In the decades leading up to and following 500th anniversary of the discovery of the New World in 1992 the vast preponderance of both academic writers and popular commentators take an overwhelmingly negative view of Christopher Columbus. In fact, these voices are so critical that currently the, “dominant picture holds him responsible for everything that went wrong in the New World.”1 This new revisionist trend goes against the previous centuries of orthodox thought, research, and opinion.2

Much of this recent tide of thinking arises from the philosophy of doing “history from the bottom up.” According to leading advocate Staughton Lynd, revisionists approach history with the assumption that, “the United States was founded on crimes against humanity directed at Native Americans.”3 Such a premise, however, means that the Discoverer of America, Christopher Columbus, must also have participated and begun those “crimes against humanity.”

In the most famous work of “bottom up” history, A People’s History of the United States, author Howard Zinn unilaterally claims that the indigenous people held a higher moral standard than the European nations at the time. He declares that Columbus did not stumble into an “empty wilderness,” but rather a remarkably “more egalitarian” society where the relationship between men and women were “more beautifully worked out than perhaps any place in the world.”4 By all “bottom up” accounts, the New World was a paradise destroyed by Christopher Columbus and those that followed.

But what did the New World actually look like when Columbus landed on its shores in 1492? Contemporary accounts from both European and Indigenous sources reveal that the pre-Columbian world was a place where slavery, trafficking, sexual exploitation, oppression, and even genocide was commonplace prior to any European contact. As will be seen, the discovery eventually put a stop to many of these heinous acts—ultimately elevating morality instead of lowering it.

