These two sermons were preached by George L. Prentiss in 1861 and 1862 on the new year.

Some of the Providential Lessons of 1861.

How to Meet the Events of 1862.

TWO DISCOURSES,

Preached December 29th, 1861, and January 5th, 1862,

By

REV. GEORGE L. PRENTISS, D.D.

SERMON.

PREACHED ON SUNDAY AFTERNOON, DECEMBER 29TH, 1861.

BY REV. GEORGE L. PRENTISS, D.D.,

OF NEW-YORK CITY.

Note.—These discourses are published in the NATIONAL PREACHER AND PRAYER-MEETING for February. Extra copies are printed in this form, and may be had at the office by the dozen or hundred.

SOME OF THE PROVIDENTIAL LESSONS OF 1861.

“I WILL remember the works of the Lord: surely I will remember thy wonders of old. I will meditate also of all thy work, and talk of thy doings. Thy way, O God, is in the sanctuary: who is so great a God as our God! Thou art the God that doest wonders: thou hast declared thy strength among the people.”—Psalm 77:11-14.

The close of the year has always been regarded as a period well adapted to a serious review of life. On reaching it, a thoughtful man will instinctively turn back to consider the path he has been traveling, and the principles which have guided him. It is quite impossible to attain a high degree of personal wisdom and culture without occasional seasons of calm, honest self-inspection; and there is a natural fitness in the closing of the year for such a task. It is a favorable moment, also, for considering the ways of God, and studying those great principles by which he governs the world. I recollect hearing the celebrated Professor Ritter, of Berlin, remark, that if one wished to understand the configuration of the earth, he should begin by going forth into nature, and observing carefully the structure of the hills and plains just about him; he would thus become virtual master of the laws which explain the geography of the globe. The saying is not inapplicable to the course of Providence. He who marks well the manner in which God governs the world for a single year, will have little difficulty in understanding the general principles upon which he has governed it from the beginning, and will continue to govern it to the end of time. “Thy kingdom is an everlasting kingdom, and thy dominion endureth throughout all generations.” There is no caprice, no vacillation in Providence. It is the same yesterday, to-day, and forever. Although as free and it is almighty, both its freedom and its power are immutable. Its methods may and do differ; some of them being plain to every eye, while others are exceedingly involved and obscure, baffling human insight; but its principles and end never change; and they are always most wise, just, beneficent, and true. Like the roots of the everlasting hills, a part of God’s designs may be deep out of sight; but like the summit and massive sides of those same hills, seen under a clear sky, how distinct, grand and substantial are oftentimes the visible parts! As we contemplate them, how they seem to lift us to the very heavens and to inspire us with the consciousness of a strength and repose immovable like their own!

Let us spend a few moments, then, in looking back over the year on whose outermost verge we now stand, and gathering up some of the lessons which it so impressively teaches us. I say us; for although its events, I do not doubt, are intended for the ultimate instruction of mankind, we are the party principally concerned with them at present. Foreigners and foreign nations may be prepared to understand their import by and by; we see that they are not at all prepared now. It is a domestic, American trouble; we are the chief actors and the chief sufferers; and whatever the issue, whether good or bad, ours will be the immediate gain or loss. What the next year may bring forth, we can not tell; the circle of trouble may be so widened as to reach the Old World and involve other nations; but even should that occur, which may it please Heaven to forbid! The stress of conflict will still be here; and we shall still be the foremost actors and sufferers. God is plainly executing in the United States one of those great historic movements which notch the centuries; and he is not likely to be diverted from his foreordained plan by any foreign interference whatever. The strategy of Providence is exceedingly sagacious, comprehensive, and far-reaching; and is very apt to be successful, let who will attempt to thwart it.

What, then, are some of the more obvious lessons taught us by the momentous events of 1861?

1. I reply, first of all, that God really governs the world. I know we all professed to believe this in 1860, and never remember the day, perhaps, when it was not a leading article of our creed. Providence itself, as well as the Bible had often impressed it upon us. But who is not ready to confess that the course of events during the past year has taught this truth, especially as it regards our national life and affairs, with an emphasis altogether extraordinary? How dimly the most of us had been wont to perceive God’s hand in sustaining our republican institutions and government! We had almost come to feel that the Union and Constitution and liberties of our country needed no divine support; that they were as incapable of being overthrown as the Alleghanies or the Rocky Mountains; yea, as the great globe itself. But we have been rudely awakened out of this delusive dream. We have seen our idolized ship of state going upon those fearful breakers, which we knew had proved the grave of many a powerful and renowned government; we have listened through long, long months of agony to the creaking of her timbers, the dreadful sound of the rocks and the fury of the raging sea, until at length it became clear to us as noonday, that only one Pilot was wise enough or strong enough to weather the storm and save her from utter, hopeless wreck; and that was the Almighty Pilot, who planned and built the ship! And how well He has thus far justified our confidence! “If it had not been the Lord, who was on our side, now may Israel say: If it had not been the Lord who was on our side when men rose up against us; then the waters had overwhelmed us;. . then the proud waters had gone over our soul.” I have recently called your attention to the many irresistible proofs that we owe our deliverance to the special favor and interposition of Providence; and I need not repeat them now. You will, I am sure agree with me in the feeling that they ought to excite within us mingled awe, astonishment, and thanksgiving. If as a people we ever forget to praise the God of our fathers for the manner in which he hurried to our rescue in this appalling crisis, our tongues should forever cleave to the roof of our mouths!

