This is a transcript of a sermon commemorating George Washington’s Birthday. It was preached on February 22, 1863 in Connecticut by the pastor of the First Congregational Church, George Richards (1816-1869).

A SERMON

Preached in the

First Congregational Church, Litchfield, Conn.,

February 22, 1863.

By

George Richards.

“In very deed for this cause have I raised thee up, for to show in thee My power and that My name may be declared throughout all the earth.” Exodus ix. 16.

Thus spake Jehovah to the King of Egypt. God attains His own ends by His own instruments. When He has great and important results to bring to pass, He provides means adapted and adequate to their accomplishment.

Very bad men, actuated by very bad motives, may be used to promote the very best designs: Pharaoh was an instance. Very good men, actuated by very good motives, may be made instrumental of benefits far transcending their most sanguine expectations: Washington was an instance.

A hundred and thirty-one years ago today, in an ancient homestead in Virginia near the banks of the Potomac, was born the child destined to be looked up to by all parties and sections with singular unanimity as the father and founder of his country- the one man whose preeminent worth and unexampled services are deemed beyond dispute- the most discordant opinions claiming his sanction and seeking the shelter of his authority- war itself sheathing its sword and keeping truce about his sepulcher.

Do we not well at a time like this, when dissension and division are the order of the day, to recall (though [now] on the Sabbath and in the sanctuary) what manner of man he was, how Providence had endowed and disciplined him for his diversified trusts, and with what signal success he acquitted himself of so overwhelming responsibilities?

I. Look first at the original constitution of the man. He Who had so much for him to do, framed him accordingly. He was cast, body and mind, in a capacious mould. Great qualities rarely found single were grouped in him. Traits generally thought conflicting were harmonized in him.

Though it would hardly have been suspected from his accustomed equanimity, he was a man of strong passions and impetuous impulses. In rare instances, the pent up elements found vent and terrible was the explosion. Had he possessed the mild and placid temper commonly ascribed to him, he would have lacked the force essential to the difficult task assigned him. The surface was usually cold and still (and needed to be) but the volcanic fires slumbered within.

United to these passions and impulses was a will competent to restrain them. He governed others by first governing himself. Only those admitted to his privacy, who saw him when under the least restraint, were aware with how tight a rein he held himself in check. He had made up his mind to be his own master, and seldom was his vigilance off its guard or his authority successfully disputed.

Conjoined to those antagonist forces was a judgment as sound, as fair, as even-balanced as often falls to the lot of man. Glad of light from any quarter, patient to hear and weigh contradictory opinions, slow to arrive at a decision, watchful against the bias of pride, prejudice, self-interest, his conclusions, perhaps, were as nearly infallible as can be expected of mere human reason.

He was a man, too, of minute detail keeping his own accounts, private and public, in the neatest of handwritings, and with a sort of microscopic accuracy; amid his busiest campaigns superintending his estates, instructing his stewards, regulating the routine of crops, caring for the stock, the dairy, the fences, the tools, as if nothing were small enough to escape him; and yet, withal, how broad and comprehensive were his views, embracing the entire country in all its departments- the army to be recruited, fed, clothed, equipped, drilled; its movements skillfully and deliberately planned- Congress to be respectfully addressed and begged and importuned to vote the requisite supplies- the States to be kept in harmony and urged each to its proportionate exertions- foreign nations to be conciliated and bound by treaty stipulations! What had he not upon his hands? Yet the less never seemed to encroach upon the greater, nor the greater upon the less. The compass and variety of his faculties rendered him competent to all. In such large dimensions and symmetrical proportions had his Creator constituted him.

II. Again, the early training of Washington singularly fitted him for the two diverse spheres he was ordained to occupy. As he was to be alike conspicuous and important as a soldier and civilian, the Providence which designed him for both and educated him for both.

His ancestry, which can be traced back to the century succeeding the Norman conquest, boasted its mail-clad warriors and gallant knights. His great-grandfather who removed to this country was a Colonel of the Virginia forces which he led against the Indians that ravaged the Potomac settlements. The elder brother of George, his guardian and instructor, was a captain in his majesty’s service and distinguished for his valor.

