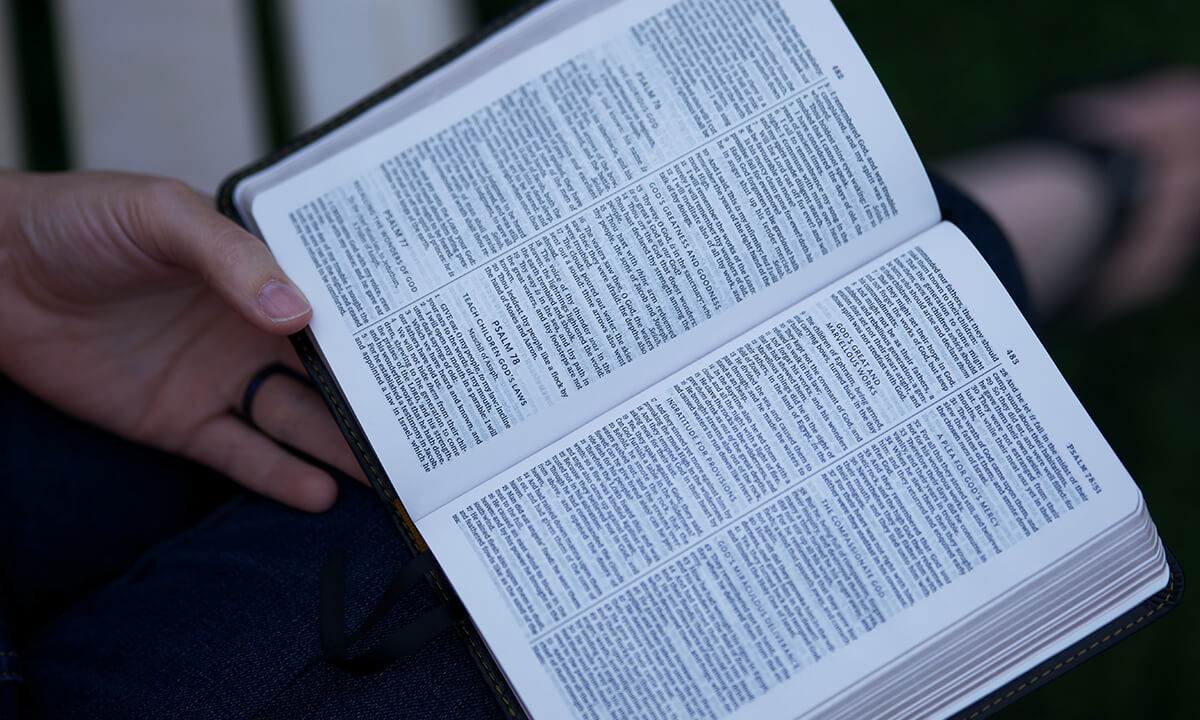

The testimony he bore, too, to the truth of the Christian revelation should furnish a consolation for his death. It was the testimony of a most exalted human intellect, unclouded by the apprehensions of death, and unobscured by superstition. It was declared repeatedly in the best state of his health, and confirmed in the serene contemplation of his expected change. It was the result of a trial of witnesses, in which professional acuteness was aided by native powers of discrimination. He has left written evidence of the conclusion his penetrating mind had formed upon this all interesting inquiry. It may seem unbecoming in a Christian to place much reliance upon human authority for his hopes of immortality and happiness. But a great portion of the world is governed by authority, and when some few great men have published their skepticism, and thus given confidence to the infidel of inferior understanding, it is comforting to the sincere and humble believer, to be able to add the name of Parsons to the long list of great and good men, who have given their living and dying testimony to the religion they profess. (h)

May the life and celebrity of this great man stimulate the young to diligence and perseverance in their studies, so that, at some future time, one may rise up from among them fit to supply his place in publick estimation.

May his pre-eminent qualifications for the judicial magistracy, which cannot be reached by his fellow labourers, incite them to greater zeal, labour and attention, so that the chasm made by his death may be the less observed. And may his departure impress us all with solemn and suitable reflections upon the vanity of all human attainments, compared with that wisdom which cometh from above, whose ways are pleasantness, and whose end is everlasting life.

NOTES.

(a) The following facts were communicated to me by the Hon. D. A. Tyng.

During the late visit of Fr. Ad. Vanderkemp, Esq. formerly of Leyden, but for many years past resident in the State of New York, I had the satisfaction of introducing him to our late excellent Chief Justice, and of witnessing a very interesting conversation between these two learned men on various topicks of literature. After we left the Chief Justice’s house, Mr. V. said to me, that he had been much gratified with the interview, for which he had felt a strong desire, and particularly from a circumstance which he then related.

Some years since Mr. V. received a letter from the late Mr. John Luzac, professor of the Greek language, &c. in the university of Leyden, who was the relative and intimate friend and correspondent of Mr. V. and confessedly the first Greek scholar of his day in Europe; in which letter Mr. Luzac inquired of Mr. Vanderkemp, whether he had made an acquaintance with a Mr. Parsons of Boston, of whom he had heard that he was called in America “the Giant of the law.”—How well Mr. Parsons might be entitled to this appellation, Mr. Luzac said he could not judge; but he could of his own knowledge affirm that he was “a giant in Greek Criticism.”

Professor Luzac’s opinion was founded on a correspondence he held with the Chief Justice many years ago, occasioned by the latter sending to Amsterdam for some rare editions of Greek authors which could not be obtained then, either in this country or England.