But it is not merely in reference to what he has done for the salvation of the republic, that the past year teaches us how real is God’s government of the world. This whole civil convulsion, in all its aspects, proclaims, trumpet-tongued, the same truth; it does so, at least, to every thoughtful and devout observer.

You recollect the opening words of the famous French preacher at the funeral of the Grand Monarch: “God only is great!” In a similar strain we might well exclaim, as we recall the strange scenes of the vanishing year, and bid them a final adieu: “God alone rules among the inhabitants of the earth!” In the presence of such awful troubles and desolation—in the presence of such vast changes, coming home to the very bosoms and involving the dearest interests, the happiness and the national existence even of thirty millions of human beings—it seems a kind of impiety to recognize any hand but that which made the world. Some, I know, deem it an easy thing to show exactly how this storm arose; who and what were the agents in producing it; and how it might have been avoided. They can see in it nothing but the natural effects of obvious human causes. For myself, I can not assent at all to this view. It is only half the truth. Of course, I do not deny that this trouble has real and deep-seated human causes. It is no bare miracle, nor has it sprung up out of the dust. Never was there a great civil convulsion, whose historical grounds and motives were more distinctly traceable, or more worthy to be studied. But when we have gone as far in this direction as it is possible to go; when we have philosophized upon the matter to the extent of our ability, we shall still find ourselves confronted with difficulties whose only solution is the decree of Omnipotence. Both reason and religion will compel us to cry out with the psalmist: “Come, behold the works of the Lord! What desolations he hath made in the earth! He is terrible in his doings towards the children of men.” If there be a chapter in American history crowded with providential events and judgments, it is certainly that which contains the records of 1861. The very insignificance of most of the human agents only serves to bring all the more clearly into the foreground of the tremendous scene that mysterious Power, which led the hosts of Israel through the wilderness, which stood by Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego in the burning fiery furnace, which St. John, in his vision of heaven, saw riding forth in righteousness to judge and to make war, ruling the nations with a rod of iron and treading the wine-press of the fierceness and wrath of almighty God—that august Power before the breath of whose nostrils kings and statesmen and mighty men are as chaff driven by the whirlwind. The first great lesson, then, taught us by the events of the past year is the reality and beneficence of the divine government.

2. The next lesson which we have been learning from the same events, is the inestimable worth and sanctity of rightful human government. What loose and false notions used to prevail among us on this subject! How imperfectly we were imbued with the sentiment that civil society is a divine institution; that rulers are ordained of God for the terror of evil-doers, and the praise of them that do well; and that they are responsible to him for the faithful performance of their duties! Not that we directly denied this truth; on the contrary, it was not unfrequently inculcated from both the pulpit and the press; but we had only the faintest conception of its fundamental position in the moral order of the world; we hardly dreamed of its immense practical meaning and importance. We had been in the habit of regarding government so exclusively on its mere earthly side; of considering and treating it as the creature of our own will and of flattering ourselves for the skill with which we and our fathers had framed and carried it on; political power too, had been so prostituted to evil purposes, so divorced from the nobler influences, intelligence, and character of the nation, that there was a natural repugnance to mixing up what seemed so utterly worldly, with the thought of God, and giving it the sanction of his authority. There is nothing more antagonistic to the sentiment of reverence than hones contempt; and this is the very feeling which had for years been growing stronger and more intense among the best portion of the American people toward mere politics and politicians. The two terms were fast becoming synonymous for whatever is most groveling, mercenary, and unprincipled in human conduct. How, under such circumstances, could government itself retain any deep hold upon the respect and veneration of the people? The effect was exactly analogous to that which follows in the sentiments of a community toward the Church, when religion and its professors become widely infected with formalism, low morals, and hypocrisy. At such a time it is of little use to talk about the Church as an institution of God; men are in no mood to receive the doctrine. They are rather disposed to wish there were no church in the world. And thus thousands of the most intelligent and virtuous people in this country had grown so heart-sick of the political degeneracy, meanness, and corruption of the times; so filled with indignant shame and disgust at the manner in which power was prostituted to selfish and wicked ends, that, instead of looking up to government as an ordinance of God, they were rather inclined to wish there were no such thing in existence to stimulate men’s bad passions with its huge temptations!

But the experience of the past year has taught us new and more scriptural lessons on this subject. It has taught us that if there were no such thing as government in the world, human society would be changed into a hell upon earth. It has taught us that if there were no such thing as government in the world, human society would be changed into a hell upon earth. It has taught us that we can no more dispense with law, order, and civil authority than we can dispense with light and air and daily bread, in the sphere of our physical, or with property, marriage, and the family, in the sphere of our moral being. We have found out that God has placed us under government for the largest and most robust discipline of our nature; for developing in us the manliest virtues, loyalty, honor, fidelity, obedience, self-sacrificing courage, and public spirit; and that the proper way to show our discontent with its abuses is to labor with religious zeal for their correction, and to fulfill all the duties of a good citizen. We have, in a word, been taught deeper lessons respecting the true nature, the necessity, the just claims, and the boundless beneficence of rightful government during the past year than during all the previous three-score years of the century. And alas! for us, if we do not mark, learn, and inwardly digest them! What solemn lessons, too, have been given us respecting the real character and fruits of a government founded in lawlessness and treason! The grandest and best things are the most fearful when converted into instruments of unrighteousness. No sort of impiety equals that which comes of turning the grace of God into licentiousness. What form of social pollution is like that of an adulterous marriage? It was an “arch-angel ruined” who led on the rebel host of heaven. And so when the majesty of government is made the cloak and shield of unnatural rebellion, we have one of the most terrific spectacles ever witnessed among men. Such a monstrous spectacle has suddenly presented itself to the astonished gaze of heaven and earth, in the midst of this Christian land—in this second half of the nineteenth century. Mankind never looked upon one ore strange or impressive. I firmly believe it is designed by divine wisdom to teach the unhappy people of the South and the whole nation lessons, which neither they nor their children after them will ever forget. When we emerge out of this dark night of trouble, as with God’s blessing I believe we shall, it will be with such a sense and such memories of the power and benignity of rightful free government on the one hand, and of the cruelty and terrors of a lawless, tyrannical government on the other hand, as shall compensate, in no small degree, for all our sacrifices. We are a youthful people yet; and we shall still be assailed by gigantic temptations to break asunder those bands of righteous law and restraint which, with such pious wisdom, our fathers wrought into the whole framework of our national life, and which no people like a potter’s vessel. May it not prove to us, in times of future trial, a bulwark of moral strength that thus, in the early manhood of our career, we had borne the yoke and learned obedience by the things which we suffered?