Mount Vernon was a resort of British officers, both of the army and navy, where feats of arms were discussed and famous victories exulted over. The little lad, all ears, lost nothing and went out among the boys to tell and show how fields were won. When the French war was imminent, and the youth of nineteen was commissioned an Adjutant-General, one of these veteran campaigners lent him treatises on military tactics, put him through the manual exercise, and gave him an idea of field evolutions, while another was his instructor in the sword exercise. His arduous and honorable service against the French and their savage allies (first in subordinate positions then as Commander-in-Chief of the Virginia forces) was the best preparation possible for the still more harassing and eventful trust in due time to be devolved on him.

It would seem as if the most intricate problems of the Revolutionary struggle had been worked out on a smaller scale in this preliminary contest. The mother country was unwittingly training under her own flag the master spirit who was to emancipate his countrymen from her iron thrall. She “meant not so, neither did her heart think so” [Isaiah 10:7] but so had a Higher Will ordained.

In like manner was the same youth “under tutors and governor” [Galatians 4:2] who educated him for his civil functions.

His first ancestor in this country was not only a military leader but a member of the House of Burgesses.

So, too, the elder brother already spoken of. At the age of twenty-six, Washington himself was elected by a large majority against formidable competitors to a seat in that dignified and influential body where his calm and wise but resolute and independent spirit helped to direct and develop the growing opposition to the tyranny of king and parliament.

When the first Continental Congress met at Philadelphia- an assembly which for weight of character and consummate sagacity has rarely been equaled- Washington was one of the delegates appointed from Virginia. How well he acted his part in that grave conclave let his colleague, Patrick Henry, testify. Asked on his return whom he considered the greatest man in Congress, he said: “If you speak of eloquence, Mr. Rutledge, of South Carolina, is by far the greatest orator;” (he might have excepted himself); “but if you speak of solid information and sound judgment, Colonel Washington is, unquestioningly, the greatest man on the floor.” As when he was elevated to the command of our armies, he was found no novice but marvelously disciplined and equipped for the arduous post assigned him; so when he was summoned to the chair of Chief Magistrate with no usages nor precedents to guide, his extraordinary fitness for the position was no sudden inspiration, but the ripe result of this preparatory training to which the same far-seeing Providence had been subjecting him.

III. Another rare combination characterized this man.

By birth and social position he belonged to the aristocracy. Even in the mother country his family ranked with the privileged class. Transplanted to the “Old Dominion,” they at once became extensive landholders and were elevated to prominent positions under the Crown. Among his earlier associates were the Fairfaxes, of noble blood who, initiated into the mysterious of high life in England, brought with them its refined graces and courtly manners to their new homes between the Potomac and Rappahannock.

Bred in so favorable a school, an apt and ready pupil, the young Virginian soon became the model of a gentleman.

He inherited a competent property from his father to which he added largely by his marriage and by his judicious management of his affairs; and thus, to a noble person and dignified address, joined the wealth which in that day and neighborhood peculiarly greatly enhanced his personal and social consequence. Few men, probably, of his time enjoyed as unrestricted access to the stateliest mansions and selectest society of the most aristocratic of the Colonies. But where was there one more thoroughly superior to the narrow and selfish pride so apt to attend high social position? If he felt it, he fought against it and manfully subdued it. He was preeminently a man of the people, entered into their wants, divided their burdens, made their interests his interests, and in every way identified himself with their prosperity and adversity.

Naturally and by habit reserved and distant – never stooping to flatter and fawn around the multitude – to buy their suffrages by palliating their faults and conniving at and participating in their vices – he stood up for their rights against whoever would encroach upon them, took part in their toils and trials, as if their lot had been his, told them the honest truth about themselves (reluctant as they might be to hear it), animated them to duty by bearing the lion’s share of it –was, in a word, the direct opposite of the timid, groveling, time-serving, self-seeking demagogue of which there were not wanting examples then, as there have not been since. When the French and Indians were prowling round the defenseless settlements and all eyes were turned to him who was without men, arms, supplies, how touchingly does he appeal to the royal Governor: “The supplicating tears of the women and moving petitions of the men melt me into such deadly sorrow that I solemnly declare (if I know my own mind), I could offer myself a willing sacrifice to the butchering enemy provided that would contribute to the people’s ease!” His deeds confirmed his words! So, after this barbarous struggle was ended and the subordinate officers and soldiers failed to obtain the bounty lands promised them, he became their champion – started off on horseback into the wilderness not yet secure, confronted the warriors he had lately fought (one aged sachem telling them that he and his young braves had singled him out at Braddock’s defeat, and fired at him over and over but that the Great Spirit must have protected him), and at length, at the mouth of the Great Kanawha, turning to account his skill as a surveyor, he affixed his mark to the lands which he succeeded in securing to his valiant comrades.