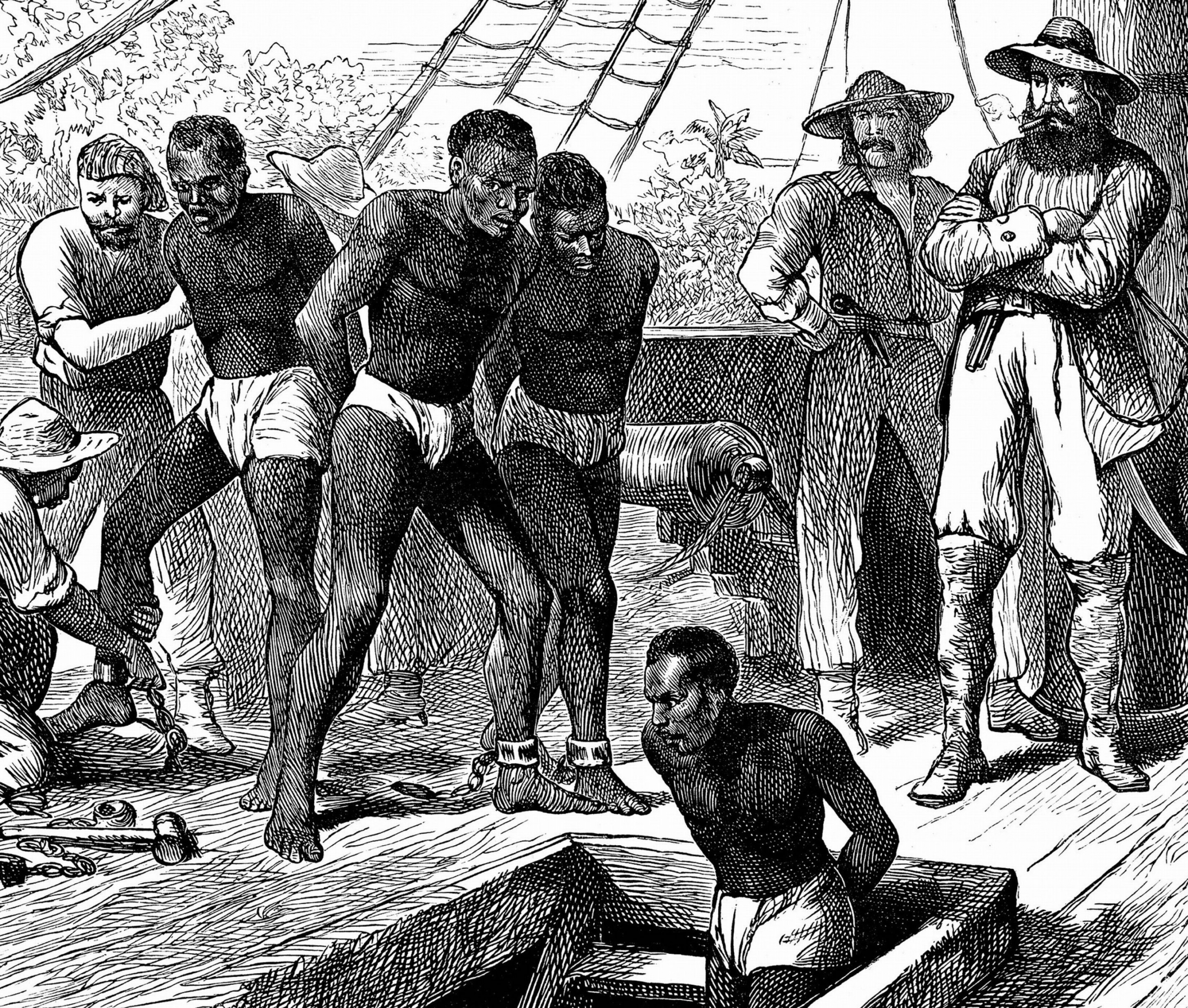

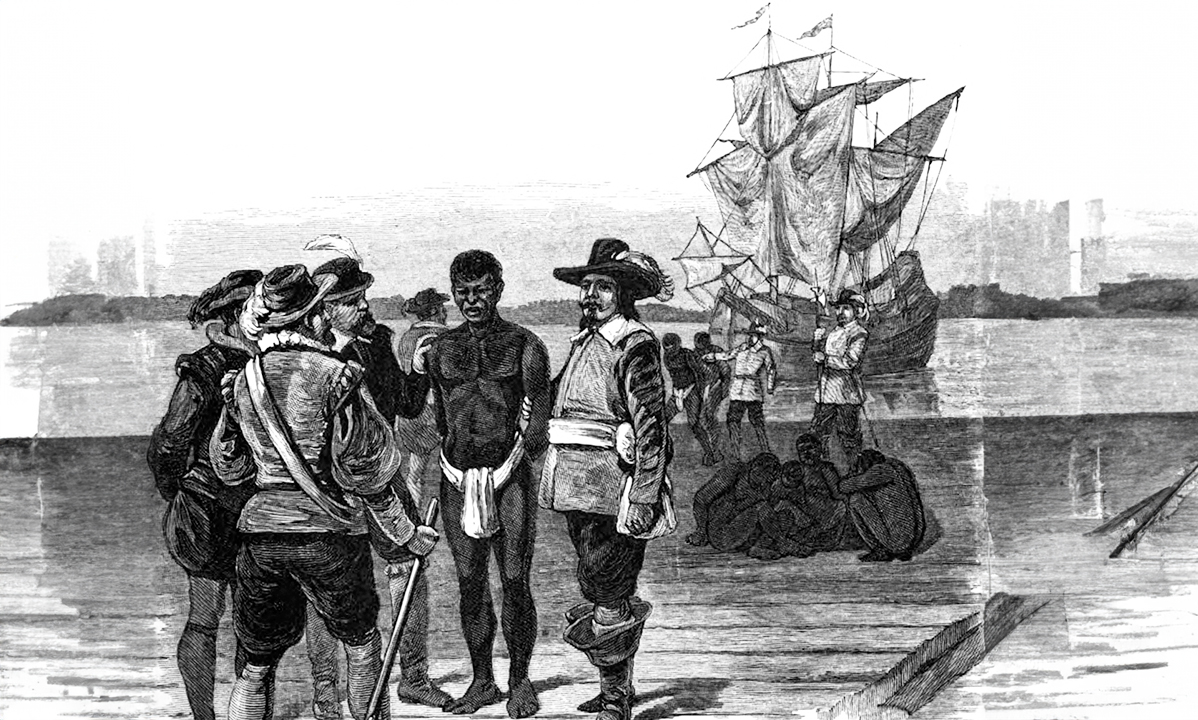

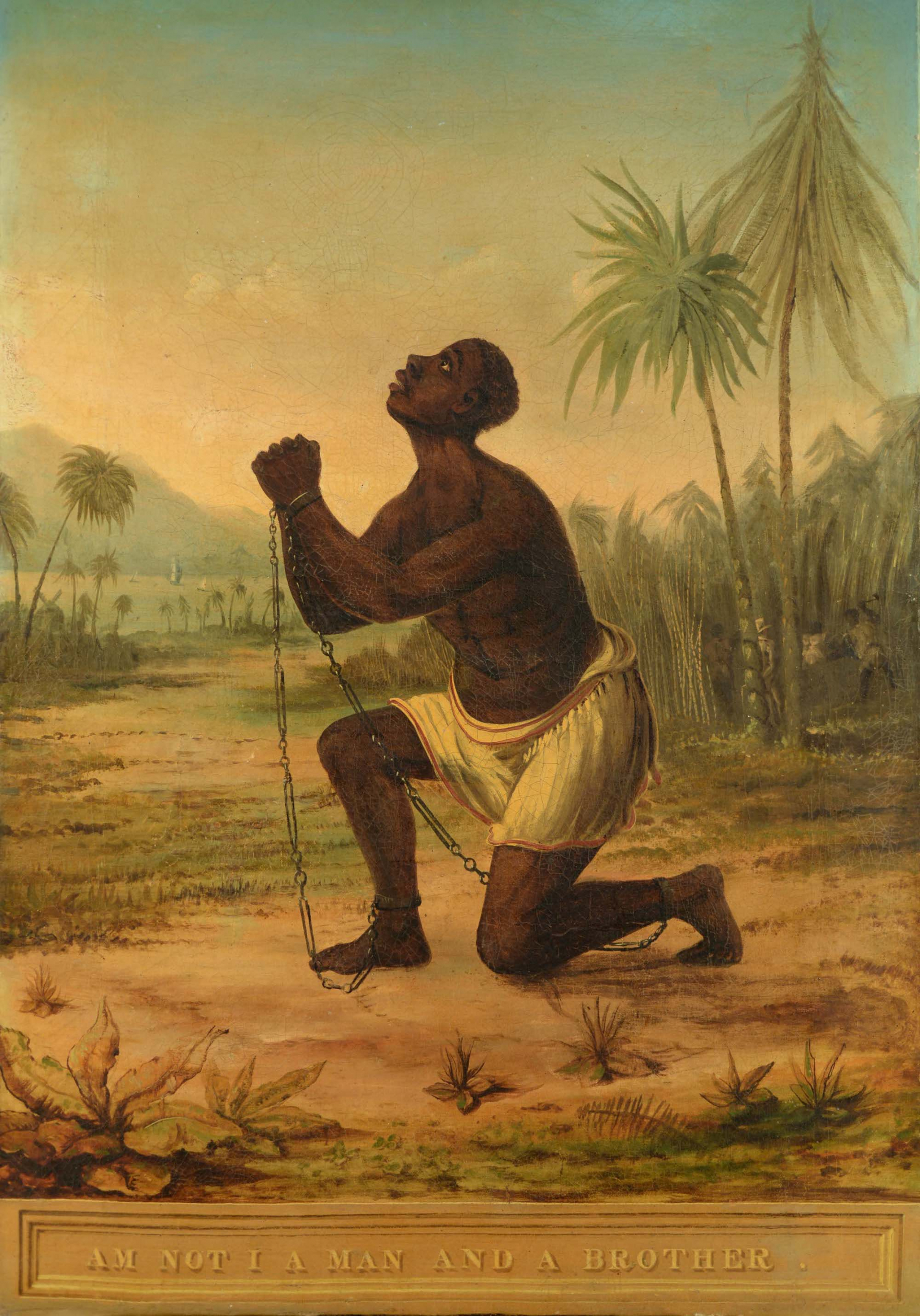

This dissidence between what revisionists claim and the clear historical truth continues to direct America’s national conversations today. In the early 21st century, one of the pivotal conversations in America concerns American’s relation to slavery. The New York Times has launched the “1619 Project” which claims to observe the, “the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery.”5 However, slavery in the America’s began well before 1619—to ignore this fact is to overlook all the enslaved people who lived in America before Columbus came. It is to dishonestly let an agenda’s narrative rewrite history.

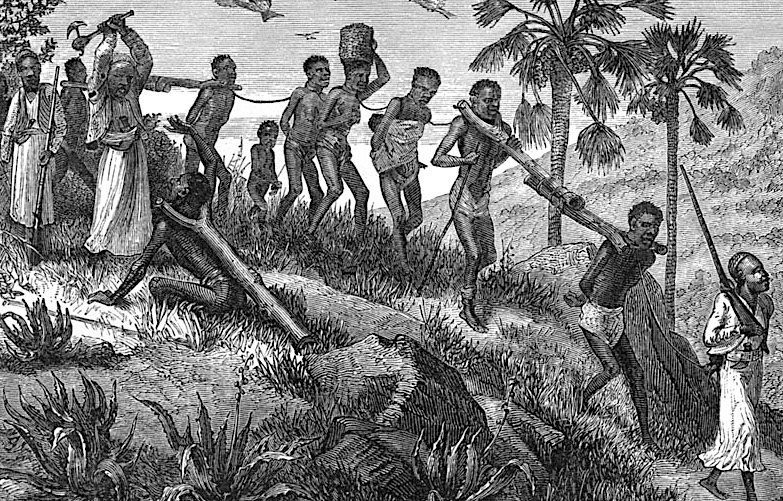

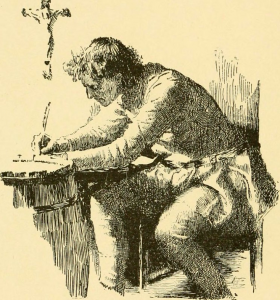

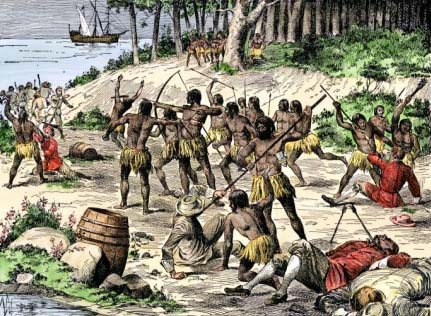

Ironically, the man now blamed for America’s slavery was the first to shed light upon the institutions of oppression among the native Americans. In fact, the pre-existent native slave trade was so prolific that, “wherever European conquistadors set foot in American tropics, they found evidence of indigenous warfare, war captives, and captive slaves.”6 The journals, letters, and reports documents first-hand how the various tribes were already practicing slavery prior to the arrival of the Europeans.

Take briefly for instance, the Carib tribes who had widespread institutions of perpetual slavery, captive mutilation, and even villages dedicated to the sexual exploitation of captured Taino women forced to produced children which their masters then ate. Facts stand in stark contrast to the “more egalitarian” fabrication of Zinn. Such horrors do not show a “more beautifully worked out” society in the slightest—in fact, it does quite the opposite.

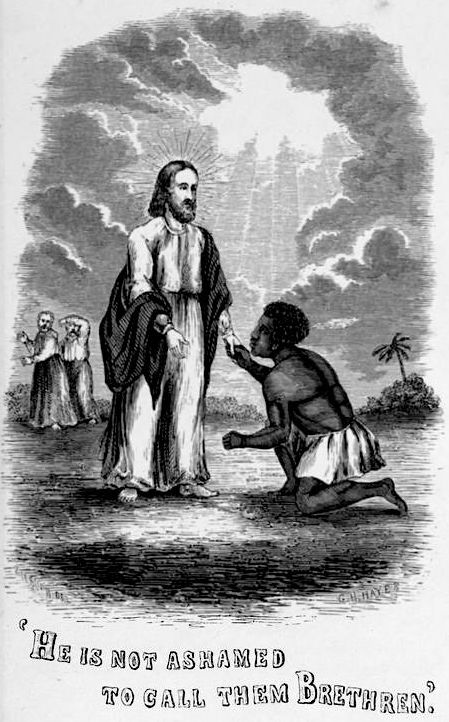

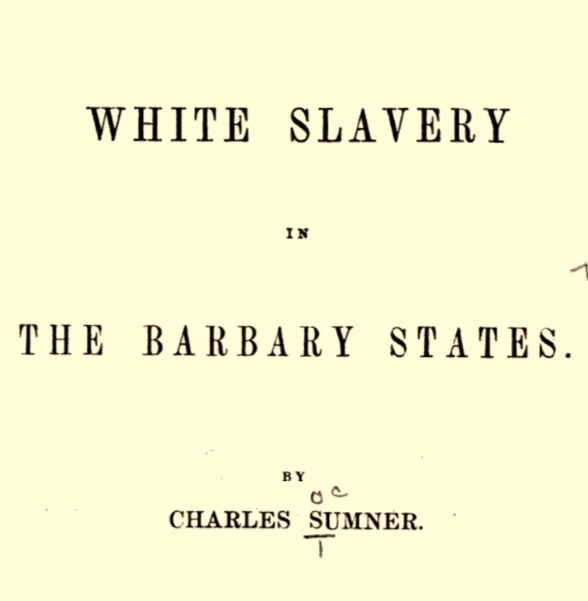

This context of the ignoble savage (to turn a popular phrase) places Columbus as one offering an actual advancement in civilization when compared to the atrocities discovered by the explorers. Charles Sumner, the renowned abolitionist Senator from the mid-1800’s, explained that the context of comparative cultures allows the historian to ascertain whether or not interactions and exchanges were beneficial or detrimental to the overall cultivation of morality. Even practices which all today condemn might have at an earlier time represented a significant advancement. He uses slavery, the very institution he spent his life fighting, as an example:

The merchandise in slaves will be found to have contributed to the abolition of two hateful customs;…eating of captives, and their sacrifice to idols. Thus, in the march of civilization, even the barbarism of slavery is an important stage of Human Progress. It is a point in the ascending scale from cannibalism.7

Such a point is self-evident. In the age of conquest victorious groups had limited options concerning the fate of defeated opponents. In the ancient world, and more recently in less developed areas, the only conclusions for those on the losing side of a conflict were slaughter, sacrifice, cannibalism, or some other similarly unfortunate end. Once civilization reached a point of sufficient stability nations could support allowing captured warriors and civilians live as slaves or tributaries. Instead of killing those who did not die in the conflict, they were used to pursue economic advancement through either forced labor or trade with other nations. Thus, Sumner rightly notes that even atrocities such as slavery at least marks a step up from the greater depravity of murdering, sacrificing, or eating the captives.