3. Another weighty lesson, vividly taught us by the events of the past year, is the extreme weakness of good men, and their liability to be carried away by popular frenzy. I know of nothing connected with this great rebellion more unspeakably sad than the hearty approval it has received from thousands of the best men and women in the South—persons of unquestionable virtue, intelligence, and Christian principle. Instead of regarding it as a colossal crime, they profess to regard it as one of the holiest wars ever waged. No Crusader ever fought for he recovery of the holy sepulcher with a fiercer zeal than many of them have displayed in this assault upon the life of their country. And if we had lived in the South, who can say how few of us would not have followed their example? I do not allude to this subject here for the purpose of uttering harsh words; I have no heart for that. The simple fact is painful and dreadful enough without angry comment; at least from the sacred desk. It is something to weep and wail over. May the Lord forgive them; for they surely know not what they do! And for ourselves, let us learn from this appalling instance what a poor protection mere personal virtue, intelligence, or piety affords against a thoroughly demoralized and frenzied popular sentiment; how readily the most solemn oaths and obligations and opinions may be swept away when once the public reason is dethroned, and mad passions installed in its place; above all, what an unutterable curse it is for society to carry in its bosom and idolize as divine an institution, which, like slavery, is essentially at war with the first principles of Christian justice, humanity, and civilization. I am very far from thinking that good men at the South were any worse than good men at the North. But they breathed a social atmosphere, charged with perilous stuff; they had long eaten of an insane root; and it only needed the favoring circumstances to concentrate the poison, and plunge them in one common, universal delirium. Not with pharisaic pride, but with heartfelt grief, pity, and prayer let us contemplate their deplorable state, and thank God, not that we are better than they, but that our lot has fallen to us in higher latitudes and on freer soil. But it would be wrong to forget here that there have been bright exceptions to the general madness, which has swept over the revolted States. History does not record finer instances of patriotic fidelity and heroism than have tinged with a silver lining this black cloud of conspiracy and insurrection. Not a few have been found to whom Milton’s beautiful description of the seraph Abdiel might be justly applied:

“Among innumerable false, unmoved,

Unshaken, unseduced, unterrified,

His loyalty he kept, his love, his zeal;

Nor number, nor example with him wrought

To swerve from truth, or change hi constant mind,

Though single. From amidst them forth he passed,

Long way through hostile scorn, which he sustained

Superior——-“

4. And this leads me to note another lesson written as with the point of a diamond upon the events of the past year; I mean the paramount claims of our country to our services, property, life, and every thing earthly that is ours. We had often felt the supremacy of these claims in reference to other times and former generations; and we had read with admiration and delight of the manner in which they were met by the noble army of patriots and martyrs to liberty from the Hebrew, Grecian, and Roman ages down through all the Christian centuries to our venerated sires. But we ourselves have lived in quiet, prosperous times, and it has been only to a very limited extent that we have felt in our own persons the more severe pressure of public duty. As a consequence, it can not be denied, the patriotic sentiment had been greatly weakened and injured for want of discipline; private interests had assumed a dictatorial power; we were giving ourselves up, without let or hindrance, to the pursuits of gain, to the buying of pieces of land, of oxen, and of merchandise, and to the building of fine houses, and doing our own pleasure—in a word, to making money and to self-indulgence. I do not say that this was all, that no higher motives actuated our lives; but simply that the overwhelming tendency and temptation was to move along a very low plane of thought and action, to regard life as chiefly intended for our private use and profit. Was it not so? Did we not read and hear about deeds of heroic self-sacrifice and devotion to great principles very much as of a winter’s evening, around his own fireside, one reads about shipwrecks and storms at sea? But the case is altogether different now. This year has initiated us into a higher lore. It has taught us that next to God we belong to our country, and that at her bidding there is no sacrifice we ought not cheerfully to make—no toil we ought not to undergo—no danger, though it be to march to the cannon’s mouth or stand in the imminent deadly breach, which we should shrink from facing; it has made us comprehend that almost all the things we had been used most to think of and to prize, are as nothing compared with her approval and benediction. How vividly conscious we now are, that in serving our country we are in the glorious service of justice, law, freedom, humanity, and religion! That in spending and being spent for her, we are helping forward the great cause of God, and treasuring up blessings for our posterity and for all mankind! Who can estimate the elevating and transforming influence of such thoughts as these, suddenly awakened as they have been during the past year, in the minds of millions whose existence before had been chiefly absorbed in mere material interests! What an education for the public spirit, the loyalty, and whole manhood of the nation! Certainly it is some compensation for the woeful losses and suffering and horrors through which we are passing, that they serve as the providential occasion for developing in the heart of the American people that sublime consciousness of truth and duty which is at once the strength and the crowning grace of a free Christian state. Thousands of loyal citizens who began the year in health are now sleeping in a soldier’s grave or pining in gloomy prisons and hospitals, or weeping the tears of widowhood and sharp bereavement; tens of thousands more who began it in wealth will end it in poverty; innumerable fortunes have been thrown overboard and sunk out of sight in this sea of trouble. It would be hard to estimate the grief, waste, loss, and destruction of property, of business, and of solid schemes of life which have come upon the nation; and yet if we reckon wealth and prosperity as Heaven does, the country and the people are incomparably richer than they were twelve months ago. How much richer in patriotic confidence and affections, in devotion to the general good, in patience and virtuous self-control, in manly valor and unboastful self-reliance, in gratitude to the past, in hope and high resolve, in reverence for both law and liberty, and in the assured feeling that the God of our fathers is still our God and will be the God and guide of our children! This is a kind of wealth which, though coined out of hearts’ blood, is more precious than rubies; there are no jewels which adorn the brow of a Christian people with such resplendent beauty.