Still later, when the Stamp Act was passed and foreign luxuries must be dispensed with or an odious impost paid to an oppressive government, he appealed to his rich neighbors to unite with him in discarding such indulgencies and thus befriend their country. The articles proscribed he would not admit into his house and enjoined his agent in London to ship nothing while subject to taxation.

“Our all,” said he, “is at stake; and the little conveniences and comforts of life, when set in competition with our liberty, ought to be rejected- not with reluctance, but with pleasure.”

And afterward when he left his noble mansion on the Potomac, replete with every reasonable indulgence that affluence would furnish to encounter the hardships and exposures of camp life- though great pecuniary interests needed his personal supervision, and languished for the lack of them – though the humblest common soldier underwent not a tithe of the anxiety and mental agony which the long-doubtful contest imposed on him- still, he expressly stipulated that only his expenses should be paid, which he exactly recorded, unwilling to accept a farthing of recompense from his bleeding and impoverished country.

How in contrast with the greedy speculator in office and out of it who have prowled like famished wolves round our field of carnage – stealing everything they could lay their hands on – robbing the national treasury – purloining from the camp chest – pilfering from the wounded in the hospitals – appropriating to themselves the little comforts meant for the dying, if not stripping the very dead!

Yes! Washington, though an accomplished gentleman, was more; he was a man. He respected humanity under whatever guise or garb. He went for his country – his whole country – without distinction; not for the elect few among whom the accident of his birth of fortune had cast his lot, but for the entire people to whose destiny, for weal or woe, an all-disposing Providence had linked his own.

IV. Another union of opposites in this man was Southern birth and training with Northern sentiments and preferences.

Northern men with Southern principles abound: Washington was the reverse, rather.

His sterling common sense, his patient industry, his thorough system, his close personal application to business, his economy amid affluence and temperance amid abundance, his habitual gravity and self control- qualities and habits not too frequent anywhere- are not held to be peculiarly indigenous to the Sunny South.

They are more usually the product of a colder clime, a harder soil, and very different institutions.

And who proposed Washington as the commander of our armies? John Adams- more than one of the Virginia delegates being cool on the subject, and one, clear and full against it. Repairing to headquarters, the new chief found himself at the head of a host, nearly every man at that time from East of Hudson. How well he served and how thoroughly he won their respectful confidence need not be told. The general from one section of the country- the subordinate officers and rank and file from another- how creditable to both was their hearty cooperation! There were not wanting among so many jealousies, suspicions, animosities; but an unrivaled prudence joined to a lofty magnanimity managed to surmount them. The army for awhile was little better than a rabble, hurried together from every quarter to maintain the common cause, and at times their leader must have been utterly out of patience with them; yet for the most part, he smothered his dissatisfaction and made the best of it. “This unhappy and devoted province,” he kindly said, “has been so long in a state of anarchy, and the yoke has been laid so heavily upon it, that great allowances are to be made for troops raised under such circumstances. The deficiency of numbers, discipline, and stores can only lead to this conclusion; that their spirit has exceeded their strength.” After this rude militia- profiting by his stern but friendly discipline- had driven the British veterans, ships, and men out of the Port of Boston, never more to reestablish themselves on the soil or in the harbors of New England, to whom still did the commander-in-chief look for troops and supplies with a more unwavering assurance than to Governor Trumbull of Connecticut? In whose military skill and genius did he repose higher confidence than in those of General Green of Rhode Island?

So when later he filled the Presidential chair, who were his most confidential advisers? On whom did he more implicitly rely to give shape and direction to his policy than on Adams, Jay, and Hamilton?

Could he discern no good beyond his immediate section? Did he take it upon him to berate the bigoted, narrow-minded, puritanical spirit?