Such a progression finds itself distinctly expressed in Columbian exchange of morality in the years following the discovery of the New World. Setting aside the actions of the Spanish rebels, later corrupt magistrates, and false ministers who disguised themselves as apostles of Christ, the clear record is that the original evangelistic centered plan for colonization presented by Columbus, commissioned by the Sovereigns, and confirmed by the Pope planted the seeds of a more progressive moral society. [To learn more about the evangelistic vision of Columbus read this article.]

When examined in the wider context, Columbus acted more to advance the virtues of liberty and equality than not. Situated next to the robust system of slavery and oppression existing in America prior to the arrival of the Europeans, Columbus’s efforts against the cannibalistic slave-driven tribes at the behest of the more peacefully inclined tribes (who also owned slaves) led to the liberation of many women, children, and men. Although it is a fact often overlooked, this allows the historian to frame the effects of Columbus’s voyages and subsequent colonization in the proper context. Of course, none of this is to suggest that Columbus was perfect—by no means. It does, however, show that he first planted the seeds of freedom on American shores which would eventually germinate into the nation which brought more liberty, stability, and prosperity than any other country in the history of the world.

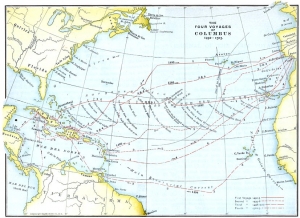

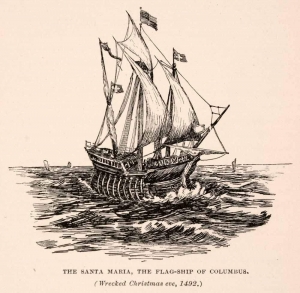

The arrival of Christopher Columbus and his three diminutive ships laden with tremendous potential was an anthropologist’s dream. In 1492 Columbus encountered and documented for the first time the Taino people within the larger Arawak language group. Without Columbus and his efforts we would have no records of these cultures at all. While this tribe is largely considered to be the most civil out of all the native tribal groups encountered by the early Spanish explorers it does not hide the fact that they too participated in conquest, colonization, and slavery.

The arrival of Christopher Columbus and his three diminutive ships laden with tremendous potential was an anthropologist’s dream. In 1492 Columbus encountered and documented for the first time the Taino people within the larger Arawak language group. Without Columbus and his efforts we would have no records of these cultures at all. While this tribe is largely considered to be the most civil out of all the native tribal groups encountered by the early Spanish explorers it does not hide the fact that they too participated in conquest, colonization, and slavery.

Columbus himself had strong relations with their chief, Guacanagari, throughout their lives. His admiration for the Taino went so far as to cause Columbus to exclaim that, “a better race there cannot be, and both the people and the lands are in such quantity that I know not how to write it.”8 Such commendations might suggest that the Taino were without blemish but Columbus was soon to see examples of how that was not the case. Even Columbus could not fail to note how, “the natives make war on each other, although these are very simple-minded and handsomely-formed people.”9

The Taino, just like nearly any other people group or culture, did not themselves enter into an “empty wilderness.” The islands they occupied were conquered from the earlier Siboney culture group. Respected naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison (noted for his leadership of the 1939 Harvard Columbian Expedition which sailed the routes of Columbus’s voyages based off the information provided in his journals) explains that:

Colonization, we must remember, is merely one form of conquest…which the ancestors of our Indians had practiced in the New World for several millennia before the first conquistador appeared from Castile. Even the Taino people of the Antilles, whom Columbus reported to be gentle, peaceable, and defenseless, had conquered the Bahamas and most of Cuba from the more primitive Siboney during the fifteenth century.10

Shockingly, the Taino conquest of the Siboney tribe was so total and complete that in all of the recorded observations of Columbus he only ever encountered one Siboney survivor.11 This amounts to nothing less than a relentless Taino invasion. Such a statistical annihilation of a people group equals and even outstrips some of the highest estimates of the destruction of the Taino population due to exposure to the European diseases their immune systems were so unequipped for.12

Expanding to a wider view of the pre-Columbian world, cycles of conquest, subjugation, and decimation were not uncommon and, “one could legitimately argue that for many Amerindian people the expansion of the Huari, Aztec, and Inka empires was equally cataclysmic,” when compared to that following the appearance of the Europeans.13 The idea that Columbus and the Europeans brought the idea of war to a previously untouched and unblemished culture is historically bankrupt and unfounded on anything except ideological agenda.

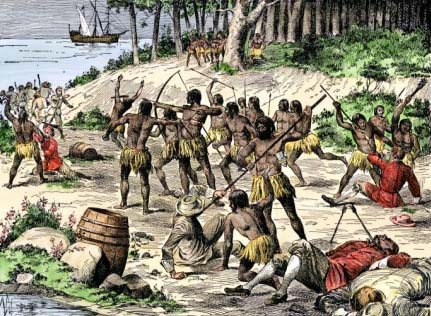

One example from the history of Ferdinand Columbus offers a pointed perspective into this newly discovered culture. He documents the tragedy of the first large confrontation between a hostile force and the coalition forces led by Columbus consisting of the Spaniards and allied tribes marshaled by Guacanagari. In an earlier attack upon the Spanish outpost and the allied Indian village one of his wives was murdered and another one captured to be thereafter enslaved to the victorious chieftain. “And that was why he now appealed to the Admiral to restore his wife to him and help him get revenge for his injuries.”14 The battle is a major success for the coalition forces, and the Spanish’s technological superiority bolstered by the Taino’s numerical assistance routed the enemy army. Not only were Columbus and Guacanagari successful in reclaiming his enslaved wife, but they also captured the offending chief and all of, “his wives and children.”15

One example from the history of Ferdinand Columbus offers a pointed perspective into this newly discovered culture. He documents the tragedy of the first large confrontation between a hostile force and the coalition forces led by Columbus consisting of the Spaniards and allied tribes marshaled by Guacanagari. In an earlier attack upon the Spanish outpost and the allied Indian village one of his wives was murdered and another one captured to be thereafter enslaved to the victorious chieftain. “And that was why he now appealed to the Admiral to restore his wife to him and help him get revenge for his injuries.”14 The battle is a major success for the coalition forces, and the Spanish’s technological superiority bolstered by the Taino’s numerical assistance routed the enemy army. Not only were Columbus and Guacanagari successful in reclaiming his enslaved wife, but they also captured the offending chief and all of, “his wives and children.”15

This episode provides an exemplary source text for evidencing several major aspects prevalent in the native cultures encountered by Columbus. First and most obvious (although often overlooked by popular “bottom up” historians such as Zinn), is the existence of war between the various tribes which clearly existed prior to European discovery. As discussed earlier, even the presence of Guacanagari and his relatively peaceful Taino subjects upon the islands explored by Columbus would not have been possible but for the previous conquest and near complete extinction of the earlier occupying inhabitants.

Second, it shows that both indigenous sides practiced polygamy. Early missionary Fray Ramon Pane, “a modest and loyal Jeronymite who was doing his best to serve God instead of mammon,”16 remarked how polygamy was the standard practice amongst the vast majority of natives. It was only the introduction of Christianity which caused many to abandon the practice. The conversion of leading chieftain named Mahuviativire illustrates this perfectly. The missionary reported that the chieftain, “for three years now has continued to be a good Christian, keeping only one wife, although the Indians are accustomed to have two or three wives, and the principal men up to ten, fifteen, and twenty.”17 If men are commonly permitted to marry twenty women, one ought to question what exactly Howard Zinn considers a “beautifully worked out” society.

Lastly, it offers a glimpse into the widespread enslavement of the members of other tribes—principally women and children—through raids and conquest. In fact, when Columbus first landed on October 12th, 1492, he learned from the Taino themselves that they were often attacked, carried away, and enslaved by other tribes who preyed upon their weakness. The Admiral notes in his journal that he:

Saw some with marks of wounds on their bodies, and I made signs to ask what it was, and they gave me to understand that people from other adjacent islands came with the intention of seizing them, and that they defended themselves. I believed, and still believe, that they come here from the mainland to take them prisoners.18

Although Columbus’s initial interpretation is wrong as to who the perpetrators were, the Taino’s description of defending themselves against the savage attacks from an outside group of aggressive natives provided Columbus with his first introduction to the ways of the Carib people.