The lessons of which I have spoken by no means exhaust the impressive teaching of this year of wonder. What new and terrible light it has poured in upon the hidden depths of American slavery! What amazing proofs it has given us of the power and resources of political crime, when once organized into a system, actuated by the spirit of a domineering social caste, backed by popular frenzy, and led on by a band of resolute, remorseless, and desperate conspirators! Only amidst the horrors of the first French Revolution does modern history offer a parallel. What light, too, do the events of this year cast on the disputed problems respecting the progress of Christian society, and the effect of that progress upon individual character and the old depraved passions of human nature! But important as these points are, I will not stop to dwell upon them now. Some of them, indeed, have been considered in previous sermons; and all of them are likely to acquire fresh interest and meaning as this fearful drama of Providence shall be more fully developed.

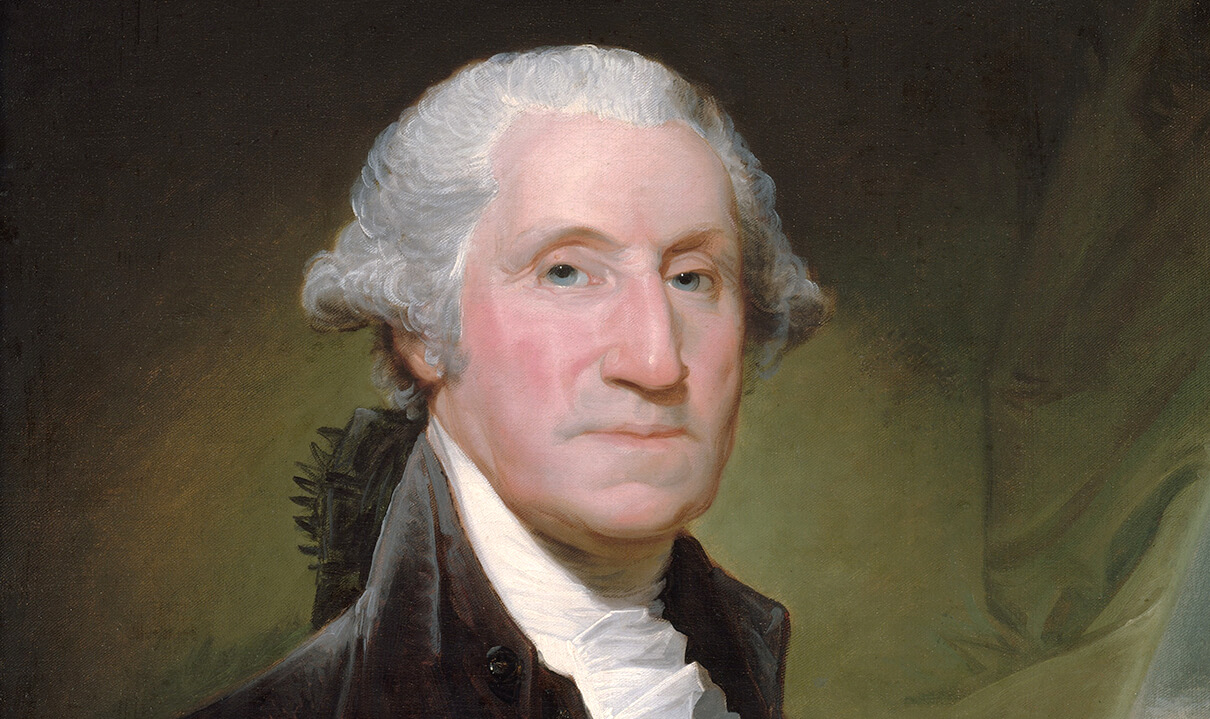

5. I pass, therefore, to a closing lesson, which brings the subject home directly to our own bosoms, and is a most fitting reflection for this last religious service of the year. It is the vanity of the individual man, except as he stands related to God and eternity. I spoke a moment ago of the paramount claims of our country and the general good over our private interests. But, after all, how insignificant is any one individual among thirty millions, is any single life in the great perennial life of the nation! It is like a single grain of sand upon the sea-shore; it is a fugitive wave among the infinite, multitudinous waves of the ocean! You and I are bound to give all we have to our country, and to die for her if need be. But how easily our country can dispense with your services or mine, with you and me! Our friends would miss us, and mark the spot and the hour when and where we vanished from sight; but the nation, busied and oppressed with its tremendous cares, would move on as if we had never existed. There may seem to be exceptions now and then, like that of the illustrious soldier and patriot whose loyal solicitude has just hurried him back across the wintry Atlantic, and whose career has contributed so largely to shape that of our Union. But even these rare exceptions are so chiefly in appearance. It is the personal virtue and nobleness, which especially entwines such men’s names with the history and fame of their country. If Washington had not been a man of consummate personal worth, would he ever have been so enshrined in our grateful love and veneration? Here, then, public and private duty are reconciled. We serve our country and the world best when we most diligently cherish those pure, generous and holy affections, those immortal virtues, which prepare us for a better country, that is, an heavenly—for the eternal fellowship of saints and angels, and for the presence of our God and Saviour. Thus is the ideal of a perfect Christian culture one with that which makes us good men and women, good citizens, and good in all the varied relations of our earthly life. Let us see to it, then, that first of all by prayer, repentance, faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, and a devout imitation of his sinless example, we perform aright our inalienable personal work. Let us allow nothing—no pressure of public care, no excitement of the times, no worldly attraction or interest—to seduce us for a moment from that inward, spiritual allegiance which we owe to the adorable Captain of our salvation.

Let us live in Christ and to Christ, and we shall then live most wisely for all about us. This is the best method of rendering ourselves useful and a blessing to our homes, our friends, our country, the church, and the whole world. This is the way to enjoy ‘central peace” amidst the endless agitations of temporal existence, and to secure a seat among the happy few

“Who dwell on earth, yet breathe empyreal air,

Sons of the morning—“

Thus standing at the post of duty, like faithful sentinels, we shall not be surprised or affrighted by the coming of the Son of Man, whether he come in the second or in the third watch. “Blessed are those servants, whom the Lord when he cometh shall find watching; verily I say unto you, that he shall gird himself and make them sit down to meat, and will come forth and serve them. And if he shall come in the second watch, or come in the third watch, and find them so, blessed are those servants.”

HOW TO MEET THE EVENTS OF 1862.SERMON. 1

BY REV. GEORGE L. PRENTISS, D.D.,

OF NEW-YORK CITY.

HOW TO MEET THE EVENTS OF 1862.

“Unto the upright there ariseth light in the darkness: he is gracious, and full of compass on, and righteous. He shall not be afraid of evil tidings: his heart is fixed, trusting in the Lord. His heart is established, he shall not be afraid, until he see his desire upon his enemies.”—PSALM 112: 4, 7, 8.

I CALLED your attention on last Sunday afternoon to some of the providential lessons taught us by the extraordinary events of the past year. My present aim will be to show in what spirit we ought to look forward to the events of the new year, and how we should prepare ourselves to meet them; or, to express it in another way, let us consider what is the most Christian posture of mind toward the future at such a time as this.