No! He left it to men born on this Eastern soil to traduce their own fathers’ memories and spit on their own mothers’ graves!

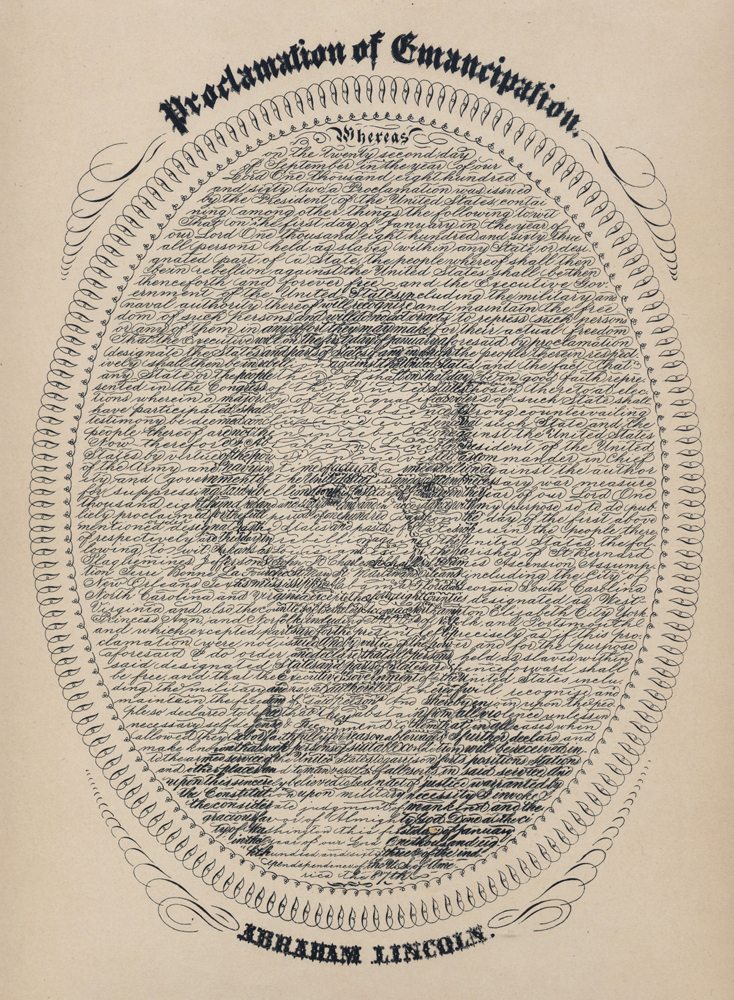

In yet another respect was he less a Southern man than a Northern: he was profoundly averse to slavery. How could he fail to be? He fought through the Revolutionary War under the declaration that “all men are created equal and endowed with certain inalienable rights, among which is liberty.” That declaration- penned by another Virginian statesman, adopted by the Congress from which he received his commission, formally endorsed by every state- he had ordered to be read at the head of every brigade that all might know what he and they were fighting for.

Was he the man lightly to retract his words, or to say one thing, meaning another? Three years after the war he wrote: “I never mean, unless some particular circumstances should compel me to it, to possess another slave by purchase, it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by which slavery in this country may be abolished by law.” Eleven years later he writes; “I wish from my soul, that the legislature of this state could see the policy of a gradual abolition of slavery. It might prevent much future mischief.” Resolved to do his part, at any rate, whoever neglected theirs, the third item in his will reads: “Upon the decease of my wife, it is my will and desire that all the slaves which I hold in my own right shall receive their freedom. To emancipate them during her life, though earnestly desired by me, would be attended with insuperable difficulties.” After providing for the aged and infirm and children, and for the instruction in reading and writing of the apprentices, he continues; “I do hereby expressly forbid the sale or transportation out of the said commonwealth of any slave I may die possessed of, under any pretence whatsoever. And I do moreover most pointedly and most solemnly enjoin it upon my executors hereafter named, or the survivors of them, to see that this clause respecting slaves, and every part thereof, be religiously fulfilled at the epoch at which it is directed to take place, without evasion, neglect, or delay after the crops which may then be on the ground are harvested.”