Placed next to the relative timidity and gentleness of the Taino, the Carib tribes appear quite warlike and barbaric. These indigenous peoples (from whose name we derive both the words “Caribbean” and “cannibal”) terrorized the Taino through constant raids and attacks. It was of the Carib tribes that, the Taino warned Columbus about during the first voyage, speaking of a civilization of, “extremely ferocious…eaters of human flesh” who “visit all the Indian islands, and rob and plunder whatever they can.”19 The Caribs were so effective that in 1494, after the second voyage, it was published in Europe that many of:

The Islands explored on the voyage last year are exposed to Carib invasions. One or two Caribs can often rout a whole company of Indians [i.e. Taino]. The Indians are so much in awe of the Caribs that they tremble before them even if they are securely tied.20

This author, Nicolo Syllacio, continues to relate the observations of crew member Peter Margarita concerning the Carib culture, explaining how:

These islands are inhabited by Canabilli, a wild, unconquered race which feeds on human flesh. I would be right to call them anthropohagi [man-eaters]. They wage unceasing wars against gentle and timid Indians to supply flesh; this is their booty and is what they hunt. They ravage, despoil, and terrorize the Indians ruthlessly, devouring the unwarlike, but abstaining from their own people.21

Such descriptions might be easily considered as European inventions in order to justify conquest and thereby discounted if not for the fact that the testimony from the Taino Indians confirms Syllacio’s account and many other eyewitnesses provide corroborating reports. Additionally, the Caribs themselves confessed that they were indeed cannibalistic.22

Another crew-member and childhood acquaintance of Columbus, Michele de Cuneo, similarly records the barbarity of Carib culture discovered in the New World. He explains that the Caribs would spend up to a decade plundering any particular island until they completely depopulated it through slavery and cannibalism. He writes that:

The Caribs whenever they catch these Indians eat them as we would eat kids and they say that a boy’s flesh tastes better than that of a woman. Of this human flesh they are very greedy, so that to eat of that flesh they stay out of their country for six, eight and even ten years before they repatriate; and they stay so long, whenever they go, that they depopulate the islands.23

The complete and deliberate depopulation of entire islands and communities by a dominate and oppressive culture very well can be defined as genocide through cannibalism—certainly much more than anything which Christopher Columbus ever did.

The complete and deliberate depopulation of entire islands and communities by a dominate and oppressive culture very well can be defined as genocide through cannibalism—certainly much more than anything which Christopher Columbus ever did.

Additionally, this was far from an isolated incident recorded second hand. Cuneo, along with many others, were eye-witnesses to the tragic aftermath of Carib raids and what often happened to those the attackers chose to keep alive. Upon landing at a village of Carib slaves, Cuneo recalled that the now liberated group included:

Twelve very beautiful and very fat women from 15 to 16 years old, together with two boys of the same age. These had the genital organ cut to the belly; and this we thought had been done in order to prevent them from meddling with their wives or maybe to fatten them up and later eat them. These boys and girls had been taken by the above mentioned Caribs.24

The truth is clearly different than the egalitarian society promoted by “bottom up” historians. A society which conquers, captures, cannibalizes, and enslaves neighboring tribes, subjecting captured inhabitants to physical mutilation and sexual servitude is certainly not a place, “where the relations among men, women, children, and nature were more beautifully worked out than perhaps any place in the world.” 25 None of the European nations, for all their faults, engaged in anything similar to what was happening in the New World.

Other witnesses corroborate what Cuneo saw, explaining how the Caribs:

Other witnesses corroborate what Cuneo saw, explaining how the Caribs:

In their wars upon the inhabitants of the neighboring islands, these people capture as many of the women as they can, especially those who are young and handsome, and keep them as body servants and concubines.26

One of the medical experts further described how the captive men and boys were neutered in order to prepare them for consumption later, saying:

When the Caribbees take any boys as prisoners of war, they remove their organs, fatten the boys until they grow to manhood and then, when they wish to make a great feast, they kill and eat them, for they say the flesh of boys and women is not good to eat.27

This treatment is similar to the castration of cattle designated for market across the world today. Castrating calves at a young age serves, “to prevent reproduction and simplify management, but, most importantly, cattle are castrated to improve marbling and tenderness of the finished beef.”28 Similar motivations seemingly led the Caribs to mutilate their male captives.

The medical expert on the early voyages, Dr. Diego Chanca, while originally unsure about the veracity of reports concerning Carib cannibalism from the Taino, confirmed them once he arrived in the Indies. Dr. Chanca recalls an incident when one of the shore party:

Brought away with him four or five bones of human arms and legs. When we saw those bones we immediately suspected that we were then among the Caribbee islands, whose inhabitants eat human flesh, because the admiral, guided by the information respecting their situation he had received from the Indians of the islands he had discovered during his former voyage, had directed the course of our ships with a view to find them.29

The discovery of bones which have been cannibalized marks the first example of physical evidence of cannibalism. Another crew-member on a journey to a local chieftain remarked that, “the royal residence which stood on a flat-topped hill where there was a large plaza whose stockade was decorated with 300 heads of the men he had killed in battle.”30 Such archeological evidence confirms the Taino testimony and Carib confessions written down by the earliest of explorers. Recently too, bones and cannibalized remains have been discovered which independently confirms the overwhelming uniformity of both European and indigenous sources.31

As noted above, when the Europeans landed on Carib islands they discovered entire villages of enslaved women and mutilated men. Whenever Columbus and his crew landed and began exploring the village the slaves began fleeing to the Europeans seeking refuge from their captors and transport back to their homes. In a second village even more gruesome scenes were witnessed. By the time they left over twenty women and three men were liberated by Columbus and his men.32 Dr. Chanca described that the Caribs enslaved so many women that, “in fifty houses we entered no man was found, but all were women.”33

After the Europeans explained to the enslaved Taino that they themselves were not cannibals, “they felt delighted.”34 The liberated women began to explain to the doctor that:

The Carribbee men use them with such cruelty as would scarcely be believed; and that they eat the children which they bear to them, only bringing up those which they have by their native wives.35

This system of enslavement, sexual subjugation, and then the cannibalism of the offspring is nearly unprecedented in world history. Being now led by the freed Taino Indians, the explored found in the villages ample proof of their stories:

For of the human bones we found in their houses everything that could be gnawed had already been gnawed, so that nothing else remained of them but what was too hard to be eaten. In one of the houses we found the neck of a man undergoing the process of cooking in a pot, preparatory for eating it.36

In total, the evidence reveals that the Carib tribes consisted of a culture dependent upon slave labor and human servitude derived from extended campaigns of conquest. One of the crew members on the second voyage even remarked how, “The women do all the work. Men only mind fishing and eating.”37 Anthropologist Fernando Santos-Granero rightly summarizes that the Caribs subsisted through the “large-scale raiding” of Taino tribes where:

Female and children captives were turned into concubines and slaves, whereas adult males were killed and partly eaten in cannibalistic rituals that brought together members of different villages and sometimes the population of entire islands.38

The world Columbus discovered is widely different than the view recently presented. In the vast majority of modern biographies and evaluations of Columbus and the entire age of exploration overlooks the context into which their actions were situated. They look at the failures of Columbus to stop slavery altogether and miss the fact that he was engaged in the widespread liberation of enslaved women. They see how he went to war against some of the natives without considering how he was asked to by his ally Guacanagari to avenge one wife who had been murdered and retrieve another who had been stolen. In short, they judge Columbus as if he landed upon the shores of America today and not five hundred years ago. To judge a historical figure or action divorced from the age and context presents an incomplete fact pattern leading to an improper and historically deficient conclusion.

At this juncture an objection might be raised that the European sources are unreliable due to their biases against the natives and the benefit which would arise from painting at least certain segments of the native population as barbaric beyond belief. However, to discount the European sources merely because they are European upon the pretense that they might have something of prejudice or bias in them is intrinsically anti-historical in its nature and execution. Every source or document represents a historical action imbued with native prejudices and perspectives, but the existence of such in the sources in no way disproves the reliability of them.

Like any inquiry, historical and modern, the truth is established through the preponderance of the evidence in one way or the other. Noted scholars have explained that, “Denying the possibility of learning about the history of Amerindian societies using European sources would be tantamount to denying the possibility of knowing the history of any people through any kind of source.”39 Through the collection of corroborating testimony, documentation, and sources a picture of the historical past can be reliably constructed, and for it to be an honest representation the first-generation European writings as they recorded what they themselves witnessed in their travels must be included.

However, if the contextual scope is expanded to include not just the island cultures encountered by Columbus but also to the other nearby tribes in the Mesoamerican regions such as Central and South America, it reveals that reports of cannibalism, slavery, and related actions are not the imaginations of a few biased Europeans but the actuality of a larger cultural trend existent in indigenous American societies.