The subject, I think, every one will admit, is eminently practical and seasonable. It comes home to the business and bosoms of us all. If we have any real faith in God, never was there a moment better fitted to test and to illustrate it. If there be a fundamental difference between the religious man and the worldling, now is the hour for letting it be seen. If Christ’s Gospel, as in several recent discourses I have tried to show, is intended and able to transfigure our earthly life with sacred beauty, to give us comfort, uphold our fainting spirits, and brighten the darkest cloud of trouble with the bow of celestial promise, let it do so now. Never before had we such an occasion to put in practice all the noblest principles of our religion. Never before had we such an opportunity to do signal honor to our Lord and Master by the manner in which we represent him to the world. Never before were we summoned by so loud a voice from heaven to take unto us the whole armor of God, and quit us like true Christian men and women. If, in such a storm as this, we are found faithless and craven-hearted, it will only demonstrate how unworthy we are of the name we profess, and of the privileges we enjoy; it will only show that we deserve to be cast overboard as so many mere Jonahs and cumberers of the ship.

In what spirit, then, ought we to look forward to the events of 1862, and how should we be prepared to meet them when they come? If our blessed Lord himself, or one of his inspired apostles, should appear to answer this question for us, what would that answer be? We know what it would be; for in effect they did answer it eighteen hundred years ago. It is truly marvelous how much in our Lord’s teaching, in that of his Apostles, and in the Old Testament, has reference to the manner in which great public troubles should be encountered; nor is there any thing in the Holy Scriptures that exhibits, in a light more impressive, the moral elevation, power, and magnanimity of the Christian spirit. It is not, however, in the teaching of the Bible alone that we get the right answers to the question I have asked; we have it answered practically a thousand times over in the whole history of the Church. How large a portion of that history is a record of suffering! If there is any thing that the Church ought to understand well, it is the Gospel art of meeting great tribulations—of facing every kind and degree of public and private calamity; for her experience has sounded their lowest depths. There is no wave and no billow which has not gone over her. It is hardly possible to conceive an exigency so momentous or so perplexing, that nothing analogous to it can be found in her annals. There were, no doubt, some events in the year just closed which form an altogether new chapter in the book of universal history; it could not be otherwise. Providence is not wont to copy itself. Its principles are always the same, because they are perfect and eternal; but its lessons, like spring-flowers, have an infinite variety and freshness. There is always something unique about them. They carry the race on to a higher point of view, and a more complete knowledge of the truth and ways of God. They shed new light upon the great problems of humanity and Christian society. They help to bring nearer the day when the reign of Divine Justice shall be fully inaugurated from the rising of the sun unto the going down of the same. It will be so, we may rest assured, with the lessons and events of 1862. The events of 1862! How little we foreknow exactly what they will be; how they will affect our country and the world, or how they will affect us individually! Never before was the immediate future so utterly inscrutable. Changes which, not long ago, would have consumed half a century, now occur in a single year. Events move on with a rush like ice issuing in the spring from one of our Northern rivers. There is something in their magnitude, rapidity, and prodigious effects which baffles and defies all foresight. A thousand years used to be with the Lord as one day; now one day is almost as a thousand years. Never was the sagacity of men most profoundly versed in the knowledge of affairs, and of the past, so utterly at fault. Whether this is owing to material, social, or rather to specifically providential causes, or to all three combined, we need not stop to inquire; enough that the fact is indisputable. This new year is likely to be quite as eventful and exciting as the past. We can not tell what the course of things will be; but be it what it may, we know it must be one of incalculable importance. It will, perhaps, decide the fate of our country; nor would it be very strange if the destinies of several other countries should be virtually fixed this year. One has only to glance at the colossal forces arrayed against each other, all striving for the mastery; one has only to reflect that peace and readjustment are now impossible, except through a great victory, or a great defeat, and the understanding of a child can perceive that we are drawing near to events, the fame of which will “roll sounding onward through a thousand years.”