Suppose every other Virginia planter had refused to traffic in human beings! Suppose every other Southern master, when going up to appear before God, had struck the shackles from every bondman in his charge; how changed would have been the aspect of things today!

“The future mischief” which this seer so anxiously anticipated and so emphatically predicted has befallen us.

V. One other rare combination distinguished Washington. He was a man of the world, and a man of God.

A man of the world- not in the sense of a worldly man, but of a man familiarly versed in human affairs, liberally endowed with what men at large admire; talents, wealth, social position, power, fame- who excelled in nearly everything which most men value and aspire after.

United with this (if we may judge from the testimony of his associates, the tenor of his writings, his public policy, his private conduct) he was a religious man. “Tradition asserts that his widowed mother gathered daily her young household about her and read to them lessons of religion and morality out of some standard word, her favorite volume being Sir Matthew Hale’s Contemplations, Moral and Divine. This mother’s manual- her name inscribed in it by her own pen- was preserved by her son with filial care, and may yet be seen in the library at Mount Vernon.”

While yet a lad he drew up a code of morals and manners, extremely minute and circumstantial, still shown in his handwriting, to which he studied to conform himself. “In his camp on the Great Meadows, he was wont to assemble his half-equipped soldiers, the leather-clad hunters and woodsmen, the painted savages with their wives and children to public prayers, uniting them in solemn devotion by his own example and demeanor.”

A stated communicant in the Episcopal Church (though not cramped by denominational restriction), he entered on and went through the war constantly acknowledging his dependence upon God and looking and pointing others to the one Source of light and strength.

In reply to the acclamations which greeted his arrival at Cambridge, he observed: “That his country had called him to active and dangerous duty but he trusted that Divine Providence, which wisely orders the affairs of men, would enable him to discharge it with fidelity and success.”

In his parting address to his comrades in arms he says: “May the choicest of Heaven’s favors, both here and hereafter, attend those who, under the Divine auspices, have secured innumerable blessings for others.”

Amid the festivities that celebrated his accession to the Presidency, his language was: “When I contemplate the interposition of Providence as it was visibly manifested in guiding us through the Revolution, in preparing us for the reception of the general government, and in conciliating the good will of the people of America toward one another after its adoption, I feel oppressed and almost overwhelmed with Divine munificence.”

And his Farewell words to his countrymen deserve to be embalmed in every heart: “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, – these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

He met death in his chamber with the same unruffled serenity with which he had often braved it in the forefront of battle. “I die hard,” said he, “but I am not afraid to go.”

A few questions will conclude.

1. May we not hope that a land thus signally favored of Providence will yet be spared?

Did God raise up, qualify, commission, so august a character as Washington – enable him to conduct us though the fire and blood of an eight years’ war, to preside over the organization of a government on the whole so wise and equal, to be himself its first Chief Magistrate, exemplifying every civic virtue in his policy and person – and all that within the space of fourscore years (the ripe life time of a man) the whole experiment should come to naught?

It is not probable. We are warranted to believe otherwise.

2. Should not our public men copy after this pattern of true patriotism?

Washington aimed to unite his countrymen, not to divide them- to promote deference to duly constituted authority not to undermine and overturn it. He was often dissatisfied with the course pursued by Congress – felt that they were slow – that they did not fully realize the danger of their country – that sinister and selfish ends actuated too many of them; but he did not for that reason counsel anarchy – he would be no fomenter of civil strife; it was enough to be at war with a foreign foe without cutting one another’s throats.

When the popular discontent broke out in open insurrection he was for prompt and decisive measures to suppress it. “You talk,” writes he, “of employing influence to appease the present tumults. Influence is not government. Let us have a government by which our lives, liberties, and properties will be secured; or let us know the worst at once.”

While one man’s vote counts equal to another’s, not so with opinions. There are leaders in all communities. They who bear such sway over their fellows should use it for good. First to deceive the masses, then to rouse their evil passions- goading them on to acts of violence- is to stir up a tempest much easier raised than regulated; it may be another man’s house burned over him today, and yours over you tomorrow.

The guillotine- to which Robespierre had condemned so many- spouted with his own blood at length. God forbid that the Jacobinism that transformed Paris into a slaughterhouse should redden our streets with gore, or that the fatal experiment of South Carolina should be repeated in Connecticut!