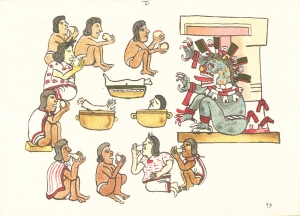

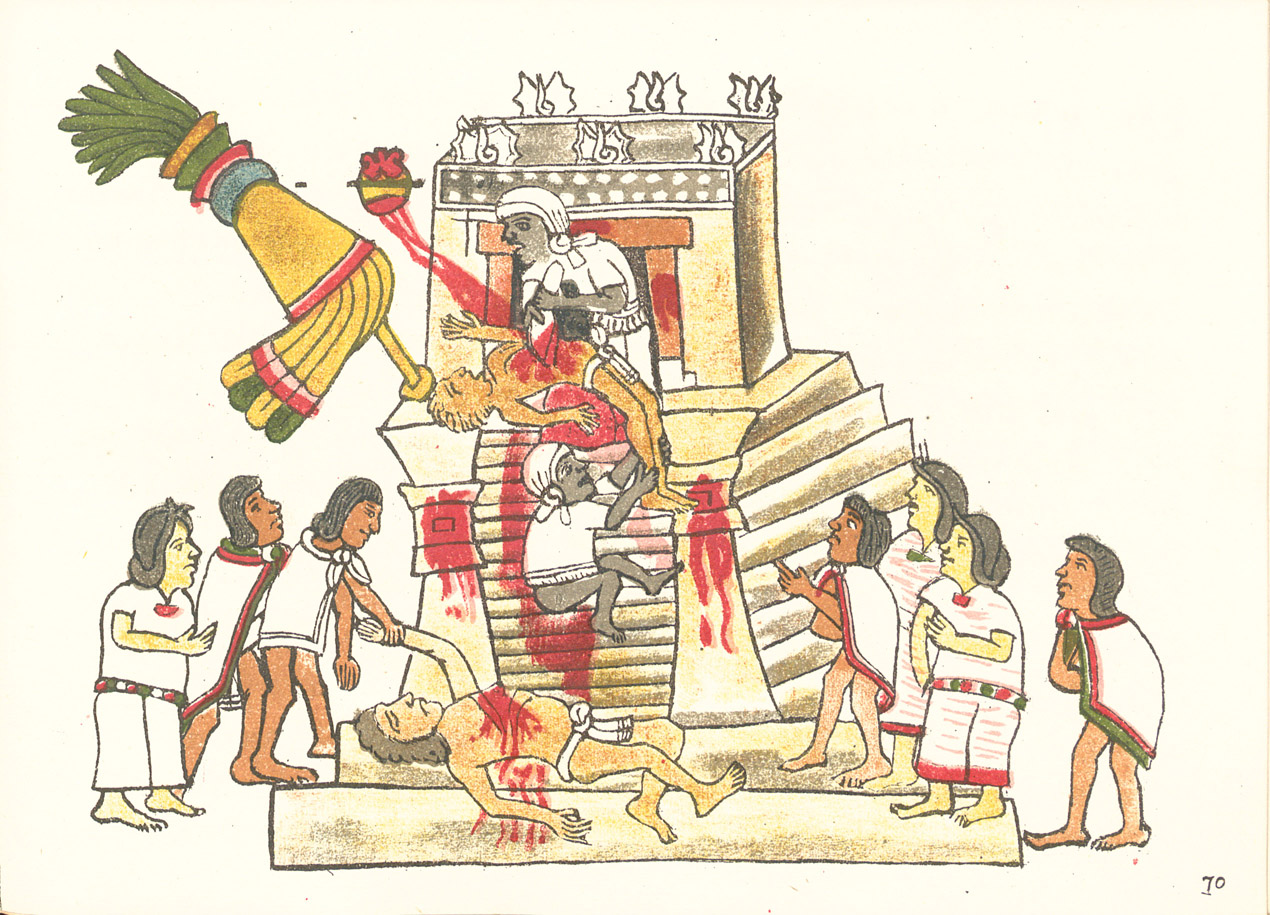

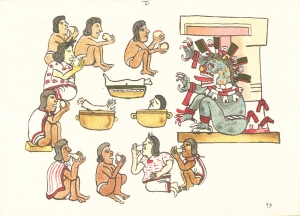

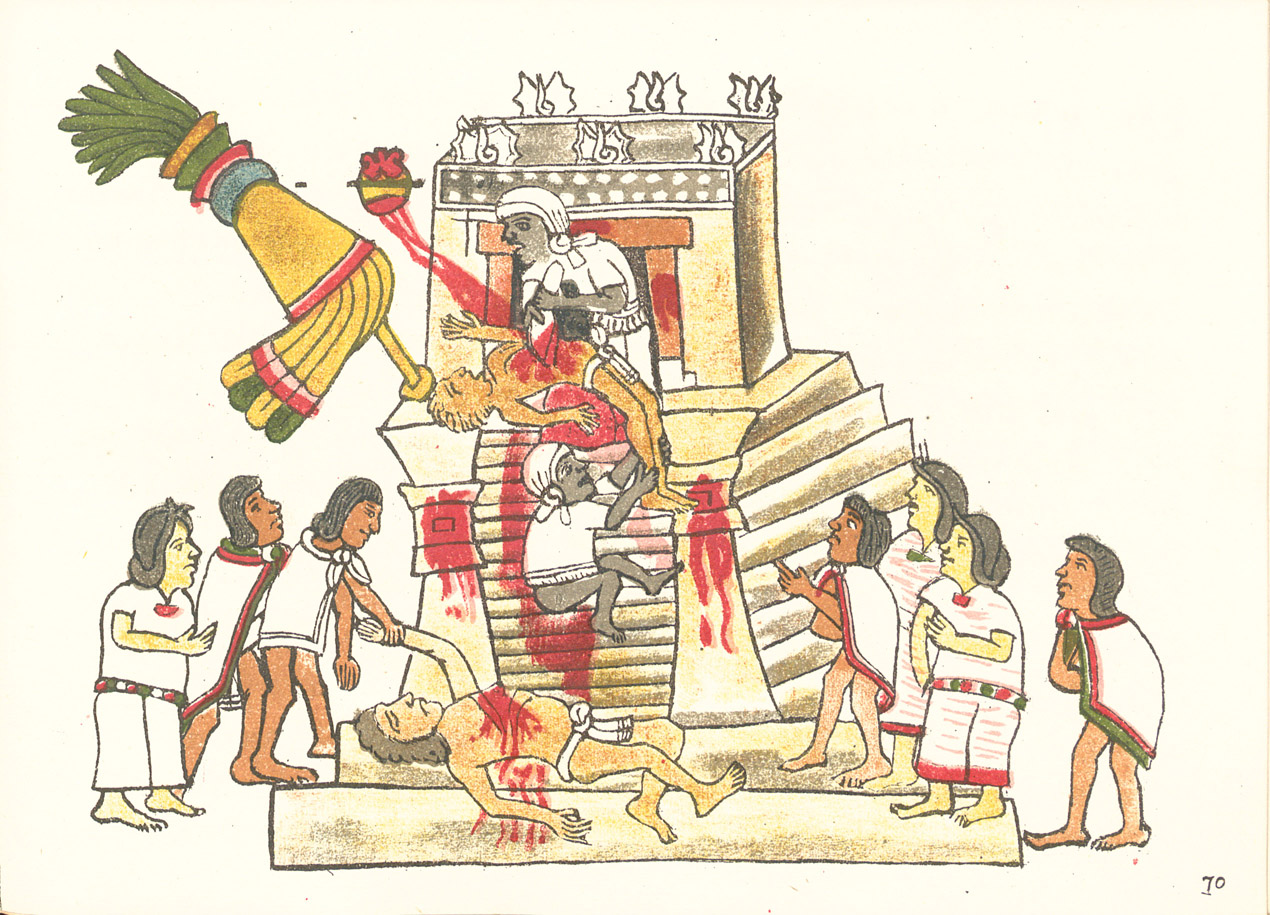

The most famous examples of similar atrocities are those of the Aztecs, of which Zinn only acknowledges to remark, “the cruelty of the Aztecs, however, did not erase a certain innocence.”40 With some explorers seeing skull walls with nearly 100,000 pieces and the largest recorded instance of mass sacrifice including up to 80,000 victims at the dedication of the temple at Tenochtitlan in 1487, it appears an odd expression of “certain innocence.”41 Most victims were slaves captured in raids and wars or even their own children in some instances. Of course, the Aztecs were not alone in such practices although they were probably the most liberal. Indeed, in the indigenous societies, “Some type of death sacrifice normally accompanied all important rituals.”42 The method of sacrifice varied considerably, including:

The standard method of gashing open the chest with a stone knife and ripping out the heart, decapitation (especially for female victims), shooting with atlatl darts or arrows, the “gladiatorial sacrifice,” burning nearly to death—the coup de grace delivered by heart extraction, drowning, hurling from a height, smashing against a hard surface, strangulation, shutting up and starving to death.43

After the slaves were murdered often their hearts were extracted if that had not already been done. The skulls were then removed, prepared, and placed within the ever-growing skull racks or other similar repositories. Lastly the carcasses of the now decapitated and heartless victims were taken and consumed in a ritualistic feast.