And now, I ask again, in what spirit does it become a Christian man to look forward to and meet them?

1. In the spirit of devout filial trust in God. This is the first and best thing. Nothing else can supply its place. Prayer and faith put the soul at once in the right temper for meeting whatever is coming to pass. They connect the events by anticipation with that Almighty Power without which not a sparrow falleth to the ground. God will govern the world this new year, from beginning to end, just as wisely and effectually as he overned in the past; and who of us can refuse him the tribute of our grateful praise and adoration for the manner in which he governed it last year? Who is disposed to charge him with having made any mistake? He will commit no mistake in 1862. He will allow no one to thwart or circumvent his plan. That plan is already formed, even to the minutest detail; it includes all the events of the year up to its dying second; many of them will be strange and unexpected to us, but not one of them will be so to God. There is not a shadow of doubt, not a shadow of reason to doubt that he will manage the affairs of our country during the next twelve months with infinite skill. There will be a great deal of bad management on the part of men, as there has been in the past; but out of these very errors the divine skill is sure to elicit some ultimate advantage. If there should be no human mismanagement; if every thing should be done exactly as we might wish, or think best, it would be something unheard of in the history of the world.

Now, if this be a true statement of the Christian doctrine of providence—and I ask you, if it is not?—if, moreover, that doctrine is no barren theological dogma, no pious illusion, no mere theme for the pulpit, but the most fruitful and substantial fact in the sphere of human affairs, then, what a sublime resting-place it affords to our anxious thoughts, as we listen to the roaring of the waves, and try to peer out into the midnight darkness that enshrouds the future! We have heard, during the past year, a great deal about the masterly strategy of our generals, and the triumphs which in a little while were sure to crown it. But experience has already taught us that this is no certain reliance, and that able combinations may be formed on the other side. It is eternal Providence alone whose combinations are unerring and always successful; for God sees the end from the beginning, and can cause the victory of enemies and the discomfiture of friends alike to further his own designs. If any one is afflicted with a feeble impression of this truth, let him read through his Bible again, and see how from the book of Genesis to the book of the Revelation it shows God’s sovereign hand in the world. That ruling hand is strong and skillful as in the beginning. It is as busy in our affairs to-day as it was in the affairs of the chosen people at any moment in their history: it is as busy in our affairs to-day as it was in any events described in the Apocalypse; as it was in the blessed Reformation of the sixteenth century; in the civil wars of England; or in our own struggle for national independence. How absurd to believe that God notes the fall of a sparrow, and yet takes no part in a contest which shakes the world, and involves the most vital interests of Christian civilization! Rest assured, he not only takes part in it, but the chief part. Rest assured, the struggle is his, and intended to secure his ends. This is not denying the proper freedom of the human agents, nor the reality of the human causes; it is merely asserting that above all these, and running through all these, is a Providential cause and agency to which they are subordinate, and which is the true key of the moral situation. Such is the simple teaching of religious faith. Let us endeavor to practice it to the full. While others are floundering in the bog of endless conjecture and worldly calculation, or tossed to and fro in the whirlpool of excited popular opinion, let us stand firmly upon the Rock of Ages, lifting up our heads in the strength of filial trust and prayer. It is always folly to try to walk through this world by sight only; it is madness to do so now. If we would not be confounded nor put to shame; if we would look the future in the face without dismay, we must learn to keep step to the music of Providence, and say continually in our hearts: Allelulia! For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth.