3. Ought the cost of this war, in treasure or life, to dishearten us?

There were times in the Revolution when the stoutest hearts seemed failing them for fear. The heroic leader himself was openly denounced as unfit for his position. Cabals were organized- plots fomented to oust him from his place. Such a waste of men and means, and so meager a return; so many defeats; so few, if any, victories, must no longer be tolerated, said these agitators. Schemers, like Belial,

“All false and hollow, through his tongue Dropp’d manna, and could make the worse appear the better reason, to perplex and dash maturest counsels,”

drew round them the restive malcontents – aggravated their uneasiness – intensified their hate – then used them as the poor tools of their own ambition. “The spirit of freedom,” wrote Washington, “which, at the commencement of this contest, would have gladly sacrificed anything to the attainment of its object, has long since subsided and every selfish passion has taken its place. It is not the public but private interest which influences the majority of mankind nor can the Americans any longer boast an exception.” How stinging yet how just a commentary on human nature! But by and by, brilliant triumphs restored heart and hope; the timorous grew brave; the temporizing and vacillating decided.

Why may it not be so again? When, in the good Providence of God, the starry flag shall wave again over Fort Sumter- when the commerce of the Mississippi shall flow, unimpeded, into the Gulf- when the sway of an oligarchy, more reckless and unprincipled than ever ruled in Venice, shall be forever broken- men will wonder they could have been so impatient- wonder that any suffering and sacrifice could have seemed excessive that were necessary to drive from this soil a tyranny hateful to God and man, and which would inevitably have sunk us to political perdition had we not had the firm and unflinching determination to get rid of it at every hazard.

4. Finally, should not our trust be where Washington’s was- in God? Could that handful of colonies, feeble and few- each jealous of the other, and all of each- hope to shake off the yoke, intolerable though it was, of the foremost power of the world? Yes! If God favored it- if it fell within the scope of His beneficent designs. What are weak and strong to Him, “Who weigheth the mountains in scales, and taketh up the isles as a very little thing?” [Isaiah 40:12, 15] If a powerful and independent nation in place of tributary provinces would better subserve His purposes- would more rapidly diffuse light and knowledge- would widen the sway of just and equal laws, the enjoyment of rational liberty, the spread of a pure Christianity- how was the veto of the British king to hinder it? He might darken our coast with fleets, empty upon our shores his Hessian hordes, “He would blow upon them, and they should whither, and the whirlwind take them away as stubble.” [Isaiah 40:24]

Even so in our day, if this land reconstructed will become Immanuel’s land- if its Constitution and laws shall be conformed to the Divine precepts- if the rights acknowledged to belong to all shall be secured to all- if “a republican form of government” guaranteed by the Constitution [Article IV, Section 4] to every portion of this country shall be extended to every portion of it- if the iron heel shall be lifted, which for half a century had trodden down freedom of speech and of the press over half our national area till at length exile or death is the doom of every man who dares to differ from the lords of the lash on the subject of human servitude – in a word, if this semi-slave country is to become a free country- this half-barbarous country a wholly civilized country- if the Gospel which we sent to the Pagan is first to Christianize ourselves then assuredly are nature, Providence, God on our side; and how puerile and impotent will be the efforts of all the myrmidons of despotism, South and North combined, to thwart so sublime a consummation! Methinks the hour foretold by Jefferson has arrived. “We must await,” said he, “with patience, the workings of an overruling Providence, and hope that that is preparing the deliverance of these our suffering brethren. When the measure of their tears shall be full, when their groans shall have involved Heaven itself in darkness, doubtless a God of Justice will awaken to their distress, and by diffusing light and liberality among their oppressors or at length by His exterminating thunder manifest His attention to the things of the world, and that they are not left to the guidance of a blind fatality.”