The Huastec civilization serve as another example of the general trend within the central Mexican cultures which engaged in widespread subordination of weaker tribes and the sacrifice of those conquered peoples. The excavated pottery from the area depict the common heart extraction style of sacrifice similar to the example shown on the early codices from other regions such as Codex Magliabechiano.44 The Huastec also sacrificed their slaves through a process known as flaying which included the skinning and preservation of the victims faces and sometimes bodies, afterwards cannibalizing the remains.45 Similarily, slave sacrifices to the Mexican god Xipe consisted of the typical heart extraction offering and then the flaying of the entire human body to be worn by anyone, “wishing to show special devotion to the god.”46

The Huastec civilization serve as another example of the general trend within the central Mexican cultures which engaged in widespread subordination of weaker tribes and the sacrifice of those conquered peoples. The excavated pottery from the area depict the common heart extraction style of sacrifice similar to the example shown on the early codices from other regions such as Codex Magliabechiano.44 The Huastec also sacrificed their slaves through a process known as flaying which included the skinning and preservation of the victims faces and sometimes bodies, afterwards cannibalizing the remains.45 Similarily, slave sacrifices to the Mexican god Xipe consisted of the typical heart extraction offering and then the flaying of the entire human body to be worn by anyone, “wishing to show special devotion to the god.”46

The New World was one filled with the old ways of colonization, conquest, and slavery. Before any European arrived upon the shores of Cuba or Puerto Rico entire civilizations were being destroyed by invading armies. Women were enslaved and abused to produced children to satisfy the hunger of their cannibalistic masters. Young boys were captured and castrated before being fattened and served during special feasts. From the Taino to the Caribs to the Aztecs, the Europeans witnessed a world where slavery was widespread and those unfortunate enough to be captured were viciously abused. Slavery in the pre-Columbian world was so prevalent that somewhere between twenty to forty percent of all Indians were enslaved people.47

Overall, the world which Christopher Columbus discovered is radically different from the human egalitarian society presented by the modern revisionist writings on the subject. Academics like Zinn and Lynd begin from the assumption that America was founded upon crimes committed against the Indians by the European explorers and colonists and ignore any data which suggests the opposite. In their intellectual expedition to do “history from the bottom up” they are never able to tell the history of those truly at the bottom. They stop short of the women enslaved and abused by the Caribs and liberated by Columbus. In their desire to prove the American founding evil they ignore the wider context surrounding the voyages. The facts do not validate their philosophy. The evidence simply does not fit with the “highly egalitarian ideologies and practices,” promoted by Zinn.48 In order to give a voice to their own activism they silence the voice of the women enslaved by the Caribs or the thousands sacrificed upon Aztec alters.

Overall, the world which Christopher Columbus discovered is radically different from the human egalitarian society presented by the modern revisionist writings on the subject. Academics like Zinn and Lynd begin from the assumption that America was founded upon crimes committed against the Indians by the European explorers and colonists and ignore any data which suggests the opposite. In their intellectual expedition to do “history from the bottom up” they are never able to tell the history of those truly at the bottom. They stop short of the women enslaved and abused by the Caribs and liberated by Columbus. In their desire to prove the American founding evil they ignore the wider context surrounding the voyages. The facts do not validate their philosophy. The evidence simply does not fit with the “highly egalitarian ideologies and practices,” promoted by Zinn.48 In order to give a voice to their own activism they silence the voice of the women enslaved by the Caribs or the thousands sacrificed upon Aztec alters.

After being elected as President of the United States of America, Theodore Roosevelt was elected to be the president of the American Historical Association. In his 1912 inaugural address he explained how many times historians abandon objectivity in their quest to appear neutral. President Roosevelt argues that:

The greatest historian should also be a great moralist. It is no proof of impartiality to treat wickedness and goodness as on the same level.49

So much of the Columbus question in modern America revolves around whether or not he can be considered a good person or even a hero. The failure to situate him with his proper context has already been addressed, but now after reviewing much of the available evidence what can be said about Columbus’s effect upon the moral development of the New World? How did the Columbian exchange affect the morality of the New World, and was it an improvement? Did it, as Sumner suggested, provide an ascending point upon the chain of human progress or not?

The answer to this is an unqualified yes. The sum total effect of Columbus’s discovery of America ultimately brought about a vast improvement in the cultural morality existent in the Caribbean and Central American regions. Such a conclusion, of course, is not to justify the terrible savageness of some of the Spaniards and other colonists which followed Columbus later. Much rather it is simply to acknowledge the fact that no matter what else happened, never again was the Western hemisphere to see the sacrifice of 80,000 victims in a single day or the existence of baby mills for the purpose of infant cannibalism. Even in 1860 the overall percentage of slaves in the United States was less than it was in many of the ingenious societies.

The overarching story of American discovery and colonization is one of progress and advancement. Of mankind piercing the mist of the Ocean Sea to plant the seeds of individual rights, liberty, and freedom on a faraway shore so that they could finally germinate and grow, providing its fruit to the world both Old and New. However, when historians isolate the actions of Columbus from the wider cultural context, that story of human progress and the ever-developing refinement of civilization is lost amidst the fog of fable.

The fabrication of Zinn—that the indigenous peoples were a more morally advanced society with greater equality and beneficence between the genders and classes—is helpful for certain ideological agendas but not for serious historical inquiries. The truth demonstrated above show just how less developed the native cultures were in areas of social rights and cultural ethics as compared to the explorers and discoverers coming from Europe. Obviously, such facts do not and cannot serve as a kind of justification for the documented failures and shortcoming of those coming from the Old World. If an expedition of modern men journeyed back to anywhere in the world in 1492. The modern sensibilities of right and wrong would be mortified, having gone through several centuries of refinement since the days of Columbus and Guacanagari. Both the illiberality of the Spanish religious code and the rampant slavery of the Taino and Caribs would shock the moderns. All have sinned and fallen short of the whatever standards the modern historian or moralist might try to retroactively apply to the past. Columbus himself recognized the need to be judged in context by those who understood the times, writing:

I ought to be judged as a captain, who for so many years has borne arms, never quitting them for an instant. I ought to be judged by cavaliers who have themselves won the meed of victory; by knights of the sword and not of title deed.50

Thus, in a study of Columbus and the past we must become a “knight of the sword” and not merely of a “title deed.”

1 Carol Delany, Columbus and the Quest for Jerusalem (New York: Free Press, 2011), xii.

2 Focusing primarily on English and American reception and interpretation of Christopher Columbus, the orthodox view of a more heroic and honorable Columbus begins with William Robertson, The Discovery and Settlement of America (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1828; 1st ed. London, 1777); Jeremy Belknap, A Discourse Intended to Commemorate the Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus (Boston: Belknap and Hall, 1792); William Grimshaw, History of the United States (Philadelphia: John Grigg, 1826); Charles Goodrich, A History of the United States of America (Hartford: D. F. Robinson & Co., 1829); the most complete synthesis of the first wave orthodox understanding of Columbus being found in Washington Irving, The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (London: John Murray, 1828). The typical orthodox trend largely continued with the second wave of scholarship in the mid to late 19th century with examples including S. G. Goodrich, A Pictorial History of the United States (Philadelphia: E. H. Butler, 1843); Thomas D’Arcy McGee, Catholic History of North America (Boston: Patrick Donahoe, 1855); Joel Dorman Steele, A Brief History of the United States for Schools (New York: A. S. Barnes & Company, 1871); and Horace A. Scudder, A History of the United States of America (Philadelphia: J. H. Butler, 1884). There are few early examples of the debunking and revisionist tendencies but on a whole, these were seen as novelties and had negligible influence on the overall dialogue, see W. L. Alden, Christopher Columbus (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1881); and Aaron Goodrich, A History of the Character and Achievements of the So-Called Christopher Columbus (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1874). More progressive interpretations of Columbus starting appearing more seriously with works including William Giles Nash, America: The True History of Its Discovery (London: Grant Richards Ltd., 1924); Emerson Fite, History of the United States (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1929); and Wilbur Fisk Gordy, History of the United States (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1929). However, such examples still failed to turn the tide of both popular perception and academic tendency towards orthodoxy, the overwhelmingly standard and influential biography from Morison examples this, see Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1942). The revisionist and progressive movements began to dominate the discussion during the 1960’s as a spirit of activism spread throughout the academy with works such as, Edward Stone, “Columbus and Genocide” in American Heritage 16 (October 1965); Bernard A. Weisberger, The Impact of Our Past: A History of the United States (New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., 1972); and Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper & Row, 1980).

3 Staughton Lynd, Doing History from the Bottom Up: On E. P. Thompson, Howard Zinn, and Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014), xii.

4 Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Collins, 2015), 21.

5 “The 1619 Project,” The New York Times (accessed September 13, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html.

6 Fernando Santos-Granero, Vital Enemies: Slavery, Predation, and the Amerindian Political Economy of Life (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 1.

7 Charles Sumner, White Slavery in the Barbary States (Boston: William D. Ticknor and Company, 1847), 11.

8 Christopher Columbus, The Journal of Christopher Columbus, translated by Clements Markham (London: Hakluyt Society, 1893), 131.

9 Ibid., 42.

10 Samuel Eliot Morison, “The Earliest Colonial Policy Toward America: That of Columbus,” Bulletin of the Pan American Union 76, no. 10 (October, 1942), 543.

11 Samuel Eliot Morrison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1942), 464.

12 For a brief statistical overview of the decline in indigenous populations see, Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North America (New York: Penguin Publishing, 2001), 38.

13 Santos-Granero, Vital Enemies, 6-7.

14 Ferdinand Columbus, The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus, translated by Benjamin Keen (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 148-149.

15 Ibid., 149.

16 Morrison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, 484.

17 Fray Ramon Pane quoted in, Ferdinand Columbus, The Life of the Admiral, 168.

18 Columbus, The Journal, 38.

19 Christopher Columbus, “Letter sent by Columbus to Chancellor of the Exchequer, respecting the Islands found in the Indies,” in Select Letters of Christopher Columbus (London: Hakluyt Society, 1870), 14.

20 Nicolo Syllacio, “Syllacio’s Letter to Duke of Milan, 13 December 1494,” in Journals and Other Documents on the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, edited by Samuel Eliot Morrison (New York: The Heritage Press, 1963), 237.

21 Ibid., 233-234.

22 Ibid., 235.

23 Michele de Cuneo, “Michele de Cuneo’s Letter on the Second Voyage, 28 October 1495,” Journals and Other Documents on the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, edited by Samuel Morrison (New York: Heritage Press, 1963), 219.