At College he was an excellent scholar in Greek and Latin. But he began the study of Greek again after he was 40 years old, when his eldest son was fitting for college.

(b) So great was his reputation as a lawyer, that, upon his removal from Newburyport to Boston, it was customary for merchants of distinction, who had some unavoidable dispute, to make out a statement of the facts, and submit them to his decision, and in this way many important commercial questions have been settled, without incurring the expense or delay of a lawsuit.

(c) The assertion, that Chief Justice Parsons would probably have been made Lord Chancellor or Lord Chief Justice in England had he lived there, will probably be considered extravagant by those who are in the habit of magnifying objects in proportion to their distance. But from a comparison of him with Lords Mansfield, Kenyon, Ellenborough, Eldon and Erskine, as they appear in books, and from the opinion of several gentlemen, who have seen most of those dignitaries in the exercise of their high functions, I have little doubt that such would have been his destiny, and none that he would have merited it.

(d) It is not generally known, that before this convention of the people by their delegates was called for the purpose of making a constitution, the existing government, which was exercised by a convention, in the year 1777, drew up the form of a constitution, and presented it to the people for their acceptance. This appeared to some gentlemen in the county of Essex so loose and inefficient in its texture, that they urged a representation of their towns in a county convention, which accordingly met in 1778 at Ipswich. Parsons was one of this convention. They agreed to advise the towns to reject the constitution, which had been proposed. A committee of this county convention was appointed to take into consideration the proposed constitution, and report thereon. Parsons was upon this committee. The report is undoubtedly his, though he was probably aided by others, at least with their advice. This elaborate report is called the Essex Result; and it contains an able discussion of the principles of a free republic, and shows clearly the defects of the proffered form of government.

The people rejected the constitution. A convention was called for the express purpose of making another, which was finished and accepted by the people in 1780.

(e) The zealous attention of the Chief Justice to the interests of the college, while he was a member of the corporation, was generally known. But his care for the interests of literature was in other ways exemplified. He had been for three years one of the supervisory committee of a Grammar School, kept by Mr. Clap in this town. I have attended the examinations of the scholars, at all of which the Chief Justice was present. He generally took the lead in the examination, and discovered such a critical knowledge of the Greek and Latin languages as surprised everybody.

His presence was useful in other respects, for he so interested and amused the boys with anecdotes concerning the men and the times about which they were reading, as to render their examinations pleasant, instead of being formidable to them.

(f) Judge Tudor, who was a class-mate of the Chief Justice in college, and in the college phrase, his chum, has frequently told me, that after the usual exercises, Parsons was in the habit of taking his slate and amusing himself with some deep mathematical calculation, and that he would vary his recreation by reading some tale or novel—it seeming indifferent to him, which of these amusements first fell in his way. I have, within the last seven years of his life, found him indulging the same propensity—finding him with his slate and pencil so deeply engaged, that I would not disturb his slate and pencil so deeply engaged, that I would not disturb him for some minutes after my entrance, and not unfrequently as deeply engaged in some modern novel, or other work of fancy.

(g) Mr. Bowditch, in his Practical Navigator, on the subject of Lunar Observations, speaking of a method of correcting the apparent distance of the moon from the sun, says, “it is an improvement on Witchell’s method, and was made in consequence of a suggestion from a gentleman eminently distinguished for his mathematical acquirements;” and by a note referred to in this passage, Chief Justice Parsons is the gentleman alluded to. Mr. Bowditch also received some communications from him on the subject of the Comet, which last made its appearance in our hemisphere, which showed ingenuity and learning.

(h) About three months before the Chief Justice died, I had a conversation with him upon the subject of the Christian religion, and particularly upon the proofs of the resurrection contained in the New Testament. He told me, that he felt the most perfect satisfaction on that subject; that he had once taken it up with a view to ascertain the weight of the evidence by comparing the accounts given by the four evangelists with each other; and that from their agreement in all substantial and important facts, as well as their disagreement in minor circumstances—considering them all as separate and independent witnesses, giving their testimony at different periods, he believed that the evidence would be considered perfect, if the question was tried at any human tribunal. I then did not know that he had made a publick profession of his belief by becoming a member of any church, and I asked him why he had not thus testified his belief. He told me that he had postponed it a great while, because, as the general state of his health, and his fear of exposing himself to the cold and damp air would prevent him from attending publick worship constantly, and as from those causes, he might frequently be absent on communion days, he was apprehensive he might be thought not to act up to his profession; but that two or three years ago, he had made up his mind to do his duty in joining the church, and as much of his duty as he could in attending upon the ordinance—and he accordingly joined the church of which President Kirkland was then the pastor.

A similar conversation was held by him with the Rev. Mr. Thacher during his late sickness, through the whole of which he evinced a patience and resignation, which, considering his extreme nervous irritability and apprehensions of disease, when in his best state of health, can be accounted for only by the enlightened and satisfactory hopes he entertained of a happy immorality. It ought to be highly consolatory to his friends to know, that he whom they had seen to shrink at an eastern breeze, and to start at the slightest pain, should, at the certain approach of the king of terrours, collect all the energies of his wonderful mind, and contemplate his approaching dissolution with as much steadiness and composure, as he would many of the ordinary events of life.

END.

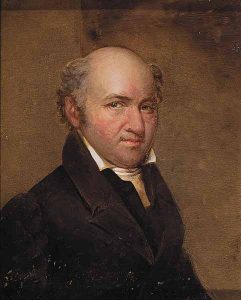

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.