“God be merciful unto us, and bless us, and cause his face to shine upon us. That Thy way may be known upon earth; Thy saving health among all nations.” [Psalms 67:1-2]

“In the shadow of Thy wings will we make our refuge until these calamities be over past.” [Psalms 57:1]

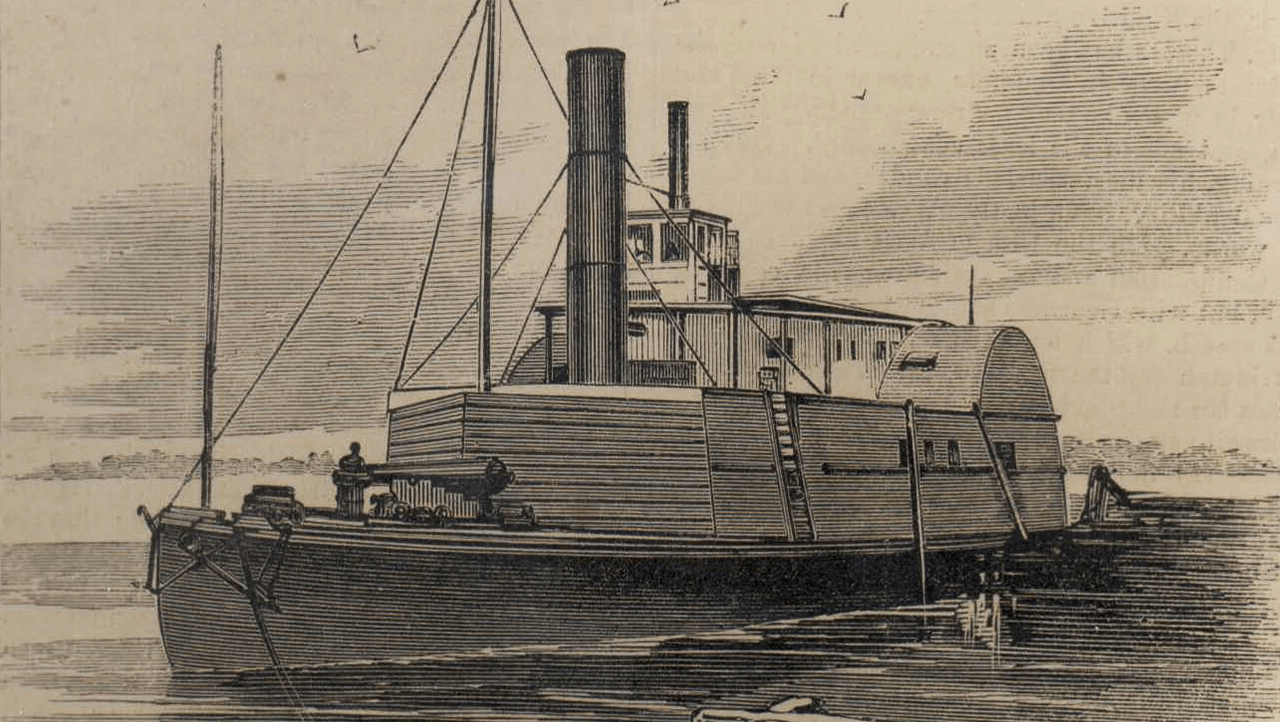

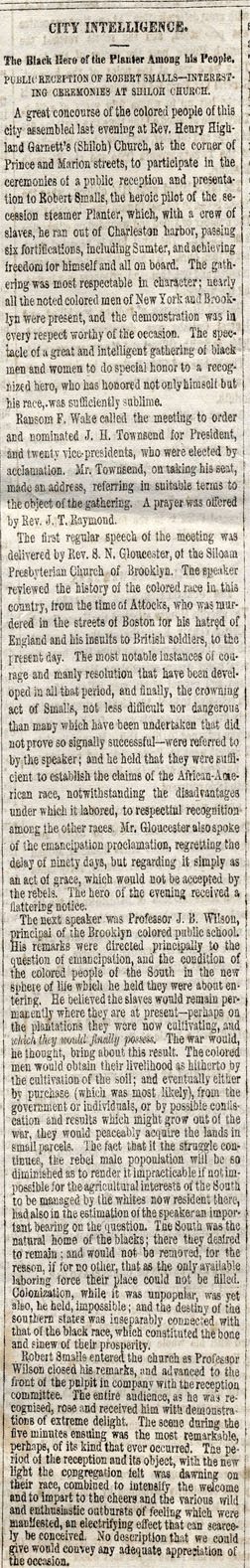

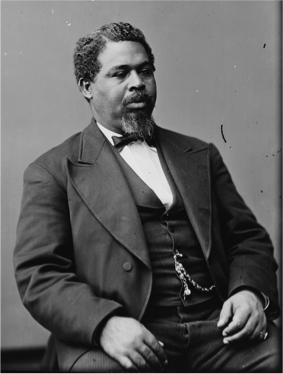

A great concourse of the colored people of this city assembled last evening at Rev. Henry Highland Garnett’s (Shiloh) Church, at the corner of Prince and Marion streets, to participate in the ceremonies of a public reception and presentation to