2. Armed with such a joyous and devout trust in God, it will not be difficult for us to exercise in all things a spirit of Christian patience and moderation; and that is the next point. I am aiming to show how we may most honor our religion by the manner in which we demean ourselves in a time of public calamity; and I have said that the first requisite is to put ourselves in direct communion with God, reverently intrusting our cause to him, and leaning upon his arm. This is a posture of the human mind than which nothing nobler can be conceived of. But it is not easy to attain it: a bare wish, a volition, a sermon will not make it ours. It has severe conditions, like all eminently good things: and one of these conditions is a spirit of Christian patience and moderation. You can not rest in God without a corresponding equipoise and rest in yourself. A state of reasonless excitement and passion is utterly hostile to prayer and religious trust. It needs only a slight acquaintance with our mental constitution to see—what is indeed evident from daily observation—that lawless passion, in all its forms, and whether it express itself in word or deed, discomposes and enfeebles the soul. It is, for the time being, a dethronement of reason, converting the wise man into a fool, and the bad man into a maniac. It casts a cloud over whatever is fair, generous and strong in human character. If it once gets possession of a whole people, its effects are like a conflagration. Nothing that stands in its devouring path is sacred anymore. The solemn temples, the halls of justice, the venerable monuments of other times, the galleries of art, the sanctuaries of misfortune and distress, and the homes of the people—all turn to ashes before it. It is indeed a fearful thing, and we can not guard against it with too much vigilance. Many seem to feel as if the exciting times justified almost any amount of impatient and furious emotion. But that is certainly a strange mode of reasoning; it is as if one should argue in favor of the freest use of strong drink, because there was an extraordinary prevalence of intemperance; or, as if one should think it a good time to set all sail, because a hurricane was blowing. No doubt, the exciting times supply inexhaustible fuel for the stormy passions of our nature; they render it exceedingly difficult for the wisest man to keep his balance; but is that any good reason why he should not keep his balance? Because the temptations to cutting loose from the safe anchorage-ground of Christian principle are overwhelming, should we, therefore, deem it a light matter to cut loose and be driven forth, rudderless, upon the wild, tempestuous waves? No, my brethren; that would be a very childish course, dishonorable equally to our manhood and to our piety. Exciting and perilous times are the ones, of all others, for the exercise of the most heroic and religious qualities; they are the times appointed for the highest triumph of Christian fortitude, calmness and self-control; they loudly call for and presage general ruin unless they find silent, thoughtful, self-poised and lion-hearted men, who loathe boastful noise and bluster, who fear God, and will not swerve from the path of justice, duty and honor, though a million of voices clamored never so fiercely for them to do so. It is always easy to give way to the petty, selfish and malignant passions; at such a time as this it is easier than to think or speak. There is nobody so bad or so foolish that he can not do it; and there is nobody so wise and good that he is not in constant danger of doing it. Of course, I am not arguing against strong feeling, nor censuring or deprecating its reasonable expression. No one, it seems to me, can now feel right without feeling deeply. Indifference, while such issues are pending, is a sort of moral treason, and I pity the man who is cursed with it. But there is a world of difference between profound and boisterous, unbridled or rancorous feeling. Our rightful emotions can not be too profound; but they may be readily vitiated and wasted in fretful talk, clamor and empty rage. They may get extravagant and lawless. We ought to husband them with religious care; we should aim to concentrate them upon the best objects, and to elevate them into deliberate convictions and principles of action. Without them there is indeed nothing truly generous and grand in human character; we can not be thoroughly and effectively in earnest if not impassioned. But Christian passion is not that of gall and wormwood; it is the wise inspiration of love, and pays dutiful homage to truth and justice. When roused to the utmost pitch of righteous indignation, it still remembers the saying that is written: “Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.” Nothing, in fine, is more beautiful in times of general distress and agitation; nothing indicates more plainly a soul planted above the turmoil of the hour and in close alliance with heaven; nothing is surer to exert a soothing, benign influence than the gentle spirit of Gospel patience and moderation:

“A sweet, revengeless, quiet mind,

And to one’s greatest haters kind.”

As a people, we are taking lessons on this subject, which ought to make us wiser. We have witnessed, during the past year, the frightful and barbarizing effects of unrestrained passion, on a scale unknown before on this continent; and our ears have recently been stunned by loud reports of the same explosive mischief from beyond the ocean. We have seen the public sentiment of the first Christian nation in the Old World completely frenzied by sudden rage, and, casting all patience and moderation to the winds, pour itself forth in a torrent of vindictive menace and vituperation; and that, too, against a kindred Christian people, perplexed in the extreme, and agonizing in a desperate struggle for their very existence. Were not such a fancy precluded by the practiced literary skill and unmistakable Anglican manner of the assault, one might easily imagine that the cunning emissaries of the great pro-slavery rebellion itself had all at once been installed in the responsible editorial office of guiding the public opinion of the British nation, already so prejudiced and misled by their stealthy machinations. What a comment upon Christian civilization in the second half of the nineteenth century! What a fine illustration of the boasted progress of society! I do not forget that this tempest of wrathful abuse and threatening was met on the spot by generous, brave words of Christian rebuke and moderation; we may feel quite certain it found no echo in the heart of England’s most excellent and beloved, but now, alas! widowed Queen, as we are assured it did not in that of her deeply lamented consort. Neither do I forget to what an extent it was raised, by the artful appeals and misrepresentation of an unscrupulous press. But after taking all these things into account, it still remains an exceedingly painful and disheartening spectacle. Nor have we ourselves always been guiltless of similar violence. But let us hope that a better day is dawning. The dignified and considerate demeanor of the American people under the recent severe trial of their temper, is highly auspicious, and seems to me a fit matter for devout thanksgiving. They would not have met such a provocation two years ago with the same calmness. It will be no light reward for all our present sufferings if, exorcising the aggressive, unclean spirit of national pride and self-conceit, they teach us to understand that the real glory of a Christian people, as of a Christian man, is to be just, patient, and reasonable, as well as strong.