24 Ibid., 211-212.

25 Zinn, A People’s, 21.

26 Diego Chanca, “Letter of Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca,” Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1907), Vol. 48, 442.

27 Ibid.

28 Boone Carter, Castrating Beef Calves: Age and Method (Las Cruces: New Mexico State University, 2011), 1.

29 Chanca, “Letter of Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca,” 436.

30 Diego Mendez, “The Will of Diego Mendez,” in The Journal and Other Documents on the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, edited by Samuel Eliot Morison (New York: The Heritage Press, 1963), 389.

31 Sabrina Valle, “Cannibalism Confirmed Among Ancient Mexican Group,” National Geographic, October 1, 2011, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/11/110930-cannibalism-cannibals-mexico-xiximes-human-bones-science/ (accessed October 6, 2019).

32 Chanca, “Letter of Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca,” 442.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid., 440.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Cuneo, “Michele de Cuneo’s Letter,” 220.

38 Santos-Granero, Vital Enemies, 20.

39 Ibid., 12.

40 Zinn, A People’s History, 11.

41 Herbert Burhenn, “Understanding Azte Cannibalism,” Archiv Für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion 26 (2004), 1.

42 Henry B. Nicholson, “Religion in Pre-Hispanic Central Mexico,” Handbook of Middle American Indians: Archaeology of Northern Mesoamerica (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1971), Vol. 10, 432.

43 Ibid., 432-433.

44 The Book of the Life of the Ancient Mexicans, Translated by Zelia Nuttall (Berkeley: University of California, 1903), 70.

45 Guy Stresser-Pean, “Ancient Sources on the Huasteca,” Handbook of Middle American Indians: Archaeology of Northern Mesoamerica (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1971), Vol. 11, 598.

46 H. R. Harvey, “Ethnohistory of Guerrero,” Handbook of Middle American Indians: Archaeology of Northern Mesoamerica (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1971), Vol. 11, 613.

47 Santos-Granero, Vital Enemies, 226-227.

48 Ibid., 4.

49 Theodore Roosevelt, History as Literature and Other Essays (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 19.

50 Christopher Columbus, “Letter of the Admiral to the (quondam) nurse of the Prince John, 1500,” Select Letters of Christopher Columbus (London: Hakluyt Society, 1870), 170.

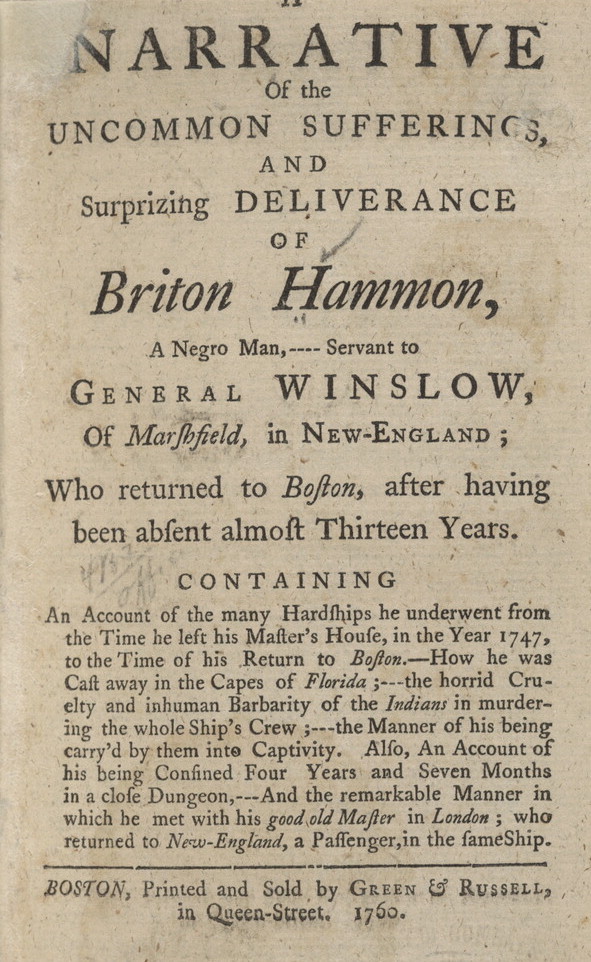

In 1760 America became the first nation to publish a work of prose by a writer of African descent.

In 1760 America became the first nation to publish a work of prose by a writer of African descent.

Having now been liberated from Spanish slavery, Briton arrived in England and signed up for the British navy, fighting in several naval battles before being wounded. After an honorable discharge from the service, he continued to hire himself out on numerous voyages eventually signing up for a voyage to Guinea.

Having now been liberated from Spanish slavery, Briton arrived in England and signed up for the British navy, fighting in several naval battles before being wounded. After an honorable discharge from the service, he continued to hire himself out on numerous voyages eventually signing up for a voyage to Guinea.

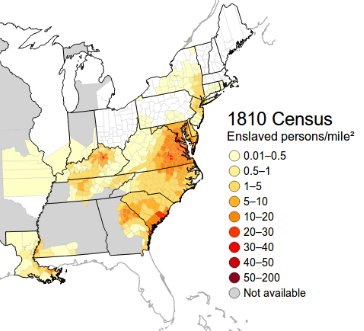

The 1810 census documented that the total population of those states—Massachusetts (Maine included), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey—stood at 3,486,675.

The 1810 census documented that the total population of those states—Massachusetts (Maine included), New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey—stood at 3,486,675.

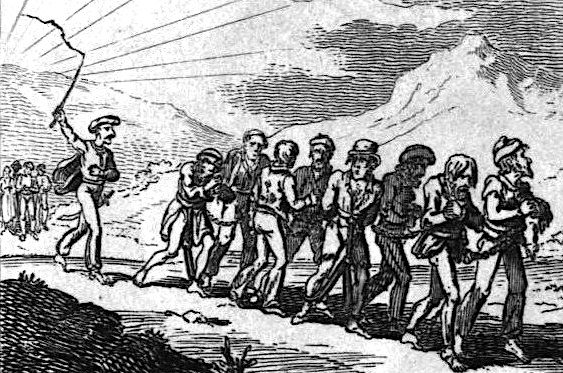

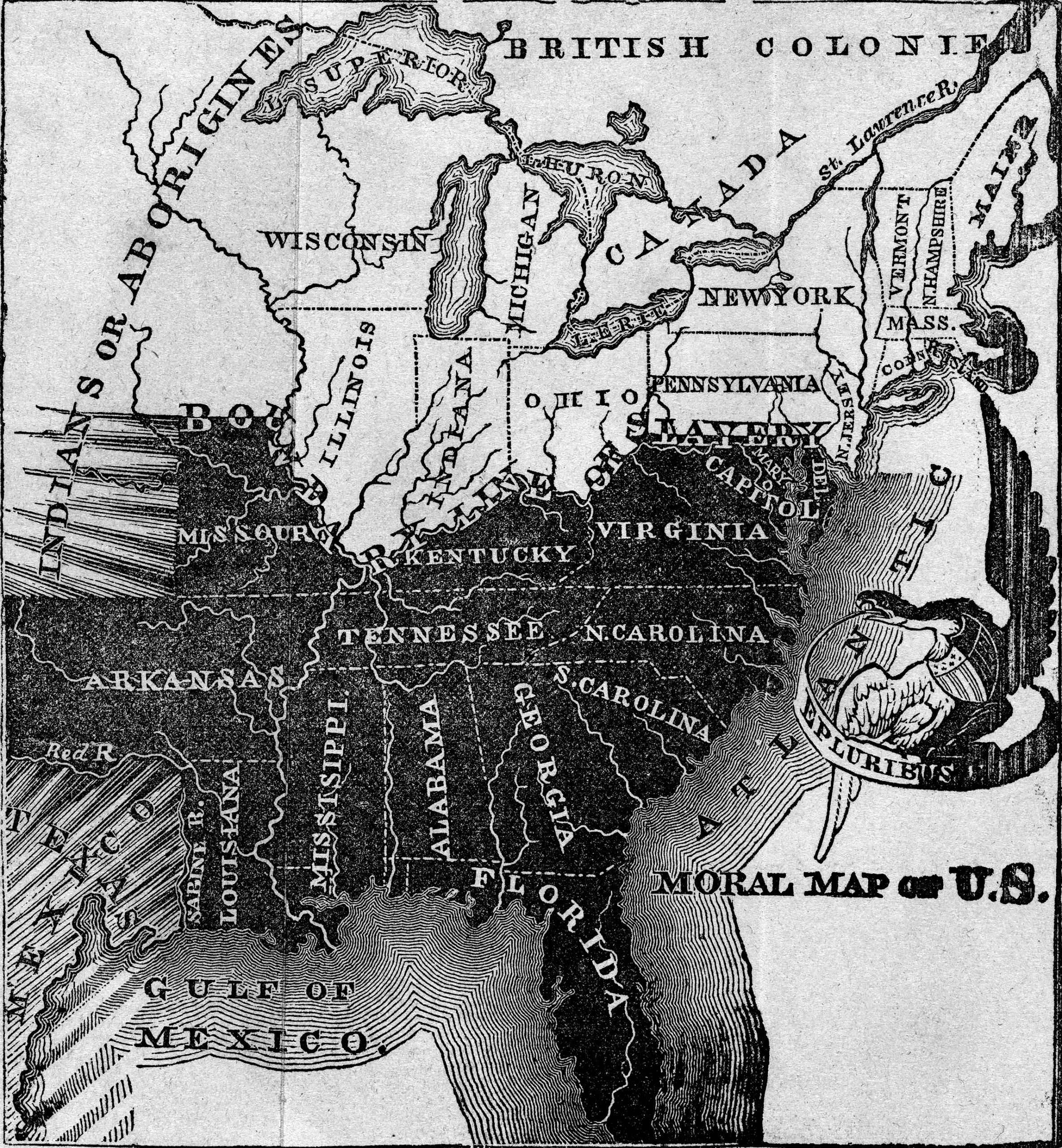

What is more, slavery both globally and in America was never simply white on black. Just as every people group has owned slaves, every people group has correspondingly been enslaved. Prior to the 1700s there were more white slaves globally than there were black slaves.