A great concourse of the colored people of this city assembled last evening at Rev. Henry Highland Garnett’s (Shiloh) Church, at the corner of Prince and Marion streets, to participate in the ceremonies of a public reception and presentation to  The next speaker was Professor J. B. Wilson, principal of the Brooklyn colored public school. His remarks were directed principally to the question of emancipation, and the condition of the colored people of the South in the new sphere of life which he held they were about entering. He believed the slaves would remain permanently where they are at present – perhaps on the plantations they were now cultivating, and which they would finally possess. The war would, he thought, bring about this result. The colored men would obtain their livelihood as hitherto by the cultivation of the soil; and eventually either by purchase (which was most likely), from the government or individuals, or by possible confiscation and results which might grow out of the war, they would peaceably acquire the lands in small parcels. The fact that if the struggle continues, the rebel male population will be so diminished as to render it impracticable if not impossible for the agricultural interests of the South to be managed by the whites now resident there, had also in the estimation of the speaker an important bearing on the question. The South was the natural home of the blacks; there they desired to remain; and would not be removed, for the reason, if for no other, that as the only available laboring force their place could not be filled. Colonization, while it was unpopular, was yet also, he held, impossible; and the destiny of the southern states was inseparably connected with that of the black race, which constituted the bone and sinew of their prosperity.

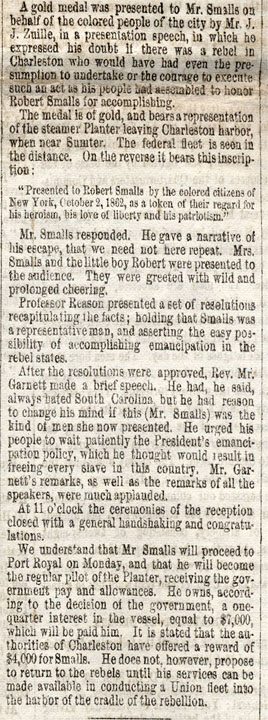

The next speaker was Professor J. B. Wilson, principal of the Brooklyn colored public school. His remarks were directed principally to the question of emancipation, and the condition of the colored people of the South in the new sphere of life which he held they were about entering. He believed the slaves would remain permanently where they are at present – perhaps on the plantations they were now cultivating, and which they would finally possess. The war would, he thought, bring about this result. The colored men would obtain their livelihood as hitherto by the cultivation of the soil; and eventually either by purchase (which was most likely), from the government or individuals, or by possible confiscation and results which might grow out of the war, they would peaceably acquire the lands in small parcels. The fact that if the struggle continues, the rebel male population will be so diminished as to render it impracticable if not impossible for the agricultural interests of the South to be managed by the whites now resident there, had also in the estimation of the speaker an important bearing on the question. The South was the natural home of the blacks; there they desired to remain; and would not be removed, for the reason, if for no other, that as the only available laboring force their place could not be filled. Colonization, while it was unpopular, was yet also, he held, impossible; and the destiny of the southern states was inseparably connected with that of the black race, which constituted the bone and sinew of their prosperity. A gold medal was presented to Mr. Smalls on behalf of the colored people of the city by Mr. J. J. Zuille, in a presentation speech, in which he expressed his doubt if there was a rebel in Charleston, who would have had even the presumption to undertake or the courage to execute such an act as his people has assembled to honor Robert Smalls for accomplishing.

A gold medal was presented to Mr. Smalls on behalf of the colored people of the city by Mr. J. J. Zuille, in a presentation speech, in which he expressed his doubt if there was a rebel in Charleston, who would have had even the presumption to undertake or the courage to execute such an act as his people has assembled to honor Robert Smalls for accomplishing.