3. But I hasten to note another thing that ought to mark the spirit with which we go forward into the new year. It is a courageous willingness to make any and every sacrifice to which our country may call us. The year opens with many favorable omens. As we look back and recall the beginning of 1861, it seems as if a mountain had been lifted from the heart of the country. Then we were in horrible fear lest the Lord God of our fathers had abandoned us; lest the ancient ancestral glory which, from the day it was set up, had filled our political tabernacle, was about to depart, and our life as a people was to be extinguished in an abyss of national idiocy, cowardice, and shame. That hideous dread God has been pleased mercifully to remove from us. He has breathed upon the hearts of the people, and summoned them to arise and shake themselves from the dut of their selfish interests and old vices—to put on their beautiful garments, and array themselves for both the battle and the altar of burnt-offering. Nor have they been disobedient to the summons. Never in our day did they stand on so high a moral vantage-ground; never, I firmly believe it, were they in closer alliance with eternal justice, or more ready to do its bidding, than they are now. But a vast work is yet to be done; a work of whose magnitude the most of us have only the faintest conception, and which no man can adequately comprehend; a work requiring consummate wisdom, fortitude, valor, energy, perseverance, loyal self-devotion, and faith in God; a work worthy to have tasked any generation of good citizens, soldiers, and statesmen that ever walked the earth. And if Moses, David, Nehemiah, Daniel, and the most renowned patriots of Greece and Rome—if King Alfred and Washington were before me, I would still say so! This is clear as daylight, take what theoretical view you please of the past, the present, or the future. If victory should henceforth perch upon the national standard on every battle-field; if peace should hasten to come back and spread her white wings over the whole reunited republic, even then it would be so. We can not be too deeply impressed with this truth; especially should it e engraven, as with the point of a diamond, upon the consciences of our public men, our President and his Cabinet, our Senators and Representatives, the leaders of our army and navy, and all others, of whatever calling, who occupy places of influence and authority in the land. That man is not fit—that men is utterly unworthy to have a voice in the national councils, or to direct the national forces, or to guide the popular opinion at this awful moment, who does not see and is not greatly sobered by the thought that he is not living in ordinary times, nor fulfilling ordinary functions, but that, by the appointment of Almighty Providence, he is transacting business for unborn generations and for the human race. If, inste4ad of this, he is merely looking out for some plank which he may appropriate from the wreck of the public prosperity, if his chief thought is how to make money out of the distresses of the nation, or how to further his petty, selfish political ends, then, I say, he is a traitor to God and his country, and, if he does not repent, will doubtless at the day of judgment, if not sooner, receive a traitor’s doom. All our ends now should be for God, our country, and mankind. What are we individually, and what are all our earthly interests—what is any man in the land, I care not how high he stands—and what are his individual interests, that we should stop to weigh them or ourselves in the balance against such public claims as now press upon us? Let us, then, face this new year and its unknown events armed with a courageous willingness to perform any service and make any sacrifice for the sake of helping on the good cause. It is not impossible that foreign war may be added to our intestine strife. If so, let us pray that it may be thrust upon us wrongfully; and then, conscious of right, we may calmly, reverently, without boasting, yet without dismay, join issue with a world in arms. Then the stars in their courses will fight for us, as they fought against Sisera. Friends innumerable will spring up throughout Christendom, and even in heathen lands. Above all, the Lord of hosts will be with us, and will take part on our side. This, my brethren, is the way to peace in calamitous times: an unflinching loyalty to duty and to God. This will keep any man from

“Starting and turning pale

At Rumor’s angry din;

No storm can then assail

The charm he wears within:

Rejoicing still, and doing good,

And with the thought of God imbued.”

4. The subject is so important and fruitful—it is so emphatically a life-question for us all, that we might well spend many hours in considering it. But I will detain you with only one further remark. Let us enter upon the new year in the full assurance of hope; that is the natural conclusion of all I have been saying, and it is, moreover, our Christian birthright. Let us not hang down our heads like bulrushes, but lift them up, as our Lord bids us, assured that, amidst all these troubles, our redemption is drawing nigh.

Though weak, and tossed, and ill at ease,

Amid the roar of smiting seas

And ship’s convulsive roll,

let us still keep our eye fixed steadfastly upon the eternal Pole-star, and our souls staid upon the promise and oath of our Almighty Leader. Then in due time shall our light break forth as the morning, and our darkness become as noonday. Let us not be afraid of evil tidings. The future of the republic extends beyond a year, and will be long enough, let us not doubt, for the complete triumph of law, justice, freedom, humanity, and Christian truth. Wherefore, my brethren, be strong, and rejoice always in the Lord and in the power of his might; for surely the wrath of man shall praise him, the remainder of wrath shall he restrain. Pray without ceasing. Let patience have her perfect work. Let your moderation be known unto all men.

Now our Lord Jesus Christ himself, and God, even our Father, which hath loved us, and hath given us everlasting consolation and good hope through grace, comfort your hearts, and establish you in every good word and work. Amen.

REV. GEORGE L. PRENTISS, D.D.: NEW-YORK, January 8, 1862.

DEAR SIR: We respectfully ask, for publication, copies of the two sermons on “The Lessons of 1861,” and “The Events of 1862.” The times urgently demand the employment of every influence calculated to inspire the public confidence, allay impatience under existing evils, and to excite a proper spirit to meet the dangers and difficulties which impend over the country. The sermons in question seem to us so well designed to effect these results, that we wish to extend their influence beyond the congregation to which they were addressed. Hoping for a favorable answer to our request, we are, dear sir,

Yours very truly and respectfully,

Wm. E. DODGE,

LEGRAND B. CANNON,

GEO B. De FOREST

R. H. McCURDY,

HERMON GRIFFIN,

HENRY B. SMITH.

D. D. LORD,

. . .

NEW-YORK, January 9, 1862.

GENTLEMEN: The sermons, of which you request copies for the press, were written in haste and without any thought of publication. But if you deem them fitted to further in the least the righteous cause, they are entirely at your service.

Believe me most truly yours,

GEORGE L. PRENTISS.

Messrs. Wm. E. DODGE,

LEGRAND B. CANNON,

GEO. B. De FOREST,

R. H. McCURDY,

HERMAN GRIFFIN,

HENRY B. SMITH.

D. D. LORD,

Endnotes

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!