What is more, slavery both globally and in America was never simply white on black. Just as every people group has owned slaves, every people group has correspondingly been enslaved. Prior to the 1700s there were more white slaves globally than there were black slaves.

However, this statement from Columbus’ ship mate, and the myths of the anti-Columbus critics, directly contradicts everything Columbus wrote about his motivations.

However, this statement from Columbus’ ship mate, and the myths of the anti-Columbus critics, directly contradicts everything Columbus wrote about his motivations.

Furthermore, these personal attacks now extend to anyone who might think the historical record tells a different story—certainly no one must examine the evidence or facts and draw a conclusion other than the one they reached. Defenders of Columbus are deemed, “just as idiotic and disgusting as he was,” because who but a bigot would suggest Columbus was anything but a, “half-wit harbinger of genocidal calamity.”

Furthermore, these personal attacks now extend to anyone who might think the historical record tells a different story—certainly no one must examine the evidence or facts and draw a conclusion other than the one they reached. Defenders of Columbus are deemed, “just as idiotic and disgusting as he was,” because who but a bigot would suggest Columbus was anything but a, “half-wit harbinger of genocidal calamity.” Even if you disagree with what Columbus was attempting to do, you cannot deny the fact that he was an outstandingly intelligent navigator—the best of his age. On top of that, his technical, scientific, and astrological knowledge rivaled, if not exceeded, that of many formally training “intellectuals” of his day.

Even if you disagree with what Columbus was attempting to do, you cannot deny the fact that he was an outstandingly intelligent navigator—the best of his age. On top of that, his technical, scientific, and astrological knowledge rivaled, if not exceeded, that of many formally training “intellectuals” of his day. The arrival of Christopher Columbus and his three diminutive ships laden with tremendous potential was an anthropologist’s dream. In 1492 Columbus encountered and documented for the first time the Taino people within the larger Arawak language group. Without Columbus and his efforts we would have no records of these cultures at all. While this tribe is largely considered to be the most civil out of all the native tribal groups encountered by the early Spanish explorers it does not hide the fact that they too participated in conquest, colonization, and slavery.

The arrival of Christopher Columbus and his three diminutive ships laden with tremendous potential was an anthropologist’s dream. In 1492 Columbus encountered and documented for the first time the Taino people within the larger Arawak language group. Without Columbus and his efforts we would have no records of these cultures at all. While this tribe is largely considered to be the most civil out of all the native tribal groups encountered by the early Spanish explorers it does not hide the fact that they too participated in conquest, colonization, and slavery. One example from the history of Ferdinand Columbus offers a pointed perspective into this newly discovered culture. He documents the tragedy of the first large confrontation between a hostile force and the coalition forces led by Columbus consisting of the Spaniards and allied tribes marshaled by Guacanagari. In an earlier attack upon the Spanish outpost and the allied Indian village one of his wives was murdered and another one captured to be thereafter enslaved to the victorious chieftain. “And that was why he now appealed to the Admiral to restore his wife to him and help him get revenge for his injuries.”

One example from the history of Ferdinand Columbus offers a pointed perspective into this newly discovered culture. He documents the tragedy of the first large confrontation between a hostile force and the coalition forces led by Columbus consisting of the Spaniards and allied tribes marshaled by Guacanagari. In an earlier attack upon the Spanish outpost and the allied Indian village one of his wives was murdered and another one captured to be thereafter enslaved to the victorious chieftain. “And that was why he now appealed to the Admiral to restore his wife to him and help him get revenge for his injuries.” The complete and deliberate depopulation of entire islands and communities by a dominate and oppressive culture very well can be defined as genocide through cannibalism—certainly much more than anything which Christopher Columbus ever did.

The complete and deliberate depopulation of entire islands and communities by a dominate and oppressive culture very well can be defined as genocide through cannibalism—certainly much more than anything which Christopher Columbus ever did. Other witnesses corroborate what Cuneo saw, explaining how the Caribs:

Other witnesses corroborate what Cuneo saw, explaining how the Caribs: The Huastec civilization serve as another example of the general trend within the central Mexican cultures which engaged in widespread subordination of weaker tribes and the sacrifice of those conquered peoples. The excavated pottery from the area depict the common heart extraction style of sacrifice similar to the example shown on the early codices from other regions such as Codex Magliabechiano.

The Huastec civilization serve as another example of the general trend within the central Mexican cultures which engaged in widespread subordination of weaker tribes and the sacrifice of those conquered peoples. The excavated pottery from the area depict the common heart extraction style of sacrifice similar to the example shown on the early codices from other regions such as Codex Magliabechiano. Overall, the world which Christopher Columbus discovered is radically different from the human egalitarian society presented by the modern revisionist writings on the subject. Academics like Zinn and Lynd begin from the assumption that America was founded upon crimes committed against the Indians by the European explorers and colonists and ignore any data which suggests the opposite. In their intellectual expedition to do “history from the bottom up” they are never able to tell the history of those truly at the bottom. They stop short of the women enslaved and abused by the Caribs and liberated by Columbus. In their desire to prove the American founding evil they ignore the wider context surrounding the voyages. The facts do not validate their philosophy. The evidence simply does not fit with the “highly egalitarian ideologies and practices,” promoted by Zinn.

Overall, the world which Christopher Columbus discovered is radically different from the human egalitarian society presented by the modern revisionist writings on the subject. Academics like Zinn and Lynd begin from the assumption that America was founded upon crimes committed against the Indians by the European explorers and colonists and ignore any data which suggests the opposite. In their intellectual expedition to do “history from the bottom up” they are never able to tell the history of those truly at the bottom. They stop short of the women enslaved and abused by the Caribs and liberated by Columbus. In their desire to prove the American founding evil they ignore the wider context surrounding the voyages. The facts do not validate their philosophy. The evidence simply does not fit with the “highly egalitarian ideologies and practices,” promoted by Zinn. This tradition of conquest, colonization and enslavement continued in the Islamic world as the power of Rome splintered and crumbled in both the East and West. The Barbary Coast of North Africa under Muslim rule became a Mecca for the slave trade as African tribes sold captured combatants to the Islamic traders, who then exported them around the Mediterranean. In fact, the African slave trade conducted by Islamic traders first exposed Europe to the idea through the Muslim invasions in the Iberian peninsula.

This tradition of conquest, colonization and enslavement continued in the Islamic world as the power of Rome splintered and crumbled in both the East and West. The Barbary Coast of North Africa under Muslim rule became a Mecca for the slave trade as African tribes sold captured combatants to the Islamic traders, who then exported them around the Mediterranean. In fact, the African slave trade conducted by Islamic traders first exposed Europe to the idea through the Muslim invasions in the Iberian peninsula.

aspects:

aspects: This complaint calls back to the instructions of Ferdinand and Isabella, and the Inter Caetera from 1493 only seven years prior. Throughout the letter Columbus decries the impious actions of the Spaniards done in contradiction the governing policies established by both crown and church.

This complaint calls back to the instructions of Ferdinand and Isabella, and the Inter Caetera from 1493 only seven years prior. Throughout the letter Columbus decries the impious actions of the Spaniards done in contradiction the governing policies established by both crown and church. Columbus wrote these words off the coast of Spain, bound in chains. An official officer sent by the King and Queen to investigate allegations of misconduct shipped Columbus and his brothers back to Spain in 1500 after usurping power and allying himself with the armed rebels. Columbus penned the above letter as a vindication of his conduct to Ferdinand and Isabela, and in a sense, his claim proved to be prophetic. As soon as the Sovereigns discovered the imprisonment of Columbus, they ordered him released and to appear before them in order to address the accusations. After hearing Columbus’s defense, they cleared him of all charges. The allegations were not credible and proved to be false upon investigation. Columbus was restored.

Columbus wrote these words off the coast of Spain, bound in chains. An official officer sent by the King and Queen to investigate allegations of misconduct shipped Columbus and his brothers back to Spain in 1500 after usurping power and allying himself with the armed rebels. Columbus penned the above letter as a vindication of his conduct to Ferdinand and Isabela, and in a sense, his claim proved to be prophetic. As soon as the Sovereigns discovered the imprisonment of Columbus, they ordered him released and to appear before them in order to address the accusations. After hearing Columbus’s defense, they cleared him of all charges. The allegations were not credible and proved to be false upon investigation. Columbus was restored.